Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 02-Set-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469834877

ARTICLE

NOW, THE WORD OF THE CHILDREN! DISCURSIVE EXCHANGES DURING COLLABORATIVE WRITING ACTIVITIES IN CHILDHOOD EDUCATION

1Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (UFPE). Recife, PE, Brasil.

Literature points out that young children can construct a meaningful interaction with written texts and are interested to produce them (Mayrink-Sabinson, 1998; Rego, 1988; Souza, 2003). However, few studies investigate how children partake in situations in which texts are collaboratively produced, having the teacher as a transcriber. In this context, the present research analyzed the discursive exchanges between children aged 5 and 6 and their teachers, during group writing activities in two classes in the last year of kindergarten in two public schools. Based on a sociodiscursive approach to written language (Bronckart, 1999; Schneuwly, 2004), text production activities led by the teachers, were video-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed qualitatively. Data showed children’s active participation in producing different discursive genres, sharing in this process, knowledge, and reflections on different dimensions involved in textual production (i.e. genres characteristics, socio-interactive aspects, creation of textual content, the graphic signs used for writing, and the revision of writing). Teacher mediation, in a dialogical perspective and with interventions that drew children's attention to such dimensions, proved to be a key element in enhancing children's engagement in the activity and in promoting a co-authoring experience in the writing of texts. We concluded that discursive exchanges, mediated by teachers during group writing activities, can stimulate significant learning situations shared among children.

Keywords: Childhood Education; written language; group writing

A literatura indica que crianças pequenas podem estabelecer uma interação significativa com textos escritos e demonstrar interesse em produzi-los (Mayrink-Sabinson, 1998; Rego, 1988; Souza, 2003). Entretanto, são escassos os estudos que investigam as formas de participação das crianças nas situações em que textos são escritos de forma colaborativa, tendo a professora como escriba. Nesse contexto, analisamos, na presente pesquisa, as trocas discursivas entre crianças com 5 e 6 anos e suas professoras durante atividades de produção coletiva de textos em duas turmas do último ano da Educação Infantil de instituições públicas. Partindo de uma abordagem sociodiscursiva da linguagem escrita (Bronckart, 1999; Schneuwly, 2004), três produções coletivas conduzidas por cada professora foram videogravadas, transcritas e analisadas qualitativamente. Os dados evidenciaram a participação ativa das crianças na produção de diferentes gêneros discursivos, compartilhando, nesse processo, conhecimentos e reflexões sobre diferentes dimensões envolvidas numa produção textual (i.e., características do gênero, aspectos sociointerativos, geração do conteúdo textual, os sinais gráficos utilizados para escrever e a revisão da escrita). A mediação docente, numa perspectiva dialógica e com intervenções que chamavam a atenção para tais dimensões, mostrou-se um elemento-chave para potencializar o engajamento das crianças na atividade e para a promoção de uma experiência de coautoria na escrita dos textos. Concluímos que as trocas discursivas, mediadas pelas professoras durante a produção coletiva de textos, podem proporcionar situações de aprendizagens significativas, compartilhadas entre as crianças.

Palavras-chave: Educação Infantil; linguagem escrita; texto coletivo

La literatura indica que los niños pequeños pueden establecer una interacción significativa con los textos escritos y demostrar interés en producirlos (Rego, 1988; Mayrink-Sabinson, 1998; Souza, 2003). Sin embargo, hay pocos estudios que investiguen las formas de participación de los niños en situaciones en las que los textos se escriben en colaboración, donde la profesora es escriba. En este contexto, la presente investigación analizó los intercambios discursivos entre los niños de 5 y 6 años y sus profesoras durante las actividades de producción de textos en dos clases del último año de Educación Infantil en instituciones públicas. Sobre la base de un enfoque sociodiscursivo del lenguaje escrito (Bronckart, 1999; Schneuwly, 2004) tres producciones colectivas, conducidas por cada profesora, fueron videograbadas, transcriptas y analizadas cualitativamente. Los datos mostraron la participación activa de los niños en la producción de diferentes géneros discursivos, compartiendo en este proceso, conocimientos y reflexiones sobre las diferentes dimensiones que intervienen en una producción textual (es decir, características de género, aspectos socio-interactivos, generación del contenido textual, signos gráficos utilizados para la escritura y la revisión de la escritura). La mediación docente, en una perspectiva dialógica y con intervenciones que llaman la atención a esas dimensiones, se mostró un elemento clave para el compromiso de los niños en la actividad y para la promoción de una experiencia de coautoría en la escritura de los textos. Concluimos que los intercambios discursivos, mediados por la profesora durante la producción colectiva de textos, pueden proporcionar situaciones de aprendizaje significativas, compartidas entre los niños.

Palabras clave: Educación Infantil; lenguaje escrito; texto colectivo

INTRODUCTION

When we talk about writing in Early Childhood Education, we do not always think about writing texts or even meaningful words such as children's names. In common sense and, unfortunately, in many educational institutions, writing is often associated either with tracing isolated letters and syllables or with copying words and even long headings (see, for example, data from research by Silva, 2018 and Souza, 2011).

However, we understand that in this first stage of education, it is essential to promote experiences that lead children to reflect on why we write, what we can write, and how we can do it. This means that, alongside significant learning aimed at the appropriation of the alphabetic writing system, such as knowing and spelling some letters and words of interest to them or building the notion that we spell the sound segments of the words we pronounce, children can be stimulated to understand in which situations we write texts and for what purpose. Thus, from an early age, we consider it important to learn that we write something to be read by someone with the intention of thanking, complaining, asking, congratulating, warning, expressing feelings of joy or sadness, or even not forgetting something important, among so many other reasons.

In the beginning, when children start writing they can make repeated horizontal lines, zigzag lines, a sequence of polka dots, or other marks similar to letters. Later on, they learn to spell some conventional letters, usually starting with the letters of their names, that is, starting from a word with a high meaning, which makes its written form easy to memorize. In this process, children also come into contact with the socio-interactive dimension of language, thinking, and building hypotheses about the different situations in which writing makes sense.

In summary, despite the uninspiring picture revealed by the research mentioned above, we believe that in Early Childhood Education, it is possible to promote significant experiences with written language. By doing so, we will be contributing to the development of young children's desire to learn to read and write, something that we consider fundamental at this stage.

Since the 1980s, the Psychogenesis of Written Language has shown that very young children already reveal an active, curious, and reflective attitude towards written language. Ferreiro (2001, 2011) and Ferreiro and Teberosky (1999) indicated that children build and test hypotheses about writing, covering a long way of discovering this representation system. Theories and studies in the field of literacy have also indicated that very young children are already capable of expressing knowledge about different written materials, their purposes, their recipients, and the characteristics of discursive genres (see, for example, Mayrink-Sabinson, 1998; Solé, 2004). Rego (1988), when observing the path of a child in the process of building knowledge about writing from 4 to 7 years old, concluded that intense exposure to reading stories was a fundamental element for the child to appropriate the characteristic marks of written language, even before knowing how to conventionally write the texts he created on the oral level. Terzi (1995), in his research with children from “poorly literate backgrounds”, also highlighted the influence of participation in literacy events, which take place both in the family environment and in preschool, on the development of reading in the following years.

