Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 30-Mayo-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469827048

ARTICLE

WHAT DOES TOURISM DO TO TEACH?: ETHNIC TOURISM IN PARANA AND ITS EDUCATIONAL ACTIONS

1 Universidade Estadual do Centro-Oeste (Unicentro). Irati, PR, Brasil. <poliana@unicentro.br>

2 Universidade de São Paulo (USP). São Paulo, SP, Brasil. <milan.puh1@gmail.com>

In this article we will discuss the articulations that some ethnic immigrant groups from Paraná carry out in the realization of ethnic tourism, and how their experiences can be seen as educational actions. It is a topic that is still not so explored as an interface between Tourism and Education, especially regarding to immigrant ethnic aspects. More specifically, the objective is to identify educational actions, tracing trends and themes along the trajectory of the creation of tourist activities, also taking into account the research carried out in the central region of Paraná, involving: Danube Swabians in Entre Rios (Guarapuava), Dutch in Carambeí and Castrolanda (Castro), Ukrainians in Prudentópolis and the Mennonites in Witmarsum (Palmeira). It is important to emphasize that this text brings the first results of a qualitative study that fulfills the second objective of offering feedback to the communities in question, since their particular experiences will be compared with each other, and complemented with academic research already carried out. Therefore, the main methods were the interviews conducted with some of the creators and directors of tourism programs during the field research, along with (non) participant observation, public documents made available by the community itself and academic research done thinking about tourism and its areas. adjacent. From there, other possibilities for better use of the ethnic-immigrant legacy in tourist articulations can be considered, as well as in the development of educational activities that will facilitate their execution.

Keywords: tourism and education; educational action; ethnic tourism; immigration

Neste artigo discutiremos as articulações que alguns grupos étnicos imigrantes paranaenses realizam na efetivação de um turismo étnico, e como as suas experiências, inclusive, podem ser pensadas enquanto ações educativas. Trata-se de um tema ainda pouco explorado na interface entre o Turismo e a Educação, especialmente no que se refere aos aspectos étnicos imigrantes. Especificamente, o objetivo deste trabalho é identificar as ações educativas, traçando tendências e temas ao longo da trajetória da criação de atividades turísticas, levando em consideração também as pesquisas feitas na região central do Paraná, envolvendo suábios do Danúbio em Entre Rios (Guarapuava), holandeses em Carambeí e Castrolanda (Castro), ucranianos em Prudentópolis e os menonitas em Witmarsum (Palmeira). É importante ressaltar que trazemos os primeiros resultados de um estudo qualitativo que cumpre o segundo objetivo deste texto, qual seja de oferecer devolutivas para as comunidades em questão, visto que as suas experiências particulares serão comparadas entre si e complementadas com pesquisas acadêmicas já realizadas. Os principais métodos empregados foram as entrevistas realizadas com alguns dos idealizadores e realizadores de programas turísticos durante a pesquisa de campo, junto com a observação (não)participante, documentos públicos disponibilizados pelas próprias comunidades e pesquisas acadêmicas feitas pensando o Turismo e suas áreas adjacentes. A partir desse ponto poderão ser pensadas outras possibilidades para um melhor aproveitamento do legado étnico-imigrante nas articulações turísticas e também na elaboração de atividades educativas que facilitarão a sua execução.

Palavras-chave: turismo e educação; ação educativa; turismo étnico; imigração

En este artículo discutiremos las articulaciones que algunos grupos étnicos inmigrantes de Paraná llevan a cabo en la realización del turismo étnico, y cómo sus experiencias pueden incluso concebirse como acciones educativas. Es un tema que aún se explora poco en la interfaz entre Turismo y Educación, especialmente en lo que respecta a los aspectos étnicos de los inmigrantes. Más específicamente, el objetivo es identificar acciones educativas, trazando tendencias y temas a lo largo de la trayectoria de la creación de actividades turísticas, teniendo en cuenta también la investigación realizada en la región central de Paraná, involucrando: suabos del Danubio en Entre Ríos (Guarapuava), holandeses en Carambeí y Castrolanda (Castro), ucranianos en Prudentópolis y menonitas en Witmarsum (Palmeira). Es importante resaltar que este texto trae los primeros resultados de un estudio cualitativo que cumple con el segundo objetivo de ofrecer retroalimentación a las comunidades en cuestión, ya que sus experiencias particulares serán comparadas entre sí, y complementadas con investigaciones académicas ya realizadas. Por tanto, los principales métodos fueron las entrevistas realizadas a algunos de los creadores y directores de programas turísticos durante la investigación de campo, junto con la observación (no) participante, los documentos públicos puestos a disposición por la propia comunidad y la investigación académica realizada pensando en el turismo y sus áreas adyacentes. A partir de ahí, se pueden considerar otras posibilidades para un mejor aprovechamiento del legado étnico-inmigrante en las articulaciones turísticas, así como en el desarrollo de actividades educativas que faciliten su ejecución.

Palabras clave: turismo y educación; acción educativa; turismo étnico; inmigración

INTRODUCTION

In this paper we present the preliminary results of the research conducted during the postdoctoral internship, carried out between 2019 and 2020, in a public higher education institution in Paraná ( Universidade do Centro-Oeste do Paraná, Unicentro). We have directed our attention, therefore, to the study of immigrant ethnicities in the field of Tourism, seeking to outline trends and issues with regard to their educational potential.

Regarding ethnicities, it is also important to highlight that the mosaic of ethnic groups is very specific to the region where the institution operates (centre and centre-south of the state of Paraná), since there exists a high cultural and linguistic diversity of immigrant groups of Slavic origin, as well as Germanic, both of which have significant internal cultural and religious differences. At just this stage, it seems worthwhile to us to mention the reflection of Souza (2018) who comments that the term ethnic is "fundamental to definied that an individual may have the same skin colour and hair type as the other, and possess cultural and social traits that distinguish them" (p. 27). In our experience, we are focusing on groups that basically come from Europe, with a very similar phenotypic appearance, differentiating themselves precisely due to the (self)perceived singular characteristics. We cannot forget to mention that we refer to groups that are inserted within a process of (multiple) migration that contributes to the reconstruction and renewal of thoughts and behaviours that value ethnic identification through difference, as Souza (2018) highlights.

