Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 10-Sep-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698368536707

ARTICLE

THE IMPACT OF LARGE-SCALE EXTERNAL EVALUATIONS ON THE ORGANIZATION OF PEDAGOGICAL WORK: A POSSIBILITY OF DISCUSSION FROM SUPERVISED INTERNSHIP

1Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo, campus Bragança Paulista (IFSP-Bra). Bragança Paulista, SP, Brasil.

This article aims to analyze the presence of large-scale external evaluations in the organization of the pedagogical work of schools oversaw by the mathematics undergraduates from the Federal Institute of Education, Science, and Technology of São Paulo, Bragança Paulista campus, during their supervised internship, contemplating the reflections created by them from theoretical studies that guided this process. For this purpose, considering the technique of content analysis, 19 reports built in the 2nd semester of 2019 by the undergraduates of the Licentiate Degree in Mathematics were analyzed. It was observed that, during the internships, the undergraduates were faced with the repercussions of external evaluations on the organization of the pedagogical work. Such repercussions permeate the moments of Collective Pedagogical Work Classes (ATPC), Class Councils, Parent-Teacher Meetings, and the planning of activities for students. The analysis of the reports shows that the future teachers reflected on these repercussions about school management, pedagogical practices of teachers, and the training process of students. It is argued that teacher training courses devote time and space to analyze the relationship between assessment and organization of pedagogical work, in order to foster the (de)construction of concepts and practices related to the logic of training and curriculum structure, arising from large-scale external evaluations.

Keywords: large-scale external evaluation; organization of pedagogical work; supervised internship; teacher training

Este artigo tem por objetivo analisar a presença das avaliações externas em larga escala na organização do trabalho pedagógico das escolas acompanhadas pelos licenciandos em matemática do Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo, campus Bragança Paulista, durante o desenvolvimento do estágio supervisionado, contemplando as reflexões por eles elaboradas a partir dos estudos teóricos que orientaram esse processo. Para tanto, foram analisados, considerando a técnica de análise de conteúdo, 19 relatórios construídos, no 2º semestre de 2019, pelos licenciandos do curso de Licenciatura em Matemática do referido curso. Foi observado que, durante a realização dos estágios, os licenciandos se deparam com as repercussões das avaliações externas na organização do trabalho pedagógico. Tais repercussões perpassam os momentos das Aulas de Trabalho Pedagógico Coletivo (ATPC), Conselhos de Classe, Reuniões de Pais e Mestres e planejamento de atividades para os estudantes. A análise dos relatórios demonstra que os futuros docentes refletiram sobre essas repercussões na gestão das escolas, nas práticas pedagógicas dos docentes e no processo formativo dos estudantes. Defende-se que os cursos de formação de professores dediquem tempo e espaço para análise das relações entre avaliação e organização do trabalho pedagógico, de modo a fomentar a desconstrução de concepções e práticas relacionadas à lógica do treinamento e do estreitamento curricular, advinda das avaliações externas em larga escala.

Palavras-chave: avaliação externa em larga escala; organização do trabalho pedagógico; estágio supervisionado; formação de professores

Este artículo tiene como objetivo analizar la presencia de evaluaciones externas a gran escala en la organización del trabajo pedagógico de las escuelas acompañadas por los estudiantes de licenciatura en matemáticas del Instituto Federal de Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología de São Paulo, campus Bragança Paulista, durante el desarrollo de la pasantía supervisada, contemplando las reflexiones que construyeron a partir de los estudios teóricos. Para ello, considerando la técnica de análisis de contenido, se analizaron 19 informes elaborados en el 2º semestre de 2019 por los estudiantes de la Licenciatura en Matemáticas del dicho curso. Se observó que, durante las pasantías, los estudiantes del pregrado enfrentan a las repercusiones de las evaluaciones externas en la organización del trabajo pedagógico. Tales repercusiones permean los momentos de las Clases de Trabajo Pedagógico Colectivo (ATPC), Consejos de Clase, Encuentros de Padres y Maestros y planificación de actividades para los estudiantes. El análisis de los informes muestra que los futuros docentes reflexionaron sobre estas repercusiones en la gestión de las escuelas, en las prácticas pedagógicas de los docentes y en el proceso de formación de los estudiantes. Se argumenta que los cursos de formación docente dedican tiempo y espacio al análisis de la relación entre evaluación y organización del trabajo pedagógico, con el fin de propiciar la (des) construcción de conceptos y prácticas relacionados con la lógica de la formación y el estrechamiento curricular, derivados de evaluaciones externas.

Palabras clave: evaluación externa a gran escala; organización del trabajo pedagógico; pasantía supervisada; formación de profesores

INTRODUCTION

Educational assessment understood by Freitas et al. (2009), concerns three interconnected levels: classroom evaluation under the responsibility of the teacher; large-scale external evaluation1 carried out by the federal government or even by states and municipalities; and the institutional evaluation, developed by the school community when looking at itself, having as reference its Pedagogical Political Project.

Without neglecting to consider the interaction between these levels, we will focus our attention especially on large-scale external evaluation. This is a level of assessment that began to enter our country around the 1990s as a result of financial agreements established with international organizations, such as the World Bank (LIBÂNEO; OLIVEIRA; TOSCHI, 2012). In the guidelines received by the countries that accepted these agreements, the evaluation is revealed since it monitors the quantitative results, especially those that refer to the learning chosen as essential for the performance in the productive system (LIBÂNEO, 2013).

As a consequence, there is a proliferation of large-scale external evaluations. In addition to those carried out at the national level, states and municipalities developed their evaluation systems, as demonstrated by Sousa (2013). Several studies have also denounced the repercussions of this level of educational assessment on the organization of pedagogical work. There are impacts on school management, projects carried out, curriculum organization, classroom practices, and the training process of students (ARCAS, 2009; MENEGÃO, 2016; JÜRGENSEN; SORDI, 2017; RODRIGUES, 2018).

In this way, the initial training of teachers can also be affected, especially during the supervised internships, when the undergraduates begin to get closer to their future place of professional performance, observing/experiencing the practices that are being developed there. We defend that teacher training courses provide their undergraduates with the opportunity to reflect on the relationship between evaluation and organization of pedagogical work. With this intention, we aim to analyze in this article the presence of large-scale external evaluations in the organization of the pedagogical work of schools oversaw by undergraduates in mathematics from the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of São Paulo, Bragança Paulista campus (IFSP-BRA- Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia), during the development of the supervised internship, contemplating the reflections they built from the theoretical studies that guided this process.

