Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.38 Belo Horizonte 2022 Epub 11-Nov-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469837849

ARTICLE

PROPAGANDA, MEDIA, AND EDUCATION: THE OFFICIAL AND ADVERTISING DISCOURSE ON THE 2017 HIGH SCHOOL REFORM1 2

1Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV). Viçosa, MG, Brasil.

This article brings the results of a research that analyzed the advertisements about the 2017 high school reform, making counterpoints with the reality of the Brazilian educational system and taking into account socioeconomic issues, interpretations of the text of the law, and historical perspectives of the policies for high school in Brazil. Techniques of document and content analysis were employed by using the Iramuteq software for examining texts in the light of a bibliographic matrix supported by the main axes of dialectical historical materialism. We identified two axes in the advertisements: the defense that Law no. 13.415/17 brings vigor and an air of renewal and novelty to high school on the one hand, and, on the other, the exaltation of a supposed freedom of choice by students for the curricular trajectory according to their ambitions, desires, and personal goals for the future, which would increase their satisfaction with the school experience. Nonetheless, we argue that the official and advertising discourse on Law no. 13.415/17 presents fallacious content that distorts and manipulates the content of the legal text and that the main objective of the advertisements is to guarantee the conditions for implementing an educational reform that suits those interested in maintaining the social status quo, in which an elite dominates and directs society, controlling production and big capital, relegating the rest of society to an adverse socioeconomic reality in which not even education is guaranteed for all in an equal manner.

Keywords: High School; Propaganda; High School Reform; Law no. 13.415/2017; Basic Education

Este artigo traz os resultados de uma pesquisa que analisou as propagandas sobre a reforma do Ensino Médio de 2017, realizando contrapontos com a realidade do sistema educacional brasileiro e levando em conta questões socioeconômicas, interpretações do próprio texto da lei e perspectivas históricas das políticas para o Ensino Médio no Brasil. Foram utilizadas técnicas de análise documental e de conteúdo com uso do software Iramuteq de exame de textos à luz de matriz bibliográfica amparada nos principais eixos do materialismo histórico dialético. Identificou-se a existência de dois eixos contidos nas propagandas: a defesa de que a Lei nº 13.415/17 traz vigor e ares de renovação e novidade ao Ensino Médio, por um lado, ao passo em que, por outro, a exaltação de uma suposta liberdade de escolha por parte dos educandos pela trajetória curricular de acordo com suas ambições, desejos e metas pessoais para o futuro, o que aumentaria a satisfação destes com a experiência escolar. Entretanto, defendemos que o discurso oficial e publicitário sobre a Lei nº 13.415/17 apresenta um conteúdo falacioso, que distorce e manipula o conteúdo do texto legal, sendo que o objetivo principal dos anúncios é garantir as condições de implementação de uma reforma educacional que convém àqueles interessados na manutenção do status quo social, no qual uma elite domina e dirige a sociedade, controlando a produção e o grande capital, relegando ao conjunto restante da sociedade uma realidade socioeconômica totalmente adversa na qual nem mesmo a educação é garantida para todos de forma igualitária.

Palavras-chave: Ensino Médio; Propaganda; Reforma do Ensino Médio; Lei 13.415/2017; Educação Básica

Este artículo presenta resultados de investigación que analizó los anuncios sobre la reforma de la escuela secundaria de 2017, haciendo contrapuntos con la realidad del sistema educativo brasileño y teniendo en cuenta los problemas socioeconómicos, las interpretaciones del texto de la ley y las perspectivas históricas de las políticas de enseñanza. medio en Brasil. Se utilizaron técnicas de análisis de documentos y contenido utilizando el software Iramuteq para examinar textos a la luz de matriz bibliográfica respaldada por el materialismo histórico dialéctico. Se identificó la existencia de dos ejes contenidos en los anuncios: la defensa de que la Ley N ° 13.415 / 17 trae vigor y aires de renovación y novedad a la escuela secundaria, por un lado, y, por otro, la exaltación de una supuesta libertad de elección de los alumnos según la trayectoria curricular de acuerdo con sus ambiciones y metas personales para el futuro, lo que aumentaría su satisfacción con la experiencia escolar. Defendemos que el discurso oficial y publicitario sobre la Ley nº 13.415 / 17 presenta un contenido falaz que distorsiona y manipula el contenido del texto legal, siendo que el objetivo principal de los anuncios es garantizar las condiciones de implementación de una reforma educativa que corresponda a aquellos Interesado en mantener el status quo, en el que una élite domina y dirige la sociedad, controla la producción y el capital y relega al resto de la sociedad una realidad socioeconómica adversa en la que ni siquiera la educación estaba garantizada para todos.

Palabras clave: Escuela secundaria; Publicidad; Reforma de la escuela secundaria; Ley 13.415 / 2017; Educación básica

INTRODUCTION

The year 2016 can be understood as a period of great instability in Brazil’s social, economic, and political life. Amidst the effervescence of civil sectors and large demonstrations throughout the main cities of the country, we witnessed the engineering and execution of a coup d’état that ousted the elected president Dilma Vana Rousseff even before the halfway point of her second term, on August 31, 2016, through the impeachment imposed by Congress. In a polarized political field with increasingly fierce clashes between parliamentarians in both legislative houses, added to the negative results of the industry, trade, and services and the growth of the mass unemployed in the country, the neoliberal ideology regained all its strength and took the Brazilian State and society by storm (FERREIRA; SILVA, 2017).

From then on, the new government taken over by Vice President Michel Temer, aligned with the interests of the ruling class and national leaders, began to implement a series of fiscal austerity measures under the pretext of cleaning up the public accounts and undertook a significant attack on the rights of the working class. In this sense, Congress discussed and approved unpopular reforms by a base of parliamentarians that, victorious in the impeachment process, remained, a priori, cohesive in support of the new organization of executive power3. Among the various measures that emerged in this scenario, the following deserve to be highlighted: the High School Reform, Law no. 13.415, of February 16, 2017, the Constitutional Amendment (EC) no. 95, of December 16, 2016, and the Labor Reform, whose legal device is Law No. 13.467, of July 13, 2017.

The high school reform came to light on September 22, 2016, and gained legal force with its publication in the official gazette on September 23, as Provisional Measure (PM) No. 746/2016. After the disclosure, the measure followed for the procedural rite in Congress in an urgency regime. In a rare demonstration of cohesion between the Legislative and Executive branches, the Provisional Measure was approved in all its central axes and sanctioned on February 16, 2017, by President Michel Temer, as Law No. 13,415/17.

