Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 10-Jul-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469825665

ARTICLE

INTERCULTURAL METAMORPHOSES: THE IMPACT OF IMMIGRATION ON THE MENTAL HEALTH OF LATIN AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IMMIGRANTS1

1Doctoral student in the Postgraduate Program in Psychology at the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), also works as a Psychologist at the Pro-Rectorate of Student Affairs at the Universidade Federal da Integração Latino-Americana (UNILA). Foz do Iguaçu, PR, Brazil. <alisson.ferreira@unila.edu.br>

2Full Professor at the École de travail social et de criminologie, Université Laval. Québec, Canada, and Professor of the Postgraduate Program in Psychology at UFSC. Florianópolis, SC, Brazil.

In contemporary educational scenario, marked by globalization and the valuing of academic education, immigrants leave their place of origin seeking better educational opportunities. When moving from their home countries, these immigrants will have to deal with the distance from the cultural and social references that guided their daily life and with the cultural and educational difference of the new context, which in turn, can generate a state of psychic vulnerability and suffering. Faced with this problem, this research aimed to understand the impacts of international migration on the mental health of undergraduate students at the Federal University of Latin American Integration (UNILA). To this end, we sought to identify the pre and post-migratory risk factors for students' mental health, post-migration psychological symptoms, and pre- and post-migratory protective factors. We conducted a qualitative investigation, with a descriptive, exploratory, and transversal character. For data collection, we used an intercultural sociodemographic form and semi-structured interviews. We systematized the results using the content analysis technique. Participants pointed out the difficulties they found, but immigration/academic mobility was also seen as the possibility to continue a life project.

Keywords: academic mobility; mental health; university education; latin american

No cenário educacional contemporâneo, marcado pela globalização e valorização da formação acadêmica, imigrantes saem de seus países em busca de melhores oportunidades educacionais. Ao se deslocarem de seus lugares de pertença, estes imigrantes têm que lidar com a distância dos referenciais culturais e sociais que norteavam o seu dia a dia e com a diferença cultural e educacional do novo contexto, o que, por sua vez, pode gerar um estado de vulnerabilidade psíquica e sofrimento. Diante de tal problemática, nosso objetivo nesta pesquisa foi compreender os impactos da migração internacional na saúde mental de estudantes de graduação da Universidade Federal da Integração Latino-Americana (UNILA). Para tal, buscamos identificar quais são os fatores de risco pré e pós-migratórios à saúde mental dos estudantes, os sintomas psíquicos pós-migração e os fatores de proteção pré e pós-migratórios. Seguimos o viés epistemológico da investigação qualitativa, de caráter descritivo, exploratório e transversal. Para coleta de dados, utilizamos formulário sociodemográfico intercultural e entrevista semiestruturada. A sistematização foi realizada via técnica de análise de conteúdo. Dificuldades foram encontradas pelos participantes, mas a imigração/mobilidade acadêmica também se mostrou como possibilidade de continuidade de um projeto de vida.

Palavras-chave: mobilidade acadêmica; saúde mental; ensino superior; latino-americanos

En el escenario educativo contemporáneo, marcado por la globalización y la valorización de la formación académica, los inmigrantes salen de sus países en busca de mejores oportunidades educativas. Al trasladarse de sus lugares de pertenencia, estos inmigrantes tienen que lidiar con la distancia de los referentes culturales y sociales que guiaron su vida cotidiana y con la diferencia cultural y educativa del nuevo contexto, lo que, a su vez, puede generar un estado de vulnerabilidad psíquica y sufrimiento. Ante esta problemática, nuestro objetivo en esta investigación fue comprender los impactos de la migración internacional en la salud mental de los estudiantes de pregrado de la Universidad Federal de la Integración Latinoamericana (UNILA). Para ello, se buscó identificar los factores de riesgo pre y post-migratorios para la salud mental de los estudiantes, los síntomas psicológicos post-migratorios y los factores de protección pre y post-migratorios. Seguimos el sesgo epistemológico de la investigación cualitativa, con carácter descriptivo, exploratorio y transversal. Para la recolección de datos, se utilizó un formulario sociodemográfico intercultural y una entrevista semiestructurada. La sistematización se realizó mediante la técnica de análisis de contenido. Los participantes encontraron dificultades, pero la inmigración/movilidad académica también se mostró como una posibilidad para la continuidad de un proyecto de vida.

Palabras clave: movilidad académica; salud mental; educación superior; latinoamericanos

INTRODUCTION

When someone leaves beyond the boundaries of the customs and beliefs that demarcate their physical and cultural territory of belonging, they take with them the intensity of the strength of what makes them human. By entering the field of symbolic exchanges in which the self and the other (the last stranger, a priori) find themselves in conditions of sharing the same spaces, there are multiple possibilities of relationship between them. However, a premise is, since now, guiding: neither the habitual resident, nor the international migrant will be the same (Silva-Ferreira, 2019).

For the immigrant, the "suitcase" is configured as a metaphor of his identity. He keeps in it his subjective baggage, built through his culture, experiences, dreams, hopes, fears, and nostalgia. By incorporating of one more "piece" in each new arrivals and by the temporary or permanent farewell of things, places and people that were part of him in each place of departure, the immigrant makes and remakes himself. In his "suitcase" he keeps his cultural heritage, his project of existence, which he takes with him in each arrival and in each departure. From this perspective, migrate means to "re-signify" the set of relations of support and helplessness provided by culture (Pieroni, Fermino & Caliman, 2014).

However, immigration is not only part of an individual and subjective displacement, and it is a phenomenon interrelated with social structures and with the conditions of existence and quality of life. In voluntary migrations, social determinants such as unemployment, low quality of life and the lack of a horizon of opportunities (among them, the educational ones) have an influence on the decision to migrate. As for involuntary migrations, the subject has his existence threatened by wars, famines, political, religious, gender persecutions, etc., and so he leaves with little or no planning to places where he can feel safer (Martins-Borges, 2017).

In the face of this subjective and social displacement, the immigrant is bound to experience cultural helplessness and unease and may also experience a condition of existential indeterminacy, meant by the feeling of not belonging, which is linked to expressions of suffering (Dunker, 2015). This interrelation occurs in the social sphere, in a dialectic of exclusion and inclusion, connected by historicity - for example, colonial and slavocrat heritage -, by social organisation and how it influences the relationships between people (Sawaia, 2001). Thus, this unrest also represents a suffering based on a deficit of social and political recognition resulting from the human need to be recognized in our identity and our value as human beings. Therefore, we must reflect on the social and, in this case, educational borders that hinder or prevent the development of human potential or the survival of groups and nations, imposed both within the countries of origin and in the country of reception (Sawaia, 2001).

Therefore, it is in the set of meanings of a "belonging to a place" that the immigration scenario requires elaboration by the migrant subject. "Where am I?", "why am I here?", "am I part of this place?" are some of the existential questions of the migrant that refer to a demand for "recognition", of a search for a place where he feels recognised and in which he recognises himself integrated. By conjecturing, we evidence that the immigrant's subjective experience of powerlessness refers to a non-place, that is, a subject divided between two apparently antagonistic worlds. "I am in a place, and I am not in a place", "I am, and I am not", are part of the psychic conflict reissued by immigration.

It is important to consider that, to analyse immigration as a risk factor for mental health, it is necessary to understand it as a multifaceted and multi-determined phenomenon, and that, in accordance with its social, political and subjective dynamics, it may present itself in a more accentuated way as a risk factor, enhancing vulnerability, or even as protection and building a resilient position (Girardi, 2015). Among the symptoms observed in people who immigrated are the psychological states of depersonalisation, deep sadness, anhedonia, social isolation, conflicts in the relationship with the local people, anxiety, uncertainties regarding the existential project, and psychosomatic complaints that represent the possibility of bodily expression of anguish (Martins-Borges, 2013).

