Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 15-Sep-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469835918

ARTICLE

THE TEACHING INSPECTION SYSTEM IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY IN PARANÁ

1 Universidade Estadual de Maringá (UEM). Maringá, PR, Brasil.

2 Universidade Estadual do Oeste do Paraná. (UNIOESTE), Francisco Beltrão, PR, Brasil.

In this article, we investigate the organization of education inspection in Paraná in the first half of the 20th century, because it is relevant to understand the process of organization of education, considering that the inspection intervened in various areas of the school environment, both administrative and pedagogical. The time frame is based on the educational legislation, starting in 1901, in which we have the first legislation from Paraná of the 20th century, focused on education and that continues until the middle of the century, as the last legislation about the inspection was in 1938, remaining in force until after 1950. The sources of analysis were the legislation, reports, newspapers, books, among other documents of the period, considered as primary sources, and bibliographies about the subject. In the text, we emphasize the importance of the teaching inspection in the organization of education and the implementation of educational legislation, and we investigate how the teaching inspection was organized in the period. From the analysis, we infer that the inspectorate played a fundamental role in the organization of primary education, and for that, the inspection had a complex structure, which was distributed throughout the entire State, to supervise and disseminate a teaching model. In addition, the school inspectors acted as intermediaries between schools/teachers and the Government, as it was through their reports that there was the exchange of information between these sectors.

Keywords: School Inspection; Primary Education; Paraná 20th Century

Neste artigo investigamos a organização da inspeção do ensino no Paraná na primeira metade do século XX, para compreender o processo de organização da educação, considerando que a inspeção intervinha em diversos âmbitos do ambiente escolar, tanto administrativos como pedagógicos. O recorte temporal está baseado na legislação educacional, iniciando em 1901, no qual temos a primeira legislação paranaense do século XX, voltada à educação e vai até a metade do século, pois a última legislação sobre a inspeção foi em 1938, mantendo-se em vigor até depois de 1950. As fontes de análise foram a legislação, os relatórios, os jornais, os livros dentre outros documentos do período, considerados como fontes primárias e bibliografias sobre o tema. No texto, enfatizamos a importância da inspeção do ensino na organização da educação e na efetivação de legislações educacionais, e investigamos a forma como a inspeção do ensino se organizou no período. A partir da análise inferimos que a inspetoria exercia papel fundamental na organização do ensino primário e, para isso, a inspeção tinha uma estrutura complexa, que se distribuía ao longo de todo o estado, com o intuito de fiscalizar e disseminar um modelo de ensino. Além disso, os inspetores escolares se configuravam em intermediários entre as escolas/professores e o governo, pois era por meio de seus relatórios que havia a troca de informações entre esses setores.

Palavras-chave: Inspeção do ensino; ensino primário; Paraná século XX

En este artículo investigamos la organización de la inspección de la educación en Paraná en la primera mitad del siglo XX, ya que es relevante para comprender el proceso de organización de la educación, considerando que la inspección intervino en diferentes áreas del entorno escolar, tanto administrativo y pedagógico. El marco temporal se basa en la legislación educativa, a partir de 1901, en la que tenemos la primera legislación de Paraná en el siglo XX, centrada en la educación. Y se extiende hasta mediados de siglo, ya que la última legislación en materia de fiscalización fue en 1938, permaneciendo vigente hasta después de 1950. Las fuentes de análisis fueron legislación, informes, periódicos, libros, entre otros documentos de la época, considerados como fuentes primarias, y bibliografías sobre el tema. En el texto, destacamos la importancia de la fiscalización de la docencia en la organización de la educación y en la aplicación de la legislación educativa, e indagamos cómo se organizó la fiscalización de la docencia en el período. Del análisis se infiere que la fiscalía jugó un papel fundamental en la organización de la educación primaria, y para ello, la fiscalización contaba con una estructura compleja, que se distribuía por todo el Estado, con el objetivo de inspeccionar y difundir un modelo de enseñanza. Además, los inspectores escolares actuaron como intermediarios entre las escuelas / maestros y el Gobierno, ya que fue a través de sus informes que hubo un intercambio de información entre estos sectores.

Palabras clave: Inspección de enseñanza; Escuela primaria; Paraná Siglo XX

INTRODUCTION

The inspection service is of extraordinary value, as it constitutes the true mainstay of the activity, and, in general, of the teacher's professional conduct. Furthermore, it allows the most complete distribution of schools and constitutes the most solid guarantee of the teaching staff, when they work and fulfill their duties with exactness (PARANÁ, 1928b, p.230).

The organization of education in the first half of the 20th century was based on a policy of nationalization1 and literacy2 of the population that arrived in schools. As established by state legislation in 1917, there were five types of primary education institutions in Paraná at the time, isolated schools3, which were urban and rural; school groups, which were typically urban; schools subsidized by the state government, which were private schools; the mobile schools, which were typically rural, and the federally subsidized schools that were located especially in the colonization zones. Isolated, mobile, federal, and state-subsidized schools were constituted, for the most part, in isolated schools [...] governed by a single teacher, in multigrade classrooms” (SCHELBAUER, 2014, p. 81), and school groups they constituted [...] a grouping of isolated male and female schools, establishing it in a graded and graded regime” (ARAÚJO, VALDEMARIN, SOUZA, 2015, p. 33).

The investigation showed the relevant role of education inspectors in the dissemination of primary schools. In this way, we consider that the inspection of education was the basis for educational development in the first half of the 20th century, as the inspectors were the intermediaries between the government and the schools/teachers. In addition to supervising education, and enforcing legal requirements, they disseminated a type of education that was based on literacy and nationalization but also sought to improve the precarious conditions where most schools were, with guidance to teachers in bureaucratic and pedagogical. From the reports found, it is possible to verify that these subjects made attempts to go to the urban and rural schools, facing the challenges that the path imposed and, many times, they were not able to reach all the schools they should visit. Inspectors were required by law to record their visits to schools and produce reports, which had to be forwarded to their superiors in the administrative hierarchy.

According to Souza, [...] The inspection of education should be a central element around which the school apparatus would move” (SOUZA, 2004, p.63). In this way, in addition to being intermediaries, the inspectors were responsible for the entire organization of education, because they were in direct contact with schools and the government, in addition to constituting a means of [...] access to information about furniture, teachers, enrollment, hygienic conditions, methods, textbooks, etc.”, presenting an overview of how schools were in the State (SOUZA, 2004, p.232). There is no doubt that its records have become the basis for the development of actions and legislation on education. In this sense, we can emphasize that the inspection service is at the base of educational development, since the changes that occurred in education, in the State, took place through the notes that these subjects made in their reports that were presented to their superiors in the administrative hierarchy.

This intermediary relationship between the inspectors and the government and the schools/teachers dates back to the Empire, as indicated by Castanha (2007), but in the Republic, this relationship intensified, as there was a significant expansion of the network of schools throughout the country. Let's see some records about the importance of this function in messages/reports from state governors. President Affonso Alves de Camargo, in his report in 1917, emphasized that inspection was [...] the main factor for the good application of the adopted methods, it is being carried out with all rigor and efficiency, by school inspectors removed from own teaching” (PARANÁ, RPE, 1917c, p. 13). Caetano Munhoz da Rocha, in his 1928 report, highlighted that [...] the visits that inspectors periodically make to schools always produce the best results, both in terms of their distribution and location, as well as the work presented by the teachers” (PARANÁ, RPE, 1928b, p.140).

In addition to the governors, the inspectors were clear about the importance of the role they played in educational development. In their reports, they organized a section that brought the movement of the inspectors, and, on many occasions, they reflected on the objectives, organization, and forms of action of the inspectors. Let us see what inspector general Cesar Prieto Martinez recorded in his 1921 report:

The inspection of teaching must necessarily be the pivot around which the school apparatus will move to concentrate its energies. No company progresses without supervision, and those who run it have to know, like the back of their hands, the men and things that gather there daily, what comes in, what goes out, what makes a profit, and what makes a loss, everything. in short, it concerns the integrity and progress of the establishment (PARANÁ, 1921a, p.10).

