Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.39 Belo Horizonte 2023 Epub 05-Jul-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469837653

ARTICLE

PEDAGOGICAL FORMATION IN DIALOGICAL LEARNING: CONTRIBUTIONS TO TEACHER TRAINING IN TIMES OF SOCIAL DISTANCING1

1Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar). São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil

This article presents the results of the research developed from the course of Dialogical Learning formation, offered remotely during the social distancing period caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and focused specifically on the teacher training. The research was carried out through an electronic form filled by participants, as well as reports and a communicative focused group, all performed after the course’s end. The aim was to understand the impact of the course in Dialogical Learning formation on educators’ theoretical and practical knowledge and its relation to facing social isolation. Based on the theoretical basis of the Communicative Methodology, the answers obtained were listed as transforming elements and excluding elements according to their contributions to the course of educators’ formation and the pandemic facing. As result, we highlight the instrumental dimension, the necessity of ensuring the teacher training based on scientific evidence, and the creation of sense as transforming elements. Data also reveal that a lack of dialog and a vertical structure in teaching systems promote distance between teaching practices and better educational results. The elements pointed out as transforming provided support for the participants to look for answers to the issues they faced in their everyday routines, both in professional and personal contexts. We hope this article may contribute to the teacher training, therefore promoting reflection on the necessity of aligning this formation with studies produced by the international scientific community.

Keywords: dialogical learning; teacher training; social distancing

Este artigo apresenta resultados de pesquisa desenvolvida a partir do curso de formação em Aprendizagem Dialógica, ofertado remotamente durante o período de distanciamento social ocasionado pela pandemia da COVID-19, com recorte específico sobre a formação de professores(as). A pesquisa foi realizada por meio de formulário eletrônico preenchido pelos(as) cursistas, relatos e grupo focal comunicativo, realizados após o término do curso. O objetivo foi compreender o impacto do curso de formação em Aprendizagem Dialógica no conhecimento teórico e prático de professores(as) e sua relação com o enfrentamento do isolamento social. Pautados no referencial da Metodologia Comunicativa, as respostas obtidas foram sistematizadas em elementos transformadores e excludentes em relação às contribuições do curso para a formação de professores(as) e para o enfrentamento da pandemia. Como resultados, destacam-se a dimensão instrumental, a necessidade da formação de professores(as) aliada às evidências científicas e a criação de sentido como elementos transformadores. Os dados também revelaram que a falta de diálogo e a estrutura verticalizada dos sistemas de ensino são elementos que distanciam as práticas pedagógicas dos(as) professores(as) de melhores resultados educacionais. Os elementos apontados como transformadores deram suporte para que os(as) participantes buscassem respostas para os problemas enfrentados em seus cotidianos profissionais e pessoais. Esperamos que este artigo contribua com o campo da formação de professores(as), promovendo reflexão sobre a necessidade de alinhar essa formação com os estudos produzidos pela comunidade científica internacional.

Palavras-chave: aprendizagem dialógica; formação de professores(as); distanciamento social

En este artículo se presentan resultados de la investigación desarrollada a partir del curso de formación en Aprendizaje Dialógico ofrecido de forma remota, durante el período de aislamiento social provocado por la pandemia del COVID-19, con un enfoque específico en la formación docente. La investigación se llevó a cabo a través de un formulario electrónico rellenado por los participantes del curso, informes y un grupo de enfoque comunicativo, realizado tras la finalización el curso. El objetivo fue comprender el impacto del curso de formación en Aprendizaje Dialógico sobre los conocimientos teóricos y prácticos de los docentes y su relación con el afrontamiento del aislamiento social. Con base en el marco de la Metodología Comunicativa, las respuestas obtenidas fueron sistematizadas en elementos transformadores y excluyentes en relación a los aportes del curso a la formación docente y al combate a la pandemia. Como resultados, destacamos la dimensión instrumental, la necesidad de formación docente combinada con evidencia científica y la creación de sentido como elementos transformadores. Los datos también revelaron que la falta de diálogo y la estructura vertical de los sistemas educativos son elementos que distancian las prácticas pedagógicas de los docentes de mejores resultados educativos. Los elementos identificados como transformadores brindaron apoyo a los participantes en la búsqueda de respuestas a los problemas que enfrentan en su día a día profesional y personal. Esperamos que este artículo contribuya en el campo de la formación docente, promoviendo la reflexión sobre la necesidad de alinear esta formación con los estudios producidos por la comunidad científica internacional.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje dialógico; formación de profesores; aislamiento social

INTRODUCTION

We present, in this article, a research focus developed from the perspective of Dialogical Teaching Formation and performed by educators of the teaching field belonging to a federal university. The focus used in this study analyzes data collected from 16 participating professors of the Dialogical Teaching Formation. The aim was to understand the impact of the course on the training of Dialogical Learning regarding theoretical and practical knowledge of professors and its relation to facing the social isolation brought by the COVID-19 pandemic.

We know that numerous world sectors were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Education, especially, has been the object of research of both national and international research and generated worry in global organizations (UNESCO, 2020a) on how to minimize the negative effects caused by isolation and the growing social inequity that is reaching vulnerable groups (GAYNOR, WILSON, 2020). In March 2020, global reality in education revealed the closing of schools and the recognition of remote teaching as the alternative to the pandemic. In this period, 100 countries had already announced the interruption of face-to-face school activities throughout all education levels (UNESCO, 2020a), affecting the educational reality for both students and educators and relatives (UNESCO, 2020b). In Brazil, the Ministry of Education established and regulated the implantation of educational activities through virtual means (BRASIL, 2020a) and flexed the quantity of minimal required school days, therefore preserving the course load of subjects (BRASIL, 2020b; 2020c).

As for educators, UNESCO (2020b) drew attention to the confusion and stressful moments generated by social isolation, suggesting the creation of communities formed by educators, parents, and school managers to promote discussions that would contribute to facing difficulties experienced during the pandemic (UNESCO, 2020a). The necessity for conjoint work and groups that support each other have already appeared in research, indicating the necessity for the educators’ formation to be science-based (BALL, 2012; FELDMAN; OZALP, 2019; SHONKOFF, 2020), and, therefore, suggesting the shared reading by instructors and students (GREENLEAF; LITMAN; MARPLE, 2018; ÁLVAREZ, 2020) and the interaction between more and less experienced educators for obtaining efficient educational results (FOX et al., 2015).

At this moment, it is worth basing actions on what Shonkoff calls the “better, more trustworthy available scientific knowledge” (SHONKOFF, 2020, p. 1), demonstrating an important social impact on research results so that they can be applied and indeed better some aspect of our societies (AIELLO et al., 2020). In this sense, international studies investigated the impacts on the dialogical teacher training, exhibiting that these programs contribute to the identification of what functions in education, based on scientific-based studies, and resulting in the bettering of the professional performance and the affected students (PENUEL et al., 2007; PIANTA et al., 2008; DESIMONE, 2009; DOWNER et al., 2009; HIGGINS; PARSONS, 2009; CORDINGLEY, 2015; NAEGHEL et al., 2016; FLECHA; BUSLON, 2016; JUKES et al., 2017; KUTAKA et al., 2017, ORAMAS; FLECHA, 2021).

