Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educação em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0102-4698versão On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.39 Belo Horizonte 2023 Epub 23-Fev-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469839794

ARTICLE

SEX EDUCATION: AN ANALYSIS OF BRAZILIAN LEGISLATION AND OFFICIAL DOCUMENTS IN DIFFERENT POLITICAL CONTEXTS

1Universidade Federal do ABC. Santo André, SP, Brazil.

2 Universidade Federal do ABC. Santo André, SP, Brazil.

The provision of Sexuality Education in schools can significantly contribute to the reduction of violence motivated by issues related to gender and sexuality. This Sexuality Education needs to go beyond purely biological issues, addressing several other themes, such as body, pleasure, consent, and violence in addition to more obvious issues of gender, sexuality and diversity. However, in order to carry it out, teachers need to have the support of official documents and legislation. This research aims to verify how issues concerning Sexuality Education, gender and sexuality appear in laws, decrees and other publications that guide Brazilian Education as well as to relate them to the socio-political contexts in which they were published. To achieve our goal, we searched for these documents, covering the period from 1990 to 2018, and we focused our analysis on twenty-eight of them. The analysis showed that, in fact, the legislation not only allows, but determines that Sexuality Education be in schools. However, different political contexts have a great impact on the way in which Sexuality Education appears in the documents, sometimes explicitly, sometimes subjectively and diluted in the discourse of diversity and recently, completely silenced. In addition, recurrent cycles of advances and setbacks in different political contexts since re-democratization have culminated in gaps and discontinuities in Sexuality Education policies, impeding the development of a specific law on the subject and preventing its consolidation within Brazilian schools.

Keywords: Sex Education; gender; sexuality; legislation

A oferta de Educação Sexual nas escolas pode contribuir de forma significativa para a diminuição das violências motivadas por questões relativas a gênero e sexualidade. Essa Educação Sexual precisa ir além das questões puramente biológicas, abordando diversas outras temáticas, como corpo, prazer, consentimento e violência, além das questões mais óbvias de gênero, sexualidade e diversidade. Porém, para realizá-la, professoras, e professores, precisam ter o respaldo dos documentos oficiais e legislação vigente. O objetivo desta pesquisa é verificar como aparecem as questões concernentes à Educação Sexual, gênero e sexualidade nas leis, decretos e demais publicações norteadoras da Educação brasileira, assim como relacioná-los aos contextos sócio-políticos em que foram publicados. Para isso, realizamos uma pesquisa por esses documentos, abrangendo o período de 1990 e 2018, e focamos nossa análise em vinte e oito deles. A análise demonstrou que, de fato, a legislação não só permite, mas determina que a Educação Sexual seja realizada nas escolas. No entanto, os diferentes contextos políticos possuem grande impacto na maneira como a ela aparece nos documentos, ora de maneira explícita, ora subjetiva e diluída no discurso da diversidade e, no momento recente, completamente silenciada. Além disso, recorrentes ciclos de avanços e retrocessos nos diferentes contextos políticos desde a redemocratização culminaram em políticas de Educação Sexual cheias de lacunas e descontinuidades, sem que fosse desenvolvida uma lei específica sobre o tema, impedindo, assim, sua consolidação dentro das escolas brasileiras.

Palavras-chave: Educação Sexual; gênero; sexualidade; legislação

La realización de Educación Sexual en las escuelas puede contribuir significativamente a la reducción de la violencia motivada por cuestiones relacionadas con el género y la sexualidad. Esta Educación Sexual necesita ir más allá de las cuestiones puramente biológicas, abordando varios otros temas, como el cuerpo, el placer, el consentimiento y la violencia, además de las cuestiones más obvias de género, sexualidad y diversidad. Por lo tanto, para ello, los profesores y catedráticos deberán sustentarse en los documentos oficiales y la legislación vigente. El objetivo de esta investigación es verificar cómo los temas relacionados con la Educación Sexual, el género y la sexualidad aparecen en las leyes, decretos y otras publicaciones que orientan la Educación Brasileña, así como también cómo se relacionan con los contextos sociopolíticos en los que fueron publicados. Para ello, hicimos una investigación de estos documentos, cubriendo el período de 1990 a 2018, y enfocamos nuestro análisis en veintiocho de ellos. El análisis mostró que, en efecto, la legislación no sólo permite, sino que determina que la Educación Sexual se realice en las escuelas. Sin embargo, los diferentes contextos políticos tienen un gran impacto en la forma en que la Educación Sexual aparece en los documentos, a veces de manera explícita, a veces subjetiva y diluida en el discurso de la diversidad y, no recientemente, completamente silenciada. Además, ciclos recurrentes de avances y retrocesos en diferentes contextos políticos desde la redemocratización culminaron en políticas de Educación Sexual con lagunas y discontinuidades, aunque se elaboró una ley específica sobre el tema, impidiendo su consolidación en las escuelas brasileñas.

Palabras clave: Educación Sexual; género; sexualidad; legislación

INTRODUCTION

Several authors present definitions of what they understand by School Sexuality Education (BRUESS, GREENBERG, 2009; NUNES, SILVA, 2006; WEREBE, 1998; FIGUEIRÓ, 1996). In line with them, we understand here that School Sexuality Education is the manner in which the school provides students, intentionally and systematically, with information and reflections on a wide range of topics that are necessary for their health, well-being and comprehensive and emancipatory development, so that they can better understand themselves and one another, as well as make decisions about their sexual life.

A systematic work on Sexuality Education that goes beyond biology and involves matters of gender and sexuality still arouses quite heated reactions and refutations. Mothers, fathers and guardians, representatives of public and private institutions, religious groups, and even teachers sometimes take a stand against it. Such revulsion, in some cases, because of the belief that sexuality is restricted to sexual desire and the sexual act. Thus, it is also believed that the family is the sole responsible for discussing these matters. However, it is important to point out that sexuality comprises several other aspects of human life and that it is also manifested in different ways at all stages of development. Sexuality, within the scope of this research, is interpreted as “a general description for the series of beliefs, behaviors, relationships, and identities socially constructed and historically modeled” (WEEKS, 1999, p. 43).

Aligned with the discourse that Sexuality Education would be the exclusive responsibility of the family, several conservative groups seek, as if it were possible, to silence it in schools. These conservative voices are supported by a union of ultraliberal ideologies, religious fundamentalisms, and the anti-communism that has been resurrected in the last decade and labeled as an enemy of patriotism. And, inevitably, schools did not go unnoticed in this context. They instead became the battle ground of a series of political and ideological clashes, being accused of developing a supposed Marxist indoctrination and promoting something called “gender ideology”. This new enemy was quickly accepted and used for self-promotion by more conservative political figures and the fundamentalist caucus (MIGUEL, 2016).

The entire discourse of these movements demonstrates a complete disconnection from what is understood as Sexuality Education. For some of the people who oppose it, it would be a way of inciting sexual activity in children and young people. In addition, it would have the purpose and ability to promote deviant sexual behavior, that is, those in disagreement with the cis-heteronormative standard. However, this group is also formed by another party, made up of some political and religious leaders, who use the Sexuality Education agenda and the fallacy of gender ideology as a smokescreen to divert the public's gaze away from political and economic interests.

In this context, speeches and projects opposing the carrying out of Sexuality Education practices in schools proliferated, to the point that “approximately 60 bills were processed or are being processed in the National Congress and legislative houses aiming to prevent the political and ideological indoctrination of students by teachers in schools.” (FURLANETTO et. al. 2018, p. 554). This is the scenario in which teachers find themselves in schools. The exercise of teaching becomes a place of insecurity, uncertainty, and fear.

Seeking to better understand this scenario, in addition to verifying whether teachers are backed up by law to carry out systematic practices of Sexuality Education in schools, we set out to verify how it materializes in Brazilian official documents: laws, decrees, and other publications that guide Education and, also, how it relates to the socio-political contexts of the country since the establishment of the democratic regime. For this, we start from the research question “What do official Brazilian documents say, in different political contexts, about working with an emancipatory Sexuality Education, which includes gender and sexuality issues, in the school environment?”