By articulating these observations with those of Puh (2017), who studied the educative action in Ukrainian folklore in Brazil, specifically in the state of Paraná, the conclusion was reached that there has been a significant increase in academic productions on ethnic tourism in the state, the outcome of an effective growth of this phenomenon and its valorisation, lacking, however, a systematic approach that could highlight educational aspects present there. Melo and Cardozo (2015), Reis et al. (2017) and Reis, Cardozo and Princival (2018) also reach a close conclusion when discussing tourism, especially ethnic tourism, and education in its formal and informal meanings, going through not only specific or more comprehensive studies of ethnic contexts in tourism, but also documental analyses and bibliographic surveys in search of interpretative methods suitable for the local case study area in the context of Paraná. Also taking advantage of the reflections of Cardozo (2004) in this introductory moment, we explicit that ethnic tourism itself is still an area that does not have a very clear definition, relying on broader approaches that take into account a number of definitions of what would be the concept of ethnicity/ethnicities and their participation in tourism.

Likewise, we are aware that the concept is not the only one able to offer us a framework to analyse the practices of tourism activity, as different ethnic groups may present many more similarities than differences in their implementation of tourism. Thus, our view follows carefully so as not to reinforce disparities and also not to create an idea of incommensurability of comparative studies of different social and cultural groups, since, as Puh (2020) emphasizes, there is a strong process of orientation (or exoticization) of the cultures of countries that do not make up the structure of hegemonic nations in the Brazilian imaginary, thus being placed in a place of difficult access, impossibility of understanding and of little use or importance for academic or even educational studies. Therefore, one should be careful with cultural interpretations that move within multicultural frameworks which in Brazil have created an epistemic and interpretative framework, as well as an institutional one, rather conservative, reinforcing the logic of the so-called Racial Democracy which, in Puh's view (2020), planning and homogenizes the specific in the name of the undefined general.

As we understand the importance of reflections and educational and methodological proposals, we highlight the relevance of this production because it proposes an interdisciplinary training that will take concepts from (Touristic) Education to Tourism and Ethnic Studies. We consider, thus, that the tourism professionals will have a better knowledge of the intrinsic educative aspect of their actions, being equally interesting for the Educators, once the field visits and other pedagogical procedures of environmental studies are inserted in a mosaic of ethnic relations and tensions from which this kind of tourism is not exempt. Consequently, we consider that the training of future professionals in higher education may benefit from the meeting of these areas, even more if we consider the need to think about ethnic-racial relations nowadays.

We also expect to accomplish the second objective of this research, which is to promote the advancement of educational methodologies that will have a wider mobilization of knowledge of public policies, but also in collaboration with the knowledge and communitary dynamics. So, the future elaboration of touristic-educational actions in ethnic communities (of immigrant origin or not) will be able to benefit from all levels of academic action - research, teaching and extension in wider community.

Likewise, we will not hesitate to invest in the third objective, which is broader than the theme of the postdoctoral research, with which we want to expand the space that the discussion on education and training receives in the country, while considering the internal process of knowledge production. It is also worth highlighting that in an age marked by productivism and commercialisation of knowledge, a well-organised and incorporated reflection in the training of the students is an important element in strengthening the university culture, its diversification and the capacity of the public university to sustain its work through training. Finally, we believe that the educative action, elaborated from an internal policy of the communities that present ethnic identifications, may serve as a catalyst and articulator of other policies within the Brazilian society and the communities themselves.

Our hypothesis is based on the perception that the way a community articulates touristic activities depends on what it wants to teach about itself. In this regard, not only the demand that one has, but also the offer that one decides to create, depends on the public that the community will receive and what it will show about itself. Here we are missing precisely the aspect of the educative action in the communities that articulate and receive these tourist flows, something that we deduce from the conversations held with the communities, alongside the in loco visits and analysis of the academic production on the subject. This educative action is effective in the translation of narratives from the so-called Old Homeland into locally known terms, diversifying the situations, traditions and characters that are part of what it is to be a member of an immigrant ethnic community. In this sense, we understand that a bond is discursively created between different social actors, based on the collaborative work between official bodies (town halls, government authorities and university) and the community, by the fact of presenting an event of touristic nature in which cultural elements are explicit whose function is to teach. In other words, the educative action is also legitimised by the work jointly, maintaining contact between the groups outside the community ambiance. This dialectical relationship is important for us to understand how the ethnic groups appropriate their history as a kind of internal educative action (for the community) and external (of those who do not officially belong to it).

It should be noted that we are not talking about homogeneous ethnic-immigrant groups and that the main characteristic that marks them is the diversity of their socio-cultural organisation, their origin, their religious ties and their historical constitution. On the other hand, what unites them is their admittedly European origin, although many do not have a single homeland or corresponding nation and that in their territories there are other ethnic-racial groups, sometimes more invisible (invisibilised). Among the communities studied, we can perceive multiple migratory movements: the Danube Swabians from Entre Rios (city of Guarapuava) spent considerable time in other regions of Europe, such as those of Hungary, Croatia, Serbia and Romania in the lands granted to them during the existence of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, before arriving in Brazil in the early 1950s, while the German-Russian Mennonites from Witmarsum (city of Palmeira) left the region of Friesland, now divided between the Netherlands and Germany, settling in Russia to arrive in Brazil in the 1930s, going through an internal migration until they arrived in the city of Palmeira twenty years later. The Ukrainians of the city Prudentópolis came mainly at the turn of the 19th to 20th century from Galicia, a region shared between Ukraine and Poland, and the Dutch of Carambeí had immigrants who arrived at the same time from the south of the Netherlands, Frisia and the former colony of the Dutch East Indies, while those from Castrolanda (city of Castro) came mainly from two Dutch provinces: Drente and Overijssel, which also arrived in Brazil in the 1950s.

