Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.39 Belo Horizonte 2023 Epub 15-Mar-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469839080

ARTICLE

DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES AS A PEDAGOGICAL RESOURCE FOR REMOTE TEACHING: IMPLICATIONS FOR CONTINUING EDUCATION AND TEACHING PRACTICES

1Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN). Caicó, Rio Grande do Norte (RN), Brazil.

2 Faculdade Venda Nova do Imigrante (FAVENI). Governador Valadares, Minas Gerais (MG), Brazil.

This study emerged from inquietudes about the impasses that go through the experience of Emergency Remote Education (ERE) during the COVID-19 pandemic unleashed in 2020. In this sense, this article reports on a research whose objective was to analyze the implications of the use of digital technologies in the continuing education process and in the practices of literacy teachers, during the Remote Teaching, in 2020, in the Francisco Francelino de Moura Municipal School. The study was developed through a literature review of the main concepts that underpin the literacy process: pedagogical mediation, teaching practice and ERE. In addition, the normative documents of this type of teaching, the National Common Curricular Base, among others, were verified. We also conducted a qualitative field research with two literacy teachers of 1st and 2nd year (Literacy Cycle). The data treatment procedure used was Content Analysis. It was found that the teachers developed new practices, especially with the use of digital technologies and, despite the difficulties encountered, they sought to know and appropriate these resources resulting in a reflective practice of constant research and improvement.

Keywords: Emergency Remote Teaching; literacy; lettering; continuing education

A presente pesquisa emerge de inquietações sobre os impasses que transpassam a experiência do Ensino Remoto Emergencial (ERE), durante a Pandemia da COVID-19 desencadeada em 2020. Neste sentido, este artigo relata acerca de uma pesquisa cujo objetivo foi analisar as implicações do uso das tecnologias digitais no processo de formação continuada e nas práticas dos professores alfabetizadores, durante o ensino remoto, em 2020, na Escola Municipal Francisco Francelino de Moura. O estudo desenvolveu-se mediante revisão bibliográfica dos principais conceitos que fundamentam o processo de alfabetização: mediação pedagógica, prática docente e ERE. Além disso, foram verificados os documentos normativos desse tipo de ensino, a Base Nacional Comum Curricular (BNCC), entre outros. Realizou-se ainda, uma pesquisa de campo de cunho qualitativo com duas professoras alfabetizadoras do 1º e 2º ano (Ciclo de Alfabetização). Utilizou-se como procedimento de tratamento dos dados a Análise de Conteúdo. Constatou-se que as professoras desenvolveram novas práticas, principalmente com o uso das tecnologias digitais e, apesar das dificuldades encontradas, buscaram conhecer e apropriarem-se desses recursos resultando em uma prática reflexiva de constante pesquisa e aperfeiçoamento.

Palavras-chave: Ensino Remoto Emergencial; alfabetização; letramento; formação continuada

La presente investigación emerge de inquietudes sobre los puntos muertos que traspasan la experiencia de la Enseñanza Remota de Emergencia (ERE) a lo largo de la Pandemia del COVID-19 desencadenada en 2020. En este sentido, este artículo relata una investigación cuyo objetivo fue analizar las implicaciones del uso de las tecnologías digitales en el proceso de formación continuada y en las prácticas de los profesores alfabetizadores a lo largo de la Enseñanza Remota en 2020 en la Escuela Municipal Francisco Francelino de Moura. El estudio se desarrolló a partir de una revisión bibliográfica de los principales conceptos que fundamentan el proceso de alfabetización como la mediación pedagógica, la práctica docente y la ERE. Además, hemos consultado los documentos normativos de la ERE, la Base Nacional Común Curricular (BNCC), entre otros. Se ha realizado todavía una investigación de campo de cuño cualitativo con dos profesoras alfabetizadoras del 1º y 2º año (Ciclo de Alfabetización). Se ha utilizado como procedimiento de tratamiento de los dados el Análisis de Contenidos. Se ha constatado que las profesoras desarrollaron nuevas prácticas, sobre todo, con el uso de las tecnologías digitales y, aunque se han encontrado dificultades, buscaron conocer y apropiarse de esos recursos, lo que resultó en una práctica reflexiva, de constante investigación y perfeccionamiento.

Palabras-clave: Enseñanza Remota de Emergencia; alfabetización; literacidad; formación continuada

INTRODUCTION

Amidst the pandemic scenario of 2020, people have had their lives abruptly changed in many aspects. Among them are professional, personal, social, and student life, and it is, therefore, necessary to take steps to distance oneself. As far as the educational context is concerned, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought great challenges. Unusually, remote activities were adopted as a teaching model, thus sharing the setbacks of this teaching alternative with the school community. As this was the alternative found to carry out classes and/or school activities in times of pandemic, it was noticed that the students in the early years of elementary school, especially the children who were in the literacy process, were in a complex adaptation situation, since they had recently left kindergarten. According to the Common National Curricular Base - BNCC (2017, p. 53). “The transition between these two stages of Basic Education requires much attention so that there is a balance between the changes introduced, ensuring integration and continuity of children’s learning processes”. In this case, it is particularly considered a scenario in which the knowledge of the specificities of the Alphabetic Writing System (AWS) is still something abstract for the student.

Therefore, we can consider that effective work with literacy depends on several aspects and demands, mainly the teacher’s professional qualification. For this, this professional needs to be prepared and know the necessary actions to develop a meaningful practice. Thus, the daily contact of the students with the teacher is relevant, considering that the teacher must seek methods that develop the skills and meet the needs of each child.

However, with the classes taking place remotely, this physical contact was lost, making the teacher’s work even more difficult. In addition, the educator did not have the opportunity to know the obstacles that each child faced at home to participate in the non-presence classes. Among them were the absence of family support, poor housing conditions, and lack of access to internet plans/electronic devices, among other difficulties. These and other specificities were present in the educational field, considering that we live in an entirely unequal and plural country.

These and many other questions raised the interest in carrying out the present investigation based on the following problem: What are the implications of the use of digital technologies in the continuing education process and the practices of literacy teachers during remote teaching in 2020, developed in the Francisco Francelino de Moura Municipal School?

The study was developed based on qualitative research guidelines because it is referenced in the Human and Social Sciences epistemology. According to Lüdke and André in educational research (2018, p. 5), “&$91;...] things happen in such an inextricable way that it is difficult to isolate the variables involved and, even more so, to clearly point out which ones are responsible for a certain effect”.