Constitutional Amendment No. 95/16, published in the Official Gazette on December 16, 2016, established a new regime for the Federal Fiscal Budget, which lasts for twenty fiscal years, or twenty years. Aiming to address the Union’s budget deficit and control government spending, the main proposition of this Amendment is the establishment, in each financial year, of a spending limit for the primary expenses of the Executive and other institutions of the State apparatus, such as Congress, the Supreme Court (STF), and the PublicDefender’s Office (BRASIL, 2016). Such primary expenses of the Union refer, first of all, to government investments in health, education, security, infrastructure, and payment of the payroll of civil servants, among others. Therefore, the text of EC No. 95/16 excludes from the ceiling established the government’s financial expenses (interest payments and rolling public debt) — precisely those that take, proportionally, most of the budget provided in the Annual Budget Law (LOA). According to the legal text, the spending limits formulated by EC no. 95/16 as of the fiscal year referring to 2018 would be calculated by the value of the previous year, corrected by the variation of the National Wide Consumer Price Index (IPCA), published by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) (BRASIL, 2016). This way of calculating the budget, when applied to the Federal Executive, for example, inhibits by the root the possibility of a real increase in state investments since the correction by calculating the IPCA is a mere compensation of values. Thus, it can be said that the investments necessary to guarantee the social rights of the population, including public education, historically already underfunded, are frozen for the next twenty years. The EC No. 95/16, according to paragraph 5 of Article 107 also forbids the possibility of “opening supplementary or special credit that increases the total authorized amount of primary expenditure subject to the limits referred to in the article” (BRASIL, 2016a). In practical terms, this means that even if any future elected governments were interested in a minimally significant increase in investments in the aforementioned areas, the legal obstacles would be so many that the initiative would probably not get off the ground.

Finally, Law No. 13,467/17, whose main change is the amendment of the historic Consolidation of Labor Laws (CLT) of 1943, which aims, in theory, to adapt the labor legislation to the new labor relations, characteristic of the 21st century (BRASIL, 2017). With a discourse that advocated the modernization of the legal rites regarding the world of labor and to address a large number of unemployed at the time, Law No. 13.467/17 sought to regulate the intermittent work regime, allowing pregnant women to work in unhealthy environments vetoed in the previous legislation and reduced the autonomy and ability to act of the Labor Court, removing a supposed “weight” of the State in favor of negotiation and a “freer” relationship between employers and employees.

This is an evident and insurmountable contradiction. Considering the distinction between classes, which have equally distinct interests, one of which has economic power and the other has only its labor force, it is naive, to say the least, to think that there is parity in the negotiating capacity between worker and employer in the establishment of labor agreements. In addition, the reform directly attacked the unions by removing the obligation of the union tax contribution in a clear action to destabilize the working class4. In these terms, the labor reform represented a setback in the rights won by workers in decades of struggles, imposed in the wake of an authoritarian, liberalizing, privatizing, methodological, business agenda, and the reduction of the role of the State in sectors of popular interest.

Nevertheless, while the “Bridge to the Future” government determined the country’s direction from the top down, with little or no effective participation of the vast majority of the population, various civil society sectors have risen against the imposed reforms. The resistance can be seen, for example, when the approval of EC No. 95, in the second round in the Senate, on December 13, 2016, which occurred under the protest of tens of thousands of people who took the Esplanade of Ministries in Brasilia. On this occasion, the reaction of the Union power was violent.

Similarly, the establishment of PM No. 746 of the high school reform generated an immediate reaction by secondary students, teachers, and educators, who, denouncing the precariousness underlying the purposes of the new high school arrangement, occupied schools throughout brazil5. “At the height of the movement, approximately 1,400 educational institutions came under student management” (FERREIRA; SILVA, 2017, p. 288). However, in that context, the lightning approval of the proposals, including Constitutional Amendment no. 95/16, which required a large majority of 3/5 of Congress, evidenced a distancing between the popular desires and the government.

In the instances of power, leftist parties have offered resistance against the measures. The Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL) filed a Direct Lawsuit on Unconstitutionality (ADI) No. 5.599 with the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Attorney General’s Office against Provisional Measure No. 7466. In an initial report, minister Edson Fachin of the STF understood that the measure did not respect the procedural rite and the need for dialogue required by a reform of this magnitude, contradicting the principles of democratic management of education recommended in the Federal Constitution and the Law of Directives and Bases of National Education (LDBEN), considering it even unconstitutional due to the form in which it was implemented (as a PM). In addition, according to the rapporteur, the reform did not present, in fact, effective and forceful solutions that would justify the urgency required for policies implemented through PM (BRASIL, 2016a).

In this context, the press and social networks were taken by debates and polemics regarding how the reform was instituted and its assumptions. Given the adverse scenario, the government then launched an intense and aggressive marketing campaign, widely disseminated through major television media, to exalt the new configuration of high school education. As Saviani (2018) pointed out, this reaction occurred when the criticism directed at the measure was ignored. As political propaganda, the advertisements about the high school reform brought to light how the State and the Ministry of Education (MEC) “sell” their educational policy, thus seeking to oil the conditions necessary for its effectiveness.

Considering the problem above, our goal was to analyze the official discourse in the political advertisements about the high school reform embodied in Law No. 13,415/17 by focusing on its meanings, purposes, and impacts and making contrasts with the reality of the Brazilian educational system and considering socioeconomic issues, interpretations of the text of the law itself, and historical perspectives of the policies for this stage of education in Brazil. This qualitative and quantitative study used content analysis for data collection and French text analysis software Iramuteq. According to Moraes,

Content analysis is a research method used to describe and interpret the content of all documents and texts. This analysis, leading to systematic, qualitative, or quantitative descriptions, helps to reinterpret the messages and reach an understanding of their meanings at a level that goes beyond an ordinary reading (MORAES, 1999, p. 2).

The bibliographical research, whose matrix is supported by the main axes of dialectical historical materialism, completes the theoretical and methodological set since by “investigating the intimate connection between how society produces its material existence and the school institution it creates” (NOSELLA; BUFFA, 2009, p.79), historical materialism’s primary objective is to go beyond the:

Phenomenal, immediate, and empirical appearance - where knowledge necessarily begins, being this appearance a level of reality and, therefore, something important and not disposable, is to apprehend the essence (i.e., the structure and dynamics) of the object. In a word: the research method that provides theoretical knowledge, starting from appearance, aims to reach the object’s essence (NETTO, 2011, p.22).

Once the theoretical and methodological scope is defined, we must explain the procedures adopted in dealing with the research materials that culminated in obtaining the data analyzed below. First, we defined a set of advertisements (A) produced by the MEC about the high school reform to be submitted to the analysis. We then obtained a sample of five ads, all linked in major media and available on the MEC’s channel on the Youtube platform between 26/12/2016 and 04/01/2017, namely:

A1 - With the New High School, you have more freedom to choose what to study! (BRASIL, 2016b)

A2 - The New High School will make learning more stimulating and compatible with your reality!7 (BRASIL, 2016c).

A3 - The New High School will improve the education of young people! (BRASIL, 2017b).

A4 - With the new High School, you can decide your future! (BRASIL, 2017c).

A5 - The New High School will be more stimulating and compatible with your reality!8 (BRASIL, 2017d).

Second, we proceeded to the ipsis litteris transcription of the content of the advertisements, thus ensuring greater ease and clarity in their manipulation and, thus, preparing the text corpus. Using Iramuteq, we submitted the transcriptions to two tools available in the software: Similarity Analysis and Word Cloud generation. The former is a tool that shows us the occurrence and interconnection between the main words and terms contained in the examined contents, and the latter reveals the most representative words present in the text based on statistical criteria.

A priori, each of the five advertisements constituted an individual text corpus, analyzed separately in both tools, which allowed the identification of their specificities. Then, the advertisements were collected in a single corpus and studied again, which allowed the understanding of the general lines of the content. This procedure led to data sets that will be partially exposed in the subsequent sections of this text for due discussion.