Another characteristic that brings them closer is the fact that they have settled in a more central inland region of the State of Paraná, being occupied with agricultural activities in the rural area, gradually joining complementary activities, as is the case of tourism, as already mentioned by Antônio and Cardozo (2009). The fact that these communities chose to introduce the touristic activity in the core of the local economy, more intensively in the last 15 years, puts them within a movement that we call ethnic-cultural valorisation and capitalization. Such characteristic, due to its recent value, is worth being studied, as was done by Soares and Sahr (2016a, 2016b) that trace the historical background of the creation of the Cooperative of Tourism (Cooptur), created in 2004, gathering precisely the aforementioned communities and municipalities.

At this particular point, we identify another characteristic, this one explicit and considered at the moment when the "Rural Tourism Cooperative Programme" chooses its participants: the cooperative tradition for which Soares and Sahr considered as decisive to guarantee the success of the enterprise. We also point out that this is an intrinsic characteristic of these communities that are based on cooperative work, bounded by ethnic ties of identity without which there would be no basis for the effectiveness of cooperative work (PUH, 2017). Therefore, strong ethnic ties, expressed in a cooperative working model, were crucial for these communities to be eligible for a government programme that would provide a basis for further organisation of ethnic activities. Moreover, in all communities, except in Prudentópolis (the main promoter of tourism activity is the City Hall and the Department of Tourism), cooperatives, both as commercial and legal entities, foster and support the development of tourism.

Curiously, two routes were created for this purpose, both based on an ethnic identification: the Slavo-Germanic Route, encompassing Witmarsum, Prudentópolis and Entre Rios, and the Dutch route, with Castrolanda, Carambeí and Arapoti (the latter city is located outside the State most central region and also outside the scope of the higher education institution itself). Both were created within the scope of the initial activities of Cooptur, whose member of the board affirmed that both the ethnic and cooperativism issues were considered, later enabling the adhesion of interested parties who do not necessarily have ethnic links with the communities. Besides Cooptur, we interviewed the director of the Department of Tourism of the city of Prudentópolis, the representative of the board of the Entre Rios Tourism Association, the director of the Witmarsum Historical Museum and also a tour guide, the coordinator of the Carambeí Historical Park and with the representative of the management of the Castrolanda Cultural Centre. Such conversations allowed us to have different perspectives of the realities observed in the communities during the in loco visits in order to understand how the touristic offer is accomplished. It was from this viewpoint that we started the search for the theoretical referential in the Tourism, Education and Ethnic Studies area, which we intended with the speeches of the interviewees and the materiality present in some of the tourist and cultural reception institutions. In the following lines we will present this approach, which will be at the same moment interpellated by the observations and general reflections obtained from the field research with the analysis of materiality and human interaction and from the interviews, and integrate them into a triangular theoretical and methodological proposal, based on the texts by Lincoln and Guba (1985).

THEORETICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

We begin our theoretical-methodological explanation with the establishment of relations between the area of Tourism and Education, but also with an indication of the levels of coverage that each area presents.

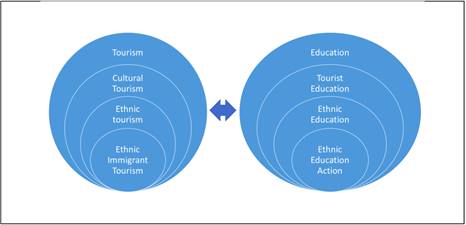

In Figure 1 we indicated the main approaches with which we have worked, the first being Tourism, within which we established the cultural category, in which we identified the Ethnic Tourism, more specifically the Ethnic-Immigrant Tourism, this being the tourism observed in the research field of the 5 communities dealt with in this article. On the other side, in the educative context, on a broader level we also have the area of Education itself that has a tourist element which, in our opinion, has the Ethnic Education that is composed of several ethnic educative actions of the immigrant groups. And we also see the connections between these two scopes, because the ethnic educative actions can be made effective as an ethnic-immigrant tourism and it itself always contains educative aspects in its planning and implementation. This means, on the one hand, that not every ethnic educative action aims at a tourist activity, but we consider that ethnic tourism proposals, even if in an unreflective and indirect way, presents a kind of ethnic and even tourist education. It is also worth considering the specific and localised aspects of this education and the actions that comprise it as an ethnic community production.

Methodologically, the proposal to investigate ethnic groups, and their tourism format, permeates simultaneously informal, non-formal and formal education. We recognize that there is already a reasonable discussion about these three modalities (cf. MARANDINO, 2017; BRUNO, 2014), being appropriate to comment on some aspects that can help us in further deepening and approaching their relationship with Tourism and Ethnic Studies. The author herself mentioned above brings in her title the following questioning: “Does it still make sense to propose the distinction between the terms formal, non-formal and informal education?", building a historical from which attempts to discuss. The division proposed by Gohn (1999, 2006) whose studies had a great reception in Brazil, consolidating in a certain way the comprehension that it is possible to work with only one modality when approaches specific or general cases in the scope of the education. However, this kind of idea has been severely criticised or reformulated, and other interpretative keys have been offered that can jointly contribute to a more forceful and adequate analysis and planning for education as a whole.

In that regard, we introduce the concept of hybridity because we want to highlight that these modalities can be overlapped, mixed or confused in a new social arrangement, which even allows a more detailed observation of the subject of the educative process itself, who has its own intentionalities and objectives. This concept is therefore of particular interest to us, since we will be highlighting communities and their concerns and intentions, allowing us to maintain a certain level of terminological vagueness, which is necessary for us to be able to approach the bibliographical readings and the data collected with greater ease and agility. Related to this concept is also that of learning by free choice, a concept which understands that there can be education based outside the external impositions of the macrostitutional level. It is also mentioned the continuum of formal, non-formal and informal experiences, idea elaborated by Rogers (2005) that proposes demarcation criteria within this spectrum that would not have, a priori, a clear division, these being: the way of organizing knowledge, the time of action development, the framework with which it is organized, the ways and the agents or subject that controls the practices and the experience itself and the intentionality that underlies it. These elements were taken into account in the analysis of the data obtained in the field research in which moments of tourism were observed in the ethnic communities, as well as in the interviews with the Agents who were responsible for its implementation. Since these are educative actions that have not been explored much yet, carried out in immigrant communities that have articulations with the private and public institutions, it is inevitable that there is a continuum between the three types of educative experiences.

