Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 15-Abr-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469826836

ARTICLE

BABY CRYING AND TEACHING AT DAYCARE

1Professor at the Municipality of Belo Horizonte and Ph.D. student at the Graduate Program in Education: Knowledge and Social Inclusion at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. <fernanda.coutinho12@gmail.com>

2Associate Professor at the Faculty of Education and at the Graduate Program in Education: Knowledge and Social Inclusion at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. <izarodriguesluz@gmail.com>

The present paper aims at analyzing the (re)actions of both teachers and assistants in Preschool Education when faced with babies' cries in interactions held at a Municipal School of Early Childhood Education (EMEI) in Belo Horizonte city in the state of Minas Gerais, relying on the literature and the reference documents for Preschool Education in both national and local levels. This is a Master's study of qualitative nature that had to participate observation as its main method in a group comprised of 12 babies, 4 teachers, and 1 assistant. The observations, carried out over the second half of 2017, were recorded in a field diary as well as through video recordings. Based on the analyses conducted, the (re)actions of both the teachers and the assistant were grouped into two categories: moments of improved connection with the principles and goals of EI, and moments of tension and contradiction with such principles and aims. Given the complexity of care and education work in daycare, we recommend either conducting further research on babies' expressions and the attitudes of teachers and assistants and reaffirming the importance of such professionals having systematic moments for reflection upon their teaching practice.

Keywords: teaching babies; babies; Preschooling; daycare; cry

Este artigo tem como objetivo analisar as re(ações) das professoras e da auxiliar de apoio à Educação Infantil, diante do choro dos bebês, nas interações estabelecidas em uma Escola Municipal de Educação Infantil (EMEI) de Belo Horizonte (MG), tendo como referência a literatura e os documentos norteadores da Educação Infantil no âmbito nacional e municipal. Trata-se de uma pesquisa de mestrado de abordagem qualitativa que teve como principal método a observação participante em uma turma composta por 12 bebês, 4 professoras e 1 auxiliar. As observações, realizadas durante o 2° semestre do ano de 2017, foram registradas em diário de campo e por meio de videogravações. Com base nas análises, as re(ações) das professoras e da auxiliar foram agrupadas em duas categorias: momentos de maior sintonia com os princípios e as finalidades da EI; e momentos de tensões e de contradições com tais princípios e finalidades. Considerando-se a complexidade do trabalho de cuidado e educação na creche, tanto se indica a realização de novas pesquisas sobre as expressões dos bebês e sobre as posturas e ações das professoras e auxiliares, como se reitera a importância de que essas profissionais tenham momentos de reflexão sistemáticos sobre suas práticas educativas.

Palavras-chave: docência com bebês; bebês; Educação Infantil; creche; choro

este artículo tiene como objetivo analizar las re(acciones) de los maestros y el Asistente de Apoyo a la Educación Infantil, frente al llanto de los bebés, en las interacciones establecidas en una Escuela Municipal de Educación Infantil (EMEI) de Belo Horizonte - Minas Gerais, con referencia a la literatura y los documentos orientadores de la Educación Infantil a nivel nacional y municipal. Esta es una investigación de maestría de abordaje cualitativo que tuvo como método principal la observación participante en una clase compuesta por 12 bebés, 4 profesores y 1 Asistente. Las observaciones, realizadas durante el 2do semestre de 2017, fueron registradas en Diario de Campo y a través de grabaciones de video. Sobre la base de los análisis, las re(acciones) de los docentes y el asistente se agruparon en dos categorías: momentos de mayor armonía con los principios y propósitos de la IE; y momentos de tensiones y contradicciones con dichos principios y propósitos. Considerando la complejidad del trabajo de cuidado y educación en la guardería, señalamos tanto la realización de nuevas investigaciones sobre las expresiones de los bebés como sobre las posturas y acciones de los maestros y asistentes, como reiteramos la importancia de que estos profesionales tengan momentos de reflexión sistemática sobre sus prácticas educativas.

Palabras clave: enseñanza con bebés; bebés; Educación infantil; guardería; llanto

INTRODUCTION

Teaching in Early Childhood Education - ECE -, especially with babies, has been the topic of investigations and debates in the area. Even with the achievements and advances regarding the quality of assistance to ECE in the country, guaranteed in the legislation and documents in the area, there are still gaps and one of them is the formation of professionals (CAMPOS; FULLGRAF; WIGGERS, 2006; HADDAD, 2010; SCHMITT, 2014; CESTARO, 2019).

When reflecting on teaching at ECE, Cerisara (1999) shows that the conceptions of the identity of teachers are related to the history of the emergence of daycare centers and preschools in the country, in which care in daycare and education in preschool prevail. We understand that the conceptions that these professionals have about babies are related to the constitution of teaching with babies, being historically constructed, directly implying the work they develop and the way they relate to them.

Considering all these factors and the process of singular references of teaching work at this stage of Basic Education, still, under construction, researchers in the area highlighted the need for reflections and public policies for initial and continuing education that address the theme of the meanings of work of caring and educating, in an inseparable way, in the context of ECE, especially working with babies, considering their specificities (CAMPOS, 1994; CERISARA, 1999; AMORIM; VITÓRIA; ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, 2000; KRAMER, 2008; BARBOSA, 2010; DUMONT-PENA, 2015; SILVA, 2016, 2004). Among these specificities, their ways of communication stand out, which consist of bodily and emotional expressions such as crying, which has been the focus of recent studies on these ways of expression in the context of ECE institutions (ELTINK, 2000; MELCHIORI, 2004; PANTALENA, 2010; AMORIM; COSTA; RODRIGUES; MOURA; FERREIRA, 2012; SANTOS, 2012; FERREIRA, 2020). However, there are still few works that focus on crying as a way of communication for babies in this context, as evidenced in a bibliographic survey that was updated in August 2020. The Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES - Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior), the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) website, the Electronic Journals in Psychology (PEPSIC), the UFMG University Library, and Google academic were consulted. The search was between 2000 and 2020, using, in a combined way, the following descriptors: “crying, babies and daycare”, “teachers, baby and crying” and “crying and ECE”. We also searched for works on the website of the National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Education (ANPED- Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Educação), in the following workgroups: WG 7 - Education of children from 0 to 6 years old; WG 8 - Teacher Education; and WG 20 - Educational Psychology, between 2000 and 2019 (23rd to 39th Annual Meeting). In total, we found 26 studies that, in some way, deal with the theme of babies and their interactions with the other adult in ECE institutions, highlighting crying as a specific way of communication for this group. These works are research in the areas of Education and Psychology. The works found, even with different themes and objectives, converge to a central focus, which is the potentialities and capacities of babies and young children as active individuals, who can express themselves in various ways in the moments of interaction with others, and how important is the role of teachers in reacting and giving meaning to the babies' expressions, contributing to their integral development. However, few studies focus on the crying of babies in ECE institutions as their main focus of analysis. In the next section, we will highlight some of these researches that relate to the focus defined in this article.

Thus, we think is important to reflect on this emotional expression of babies in ECE, emphasizing the importance of the postures and actions of teachers4 and assistants5 in crying as an element that allows reflections on the professional and human formation necessary in the work of care and education. In this sense, we seek to analyze the re(actions) of the teachers and the ECE support assistant in the crying of babies in the interactions established with them in the EMEI (Escola Municipal de Educação Infantil), having as reference the literature of the area and the guiding documents of the ECE at the national and municipal level.

The work is structured in three sections: In the first, we will discuss the crying of babies and teaching in the daycare center; in the second, the profile of ECE teaching in Belo Horizonte and the methodological paths of the research will be briefly presented (MARQUES, 2019); and the third section will present, in a succinct way, the dynamics of organization of the routine and the babies' environment and the analyzes and reflections on the re(actions) of the teachers and the assistant in the crying, in their moments of interactions in the researched EMEI.

THE CRYING OF BABIES AND TEACHING IN THE DAYCARE

Teaching with babies is a job that requires physical disposition and an emotional disposition since there are many “emotions, senses and feelings involved in the bonds between babies and adults in a full-time day at daycares &91#;...&93#;” (GUIMARÃES, 2011, p. 194). Babies, in their condition of dependence on adults, demand greater availability from teachers and demand that work with them be planned, considering the singularities and how they express their desires. Through these expressions and interactions, in the countless possibilities that the other points out to them, babies build their languages and their senses for everything that surrounds them (RITCHER; BARBOSA, 2010). Among these specific languages, crying is considered an important way of communication of babies with the world, and through this emotional communication, they interact with each other and with the environment in which they are inserted. In this process of meaning and interaction with the other, they are constructed as an individual (WALLON, 1968, 1971; VIGOTSKI, 1996, 1998, 2007).

