Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 20-Ago-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469826794

ARTICLE

REVISITING THE NOTION OF FIELD BY PIERRE BOURDIEU TO UNDERSTAND THE PRODUCTION OF KNOWLEDGE IN BRAZILIAN PHYSICAL EDUCATION

1Instituto Federal de Minas Gerais (IFMG). Congonhas, MG, Brazil. <rodrigo.gomes@ifmg.edu.br>

2Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. <admir.almeidajunior@gmail.com>

This article aimed to (re) visit Pierre Bourdieu's notion of the field to understand Brazilian Physical Education as a field of non-neutral knowledge production, full of interests in power disputes. The construction of writing took place from two methodological aspects. The first was a bibliographic review of works by Bourdieu and authors of Brazilian Physical Education who studied the author. The second is based on the sociological analysis carried out on the doctoral thesis produced by one of the authors. We consider that the exercise carried out in this article allows us to think about analytical alternatives in the theoretical and methodological construction of new studies. We point out that the field is recent, under construction and permeated by academic / professional tensions that interfere with its identity. The entire route presented explains the interests of agents and institutions that play symbolically in the fabric of their conveniences. We believe it is essential to unveil the multiple elements that intend this field, mainly concerning its institutionalization, increase, and policy.

Keywords: Physical Education; Pierre Bourdieu; the notion of field; professional training

Este artigo teve por objetivo (re) visitar a noção de campo de Pierre Bourdieu para compreender a Educação Física brasileira como um campo de produção de conhecimentos não neutro, repleto de interesses nas disputas pelo poder. A construção da escrita se deu por dois aspectos metodológicos. O primeiro via apreciação bibliográfica de obras de Bourdieu e de autores da Educação Física brasileira que se debruçaram sobre o autor. O segundo alicerçado na análise sociológica realizada na tese doutoral produzida por um dos autores. Consideramos que o exercício realizado neste artigo permite pensar sobre alternativas analíticas na construção teórico-metodológica de novos estudos. Apontamos que o campo é recente, em construção e permeado por tensões acadêmico/profissionais que interferem em sua identidade. Todo o percurso apresentado explica os interesses próprios de agentes e instituições que jogam simbolicamente na trama de suas conveniências. Cremos ser essencial o desvelamento dos múltiplos elementos que tencionam esse campo, principalmente no que diz respeito à sua institucionalização, incremento e política.

Palavras-chave: Educação Física; Pierre Bourdieu; noção de campo; formação profissional

Este artículo tuvo como objetivo (re) visitar la noción de campo de Pierre Bourdieu para entender la Educación Física brasileña como un campo de producción de conocimiento no neutral, lleno de intereses en disputas de poder. La construcción de la escritura se dio por dos aspectos metodológicos. El primero fue una revisión bibliográfica de trabajos de Bourdieu y autores de la Educación Física brasileña que estudiaron al autor. El segundo se basa en el análisis sociológico realizado sobre la tesis doctoral elaborada por uno de los autores. Consideramos que el ejercicio realizado en este artículo nos permite pensar en alternativas analíticas en la construcción teórica y metodológica de nuevos estudios. Señalamos que el campo es reciente, en construcción y permeado por tensiones académicas/profesionales que interfieren con su identidad. Todo el recorrido presentado explica los intereses de agentes e instituciones que juegan simbólicamente en el tejido de sus conveniencias. Creemos que es fundamental develar los múltiples elementos que pretenden este campo, principalmente en lo que se refiere a su institucionalización, incremento y política.

Palabras clave: Educación física; Pierre Bourdieu; noción de campo; formación profesional

INTRODUCTION

In this article we aim to (re)visit Pierre Bourdieu's notion of the field to understand Brazilian Physical Education3, starting from the idea that Physical Education in Brazil is a non-neutral field of knowledge production, full of interests in power struggles. We seek foundations in Bourdieu's theories about the notion of field and authors who have applied this concept (directly or indirectly) in the studies of Brazilian Physical Education (BETTI, 1996; BRACHT, 2003; PAIVA, 2004; STIGGER, et al (2010); LAZZAROTTI FILHO (2011); RIBEIRO (2016), SOUZA NETO, et al (2016); among others).

Bourdieu is one of the contemporary authors who dedicated exhaustively to the systematization of ideas that point to overcoming the objective (objectivist knowledge) and subjective (phenomenological knowledge) paradigms of sociological theorization, based on the dialectical assumptions between agent and social structure. His approach became known as praxiological, which according to Sapiro (2017) sought not to reduce practices to the simple mechanical making of a rule.

In this way, Bourdieu based his propositions on different theoretical conceptions from the objective to the phenomenological, establishing the counterpoints and criticisms that became relevant. He spared no effort to feed back his works, criticizing or reflecting on determinism, structuralism, Marxism, existentialism, constructivism, and neoliberalism. Consequently, he did not establish epistemologically in the common sociological tradition of modernity. He focused on the study of objective structures and subjective representations that until then seemed to reestablish irreconcilable positions (JOURDAIN and NAULIN, 2017).

According to Jourdain and Naulin (2017), Bourdieu overcame the opposition between objectivism and subjectivism that he called genetic structuralism and constant “epistemological surveillance”4. Jourdain and Naulin (2017)state that in the book “In the Words”, Bourdieu expressed his desire to overcome paradigmatic issues. For the authors, the task of (re)visiting Bourdieu requires two essential postures from researchers in the social field. The first has to do with breaking with ordinary language to deal with objective structures and the second reintegrating the subjective worldviews that contribute to the construction of social space.

In this way, the project of sociologically understanding human action made Bourdieu establish his theoretical unity from a system of dense concepts born from the incessant confrontation between theory and empirical practice. Concepts such as habitus, illusion, field, symbolic violence, doxa, corporal hexis, and capital, among others. These concepts renewed sociological analysis and enabled confrontations in research on the relationship between agent and social structure (BARANGER, 2017).

Lahire (2017, p.33) states that in Bourdieu's work, field theory is situated in the continuity of a long tradition of sociological and anthropological reflections on the historical differentiation of social activities or functions and the social division of labor. In this sense, we understand that Bourdieu, if he developed his view of Physical Education today, would not do so as a profession or science but as a field of knowledge production or academic and/or professional field.

Brazilian Physical Education is a field of individuals in different institutional spaces, such as universities, professional councils, social movements, special ministries/secretaries (Education, Health and Sport/Leisure), research and outreach centers, editorial committees, and study groups, among others. From this reality, we understand that the organization of a specific field requires a historical interpretation and apprehension of the social reality.

For Bourdieu (2004) the social constitution of a field, with its peculiarities, its material, and symbolic mottos, is generated in the fabric of reality from the complex relationship between text and context. This means that, in order not to fall into the “short-circuit error” trap, we will need to understand the “relations of force between the different types of capital or, more precisely, between agents sufficiently provided with one of the different types of capital to be able to dominate the corresponding field” (BOURDIEU, 2008, p. 52).

Through this, we understand the need to detail the trajectory of the investigative path that Bourdieu developed when building the concept of the field. The process of (re)visiting this concept is based on two methodological aspects. The first is based on the bibliographical appreciation of works by Bourdieu and authors of Brazilian Physical Education who, in recent decades, have invested efforts to contextualize the field of Physical Education immersed in power relations. The second is based on the sociological analysis carried out on a doctoral thesis developed by one of the authors. Next, we present Pierre Bourdieu's considerations on the concept of field.

PIERRE BOURDIEU'S CONSIDERATIONS ABOUT FIELD

In Bourdieu's theoretical production, the considerations about the field and the concepts of habitus, capital, and power become essential to understanding social life and its practice. We follow the logic developed by the author that his considerations about the field are closely linked to the theoretical body of production of the concepts carried out throughout his research. Thus, we consider important the foundation of concepts such as habitus, capital, and power that surround in a systemic logic the concept of field and can only be applied in a theoretical perspective linked to the social reality of the field and never of isolated or reduced form.

