Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 10-Sep-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469826627

ARTICLE

INCLUSION OF STUDENTS WITH INTELLECTUAL DISABILITIES: RESOURCES AND DIFFICULTIES OF FAMILY AND TEACHERS

1Faculdade de Filosofia Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo (USP). Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brasil.

Educational inclusion is based on the principle that all students should learn together, in regular schools, regardless of their differences. The family-school partnership is an important factor associated with the success of inclusion. This study aimed to verify how the inclusion process of students with intellectual disabilities occurs, by identifying resources and difficulties, according to information provided by parents and teachers. This is a qualitative and cross-sectional study. Semi-structured interviews were done with 42 parents and 34 teachers of 44 students diagnosed with intellectual disabilities enrolled in regular public schools in a city in the interior of Minas Gerais. The data were analyzed in the Iramuteq software. Five classes were obtained by the parents’ interview: Family context, resources and parents' difficulties; Relationships with the school; Participation in schooling; Children's difficulty; and Path of diagnosis and follow-ups. Likewise, five classes in the analysis of the teachers' information: Understanding the inclusion process; School-family relationship; Difficulties in the inclusion process; Teachers' practices within the classroom; and Student development. The classes comprise themes related to the perception of participants. Parents pointed out difficulties in providing support to their children in the face of school adversities and as resource support in their relationship with the school. The teachers pointed out daily difficulties in the inclusion process and problems in the family-school partnership. It was possible to provide indicators of aspects of the inclusion process to provide subsidiary functions in this context.

Keywords: educational inclusion; intellectual disability; parents; teachers; school

A inclusão educacional tem como princípio que todos os alunos devem aprender juntos, em escolas regulares, independentemente das diferenças. A parceria família-escola é um fator de suma importância para o sucesso da inclusão. O presente estudo teve como objetivo verificar como está ocorrendo o processo de inclusão de alunos com deficiência intelectual, identificando recursos e dificuldades, de acordo com responsáveis e professores. Trata-se de um estudo qualitativo, de corte transversal. Foram realizadas entrevistas semiestruturadas com 42 responsáveis e 34 professoras de 44 alunos com diagnóstico de deficiência intelectual matriculados em escolas regulares da rede pública de uma cidade do interior de Minas Gerais. Os dados foram analisados com auxílio do software Iramuteq e a técnica de análise de conteúdo temática. Obtiveram-se cinco classes na análise das entrevistas dos responsáveis: Contexto familiar, recursos e dificuldades dos pais; Relações com a escola, Participação na escola, Dificuldades dos filhos, Percurso do diagnóstico e acompanhamentos; e cinco classes na análise das entrevistas das professoras: Entendimento do Processo de Inclusão, Relação escola-família, Dificuldades no processo de inclusão, Práticas das professoras dentro da sala de aula e Desenvolvimento do aluno. Tais classes compreendem temas relativos às percepções dos participantes. Responsáveis apontaram dificuldades quanto a prestar apoio aos filhos diante das adversidades escolares e, como recurso, o apoio na relação com a escola. As professoras apontaram dificuldades cotidianas no processo de inclusão e problemáticas na parceria família-escola. Através das entrevistas, foi possível prover indicadores de aspectos do processo de inclusão de forma a subsidiar intervenções nesse contexto.

Palavras-chave: inclusão educacional; deficiência intelectual; pais; professores; escola

La inclusión educacional se basa en el principio de que todos los estudiantes deben aprender juntos, en escuelas regulares, independientemente de las diferencias. La asociación familia-escuela es un factor muy importante para el éxito de la inclusión. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo verificar cómo se está produciendo el proceso de inclusión de estudiantes con discapacidad intelectual, identificando recursos y dificultades, según padres y profesores. Se trata de un estudio cualitativo y transversal. Se realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas a 42 padres y responsables y a 34 maestras de 44 estudiantes diagnosticados con discapacidad intelectual matriculados en escuelas públicas regulares de una ciudad del interior de Minas Gerais. Los datos se analizaron utilizando el software Iramuteq y la técnica de análisis de contenido temático. Se obtuvieron cinco clasificaciones en el análisis de las entrevistas a los responsables: Contexto familiar, recursos y dificultades de los padres; Relaciones con la escuela, Participación escolar, Dificultades de los niños y Ruta de diagnóstico y seguimiento; cinco clasificaciones en el análisis de las entrevistas a los docentes: Comprensión del proceso de inclusión, Relación escuela-familia, Dificultades en el proceso de inclusión, Prácticas de los docentes dentro del aula y Desarrollo estudiantil. Las clasificaciones comprenden temas relacionados a la percepción de los participantes. Los padres señalaron dificultades para brindar apoyo a sus hijos frente a las adversidades escolares y como recurso de apoyo en su relación con la escuela. Los docentes señalaron dificultades cotidianas en el proceso de inclusión y problemas en la alianza familia-escuela. A través de las entrevistas, fue posible brindar indicadores de aspectos del proceso de inclusión para apoyar las intervenciones en este contexto.

Palabras clave: inclusión educativa; discapacidad intelectual; padres; maestros; escuela

INTRODUCTION

Educational inclusion has a fundamental principle that all individuals should learn together in regular schools, regardless of difficulties and differences (Unesco, 1994). In Brazil, there is the Special Education teaching modality, which permeates all levels, stages, and modalities, guaranteeing the education of students with disabilities, autistic spectrum disorder, and high abilities/giftedness in the regular education system (Brasil, 1996, 2008). Therefore, the term “Educational Inclusion” has a broad, political, and social meaning, while the term “Special Education” defines the type of education. This study focuses on the Special Education modality, from the perspective of Inclusive Education.

The Brazilian history of the education of people with disabilities in regular schools gained greater visibility in the late 1980s and early 90s, through the signing of international declarations and the establishment of guidelines, public policies, and national laws. In 1988, the Federal Constitution (Brasil, 1988) and, in 1990, the Statute of the Child and Adolescent - ECA (Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente) (Brazil, 1990) - guaranteed to all citizens, and specifically to children and adolescents, equal rights and stay in school. In 1994, the Salamanca Declaration on “Principles, Policies, and Practices in the Area of Special Educational Needs”, stated that students with disabilities should learn in an inclusive system (Unesco, 1994). In 1996, the Law on Education Guidelines and Bases - Law nº 9,394 - was published, dealing in chapter V with Special Education in the regular school system (Brasil, 1996).

In the 21st century, in 2008, the National Policy on Special Education from the Perspective of Inclusive Education was edited, with the objective of access, participation, and learning for students with disabilities in regular schools, guaranteeing specialized educational service (SES); the training of teachers and other education professionals; family and community participation; architectural accessibility, transport, communications and information; and the articulation and implementation of public policies (Brasil, 2008). The SES aims to organize pedagogical and accessibility resources for the full participation of students, considering their specific needs to complement and/or supplement training, articulating with the pedagogical proposal of common education (Brasil, 2008). In 2015, the Brazilian Law for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities was enacted, Law nº 13.146/2015, which emphasizes education in an inclusive system for all levels and learning to achieve the maximum possible development (Brasil, 2015).

We observe that Special Education is aligned with the perspective of inclusive education by conceiving that at school each student is attended to according to their needs and difficulties, with resources and methodologies that provide their development and learning (Miranda, 2001), understanding that the Educational inclusion brings at its core the acceptance of differences, the transformation of the education system, the training of teachers, cooperation between students and, above all, respect for dignity (Moreira, 2006).