On human development, as Vygotsky (1996, 2007), Wallon (1968, 1971) conceives it as something non-linear, a dynamic process that takes place in a tangle of biological, social, and cultural factors, in which the construction of knowledge, of the self and the other, happens through the relationships and interactions with the environment in which the individuals are inserted. Based on this assumption, the Wallonian psychogenetic theory proposes a study of the complete person in a dialectical perspective, thinking about the child's development in a contextualized way and stages, in which “&91#;...&93#; each phase is a system of relationships between the child's capacities and the medium that makes them reciprocally specify” (WALLON, 2007, p. 29). These phases are not replaced one by the other, there is complementation between them. This development is not understood in a single aspect, but rather in an integrated way, encompassing all the functional fields in which the child's activity is distributed: the affective, the cognitive, and the motor (GALVÃO, 1995).

Affectivity is the central theme of Henri Wallon's psychogenetic theory. It is one of the functional domains that play an essential role in the constitution of the child's higher psychic processes; the first manifestations of babies are characterized by emotion. “Emotion is the manifestation of a subjective state with strongly organic components, more precisely tonic; it is the proper expression of affection” (ALMEIDA, 2009, p. 53). In Wallon's words about the newborn:

Their affective manifestations were initially limited to the wail of hunger or colic and the relaxation of digestion or sleep. At first, their differentiation is very slow. But, at 6 months, the system of the children to translate their emotions is varied enough to make them a vast surface of osmosis with the human environment. This is a fundamental stage of their psyche. Their gestures are linked to certain effects through the other; to the gestures of others, the predictions. But this reciprocity is initially a complete amalgamation, it is total participation, in which they will later have to delimit their person, deeply fertilized by this first absorption in the other (WALLON, 1968, p. 194).

In this sense, these emotional expressions of babies become meaning through the interactions they establish, firstly, with the human environment and, later, with the environment. In this rich moment of learning, it is established “&91#;...&93#; an intense affective communication, a dialogue based on body and expressive components” (GALVÃO, 1995, p. 61), which are constitutive parts of their social interactions. “This beginning of the human being by the affective or emotional stage that, incidentally, corresponds so well to the total and prolonged clumsiness of his childhood, guides his first intuitions towards others and puts sociability in the foreground in him” (WALLON, 2008, p. 120).

About crying early in life, Wallon (2007) states:

The crying of the newborn that comes into the world, crying of despair, according to Lucrécio, before the life that opens up to him, crying of anguish, according to Freud, at the moment in which it separates from the maternal organism, for the physiologist it means nothing more than a spasm of the glottis, which accompanies the first respiratory reflexes. Its psychological motivation linked to presentiment or regret has something mythical. But its reduction to a simple muscular fact is no more than an abstraction. It belongs to a whole vital complex. Crying is linked to spasms, but a set of conditions and simultaneous impressions that are expressed in spasms as well as crying. At this elementary stage, one obviously cannot think of distinguishing the sign from the cause (WALLON, 2007, p. 118).

Crying, initially biological, is modified by cultural and social activities, by the action of the other, “&91#;...&93#; crying in the proper sense is a characteristic of homo sapiens, it is one of the hallmarks of the human species” (PINO, 2005, p. 204). This crying, over time, becomes a means of emotional expression, a form of representation of a certain demand and the child's reactions to the social environment. According to Vasconcelos et al. (2014), for Vygotsky, the various ways babies express, even before the pronunciation of the first words, such as crying, gestures, and babbling, are considered ways of speaking, even if they are not yet related to thought. In this sense, the affective dimension constitutes one of the propelling elements of this development and this learning of babies in the context of ECE.

In daycare, crying that is not welcomed is not meant, it is up to the baby to elaborate the situation for himself. The teacher does not act as a container or a recipient. If crying were understood as the child's communication &91#;...&93#; it would favor the teacher-baby relationship &91#;...&93#;. Hearing the cry is giving the baby a voice (PANTALENA, 2010, p. 95).

We need to recognize and understand how emotional expressions occur in this context of ECE since the figure of the teachers is fundamental for welcoming and creating situations of listening and interaction. Regarding the ways of caring and responding to these demands of babies, the research by Eltink (2000) on the process of inserting children under two years old into daycare sought to discuss some indications that educators used to assess whether a child was doing well or not, crying was highlighted as one of the signs that indicated the discomfort. Thus, when working with babies in ECE institutions, teachers need to know how to recognize their languages, welcoming their emotions. Santos (2012), in his study on children's crying in this context, states that:

Dealing with it evokes the conceptions of childhood, education, and learning that are revealed in the actions of professionals, in daily life in daycare centers. We assume, then, that crying is part of the daily movement of the daycare center and must be problematized beyond the moment of insertion of young children in the institutions that receive them (SANTOS, 2012, p. 101).

In this sense, it is important to pay attention to the quality of children's relationships with adults in ECE institutions, especially with teachers, since through these relationships and interactions, children signify and re-signify the world. Vygotsky (2007), with his theoretical contribution, contributed significantly to thinking about the education and care of young children, especially babies, indicating how the mediating elements, especially adults, play a fundamental role in this process.

Barbosa (2010) states that “&91#;...&93#;. Educating babies does not only mean the constitution and application of an objective pedagogical project but putting physically and emotionally, at the disposal of children, which requires commitment and responsibilities from adults” (BARBOSA, 2010, p. 5). Teaching with babies depends on this commitment and engagement.

Gonçalves and Rocha (2017) identify that being a baby teacher is a job marked by subtlety, sensitivity, “&91#;...&93#; by relationships, human interactions and the sharing of experiences” (p. 403). It is a work that has its specificities and singularities regarding the care and education of babies. Among these aspects that constitute teaching with babies, the authors also highlight the centrality of care actions, which are characterized in various ways, as the individuals who are involved depend on them; their conceptions and subjectivities also depend on who cares and who is cared for and are still deeply involved by the way of thinking about care as a human dimension, in a broader sphere of society.

It is important to highlight that care has been the theme of debates and analyses in different fields of knowledge, such as Social Sciences, Health, Philosophy, Psychology, and Education. In all these areas of knowledge, the assumption is that care is considered constitutive of human relationships, not being a merely technical work, but a concept resulting from social construction, which involves the various forms of organization of societies and social and cultural practices that characterize different realities, as well as social, cultural and gender inequality (GUIMARÃES; HIRATA; SUGITA, 2012; MOLINIER; PAPERMAN, 2015). Therefore, this work of caring cannot be governed by the logic of intervention and domination, but by the understanding that caring is, above all, a way of being and not simply doing, it is something that encompasses the human being in its entirety, it is the “&91#;...&93#; essence of the human” (TEIXEIRA SILVA, 2017, p .472).

In this work with babies, care practices are at the heart of relationships. Regarding the work of these teachers in ECE institutions, Maranhão (2011) questions whether training to care for babies and children would be possible, or if not “&91#;...&93#; would care to be a sphere of individual experience that concerns to the personality of the educator” (p. 83). In this sense, we cannot fail to consider that these conceptions and experiences cross and permeate, at all times, the way of teaching babies.

Regarding the care and education work with babies in ECE, the National Curricular Guidelines for Early Childhood Education - DCNEI Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais da Educação Infantil - present a conception and purpose of ECE referenced in the understanding of babies and children as individuals and the centrality of interactions and games in their learning processes and integral development. In this way, they advocate that these are the main axes of work organization and pedagogical practices to be carried out with these people in ECE institutions. This document reiterates the importance of thinking about the organization of times, spaces, and materials in daycare centers and preschools, in a way that the inseparability of care and education work is ensured, considering the “expressive-motor dimensions, affective, cognitive, linguistic, ethical, aesthetic and sociocultural aspects of children” (BRASIL, 2010, p. 19). Based on these principles, we expect that teachers and other professionals who work in this stage of Basic Education have a look at children, especially babies, considering them as active and powerful individuals, capable of affecting, creating, and provoking the adults in the sense of the search for knowledge and the meaning of the world.