In this sense, the concepts are articulated in a symbiotic way. We will not make considerations about the social characteristics of a field without delegating importance to the epistemological foundations that bring the other concepts. This dynamic was not explicitly organized by Bourdieu, that is, the author did not pedagogically construct this relationship in a specific text, but in many of his works he clarifies that his concepts, or the appropriation of his concepts, is given in an empirical, systematized and within the theoretical code in which practices are constituted and signified by agents and institutions.

Regarding the constitution of these concepts, Thiry-Cherques (2006) explains that the primary concepts formulated and perfected by Bourdieu were: habitus and field. Secondarily, other concepts were added forming a network of interactions that guided relational sociology, the explanation, based on an analysis, generally based on statistics, of the internal relations of the social object. Theories about field and habitus are entangled and complement each other in their possibilities, consequences, and reflections, however, they must be understood in a particular way so that they can subsequently imply complementation.

According to Martinez and Campos (2015), the concept of the field appeared in Bourdieu’s research as a “conceptual stenography”, that is, a form of writing that uses special abbreviated characters, allowing words to be written down as quickly as are pronounced. This allowed Bourdieu not to limit only to the exercise of internal interpretation of the external explanation, since in all cases there are cultural inferences specific to agents and institutions that imply the construction of the social. Therefore, his creative exercise was based on theoretical relativizations and constant epistemological vigilance in the use of words and terms.

The emergence of the concept of the field took place at a time when Bourdieu's research was around a review of the sociology of religion (commentary on the chapter devoted to religious sociology in Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft5) and on the sociology of art (in the seminar at Escola Normal, around 1960). Bourdieu (2004a) stated that his theoretical intentions, those that are condensed in the concepts of habitus, for example, were present in an unclear and elaborate way, since the origin of his work. In this way, it is essential to reveal that the concept of field is much more recent than one might imagine and was used in an inaugural way by Bourdieu in research on the French intellectual and artistic “context”, taking greater vent throughout the 1980s.

Evidently in the 1980s and 1990s, Bourdieu improved the concept of the field in his writings and reflections. We emphasize that the term was not forged unilaterally by the author. Lahire (2017) recalls that Bourdieu defined the notion of the field through the combination of properties belonging to different theoretical universes, in particular those of Durkheim and Weber. Furthermore, authors such as Merleau-Ponty and Sartre had already applied this terminology in their epistemological aspects. However, Bourdieu (2004b, p.56) set the tone for the concept he cut, remembering that “it is possible to have an impression of "imprecision" in the face of certain notions I forged, if we consider them as the product of a conceptual work, when in fact I endeavored to make them work in empirical analyses, rather than letting them 'turn around'”.

Based on this revelation, Bourdieu (2004b) explains that the notion of field, in its condensed form, is a research program and a principle of defense against a whole set of errors in the social sciences, as well as the other notions established by him. For the author, concepts can and should remain open, and provisional, which does not mean vague, approximate, or confused. Bourdieu (2004b) clarifies that all true reflection on scientific practice attests that this opening of concepts, which gives it a “suggestive” character, immediately, an ability to produce scientific effects, showing things not seen, suggesting research to be done, and not just comments. In this logic, he developed the field considerations clarifying that:

...all cultural productions, philosophy, history, science, art, literature, etc., are objects of analysis with scientific pretensions. There is a history of literature, a history of philosophy, a history of the sciences, etc., and in all these fields one finds the same opposition, the same antagonism, often regarded as irreducible - the realm of art, of course, one of the places where this opposition is strongest - between interpretations that can be called internalist or internal and those that can be called externalist or external (BOURDIEU, 2004b, p.19).

Through this critical perspective, Bourdieu traced a series of considerations in an attempt to rectify the different points of view, subjective and objective, that routinely crossed his findings and held reductions or overestimations about the social fabric, mainly, in the idea of making it understood that in the different fields, there are struggles arising from historicity that needed to be systematically analyzed and understood. Pereira (2015) collaborates in this reasoning, remembering that thinking from the concept of field is thinking relationally. It is to conceive the object or phenomenon in constant relationship and movement. According to the author, the field also presupposes confrontation, taking a position, struggle, tension, and power, since, for Bourdieu, every field “is a field of forces and a field of struggles to conserve or transform this field of forces” (BOURDIEU, 2004, p. 22).

Thus, Bourdieu (2004a) qualifies that, to establish considerations about the field, one cannot fall into the trap of ready-made answers to any questions, as theorists, positivists and those conditioned by hierarchies constantly do. He reminds us that placing science, and more specifically, the science of science, at the service of the progress of science, with purely descriptive analyzes is a danger and a risk to science. Thus, we perceive the virtue of the concept of field. It makes it possible to break with knowledge first, which is necessarily partial and arbitrary. Bourdieu (2004a) seeks to promote a mode of construction that always needs to be rethought, through this key concept that implies relational reasoning in an attempt to clarify the hidden constructions and battles within each field or subfield.

In this way, the considerations about the field allow us to break with the allusions to the social world that do not satisfactorily manifest its conflictual nature. Martinez and Campos (2015) state that for Bourdieu, the social structure of a given society is based on the social division of labor, a fact that allows agents with their practices, and institutions, to move in the field of a market material and a symbolic market. It is essential to the position that the field appreciation considers the social situations of power disputes within it. For this reason, Bourdieu elaborates the observation that even neutral practices will be linked to systems of social and intellectual differentiations.

Therefore, the concept of field proposed by Bourdieu is defined as a space where relationships between individuals, groups, and social structures occur, with a dynamic that obeys its laws, provoked by the power disputes that occur within it as a relational space (MARTINEZ; CAMPOS, 2015). Therefore, Bourdieu (2003) draws the concept based on a state of the power relationship between agents and/or institutions that are engaged in the struggle or in the distribution of specific capital that, accumulated in the course of previous struggles, guides later strategies in the permanence or alteration of the habitus (“the field structures the habitus and the habitus constitutes the field” (BOURDIEU, 2004c).

From this logic, it is important to reinforce that each field creates its object and its principle of understanding and can be analyzed regardless of the characteristics of its occupants, that is, they are microcosms surrounded by specific laws, values (capitals), objects and interests endowed with (relative) autonomy within the social world (THIRY-CHERQUES, 2006). The degree of autonomy of each field occurs when inherent laws are somehow influenced by the macrocosm (BOURDIEU, 2004b). Therefore, “the more autonomous a field, the greater its refractive power and the more external impositions will be transfigured, to the point, often, of becoming perfectly unrecognizable.” (BOURDIEU, 2004b, p. 22).

This means that the more connected the field is internal, its capacity for autonomy will be increased and its amplitude of interference from prerogatives or external pressures will be reduced. On the other hand, the acceptance of norms that are not specific to the field, but that agents recognize as valid to guide their conscience and moral discernment - heteronomy of a field - will be manifested by issues that concern external problems, that is, not of the field, especially political problems, which are directly signified in each specific historical context. Thiry-Cherques (2006) reminds us that all this problem determines the way we consume not only things but also education, the arts, and politics and also how we produce and accumulate them in the competition for the domination of a specific capital.

Despite all the statements presented so far, it is important to highlight what Bourdieu referred to as a field. Earlier we commented that this notion presupposes a break with the realistic representation that leads us to reduce the effect of the environment to the effect of direct action, as it is updated during an interaction. In this way, we cannot let it go unnoticed that agents are essential in our analysis, but they do not represent a single view of the whole, as institutions constitute, together with agents, deep relationships that underpin each way of living in the countryside. Therefore, we present below a quote in which Bourdieu analytically explains this construction that he designated as a field:

…a field can be defined as a red or a configuration of objective relationships between positions. These positions are objectively defined, in their existence and the determinations they impose on their occupants, agents, or institutions, due to their present and potential situation (situs) in the distribution structure of species of power (capital) whose position orders access to the specific advantages that are in play in the field, as well as by their objective relationship with other positions (domination, subordination, homology, etc.). In highly differentiated societies, the social cosmos is made up of several of these relatively autonomous social microcosms, that is, spaces of objective relationships that are the site of a specific and irreducible logic and need to those that regulate other fields (BOURDIEU; WACQUANT, 2005, p.150).