When thinking about the education of students with intellectual disabilities, adequate pedagogical action is necessary to meet specific educational needs. It becomes important, in addition to knowledge about the teaching-learning process, knowledge of conceptions of disability to outline relevant educational strategies (Lopes & Marquezine, 2012). The American Association of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD) proposes a multidimensional, functional, and bioecological conception, understanding it as a disability characterized by significant limitations in intellectual function and adaptive behavior, which is composed of social and practical skills (AAIDD, 2010). The literature points out that, in addition to cognitive development and formal learning, other ways of knowing should be developed in students, stimulating affective and social development, and respecting the specific way in which each one deals with learning (Santos, 2012; Batista & Enumo, 2004).

It is important to highlight that inclusive education implies a change in the educational perspective, and should reach all school elements (Unesco, 1994; Brazil, 2008; Carvalho, 2019). Thus, students, families, teachers, managers, and other professionals involved must have a joint action, which constitutes an important resource. Studies indicate the importance of the family-school relationship for educational inclusion, through an appreciation and active participation of parents/guardians, collaborative work daily, and effective communication with the exchange of information (Borges, Gualda & Cia, 2011; Christovam & Cia, 2013; Brandão & Ferreira, 2013; Benitez & Domeniconi, 2012; Vilaronga & Mendes, 2014). Family and school are distinct, complementary, and essential educational sources in the transmission of knowledge and development assistance, in which shared partnership and joint strategies benefit the educational process (Dessen & Polonia, 2007; Marturano & Elias, 2016).

About the role of the family, it is necessary to understand different issues, both subjective and objective. The way families will deal with their children's school inclusion depends on several aspects, such as life history, social network support, communication skills, and own resources, among others. Education professionals involved in the inclusion process must be attentive to the expectations and desires of families so that they can help them and carry out joint interventions (Luiz & Nascimento, 2012). It must be considered that families face many difficulties in their experiences, which permeate affective and concrete issues, such as little information about the diagnosis and children's rights in the school, difficulties in dealing with necessary adaptations, constant visits to doctors and follow-ups, adversities in reconciling work and child support, lack support, among others - issues that will interfere in the dynamics of the educational inclusion process (Cerqueira, Alves & Aguiar, 2016; Rosário & Silva, 2016).

The role of teachers is another essential element. Initial and continuing education is identified in the literature as central so that these professionals can promote transformations and effect inclusion (Matos & Mendes, 2015; Silveira, Enumo & Rosa, 2012; Tavares, Santos & Freitas, 2016; Vilaronga & Mendes, 2014). However, there are several difficulties that teachers face, such as the lack of institutional support, the little interaction with teachers in the resource room, the lack of materials and assistive technology (Silveira et al., 2012), in addition to problems in the training that will impact the conceptions and practice of inclusive education (Garcia, 2013; Kassar, 2014; Silva & Carvalho, 2017). It is understood that teachers need, in their work, the support of specialized professionals, the family, and the entire school community (Matos & Mendes, 2015; Sant’Ana, 2005).

Despite the evident benefits of inclusive education, and the advances in recent years and legal bases (national and international), what is still observed is a great contradiction between what is determined and what happens in practice (Borges & Campos, 2018; Gomes & Souza, 2012; Tavares et al., 2016). Although there is an increase in enrollments of students with disabilities in schools (Rebelo & Kassar, 2018), with a high concentration in the early years of Elementary School, there is still a low number of enrollments in High School, which shows the dropout present in this path (Meletti & Ribeiro, 2014). Thus, a series of questions emerge about the inclusion process, involving processes of learning, assessment, curriculum structuring, didactics, specialized support, school management, and accessibility of schools (Rahme, Ferreira & Neves, 2019). Inclusive education comes up against the relationships, attitudes, and beliefs of those involved, the failures of professional training, the lack or inexistence of materials and resources, and the physical and architectural structure - in addition to what involves the institutional organization of schools, the system education, laws, and public policies. These issues and other difficulties experienced by teachers, managers, parents, and students end up limiting and muzzling the inclusion proposal (Carvalho, 2019; Gomes & Souza, 2012; Santos, 2012; Santos & Martins, 2015).

In this scenario, studies that seek to understand the process of educational inclusion integrally and from the perspective of the different actors involved are relevant, seeking to understand, in addition to the difficulties experienced, the resources that these actors find to face adversity. It should be noted that resources and difficulties are aspects and/or processes (concrete, subjective and relational) that act to promote or hinder the inclusion process. The influence of context is highlighted, emphasizing that difficulties can act as risk factors for development, which are directly related to the environment and how people behave in it (Rutter, 1999; Lisboa & Koller, 2011). In the school years, both the family and the school are contexts in which risk and protection mechanisms for developmental trajectories operate (Marturano & Elias, 2016). Thus, this work sought to verify how the process of inclusion of students with intellectual disabilities is occurring, identifying resources and difficulties, according to guardians and teachers.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were 42 guardians and 34 teachers of 44 students diagnosed with intellectual disability, enrolled in Elementary School, in 14 regular public schools in a city in the interior of Minas Gerais. As for those responsible, 40 were mothers, one father, and one grandmother; the mean age was 34.25 years (SD= 6.59); 42 (85%) and they had incomplete Elementary School; 42.85% declared they were currently employed, and 45.24% were in the D-E economic class with an average family income of R$708.19 (according to Brazil's economic classification criterion). Two mothers had two children diagnosed with intellectual disabilities.

As for the participating teachers, 12 taught in municipal schools, 21 in state schools, and one in both networks. Of these, 67.5% had training in Pedagogy; 44.12% had specialization in inclusive education; 47.09% belonged to economic class B2, with an average household income of R$5,363.19 (according to the Brazil criterion of economic classification); the mean age was 42 years (SD = 9.15), with a mean time in the profession of 16.27 years (SD = 7.68). Nine teachers had more than one student with intellectual disabilities in the classroom.

As for the students, there were 30 boys (68.18%) and 14 girls (31.82%), with a mean age of 9.68 years (SD=1.62). Four students attended the 1st grade, five were in the 2nd grade, 11 in the 3rd grade, 15 in the 4th grade, and nine in the 5th grade. Of these, 17 (38.64%) studied in municipal schools and 27 (61.36%) in state schools. As for the diagnosis, 24 (54.55%) had a diagnosis of mild intellectual disability, 7 (15.90%) moderate, 3 (6.82%) severe, 2 (4.55%) profound, and 9 (20.45%) had a diagnosis of unspecified intellectual disability.

Instruments

Teachers and guardians answered a semi-structured interview, a questionnaire to survey sociodemographic variables, and the Critério Brasil Questionnaire (ABEP, 2018). The semi-structured interview, according to Tavares (2007), consists of questions in sequence, which allows for greater reliability, as the interviewer has the necessary means to obtain the information he needs and achieve his goals, but without limiting the informant.

The interview with guardians consisted of questions aimed at understanding how they experienced and what they understood about the inclusion process, as well as identifying resources and difficulties, understanding the relationship with the school and the child's development in terms of school progress. As for the interview with the teachers, this was composed of questions that sought to understand the inclusion process and the ways of dealing with inclusion daily, as well as the resources and difficulties encountered.

Ethical aspects

In compliance with ethical legislation, the project was submitted and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto of Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, approved with CAAE: 86636918.9.0000.5407.

Data collection procedure

Data were collected in a medium-sized city in the interior of Minas Gerais, in five municipal and nine state schools. Initially, we contacted the principals of these schools to survey possible participants. Subsequently, the respective contacts were made (parents by phone, and teachers in person); after acceptance, the day and time were individually scheduled to provide explanations about the study, present the informed consent term and carry out the interview. The meetings took place in schools, in appropriate rooms, lasting approximately fifty minutes.