Therefore, we consider the reports prepared by the undergraduate students of the aforementioned course carried out in 2019 in the first stage of the supervised internship. Based on content analysis (BARDIN, 1977), we sought to highlight the passages related to the presence of large-scale external evaluation in the activities developed by schools and monitored by undergraduate students, as well as the analyzes carried out by them. We believe that if there is no movement to problematize such experiences, large-scale external evaluation can influence the conceptions of these future teachers, inducing their practices.

LARGE-SCALE EXTERNAL EVALUATIONS AND THEIR REPERCUSSIONS ON THE ORGANIZATION OF PEDAGOGICAL WORK

Large-scale external evaluations are now in their third generation in Brazil. Thus, in addition to being applied in a census way which makes it possible to establish rankings, in certain systems there is a reward for the results obtained (BONAMINO; SOUSA, 2012; BONAMINO, 2013). These rewards are given to reward the “good” work done, which would lead, in this conception, to the improvement of education. Consequently, those who do not reach the goals are “punished”, and they do not get these awards. However, this accountability process does not only occur with (non)rewarding. Accountability, based on large-scale external evaluations, is also present when the results are identified by the institution, allowing the spotlight to be focused on school actors (FREITAS, 2013). As an effect, we have in both scenarios the repercussions of these assessments in the organization of pedagogical work.

In this way, when researching high schools in the São Paulo State Network, Rodrigues (2018) highlights the monitoring and pressuring for results from the Education Directorate to the schools management teams. The author highlights the “movement to align the organization of pedagogical work, striving for the standardization of content and methods” which extends to the managerial control of the management of servers within the school (RODRIGUES, 2018, p. 376). For Rodrigues (2018), the subordination of content and methods follows the requirements of large-scale external evaluations, in this case, those present in Saresp (School Performance Assessment System of the State of São Paulo- Sistema de Avaliação do Rendimento Escolar do Estado de São Paulo) and AAP (Assessment of Learning in Process- Avaliação da Aprendizagem em Processo)2.

It is worth mentioning that Saresp has been part of the reality of state schools in São Paulo for years, and several studies, such as Rodrigues (2018), point out the impacts of such a policy, for instance, the research by Arcas (2009). At that time, the researcher already highlighted the relationship between large-scale external evaluation in the state of São Paulo as an element of public policy management and its use aimed at rendering accounts, rewards, and punishment (ARCAS, 2009). We cannot fail to mention that even with a focus on quantitative results and with several actions aligned to this end (RODRIGUES, 2018), the state network of São Paulo has not shown progress in its indexes. The Government of São Paulo’s Strategic Plan for education, from 2019 to 2022, admits by analyzing the historical series, that progress has been slow, especially in high school (SÃO PAULO, 2019). However, the logic of testing continues in the aforementioned teaching network, bringing, as we have already said, repercussions for the organization of the pedagogical work of schools.

Such repercussions are not observed only in networks that use large-scale external evaluations to reward or punish their professionals, by adopting the bonus. In this direction, we have the study developed by Menegão (2016) that analyzed the impacts of Prova Brasil on the curriculum of the municipal network of Cuiabá, in which there is no bonus for the results obtained. The author identified changes in the annual planning, the teaching plan, the methodology used by teachers, the organization of students in the classroom, and the assessment of learning, with the use of more tests and mock tests. According to the researcher, large-scale external evaluations have a strong regulatory and inducing character, demarcating what should be taught to students. Teaching goes back to the basics.

We understand, by basic, the minimum, but in the testing scenario, the basic is being understood as maximum. In this way, we are witnessing the implementation of a curriculum based on the basics. Borrowing the businessmen's vocabulary, we can say that the knowledge that the PB [Prova Brasil] is taking from the subjects is being a ceiling and not a floor” (MENEGÃO, 2016, p. 652, emphasis in the original).

Still considering the findings of Menegão (2016), we can highlight, in addition to the curricular narrowing, the narrowing of the teacher's role. Immersed in the logic of accountability for the results obtained, the teacher ends up playing a more technical role, of mere preparation for tests, shrinking more active and creative actions that are of his authorship and that promote the expanded human formation of the students. After all, as the author points out, “teachers cannot be indifferent to the results and take into account the rankings”, thus, “they end up changing their pedagogical practice in an attempt to improve their image as a teacher” (MENEGÃO, 2016, p. 653, emphasis in the original).

Especially regarding the teaching of mathematics, one of the curricular components of external evaluations, we need to consider the notes made by Jürgensen and Sordi (2017). For the authors, the direction caused by large-scale external evaluations and the logic of testing favors the traditional teaching of mathematics and, therefore, impoverishes students' mathematical experiences. Traditional mathematics teaching, as the authors explain, is based on practices that rely on the execution of exercises that limit students' creativity and critical thinking, since there is no space for discussions about solutions and paths taken to find them. Thus, mathematics ends up being reduced to information already available, with the application of procedures instead of practices that enable investigation.

Considering the current political scenario, we believe that the logic of testing tends to intensify in our country. As provided for in Ordinance 458 of May 5, 2020, there will be changes to the National Basic Education Assessment Policy. The annual application of large-scale external evaluations is planned from the 2nd year of elementary school onwards, in addition to sending a report card to families. For Freitas (2020), we are facing meritocratic insanity. The author states that “this immersion in competition establishes individualism in children from an early age, and the idea that those who do not accumulate merit do not have access to rights - these become a responsibility of the individual and no longer an obligation of the State. To have merit is to do well in tests and have a higher grade” (FREITAS, 2020).

Therefore, we understand that the organization of pedagogical work in schools and the training process of our students may be even more demarcated by large-scale external evaluations and their matrices. Thus, it is imperative to debate, in teacher training courses, the relationship between evaluation and organization of pedagogical work, in the path of building resistance and alternatives. In our understanding, this can occur considering the development of the supervised internship.

Without disregarding the limits imposed by our historical moment, we increasingly need to make the “classroom a space of action as important as other spaces of struggle” (FREITAS et al., 2009, p. 21). The struggle in the classroom is necessary both in higher education and in basic education. In the higher education classroom, we need to devise ways to (de)construct conceptions related to educational evaluation so that, when they work professionally, these future teachers can have robust conceptual background and inspirations that lead them to develop emancipatory evaluative propositions, constituting their struggle in the basic education classroom.

The necessary discussion about large-scale external evaluations and the organization of pedagogical work: a possibility from supervised internships

The supervised internship is foreseen in the National Curriculum Guidelines for the Initial Training of Teachers for Basic Education. Thus, 400 hours of licensure courses must be devoted to this purpose (BRASIL, 2015)3. In the IFSP-BRA’s Mathematics Degree course, the supervised internship is organized into five internships of 80 hours each.