This statement appeared in the work “An invitation to reflexive sociology6” published for the first time in 1992. This demonstrates how mature and reflective the construction of this term was, given Bourdieu's investments in establishing debates with other academics who approached and criticized his publications. It is also essential to explain that Bourdieu (2003) places an analogy, comparing a field to a game. Consequently, each field is established as a game. In this “act of playing”, the subjects' positions are related to the positions they have acquired within the structure of the field to conserve or transform them, as well as to capitals, doxa7, nomos8, habitus, and goals that guide their demands.

In this sense, the logic of the game for Bourdieu (2004b) is to allow a diversity of moves adapted to the infinity of possible situations, which no rule, however complex, can anticipate. This means that we must remain attentive to the functioning of the game, in its internal disputes, its interests, the peculiarities of the plays, the individuals who play, and the habitus that designates their positions, seeking to understand the production of laws and their recognition. That is why Bourdieu (2003) clarifies that the habitus is both the condition for the functioning of the field and the product of this functioning. The meaning given by Bourdieu to the game is precisely the condition of the agents consenting to the rules of the field, but still acting strategically guided by the habitus.

Thiry-Cherques (2006) explains that the term habitus permeates between structure and action and was adopted by Bourdieu in the expectation of being different from concepts such as habit, custom, praxis, and tradition. The author explains that for Bourdieu, there is a correspondence between durable and transferable dispositions that punctually organize practices and representations in human existence or the condition of this existence. In this way, the habitus is what guarantees logic, practical rationality, and irreducible theoretical reason. It is acquired through social interaction and, at the same time, it is the classifier and organizer of this interaction. It leads us to perceive, judge, and value the world, conforming us and simultaneously making us act, as they are structures and are structuring with autonomous dynamics that do not designate a conscious orientation in the two variations, that is, it is generated by the logic of the social field and this way allows us to learn and transmit the different knowledge and to correlate them socially.

In this reasoning, habitus is a “system of dispositions acquired by implicit or explicit learning that works as a system of generating schemes” (BOURDIEU, 2003, p. 125) causing strategies, many times, conformed to the interests of others without necessarily being destined to lead them. Therefore, everything that happens in the intimacy of field relationships is processed in a set of habitus and it is important to highlight that it develops individually and socially, that is, the process of internalization of objective issues is not only in the agent, is also in the group. It is this effect that we must keep in mind as a scheme that works in practical action and makes the social agent inserted in the context and not just conditioned by it.

Bourdieu (2004b) recalls that to the extent that social agents are organized, conquering their positions within the field and incorporating the habitus meaning schemes, they can evidence the knowledge socially constituted in their actions (practical strategies). Therefore, they do not need the systematic orientation of logic or reason (habitus is infraconscious, partially autonomous, historical, and stuck in the middle). At that moment, he will act without conscious control, that is to say, it is a principle of knowledge without conscience, of intentionality without intention (BOURDIEU, 2004b), which leads us to realize that its functioning is established as a scheme of actions, perceptions, and reflections of the bodies and minds of agents related to their collectivities.

This means that throughout our lives the mental structures through which we apprehend the social, and which are the product of the interiorization of the social, generate worldviews that contribute to the construction of this world. It is how perceptual dispositions tend to adjust to position, agents, even the most underprivileged, tend to perceive the world as self-evident and to accept it much more broadly than one might imagine, especially when looking at the situation of the dominated with the social eye of a dominant (BOURDIEU, 2004b). Consequently, from this process, habitus leads to regular behaviors, which allow for the prediction of practices, of what to do and what not to do, in a given field (BOURDIEU, 2004b).

In this way, as a system of dispositions for the practice, the habitus is an objective foundation of regular conduct and the prediction of the practices, because the habitus makes the agents behave in a certain way in certain circumstances. Therefore, this tendency to act regularly does not originate in a rule or a law (BOURDIEU, 2004b).

Going a little deeper into Bourdieu's theoretical correlations, we need to reflect that the author, when treating the field as a space of social positions, will consider that practices must be carefully analyzed from the hierarchical aspect of the power relations between the individuals, groups or institutions that belong to the field (social relations, habitus, and power).

In the particular case of the power aspect, we will make a correlation on what Bourdieu called “symbolic power”. According to Hey (2017), symbolic power is inscribed in the perspective of analyzing the symbolic dimension as a structuring of the social order, directly relating to the notions of capital, violence, and domination, and is connected to the political magnitude of the social organization since the adjustment to a symbolic order happens through the imposition of structuring structures that adjust to the objective structures of the social world. The political context prioritizes symbolic power by building the social reality that seeks to establish order and meaning in the social field, acting in a system of domination that contributes to cognitively ordering agents and institutions within that order.

Hey (2017) explains that such order is inscribed in power relations, often established as the natural order of things. In this sense, it is necessary to discover when it is less recognized and when it is more recognized, that is, symbolic power is this invisible power that can only be exercised with the complicity of those who do not want to know about its subjection or even of its execution. Therefore, it is a process that demands adjustments between the objective structures and the structures incorporated in the magnitude to exert a social force that seems to have always existed. “Symbolic power, subordinate power, is a transformed form, that is to say unrecognizable, transfigured and legitimized, from other forms of power” (BOURDIEU, 2009, p.15).

Therefore, Bourdieu (2009) questions how the dominated fit into a certain social order by subordinating and ensuring that it is maintained. Furthermore, he interrogates how acts of subversion and conservation alternate as the cognitive actions of agents pass through principles of worldview. These actions have to do with perceptions, principles, and reflections on the division of the social world. All of this is constituted by social struggles. These struggles arise from conflicts between groups that seek, through symbolic legitimation, to establish how the world should be. Knowledge of the social world and, more precisely, the categories at stake in the political struggle, struggle at the same time theoretical and practical for the power to preserve or transform the social world by conserving or transforming the categories of perception of that world (BOURDIEU, 2009, p.142).

Therefore, we can understand that the field is established as the space of power relations with the struggles involving disputes for specific capital, whether in the cultural, religious, artistic, political, economic field, or any other that establishes this contestation (BOURDIEU; WACQUANT, 2005). What allows the distribution of the specific capital of a field among the agents is how the structure was determined. Agents confront each other for the legitimacy of their capital to reach the desired position and in this logic, the distribution happens unevenly, hierarchizing the positions between subordinates and non-subordinates. This struggle entails opposition between the dominant and the subordinate, since those who “dominate” have specific capital and can distribute it to maintain power, and those who are “subordinate” are on the sidelines of the appropriation of this capital.

In this way, it is necessary to provide further clarifications on the concept of capital to understand how it unfolds in the relationship with considerations about field, habitus, and power. According to Thiry-Charques (2006), Bourdieu develops the concept of capital from the principles of economics, that is, accumulation takes place through financial acquisitions through the skills that agents have to invest (explicitly economic capital). In this analogy, the accumulation of the various forms of capital takes place through investment. Bourdieu (1986) explains that capital is accumulated labor (in its materialized form or its embodied form) that, when appropriated by agents or groups of agents, allows them to appropriate social energy in the form of living or reified labor.

From this perspective, capital accumulation, in its objectified or embodied forms, takes time. It is impossible to explain the structure and functioning of the social world unless capital is reintroduced in all its forms (social, cultural, and symbolic) and not just in the only form recognized by economic theory (economic capital). In this sense, depending on the field in which they develop and at the expense of investments for transformations, they are more or less effective in the field (BOURDIEU, 1986). The concept of capital is, etymologically, the same as that of leather or a set of goods, but in addition to the economic prerogative (material wealth, money, goods, patrimony, work), Bourdieu considers as capital: social capital; cultural capital and symbolic capital.

Social capital corresponds to the sum of social accesses and encompasses the relationship and network of mutual contacts institutionalized in social fields. Bourdieu (2003) states that building the concept of social capital is to produce the means of analyzing the logic in which this capital is accumulated, transmitted, and reproduced, and the perspective of how it is transformed into economic capital and vice versa. He also states that social capital is the means of apprehending the functions of institutions such as clubs, companies, schools, or, simply, the family, the main place of accumulation and transmission of this kind of capital. Hence the importance of realizing that for certain people social capital is what allows their power and authority relevant to their engagement and activity in the field.