THE PROFILE OF ECE TEACHING IN BELO HORIZONTE AND THE RESEARCH METHODOLOGICAL PATHWAYS

In the ECE teaching, especially with babies, in the case of Belo Horizonte (MG), the training requirement for teaching at this stage of Basic Education, at the time of the research, was the minimum training in High School in the Normal Modality, upon approval in a public tender, with a daily shift of 4 and a half hours, totaling 22 hours and 30 minutes per week. Recently, in 2018, the training requirement for the exercise of the position was changed, and now, only professionals with a minimum degree of higher education will be able to assume the position of ECE teacher (BELO HORIZONTE, 2018).

The hiring of the assistants who also work in the EMEIs in Belo Horizonte at the time of the research was done by the school funds, through the CLT system, with a working day of eight hours a day. The criteria for participating in the selection and hiring process were having completed high school without a teaching qualification; being at least 21 years old; have registered with the National Employment System (SINE- Sistema Nacional de Emprego) (BELO HORIZONTE, 2015). Recently, in addition to these requirements, some changes have occurred, highlighting the need to present at least six months of experience in activities in the school environment, upon some proof.

We want to highlight here, even if briefly, some of the attributions of these assistants in working with babies and young children. Under the guidance of the teachers, they assist in educational activities, such as feeding, bathing, changing diapers, among others. They must take care of the children, always seeking to relate and interact respectfully and attentively with them, both in the internal and external spaces of the institution (BELO HORIZONTE, 2015).

As for the work of caring for and educating babies and children, we noted that the attributions of these assistants are also part of the attributions of the ECE teachers in the municipality. In this sense, the creation of the position of assistant, in the case of Belo Horizonte, is possibly one of the factors that make it difficult to understand what teaching in the nursery is. Also, the division from the creation of this other position weakens the construction of practices that articulate care and education, since the assistants are more responsible for the actions recognized as care, and the teachers, for the practices recognized as educational (BITENCOURT; SILVA, 2017).

Regarding care and education practices, the Curriculum Propositions for ECE in the municipality reaffirm the understanding of interactions and games as structuring axes of pedagogical proposals in ECE institutions (BELO HORIZONTE, 2015). The Propositions also present the understanding of babies and young children as individuals of rights and competent who “&91#;...&93#;interrogate the world, its elements, its relationships, re-elaborate them and assign meaning to this whole process” (BELO HORIZONTE, 2014, p. 61).

In this learning and development process, the DCNEI reiterate the importance of recognizing two main aspects: the way babies and children relate to the world and the way they manifest and communicate with others; and the recognition that the practices they experience and the way others interact with them - and how they react to their specificities - create a context that acts directly on the subjectivity of each of these individuals, both in babies and children as in the professionals (BRASIL, 2010). We should emphasize that, during the research, the National Common Curriculum Base - Base Nacional Comum Curricular - BNCC - was approved. It is a document that has a mandatory character and has been a source of discussions and tensions in the area of ECE.6

We present here part of the results of research (MARQUES, 2019) with a qualitative approach (MINAYO, 2012), focusing on reflective analyzes of the re(actions) that these teachers and the assistant had in the crying of babies at EMEI, taking as a reference, studies of ECE (CAMPOS, 1994; CERISARA, 1999; SILVA, 2004; KRAMER, 2008; BARBOSA, 2010; FALK, 2011; FOCHI, 2019, 2013) and normative documents of ECE at the national and municipal levels (BRASIL, 2010, 1996; BELO HORIZONTE, 2015, 2014). As the main method, participant observation was used, following a class composed of 12 babies, 4 teachers, and 1 ECE support assistant in an EMEI in Belo Horizonte (MG).

The observations were made during the second half of 2017 and were recorded in a field diary. Video recordings of the group's interactions and semi-structured interviews with the teachers and the assistant were also made. The results presented here come from the analysis of video recordings and field diary records. Thematic content analysis (BARDIN, 1979) was the reference for data classification and organization.

To carry out the research, we followed all procedures established by the Graduate Program in Education and the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). All procedures and ethical care were also observed in the authorization for the beginning of the research and entry into the field and the participation of the subjects. For this, we had meetings with the teachers, with the assistant, and with the legal guardians of the babies to present the research and the Informed Consent Form - ICF. Considering that ethics goes beyond these technical and bureaucratic procedures, we sought to adopt a welcoming posture for the participants involved in the research throughout the fieldwork. Recognizing the privilege of being in the field, especially with babies, we tried to observe them considering their specificities and interacting with them in an emic perspective of investigation, always based on unconditional respect.

From the footage data, we found 131 scenes of crying expressions of babies in the most diverse moments of interaction with each other, with the teachers, and with the assistant. The transcription of all these scenes was performed in full, and, after this detailed work, we found a general map of the information. From this general map, we created tables to group scenes in which the re(actions) were similar, making the mapping of each one of them. Four different forms of re(actions) were observed: they re(acted) when the babies were crying, approaching, and talking to them; they checked their physical and biological needs; they kept or offered some object or toy; and finally, they distanced themselves or did not approach the babies when they were crying (MARQUES, 2019).

QUESTIONS AND REFLECTIONS ABOUT THE RE(ACTIONS) OF TEACHERS AND ASSISTANT WITH THE CRYING OF THE BABIES

In the analysis presented below, we considered both the concrete conditions of the institution in which the observed individuals were inserted and the conceptions of the teachers and the assistant about the babies with whom they had a relationship and about the work developed with them at EMEI (DUBET, 1994; VIGOTSKI, 2007). In this sense, we considered it important to briefly explain some elements about the participants and the dynamics of the routine and organization of the environment for the group of babies, since they influenced, to a large extent, the interactions they established in the EMEI, and their crying expressions. The routine is understood as something more comprehensive, which includes, in addition to repetitive activities, the possibilities of its flexibility, the subjectivities of the individuals inserted in that space, and the relationships established in the environment, as indicated by Horn (2004).

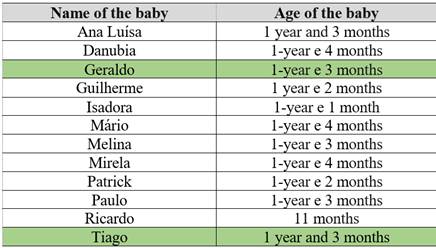

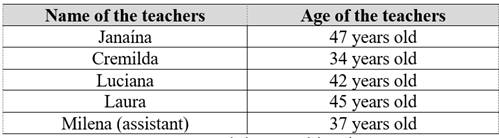

The class had 12 babies, monitored daily by five teachers and an ECE support assistant during full-time. The boxes boxe below show the names7 and ages of all the research participants. In the first table, referring to the identification of babies, we highlighted the twin babies who were part of the class.

Source: Research data. Our elaboration.

Box 1 - Presentation of babies8 and their ages at the beginning of the research.

Source: Research data. Our elaboration.

Box 2 - Presentation of the teachers and the assistant and their ages at the beginning of the research

Every day, two teachers were in the room while the other two were involved with the planning of pedagogical activities in the external space of the room. The assistant's role was always to be with the teachers, except when there was a demand from the pedagogical coordination.

Regarding the organization of the pedagogical work with the babies, who remained at the EMEI full-time from 7 am to 5:30 pm, we found that there was a fixed routine, but with some flexibility, considering their demands. The main actions of this routine, in the morning shift, were named by the teachers as follows: “Welcome”, “Baby bottle”, “Light meal”, “Bath”, “Lunch”, “Diaper change” and “Sleep”. Considering that these observations were specifically in the afternoon, this study will focus on this part of the day. In the afternoon shift, at 12:45, the babies were woken up to take the bottle; then the other stages were followed - “Diaper change”, “Snack”, “Dinner”, “Diaper and clothes change” and “Sleep” - until it was time to leave. Along with this daily routine, there were actions, called “pedagogical activities”, related to two projects developed in the nursery: “Ateliers” and “Sensations”. The activities related to the projects were carried out on alternate days of the week and involved the babies going out to other spaces at EMEI, such as the library, the park, the lobby, the playground, and the solarium.