IMMIGRATION AND HIGHER EDUCATION

Regarding education, there are some immigrants who aim to enter university institutions to enhance their educational skills. Indeed, there is a portion of these who plan to enter university since their departure, i.e., they already leave their countries with the purpose of achieving greater educational development. However, there are also those who initially did not plan to enter higher education. After a period of residence in the country of destination, however, they see in the university degree the possibility of reconfiguring their existential project (Silva-Ferreira, 2019).

We can identify some profiles of university immigrants in accordance with the motivation of immigration and social class: a) immigrants that move autonomously, in other words, students who use their own financial resources to finance their studies abroad and are part of an economic and educational elite; b) immigrants that are awarded academic incentives, such as scholarships, and they migrate within the logic of educational cooperation between countries and institutions - in this case, it is common the existence of meritocratic (performance) and/or social/financial criteria that combat educational inequalities; c) those people who migrate for reasons of economic vulnerability and restart their educational life project; and, finally, d) people in forced immigration conditions (refugees or humanitarian immigrants), who leave their countries of origin and find in the access to the university an opportunity to restart (Zamberlam et al. , 2009).

Despite the multifaceted characteristics, immigration is the common denominator of the phenomenon. Given this and the existing nomenclatures, we opted for this research the one that highlights immigration in its intersection with the academic area, which is the denomination of university immigrant. From this perspective, we can define that university immigrants are those who perceive in immigration the possibility of professional and personal qualification for the realization or reconfiguration of a life project, and who generally complete undergraduate or graduate courses at the same institution, remaining for years in the country of destination (International Organization for Migration [IOM], 2019). Therefore, this category does not include exchange students who, despite the similarities, are differentiated, among other aspects, by the length of stay in the university and country of reception and by the concrete perspective of return. As it is a life project that is intersected by migration, it is pertinent to observe the motivations to enter a foreign university considering the variables of a cultural interaction process mediated by the difference, such as the language, the socioeconomic conditions, the customs, the values, the different educational systems, the racial, ethnic and gender prejudice, etc.

Regarding university immigrants in Brazil, according to data from the Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais, INEP4 (2020), in 2019, the country had 17,539 university immigrants in undergraduate education, with 49% coming from the American Continent, mainly from South America. One of the empowering factors of this scenario of internationalisation of the Higher Education was the Program for the Support and Restructuring of Teaching at Federal Universities (REUNI) of the Lula Government, which, in the face of a new geopolitical paradigm of the Brazilian State, built at the beginning of the last millennium from South-South cooperation relations, created the Universidade Federal da Integração Latino-Americana (UNILA) (UNILA), aimed at the integration of students from the entire Latin America and Caribbean region, and the Universidade Federal da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira (UNILAB) , aimed at the integration of students from African countries whose official language is Portuguese. These are configured respectively as the two Brazilian higher education institutions with the most significant number of university immigrants (Silva-Ferreira, 2019).

Besides these institutions, there are other programs to integrate university immigrants into the Brazilian Public Higher Education system, one of which is the Undergraduate Student-Covenant Program (PEC-G), which offers higher education opportunities to people from developing countries which Brazil has educational and cultural agreements. There are also the affirmative action programs for refugees and/or immigrants for humanitarian reception, encouraged by the Sérgio Vieira de Mello Chair5 of the United Nations High Commission (Silva-Ferreira, 2019; Sérgio Vieira de Mello Chair [CSVM], 2020).

Regarding UNILA, in 2019, it had 5,231 undergraduate students, distributed in 29 courses. Of the undergraduate students, 1,316 were immigrants from 19 countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, and countries in Europe, the Middle East, Asia and Africa (Silva-Ferreira, 2019). In addition to the international selection process held annually, in 2018, UNILA launched two new forms of entry: one aimed at people in refugee conditions or holders of humanitarian visas, and the other for indigenous people whose communities are in Brazil and in nine other South American countries (Universidade Federal da Integração Latino-Americana [UNILA], 2020).

Because of its political-institutional direction to promote cultural, academic, and scientific integration of the Latin American peoples, and its geographical position in the triple border Brazil-Paraguay-Argentina, UNILA was chosen as research context. Its international vocation and its integrationist and bilingual project (Portuguese and Spanish) resulted in a unique environment for the implementation of this study.

We also highlight the scant research on university immigrants in Brazil. According to the literature review conducted by Silva-Ferreira, Martins-Borges and Willecke (2019), only 11 articles were found between 2007 and 2016 in the BVS-Psi, Redalyc and EBSCO databases. In this regard and given the above, our proposal in the present study is to understand the impacts of immigration on the mental health of university immigrants. To this end, we will present the main pre- and post-migration risk factors, the psychic symptoms after immigration and the pre- and post-migration protective factors.

METHODS

For this qualitative, descriptive, and exploratory research, we used a cross-cultural sociodemographic form and a semi-structured script for the interviews. We followed the standards of resolution 510/16 of Conselho Nacional de Saúde (The Brazilian National Health Council), which deals with ethical principles in research in Human and Social Sciences, and the project was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with Human Beings of the Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC). We also provided participants with the Terms of Free and Informed Consent with versions in Portuguese, Spanish and Haitian Creole.

By following the principles of qualitative research, this study was characterised for being constructive-interpretive, dialogic, and attention to the participants' unique experiences. Thus, as in constructive-interpretive production, we needed to interpret and understand the meaning and significance of the participants' expressions; it was also essential that we maintained a dialogical posture, since the interaction with the participant had fundamental relevance in the process, and it was also a sine qua non condition that we valued the theoretical construction of subjective processes at both the social and subjective levels (Rey, 1999).

The participation criteria were: 1) to be a UNILA undergraduate student; 2) to be a member of a student aid program and/or international agreement that has as a parameter the socioeconomic condition for the acquisition of financial aid; 3) to have good comprehension and oral expression of the Portuguese language; 4) to be 18 years old or older; and 5) not having any personal relationships with the researchers.

For the choice of participants, we used the "Snowball" technique, a non-probabilistic method that consists of the nomination of potential participants by the key informants, by documents, and/or by the interviewees themselves (Vinuto, 2014). The first key informants were the psychologists of the Psychology Section of UNILA; these requested the authorization of the potential participant to provide their contact email and/or phone number. The previous contact with the group of Haitians was mediated by an intern of this nationality, who worked at the Prorectorate Office of International and Institutional Relations.

Not all contacted immigrants became participants. Of the 28 contacted, ten were unable to participate. The reasons were: difficulty in getting free time for the interview, absence on the day of the interview and withdrawal; one participant was excluded because he had a severe mental health crisis days before, and, due to psychological risks, we opted for his non-participation.

Thus, between March and April 2018, 18 university immigrants (identified in the present text by the letter P, followed by a number), from seven Latin American nationalities (Colombia, Haiti, Venezuela, Uruguay, Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia), participated in the research. This number of participants resulted from the conclusion that the interviews provided repetition of content and, consequently, there was consistent material to meet the research objectives (Minayo, 2017). Interviews with participants from Spanish American countries were conducted in Spanish, translated into Portuguese and submitted to peer review. Interviews with Haitian Creole speakers were conducted in Portuguese. All interviews were individual and recorded (voice) with prior authorization from the participant.