The importance of broadening the understanding of the approach to Sexuality Education in Brazilian legislation is justified by the fact that Brazil still does not have any specific law on Sexuality Education. In a survey of official documents on Sexuality Education in Brazil and Portugal, Netto (2016) points out that “The Portuguese drafted their first specific law in the field of Sexuality Education in 1984, whereas Brazil, in the 21st century, still doesn’t have a specific law on sexuality or Sexuality Education.” (NETTO, 2016, p. 91)

In addition, in 2021, the World Global Forum report on gender inequality puts Brazil in the 93rd place in the world ranking. The country is also notoriously known as the one which most kills transvestites and transgender people in the world (OLIVEIRA; MOTT, 2020). Here, in an exacerbated way, sex, gender, sexuality, and violence are closely intertwined.

This is also demonstrated by another report on violence in the country. The Gender Violence Map, carried out by the organization Gender and Number, in collaboration with UN Women and the international human rights organization Article 19, showed that the vast majority of murder victims in the country are identified as men; however, these crimes mostly occur outside the home, while the majority of murdered women are victimized within the home. When it comes to the LGBTQIA+ population, the numbers are no less shocking. In 2017, eleven cases of violence against trans people and 214 cases of violence against homo/bi people were registered every day (GENERO E NÚMERO, 2017). It becomes clear then, that gender and sexuality expressions and identities are closely related to one being subject to violence. Moreover, our constructions of masculinity and femininity produce and perpetuate this violence.

It would be at least naive to believe that the school does not take part in how this scenario is structured. Quite the contrary, the school institution is part of a web, an interweaving of extremely complex relationships that shape subjects and societies and, at the same time, is shaped by them. In this entanglement of forces, discourses, propositions, and policies, it is impossible to point out a beginning or an end. School, as part of a society with its cultures and values, and society, as an organism molded, among others, by the school, live a complex feedback cycle. Thereby, we emphasize the importance of promoting Sexuality Education in the school environment so that we can, in some way, bring about changes that improve the scenarios described here.

METHODOLOGICAL COURSE

The research is qualitative because its results are achieved through the researchers' interpretation of the data produced, which, in turn, are permeated by their values and experiences. According to Stake (2011), qualitative research is strongly based on human perception, having as its main characteristics being “interpretive, experiential, situational and personalistic” (STAKE, 2011, p. 24).

We adopted the methodological procedures of documentary research, which, according to Gil (2002), is made through the analysis of untreated documents, or even through an original analysis of documents that have already been treated. In this way, documentary research “extracts the whole analysis from them, organizing and interpreting them according to the objectives of the proposed investigation” (PIMENTEL, 2001, p. 180).

To constitute the data, we returned to the research question: what do official Brazilian documents say, in different political contexts, about working with an emancipatory Sexuality Education, which includes gender and sexuality issues, in the school environment?

We defined that the investigated period would begin on January 1, 1990, since that date marked the first time that an elected president took office after the period of re-democratization. For the final date, we chose January 1, 2019, since that was the end date of Michel Temer's mandate, the last president to complete his cycle in the Presidency until the production of this article.

The terms defined for the search were: Sexuality Education, sexuality, gender, sexual orientation, and sex. As the first inclusion criterion, we chose to use documents related to the school and education. For the second criterion, we defined that we would use all the laws and decrees that also dealt with discrimination, diversity, and health. The third criterion was the inclusion of documents that presented issues related to childhood and youth, education, health, human rights, combating inequalities, violence, and the building of responsible citizenship. As the exclusion criterion, we eliminated documents that were not related to the school and Education.

We searched two places: the Presidency's legislation consultation portal and the Ministry of Education (MEC) portal, particularly the page of the Secretariat of Basic Education (SEB). In the first one, we decided to select only valid legislation. As a systematic procedure, we started our search by inserting the filter “No express revocation” and inserting the previously chosen start and end dates. Initially, the researched term was “Sexuality education”; however, only two results were found. Next, we searched for the word “sexuality”, and, in this case, eight results were found. As the portal does not have an “and/or” search criterion, we started to search for “gender”, “sexual orientation”, “sex” and “diversity” separately and selected all the documents that corresponded to the third inclusion criterion. In the second place, we started our search for official Education documents. In this case, it was not possible to carry out a systematic search, as the documents are presented on the government pages in a dispersed and sometimes apparently hidden manner. Thus, the search was carried out in an exploratory manner, which required a true immersion in the Ministry of Education (MEC) portal, in particular, on the page of the Secretariat of Basic Education (SEB).

Later, confronted by our theoretical references, we found other documents that could be analyzed in our research. Thus, we also included, in our analysis, the educational toolkit of the Projeto Escola sem Homofobia (School without Homophobia Project) and the Orientações Técnicas em Educação em Sexualidade para o Cenário Brasileiro - Tópicos e Objetivos de aprendizagem (Technical Guidelines on Sexuality Education for the Brazilian Scenario - Topics and Learning Objectives), published by Unesco. At the end of this data production process, twenty-eight documents became part of the research.

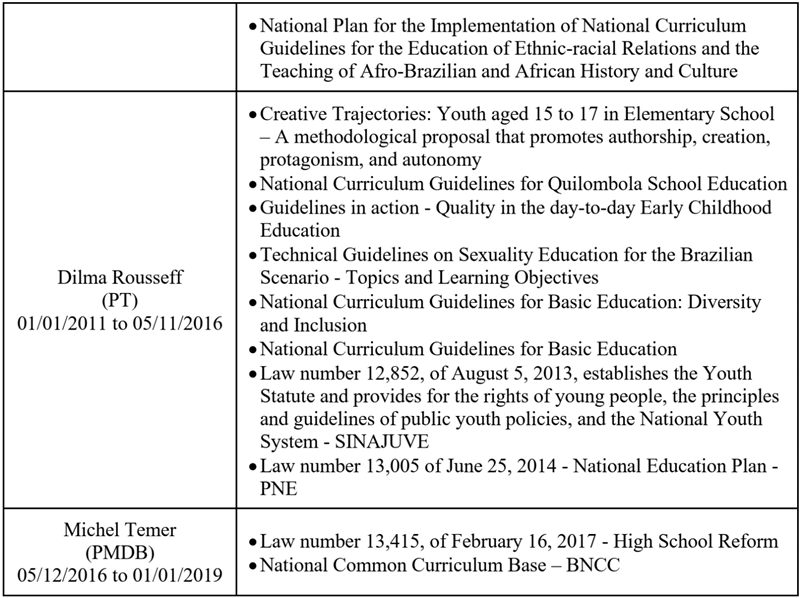

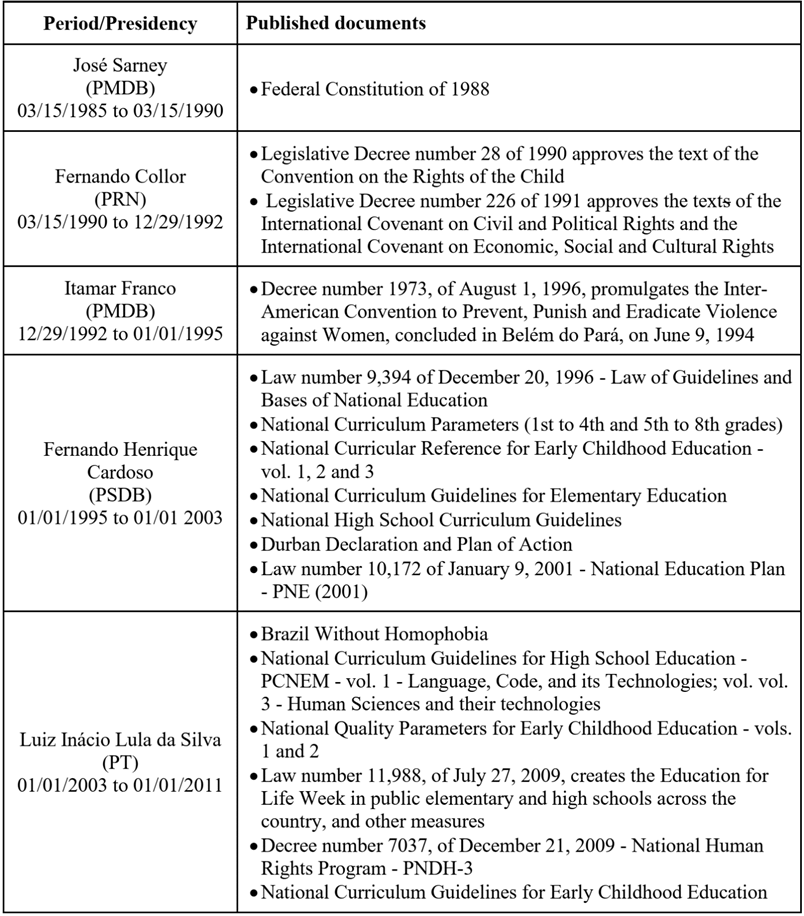

To organize the data produced, we created a model table with two columns. In the first, we indicate the period and who held the Presidency within that time frame and, in the second, the documents found.