In the first stage of the internship of the aforementioned course, “the intern still does not follow the work of the teacher in the classroom. Its purpose is to know the administrative, organizational and pedagogical dimension of a public school in the final years of elementary or high school” (INSTITUTO FEDERAL DE CIÊNCIA E TECNOLOGIA DE SÃO PAULO, 2019, p. 41). In this way, it is expected “to provide the future teacher with an understanding of the school context beyond the classroom” which is not isolated from the world (INSTITUTO FEDERAL DE CIÊNCIA E TECNOLOGIA DE SÃO PAULO, 2019, p. 38).

The undergraduates are advised to look for public schools in the final years of elementary school or high school to develop the first stage of the internship. As an activity, they can carry out the reading and analysis of school documents, especially the Pedagogical Political Project, observation of the school context and its surroundings, reflection on the relationships between different segments, and moments of collective work, such as several meetings and decision-making processes.

Each stage of the supervised internship of the Mathematics Degree course at IFSP-BRA is linked to its respective curricular components, which should favor the relationship between theory and practice. In the first stage, the curricular component is called Organization of Pedagogical Work, Assessment, and School Management. According to its syllabus, among other aspects, the curricular component “introduces a reflection on school organization, from its political-social context and its relations with the organization of pedagogical work, evaluation, and school management” (INSTITUTO FEDERAL DE CIÊNCIA E TECNOLOGIA DE SÃO PAULO, 2019, p. 155).

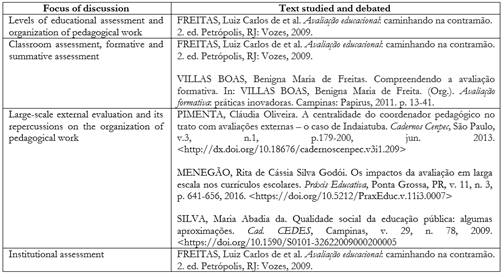

In the classes of this curricular component, undergraduates receive guidance on internship activities, carry out studies and discussions of texts, and share their internship experiences, which are analyzed collectively. Especially regarding studies related to educational assessment, in the second half of 2019, there was a debate on the texts presented in Box 1.

During the study and debate of these texts, at certain times, we present some problem situations so that the undergraduates could reflect through dramatization, as in the following example: In a collective work meeting at a school, with the presence of the management team and the faculty, there is a discussion about large-scale external evaluation. Some defend the use of external evaluations and others are against it. What arguments could these different groups present?

The undergraduates, throughout the internship, prepared an analytical descriptive report. Thus, in addition to describing the activities carried out, the interns were instructed to reflect on what was observed/experienced, approaching the theoretical framework studied and discussed in the curricular component that is linked to the internship stage. We take these reports as material for analysis of the presence of large-scale external evaluations in the organization of the pedagogical work of schools accompanied by undergraduates in mathematics during the development of the supervised internship, without losing sight of the reflections they built.

Thus, we resort to content analysis which, according to Bardin (1997, p. 38), is a “set of communication analysis techniques that use systematic and objective procedures to describe the content of messages”. Considering the three chronological poles pointed out by the author - pre-analysis, exploration of the material, and treatment of the results - we started the process by performing a floating reading of the 19 reports4. At this point, we identified the presence or absence of statements related to large-scale external evaluation. Then, we proceeded to explore the material, carrying out coding operations based on the messages that were related to what we were looking for. Finally, we reorganized such messages to make interpretations and inferences possible.

Of the 19 reports analyzed, we identified 14 of them as having statements that referred to large-scale external evaluations. We consider that this is an expressive amount since it corresponds to almost 75% of all reports. We also believe that the absence of mentions related to external evaluations in the other reports does not mean that they do not affect the organization of the pedagogical work of the monitored schools, but that the interns may have been involved and dedicated to the reflection of different aspects that make up the school’s reality. As it is an internship stage in which the intern does not follow the classroom yet, multiple themes were present in the reports, for example, the description of the community, the different colleges existing in the institution, the projects developed by the school, the relationship of the intern with the different school actors, among others. Next, we present the data obtained from the report's content analysis process, focusing on large-scale external evaluations and analyses carried out by licensees.

KNOWING AND REFLECTING ON THE REPERCUSSIONS OF LARGE-SCALE EXTERNAL EVALUATIONS ON THE ORGANIZATION OF PEDAGOGICAL WORK BASED ON INTERNSHIP REPORTS

One of the activities carried out by the students of the Mathematics Degree course at IFSP-BRA in the first stage of the internship concerns the reading of school documents, especially the Pedagogical Political Project (PPP). It is a fundamental document for the referred stage of the internship, since, as highlighted by Veiga (2002, n.p.),

[...] the political-pedagogical project has to do with the organization of pedagogical work on two levels: as an organization of the school as a whole and as an organization of the classroom, including its relationship with the immediate social context, seeking to preserve the vision of wholeness. In this journey, it will be important to emphasize that the political-pedagogical project seeks to organize the pedagogical work of the school as a whole.

In the reports analyzed, we noticed that some of them were dedicated to describing how large-scale external evaluation appeared in PPPs. The following statements5 demonstrate how the interns approached this discussion. We will notice that, in some cases, there is, in the PPP, the description of the external evaluation and its objectives, being placed as a means to identify the problems of the school and to raise the indexes.

In its Pedagogical Plan, with specific or general objectives, the school will seek to “raise the rates of external and internal assessments”, proposing “activities that address the skills requested in the official curriculum” and “applying assessment activities following the guidelines of external assessments”, since the Coordinating Teacher's role is to “expand the students' domain of knowledge, raising the level of school performance evidenced by external and internal assessment instruments”. It is known that large-scale tests aim to quantify and compare results. [...] If the goal is to always achieve the results expected by the Department of Education, the school can weaken its pedagogical and managerial autonomy by changing the perspective of the man and society that it proposes to train. (Antonio Report6, 2019).

We also observed a reflection on the relationship between external evaluation and classroom evaluation, carried out by the teacher. Based on the analysis of the PPP, the undergraduate Arthur discusses, in his report, whether an external, punctual evaluation can say more about the students' learning than those developed by the professor who constantly monitors his class.

“Idesp is an indicator created in 2007 by the São Paulo Department of Education to assess the quality of the 5,183 schools in the network. In this assessment, it is considered that a good school is one in which most students learn the skills and abilities required for their grade within an ideal period - the school year. It is composed of two criteria: student performance in the Saresp proficiency exams (“how much they learned”) and school flow (“how long they learned”)” (School PPP). Here it can be seen that the concept of a good school is related to its performance in an external evaluation - which is a problem, because, according to Pimenta (2013, p.184), “[...] external evaluations can be useful for a greater improvement of school work, as long as they are understood as constitutive of pedagogical practice and not as the only instrument to guarantee the quality of the educational process”. [...] In the PPP, there is the following problem : “Our school has a high rate of students below the basic level, according to an external evaluation carried out by the Secretary of State for Education - Saresp. Analyzing the results, we confront several factors that make it difficult to advance in learning, including irregular attendance and indiscipline in the classroom.” Reading this part of the PPP, what I was thinking about when the school says that the students have a high index below the basic level is an external evaluation - which cannot be completely true, because we can say that external evaluations can be useful to improve school work (PIMENTA, 2013), but I believe that the internal evaluation carried out by the teacher who monitors their students daily is more useful than an external evaluation to say about the student (Arthur Report, 2019).