In addition to the announcements, however, we consider useful the inclusion of other documents for the due examination, most of them legal texts related to the proposed analyses, namely: Opinion No. 45, of January 14, 1972 (CFE, 1972); Rapporteur of the Direct Lawsuit of Unconstitutionality No. 5.599 (BRASIL, 2016a); Constitutional Amendment No. 95, of December 16, 2016 (BRASIL, 2016); Law No. 13.415, of February 16, 2017 (BRASIL, 2017a); and, lastly, Law No. 13.467, of July 13, 2017 (BRASIL, 2017).

That said, the following pages will present the development of reflections and conclusions arising from the materials, documents, sources, and methods mentioned above. We will start with brief considerations about the role of the media in Law 13.415/17, connecting it with a brief debate on the role of political advertisements in democratic societies. Next, we trace an overview of the recent history of high schools in Brazil, electing as an initial landmark the school reform of the dictatorship embodied in Law No. 5.692/71 and culminating with the 2017 reform, the most recent educational policy of this magnitude in the country. Subsequently, our focus was to identify the lines of force of this reform and the main elements of the political advertisements produced by the MEC in the context of its approval and then confront them with the reality of high school in Brazil.

THE ROLE OF THE MEDIA IN THE CONTEXT OF LAW No. 13.415/17: DEMOCRACY AND POLITICAL PROPAGANDA

According to Pochmann (2017), in the years immediately prior to the impeachment process, during the Workers’ Party (PT) government in Brazil, the keynote of international politics sought to maintain the legacy of the Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva government (2003-2010), which, in turn, was marked by a realignment of Brazil in global geopolitical terms, in which the former subservience to the hegemony of the United States gave way to the search for strengthening alliances with neighboring countries, as in the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR) bloc, and with other emerging nations such as Russia, China, India, and South Africa, in the BRICS.

In the face of Brazil’s growing political and economic prominence, it became essential for the U.S. imperialist interest to overthrow the government and replace it with one that would once again completely submit to U.S. power9. The book O Golpe de 2016 e a Educação no Brasil [The Coup of 2016 and Education in Brazil], the result of the lectures given during the first semester of 2018 in the free course of the same name, promoted by the College of Education of the State University of Campinas (FE-UNICAMP), brings together texts by intellectuals who have focused on understanding the context of the formulation of Law 13.415/17 and the current game of internal and external political forces that act in Brazil in order to think about such issues.

In this sense, according to Medeiros Filho (2018) and Saviani (2018), Brazil was the target of a type of imperialist intervention that does not use the military apparatus and, on the contrary, relies on the most diverse institutions of the country itself acting to destabilize a government; this movement is called “Hybrid War.” In the case of Brazil, the Judiciary, in the figure of the first instance judge Sérgio Moro and the Lava-Jato operation, and the mainstream media stand out (SOUZA, 2017; MASCARO, 2018), which, in turn, by giving privileged focus to corruption cases in which PT politicians were involved, sought at all costs to delegitimize the Rousseff government while directly attacking former President Lula, a leading and prominent figure in the political field of Brazil today. Judge Sergio Moro, meanwhile, repeatedly leaked to the mainstream media allegations and wiretaps that must, by law, remain under investigation. Gradually, the population was called to the streets to protest, attributing the country’s crisis to corruption that, supposedly, had reached its peak with the PT government. The coverage of these demonstrations was another major highlight of the media and a strong weapon against the government. Because of this, it is noted that the media acted as a disseminator of the ideals of the dominant group in the country, whose interests are subservient to U.S. imperialist interests, and fostered a movement that culminated with the removal of Dilma (and, consequently, of the PT, from a 13-year stay in the federal executive branch) in a parliamentary, legal, and media coup that brought to power a political group with a conservative, surrenderist, and neoliberal bias (SAVIANI, 2018).

However, in addition to the role it played as the architect of the impeachment, when it comes to the context that relates directly to the approval of Law 13.415/17, the media was the major medium through which the massive political advertisements about the high school reform were linked. Our understanding of political advertisements is anchored in Chomsky (2014). The author understands these advertisements as an instrument to oil the conditions for implementing governmental actions, as they seek to create consensus and formatted opinions about a certain subject. Chomsky goes through the history of political propaganda, going back to the creation of the Creel Commission in 1916, which was responsible for changing the opinion of the American population about the country’s entry into the First World War (1914-1918). Through the massive and recurrent use of political propaganda, the dominant and ruling classes use the media to spread their ideological assumptions, transmitting to people how they should feel, act, and think about a given theme. Based on this context, we have what Chomsky classifies as a conception of democracy that considers that the people should be prevented from deciding on their matters and issues and that, for this reason, access to information should be rigidly controlled. In the author’s words:

In what is now called a totalitarian state or military state, it is easy. You just hold a club above their heads, and if they get out of line, you smash their heads in. But as society has become freer and more democratic, we have lost this power. Consequently, we need to resort to the techniques of political propaganda. The logic is crystal clear. Political propaganda is to a democracy what the stick is to a totalitarian state. This is a clever and advantageous attitude because, once again, common interests escape the disoriented herd: it cannot decipher them (CHOMSKY, 2014, p.10).

Given this theoretical horizon, the political advertisements referring to Law no. 13.415/17 are configured as a powerful tool of manipulation and social coercion capable of producing consensus and formatted opinions favorable to the high school reform without it being possible to contest it from common sense. The intense marketing campaign produced by MEC to promote its new policy, in a clear response to the reactions of sectors of civil society before the Brazilian political and social instability at the time, also makes use of other types of gimmicks that increased its effectiveness: a modern and easy-to-identify clothing, appeal to subjectivity, and the use of empty slogans and set phrases, such as “Those that know the New High School, approve! [...] Now it is you who decides your future” (BRASIL, 2017d).

BRIEF CONSIDERATIONS ON THE RECENT HISTORY OF SECONDARY EDUCATION IN BRAZIL: FROM LAW no 5.692/71 TO LAW no 13.415/17

Our debate starts from the definition of the teaching reform embodied in Law No. 5,692 of 1971 as a significant milestone in the history of high school education in Brazil since it can be considered as the point of greatest impact on the structuring of Brazilian education and, specifically, of technical training at the high school level, since it makes professionalization compulsory in all high school education (RAMOS, 2012, p. 31-32). Conceived and sanctioned in the times of the “economic miracle,” which, according to Germano (1993), corresponded to the end of the 1960s and early 1970s, when the Brazilian economy grew by 10% per year, driving the idea of Brazil as a power and generating a climate of euphoria in the country, supported during the period of greater repression of the civilian-military regime (1964-1985), this reform “followed the changes in the world of work, determined by the growing industrial development resulting from the import substitution model” (KUENZER, 2009, p. 29). It was, therefore, in its core that the technicist pedagogy was consolidated in Brazil, which was based on the search for scientific neutrality, efficiency, productivity, and rationality of educational processes, in addition to incorporating the molds of factory production to train the workers required for the capitalist context of the time (SAVIANI, 2013).

According to Kuenzer (2009), through compulsory professionalization, Law 5.692/1971 intended to end the duality historically built in high school education10 and guarantee everyone the same school trajectory. To justify the validity of the new law the government concocted several arguments that made up an official discourse about the reform. One was that the training of technicians was necessary due to the scarcity of these professionals in the market. Another was that the professionalization of the curriculum would serve to avoid the “frustration of young people,” who, after completing high school, theoretically would not enter university or the labor market because they did not have a professional qualification (RAMOS, 2012). Lastly, it was also argued that the reform would solve the shortcomings of the LDB of 1961, would solve the educational problems in the country, and that work training was closely related to the self-fulfillment of young people as the purposes of education in schools (CFE, 1972).