Data analysis procedure

Initially, the interviews were transcribed in full and transferred to the Iramuteq software - Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires (Ratinaud, 2009). It is open-source software, licensed by GNU GPL (v2), using the statistical environment of the R software. Iramuteq performs analysis of textual data, through lexical analysis, that is, it allows the use of statistical calculations on variables essentially qualitative (Lahlou, 1994). Thus, it is possible to analyze the structural and content characteristics of texts based on the vocabulary used (Salem, 1986); trends, regularities, and patterns of associations (between words, expressions, and concepts) are identified, reducing the material and organizing the data cluster (Leblanc, 2015). It works with the concept of “corpus”, “texts” and “text segments”; in the case of interviews, the “corpus” is the set of all interviews; the “text” corresponds to each interview separately, and the “text segments” are parts of the text (divided by the software). When inserting a corpus into the software, it must have a rate of 75% to be considered suitable (Camargo & Justo, 2013).

Iramuteq performs different types of analyses. In this work, the analysis called Method of Descending Hierarchical analysis (DHA) or “Reinert Method” will be presented. DHA performs cluster analysis on text segments; they are classified according to vocabulary - reduced forms (lemmatized words/root of words) (Camargo & Justo, 2013; Salviati, 2017). Therefore, classes are formed by text segments and words, which are significantly associated with the class, through chi-square calculations having the significance of p<0.05 and X² > 3.80 (Salviati, 2017; Camargo & Justo, 2013). It aims to obtain stable and definitive classes of text segments that, at the same time, a present vocabulary similar to each other and different from the others (Camargo & Justo, 2013). The program presents a dendrogram, with the hierarchical scheme of the classes, which illustrates the relationship between them and presents the list of lemmatized words (reduced forms).

In the interpretation of DHA, it is possible to name and describe the classes, inferring which idea the textual corpus conveys (Camargo & Justo, 2013). It is based on the principle of lexical proximity, in which words used in a similar context are associated with the same lexical world and are part of common ideas (Salviati, 2017). For this reason, DHA is used to identify underlying themes in a set of texts (Souza et al., 2020).

At this point, with the description of the classes, the contextualization of words, and text segments, thematic content analysis is carried out (Nascimento & Menandro, 2006). In this analysis, the text is broken down into categories, according to analogical regroupings (Minayo, 2008). According to Nascimento and Menandro (2006), content analysis can be used in an analogous and complementary way throughout the process and, especially, in the last stages. Minayo (2008) describes them as identifying, through inferences, the nuclei of meaning pointed out by the parts of the texts in each class of the classification scheme and elaborating an interpretative synthesis, through an essay that can dialogue with the themes created, with the objectives, questions, and assumptions of the research.

Iramuteq also provides another form of data presentation provided by DHA, which is Correspondence Factor Analysis (CFA), in which, at a factorial level, it is possible to visually analyze the distribution and organization of classes and the most significant words. This allows analyzing which classes complement and concentrate the corpus and which ones are distant from the center, showing a certain specificity.

The use of the software is justified, as it allows the analysis of a lot of materials through the rigor of a large number of functionalities and tools for the analysis of textual data. It is noteworthy that the software helps the researcher's work, but does not take the role of naming, understanding, and interpreting the contents (Camargo & Justo, 2013; Sousa et al., 2020).

RESULTS

The results will be shown in two parts: the first refers to the analysis of the interviews with those responsible, and the second, to the analysis of the interviews with teachers.

The inclusion process for guardians

The general corpus consisted of 42 texts (interviews); 25,159 occurrences emerged (words, forms, or expressions); there was separation into 731 text segments (TS), using 577 TSs (78.93%), which is considered satisfactory. Through the Method of Descending Hierarchical Analysis (DHA), five classes were obtained; from the analysis of the TSs and the most significant words, it was possible to interpret, name, and give meaning to the classes. Figure 1 shows the dendrogram obtained:

Source: Prepared by the Authors.

Five classes arising from text segments (class rectangles 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5); in each class % of representation in the corpus; class name; Word (most representative); f = word frequency; X²= chi-square, word association with class.

Figure 1 Dendrogram of the Descending Hierarchical Analysis (DHA), of the textual corpus of the interview with guardians

Through Figure 1, we observe the division into the five classes, the percentage of each class in the corpus used, the names assigned, and the ten most representative words, with the frequency and value of the chi-square (X²) (which shows the strength of the word's connection with the class). In the division, there were four ramifications: the first gave rise to Class 5 and subdivided Classes 1, 2, 3, and 4; the second subdivided class 4 and classes 1-2-3; and the fourth subdivided class 1 and classes 2-3. Class 1 (red - Family context, resources, and parents' difficulties) is noted with 102 TSs out of 577 TSs, which represents 17.68% of the corpus used; Class 2 (gray - Relationships with the School) with 112/577 (19.41%); Class 3 (green - Participation in school) with 73/577 (12.65%); Class 4 (blue - Children's difficulties) with 150/577 (26%); and Class 5 (purple - Path of diagnosis and follow-up course) with 140/577 (24.26%). Figure 2 shows the correspondence factor analysis (CFA):

Source: Iramuteq.

Five classes (blue - Children's difficulties; red - Family context, resources, and parents' difficulties; gray - Relationships with the school; green - Participation in the school; and purple - Path of diagnosis and follow-ups) are represented in a factorial plan given by the analysis of the CFA

Figure 2 - Correspondence factor analysis (CFA) of the classes obtained in the descending hierarchical classification of the guardians' corpus.

Through Figure 2, we observe the classes represented in the factorial plane, which are in a centralized segment expanded to more distant points. Thus, Class 5 (purple - Path of Diagnosis and follow-up course) occupies a different quadrant from the other classes, of which Class 4 (blue - Children's difficulties) is further away, while Class 1 (red - Family Context, Resources, and Parental Difficulties), Class 2 (gray - Relationships with the School) and Class 3 (green - School participation) are closer. Next, a detailed description of each of the classes presented will be made.

Class 1: Family context, resources, and parents' difficulties

In this class, those responsible talked about the context and family relationships, in everyday life at home and in situations involving the school and educational aspects. They talked about how they organize the family environment, such as imposing rules and limits. They also spoke about the issue of providing support to their children; in this sense, they reported finding difficulties in helping with school tasks and the lack of time available in the face of the workday. They expressed how they feel in the face of adversity and overload experiences; however, on the one hand, some parents find resources, and, on the other hand, those who have more difficulties. Below are examples of some speeches (text segments of the class) that illustrate the general content of the class:

I let him watch some television, and at bath time he will take a shower. At home, everything has a schedule (Guardian 30).

Then when I don't know, I ask my neighbor's daughter to help me do it because I only studied until fifth grade, then she helps a lot. 39. I say go to the neighbor, ask her to help you. When I don't have her, I send her to my sister-in-law's house (Guardian 39).

When I'm working in the fields, time is short, it's fast, I leave at night and arrive late, my husband always helps the c. 42. He understands a little more, he helps (Guardian 41).

I think I could organize more and take some time to study with them, I think it's time for me to do that because I always say I'm going to do it and I don't (Guardian 20).

So, there's no rest, I was already very overloaded, and ends up leaving us a little helpless for us to act with our lives. I put God in front of everything, I ask God to help me (Guardian 9).

Class 2: Relationships with the school

In this class, the relationship with the school was the main theme, in which the parents said they had a satisfactory relationship, especially with the teaching staff. Almost unanimously in the corpus, this relationship was positive, often assessed by their presence at school and by the fact that they attended meetings or whenever they were called. The parents also spoke about the student-school relationship, in which they generally evaluated that their children feel good and included. However, when questioned, they do not know what educational inclusion is.

Good, too, thank God, good relationship with the school, all her teachers are nice. She feels good, she doesn't complain. I don't know what inclusion means (Guardian 3).

I always pick it up and take it, whenever you call me I go, I'm always here, so it's easy. The relationship with the teachers is good. He feels good at school, he feels included (Guardian 31).

When there's a meeting, like, I come, right, I'm always here, I have a good relationship with teachers. She feels good, she is included (Guardian 8).