The locus of the research was the Municipal School Francisco Francelino de Moura, located in Patu (Rio Grande do Norte State). To this end, we conducted a literature review of the main concepts that underpin the literacy process: continuing education, teaching practice, ERE, use of digital technologies in teaching practices and literacy literacy, based on the works of Soares (2020), Mortatti (2004), Morais (2005), Ferreiro (2011), Oliveira et al. (2020), Kenski (2013), Conte (2022). We also studied the normative documents of the ERE, the Common National Curricular Base (BNCC), among others.

The research subjects were two literacy teachers from the Literacy Cycle. In order to guarantee the indispensability of ethics within the research and to protect the identity of the teachers, we used pseudonyms with names of precious stones, which are identified by Agata (1st Year) and Safira (2nd Year). The data collection instrument used was the semi-structured interview, which, according to Minayo (2002), is initially idealized and presumed. However, the researcher is not restricted to this, since during the dialog, transfigurations may occur and, consequently, the course will be changed. Thus, this procedure enables a systematization, although the also greater depth and reflection through the statements of the subjects, occurring a bond between researcher and researched.

As a procedure for data analysis, we adopted Content Analysis, which, according to Bardin (1997, p. 31) “&$91;...] is a set of techniques for communications analysis. This method allows the researcher a more complete, adaptable, and reflective look relevant to a comprehensive domain: communications. From this procedure, it was possible to build two categories of content and their respective subcategories: continuing education and the use of digital technologies.

The article initially presents a historical and legal reflection on literacy and how the COVID-19 Pandemic affected literacy practices. Next, it discusses the association of continuing education with digital technologies and their use as pedagogical resources in the literacy process. It then presents a brief reflection on literacy from a literacy perspective and the influence of technologies during remote teaching. It also reflects on the research data analysis regarding the implications of remote teaching on continuing education and teaching practices, according to the content categories constructed. Finally, we outline the final considerations with the synthesis of the results according to the objectives established for the research conducted.

LEGAL REFLECTIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Considering the principles and attributions that involve Basic Education, in Brazil, according to the National Curricular Guidelines for Basic Education (BRASIL, 2013), the State must ensure quality education, since it is a right of the entire population and something indispensable for the comprehensive training of the subject. It also emphasizes the importance of making education democratic, aiming at all access to education in a constant and effective way.

On this premise, the Law of Directives and Bases of National Education - LDB (BRASIL, 1996, p. 18) states in its Art. 22 that: “The purposes of basic education are to develop the educating student, ensure him the common training indispensable for the exercise of citizenship and provide him with the means to progress at work and in further studies. To this end, Article 32 of the aforementioned law sets out points necessary for the full education of the individual, particularly in elementary school, one of them being the student’s learning in terms of reading and writing comprehension.

However, during the new Coronavirus pandemic that was announced in Brazil in March 2020, the right to an efficient education was challenged since, with non-presence education, it became difficult to carry out practice with interaction and specific methods for the acquisition of children’s learning, especially concerning the literacy process. The social distancing measures requested by the World Health Organization (WHO) sought to contain the contagion of COVID-19 and, therefore, oriented the health institutions to establish Laws, Decrees, Ordinances, among other official documents. As a consequence of these legal orientations, the closing of schools and the implementation of remote education were determined. Thus, on March 11, 2020, the Official Gazette of the Union published Ordinance No. 356 (BRASIL, 2020), presenting in Article 3 the need for social isolation to control the transmission of the virus. Following this, the State of RN, as well as the other Brazilian states, notified the Decree No. 29.541, on March 17 of the same year, stating in Article 2 the emergency of the paralysis of classroom classes in all stages, in public and private spaces.

The teaching activities were regulated in 2021 by Decree no. 30.562, of May 11 of the same year, presenting a possible gradual and/or hybrid return, depending on each situation, on an optional basis. However, the Decree did not bring the possibility of a return to the Early Years, Elementary School classes, being valid only for the Final Years and High School. Thus, the remote context extends into the Literacy Cycle. Evidently, consequently, the municipalities needed to put into practice the measures requested.

Due to the large extent of the new Coronavirus pandemic, the period of suspension of classroom school activities has become completely uncertain. In view of this, it was necessary to find a way for children to perform school activities that would be safe and would avoid contagion by the new virus, and still fulfill the right to a public and quality education for all. On April 28, 2020, the Opinion CNE/CP # 05 was presented, declaring the possibility of a non-presential education as a way to fulfill the minimum annual workload by stating that

The development of effective school work through remote activities is one of the alternatives to reduce the replacement of presential workload at the end of the emergency situation and allow students to maintain a basic routine of school activities even away from the physical school environment. (BRASIL, 2020, p. 7).

Furthermore, the document above considers whether these non-face-to-face activities could be carried out through digital technologies, taking into account the financial issues of both educational institutions and students. However, later on May 19th, 2020, the Ministry of Education (MEC) publishes the partial homologation of the Opinion CNE/CP no. 05/2020, accepting the guidelines exposed in the above-mentioned Opinion, aiming at the organization of the school calendar and the workload required annually, based on the implementation of non presential activities, considering the Pandemic of COVID-19 and the substantiality of the social distance (BRASIL, 2020).

It can be seen that with the size and worsening of the pandemic, non-face-to-face classes became a viable resource in this previously unknown scenario. Therefore, digital technologies was essential and assiduous in remote classes. Remote teaching consists of an emergency experience and is not considered a methodology or teaching modality different from Distance Education (DE). Given that they present differences, Silva, Andrade and Brinatti (2020) discuss Emergency Remote Learning (ERE). This term formally emerged in the search for differentiating from other online education models. Thus, concerning this dissimilarity, the authors state that:

Unlike educational experiences fully designed and planned to be online, ERE responds to a sudden shift from instructional models to alternatives in a crisis situation. In these circumstances, fully remote teaching solutions that would otherwise be delivered face-to-face or as hybrid courses will return to that format once the crisis or emergency has subsided (SILVA; ANDRADE; BRINATTI, 2020, p. 9).

Therefore, the activities of ERE sought, in a non-face-to-face manner, to approximate the actions previously developed in the classroom. These activities were constituted in synchronous classes, through videoconferences and, in asynchronous classes, which do not happen simultaneously, being requested by the teacher to the students, activities to be performed during the week through printed exercises or by another virtual space that is not synchronous as, for example, through the application WhatsApp.