For different reasons, the activities planned to be carried out in the external spaces did not take place. In these situations, the teachers tried to reorganize the routine with other activities carried out inside the nursery room. Consequently, as observed during the research, the babies rarely circulated in other environments of the EMEI, especially the external ones. When they did, the teachers rarely stayed in these spaces for a shorter period than what was established in the babies' daily routine. Thus, there was a routine organization contrary to the indications of the literature, because, according to Barbosa (2010), babies have the right to attend other spaces in the school and the activities room, especially the external spaces, since “&91#;...&93#; it is necessary for young children to have daily contact with sunlight, fresh air and to be able to observe and interact with nature” (p. 8).

In the nursery room, the teachers were careful and attentive to the babies and, all the time, they tried to carry out some activity to involve the group as a whole. However, they rarely failed to do so, since, for that, all babies would have to have a simultaneous interest in the same activities and objects, something complex and difficult to happen. We also found that the objects were given only when there was some work proposal directed by the teachers and that the dispute over them was usually a trigger for crying.

To understand the re(actions) of the teachers and the assistant in a detailed way and the possible factors that may have influenced them in some way, we sought to make this synthesis of the observed context, trying to capture the possibilities and limitations of the times, spaces and materials and their implications for the interactions between the teachers, the assistant and the babies at EMEI.

The analysis of the re(actions) of the teachers and the support assistant in the babies' crying were grouped into two categories: re(actions) that reveal moments of harmony between the theoretical reflections and the interactions in the daycare; and re(actions) that reveal moments of tension and contradictions in the interactions at the daycare center.

In the first category, we identified reflections on the postures and re(actions) of the teachers and the assistant with the crying of babies, considered attentive and committed to promoting the integral development of these individuals, as recommended by national and international legal documents (BRASIL, 2010, 1996; BELO HORIZONTE, 2015, 2014). In the second category, we listed reflections and criticisms about the moments in which the teachers and the assistant distanced from these principles and the purpose of ECE, disregarding, to some extent, the needs of babies. The line of work of this study involves an ethical posture that opposes the previous and simplistic judgment of the re(actions) of the teachers and the assistant. In this sense, the first objective is to provide some reflections in which the theories, the meanings produced by the researchers, and those produced by the babies, the teachers, and the assistant to support ECE of the EMEI, are intertwined. The idea is to allow these meanings to appear, emerging also differences (GEERTZ, 1989).

The re(actions) of the teachers and the ECE support assistant with the babies' crying: moments of harmony between theoretical reflections and interactions in the daycare center

Regarding the re(actions) of the teachers and the assistant, most of the time, they re(acted) to crying, approaching the babies and talking with them, showing that they were, in general, attentive to their crying expressions and interacting with them, as we can see in the episode described below:

Teachers Cremilda and Laura are in the solarium with the babies. There are carts and plastic objects and hula hoops arranged on the floor. Babies play and handle objects. &91#;...&93#;. Isadora is also there next to the door and Ana Luísa approaches her with a round object and hits her face with it. Isadora puts her hands on her nose and starts crying. Cremilda approaches and bends down a little to talk to Ana Luísa while taking the object from her hand and then returning it to her. Laura approaches Isadora and takes the baby in her arms. She looks into her face, checking for any bruises. Isadora continues to cry on Laura's lap and Laura walks away with her and says: “Let's go get Melina?” &91#;...&93#;. Laura enters the room with Isadora on her lap and the baby no longer cries (transcription of video recording performed on 11/09/2017).

We noticed that the babies were in a moment of interaction with each other and with the toys and objects in the solarium. According to the observations, crying hardly emerged in these situations: in most cases, it was triggered by the dispute over toys or even the desire for touch and the babies to get close to each other, as can be seen in the episode described above. With the approach and dialogue of teacher Cremilda, Isadora had her crying diminished. Isadora's crying also affected teacher Laura, who also approached and took the baby in her arms. Laura talked to Isadora while checking to see if there were any bruises on her face.

The episode evidences the delicacy by the teachers in working with the babies, when they approach them and try to understand the reasons for crying, showing concern and attention towards them.

In another episode, actions and postures consistent with the recognition of babies as active and capable individuals were witnessed, in the interactions they establish with the world. Welcoming and understanding the babies' crying was characterized as a form of communication by the assistant. We observed that Milena answered and welcomed Ana Luísa's crying, establishing interaction with her, to understand her expressions and respond “carefully”.

Milena is there in the solarium, bent over with Melina standing between her legs. Ana Luísa approaches them and tries to stay very close to Milena. She starts to cry and Milena gets up. Ana Luísa extends her arms to Milena, walks a little, and bends down crying. Laura looks and says: “Oh, there was no crying until now, Milena. I think Ana Luísa's problem is you. Oh, sweetheart!” Milena smiles and walks to the railing. Laura: “It's morning. It's Milena. There hasn't been a cry so far.” Milena smiles and runs her hand through Ana Luísa's hair, who is already there with her arms outstretched to Milena. She takes Ana Luísa on her lap and after a few seconds, she bends down and puts her on the floor. Ana Luísa stops crying and walks out into the solarium (transcription of a video recording made on 12/11/2017).

The assistant Milena, somehow, always embraces the babies' cries, first offering them her lap; at that particular moment, she immediately responded to the baby's cry in exactly this way. In less than two minutes, the assistant put the baby on the floor again, and she did not cry anymore. Through this episode, we found that the attitudes of the assistant were in line with what Barbosa (2010) considers about the role of adults in the education and care of babies:

&91#;...&93#; it is necessary to be with them, to observe, to “listen to their voices”, to accompany their bodies. The teacher embraces, supports, and challenges children so that they participate in a shared life path. Continuously, the teacher needs to observe and carry out interventions &91#;...&93#; (BARBOSA, 2010, p. 6).

Adults who take care of babies in the nursery are responsible for “&91#;...&93#; interacting with &91#;...&93#; them, recognizing themselves as sources of information, affection, and care. It is to interpret the personal meaning of their discoveries and achievements in an intense affective communication based on bodily and expressive components” (PEDROSA, 2012, p. 35), since all re(actions) and interactions of the other towards the babies, such as sounds, gestures, looks and the responses given to their needs, both biological and psychological, contribute to a great extent and decisively to the very constitution of these subjects as a person (BELO HORIZONTE, 2014).

In the care relationships, in intimate proximity, babies and teachers learn to care for themselves and the other, because, “&91#;...&93#; to take them on the lap, to change a diaper &91#;...&93#;”, the teachers will be helping to establish communication links with the other, giving new meaning to their emotional manifestations (SCHMITT, 2008, p. 117).

The teachers were also sensitive and understood the babies' crying when they re(acted) in the moments of verification of their physical and biological needs.

Babies Geraldo, Ricardo, and Paulo are sitting on high chairs in the cafeteria for dinner. Janaína is there with them. Geraldo starts swinging his legs and when he sees the intern with Paulo's plate of food, he starts screaming and then kicking and crying. He stretches his body as if he wants to get out of the seat. Janaína, who is taking Geraldo and Ricardo´s dishes, talks to him: “Calm down, Geraldo, it goes now, it's hot. Calm down, Geraldo.” He doesn't stop crying, but his crying soon diminishes. Janaína repeats that the food is hot and Geraldo cries. He moves his body in the seat as he cries. Janaína comes over with the dishes and starts serving him. Janaína also serves Ricardo. Geraldo stops crying as soon as she offers him the first spoonful of food. Geraldo is calm and doesn't cry anymore (transcription of video recording carried out on 09/18/2017).

The episode described gives evidence that baby Geraldo cried because he was hungry, since, at the moment when teacher Janaína started to serve him, the crying soon stopped. We noticed that Geraldo's cry emerged the moment he realized that another baby was already being served. Teacher Janaína was affected by Geraldo's crying and soon reacted, approaching him and talking to him. With the teacher's approach and dialogue, Geraldo stopped crying.

At other times, it is also noticed that the teachers and the assistant were attentive to the babies' interactional episodes, re(acting) in front of their crying, keeping or offering them some toy or object.