As we can see, there is a reflection by the students when large-scale external evaluation is considered sovereign in the identification of weaknesses in the school, and such weaknesses are often associated with the indexes obtained in these evaluations. Still, on the PPPs, we have the relationship established by a graduate student between what is written and what is lived. In her report, she describes that the School's Political Pedagogical Project states that the evaluation developed by the institution is based on formative assessment. However, according to the intern, what is observed in the school's daily life is a concern with preparation for large-scale external evaluations.

According to the author Villas Boas (2011), formative assessment has the aspect of promoting learning and is attentive to the needs and individual characteristics of the student. Since the school proposes to use formative assessment, the observed practice indicates a more traditional assessment, with the application of tests to prepare for external evaluations. (Ana Report, 2019).

Especially in the state network of São Paulo, there is a set of aligned programs whose guiding thread is large-scale external evaluation and which end up having repercussions on the organization of pedagogical work and the training of students. Rodrigues (2018) highlights this alignment considering the Learning Focus Platform (Plataforma Foco de Aprendizagem), AAP, and Saresp. In this way, we added the Results Improvement Method (MMR- Método de Melhoria de Resultados) which, as stated in the Strategic Plan (SÃO PAULO, 2019, p. 20),

[...] it is a participatory management method for improving learning outcomes, in which the school community carries out the diagnosis, planning, development, monitoring, and readjustment of actions. Each school prepares its improvement plan based on the student learning diagnosis available at Learning Focus, in a process in which teachers and management teams define priorities and agree on actions that are directly related to the continuous improvement of learning outcomes.

The centrality of the results appears in this description. We cannot forget that the learning outcomes mentioned refer to the results obtained in the external evaluations which are inserted in the Learning Focus Platform to guide the actions of the actors in the schools.

Learning Focus Platform is a platform that brings together student learning indicators based on the results of diagnostic, formative, and summative assessments, supporting managers and teachers in pedagogical interventions, planning MMR actions, and monitoring assessment processes. In the Learning Focus Platform, there are indicators of external and internal assessments such as Saresp and the Assessment of Learning in Process (AAP), and new diagnostic assessments and evaluations of the Basic Education Assessment System (Saeb) will be included in 2019, as well as the Index of Basic Education Development (Ideb) (SÃO PAULO, 2019, p. 20).

In the analysis by Rodrigues (2018), the Learning Focus Platform has made the alignment process more sophisticated, since when it is digitally fed with the AAP results, it easily provides a list of skills for each class, indicating what needs to be taught. Therefore, there are processes of curricular narrowing and subordination of teaching work, as identified by Menegão (2016). This alignment that is built using large-scale external evaluations as a guide was also present in the reports of the interns of the Mathematics Degree course at IFSP-BRA. In the fragments presented below, we see how actions are carried out in schools based on these assessments and existing programs in the state network of São Paulo.

The main project that the school is attending, which was sent by the network to all schools in the state, is the MMR (Result Improvement Method), which is a plan sent to improve the functioning of management to improve the results of the school in external assessments such as Saresp and Prova Brasil (Saeb). (Armando Report, 2019).

From this map [Learning Focus Platform] teachers and the management team have access to the entire context of the assessment, identifying the theme, skills, and level of mastery of each class and student. It is interesting to have a system that gathers all this information, but one should not let the demand for an external evaluation limit an entire school context that includes the other subjects and not just the two that are required, that is, limited to the “curricular narrowing the focus on two subjects”, as Menegão said (2016, p. 649). All content has its due importance and there is often a narrowing of what will be worked on to meet the demands of the evaluations. (Aline Report, 2019).

One of the most striking murals is in the hallway of the classrooms and focuses on the Results Improvement Method (MMR). [...] as an intern, I was able to have experiences in the AAP, ADC [Complementary Diagnostic Assessment - Avaliação Diagnóstica Complementar]7

and Saresp, and today I see that Claudia Pimenta (2013) was right in saying that the assessment ends up being the school's guide (PIMENTA, 2013) (Luis Report, 2019).

In that direction, we have two more excerpts. One of them indicates the discomfort of professors in the face of external evaluations and the MMR with its promise to promote improvements in the institution. The other describes how supervision visits to the school focus on the Outcome Improvement Method. In the undergraduate student Thiago's Report, we note the student's reflection on the MMR which, as we have already stated, is centered on the indexes obtained in external evaluations. For this future teacher, it is a ready-made, superficial recipe, not possible to apply to the entire school system.

According to my observations of the school context, teachers are not comfortable with the issue of external evaluations nor with the issue of MMR (Method of Improvement of Results), implying that this would be the salvation of education by the government. [...]. This discomfort in the evaluation is caused by “[...] the appealing situation of external evaluations, through demands and pressures [...]” (MENEGÃO 2016, p.653). (Luiza Report, 2019).

A common form of external assessment nowadays, which takes place in schools in the state of São Paulo and was implemented in 2011 [...] are the Process Learning Assessments (AAP), whose results guide some actions of the Program Management in Focus8[...]. It is worth mentioning that this instrument only addresses the contents studied in Portuguese and Mathematics, as well as in the Saeb [Basic Education Assessment System]. According to Menegão (2016, p.648) “the emphasis given by large-scale evaluations to the cognitive aspects of Portuguese and Mathematics has led to a narrowing of the curriculum, especially because it promotes situations in which teaching and learning for the test is the main reason for teaching.” [...] The MMR works in 8 pre-established steps, from the recognition of the problem to the registration and dissemination of what was done to solve it. For this, the school management must “feed” the part destined to the MMR in the Digital School Secretary (SED- Secretaria Escolar Digital), raising the problems, describing the causes, elaborating improvement plans, implementing the actions to be taken and monitoring the results to complete the actions established by the date defined for each one of them. The program establishes a certain control of the government, which has access to all the school's records, that is, to all the actions that the school is taking and must be accountable for. This also occurs with the AAPs, which must have their grades recorded in the SED, generating a survey of the skills not covered by each student and the result that each room achieved in the appropriate instrument. [...] One of the documents read during the internship period was the Term of Visits, which deals with the issues discussed during the visits of the teaching supervisor to the school. In almost every visit, the MMR Plan is worked on, and the actions are revisited and verified to assess which ones should continue, which ones have already been achieved, and whether new actions should be proposed. I had the opportunity to participate in an MMR meeting, which took place at the beginning of the 4th bimester, planning for the same, in addition to the actions carried out in the 3rd bimester. [...] I confess that the Management in Focus program and the use of the MMR Plan are incomprehensible and superficial, being a ready recipe, in my eyes, which in my opinion, does not apply to all schools, as it intends to (Thiago Report, 2019).