We understand that this framework, in addition to being necessary for the organization and analysis of data, can also present, in an explicit and simplified way, the range of documents and regulations that address, in some way, the need for institutional actions of Sexuality Education aimed to re-signifying the way we relate to gender and sexuality issues, among others, in our construction as a whole.

For the analysis of the constituted data, we first turned to a deeper reading of the documents. Our reading was focused on verifying how questions related to Sexuality Education appeared, what approaches were given, and what type of language was used. Then, we tried to establish their connections and interweavings with the socio-political context of the country at the time they were published. With this, we seek to identify, more broadly, how official documents demonstrate the treatment given by the State to Sexuality Education over time.

DEVELOPMENT AND DISCUSSION

Throughout recent history, several official documents and legislation have dealt, directly or indirectly, with Sexuality Education in Brazil, sometimes to silence it, sometimes to promote and guide it, as shown in Box 1.

Source: the authors

Box 1: Laws and documents analyzed and political contexts on the date of their publication

Education Guidelines for themes of sexual diversity and gender have historically been marked by advances and setbacks (SILVA, BRANCALEONI, and OLIVEIRA, 2019). This alternation can be explained by the fact that sexuality has a central role in the construction of subjects and accompanies them throughout their lives, being deeply influenced by culture, customs, and disputes in different social and political contexts.

At the end of the 1980s and throughout the 1990s, for example, initiatives of working Sexuality Education in schools proliferated (FIGUEIRÓ, 1998; SILVA, 2004; VIANNA and UNBEHAUM, 2004). Certainly, this ebullition was driven by the profound social and political changes that Brazil was going through: re-democratization, discussions about the new Federal Constitution, and concerns about the large increase of contamination by the HIVand early pregnancy.

The 1980s were marked by the process of the political reopening of the country after decades of military dictatorship. In 1985, Tancredo Neves is elected, however, he dies before taking office and vice-president José Sarney, who was still aligned with the political system inherited from the military dictatorship, comes to power. Despite this, the period is marked by great democratic advances.

According to Vianna and Unbehaum (2004), the 1980s and 1990s were a period of many efforts that sought changes in Brazilian education, perhaps encouraged by the spirit of discussions about the Federal Constitution of 1988 and, later, by its consolidation. The Federal Constitution of 1988 provides for numerous advances in terms of social rights, including the right to education. In addition, it defines important premises in its fundamental clauses present in Articles 3 and 5 by establishing, among the fundamental objectives of the country, the construction of a free, fair, and solidary society and the promotion of the well-being of all with no form of discrimination, also determining equality between men and women in rights and obligations.

The school is, without a doubt, a fundamental part of the construction of societies, since it shares the responsibility for the education of its citizens with the family. In this sense, we understand that the dispositions in the Magna Carta supports the insertion of Sexual Education in schools since they carry great responsibility for the comprehensive development of individuals and the debates provided by the practices of Sexuality Education could create paths for the promotion of a society that integrates subjects with diverse expressions and identities of gender and sexuality without subordinating them.

Certainly, the construction of a free, fair, and solidary society, the reduction of inequalities, and the promotion of the well-being of all necessarily permeate an education that promotes reflections on oneself and the other, on the body, pleasure, consent, and violence, in addition to the more obvious issues of gender, sexuality, and diversity.

Even so, several groups do not share this understanding (or deliberately choose to close their eyes) and consider that there is no Constitutional recommendation for the existence of type Sexuality Education in schools that goes beyond purely biological and health issues. In any case, in the decades following the promulgation of the Magna Carta, several norms and guidelines about Education were published, carrying with them more possibilities for the promotion of Sexuality Education.

In 1990, Sarney's successor to the presidency was Fernando Collor, initially with modest voting intentions, but who received the support of the largest right-wing parties. Internationally, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, so-called democratic regimes expand, as capitalism and globalization consolidate. Here, individual rights begin to gain more exposure and importance.

In this context, the intersections between gender, sexuality, and education gained a lot of visibility, which somehow reverberated on Education official documents (VIANNA and UNBEHAUM, 2004). As a reflection an important legal milestone is achieved. In January 1990, Legislative Decree n° 28/90 approves the text of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations, and, in November of the same year, the Convention is enacted in Brazil through Decree n.° 99,710/90. The text, which determines that the States Parties recognize children's rights and provide means for them to be respected, covers Education in its articles 28 and 29. The article 29 specifically states

1. The States Parties recognize that the education of the child should be oriented to:

a) developing the child's personality, skills, and mental and physical capacity to their fullest potential;

b) imbueing the child with respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, as well as for the principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations; […]

d) preparing the child to assume a responsible life in a free society, in a spirit of understanding, peace, tolerance, gender equality, and friendship among all peoples, ethnic, national, and religious groups, and people of indigenous origin (BRASIL,1990b, n.p.).

The document, as well as the Federal Constitution (BRASIL, 1988), is permeated by values that emerged at the time: respect for human rights and individual freedoms, promotion of tolerance, and reduction of inequalities. As for Sexuality Education, it is our understanding that it is part of this social construction, and the insertion of its practices in schools is no only recommended, but necessary. However, despite the spirit of the times, Sexuality Education policies were never established, but, instead, as Figueiró (1998) points out, isolated, dispersed, and few perennial initiatives.

In 1992, Collor is impeached, and Itamar Franco assumes presidency. The period is marked by a great neoliberal advance, not only in Brazil. International agencies such as the IMF (International Monetary Fund) and the World Bank increasingly influence the political issues of indebted countries. According to Padilha (2016), the Itamar Franco government sought to prioritize Education on the State agenda, in dialogue with various educational sectors. But his short tenure, as well as international pressure, meant that effective policies were scarce.

The period was also marked by concerns about a large number of infections by HIV, making disease prevention the subject of several educational projects. In 1993, according to Silva (2004), the then-called Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC- Ministério da Educação e Cultura) created the National Council for Special Projects (CONAPES- Conselho Nacional de Projetos Especiais) which “provided for the standardization of Sexuality Education in the public education system” (SILVA, 2004, p. 26). However, this standardization did not happen and this attention to Sexuality Education was only motivated by the punctual and specific demand of what was called “combating AIDS”, not only lacking comprehensive national projects but also regarding Sexuality Education as a mere matter of biological health, in contrast to the recognition of its importance for the comprehensive development of children and young people and the construction of a fairer and less unequal society.

In 1995, Fernando Henrique Cardoso became president driven by the success of Plano Real. According to Del Priore and Venancio (2010), his term was marked by an even more neoliberal agenda, raising flags such as administrative efficiency and state reform. During his mandate, between 1995 and 2002, several official Education documents were published, of which the most important was the new Law of Guidelines and Bases of National Education (LDB), in December 1996.

This publication took place in the context of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), held in Egypt, and the Fourth World Conference on Women, in Beijing. (FURLANETTO et al., 2018). These conferences had a very strong focus on equity guidelines and the elimination of inequalities and prejudices, as well as the promotion of well-being and a culture of peace, which were incorporated into art. 3rd of the LDB

art. 3rd Teaching will be held based on the following principles:

I - equal conditions of access and permanence in school;

II - freedom to learn, teach, research and disseminate culture, thought, art and knowledge;

III - pluralism of ideas and pedagogical conceptions;

IV - respect for freedom and appreciation for tolerance; (BRASIL, 1996)

The LDB had an eight-year processing period in the National Congress. However, during this period, the Ministry of Education of the Fernando Henrique Cardoso government coordinated the preparation of an alternative proposal to the document that was being crafted. Presented by then-Senator Darcy Ribeiro, the new version ended up winning the Senate's preference for accommodating agendas that were aligned with the government's interests (VIANNA; UNBEHAUM, 2004).