Cultural capital is the knowledge, skills, information, and all intellectual manifestations produced and transmitted by school institutions, but originally by the family. They happen through some circumstances that Bourdieu called “state”: incorporated; objectified and institutionalized. The embodied state is what has to do with the enduring dispositions of the mind and body. The objectified state is what is presented in the form of cultural goods, such as books, works, paintings, and equipment, among others, which materialize the trace or performance of theories, their criticisms, or problematizations. The institutionalized state is in the form of objectification and we must separate it, as it confers essential and original properties on cultural capital as a prerogative of sanction. This is the case, for example, with the acquisition of academic titles (BOURDIEU, 1986).

On the other hand, symbolic capital is the set of rituals of social recognition and comprising prestige, honor, and status, that is, designating the effects of other forms of capital, as it is symbolically apprehended in a connection of social importance in which those relationships that translate the clothing of the position or the conquest of position within the field must pre-exist. Such relationships only make sense when agents share their meaning and recognize their importance (a title, a position, an indication) within the game. Symbolic capital is a synthesis of the others (economic, cultural, and social) and these forms of capital are convertible into each other, for example, economic capital can be converted into symbolic capital and vice versa, as in the other forms (BOURDIEU, 2003).

According to Bourdieu; Wacquant (2005, p.152) this occurs because the value of a type of capital depends on the existence of the game, on a field where competence can be used, with a kind of capital, one that is effective in a certain field and that allows its possessors to have a power, an influence. In this way, we can see how the notions of capital, habitus, and power are extremely interconnected. This connection makes up the state of power relations between players and defines the structure of the field and the accumulation/distribution of capital. It is important to highlight that the concepts of economic capital, social capital, and especially cultural capital became determinant in the reflections and interpretations of Bourdieu's theory on the legal field, the artistic field, and the scientific field, among others. There is no doubt that they brought important contributions to understanding the field of Physical Education in Brazil.

This puts us in a position of constant alert and facing an analytical challenge. We must debate the field of knowledge production of Physical Education in the specific and expanded field of power. We need to understand the positions occupied by agents and institutions that compete for the symbolic capital of the field and we need to reflect on the forms and distribution of capital among agents.

So far, we have focused on presenting, contextualizing and systematizing Bourdieu's theory focused on his considerations about the field. Next, we will establish approximations with Physical Education theorists who, from Bourdieu, guided their research seeking to understand the constitution of the field of production of knowledge of Physical Education in Brazil.

REVISITING PIERRE BOURDIEU'S NOTION OF FIELD TO UNDERSTAND THE PRODUCTION OF KNOWLEDGE IN BRAZILIAN PHYSICAL EDUCATION

According to Lahire (2017, p. 29) “good sociological concepts are those that increase the scientific imagination and that constrain, at the same time, the unprecedented empirical tasks” of scholars in the social field. In this sense, the concept of field is a useful concept for sociological research, and in particular, the research9 that gave rise to this article, for establishing the theoretical requirements of relational and structural thinking that enabled us to understand Brazilian Physical Education as one of these social microcosms in the macrocosm constituted by the social space of Brazil.

It is essential to point out that we agree with Lahire (2017) that Bourdieu's notion of the field has advanced successfully in terms of his strategy of revealing interests and struggles beyond economic reductionism. However, we understand that this theory does not permeate the boundaries of other issues that Lahire (2017) points out as crucial: the degree of professionalization of the field; the relationship between agents, their productions, and the public assisted; the agents' degree of esotericism in their practices; the participation of the same individuals in various social universes; among others.

Thus, it is important to understand the construction of the field of knowledge production of Physical Education in its various peculiarities: political, economic, and cultural. These social and historical conditions allow the existence of the field. Over the last four decades, Physical Education reveals specific imperatives that emerged from the historical relationships between agents and institutions involved in power struggles for sovereignty in the countryside. The ways of producing knowledge in universities that come and go from the job market have always been polarized in different worldviews that over the years have been mixed between hygienist, moralist, sportsman, pedagogist, constructivist, and biologists, among others.

In this way, we can say that Physical Education has been configured in its condition as a relatively autonomous field, as it has several characteristics that range from its organization as a space for professional activity; to passing through the institutionalization of professional training at a higher level (graduate and bachelor's degree courses); and the different possibilities in postgraduate studies (education, leisure, sport, health, training, among others), with research groups, congresses, and events, to the formulation of specific legislation on the regulation of the profession in Brazil.

This group of social constructions made us realize that beyond the specificity of the “scientific-academic field” (which in our study is crucial), Physical Education has been constituted as a field of knowledge production. In this sense, we consider that it is not only the knowledge from universities that disputes this space of power but the Federal Council of Physical Education (CONFEF); legislative/normative proposals; the training centers; the clubs; the academies; the schools. Finally, there is a series of institutions and agents that articulate in this space and intend professional training policies (directly or indirectly). That is why we do not immediately adhere to the idea of “academic field” or “scientific field”, because we believe in the multiple contexts of occupation that agents assume in university and non-university institutions, demanding a more correlated and expanded analysis.

Lazzarotti Son; et al (2014) noted that the appropriation of Bourdieu's concepts to study the field of Physical Education has been an experience applied by some authors in different historical moments and different investigative approaches. Since Betti (1996), Ferraz (1999), Bracht; et al (2011), and Paiva (1994, 2004, 2014) through authors such as Souza and Marchi Júnior (2010 and 2011), Stigger; et al (2010), until more recently with Lazzarotti Filho (2011); Lazzarotti Son; et al (2014), Ribeiro (2016), Souza Neto; et al (2016), among others. Some of these authors developed their studies on the field of Physical Education relating it to the sports field, and other authors on the field of Physical Education in the school context. In a more interested way, we searched for authors who appropriated Bourdieu's concept, considering Physical Education as an academic-scientific field and its consequences on curricular policies.

Thus, we understand that in the process of appropriation of ideas, many of these authors reinforce the understanding that Physical Education is a field under construction, relatively contemporary and that needs to be studied through its characteristics that establish its idiosyncrasy. Paiva (2004) clarifies that the field of Physical Education has been gradually acquiring autonomy, mainly due to its constitution as a field of knowledge production from the academic-professional perspective. In Brazil, this process took place late, in the last decades of the 20th century and the first decades of the 21st century, with the maturation and systematization of a series of studies and research.

Previously, the field has gone through different formats in what gives the logic of dispute for power. Paiva (2004) recalls that the 30s and 80s of the 20th century were decisive for Brazilian Physical Education. In the 1930s, the engendering of the field of Physical Education took place, whose configuration was based on forces external to the field10. These forces, even external ones, made possible the identity of the field. Initially, closely linked to the pedagogical field, Physical Education was addressed as a practice and seen from the outside (marked and postulated by other forms of knowledge production, basically the hard sciences and a functionalist context of education).

Subsequently, according to Paiva (2014, p. 72), “the social reach that the sports phenomenon acquires changes the corporal cultural practice that supports Physical Education”, submitting the Physical Education field to the sports field and tensioning the representations, the practices, and forms of capital distribution in school and non-school Physical Education. Paiva (2004) states that the 1980s were decisive for Brazilian Physical Education, especially after the country's re-democratization, because a series of scholars started debates, tensions, and questions about the representations of Physical Education in its modes of production, reproduction, and relationship with science, incorporating broader political, epistemological, social and educational discussions that are more engaged in the context, going beyond sports prerogatives.

This points to an interesting picture of relationships that originated in this period. We realized that vigorously, certain characteristics were forged and still forge the habitus in the countryside and give strength to certain types of capital that intersect the power struggles for sovereignty in the countryside, mainly from the political and epistemological perspective. Lazzarotti Filho (2011) reinforces that in recent decades the field of Physical Education has undergone constant transformations from certain objects of dispute. We understand that such objects are mainly centered on the relationship between Physical Education and Education processes (from kindergarten to higher education); with the regulatory framework of the profession (law nº 9696/1998) and with the incorporation of the academic-scientific habitus that stimulated new ways of thinking, acting and doing in/from the field.