In light of the necessity of amplifying the social isolation period, remote teaching emerged for the instructor as an alternative for continuing school work, changing how they developed teaching practices. In compliance with this new reality, the Dialogical Teaching Formation course was developed through remote ways for attending everyone. It happens that, despite the accessibility in a context of isolation necessity, experiencing a course through remote ways, a course based on Dialogical Learning, enabled educators to develop new teaching methods used in their realities.

Lastly, it is noteworthy to observe that the aim of this work was attained, given that we obtained data such as on how the participation of educators in the course of Dialogical Learning Formation amplified their theoretical and practical knowledge through an instrumental dimension, as well as contributing to the creation of sense (AUBERT et al., 2016) and the solidarity feeling, supporting them to face social isolation throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Below, we will describe how the course took place, and the theoretical bases that sustain it will be presented.

DIALOGICAL TEACHING FORMATION COURSE

In compliance with international research on the teacher training, the INCLUD-ED Integrated Project (2006-2011), the 6th EU Research Framework Programme, developed the concept of Successful Educational Actions2 (SEAs). SEAs are interventions carried out by educators and the school community to better students’ academic performance and the interpersonal relationships of institutions that receive these (CREA, 2012).

Based on scientific evidence, SEAs are universal and possible to be transferred, founded on the egalitarian dialog between educators, students, relatives, and community members, and may be developed throughout all educational levels. It is worth highlighting, therefore, Dialogical Teaching Workshop (DTW) as a successful way of teaching formation linked to the reading of books and scientific articles internationally recognized and capable of recovering the sense of the profession from a social transformation perspective (ROCA CAMPOS; GÓMEZ; BURGUÉS, 2015) from childhood education (RODRÍGUEZ-ORAMAS et al., 2020) to higher education (BARROS-DEL RIO; ÁLVAREZ; MOLINA ROLDÁN, 2021). Performed in numerous countries (Spain, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, etc.), the SEAa are propelled by Teaching Communities that demonstrably contribute to the social and educational development of the people involved, providing better opportunities for everyone (GARCÍA-CARRIÓN et al., 2020).

In Brazil, the Center of Investigation and Social and Educational Action (NIASE) has coordinated research and diffusing work with the SEAs since 2012, integrating the extension program and offering subjects in the graduation and post-graduation courses of the federal university. Dialogical Teaching Formation that operated the research and results of this article was offered by NIASE and taught in the second semester of 2020, inserted in an integrational curricular activity set between teaching, research, and extension.

In this sense, the combination of the abovementioned triad is present in subjects offered to students, research production by the members of the formative team and other participants, as well as in the articulation with systems of teaching and community participation through the following objectives:

1 - Promoting the initial, ongoing formation based on scientific evidence of Dialogical Learning in a way that enhances its theoretical and methodological principles for teaching practices.

2 - Comprehending and analyzing Successful Educational Actions performed in schools.

3 - Articulating teaching-research-extension by involving graduation and post-graduation students in activities and elaborating research on the theme. (SILVA; BRAGA; MELLO, 2021, p. 254).

Course promotion happened through the social media of the center and the university, and participants’ registration was carried out through Google Forms. Among the 80 people initially registered, 43 (graduation and post-graduation students, as well as professors, all over the age of 18) fully engaged with the course and finished it. Sixteen professors answered the questionnaire based on the research focus portrayed in this article.

The course3 had a workload of 60 hours divided into eight weeks and was backed by technological tools4 with activities in the virtual learning environment (VLE) and weekly synchronous meetings that took place through Google Meet video calls. Inserted in an integrative curricular activity set between teaching, research, and extension (ACIEPE) and performed within the principles of Dialogical Learning, the course was coordinated by a professor of the university and members of the center who participated of the organizational team (constituted by professors of the university, teachers, educators, and graduate and post-graduate students of the university). The studied content was based on the reading of the book “Aprendizagem Dialógica na Sociedade da Informação” (AUBERT et al., 2016), focused on the following amendment: Conceptualization of the Dialogical Learning, discussion on learning theories and Successful Educational Actions; presentation and analysis of examples of Successful Educational Actions and teaching practices throughout different teaching levels. The group also performed readings of articles on research that brought international-scale results.

Since we emphasized the Dialogical Teaching Workshop, the intersubjective dialog is promoted for it stimulates reflection and respectful listening. The reading dynamic adopted on the course consists of agreeing, priorly, with the group, on the chapter that will be read for the following week. At the meeting, after reading the text, participants expose their highlighted excerpts and comment on the content, establishing a relationship with their everyday personal and professional routines. The asynchronous activity took place at the VLE and consisted of producing a reflective text on the studied content, which was delivered by the end of the course.

Based on the theoretical and methodological referential of Dialogical Learning, the course was developed considering the dialog as a central generator element of learning (AUBERT et al., 2016), anchored on the contributions of Paulo Freire and Jürgen Habermas. They defend education for social transformation. These authors support the seven principles of Dialogical Learning (AUBERT et al., 2016), including Egalitarian dialog, Cultural intelligence, Transformation, Instrumental dimension, Sense creation, Solidarity, and Difference equality.

Through reading and dialog, the formation sought to offer a theoretical and practical basis for SEAs, aiming at the possibility of transferring these to the contexts surrounding the participants. The elaboration and conduction of the Dialogical Teaching Formation have taken care of the ethical and scientific rigor that underlies the theory of Dialogical Learning and NIASE’s actions to offer training based on scientific evidence.

On the commonly diffused teacher training in schools, it is notorious that little is discussed on the main international results about teaching formation or the results for problems faced in the classroom. Content originating from mass communication is rarely diffused, informally diffused, going against the international debate about teaching formation linked to scientific evidence.

Corroborating the ideas presented, Silva, Braga, and Melo (2021) point out that

The centrality of scientific evidence on the teacher training, be it basic or superior, allows educators to describe and analyze their practices more efficiently and deeply with the community (family, managers, universities, etc.). Without a solidified scientific basis, the debate around teaching and learning issues becomes discussions constituted of individual opinions. When the formation is based on scientific evidence, a result of solidified research with recognized methods, the community can understand how to assess teaching practices with autonomy and decide which are the better ways to ensure education of maximum quality for everyone. (SILVA; BRAGA; MELLO, 2021, p. 255).

The intent of course’s content is aimed at theoretical and practical deepening, avoiding discussions and opinions that are not based and supported, as well as wrong conclusions. Given that it is set in the format of a Dialogical Teaching Workshop, the egalitarian dialog is the basis for highlighted knowledge resulting from the reading and also professional practices that generate results that are collectively results, ensuring the participation and inclusion of all voices. Intersubjective dialog contributes to the deepening of the theory and its relation with effective professional practices, experiencing the process of the praxis by Freire (2004), “rescuing the intellectual character of teaching” (SILVA; BRAGA; MELLO, 2021, p. 256). In this study, we analyzed the results obtained with 16 participant educators under the following aspect: theoretical and practical knowledge of educators and their relation with facing social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results were analyzed in detail in the following sections of this article.