I never had a problem at school. He feels good at school, and seems to feel very comfortable with his classmates, and with the teacher, he even likes her a lot (sic) (Guardian 32).

Class 3: Participation in school

Parents spoke more specifically about situations involving the family and school. Thus, they put themselves as participatory and present, highlighting good communication. Also, they said that they talk to their children in the face of conflicting situations that occur in everyday school life, seeking to help them and remedy these conflicts. It could be observed, through the reports, that parents see the school as important and as a resource in the development of their children.

The school always calls me and I answer. Many times, the principal calls me and says that he needs to talk to me, that c. 44 is making a mess, then I come to see what is happening (Guardian 42)

I come to school every day, whenever I need to because c. 30 needs a lot... like us who are mothers, who are “special”, we have to go after them to be able to help them (Guardian 30).

Something happens and I talk to him because the school is the boy's second home. Every time I come, I try to solve it, talk. Only this last teacher I didn't have many relationships with (Guardian 37).

I tell him that school is not boring. Sometimes, poor thing, he happens to get angry when he says he's going to drop a bomb at school, because he hears that, I even talked about it at school, but I say he can't say that (Guardian 26).

Then I bring her, when I'm at home I bring her. I ask the teacher how she is at school and the activities. Her teacher explains to me that she works differently with her than other students (Guardian 1).

This school is the best for his case, if he went to another school it wouldn't be so good. The school responded quickly when he needed a support teacher, which was good for him (Guardian 31).

Class 4: Children's difficulties

In class 4, the children's difficulties were reported, concerning the development of learning, in addition to what the guardians do to be able to help, showing personal resources.

Very difficult for him to read simple words, only two-syllable words, if there's an "r" or "m" in the middle he can't handle it anymore. Writing, he writes well, he has difficulty, but he writes what the teacher says (Guardian 22).

She doesn't have it easy, it's more difficult she doesn't know how to read, to write she writes very wrong, her name is... her name she doesn't know how to write it right. In mathematics, it is very bad too (Guardian 19).

When I see that he is having difficulty with something in the room, I have the notebook at home, you know, then I copy it in the dotted notebook for him to go over and practice (Guardian 42).

I read with him, I help him with his homework, he does it right... when he doesn't have to, we do something for him to write (Guardian 29).

In the same class, in addition to pointing out their children's difficulties, parents also showed the difficulties and challenges they encounter when trying to provide help. These challenges refer mainly to teaching, as they reported that they do not have enough training to do so, highlighting the associated feelings. Another challenge pointed out was the lack of time and not knowing how to deal with the behavior of the children in situations in which they need to help them.

No, I don't think I help her to develop, because I have little reading, right? And I didn't learn to read and write properly, I only know the basics, I stopped studying (Guardian 1).

No, at home I don't do anything to help, because I'm also illiterate, so I don't have much to teach, because I know very little (Guardian 41).

The problem is that I tell them to try on their own because it hurts my heart that I don't have reading, it hurts my heart when they ask me to help them, but I don't have reading, there's no way (Guardian 40).

I help as much as I can, but every weekend I'm at home she goes to school, so she doesn't find her. I think the lack of patience, she doesn't have patience, then she gets very critical and nervous, then it gets in the way for us to help her (Guardian 21).

Class 5: Path of diagnosis and follow-ups

Those guardians spoke specifically about the course of the diagnosis and how they discovered their son's disability. The follow-ups performed at the time were also presented; the Association of Exceptional Parents and Students (APAE- Associação de Pais e Alunos Excepcionais) is often mentioned in the speech, as a place to identify the diagnosis and follow-up.

Then at the end of the year, I took her to APAE, then she went to the psychologist, speech therapist, and everything there. Then she said that she has an intellectual disability. So, this year she has no vacancy (Guardian 19).

I took him to APAE and they said it was an intellectual disability. He's a quiet kid, doesn't like to play with other kids, and doesn't talk much. Today he is monitored at APAE, he goes every Friday and does not take medication (Guardian 25).

I took him to the neuro pediatrician, then he was already prescribed medication for ADHD, then later he did a cognitive test and proved that he has a cognitive deficit, with an intellectual disability. Today he is monitored, I take him every six months to the Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (UFU) (Guardian 26).

At the age of three, c. 27 studied at the daycare, then APAE went there and asked to take him there. Then I took him, then they said he needed to follow up there to see what he had because he had a different behavior (Guardian 27).

ICD 70.8, is a mild mental problem, I found out there is little in APAE. She went to daycare, then they saw that she had difficulty and sent her to APAE (Guardian 11)

The inclusion process for teachers

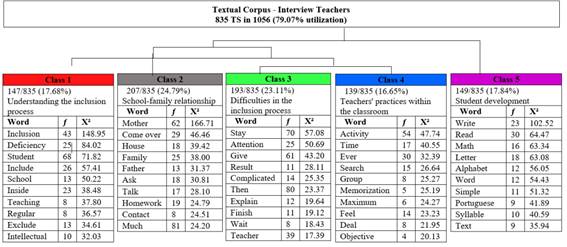

The general corpus, constituted by the teachers' interviews, consisted of 34 texts, separated into 1,056 TSs, with the use of 835 of these segments, a percentage of 78.93%, considered satisfactory. There were 37,048 occurrences (words, forms, or expressions). In the Method of Descending Hierarchical Analysis (DHA), five classes were obtained, as shown in Figure 3:

Source: Prepared by the Authors.

Five classes arise from text segments (class rectangles 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5). In each class % of representation in the corpus; class name; Word (most representative); f = word frequency; X²= chi-square, word association with class.

Figure 3 Dendrogram of the Descending Hierarchical Analysis (DHA) of the textual corpus of the teachers' interview

Figure 3 shows the division into the five classes, the percentage of each class in the corpus, the names assigned, the ten most representative words, the frequency in the class, and the chi-square value (X²). As with the corpus of those responsible, there were four ramifications: the first gave rise to Class 5 and subdivided into Classes 1, 2, 3, and 4; in the second, on one side was class 2 and, on the other, classes 1-3-4, in which there was the third subdivision into class 1 and fourth into class 3-4. Class 1 (red - Understanding of the Inclusion process) is observed with 147 TSs out of 835 TSs, which represents 17.68% of the corpus used; Class 2 (gray - School-family relationship), with 207/835 (24.79%); Class 3 (green - Difficulties in the Inclusion Process), with 193/835 (23.11%); Class 4 (blue - Teachers' practices within the classroom), with 139/835 (16.65%); and Class 5 (purple - Student development), with 148/835 (17.84%). Figure 4 presents the factor analysis of correspondence (CFA):

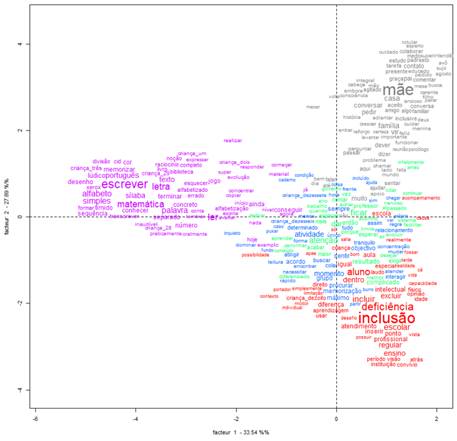

Source: Iramuteq.

Five classes (purple - Student Development; gray - School-family relationship; green - Difficulties in the inclusion process; blue - Teachers' practices within the classroom; red - Understanding the Inclusion Process) are represented in a factorial plan through analysis of the CFA.

Figure 4 - Correspondence factor analysis (CFA) of the lexical classes obtained in the descending hierarchical classification of the guardians' corpus.