From the report, it is possible to perceive the analogy made by the inspector when relating education to a company. This record reveals that the inspector was attentive to changes and innovations in the capitalist mode of production, such as, example, the ideas disseminated by Taylor4, which aimed to optimize the organization of work to increase workers' productivity. Silva (2019), when analyzing the work of inspector César Prieto Martinez, made an approximation of his actions with Taylorist ideas, because, according to him [...] worldwide movement that surpassed the organization of work performed in the factory” (SILVA, 2019, p,107). Silva emphasized that Taylorism went beyond factory work, reaching the organization of society and, ultimately, education.

Souza (2008) also emphasized that advances in the organization of work arrived at school, but did not make a direct association with Taylorism, but with the advance of science in general, very characteristic in Brazil, at the end of the 19th century and in the first decades of the 20th century. This phase was highlighted by the emergence and diffusion of school groups, which demanded restructuring in the administrative and pedagogical organization of schools, implying a “more systematic and regulated ordering of the curriculum, with the distribution of contents by series”, demanding “more rigid mechanisms of evaluation of the students for classification into classes and minute time control devices” (2008, p. 42).

Given the advance in productive rationality, the “pedagogical rationality that found support in the organization of factory work was, in a way, well accepted by teachers” (SOUZA, 2008, p. 45) and managers, to guarantee greater efficiency to the school work. Given this, greater efficiency was needed in the inspection service carried out by the teaching inspectorate, because within the principles of scientific rationality there was a need for constant supervision of the work, with the intention that the instructions were carried out by the workers.

Other educational principles and practices that came from the imperial period were reinforced with the advance of scientific/Taylorist rationality. Among them, Silva highlighted the piecemeal work, which translated into [...] the organization of content in disciplines with extensive curriculum”; to organize the classroom, with chairs in a row that resembled the organization of the factory; the authoritarian professor, who, like a [...] head of the industrial sector - who demands silence and performance, through punishments and rewards, which also sustains the current system”; bureaucratization reinforced through the implementation of “frequency control, internal and external assessments, and documentation” (2019, p.109). All these actions were reinforced by the inspection structure organized by the education inspectorate. This constant supervision, for the correct fulfillment of the instructions, was noticeable in the school inspection, being one of the main objectives of this sector, as we will see in the analyzes that follow.

According to Miguel, if we turn our gaze to the reforms that took place in the educational field, [...] inscribed in the political project of nationality” we will see that the changes in legislation and dissemination of schools took place “without the commitment of the most privileged urban layers of Paraná”. As the author indicated, these changes only took place due to [...] the inspector's will and dedication and pressured by demand. In Prieto Martinez's reports, she is constantly present looking for schools by the population” (MIGUEL, 1997, p. 45).

This demand can also be seen in press publications. In a chronicle from 1927, written by Sebastião Paraná and published in the Jornal Diário da Tarde, the following was recorded:

The teaching inspectorate, with commendable anxiety, attacks illiteracy from all sides, a common enemy, terrible and with harmful effects. Such an undertaking is grandiose: it enhances, ennobles, enriches the Homeland who cuts, polishes the rough diamond of youth intelligence-, the country's hope, the Republic's advanced guard (PARANÁ, S. 1927, p. 2).

We realized the relevance of inspection for the literacy campaign of the population and dissemination of schools. The inspection of teaching went beyond mere observation of the conditions of the schools, as it produced a set of information that was vital for the organization/reorganization of the educational field in the state of Paraná.

Gramsci understood and defined the State “as ‘educator’ insofar as it tends precisely to create a new type or level of civilization”. According to him, the “state tends to create and maintain a certain type of civilization and citizen” and, therefore, seeks to “make certain customs and attitudes disappear and spread others”. The auxiliary instruments of the State are the law, the laws, the school, and other institutions. For Gramsci, the state

it is an instrument of 'rationalization', acceleration, and Taylorization; it acts according to a plan, pressures, incites, solicits, and “punishes”, since, having created the conditions in which a certain way of life is “possible”, the “criminal action or omission” must receive a punitive sanction, of moral significance, and not just a judgment of generic danger (2002, p. 28).

Gramsci saw the State as an agent of education, as a producer and diffuser of civilization. By adopting these premises, we can better understand the role played by inspection agents, educational legislation, and the school, since all these elements were directly linked or subordinated to the state.

Given the significance of inspection of teaching for educational development, which intervened in various areas of the school environment, both administrative and pedagogical, as emphasized by the speeches of the time, we will analyze how the organization of this service took place, as it is relevant to understand the process of education organization. From this, we present below an analysis of how the inspection of education was organized in the period.

The time frame is the educational legislation of Paraná, from the first half of the 20th century, considering the laws of 1901 and 1938. In 1901, we have the first legislation of education in Paraná of the 20th century, which presents significant changes in the structure of inspection of teaching, to the 19th century, based on what was demonstrated by Castanha (2007). In 1938, there was a reorganization in the inspection of education in the state of Paraná, which lasted for many years without change, closing the reforms on inspection in the first half of the 20th century. Given the above, the clipping is based on legislation, which is one of the primary sources of the research, because, as Castanha highlighted [...] educational legislation, due to a large number of themes and issues that are explicit and implicit in it” (2011, p. 312), according to him, the law is a synthesis of multiple determinations, so when it is put “in execution, the contradictions are revealed, as private or group interests are contested, resistance is accentuated, and the law's failures appear. Such contradictions accelerate the debate and new alternatives are proposed, new laws are passed” (2011, p. 317).

In addition to legislation, we used reports from inspectors, teachers, and governors of Paraná, books and newspapers, and other documents that were found and related to education, which we consider primary sources. We also used secondary sources, written by authors who deal with the topic. Castanha (2011) conceptualizes these sources based on Aróstegui's studies, noting that the primary or direct source is that recorded by a witness in the person of the fact. Therefore, it is the source that has not yet undergone any type of analysis, and the source Secondary or indirect is a mediated source, it expresses an intentional analysis of a certain fact or object from other sources. Considering this assertion, in this research we will use primary sources, referring to period documents and secondary sources published by authors who present relevant information for discussion.

After this brief introduction, we will see how the inspection of education was organized in the first half of the 20th century, and what was its influence on the dissemination and organization of education in the state of Paraná during the period.

ORGANIZATION OF EDUCATION INSPECTION IN PARANÁ

According to Oliveira, [...] the inspection constitutes the administrative and supervisory body through which the public power exercised control over education”. During the entire analyzed period, the inspection was [...] subordinated to the Secretary of the Interior, Justice and Public Instruction, it had different names”, without losing its [...] its controlling and supervisory purpose” (1994, p. 150). In addition, it exercised its control and supervision, observing “the schools, in terms of functioning; teachers, regarding the teaching process, and students, regarding attendance and learning outcomes” (OLIVEIRA, 1994, p.151). All this through the action of inspectors who left records in their reports5. For the inspection structure to work, there was a hierarchy between the inspectors, each one with a function, and the aim was to make the inspection reach all schools in the State to regulate its operation, and assist and encourage the teacher, especially since the most teachers in the period had no academic training.

As the schools were spread throughout the state and were located in different locations, both in urban and rural areas, an inspection network was built to try to reach all of them, with the aim of monitoring and disseminating a teaching model. According to reports at the time, the schools located in the city had better conditions, with easier access to teaching materials, more students enrolled, and houses built/adapted for educational institutions. However, in rural areas, conditions were different, as schools were installed in precarious houses; access to teaching materials was time-consuming; students were often absent, as they needed to help the family with domestic and agricultural work; the sanitary conditions were unsanitary, consistent with the conditions of the rural environment at the time. Given this, the teachers trained by the Escola Normal preferred to work in schools in the urban area, which offered better conditions for the development of teaching. Thus, in rural schools, inspectors were, on many occasions, the only contacts that teachers had with the changes that occurred in teaching since, in addition to inspecting, inspectors also provided training to lay teachers, who were the majority in rural areas.

Considering this reality, school inspection is understood here as a social/educational function, which was historically constituted and influenced by the various power relations that permeated the school environment. In this sense, we consider the inspectors as intellectuals of the educational cause, because “their actions, ideas and thoughts” were fundamental to building/reconstructing history, being “privileged emissaries of a certain historical context” (BORGES NETTO; MACHADO, 2018, p. 196).