METHOD

After setting the research focus on the 16 professors, the answers obtained were analyzed from the perspective of the following question: What is the impact of the course of Dialogical Learning formation on the theoretical and practical knowledge of educators and its link with the endurance of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic? The research question is sustained on evidence of the Dialogical Learning theory and amplifies the instrumental dimension and sense creation of people (GÓMEZ et al., 2006). In compliance with the results of the research by Silva, Braga, and Melo (2021), carried out with all participants, our focus was chosen to aim at contributing with the elaboration of parameters for the teacher training which directly affect the “professional and personal act in environments of inequality and suffering, as is the case of the current context” (SILVA; BRAGA; MELO, 2021, p. 256).

With the approval of the Human Research Ethics Committee of the university, the invitation to participate in the research was made to those that engaged in the course in its entirety (graduation and post-graduation students and educators over the age of 18 years old), which results in 43 people, being 16 of these, professors, the number that corresponded to this article focus. The educators made the invitation in the Table of the course through email and synchronous conversation for those who wanted to obtain more information and solve doubts about the research. The Informed Consent Form (ICF) was sent via email, through a Google Forms link, for it to be read and accepted by participants. After consenting, participants were guided toward the electronic questionnaire with closed and open-ended questions. The questionnaire contained questions about: a) the participant’s characterization data; b) the course (content, remote access, conditions of performance, methodology, learning, critics, and suggestions); and c) work and life situation, as well as worries faced throughout the pandemic. After answering the questionnaire, they were invited to participate in a focused group and engage in interviews for us to acquire further information on the participants.

Collected data from the questionnaire about the characterization of the participants, quantitatively organized by answer frequency and corresponding percentage calculus, generated with the aid of the Infogram platform. Qualitative data information will also be presented, a result of the open-ended questions of the questionnaire, which was organized through an analysis of the content in Tables as indicated by the Communicative Methodology of Research (GÓMEZ; PUIGVERT; FLECHA, 2010). This analysis enables the cognition of excluding and transforming elements inserted in the contexts of the world of life and the system. By system, one should understand the spaces, institutions, and organizations that are self-regulated by power spheres such as the market and the government, while the world of life represents daily experiences and communicative acts of people inserted in society and historical times (HABERMAS, 2012). In the face of the necessity of scrutinizing the researched theme, a focused group and interviews with participants were articulated, aiming at reflecting and interpreting elements from the questionnaire.

Since it consists of a work that presents both quantitative and qualitative data, one may consider it mixed research with a concomitant character (CRESWELL, 2012). Quantitative data collection corresponded to the closed questions in the Likert scale contained in the questionnaire, with five levels of answer (totally agreed; partially agreed; not agreed nor disagreed; partially disagreed; totally disagreed). Qualitative data collection was performed through open-ended questions in which participants could expose their ideas. For data collection, we used a categorical analysis (BARDIN, 2011), determining the frequency of repetition of terms and elements taken from open-ended questions of the questionnaire, then confronting it with the data obtained from the closed questions. With the first data collection and organization in hand, we articulated the focused, communicative group and the interviews for the data analysis with the participants. All data were grouped by the similitude of answer, categorized as excluding or transforming elements according to levels of realization: system or world of life. In the Results section, we used the descriptions made through the speech of participants collected in interviews and the focused, communicative group to exemplify and evidence the results obtained in the analysis. This form of grouping and categorization is guided by the Communicative Methodology (FLECHA, 2014; FLECHA; SOLER, 2014), which sustained the development of the entirety of the research and has as a primary trait the supplement of resources that contribute to the transformation of excluding elements, as well as encourage transforming elements through recommendations to society, the public power, and other institutions or people interested on the researched theme (GÓMEZ et al., 2006).

RESULTS

The Dialogical Learning Formation course counted with 80 people registered, from which 43 completely participated in the course and finished it. Among the research participants, our research focus will include 16 educators that answered the questionnaire. Therefore, the characterization of these 16 participants will be presented.

Regarding sex, most participants were female (93.75%), while males comprised 6.25% of the group. As for race/skin color, we used the categorization by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in the questionnaire. Participants answered that they were white (62.5%), black (12.5%), mixed (25%), and there were no yellow or indigenous people. Regarding the country region they resided in, one could observe the predominance of participants from the Southeastern region (12 people), followed by the ones from the Northeast (2 participants), North (1 participant), and Argentina (1 participant). None of these participants declared being from the Southern or the Mid-Western regions. Regarding their school level, most participants were post-graduates, as it is possible to observe in Figure 1.5

Source: prepared by the authors.

Figure 1 - School level declared by educational professionals participating in the research.

By analyzing the abovementioned graph, one may verify that answers regarding the participants’ school level reveal that most of them continued their studies up until the post-graduate level, five with a specialization, and three with a master’s degree. Four participants had incomplete higher-level education, and four with complete higher-level education. From now on, we will present the results regarding the questions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the questionnaire, we used the Likert scale since it managed to provide the answers shown in Figure 2.

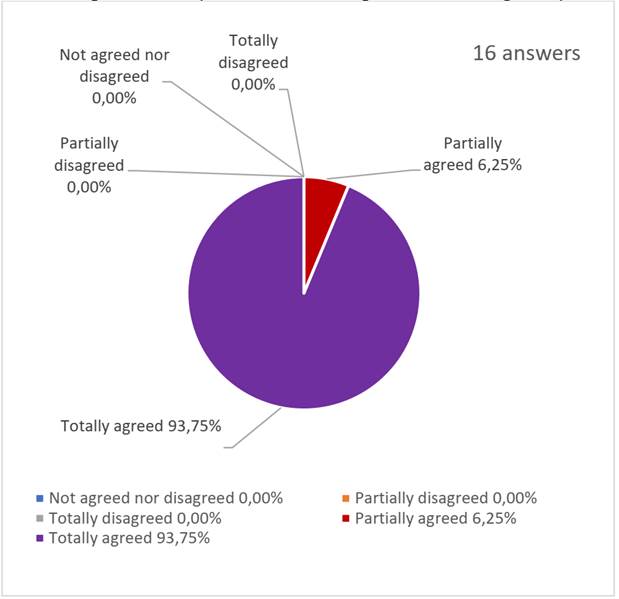

Source: prepared by the authors.

Figure 2 - “The situation presented by the COVID-19 pandemic changed my work/study routine.”

We observed that most participants had their routines changed somehow because of the pandemic: 93.75% of them answered “totally agreed,” while 6.25% answered “partially agreed.” We also questioned them on the change in their household income during the pandemic, obtaining the answers in Figure 3.