The experience of remote teaching - as well as other praxis - has its specificities, being an exceptional practice and, therefore, has generated concerns and misunderstandings throughout the school community. In this logic, Colello (2021) discusses the confusion between this teaching format and the other modalities in which parents and teachers disregard each type of activity’s differences, particularities, and specific functioning. Thus, the cited author (2021) argues that some parents and educators have inaccurately judged that remote learning would only be a change of actions, previously performed at school, to be developed at home and, consequently, children should spend hours in front of electronic devices. Noting that this thinking is mistaken, Oliveira et al. (2020, p. 12) argue that:

Remote teaching is not a simple transposition of face-to-face educational models to virtual spaces, as it requires adaptations of didactic planning, strategies, methodologies, and educational resources to support students in constructing active learning paths.

Thus, it was necessary to think of the ERE in its uniqueness since it processes itself differently from any other educational model. Thus, this reality demands from the educator a reflective, adequate, comprehensive, and research-based approach, considering the effectiveness of learning above all.

However, developing this practice is a great challenge, especially for public school teachers, because, as Oliveira and Junior (2020, p. 721) state, “&$91;...] the poorest schools are offered to the poorest, that is, the most precarious conditions of educational supply. Therefore, in the remote scenario, these weaknesses were even more evident considering the numerous impasses that pierced this conjuncture such as, for example, the lack of access to technological resources, the absence of an appropriate space to attend classes at home, the lack of assistance from families, the exclusion of children with disabilities, among other factors that hinder the effectiveness of the teaching-learning process in the experience of the ERE.

The difficulties were real and, often, the solution was not within the educator’s reach. Even in the face of so many adversities, we understand that applying the ERE was a viable way to execute the teaching processes aiming mainly at defending people’s lives as a consequence of the Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Thus, in this context, digital technologies were a prevalent resource assisting teachers, students, and families in developing the activities.

CONTINUING EDUCATION ASSOCIATED WITH DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES

The teacher is the professional responsible for the mediation of knowledge and, therefore, reflective action should be present in his practice. To discuss the reflective teacher, Pimenta (2006) relies on the contributions of Schõn, who understands that initial training does not offer the necessary support for teaching practice because of the setbacks and unexpected situations that arise in the daily life of the classroom. Therefore, from this perspective:

Schõn proposes a professional education based on an epistemology of practice, that is, the valorization of professional practice as a moment of knowledge construction through reflection, analysis and problematization, and the recognition of tacit knowledge, present in the solutions that professionals find in action. This knowledge in action is the tacit, implicit, internalized knowledge in action and, therefore, does not precede it. It is mobilized by professionals in their daily routine, forming a habit. Nonetheless, this knowledge is not enough. Faced with new situations that go beyond the routine, professionals create new solutions and paths, which occurs through a process of reflection in action (PIMENTA, 2006, p. 19-20).

Thus, the teacher reflection process starts from the daily needs and concerns that go beyond the school “floor”, and there is therefore the need for the educator to think and rethink the development of his or her practice and, after its realization, to re-plan for the implementation of a new reflected action. It can be seen, then, that only scientific knowledge is insufficient to effectively carry out the teaching and learning processes, making it essential to go beyond, considering the difficulties and possibilities of educational activities in a creative, thoughtful, and reflective way. With this in mind, Sacristán (2006, p. 82) tells us that “the educational practice cannot be a pedagogical technique, because it is not based on scientific knowledge and - I will be much more aggressive - it cannot be based on scientific knowledge. Pedagogical practice is a praxis, not a technique”. The author still reaffirms that only scientific knowledge is not enough because there is no ready “recipe”, as the classroom presents several unexpected events leading the teacher to reflect and develop a praxis suitable to these situations.

Based on this assumption, Pimenta (2006) presents continuing education as a result of this reflective practice, arising from the needs present in the action in which reflection provides the search for solutions and, consequently, a research process. Thus, continuing education is not restricted to training courses, converging into something much more comprehensive that emerges from the difficulties and desires faced by the educator daily, in order to achieve a meaningful practice.

That said, we understand reflective practice as a support for the effectiveness of continuing education in pedagogical praxis involving search, criticality, research, improvement, and adaptation. Among the numerous needs existing in educational action, the use of digital technologies in the classroom is present, resulting in the teacher’s duty to research, reflect, and reinvent their pedagogical praxis to meet the current educational demands. In this perspective, according to Silva (2019, p. 30):

The teacher training using pedagogical-digital technologies is developed in an approach that favors the multiple interactions between the participants of the teaching and learning process. It can enable a reflective and contextualized training approach, allowing the trainer to know and participate in the daily life of the teacher-course participant in his or her school reality, which is faced with a large technological apparatus that inhabits the students’ knowledge. Technologies and digital media must be part of the teacher’s repertoire. When incorporating them into the teaching and learning process, the teacher must reflect on their purpose as a learning tool.

In this way, the author states that digital technologies appear as an important resource in the effectiveness of learning, dialoguing between educator and student, both of whom are builders of knowledge. Thus, this tool allows a reflective process by the teacher seeking to understand its features and apply them in a meaningful and appropriate way.

Also according to Silva (2019), it is up to the educator to think and intervene on his pedagogical action, considering that teacher training is a “continuum” under constant construction. And, therefore, the globalized world demands this reflective teacher, who is prepared to deal with the demands of the educational teaching context in which the use of new technologies are evident. Regarding this qualification, Kenski (2007, p. 43-44) points out that “&$91;...] it is not enough to acquire the machine, one must learn to use it, &$91;...]”. That is, to use the technological innovations, the teacher must have domain of the artifacts, aiming the realization of an efficient pedagogical action.

But it is important to consider that neither teachers nor students are included in the digital universe, considering that this process “&$91;...] is much more than knowing how to read and write or surf the internet, but knowing how to use different resources to think about everyday life, promoting the constant construction of knowledge” (CONTE; KOBOLT; HABOWSKI, 2022, p.07). In this sense, the digital exclusion existed in the pandemic period both by the absence of technological equipment and by the low qualification in knowing how to use them when they had access, which required a period of individual training by teachers to be able to create possibilities of teaching remotely to students.

DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES AS TEACHING RESOURCES IN THE LITERACY PROCESS

Nowadays, we live in an interconnected society in which technological resources are part of most people’s daily lives. Therefore, many children have early contact with digital tools. Because of this reality, the school, as the main space for the formation of the subject/citizen, also needed to advance and keep up with the pace of the connected student. Recognizing the importance of this change, according to Moran (2000, p. 11) “Many ways of teaching today are no longer justified. Teachers and students alike have a clear sense that many conventional classes are outdated.” In fact, nowadays, traditional methods do not present success; therefore, it is necessary to evolve, intending a more contextualized teaching process in harmony with reality and its social transformations.

Given this, much is discussed about the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in education, because they make up the various media we know today (TV, radio, telephone, newspapers, magazines) employing different types of languages: oral, written, digital and audiovisual. Thus, we recognize that the relationship between technology and education is important, which makes it appropriate to think and discuss how the use of technological artifacts can contribute to the literacy process of children. According to Conte, Kobolt, and Habowski (2022), in this digital age access to information has become easy. However, even so functional illiteracy prevails even among people with college degrees, which is around 47%. This data draws our attention to the process of understanding printed or digital readings and how children feel attracted by the texts to which they are exposed. In this sense, the challenges are numerous, and it is up to the teacher to ask himself about “&$91;...] how to mobilize processes of educating with digital technologies, to interpret and anchor social learning experiences, in order to develop the different human capabilities and relationships with the knowledge of reality” (CONTE, 2022, p. 43).

Thus, regarding the teaching of reading/writing, the school should work the SES in a contextualized way in an electronic literacy dimension that includes the appropriation of digital language in the literacy process and not only focus attention on decoding phonemes and graphemes that conceive writing as a code, which are strategies of the traditional method. This method is criticized by authors such as Morais (2005), Soares (2020), and Ferreiro (2011), who defend SEA as a representation and notation of speech. However, according to Kenski (2013), with the help of digital technologies, the student’s role changes, as he or she is no longer a mere receiver of information. Regarding the end of this passive education, Freire (2013) agrees that there is no owner of knowledge and that subjects educate each other from shared experiences.

Therefore, we realize that access to digital technologies can develop children’s autonomy, since they have the information closest to them. This information is not restricted to the “school walls”, which the educator must consider considering that the students’ previous knowledge and experiences are as important as the curricular components. Therefore, in the literacy process, the literacy teacher must value the knowledge outside the school environment, understanding that this is not the only place for learning. From this perspective, Ferreiro (2011, p. 64) states that the process of acquisition of reading/writing by children

From birth, they are constructors of knowledge. In their effort to understand the world around them, they raise very difficult and abstract problems and try themselves to discover answers to them. They are building complex objects of knowledge and the writing system is one of them.

From this premise, we understand that students should be recognized as thinking and active subjects in the learning process, as subjects who question and seek answers to their questions, especially in the literacy cycle. Thus, to teach literacy from a literacy perspective, it is necessary to teach the SEA and the reading/writing skills. This work with digital technologies is done through various strategies to meet the different realities and levels of cognition in which the students are found.

In the literacy process, the educator must perform diagnostic activities, especially at the beginning of the school year, to identify the writing level of each child. Regarding the levels of writing, Ferreiro (2011) addresses the three phases that he characterizes as constructive hypotheses: pre-syllabic - levels 1 and 2; syllabic; syllabic-alphabetic and alphabetic. The first refers to the children’s initial writings represented by line drawings with undulations, scratches, or “little balls”, as well as by the interest in presenting differentiation in their writings, diversifying the repertoire of letters and the quantity, in which there is no sound value. The second stage is characterized by the beginning of sound comprehension and the perception that letters can correspond to syllables. The third phase is transitioning between the syllabic and alphabetic hypotheses, beginning a phoneme-grapheme relationship. The fourth and last phase is when the child recognizes and interprets sound values. In this phase, the child will face and solve questions involving spelling.

Therefore, the literacy teacher must know these hypotheses of writing, because this is what will enable him/her to develop activities that suit the needs of each literate learner aiming at their advancement in the learning process of writing. Based on this assumption, with the use of digital technologies, the teacher has the possibility of performing activities with this objective, such as, for example, the “hangman game” for children who are at the syllabic level, developing in them the understanding that some words have other syllables/letters and enabling them to advance from the syllabic level to the syllabic-alphabetic level. Furthermore, for children with more difficulty reading, bingos can be made, working on the initial sounds of words and word searches and then the final sounds.

Actions like these are important because they get more attention from children since they learn by playing. Rau (2013, p. 61) tells us about this perspective: “Children learn when they play because playfulness involves memory skills, attention, and concentration, in addition to the child’s pleasure in participating in pedagogical activities in a different and fun way.” In this sense, we understand the importance of emphasizing playful activities that are more meaningful and pleasurable for children, pertinent in any educational setting, especially in this online context.

Therefore, in remote teaching, with the help of technological resources, it was possible to develop playful activities considered enjoyable for the students, in which they could move around avoiding, as much as possible, monotony. These activities were adaptations that the teachers developed from others that they had already done in face-to-face teaching, and for the atypical context of remote teaching they made adjustments with the support of digital technologies. Thus, during synchronous classes, the literacy teacher spoke a syllable and asked the children to look for an object that started with the syllable in their homes. To give a better example, by quoting the syllable “PA”, the child could find a “pot” and then write this word. In this way, the learner would also understand what writing represented and its social function. But, the textual genre “recipe” could be used to deepen the work with literacy. This action is interesting because, besides developing the understanding of reading/writing as an object belonging to social practices, it provides a moment of greater interaction between children and their families.

Concerning reading and the production of texts, even online, the teacher could request the production of collective texts in different textual genres. By choosing the story’s theme, the children could tell the story while the teacher wrote. In cases of students who were in more advanced reading/writing levels, they could register the whole text. They also carried out the development of retelling activities both in written and oral form. Thus, it was necessary to work with diversified activities that consisted of the child’s appropriation of the written language and the recognition of reading and writing as a social instrument.

LITERACY AND LITERACY

The process of knowing the written language, literacy, consists of a set of skills that presents complexity and different facets. Among them are psychological, psycholinguistic, sociolinguistic, and linguistic. They all have their specificities but cover some societal conditioning aspects which should not be ignored.

This multifaceted character of literacy presented an idea of literacy even before the creation of this concept. But, according to Soares (2020) in 1980, simultaneously, the term letramento appeared in Brazil, in France illettrisme, and in Portugal, literatura. These denominations emerged in an attempt to name the phenomena existing within the process of knowledge of the written language and that were distinct from the concept of literacy. In Brazil, the term literacy was adopted from the concept of literacy, which is the antonym of illiteracy and which was not always configured as the efficient use of reading and writing in social practices. Thus, the concepts of literacy and literacy are treated in an articulated manner and with interdependence and, therefore, are often confused.