Offering us some more bases to understand the continuum of possible kinds of education effected, Bruno (2014, p. 19) argues: "at one end of the continuum, the most decontextualized, lies formal education, whereas at the opposite end the word education disappears, as it refers to learning derived from everyday events, and gives way to informal learning". Therefore, being able to define what context is and how it is responsible for "show the face" of the education studied, helps to define its position within the continuum.

Approaching this reflection to the area of tourism, we cite the characteristics that Fonseca Filho, inspired by the work of Rebelo (1998), lists the three types of education:

Formal education: tourism developed in an institutionalized manner, inserted as a transversal theme or subject of the Basic School (Pre-school, Kindergarten,Elementary, Middle/Junior High and High School); or as a regular course of Professional and Higher Education ( Bachelors and Associates Degree [sic]); Non-formal education: through lectures, workshops, extracurricular courses, advertisements, events promoted by tourism companies, city halls, non-governmental organizations, trade associations, media, church, among others; with the aim of informing and preparing the population for tourism; Informal Education: that accomplished by the readings, participation, observation and influences of the tourist daily life, attitudes changes in the coexistence with the tourist phenomenon (FONSECA FILHO, 2007, p. 19)

Our complementation to this categorization is through the displacement of the gaze because it is an organized and systematized community educational proposal and that, usually, takes place outside the framework of the formal education system, but it can also lead to a process that will result in a greater institutional formality of educational actions (PUH, 2017). Therefore, at this we would like to do an invitation to forward our approach from a more top-down view, that is, from the macro (Governament: Education formal decontextualized) that impinges on the micro (Community: contextualized non-formal education) to a different one in which we research how the community generates within itself the educative actions that initially are from the more informal ambience. Over time these actions are incorporated into some non-formal education elements with the formation of associations, cooperatives, joint ventures with public authorities (municipalities, states), being prepared for the welcoming of tourists, but not necessarily reaching the sphere of a formalization as a course or discipline. The nearest to a curricular educational formalisation was the foundation of Cooptur, of the Cultural Institutions (Museums) and the Associations of the tourist agents/workers, but whose main function is not strictly Education, but Tourism. In a certain way, the educative actions carried out in the tourist activity of the community seem to us to pass unobserved as a legitimate teaching-learning mode which may be partially incorporated in the various teaching spheres, especially in the Tourism courses, since it is a way of knowledge production, although not scientific, but it is based on experience and that in dialogue with the academy may bring benefits for both instances.

At this moment we should differentiate: a) pedagogical tourism, classified as "every educational activity that happens outside the school physical space and that can be identified through an excursion, trip or technical visit" (MATOS, 2012, p. 3); b) tourism education, which "presents the importance of preserving values related to culture and the natural environment" (FONSECA FILHO, 2007, p. 10) and c) education for tourism, which preocupes "about the impacts of tourism on the natural and socio-cultural environment, on the economy and also to weave discourses in favour of the professionalization of the area" (FONSECA FILHO, 2007, p. 11). It should be mentioned that often the education for tourism is approached and tensioned with heritage education, introducing here the reflection of Cerqueira (2005) that defines two focuses of action for this modality that allows us its better integration in our discussion:

On its turn, the education of the community in broad terms, is carried out in various ways. The most prominent is the cultural tourism, which should be understood not only as a leisure activity, but also as a pedagogical activity of citizenship education - a distinctive education, as it is open to dialogue between local and global, because the heritage education is targeted not only to local tourists, but also to those coming from other regions of the country or abroad. Tourism, therefore, may be an educational activity on a planetary scale, with significant contribution to the development of awareness, policies and public actions for the preservation of cultural heritage. (CERQUEIRA, 2005, p. 99)

The educative actions are going in the direction of a tourism education that, besides attracting financial resources and guaranteeing the sustenance of the families, also assists in the consolidation and preservation of ethnic values. But it is also discussed, within its propelling entities, the relevant aspects of education for tourism, since the local population quickly begins to perceive the harmful effects of an expanding tourism that brings in large contingents of visitors, also always indicating community members who undergo complementary training to be able to act as tourism agents. And, on the other hand, all the communities attest to frequently receive groups that integrate pedagogical tourisms with visits from schools of the municipalities and also from nearby urban centres and of the state of Paraná itself (Curitiba, Ponta Grossa, Guarapuava).

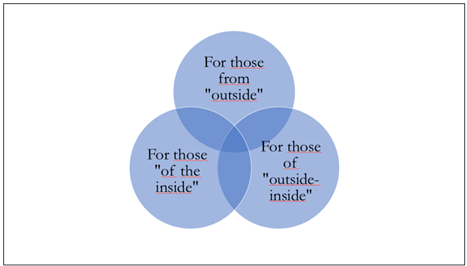

Further into the theoretical aspects of the tourism-education interface observed in the visits and in our conversations with community agents, we can perceive the structuration of three tourism modalities that, although not explicitly, depends on the kind of public served: the local community, the external visitors from Brazil and the visitors of their ethnic group, but from outside Brazil. And in this we also formulate three types of educative action that we illustrated in Figure 2:

Each of these types is implemented in accordance with the needs of the moment and the profile of the visiting group. When it is a tourist group that is outside the ethnic and/or local scope of the communities, that is, that has no knowledge about the features of that ethnic group, but also does not know the place, the community presents a more generic, explanatory articulation. As a general rule is most explicit in the cultural institutions that are prepared to receive this kind of tourist for whom it is assumed that he/she does not have any knowledge of the local reality, heritage and identity. It seems to be the most used in cultural institutions, but also in those of tourist welcoming, and we have not yet detected a difference in the production of tourist or educative materials regarding a more sensitive approach to the visitor's profile. We observed, on the other hand, that in the treatment of some groups the strategies and practices were directed elsewhere, as was the case when they were visited by groups of Primary and Secondary School students for whom our interlocutors said that they represented a specific, i.e. differentiated, group. In this respect, we think that it is more about pedagogical tourism, since it is assumed that there is a minimum local knowledge that allows some comments more directed to the ethnic aspect, thus, for example, in Entre Rios and Witmarsum the difference between German or Germanic and Swabian or Mennonite is clarified as singular denominations of these communities. The same also seems to occur with other groups of the so-called leisure tourism from the neighbouring municipalities who frequently visit these communities from their local area, which in itself already offers this basic knowledge about the ethnic groups and their singularities.