To understand the role of inspectors, we rely on the conceptions of Gramsci (1891-1937), who was contemporary with the scope of this research. According to the Italian philosopher,

ENT#91;...] all men are intellectuals, but not all men in society have the function of intellectuals (so the fact that someone may, at a given moment, fry two eggs or sew a tear in his coat does not mean that everyone whether cooks or tailors). Thus, historically specialized categories are formed for the exercise of intellectual function (2014, p. 18-19).

In a society in which approximately 70% of the population was illiterate, the few who mastered reading and writing exercised significant influence over the others.

Castanha (2007), based on the Gramscian framework, studied public education in Brazil in the 19th century, analyzing the social and political organization at three levels of relationships to understand the dynamics of the subjects involved in the disputes. Thus, according to the author, at the “most distant or diffuse level” were the landowners and ranchers dispersed in the different regions of the country, “in addition to civil servants, mainly police officers, teachers, block agents”, who constituted themselves “in large part”, as soon as there was a direction”. At the “intermediate level”, composed of “judges, chiefs of police, inspectors of public instruction, parish priests, farmers, doctors, journalists”, who “made the connection between the closest and the most distant, putting them in tune”, thus exercising “the function of disseminating intellectuals, who used the structure of the State and family relationships to carry out their tasks”. The “closest level” was made up of “ministers, councilors, provincial presidents, general deputies, and senators. Producer nucleus and, at the same time, disseminator of ideas and principles that supported a given project” (CASTANHA, 2007, p. 53).

According to Gramsci, “intellectuals are the 'representatives' of the dominant group for the exercise of subaltern functions of social hegemony and political government” (2014, p. 21). This statement helps us to characterize what kind of intellectuals the inspectors were. The intermediate elements occupied a strategic position, as they were in more direct contact with the diffuse element. As inspectors these intermediary subjects are between the government and schools/teachers, they disseminate, gather, and systematize information appropriating the school reality and, from that, create proposals to modify teaching. In such a way, they exercised the function of intellectuals considering that their positions and thoughts influenced and intervened in education. As indicated by Santi and Castanha, the concepts of traditional or organic intellectuals attributed to certain inspectors may vary, “depending on the analyzed aspect. If we look at him from the point of view of the class values to which he belonged, of morals”, we will see “a traditional intellectual, who defended order, hierarchy and the principles of the conservative group”, however, if “we look at the educational cause”, we can see “an organic intellectual” (2018, p 7).

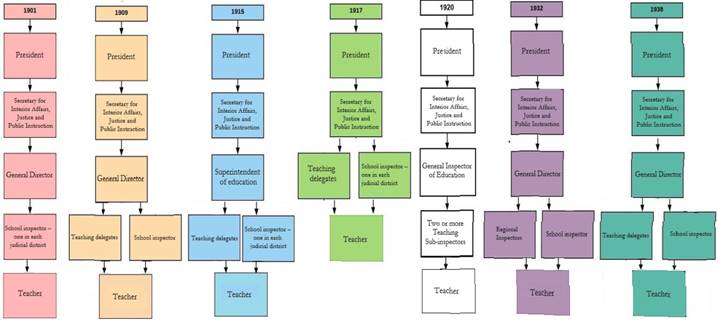

To exemplify what the inspection hierarchy was like and the changes it underwent in the period, we reproduce an organization chart built by Santi (2021). Let's see:

Source: SANTI (2021, p.157)

Figure 1 Organizational chart of the education inspection hierarchy between 1901-1938

Through the organization chart, we can see how the hierarchical structure of the inspection of education was organized during the first half of the 20th century in the state of Paraná. When analyzing the organizational chart, we observe the constancy in the hierarchy; the president/interventor was always in the position of decision-maker, followed by the secretary of Home Affairs, Justice, and Public Instruction. These two were responsible for choosing who would be the director general/superintendent of education6 or inspector general, a function responsible for organizing the information that came from the teaching delegates/regional inspectors and/or school inspectors. The teaching delegates and school inspectors were in direct contact with schools and teachers, being the main links between the government and the school. These subjects visited the schools, made reports, and sent them to the director/inspector general, who synthesized and passed them on to the secretary, who made a new synthesis and forwarded it to the president/state governor.

When considering this hierarchy, we will see the attributions of each position, according to the laws that were used to build the organization chart. The definition of the president/governor, as the highest authority of the inspection of education, appeared in the regulation of 1901, article 9, as follows: “The supreme direction of education is the responsibility of the governor of the State”, who would exercise the direction through the secretary of Interior Affairs, Justice and Public Instruction (PARANÁ, 1901, p. 85). This same provision was reproduced in article 14 of the 1909 regulation (PARANÁ, 1909, p. 117). As the secretaries' power was consolidated in the state's administrative structure, all legislations highlighted that a report on the state's instruction in the state should be sent annually to the president/governor, who, through the report and the position of the secretary Interior and the director general made decisions about instruction.

Regarding the Secretary of Interior Affairs, Justice, and Public Instruction, his attributions regarding the inspection of education in the 1901 legislation were mentioned and highlighted in the art. 10, that it would be responsible for [...] 1st ensuring the implementation of teaching laws and regulations; 2nd to give expedient to all the businesses concerning the Public Instruction; (...) 5th to present to the governor of the State an annual report on the movement of primary education” (PARANÁ, 1901, p.85). In the legislation of 1917, by which the position of director general was extinguished, the one who assumed the attributions of this post was the secretary of Interior Affairs, therefore, the legislation highlighted its main attributions: “Art. 1st: I Draw up special instructions to regularize the functioning of educational institutes. II assiduously inspect, by themselves and through the Delegates and Inspectors, all teaching institutes, public or private” (PARANÁ, 1917b, p.3).

In 1920, the position of inspector general was again included in the legislation and the duties of the secretary, indicated in the 1917 Education Code, returned to the inspector general. After the Secretary of the Interior, the most relevant position was that of inspector general. The only legislation that did not mention its attributions was the one of 1917, because, in this law, the position was extinguished, being reestablished in 1920 by law n.º 19997, which named the position as Inspector General of Education. The name of the position was changed several times in the legislation dealing with the inspection. In the laws of 1901 and 1909, he was called Director General, in 1915 he was changed to Superintendent of Education, in 1920 and 1932 the nomenclature of the position was changed to Inspector General of Education, and finally, in 1938, he was called Director General Education. These changes, it seems, were merely formal, as, in practice, the functions assigned to the position remained very similar.

According to the legislation, the director/inspector general was [...] the official in charge of carrying out the deliberations of the government and the congregation” (PARANÁ, 1901, p.85). This was repeated in all the laws, in which the office was mentioned. In addition, to assume the position of director general, the appointment and dismissal were the free choices of the president/state governor. The 1932 law added that the inspector general would be chosen from among the regional inspectors. However, to become a regional inspector it was required that “a) possess a diploma from the Escola Normal Secundaria de Curitiba; b) Have exercised the positions of teacher of an isolated school and direction of a school group; c) have more than ten years of good service provided to public education” (PARANÁ, 1932, p.1). This requirement of technical training for the candidate for the position of director general was positive and reveals that concerns with educational issues gained relevance. Until then, presidents/governors could make more political choices than technical ones for the command of the portfolio.

All inspector generals linked to instruction were subordinate to the general director. It was up to him or his subordinates to inspect all educational establishments in the state. According to the legislation, the position was defined as [...] a normal intermediary, for all purposes, between the Government and the authorities or employees of public instruction, of any category” (PARANÁ, 1915, p.5). Thus, through the director-general schools/teachers contacted the government, and the contact between the director-general and the schools, normally, took place through the mediation of the teaching delegates and school inspectors, who were the employees who should visit every school in the state.

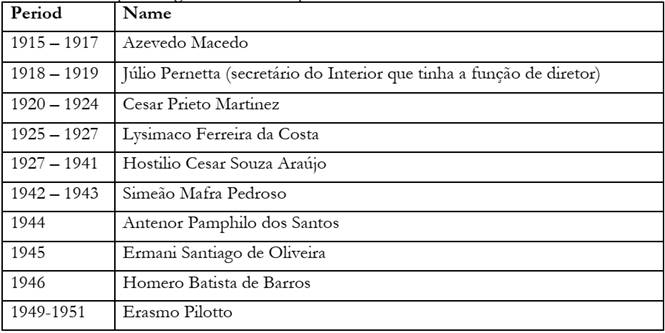

Based on the reports, Santi (2021) organized a Box with the name of the directors/inspectors general who passed through the inspectorate in the period from 1915 to 1951.