We identified this alignment from the large-scale external evaluations in most of the reports that contemplated such a discussion. In this sense, we have fragments that refer to the presence of external evaluations in the moments of ATPC (Collective Pedagogical Work Class- Aula de Trabalho Pedagógico Coletivo).

I could observe some repetitions in the guidelines [of the ATPCs], always appearing external evaluation and the MMR, coming from the Department of Education. [...] the coordinator needs to show results to the director and supervision, so external evaluation is a key gear in the school. (Luis Report, 2019).

[...] in one of the ATPCs, for example, they talked about 7th grade who was drawn to participate in the School Performance Assessment System of the State of São Paulo (Saresp). The principal asked how this group was performing, the teachers replied that it was the worst group in the school, they were “very weak”. With that, the principal said: “you will have to do mocks with them for Saresp”. There was opposition from the teachers, as they said that this was one of the most undisciplined groups and the principal said: “now what counts is learning” since the ideal would be to try to solve the students' learning difficulties regardless of external tests. With this, we can highlight the ideas of Freitas, Sordi, Malavasi, and Freitas (2009) who claim about evaluations as an instrument of symbolic power in the school, and the ideas of Menegão (2016) who analyze the impacts of external evaluation on curricula, in methodologies, assessments, in classroom relationships. The influence of external evaluations on management-teacher relationships is explicit, demanding a change in the development of their classes to achieve good placements in these assessments and teacher-student in demanding to achieve goals. With this, the main objective of the school becomes the fulfillment of the demands made by the evaluations (Danilo Report, 2019).

As we can see, moments of collective work (ATPCs) end up becoming times and spaces for the debate about large-scale external evaluations. However, this is a debate that, again, is in the wake that leads to the alignment of actions, whose purpose is to increase the indexes. As described in Danilo's Report, this affects the organization of the school's overall pedagogical work and the organization of pedagogical work in the classroom. As in a cascading effect, management, concerned with the results of external evaluations, conveys to teachers what must be done, which in turn, changes their plans. In this scenario, what happens to the students' learning and training processes? In his report, the undergraduate Thiago states that such a process is aimed at teaching and learning for the test.

The emphasis given by the large-scale evaluation to the cognitive aspects of Portuguese and Mathematics extends to the ATPC moments, where, in some of them, Portuguese and Mathematics teachers are separated from the others to prepare lesson plans based on skills included in the Saresp 2018. It was at one of these moments, when the three mathematics teachers were drawing up the lesson plans together that happened what I reported previously, when one of the three teachers said: “ Let’s work the activities with the question bank from Saresp, without any new content, or long explanation... We will teach you how to eliminate the absurdities, and teach you how to answer the test. The ones that give you more doubts, we do it on the blackboard.”. From this perspective, student learning is not in the background, but in the last, since there is no concern with the content to be assimilated, but, resuming Menegão (2016), the concern with teaching and learning for the test. Meanwhile, the “other teachers” (in an ironic tone) who are not Portuguese or Mathematics, take the ATPC's time filling in a diary or even reading text and discussing what constitutes “special education” for students with disabilities. (Thiago Report, 2019).

It is also worth mentioning the issue of interdisciplinarity, described by two interns. What is called interdisciplinarity corresponds to the emptying of curricular components that do not make up the matrix of large-scale external evaluations.

In one of the ATPC schedules, we had a Mathematics workshop [...]. The activity took place with math games in teaching, and it was a moment of great relaxation in a great environment. The reason for it to be carried out with all teachers is the action implemented about the focus on teaching Mathematics, which has already been mentioned above, in which all teachers inserted in their classes a way of working some Mathematics, with the justification of working on skills not covered by Saresp 2018. Two examples to report are from Physical Education and Art teachers. The Physical Education teacher worked in his classes with the notions of area and perimeter, performing measurements in the multi-sport court. The Art teacher, on the other hand, elaborated a question on her test about the collection of a 7-member Korean band, telling a brief story about K-pop culture and asking how much each of the members would receive if the profits of the show were a given amount. [...] In one of the moments of ATPC, we had a double schedule, with the presence of two PCNPs (teachers coordinating the pedagogical nucleus), who are part of one of the actions of the MMR. The PCNPs are specialized in special education and literacy and have highlighted the good climate and the union of the school, referring to interdisciplinarity, where all teachers work with Portuguese and Mathematics: “There are schools where we arrive and the teacher does not have this concern, and then creates a climate where Portuguese and Mathematics teachers use the argument 'When you get a Saresp bonus, you want it, right?'”. The PCNPs highlighted that Portuguese and Mathematics teachers are being massacred, in terms of content and external pressure, in most of the schools they attend. With that comment, one of the math teachers joked “Hallelujah, someone listened to us!” and provoked a revolt in the PC, which replied “This is not true! I'm doing everything I can to take tthe weight off you guys” and used “interdisciplinarity” as an example. (Thiago Report, 2019).

[...] teachers work with the skills and competences required in these evaluations. Although the curriculum content is only Mathematics and Portuguese, teachers of other subjects also address the skills and competences that the student needs to know to carry out the assessment. For example, the issue of text interpretation and image reading does not necessarily have to be worked on only in Portuguese but can be worked on in any other subject (Luiza Report, 2019).

Rodrigues (2018), in his research, draws attention to the constitution of the so-called “interdisciplinary activities” that end up contributing to the narrowing of the curriculum. As defined by the researcher, we are faced with the pedagogy of competences and skills that, in some cases, counts on the adhesion of teachers. On the issue of interdisciplinarity, Rodrigues (2018, p. 287), explains that

[...] the aligned and guided involvement of teachers from different areas according to a set of skills required by the curriculum and assessments is characterized as interdisciplinary work. Consequently, professionals whose subjects will not be evaluated end up subordinating their work to the prescriptiveness of the required skills, giving up broader content to incorporate, into their practice, only the “knowledge” that intersects with what will be charged (original quotes).

In the reports, we also find the presence of large-scale external evaluation in Class Councils and Parent-Teacher Meetings. The following statements show us that, in addition to training actions for standardized tests, there is also an attempt to “convince” students and their families to “engage” in carrying out external assessments in certain schools. This attempt to “persuade” includes blackmail strategies involving the (non) issuance of certificates of completion of basic education, the possible dismissal of civil servants, and the chances of receiving teaching materials.