From then on, we started the research and questioned the agents involved about the changes in the treatment given to those who came from a certain way inside, like the groups now mentioned, but also discussing about the educational actions we noticed in the tourist visits of the nearby ethnic groups that certainly had the knowledge of the identity, social and even historical characteristics of the Germans, Dutch, Ukrainian, Russians etc. What these non-Brazilian groups did not know was the national and especially local reality of the constitution of the communities and their internal specificities, largely new. That is why we decided to call the attitude and the educative actions aimed at these groups " outside-inside ", since the visitor was coming from far away, outside the country and the local reality, but within the ethnic scope that enabled the setting up of another interaction. In this case there is always some common between those who visit and those who are welcomed that allows the creation of another tourist-educative relationship, although it also involves processes of sense negotiation between what is already known and what is being learned. However, both those who are within and those who are outside-inside were not necessarily contemplated in the materiality of tourist education in the institutions and entities (flyers, descriptive plates of museums, official pages on the web, to mention a few examples), preferring to include them when it was perceived that the case called for such an intervention, once the standardized tourist actions would not be able to offer an adequate service.

We can cite three cases that aroused our curiosity and led us to a more intense reflection on this triple division. The first situation occurred when we visited the Mill that is part of the Cultural Centre of Castrolanda, a place that at the time hosted the organisation of a "mixed" wedding, in which one person was from the community and one was not. One of the effects of the event was a diversity of visitors from inside and also from outside that place, materialized in the questions of the guide who oriented the visitation in another place that integrates the Center - the Historical Museum. By indicating their origin, each visitor received a different instruction about which part of the exhibition he or she liked more, and we even heard comments from the employee that for those inside there were new elements in the exhibition, dismissing this group, while the group from outside received an explanation to localise them in the region and also an introduction to the characteristics of the Dutch immigrants. The second situation happened in a visit to a restaurant inside the Witmarsum colony, at that moment hosting a group of Germans coming from outside Brazil. They were served a lunch that the owner explained was typical in the community, but was quickly questioned by two visitors about the presence on the menu of borchtch soup, which in their opinion was not part of the German world. The comment caused the owner of the restaurant, together with his wife, to have to make an intervention to the entire group, explaining the historical specificities of the Mennonites, which somewhat disrupted the dynamics of the group, and caused the guide to start acting to give further explanations and a new contextualization that had not been done before. We commented on this with the owner, who noted that it was a recurrence in the visits of the external Germanic ethnic groups who are faced with ethnic differences, something that the director of the Witmarsum Museum himself confirmed when referring to the general public coming from outside and who have other expectations of "typically" German foods that were not traditionally served in the community, such as pork knuckle. The third situation in which we came up with differentiated and oscillating educative actions was when we visited the Historic Museum of Entre Rios, on the occasion, with a group of students, most of them of Croatian descent. We were welcomed in the Museum by the historical assistant who, knowing the historical origins of the group, coming from the same region of a large part of Swabians originating from Croatia, modified his speech in order to conduct a different guided tour, even explicitly indicating that one of the authors of this article was an expert in immigration issues and that, therefore, he would count on his help, thus eliminating the necessity of a historical (and) introductory approach, something that was repeated in the restaurant also located in the colony, whose owner was warned of our "outside-inside" condition.

These events happened unexpectedly, diverting our attention to the changes in the way the tourist activity also occurred as an educational action, both in institutional and non-institutional spaces. It became noticeable that it was also about explicit and implicit actions, surrounded by sayings and non-sayings that are not included in the official tourism planning. In this, we reflect on what Peirano (1990) calls the tricks of chance, thinking of an ethnography attentive to unexpected situations that create new subjects for those who propose to observe. In the case of the author, whose research comes from the field of sociology and anthropology, the mishap should be understood as an incentive for a possible new vision that, in the future, may be inserted in methodological studies in a more consistent and systematic way. We understand this epistemological attitude as a possibility that instigates more attentive researchers to look at what is not visible or evident while doing an ethnography in field trips. Usually this type of occurrence is not taken into consideration as data, as it was neither planned nor part of a systematic observation procedure, remaining in the realm of the occasional. In our opinion, in the case of communities with which researchers are not very familiar, this kind of phenomenon is more common, as there are no expectations from both the researcher and the "researched". Here the same author brings a curious reflection in saying that:

More appropriate, then perhaps, is to see in chance the allowable residue of the "irrationality" of our academic world; or, in other words, the "imponderables of real life" which do not invalidate but, on the contrary, enrich and give that human dimension essential to the understanding of sociological phenomena (PEIRANO, 1990, p. 19).

What we need to know, no doubt, is how to discern those events and articulate them within the academic-scientific possibilities of study, especially considering that educative action in ethnic tourism is not necessarily prescribed, but practiced and experienced in daily social interaction. Therefore, raising this community experience and its knowledge in dialogue with the precepts of academic knowledge production to a level of greater visibility will enable us to better understand the details of the internal and external educative dynamics yet to be contemplated in public policies. In this regard, it is worth returning to the triangular theoretical-methodological proposal called by Lincoln and Guba (1985) as naturalistic for its willingness to a greater insertion in the observed ambience, in the "nature" of the social and cultural phenomenon, and that allowed us to analyze: a) what we read - the material produced by the community about itself and its activities and that produced at the university; b) what we heard - the interviews conducted with community members; and c) what we saw and what we did - in that we experienced an observation experience (not necessarily) participatory.

HOW TOURISM TEACHES: REFLECTIVE PERSPECTIVES ON A TOURISM EDUCATION IN ETHNIC-IMMIGRANT COMMUNITIES.

In this topic, we will explore some of the perspectives on educative actions in the context of ethnic tourism that were possible to be understood through our analyses in the five communities mentioned.