Source:SANTI, 2021, p.160.MIGUEL, 1997.

Box 1 Directors/inspectors general of the inspection of education in the state of Paraná from 1915 to 1941.

Among the men who assumed the post of general director, the best known were Cesar Prieto Martinez (1881-193)8, Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa (1883-1941)9 , and Erasmo Pilotto (1910-1992)10. There are several studies on these three that highlight their performance in Paraná education. Among these studies, we can mention Moreno, 2003, Abreu, 2007, Vieira and Marach (2007), and Padial, 2008. The three inspectors implemented very significant changes in public education in the state. Martinez and Costa held the position in the 1920s and had the support of Governor Caetano Munhoz da Rocha, who according to Moreno had a management [...] marked by nationalist perceptions and attitudes that differentiated him from his predecessors”. In this way, the reforms of public instruction that they promoted were always in line with this nationalization project (2003, p.24). Pilotto acted in the late 1940s and was responsible for the diffusion of the Escola Normal in the state, as highlighted by Miguel (1997). Pilotto was also the main organizer of the draft organic law of education of the state, which articulated education from kindergarten to university, passing through adult education and special education. Unfortunately, the project was not successful at that time, but it was the basis for future legislation. However, the inspector who remained for the longest time as general director was Hostilio Cesar Souza Araújo11, but we still do not have studies about him, only citations from his reports.

Following the hierarchy came the teaching delegates and school inspectors. To explain the attributions of these two positions, we will present them together, as one complemented the other. According to the 1909 legislation, the teaching delegates performed a technical inspection, focused more on pedagogical issues, and the school inspector, according to the same legislation, carried out an administrative inspection, linked more to bureaucratic issues. We know that this legislation did not last for a long time, however, this division in the way in which inspection was carried out persisted in the 1917 Teaching Code.

The position of teaching delegate was instituted by the 1909 legislation, being called regional inspectors in the 1932 law, but reverting to the name of teaching delegate in 1938. Among the attributions of teaching delegates/regional inspectors was, according to Art. 19: “Visit public or subsidized primary schools” (PARANÁ, 1917b, p.7). The inspector general, Cesar Prieto Martinez, in his 1921 report, presented the requirements for the proper exercise of the position:

First of all, you have to know the location of all the schools, the population that lives there, their economic and social conditions, uses and customs, resources, means of communication, distance from the nearest centers, climate, etc. ENT#91;...] Secondly, you must know the conditions of the school: if it works in a comfortable building, if it has furniture, if it is attended, etc. Thirdly, you cannot ignore who is the teacher who teaches there, what is his/her capacity to work, his/her relations with the population, directors, etc. in short, everything that concerns you, whether as an employee or as a citizen. Along with all these data, he will certainly know how to act with discretion whenever he needs to intervene in school life (PARANÁ, 1920b, p.10-11).

Thus, according to Cesar Prieto Martinez, it was only [...] the systematic inspection, carried out personally” by the inspector general, or [...] through his assistants”, which would be the teaching delegates and school inspectors, one could [...] collect all these data” mentioned( PARANÁ, 1920b, p.10-11). On the other hand, school inspectors could be, according to Art. 20, of the 1917 teaching code [...] any one of the teaching delegates”, in addition, [...] in districts where there are many schools or several villages with schools, there may be more than one inspector, and the schools under the jurisdiction of each one are determined by the secretary of the interior” (PARANÁ, 1920b, p.11).

Furthermore, they could be appointed to this position, according to Art. 22 [...] the Public Prosecutor or his deputy” (PARANÁ, 1920b, p.11). School inspectors were distributed as follows: for each judicial district where there was a school, an inspector would be appointed, who would visit the schools in his district at least twice a month. These inspectors were fundamental, because according to Ferreira (2013), without them it would not be possible to [...] guidelines regarding didactic procedures, in addition to encouraging and supporting them in their needs” (FERREIRA, 2013, p.220).

The Teaching Code of 1917 defined the duties of the teaching delegates and school inspectors as follows: the school inspector should designate where the schools would be installed, but he would talk to the teaching delegate, who helped in choosing the best place. The school inspector should monthly certify the work of the teacher, enrollment, and attendance of students; the teaching delegate, on the other hand, did not only observe the teacher's work but all the conditions, such as the teaching method used by the teacher, the school's situation, the materials available. The teaching delegate lectured teachers on new methodologies, new programs, and pedagogical issues; the school inspector, on the other hand, visited schools to verify the work performed by the teacher, the attendance, and enrollment of students, so that this teacher could receive his salary. In addition, both positions wrote reports, which, according to Moreno, varied [...] in style and organization”, but presented similar subjects, addressing the [...] description of the most serious problems and picturesque cases. Regarding the speech about the conditions of the schools ENT#91;they were] mostly laconic” (2003, p.39). These were some points that demonstrate the complementarity of these two positions, which carried out a technical inspection and an administrative inspection, vis-à-vis teachers and schools in Paraná.

In the early 1920s, the role of delegate was paid and that of school inspector was not. According to the president of the state, Caetano Munhoz da Rocha, because this inspection involves [...] a tremendous moral responsibility, as it affects the vital interest of a community, it is clear that the appointee, to fulfill this patriotic duty, must have the requirements of a citizen who wants to be useful to his brothers” (PARANÁ, 1921b, p. 96).

Munhoz da Rocha highlighted that because they do not receive remuneration, [...] many inspectors, for their dedication, deserve the title of meritorious of teaching” (PARANÁ, 1921b, p. 96). However, not all school inspectors had these characteristics. According to Cesar Prieto Martinez, some had no interest in teaching, and fearful of making enemies, they turned a blind eye to some irregularities. As the inspector general noted, this occurred in [...] more distant villages, where visits by the authorities are rarer, and sometimes even in nearby places” (PARANÁ, 1921a, p.47). This attitude of the local inspectors generated friction between them and the teaching delegates. Therefore, inspector Cesar Prieto Martinez proposed that suitable people be appointed to the position to reduce these conflicts (PARANÁ, 1921a). Another very efficient alternative was the creation of an instrument to standardize inspections, by sending printed bulletins/maps for inspectors to fill in when visiting schools. According to Souza, these bulletins were constituted as [...] an inspection service” (SOUZA, 2004, p.66).

Despite the good work that the delegates and inspectors provided to the organization of education, their performance was hampered in daily practice by a set of factors, the main ones being the long distances, and the tortuous and inhospitable paths. Many school inspectors made records of the difficulties they encountered in reaching the schools, which were passed on to the regional inspector/teaching delegate or directly to the inspector general. In the report by inspector general Cesar Prieto Martinez, from 1921 and 1922, excerpts from these records were reproduced, reporting the difficulties faced by inspectors in visiting schools, especially those located in rural areas. Let’s look at some excerpts: the teaching delegate Rubens de Carvalho, on a trip to Clevelândia, highlighted: [...] school”, he had passed through a [...] shadowed labyrinth of the woods, looking for unlit paths, after many, many hours of walking” (PARANÁ, 1921a, p. 40). The distances between one village and another were large, so they sometimes spent the night in [...] herders' tents and slept in the open” (PARANÁ, 1921a, p. 37). The teaching delegate, Suetonio Bittencour Junior, on a trip to Assunguí de Cima, highlighted that [...] a long journey through a narrow, tortuous path, full of frightening slopes; skimming often, frightening cliffs; intercepted, here and there, by thick trunks of gigantic trees, which the angry gales toppled” (PARANÁ, 1922, p. 35). It can be seen that the places were difficult to access and, therefore, that many isolated schools were in such precarious conditions and received few visits from inspectors.