For content transcription and coding, we used Manzini's (2008) guidelines as reference. The parts with noises that made it impossible to understand the word were enclosed in parentheses and signalled with the word "inaudible"; the silences longer than five seconds were identified by the expression of the number of seconds, for example, (6s); the emotions, such as laughter or tears, were highlighted between two parentheses, for example, (( laughs)); the ellipsis between parentheses (...) symbolize cuts in the discourse due to the need for synthesis and/or complementation of the content; and, finally, additional questions or verbalizations of understanding on the part of the researcher were enclosed in brackets [ ].

After each interview, we applied the sociodemographic form of the Núcleo de Estudos sobre Psicologia, Migrações e Culturas (NEMPsiC). This form was constructed by NEMPsiC6 and used help to understand the migratory and sociocultural specificities of the research participants. The form consists of 47 questions divided into eight categories. These are: personal data, education and occupation, income, residence, use of the SUS (Brazilian Public Health System) and/or religion/belief(s), social network, language, and immigration data. The interview script, in turn, was composed of questions involving the pre-migration stage, departure, post-migration, inclusion in the university, local integration, health and future projects, so that participants could freely express themselves about these experiences.

Finally, the interviews were submitted to the content analysis technique (Campos, 2004). The categories were built as directed by the interview script, guided by the research objectives. As per Campos (2004), the categories may be characterised as significant statements encompassing a variable number of themes. From this set of themes, we extracted the subcategories and the thematic units built according to their degree of intimacy or semantic proximity, so that, as a result of their analysis, they could reveal relevant meanings and elaborations to meet the research objectives. The subcategories and thematic units were created based on the similarities between the participants' speeches and the contents of implicit relevance (Campos, 2004). From these descriptions, it was possible to identify (or not) similarities with the results of other studies, as well as analyse the narratives based on data from the sociodemographic questionnaire and from the perspective of psychoanalysis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

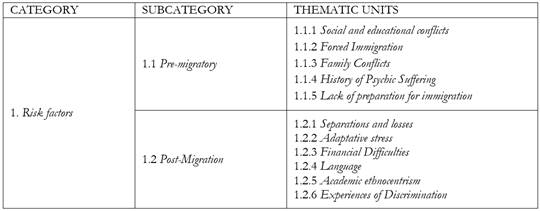

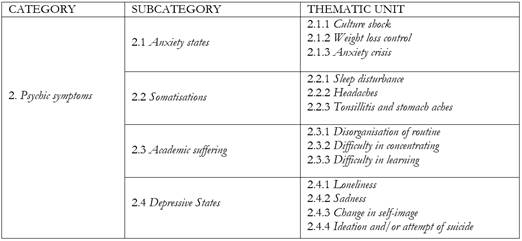

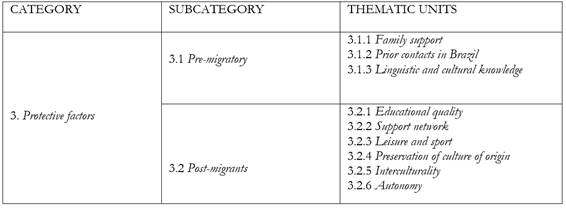

Based on the research objectives, we identified three categories: Risk factors, Psychic symptoms, and Protective factors. Therefore, each category was composed of subcategories and thematic units, which are detailed in their respective tables.

The first category, Risk factors, is composed by two subcategories. The first, Pre-migratory, concerns the factors prior to immigration. However, it is important to consider, especially in relation to the construction of the first two thematic units, that there are different educational and social/humanitarian realities between the countries of origin of the participants. The Post-Migration subcategory represents the risk factors encountered after arrival in Brazil. These two categories are composed, respectively, by five and six thematic units, which represent the main factors that negatively influenced the mental health of the university immigrants in this research.

In the first subcategory of risk factors, we analysed, in the participants' narrative, the social and subjective elements prior to immigration that potentially exerted force on the destabilisation of psychic balance. In the thematic unit Social and educational conflicts, we identified how pre-migration social conflicts point to a complexity of factors around the immigration of university students in Latin America, as well as feelings of social malaise and educational exclusion preceding and motivating the migration process. The speeches also exposed an unequal and excluding Latin American educational situation, in which the impacts of the process of mercantilisation of public education and the consequent social exclusion potentiated by the latter also stand out (Perrotta, 2015; Zamberlam et al., 2009).

The strong educational barriers in the countries of origin were also observed in Girardi's (2015) with Haitian participants who immigrated after the 2010 earthquake. It is important to remember that this event destroyed much of the capital Port-au-Prince and aggravated the humanitarian crisis in Haiti and, consequently, the educational possibilities. In addition to the educational dimension, we must also consider the risks inherent to social starvation and the inefficiency of the state in that country:

“Education for children you have to pay for all the studies (...) So, you have to pay for everything, since the first year of school, until the end, until you can get a job. And sometimes you have to pay to get a job, pay in some way, do you understand? Money and stuff. And the basic sanitation, the street cleaning is very, very, very bad (...) And these things, politics... Hunger, a lot of hunger, there's a lot of hunger!” (P15, Haitian female).

Another scenario that was repeated in the students' speeches was that of the Colombian reality and its process of educational exclusion. This, strongly influenced by the liberal and economics dictates of education, resulted, for example, in the existence of public, but not free, Higher Education. As a result of this mercantilisation of education, a process of exclusion of the most economically vulnerable groups was established, which either prevented access to Higher Education or caused debts to the students and their families. This context of exclusion became one of the agendas of the Colombian youth involving the social revolt of 2021 (Oliveira, 2021).

However, forced immigration emerges as a risk factor that characterises a background of violence. This thematic unit also diverges from the previous one due to the lack of preparation for immigration, in addition to the reduced possibility of return due to conflicts that endanger the lives of immigrants (Martins-Borges, 2013). In these migrations, specifically narrated by Haitian and Venezuelan students, the possibilities of choice represented by questions - where to go, how to go and with whom to go - are diminished due to the urgency of displacement:

“I am from Venezuela, and you know the situation in Venezuela...I did not come of my volition, they dragged me here (...) Then after months, about four months I found myself desperate and I saw that I had to leave the country because I already had days without any food, the situation was getting worse and I have a little brother, I felt impotent because I wanted to work and there was no work, the money was not enough.” (P14, Venezuelan female).

As exemplified in the narrative, in these cases the absence of a previous migratory project commonly occurs. This type of migration happens due to the risks of permanence, and is accompanied by feelings of despair, humiliation/persecution, and hopelessness, which encourage the subject to abruptly move away from their places of belonging and seek opportunities for a new beginning. (Martins-Borges, 2013).

As for the third thematic unit, Family conflicts, we analysed the risk factors that involve the relationships in the family environment. From the contents presented, we highlight the conflict in the dependency-independence relationship between parents and children, the feeling of guilt, the perception of family control and the weakening of affective bonds. We remember that university immigration to attend undergraduate studies is mostly composed by young people, who are in a transition phase from the adolescent identity, more family tutored, to the adult identity and its prerogatives of autonomy and responsibilities. In this sense, immigration may also be motivated by a chance to escape the family conflicts, which indicates the absence of a protective factor, which tends to impact on post-migration psychic stability: “I felt like a burden to my mother. And I came because here I could live alone, support myself...I was being a burden to my mother.” (P2, Colombian female).

Such conflicts were also found in the research of Francisco (2019) with Haitian university girls in Belo Horizonte (MG). The author states that the participants' migration was surrounded by fear, ambivalence, negotiations and clashes with their families. In the case of our study, this conflict presented itself in both men and women, which does not exclude the cultural gender differences in the student migration process.