More recently, studies that focused on reading and writing practices in Early Childhood Education have deepened the relationships between children and their process of appropriation of written language and reflected on the role of the educational institution in learning related to this field. The article published by Baptista et al. (2018) shows part of the results of a research that aimed to map the state of knowledge about reading and writing in Early Childhood Education in Brazilian academic production between 1973 and 2013. The authors organized the results of their analyzes into three periods, highlighting trends of research on that topic in each of them. In the first period (from 1973 to 1989), studies were scarcer, and the works published, especially in the 1970s, were anchored in a compensatory conception of preschool education. In the second interstice analyzed by the authors (the 1990s), there was an increase in production and also an expansion of research topics, probably in an attempt to respond to the multiple demands resulting from a reconceptualization of the child as an active subject with rights. Finally, in the last analyzed period (2000 to 2013), the authors found a greater frequency and regularity in the publications. Therefore, we conclude that reading and writing practices developed with young children have become an object of interest for scientific research, and this has helped to build some references for pedagogical work. However, new questions have emerged, and, in this sense, we understand that the interactions between children in events of collective writing of texts represent a theme that deserves to be more discussed with the teachers and more focused in the scope of the research. Next, we will discuss some notes already available in the literature about this topic.

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT TEXT PRODUCING WITH YOUNG CHILDREN?

In Early Childhood Education, there are numerous opportunities for children to experience meaningful writing situations. Thus, some authors (e.g., Gerde, Bingham & Wasik, 2012; Quinn, Gerde & Bingham, 2016; Rowe & Flushman, 2013) give important recommendations for developing good writing practices with children in the final years of kindergarten. Gerde et al. (2012), for example, recommend that writing opportunities be created in children's daily routine, so that writing is not something that only happens sporadically; they reinforce that all types of writing produced by children must be accepted by the teacher - from scribbles with drawings or shapes that only look like letters. Another recommendation from the authors is to always keep pencils and paper handy when organizing make-believe play environments, such as an office, a supermarket, or other settings where writing may be necessary. In this way, it is expected that children can integrate writing into the plots of their games and discover while playing, alternatives for their use.

In line with what we have already stated, one of the fundamental indications of Gerde, Bingham, and Wasik (2012) and Rowe and Flushman (2013) is to engage children in writing proposals motivated by authentic and socially significant reasons, signaling that we can communicate ideas and information through writing. According to the authors, children may be asked to write their name on the list of who wants to use the computer in the room, or on a work of art, they have done, or to write a thank-you card to the owner of the local bakery for the visit they have made to their workspace (Gerde Bingham & Wasik, 2012).

In addition to individual writing situations, Gerde et al. (2012) and Rowe and Flushman (2013) also recommend the participation of children in writing experiences in small groups, because,“In making writing public as part of group process, children can observe what other children are thinking. It also allows children to understand the importance that print plays in documenting what they said so they can revisit their ideas and reflect on their thoughts.” (Gerde, Bingham & Wasik, 2012, p. 6).

Therefore, the authors emphasize the need to create situations in which the little ones “share the pen” and write with their handwriting, maintaining physical proximity between them, at the same time that there is close monitoring of the teacher, with invitations to write and interventions addressed to the interests and needs of each one during the writing process.

Other authors (Girão & Brandão, 2014; Leal, Brandão & Albuquerque, 2021; Lerner, 2002; Teberosky & Ribera, 2004) have also valued the potential of collective writing when the teacher is the scribe of the group. In these cases, she assumes a triple role: she is a scribe, mediator, and co-author in her interaction with children; and, as Girão and Brandão (2014) point out, her role is not simply to write a text dictated by the little ones. She has the challenge of mediating the production of an oral text with a written destination that meets a clear and meaningful purpose for children.

Therefore, the teacher needs to make the writing process more transparent, which means saying aloud what she is thinking while writing. She can, for example, explain what she needs to clarify in the writing of a passage of the text or that it is necessary to give more information, or even that she is in doubt about what would be the best word to use. Of course, this entire intervention process also needs to take into account the purpose of the text, who it is intended for, as well as the characteristics of the discursive genre being produced (Schneuwly, 2004).

With this proposal of collective production, the expectation is that children expand their knowledge about written language, especially about why and in what situations we write texts and about what aspects we need to think about when we express in this way.

Studies that investigated the processes and practices of textual production with children who still do not read and write conventionally are scarce in Brazilian and international literature (see the research by Gerde & Bingham, 2012; Gerde, Bingham et al., 2015). In Brazil, in a survey carried out on the website of the National Bank of Dissertations and Theses, it was found that in the last ten years only three works (Costa, 2012; Girão, 2011; Zapelini, 2016) specifically discussed the topic of writing texts by children under 6 years old.

The study by Costa (2012) analyzed the records produced individually by children between 4 and 5 years old in situations in which the teacher requested the written production of a certain discursive genre (for example, an invitation, a message, or a list). Zapelini's research (2016) also analyzed the individual productions of children in the same age group, from the perspective of French Discourse Analysis. The children were asked to write on their initiative and, later, in situations proposed by the teacher. The research by Girão (2011), which also involved children between 4 and 5 years old, focused on the situation of collective production of texts mediated by the teacher. The author identified 11 different types of teaching intervention during the collective writing of texts to explain and reflect on the possibilities of mediation in this type of activity. The research data also indicated the existence of a relationship between the situation of textual production, the genre being produced, and the types and frequency of the teachers' interventions.1For example, in the production of an invitation, Girão (2011) observed a greater frequency of interventions by the teacher that promoted children's reflection on the components of the textual genre, such as conversations about the event that motivated the writing of the invitation, the date planned to be held, the location of the event and who would be invited. The author interpreted that the emergence of interventions of this nature was facilitated, probably because, in the case of an invitation, these textual components are well marked, in the form of topics.

If studies that deal with the mediation of the teacher in the activity of producing collective texts in Early Childhood Education are rare, we did not find, in the survey carried out, research aimed at analyzing the forms of children's participation during this activity. Considering that the entire process of collective writing is permeated by discursive exchanges about what to say and how to say it, we were interested in “focusing on the children's words2”, as indicated in the article's title. We call discursive exchanges the interactions between children and between them and the teacher, in the work of elaboration and re-elaboration of the discourse that is constructed during the process of production of the written text. Thus, we start from the principle that when producing the text collectively, the group talks about ideas, ways of writing, the components of the genre, creates expectations about its interlocutors, checks if they are achieving their purpose, negotiates the use of terms, makes decisions, makes choices... in short, it engages in a network of orally shared utterances, situated in a certain socio-communicative context, which will have the written text as a product.

With this intention, we qualitatively analyzed the exchanges between the group during the collective construction of texts, seeking to answer the following questions: (1) how do young children participate in the process of collective writing of texts?; (2) what knowledge about written language is revealed by them during the discursive exchanges that emerge in the process of textual production? and (3) what conditions could favor such discursive exchanges in the collective writing activity?

To address these issues, we will initially make some more general theoretical considerations on the topic of text production and then present the research data. In this direction, we will identify and exemplify, at first, the different forms of children's participation evidenced during the collective writing process. Then, to deepen the analysis of the nature of the observed discursive exchanges and the knowledge shared between them about written language, we will discuss two situations of collective production in which boys and girls are more engaged in this activity.

REFLECTING ON THE PRODUCTION SITUATION OF A WRITTEN TEXT

In the model of textual production proposed by Schneuwly (2004), when the person is faced with the need to produce a text, he/she ends up adopting a certain genre that, for him/her, best suits the specific situation of social interaction on which he/she is acting. To make this choice, we rely on certain schemes that correspond to the construction of the orientation base and to the operations of text management and linearization.

The orientation base is a set of internal representations created by the subject from the context of interaction. These representations of the situation of social interaction take into account aspects such as the social place occupied by the person, the moment and place in which the text is produced, the objectives set for writing the text, and its relationship with the interlocutors. These representations, which guide the discursive action, can change according to the needs of the communicative situation and, in this way, control the other operations involved in the textual production, that is, the text management and the linearization process.