At that moment, Ana Luísa is facing Milena and, looking at her, smiles and taps her hands on the floor. Milena does the same thing and also smiles as if they were engaged in a joke. Danubia enters among them, as if she were crawling, and throws her hands to the ground, hitting Ana Luísa's hand. Ana Luísa looks to the side and then to Milena and starts to cry intensely. Milena says: “Come here. Oh, baby!” Milena picks up the baby and sits her on her lap. Cremilda has a tense expression on her face and talks to Janaína to get Ana Luísa's pacifier. Janaína comes and puts her pacifier in her mouth. She is on Milena's lap and Patrick is also there. Danubia notices and approaches, making an expression of who is also crying. Milena looks at her and asks: “Why is Ana Luísa crying?” Danubia is watching. Ana Luisa stops crying. &91#;...&93#; (transcription of video recording carried out on 09/18/2017).

In the episode above, we considered that the teachers and the assistant re(acted) in a consistent way with the proposal of studies in the area and the guiding documents of ECE (BRASIL, 2010; BELO HORIZONTE, 2015, 2014). They were attentive to the baby's cry, re(acting) to welcome her and offer her the pacifier, which, in this case, was an object of attachment and affection for the baby. We also saw that, through dialogue, gestures, and looks, the teachers, as well as the assistant, tried to make the babies understand their feelings and behaviors. This showed that they do not understand crying only as something negative, but rather as a way of expressing something beyond suffering and frustration.

Next, there is an episode in which the teachers did not approach the crying baby, not out of disrespect for their specificities, but as a way of caring in omnipresence (SCHMITT, 2008; GUIMARÃES, 2011).

&91#;...&93#;. Ricardo is crouched a little behind Cremilda and I see him start to cry. Cremilda looks at him and says: “Who's going for a walk? Shall we put &91#;the objects&93#; away for us to walk around?” &91#;...&93#;. Ricardo is sitting, crying. Ricardo cries and looks at Cremilda who is walking around the room gathering the objects to put away. His face is wet with tears. &91#;...&93#;. After a few seconds, he stops crying and is watching everything. &91#;...&93#; (transcription of video recording performed on 11/06/2017).

We considered that these attitudes of the teachers and the assistant shown above, such as approaching and dialoguing with the babies, embracing and offering a lap, or some toy or object, illustrate well what Schmitt (2008) says about the work of teachers in the nursery. The author argues that this work requires greater emotional disposition and physical closeness from the babies, and the teachers' understanding of their languages. Thus, in the moments of human and professional formation of those who work in ECE, it is important to provide reflections and insights into this positive and embracing attitude of teachers and assistants as a fundamental aspect of care and education actions.

The re(actions) of the teachers and the ECE support assistant in the babies' crying: moments of tension and contradictions in the interactions at the daycare center

In this research, in general, we could observe that the teachers and the assistant showed attention to the interactional episodes and the different expressions of the babies. However, moments of tension and contradictions were present in several situations during the care and education work in the nursery. A first criticism is highlighted regarding the way they re(acted) in the babies crying, keeping or offering them some toy or object, and the intrinsic relationship that exists between crying and how times, spaces, and materials were organized for the baby group.

&91#;...&93#;. At that same moment, Isadora cries, she is disputing an object with Mirela. This one pulls the object and Isadora too. Mirela slams her hand on Isadora's head several times. Janaína approaches and stands next to the two babies. Janaína claps her hands and asks as if she were smiling: “What was Isadora?” Isadora gets up and runs after Mirela, who is already walking with the object in her hand. Isadora cries. Janaína holds Isadora and takes another pot to give her. Isadora sits on the floor and stops crying (transcription of video recording performed on 11/17/2017).

In the episode described above, we observed that the babies disputed an object, which soon triggered the cry of one of them, Isadora. At that moment, teacher Janaína approached and talked to her. However, realizing that her attitude was not enough to stop the baby's crying, she took another object (a plastic pot), just like the one the two disputed, and offered it to her. Even though several objects and toys are available to babies, some, in particular, appear as attractive to the detriment of others, in the same way, that they tend to direct attention to those objects that are being manipulated by their peers (AMORIM; ANJOS; ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, 2012).

Upon noticing the dispute over the object, teacher Janaína has the attitude of giving another one and talking to Isadora, in an attempt to resolve the situation and make the baby stop crying. It is important to point out that, in such a situation, adults usually act to make more materials available for babies, but it is not just that. Objects are attractive; however, the actions that other babies or teachers exercise with these objects and the use they make of them also affects their behavior (AMORIM et al., 2012). For example, as another episode described below:

The circle continues, the babies are already sitting on the floor of the room. They have plastic pets in their hands. Ricardo is sitting on the floor and again starts crying. At the same time, Tiago has the big ball, and Danubia approaches and also wants the ball. She pulls it with her hands and he does the same. Tiago starts to cry. Danubia falls to the ground and starts crying too. Cremilda gets up and takes the ball to put it away. Janaína says: “It became the ball of discord!” Tiago shakes his legs as he looks at Cremilda and cries even more. She starts to walk towards him, but a few seconds later stops crying (video recording transcript taken on 09/18/2017).

In situations like this, crying hardly emerged as a form of communication for babies. When teacher Cremilda noticed the babies' dispute over the ball, she immediately approached and picked it up. At that moment, Tiago and Danubia cried more intensely and affected the teacher Janaína.

In this episode and many others, when there was a dispute between the babies over toys and objects, the teachers acted in this way, keeping the toys and objects, which showed that their main objective was to resolve the situation to the babies to stop crying, eliminating, in a way, the cause of the crying, as we observed in the speech of teacher Janaína: “It became the ball of discord!”

A similar result was found by Melchiori and Alves (2004). According to the authors, there were situations in which the teachers removed the objects that caused the dispute and conflict between the babies and claimed to do it calmly, and not in an authoritarian way, believing that these would be the most coherent actions in a situation like that. However, we cannot fail to consider how important it is for the teachers to understand that the quality of interactions is not guaranteed only through the materials, but mainly through the mediations that this other adult makes and the way in which the moments of interaction are conducted (BRASIL, 2010; BELO HORIZONTE, 2015). Thus, the organization of times, spaces, and materials are not enough; the presence of attentive adults committed to transforming the institutional environment into a place that favors the development of the autonomy of babies and small children is essential.

Regarding the organization of the environment and work in ECE, Horn (2004) considers that the teachers still prefer to carry out directed work, not planning the spaces to collective activities. They always have, as a bridge for this work, their direction in the activities, to the detriment of the children's choices or desires. This is because “&91#;...&93#; there is an intentionality of those who organize the spaces, designed mainly so that all activities revolve around the adult. Every time a situation escapes the teachers' control, this is reaffirmed” (HORN, 2004, p. 24). It is important to think about the organization of the environment in which babies are inserted and relate to others, since the influences of this social environment are decisive “&91#;...&93#; in the acquisition of superior psychological behaviors &91#;...&93#;” (GALVÃO, 2017, p. 40) and, consequently, in the integral development of babies.

Other moments of tension and contradictions are how the teachers re(acted) in the babies' crying, verifying their physical and biological needs and also distancing from them at the moment when the crying occurs. In this sense, a second criticism is highlighted regarding the way they interpreted crying, most of the time as a manifestation of physical and biological needs and as a “tantrum”, “whining” or “mulishness” and their re(actions) in front of crying.

Janaína, Laura, and Milena are with the babies in the nursery room. Laura is standing in front of the sink and is pouring colored water into the cups to put in the fridge. She explains to the babies that she is doing an ink-in-water experiment. Janaína and Milena are sitting on the floor with the babies. &91#;...&93#;. Ricardo starts to cry again and Janaína now sits him on her lap. He keeps crying. Laura walks around the room and brings the cup closer to the babies, including Ricardo. When she gets close to Ricardo, he wants to touch the glass. He extends his hand and Janaína stops him. At this point, he cries even more. Laura walks away. Janaína says to her: “Oh Laura, it must be hunger... it's hunger.” Ricardo looks at Laura and continues to cry. Janaína insists with the other babies to sit down. Everyone is standing. Ricardo continues to cry and Janaína starts to rock, even sitting, as if she was rocking the baby. Janaína says that she is going to give him water because he threw his banana away. Laura says, “In the morning I gave it to him, crumpled up.” Janaína gets on her knees and puts Ricardo on his feet. Then she gets up and takes him by the arms from behind and takes him to the back and lays him down there. Ricardo cries even more intensely. Janaína comes with the water bottle and offers it to her. Ricardo accepts and takes the water. &91#;...&93#;. Richard stops crying. Janaína is close to the other babies. Laura continues with the ink-in-water experiment. Ricardo remains lying down drinking the water (video recording transcription made on 09/18/2017).