In the fourth thematic unit - History of Psychological Suffering -, we observed the frequency with which immigrants reported symptoms prior to the process of immigration, which were updated in the post-migration period. In this sense, we corroborate the studies of Moro (2015) and Woodward (2010), which indicate that situations of immigration stress tend to " reupdate" previous psychic conflicts due to the weakening of psychic and social defences:

“It was not a bad decision, but I recognize that I found things more difficult than they were before, there I suffered from the depression and I was bad, but at this moment it is much more difficult because I am in another country with a new language and with people who only think about university, and I could have already finished my course in Colombia because I am 22 years old.” (P1, Columbian female).

The participant's narrative shows that she was already experiencing psychological suffering before coming to Brazil, which was aggravated by the linguistic challenges and the difficulty in building bonds. In Woodward's (2010) research with university immigrants in England, he also identified that, even in the face of the fact that the university course abroad means the desire for development and overcoming feelings of guilt and past suffering, the stressors arising from migratory displacement and adaptation to the foreign academic institution implied the need to elaborate traumatic experiences from the past.

As the last thematic unit of the pre-migration risk factors, the Lack of preparation for immigration emerged. Immigrants often reported having little information about Brazil, Foz do Iguaçu and about the university, or even partial and stereotyped representations about the Brazilian culture. As we will see in the following categories, the deficiency in preparation for immigration can enhance the emergence of an acculturative stress process. Thus, the study corroborates that the absence of realistic information about the environments where they projected to study and live, the idealisation of the contexts and the potential unpreparedness for immigration constitute intensifiers of culture shock, as identified in the work of Silva-Ferreira, Martins-Borges, and Willecke (2019), which highlights that this is the most bypassable risk factor, especially among voluntary immigrants: “About Brazil, nothing. I didn't even imagine that Portuguese existed. Nothing, nothing... And about UNILA, I only knew what was written on the website, but I didn't understand much.” (P2, Columbian female).

Following the analysis, we sought to identify the post-migration factors. The main factors found were: the dynamics of separations and losses, adaptive stress, financial difficulty, language difficulty, academic ethnocentrism and discrimination experiences.

The first thematic unit, Separations and losses, refers to a characteristic dynamic of the migratory process which refers to psychic conflicts expressed by the feeling of lack. With the emergence of this lack (real and/or symbolic), the immigrant is faced with a sense of loss and imaginary incompleteness due to the distance from the elements of meaning that were part of everyday life and organised the relationships with reality (Betts, 2005; Moro, 2015). Specifically, the main separations and losses upon arrival at the new context were related to family and friends, food, landscapes and cultural events. Such losses recurrently exalted the nostalgia and idealization of the lost object: “((Laughs)) That was the hardest thing in the world! It is difficult. (...) There were two moments of separation: separating myself from my family and separating myself from my place, how would you say? From what... from my social bond”. (P6, Colombian male).

We can observe that the process of separation and loss of the affective elements that composed the immigrants' "daily life" led them to a mourning process due to the feeling of loss. Such losses trigger feelings of nostalgia, that is, a desire to return to the previous condition and also an exaltation of the "lost object". Other narratives also highlighted the symbolism of the absence of their typical foods. In this sense, eating is associated with affective memories of nutrition, affection and intimacy with people and places; and to distance oneself from this cultural daily life is to distance oneself not only from people, but often from one's own identity.

On this connection with the daily cultural symbols, we realize that culture and its signifiers exercise a maternal function, i.e., a function of psychic support to the subject, and that the separation caused by immigration can refer to a feeling of emptiness (Martins-Borges, Jibrin & Barros, 2015). Another example of the feeling of "loss of place" refers to the nostalgia in relation to landscapes of everyday life. As these memories of places are formed by affective experiences that involve the feeling of belonging, it is common that the immigrant develops an "attachment to the place" and starts to value the "lost place". However, with immigration, the immigrant will have to elaborate this lost and often idealized daily life, along with all the nuclei of meanings that composed it.

The losses related to social attachments, such as birthdays, family reunions and moments of greater instability in the native land, evoke feelings of impotence, concern, and frustration. Such moments in which the university immigrant wishes to be present, but cannot, require him/her to develop his/her own distance that makes him/her experience the impossibility of not being in two places at the same time, which exposes him/her to ambivalence.

Thus, the thematic unit Adaptive stress is closely related to the previous thematic unit, since the former deals symbolically with a "lost world" and the latter, with an "unknown world". Thus, this unit delineated the stressors that were intrinsic to the social context of arrival, which hindered the adaptation of university immigrants. The main adaptive stressors were climate impact, interpersonal relationships, institutional failures of reception, absence of cultural activities in the city, inefficient public transportation and the precariousness of the Brazilian Unified Health System (called with the acronym SUS).

In turn, the speech of P12 represents the theme brought by five participants regarding the institutional absence, especially upon arrival and reception, also emphasizing the importance of institutional care, as highlighted by other researchers (Prieto-Welch, 2016; Saladino & Martinez, 2015).

“I observed a lot of institutional absence. How you are bringing from another country, it's I don't know (...), about 500 foreigners per semester around 17 and 18 years old, and the first official welcome meeting with the university took months and many things took a long time to learn because the university did not introduce itself.” (P12, Uruguayan female).

The highlighted adaptive stressors corroborate what has already been observed: when the immigrant is faced with a distinct society, he/she must learn new logics and meanings that are part of the adaptation process in the new culture (Birol, 2017). However, in addition to an intrinsic stress to the learning process that the unknown environment demands, it is imperative to think that this is part of a set of individual, institutional and social/cultural factors that can hinder the learning and adaptation of the university immigrant to the new context (Barea, 2008).

The thematic unit Financial difficulty showed how much this issue influences the lives of university immigrants. Of the 18 participants, 12 lived only with the financial aid from the university - equivalent to two thirds of the minimum wage; 5 with aid and the help of family members; and only one with the help of family members. In the narratives, the students showed difficulties regarding the basic needs to live and study, such as food, housing, internet and contact with the family, which reverberated negatively in various aspects of their lives - including mental health: "And so when I arrived I went to the hotel and had no money to eat, I knew I was going to make a sacrifice to follow the course, but it's still a sacrifice I'm making, understand?” (P18, Haitian male).

The thematic unit Language represents the most cited difficulty highlighted by students on arrival in Brazil and/or at university (17 out of 18 participants). In the academic field, learning complex content in a language whose mastery has not yet been achieved requires effort on the part of immigrants. However, the effort is also noticeable on the part of those who teach, given the complexity of teaching in classrooms with culturally and linguistically heterogeneous groups. We remember that, besides a bilingual project, the university has the challenge of dealing with the multilingualism due to the presence of students with different mother tongue: Guarani, Quechua, Aymara, Haitian Creole, French, Arabic, Russian, etc. This complexity entails challenges and obstacles for students, teachers, and administrative staff and, consequently, for the language policy of the university:

“(...) it is not easy to take calculus classes in portuguese, that is, you are not only facing the challenge of learning calculus, but also the challenge of learning in portuguese, where letters are pronounced differently and teachers' accents change the meanings (...)” (P12, Uruguayan female).

As shown above, the language is one of the main elements of a culture and holds symbolisms, ways of expressing meaning and models of interaction between people (Nathan, 1994). Regarding this difficulty and its effects, the study corroborates the risk of sociocultural isolation with the fellow countrymen, which can cause damage in sociability and adaptation to the new culture. As for learning, we observed that, not having mastered the language of study yet, university students need more time or additional techniques to comprehend the content. When they do not have this understanding, they limit the expression of thought in assessments and in class participation. We also found in some cases that this limitation led to academic isolation and resulted in a higher risk of failure and dropout.