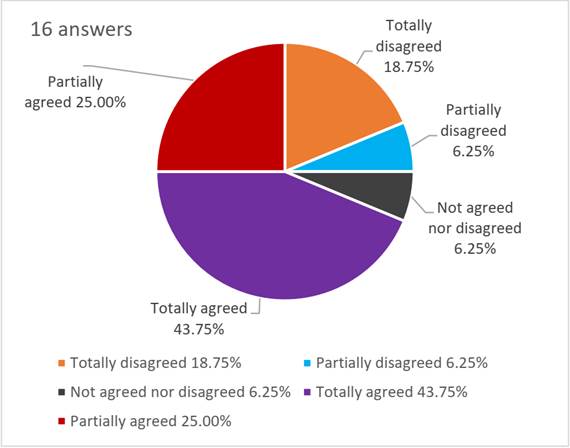

Source: prepared by the authors.

Figure 3 - “The situation presented by the COVID-19 pandemic changed my household income”

By analyzing Figures 2 and 3, one may note that the greater part of participants affirmed that there were changes in their work/study routines and family routines due to the pandemic. These pieces of data comply with the answers on the affirmation “The period of social distancing is affecting my socioemotional condition,” in which 56.25% of people answered that they totally agreed with it and 31.25% of them answered that they partially agreed, totalizing 87.5% of the participants. Since they were all educators, we also included in the questionnaire the affirmation “The period of social distancing is affecting my professional condition,” and we obtained 37.5% “Totally agreed” answers and 37.5% “Partially agreed” ones, totalizing 75%, the majority of them.

The questionnaire also counted with affirmations related to the content of the course of Dialogical Learning Formation. The greater part of educators in the group participating in the research answered that they knew what Dialogical Learning was, representing 68.75% of the total. As for knowledge of Teaching Communities, the percentage neared the previous one, representing 62.5% of people that already knew what it was. When questioned on their participation in any Successful Educational Action (SEA), we obtained, as well, a total of 62.5% of professionals from the field of teaching that answered positively. Still, when questioned if they put into practice any of the SEAs in their everyday professional routines, 43.7% of participants answered negatively, representing half of the group. As for the quality of the course, the questionnaire contained questions on methodological aspects, teaching material, virtual learning environment, synchronous meetings, etc. Of all participants, 93.75% positively rated all of the mentioned points on the quality of the course. Only 6.25% of them answered “Not agreed nor disagreed,” only in regards to the organization of the virtual learning environment. The main elements highlighted by the participants were the quality of the texts made available for reading and the educators’ organization, preparation, and attention. As for the affirmation “The course I engaged in (synchronous activities and virtual environment) has a great quality,” 100% of participants answered positively. Participants also answered questions concerning the relationship of the course with the act of facing the social distancing period. They have been questioned if the course helped them endure this period, as emphasized in Figure 4.

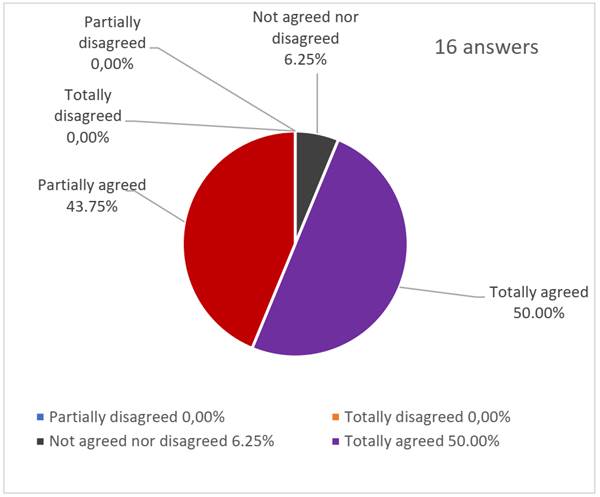

Source: prepared by the authors.

Figure 4 - “The course in which I am registered helped me endure the social distancing period”

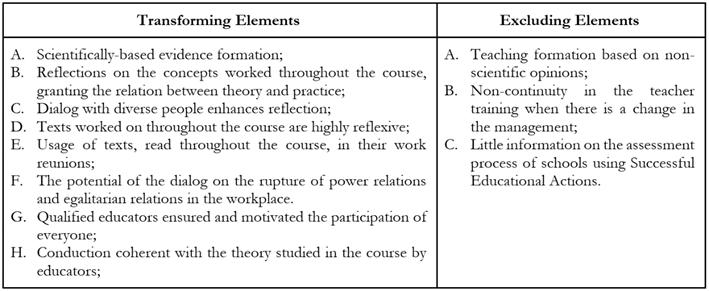

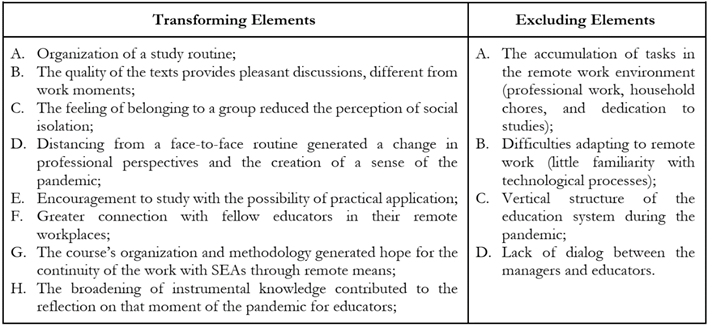

As it is possible to note in Figure 4, the majority of subjects (93.75%) answered that they agreed with the affirmation that the course contributed to them facing the social distancing period, i.e., 50% totally agreed, and 43.75% partially agreed. In addition to these closed questions in the Likert scale mode, we also made them open-ended questions, which allowed understand how the course impacted their theoretical and practical knowledge regarding their ability to face the social isolation period during the COVID-19 pandemic. For the analysis of open-ended questions, we used guidelines extracted from the Communicative Methodology (FLECHA, 2014; FLECHA, SOLER, 2014), which point to organizing participants’ answers by excluding elements and transforming elements. The participants’ answers were read and analyzed entirely, categorized by sense and/or meaning, in the face of presented knowledge of cultural order. Chart 1 presents the systematization of information in excluding and transforming elements of the concepts worked throughout the course.

Source: prepared by the authors.

Chart 1 - Transforming and excluding elements reported by the educators that engaged in the study from concepts worked throughout the course

In Chart 2, we present the systematics referring to the transforming and excluding elements that emerged from the participants’ answers and that are linked to the course’s capacity to help with facing the pandemic and social isolation.

Source: prepared by the authors.

Chart 2 - Transforming elements and excluding elements provided by the course for facing the pandemic and the social distancing period, reported by the educators who participated in the research.

Below, we present the discussion on the listed and presented data of this topic, considering the question that guides this study: What is the impact of the course of Dialogical Learning formation on the theoretical and practical knowledge of educators and its link with the endurance of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic?

DISCUSSION

In Brazil, in March 2020, educational institutions initiated the termination of activities from basic to higher level education. One year after the beginning of the pandemic caused by COVID-19, institutions that provide global-level educational support, such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) concerned about minimizing the negative effects caused by the distancing and the interruption of classes. At the beginning of 2021, more than half of the student population worldwide-800 million students-still had their classes paused at some level, which ranges from complete or partial closure of schools to reduction of the school workload, which affected 79 countries (UNESCO, 2021).