While talking to the babies about the experiment she is doing, teacher Laura shows them the cups with water and ink. Babies get restless and want to get up and touch the cups. Baby Ricardo is observed to try to touch the cups as Laura brings the tray closer to him. The teacher Janaína prevents him from doing that, and the baby cries even more intensely.

Baby Ricardo maybe wanted to interact both with teacher Laura and with the proposed activity, which would perhaps be touching the cups to try and experience what was being proposed. When the teacher Janaína stopped him from doing what he possibly wanted, the baby cried even more. Then, teacher Janaína relates Ricardo’s crying to physical and biological needs when she says to teacher Laura: “Oh Laura, it must be hunger... it’s hunger.” Regarding crying, Pantalena (2010) found, in her research, that some teachers always related it to some physical need, demonstrating that they did not recognize this emotional expression as a form of expression of other needs and desires.

However, the teacher also offered him water and, soon after these actions, baby Ricardo stopped crying. In this sense, the possibility of the baby being hungry or thirsty cannot be ruled out, as the teacher pondered. Thus, babies' possibilities and capacities for exploration cannot be ignored, their desires to know, experiment, and experience the new and even to resist what they do not want or feel comfortable with.

We present here a moment in which the teachers (re)acted by distancing themselves or not approaching the babies and, possibly, interpreting the reaction as a “tantrum”, “whining” or “mulishness” and not as a form of communicating something they wanted or did not want.

The teachers are going to the park with the babies. Still in the hallway, the babies run. They go into the bathrooms and others into the library, they mess with what's on the walls and floor. They explore everything there is, in a few seconds, until they reach the park. Tiago, Geraldo, Guilherme, Paulo, and Melina entered the library and Janaína is inside trying to get them into the corridor so they can go to the park. The babies grumble and try to get back to where they were. Tiago screams and stamps his feet on the floor and starts crying. Janaína leads him to the hallway, but he goes back to the library. Ana Luísa enters the library and Janaína goes to her. Before that, she approaches the library door, holding Melina by the hand. Melina is kicking and whimpering. She drops to the floor and sits there on the library floor. Janaína lets go of her hand and go to Ana Luísa. Melina starts to cry. Janaína comes walking with Danubia and Isadora and leaves them in the hallway and tells them to go to the park. She meets Guilherme who is already returning and wants to enter the library again. Cremilda is there in the park trying to get the others to stay there. Janaína takes the hand of one of the twins and puts him in the hallway too, but he comes stamping his feet on the floor and mumbling. Now it's Melina's turn. She is sitting and has stopped crying. Janaína goes to her and takes the baby under her arms to carry her and puts her in the hallway. Melina starts crying and kicking. She is on the floor and lies there crying. Janaína closes the library door, takes the hand of one of the twins, and goes towards the park. She sings and says to Melina, “Let's go for a walk in the park while your wolf doesn't come, bye Melina, bye.” She lies there on the floor crying for over a minute. As she cries, she seems to call out to her mother: “Mam, mama.” Janaína says: “I'm going to close the door, okay?” Melina stands there crying. Teacher Laura arrives at the door of the nursery room and looks at what is happening with a scarred face and sees Janaína through the glass at the door of the park. She walks in and comes to get Melina. She comes singing and takes the baby by the hand and lifts her. Janaína says: “Look at that beautiful doll” (Melina had a doll in her hand). They go to the park. Janaína closes the door that gives access to the corridor and Melina stops crying (transcription of a video recording made on 26/10/2017).

In this episode, we saw that the teachers had the objective of taking the babies to the park; but as they left the room with them, still in the corridor, the babies entered the library, indicating that they wanted to stay there. We can emphasize the desire that everyone showed, through gestures and crying, to stay in the library space and the insistence by the teachers that they go to the park to carry out the activities of a routine already established. Ramos (2012) reflects on the importance of considering and welcoming babies' initiatives and games as a set of opportunities for the organization and development of pedagogical practices.

When teacher Janaína leaves the baby crying and moves away, she does not welcome her cry and its possible meaning; she most likely considered it as a “tantrum” and, therefore, she perhaps believed she did not need to worry so much, so she left Melina to continue crying. In similar situations, Melchiori and Alves (2004) found that, when the educators identified the cause of the babies' crying, one of their actions consisted of not worrying about the crying, observing it first, and only intervening when necessary.

Baby Melina cried a lot, to the point of catching the attention of teacher Laura, who was in the nursery room; noticing the fact, teacher Janaína, who was watching the baby through the glass of the door, went towards Melina and, as she approached the baby, talked to her and extended her hands to help her up. At that moment, the baby stopped crying and followed the teacher into the park. However, even if the teacher was observing the baby and verifying that she would not be in any situation of risk, she did not welcome the child's cry, which may indicate that she did not act responsively in this specific situation.

Santos (2012) showed that some teachers considered the crying of babies as a way of “drawing attention” and on this issue, the author emphasizes that “&91#;...&93#; what Wallon said about the power of emotion to mobilize the other” (SANTOS, 2012, p. 178). Therefore, we need to consider it, as something beyond a physical or biological need, to treat it as a way of communicating and/or expressing other needs, other desires, such as relating to the another, to leave or stay in a certain place, to be welcomed and understood by the other.

Through these results, we highlight the importance of carrying out further research with ECE professionals, to assist them in the construction of welcoming practices for babies in the context of daycare.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The analysis carried out enabled to expand the understanding of how the teachers and the ECE support assistant re(acted) to the babies' crying in their moments of interaction at the EMEI. Through a thorough analysis of the field diary and footage, we carried out the interpretation made in this text.

The research revealed four different ways of re(acting) in the babies' crying: approaching and talking to them; checking their physical and biological needs; keeping or offering them a toy or object, and somehow moving away or not approaching them at the moment when they cry. Analyzing and reflecting on these re(actions) of the teachers and the assistant, most of the time, they were attentive to the babies' crying expressions, trying to interact with them and re(act) to these expressions. In these moments, they presented an adequate posture of dialogue and approximation, demonstrating committed attitudes and in line with the purpose of the care and education work with babies proposed in the literature of the area and the guiding documents of ECE, both at the national and municipal levels.

However, some moments of tension and contradictions were also identified regarding their ways of re(acting) in the babies' crying. In this sense, we considered it pertinent to make some criticisms and reflections to contribute to the deconstruction of conceptions, perceptions, and pedagogical practices towards babies that do not match the ECE conceptions presented here and that this research identifies.

Two criticisms or points for reflection stand out: the first refers to the way they re(acted) in the babies crying, keeping or offering them some toy or object, and the intrinsic relationship of this crying with the organization of times, spaces, and materials for the group of babies at these times. The second criticism refers to the way they interpreted crying, most of the time, as a manifestation of physical and biological needs or as a “tantrum”, “whining” or “mulishness” and their re(actions) in these crying babies. In these moments, especially the teachers, sometimes distanced from the principles and purpose of ECE, disregarding, in a way, the babies' needs.

As the interactions take place in concrete conditions, we emphasize that the set of materials constructed in the research indicates that the teachers and the ECE support assistant acted to try to provide the babies' well-being; that is, they were doing the best they could. For this reason, the existence of several elements that largely influenced the way they cared for and educated babies, as well as responded to their manifestations, is highlighted: their conceptions about babies and their crying, the organization of the environment, the institution's political-pedagogical proposal, working conditions and the initial and continuing education of these professionals. Also, the teachers revealed that they knew each baby and how much, as far as possible, they were available to them, listening to their voices, their rhythms, and their movements to get to know them better and, therefore, to respond to their demands.

The expansion and strengthening of educational practices of reception and dialogue with babies who attend daycare centers and ECE schools can be enhanced with initial and continuing education actions built from the interaction with professionals directly involved in the work field. The research indicated that, as the teachers and assistants are listened to, and with them, interaction is established, the possibilities for them to problematize their daily routines and to be involved in the construction of significant pedagogical practices for and with the babies grow.