[...] other observations [in the Class Council] were about the School Performance Assessment System of the State of São Paulo (Saresp) that they will make this year. Saresp would be used as terrorism for students, only those who took the test would get their high school diploma and, thus, graduate. (Luis Report, 2019).

In the case of 9th grade B, it was talked about at the beginning [of the Class Council] about external evaluations, and how they [students] were unwilling to take the tests, that they didn't even read the tests because there were no underlines in the questions of the tests. Soon after these speeches, the GCP [General Coordinating Professor] stressed that the external evaluation was not the focus, but their learning. However, the talk about hitting the goal (it was understood that this goal would be Saresp's) was very recurrent, in addition to mentioning the bad behavior of the class and how it influenced their performance. After a while, the principal entered the place with a supervisor, and the GCP repeated some lines for the principal to give an opinion, and then, she said many times how much their performance in the tests reflected in the management, and that if the performance in the evaluations it was below expectations, the management could “be sent away”. (Helena Report, 2019).

After that moment [at the Parent-Teacher Meeting], the GCP provided slides with information about the results of external evaluations, from Saeb and Saresp. He said that at the end of the year they would hear every day from the students about simulations, tests, and more simulations, which was to be prepared. He pointed out that the grades were indicators of quality and they were above average, and that the school was “pulled” to maintain these indices. All the speeches about the external evaluations draw attention, because, in a way, they took over the center of the school [...] In a third moment, parents were invited to go to their children's room for some more detailed information. In each room, there were the coordinators of the class and they reviewed the important dates for the end of the year. Again, they talked about the importance of external assessments and how all teachers took this very seriously, as there were cases like in English class, the teacher takes 15 minutes for students to ask Saresp questions, and parents are told to reinforce at home this importance [...]. (Helena Report, 2019).

Another theme [from the Parent-Teacher Meeting] was that the Saeb and Saresp tests are coming up and he asked again for the parents not to allow their children to miss that day, as it is very important to do the tests that generate a comparative index with all the schools in the rural area of the city [...], and the government will realize that the students want to study and will send the teaching material. (Ana Report, 2019).

The analysis of the Integral Education Program (PEI- Aula de Trabalho Pedagógico Coletivo) of the state network of São Paulo goes beyond our scope. However, we cannot fail to mention that Helena's Report refers to a school belonging to PEI . We make this observation because, although the program carries integral education in its name, we are convinced that PEI schools are also directed to the goals of large-scale external evaluations, which may not favor the expanded human formation of students. In these schools, teachers are subjected to 360º evaluation9 , and depending on the results, they can be dismissed from the PEI, failing to receive the 75% bonus in their salary (VENCO; MATTOS, 2019).

Thus, it is not surprising that in PEI schools - as exemplified in the following statements - there are also alignment practices that comply with the booklet of the São Paulo state network that, as we have already stated, are basted by large-scale external evaluations.

I arrived one day when one of these classes had taken place and talking to some students, they said that these classes take place for the 9th grades and the 3rd grades of high school. The contents of the classes were only Portuguese and Mathematics. They took place in the morning, and in the afternoon, the students were free “to relax”, they even had a movie session [...]. A few weeks after what happened, another panel appeared in the central hallway of the school, on which there was a countdown of the days for Saresp to happen [...]. (Helena Report, 2019).

With the data presented, we can see that the undergraduates were faced, at various times, with practices that show the repercussions of large-scale external evaluations in the organization of pedagogical work. Given the above, we defend that the debate about the levels of educational evaluation has a privileged space in teacher training courses. We believe that such debate can occur considering the experiences provided by the supervised internship. We see the supervised internship as an extremely important moment in the training process of future teachers.

In the supervised internship, the undergraduate is faced with real situations that may be present when developing their professional performance. In other words, the internship can be the “link of organic articulation with reality” (KULCSAR, 2012, p. 58). The internship also has the potential, as stated by Almeida (2021, p. 8), to enable the student to “see and think about the school differently. [...] Previously participating in the institution as a student, this process allows (re)knowing the school from another place, with discoveries”. However, it is necessary to emphasize that in this training process, to go beyond appearances, reflecting based on the theoretical framework is necessary. In this way, we glimpse the constitution of praxis, which can reveal what is overshadowing the look at the school and the organization of its pedagogical work.

In this process, there is the possibility of problematizing the repercussions of large-scale external evaluations on the organization of pedagogical work. From the experiences of the undergraduates in their internships, articulated to the theoretical repertoire, it is possible to establish some questions. What is the concept of quality that underpins the evaluation policies in progress in our country? How does it arrive and materialize in schools? What are its impacts on the relationships established between teaching professionals? How does it influence the training process of students? And yet, “what price, as a society, are we willing to pay to produce evaluation indexes that barely reflect the reality of public schools in São Paulo and Brazil”? (GIROTTO; CÁSSIO, 2018, p. 22).

We tried to make these reflections possible for undergraduates in mathematics from the IFSP-BRA. We believe that the information presented in this article shows that these future teachers have built a broader view of the evaluation processes, understanding the repercussions of large-scale external evaluations for school management, the pedagogical practices of teachers, and the training process of students. In our understanding, this may favor future analyzes that will be developed by them, as they follow, in the other stages of the supervised internship, the practices carried out in the classroom. They will be able to reflect on the teaching of mathematics, if there are opportunities for investigative actions and the debate of the constructed solutions, or if they follow the path of simple execution of exercises and training for tests.

According to recent research (VILLAS BOAS; SOARES, 2016; SADA, 2017), the discussion about evaluation has taken up little space in teacher training courses. This leads us to infer the tendency to reproduce conceptions and practices, many of which, as exposed in this article, make up the pedagogy of competences and skills, adjusted to goals imposed on schools from indexes obtained through the periodic application of standardized tests. On the other hand, we understand that teacher training courses - encompassing what is experienced and analyzed in internships, in conjunction with research developed in the area of educational evaluation - can help the undergraduate to “face the world of work and contribute to the training of their political and social conscience, joining theory to practice” (KULCSAR, 2012, p. 58).

As highlighted by Villas-Boas and Soares (2016, p. 245), “teachers, in general, are still attached to the assessment of learning. The other two levels of assessment (institutional and large-scale), even if they exist within the school, are not usually the object of reflection”. The authors also point out that

[...] the experiences of institutional and large-scale evaluation experienced by students of the investigated degree courses are limited. These levels are not worked pedagogically and, when approached, are treated at the level of common sense or are fixed in the transfer of information or opinions expressed and disseminated by the media, which creates obstacles in the triggering of denser reflections and the analytical confrontation of the results of internal and external evaluation. (VILLAS BOAS; SOARES, 2016, p. 245).