In turn, the thematic unit Academic Ethnocentrism revealed conflicts around cultural differences and power relations that resulted in symbolic violence, especially in the classroom. Academic ethnocentrism, according to Marginson (2014), consists of an intense valorisation of the epistemological elements of the host institution and a denial/indifference to the training contents of the university immigrant. Such positioning, veiled or explicit, ends up producing a true "epistemicide" (Santos, 2007), which would consist in the inferiorization and "homicide" of the knowledge of the other. As Carvalho (2018) states, multilingual coexistence requires the development of awareness of the other's culture and the need to value this culture to promote integrative teaching and learning practices: “My classes are all in Portuguese, I only read in Portuguese, my teachers never gave me texts in Spanish and that sometimes tires me a lot.” (P12, Uruguayan female).

The narratives also indicated the feeling of preference towards Brazilians, repression in the use of the mother tongue and ethnocentric preference in the choice of bibliography. Such observations may symbolise the valorisation of one culture, but may also represent a certain cultural-educational comfort zone incompatible with an intercultural pedagogy. A closer look at the narratives allowed us to identify that this academic ethnocentrism also pervaded the relations between the students themselves and was influenced by social representations and prejudices about nationalities and ethnicities, since the main complaints of isolation and stigmatisation in the classroom were from black and indigenous students.

Closely related to the previous one, the thematic unit Experiences of discrimination brings how a set of prejudices of race, nationality, social class, gender, and political-institutional identity resulted in violence faced after immigration. We also observe that these discriminations were described both inside and outside the university.

As a first point of discrimination, we identified racism faced mainly by black students and students of indigenous phenotype. Regarding the black students from Haiti, it is possible to observe that racism was not experienced in Haitian culture, which led them to a "strangeness" when experiencing this issue in Brazil. On the other hand, we return to reflections on how the historical ghost of slavery remains in the bowels of Brazilian society, and how racial democracy still remains a myth:

“But last week someone passed in front of us when we were going to class and said a lot of nonsense: 'Go back to your countries!' 'UNILA brings these Haitians...' said a lot of things, and this affects our mental health, affects our mind. But what can you do? (...) Sometimes it makes you sad, because you left your country for something that you don't have there, and you are taking advantage to conquer in another place that is not yours, that is not your country as the person said.” (P17, Haitian male).

The narratives also show the racialization of the city spaces and feelings of powerlessness in the face of a feeling of "not being welcome", which inhibits the subject in their daily interactions and impacts on their self-esteem. According to Fanon (1980), racism has an inferiorizing function that oppresses the black not only emotionally, but also intellectually, which in turn highlights the colonial heritage and the discourses historically reproduced about the black and the Indian in Brazilian culture. Also as observed by other researchers, racism is one of the main forms of discrimination against the university immigrant who does not meet an ideal standard of "whiteness". (Silva & Morais, 2012; Francisco, 2019).

We also observe the impact of xenophobia on immigrants' mental health and sense of belonging. The veiled or explicit xenophobic aggressions promote a sense of "non-place" in the immigrant, creating obstacles to identification and attachment to the new culture (Bauman, 2017; Sayad, 1998). In this sense, violence makes the immigrant, to protect himself, live in a more segregated way. Another point observed in the interviews is the state of constant surveillance, which leads the immigrant to repress expressions that "denounce" their "foreign status", such as speaking their language, wearing typical clothing or walking in the street.

Another theme of discrimination highlighted by the students concerns UNILA's political-institutional identity. The intensification of political conflicts in Brazil around the dichotomy "right-wing party e left-wing party", "good" and "bad", and especially the emergence of a nationalist and conservative wave, as the students see it, have increased the experiences of hostility outside the university walls.

The various facets of discrimination experiences seem to demonstrate a conflict over the imaginary possession of the territory and the possible goods present there. These conflicts with difference, aligned to historical, cultural, and sociopolitical traits, feed a narcissistic dynamic of the small differences (Freud, 2006/1921).

Thus, we can consider, from the previous narratives, the intrinsic relationship between mental health and social determinants such as race, ethnicity, social class, gender, and nationality, which imply the emergence of ethical-political suffering involving the social dyad inclusion-exclusion (Sawaia, 2001). In turn, these determinants, linked to the migratory dimension and its flows, challenge the institutional and national permanence policies guided by the Plano Nacional de Assistência Estudantil (National Student Assistance Plan - PNAES) to create programs that meet the specificities of the demands and the challenges of the permanence of university immigrants, as highlighted in the research of Ragnini et al. (2021), Silva-Ferreira e Zdradk (2020).

As observed in the category Risk factors, the migratory process is composed of a set of pre- and post-migratory elements that potentially impact on mental health and cause psychological suffering. Based on this understanding, the second category - Psychic symptoms - represents the main symptoms observed and reported by university immigrants after arriving in Brazil and at the university.

The first subcategory, Anxious states, is composed of three thematic units: culture shock, weight loss and anxiety crisis. However, it is important to highlight that anxiety is considered a normal state that has the function of allocation of psychic energy and concomitant preparation of the subject for new experiences that lead to expectations and/or fear. However, among the various forms of manifestation of anxiety, there are those that cause intense unpleasantness, hinder adaptation, cause social harm and/or psychological suffering (Freud, 2006/1925).

The first thematic unit, Culture shock, brings a phenomenon that participants described occurring after arrival and in the first interaction experiences. As the metaphor itself indicates, a "shock" is caused by the encounter with cultural difference and the unknown (Birol, 2017). Thus, we observe that, like anxious states, this shock can be subtle, acute or with long-lasting effects, and represents a dynamic between the psychic world and the new cultural environment:

“Then I was at home, for example, and we spoke Spanish and when I went out into the street it was a shock, because you leave and don't know that you have to change. So when the person speaks, you think "ah, now you have to speak Portuguese". Until now it has been a shock, until now sometimes I wake up and I can't speak well, but it is like a mental block like that. It's not that I don't know, it's that sometimes I can't speak.” (P14, Venezuelan female).

The second thematic unit, Weight uncontrol, refers to the anxiety that, according to immigrants, causes a change in the way they eat. Such factors as the change in routine, the absence of exercises, the difference in the foods found in Brazil and the psychological suffering influence this process. Freud (2006/1925) argued that the tension in the psychological system has repercussions on anxiety, and makes the ego seek known alternatives of satisfaction to deal with the unpleasantness and tension when facing the unknown. In this sense, the oral satisfaction provided by feeding reveals itself as a palliative to the discomfort caused by anxiety after immigration: “And my anxiety about eating has been getting worse. And that, my routine is this, sitting down every day and like consciously I want to do things, but unconsciously I'm surrendered (...)” (P2, Colombian female).

The third thematic unit, Anxiety crisis, was highlighted by university immigrants in moments of helplessness and greater intensity of anxious symptoms. This helplessness may be associated with the loss of perspective and also with the uncertainty when facing the adaptive stress in the new context. Represented by the anxiety crisis, helplessness may signify a weakening of active defenses before immigration, and that accompanies the need for understanding about this mental state never experienced before:

“In mental health, my anxiety got worse. A month ago I sought a psychologist because I had an anxiety attack here, and it was very strong, things happened... it started attacking overnight, and I felt that I was not mentally well... in Colombia I never had this, or I repressed it, because I had to be strong for my family, do you know?!” (P7, Colombian male).