In Schneuwly's (2004) model of textual production, the textual management process occurs through anchoring and planning operations, which can be used simultaneously. Anchoring is the central and initial form of text management, in which the individual activates the representations that define what is going to be said and how it is going to be said. Through this operation, the individual anchors the writing activity in the set of constructed representations. Planning involves activating, organizing, and sequencing the contents and also their linguistic structuring, adapted to a language model or text plan, chosen according to social interaction.

Finally, the linearization operation concerns the processes of materialization of content into linguistic units, that is, referentialization and textualization. Referencing is about creating minimal initial language structures. This operation involves the choice of terms and does not allow the production of a statement directly, but a “scheme that generates statements” (Culioli, 1976, p. 91). On the other hand, textualization acts at the local level of textual chaining and includes ways of establishing hierarchical articulations of the text, such as cohesion, connection/segmentation, and modalization.

Bronckart (1999) highlighted the specificity of text writing situations. For the author, the conditions of textual production are defined by physical, social, and subjective parameters, such as the place and time in which the text is produced, the position of the author and his interlocutor, as well as the purpose of the text. Thus,

it is unlikely that there is an ideal and advisable “writing process”, and writing is conceived in a flexible, dynamic, and diversified way, depending on the different situations that give origin and meaning to the task of writing. This means understanding that the writing process, carried out by an author, is only interpretable in a given context. Each scenario draws a plot of specific conditions and suggests to the author a different way of acting (Castelló, 2002, p. 149, [our translation]).

Based on these considerations, we can say that the collective writing of a text involves two situations of interaction that develop in parallel: the utterances produced by the group that is writing towards the recipient(s) of the text, in a movement that goes towards the outside the writing activity, and the utterances that are built internally in the interlocution that the group establishes among themselves to structure the discourse that will be recorded in the written plan. It is these two enunciative movements (external and internal) that we seek to present in the analysis of the situations of collective writing observed.

INTERACTIONS AS THE BASE OF APPROPRIATION OF CULTURE WRITTEN BY SMALL CHILDREN

As an artifact of culture, written language permeates social relations in a graph-centric society like ours. Therefore, the appropriation of this cultural object, in its discursive dimension, does not occur spontaneously, but through the interaction between individuals who share situations in which its use is necessary.

Considering that interactions constitute one of the structuring axes of pedagogical work in Early Childhood Education (Brasil, 2010), situations of collective writing of texts can present us with important elements about how children act and react in the face of the challenge of communicating with someone in writing. Having discursive exchanges as a keynote of the process of building a text, collective production can help us to understand aspects related to the perspective of children at the beginning of these learning processes.

Thinking about the relationship between children and written culture leads us to dialogue with Vygotsky in his description of the process of internalization of higher psychological functions. This process takes place from the interpersonal level to the intrapersonal level (Vygotsky, 2007). This movement, which takes place first between people and, later, within the child, indicates that the “other” has a fundamental role in learning. In this context, by sharing the writing of a text to meet a real need with their peers and an adult, children have the opportunity to think about language with the mediation of the other. In this way, they can explain what they think about the different events mediated by writing, which representations they build about their interlocutors, and relate the context of writing with other situations experienced outside of school, among other exchanges that slide discursively and that go concretizing the authorship of the text produced by the group. From this perspective, the interactions that the group establishes are statements, and every statement is inherently dialogic since it is part of an uninterrupted discursive chain (Bakhtin, 1997).

Based on the theoretical foundations presented so far, we are interested in better understanding how children react when immersed in the discursive exchanges that are established during the collective writing of texts. What aspects of written language catch your attention? What meanings do they attribute to writing when they are invited to write for someone? What aspects of mediation seem to help in the flow of interactions and the construction of a guideline for writing and the other operations involved in this process? Such issues will be discussed in the following sections, having as references both the model of textual production presented above and the specificities of pedagogical work with young children.

THE PROPOSED COLLECTIVE WRITING SITUATIONS AND THE PARTICIPATION OF CHILDREN

Children aged between 5 and 6 years old from two classes of the last year of Early Childhood Education at two institutions of the Municipal Network of Recife and their respective teachers participated in the research. Three collective productions, conducted by each group, were videotaped and transcribed. The present study sought to observe ethically informed research practices, dialoguing with the teachers and the children's families about the research procedures, as well as requesting permission for the subjects to participate through the Informed Consent Form (ICF).

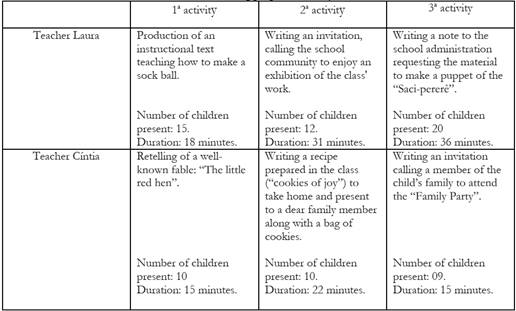

Box 1 shows the three situations of textual production that were proposed by each of the educators (here called Laura and Cíntia), the duration of each textual production activity, and the number of participating children.

In the case of teacher Laura, before proposing the first activity (writing an instructional text), she made sock balls with the children and then suggested that the group write a text that teaches how to make the toy. The proposal had a clear purpose for the children; however, it was not defined who would be the interlocutors of the text produced. In teacher Cíntia's group, the first writing proposal was more associated with a communicative situation in the school sphere: rewriting of a fable known to children. The teacher also did not explain whether there would be other recipients for the text beside the children, who already knew the story well.

However, as we can see in Box 1, in the second and third activities, the teachers proposed writing situations that had a clearer socio-communicative context, which certainly made the writing activity more meaningful for the children, since there were a more defined purpose and recipients that were shared with the entire group. It is worth noting that even in the first writing proposals, the children from both groups were very interested in contributing to the production of the texts. This shows that the involvement of the little ones seems to be related not only to the immediate context in which the activities are carried out but also to the strategies used by the teachers to encourage their participation during the writing of the text and the activities that preceded this proposal (in this case, the making of the sock ball and the various moments of reading the fable, which was very much appreciated by the children).

Regarding the ways of organizing the group during the proposed writing activities, the two teachers followed different procedures. Teacher Laura wrote while standing on the whiteboard that was on the wall above the height of the children, who were seated on the floor or in small chairs, making a semicircle in front of the board. Teacher Cíntia, on two occasions, wrote on a large white paper, sitting on the floor and very close to the children, who were freely distributed around her. In the third writing activity, Cíntia wrote on a whiteboard positioned at the children's height, and everyone, including herself, sat in the small chairs next to the board. We observed that the organization proposed by Cíntia helped to create a relationship of greater proximity and interaction between the group, which could move more freely to point out letters and words recorded on the board or paper.

In the next section, we will deeply discuss the children's participation in collective writing activities, analyze their speech in the interactions established between the group (teacher and children), and explore their relationship with the knowledge about written language involved in the different situations of textual production.

MODES OF CHILDREN'S PARTICIPATION DURING THE JOINT PRODUCTION OF TEXTS

As we have already announced, in this article we will focus on the children's speeches, but they will be analyzed in the flow of the group's talks, having as a guideline the verbal interaction and its dialogical dimension (Bakhtin, 1997). The comments of children and teachers were categorized from the perspective of Content Analysis (Bardin, 2002); and the analysis performed here did not intend to quantify speech turns, but to approach them qualitatively. Therefore, in order to define the children's degree of participation during the activities, we considered the extension and the alternation of the shifts (longer or shorter shifts, predominance of the teacher's speech or of a specific child and greater alternation between the participants).