Furthermore, according to Lazzarotti Filho; et al (2014) this universe of relationships allows accessing the theory of Bourdieu (2009), as it shows that the field of Physical Education is constituted in a social world like the others, obeying general and specific social laws and that to a certain extent brought relative autonomy to the field. For the authors (p.70) “this perspective is supported by a theory of practice, a mediation or, as Bourdieu (2009) called it, a relational theory that seeks to oppose the extremes developed by the so-called objectivist and subjectivist theories”, that is, Physical Education is a social microcosm with its laws, with agents, institutions, customs and practices that produce, reproduce and disseminate knowledge.

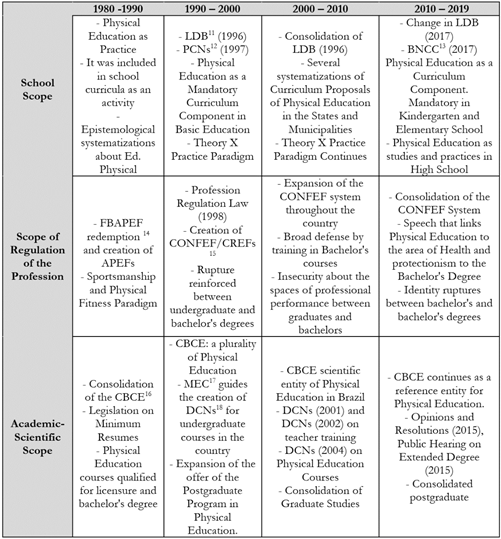

To better clarify this reasoning, we developed a table, a model of thought, based on different authors, entities, organizations, and legislation that in the last four decades have played a leading role in the dispute for power in the field of Physical Education. These institutions and/or agents try to demarcate a way of being, thinking, acting, (re)producing knowledge, and becoming, by social effect, the reference on Physical Education in the Brazilian context (an aspect of sovereignty). We remember that the most important areas of this dispute had and still correspond to notions of what Physical Education is inside and outside the school universe. Below we present this schema of thought to illustrate the context:

Source: Own elaboration based on Lazzarotti Filho (2011); Paiva (2004); LDB (2017); DCNs (2001); DCNs (2002); DCNs (2004), Law 9696/98; Official website CONFEF/CREFs System (2018).

Box 01 Scheme to think about the field of knowledge production of Brazilian Physical Education in the last four decades.

The scheme presented allows us, in a succinct and brief but conscious and in-depth way, to observe the dense power relations and the origins of the disputes for the symbolic capital of the field in different historical scenarios of recent times. We point out that there has always been a rich circulation of agents between the various institutions or areas that support Brazilian Physical Education in epistemological positions, sometimes divergent, sometimes convergent. In many cases, political tensions were amplified and conflicts surfaced by the attempt to impose a way of acting that competes with a way of producing knowledge from/in the field.

An example that emerges from this scheme is the constant tendency to establish and maintain a way of regulating the field via legislation for the professionalization of the individual who graduates in Physical Education, as well as the construction of paradigms to found Physical Education via certain epistemological positions interested (school paradigm, sports paradigm, physical fitness paradigm, market paradigm, health paradigm, among others).

In this way, the field of Physical Education comprises different instances, but with permanent dialogues and conflicts. We believe it is important to briefly point out each of these institutions and reflect on the context of permanence, subversion, and conservation of agents in these different spaces. We emphasize that the movement of agents through different institutions is a striking feature in the scope of Brazilian Physical Education. In this way, the following institutions became important for our object of investigation: the CBCE - Brazilian College of Sports Science; the FBAPEF - Brazilian Federation of Associations of Physical Education Professionals and the APEFs - Associations of Physical Education Teachers; the CONFEF - Federal Council of Physical Education and the CREFs - Regional Councils of Physical Education; the IES - Higher Education Institutions and the CNE - National Council of Education via CES - Chamber of Higher Education of the MEC - Ministry of Education.

The CBCE is the main scientific entity of Physical Education in the country. According to information on the official website, it emerged in 1978 under the pretext of disseminating scientificity linked to a medical discourse and human performance linked to sports and physical training. In 1989, due to a change in power in the management of the CBCE, the organization began to observe Physical Education in its epistemological multiplicity, breaking the paradigm of knowledge production that linked only physical fitness related to health within its events and scientific exhibitions. Lazzarotti Filho (2011, p. 52) recalls that the idea was to transform the CBCE and its modes of academic production, based on the understanding “that Physical Education is based on pedagogical work, directing its actions towards this object and placing it as deserving of attention and dispute in the entity”. Since then, the CBCE has been consolidated with great force in this logic of scientific policy, promoting debates, and congresses, publishing several research results, and favoring the development of the multiple academic perspectives that form Physical Education.

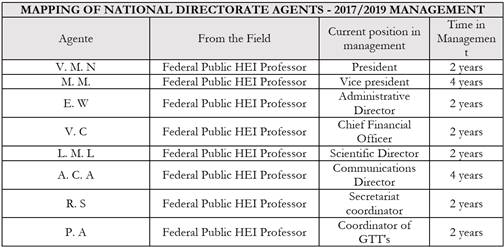

Currently, the CBCE brings together researchers linked to the field of Physical Education/Sports Sciences. The official website informs that the institutional organization takes place in State Secretariats and GTT's - Thematic Working Groups, led by a National Directorate. It has representations in various government agencies and links with the Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science. When visiting the history of the composition of the national boards of the CBCE, we noticed the alternation of agents in the management positions and the possibility of different subjects occupying positions of power within the institution.

Source: Own elaboration based on searches on the official website of the CBCE: http://www.cbce.org.br/dn-passadas.php

Box 02 - Mapping of agents working in the CBCE in the National Directorate.

The management (2017/2019) consisted mainly of public university employees. This composition suggests the strength of the production of knowledge that emerges from Brazilian Public HEIs. They occupy only twenty percent of the demand for higher education19 in Brazil, against eighty percent of private Higher Education Institutions. Even with this numerical disadvantage, public HEIs are positioned as an almost unique alternative to the development of research in the country. The performance table of public HEI teachers at the CBCE follows the data on this reality and reinforces the concentration of interest of public agents in mobilizing the academic/scientific engagement of Brazilian Physical Education.

About FBAPEF and APEFs, it is important to contextualize that historically they marked the dispute over the control and organization of professional performance in the field. According to Sartori (2006), APEFs are associative institutions at the municipal and state levels that seek to develop the professional category in Physical Education in a technical, social and political way. The first APEF emerged concomitantly with the creation of higher education courses in Physical Education in Brazil in the 1930s. Only in 1946 was the Brazilian Federation of Physical Education Teachers' Associations organized, largely made up of teachers from the Southeast region of the country. The intention was to consolidate power of influence for the creation of the Professional Council of Physical Education Teachers.

Sartori (2006) recalls that over the years APEFs have expanded throughout the country, organizing the professional category through congresses, forums, collective political actions, social activities, provision of services to the community of Physical Education teachers, publication of books and magazines on topics that promoted Physical Education as a profession. However, in the 1970s, this expansion began to show a decline, mainly due to the return of professors who were abroad to graduate studies and the creation of the CBCE.

This led several Physical Education agents to think more focused on the scientific-academic field. We highlight here the first clashes between modes of production and thought that generated divergences. There is a dichotomization between “being a teacher” and “being a professional” in Physical Education. In this context, in 1985 there was the first attempt to regulate the profession in Physical Education, which was approved by Congress and vetoed by the president at the time, José Sarney.

Only in 1995, a new process takes place to regulate the profession with the Brazilian legislative and executive powers. Nozaki (2004) clarifies that the bill nº 330/95 began to be discussed among peers and in 1996 a public hearing took place in which Jorge Steinhilber (current president of the CONFEF/CREFs system, in office for more than 20 consecutive years) detailed several positive aspects about the regulation of the profession, supported by representatives of the National Institute for the Development of Sport - INDESP, FBAPEF, and several APEFs. On the contrary, in this same plenary of the public hearing, the board of the Brazilian College of Sports Sciences - CBCE and the board of the National Executive of Physical Education Students (CONFEF, 2018) were opposed to the regulation of the profession.