We observed that anxious states manifested themselves in different ways and in different circumstances, but generally in relation to the internal or external unknown. Thus, they may represent an expression of the post-migration psychic conflict around the loss of familiarity and "control" over reality (Betts, 2005; Pocreau, 2018).

The subcategory Somatizations represents the symptoms that had the function of expressing, through the body, the conflicts and the psychic suffering experienced by university immigrants after immigration. The first symptom highlighted was Sleep Alteration, followed by Headaches and Tonsillitis and Stomach Aches. Participants expressed that these symptoms started or intensified after immigration. Moreover, they related them to the climate adaptation, the acculturative stress, and the sensation of strangeness. According to the participants, there was a higher prevalence of these symptoms in the first year in Brazil: “Yes, it has changed. Now I am always sick. There I never had any diseases, those diseases.” (P15, Haitian female).

Another important issue to be considered is that the forms of symptomatic expression are also subordinated to the immigrants' cultural codes. Regarding the hypothesis that somatizations are common forms of expression of immigrants' suffering, we highlight the considerations of Girardi and Martins-Borges (2017) that it is not only the lack of contact with the mother tongue that potentiates somatization, but also the logic of cultural significances that is impaired by the distance from the homeland.

The third subcategory, Academic suffering, refers to the impact of immigration on the educational process. It is important to remember that the academic environment is composed of adaptation challenges and holds within itself forms of expression of unease specific to its context. The first thematic unit, Disorganization of the routine, was highlighted by immigrants as one of the issues experienced when entering university - which is understandable when considering that the student will have to adapt to a new education system, new daily responsibilities, the demand for autonomy and academic performance concomitantly with the sociocultural adaptation:

(...) I felt very disorientated, it's like I couldn't find myself, it's like I was lost, you don't know how to do things, so it was like coming home and being alone again, and having to be a responsible adult ((laughs)).” (P1, Colombian female).

The second thematic unit, Difficulty in concentrating, represents another symptom within the academic environment, which may have different origins and intensities. One of these origins concerns the impact of linguistic differences on the teaching-learning relationship and the cognitive effort to learn a content without the mastery of the language. Such difficulty can generate cognitive fatigue and disinterest in the content and classes (Prieto-Welch, 2016). Another aspect that we can highlight this symptom is its close relationship with learning and with the academic self-image of the immigrant: “My concentration was very low, I did not concentrate at all, nothing. (...) Until last year I did not really have this concentration to study, to do anything.” (P13, Bolivian male).

The learning difficulty and academic failure are multifactorial problems that generate suffering and have a direct impact on the immigrant's self-esteem and trajectory within the university environment. Among its effects, we can list the academic isolation, the impossibility of enrolling in new subjects, the risk of losing student aid and scholarships, and the change in academic self-image.

In turn, the subcategory Depressive states encompasses a set of expressions of psychological suffering that differ in intensity, but, in some cases, and as observed in the individual stories, are interrelated. In this sense, the first thematic unit, Loneliness, represents a characteristic feeling of those who moved away from their place of belonging, where they maintained a good part of their social and affective relationships, and had to build new daily relationships (Moro, 2015).

As we highlight below, the feeling and perception of "being foreign", which, in this case, is linked to a feeling of " foreignness", may refer to one of the main existential issues of human beings, which is dealing with loneliness, helplessness and the constituent lack, as Freud (2006/1885) warned us. To cover loneliness, that is, to cover the lack reedited by a condition of post-migration helplessness, refers to an impossible, since there are indications that it is an "in-familiar", a primordial helplessness that cannot totally disappear (Freud, 2019/1919):

“(...) and for me, being a foreigner and being in Foz7, is to face a keyword that is loneliness! Being alone... and loneliness is the greatest fear in life, as for me people in general are very afraid of being alone. And when loneliness came to me I started to disguise loneliness. Disguising 'loneliness' with people, disguising loneliness with parties, disguising loneliness with cigarettes, with beer and go on disguising loneliness. However, there comes a moment when none of this happens... you do all this and you still feel alone.” (P12, Uruguaian female).

The thematic unit Sadness refers not only to this feeling as inherent to the human condition, but also as a helplessness that may be related to the feeling of losing something concrete from the external world. Sadness is indicated as an emotion strange to the subject himself, who, at first, does not understand the origin and the reason for the outbreak of this feeling and the loss of "emotional control", as brought by P16. In this sense, and according to Martins-Borges (2013), deep sadness is recurrently one of the feelings that emerge in immigrants after their displacement: “Sometimes I am crying, but I don't know why. Sometimes I'm crying, but I don't know, I get sad … It happens.” (P16, Haitian male).

The third thematic unit, Change of self-image, addresses narratives in which university immigrants reported the migratory impact on the change of their self-perception. This change can be characterized by a non-recognition, a disorientation, and an existential crisis, which refer to the estrangement with something disturbing of the subject (Freud, 2019/1919). In the university environment, the change in self-image can be understood as a narcissistic wound and devaluation of academic self-image: “(...) Yes, I did not recognise myself, I asked myself, who am I? What am I here for? If there is no one, I am alone, I will be alone all my life, this and a lot of illogical things were going through my head.” (P14, Venezuelan female).

Finally, the last thematic unit, Ideation and/or attempt of suicide, configures a framework of intense psychological suffering in which the university immigrant is taken by feelings of hopelessness, deep sadness, fatigue, loneliness and a despair that makes the search for a relief through death be cogitated, without being able to measure its own consequences. The deep helplessness and the perception of the absence of alternatives to get out of such a condition are elements of those who feel they have no resources to deal with the new existential condition and/or with the facing of psychic suffering in an unknown context:

“E para ser sincero teve um momento onde minha esposa e eu queríamos tirar a nossa vida. Ela me expressou isso, [Ela te disse isso?] Sim, me expressou isso e eu comprei comprimidos e tal, e quis tirar a vida e eu não consegui, ela vomitou, mas eu não pude, eu tentei com uma faca, mas não pude tão pouco...” (P6, Colombiano). And to be honest there was a moment where my wife and I wanted to take our life. She expressed that to me,[ did she tell you that?] Yeah, she expressed that to me and I bought pills and stuff, and I wanted to take my life and I couldn't, she threw up, but I couldn't, I tried with a knife, but I couldn't either

The severe cases involving university immigrants have a complicating factor which is the potential absence of a close caregiver, that is, of social support. Regarding the identified depressive states, we noticed that the central signifier refers to a feeling of post-migration helplessness. Actions may emerge from this helplessness, which, according to Zimerman (2004), constitute forms of behaviour and non-verbal communication that replace anguishes and conflicts which are not symbolised, remembered, verbalised or contained. The migratory impact and helplessness may be so intense that they may generate passages to the act. These, according to Millaud (2009), are reserved for impulsive and violent acts, such as self-injury (suicide attempt) or hetero-injury (homicide), and the main function of these acts, according to Lacan (2005/1963), would be the attempt to heal the anguish, as exemplified in the previous narrative.

The third and final category, Protective factors, is composed of two subcategories and aims to expose the elements that helped university immigrants to reduce the impact of migration. The first, pre-migration, refers to the protective factors prior to immigration and is composed of three thematic units. The post-migration subcategory encompasses the protective factors found or developed after arrival in Brazil and is composed of six thematic units. Thus, the category Protective factors encompasses from the support coming objectively from the other (family, institution, community etc.) to the own resources that each immigrant had and/or developed to deal with adversities.