Nevertheless, in concrete terms, the reform of the civil-military dictatorship sought to disarticulate the basic training of Higher Education and thus repress the growing demand for vacancies from the middle classes (ROMANELLI, 1978). As Oliveira (2017, p. 23) reported, in the official government discourse, the school structure would become more adequate and effective in the selection of the most “capable,” that is, wealthy students and those of favored social conditions, enrolled in private schools, prone to continue their studies after high school to the detriment of the “incapacitated,” who would remain, on the contrary, in the minimum stage, with sufficient technical training to obtain a base salary in the productive system, deepening the system of exclusion. In this scenario, and despite the State’s efforts to support its educational reform, Law 5.692/71 failed in its main determinations, having been abandoned in the following decade.

According to Saviani (2013), effective in the 1980s, in the context of the country’s re-democratization after two decades of authoritarianism, the increase in academic production and the formation of groups and organizations that defended an eminently human, public and quality education proposal, focused on the comprehensive development of young people, leveraged the so-called counter-hegemonic pedagogies. Thus, new projects were brought into the field of education in several places in Brazil11.

Nevertheless, the country’s debt crisis with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, the emergence of neoliberalism, and the changes that occurred in production during the period of the 3rd Industrial Revolution, or productive restructuring, ended up becoming the central force that shaped educational policies in the last two decades of the 20th century. At the mercy of the determinations of the creditor institutions, educational policies in Brazil were based on the search for human capital formation that would fit the new standard of accumulation and production demanded by the capital system (SOARES, 2007).

According to Duarte (2010), the State’s actions to universalize Basic Education in Brazil in this period were based on the universalization of Primary Education, as determined by the World Bank, which saw in this stage of education the greatest potential return on investment and human capital formation. Still, according to the author, in comparison with neighboring countries such as Chile and Argentina, Brazil only belatedly started to deal with the universalization of High School12. The Federal Constitution of 1988 and Law 9.394 of 1996 (LDBEN) embraced these ideals insofar as they promoted the decentralization of the educational system, defining specific functions for states and municipalities, and exempting the Union from major responsibilities concerning Basic Education and High School.

The decentralizing logic, typical of the neoliberal minimal state discourse, remained the keynote of educational policies during the governments of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2010) and Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016). According to the 2016 Basic Education Census, of the 28.3 thousand schools that offer high school education in Brazil, only 517 are federal, a fact that corresponds to the fact that the responsibility for offering this stage of education lies with the states, as determined by the LDBEN (BRASIL, 2017e). This tiny participation of the Union brings serious consequences for Brazilian education, since the investment capacity of the federative units and municipalities is substantially lower, which contributes to the precariousness of high school and basic education in general. Nevertheless, this is only one serious problem surrounding High School.

According to the PNAD 2006, access to secondary school is profoundly unequal. Considering people between 15 and 17 years old, among the poorest 20%, only 24.9% were enrolled in high school, while among the richest 20%, 76.3% attended this stage of education. [The ethnic-racial cut shows that only 37.4% of the black youth had access to high school, against 58.4% of the white youth. The quality of education, measured by the exams, is also marked by inequalities. The Basic Education Development Index (IDEB/2005) was 3.4 for national high schools. For students in private schools, it was 5.6, and for those in public schools, 3.1 (KRAWCZYK, 2009, p. 5)13.

The socioeconomic and ethno-racial inequalities have also added the discrepancies that oppose different regions of the country, such as the southeast region, with 76.3% of its youth in high school, to the detriment of 33.1% of northeastern Brazil (KRAWCZYK, 2009, p. 5). There is also a subjective component, identified by Krawczyk (2009), among teachers and students, which concerns the lack of interest, demotivation, and lack of identity. Zibas (1992), in the 1990s, when weaving a debate about the scientific production focused on high school education, attributed this lack of identity to historical issues and the inconsistency of educational policies that focus on it.

Indeed, it can be inferred that, in concrete terms, even today, high school education remains the most controversial, problematic, and unequal stage of Basic Education in Brazil. The scenario was worsened by the execution of the impeachment process that ousted President Dilma Rousseff in August 2016, which, as Lombardi and Lima (2018, p.52) tell us, brought to power a government of an antinational, anti-popular, and anti-democratic character. This is the context of the formulation of Law 13.415/17, which has an unequal, problematic, and amorphous high school as its object.

THE LINES OF FORCE OF LAW No. 13.415/17

To begin the discussion, it is necessary to understand that Law 13.415/17 represents, like several of its predecessors, a government policy; that is, it is the molding of education to the political project of the group that holds power in this case, as previously emphasized, a ruling elite of neoliberal bias, aligned with the interests of the productive sectors and big capital, which usurped power through a parliamentary coup (MASCARO, 2018; SOUZA, 2017).

From a broader perspective, we can understand that the very political scenario experienced in 2016 is a rupture in the recent history of the still fragile and intermittent Brazilian democracy, which, according to Saviani (2018), is reflected in the inconsistency of education itself in Brazil. In concrete terms, not only did the High School Reform represent a change of direction in the direction of education, but also other provisions, among which the EC no. 95/16, which established the ceiling of public spending, for instance, made the National Education Plan of 2014 and its main goals a dead letter (SAVIANI, 2018). In this context, the school institution is called to adapt the working class to the new dictates of the market and the new context of production and accumulation of capital (LOMBARDI; LIMA, 2018)

Seeking to solve the problems identified in high school throughout Brazil, the Federal Executive Branch, through the figure of President Michel Temer and the Minister of Education, business administrator José Mendonça Bezerra Filho, presented the High School Reform less than a month after the consummation of the parliamentary coup, utilizing provisional measure, as mentioned above. In its very first articles, Law 13.415/17 determines changes concerning the minimum annual workload of high school:

Article.1 Article 24 of Law no. 9394, of 20 December 1996, shall come into force with the following alterations:

“Article 24. I - the minimum annual workload will be eight hundred hours for primary and secondary education, distributed over a minimum of two hundred days of effective school work [...].

§ 1. The minimum annual workload referred to in item I of the caput shall be expanded progressively, in high school, to one thousand four hundred hours, and the education systems shall offer, within a maximum of five years, at least one thousand hours of annual workload, as of March 2, 2017. (BRASIL, 2017a, s.p.).

Therefore, according to the legal text, we can see that the progressive expansion of the workload of high school provides for an increase from the current eight hundred hours to one thousand four hundred hours, divided into at least 200 school days. In other words, the provision of Article 1 of the reform presents us with one of the law’s goals, which is, as the official wording states, the institution of the Policy for Promoting the Implementation of Full-Time High Schools. Nevertheless, no article, paragraph, or item in the Law indicates a deadline for implementing the 1,400-hour workload, determining only five years for the school systems to offer at least 1,000 hours annually, that is, 200 hours more than the current workload. In a simple calculation, this increase represents an inexpressive increase of, on average, one hour per day if we consider the minimum of two hundred school days.