The analysis of children's participation in the six productions observed also pointed to some more general questions:

In some text productions, “chorus speeches” predominated, which are those in which the whole group or a good part of it speaks at the same time, usually responding to a generic question asked by the teacher, such as:

“Teacher - We did the sock ball activity here in the classroom, didn't we? Yes or no? Children - Yes”.In others, there was a better balance between “chorus speeches” and individual participation. In these cases, we observed that the children expressed more autonomy, speaking freely about what they thought, not only responding to the educator's requests but also asking questions and addressing other colleagues;

We also observed situations in which there was a greater alternation between the speech shifts of teachers and children, and in which the latter participated more frequently.

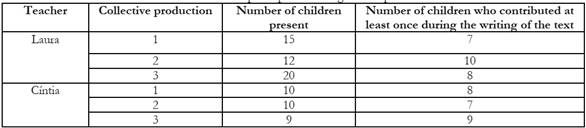

Considering the aspects mentioned above, we can say that the collective productions conductedby teacher Cíntia, in general, provided greater participation of the children, both in relation to the alternation of shifts and in terms of children's autonomy in speech and in the diversity of children who contributed to the writing. The data in Box 2 reinforce our assessment:

Analyzing the interactions qualitatively, we can infer that some factors contributed to the more intense participation of the children in teacher Cíntia's group. They are: the spatial organization of children, as we mentioned earlier; the smaller number of children participating and the teacher’s mediation style (which tended to produce shorter and more reflective speech turns than Laura. She generally returned questions to the children and directed her questions to specific children, requesting individual participation). We believe that these factors helped to build a more open and favorable climate for children to express themselves. However, we noticed that these ways of children's participation also fluctuated in the three activities proposed by the same teacher, something that may be related to the situations of text production, as we will discuss below.

Considering the dimensions of the textual production process - the generation of textual content, the textualization, the compositional form of the discursive genre, the textual review, and the alphabetic writing system -, the observation of the six collective productions indicated that the children of the two groups interacted with writing exploring these different dimensions.

Next, we will present examples extracted from the videos in which it is possible to verify this participation of children. Finally, as we have already announced, we will deepen the discussion on discursive exchanges approaching two of the six collective productions analyzed.

The process of generating textual content

The generation of textual content refers to the action of children to suggest ideas to compose the text. For example:

[...] Teacher: Let's go! So? What happened in this story?

Carla: The red hen was walking...

Calina: And along the way she found a grain of corn. [...]

(Fable retelling, collective production 1, Teacher Cíntia)

The teacher's question was asked at the beginning of the textual production. After Carla and Calina's speeches, other children in the group continued to describe the actions of the characters, which were written by the teacher. Throughout the process, the educator continued to encourage the explanation of the ideas to compose the text, through questions (for example, what did the hen do?), so that the final text reproduced the sequence of events in the original text that were recovered by the group.

Regarding this aspect, it is worth noting that the greater or lesser participation of children in the generation of content for the text seems to be related to the immediate context of production. Thus, in the case of the retelling of the fable of The little red hen, teacher Cíntia went so far as to say that the children were talking too fast for her to record it in writing. The fact that the story was well known to children was, therefore, a crucial element in enabling this greater participation. In this specific situation, the generation of textual content consisted in recovering the ideas of the original fable, that is, it was not a matter of generating new content for a text to be produced, something in principle more difficult for all of us. In summary, the children's more intense participation was certainly associated with the specific conditions of the situation of retelling a text that the group knew well.

An opposite movement, in terms of discursive exchanges, was observed in the collective writing of the note addressed to the school principals in teacher Laura's classroom. The note requested material to make a puppet. However, as the children did not know what would be necessary, the generation of ideas to compose the text focused on the figure of the teacher, and this was evidenced by the teacher's long turns of speech during the production of the text.

The textualization process

Textualization refers to the participation of children when they are called to reflect on the best way to write a certain part of the text, that is, to textualize. Let’s see an example in which the teacher and the children dialogue around this dimension:

[...] Teacher - Yes, but how can we start writing this note? Who needs this material?

Children - Us.

Teacher - So, how do we begin our note? Saying what? Saying how?

Clara - Please.

Teacher - PLEASE [writing].

José - Give me material.

Teacher - Give me material? What is the material? We have to say... Let's think more.

Milena - Please, give me some material.

Teacher - Please...

Milena - Give me some material.

Teacher - Give me?! But is it you who wants it or is it all of us?

Children - Us! [...]

Teacher - Let's keep asking, how do we ask?

quote>Milena - Give me.

Teacher - But is it “give me”? Is it you who wants it or is it all of us who need it?

Children - All of us. [...]

(Writing a note, collective production 3, Teacher Laura)

This excerpt shows how, based on the teacher's intervention on what would be the best way to start the note, the children tried to re-elaborate their speech, discussing the most appropriate way to write in that specific situation. One of the children suggested the insertion of the term please, which is a discursive modulator, perfectly suited to this writing situation. It is a linguistic resource that marks an special intention in the dialogue with the recipient of the text (in this case, the school principal), and such intention is delimited by the parameters of the interaction. In this context, Clara's suggestion made explicit in the written plan the group's purpose in producing the note: to make a request. Probably, based on her experiences with oral language, Clara suggested the inclusion of the modalizer because she knew that, in a situation where we make a request, the use of this resource could make the recipient of the text feel more inclined to grant what was asked.

Next, we see the conversation around José's speech, who suggested writing the phrase give me material. Milena seemed to agree with her colleagues' suggestion and continued repeating the same sentence to the teacher, adding only the word “some”: please, give me some material. The teacher questioned this formulation, asking if the text would be authored only by her or by the whole group. Therefore, we observe the movement of children, guided by the teacher, in an attempt to improve the text from the parameters of interaction (addressee, purpose, and authorship). This process illustrates a sociodiscursive conception of language, in which, through language, subjects are involved in a network of utterances, starting from existing utterances and, at the same time, projecting to others in the figure of their interlocutors (Bakhtin, 2006).

The compositional form of the textual genre

This topic is related to children's participation in the discussion about the components of the genre being produced. In the following excerpt, we can see that the children recognize a component of the invitation that had not yet been included in the writing: the author of the invitation, that is, the name of who invited. Let's see:

[...] Teacher - Are you finished? (after reading what had been written so far)

Children - Finished!

Teacher - Is there anything else missing?

Igor - We are missing that thing José said!

Teacher - What did José say? What was this thing? We put the text calling people, date, time and place. What did José say?

Igor - It was after this one, look! (pointing to the text).

Teacher - After this one, right? What is it? (pointing to the last word of the text: “place”)

(silence)

Teacher - The text calls people, date, time, and place. What's missing, José?

Igor - He forgot.

Teacher - Do you remember what was it?

José - I don't remember.

Teacher - It's something that if the person receives it and we don't put it on, they won't know who gave it to them. What is it missing?

Igor - The name!

Júlio - The name!

Teacher - We have to sign, right? So let's go! [...]

(Writing an invitation, collective production 2, Teacher Laura)

In the Bakhtinian definition, the compositional construction is one of the elements that constitute the genres of discourse, along with thematic content and style. Thus, these three elements “merge indissolubly into the whole of the utterance, and all of them are marked by the specificity of a sphere of communication” (Bakhtin, 1997, p. 280, author's emphasis). Given the great variety of discourse genres in a society like ours, we understand that the school is an important institution for the appropriation of literate culture. In fact, by analyzing the data from the present research, we found that, through interactions during collective writing, young children can internalize these relatively stable utterances that are genres of discourse, bringing us back to the internalization process described by Vygotsky (2007).

The children in teacher Cíntia's group also demonstrated that they knew the components of the invitation genre, explaining the information that needed to be included in the text to fulfill its purpose.

The textual review

In the text review process, we consider the moments when children participate in the text revision, during the writing process (in-process review), or in its final version (product review).

Let's see an example while writing the invitation to the Family Party in teacher Cintia's classroom, in which one of the children notices the repetition of a word and draws the group's attention:

[...] Teacher - WE INVITE ALL FAMILIES [reading]. What?