The first perspective, focused on aspects of the choice of what we may call educative agents of tourism, occurs as the internal articulation in favour of the ethnic tourist offer that aims at the selection of tourist agents (guides or workers in tourist institutions/establishments) who are from the community and who have ethnic roots and, therefore, cultural and economic heritage that can be enjoyed and transformed by incorporating the offer. We can observe that Cooptur itself had this proposal initially, but later allowed the participation of agents not necessarily rooted in the ethnic group, as commented by Soares and Sahr (2016). This tendency to choose agents from the community still prevails as an internal strategy, being that, for example, we discovered in conversation in the Department of Tourism of Prudentópolis that there is a current job to boost the opening of restaurants that could regularly offer to visitors typical foods, a type of tourist action that until recently was more restricted , i.e., it aims at an opening outside the context of the community and for a professionalization of the tourist offer independent of possible internal combinations. In this case, the family cookery ended up leaving the informality and entered in a process of professionalization of the ethnic group, which understands that it is necessary to offer this possibility to the visitor, and in a certain way, assigning the responsibility to explain and present the Paraná Ukrainian culture through the cookery. Thus, it is taught not only in visits to houses and restaurants that prepare food punctually, but also in restaurants that, besides the more standardized food, end up serving as a more permanent place of educative action, necessary for a more consistent linguistic education.

This kind of choice, for example, is stronger in the case of tourist guides, since it is assumed that someone from the inside can better explain and present the community and its cultural and natural heritage to the visitor. We observed this ethnic filter in all five communities, which leads us to think how much the assumption that knowledge received through education and coexistence can be more valuable than that studied and learned. This is what we call the ethnization of the profession in which training and consequently the educative actions result from the insertion of the ethnic element as a basis to which the interest, the aptitude and other psychosocial characteristics of the individual are added. This phenomenon also presupposes the work of the community in detecting and choosing certain members who are considered to have potential, which allows for greater possibilities of employability, something our interviewees commented on in both Witmarsum and Entre Rios. In this sense, the conception of training for tourism helps to understand the process of its professionalisation and the containment of possible effects that are considered undesirable. There are also, of course, ethnic tourism workers who receive formal training in schools and institutes focused on the area and which do not necessarily depend on a referral from the community. These possibilities denote a certain mosaic of ethnic policies in tourism training and tourist education that need to be further studied and taken into consideration in a possible formation of local public policies.

Another perspective of ethnic tourism permeated by specific educative actions is the one that indicates a change of vision about the community that we call "ethnic correctness and complementation", in which each one of the communities teaches outsiders what makes it unique in comparison with the others of its ethnic group. In this case, a greater context is offered about its characteristics, which brings its educational actions close to informal learning within the educational continuum. It was perceived that this action as a procedure is more informal and internal to the community when one realises the possibility of not having to incur in a standardised explanation. We can observe the example of the Danube Swabians in the case of the Entre Rios Historical Museum, in which museological devices are introduced that present the visitor with identity and historical aspects that distinguish the Danube Swabians as a specific Germanic ethnic group. This standardized procedure of museums with subtitles of the exhibits and contextual texts fits into the formal spectrum of education, while the explanation of the educative sector staff is less formal, and even informal when it is necessary to explain something that is not externally defined in society or easy to assimilate in the overall context, as when it comes to explaining what it is to be a Danube Swabian in that specific place.

But curiously not all tourist establishments in the community invest in this type of teaching, and prefer to keep the generic German term. Although our interviewee who participates in the colony's Tourism Association affirms that there is a differentiated internal procedure that acts in the modification of stereotypes of the Germanic community, it is not explicit to the extent of being a part of institutional publications, protocols or policies. This procedure of correction or complementation of the ethnic perception of that community depends again on the assessment of how it is inside or outside the representative, stating that there is an increasing number of visitors who appear in the community precisely because of the ethnic offer (cookery, music, miscellaneous events, etc.). In the case of the Dutch community, we noticed a difference between the Carambeí Historical Park, that presents a wider educative approach in terms of citing "immigrant communities", and the Castrolanda Cultural Center, in which the Dutch element prevails. This is explained by the historical constitution of the two communities, being that in Carambeí there was, in fact, a greater immigration of different ethnic groups in the city, among which are the Dutch, whose presence as an ethnicity presents itself as preponderant. In the educative actions of the Historical Park this is contextualized and highlighted, while in the case of Castrolanda Cultural Center there is no need for further explanations about the Dutch characteristics, but about the specificities of its constitution in Castro.

Another internal characteristic of the communities that can define the perspective taken at the time of creation and implementation is the place of centrality that certain entities assume in them. While the Department of Tourism in Prudentópolis is an important factor of the tourist life, in Witmarsum the responsibility of this work is more of the Association of the Residents of Witmarsum, who assumes this function since there was no formalization of a local group of tourism managers, as pointed out by Holm et al. (2017). In Entre Rios, a Tourism Association was created in 2019, and in Carambeí, Cooptur itself functions. In Castrolanda we were informed that tourism is guided by the Cultural Centre and by the Castrolanda Agroindustrial Cooperative itself. In all cases but Prudentópolis, the associations, as well as tourism itself, depends on the participation of the agricultural cooperatives as the economically strongest entities in the community.

We mention these differences in order to highlight the discussion of agency in the community processes of development of educative actions, since we detect in the speeches that the less professionalized tourism and the presence of entities directly involved with this activity, the greater the space for the multiplicity of actions that fall predominantly within a hybrid education between non-formal and informal. However, this multiplicity is also usually more veiled and diluted among the various small agents who directly effect ethnic tourism. On the other hand, they are all integrated into a larger tourist cooperative (Cooptur) that helps guide and propose activities that may involve ethnic elements or not, which seems to question the way in which communities present themselves outwardly and inwardly, even if this is more present at the official level. Therefore, the closer the entity that makes tourism and the community are, the more present is their internal way of presenting themselves and teaching others who they are and how they wish to be perceived. Consequently, the visitor who knows it, in a way, has more "freedom" of learning, since he is not inserted exclusively within a formal educational proposal, being able to go through and create the understanding of ethnicities more own or autonomous.