Thus, the education reforms that took place in the 1990s were marked by a government with neoliberal characteristics, whose proposal was to accommodate the needs of the economy into the educational system. In this way, the LDB brings with it a great dichotomy: it shows the great achievements of education professionals and mobilized movements in the process of its construction, but, at the same time, it presents aspects that are more adherent to the neoliberal agenda adopted by the Federal Government at the time (VIANNA; UNBEHAUM; 2004).

This neoliberal agenda, which had the goal of strengthening the market, had to adapt to social changes, co-opting some agendas of minority groups and promoting individualism. Thus, the idea of individual freedom above the collective wellness began to spread, weakening, at the same time, the power of the State to carry out social policies aimed at the population. In this way, the discourse of diversity proliferates and one begins to see, in Education documents, a greater accommodation of issues related to gender, race, and sexuality.

This support for a more comprehensive Sexuality Education, which deals with broader issues than biological ones, appears very prominently in the National Curricular Parameters (PCN- Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais). The PCN is an orientation document for guiding the work of education professionals. Published for the initial years of Elementary School (1st to 4th grades) in 1997 and, in the following year, for the final years (5th to 8th grades), both documents present, as a transversal theme, a volume that deals with Sexual Orientation, which is what we call Sexuality Education was referred to at the time.

The PCN is an innovative document about Sexuality Education because, even though there are some criticisms to be made regarding their content, they bring forward, to some extent, Sexuality Education beyond health and hygiene issues. These documents define sexuality as “something inherent, which manifests from the moment of birth until death, in different ways at each stage of development.”(BRASIL, 1997, p. 81) and

a basic need and an aspect of being human that cannot be separated from other aspects of life [...] the energy that motivates finding love, contact, and intimacy [...] influences thoughts, feelings, actions, and interactions and both physical and mental health (BRASIL, 1998a, p. 295).

The PCN for both age groups propose working with the content blocks “Body: matrix of sexuality”, “Gender relations” and “Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Diseases/AIDS”, but they identify different specific contents for the two age groups.

Other documents from the period that refer to Sexuality Education, either directly or indirectly, were the National Curricular Reference for Early Childhood Education - vol. 1, 2, and 3, the National Curriculum Guidelines for Elementary Education, and the National Curriculum Guidelines for Secondary Education, all published in 1998. Moreover, in 2001, the Durban Declaration and Action Plan and the National Education Plan - PNE (Plano Nacional de Educação) were also published.

The National Curriculum Reference for Early Childhood Education (BRASIL, 1998b) is part of a group of documents that deal with the National Curricular Parameters and, in addition to working as a guide for teachers of Basic Education, it also points out quality goals for the educational process. This document refers to the work carried out in kindergartens and preschools, that is, those aimed at children aged between zero and six (since the nine-year Elementary School had not yet been implemented). The document is divided into three volumes, which address several axes: Personal and Social Education, Identity and Autonomy and Movement, Music, Visual Arts, Oral, and Written Language, Nature and Society and Mathematics.

The first volume states that the role of Early Childhood Education is to provide learning situations that articulate students' previous knowledge, as well as their social, emotional, and cognitive capacities to the different fields of human knowledge. For this, teachers should consider, among others, interactions between children, so that they develop the ability to relate to one another, as well as individuality and diversity, considering the singularities of each person and learning to respect and value them.

The second volume approaches, as one of its several topics, the issue of school as a place for children to be inserted into the ethical and moral relations of society. In this way, it is a determining space for how children will create mechanisms to deal with diversity and difference. A school that treats diversity in a prejudiced way will produce more prejudices in its students.

The document raises the question of the construction of identity and autonomy, which depends on several elements, among which is the expression of sexuality. It explains its manifestations and contexts, differentiating them for children between zero and three and four and six years old. Thus, it is clear that sexuality is considered an important aspect of the development of children. In this way, the document provides mechanisms for and encourages work with Sexuality Education as soon as in preschools. Even the question of gender identity, so often used as a manipulation agenda by conservative right-wing politicians, appears in this document published during the FHC government, as already noted, notably aligned to the right and which promoted a great expansion of neoliberalism.

Regarding gender identity, the basic attitude is to transmit, through actions and referrals, values of equality and respect between people of different sexes and to allow the child to play with the possibilities related to both the role of men and women. This requires constant attention by the teacher, so that stereotyped patterns regarding the roles of men and women are not reproduced in relationships with children, such as that women are responsible for taking care of the house and children and that it is up to the man to support the family and make decisions, or that a man does not cry and that a woman does not fight (BRASIL, 1998b, p. 41-42).

The National Curriculum Guidelines for Elementary School (BRASIL, 1998c), also published in 1998, edify the principles, fundamentals, and procedures of Basic Education. In art. 3rd, the principles that should guide all actions are defined. Here, the document points out the integration of sexuality into the curriculum

IV - In all schools, students must be guaranteed equal access to a common base so that unity and pedagogical quality are legitimized within the national diversity. The national common base and its diversified part should be integrated around the curricular paradigm, which aims to establish the relationship between fundamental education and:

a) citizen life through the articulation of several of its aspects, such as:

1. health

2. sexuality[...]

V - [...] students, when learning the knowledge and values brough forward by the common national base and the diversified part, will also be constituting their identity as citizens capable of being protagonists of responsible, solidary, and autonomous actions towards themselves, their families and communities (BRASIL, 1998c).

Thus, the document explicitly provides the insertion of Sexuality Education in Elementary School classes and the recognition of its importance for the construction of students’ identity and their integral formation.

Also in 1998, the National Curriculum Guidelines for High School were published. Although the document does not explicitly contain the expression “sex education”, it presents, in several passages, subjects related to it. An example of this can be seen in art. 3, in which it is provided that administrative and pedagogical practice must be consistent with principles that cover, among others.

I - the Aesthetics of Sensitivity, which should replace the repetition and standardization, stimulating creativity, inventive spirit, curiosity for the unusual, and affectivity, as well as facilitating the constitution of identities capable of withstanding restlessness, living with uncertainty and the unpredictable, welcoming and living with diversity, valuing quality, delicacy, subtlety, playful and allegorical ways of getting to know the world and making leisure, sexuality, and imagination an exercise in responsible freedom (BRASIL, 1998d).

In 2001, a new National Education Plan for 2001-2010 was published under Law 10,172/2001. This document does not focus on school content or teaching and learning processes, therefore, it does not directly mention Sexuality Education, but does present a discourse in favor of diversity. The documents show alignment to an unprejudiced and pro-diversity education. For Early Childhood Education, the importance of respect for regional differences, values, and cultural expressions is underlined. Regarding the Elementary School, the document contains, among its goals, ensuring that teaching materials establish “the appropriate approach to gender and ethnicity issues and the elimination of discriminatory texts or those that reproduce stereotypes about the role of women, blacks and indigenous people” (BRASIL, 2001).

As for Higher Education, the document sets a goal for the inclusion of transversal matters in teacher training courses such as gender and Sexuality Education. However, the target, once again, is not accompanied by comprehensive policies that would make it attainable.

Then, in the 2002 elections, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was elected in the dispute against the government candidate José Serra. It was the first time that a candidate aligned to the left came to power since the 1964 Military Coup and, thus, his election aroused great apprehension in a portion of the population while generating expectations for another. According to Del Priore and Venancio (2010), Lula´s government initiated several social policies, but, on the other hand, it maintained the economic regime of the previous government and sought conciliation between the most conservative and the most progressive sectors, between social policies and those aimed at the capital (DEL PRIORE; VENANCIO, 2010).

In the field of Education, the promotion of access to and improvement of Education took place through large Federal programs such as the creation of FUNDEB (Fund for the Maintenance and Development of Basic Education- Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica), ProUni (University for All Program- Programa Universidade Para Todos) and Reuni (Support Program for Restructuring and Expansion Plans for Federal Universities- Programa de Apoio a Planos de Reestruturação e Expansão das Universidades Federais).

The theme of diversity remains on the agenda, now with more force. However, its scope is even broader, referring to poverty, gender, ethnicity, and sexuality, as well as issues related to the protection of the environment, all showing up in several Education documents published in the period (CARREIRA, 2015).