The first subcategory, Pre-migratory, presents the elements of social and subjective support that had the function of facilitating both the migration process and the arrival and adaptation of immigrants, thus favouring psychic stability. Thus, the first thematic unit, Family support, corresponds to the affective and material support given by the family. Culturally, the family plays a caring and protective role and it is in this environment that the subjects build a good part of their affective memories and their own identity:

“My parents were very happy, happy, very strong, very happy that I was going to study in another country. They advised me a lot: 'If you are going to leave to go to another country, you have to, to be the most original!' (...) they have a lot of confidence in me! This is a responsibility that I have ((laughs))!” (P10, Peruvian male).

This protective factor was also observed by Girardi (2015) in a research with university immigrants at the UFSC8 (Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina). It was observed in this study that there was a strengthening of affective bonds and a greater frequency of contacts. According to Doku and Meekums (2014), this family tie allows for the maintenance of culture and identity in the face of the anguish of separation and the feeling of loss.

The second thematic unit, Prior contacts in Brazil, proved to be a relevant variable, especially at the time of arrival in the new country. This previous social network can be a relative, a close person or a welcoming gesture among fellow countrymen (P8); it can make a potentially impacting experience - due to unfamiliarity with the context - a moment similar to the arrival in their own home, allowing reducing the anxiety of arrival and increasing the feeling of safety. The previous contacts and the emotional safety provided by them seem to be intrinsically linked to the actions of welcome, solidarity and hospitality, which, in these examples, are related to affective ties and identification dynamics (family, fellow countrymen, friendship, church):

“And so it was, when I arrived in Foz, I was welcomed (...) I think it was an initiative of a Colombian professor who was here (...) And he communicated to the students to welcome the new Colombian students of 2015. It was a beautiful gesture! I felt very good, because it was only my mother who welcomed me at the airport when I arrived... I felt at home, a little bit.” (P8, Colombian male).

According to Subuhana (2009), Silva-Ferreira, Martins-Borges and Welleck (2019), the collectives, associations and reception programmes that receive university immigrants, together with the virtual networks built for the reception and integration of newcomers, make it possible to reduce the negative cultural impact and facilitate the construction of a new support network.

The third and last thematic unit of the pre-migratory protection factors, Linguistic and cultural knowledge, refers to immigrants' preparation and/or previous experiences that allowed them to be less vulnerable to the migratory impact and to culture and academic shock. As we have seen throughout the results, language difference has an influence on learning and sociability, as highlighted by Doku and Meekums (2014), Prieto-Welch (2016) and corroborated by the few students who already knew the Portuguese language before migrating to study at university:

“I think this is a difference that I see compared to my other colleagues who arrived from Colombia for the first time, and I see that they have a conflict, a kind of shock. So I think it was important that I had studied Portuguese before.” (P8, Colombian male).

Linguistic and cultural preparation allows greater optimisation of study time, confidence to express oneself and ease to understand institutional logics. In addition to academic issues, this preparation is an important factor in sociability outside the university walls (Silva-Ferreira; Martins-Borges & Welleck, 2019).

Finally, the second subcategory, Post-migratory, brings the factors that stood out as potential maintainers and/or facilitators of the psychic balance of university immigrants after arrival in Brazil and/or university. The first thematic unit, Educational quality, corresponds to the students' perception and satisfaction with the learning experience at university. Through the analysis of the interviews, we observed that the satisfaction with the quality of the education offered cured the "uncertainties" about whether the immigration and/or the decision to leave the labour market to attend university had been right.

Satisfaction with the choice made represents for the university immigrant the psychic comfort of feeling that "he is on the right track". Besides the classic classroom learning, another characteristic highlighted by the students refers to the construction of a plural educational space permeated by interculturality. In the case of UNILA, the encounters with difference also enabled an expansion of knowledge and the way of dealing with otherness:

“You meet a lot of things at UNILA! A lot! Different customs, dialects, different people, and this teaches you something too, many things. (...) I like it a lot because it is not restricted to the academic. You learn by walking in the corridors of UNILA!” (P3, Colombian female).

Looking further into the impact of cultural differences in the educational environment and the uniqueness of the university context, the experiences of welcoming teaching staff deserve to be highlighted as features of educational quality. The way in which the teacher welcomes diversity and plans his/her class for a multicultural class makes all the difference for the immigrant to feel confident to express him/herself and develop in the academic environment. This element also refers to the institution's preparedness to deal with cultural difference (Saladino & Martinez, 2015; Silva-Ferreira, Martins-Borges & Welleck, 2019).

The second thematic unit, Network of support, as the concept suggests, represents the set of relationships and/or services that support the university student in his/her daily life or, occasionally, when he/she feels he/she needs help. The participants' speeches allow us to subdivide the support network between socio-affective and institutional. The first is constituted by an affective bond which differs from relationship to relationship, but which provides emotional and/or material support at opportune moments. The following stood out as representatives of the socio-affective support network: the family, the course veterans, the city dwellers, the support of the beloved partner, and the countrymen:

“(...) the group of veterans gathered to receive us, as solidarity lodgings. And I arrived at the house of some Uruguayans, really very special! They received me and my husband and gave us a dwelling, food, a lot of tranquility (...). The reception was good, it was safe, it was nice, we felt welcome, they embraced us.” (P4, Colombian female).

We observed greater evidence of sociocultural adaptation in immigrants who had managed to establish ties with both fellow countrymen and Brazilians. Since the university immigrant, when leaving his/her country, moves away from a series of bonds that formed his/her support network, the new friendships, and the balance between relationships with fellow countrymen/foreigners and local people are the ideal equation for reducing the impact of risk factors and favouring the integration into the new society (Garcia, 2012; Subuhana, 2009).

The first representatives of the support network of university immigrants are fellow countrymen or speak the same language, something facilitated by the fact that UNILA is composed of multiple cultures. By understanding that the language constitutes an obstacle to the bond, only later the support network tends to be composed of Brazilians. According to Garcia (2012), it is important that there is a wide support network, because, if it is constituted only by peers, the university immigrant will have greater difficulties in learning the language and the local culture, thus limiting the possibility of integration.

In the external sphere, the Portuguese courses for immigrants, the SUS - Brazilian Unified Health System - and the churches were recurrently highlighted as support and welcoming environments. In this aspect, the reception of immigrants is fundamental for the restitution of their vitality and autonomy in the host country and represents a cultural model of coexistence of mutual strengthening.

The psychological care service at UNILA stood out as a space for shelter and support to university immigrants; it welcomed annually about one in ten immigrants enrolled at the university. Thus, the psychological care offered constitutes an institutional support that helps immigrants to deal with psychological suffering, educational adaptation and to develop autonomy and self-care:

“The third year was the year I started seeing a psychologist and it completely changed. You know, like a lot, because my anxiety decreased, I started to heal, to close things, my quality of life improved a lot, and I made the right decisions, I took care of my academic life a lot, I took care of myself a lot!” (P12, Uruguayan female).

The third thematic unit, Leisure and sport, refers to the activities that, according to the participants, provide a reduction of stress and tension of everyday life. On the other hand, these activities also provide sociability and integration with other groups, which favors the construction of various bonds and a new routine. In the studies of Garcia (2012) and Silva and Morais (2012), these activities are also related to the reduction of anxious and depressive symptoms, in addition to promoting mutual identification, belonging and greater social inclusion: “I am the Futsal9director of my athletic club, and on Tuesday and Thursday we play, and it helps me, it clears my mind, it really helps me.” (P6, Colombian male).

Besides the collective activities, more intimate and sublimatory activities were also named as a way to deal with the psychological tension after the arrival in Brazil. Artistic activities were highlighted, which also denote the internalisation of Brazilian culture through music and art. Thus, the identification and valorization of the positive aspects of the local culture, without it being a threat to the cultural heritage of the immigrant, represent, according to Berry (2004), the ideal dynamics in the intercultural encounter, which is integration. Referring to the Brazilian anthropophagic movement, integration would be composed by a swallowing and internalization of the other's culture without the denial of the cultural heritage (Sobrevilla, 2001).