Figure 4 shows these classes represented in a factorial plane; the words of all classes are presented in a centralized segment that expands to more distant points; class 5 (purple - Student development) occupies a different quadrant from the other classes, as does class 2 (grey - School-family relationship). The other classes are closer, while class 1 (red - Understanding the Inclusion process) is further away from classes 3 (green - Difficulties in the Inclusion Process) and 4 (blue - Teachers' practices within the classroom). Next, a detailed description of each class will be presented.

Class 1: Understanding the Inclusion process

In this first class, the teachers talked about their understanding of the inclusion process. This understanding permeates the idea that inclusion is more than just inserting the student with a disability in a regular classroom, requiring something more to be done so that they can develop and be included. The teachers showed a theoretical understanding of what educational inclusion is and recognized the discrepancy with the practical reality.

From what I understand about school inclusion, we have to try to include in our daily life that student who has some difficulty, or some disability, but really include it and not put it there just to make a number, without doing anything for that student (Teacher 8).

Inclusion is not only inserting the student into the school but also creating the possibility for development within what he can (Teacher 27).

Every child who has a certain learning disability has the right to attend school normally, right? And we, we teachers, have a double work because we work with them differently (Teacher 1)

So that's where I think inclusion is not happening, right, because just throwing the student inside the classroom is not enough. For us to work on inclusion, we would have to have this service with the student, for him to be developing his skills (Teacher 2).

Class 2: School-family relationship

This class is formed by teachers' reports about the relationship the school, as a whole, has with families and how this impacts the development, learning, and inclusion of students. These reports are divided into families that are not present and do not help their children, and families that are present and able to provide the necessary support. However, the teachers talked about families that are absent and that have internal family problems, which impact the development of their children.

I have another one who has a little difficulty, but the mother already supports everything, so she comes to the support classes and she has improved a lot (Teacher 3).

They participate together, and accept, right, the mother who is always closer to us, because she is the one who seeks, and collaborates with us (Teacher 5).

This difficulty can also be related, a lot, to the family structure, because we perceive the environment we live in, so I think this can interfere a lot. We realize that the mother, sometimes, does not have a firm grip on him to do his homework (Teacher 32).

She has to take care of her things... it seems that even her home is a mess. Her problem, I think, is the family, her mother doesn't solve it, but her father already tries to solve it a little. Her intellectual problem is easier for me, it's the psychologist and psychiatrist (Teacher 7).

The other, in my opinion, if she had support, if someone sat with her, she would teach literacy. to c. 7, even, though I talked with her mother. She doesn't give that support by coming to the support class in the morning (Teacher 3).

Class 3: Difficulties in the Inclusion Process

In this class, the teachers brought reports about the greatest difficulties experienced in the process of inclusion of their students, which involve day-to-day problems, such as giving equal attention to the student with a disability and the rest of the class, reconciling more individualized and the lack of a support teacher. Another point is the lack of structural support from the school or the implementation of public policies that would guarantee support from professionals in the common rooms.

I think what makes it more difficult is the lack of support and structure because it turns out that we don't have time. I can't give him the total attention he needs. I have 26 children (Teacher 25).

There is a room that has two or three students with this difficulty, so, for the teacher to be working without support, is a little complicated, because it often requires a separate plan. Putting it down on paper is easy, the hard part is putting it into practice (Teacher 2).

It bothers me and it bothers the whole room. And I end up getting angry with him for that because I can't give him the necessary attention because I need the rest of the class to learn (Teacher 1).

His learning is hampered by the lack of a support teacher because I have to take care of the whole class and he needs special attention (Teacher 11).

Class 4: Teachers' practices within the classroom

In class 4, the practices that teachers use in their daily life in the classroom were discussed, which includes the resources used, such as specific, individualized activities and adapted to the needs of students with intellectual disabilities. Another resource is working in pairs or groups so that students with disabilities can be helped by their classmates.

A job focused on his needs, on the skills he already mastered and needs to improve. So, I work on specific activities for him, but also activities integrated with the class for him, too, to feel that he is interacting with all his colleagues (Teacher 9).

It's a challenge, we have to always be looking to learn a little more, and look for different activities (Teacher 8).

Try to work activities so that he can get involved and develop according to the stage he is in... he has to adapt, he has to change, he has to work according to the child's level and seek material that meets what he needs (Prof. 9).

There are always those students with whom they have an affinity and who sit together, they do everything, and it will depend on who you put them with (Teacher 6).

Class 5: Student Development

Finally, in this last class, the teachers reported the difficulties and the student's development. The difficulties refer to learning issues with writing, reading, and mathematics, in which what is done with these difficulties is also mentioned (similar to class 4). The participants also addressed the evolutions that the students had during the joint teacher-student work.

She doesn't read, doesn't identify the alphabet, just a few letters. It seems that there are days when she knows more, other days less, like forgetting. She cannot add syllables, she can speak if I help and pronounce them (Teacher 29).

I give her activities more working on the alphabet, but everything with capital letters, she can't do anything cursive, she can't do anything with her full name without the form (Teacher 1).

But in mathematics, now that we are knowing the numbers, after thirty she counts to almost a hundred, but she doesn't know all the numbers yet. So, her lesson plan is separate (Teacher 6).

She didn't express herself very well, but now she's more expressive. At the beginning of the year she was reading simple syllables, today she has already started to read simple sentences I think she has had a significant evolution (Teacher 30).

She always told him to think the way she could. It was an ant job, little by little. Now she can write simple words, form sentences can write the entire name (Teacher 32).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to verify how the process of inclusion of students with intellectual disabilities is occurring, identifying resources and difficulties, according to guardians and teachers. Firstly, there will be a discussion of the inclusion process for guardians, later, the inclusion process for teachers will be discussed; finally, discussions will be held on the family-school relationship.

The inclusion process for those responsible

The analysis of the interviews with the guardians resulted in five classes: Family context, resources, and parents' difficulties; Relationships with the school; School participation; Children's difficulties; Path of diagnosis and follow-ups. These classes express the parents' experiences and understandings regarding the resources and difficulties of the school inclusion process.

Class 1 (Family context, resources, and parents' difficulties) points out that the issue of disability permeates daily life, family relationships, and how families organize themselves. Some families manage to establish a routine, impose limits and seek ways to help their children (Guardian 30, Guardian 39, Guardian 41). This fact signals that these families are finding resources and fulfilling their role in supporting the educational process and development of their children (Dessen & Polonia, 2007; Marturano & Elias, 2016). However, there were many difficulties reported, such as lack of time, due to a work routine, which brings feelings of overload (Guardian 20, Guardian 41, Guardian 9). We observed that 42.2% of those responsible worked outside the home, which seems to have an impact on family organization. This need for organization, for managing routine and time, is an inherent issue in the lives of parents of children with disabilities, as they need to align work demands with the needs and attention that their children demand, in addition to having time to monitor medical appointments and other assistance (Cerqueira et al., 2016; Rosário & Silva, 2016). Another reported difficulty consists of helping children with school tasks, which comes up against the education level of those responsible, as mentioned by guardian 39; this issue also appears in Class 4 (Children's difficulty), in which guardians 1, 40, and 41 report inability to care for their children and how difficult it is for them; it was observed that 42.8% of the participants declared incomplete elementary education, showing that a large proportion of these parents did not have a complete training, which makes it difficult to help their children with the development of school tasks, even if they feel this need and are interested in doing it.

These difficulties in reconciling work and supporting their children, the lack of knowledge, and incapacities to assist in school development, require a careful look at not blaming these families, as they involve social and economic issues that are not in the control of the parents (most of the families in economic class D-E). They also awaken to the urgency of approaching the school team, aiming to understand how these families can be helped since parents are key players in the development, involvement, and perception of children with intellectual disabilities in the school. (Coelho, Campos & Benitez, 2017). Therefore, the need for families to have support is evident, including in the sense of empowering them to recognize the importance of their actions. Such support can come from both the school and health professionals (Rosário & Silva, 2016).