Specifically for Sexuality Education, several documents that support it have been published. In 2004, the Ministry of Health, in partnership with the CNCD/LGBT (National Council for Combating Discrimination and Promoting the Rights of Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Transvestites and Transsexuals- Conselho Nacional de Combate à Discriminação e Promoção dos Direitos de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis e Transexuais) of the Ministry of Human Rights, published the Brazil Without Homophobia Program - Combating Violence and Discrimination against GLTB and Promoting Homosexual Citizenship as one of the fundamental bases for strengthening the exercise of citizenship in Brazil.

The document on Education is based on research carried out by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) which highlights the high rates of homophobia within the school, coming not only from male and female students but also teachers and fathers, mothers and guardians. It proposes an action plan to promote “values of respect for peace and non-discrimination based on sexual orientation” at school (BRASIL, 2004).

V - Right to Education: promoting values of respect for peace and non-discrimination based on sexual orientation

To elaborate guidelines for Education Systems in the implementation of actions that demonstrate respect for citizens and non-discrimination based on sexual orientation.

To foster and support an initial and continuing training course for teachers in the area of sexuality;

To form multidisciplinary teams to evaluate textbooks and eliminate discriminatory aspects based on sexual orientation and overcome homophobia;

To stimulate the production of educational materials (films, videos, and publications) on sexual orientation and overcoming homophobia;

To support and disseminate the production of specific materials for teacher training;

To disseminate scientific information on human sexuality;

To stimulate research and the dissemination of knowledge that contributes to the fight against GLTB violence and discrimination.

To create the Subcommittee on Education in Human Rights in the Ministry of Education, with the participation of the homosexual movement, to follow up and evaluate the established guidelines. […]

IX - Youth Policy

To support the carrying out of studies and research in the area of the rights and socioeconomic situation of GLTB adolescents, in partnership with international cooperation agencies and organized civil society.

To support the implementation of projects to prevent discrimination and homophobia in schools, in partnership with international cooperation agencies and organized civil society (BRASIL, 2004a, p.22-23).

As a consequence of Brazil without Homophobia, the School without Homophobia project was born. It aimed to help the school address sexuality and gender issues in a non-discriminatory manner. For this, a project with the goal of preparing instructional materials the school management and teaching staff was started, but later, after a sudden change in the country's political environment, the project was shelved and the materials produced were collected from schools (RODRIGUES; SILVA, 2020).

In 2006, the National Curriculum Guidelines for Secondary Education (PCNEM- Orientações Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio) - vols. 1, 2 and 3 and the National Quality Parameters for Early Childhood Education - vols. 1 and 2 were published.

In the PCNEM, whose purpose is to contribute to the dialogue about the teaching practice between high school teachers and the school, Sexuality Education appears in volumes 1 - Language, Code, and its Technologies and 2 - Natural Sciences, Mathematics, and its Technologies.

Volume 1 proposes reflections on society to broaden the worldview of students and the development of their sense of citizenship. For this, the document states that standard models of men and women and their differences for the people around them should be discussed, in addition to promoting critical literacy, with reflection on racial, sexual, and gender differences in the context of social relations.

Among the proposed themes, a huge range is related to the practice of Sexuality Education, among which “Youth identity”, “Gender and sexuality”, “Body performance and youth identities”, “Myths and truths about male and female bodies in today's society", "The body in the world of symbols and as a production of culture", "Body practices and public spaces", "Body practices and public events", "The body in the world of aesthetic production", "Body practices and community organization” and “Cultural construction of ideas of beauty and health”.

Volume 2 - Natural Sciences, Mathematics, and its Technologies - establishes that Sexuality Education is inserted within Biology classes, stating that it should, as a priority, develop subjects related to health, the human body, adolescence, and sexuality.

In addition, in volume 3 - Human Sciences and their Technologies - in History classes, PCNEM encourages the development of projects that include affirmative action policies of social inclusion, such as those of ethnic, religious, and sexual diversity, in addition to developing skills that allow students to

Perceive and respect ethnic, sexual, religious, generational, and class diversity as sometimes conflicting cultural manifestations. [...]

Practice respect for cultural, ethnic, gender, religious, and political differences. [...]

Be indignant at injustices and

Build personal and social identity in the historical dimension out of the recognition of the role of the individual in historical processes simultaneously as their subject and as their product. (BRASIL, 2006a, p. 83)

The discipline of Sociology must in turn include the “racial issue, ethnocentrism, prejudice, violence, sexuality, gender, environment, citizenship, human rights, religion and religiosity, social movements, mass media, (sic), etc." (BRASIL, 2006a) Thus, it is clear that Sexuality Education appears nominally in the document and also that it is supposed to be worked on in a transversal way since it is expected that it be present in different disciplines, from different areas of knowledge.

The National Quality Parameters for Early Childhood Education define as an objective the establishment of reference standards for the organization and operation of early childhood education institutions, which include children from zero to five years old (BRASIL, 2006b). The document establishes that children are citizens of rights, as established in the Statute of Children and Adolescents and, therefore, education must aim at their comprehensive development, valuing their well-being and developing attitudes of respect for diversity.

Furthermore, as for the babies, the document encourages the school to develop their curiosity and ability to express themselves through different languages, including the knowledge of their bodies, and activities that consist, themselves, of practices of Sexuality Education. In addition, the National Quality Standards for Early Childhood Education call upon schools to value cooperation, tolerance, and respect for diversity, and to promote non-discrimination in the school environment. Thus, although sometimes there is no nominal mention, all these documents show a strong presence of Sexuality Education, since the issues covered by it have a central place in them.

Later, in 2009, Law number 11,988, of July 27, 2009, was published, which created the Education for Life Week in public primary and secondary schools throughout the country, and gave other provisions. The law is quite short and generic, with only five articles. Even so, it makes clear the importance of Sexuality Education in schools. In its art. 2nd, it provides that the week should have classes and activities on important themes that are not included in the curricula such as sexuality and the prevention of transmissible diseases.

In the same year, the National Human Rights Program (PNDH-3- Programa Nacional de Direitos Humanos) is approved, which describes its implementation according to some guiding principles. Additionally, the document presents some guidelines for each axis, their specific programmatic actions, and the government sectors responsible for implementing them. As it could not be different, when it comes to the subject of Human Rights, several of these axes, in some way, are related to Education.

The program's Guiding Axis “V” deals with Education in Human Rights and proposes, among its programmatic actions, the adequacy of the school curriculum with the inclusion of contents that value, among others, the theme of diversity. In addition, the Program also provides for the improvement of the health program for adolescents, specifically in gender health, sexual and reproductive education, and mental health. For this, it highlights the importance of creating technical and educational materials on these topics. (BRASIL, 2009).

In several other passages, the document demonstrates a great concern with Basic Education in Human Rights and with the development of subjects that reflect and combine attitudes of respect for diversity, non-violence, and the culture of peace, themes that are also related to Sexuality Education.

In addition to this document, the government also presents the National Plan for the Implementation of the National Curriculum Guidelines for the Education of Ethnic-Racial Relations and for the Teaching of Afro-Brazilian and African History and Culture, which seeks to

[...] develop and implement educational inclusion policies, in articulation with the education systems, considering the specificities of Brazilian inequalities and ensuring respect and appreciation of the multiple social contours, evidenced by ethnic-racial, cultural, of gender, social, environmental and regional diversity of the national territory (BRASIL, 2009c, p. 10)

An important fact to be observed is that over time, Sexuality Education begins to become increasingly diluted within the discourse of diversity and increasingly depending on the interpretation given to the text. This is clear in the documents published in the following government of Dilma Rousseff.

On January 1, 2011, Dilma Rousseff's mandate begins with a speech of continuity to the previous government, which was marked by a period of a booming economy and a great rise of social policies to combat inequalities as well as important educational policies. However, the new social context was different from her predecessor. The speeches and political strength of the conservative sectors begin to rise. A few years later, now in her second term, jokes about Dilma's sexuality spread. Violence is wide open in stickers stamped on cars that show a montage of her face next to the body of a woman with legs apart, glued to the place where the fuel nozzle is introduced.