Letícia and Cláudia (talking at the same time): To the party!

Teacher - For what?

Letícia - Our party.

Teacher - TO OUR PARTY [writing].

Cláudia - of the family.

Letícia - There are two “families” there.

Teacher - Yes! Look, we are going to put “of the family”, but Letícia said that there will be two words for “family”. Do you need to put "family" again?

Children - No!

Teacher - ... If you already have family up there? What do you think?

Children - No! (in chorus)

Letícia - You don't have to [moving with her finger saying no]. [...]

(Writing an invitation, production 3, teacher Cíntia)

We see in the fragment above that Letícia pointed out the repetition of the word family without any signal from the teacher in this sense. It is possible that this understanding that in the written text we tend to avoid the repetition of words was built by her based on revisions suggested by the teacher, as occurred in the collective production of the cookie recipe, carried out previously. Thus, it seems that the teacher's reference as a model of someone more experienced with the activity of textual production helps children to begin to realize that the writing process is not linear, but consists of re-elaborations and refactorings.

Reflection on the alphabetic writing system

This category of participation refers to the children's comments related to the written notation during the production of the texts. Let's look at two examples:

[...] Raul - This is the “o” is it, miss? [pointing to the letter “o” in the word SANTOS]. [...]

(Production of the invitation, activity 3, Teacher Cíntia)

[...] Helena - The sock ball had a lot of letters! [looking at the text written on the board at the end of the activity].

Teacher - We wrote a lot of letters, Helena? Were there too many words for us to explain how you make the sock ball?

Helena - [shakes her head saying yes]. [...]

(Production of an instructional text, activity 1, Teacher Laura)

According to Kaderavek, Cabell, and Justice (2009, as quoted in Quinn et al., 2016), in Preschool, the teacher's role in mediating the child's attempts at writing can occur on three fronts: (1) informing children about the shape of the letters; (2) helping them to reflect on what letters would correspond to the sound segments of the words they pronounce and want to write; and (3) helping to generate ideas about the content of the text being written.

As it is possible to notice, the production of texts in a collaborative way allows exploring the last dimension of the teaching work pointed out by the authors. Thus, in the collective writing activity in which the teacher is a scribe, in general, the main intention is to lead children to reflect on sociodiscursive aspects (the purpose of the text, its content, recipient(s), and possibilities of textualization), and not on the functioning of the writing system4. Despite this, we saw above that the children pay attention not only to issues related to more general aspects of the written text but also seem to be curious and attentive to the symbols we use to write.

A similar observation was made by Girotto, Silva, and Magalhães (2018) when analyzing an episode of collective writing experienced by a group of children aged between 5 and 6 years old who attended a public institution in the countryside of São Paulo. The authors indicated that the children demonstrated to perceive specific marks of the genre that was being produced (it was a news item for the school newspaper) and, still, they highlighted the visual aspects of the text: observing the difference between “e” and “é” (in Portuguese “and” and “is”), one of the children explains that “if you don't put the accent, it becomes something else” (p. 168). Of course, we do not expect young children to understand the use of accents, but such comments indicate that they are, in fact, aware of the different dimensions of language.

In the next section, we will analyze, in more detail, two of the six productions that constituted the corpus of analysis of the research: productions 2 and 3 developed by teacher Cíntia and her group of children.

CHILDREN IN THE COLLECTIVE WRITING PROCESS: ENGAGEMENT IN ACTIVITY AND SHARED KNOWLEDGE IN DISCURSIVE EXCHANGES

The data presented in the previous section provide evidence of children's participation in the different operations that involve the production of a written text. However, we observed that, in the last two activities conducted with Cíntia's group, the children, in general, were more engaged in the writing activity, producing a greater alternation in the discursive exchanges, signaling a movement of more autonomy in the flow of interactions. In other words, in the two writing activities that will be discussed here, the children were not limited to just answering the questions and responding to the teacher's commands. They suggested and discussed the ideas that were raised, made their points of view explicit, and made decisions more independently.

In addition to a meaningful writing context for the children (purpose, genre, and addressees clearly presented), a second explanatory hypothesis for this broader participation of the little ones is the mediation style of teacher Cíntia. As we mentioned before, she conducted the activities of written production in a more dialogic way, questioning the children and stimulating their reflection.

These two conditions provided a more favorable space for discursive exchanges to be established and the co-authorship process to take on greater prominence among the children. We observed that teacher Cíntia's mediation was characterized by the use of proposing and problematizing language, by the teacher's availability to listen to the children, and by the openness to collective decision-making.

Next, we will discuss the data from the two selected activities, showing how teacher mediation favored discursive exchanges and the construction of knowledge by children.

The discursive exchanges during the discussion about the textual content

The analysis of teacher Cíntia's mediation, both in the production of the recipe (activity 2) and in the production of the invitation (activity 3), indicated that the conversation with the children, conducted by her, was constituted from a discursive dynamic in which she and the children´s speech were interspersed, not being recorded long turns of the educator's speech during the writing process.

In these two collective productions, Teacher Cintia used expressions such as: What do you think? Do you think it's better this way? What do you prefer? What do I put here? How do we place? Do you need anything else? Do you think this is important? By structuring the conversation in these terms, the teacher builds a more horizontal relationship with the children, so that they can recognize as authors of the text and realize that they can express their ideas, sharing them with the group. In summary, we observed that girls and boys, in general, were actively involved in the dialogue with the teacher, as the following excerpt illustrates:

[...] Teacher - Let's go! What will be the first thing we are going to put in this text?

Joana - We invite the family to the party.

Teacher - Wait. Slowly. WE INVITE [writing].

Children - The family to the party.

Teacher - We invite...

Joana - The family to the party.

Teacher - The family? What family?

Joana - The family... of the people.

Carla - Our family.

Teacher - Look at that,,.

Luna - To the whole family.

Teacher - ALL [writing]. What?

Joana - Just one family.

Teacher - Only one family? This invitation is for everyone.

Luana - All families.

Teacher - ALL FAMILIES [adds “IES” in the word FAMILY that was written]. FAMILIES [writing]. [...]

We can notice in the extract above how the teacher presents herself in the dialogue as a mediator and co-author, being a reference for the group, but, at the same time, questioning what the children said. Thus, she encouraged the children to think about what would be written to make the text clearer. In this direction, for example, the educator helped the little ones to reflect on the sociodiscursive aspects of the text (in this case, the recipients), in a process of re-elaboration of what was being said and that would then be recorded through writing.

We also noticed that the way the educator conducted the dialogue provided the children to engage in the discussion about the textual content. We highlighted in the previous section that the children actively participated in the operation of generating the textual content. However, in these two activities conducted by teacher Cíntia, we observed that the children not only contributed with ideas to compose the text, but became involved in the discussion about these ideas. This means that they presented suggestions and positioned themselves in the discursive exchanges, agreeing, disagreeing, and seeking the most appropriate content for the writing situation.

In the excerpt below, we can observe how, in the negotiations during the writing of the invitation, the children feel free to expose their ideas and discuss them. Thus, they take the floor, without waiting for the “authorization” of the teacher, who, in turn, balances herself in the complex role of mediator, scribe, and co-author:

[...] Teacher - What now? What do I put? And now what do I put here? After the time I put what?

Calina - The name of the school.

Carla - The location.

Teacher - How is it, Calina?

Carla - The location.

Teacher - LOCATION: [writing].

Joana - And the name of the school.

Calina - The location is not the name of the school?

Carla - No.

Teacher - Yes, it is. The location of the party... where will the party take place?

Children: At school.

Teacher - So, what am I going to put on the location?

Calina - The name.