The data presented here show that large-scale external evaluation is present in the daily life of our schools and, therefore, is present in supervised internships. Therefore, it is imperative to broaden the discussion on educational assessment in teacher training courses. A discussion that goes beyond assessment as the use of instruments and techniques aimed at the classroom. A discussion that does not shy away from contemplating the interconnections between the different levels of assessment, considering the interests and political disputes that permeate them, which generate consequences both for teaching performance and for the training of students.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

In this article, we seek to analyze the presence of large-scale external evaluations in the organization of the pedagogical work of schools accompanied by IFSP-BRA mathematics undergraduates during the development of the supervised internship, also contemplating the reflections developed by them. To this end, we took as an object of analysis, the reports produced by the students of that course, who, in the second half of 2019, carried out the first stage of the supervised internship. Using the content analysis technique, we identified messages referring to external evaluations. Such messages were selected considering their potential to exemplify the phenomenon analyzed and presented here.

We noticed that the undergraduates reported, in their reports, episodes that show the repercussions of large-scale external evaluations on the organization of pedagogical work in schools, as already denounced by studies carried out in the area. In our view, the completion of the supervised internship, linked to theoretical discussions about educational assessment, provided the undergraduates with reflections that can foster the deconstruction of conceptions and practices related to the logic of training and curricular narrowing, arising from large-scale external evaluations. Upon noticing the actions developed by the monitored schools, the undergraduates analyzed these processes, highlighting the need to problematize the actions in line with the increase in the indexes obtained in standardized tests.

Unfortunately, the current situation indicates that there is a tendency to intensify the presence of external evaluations on a large scale in the daily life of schools since the National Policy for the Evaluation of Basic Education has taken this direction. Therefore, we believe that it is important for future teachers to understand how these assessments can guide the actions carried out by the institution, both in terms of management and in the classroom. Without reflections and the construction of propositions, there may be an intensification of the impacts of external evaluations on the autonomy of the teacher, being less of a protagonist in the construction of their planning and the realization of it, with the predominance of practices in favor of increasing the indexes. This can echo in students who, faced with the narrowing of the curriculum and training for the tests, are faced with a bottleneck in their training. Instead of expanded training that leverages multiple human capabilities, students are directed to competencies and skills that are/will be monitored in standardized tests.

We consider that the supervised internship allows the undergraduate to experience their future workplace, getting closer to their practices. Thus, it is necessary to problematize what is observed/experienced in the internships articulating it with the theory. Especially regarding the theme discussed here, we believe that such problematization should contemplate the three levels of educational assessment, which are interconnected. Establishing more time and space for these discussions promote, in our understanding, a more involved action with the school community, making the school and the classroom spaces of struggle that are against reductionism and the alignment of training processes as prescribed by the large-scale external evaluations and their matrices.

Although there are many studies dedicated to analyzing external evaluations and their impacts on basic education, based on the data presented here, we understand that we still need to develop research that focuses on the training process of teachers. We believe that it would be relevant to create studies about how the discussion about these assessments appears (or not) in the different degrees and the development of internships. We also understand that it may be interesting to investigate how such discussions can contribute to the promotion of conceptions and practices related to educational evaluation. In this way, we observe a possibility of reflection that can favor the instrumentalization of different educational actors - especially future teachers - for the construction of proactive responses to the school's accountability processes, from large-scale external evaluations that, as we have already stated, have had repercussions on the organization of pedagogical work and the training process of students.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, Luana Costa. Preciso fazer estágio professora? Estágio como experiência formativa primordial. Educação, Santa Maria, v. 46, p. 1-20, 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5902/1984644441063> [ Links ]

ARCAS, Paulo. Implicações da progressão continuada e do Saresp na avaliação escolar: tensões, dilemas e tendências. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2009. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/48/48134/tde-12032010-110212/pt-br.php#:~:text=Concluiu%2Dse%20que%20tanto%20a,enfrenta%20maior%20resist%C3%AAncia%20do%20professorado >. Acesso em 09/06/2021. [ Links ]

BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa, Portugal: Edição 70, 1977. [ Links ]

BONAMINO, Alícia. Avaliação Educacional no Brasil 25 anos depois: onde estamos?. In: BAUER, Adriana; GATTI, Bernadete (Org.). Vinte e cinco anos de avaliação de sistemas educacionais no Brasil: Implicações nas redes de ensino, no currículo e na formação de professores. Florianópolis: Editora Insular, 2013. p. 43-60. [ Links ]

BONAMINO, Alícia; SOUSA, Sandra Zákia. Três gerações de avaliação da educação básica no Brasil: interfaces com o currículo da/na escola. Educ. Pesqui., São Paulo, v. 38, n. 2, p. 373-388, 2012. <https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-97022012005000006> [ Links ]

BRASIL. MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO.Resolução nº 2, de 1 de julho de 2015. Define as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a formação inicial em nível superior (cursos de licenciatura, cursos de formação pedagógica para graduados e cursos de segunda licenciatura) e para a formação continuada. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=136731-rcp002-15-1&category_slug=dezembro-2019-pdf&Itemid=30192 >. Acesso:24/03/2022. [ Links ]

BRASIL. MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. Resolução CNE/CP nº 2, de 20 de dezembro de 2020. Define as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Formação Inicial de Professores para a Educação Básica e institui a Base Nacional Comum para a Formação Inicial de Professores da Educação Básica (BNC-Formação). Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/docman/dezembro-2019-pdf/135951-rcp002-19/file >. Acesso: 16/05/2021. [ Links ]

FREITAS, Luiz Carlos de. Caminhos da avaliação de sistemas educacionais no Brasil: o embate entre a cultura da auditoria e a cultura da avaliação. In: BAUER, Adriana.; GATTI, Bernadete A. (Org.). Vinte e cinco anos de avaliação de sistemas educacionais no Brasil. Florianópolis: Insular, v. 2. 2013. p. 147-176. [ Links ]

FREITAS, Luiz Carlos de. Insanidade meritocrática torna o Saeb anual. Avaliação educacional - Blog do Freitas. 06 maio 2020. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://avaliacaoeducacional.com/2020/05/06/insanidade-meritocratica-torna-o-saeb-anual/ >. Acesso em : 09/06/2021. [ Links ]

FREITAS, Luiz Carlos de et al. Avaliação educacional: caminhando na contramão. 2. ed. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2009. [ Links ]

GIROTTO, Eduardo Donizeti; CÁSSIO, Fernando L. A Desigualdade é a Meta: Implicações Socioespaciais do Programa Ensino Integral na Cidade de São Paulo. Arquivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, v. 26, n. 109, p. 1-26, 2018. <http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.26.3499> [ Links ]