The Policy for Promoting the Implementation of Full-Time High Schools also includes eight other articles of the reform, which provide for the transfer of resources to schools that implement full-time education and meet certain requirements and targets. However, paragraph 2 of Article 14 is emphatic when it states that “The transfer of resources will be made annually, from a single amount per student, respecting the budgetary availability for attendance, to be defined by an act of the Ministry of Education” (BRASIL, 2017a, our emphasis). Thus, it is understood that the transfer of resources to schools, in a context of austerity policies such as EC no. 95/16, is undermined by the base and that MEC, for its part, appears armed with a legal device that allows it to exempt itself from responsibility for the promotion of full-time high school education.

In legislating on the High School curriculum, the text of the Reform delegates to the Common National Curricular Base (BNCC) the definition of the rights and learning objectives, which should incorporate four areas of knowledge: “I - Languages and their technologies; II - Mathematics and its technologies; III - Natural Sciences and their technologies; IV - Applied Humanities and Social Sciences” (BRASIL, 2017a). From this, we can already measure the importance of the BNCC in implementing Law 13.415/17.

Another point to note is that the legal provision in Article 3, Paragraph 3, provides only that Portuguese and Mathematics are compulsory components in the three years of high school. The greater importance given to these contents refers directly to the organizational logic of the great national evaluations14, which assess the quality of education based on the performance of young people in Portuguese and mathematics.

The changes related to the curriculum do not stop there, and therein lies what, if not the main proposition of the high school reform, is, as we will show later, one of the central pillars of support for the propaganda produced by the MEC: the creation and inclusion of the so-called formative itineraries.

Article 4 of Law no. 13.415/17 amends Article 36 of LDBEN and states:

The high school curriculum will be composed by the Common National Curricular Base and by formative itineraries, which should be organized through the offer of different curricular arrangements, according to the relevance to the local context and the possibilities of the educational systems, namely:

I - languages and their technologies;

II - mathematics and its technologies;

III - natural sciences and their technologies;

IV - applied humanities and social sciences;

V - technical and professional training.

Based on the above, we can understand the main thrusts of Brazil’s most recent high school reform: the promotion of comprehensive education and the flexibility of the curriculum through training itineraries. Nonetheless, beyond the possible interpellations based on the legal text, Law no. 13.415/17 was the object of an intense advertising campaign whose content produced an official discourse about its assumptions and goals. The next section will present the analysis of this content and these discourses.

THE ADVERTISEMENTS OF THE HIGH SCHOOL REFORM EMBODIED IN LAW No. 13.415/17: FUNDAMENTAL AXES AND COERCIVE ELEMENTS

As indicated in the introduction, the advertisements about Law no. 13.415/17 appeared in the context of large demonstrations by social sectors against the reform and the changes that were being proposed. As Saviani stated: “[...] the government, instead of considering the criticism by reviewing the orientation printed to the reform, ignored them and launched an aggressive advertising campaign with many daily insertions in the media [...]” (SAVANI, 2018, p. 40). It is precisely on the part of this campaign that our research focuses on at this point. The analysis results conducted through the Iramuteq software allowed us to identify the fundamental axes that make up the ads.

The first observation refers to identifying a common central axis in all the advertisements examined, composed of the expression “High School” and the word “new.” In fact, “New High School” is the title, or motto, through which the discourse in the advertisements deals with and “sells” Law 13.415/17. The individualized examination of the advertisements also shows us that, in each advertisement, the aforementioned common axis is added to other terms that, as a rule, are not repeated between one advertisement and another, which denotes that each one has its aspects.

However, despite clear differences in content, the meanings of the advertisements are complementary, and although particular purposes can be identified, they are all focused on a common goal: the exaltation of the High School Reform. The evidence of the existence of this common goal begins with the very treatment given by the official discourse to the reform, the already mentioned title “New High School.”

As described above, the high school context in Brazil is highly adverse. First, the inequalities (internal to the school and external to it) make it the most problematic stage of Basic Education, with terrible results in major evaluations, including when we also look at private institutions15. At the same time, High School arouses in its main players (teachers and students) a range of negative feelings, including disinterest and discouragement, as well as a historical lack of identity. Given this scenario, the State found the perfect justification to implement a reform: “[...] High School presents results that demand measures to reverse this reality because a high number of young people are out of school and those who are part of the education systems do not have good educational performance [...]” (BRASIL, 2016a, p. 9).

This quote, part of the government’s defense and the withdrawal of the rapporteur of ADI 5.599, is consistent with what is found in the content of the advertisements. In A4, three characters, a father, a mother, and a son, have the following conversation: “- Hmm, very well, son, and is this new High School coming right away? - Yes, Dad, we can’t wait any longer. There are too many young people out of school. - Yes, I’ve been researching. More than 2 million young people are out of school” (BRASIL, 2017c). This passage of the advertisement refers to the high dropout rates from high school in Brazil, although it does not discuss the causes of the problem, which includes the need for young people from the less favored classes to work to survive. The official discourse also alludes to the discouragement of young people in High School that, according to the report, is caused by the distance of compulsory subjects from the reality of young people and the world of work (BRASIL, 2016a).

In advertisements, on the other hand, one of the promises is to “make learning more stimulating and compatible with your (the youth’s) reality!” (BRASIL, 2016c). These arguments make bringing freshness and novelty to high school urgent. This is where the scene for the “New High School” and its legitimization is created. Therefore, the concept of “new” is one of the main elements of the advertisements about Law no 13.415/17.

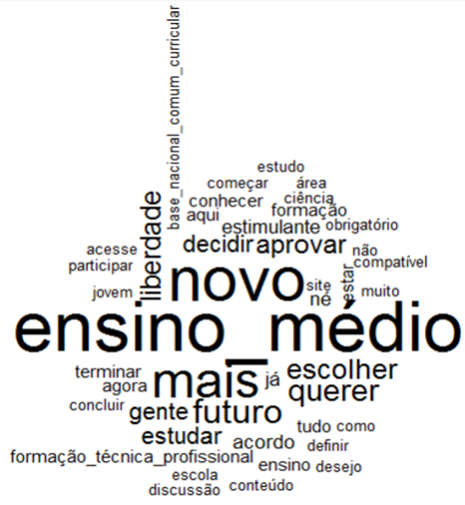

The term “new” does not logically appear as an isolated component. On the contrary, we will see that it is just one component of a range of other terms that make up the fundamental axes that configure a powerful coercive apparatus of the official advertising discourse. For a better illustration, please see Figure 1 as a basis.

Since this is a marketing campaign about high school reform, it seems obvious that the expression “high school” is the highlight in the results of the content analysis of the advertisements. In the same way, we can understand the reason for its prominence in the word cloud when we see that the word “new”, together with the expression “highlight”, makes up the title of the reform. Excluding these elements, others take the scene: “more,” “choose,” “decide,” “freedom,” “want,” “study,” “future,” and “stimulating,” etc.

Figure 2, in addition to highlighting the words, shows the connections between them in the advertisements. The adverb “more” ]mais[, for example, highlighted in the word cloud (Figure 1), is in direct connection with the noun “freedom” [liberdade], the verb “choose” [escolher], the adjective “stimulating” [estimulante], and the adverb “already” [já]. “Future” [futuro], nevertheless, appears closely connected to the words “teaching”[ensino], “desire” [desejo], and “finish” [terminar]. Finally, the verb “want” [querer] is associated with the terms “decide” [decidir] and “agreement” [acordo]. All these connections, which appear as branches in the similarity graph, start from the same central point, composed of the word “new” [novo] and the expression “High School” [ensino médio].