Teacher - The name of what?

Calina - The school.

Teacher - So, Joana!

Calina - See, Carla!

Teacher - Carla was right, Calina. Here you will put the name of the school.

Joana - The time, miss. Micaela - But, she said that the location is not the name of the school.

Teacher - It's the name of the school because the party won't happen here at school?!

Calina - Carla said the name wasn't the place.

Teacher - The place… where will the party take place? Isn't it at our school, Carla?

Children - Yes.

Joana - That means that the place is already saying its name.

Teacher - That's it! We will put SCHOOL [writing].

Calina - See, Carla!

Joana - And Calina and I got it right! [...]

In line with the socio-interactionist perspective of language, we understand that, from these interactions, children can, little by little, build the notion that writing a text requires actions such as planning, selecting, organizing ideas, evaluating and revising the text, guided by an orientation base around the parameters of interaction in that specific situation (Bronckart, 1999; Schneuwly, 1988).

In the case of the invitation written collectively by the group of the teacher Cíntia, we emphasize that the fact that the educator took different copies of this genre to readwith the children and talk about their experiences with the situations in which an invitation is read or written, helped in the construction of the orientation base necessary for the production of the text.

Discursive exchanges in the textualization process

As we have previously mentioned, both in the collective production of the cookie recipe and in the production of the invitation, passages were recorded in which children and the teacher engaged in interesting conversations about ways of transposing the content of the text to the written plan, an operation called textualization in the model of textual production proposed by Schneuwly (1988). Intervening to stimulate this operation in collective production requires the teacher to be available to listen to the children. When we talk about listening, we are referring not only to the attitude of listening carefully to what they have to say, but to the responsive attitude towards what they say, respecting their contributions, and seeking to incorporate them into the text, as shown in the fragment below during the writingof the invitation:

[...] Carla - It's necessary to have the name.

Teacher - What name, Carla, do you think?

Calina - Of the date?

Teacher - Calina, let her speak.

Teacher - Carla, what name are you talking about?

Carla - The name of the date.

Teacher - Ah, she means the word date. That's it?

[Carla nods her head saying yes].

Teacher - Now I understand!

Calina - It is ugly! It is ugly, miss!

Carla - No, it isn´t.

Joanna - Yes, it is.

Carla - No, it isn´t.

Teacher - Let me get it. Can I get the invitation cards?

Children - Yes!

Teacher - Excuse me.

[At this point, the teacher leaves the room and goes to get one of the invitation cards she had brought the day before to show and talk to the children].

Teacher - Ready! Look here, I brought one. I brought one. Look that! Look that! Hey, Joana. “Invitation.Come to Zaza's christening.” Look here: “day, time, place” [reading the invitation and showing it to the children].

Carla - The date is missing.

Teacher - The day and the date is the same thing. We can put day or date. Is it ugly like this? Do you want like this?

Children - I want it! I want it!

Teacher - And then? What are you going to put here on the day of the party? Are you going to put the word date?

Joana - Yes.

Teacher -…or the word day?

Calina - Day, day, day!

Teacher - Will you put it on? Day or date?

Children - Day! Day! Day!

Teacher - DAY: 14 [writing]. [...]

In the fragment above, we see the speech of one of the children reminding us that the word “date” was missing from the invitation. Then, a conversation about this term began, which generated divergent opinions. To offer elements that would help in the decision, the teacher offered other examples of the genre, removing the centrality of her figure. The invitation read by her contained the word “day” and not “date”, and this generated a second question for the group: what would be the best way to record this idea? Note that the initial question raised by Calina was in the field of aesthetics (It's ugly!, It´s ugly, miss!) Although from a semantic point of view, this decision did not change the meaning of the text, the teacher did not miss the opportunity to stimulate discussion among the children.

Other moments of this nature were also recorded in the mediation of teacher Cíntia when, for example, she discussed with the children the best way to write the month (8 or August). This movement reveals that the group producing the text began to recognize the possibility of writing the same idea in different ways. Later on, this reflection can be extended to attempt to find the most appropriate way of saying it in functionof the objectives set for the text to be produced and the relationship with the interlocutors.

As indicated in the research by Girão (2011), discussing textual content and encouraging children's participation in the textualization process are interventions of a more complex nature and, therefore, more difficult for teachers to mobilize in the management of collective writing activity. However, teacher Cíntia showed that a reflexive and attentive mediation to the children's speeches could help them to engage in these operations and begin to reflect on them, even before being able to produce a written text in a conventional and autonomous way.

Discursive exchanges and collective decision-making

Producing a text requires making decisions throughout the writing process. A characteristic observed in the last two collective productions experienced by teacher Cíntia's group was the effective participation of children in the choices that gave materiality to the text. This aspect has already been evidenced in previous topics (when we talk about the discussion about textual content and the textualization process). However, we would like, once again, to highlight this “more horizontal” mode of interaction of Professor Cíntia, constantly inviting the group to think and decide together about what and how to write.

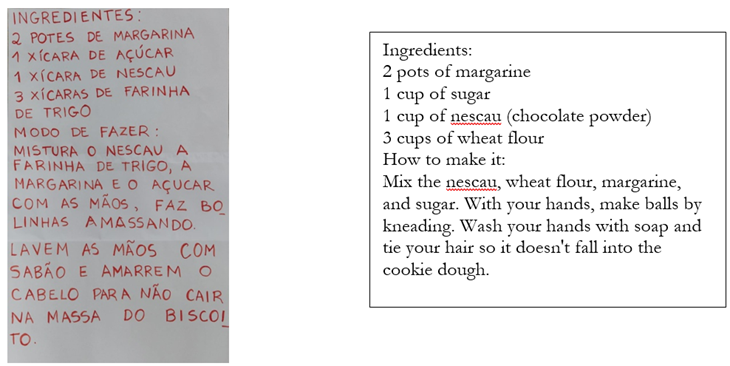

As we saw in Box 1, the second writing proposal launched by the educator was to write the recipe for “Joy Cookie” for the children to take the text home along with a bag of cookies. So, one day the teacher made the cookie with her class, and, the next day, the text was produced.

In the video in which the activity was recorded, the interest of the children was evident throughout the process, which involved a collaborative experience, mobilizing joint decision-making at various times, such as the name given to the cookie recipe, as we see in the dialogue below:

[...] Teacher - (...) yesterday we chose the name of the cookie.

Carla - It's happy cookie.

Teacher - Happy cookie? No...

Alisson - It's a cookie...

Joanna - Happy.

Teacher - It was.

Alisson - Happy Cookie.

Teacher - Cíntia asked for a suggestion to all the children in this room, see, Rafael? Didn't she, Alisson?

Alisson - Yes!

Teacher - I asked for a suggestion for the name of our cookie. Two suggestions came up: “happy cookie” and “joy cookie”. And then we voted, each child gave their opinion between “happy cookie” and “joy cookie”. Which onewon?

Juliana - Happy!

Calina - Joy!

Teacher - Joy! Joy cookie won. That's the name of our cookie! [...]

Besides the choice of the name for the cookies, the children also took part in other decisions: do you think it's important for us to put the recipe together with the cookie? We also highlight the moment when, at the end of the text, two girls suggest inserting a reminder for people to wash their hands and tie their hair up before preparing the cookies. Given this, the teacher launched the suggestion of the two for the group's approval and then continued in her role as scribe. Here's a snippet of that dialogue:

[...]

Carla - Because if you hold it with dirty hands...

Juliana - Hair will fall out...

Carla - Hair will fall into the food, and it will get dirty. And with dirty hands, the dough will get dirty.

Teacher - That's it! So, when we deliver this recipe, we'll remember to explain that we need to wash our hands well, right? And tie...?

Carla - The hair.