In view of this, it is important to know the concepts of “alfabetização” and “letramento,” both of which translate to literacy. According to Soares (1998) alfabetização refers, respectively, to the act of becoming literate and the condition of being literate. Thus, we note that these are distinct elements, but both are relevant and interrelated. The author also says that being ‘alphabetized’ does not mean being literate because the ‘alphabetized’ is the subject that can read and write. In contrast, somenos who is literate is not restricted only to the individual who masters reading and writing, but to the one who appropriately uses these resources in social practices.

Therefore, literacy teaching is important, considering that we live in a widely literate society. That is, a society that uses textual elements in its organization and functioning directly implies the importance of developing the necessary skills to practice the written language as a cultural and social activity.

Resuming the development of these concepts, according to Mortatti (2004), initially, in the constructivist perspective, literacy was characterized by the children’s learning to read and write. However, later, the interactionist perspective stood out in this sense by exposing that when there is the acquisition of reading and writing, the child becomes able to read and produce texts. These actions depend on the relationship between teacher and student. Therefore, knowing how to read and write, the child goes beyond the school context, participating in social practices.

That said, based on these new conceptions, there was a need to broaden the concept of literacy. According to Mortatti (2004), the official education documents included the constructivist and interactionist views regarding the teaching and acquisition of reading and writing in Brazil. Therefore, literacy and literacy are distinct but articulated procedures and conceptions. Like literacy, literacy has a multifaceted character which, according to Mortatti (2004), has different definitions, especially in a particular and social way, and also regarding its correlation with the literacy and education process in the school context. In today’s society, the use of technologies has triggered new social practices of reading and writing that characterize digital literacy, understood by Duran (2011, p. 28) as “&$91;...] the process of configuration of individuals or groups who appropriate language in social practices related directly or indirectly to reading and writing mediated by ICT.

Given the above, it can be seen that acquiring reading and writing requires two means, as Soares (2003) states, being a technical and a social method. Although different, both are important in this process and should not be disassociated, because the technique enables the child to learn to relate letters and sounds. However, for the technique to be meaningful to the individual, it is relevant that he/she can practice this knowledge in the social environment. Regarding the technique in the literacy process, the SEA is presented, being essential in this phase, considering that literacy does not occur naturally. This mechanism allows the literate student to develop an understanding of phonemes and graphemes. However, as explained below, the writing system should not be adopted as a code.

The technical aspect of the literacy process gains a new characterization with the ERE that relies on the use of digital technologies to facilitate the student’s access to school practices and works as pedagogical resources used by the teacher to mediate the children’s literacy processes. Amidst these technical aspects, it is important to consider that children’s access to school has not always guaranteed their literacy process. Soares (2020), when reporting the results of the 2016 National Literacy Assessment, shows that “&$91;...] more than half (54.7) of children in the 3rd year of elementary school were evaluated as being in ‘insufficient level’ when they would already have at least three years of schooling. These data reveal that literacy failure is still a part of Brazilian education and that access to education without quality teaching, the right to education is still denied by the absence of the right to the citizenship tool that is literacy. For this author, the failure in literacy and literacy mainly affects children from the lower social classes, who most depend on education to obtain the minimum conditions to fight for better living conditions.

This reality is configured as a challenge for teachers and interferes in their professional development, demanding continuous training to meet the demands of the pandemic moment for literacy and literacy with the support of technological artifacts, and this demands investment from the public education system in a training proposal that focuses on teaching action and is based on a conception of literacy committed to children’s learning.

REMOTE TEACHING, DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES, CONTINUING EDUCATION, AND TEACHING PRACTICES

The social distance was a great obstacle in the teaching and learning process, making it difficult, especially the work with pedagogical mediation. Thus, knowing the complexity of the literacy process, its specificities, and substantiality, as well as the importance of pedagogical mediation in this phase, there was the need to: verify the implications of the formative demands and to understand how the teachers appropriated the new technologies for the effectiveness of their practices.

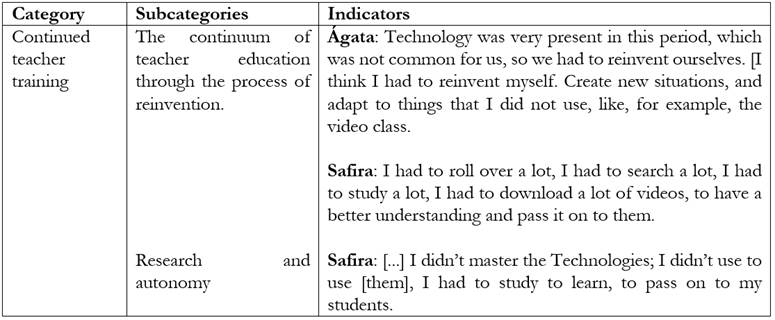

In this section of the text, we present two categories built from the Content Analysis procedure (BARDIN, 1997). These are based on the data from the interviews with the teachers Ágata and Safira, who teach in the 1st and 2nd year of elementary school, at the Francisco Francelino de Moura Municipal School. The first category is the continuing education of teachers, and the second is the use of digital technologies. These categories, analyzed in the following subsections, are related to the researched teachers’ impressions and opinions regarding ERE.

The importance of continuing education in the practice of literacy teachers in times of pandemic

New times call for new actions, skills, and perspectives. The importance of innovative education using ICT has long been discussed. This is because society has changed and we live in a globalized world, taken over by digital technologies and the spread of information at a frenetic pace. All these social changes also imply the need for the teaching professional to innovate in his pedagogical praxis, adapting it to the demands of reality.

So, with the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic and, consequently, the ERE, it made innovation more than a necessary procedure. It became an obligation. The indispensability of using digital technologies in this context made educators reflect and modify their way of teaching immediately. For Conte (2022, p. 58) during the pandemic, “&$91;...] the teacher’s work has become a constant struggle against the sensorial and technical stimuli of the media and virtual networks, which has caused overstimulation (hallucinating work rhythms) and even put at risk the educational promises of provoking restless thinking in collective work. Teachers were given challenges that required research and study to create new teaching methodologies. However, practice with innovative principles presupposes a reflective action by the teacher because, according to Pimenta (2006), the reflective process is part of us — human beings. Thus, as a mediator of educational actions and experiencing different situations daily in the classroom, the educator needs to reflect, seek and research to improve his or her praxis and, above all, the effectiveness of learning.