Reimers and Schleicher (2020) highlighted that the issue regarding the impact of the pandemic will include not only global public health but also the economy and the work environment, mainly in countries with a high social vulnerability index. This impact also touches education, given that measures of social isolation and distancing made educators and students move away from their regular educational activities, reducing time and learning opportunities.

As a form of educational response for this period, the report prepared by Reimers and Schleicher (2020) for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) points to the need to establish working groups, virtual media for teachers and students, and emergency continuing education mechanisms in the context of the pandemic. The report also brought data from interviews with educational organizations worldwide on how countries had articulated themselves on the facing of adversities that emerged from this context and the numerous variables that influence the performance of educational activities. Data reveal that the major educational worry of countries was linked to granting continued academic learning for students and offering ongoing formation for educators. Furthermore, data also reveal that the pandemic positively contributed to the introduction of technologies and innovative solutions for the educational field, as well as the development of students’ autonomy concerning their studies and greater educators’ autonomy.

In this article, we analyze the impact of Dialogical Teaching Formation, focusing on the theoretical and practical knowledge of educators and its linking with facing social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. We presented the participants’ characterization, which is greatly composed of women, very similar data to the last School Census (2020), which indicates that 81% of working teachers in basic Brazilian education were female. Below, we present a deepened analysis of Charts 1 and 2, which have already been shown and that highlight transforming and excluding elements that emerged from the forms, interviews, and focused group dynamics carried out with participants, all based on the theoretical referential of Dialogical Learning.

As for the formation of all educators that engaged with the research, half continued their studies throughout higher level education in post-graduation courses, including attaining specializations and master’s degrees. We also highlight that the diversity of existing contexts surrounding participants inserted in the group, such as the degree of their education, the regions they live/work, and their professional performances, were ranked as transforming elements (Chart 1, transforming element F). Data also show that the pandemic impacted educators’ lives, from their work routines (Figure 2) to their household incomes (Figure 3). These data show the lack of stability of the pandemic moment in which we are inserted, something that can relevantly impact the life of people on a psychological bias. The international study classifies this psychological impact from moderate to severe during the initial stage of the pandemic due to social isolation, with expressive results in China (WANG et al., 2020), Spain, (GONZÁLEZ-SANGUINO et al., 2020) and also in Germany (BENKE et al., 2020). Other studies, in addition, highlight the worsening of social vulnerabilities in this context, such as in Spain (REDONDO-SAMA et al., 2020), the United States (GAYNOR; WILSON, 2020), and Bangladesh (SAKAMOTO; BEGUM; AHMED, 2020).

The necessity of social isolation and remote work generated consequences for the group participating in the research as for the way they understood and organized their work and household routines (Cahrt 2 - excluding elements A and B), the information provided by these subjects at the electronic forms and their reports:

[...] My constant exposition to violence and the lonely state during the isolation, the constant exposition to the indexes of violence, collaborated with the worsening of my psychological state. (Participant’s report)

[...] The enormous quantity of work that emerged, not that I didn’t already have a lot of work, but it seems like, due to the isolation, the workload tripled in size for those not accustomed to working from home, which is my case. (Participant’s report)

[...] The workload tripled in size, and despite we tried to establish a routine, it was quite hard, actually, it was almost pointless, due to the work’s requirements themselves. It seems that those who are above one [managers] do not consider that one is indeed working, but, in fact, taking advantage of the situation because they are home. (Participant’s report)

One of the most highlighted points among the participants’ answers is the Instrumental Dimension identified in Chart 1 - transforming elements A, B, C, D, E. and G, and Chart 2 - transforming elements E and H. The educators emphasized, above all, the quality of texts and professionals that conducted the course. In Dialogical Learning theory, the principle of instrumental dimension is linked to the necessity of access and learning of scholar/academic content for the suppression of inequalities and social promotion, focusing on outcome equality, in compliance with ideas retrieved from international research (AUBERT et al., 2016; BALL, 2012; APPLE; BEANE, 1997; LADSON-BILLINGS, 1995).

In the teacher training, the Instrumental Dimension is increasingly important, mainly during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which we observed, in educational environments, the rise of the discourse promoting well-being due to school contents, reducing the social function of the school and the work quality of the educator. In this sense, we agree with Aubert et al. (2016), who stated that there is no more space for superstitious ideas in the society of information, since science, as well as technology, allow us to access international, public content and show us academical results from different parts of the world.

Thus, the development of research abilities fundamentally contributes to the acquirement of instrumental knowledge (AUBERT et al., 2016), mainly in the teacher training, as indicated by Freire (2015) when emphasizing that being an educator requires research and epistemological rigor for ensuring correct thinking. According to Freire (2015), these factors contribute to the formation of people that transform their naïve curiosity into an epistemological one, capable of altering their realities and producing knowledge. Therefore, the scientific teacher training becomes crucial for surpassing inequalities in education during the 21st century, given that, in addition to having access to theories and practices that promote educational improvement, professors also find motivation for the exercise of their profession.

The participants of this research emphasize the importance of the quality of the texts studied throughout the course, linking deepened reflection to the possibility of overcoming the pandemic and ensuring social transformation.

[...] I used numerous ones [texts] that I really absorbed and worked with conjoint with educators. Sharing with them these changes in regards to our context, related to both the educator and the student, but with the help of all this technology... And not only stay still thinking that “the student does not want to know and is not doing the task,” which was something consistent. (Participant’s report)

Then, when I saw that your proposal was the one being applied to this course and text, all of this scientific, theoretical, and practical support, realizing that it worked, I realized “Wow, this is what I want for my life!”... For us to really transform society into something more fair and egalitarian for everyone. (Participant’s report)

The work with scientific evidence was also emphasized by participants as something intimately linked to the Instrumental Dimension principle on the teacher training, as numerous reports of subjects of this research reveal in Chart 1 - transforming element A and Chart 2 - transforming element E. Contact with these relevant texts on the international scientific community, since it presents practical results, amplify knowledge and enables it to educators to safely use in their everyday routines.

[...] What happens is that various things related to good practice come to us, but, actually, most of the time, they are just pointless, you know? Then, you come and show us: “No, a good practice isn’t everything, it has to be scientifically based, it has to be proven,” and not only that it turned out right, but that it was investigated, was launched and used somewhere, there’s an article that supports it, and not only a school group that produced a poster about it and that’s all. (Participant’s report)

[...] When these actions solidify themselves in practice, we realize that it is indeed important to be backed by theory and how Dialogical Learning does it right by bringing all this theoretical support, scientific method, and proof... But why was it proven? Because it really was proven, if it was successful or not... So, we have the data. (Participant’s report)

When educators’ initial and ongoing formation is based on scientific evidence, one can note that there is a theoretical deepening that promotes a deepened analysis of the practice. The debate on teaching and learning must be free from individual opinions, therefore avoiding verbalism, which is characterized by a theory with no practice and activism, resulting from practice with no theory (FREIRE, 2015). Otherwise, the result may bring irrecoverable losses to the teacher training and students at all levels of teaching.