In this way, and after remaining a year in the Chamber of Deputies, the project was approved in the Senate in 1998. Fernando Henrique Cardoso, President of the Republic, sanctioned Law nº 9.696/98 that regulated the profession of Physical Education and created the CONFEF/CREFs system. Nozaki (2005) is one of the authors who criticize the regulation of the profession. According to him, the regulation was supported by corporatist arguments of market reserve and, consequently, of the attempt and occupation of a power group that gained political strength at the federal level.

The CONFEF/CREFs system then stands out in the most varied correlations of disputes for the symbolic, economic, and cultural capital of Physical Education in Brazil. It is essential to point out that a professional council has very specific management and operating duties. According to federal legislation, it “aims to defend society, ensuring the quality of the professional services offered in the area of physical, sports and similar activities, and the harmony of the entities of the CONFEF/CREFs system”. The CREFs “is intended to promote the duties and defend the rights of Physical Education professionals and legal entities that are registered in them” (CONFEF, 2010). This means that what legitimates a professional council is its presence in society in an inspection/regulatory way, establishing its matrix at the level of ethical labor relations.

In 2019, the CONFEF/CREFs system completed 21 years old with very peculiar management characteristics. One of them is the permanence of a specific group in the direction of the council. Despite the existence of an electoral process, there was never any change in the representatives that make up the dome of power of this council (there was never any change in the presidency, for example). Within the scope of regional councils, in some states, this characteristic is established as a modo operanti. In Minas Gerais, a group remains in power for another 20 years.

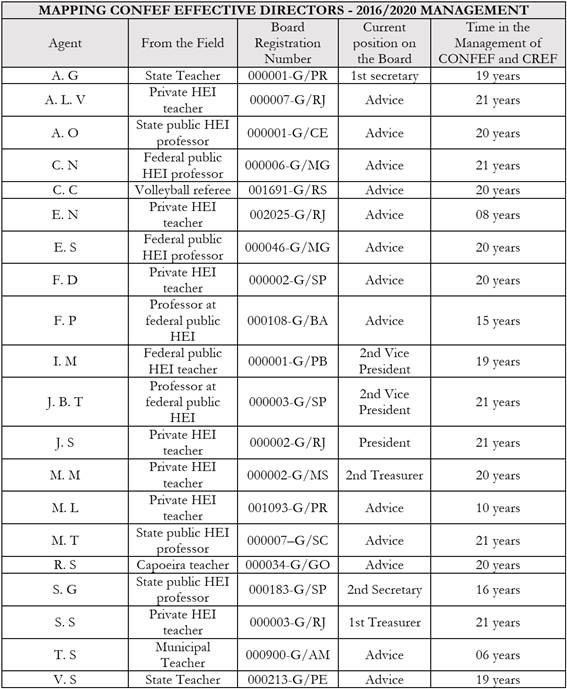

According to the official website of CONFEF, from 2016 to 2020, around 20 Physical Education professionals with different profiles and origins from/in the field act as effective counselors. Next, we create a chart in the form of a mapping of these counselors. We must carry out an analytical exercise on these agents. Reflect on how they established in the countryside and how they compete for capital (symbolic, cultural, political and economic). This can affect the modes of production of knowledge of Physical Education in Brazil for certain interests. We note that this schematization was based on public documents manifested in official communication channels of the council, as well as the exhaustive analysis of the lattes curricula of each councilor.

Source: Own elaboration based on: Searches by lattes curriculum via: http://buscatextual.cnpq.br/buscatextual of each agent. Access to the official website of CONFEF and the websites of the respective CREFs, consulting the history and trajectory of the counselors. Access to the Official Gazette of the Union in the conference of appointments and dismissals, electoral processes, approval, and impediment of chats related to CONFEF.

Box 03 - Mapping of agents who work in CONFEF as effective advisers. Its origin/conservation in the field of Physical Education.

By explicitly interpreting this mapping, we realize that the current board of CONFEF, especially the councilors sworn in as senior managers, have been in power for more than 20 consecutive years. Most counselors maintain teaching in higher education as an elementary activity, which suggests, as a hypothesis, the possibility of direct-indirect interference in university curricula. Another interesting fact is the diversity of members who circulate through the different spaces of the countryside (public HEIs, private HEIs, city halls, state agencies, sports training centers) which indicates high permeability of these subjects and accumulation of capital: political and social beyond capital accumulated within the board. However, the greater circulation of these agents is inscribed in the university environment. In this way, there may be, narratives about the academic curriculum that benefit the interests of the professional counsel and the counselors.

In this sense, Bourdieu (2011, p.115) clarifies that “university capital is obtained and maintained through the occupation of positions that allow dominating other positions and their occupants”. The game of social domination is reproduced in the academic sphere, ranking positions, and shaping certain school structures. For Bourdieu (2011, p. 116) “this power over the reproduction instances of the university body assures its holders a statuary authority, a kind of function attribute that is much more linked to the hierarchical position than to the extraordinary properties of the work or the person”.

Consequently, what we seek as a reflection is not the mischaracterization of the professional regulation entity of Physical Education. On the contrary, we try to understand how entities and/or agents, from an occupation of power, start to interfere or try to interfere, in institutional spaces, as in the case of the council towards the universities and the universities towards the council. Bourdieu (2011, p.116) converges our reflection with very enlightening facts. For the author “the extent of the semi-institutionalized power that each agent can exercise in each of the positions of power he occupies, his 'weight' as we say, depends on all the attributes of power he possesses elsewhere and on all the possibilities exchange that he can obtain from his different positions”.

The correlations in the game that are built within a field are always permeated by representations, symbols, actions, and processes favored by the accumulation of capital and consequently the uses of consolidated positions of power.

Saying in another way, each agent imports to each one of the secondary institutions the weight that he holds generically, but also personally (for example, with the title of president or gran elector) while I am a member of the highest institution of the one that is part of the group that the members of the lower-ranking institutions in which they intervene, in a hierarchical universe founded on the competition, aspire by definition. […] Here, the capital calls to the capital, and the occupation of positions that confers social weight determines and justifies the occupation of new positions, they are strengthened with all the weight of the group of their occupants (BOURDIEU, 2011, p.118/119).

In this way, we can understand that the field of Physical Education has been transforming, over the last few years, into a space of dispute for power built through non-epistemological strategies (they exist and correspond to an important capital20, but currently they are not decisively exclusive to autonomy and legitimation of the field). We perceive the existence of aegis in the search for the occupation of positions of influence captained by outside the field that caused social views on what it is to be a Physical Education teacher today.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Based on Pierre Bourdieu's reference, we reviewed the concept of field to understand the production of knowledge in Brazilian Physical Education. When delving deeper into the context of power struggles between agents and institutions, the analysis strategy was to show that Bourdieu is a theorist who provides important epistemological resources that underpin contemporary debates in Physical Education, especially in the relationship between training and professional performance.

In this sense, the use of the concept of field to think about the production of knowledge in Physical Education is based on the perspective of promoting the historical, social, economic, political, and symbolic understanding of it before the exercise of propositions that are often circumscribed in visions peculiar and detached from reality as a whole (or from the critical reading about everyday life that is impacted by general norms, which are often conditioning). The idea of creating tables on the position of agents in the field and briefly describing how institutions were forged helps to resize the analytical work on training policies in/in the field and to clarify many of the disputes in vogue.

Therefore, this article allows us to glimpse analytical alternatives that, perhaps, can help in the theoretical-methodological construction of new studies. Mainly those who intend to establish readings on the production of knowledge in Physical Education within the scope of academic-professional disputes and their identity. These alternatives must not be based on the linear construction of facts. Bourdieu was an author famous for intercommunicating concepts and establishing the constant exercise of epistemological surveillance. Consequently, when revisiting the concept of field, we weave its relations with other concepts such as capital, habitus, and power and align the need to reflect on the identity and epistemology of Physical Education.