Teacher - Tie the hair up when making this recipe, because it can contaminate, which is dirty, contaminating is the same thing as dirtying...

Carla - Get the hair...

Luana - When the hair falls out it will get dirty. The food will get dirty. You have to wash your hands.

Teacher - That's it! Exactly. You have to wash your hands and tie your hair up, right? Do you want to put this here? Do you think it's important that we put here in our recipe that we should remember to wash our hands? Do you think it's important, Calina?

[Calina nods.]

Luana - Yes, if not, we will forget. [...]

It is also worth mentioning a reflection made on a question addressed by a child, during the written production of this recipe. Faced with a question asked by teacher Cíntia, the child looked at the teacher thoughtfully and asked: how can we say to you? The child's question draws attention to at least two aspects. The first is the recognition that the teacher is an important interlocutor in this collective writing process. She is a reference, someone more experienced with written language, who is available to listen and build the text together with the group. The second aspect is related to the reflexive and interactive character of the collective production of texts, that is, a situation in which there is someone for whom we need to explain the thought and re-elaborate the discourse according to a diversity of ideas that are presented. We understand that providing such an experience to children is, without a doubt, something fundamental in their process of discovery in the functioning of written language. In this regard, Bakhtin (2006) reinforces that

this orientation of the word in terms of the interlocutor is very important. In reality, every word has two faces. It is determined both by the fact that it comes from someone and by the fact that it is directed towards someone. It is precisely the product of the interaction between the speaker and the listener. Every word is an expression for one in the other. Through the word, I define myself as the other, that is, ultimately, about collectivity. The word is a kind of bridge thrown between myself and others (p. 115).

Therefore, by getting involved in discursive exchanges with their peers and with the educator, the children in teacher Cíntia's class began to internalize the idea that the process of writing a text requires decision-making by its authors and that, in the specific case of the collective text, these decisions need to be explained and agreed among the participants of the group.

Finally, the analysis presented here converges with the study carried out by Pascucci and Rossi (2005) about the role of the teacher, who goes beyond being a scribe, acting as a facilitator of children's discursive production and assuming the function of a reader to the extent that she asks the children to explain the information needed to understand the text. We can say, then, that the teacher acts as a link between what we call the internal and external movement of utterances during the collective production of texts. In the same way, we observed in the present study what Pascucci and Rossi highlight as children's agency. This means that each child is an “responsible agent of his/her own words, who participates in a human technology - language as discourse - within a small community of meanings, in which the teacher also participates” (Pascucci & Rossi, 2005, p. 185).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The examples presented and discussed here show that significant situations of collective production of texts in Early Childhood Education institutions can be good opportunities for children to build knowledge about different aspects of written culture.

The study data also show us that children can bring their previous experiences with the discursive genres produced, expose ideas, and agree and disagree on their initiative, which signals an active posture 5during the activities of collective production of texts analyzed here. As in life, we understand that knowledge about written production is mobilized by children in the educational institution in the context of its uses. In this way, the different dimensions of the text construction process, discussed above, were the children's learning objects as they interacted and shared the challenge of communicating with someone through writing. Therefore, it is not about “teaching a class on text production in Early Childhood Education”, presenting, for example, the characteristics of different discursive genres. On the contrary, the idea is to offer the little ones interesting and meaningful opportunities for them to express themselves in writing and have contact with the reading and production of different texts.

As we have already stated, some research has revealed the absence of proposals for the production of texts in Early Childhood Education (see, for example, Cabral, 2013; Gerde & Bingham, 2012; Silva, 2018; Souza, 2011). Perhaps this represents certain insecurity by the teachers to propose writing activities for children who have not yet been literate. This study highlightsthe mistake of this idea and presents elements so that we can better understand how the little ones participate in this type of proposal, helping to reflect on the possibilities of mediation between them and the written language.

Teacher Cíntia, especially in two of the three text production activities she proposed, showed that a more dialogic posture can favor more effective participation of children in the writing process. In addition, once reaching this higher level of participation, which we call here “engagement”, we saw that children can get involved in the co-authorship of texts, even contributing to the development of more complex operations related to the writing activity, such as the discussion about the content and the textualization.

The teacher's availability to listen to the children, welcome their ideas, problematize them and incorporate them into the text, encouraging the expression and listening of different opinions, and developing the skills to negotiate and make decisions, were also actions that proved to be essential for them to recognize each other in the text construction process.

During the collective production of texts, although the written notation may draw the children's attention, the recording of the text is carried out by the teacher. With this, it is expected that they will focus more on other dimensions of written culture, such as sociodiscursive aspects. Thus, both in situations in which children write by hand in the way they know and in those of collective writing, we found that the little ones build representations about the activity and seek to mobilize their knowledge to express themselves in writing, as we saw in our research.

We also saw that mediating the collective writing of a text with young children presents great challenges, such as guaranteeing everyone the space for speech and observing the reactions and engagement of children in the activity. In this sense, we can question the pertinence of forwarding collective writing with all the children in the class at the same time. Analyzing the six proposed activities and specifically observing the mediation of teacher Cíntia, who had fewer children in her group, we saw that she made use of interventions closer to each one. Thus, we ask ourselves: would the collective textual production conducted with a small group, which could be more interested in that writing situation, favor a more qualified mediation, also allowing a greater engagement of children? The data in Box 2 point in this direction, indicating a tendency towards an increase in participation when there are fewer children involved in the collective writing activity.

The studies mentioned here also converge on the idea that the production conditions interfere in the writing of texts and that “the other”, be it the mediator adult6 or the other interlocutors, “has a fundamental place in the children’s writing process, or that is, a huge influence on his saying” (Costa, 2013, p. 2012). We agree with this author when she states that skills related to the conventional notation of writing “are not requirements for the production of texts, but it is through the production of texts that children understand written language in its entirety: as a form and as a discourse”. (Costa, 2013, p. 31).

In summary, the research data show that discursive exchanges in a context in which the group effectively engages in the production of the text can create favorable conditions for the construction of knowledge related to writing, which constitutes an important basis in the process of developing readers and writers, which begins in Early Childhood Education. In this way, the collective production of texts can be a moment of encounter with the other in a significant experience of learning written language.

In conclusion, the analysis of the interactions between children and teachers when they collectively produce texts also shows that building a text from the relationship with the other is to assume the principle of collectivity, which presupposes the exercise of listening, respect, and acceptance, dimensions fundamentals of human formation.

REFERENCES

Bakhtin, M. (1997). Estética da criação verbal(2ª ed.). São Paulo: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Bakhtin, M. (V. N. Volóchinov) (2006). Marxismo e filosofia da linguagem: Problemas fundamentais do método sociológico da linguagem (12ª ed.). (M. Lahud & Y. Vieira, Trad.). São Paulo: Hucitec. (Obra original publicada em 1929). [ Links ]

Baptista, M. C., Neves, V. F. A., Corsino, P. & Nunes, M. F. R. (2018). A Produção acadêmica sobre leitura e escrita na educação infantil no período de 1973 a 2013: algumas reflexões. In L. D. Carvalho & V. F. A. Neves (Orgs.). Infâncias, crianças e educação: discussões contemporâneas. (Cap. 9, pp. 217-234). Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (2002). Análise de conteúdo(L. Antero Reto & A. Pinheiro, trads.). Lisboa: Edições 70. (Obra original publicada em 1977). [ Links ]

Brasil, Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Básica. (2010).Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação Infantil. Brasília: MEC/SEB. [ Links ]

Bronckart, J-P. (1999). Atividade de linguagem, textos e discursos: por um interacionismo sócio-discursivo. São Paulo: EDUC. [ Links ]