In search of the praxis (FREIRE, 2004, 2015), theory, and practice that create and modify reality, we understand that the teacher training that is based on scientific evidence arms all people from the school community (educators, students, managers, relatives, etc.) for understanding and assessing teaching practices. This process generates autonomy in decision-making to benefit students with the best education possible.

It is noteworthy to compare this data with what Ball (2012) stated, who signals the existence of a gap in the teacher training related to research and who defends that for their practices to give place to results and transformation should be based on scientific evidence. In addition, the author also defends the necessity that this formation should be spread to other contexts in the form of knowledge communities for the dialog between related people and the international scientific community to reach those who formulate public policies.

We agree with Ball (2012) on the scientific deepening and knowledge communities, as well as with Ladson-Billings (1995, 2021) when it comes to culturally relevant teaching since they directly dialog with the principle of Sense Creation supported by the theory in Dialogical Learning. Creation of sense incorporates cultural and linguistic differences within environments of school and educators’ formation. Thus, one creates sense when people in communicative interaction surround one through an intersubjective, dialogical relationship. In our research, educators reported the importance of participating in a study based on the Dialogical Teaching Workshop, which is supported by this communicative interaction as shown in Chart 2 - transforming elements C, H, and F. Some reports of participants emphasize the communicative interaction and sense creation as answers for the pandemic context.

[...] We see how knowledge is supported by this Dialogical Learning. We also see how practice and theory are intertwined. So this is important, we see how there is no distancing, but nearing since one needs another, and depends on another, they are associated together. (Participant’s report)

And, from the moment we have all of this theoretical framework within us, the sense is an inevitable result of practice since authors were committed to proposing their meanings, right? So we realize there are clarity surrounding authors. This is why it is important to do it in a group, since, alone, I will only be able to gather what is intertwined with my experiences [...] (Participant’s report)

We also highlight, in Chart 2 - transforming element D, the potential of reflection on professional perspectives and the creation of sense caused by the distance set from face-to-face routines, as well as the recognition of the importance of partnerships established between community and school, as it is emphasized on the following report.

[...] There was a distancing from the [face-to-face] routine and it was important, since, when one distances oneself from the subject, I think it is easier to try and see what is doing right and isn’t regarding the matter... [The pandemic] made people look away from their perspectives and stare at family points of view... The pandemic was necessary, as well as distancing, for people to know a little bit more about that community. The community felt the absence of school, and the school felt the necessity of this more effective partnership, right? So, I think that, in this sense, if there is something to be won, I believe we can see it from other perspectives. (Participant’s report)

When we refer to the context prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic and to the extent education was impacted by its closure, we question which schools suffered the most and to what context they belong. By bringing back the study by Reimers and Schleicher (2020) to the OECD, it is possible to note that the authors state that, worldwide, students from the disadvantaged background were the most affected by the pandemic context since, in addition not to having access to the Internet, they also did not have a proper place to study. The same happened with educators, who could not access the Internet or connect with their students within this context. In the abovementioned study, authors also affirmed that students, schools, and educators who belong to a favorable social context managed to rapidly organize themselves in a way to ensure attending to the new educational demands,

In this light, the organization of school contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic emphasized that schools and people that are economically favored suffered less impact with the migration of their activities toward remote means. Data collected in our research revealed concern with the vertical structure of the school management, in which there is little dialog, a factor that promoted greater distancing between professionals, as pointed out in Chart 1, excluding element B and Chart 2 - excluding elements C and D.

[...] Relationships, especially those set by the school office, are not horizontal, they are vertical. With this COVID-19 pandemic situation, it is extremely stressful not to have the involvement of professors. They came up with a scheme that cancels us out, that is, from the guidance team, we are the last ones to know about things. (Participant’s report)

I see today that many of the continued formations set in cities just want to comply with what was really set, but do not want a change, a transformation. We do not get to see those wishes, do you understand? It is senseless and does not help us attach a new meaning to it. (Participant’s report)

[...] Unfortunately, somethings things happen too quickly, isn’t it? It seems like as soon as you are starting something, something else comes along and you have to direct your attention to it as soon as possible. There is no beginning, middle, or end, it is always in the middle, and it is always running and starting anew. (Participant’s report)

[...] Here, and I suppose that there with you, too, there is a very pyramidal structure in some teaching levels that are beyond the school’s control regarding a project: there is a structure that is set by a supervisor. (Participant’s report, our translation)

Still, we highlight that the transforming elements were bigger than the excluding ones from the participants’ answers. Many reports contain the principle of transformation and solidarity (AUBERT et al., 2016) within interactions obtained throughout the course. When the participant educators report that they took the texts to their work contexts to dialog with their coworkers on the course of the content or that they wish to initiate study groups with their fellow pairs, they demonstrate the intention and wish to transform “difficulties into possibilities” (AUBERT et al., 2016, p. 165), therefore providing practical responses for issues faced. Supportive professors that adopt a radical behavior (FREIRE, 2015) denounce inequalities and the malfunctioning of school structures but also think and act to transform these contexts.

Returning to the introductory notes of this article and the data present, it is possible to note that the Instrumental Dimension principle is intimately connected with the Creation Sense. Scientific texts throughout the course provided the necessary link for professors to feel capable of finding practical responses to their problems.

FINAL REMARKS

In this article, we analyzed the impact of the Dialogical Learning Formation course on educators’ theoretical and practical knowledge and its relations with the capacity to endure social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis revealed important transforming elements for the teacher training, mainly focusing on the instrumental dimension and sense creation, surrounded by the importance of scientific evidence when facing and transforming professional and individual contexts. Our findings showed that the impact of the course on the educators occurred mainly through the learning of contents about Dialogical Learning and how to use them in the workplace. Since it was carried out remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was also an impact on the solidarity feeling of each participant, for they nourished the feeling of belonging to a group, a positive way of facing social isolation.

However, as pointed out in Charts 1 and 2, the accumulation and excess of work, the lack of familiarity with technology, the teacher training based on non-scientific data, the vertical structure, and the lack of dialog with school management emerged from the participants’ answers as excluding elements. These abovementioned elements were contemplated in discussions carried out throughout this article on how the COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted the lives of the majority of participants (around 80%) in numerous aspects (e.g., emotional, social, and economic).

Transforming elements presented in both the Results and the Discussion sections point to the fact that the Dialogical Teaching Formation course relevantly contributed to the facing of social distancing and the difficulties raised during the pandemic period. They support the course’s organization, quality of the texts, theoretical deepening, and scientific basis as important themes for the formation, which can transform difficulties into real possibilities in the performance in professional contexts.

The diversity in the group enabled a solidarity feeling and a sense of creation in participants through egalitarian dialog through virtual learning environments, therefore demonstrating the effectiveness of already existing scientific evidence on the SEAa, especially the Dialogical Teaching Workshop. In times where it is possible to note the constant presence of fake news, we emphasize the necessity of scientific-based educator formation for all people to have access to better knowledge, with the possibility of social and educational transformation. We consider that the Dialogical Teaching Formation, aligned with theoretical knowledge supported by Dialogical Learning, and studies of the international scientific community, which presents practical, effective results, contributed to the surpassing of professional and emotional difficulties caused by social distancing during the pandemic. Additionally, data reveal that the course offered conceptual and practical instruments for the participating educators to apply the SEA principles studied throughout the study.