In addition to the difficulties of the lack of roads and transport, there were also those related to the excesses of politics. According to a 1932 publication in the Jornal Diário da Tarde,

Unscrupulous politicking has made the prudent and rightly so. There is nothing more demoralizing to the zealous employee than the boss's unfairness in judging his work. The inspector points out the irregular functioning of a school; he registers the bad concept that the teacher has of his mission, harming teaching and giving all bad examples of unpunctuality, relaxation, disorder, and laziness. The inspector records; correct; teaches; it takes a few days for the teacher, with him working. Well, on the second inspection he finds that all his work and all his authority have been lost, with the same teacher; he remarks that it is useless to proceed and that the teacher must be replaced. He goes back and reports to his director, hoping that his motion will be passed and that his effort will be rewarded. Politicking intervenes: the director hesitates, the teacher is the son of one of his co-religionists or, at least, he is his protege, and his inspection time is thrown into silence, with a gesture of impatience at the inspector’s lack of perspicacity in radiating a political friend, in not knowing how to make repressive terms; only for the humble and unprotected masters. The result is absolute withdrawal on the part of the inspector, who feels injustice from their boss and does not want to be an instrument of their superiors in the honest exercise of their activity (Diário da Tarde, 02/13/1932, p. 1).

This criticism published in the press reveals the other side of the inspection of education. Despite the importance of the local inspection, it did not always present positive results, not because of the inspector's fault, but because of the “policy” that kept the teacher poorly prepared for the position of regent. In this way, the inspector was not only the voice of the government but also, in many situations, he represented the voice of the people and education, seeking to implement improvements in teaching, indicating changes in the way teachers conducted schools.

This action in the name of the educational cause was indicated by the education inspector Cesar Prieto Martinez when he noted that the inspectors, especially the education delegates, should be the spokespersons,

ENT#91;...] of the new orders; he will represent us in all acts and will do everything so that the strong remain strong, so that the most industrious receive the reward of justice and, as a last measure, the laggards or the incorrigible receive punishment (PARANÁ, 1920b, p.11).

As specified in the legislation, inspectors were responsible for overseeing the organization of teaching, inspecting existing schools, promoting the dissemination of new schools, and inspecting/evaluating/guiding teachers. In short, it was the agents of the state who should guard and promote education for the good of the whole society.

After understanding the actions/attributions required of inspectors, we will see how they were distributed across the state. Since the period of provincial Paraná, the inspection system was formed by a general inspector, some regional inspectors/teaching delegates and/or sub-inspectors, and by district/parish and/or school inspectors, who were the ones who effectively arrived at the schools. The number of intermediate inspectors and those closest to the schools varied frequently, depending on the period and the president/governor's commitment to the educational cause. The reports did not always bring these numbers in detail, so we will exemplify with data from the late 1920s and 1930s, which we located more completely, to demonstrate how this distribution occurred in the state.

Law 1999, 1920, recreated the position of inspector general and two or more sub-inspectors/delegates. In 1929, President Afonso Alves de Camargo emphasized that the state had one inspector and three sub-inspectors of education12 a number considered insufficient for the inspection service to occur correctly and to cover the entire state. Faced with this lack, he asked the deputies to [...] create three more posts for teaching sub-inspectors, which should be filled by competent normalist teachers” (PARANÁ, 1929b, p. 140). By decree 528, of 1932, five Regional Inspectorates were created, with the following headquarters: 1st in the capital, 2nd in Ponta Grossa, 3rd in Jaguariaiva, 4th in Rio Negro, and 5th in Imbituva (PARANÁ. Decree 528 of 1932). In 1935, the intervener Manuel Ribas highlighted that [...] the current number of inspectors (4) is insufficient to exercise it more rigorously so that as soon as possible, this number should be increased” (PARANÁ, 1935b). , p.19). The intervenor's mention of four teaching delegates was confirmed by ordinance n. 15, of February 7, 1938, which distributed the municipalities in the state to the four existing teaching stations (PARANÁ, Ordinance n. 15 of 1938). The five regional inspectors that existed in 1932 were reduced to four teaching delegates in 1938. However, according to data published by the Inep Bulletin of 1942, five teaching delegates were again registered (BRASIL, 1942, p.25). On January 26, 1946, the law that regularized public primary education came into force and instituted the Organic Law of State Primary Education, but this law did not address the inspection structure, maintaining the 1938 law in force (PARANÁ, Drecreto No. 435 of 1946).

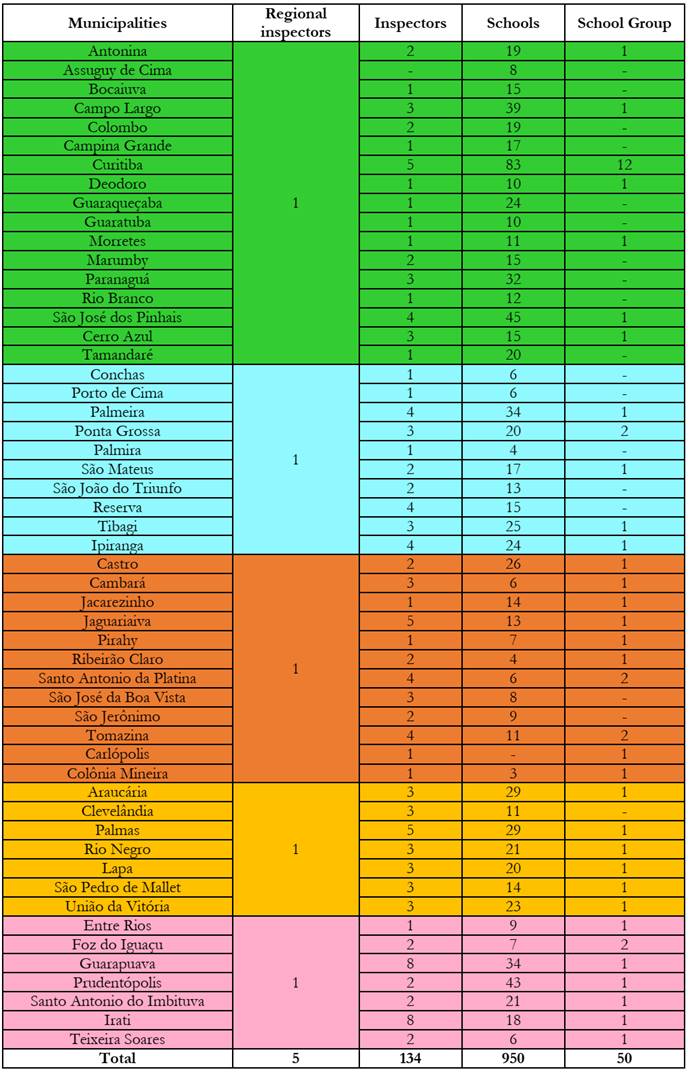

Santi (2021) collected a lot of data on the inspectors and organized a complete picture of the state's educational network for the year 1928. Let's see:

Source:SANTI, 2021, p.173.

Box 2 Distribution of regional inspectors and school inspectors by municipality in the state of Paraná in the year 1928

The box shows that there was a significant number of school inspectors, totaling 134, distributed across the municipalities. Based on the above, only the municipality of Assunguy de Cima13 did not have an inspector. According to the data in Box 2, the regional inspector for the Curitiba region had to inspect 412 institutions, including isolated schools and school groups. The inspector for the Ponta Grossa region was responsible for 164 institutions; the Jaguariaiva region visited 119, from Rio Negro 153, and Guarapuava 146. In these numbers and the distances they had to travel, we show that it was humanly impossible for regional inspectors to visit schools once a year, let alone once a month.

When considering the work of school inspectors, we found that the number varied as well. In the case of Curitiba, where there were 95 institutions, the average was 19 institutions per inspector. The highest average of institutions to be visited by the inspector was in Prudentópolis, which was 21.5, and the lowest was in Cambará, which was 2.33 institutions per inspector. In this case, many of the school inspectors could visit institutions twice a month, as required by law. Only in some municipalities with a large territory were these periodic visits not possible. This reality of the inspection structure shows that the system only worked with a good partnership between regional inspectors and school inspectors, that is, one complemented the work of the other.

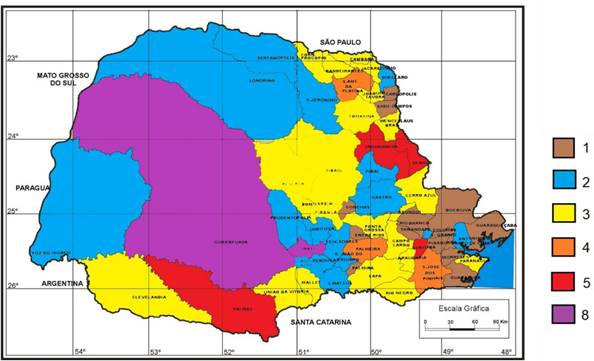

From the data in Box 2, Santi (2021) organized a map with the distribution of the number of school inspectors by the municipality in the year 1928.