INSTITUTO FEDERAL DE EDUCAÇÃO, CIÊNCIA E TECNOLOGIA DE SÃO PAULO. Projeto pedagógico do curso superior de licenciatura em matemática, 2019. Acesso em : 29 set. 2020. [ Links ]

JÜRGENSEN, Bruno Damien Costa Paes; SORDI, Mara Regina Lemes De. Implicações das políticas de avaliação externa para a Educação Matemática. In: FESPM, Federación Española de Sociedades de Profesores de Matemáticas (Ed.), VIIICongreso Iberoamericano de Educación Matemática. Madrid, España: FESPM, 2017. p. 482-490. [ Links ]

KULCSAR, Rosa. O estágio supervisionado como atividade integradora. In: PICONEZ, Stela C. B. (coord.). A prática de estágio e o estágio supervisionado. Campinas: SP - Papirus, 2012. p. 57-67. [ Links ]

LIBÂNEO, José Carlos. Internacionalização das Políticas Educacionais e Repercussões no Funcionamento Curricular e Pedagógico das Escolas. In: LIBÂNEO, José Carlos; SUANNO, Marilza Vanessa Rosa; LIMONTA, Sandra Valéria. (Org.). Qualidade da Escola Pública: Políticas educacionais, didática e formação de professores. 1ed.Goiânia: CEPED Publicações, 2013, v. 01, p. 1-229. [ Links ]

LIBÂNEO, José Carlos; OLIVEIRA, João Ferreira de; TOSCHI, Mirza Seabra. Educação escolar: políticas, estrutura e organização. São Paulo: Cortez, 2009. [ Links ]

MENEGÃO, Rita de Cássia Silva Godói. Os impactos da avaliação em larga escala nos currículos escolares. Práxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa, PR, v. 11, n. 3, p. 641-656, 2016. https://doi.org/<10.5212/PraxEduc.v.11i3.0007> [ Links ]

RODRIGUES, Jean Douglas Zeferino. Gerencialismo e responsabilização: repercussões para o trabalho docente nas escolas estaduais de ensino médio de Campinas/SP. Tese (Doutorado), Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2018. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://repositorio.unicamp.br/jspui/handle/REPOSIP/357861 >. Acesso em 09/06/2021. [ Links ]

SADA, Claires Marcele. A avaliação da aprendizagem na licenciatura em matemática: o que dizem documentos, professores e alunos? Tese (Doutorado em Educação Matemática) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados em Educação Matemática, São Paulo, 2017. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/186190 >. Acesso em 09/06/2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (Estado) Plano estratégico 2019 - 2022: educação para o século XXI. São Paulo, SP: Secretaria de Educação, 2019. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.educacao.sp.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/plano-estrategico2019-2022-seduc_compressed.pdf (educacao.sp.gov.br) . Acesso em : 8 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

SOUSA, Sandra Zákia. Avaliação externa e em larga escala no âmbito do estado brasileiro: interface de experiências estaduais e municipais de avaliação da educação básica com iniciativas do governo federal. In: BAUER, Adriana; GATTI, Bernadeti A. (Orgs.). Vinte e cinco anos de avaliação de sistemas educacionais no Brasil - implicações nas redes de ensino, no currículo e na formação de professores. Florianópolis, SC: Insular, 2013. p. 61-86. [ Links ]

VEIGA, Ilma Passos Alencastro. Projeto Político-Pedagógico da escola: uma construção coletiva. In: VEIGA, Ilma Passos Alencastro. (Org.) Projeto Político-Pedagógico da escola: uma construção possível. 14a edição, Papirus, 2002. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/5169326/mod_resource/content/1/PPP_uma_construcao_coletiva%20c%C3%B3pia.pdf> Acesso em : 09/06/2021. [ Links ]

VENCO, Selma Borghi; MATTOS, Rosemary. Avaliação 360º: das empresas direto às escolas de tempo integral no estado de São Paulo. RBPAE- v. 35, n. 2, p. 381 - 400, mai./ago, p. 381-400, 2019. https://doi.org/<10.21573/vol35n22019.95410> [ Links ]

VILLAS BOAS, Benigna Maria Freitas; SOARES, Lúcia. O lugar da avaliação nos espaços de formação de professores. Cad. Cedes, Campinas, v. 36, n. 99, p. 239-254, maio-ago., 2016. https://doi.org/<10.1590/CC0101-32622016160250> [ Links ]

1Large-scale external evaluation is carried out in the school, but elaborated outside it, with scope and extension (MENEGÃO, 2016). To avoid repetition, we will consider large-scale external evaluation and external evaluation synonymous.

2Although the AAP is considered a diagnostic evaluation by the Secretary of Education of the State of São Paulo, we consider it, like Rodrigues (2018, p. 161), as a large-scale external evaluation. As the author points out, it is conceived externally to the school, has a wide extension and, similarly to Saresp, it “suggests a deliberate policy of prescribing pedagogical work”.

3In 2019, we had the approval of Resolution CNE/CP number 2, of December 20, 2019, which revoked Resolution 2/2015 (BRASIL, 2020). However, it is worth mentioning that the hours allocated to the supervised internship remain the same. The 2015 resolution was cited as the current PPC was built considering such a guideline.

4Of the 19 undergraduates who were, in the second half of 2019, performing the first stage of the supervised internship of that course, only one did his internship at a municipal school in a city in the interior of Minas Gerais. The others developed the internship in schools in the state network of São Paulo.

5When necessary, we corrected the words/phrases and the ABNT norms without changing the content of the messages. All fragments of the reports were selected considering their potential to exemplify the phenomenon analyzed. The 19 undergraduates authorized the use of their reports for the production of this article.

7Such assessment aims to “support the actions developed by schools, improving student learning, applying tests in the 5th and 9th grades of Elementary School and in the 3rd grade of High School [...]. The ADC has as a reference the skills focused on the national assessment, which students are expected to have developed in Portuguese and Mathematics, at the time of the school career object of the years/grade assessed”. Available in: <https://decentro.educacao.sp.gov.br/senhores-diretores-e-professores-coordenadores-avaliacao-diagnostica-complementar-adc-orientacoes-sobre-a-aplicacao/>. Accessed on: 06/09/2021.

8The Management in Focus Program uses the MMR, as stated on the website of the State Department of Education. Available in: https://www.educacao.sp.gov.br/gestaoemfoco. Accessed on: 06/11/2021.

9This assessment takes place within the scope of the PEI and can be understood as part of the “new strategies aimed at controlling the work of professionals working in the PEI, arising from the business model” (VENCO; MATTOS, 2019, p. 382).

Received: October 10, 2021; Accepted: May 05, 2022

texto en

texto en