The reflective process in the pedagogical praxis is part of the training that comes from the teacher’s desire to seek new education methods. With the emergence of the ERE experience, educators began to reflect, research, and seek to master the digital resources used to develop the most efficient work possible. These aspects were emphasized in our study, since, in their answers, the literacy teachers Agatha and Safira showed difficulties in dealing with the new resources resulting in the need to reinvent themselves, reflecting, and researching. These aspects are evidenced in the category “Continuing education”:

When we observe the indicators, we notice the recurrence of aspects such as reinvention and research, in which the teachers sought knowledge of new resources, stressing their proper use to perform meaningful work. This desire to improve the educational practice represents a “continuum” since the teacher performs a self-reflection by intervening in her performance, as Silva (2019) points out. These factors are presented in the subcategory “The continuum of teacher training through the reinvention process,” in which teacher Ágata states that, in the remote context, the use of digital resources was constant, something unusual in another time and; consequently, she had to reinvent her practice.

This reinvention also appears in the subcategory “Research and autonomy,” as Safira says that her pedagogical practice had to go through many changes and, thus, she had to do her best to understand the new digital teaching artifacts and be able to teach her students. Thus, Safira says she needed to research and study a lot since she did not master digital technologies. So, she tried to improve herself to develop meaningful work. That said, it is important to highlight that this need to remake herself was given by the little use and mastery of new digital technologies that remote teaching requires, making these changes occur in a forced and indispensable way. Thus, these new ways of teaching were imposed by the pandemic reality. However, this process was essential for the development of new skills and experiences in the pedagogical practice of the teachers of the Literacy Cycle, because Ágata and Safira spared no effort in conducting the most efficient action possible, through research, commitment, and reflection, even in the face of numerous impasses and previously unknown situations. As reinforced by Cordeiro (2022), it is the school’s responsibility “&$91;...] to mediate and use, intentionally and pedagogically, all the old and new means of promoting learning that will form these people integrally”. Thus, the literacy teachers’ new practices were adaptations of what they did in face-to-face teaching and had to reinvent them with the addition of digital technologies.

It can be seen, then, that the literacy teachers went through a reinvention, adaptation, and research process. The development of these h abilities is guided by reflection on the pedagogical praxis that emerges from the daily and unique demands of the school environment. Knowing this, Pimenta (2006) warns us that initial training alone does not prepare teachers for the complex teaching exercise. Thus, if the reflective practice was already commonly necessary in the remote context, it has become indispensable, given this absolutely exceptional conjuncture.

Thus, we see the difficulties faced by teachers in the Literacy Cycle undergoing a reflective process and, consequently, continuous training. Ágata and Sapphira did not mention participation in training courses, which marks the absence of the public education system in assisting teachers in their qualification for the use of digital technologies, which may have caused certain insecurity among teachers in the ERE . However, this “continuum” of training is also processed with the educator’s personal and formative search to provide the best for their students. Sacristán (2006) shares this idea emphasizing that scientific knowledge is not everything, because the educator improves from the concerns and needs imposed on them in the classroom. Similarly, Pimenta (2006) considers that continuing education transcends the means of training and is constituted by reflection through reality. But given the demands of remote teaching, in which teachers have so far made little use of digital technologies, we believe that the promotion of continuing education courses by the school systems was necessary to support teachers in improving their working conditions.

In view of this, it is understood that the ERE's abrupt experience impacted the literacy teachers’ practices in several aspects. The research also revealed that a new cultural identity has been forming in students as: the dispersion or exitation of the senses by the audivisuality present in technological artifacts (CONTE, 2022) that has been configured as challenges imposed on teachers. To create strategies for developing skills necessary for the teaching exercise, the literacy teachers needed to master the new resources and improve the action through autonomy, reflection, research and commitment to the learning of children in the literacy process.

The assiduous use of digital technologies in the practice of female literacy teachers

We live in an interconnected world, which implies the need for new ways of teaching and learning. Knowing this, Moran (2000) states that some teaching methodologies are outdated and thus there is a need to innovate. Thinking about innovating in teaching involves taking care of teachers’ training with continuing education proposals that ensure that they can “&$91;...] analyze everyday school situations and their work in order to understand them in their complexity, their totality, and their context, that is, they understand what they do, how they do it, and why they do it” (ANDRÉ, 2020, p. 27). For a long time, some schools and educators resisted these changes by using more “traditional” practices. However, with the determination of the ERE, digital technologies emerged vigorously in educational practices and it became necessary to employ them, seeking to know these resources and adapt them to each reality.

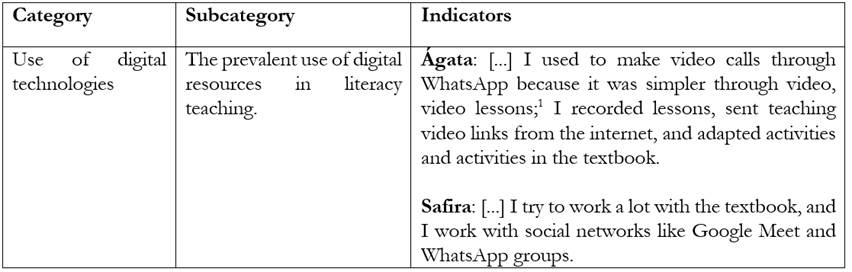

The discussion about using these digital resources in teaching is not very recent, but it has gained greater visibility in education with the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Kenski (2007), ICT can be understood as a language, as it enables social communication processes. In the pandemic context, this conception became even more evident, since communications/interactions succeeded massively through these technologies. In the educational field it was no different, and the assiduous presence of digital resources in the practice of literacy teachers allowed us, from the interviews, to formulate the category “Use of digital technologies”:

Considering the indicators, the subcategory “The prevalent use of digital resources in teaching literacy” was built due to the emphasis that both teachers express on using these artifacts. Although Agatha and Safira express the use of the textbook, digital technologies prevail, especially regarding the use of applications such as Google Meet and WhatsApp. Thus, the literacy teachers sought to conduct synchronous and asynchronous classes, so that children would not be unattended, besides developing a more diversified practice with different types of activities.