Classes 2 (Relationships with the school) and 3 (Participation in the school) show the importance of the relationship with the school environment and how the children feel in this environment. In Class 2, guardians report that their children feel good in the educational environment and are included (Guardian 3, Guardian 8, Guardian 31, Guardian 32), even without knowing how to conceptualize inclusion (Resp. 3), which shows, that once again, a lack of relevant knowledge, which will directly impact the inclusion process and which needs to be worked on (Rosário & Silva, 2016). In Class 3 (Participation in school), they said that they can talk to their children in the face of problem situations (Guardian 1 and Guardian 26), which is important, as it shows that those responsible are concerned and monitor the situations that occur in everyday school life.

In these classes 2 and 3, the family-school relationship is also addressed. Parents reported having a good relationship with the school and teachers, with constant communication, closeness (Guardian 3, Guardian 8, Guardian 30, and Guardian 31), and an interest in knowing how their children are developing (Guardian 1 and Guardian 30). For some, this relationship is assessed by attendance at school, when there is a request, or at meetings (Guardian 8 and Guardian 42). According to the study by Christovam and Cia (2016), most parents of students with disabilities attend school when called and use meetings for contact. However, it is important that communication takes place beyond these moments, in a continuous process; therefore, the importance of systematic and focused interventions to improve this communication is highlighted.

In general, the school was seen positively and as an important protective resource for parents and students, as reported by guardian 31, according to which the school was the best for the child's case, showing the importance of educational inclusion and the need for students with intellectual disabilities to be received with care and dedication by the team (Coelho et al., 2017; Luiz & Nascimento, 2012). On the other hand, the literature shows that the inclusion process is not always seen positively by parents. Maturana & Cia (2015) evaluated 20 studies on the family-school partnership, in which most of the families studied had a negative understanding of the inclusion process, indicating the lack of investments, the discredit given to students, and the non-acquisition of school knowledge.

In Class 4 (Children's difficulties), parents reported their children's adversities at school. They said that their children have many cognitive difficulties (reading and writing) (Guardian 22 and Guardian 19), which may indicate that they probably do not have an understanding of diagnostic issues, as well as limitations that the children may present, since that these difficulties are inherent to disability (Rosário & Silva, 2016). By providing this knowledge, parents tend to have a greater understanding of their children. Studies show that one of the most common needs of parents of children with disabilities is information; therefore, they need to be supported as this information is not always available (Borges et al., 2011; Christovam & Cia, 2013; Cerqueira et al., 2016; Pavão et al., 2016). We could identify resources developed by the parents themselves (Guardian 42 and Guardian 29), which, once again, shows the importance of guidance so that they can seek ways to help their children and face adversity.

Another point to be highlighted is that those responsible understood that their children were not able to develop in the school environment, which shows a flaw in inclusion, which requires interventions for the integral development of students (cognitive and social) (Rahme et al., 2019). At this point, the issue of Specialized Educational Service (SES) can be discussed, as it is the service aimed at working with the individual difficulties and needs of each student, seeking development. Despite being a right of students with disabilities, not all participants attended the service, which explains the non-appearance of this information in a significant way in the general analysis of the interviews. This fact raises the serious problem of the discrepancy between what is established and what happens in practice. It is understood that SES is an important resource for students with intellectual disabilities (Lopes & Marquezine, 2012). Pasian, Mendes, and Cia (2017) discuss the importance of SES, but highlight problems, such as lack of access, which is due to the impossibility of going to school after school hours, insufficient numbers of services in some regions, and structural issues.

In Class 5 (Diagnosis and follow-up course), we observed that the parents faced a long road until the diagnosis of intellectual disability was conceived and that, in general, they sought to provide care and follow-up to support the improvement of the quality of life of the children such as medical follow-ups and at the Association of Special Parents and Friends (APAE). The APAE, in this context, is considered an important resource and appears in the speech of most parents. The institution is currently established as a multi-professional center that provides education, health, and social assistance services to people with disabilities. Luiz and Nascimento (2012) showed that, for parents, the APAE constituted a place of reception, including supporting the process of educational inclusion, in which there was comfort and security by the professionals. Vilaronga and Mendes (2014) emphasize the importance of the specialized institution working collaboratively with the regular school to establish strategies for student learning and development.

In the Correspondence Factor Analysis (CFA) (factorial plan) and the ramifications of the classes, it is possible to understand the relationship between them to confirm the above results. Class 4 (Children's difficulties) is linked and close to Class 1 (Family context, resources, and parents' difficulties), showing that children's difficulties impact daily life and family relationships. Also, Class 1 (Family context, resources, and parents' difficulties) is close and linked to Classes 2 (Relationships with the school) and 3 (Participation in school), which involve the school. This fact shows that the family context, how the family organizes, and how it provides support in the face of difficulties, will directly impact relationships with the school. Class 5 (Diagnosis and follow-up course), despite being linked to all other classes, is further away, showing that there is not such a direct impact, since these follow-ups, although important for development, often do not occur together with the school, due to the difficulty of communication between specialist professionals, family, and school professionals.

These classes can also be analyzed to understand if they comprise resources or difficulties for those responsible. It can be said that Class 1 (Family context, resources, and parents' difficulties) comprises difficulties, with the item's lack of time and education level standing out. Difficulties can lead to coping and consequently to the development of some resources, as reported by guardian 39, who mentioned her difficulties in teaching, not knowing the content, and asking her neighbor or other family members for help (resource found). Class 2 (Relationships with the school) can be understood as a resource, as it shows positive points that the guardians list, such as having a good relationship with the school, with teachers, and the fact that the children feel good. Class 3 (Participation in school) also shows resources by showing that parents have a positive behavior towards school, are present, and accompany and support their children in adversity. Class 4 (Children's difficulties) shows children's difficulties in school development. Some parent resources are highlighted, such as writing and reading training; however, once again difficulties are also evidenced that prevent assistance - therefore, it is a class of difficulty. Class 5 (Diagnosis and Follow-up Path) shows an important resource for those responsible according to their speech; however, as could be seen in the CFA, it is not being a resource in school development.

The inclusion process for teachers

In the analysis of the teachers' interviews, the following classes were formed: Understanding the inclusion process; School-family relationship; Difficulties in the inclusion process; Teachers' practices within the classroom; and Students' difficulties. Such classes correspond to the teachers' experiences and perceptions about resources and difficulties of the school inclusion process that impact the methodologies used to work with inclusion and in the management of students' difficulties.

In Class 1 (Understanding the Inclusion Process), which covers the understanding that teachers have of inclusive education, they said that inclusion is working with students to look at individual needs and seek development (Teacher 27 and Prof. 8). This knowledge is consistent with the theories that support special/inclusive education and with regulations such as the National Policy on Special Education (Brasil, 2008). However, the teachers reported difficulties and problems with the practice of inclusion (Teacher 1 and Teacher 2), mainly in terms of meeting the student's needs. It is known that initial education and training are important factors for effective inclusion (Gomes & Souza, 2012; Garcia, 2013; Tavares et al., 2016). Of the teachers in the study, 44.12% reported having a specialization in inclusive education. Although the issue of teacher training was not an apparent topic in the interviews and the teachers showed knowledge consistent with the guidelines, they still reported practical difficulties in the process, which shows that knowledge is not enough to support teaching practice in inclusion and that teacher training and continuing education are important (Garcia, 2013).. Silva and Carvalho (2017), in a literature review, showed that teachers from common classes are unaware of the inclusion policy, as to the student's abilities and limitations in terms of disability, noting that to carry out their actions, public resources and specialized professionals in the area of special education are needed. Therefore, it is understood the importance of contact between the common room teacher and the special education teacher to support the practice and mitigate the mentioned difficulties. In addition, the teacher's highlight, in their understanding of inclusion, the discrepancy between theory and practice (Teacher 2), understanding how much this impacts the inclusion process (Matos & Mendes, 2015).