By analyzing transforming and excluding elements, we consider it important to say that answers and actions for the problems faced during the pandemic, reported by the participants, did not come from the system but from the world of life (HABERMAS, 2012). Lastly, we emphasize that Dialogical Learning is a potential, transforming tool that can promote a critical and freer education for everyone. As demonstrated by the study by Silva, Braga, and Mello (2021), this focus highlights that the teacher training needs to be aligned with scientific evidence not only in contexts of difficulty, as is the one surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, but a permanent formation that integrates that international scientific community.

REFERENCES

AIELLO, Emília et al. Effective strategies that enhance the social impact of social sciences and humanities research. Evidence & Policy, [S. l.], v. 18, n. 1, 2020. <https://doi.org/10.1332/174426420X15834126054137> [ Links ]

ÁLVAREZ, Luis Fernando C. Intercultural communicative competence: in-service efl teachers building understanding through study. Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, [S. l.], v. 22, n. 1, p. 75-92, 2020. <https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v22n1.76796> [ Links ]

APPLE, Michael W.; BEANE, James A. Escuelas democráticas. Madri: Morata, 1997. [ Links ]

AUBERT, Adriana et al. Aprendizagem Dialógica na Sociedade da Informação. São Carlos: EdUFSCar, 2016. [ Links ]

BALL, Arnetha F. To know is not enough: knowledge, power, and the zone of generativity. Educational Researcher, [S. l.], v. 41, n. 8, p. 283-293, 2012. <https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12465334> [ Links ]

BARDIN, Laurence. Análise de Conteúdo. São Paulo: Edições 70, 2011. [ Links ]

BARROS-DEL RIO, Maria A.; ÁLVAREZ, Pilar; MOLINA ROLDÁN, Silvia. Implementing Dialogic Gatherings in TESOL teacher education. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, [S. l.], v. 15, n. 2, p. 169-180, 2021. <https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2020.1737075> [ Links ]

BENKE, Christoph et al. Lockdown, quarantine measures, and social distancing: Associations with depression, anxiety and distress at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic among adults from Germany. Psychiatry Research, [S. l.], v. 293, n. 113462, 18 set. 2020. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113462> [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Portaria n. 329, de 11 de março de 2020. Institui o Comitê Operativo de Emergência do Ministério da Educação - COE/MEC. Diário Oficial da União: ed. 49, seção 1, Brasília, DF, 12 mar. 2020a. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-n-329-de-11-de-marco-de-2020-247539570 >. Acesso em: 10/11/2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Portaria n. 343, de 17 de março de 2020. Dispõe sobre a substituição de aulas presenciais por aulas em meios digitais enquanto durar a situação de pandemia do Novo Coronavírus - COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União: ed. 53, seção 1, Brasília, DF, 18 mar. 2020b. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-n-343-de-17-de-marco-de-2020-248564376 >. Acesso em:10/11/2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Súmula do Parecer CNE/CP n. 5/2020. Reorganização do Calendário Escolar e da possibilidade de cômputo de atividades não presenciais para fins de cumprimento da carga horária mínima anual, em razão da Pandemia da COVID-19. Diário Oficial da União: ed. 83, seção 1, Brasília, DF, 4 maio 2020c. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/sumula-do-parecer-cne/cp-n-5/2020-254924735 >. Acesso em:10/11/2020. [ Links ]

CORDINGLEY, Philippa. The contribution of research to teachers’ professional learning and development. Oxford Review of Education, [S. l.], v. 41, n. 2, p. 234-252, 2015. <https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2015.1020105> [ Links ]

CREA. Relatório INCLUD-ED Final: Estratégias para a inclusão e coesão social na Europa a partir da educação. Barcelona: Universidade de Barcelona, 2012. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.comunidadedeaprendizagem.com/uploads/materials/12/740922c2359d3ca752de853bbb798930.pdf >. Acesso em:10/12/2020. [ Links ]

CRESWELL, Jhon W. Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. 4th ed. Boston: Pearson, 2012. [ Links ]

DESIMONE, Laura M. Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Toward Better Conceptualizations and Measures. Educational Researcher, [S. l.], v. 38, n. 3, p. 181-199, 2009. <https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140> [ Links ]

DOWNER, Jason T. et al. Teacher Characteristics Associated With Responsiveness and Exposure to Consultation and Online Professional Development Resources. Early Education and Development, [S. l.], v. 20, n. 3, p. 431-455, 2009. <https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280802688626> [ Links ]

FELDMAN, Allan; OZALP, Dilek. Science teacher's ability to self-calibrate and the trustworthiness of their self-reporting. Journal of Science Teacher Education, [S. l.], v. 30, n. 3, p. 280-299, 2019. <https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2018.1560209> [ Links ]

FLECHA, Ramón. Compartiendo palabras: el aprendizaje de las personas adultas a través del diálogo. Barcelona: Paidós, 1998. [ Links ]

FLECHA, Ramón. Using Mixed Methods From a Communicative Orientation: Researching With Grassroots Roma. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, [S. l.], v. 8, n. 3, p. 245-254, 2014. <https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689814527945> [ Links ]

FLECHA, Ramón; BUSLON, Nataly. 50 años después del Informe Coleman. Las actuaciones educativas de éxito sí mejoran los resultados académicos. International Journal of Sociology of Education, [S. l.], v. 5, n. 2, p. 127-143, 2016. <https://doi.org/10.17583/rise.2016.2087> [ Links ]

FLECHA, Ramón; SOLER, Marta. Communicative Methodology: Successful Actions and Dialogic Politics. Current Sociology, [S. l.], v. 62, n. 2, p. 232-242, 2014. <https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392113515141> [ Links ]

FOX, Rebecca K. et al. Investigating advanced professional learning of early career and experienced teachers through program portfolios. European Journal of Teacher Education, [S. l.], v. 38, n. 2, p. 154-179, 2015. <https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2015.1022647> [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. 50. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2015. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia do Oprimido. 38. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 2004. [ Links ]

GARCÍA-CARRIÓN, Rocío et al. Implications for Social Impact of Dialogic Teaching and Learning. Frontiers in Psychology, [S. l.], v. 11, 05 fev. 2020. <https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00140> [ Links ]

GAYNOR, Tia Sherèe; WILSON, Meghan E. Social vulnerability and equity: the disproportionate impact of COVID-19. Public Administration Review, [S. l.], v. 80, p. 832-838, 2020. <https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13264> [ Links ]

GÓMEZ, Aitor; PUIGVERT, Lídia; FLECHA, Ramón. Critical communicative methodology: Informing real social transformation through research. Qualitative Inquiry, [S. l.], v. 17, n. 3,2011 p. 235-245, 20 doi: 10.1177/1077800410397802. [ Links ]

GÓMEZ, Jesus et al. Metodologia Comunicativa Crítica. Barcelona: El Roure, 2006. [ Links ]