Both educators used the technological resources to carry out the pedagogical activities, considering that, due to remote teaching experience, these resources became indispensable and, therefore, assiduous in the educational actions. However, this experience opened space for a reflection on aspects involving social inequality, considering that the restricted access to technologies in the country is still a reality, implying a more closed teaching and learning process, even if unintentionally, depriving some students belonging to the less favored social classes from having the right to learn. This reality was evidenced in a survey published in the studies of Saviani and Galvão (2021, p.38), which portrays that “&$91;...] there are more than 4.5 million Brazilians without access to broadband internet and more than 50% of homes in rural areas do not have internet access. In a reality in which 38% of homes have no internet access and 58% have no computer. Given this reality, one can state that access to digital resources is not yet a reality for everyone. It may have left a gap in the learning of literate students who did not have them available due to their insufficient financial conditions to acquire them.

The discussions about the use of digital technologies in this paper indicate that these resources can help children’s learning, especially during the literacy process. As Costa, Cassimiro, and Silva (2021) state, these resources motivate and attract the attention of the students, grounding their learning, but can also disperse them from the pedagogical activities when they are not well planned and inserted intentionally and with objectivity in the mediation of learning by the literacy teacher . For Kenski (2013) the use of digital technologies enables an innovation in the teaching and learning processes of reading and writing, making the student more autonomous. Nevertheless, in our view, it needs the mediated activity of the teacher for these two processes to happen with quality.

In this sense, it is understood that digital technologies can contribute to this teaching. However, this contribution may depend on several factors, among them, how this content is worked and how the student appropriates it. Moreover, it is important to recognize differences between print and digital reading, as they involve specific languages and literacy that require learning mediated by the teacher and the new artifacts.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In the course of this study, we analyzed the implications of the use of digital technologies in the process of continuing education and in the practices of literacy teachers, during remote teaching, in 2020, in the Municipal School Francisco Francelino de Moura. By using the Content Analysis technique (BARDIN, 1997), it was possible to identify two categories based on the statements of the teachers surveyed: Continuing education and the use of digital technologies.

Regarding continuing education, it was found that the teachers developed new practices, especially using digital technologies. Despite the difficulties encountered, they sought to learn about and appropriate these resources, resulting in a reflective practice of constant research and improvement concerning continuing education. In addition, there was an absence of training courses for teachers that would meet the demands of the ERE required during the COVID-19 pandemic. This aspect was configured as a right denied to the teachers and, at the same time, insecurity when taking on a new way of teaching. The literacy teachers had to research, reinvent and innovate their teaching practices based on what they were already doing in classroom teaching.

As for the use of digital technologies, it was possible to see that they have gained greater visibility and usefulness during the ERE, but the inequality of access to technological artifacts by several students excluded them from teaching practices more accessible to the content addressed by teachers, which may have generated damage to the learning processes. The study also revealed that digital resources had generated a new cultural identity for students by providing access to information and, at the same time, distraction, which required a conscious and intentional mediation by the literacy teacher to obtain better results in their teaching practices.

Given the results of the study expressed here, it is inferred that this theme can foster future research that also seeks to understand the aspects that permeate the teaching of literacy in the non-face-to-face model, as well as studies that aim to discuss the experience of the ERE more comprehensively, its concerns, possibilities, and challenges. Even with the return to face-to-face teaching, many remote teaching techniques will remain part of teaching practices, especially activities requiring the approximation of subjects long distances away, where technology facilitates their virtual presence.

In summary, it was understood that the ERE was the most viable teaching model in the face of the need for social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic and that even in the face of the challenges faced by teachers, such as the lack of access by some students to technological means, but the literacy teachers when redoing their practices, qualified in the use of digital artifacts that remained in their teaching activity in the face-to-face return.

The reality surveyed revealed that even in the face of numerous difficulties, it is necessary to hope, not settle before the scenario of fragility and the deficits that the pandemic left in the students’ learning. At this point, it is necessary to proceed with the certainty that better days are ahead, without ignoring the various challenges experienced during the ERE, but seeing them as learning for the realization of a different education than before, constituting even more successful, innovative and emancipatory in the return of classroom education that will never be as before.

REFERÊNCIAS

ANDRÉ, Marli. Formar o professor pesquisador para um novo desenvolvimento profissional. In: ANDRÉ, Marli(Org.) Práticas inovadoras na formação de professores. Campinas/SP: Papirus, 2016, p. 13-34. [ Links ]

BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de conteúdo. 70. ed.Lisboa: Editora, 1977. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. 4. ed. Brasília, DF: Senado Federal, Coordenação de Edições Técnicas, 1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Brasília: MEC/SEB, 2017. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/BNCC_EI_EF_110518_versaofinal_site.pdf > Acesso em: 8 out. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação/ Conselho Nacional de Educação. Parecer CNE/CP nº 05 de 28 de abril de 2020. Distrito Federal: Ministério da Educação, 28 de abril de2020. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=145011-pcp005-20&category_slug=marco-2020-pdf&Itemid=30192 . Acesso em:07 de fevereiro de 2022. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Diário Oficial da União. Despacho de 29 de maio de2020. Disponível em:<Disponível em:https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/despacho-de-29-de-maio-de-2020-259412931 > Acesso em:06/03/2022. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais Gerais da Educação Básica. Brasília: MEC/SEB, 2013. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Portaria n.º 356, de 11 de Março de 2020. Dispõe sobre a regulamentação e operacionalização do disposto na Lei nº 13.979, de 6 de fevereiro de 2020, que estabelece as medidas para enfrentamento da emergência de saúde pública de importância internacional decorrente do coronavírus (COVID-19). Diário Oficial da União. Publicado em: 12/03/2022, Edição: 49, Seção: 1, p. 185. [ Links ]

COLELLO, Silvia M. Gasparin. Alfabetização em tempos de pandemia. In: CONVENIT INTERNACIONAL, 35. São Paulo: Cemoroc - Feusp, 2021. v. 1, p. 143-164. [ Links ]

CONTE, E.; KOBOLT, M. E. de P.; HABOWSKI, A. C. Leitura e escrita na cultura digital. Educação, v. 47, n. 1, e33/p. 1-30, 2022. Disponível em: <https://doi.org/10.5902/1984644443953> Acesso em: 08 ago. 2022. [ Links ]