In Class 2 (School-family relationship), the teachers addressed the relationship with the family, understanding that there are families that can support their children and that this is important (Teacher 3 and Teacher 5). However, for the most part, there were reports of families unable to accompany their children (Teacher 32, Teacher 7, and Teacher 3), which, according to them, is an impact on inclusion. Teacher 3, who has two children with intellectual disabilities in the classroom, notices differences in families and how the fact brings different results. We conclude that the family close to the school helps in the development of students and the effectiveness of inclusion (Benitez & Domeniconi, 2012; Brandão & Ferreira, 2013). However, absences and lack of support from those responsible are found, which requires intervention (Maturana & Cia, 2015; Santos & Martins, 2015).

Regarding Class 3 (Difficulties in the process), most of the difficulties refer to the lack of support - structural and professional - (Teacher 25, Teacher 2, and Teacher 11). These difficulties are represented in many studies. Silveira et al. (2012), for example, identified the lack of support, a specialized team, resources, and assistive materials as the main obstacles. The presence of negative feelings was also reported (Teacher 21), which may be related to the teacher's unpreparedness to carry out the work from an inclusive perspective (Faria & Camargo, 2018) and to this lack of support, which can generate physical and emotional mental health overload (Melo & Ferreira, 2009). According to Matos and Mendes (2015), the difficulties and demands of teachers in educational inclusion permeate several nuances: the need for psychological care; teacher education and training to understand students' needs; the adequacy of physical, material, and pedagogical conditions; hiring professionals to support the inclusion process, and policies to improve teachers' working conditions. Therefore, we highlight the extreme need for structural interventions and the scope of the implementation of laws and public policies to subsidize this teaching activity and create conditions for effective inclusion.

It is understood that the daily difficulties will affect the work methodologies that are addressed in Class 4 (Teachers' practices within the classroom). The teachers reported that they use methodologies such as adapted and individualized activities to meet the specific needs of students. Teachers, in their inclusive practice, see the need to make methodological, pedagogical, and communicative adjustments for teaching (Silva & Carvalho, 2017); curricula are often adapted, including or excluding content (Santos & Martins, 2015). Another resource used is the mediation of colleagues or activities in pairs, which provide exchanges of experiences and the development of cooperation between students (Costa, Moreira & Seabra Junior, 2015).

Through the approximation of classes 4 and 3 by the CFA, we identified that these practices arise from the difficulties they encounter. Teacher 8 believes it is a challenge to find differentiated activities, and this challenge may be due to the lack of specialized support professionals, such as the special education teacher, to work together. The choice of resources and strategies to be used in the classroom must come from planning (Vilaronga & Mendes, 2014), and it is important that this planning focuses on the student, on their needs, aiming at their development, and that it is not focused on what the teacher can do in the face of their difficulties, as verified by this study. Thus, the importance and effort of teachers in developing activities and resources to include students is highlighted; however, there is a need for collaborative work with a school team composed of special education professionals (SES) to support pedagogical practice and enable guidance, reflection, and discussion of specific issues (Briant & Oliver, 2012; Matos & Mendes, 2015; Silveira et al., 2012; Vilaronga & Mendes, 2014).

In Class 5 (Student development), the teachers highlighted a lot of difficulties in the student's development. Carvalho (2019) argues that the understanding of these difficulties must go beyond the clinical picture of the disability, since many students without disabilities also express learning difficulties due to several factors, such as motivation, and social and intrapersonal conditions, among others. Even if efforts are made to increase learning and the teaching-learning process is as dynamic as possible, school teaching will often not have the potential to bring about certain changes. In this case, the work should focus on skills and not just limitations; it should provide the development of the ability to learn, and not only the apprehension of content, through contextualized situations, adapted curricular content, and the active performance of the student (Batista & Enumo, 2004; Santos, 2012).

Once again, the importance of the SES is highlighted to work with difficulties, enhancing the skills and development of students, being a work articulated with the curriculum, and in constant communication with the teachers of the regular classroom, which would be an important resource (Lopes & Marquezine, 2012). However, not all students participating in this study were attending the service, which shows that the country's laws and policies are not effective, which is a serious problem for educational inclusion (Carvalho, 2019).

In the analysis of the ramifications and the CFA, as mentioned, the impact of daily difficulties in teaching practice can be evidenced, as there is a connection and proximity between classes 3 (Difficulties in the inclusion process) and 4 (Practice of teachers within the classroom); that is, these teachers work according to what is available to them, and the work is organized according to the difficulties they encounter. It is also observed that Class 5 (Student Development) is the most distant, despite being linked to all the others, which can show that the work methodology (in the face of difficulties) is not sufficient to subsidize the development of the students. This fact is confirmed because, despite some teachers reporting student progress (Teacher 30 and Teacher 32), they still mention many difficulties (Teacher 6, Teacher 1, Teacher 29). Class 2 (School-family relationship) is also a distant class, which can be understood given the teachers' reports regarding difficulties and lack of family support. Class 1 (Understanding the Inclusion Process), which talks about the understanding of this process, is also further away from the others, directly linking to Class 3 (Difficulties in the process) and 4 (Teachers' practices within the classroom). This can show that the understanding they have of the process does not match the practice, that is, they know what inclusion is, but this knowledge does not include an effective knowledge of methodologies, therefore, it is not helping in the practice to include, since it is further from class 5 (Student development).

When analyzing whether the classes comprise more features or more difficulties, some statements can be made. Class 1 (Understanding the Inclusion process) would be an important resource, as it shows the understanding and knowledge of the theory; however, there is no practical effect of this knowledge, which shows difficulty in articulating theoretical knowledge with praxis. Class 2 (School-family relationship comprises more difficulties, as more teachers report the lack of support from families. Class 3 (Difficulties in the process) understands the difficulties that teachers encounter, which guide the methodologies used that appear in Class 4 (Teachers' practices inside the classroom). Class 4 (Teachers' practices inside the classroom) shows a resource, which arises, however, from difficulty and is not being effective; therefore, it can be said that it also includes difficulties. Class 5 (Student Development) addresses more students' difficulties, so it is a more difficult class.

Family-school

The family-school relationship was quite discussed in the interviews with those responsible and the teachers, constituting classes in the two corpus of analyses, but with considerable discrepancies. Those responsible reported, in general, that they are present in the educational environment and that they have a good relationship with the school as a whole; despite the difficulties, they find resources to help their children, such as helping with homework, and training in reading and writing. Through the analysis of the CFA (parents corpus), it is possible to observe that the difficulties of the children arising from the disability and the challenges of the parents impact the family context, which also impacts the relationships with the school.

The teachers brought reports that some families are present, while others are not. For them, the biggest problem in the student's development is often found in family issues; they say that, if the family could help, the students would have a progression in learning. These results are even visually confirmed by the analysis of the CFA (corpus professors), in which the class referring to the family is far from that of the student's development. Therefore, this study shows different perceptions of school and family: those responsible see the school as a positive resource, a factor of support and protection for the development of their children; the teachers report problems in the partnership with the family and difficulties that impede the development of these students. Communication and presence at school were considered satisfactory by parents; however, teachers do not see this parental participation or do not see it as sufficient. Pamplin (2005) also showed an asynchronous relationship between school and family, in which parents considered themselves present and the school claimed no interest, pointing out that, although parental participation is desired, there are still no mechanisms and strategies to promote such involvement.