The fact that these events took place precisely at the moment when the first female president is elected, cannot be ignored and demonstrate how fragile the social advances achieved by minorities are, since, in the face of any instability, they retreat. The emancipation of women and the reduction of gender and sexuality inequalities are always in check and, to a large extent, this is due to a complete lack of Sexuality Education in the population.

In addition to the sexist violence suffered by Dilma, the government suffers social pressure during an economic slowdown, which ended up leading to a growing rejection of the president. The year 2013 was adopted as the starting point of a long period of social and political instability in Brazil, although this process had begun some time before. The so-called “Journeys of June” were large popular demonstrations that were initially opposed to the increase in public transportation fares, but which ended up, as they gained popular support, encompassing a series of demands from various civil society movements, many of which were conflicting.

Although the moment was called “Journeys of June” its effects were not restricted to that month, on the contrary, they were central to the political processes that followed and gave great visibility to conservative groups that, until then, seemed to lose space in society, especially regarding public institutions (SARMENTO, REIS, and MENDONÇA, 2017). Such groups, in addition to the empty agenda of fighting corruption, as if it were something isolated and recent, which could be overcome with a simple change of government, also started to target Education and its professionals. The pseudo-movement “School with no Party” is born, making noise for some time with the agenda of combating the fallacies of gender ideology and Marxist indoctrination in schools.

Nevertheless, it was possible to verify that diversity issues were still present in some Education documents published at the time. This is the case of the National Curriculum Guidelines for Quilombola School Education in Basic Education (2012), which already contemplate its purpose since they seek to integrate children and young people from traditional communities into the Education system, guaranteeing respect for their identity. Gender and sexuality issues also appear explicitly in the document, in the sense of respect for sexual diversity and overcoming LGBTphobic and sexist practices in schools.

In 2013, important documents are published such as the National Curriculum Guidelines for Basic Education, which compile, in a single document, the new guidelines that establish the common national basis responsible for guiding the organization, articulation, development, and evaluation of the pedagogical proposals of all Brazilian education systems.

In addition, another compilation is published, a compendium of guidelines that deal with specific issues considered as “diversity”, such as Young Adult Education, Indigenous School Education, and Quilombola Education, among others. The publication was entitled National Curriculum Guidelines for Basic Education: Diversity and Inclusion.

Through this compilation, the emptying of the Sexuality Education agenda becomes clear. In the guidelines, themes related to gender, discrimination, and identity are mentioned several times; however, in the 482 pages, the term sexuality appears only three times, and the expression Sexuality Education is not mentioned.

The same occurs with the most recent National Education Plan, which, in its art. 2nd states that “The PNE guidelines are: [...] X - promotion of the principles of respect for human rights, diversity and socio-environmental sustainability” (BRASIL, 2014). In Early Childhood Education, this concern remains, timidly, in the Guidelines in Action - Quality in the day-to-day of Early Childhood Education, published in 2015 to act as a support guide for the implementation of the National Curriculum Guidelines for Early Childhood Education. The document encourages teachers to use recreational activities and toys that break with relations of ethnic-racial and gender domination, in addition to working with children on their relationship with their bodies and with free movement.

Some deal with Sexuality Education in a slightly more explicit way, but are still insufficient. This is the case of Law nº 12.852/13, which establishes the Youth Statute and the National Youth System - SINAJUVE (Sistema Nacional de Juventude), when it provides, as a measure to ensure youth the right to diversity, the inclusion of themes related to sexuality in the curriculum.

Finally, and following the same line, we find the document Creative Trajectories: Young people aged 15 to 17 in Elementary School - A methodological proposal that promotes authorship, creation, protagonism, and autonomy, from 2014. The document highlights, for teachers, the importance of a school practice that provides reflections on various aspects of young people's lives, such as generational problems, and the analysis of power in ethnic, gender, and class relations. In addition, the document calls on teachers to provide moments of reflection on identity, diversity, respect, doubts and anxieties, body and sexuality

An exception to this trend of dilution of Sexuality Education is the publication, in 2013, of the Technical Guidelines on Sexuality Education for the Brazilian Scenario - Topics and Learning Objectives (CAVASIN; GAVA; BAPTISTA, 2014). The document is aimed at educators and highlights the importance of Sexuality Education, detailing the reasons why it should be included in the school curricula of children from the age of five.

Since its introduction, the Guidelines provide explanations in plain language of what sexuality means and its occurrence throughout a person's lifetime, from birth to death. The document also calls attention to the importance of inserting a planned and systematized Sexuality Education within the school curricula in order to eradicate all forms of intolerance - sexual, of gender, ethnic-racial, religious, of age, and of social class.

For this, the document identifies six key concepts to be worked on with children and young people of all ages: Relationships; Values, attitudes, and skills; Culture, society, and human rights; Human development; Sexual behavior; and Sexual and reproductive health. From there, some learning topics are proposed for each key concept, and, finally, different key ideas are to be worked with each age group.

For the teacher who wants to work with Sexuality Education, the document is of great value and, when compared to other documents from the period already mentioned here, it seems to be ahead of its time. The fact is that the document was published by a supranational organization, UNESCO, and did not depend on the approval of the country's governmental spheres, nor does it appear on the website of the Ministry of Education.

It is noticeable, then, that the Education documents published in this period suffered the weight of their political and social-ideological context. Those who substantiate the practice of Sexuality Education, to some extent, do so more subtly and subjectively than in the two previous governments as it appears diluted within the discourse of diversity, a word that became emptied once it started to be used as a way of non-commitment to specific agendas.

A clear example of this was the government's decision, in 2011, to suspend the distribution of the School without Homophobia Project booklet and educational toolkit to schools, which had been developed for years within the scope of Brazil without Homophobia Program. The notebook was financed by the Ministry of Education and had the collaboration of several civil society organizations. Years later, the material was dubbed “gay kit” and ostensibly used to spread Fake News and promote conservative candidates in the 2018 elections.

Regrettably, this episode laid bare how easily Sexuality Education is dismissed in the face of pressure from more conservative sectors. Such was the discomfort that the National Council to Combat Discrimination, a collegiate body of the National Secretariat for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights, approved, on June 9, 2011, its motion n° 03, reiterating its support for the project.

However, history has shown that the government's concessions and accommodations were not enough to keep the president in office. The power-holding elite no longer accepted the small social advances achieved in the Workers' Party governments, even though they did not stop working for their interests. Thus, on May 12, 2016, Dilma Rousseff suffers a coup and leaves the presidency.

Vice-president Michel Temer takes over, initially as interim and later, on August 31, 2016, when the coup is confirmed, as President of the Republic. In the period, the conservative, fundamentalist, and bourgeois uprisings continue to expand, as well as disinformation and so-called Fake News.

Immediately after his confirmation as president, Temer initiates a series of counter-reforms. Perhaps the most publicized was Constitutional Amendment n° 95, also known as the End of the World PEC, which limited government spending for twenty years, preventing public investment, including in the areas of Health and Education.

Another immediate measure by the Temer government was Provisional Measure number 746, of September 22, 2016, converted into Law number 13,145 in February 2017. This is what was called High School Reform. The proposal, sent to the National Congress in an authoritarian manner, did not consider the discussions that had been taking place at the National Education Conferences (CONAE- Conferências Nacional de Educação) and was received with indignation by education professionals and scholars.

The Reform, under the pretext of providing free choice to students and facilitating their access to the labor market through professional education, in practice, contributed to a fragmented formation, which aimed at subordinating education to capital and accentuated inequalities by providing academic training to an elite and technical training to the poorest sections of the population. (COSTA; COUTINHO, 2017)

In this context, discussions about the Common National Curricular Base take place, fervently defended by the media and by the Movement for the Common National Base, formed mostly by foundations linked to private companies, such as the Lemann, Roberto Marinho, and Maria Cecilia Souto Vidigal; the Ayrton Senna, Unibanco, Natura and Inspirare institutes, among many others. In addition, the BNCC has also been defended by a large number of former Ministers of Education. (CÁSSIO, 2019)

On the other hand, as with the High School Reform, education professionals and scholars claim that the BNCC is detached from reality, as it seeks to obtain better results in international indicators of countries whose reality has nothing to do with the Brazilian. Thus, the BNCC appears as the easy solution to a complex problem in Education, which, as advocated by the PNE, requires investments in infrastructure, and valorization of the teaching career, with better salaries and better training, among others.