Then, by starting from this structure and casting light on the transcripts of the advertisements, we understand the meaning contained in these links of words. In the speeches, the “New High School” will give young people the freedom to choose what they want to study, according to their ambitions and personal project for life and the future. Moreover according to the advertisements, teaching will become more stimulating and even more compatible with the reality of the students. Therefore, according to the government, it is a reform proposal for creating a new high school that is attentive to the students’ desires. In the language of advertisements:

With the New High School, teaching in schools has everything to become more stimulating and more in line with what we really want. [...] The most important thing is that we will be free to choose among four areas of knowledge to deepen our studies, right? Everything is according to my dreams and what I want for my future! (BRAZIL, 2017b).

The appeal to the issue of freedom and the other terms used in this discursive construction is further reinforced in the titles of the advertisements themselves: “With the New High School, you have more freedom to choose what to study!” (BRASIL, 2016b) and “The New High School will be more stimulating and compatible with your reality! We also notice the existence of the adverb “already,” which presupposes an answer given by the advertisements about when the changes will occur.

From what was exposed, we can conclude that the official discursive construction contained in the advertisements about the high school reform embodied in Law no. 13.415/17 goes through two fundamental and complementary axes: the proposition of a new and reinvigorated high school (first axis) that, in turn, brings as main advance the possibility of choice by the student for what to study (second axis). The coercive apparatus is on account of the focus given to subjective issues as the supposed attention to the wishes of young people and the construction of education compatible with their reality and wishes for the future. Beyond the discourse, however, we seek, within the limits of this research, to counterbalance the government rhetoric with the assumptions of the Law and the reality of High School in Brazil.

BETWEEN WHAT ADVERTISEMENTS SAY, THE LAW, AND THE REALITY OF BRAZILIAN HIGH SCHOOLS

First, it is necessary to understand that the freedom so vehemently vaunted by advertisements about the high school reform is based on what is stated in Article 4 of Law no. 13.415/17, which provides for the new curricular organization and determines the offer of formative itineraries. It is, therefore, in the students’ choice that the supposed freedom would reside, since, once the current subjects are no longer compulsory, young people would direct their school career according to their wishes. This argument, however, is not supported by more careful analysis. Let us note that, according to Article 4, the offer of formative itineraries is subject to the “relevance to the local context and the possibility of the education systems” (BRASIL, 2017b). In addition, none of the Law’s provisions determine how many itineraries should be offered per school, defining only that there should be at least one in each institution.

Faced with a reality in which not even the universality of secondary education is assured, let alone its quality, as mentioned above, what can be expected, in concrete and material terms, of the real possibility of the education systems offering the itineraries? In the same way, given the socioeconomic, ethno-racial, and regional inequalities that mark the quality and access to High School in a country of continental dimensions, we can question the “relevance to the local context” mentioned in the legal text. These findings point to a scenario where not only does the State seem to shirk its responsibility to improve high school effectively, but it also reinforces inequalities by irresponsibly equalizing and generalizing particular issues that permeate the already fragile public education system and high schools in Brazil. Added to this is the fiscal austerity regime and measures such as EC no. 95/16.

In these fears, young people in large urban centers and private schools will be able to enjoy, in concrete terms, an education with more freedom. In contrast, the vast majority, who use the public school systems, will have their possibility of choice undermined at the bottom given the terrible material conditions of the networks. In other words: the supposed freedom, the main coercive element and one of the fundamental axes of the advertisements about the high school reform is a fallacy built on rhetoric to facilitate the conditions for the implementation of the high school reform and ensure support among the population. The effectiveness of the discourse, in turn, resides in its capacity to penetrate the imagination of young people disillusioned and dissatisfied with the school experience, especially at this stage. With a new and modern look, in which slang and everyday representations are present, the advertisements reach the desired profile and target audience.

Second, it should be noted that just as the advertisements build a fallacy about the freedom brought by the “New High School,” the very use of the term “new” is questionable since various authors have noted the similarities and approximations with other educational reforms. Kuenzer (2017), for example, argued about the similarities between the points that subsidized Law no. 13.415/17 and Decree no. 2.208/97, a policy for vocational education that occurred during the height of the neoliberal agenda of the Fernando Henrique Cardoso government.

Oliveira (2017), in turn, defends that Law no. 13.415/17 is the most comprehensive update of the school reform of the civil-military regime. Law no. 5.692/71, which is necessary due to the need for a new worker for a new context of capital accumulation and production that emerged with the so-called productive restructuring, when an increasingly globalized market, with the incorporation of microelectronics to production processes, made Taylorism/Fordism no longer the founding production category. This gave way to a flexible production influenced by rapid scientific and technological development; in this change lies the need for a new worker, conformed to a new exploitation pattern, which can be known as a 21st-century pattern.

This issue leads us to reflect on the problem of professionalization, one of the main pillars of Law no. 13.415/17 and present in the advertisements, as shown in Figure 2, in which we can see the close connection between the words “High School,” the verb “to conclude,” and the expression “technical and professional training.” From this analysis, we understand that the official discourse of the advertisements encourages the student to seek high school completion through technical and professional training, encouraging early entry into the labor market.

Nevertheless, according to Oliveira (2017, p.19), the high school reform has “practices that worsen the inequality of access to knowledge by different social classes and aim to conform the 21st-century worker to the new pattern of exploitation required by the current capitalist economy.” Such maintenance confirms the dual character of our education, maintaining the historically constituted unequal pattern in which the academic trajectories of two distinct social classes were marked, being that, on one side, is the trajectory destined to the children of the elites, which always pointed to the continuation of studies in Higher Education and training aimed at the leading positions in the productive sector, with better remuneration. On the other hand, there is restricted training for work aimed at the children of the working class, which has as one of its consequences the early entry of young people into the labor market in peripheral functions in the dynamics of production (KUENZER, 2009). Thus,

Implementing early professionalization, along the lines of Law 5.692/71 of the civil-military dictatorship, the new High School Reform seeks to impose the technicist farce, representing a setback in the debate fed by expectations created by the redemocratization process, marked by the struggle in defense of public school [...] (LOMBARDI; LIMA, 2018, p. 57)

From what was exposed, we understand that the “New High School” does not represent, in fact, a new perspective for high schools in the search for improving their quality. It behaves, first of all, as a search for the adequacy of the school institution to the new standard of capitalist exploitation, which aims to conform the worker to the current regime. As the philosopher István Mészaros tells us

Institutionalized education, especially in the last 150 years, has served — as a whole — the purpose of not only providing knowledge and the personnel needed for the expanding productive machine of the capital system, but also of generating and transmitting a framework of values that legitimizes the dominant interests, as if there could be no alternative to the management of society [...] (MÉSZAROS, 2008, p. 35).

In this sense, we can infer that Law no. 13.415/17 maintains the unequal logic of high school in Brazil and its function as a tool to legitimize exploitation and the capitalist system, being, therefore, consistent with what is observed in educational policies in the last four decades in the country.