Source: SANTI, 2021, p.171.

Map 1: Distribution of the number of school inspectors by the state of Paraná in 1928.

From the legend, we can see that each color corresponds to the number of inspectors who worked in a given municipality. The distribution of inspectors sometimes varied according to the size of the territory, as in the case of Guarapuava, and at other times by the number of schools, as in the case of Curitiba. But, in general, the number of school inspectors was not enough to comply with the legal determination, which provided for two monthly visits to each school.

The number of 134 possibly decreased during the 1930s, as the records of the Inep bulletin from 1942 listed [...] 49 municipal school inspectors and 54 school inspectors” (BRASIL, 1942, p. 25), making a total of 103 inspectors. The positive point of this data was the registration of municipal inspectors, showing that municipalities were beginning to invest more directly in the organization and dissemination of public education.

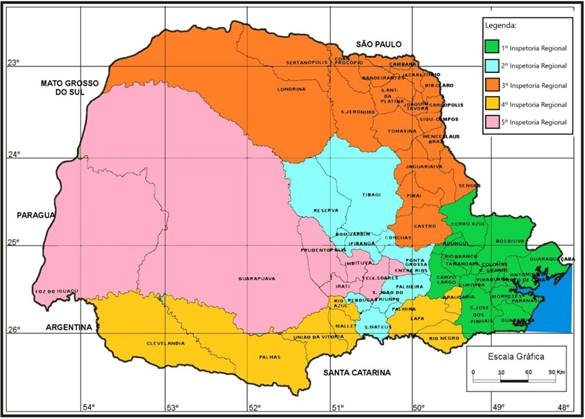

As previously indicated, by decree 528 of 1932, five regional inspectorates were created with their respective areas of coverage. To visualize this distribution, we reproduce the map organized by Santi (2021).

Source: SANTI, 2021, p.168.

Map 2: Regional Education Inspectors established by decree 528 of 1932.14

From the map, we can see the great distances that regional inspectors had to travel to visit all the schools that were under their jurisdiction. Only with the support of school inspectors, who visited schools, education data were collected.

If the inspection system already faced difficulties in becoming effective at the beginning of the 1930s, the situation worsened even more at the end of the decade, as the number of schools had already increased significantly and the number of regional police stations was reduced to four, due to the ordinance no. 15, of February 7, 1938, issued by the Secretary of Interior and Justice and signed by the Director General of Education, Hostilio Cesar de Souza Araújo. Map 3 shows this new distribution of Educational Police Stations across the state.

Source: SANTI, 2021, p.169.

Map 3: Teaching Police Stations established by ordinance n. 15, of February 7, 1938.

Map 3 shows the expansion of the coverage area of the Teaching Police Stations. We also see a fragmentation of the territory, mainly in the second and third police stations. The first covered the smallest territory but was the region with the largest number of institutions to be visited. The fourth police station covered almost 50% of the state territory but did not have as many schools to visit.

In this way, the [...] effort of standardization, control, and inspection, according to the inspectors' reports, falls with much greater emphasis on the Isolated Schools in the interior”. We can observe this by reading the reports themselves, which mostly describe how isolated schools were, presenting problems or [...] extreme situations of lack of school organization and lack of knowledge of any pedagogical precept”. Given this, most of the discourses of the time were intended to deposit [...] the greatest efforts and hopes for the regeneration of the nation”, in rural schools (MORENO, 2003, p. 31), where the population was located that lacked education to become Brazilians.

Based on the above, we can see how the inspection was organized and what was the attribution of each position present in this structure. As emphasized by Nagle, during the period the organization of the inspection service [...] became a preliminary stage to the full success of the execution of any plan” (2009, p. 221) regarding teaching. Through the reports inspectors, it was known how teaching was applied and what their needs were. It was from these reports that changes in teaching were thought of. According to Nagle,

The provinces were not quite a bureaucratic body, in a strict sense, nor were they a body of a technical nature, in the 1920s the transformation of the old provinces into general directorates will show the most evident signs of the attempt to bring the educational services to an effective direction, from a bureaucratic and administrative point of view. In this sense, what is achieved with the structuring of the general directorates represents an important intermediate point that will later facilitate the installation of the education secretariats (2009, p. 221).

There was a hierarchy between school inspectors, regional inspectors/teaching delegates and inspector general that was respected. However, school inspectors (furthest away), regional inspectors (intermediate) in the power structure were [...] maximum authority whose domain they exercised to model the practice of the masters” (FERREIRA, CARVALHO, 2015, p.52). The reports produced by them

ENT#91;...] they were considered unquestionable: they highlighted the qualities and defects of education professionals; they classified good and bad teachers in terms of their knowledge and practices; finally, all the teaching activities in primary schools (FERREIRA, CARVALHO, 2015, p.52).

In this way, we verified throughout the discussion that the inspectors were not only supervisors of the teacher's work, but they were the support of the schools in all aspects, both in the training and guidance of teachers, as well as in the organization and supply of furniture and materials for schools, especially in rural areas, where the inspector was the only contact between the teacher and the government.

The organization of the inspection of teaching, as it was recorded, involved several branches, becoming increasingly complex, but, according to the reports, necessary for the good development of teaching, as it organized all its functioning, from the choice of textbooks to the organization of the school space and the subjects that the teacher should teach.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Considering the analysis carried out throughout this article, we observe that the education inspectorate played a fundamental role in the organization of primary education in the first decades of the 20th century. for that, the inspection had a complex structure, which was distributed throughout the state, to inspect and disseminate a teaching model. In addition, school inspectors were intermediaries between schools/teachers and the government, as it was through their reports that information was exchanged between these sectors. The institution of the inspection network sought to establish technoscientific rationality, in which the school was compared to a factory and, therefore, its proper functioning required constant supervision of the teachers' work. Despite the inspection being disseminated throughout the state, it fell with greater emphasis on isolated rural schools, as these schools had a precarious situation, which was a reflection of the environment where they were located, where the long distances resulted in the lack of materials and trained teachers. Most of the time they had little or no academic training, and the inspection of teaching was the few moments found to bring some knowledge to teachers.

Given this, a complex structure was developed in the education inspection, which was composed of the secretary of the interior, the general inspector, the teaching delegates, and the school inspectors. The inspector general was responsible for all the supervision of education in the state. In addition to visiting schools, he produced a report that brought together the reports sent by school delegates and inspectors, and in that report, he presented ideas for modifying and improving the education system. These ideas were relevant and, for the most part, were implemented by the president/state governor.

Teaching delegates and school inspectors maintained direct contact with schools; they visited the institutions and followed the progress of teaching throughout the year. We verified that the inspection carried out by these two positions complement each other, one performing a technical inspection and the other an administrative inspection, respectively. When considering that these subjects were the closest to the school, we found that it was their responsibility to train, inform and encourage the teacher, monitor the progress of classes, observe school attendance, preside over exams, and change the location of schools, among other attributes that gave progress to education in the state. In addition, the reports of these subjects showed the reality faced by many schools, and sometimes they disseminated government prerogatives, especially when they demanded that legislation be complied with, or they took a stand alongside the teachers when they asked for improvements in teaching. Given this, we can say that the inspectors were not just the voice of the government, but were the voice of teachers and society that sought an increasingly better school.