CONTE, E. Educação, Desigualdades e Tecnologias Digitais em Tempos de Pandemia. In: RONDINI, Carina Alexandra. (Org.). Paradoxos da Escola e da Sociedade na Contemporaneidade. 1. ed. Porto Alegre, RS: Editora Fi, 2022, v. 1, p. 32-62. < https://www.editorafi.org/ebook/507paradoxos > Acesso em 08 ago. 2022. [ Links ]

CORDEIRO, Fabiana A. Menegazzo. Quando o caos da pandemia passar, quem terá maior força: os velhos hábitos da Escola tradicional ou os novos ensinamentos da escola na pandemia da COVID-19? In: CONTE, E. Educação, Desigualdades e Tecnologias Digitais em Tempos de Pandemia. In: RONDINI, Carina Alexandra. (Org.). Paradoxos da Escola e da Sociedade na Contemporaneidade. 1. ed. Porto Alegre, RS: Editora Fi, 2022, v. 1, p. 32-62. < https://www.editorafi.org/ebook/507paradoxos > Acesso em 08 ago. 2022. [ Links ]

COSTA, Renato Pinheiro da; CASSIMIRO, Élida Estevão; SILVA, Rozinaldo Ribeiro da. Tecnologias no processo de alfabetização nos anos iniciais do ensino fundamental. Revista Docência e Cibercultura, Rio de Janeiro: v. 5, n. 1, p. 97-116, 2021. [ Links ]

FERREIRO, Emilia. Reflexões sobre alfabetização. 26. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia do oprimido. 1. ed.Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2013. [ Links ]

KENSKI, Vani Moreira. Educação e tecnologias: O novo ritmo da informação. 2. ed. Campinas: Papirus, 2007. [ Links ]

KENSKI, Vani Moreira. Tecnologias e ensino presencial e a distância. 1. ed. Campinas: Papirus, 2013. [ Links ]

MINAYO, Maria Cecília de Souza et al. Pesquisa Social: Teoria, método e criatividade. 21 ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2002. [ Links ]

MORAIS, Artur Gomes de; ALBUQUERQUE, Eliana Borges Correia de; LEAL, Telma Ferraz. Alfabetização: apropriação do sistema de escrita alfabética. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2005. [ Links ]

MORAN, José Manuel. Ensino e aprendizagem inovadores com as tecnologias audiovisuais e telemáticas. In: MASETTO, Marcos T; BEHRENS, Marilda Aparecida. Novas tecnologias e mediação pedagógica. Campinas: Papirus, 2000. p. 11-63. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, João Flávio de Castro. Os telecursos da Rede Globo: a mídia televisiva no sistema de educação a distância (1978-1998). 2006.181 p. Dissertação (Mestrado). Programa de Pós-Graduação em História, Instituto de Ciência Humanas, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, 2006 . [ Links ]

MORTATTI, Maria do Rosário Longo. Das Primeiras Letras ao letramento. In: MORTATTI, Maria do Rosário Longo. Educação e Letramento. São Paulo: UNESP. Col. Paradidáticos, 2004. p. 49-82. [ Links ]

MORTATTI, Maria do Rosário Longo. Letramento, alfabetização, escolarização e educação. In: MORTATTI, Maria do Rosário Longo. Educação e Letramento. São Paulo: UNESP. Col. Paradidáticos , 2004, p. 97-116. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Maria do Socorro de Lima. et al. Diálogos com docentes sobre o ensino remoto e planejamento didático. Recife: EDUFRPE, 2020. p. 45. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Dalila Andrade. JÚNIOR, Edmilson Antonio Pereira. Trabalho docente em tempos de pandemia. In: Retratos da Escola, Brasília: v. 14, n. 30, p. 719-735, 2020. [ Links ]

PIMENTA, Selma Garrido. Professor reflexivo: construindo uma crítica. In: PIMENTA, Selma Garrido; GHEDIN, Evandro (orgs.). Professor Reflexivo no Brasil: gênese e critica de um conceito. São Paulo: Cortez Editora, 2006. p. 17-52. [ Links ]

RAU, Maria Cristina Trois Dorneles. A ludicidade na educação: uma atitude pedagógica. 1. ed. Curitiba: Ibpex, 2013. [ Links ]

RIO GRANDE DO NORTE. Decreto n.º 29.524, de 17 de Março de 2020. Dispõe sobre medidas temporárias para o enfrentamento da Situação de Emergência em Saúde Pública provocada pelo novo Coronavírus (COVID-19). Diário Oficial do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte. Natal/RN, 17 de março de 2020. [ Links ]

RIO GRANDE DO NORTE. Decreto nº 30.562, de 11 de Maio de 2021. Prorroga as medidas restritivas, de caráter excepcional e temporário, destinadas ao enfrentamento da pandemia da COVID-19, no âmbito do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte e estabelece a retomada gradual atividades socioeconômicas. Diário Oficial do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte. Natal/RN, 11/05/2021. [ Links ]

SACRISTÁN, José Gimeno. Tendências investigativas na formação de professores. In: PIMENTA, Selma Garrido; GHEDIN, Evandro (orgs.). Professor Reflexivo no Brasil: gênese e critica de um conceito. São Paulo: Cortez Editora, 2006. p. 81-87. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, Dermeval; GALVÃO, Ana Carolina. Educação na pandemia: a falácia do ensino remoto. Universidade e Sociedade, ano XXXI n. 67, jan. 2021 [ Links ]

SILVA, Girlene Feitosa da. Formação de professores e as tecnologias digitais: a contextualização da prática na aprendizagem. 1. ed. Jundiaí: Paco Editorial, 2019. [ Links ]

SILVA, Silvio Luiz Rutz da; ANDRADE; André Vitor Chaves de; BRINATTI, André Maurício. Ensino Remoto Emergencial. Paraná: Dos autores, 2020. [ Links ]

SOARES, Magda. Alfabetização e Letramento. 7. ed. São Paulo: Contexto, 2020. [ Links ]

SOARES, Magda. Alfabetização: a questão dos métodos. 1. ed. São Paulo: Contexto, 2020. [ Links ]

SOARES, Magda. Letramento e alfabetização: as muitas facetas. Rio de Janeiro: Rev. Bras. Educ. 2003. [ Links ]

SOARES, Magda. Letramento: um tema em três gêneros. 1. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 1998. [ Links ]

SOARES, Magda. Alfaletrar: toda criança pode aprender a ler e a escrever. São Paulo: Contexto, 2020. 352 p. [ Links ]

Received: April 03, 2022; Accepted: September 27, 2022

texto en

texto en