Cabral, A. C. dos S. P. (2013). Educação infantil: um estudo das relações entre diferentes práticas de ensino e conhecimentos das crianças sobre a notação alfabética (Tese de doutorado). Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, PE, Brasil. [ Links ]

Castelló, M. (2002). De la investigación sobre el proceso de composición a la enseñanza de la escritura. Revista signos, 35(51-52), 149-162. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-09342002005100011. [ Links ]

Costa, M. C. M. da. (2012). Práticas de produção de texto numa turma de cinco anos da educação infantil (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, ES, Brasil. [ Links ]

Costa, D. M. V. (2013). A escrita para o outro no processo de alfabetização (Tese de doutorado). Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, ES, Brasil. [ Links ]

Culioli, A. (1976). Transcription du séminaire de D.E.A. - 1975-1976. Paris: Université de Paris VII, D.R.L. [ Links ]

Ferreiro, E. (2001). Com todas as letras (9a ed). São Paulo: Cortez. [ Links ]

Ferreiro, E. (2011). Reflexões sobre alfabetização(26a ed) São Paulo: Editora Cortez. [ Links ]

Ferreiro, E. & Teberosky, A. (1999). Psicogênese da Língua Escrita. Porto Alegre: Ed. Artmed. [ Links ]

Girão, F. M. P. (2011). Produção coletiva de textos na Educação Infantil:a mediação e os saberes docentes. (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, PE, Brasil. [ Links ]

Girão, F. M. P. & Brandão. A. C. P. (2014). Produção coletiva de textos na educação infantil: o trabalho de mediação docente. Educação em revista, 30(3), 121-152. [ Links ]

Girotto, C. G. G. S., Silva, G. Ferreira da., & Magalhães, C. (2018). Freinet, Vigotsky e Bakhtin: uma aproximação possível ao acesso à cultura escrita. Revista Ibero-Americana de Estudos em Educação, Araraquara, v. 13, n. 1, p. 155-174, jan./mar. [ Links ]

Gerde, H. K., & Bingham, G. E. (2012). An examination of materials and interaction supports for children’s writing in preschool classrooms. Paper apresentado no Annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Reading. Montréal, Quebec. [ Links ]

Gerde, H. K., Bingham, G. E., & Wasik, B. A. (2012). Writing in early childhood Classrooms: Guidance for best practices. Early Childhood Education Journal. https://www.academia.edu/28295207/Writing_in_Early_Childhood_Classrooms_Guidance_for_Best_Practices. [ Links ]

Gerde, H. K., Bingham, G. E., & Pendergast, M. L. (2015). Reliability and validity of the Writing Resources and Interactions in Teaching Environments (WRITE) for preschool classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 31, 34-46. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.12.008. [ Links ]

Kaderavek, J. N., Cabell, S. Q., & Justice, L. M. (2009). Early writing and spelling development. In P.M. Rhymer (Ed.), Emergent literacy and language development: Promoting learning in early childhood (pp. 104-152). New York: Guilford. [ Links ]

Leal, T. F., Brandão, A. C. P., & Albuquerque, R. K. (2021). Condições de produção na escrita coletiva de textos: uma análise da mediação docente. Atos de Pesquisa em Educação, 16, e8148. doi:10.7867/1809-0354202116e8148. [ Links ]

Lerner, D. (2002). Ler e escrever na escola: o real, o possível e o necessário. Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Mayrink-Sabinson, M. L. T. (1998). Reflexões sobre o processo de aquisição da escrita. In R. Rojo (Org.). Alfabetização e letramento: perspectivas linguísticas. (1ª ed., pp. 87-119). Campinas: Mercado de Letras. [ Links ]

Pascucci, M., & Rossi, F. (2005). Professores e crianças nos discursos: a construção de textos escritos. In C. Pontecorvo, A. M. Ajello, & C. Zucchermaglio (Orgs.). Discutindo se aprende: interação social, conhecimento e escola. (Cap. 8, pp. 163-185). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Quinn, M. F., Gerde, Hope K., & Bingham, Gary E. (2016). Help me where I am: Scaffolding writing in preschool classrooms. The Reading Teacher, 70(3), 353-357. [ Links ]

Rego, L. L. B. (1988). Descobrindo a língua escrita antes de aprender a ler: algumas implicações pedagógicas. In Kato, M. (Org.).A concepção de escrita pela criança. Campinas: Ed. Pontes. [ Links ]

Rowe, D. W., & Flushman, T. R. (2013). Best practices in early writing instruction. In Barone, D. M., & Mallette, M. H. Best practices in early literacy instruction. New York, London: The Guilford Press, pp. 224-250. [ Links ]

Schneuwly, B. (1988). Les operations langagieres. In B. Schneuwly. Le language ecrit chez l’enfant.(Cap. 2, pp. 29-44), Paris: Delachaux & Niestle. [ Links ]

Schneuwly, B. (2004). Gêneros e tipos de discurso: considerações psicológicas e ontogenéticas. In R. Rojo, & G. S. Cordeiro(Orgs.). Gêneros orais e escritos na escola.(Cap. 1, pp. 21-39), Campinas, SP: Mercado de Letras. [ Links ]

Silva, T. T. da. (2018).O ensino da modalidade escrita da língua no final da Educação Infantil: concepções e práticas docentes (Tese de doutorado). Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, PE, Brasil. [ Links ]

Solé, I. (2004). Crónica de una involución: la educación infantil em la LOCE. Aula, Bercelona, nº 130, pp. 37-42, março. [ Links ]

Souza, L. V. (2003). As proezas das crianças em textos de opinião. Campinas: Mercado de Letras. [ Links ]

Souza, B. S. de A. (2011). As práticas de leitura e escrita: a transição da educação infantil para o primeiro ano do ensino fundamental (Dissertação de mestrado). Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, PE, Brasil. [ Links ]

Teberosky, A. & Ribera, N. (2004). Contextos de alfabetização na aula. In A. Teberosky, M. S. Gallart, et al. Contextos de alfabetização inicial. (Cap. 4, pp. 55-70). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [ Links ]

Terzi, S. B. (1995). A oralidade e a construção da leitura por crianças de meios iletrados. In Kleiman, A. B. (Org). Os significados do letramento: Uma nova perspectiva sobre a prática social da escrita. Campinas: Mercado de Letras, pp. 91-118. [ Links ]

Vygotsky, L. S. (2007). A Formação social da mente. São Paulo: Martins Fontes. [ Links ]

Zapelini, C. da S. M. (2016). A caminho da escrita: uma análise discursiva do processo de entremeio de produções escritas de crianças na Educação Infantil (Tese de Doutorado em Ciências da Linguagem). Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina, Tubarão, SC, Brasil. [ Links ]

1Similar conclusions were pointed out by Pascucci and Rossi (2005), in a study with Italian children of the same age group.

2The children's word is taken here both in the lexical and discursive sense, that is, the investigation turned to the words used by children in the composition of the text and also to the chain of utterances produced by them in the interaction with the peers and with the teachers at the time of collective writing.

4In Early Childhood Education, the dimension related to the functioning of writing is usually stimulated, for example, in the “agenda of the day”, when the teacher reflects with the children on how certain words from the list they produce are written or at times when she usesthe children's names written on cards.

5Certainly, this attitude of children does not occur by chance. It is the result of a pedagogical work that starts from a conception of a child who thinks and is able to relate in a critical and creative way with the knowledge already accumulated in our society and with social practices.

6We consider that, in the case of writing situations in the formal education institution, even though these situations are close to the events experienced outside this context, there are marked influences from the external environment on the conditions of text production. Therefore, there is an expectation of the children in relation to the teacher, which makes her one of the interlocutors of the group in the process of textual production.

The translation of this article into English was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES-Brasil.

Received: June 27, 2021; Accepted: December 07, 2021

texto em

texto em