CONCLUSIONS

The high school reform embodied in Law no. 13.415/17 is Brazil’s latest major public educational policy. Managed in the instances of power taken by assault after the execution of the 2016 parliamentary coup, it occurred in the wake of a series of anti-popular measures (counter-reforms) and a rigid neoliberal-based fiscal austerity policy. Given this, our work sought to analyze the advertisements about the 2017 high school reform, making counterpoints with the reality of the Brazilian educational system and taking into account socioeconomic issues, interpretations of the text of the law itself, and historical perspectives of high school policies in Brazil.

In this context, the reform was leveraged by a massive marketing campaign using a modern, democratic, and attractive dressing to extol the Law and its determinations. Thus, behind a “pretty cover,” the State built an official discourse that was based on two fundamental and complementary axes: the proposition of a new and reinvigorated High School and the defense of greater freedom of choice for the students in terms of what to study, according to their vocations, desires, and ambitions for the future. As already mentioned, the effectiveness of this coercive apparatus rests on the focus given by advertisements to subjective issues of desire and motivation, which are generated by the lack of interest and discouragement on the part of young people at this stage of education, as verified by Krawczyk (2009) and Zibas (1992), among other researchers.

Nonetheless, our findings showed that the elements present in the official discourse contained in the content of the advertisements do not hold up if put in the light of socioeconomic issues related to the reality of the Brazilian educational system, especially the public one, interpretations of the text of the Law and the survey of policies in the recent history of High School. In this sense, we can state that Law no. 13.415/17 brings to this stage of Basic Education the vision of a conservative group with a privatistic and market-oriented bias, which coincides with the policies seen in the 1990s in Brazil in the context of the neoliberal adjustment. Moreover, the professionalization proposal contained in the Law, and defended in the advertisements, appears to us as a clear resumption of Law No. 5.692/71, the educational reform of the civil-military regime, which failed (OLIVEIRA, 2017; LOMBARDI; LIMA 2018; SAVIANI, 2018).

This study also enabled us to identify similarities regarding the discourses built by the governments in each policy, even separated by more than four decades, both alluding to the search for young people’s satisfaction with school and treatment of the respective policy as a solution to the problems of education in Brazil. Nevertheless, despite the official rhetoric, it can be inferred that Law no. 13.415/17 carries in its core the keynote verified in the overwhelming majority of public educational policies in recent decades: the adaptation of education to the interests of big capital and the productive sectors, aiming at the supply of labor for the capitalist machine and thus perpetuating the class division, the extraction of surplus value, and the exploitation of the economic and ruling elites towards the working class.

In this scenario, the differences between the Laws and their determinations, and the discourses, are justified by the need to “update” the coercive apparatuses in different contexts. This explains, for example, the difference in the form in which the discourses are presented: regarding Law No. 5.692/71, in a context of blatant authoritarianism, a technical opinion that circulated in the very dependencies of the power (Opinion No. 45 of 1972); in an apparent regime of democracy, or veiled authoritarianism, political propaganda was used as a tool of coercion and formatting of opinions related to Law No. 13.415/17.

Thus, the title “New High School” does not fit the reform proposal proposed by the Temer government, nor does it support the recovery of the recent history of high school education in Brazil. In the same way, as we have already seen, the issue of freedom, which was propounded numerous times by the advertisements, despite being based on Law no. 13.415/17, configures itself as a clear manipulation of the latter’s curricular proposal, since Article 4 defines that the offer of itineraries will be organized according to the possibility of the education systems and the relevance to the local context. In a scenario of extreme regional inequalities and the context of fiscal austerity policies such as the EC no. 95, it can be said that this supposed freedom is undermined at the base for those who use the public education systems.

Based on this, it can be said that the official and advertising discourse on Law no. 13.415/17 presents fallacious content, which distorts and manipulates the interpretations of the text of the Law itself, whose goal is to ensure the conditions for the implementation of an educational reform that suits those interested in maintaining the social status quo, in which an elite dominates and directs society and relegates to the rest a adverse socioeconomic reality in which not even education was guaranteed for all.

REFERENCES

BRASIL. Censo escolar da educação básica 2016 - Notas estatísticas. Brasília, DF, 2017e. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Emenda constitucional nº 95, de 15 de dezembro de 2016. Publicada no Diário Oficial da União em 15 de dezembro de 2016. 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.467, de 13 de julho de 2017. Publicada no Diário Oficial da União em 14 de julho de 2017. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.415, de 16 de fevereiro de 2017. Publicada no Diário Oficial da União em 17 de fevereiro de 2017. 2017a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Com o Novo Ensino Médio, você tem mais liberdade para escolher o que estudar! (30seg). 2016b. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kdERkLO3eTs . Acesso em: 5 de jun. de 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. O Novo Ensino Médio vai deixar o aprendizado mais estimulante e compatível com a sua realidade! (30seg). 2016c. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7_Fdhibi0yQ . Acesso em: 5 de jun. de 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. O Novo Ensino Médio vai melhorar a educação dos jovens!(2min). 2017b. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C-M_ewoa0iY . Acesso em: 5 de jun. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Com o Novo Ensino Médio você pode decidir o seu futuro! (2min). 2017c. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bIFgyTLIv4Q . Acesso em: 6 de jun. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. O Novo Ensino Médio vai ser mais estimulante e compatível com a sua realidade! (2min). 2017d. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qp0_kuVNskk&t=4s . Acesso em: 6 de jun. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério Público Federal. Procuradoria Geral da república. No 313893/2016-AsJConst/SAJ/PGR. Ação direta de inconstitucionalidade 5.599/DF e apenso. Relatoria: Ministro Edson Fachin Requerente: Partido Socialismo e Liberdade (PSOL) Interessada: Presidência da República. 2016a, 46pp. [ Links ]

CHOMSKY, Noam. Mídia - Propaganda Política e Manipulação. Trad. Fernando Santos. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2014. [ Links ]

CONSELHO FEDERAL DE EDUCAÇÃO. Parecer CFE nº. 45/72 - CEPSG - Aprovado em 12-01-72. São Paulo: Martins Fontes. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://siau.edunet.sp.gov.br/ItemLise/arquivos/notas/parcfe45_72.doc . Acesso em9 de jun. 2020. [ Links ]

DUARTE, Adriana. Tendências das reformas educacionais na América Latina para a educação básica nas décadas de 1980 e 1990. In: FARIA FILHO, Luciano Mendes de; NASCIMENTO, Cecília Vieira do; SANTOS, Marileide Lopes dos. Reformas educacionais no Brasil: democratização e qualidade da escola pública.. Belo Horizonte: Maza Edições, 2010. p .161-185 [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Eliza Bartolozzi; SILVA, Mônica Ribeiro da. Centralidade do Ensino Médio no contexto da nova “ordem e progresso”. Educação & Sociedade (Impresso), Campinasv. 38, p. 287-292, 2017. [ Links ]

GERMANO, José Willington. Estado militar e educação no Brasil (1964-1985).. São Paulo: Cortez; Campinas: Unicamp, 1993. [ Links ]

KRAWCZYK, Nora. O Ensino Médio no Brasil.. São Paulo: Ação Educativa, 2009. [ Links ]

KUENZER, Acacia Zeneida (org.) Ensino Médio: Construindo uma proposta para os que vivem do trabalho. 6ª Edição. São Paulo: Cortez Editora, 2009. [ Links ]