GONZÁLEZ-SANGUINO, Clara et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, Behavior and Immunity, [S. l.], v. 87, p. 172-176, jul. 2020. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040> [ Links ]

GREENLEAF, Cynthia L.; LITMAN, Cindy; MARPLE, Stacy. The impact of inquiry-based professional development on teachers’ capacity to integrate literacy instruction in secondary subject areas. Teaching and Teacher Education, [S. l.], v. 71, p. 226-240, 2018. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.01.006> [ Links ]

HABERMAS, Jürgen. Teoria do Agir Comunicativo: sobre a crítica da razão funcionalista. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2012. [ Links ]

HIGGINS, Joanna; PARSONS, Ro. A successful professional development model in mathematics: a system-wide New Zealand case. Journal of Teacher Education, [S. l.], v. 60, n. 3, p. 231-242, 2009. <https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109336894> [ Links ]

JUKES, Matthew C. H. et al. Improving literacy instruction in Kenya through teacher professional development and text messages support: a cluster randomized trial. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, [S. l.], v. 10, n. 3, p. 449-481, 2017. <https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2016.1221487> [ Links ]

KUTAKA, Tracy S. et al. Connecting teacher professional development and student mathematics achievement: a 4-year study of an elementary mathematics specialist program. Journal of Teacher Education, [S. l.], v. 68, n. 2, p. 140-154, 2017. <https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116687551> [ Links ]

LADSON-BILLINGS, Gloria. But that's just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into Practice, [S. l.], v. 34, n. 3, p. 159-165, 1995. <https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849509543675> [ Links ]

LADSON-BILLINGS, Gloria. Three decades of culturally relevant, responsive, & sustaining pedagogy: what lies ahead? The Educational Forum, [S. l.], v. 85, n. 4, p. 351-354, 2021. <https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2021.1957632> [ Links ]

NAEGHEL, Jessie et al. Promoting elementary school students' autonomous reading motivation: effects of a teacher professional development workshop. The Journal of Educational Research, [S. l.], v. 109, n. 3, p. 232-252, 2016. < https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.942032> [ Links ]

ORAMAS, Alfonso Rodríguez; FLECHA, Ramón. Resgatando o sentido da profissão docente por meio de tertúlias pedagógicas dialógicas: vozes de professores da Serra Norte do México. Articulando e Construindo Saberes, [S. l.], v. 6, 2021. <https://doi.org/10.5216/racs.v6.67742> [ Links ]

PENUEL, William R. et al. What Makes Professional Development Effective? Strategies That Foster Curriculum Implementation. American Educational Research Journal, [S. l.], v. 44, n. 4, p. 921-958, 2007. <https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207308221> [ Links ]

PIANTA, Robert C. et al. Effects of web-mediated professional development resources on teacher-child interactions in pre-kindergarten classrooms. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, [S. l.], v. 23, n. 4, p. 431-451, 2008. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.02.001> [ Links ]

REDONDO-SAMA, Gisela et al. Social Work during the COVID-19 crisis: responding to urgent social needs. Sustainability, [S. l.], v. 20, n. 12, 2020. <https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208595> [ Links ]

REIMERS, Fernando M.; SCHLEICHER, Andreas. A framework to guide an education response to the COVID-19 Pandemic of 2020. [S. l.]: OECD, 2020. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.aforges.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/framework.pdf >. Acesso em:02/09/2021. [ Links ]

ROCA CAMPOS, Esther; GÓMEZ, Aitor; BURGUÉS, Ana. Luisa, Transforming Personal Visions to Ensure Better Education for All Children. Qualitative Inquiry, [S. l.], v. 21, n. 10, p. 843-850, 2015. <https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800415614026> [ Links ]

RODRÍGUEZ-ORAMAS, Alfonso et al. Dialogue with educators to assess the impact of dialogic teacher training for a zero-violence climate in a nursery school. Qualitative Inquiry, [S. l.], v. 26, n. 8-9, p. 1019-1025, 2020. <https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420938883> [ Links ]

SAKAMOTO, Maiko; BEGUM, Salma; AHMED, Tofayle 1. Vulnerabilities to COVID-19 in Bangladesh and a Reconsideration of Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability, [S. l.], v. 13, n. 12, 2020. <https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135296> [ Links ]

SHONKOFF, Jack P. Stress, resilience, and the role of science: responding to the coronavirus pandemic. Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 20 mar. 2020. Disponível em: <https://developingchild.harvard.edu/stress-resilience-and-the-role-of-science-responding-to-the-coronavirus-pandemic>. Acesso em:03/01/2021. [ Links ]

SILVA, Alexandre R. N.; BRAGA, Fabiana M.; MELLO, Roseli R. Formação pedagógica em aprendizagem dialógica em tempos de distanciamento social. Revista Humanidades & Inovação, [S. l.], v. 8, n. 40, p. 252-267. 2021. Disponível em: <https://revista.unitins.br/index.php/humanidadeseinovacao/article/view/5102>. Acesso em:10/09/2021. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Adverse consequences of school closures. COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response. Education Sector issue notes, Paris, 2020b. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/consequences >. Acesso em:04/01/2021. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Dados da UNESCO mostram que, em média, dois terços de um ano acadêmico foram perdidos em todo o mundo devido ao fechamento das escolas devido à COVID-19. UNESCO COVID-19 Education Response. Education Sector issue notes, Paris, 25 jan. 2021. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://pt.unesco.org/news/dados-da-unesco-mostram-que-em-media-dois-tercos-um-ano-academico-foram-perdidos-em-todo-o >. Acesso em:10/12/2021. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Distance learning strategies in response to COVID-19 school closures. Nota informative, Paris, n. 2.1, p. 1-8, 2020a. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373305_por >. Acesso em:22/11/2020. [ Links ]

WANG, Cuiyan et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, [S. l.], v. 17, n. 5, p. 1-25, 2020. <https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729> [ Links ]

1The translation of this article into English was funded by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais - FAPEMIG, through the program of supporting the publication of institutional scientific journals.

2INCLUDE-ED (2006-2011) presented seven SEAa: Dialogical Teaching Workshop, Interactive Group, Tutored Library, Relatives’ Formation, Educational Participation of the Community, Dialogical Model of Preventing Conflicts, and Dialogical Teaching Formation. For more information on them, refer to Aubert et al. (2016) and Mello, Braga, and Gabassa (2020).

3More detail on the course can be found at https://www.proex.ufscar.br/aciepes, by clicking on the 2020 extra period option and selecting the title “Tertúlias pedagógicas: formação em aprendizagem dialógica”.

4Moodle System, which provided the virtual environment of learning, and Google Meet, in which synchronous meetings were carried out.

5Listed in the graph, there are only the answers from participants belonging to the focus of professionals from the educational field. Alternative options present in the questionnaire were as follows: Incomplete elementary school, complete elementary school, incomplete high school, complete high school, incomplete technical/professionalizing high school, complete technical/professionalizing high school, incomplete higher level education, complete higher level education, specialization, master’s degree, doctorate.

Received: December 27, 2021; Accepted: July 29, 2022

texto en

texto en