A tourist activity very directly linked to educative actions is that of pedagogical tourism that is carried out in the places studied, with the field visit activities that all our interlocutors from the five communities seemed to reinforce in their speeches and in the educative actions cited as referring to "teaching about ethnicity". In a certain way, there was a will to show us that school visits in institutions of cultural promotion and preservation (Historical Museums in Witmarsum, Entre Rios and Carambei and Historical Park in Castrolanda) were the appropriate places for a pedagogical work to be carried out, fitting obviously within a much more formalized educative proposal. And here it is again important to reinforce the division between the more formalised educative actions and directed towards teaching about oneself, like the mentioned school visits, and the more informal or non-formal and indirect actions that happen when the so-called leisure tourism takes place in which learning would take place by free choice. It would be essential to study more the pedagogical tourism, once it presents protocols and methods to carry out activities of audience formation, as we have seen mentioned in the case of Carambeí Historical Park. However, this was not our focus in the interviews, material studies and observations, since these were educational actions that had already been formalised and adapted to an expected type of public. Our concern centred on the less explicit actions, being precisely adapted to the public served at the time, remaining more within the scope of training the community and agents working in ethnic tourism.

The specificities of each community becomes more apparent when confronted with the different levels of proximity and distance of those they visit, constantly creating new forms of dialogue and showing what they want from themselves. In this respect, we observe that a certain standardisation of the reception of the public, more intensely present in educational tourism, ends up bringing closer and homogenising the educational actions of ethnic communities, often reinforcing in our presence their more formal approach. In this way, we expect this from the understanding and vision that was had of our presence and function as almost "supervisors" of the "correct" application of the educational precepts by the communities. There were some difficulties in the contact and explanation of the research objectives, since it was not expected from us, academic researchers, an interest in community actions and policies that were not exclusively based on the science produced in the formal university environment. Similar effects, regarding the devaluation of knowledge and educative actions made in non-formal community contexts, were perceived by Puh (2017) in research on folklore groups from three Ukrainian communities in Paraná.

The intention of this research was to understand the creation and implementation of a more autonomous community policy regarding language and culture education, which is not so different from what happens when groups of people visit a certain locality in order to "get to know" its culture, language, customs etc., demanding a community policy to meet or even create this demand. Once again, this is an activity - ethnic folklore, which is also in a place that we may call more hybridized, since there has not yet been a definitive formalization of the educative process, to the point of creating "folklore schools" or teaching institutions that would have a scientifically proven method, and the same goes for possible "schools/methods" of doing ethnic tourism. Therefore, (non-participant) observation practices were essential for us to recognize practices not made explicit by the community in the interviews and documentation provided, complementing our study and providing us with an effective ways to overcome some communication hurdles in later conversations and analysis of the discourses in circulation.

Finally, the cooperativism as an ethnic characteristic was also studied and reflected in our research, including thinking about the internal dynamics of each location as explored by Holm et al. (2017). It seems that one could very easily exchange the term ethnic for cooperativist when thinking about actions and how tourism agents articulate themselves, especially within Cooptur, however, in our research, a different ethnic way of organizing cooperative work was highlighted. For example, in Prudentópolis there is no central and hegemonic cooperative, at least when thinking about tourism, while in Entre Rios, Witmarsum, and Castrolanda the community cooperatives are large and very structured. This causes the ethnic characteristics to stand out less in a general way, and equally specific when we think about the organization and implementation of educative actions. This demonstrates that the ethnicity of the communities can be overshadowed by the presence of professionalized cooperativism, and consequently the educative actions in tourism undergo a process of more formalization and structuring. In short, when it comes to the business, the ethnic element and its specificities that affect a way of teaching and disseminating its own culture usually give way to the homogenization of the entrepreneurial culture, since there is a greater explicitness of what should be done and said, allowing less interaction unmediated by formal education between parties: the community and its visitors, regardless of whether they are from inside or outside.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

In this last section of our text we want to resume the issues presented previously, considering the existing possibilities in the exploitation of the community production of knowledge from an ethnic tourism more aware and able to transmit, besides incorporating and discussing, the specificities and similarities between the addressed immigrant groups and also in relation to the general public not belonging to them, ethnically or locally.

First of all we would like to emphasize that it is necessary to better understand the non-formalized and non-institutional dynamics that permeate the ethnic communities so that future tourist actions can be taken advantage of as interactions in which one learns and also learns to teach. There is still not much academic research that takes into consideration a (tourist) education that takes place in the communities that receive visits also because of their (in)tangible cultural heritage and that could be discussed and used in the various formations (academic and/or professional). It is important that the community memory of how to present itself to the different audiences, the insiders, the outsiders and the outsiders-insiders, is preserved and respected when the more formal tourist activities in its institutions are being thought. We return to the quote by Cerqueira (2005, p. 100) who considers the heritage education as a possibility to "sensitize the communities about the importance of preserve their memory; more than that, it seeks to encourage a reflection about the memories of the different social groups, so that it is perceived that heritage is not only the beautiful and remarkable monument about the past of some elites". In a way, community memory is also a structuring heritage of the whole community and the manner in which it would and could present itself to the world, taking better advantage of the dialogue with non-ethnic members. And as Antônio and Cardozo (2009), ethnic tourism is an efficient method of distinguishing the tourist offer in rural communities that do not have heritage or public facilities that are capable of attracting large audiences of visitors. It is a matter here of knowing better how to employ this offer to teach the people who visit them to respect more their space, their history and their way of existing, ensuring that there is a greater involvement of those who make leisure tourism, and not only pedagogical, in the preservation and promotion of Brazilian cultural diversity. Educating people for the recognition that in Brazil multiculturalism does not mean simply a flattening of differences in the name of the mixture of races and ethnicities, but a will to deepen and improve the study of the historical, social, cultural and political processes of each of its parts, may result in a possible reversal of the "orientalism in a Brazilian way" that Puh (2020) mentions, and that prevents the Brazilian people to see themselves in the multiple potentialities of being and existing.