For professionals to re-signify their conceptions and practices in the babies' crying, it is important that they have opportunities to deepen their knowledge on the theme and that they start to consider crying as one of the relevant elements that should be better observed during their practices with babies. This deepening of knowledge can be provided, as already emphasized, in training moments that are supported by the discussion of situations that occurred in the context of each institution, ensuring professionals' spaces for listening and direct participation. Also, they involve theoretical knowledge of the fields of Psychology, Pedagogy, and Early Childhood Education, counting, if possible, with the participation of professionals from these areas. We also suggest that professionals pay attention to the way they organize times, spaces, and objects, seeking to provide babies with more moments of interactions with each other and with objects; and to avoid practices that cause discomfort to babies because they require long waiting times and behaviors that are not meaningful to them. Finally, are reinforced the indications, already present in the text, of the need for external spaces with green areas in Early Childhood Education institutions, and that babies can use them regularly; that several adults be ensured per grouping of babies that allows close and constant interactions.

We reiterate the indication of further research on the various ways of expression of babies in ECE and on the postures and actions of teachers and assistants, given the complexity of this work and how much it is still new and unknown, even among professionals in the area. Furthermore, the need for working conditions that allow teachers and assistants to have adequate time, space, and remuneration that enable planning, evaluation, and reflection on their work is affirmed. Without these conditions, it is unlikely that they will be able to rethink their practices and build work based on ethics, in which there is a continuous movement of reflection on the ways of acting and being in the interactions they establish with babies. This is because these individuals, with the alterity they carry, displace and challenge, demand presence, responsibility, and commitment, not only with themselves but with the whole of humanity.

REFERENCES

AGUIAR, Márcia A. S.; DOURADO, Luiz F. A BNCC na contramão do PNE 2014-2024: avaliação e perspectivas. Livro Eletrônico. Recife: ANPAE, 2018. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, Ana Rita S. A emoção na sala de aula. 7ª ed. Campinas: Papirus, 2009. [ Links ]

AMORIM, Kátia S.; VITÓRIA, Telma; ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, Maria Clotilde. Rede de significações: perspectiva para análise da inserção de bebês na creche. Cadernos de Pesquisa, n. 109, p. 115-144, mar. 2000. [ Links ]

AMORIM, Kátia S.; COSTA, Carolina A.; RODRIGUES, Luciana A.; MOURA, Gabriela G.; FERREIRA, Ludmilla D. P. M.O bebê e a construção de significações, em relações afetivas e contextos culturais diversos. Temas psicol., Ribeirão Preto, v. 20, n. 2, p. 309-326, dez. 2012. [ Links ]

AMORIM, Kátia S; ANJOS, Adriana M. dos; ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, Maria Clotilde. Processos interativos de bebês em creche. Psicol. Reflex. Crit ., v. 25, n. 2, p. 378-389, 2012. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, Maria Carmem. Especificidades da ação pedagógica com os bebês. In: SEMINÁRIO NACIONAL: CURRÍCULO EM MOVIMENTO, 2010, Belo Horizonte. Anais. Belo Horizonte2010 [ Links ]

BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de Conteúdo. Edições 70 São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1979. [ Links ]

BELO HORIZONTE. Ofício SMED-GCPF-GECEDI 277, de 13 de março de 2015 Dispõe sobre a reorganização dos quadros da Educação Infantil da Rede Municipal de Educação de BH. Gerência de Coordenação da Educação Infantil: Prefeitura Municipal de Belo Horizonte. 2015. [ Links ]

BELO HORIZONTE. Secretaria Municipal de Educação Portaria nº 275/SMED, de 26 de agosto de 2015Dispõe sobre critérios para a organização do Quadro de Professores na Educação Infantil da Rede Municipal de Educação-RME de Belo Horizonte e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial do Município: Belo Horizonte: 26 ago. 2015. [ Links ]

BELO HORIZONTE. Lei nº 11.132, de 18 de setembro de 2018 Estabelece a autonomia das Unidades Municipais de Educação Infantil - UMEIs, transformando-as em Escolas Municipais de Educação Infantil - EMEIs, cria o cargo comissionado de Diretor de EMEI, as funções públicas comissionadas de Vice-Diretor de EMEI e de Coordenador Pedagógico Geral, o cargo comissionado de Secretário Escolar, os cargos públicos de Bibliotecário Escolar e de Assistente Administrativo Educacional e dá outras providências. Belo Horizonte: Secretaria Municipal de Educação, 2018. [ Links ]

BELO HORIZONTE. Secretaria Municipal de Educação.Proposições curriculares para a Educação Infantil: eixos estruturadores Belo Horizonte: Prefeitura Municipal de Belo Horizonte, 2015. [ Links ]

BELO HORIZONTE. Secretaria Municipal de Educação.Proposições Curriculares para a Educação Infantil: fundamentosBelo Horizonte: Prefeitura Municipal de Belo Horizonte , 2014. [ Links ]

BITENCOURT, Laís C. A.; SILVA, Isabel O.O cuidado e educação das (os) bebês em contexto coletivo: a construção da experiência da auxiliar de apoio à educação infantil na interação com bebês e professorasZero-a-Seis, Florianópolis, v. 19, n. 36, p. 379-396, dez. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 9.394, de 23 de dezembro de 1996. Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Diário Oficial da República Federativa do Brasil, Brasília, 1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Brasília: SEB/CNE, 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Básica.Diretrizes curriculares nacionais para a Educação Infantil/Secretaria de Educação Básica. Brasília: MEC/SEB, 2010. [ Links ]

CAMPOS, Maria Malta; FULGRAFF, Jodete; WIGGERS, Verena.A qualidade da Educação Infantil brasileira: alguns resultados de pesquisa. Cadernos de Pesquisa , v. 36, n. 127, p. 87-128, jan./abr. 2006. [ Links ]

CAMPOS, Maria Malta. Educar e cuidar: questões sobre o perfil do profissional de Educação Infantil. In: MEC/SEF/COEDI. Por uma política de formação do profissional de Educação Infantil. Brasília, 1994. [ Links ]

CERISARA, Ana Beatriz. Educar e cuidar: por onde anda a Educação Infantil. Perspectiva, Florianópolis, v. 17, n. Especial, p. 11-21, jul./dez. 1999. [ Links ]

CESTARO, Patrícia M. R. Olhares para a formação dos cursos de Pedagogia das IES privadas de Juiz de Fora/MG: desdobramentos para o lugar da docência na creche. Tese (Doutorado). Juiz de Fora: UFJF, 2019. [ Links ]

DUBET, François. Sociologia da experiência. Paris: Seuil, 1994. Tradução: Fernando Tomaz. [ Links ]

DUMONT-PENA, Érica. Cuidar: relações sociais, técnicas e sentidos no contexto da Educação Infantil. Tese (Doutorado). Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2015. [ Links ]

ELTINK, Caroline F. Indícios utilizados por educadores para avaliar o processo de inserção de bebês em uma creche In: REUNIÃO ANUAL DA ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO E PESQUISA EM EDUCAÇÃO, 23, 2000. Caxambu. Anais eletrônicos. [ Links ]

FALK, Judit. (Org.). Educar os três primeiros anos: a experiência de Loczy. São Paulo: JM, 2011. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Ludmilla D. P. M. Expressões emocionais de bebês e práticas de cuidado e educação em diferentes contextos de desenvolvimento. 180f. Tese (Doutoradoem Psicologia). Ribeirão Preto: Universidade de São Paulo - USP, 2020. [ Links ]

FOCHI, Paulo S. Campos de Experiência: qual didática podemos construir. Caderno do Currículo de Belo Horizonte, 2019(no prelo). [ Links ]

FOCHI, Paulo S. “Mas os bebês fazem o quê no berçário, heim?” ocumentando ações de comunicação, autonomia e saber-fazer de crianças de 6 a 14 meses em contextos de vida coletiva. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Porto Alegre: UFRGS, 2013. [ Links ]

GALVÃO, Izabel. Henri Wallon: uma concepção dialética do desenvolvimento infantil. 23ª ed.Petrópolis: Vozes, 2017. [ Links ]

GALVÃO, Izabel. Henri Wallon: uma concepção dialética do desenvolvimento infantil . 4ª ed. Petrópolis: Vozes , 1995. [ Links ]

GEERTZ, Clifford. A interpretação das culturas. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara, 1989. [ Links ]