And where does Sexuality Education fit into this context? The answer is simple: it doesn't. Approved at this moment of the uprising of conservatism in Brazil, the BNCC caused heated discussions, being the scene of a dispute between conservative and progressive segments of society, especially when it comes to the presence of the terms “gender” and “sexual orientation” (SILVA, BRANCALEONI, and OLIVEIRA, 2019). Conservative pressures were effective in regard to the document, since the controversial terms were completely suppressed. There are only two points in the 595-page document that make room for Sexuality Education activities. The first of them, from a predominantly biological perspective, when it comes to the skills to be worked on in Science classes in the eighth year of Elementary School is

To compare the mode of action and effectiveness of different contraceptive methods and justify the need to share responsibility for choosing and using the most appropriate method for preventing early and unwanted pregnancies and Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs).

To select arguments that show the multiple dimensions of human sexuality (biological, sociocultural, effective, and ethical).” (BRASIL, 2017, p. 349)

The second, in the subject of History, in the ninth year, in which students are expected to develop the ability to

To discuss and analyze the causes of violence against marginalized populations (black people, indigenous people, women, homosexuals, peasants, poor people, etc.) raising awareness and building a culture of peace, empathy, and respect for people (BRASIL, 2017, p. 431).

Considering this context, one could wonder if the maintenance of this session of the document was not just a slip on the conservative groups’ part. The approval of the BNCC lays bare the path taken by Brazilian society in the last decade, and consequently, the way it sees Education. As a result, Sexuality Education, and all its work in diversity and gender issues, suffered a process of being silenced and combated, and even of violence. Teachers who seek to practice it have to fight against very powerful forces and discourses, which makes their work a place of fear and insecurity. However, despite the context of dereliction, the research demonstrated that there is space, ways, and legal and official support for the insertion of Sexuality Education, as well as discussions on gender and sexuality, in the school. In addition, the history of advances and setbacks on the theme can, in some way, serve as a hope that a new, better moment is on the way to being built.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Even though the moment is of great political pressure for Sexuality Education and any issues related to gender and sexuality to be silenced in Brazilian schools, there is a whole web of normative documents, international agreements, manuals, laws, and decrees that support and legitimize working this theme within schools. Also, the research has shown that the educational practice carried out without the insertion of a systematized Sexuality Education goes against the grain of the national legislation.

Several Education official documents, as well as broader laws and drecrees determine that children, adolescents and youth should be exposed to the necessary learnings so that they can fully exercise their citizenship, their sexuality, their social insertion, their capacity for dialogue, and their respect for freedom and diversity.

A school without the presence of Sexuality Education perpetuates violence and inequalities, which goes against what the documents recommend. In a country where sex, gender, sexuality, and violence are so intertwined, teachers and schools have the responsibility to promote it from a comprehensive perspective.

This perspective is the one that builds, together with students, reflections on themselves and the other, on the body, pleasure, health, and diversity in order to fight inequalities and violence based on various social markers, such as gender and individual expressions of identity and sexuality.

Thus, the research demonstrated that presence of Sexuality Education in schools is supported by to the documents presented here. Such documents are laws, decrees, and international agreements that not only support this work, but also encourage it and, sometimes, determine it. Considering the great importance of the school in the education of individuals, by exempting itself from this discussion, it is not enforcing rights guaranteed by the force of law to Brazilian citizens.

However, although Sexuality Education is provided for in the Law, there are several gaps and discontinuities in the history of public policies that backup the theme. What one sees are punctual, spaced, and non-perennial initiatives and projects for the effective promotion of Sexuality Education, which makes the consolidation of this work difficult.

In addition, universities and colleges need to have greater emphasis in training teachers for carrying out practices of Sexuality Education so that they can perform this work. It is necessary and pressing to prioritize the construction of this knowledge in the curricula of undergraduate courses so that there are significant advances. It is also unfair to demand that the movement to carry out works with Sexuality Education be solely and exclusively under the responsibility of teachers.

However, although the documents show that Sexuality Education, for a long time, has been considered relevant for the education of children, adolescents, and young people, in Brazil there has never been a structured policy of comprehensive and perennial Sexuality Education, a strong guideline to insert it, in fact, in school.

There are gaps, discontinuities, and great fragility in the face of changes in government and the social contexts that Brazilian society is going through. We believe that this is because Sexuality Education has never really been prioritized, both in Education programs and in teacher training and curricula. Research has shown that it is at times dismissed in the face of political pressures, at times used as a smokescreen to hide other political and economic issues, and, recently, it has even been serving as an electoral platform for conservative groups seeking to arouse uninformed outrage in some parts of the population.

This fragility is a strong sign that we have never had an effective and perennial school Sexuality Education policy in Brazil other than that of sanitation, silencing, and fear; and it demonstrates how pressing public policies for making it possible. Otherwise, there are few chances that the cycle of gender and sexuality violence presented here will stop perpetuating.

REFERENCES

BRASIL. Constituição (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília, 1988. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto Legislativo nº 28, de 14 de novembro de 1990. Aprova o texto da Convenção sobre os Direitos da Criança. Brasília, 1990a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto. n° 99.710, de 21 de novembro de 1990. Promulga a Convenção sobre os Direitos da Criança. Brasília, 1990b. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto Legislativo nº 226, de 12 de dezembro 1991. Aprova os textos do Pacto Internacional sobre Direitos Civis e Políticos e do Pacto Internacional sobre Direitos Econômicos, Sociais e Culturais. Brasília, 1991. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 1.973, de 1º de agosto de 1996. Promulga a Convenção Interamericana para Prevenir, Punir e Erradicar a Violência contra a Mulher, concluída em Belém do Pará, em 9 de junho de 1994. Brasília, 1996a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394 de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Brasília, 1996b. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação e do Desporto. Secretaria de Educação Básica. Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais (1ª a 4ª série). Brasília, 1997. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação e do Desporto. Secretaria de Educação Básica. Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais (5ª a 8ª série). Brasília, 1998a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação e do Desporto. Secretaria de Educação Básica. Referencial curricular nacional para a educação infantil. Brasília, 1998b. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Parecer CNE/CEB nº 2, de 7 de abril de 1998. Trata das Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Fundamental. Brasília: 1998c. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Parecer CNE/CEB nº 15, de 1º de junho de 1998. Trata das Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio. Brasília: 1998d. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 10.172, de 9 de janeiro de 2001. Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação e dá outras providências. Brasília, 2001. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Conselho Nacional de Combate à Discriminação. Brasil sem homofobia: programa de combate à violência e à discriminação contra GLBT e promoção da cidadania homossexual. Brasília, 2004a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Básica. Orientações Curriculares para o Ensino Médio (vols. 1, 2 e 3). Brasília, 2006a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Básica Parâmetros Nacionais de Qualidade para a Educação Infantil (vols. 1 e 2). Brasília, 2006b. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Secretaria Especial dos Direitos Humanos. Programa Nacional de Direitos Humanos (PNDH-3). Brasília, 2009a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Diretrizes curriculares nacionais para a educação infantil. Brasília, 2009b. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização e Diversidade. Secretaria de Políticas de Promoção da Igualdade Racial. Plano Nacional de Implementação das Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação das Relações Étnico-raciais e para o Ensino de História e Cultura Afro-brasileira e Africana. Brasília, 2009c. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 11.988, de 27 de julho de 2009. Cria a Semana de Educação para a Vida, nas escolas públicas de ensino fundamental e médio de todo o País, e dá outras providências. Brasília, 2009d. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Câmara de Educacção Básica. Resolução nº 8, de 20 de novembro de 2012. Define Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a. Educação Escolar Quilombola na Educação Básica. Brasília, 2012. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretária de Educação Básica. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais Gerais para a Educação Básica. Brasília, 2013a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 12.852, de 5 de agosto de 2013. Institui o Estatuto da Juventude e dispõe sobre os direitos dos jovens, os princípios e diretrizes das políticas públicas de juventude e o Sistema Nacional de Juventude - SINAJUVE. Brasília, 2013b. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização, Diversidade e Inclusão. Diretoria de Políticas de Educação em Direitos Humanos e Cidadania. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação Básica: diversidade e inclusão. Brasília, 2013c. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.005 de 25 de junho de 2014. Institui o Plano Nacional de Educação - PNE. Brasília, 2014. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Trajetórias Criativas: jovens de 15 a 17 anos no ensino fundamental: uma propostametodológica que promove autoria, criação, protagonismo e autoria. Caderno 1. Brasília, 2014b. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.415 de 16 de fevereiro de 2017. Altera as Leis nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, e 11.494, de 20 de junho 2007, que regulamenta o Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica e de Valorização dos Profissionais da Educação, a Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho - CLT, aprovada pelo Decreto-Lei nº 5.452, de 1º de maio de 1943, e o Decreto-Lei nº 236, de 28 de fevereiro de 1967; revoga a Lei nº 11.161, de 5 de agosto de 2005; e institui a Política de Fomento à Implementação de Escolas de Ensino Médio em Tempo Integral. Brasília, 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Resolução n.º 3, de 21 de novembro de 2018. Atualiza as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio. Brasília, 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Brasília, 2018b. [ Links ]