REFERENCES

ABREU, Geysa Spitz Alcoforado de. A trajetória de Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa: educador, reformador e político no cenário da educação brasileira. 2007. 222 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2007. [ Links ]

ARAÚJO, José Carlos Souza; VALDEMARIN, Vera Teresa; SOUZA, Rosa Fátima de. A contribuição da pesquisa em perspectiva compa rada para a escrita da história da escola primária no Brasil: notas de um balanço crítico. In: SOUZA, Rosa Fatima; PINHEIRO, Antonio Carlos Ferreira, LOPES, Antônio de Pádua Carvalho (org.). História da escola primária no Brasil: investigação em perspectiva comparada em âmbito nacional. Aracaju: Edise, 2015. p. 27-45 [ Links ]

BORGES NETTO, Mario; MACHADO, Maria Cristina Gomes. Possibilidades interpretativas para as pesquisas sobre intelectuais na história da educação: ação intelectual de Florestan Fernandes. Revista Notandum, Ano XXI, n.47, p.193-213, mai.-ago. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação e Saúde. Organização do ensino primário e normal. XV - Estado do Paraná. Boletimn. 20. Rio de Janeiro: INEP, 1942. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/104590 acesso em:14/05/2021. [ Links ]

CASTANHA, André Paulo. O uso da legislação educacional como fonte: orientações a partir do marxismo. Revista HISTEDBR On-line, Campinas, número especial, p. 309-331, 2011. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://periodicos.sbu.unicamp.br/ojs/index.php/histedbr/article/view/8639912 > Acesso em:25/08/2020. [ Links ]

CASTANHA. André Paulo. O Ato Adicional de 1834 e a Instrução Elementar no Impé-rio: descentralização ou centralização? São Carlos: Universidade Federal de São Carlos, 2007. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Ana Emília Cordeiro Souto. Organização da instrução pública primária no Brasil: Impasses e desafios em São Paulo, no Paraná e no Rio Grande do Norte (1890-1930). Tese (Doutorado Educação). Uberlândia: Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, 2013. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Ana Emília Cordeiro Souto; CARVALHO, Carlos Henrique de. Docência e inspeção escolar na escola primária dos estados de São Paulo, Paraná e Rio Grande do Norte de (1890-1930). Goiás: AnaisIIIEncontro de história da educação do centro-oeste, 2015. p.69-75. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://eheco2015.files.wordpress.com/2015/09/docc3aancia-e-inspec3a7c3a3o-escolar-na-escola-primc3a1ria-dos1.pdf Acesso em: 23/12/2020. [ Links ]

GRAMSCI, Antonio. Cadernos do Cárcere, vol. 3., 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2002 [ Links ]

GRAMSCI, Antonio. Cadernos do Cárcere. vol. 2., 7 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2014. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO dos Advogados do Paraná. Hostílio César de Souza Araújo Disponível em:Disponível em:http://iappr.org.br/site/1933-2/ Acesso em 15 de março de 2022. [ Links ]

JORNAL Diário da Tarde de 1915 a 1946, Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://bndigital.bn.gov.br/acervo-digital/diario-tarde/800074 > Acesso em:20 de novembro de 2019. [ Links ]

MIGUEL, Maria Elisabeth Blanck. A formação do professor e a organização social do trabalho. Curitiba: Editora da UFPR, 1997. [ Links ]

MORENO, Jean Carlos. Inventando a escola, inventando a nação: discursos e práticas em torno da escolarização paranaense (1920-1928). Mestrado em Educação. Curitiba: Universidade Federal do Paraná, 2003. [ Links ]

NAGLE, Jorge. Educação e Sociedade na Primeira República. 3º Ed. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2009. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Maria Cecília de. Ensino primário e sociedade no Paraná durante a primeira República. (Tese de Doutorado) São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 1994. [ Links ]

O Ensino e o novo diretor da instrução. Jornal Diário da Tarde, Curitiba, 13 de fevereiro de 1932. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://bndigital.bn.gov.br/acervo-digital/diario-tarde/800074 > Acesso em: 20 de novembro de 2019. p.1 [ Links ]

PADIAL, Elyane Mozelli. As propostas de Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa para a instrução pública paranaense no período de 1920-1928. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Maringá: Universidade Estadual de Maringá, 2008. [ Links ]

PAIVA, Vanilda. História da educação popular no Brasil: educação popular e educação de adultos. 6. Ed. São Paulo: Loyola, 2003. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Decreto nº 93 de 11 de março de 1901. Regulamento da Instrução Pública do Estado do Paraná. Leis, Decretos e Regulamentos do Estado do Paraná, 1901. Curitiba: Tipografia da Penitenciaria. 314 p [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Decreto nº 510 de 15 de setembro de 1909. Regulamento orgânico do Ensino Público do Paraná. Curitiba: Tipografia d’A República, 1909. 46p. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Decreto nº 710 de 18 de outubro de 1915. Código de Ensino do Estado do Paraná. Coleção de Decretos e Regulamentos de 1915. Curitiba: Tipografia d’A República, 1915. 514 p. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do secretário de Estado dos Negócios do Interior, Justiça e Instrução Pública Enéas Marques dos Santos, apresentado ao presidente do Estado Affonso Alves de Camargo em 31 de dezembro de 1917. Curitiba: Tipografia da República, 1917a. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Decreto nº 17 de 9 de janeiro de 1917. Código de Ensino. Colecção de decretos e regulamentos de 1917. Curitiba: Tipografia d’A República, 1917b. 562 p. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Mensagem do presidente do Estado Affonso Alves de Camargo dirigida ao Congresso Legislativo do Estado do Paraná, ao se instalar a 2ª sessão da 13ª Legislatura, em 1 de fevereiro de 1917. Curitiba: Tipografia da República, 1917c. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do secretário de Estado dos Negócios do Interior, Justiça e Instrução Pública Enéas Marques dos Santos, apresentado ao presidente do Estado Affonso Alves de Camargo em 31 de dezembro de 1918. Curitiba: Tipografia da República, 1918. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Lei nº 1999 de 09 de abril de 1920. Programa de ensino para as escolas isoladas primárias do Estado. Publicada no Diário Oficial do Estado em 10 de abril de 1920. Curitiba, 1920a, p.1-2. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do Inspetor Geral de Ensino Cesar Prieto Martines, apresentado ao Secretário de Geral do Estado Marins Alves de Camargo, em 31 de dezembro de 1920. Curitiba: Tipografia a Penitenciaria, 1920b. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do Inspetor Geral de Ensino Cesar Prieto Martines, apresentado ao Secretário de Geral do Estado Marins Alves de Camargo, em 31 de dezembro de 1921. Curitiba: Tipografia a Penitenciaria, 1921a. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Mensagem do presidente do Estado Caetano Munhoz da Rocha dirigida ao Congresso Legislativo do Estado do Paraná, ao se instalar a 2ª sessão da 15ª Legislatura, em 1 de fevereiro de 1921. Curitiba: 1921b. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do Inspetor Geral de Ensino Cesar Prieto Martines, apresentado ao Secretário de Geral do Estado Marins Alves de Camargo, em 31 de dezembro de 1922. Curitiba: Tipografia da Penitenciaria, 1922. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do Inspetor Geral de Ensino Cesar Prieto Martines, apresentado ao Secretário de Geral do Estado Marins Alves de Camargo, em 31 de dezembro de 1923. Curitiba: Tipografia da Penitenciaria, 1923. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do Inspetor Geral de Ensino Cesar Prieto Martines, apresentado ao Secretário de Geral do Estado Marins Alves de Camargo, em 31 de dezembro de 1924. Curitiba: Tipografia da Penitenciaria, 1924. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do Secretário Geral do Estado Alcides Munhoz apresentado ao Presidente do Estado Caetano Munhoz da Rocha 1925. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do Inspetor Geral de Ensino Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa apresentado ao Secretário Geral do Estado. Curitiba, 1927b. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do Inspetor Geral de Ensino Hostilio Cesar S. Araújo apresentado ao Secretário Geral do Estado. Curitiba, 1928a. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Mensagem do presidente do Estado Caetano Munhoz da Rocha dirigida ao Congresso Legislativo do Estado do Paraná, ao se instalar a 1ª sessão da 19ª Legislatura, em 1 de fevereiro de 1928. Curitiba: 1928b. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do Inspetor Geral de Ensino Hostilio Cesar S. Araújo apresentado ao Secretário Geral do Estado. Curitiba, 1929a. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Mensagem do presidente do Estado Affonso Alves de Camargo dirigida ao Congresso Legislativo do Estado do Paraná, ao se instalar a 2ª sessão da 19ª Legislatura, em 1 de fevereiro de 1929. Curitiba: 1929b. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do Inspetor Geral de Ensino Hostilio Cesar S. Araújo apresentado ao Secretário Geral do Estado. Curitiba, 1931. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Relatório do Secretário de Estado dos Negócios da Fazendo e Obras Públicas Othon Mader, apresentado ao Governador do Estado Manoel Ribas, em junho de 1935. Curitiba: 1935a. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Decreto nº 528 de 02 de março de 1932, Regulamento da Inspeção do Ensino. Publicado em Diário Oficial em 04 de março de 1932. Curitiba, 1932. p.1-3. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Mensagem do Governador Manoel Ribas apresentada a Assembleia Legislativa do Estado ao se instalar a 1ª sessão da 2ª Legislatura, em 16 de maio de 1935. Curitiba: Empresa Gráfica Paranaense, 1935b. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Secretaria de Interior e Justiça - Diretoria Geral de Educação. Portaria n. 15, de 7 de fevereiro de 1938. Distribuição dos municípios pelas diferentes Delegacias de Ensino do Estado. Curitiba: Diário Oficial do Estado do Paraná, ano 8, n. 1801, de 26 de fvereiro de 1938, p. 1-2. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Decreto nº 435 de 26 de janeiro de 1946. Regulariza o ensino primário público no Estado e institui a Lei Orgânica do Ensino Primário no Estado. Curitiba: Diário Oficial do Estado do Paraná, ano 16, n. 567, de 5 de fevereiro de 1946. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Anteprojeto de Lei Orgânica da Educação do Estado. Curitiba, 1949. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://www.arquivopublico.pr.gov.br/sites/arquivo-publico/arquivos_restritos/files/documento/2020-11/ano_1949_mfn_1498.pdf Acesso em 15 de março de 2022. [ Links ]