We understand that there is no convergent identity on Physical Education in Brazil, nor a homogeneous epistemological matrix. The most expressive mark of this field is its constant tension and dispute between agents and institutions, mainly regarding the accumulation of symbolic capital and knowledge that should be in the learning orbit of individuals who seek a university education in Physical Education. Bracht (2000) reminds us that the contours of the academic field of Physical Education are defined by the struggle around what is its object, what is its conception of science, and which investigation problems are legitimate or not. For the author, the contours of the field are dynamic and cannot be defined rigidly, since “the very definition of its object is also an object of dispute” (p. 62).

This does not mean that there is not a minimum consensus that makes the existence of the field possible. According to Bracht (2000, p. 62) what makes it worthwhile to play the game is the certainty that “there is an agreement that within the field, voices are not heard that question the legitimacy of Physical Education or practices in the broad sense - the historical form of their concretization is criticized, but not the meaning of their existence”. In this way, we agree that Physical Education is a field, interconnected to other fields, which often reproduces pre-established laws and social paradigms in an uninterrupted attempt to constitute its relative autonomy. This allows us to agree with Fensterseifer (2006) when he announces that the epistemological activity of Physical Education in the 21st century has presented a mosaic character, that is, the epistemological production route is not necessarily inserted in HEIs, but also spaces of intense political circulation and social impact of the different agents.

From this reality, there is eminent danger to the fundamental concepts of Brazilian Physical Education permeated by relativism. When the field no longer uses criteria to define a legitimate vision, all visions are illegitimate (radical pluralism). It causes the appearance of uncertainty, in those who establish a position of criterion for judging the truth and how to deal with the pluralism of ideals without falling into the fragility of relativism (BRACHT, 2003). In this context, the agents mobilized around the political field gain permeability and become more powerful in the sense of directing the “identity” of the field, since our society is established by an organization of pro-market, pro-economy laws. and pro-profitability (BRACHT, 2003).

However, it is important to clarify that despite the power of influence, the political field alone does not have sufficient premises to support the "identity" of Physical Education, but as we showed earlier, the agents who organized within this logic are commanding powers that the remain influential. They can shape characteristics of a physical education that is bureaucratic, legalistic, and segmented as a commodity. This gradually tensions epistemologies of Physical Education constituted by principles of culture, education, and sociability.

It is essential to consider the particularities of the symbolic system that allowed the production and circulation of certain ideologies. They operate the ways of being, thinking, and acting of current Physical Education. For Bourdieu (2009, p. 14) ideologies come from the social conditions of their production and circulation, that is, they fulfill functions for those who built them and for those who will be taken by the process.

Consequently, the field of Physical Education and its objects of study are not exempt from the determinations of its macrocosm, that is, from the political, social, scientific, and economic fields, among others. The entire course that we present explains the interests of agents and institutions, historically interconnected to the very constitution/consolidation of the field (political, cultural, epistemological, and social). In the context of this article, we believe that the appreciation of the historical process is essential to unveil the multiple elements that intend this field, especially in its institutionalization and growth.

REFERENCES

A história do CBCE. http://www.cbce.org.br/historia.php Acesso em: 07/04/2019 [ Links ]

BACHELARD, Gaston.A filosofia do "não". São Paulo: Editora Abril, 1984. [ Links ]

BETTI, Mauro. Por uma teoria da prática. MotusCorporis, Rio de Janeiro, v. 3, n. 2, p. 73-127, 1996. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Homo academicus. Tradução de Ione Ribeiro Valle e Nilton Valle. Florianópolis: Editora da UFSC, 2011. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. (2009). O poder simbólico. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand Brasil. 322p. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Razões práticas: sobre a teoria da ação. 8. ed. Tradução de Mariza Corrêa. Campinas: Papirus, 2008. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. A economia das trocas simbólicas. 5. Ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 2004a. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Os usos sociais da ciência: por uma sociologia clínica do campo científico. Tradução de Denice Barbara Catani. São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2004b. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Coisas ditas. Tradução de Cássia R. da Silveira e Denise Moreno Pegorim. 1. reimp. da 1. ed. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 2004c. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. Questões de sociologia. Tradução de Miguel Serras Pereira. Lisboa: Fim de Século, 2003. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre e WACQUANT, Loïc. Una invitación a la sociología reflexiva. 1a ed. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores. Argentina, 2005. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, Pierre. The forms of capital. In: John G. Richardson (ed.), Handboodk of Theory and research for the Sociology of Education. Greenwood: New York, 1986. [ Links ]

BRACHT, Valter; et al. Educação Física Escolar como tema da produção de conhecimento nos periódicos da área no Brasil (1980-2010): parte I. Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 17, n. 02, p. 11-34, abr./jun. 2011. [ Links ]

BRACHT, Valter. Identidade e crise da educação física: um enfoque epistemológico. In: BRACHT, V.; CRISÓRIO, R. (Org.). A educação física no Brasil e na Argentina: Campinas: Autores Associados, 2003. [ Links ]

BRACHT, Valter. Educação Física & ciência: cenas de um casamento (in) feliz. 2. ed. Ijuí: Ed. Unijuí, 2000. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 23 dez. 1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Parecer N. CNE/CES 0058/2004, de 18 de fevereiro de 2004, do Conselho Federal de Educação. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Educação Física. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Parecer N. CNE/CES 0138/2002, de 25 de abril de 2002, do Conselho Federal de Educação. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Educação Física. [ Links ]

CHAVES, Márcia; GAMBOA, Silvio Sánchez; TAFFAREL, Celi. A pesquisa em educação física no Nordeste brasileiro (Alagoas, Bahia, Pernambuco e Sergipe), 1982-2004: balanço e perspectivas. Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte, Campinas, v. 29, n.1, p. 89-106, set. 2007. [ Links ]

CONFEF, 2018. História da regulamentação da Educação física no Brasil. Elaboração de medidas legais e a criação de um conselho. Disponível em: < Disponível em: http://www.confef.org.br/história . > Acesso em: 20/04/2019 [ Links ]

CONFEF. (2019). Estatuto del Consejo Federal de Educación Física - CONFEF. Publicado en Diario Oficial. Nº. 237, Sección 1, p. 137 a 143, 13/12/2010. Recuperado de: <https://www.confef.org.br/confef/conteudo/471> [ Links ]

FENSTERSEIFER, Paulo E. Educação Física: atividade epistemológica e objetivismo. Filosofia e Educação: Revista Digital do Paidéia, Campinas, v. 2, n. 2, p. 99-110, out. 2010. [ Links ]

FENSTERSEIFER, Paulo E. Atividade epistemológica e educação física. In: NÓBREGA, T. P. (Org.). Epistemologia, saberes e práticas da educação física. João Pessoa, PB: Universitária/UFPB, 2006. [ Links ]

FENSTERSEIFER, Paulo E. Epistemologia e prática pedagógica. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Esporte, Campinas, v. 30, n. 3, p. 203-214, maio 2009. [ Links ]

FENSTERSEIFER, Paulo E. Linguagem, hermenêutica e atividade epistemológica na educação física. Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 15, n. 4, p. 243-256, out./dez. 2009. [ Links ]

FENSTERSEIFER, Paulo E. Conhecimento, epistemologia e intervenção. In: GOELLNER, Silvana Vilodre(Org.). Educação Física/ciências do esporte: intervenção e conhecimento. Florianópolis, 1999. p.171-183. [ Links ]

GAMBOA, Silvio S. Reações ao giro linguístico: o "giro ontológico", ou o resgate do real independente da consciência e da linguagem. In: Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências do Esporte/Congresso Internacional de ciências do esporte, 15. e 2., 2007, Recife. Anais. Recife. CONICE, CONBRACE, 2007. [ Links ]

HEY, Ana Paula. Poder Simbólico (Verbete). In: CATANI, Afrânio Mendes; et.al. (Orgs). Vocabulário Bourdieu. 1 ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica Editora, 2017. p.292-294. [ Links ]

INEP, Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Sinopse estatística da Educação Superior 2017. Brasília, 2018. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http:http://portal.inep.gov.br/web/guest/sinopses-estatisticas-da-educacao-superior >. Acesso em: 03/04/2020. [ Links ]