KUENZER. Acacia Zeneida (org). Trabalho e escola: a flexibilização do Ensino Médio no contexto da acumulação flexível. Educação & Sociedade. (Impresso), Campinas, v. 38, p. 331-354, 2017. [ Links ]

LOMBARDI, José Claudinei; LIMA, Marcos R. Golpes de Estado e educação no Brasil: a perpetuação da farsa. In: KRAWCZYK, Nora; LOMBARDI, José Claudinei (Orgs.). O golpe de 2016 e a educação no Brasil.. Uberlândia: Navegando Publicações, 2018. p.47-62 [ Links ]

MASCARO, Alysson Leandro. Crise e Golpe.. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2018. [ Links ]

MEDEIROS FILHO, Barnabé. O golpe no Brasil e a reorganização imperialista em tempo de globalização. In: KRAWCZYK, Nora; LOMBARDI, José Claudinei (Orgs.). O golpe de 2016 e a educação no Brasil.. Uberlândia: Navegando Publicações, 2018. p. 5-25. [ Links ]

MÉSZAROS, István. A educação para além do capital.. São Paulo: Boi Tempo Editorial. Nova edição, ampliada, 2008. [ Links ]

MORAES, Roque. Análise de conteúdo. Revista Educação., Porto Alegre, v. 22, n. 37, p. 7-32, 1999. [ Links ]

NETTO, José Paulo. Introdução ao estudo do método de Marx.. 1ª Edição. São Paulo: Editora Expressão Popular, 2011. [ Links ]

NOSELLA, Paolo; BUFFA, Ester. Instituições Escolares: por que e como pesquisar.. Campinas-SP: Editora Alínea, 2009. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Fernando Bonadia de. Entre Reformas: tecnicismo, neotecnicismo e educação no Brasil. RETTA - Revista de Educação Técnica e Tecnológica em Ciências Agrícolas., v. 9, p. 19-39, 2017. [ Links ]

RAMOS, Marise. A educação tecnológica como política de estado. In: OLIVEIRA, Ramon (org.). Jovens, Ensino Médio e Educação Profissional: Políticas Públicas em Debate.. Campinas: Papirus, 2012. p.9-46. [ Links ]

ROMANELLI, Otaíza de Oliveira. História da Educação no Brasil 1930-1973.. 30ª Edição. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2006. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, Demerval. A crise política e o papel da educação na resistência ao golpe de 2016 no Brasil. In: KRAWCZYK, Nora; LOMBARDI, José Claudinei (Orgs.). O golpe de 2016 e a educação no Brasi.l. Uberlândia: Navegando Publicações, 2018. p. 27-45. [ Links ]

SAVIANI. História das Ideias Pedagógicas no Brasil. 4ª Edição. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2013. [ Links ]

SOARES, Maria Clara Couto. Banco Mundial: Políticas e reformas. In: TOMMASI, Lívia de; WARDE, Mirian Jorge; HADDAD, Sérgio(orgs.). O Banco Mundial e as Políticas educacionais. São Paulo: Cortez Editora, 2007. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Jessé. A Elite do Atraso: Da Escravidão à Lava Jato. São Paulo: Ed. Leya, 2017. [ Links ]

ZIBAS, Dagmar Maria Leopoldi. Ser ou não ser: O debate sobre o Ensino Médio. Cad. Pesq. São Paulo, n.80, p.56-61, fev.,1992. [ Links ]

1This paper presents results and conclusions of a research project that was funded by the Research Support Foundation of the State of Minas Gerais - FAPEMIG between March 2018 and February 2019.

2The translation of this article into English was funded by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais - FAPEMIG, through the program of supporting the publication of institutional scientific journals.

4The actions towards the dismantling of the working class struggle have been followed by the current government, presided over by Jair Messias Bolsonaro, with the edition of the Provisional Measure No. 873 of March 2019 that suspends the collection of the union contribution in payroll, disarticulating the unions and emptying their power to act.

5Hence, see the Dossier “(Des)Ocupar é Resistir?” of the journal Educação Temática Digital, Campinas, SP v.19 n.1 p. 73-98 jan./mar. 2017.

6Until January 2022, according to the Jusbrasil website, the proceedings related to Direct Lawsuit on Unconstitutionality No. 5599 are still at the STF, and its last update was on August 24, 2017, with the following order: “Under the terms of Article 87, I, of the Internal Rules of the Supreme Court, I hereby make the entire content of the respective Report available in written form, also providing isonomic and simultaneous knowledge to the requesting party, the Office of the Solicitor General of the Union, and the Office of the Attorney General of the Republic. The report shall be published. Send notice of the decision. Brasília, August 23, 2017. Minister Edson Fachin.” Available at: https://www.jusbrasil.com.br/processos/144945840/processo-n-5599-rs-do-tjrs. Accessed on 05 Apr. 2020.

7In advertisements A1 and A2, the scene takes place in a large auditorium. Several young characters, one by one, express themselves positively about the high school reform, interspersed with the official narrator’s speeches.

8In advertisements A3, A4, and A5, the scene takes place with young or adult characters in different routine situations, such as a study circle in a library, conversation between parents and child, and conversation between friends.

9The U.S. interest in Brazil increased significantly after 2006, when Petrobras discovered a gigantic oil reserve off the Brazilian coast, the so-called ‘Pre-salt’ layer. The immediate reaction of the Lula administration was to guarantee the monopoly of exploration of the resources by the Brazilian state-owned company.

10Duality here refers to the division of secondary school into professional and propaedeutic education, one of the central points of Gustavo Capanema's reforms during the first government of Getúlio Vargas (1930-1945). On this, see Saviani (2013).

11As an example we can cite the creation of the Centros Integrados de Educação Pública, the CIEPS, idealized by Darcy Ribeiro during the first government of Leonel de Moura Brizola in the state of Rio de Janeiro (1983-1987).

12In Brazil, it was only in 2009, with Constitutional Amendment 59, that High School and Early Childhood Education became compulsory. However, this condition is still controversial, since the text dictates that it is compulsory only for students between 4 and 17 years old.

13It is important to point out that both the indicators of public schools and private institutions show insufficient performance for high school, although the most fragile and serious scenario is that of the public networks (KRAWCZYK, 2009, p.5).

14As an example of these assessments we can cite the System for the Evaluation of Basic Education (SAEB), composed of the National Assessment of Basic Education (ANEB) and the National Assessment of School Performance (ANRESC), the Prova Brasil, aimed at students from the 5th to 9th grades of elementary school. The results of both evaluations are the basis to calculate the Basic Education Development Index (IDEB), whose scope includes performance in the curricular components of Portuguese Language and Mathematics.

15In the IDEB calculation, for instance, the index obtained in 2017 for public schools was 3.5, representing a stagnation in relation to 2015 and, accumulated over the last 12 years, a growth of 0.5, while the expected goal for the country, in the same year of 2017, was 4.4. Still according to this index, the private network presents an IDEB of 5.8, which is below the stipulated goal of 6.7, but substantially higher than in the public network. Indeed, the disparity draws attention, even when we consider only the learning index: 6.03 in the private network, against 4.24 in the public system. Available at: https://www.qedu.org.br/brasil/ideb?dependence=4&grade=3&edition=2017. Accessed on April 1, 2020.

Received: January 10, 2022; Accepted: July 07, 2022

texto en

texto en