Undoubtedly, there are challenges to think about educational actions that have a certain formalization, but without covering and invisibilizing the production of knowledge that happens at local and community level, allowing a feedback between the various educations within the already mentioned educational continuum. In this sense, the university has an important place in promoting experiences at the level of research, teaching and extension that can speak better with what is done in the communities, whether they are ethnic immigrants or not. In this scenario, universities located in the vicinity of different types of communities have the special advantage of being able to see up close what those around them are doing, thinking about methodologies that allow them to identify phenomena that are not visible at first sight. Due to this, the idea of chance in observation can be an interesting possibility for researchers and scholars who are distant or eventually a little closer to the communities to realize what elements of their research would merit a joint work with tourist agents, for example. We also hope that, by knowing better how to serve the different stakeholders (inside and outside and the whole continuum between these two poles), ways of attracting them and offering a differentiated and more suitable ethnic experience in the sense of causing significant learning about that locality and community visited will also be considered. Finishing this report and the indications of some future necessities of thinking more about the educative aspect of ethnic community tourism, we call on future researchers to describe and reflect about the ways of teaching others who we are, what we want and where we are in the time and the space.

REFERENCES

ANTONIO, F. M.; CARDOZO, P. F. Turismo étnico como forma de diferenciação da oferta turística do meio rural: a comunidade ucraniana de Linha Esperança - Prudentópolis/PR. In: FÓRUM INTERNACIONAL DE TURISMO DO IGUASSU, 3., 2009, Foz do Iguaçu, PR..Anais [...]. Foz do Iguaçu, PR. 2009. [ Links ]

BRUNO, A. Educação formal, não formal e informal: da trilogia aos cruzamentos, dos hibridismos a outros contributos. Medi@ções, [S. l.], v. 2, n. 2, p. 10-25, 2014. [ Links ]

MELO, A.; CARDOZO, P. F. Patrimônio, turismo cultural e educação patrimonial. Educação & sociedade, Campinas, SP, v. 36, n. 133, p. 1059-1075, 2015. [ Links ]

CARDOZO, P. F. Possibilidades e limitações do turismo étnico: a presença árabe em Foz do Iguaçu. Orientadora: Susana de Araújo Gastal. 2004. 169 f.Dissertação (Mestrado em Turismo) - Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul, 2004. [ Links ]

CERQUEIRA F. V. Patrimônio Cultural, Escola, Cidadania e Desenvolvimento Sustentável. Diálogos, Maringá, PR, v. 9, n. 1, p. 91-109, 2005. [ Links ]

REIS, D. G.; MANDUCA, C.; BAPTISTA, L.; CARDOZO, P. F. TURISMO E INTERPRETAÇÃO: uma forma de valorização e promoção do patrimônio cultural e natural do Recanto dos Papagaios, Brasil. TURyDES: Turismo y desarollo local sostenible, v. 10, p. online, 2017. [ Links ]

FONSECA FILHO, A. S. Educação e turismo: reflexões para elaboração de uma Educação Turística. Revista brasileira de pesquisa em turismo, São Paulo, v. 1, n. 1, p. 5-33, 2007. [ Links ]

HOLM, C. C.; CARDOZO, P. F.; FERNANDES, D. L.; SOARES, J. G. Planejamento participativo do turismo e seus desafios: a aplicação dos princípios de Elinor Ostrom na colônia Witmarsum-PR, Brasil. Rosa dos Ventos, Caxias do Sul, RS, v. 9, n. 3, p. 457-471, 2017. [ Links ]

REIS, D. G.; CARDOZO, P. F.; PRINCIVAL, V. C. Educação patrimonial histórico-crítica: modelo de proposta pedagógica para Irati-PR. Crítica educativa, Sorocaba, SP, v. 3, p. 311-322, 2018. [ Links ]

GOHN, M. G. Educação não formal, participação da sociedade civil e estruturas colegiadas nas escolas. Ensaio: avaliação e políticas públicas em educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 14, n. 50, p. 27-38, 2006. [ Links ]

GOHN, M. G. Educação não-formal e cultura política: impactos sobre o associativismo do terceiro setor. São Paulo: Cortez, 1999. [ Links ]

LINCOLN, Y. S.; GUBA, E. G. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1985. [ Links ]

MATOS, F. C. Turismo Pedagógico: o estudo do meio como ferramenta fomentadora do currículo escolar. In: SEMINÁRIO DE PESQUISA EM TURSIMO DO MERCOSUL (SEMINTUR), 7., 2012, Caxias do Sul, RS. Anais [...]. Caxias do Sul: Universidade de Caxias do Sul(UCS), 2012. [ Links ]

MARANDINO, M. et al. Faz sentido ainda propor a separação entre os termos educação formal, não formal e informal? Ciênc. Educ., Bauru, v. 23, n. 4, p. 811-816, 2017. [ Links ]

PEIRANO, M. G. S. Artimanhas do acaso. Anuário Antropológico, Brasília, v. 14, n. 1, p. 9-21, 1990. [ Links ]

PUH, M. “Tudo junto e misturado?”: as contribuições e os limites do multiculturalismo no ensino de línguas. Revista El Toldo de Astier: propuestas y estudios sobre enseñanza de la lengua y la literatura, La Plata, ano 11, n. 20-21, p. 415-432, 2020. [ Links ]

PUH, M. Folclore como ação educativa na constituição de políticas linguísticas em e para comunidades rurais de origem ucraniana na Croácia e no Brasil. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade de São Paulo. 2017. [ Links ]

ROGERS, A. Non formal education: flexible schooling or participatory education? New York: Springer Science, 2005. [ Links ]

SOUZA, N. N. S. Turismo étnico: discutindo conceitos. In: SOUZA, N. N. S.; PINHEIRO, T. R. Turismo Étnico. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Cecierj, 2018. p. 23-39. [ Links ]

SOARES, J. G. S.; LÖWEN SAHR, C. L. Ação coletiva, cooperativismo e turismo: estudo de caso da comunidade Menonita de Witmarsum (Paraná/Brasil). Pasos: Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, El Sauzal, v. 14, p. 111-125, 2016a. [ Links ]

SOARES, J. G. S.; LÖWEN SAHR, C. L. Turismo Cooperativo: discussão conceitual e análise qualitativa da cooperativa inter-étnica Cooptur - Cooperativa Paranaense de Turismo. TURyDES: Turismo y desarollo local sostenible, Málaga, v. 20, p. 1-8, 2016b. [ Links ]

Received: January 11, 2021; Accepted: June 04, 2021

texto en

texto en