JOURDAIN, Anne & NAULIN, Sidonie. A teoria de Pierre Bourdieu e seus usos sociológicos. Traduzido de Francisco Morás. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2017. [ Links ]

LAHIRE, Bernard. Os limites do conceito de campo. In: Souza, Jesse; Bittlingmayer, Uwe (coord.). Dossier Pierre Bourdieu. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2017. p. 11-28. [ Links ]

LAZZAROTTI FILHO, Ari. O modus operanti do Campo acadêmico-científico da Educação Física no Brasil. Tese (Doutorado em Educação Física). Santa Catarina: Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação Física, 2011. [ Links ]

LAZZAROTTI FILHO, Ari; et al. Transformações contemporâneas do Campo acadêmico-científico da Educação Física no Brasil: novos habitus, modus operandi e objetos de disputa. Revista Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 20, n. esp., p. 67-80, 2014. [ Links ]

MARTINEZ, Flávia Wegrzyn; CAMPOS, Jeferson de. A sociologia de Pierre Bourdieu. Revista eletrônica da feati, - nº 11- p. 1-15, julho/2015- ISSN 2179-1880. [ Links ]

NOZAKI, Hajime Takeuchi. Mundo do trabalho, formação de professores e conselhos profissionais. In: FIGUEIREDO, Zenólla Christina Campos (Org). Formação profissional em Educação Física e mundo do trabalho. Vitória: Gráfica da Faculdade Salesiano, 2005. p.11-30. [ Links ]

NOZAKI, Hajime Takeuchi. Educação Física e Reordenamento no Mundo do Trabalho: mediações da regulamentação da profissão. Niterói: Universidade Federal Fluminense, 2004. (Tese Doutorado em Educação), [ Links ]

PAIVA, Fernanda S. L. Constituição do campo da EF no Brasil: ponderações acerca de sua especificidade e autonomia. In: BRACHT, V.; CRISÓRIO, R. (Coord.). A EF no Brasil e na Argentina: identidade, desafios e perspectivas. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2014. p. 63-79. [ Links ]

PAIVA, Fernanda S. L. Notas para pensar a EF a partir do conceito de campo. Perspectiva, Florianópolis, v. 22, p. 51-82, jul./dez. 2004. n. especial. [ Links ]

PAIVA, Fernanda S. L. Ciência e poder simbólico no Colégio Brasileiro de Ciências do Esporte. Vitória: CEFD/UFES, 1994. v. 1. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, Elaine Aparecida Teixeira. O conceito de campo de Pierre Bourdieu: possibilidade de análise para pesquisas em história da educação brasileira. Revista Linhas. Florianópolis, v. 16, n. 32, p. 337 - 356, set./dez. 2015. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Iury. Formação em Educação Física no Brasil: novas orientações legais, outras identidades profissionais? Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Educação da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Goiás. Goiânia, 2016. [ Links ]

SAPIRO, Gisèle. Conhecimento praxiológico (Verbete). In: CATANI, Afrânio Mendes; et.al. (Orgs). Vocabulário Bourdieu. 1 ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica Editora, 2017. p.126-128. [ Links ]

SARTORI, Sérgio. Associações de Professores de Educação Física - APEF. In: DACOSTA, Lamartine (Org.). Atlas do Esporte no Brasil. Rio De Janeiro: CONFEF, 2006. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://www.atlasesportebrasil.org.br/textos/138.pdf . Acesso em 15 de abril de 2020. [ Links ]

SOUZA E SILVA, Rossana V. Pesquisa em educação física: determinações históricas e implicações epistemológicas. 1997. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal de Campinas, Campinas, 1997. [ Links ]

SOUZA NETO, Samuel de; et al. Conflitos e tensões nas Diretrizes Curriculares da Educação Física: o campo professional como espaço para lutas e disputas. Pensando a Prática, Goiânia, v. 19, n. 4, p. 734-746, out/dez. 2016. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Juliano de.; MARCHI JÚNIOR, Wanderley. Por uma sociologia da produção científica no campo acadêmico da Educação Física no Brasil. Motriz, Rio Claro, v. 17, p. 349-360, 2011. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Juliano de.; MARCHI JÚNIOR, Wanderley. Por uma sociologia reflexiva do esporte: considerações teórico-metodológicas a partir da obra de Pierre Bourdieu. Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 16, p. 293-315, 2010. [ Links ]

STIGGER, Marcos P.; et al. Revista Movimento: análise dos sentidos e da repercussão de um periódico que “se faz” no campo da Educação Física brasileira. Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 16, p. 113-154, 2010. n. especial. [ Links ]

TAFFAREL, Celi N. Z.; ALBUQUERQUE, Joelma O. Epistemologias e teorias do conhecimento em educação e educação física: reações aos pós-modernismos. Filosofia e Educação: Revista Digital do Paidéia, Campinas, v. 2, n. 2, p. 8-52, out. 2010. [ Links ]

THIRY-CHERQUES, Hermano R. Pierre Bourdieu: a teoria na prática. RAP, Rio de Janeiro, v. 40, 1, p. 27-55, jan./fev. 2006. [ Links ]

VAZ, Alexandre F. Metodologia da pesquisa em educação física: algumas questões esparsas. In: BRACHT, V.; CRISÓRIO, R. (Org.). A educação física no Brasil e na Argentina: identidade, desafios e perspectivas. Campinas: Autores Associados ; Rio de Janeiro: PROSUL, 2003. p. 115-127. [ Links ]

3When treating Brazilian Physical Education as a field of knowledge production full of interests, we start from the macro view of the field in its educational, political, academic and professional issues, to focus on the disputes in the axis of initial training policies between licentiate and baccalaureate, which was the central object of the doctoral thesis of one of the authors.

4According to Thiry-Cherques (2006) the epistemological surveillance proposed by Bourdieu comes from the philosophical matrix, the ethnological practice and his later dedication to sociology anchored to Gaston Bachelard's philosophy of science. Pierre Bourdieu, from Bachelard (1984) guides the idea that thought must be operated as a pincer movement, which discovers, integrates and overcomes the limitations of theories in an increasingly comprehensive conceptual composition.

5According to Thiry-Cherques (2006) “Economy and Society” is a book by political economist and sociologist Max Weber, published posthumously in Germany in 1922 by his wife Marianne. Along with the "Protestant Ethic" and the "Spirit of Capitalism", it is considered one of Weber's most important works.

6Bourdieu (2005) comments and criticizes numerous passages of his work, based on an interview conducted by Professor Loïc Wacquant, which aimed to expose Bourdieu to the full range of objections raised by different scholars at different points in his career.

7The concept of doxa replaces what Marxist theory calls “ideology” as “false consciousness”. Doxa is what all agents agree on. Bourdieu adopts the concept both in the Platonic form — the opposite of the scientifically established — and in the form of belief (which includes supposition, conjecture, and certainty). The doxa contemplates everything that is admitted as “just like that”: classification systems, what is interesting or not, what is demanded or not (THIRY-CHERQUES, 2006, p.37).

8The nomos brings together the general, invariant laws of the field's functioning. The evolution of societies gives rise to new fields, in a process of continued differentiation. Every field, as a historical product, has a distinct nomos. For example, the artistic field, established in the 19th century, had as its nomos: “art for art”. Both the doxa and the nomos are accepted, legitimized in the environment and by the social environment shaped by the field (THIRY-CHERQUES, 2006, p.37).

9Doctoral thesis entitled “Formação profissional em Educação Física: tensões curriculares entre licenciatura e bacharelado”.

10Perspectives as a way of being, acting and doing typical of the time that were configured in a hygienist, normative, moral and utilitarian social field in practices.

19According to the Higher Education Sense of 2017 (INEP, 2018) there were 296, two hundred and ninety-six, Public HEIs (13% of the total) and 2152, two thousand one hundred and fifty-two, Private HEIs (87% of the total) offering courses in the Brazil. Enrollments in public HEIs with a total of 2,045,356, two million forty-five thousand three hundred and fifty-six, (24% of the total) against 6,241,307, six million two hundred and forty-one thousand three hundred and seven, in private HEIs (76% of the total).