In sequence, the thematic unit Maintenance of the culture of origin brings the experience of immigration as a possibility of "recognition" through the identification with one's own culture and the strengthening of cultural identity, i.e., a return to the cultural framework distanced by immigration. It is important to remember that the identification process refers to the internalization of the object, and, when it is recognized in reality, it feedbacks the libidinal bond and the feeling of security of the ego in the unknown environment (Freud, 2006/1921). Thus, the maintenance of cultural symbols (dance, music, food, language, rites etc.) also constitutes the maintenance of a universe of meanings which tells the subject who he was and where he came from (Hall, 2015; Pocreau, 2018):

“I always... my friends say, they say, you have to play on the guitar a romantic song ((laughs)) or a song from another country. But I like my country very much, I don't know if you know the song 'Condor pasa', it's an indigenous song.” (P10, Peruvian male)

Recovering Winnicott's concept of transitional object (1975), we observed that the permanence of cultural objects represents, for the participants, a bond that supports the cultural identity and allows for stability when facing the internal tension caused by the separation resulting from immigration. Such protective factor was also highlighted by Girardi (2015) and Maciel (2017) and meets the essential role of culture in the constitution of the human psyche and the formation of frames of reference and interpretation of reality (Devereux, 1981). In this regard, culture, as a maternal function, represents the codification and interpretation of reality, and the permanence of these symbolic objects reproduces the cultural cradle that comforts the subject in the face of distress. According to Pocreau (2018), the internalisation of this maternal/cultural care builds a cultural skin that protects the subject from the excitations of the real through a universe of meanings.

The Interculturality, on the other hand, encompasses a series of aspects on creative encounters and cultural exchanges that allow immigrants to break with historical ties, break prejudices, build up transnational social networks and develop new ways of seeing and relating to themselves and the world. The narratives allowed us to observe how interculturality also enabled immigrants to elaborate contents and chains of meaning of their own culture. We highlight, in the following speech, the re-signification of the cultural elements that oppressed the mother tongue and the ethnic identity, in addition to demonstrating the cultural heterogeneity and the power relations around the culture (Hall, 2015; Polar, 2011):

“Because when you are in Bolivia everyone speaks Spanish, Castilian is called there, and when someone speaks in Quechua, it is a bit discriminated against, 'You are a campesino, you such, such, such...'. Then they are ashamed, they never speak Quechua even though they know it, and they don't speak anything in Quechua. (...) And that happened to me, I really wanted to show what I knew and what I spoke. I know how to speak Quechua, so in Quechua one speaks like this, and I started to speak in Quechua with my colleagues.” (P13, Bolivian male).

The last thematic unit, Autonomy, refers to the narratives of the participants who point out how the migration process helped in the development of new ways of dealing with their own decisions, responsibilities, and difficulties. Thus, we highlight two concepts that help us understand the dynamics of this process: resilience and sublimation. The first, as the capacity of reorganization and psychic resistance to adverse situations; and the second, as a defense mechanism capable of transforming a hostile content into something creative and culturally valued (Devereux, 1981; Freud, 2006/1915).

The participants' narratives portrayed how immigration and the adversities encountered can activate creative defence mechanisms and the development of skills to deal with the unbalance of the migratory impact. For example, it was highlighted that the sublimation process makes it possible to transform a disturbing content into a socially valued production, through creative resources that allow repairing the self-image threatened by the cultural shock and that, in this case, also refers to the contribution of university immigrants to the host communities:

“Public transport! That's why my final course assignment is about this. Ah, it was the way, you know. I feel that the city has a problem with this, (...) I will have to do a project, something, find a way to solve this problem. So, everything that bothered me I decided to transform into research ((laughs)).” (P5, Colombian male).

We observed how immigration and intercultural educational experience enabled a process of emancipation and a new subjective positioning in relation to one's own desires and responsibilities. We can highlight the cultural taboos on sexuality and the contribution of immigration in breaking internal and external borders. This emancipation, which refers to the relationship between migration, gender, and culture, was also identified in Assis' research (2007).

Finally, the identification of new meanings of the migratory process initiated by uprooting and the violence of forced immigration also caught our attention. The junction between individual, cultural and political protective factors may enable a buffering of the migratory impact by enhancing resilience and the constitution of a diversified cultural baggage. In this sense, we can consider that, despite the potential negative migratory impact, in the immigration of university students, the protective factors enable a reorganization of the psyche and gains around the intrapersonal and interpersonal growth:

“I matured a lot, a lot... when I came from there to here, I think I was still a teenager, I worked and was a responsible person, but this here, the fact of migrating... I was alone, I ate with homeless people once, I worked as I had never worked in my life, learn another language, I matured a lot, a lot, a lot, a lot! And I think I am a more intelligent person, more prepared for life! (P14, Venezuelan female).

CONCLUSION

After performing this analysis on the experiences and narratives of these 18 UNILA university students, it was possible to identify the pre- and post-migration risk factors. Regarding the risk factors, we observed multiple social, political, and educational realities, which demands caution about generalizations regarding these students. However, social, and educational conflicts in Latin American countries stood out, where the lack of opportunities in free public higher education and the risk of social starvation predominated as elements of social malaise and drivers of migration. Observing the relationship between access to public higher education and the main nationalities that sought a place at UNILA (Paraguay, Colombia, Peru, Haiti, etc.), we can reflect on the phenomenon of certain student migratory flows as an echo of the socio-political realities and the process of dismantling and precariousness of public education in Latin America.

In parallel, the violence of forced immigration and its traumatic force revealed biographies marked by moments of social and psychic vulnerability during the migration process. Regarding family conflicts, these indicated the importance of observing the generational issue in immigration and the dynamics of dependence/independence within these relations. We also noticed how the presence of a history of psychic suffering and the weakening of defences in immigration may favour the reoccurrence of symptoms. Finally, the lack of preparation for immigration was characterised as an element which aggravates the cultural and educational shock upon arrival in Brazil.

With regard to post-migration risk factors, we identified the language difference as one of the main initial difficulties. It also drew our attention the case of Hispanics who felt this impact within a bilingual university, and in a border region with Spanish-speaking countries, which also leads us to think about the linguistic differences and their chains of meaning within a "same language". We also identified that in immigration is intrinsic the dynamics of separations and losses, which made us understand how the distance from the cultural and social universe leads the student to a process of mourning in relation to the country of origin and an ambivalence in relation to the two realities. On several occasions during the interviews, the points that referred to the memories of the homeland were the ones that caused more emotion in the students.

In the new reality, besides grief, the stress to adapt and understand the characteristics of the new society and educational reality prevailed, whose difficulties were accentuated due to the general problems of the city itself. Together with this stress, social class and financial difficulties proved to be important issues for the emergence of a post-migratory malaise. The various forms of discrimination also had a negative impact on the feeling of belonging through speeches or acts that, subtly or directly, exerted a force of inferiorization. In this field, understanding the absence of cultural competence, the narcissism of small differences and historical elements of Brazil and Foz do Iguaçu became pertinent to try to understand the presence of academic ethnocentrism, racism, and selective xenophobia as violence present in the students' experiences. Regarding academic ethnocentrism, we noticed that, besides meaning a silencing and a devaluation of knowledge and culture of the other, it may also represent a veiled facet of xenophobia, or simply the lack of preparation/skills to deal with interculturality in the classroom.