PARANÁ, Sebastião. Crônica. Jornal Diário da Tarde, Curitiba, 07 de abril de 1927a. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://bndigital.bn.gov.br/acervo-digital/diario-tarde/800074 > Acesso em:20 de novembro de 2019. p.2 [ Links ]

SANTI, Denize Naiara; CASTANHA, André Paulo. A atuação de Joaquim Silveira da Mota na organização da instrução pública paranaense entre as décadas de 1850-1860. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, v.18, p.1 - 24, 2018. [ Links ]

SANTI, Denize Naiara. A institucionalização da escola rural no paraná entre 1915 e 1946 e a atuação dos inspetores. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). Maringá: Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Centro de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes, 2021. [ Links ]

SCHELBAUER, Analete Regina. Da roça para a escola: institucionalização e expansão das escolas primárias rurais no paraná (1930-1960). Porto Alegre, Revista História da Educação, v. 18, nº 43, 2014. p. 71-91. [ Links ]

SILVA, José Ricardo Skolmovski da. A revista O Ensino e manifestações tayloristas nas propostas da reforma educacional de César Prieto Martinez (Paraná, 1920-1924). Dissertação. (Mestrado em Educação). Maringá: UEM, 2019. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Gizele de. Instrução, o talher para o banquete da civilização: Cultura escolar dos jardins de infância e grupos escolares no Paraná, 1900-1929. Tese (Doutorado em Educação?). São Paulo: PUC, 2004. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rosa Fátima de. Templos de civilização: a implantação da escola primária graduada no estado de São Paulo (1890-1910). 2ª Reimpressão. São Paulo: Fundação Editora da Unesp, 1998. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Rosa de F. História da organização do trabalho escolar e do currículo no século XX: (ensino primário e secundário no Brasil) São Paulo: Cortez, 2008. (Coleção: Biblioteca Básica da História da Educação Brasileira). [ Links ]

TAYLOR, Frederick W. Princípios de administração científica. Tradução de Arlindo Vieira Ramos. 4 ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 1960. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, Carlos Eduardo e MARACH, Caroline Baron. Escola de mestre único e escola serena: realidade e idealidade no pensamento de Erasmo Pilotto. In: VIEIRA, Carlos Eduardo(Org). Intelectuais, educação e modernidade no Paraná (1886-1964). Curitiba: UFPR, 2007, p. 269-289. [ Links ]

1The policy of nationalization of the population implemented in schools was boosted, especially after the First World War, which stimulated a negative view of foreigners who, for the most part, did not know the national language and customs, being considered by the government harmful to development. from the country. In view of this, the nationalization policy was implemented, which had great impacts on education, such as foreign schools that were closed, teachers were forced to teach in the national language, and subjects such as History of Brazil were being implemented in all educational institutions.

2In addition to nationalizing foreigners, it was also necessary to teach nationals to read and write. Statistical data show that most of the Brazilian population was illiterate, the 1920 census revealed that 80% of the Brazilian population were illiterate; in Paraná this number was 71%. There was then a movement to fight the “scourge of illiteracy”, in this way, [...] the defense of the diffusion of education to the masses by politicians and dilettantes in education, is intensified” (PAIVA, 2003, p. 37). The eradication of illiteracy was also influenced by the requirement of elections in which it was necessary to be literate to vote; in this way, the dissemination of primary education became [...] indispensable for the consolidation of the republican regime” (SOUZA, 1998, p. 27).

3Santi (2021), when studying rural schools, highlights that most isolated schools were located in rural areas. Based on this observation, he refutes the idea that the rural school only expanded after 1930, as most historians maintain, emphasizing that its diffusion began before that date in the state of Paraná.

4His classic work was The Principles of Scientific Management, published in 1911. Taylor is considered “the father” of Scientific Management, for proposing the use of Cartesian scientific methods in business administration. His focus was on operational efficiency and effectiveness in industrial and commercial management.

5The reports/messages from public authorities are official sources and, as such, are loaded with intentionality, which legitimize, qualify or disqualify the actions of state agents, depending on the political option of the writer. Capturing this intentionality is one of the great challenges for historians of education.

6The Education Code established by decree n. 710 of October 18, 1915, in practice, had little effect, as the Code was revised and republished by decree n. 17, of January 9, 1917. The new Code of 1917 suppressed the function of director general, overloading the function for the Secretary of State. The accumulation of function did not show effectiveness, causing the position of inspector general to be recreated by law n. 1999, of April 9, 1920.

7Art. 2 The Inspector General of Education will be appointed on a commission from among persons of notable professional capacity. Art. 3 The General Inspector of Education will have as his assistants two or more sub-inspectors of Education appointed in commission, among the Normal Teachers of the State (PARANÁ, 1920a, p.1)

8According to Silva, the government of Paraná needed a subject who [...] could give the desired appearance to the educational apparatus, paying attention to the needs and limitations of Paraná. To meet this end, he sought in São Paulo, the model state, a technician who could bring modern practices to schools in Paraná. César Prieto Martinez was that coach. Upon accepting the invitation to promote educational reform in Paraná, his proposals were based on rationalizing ideals that were in line with the State's budgetary limitations without losing his attention of the significant results, considering the great need to provide education. With this intention, Martinez promoted a series of administrative and pedagogical changes in the Paraná education system” (2019, p.140).

9Padial (2008) analyzed Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa's proposals and interventions in public education in Paraná, especially in teacher training. The author highlighted that Lisymaco had among its proposals the [...] expansion and improvement of the school system, literacy of the population, creation of Escola Normal, teacher training, among others. He thought that man should develop his ability to think and act and that education would reduce or end the poverty of the population. His thought was not the fruit of his prodigious mind, but was organized from what was being produced historically” (PADIAL, 2008, p.129). Both Cesar Prieto Martinez and Lysimaco Ferreira da Costa were relevant inspectors for the period in which they made significant changes to the education of the state.

10Erasmo Pilotto (1910-1992) was one of the main educators in Paraná in the 20th century and was one of the main articulators and diffusers of the Escola Nova Movement in the state. He was a teacher and director of the Escola Normal and director/secretary of state for Education and Culture (SEEC), between 1948 and 1951.

11Hostílio César de Souza Araújo was born in the city of Imbituva, in the State of Paraná, on April 23, 1893. He graduated in Law from the Law School of the University of São Paulo. He held the position of Secretary of Education of the state of Paraná, mayor of the city of Curitiba, secretary of Interior and Justice (currently Secretary of Justice) and, also, attorney general of the state. He was a full professor, postgraduate in law and philosophy at the University of Paraná, where he taught (INSTITUTO dos Advogados do Paraná, s.d.)

12Although the president brings the word sub-inspector, he is referring to the regional teaching delegates/inspectors, because there were not just three sub-inspectors/school inspectors, there were a lot more than that.

14The colors of the map correspond to the same ones in Box 2, to facilitate the understanding of the distribution of the regional inspectorates in the State.

Received: September 04, 2021; Accepted: April 07, 2022

texto en

texto en