The importance of understanding this relationship and seeking subsidies in the work of mediation between the actors is highlighted. The family and the school are different educational sources; the teaching provided by the family has an informal character, while that of the school has a systematic character and aims at the construction of knowledge in sequential stages, in which both are important, as well as the partnership is shared to seek joint strategies to benefit the educational process (Dessen & Poland, 2007). The family-school partnership is considered, in several studies, as one of the most influential factors in the inclusion process, even considering the student's cognitive and social development (Benitez & Domeniconi, 2012; Brandão & Ferreira, 2013; Christovam & Cia, 2013; Vilaronga & Mendes, 2014). Maturana and Cia (2015) show discrepancies in this relationship; however, they show that the weekly school-family contact favors the creation of strategies on both sides and that a close relationship is essential. However, this partnership is subject to factors such as the school's conceptions of inclusion, the support offered, and municipal, state, and national educational policies. Therefore, studies are needed to investigate this issue.

Thus, it is understood that the participants of this study need stimuli and projects aimed at strengthening and supporting this relationship, seeking improvements for both parties, to effect the inclusion process and favor the integral development of students with intellectual disabilities. Studying family-school relationships is a considerable source of information, as it allows the identification of conditions and aspects that influence communication and patterns of collaboration and conflicts between these two institutions (Dessen & Polonia, 2007). Both the family and the school, despite being essential for development, are also contexts in which risk and protection mechanisms operate (Marturano & Elias, 2016). Therefore, it is essential to have interventions aimed at these two microsystems and that are also supported by issues at the macrosystem level, with the implementation of public policies to strengthen the school-family relationship.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study aimed to investigate how the process of inclusion of students with intellectual disabilities is occurring, raising resources and difficulties. We understood, from the perspective of guardians and teachers, this process from different aspects, involving both personal family relationships and the relationships intrinsic to the school environment and the school-family relationship. We observed that the guardians see, as difficulties, providing support and helping their children with school matters; and, as resources, the fact that their children are enrolled and feel good in the school environment, in addition to a good relationship with the school. The teachers pointed out daily difficulties in the inclusion process and problems in the family-school partnership.

The study presents rich material analyzed with an important number of participants, with the help of the Iramuteq software, which brings scientific rigor, in addition to originality, contributing to discussions in the field of educational inclusion. As a limitation, the non-participation of students as informants stands out, which should be considered in further studies.

It was possible to make important contributions when studying inclusion from the perspective of different informants (family and teachers), central agents in the promotion of inclusion. When raising aspects of resources and difficulties, possibilities of intervention are raised with these families and these teachers to establish fruitful conclusions that lead to the understanding of what would be the inclusion of students with disabilities - a topic widely studied, but that still faces critical problems of practical execution and divergences between what is established in the educational guidelines. One of the important conclusions of this study is the need for integrated work within schools, with regular classroom teachers, specialist teachers, family, and management. Therefore, we concluded the importance of targeted interventions and the articulation of laws and public policies to support and subsidize with efficient mechanisms the inclusion process in its effectiveness in practice.

REFERENCES

American Association of Intellectual and Developmental Disability - AAIDD. (2010). Intellectual disability: definition, classification, and systems of supports (11th ed). [ Links ]

Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa - ABEP. (2018). Critério de Classificação Econômica Brasil. ABEP.http://www.abep.org/criterio-brasil. [ Links ]

Batista, M. W., & Enumo, S. R. F. (2004). Inclusão escolar e deficiência mental: análise da interação social entre companheiros. Estudos de Psicologia, 9(1), 101-111. [ Links ]

Benitez, P., & Domeniconi, C. (2012). Verbalizações de familiares durante aprendizagem de leitura e escrita por deficientes intelectuais. Estudos de Psicologia, 29(4), 553-562. [ Links ]

Borges, A. A. P., & Campos, R. H. F. (2018). A escolarização de alunos com deficiência em Minas Gerais: das Classes Especiais à Educação Inclusiva. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 24(spe), 69-84. [ Links ]

Borges, L., Gualda, D. S., & Cia, F. (2011). O papel do professor na relação com as famílias de crianças pré escolares incluídas. Congresso Brasileiro multidisciplinar de educação especial, 6. - encontro da Associação Brasileira de pesquisadores em educação especial, 7. [ Links ]

Brandão, M. T., & Ferreira, M. (2013). Inclusão de crianças com necessidades educativas especiais na educação infantil. Revista brasileira de educação especial, 19(4), 487-502. [ Links ]

Brasil(1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Senado. [ Links ]

Brasil (1990). Lei n. 8.069, de 13 de julho de 1990. Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente - ECA. Dispõe sobre o Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente, e dá outras providências. [ Links ]

Brasil (1996). Lei n. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L9394.htm. [ Links ]

Brasil (2008). Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Especial. Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva. MEC/SEESP. [ Links ]

Brasil(2015). Lei n. 13.146, de 6 de julho de 2015. Institui a Lei Brasileira de Inclusão da Pessoa com Deficiência (Estatuto da Pessoa com Deficiência). [ Links ]

Briant, M. E. P., & Oliver, F. C. (2012). Inclusão de crianças com deficiência na escola regular numa região do município de São Paulo: conhecendo estratégias e ações. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 18(1), 141-154. [ Links ]

Camargo, B. V., & Justo, A. M. (2013). IRAMUTEQ: Um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. Temas em Psicologia, 21, 513-518. http://dx.doi.org/10.9788/ TP2013.2-16. [ Links ]

Carvalho, R. E. (2019). Educação Inclusiva: com os pingos nos “is”. (13ª ed). Mediação. [ Links ]

Cerqueira, M. M. F., Alves, R. O., & Aguiar, M. G. G. (2016). Experiências vividas por mães de crianças com deficiência intelectual nos itinerários terapêuticos. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 21(10), 3223-3232. [ Links ]

Christovam, A. C. C., & Cia, F. (2016). Comportamentos de pais e professores para promoção da relação família e escola de pré-escolares incluídos. Revista Educação Especial, 1 (1), 133-146. https:⁄⁄doi.org⁄10.5902⁄1984686X13441. [ Links ]

Christovam, A. C. C., & Cia, F. (2013). O Envolvimento parental na visão de pais e professores de alunos com necessidades educacionais especiais. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 19(4), 563-581. [ Links ]

Coelho, G., Campos, J. A. P. P., & Benitez, P. (2017). Relatos de pais sobre a inclusão e a trajetória escolar de filhos com deficiência intelectual. Psicologia em Revista, (23)1, 22-41. [ Links ]

Costa, C. R., Moreira, J. C. C., & Seabra Júnior, M. O. (2015). Estratégias de ensino e recursos pedagógicos para o ensino de alunos com TDAH em aulas de educação física. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 21(1), 111-126. [ Links ]

Dessen, M. A., & Polonia, A. C. (2007). A família e a escola como contextos de desenvolvimento humano. Paidéia, 17(36), 21-32. [ Links ]

Faria, P. M. F., & Camargo, D. (2018). As Emoções do Professor Frente ao Processo de Inclusão Escolar: uma Revisão Sistemática. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 24(2), 217-228. [ Links ]

Garcia, R. M. C. (2013). Política de educação especial na perspectiva inclusiva e a formação docente no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Educação, 18(52), 101-119. [ Links ]

Gomes, C., & Souza, V. L. T. (2012). Psicologia e inclusão escolar: reflexões sobre o processo de subjetivação de professores. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, 32(3), 588-603. [ Links ]

Kassar, M. C. M (2014). A formação de professores para a educação inclusiva e os possíveis impactos na escolarização de alunos com deficiências. Cadernos CEDES [online], 34(93), 207-224. [ Links ]

Lahlou, S. (1994). L'analyse lexicale. Variances, (3),13-24. [ Links ]

Leblanc, J.-M. (2015). Proposition de protocole pour l'analyse des données textuelles: pour une démarche expérimentale en lexicométrie. Nouvelles perspectives en sciences sociales (NPSS), 11(1), 25-63. [ Links ]