BRUESS, Clint; GREENBERG, Jerrold. Sexuality Education. Theory and Practice. 5ed. Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2009. [ Links ]

CADERNO escola sem homofobia. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2009. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://nova-escola-producao.s3.amazonaws.com/bGjtqbyAxV88KSj5FGExAhHNjzPvYs2V8ZuQd3TMGj2hHeySJ6cuAr5ggvfw/escola-sem-homofobia-mec.pdf >. Acesso em: 13/08/2021. [ Links ]

CARREIRA, Denise. Igualdade e diferença nas políticas educacionais: a agenda das diversidades nos governos Lula e Dilma. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 2015. [ Links ]

CÁSSIO, Fernando. Existe vida fora da BNCC? In: CÁSSIO, Fernado; CATELLI-JR, Roberto (orgs.). Educação é a Base? 23 educadores discutem a BNCC. São Paulo: Ação Educativa, 2019, p. 13-39. [ Links ]

CASTRO, Jane Margareth; REGATTIERI, Marilza (orgs.). Interação escola-família: subsídios para práticas escolares. Brasília: UNESCO, MEC, 2009. [ Links ]

CAVASIN, Sylvia; GAVA, Thais; e BAPTISTA, Elizabete Regina. Orientações técnicas de educação em sexualidade para o cenário brasileiro: tópicos e objetivos de aprendizagem. Brasília: UNESCO, 2014. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227762 >. Acesso em: 30/12/2021. [ Links ]

COSTA, Maria Adélia da; COUTINHO, Eduardo Henrique Lacerda. A formação de professores para a Educação Profissional e o Notório Saber: uma ponte para o passado. In: IVColóquio Nacional e I Internacional A produção do conhecimento em Educação Profissional, 2017. Anais, Natal: IFRN, 2017. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://ead.ifrn.edu.br/coloquio/anais/2017/trabalhos/eixo3/E3A8.pdf >. Acesso em:15/10/2021. [ Links ]

DEL PRIORE, Mary; VENÂNCIO, Renato. Uma breve história do Brasil. São Paulo: Planeta, 2010. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO AVISA LÁ. Diretrizes em ação: qualidade no dia a dia da educação infantil. Ministério da Educação; Fundo das Nações Unidas para a Infância - UNICEF. São Paulo: Ed.Instituto Avisa Lá, 2015 [ Links ]

FIGUEIRÓ, Mary Neide Damico. Educação Sexual: problemas de conceituação e terminologias básicas adotadas na produção acadêmico-científica brasileira. Semina: Ciências Sociais e Humanas, v. 17, n. 3, p. 286-293, 1996. http://dx.doi.org/10.5433/1679-0383.1996v17n3p286 [ Links ]

FIGUERÓ, Mary Neide Damico. Revendo A História Da Educação Sexual No Brasil: Ponto De Partida Para Construção De Um Novo Rumo. Nuances: estudos sobre educação, v. 4, n. 4, p.123-133, 1998. https://doi.org/10.14572/nuances.v4i4.84 [ Links ]

FÓRUM ECONÔMICO MUNDIAL. Relatório de Riscos Globais. Relatório de percepção. 16ed, 2021. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.zurich.com.br/-/media/project/zwp/brazil/docs/noticias/sumario-executivo-relatorio-riscos-globais-2021.pdf\ >. Acesso em: 18/01/2022 [ Links ]

FURLANETTO, Milene Fontana et al. Educação sexual em escolas brasileiras: revisão sistemática da literatura. Cadernos de Pesquisa, v. 48, n. 168, p. 550-571, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1590/198053145084. [ Links ]

GÊNERO E NÚMERO. Mapa da Violência de Gênero. Séries históricas das duas maiores bases de dados sobre violência do país, 2017. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://mapadaviolenciadegenero.com.br/ >. Acesso em:15/01/2022. [ Links ]

GIL, Antônio Carlos. Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa. São Paulo: Atlas, 2002. [ Links ]

MIGUEL, Luiz Felipe. Da “doutrinação marxista” à "ideologia de gênero" - Escola Sem Partido e as leis da mordaça no parlamento brasileiro. Revista Direito e Praxis. v. 7, n. 3, p. 590-621, 2016. https://doi.org/10.12957/dep.2016.25163 [ Links ]

NAÇÕES UNIDAS. Declaração e Programa de Ação. In: IIIConferência Mundial de Combate ao Racismo, Discriminação Racial, Discriminação Racial, Xenofobia e Intolerância Correlata. Durban, 2001. [ Links ]

NETTO, Aristóteles Mesquita de Lima. Educação Sexual Brasil e Portugal em espaços escolares: aproximações a partir de documentos oficiais. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências Humanas) - Goiania: Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Goiás, 2016. [ Links ]

NUNES, César; SILVA, Edna. A educação sexual da criança: subsídios teóricos e propostas práticas para uma abordagem da sexualidade para além da transversalidade. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2006. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, José Marcelo Domingos de; MOTT, Luiz (orgs). Mortes violentas de LGBT+ no Brasil. Salvador: Editora Grupo Gay da Bahia, 2020. [ Links ]

PADILHA, Caio Augusto Toledo. A política educacional do governo Itamar Franco (1992-1995) e a questão da inclusão. Revista Espaço Acadêmico. V. 16, n. 180, p. 82-97, 2016. Disponível em: < Disponível em: https://www.periodicos.uem.br/ojs/index.php/EspacoAcademico/article/view/29541 > . Acesso em:22/01/2022. [ Links ]

PIMENTEL, Alessandra. O método da análise documental: seu uso numa pesquisa historiográfica. Cadernos de Pesquisa, n. 1, p. 179-195, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742001000300008 [ Links ]

RODRIGUES, José Rafael Barbosa; SILVA, Josenilda Maria Maués da. Democracia e diferença em tramas político-curriculares contemporâneas: o Escola Sem Homofobia em análise. Dossiê - Educação, democracia e diferença. Educar em Revista. v. 36, e75686, p. 1-22, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.75686 [ Links ]

SARMENTO, Rayza; REIS, Stephanie; MENDONCA, Ricardo Fabrino. As jornadas de junho e a questão de gênero: as idas e vindas das lutas por justiça. Revista Brasileira de Ciência Política, v. 22, p. 93-128, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-335220172203. [ Links ]

SILVA, Caio Samuel Franciscati da; BRANCALEONI, Ana Paula Leivar; OLIVEIRA, Rosemary Rodrigues de. Base Nacional Comum Curricular e diversidade sexual e de gênero: (des)caracterizações. RIAEE - Revista Ibero-Americana de Estudos em Educação v. 14, n. esp. 2, p. 1538-1555, 2019. E-ISSN: 1982-5587, http://dx.doi.org/10.21723/riaee.v14iesp.2.12051 [ Links ]

SILVA, Regina Célia Pinheiro. Pesquisas sobre formação de professores / educadores para abordagem da educação sexual na escola. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 2004. [ Links ]

STAKE. Robert E. Pesquisa Qualitativa - estudando como as coisas funcionam. Porto Alegre: Penso, 2011. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Orientações técnicas de educação em sexualidade para o cenário brasileiro: tópicos e objetivos de aprendizagem. Brasília: UNESCO, 2014. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000227762 >. Acesso em: 30/12/2021. [ Links ]