GONÇALVES, Fernanda; ROCHA, Eloisa A. C. Indicativos da produção científica para a educação dos bebês e crianças bem pequenas no contexto da educação infantil. Zero-a-seis, v. 19, n. 36, p. 397-410, jul./dez. 2017. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, Daniela O. Relações entre crianças e adultos no berçário de uma creche: o cuidado como ética. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. [ Links ]

GUIMARÃES, Nadya A.; HIRATA, Helena; SUGITA, Kurumi. Cuidado e cuidadoras: o trabalho do care no Brasil, França e Japão. In: HIRATA, Helena; GUIMARÃES, Nadya A. (Org.). Cuidado e Cuidadoras: as várias faces do trabalho do care. São Paulo: Atlas, 2012. [ Links ]

HADDAD, Lenira. Tensões universais envolvendo a questão do currículo para a Educação Infantil. In: DALBEN, Ângela; DINIZ, Júlio; LEAL, Leiva; SANTOS, Lucíola (Eds.). Convergências e tensões no campo da formação e do trabalho docente (p. 418-437). Belo Horizonte: Autêntica (Coleção Didática e Prática de ensino), 2010. [ Links ]

HORN, Maria da Graça S. Sabores, Cores e Sons. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2004. [ Links ]

KRAMER, Sonia. Formação de profissionais de educação infantil: questões e tensões. In: MACHADO Maria Lúcia A (Org.). Encontros e Desencontros em Educação Infantil3 ed. São Paulo: Cortez , 2008. p. 117-132. [ Links ]

MARANHÃO, Damaris G. O cuidado de si e do outro. Revista Educação, Número Temático Educação Infantil, p. 14-29, out. 2011. [ Links ]

MARQUES, Fernanda P. C. As expressões de choro dos bebês em uma Escola Municipal de Educação Infantil de Belo Horizonte. Dissertação (Mestradoem Educação). Faculdade de Educação. Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais , 2019. [ Links ]

MELCHIORI, Lígia E.; ALVES, Zélia M. M. B. Estratégias que educadoras de creche afirmam utilizar para lidar com o choro dos bebês. Interação em Psicologia, Curitiba, jun. 2004. [ Links ]

MINAYO, Maria Cecília S. Análise qualitativa: teoria, passos e fidedignidade. Ciênc. saúde coletiva, Rio de Janeiro, v. 17, n. 3, p. 621-626, 2012. [ Links ]

MOLINIER, Pascale; PAPERMAN, Patrícia. Descompartimentar a noção de cuidado? Revista Brasileira de Ciência Política, Brasília, n. 18, p. 43-57, set. 2015. [ Links ]

PANTALENA, Eliane S. O ingresso da criança na creche e os vínculos iniciais. Dissertação (Mestradoem Educação). Faculdade de Educação da USP. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 2010. [ Links ]

PEDROSA, Maria Isabel. Vamos observar cuidadosamente a criança no berçário In: RAMOS, Tacyana K.G.; ROSA, Ester C. S. (Orgs.). Os saberes e as falas dos bebês e suas professoras. 2ª ed. Belo Horizonte, 2012. p. 35-41. [ Links ]

PINO, Angel. As marcas do humano: as origens da constituição cultural da criança na perspectiva de Lev S. Vigotski. São Paulo: Cortez , 2005. [ Links ]

RAMOS, Tacyana K.G. Conhecendo a criança no berçário: suas tramas, investigações e interlocuções ativas. In: RAMOS, Tacyana K.G; ROSA, Ester C. S. (Orgs.). Os saberes e as falas dos bebês e suas professoras . 2ª ed.Belo Horizonte, 2012. p. 43-59. [ Links ]

RAMOS, Tacyana K.G. Um ambiente pedagógico significativo para a criança se desenvolver. In: RAMOS, Tacyana K.G; ROSA, Ester C. S. (Orgs.).Os saberes e as falas dos bebês e suas professoras . 2ª ed.Belo Horizonte, 2012. p. 58-77. [ Links ]

RICHTER, Sandra R. S.; BARBOSA, Maria Carmem S. Os bebês interrogam o currículo: as múltiplas linguagens na creche. Santa Maria: Educação (UFSM), 2010. p. 85-96. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Núbia A. S. Sentidos e significados sobre o choro das crianças nas creches públicas do município de Juiz de Fora/MGTese (Doutorado em Educação). Rio de Janeiro: UERJ, 2012. [ Links ]

SCHMITT, Rosinete V. “Mas eu não falo a língua deles”: as relações sociais de bebês num contexto de Educação Infantil. 2008. 216 f. Dissertação (Mestradoem Educação). Florianópolis: Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, 2008 . [ Links ]

SCHMITT, Rosinete V. As relações sociais entre professoras, bebês e crianças pequenas: contornos da ação docente. 2014. 282f. Tese (Doutoradoem Educação). Florianópolis: Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina , 2014 . [ Links ]

SILVA, Isabel O. Educação Infantil no Brasil. Pensar a Educação em Revista, Curitiba/Belo Horizonte, v. 2, n. 1, p. 03-33, 2016. [ Links ]

SILVA, Isabel O. Profissionais de creche no coração da cidade: a luta pelo reconhecimento profissional em Belo Horizonte. 2004. 297f. Tese (Doutoradoem Educação). Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais , 2004 . [ Links ]

TEIXEIRA SILVA, Elenice B. Do sentido filosófico à significação pedagógica do cuidado Revista Contemporânea de Educação, v. 12, n. 25, dez. 2017. [ Links ]

VASCONCELOS, Giselle S. M.; SIMÃO, Márcia B.; FERNANDES, Sonia C. L. Entrevista com Dra. Zoia Prestes. Zero-a-Seis , Florianópolis, v. 16, n. 30, p. 340-352, ago. 2014. [ Links ]

VIGOTSKI, Lev S. A Formação Social da Mente: o desenvolvimento dos processos psicológicos superiores. 7ª ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes , 2007. [ Links ]

VIGOTSKI, Lev S. O desenvolvimento psicológico na infância. 3ª ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes , 1998. [ Links ]

VIGOTSKI, Lev S. Obras escogidas IV. Madrid: Visor Distribuciones, 1996. (Trabalho original publicado entre 1932-1933). [ Links ]

WALLON, Henri. A evolução psicológica da criança. Lisboa: Edições 70, 1968. [ Links ]

WALLON, Henri. A evolução psicológica da criança . São Paulo: Martins Fontes , 2007. [ Links ]

WALLON, Henri. As origens do caráter na criança. São Paulo: Difusão europeia do livro, 1971. [ Links ]

WALLON, Henri. Do ato ao pensamento: ensaio de psicologia comparada. Petrópolis: Vozes , 2008. (Trabalho original publicado em 1942). [ Links ]

4It is important to note that the term in this work is used in the feminine, since most women occupy this role in ECE.

5These professionals, at the time of the research, held the position of “Education Support Assistant”, established in 2015 by the Municipal Department of Education of Belo Horizonte, and their function was to work in the classes of children up to 2 years old in EMEIs (BELO HORIZONTE, 2015). Recently, in 2019, SMED (Secretaria Municipal de Educação de Belo Horizonte Municipal Secretary of Education of Belo Horizonte) and MGS (Minas Gerais Administration and Services-Minas Gerais Administração e Serviços), responsible for hiring these professionals, through a regulation (REG/GEP/006), change this nomenclature for “Learning Support Assistant”. Available at: http://main.mgs.srv.br/arquivos/Norm_empregos_sal.pdf. Access on: 20 Oct. 2020. In this text, the generic name of “assistant” will be maintained to refer to the “support assistant of ECE”, since this was the name used at the time of the research.

6To better understand the tensions and disputes in the historical and political context of the BNCC's production, we suggest to read Cestaro's thesis (2019) and the dossier produced by the National Association for Research in Educational Policies and Administration - ANPAE Associação Nacional de Pesquisa em Políticas e Administração Educacional -, coordinated by Aguiar and Dourado (2018). In this dossier, evaluations are made that point out that the BNCC approved in 2017 is a document that goes against the National Education Plan - PNE Plano Nacional de Educação 2014-2024.

7The participants aged from 0 to 1 year and 6 months are considered babies, as defined by the BNCC (2017).

DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTEREST

3 This research was funded by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Received: December 27, 2020; Accepted: August 11, 2021

texto em

texto em