Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.39 Belo Horizonte 2023 Epub 10-Jul-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469841688

Relacionado con: https://preprints.scielo.org/index.php/scielo/preprint/view/4939

ARTIGO

MEDIATIC-VISUAL LITERACY: A HUMAN RIGHT AT SCHOOL

1Universidade Feevale. Novo Hamburgo, Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Brasil.

2Universidade Feevale. Novo Hamburgo, Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Brasil.

3 Senac de Uruguaiana. Uruguaiana, Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Brasil.

This study is about the relation among media culture and school territory, problematizing the role of the teacher and the school in the mediation of contents mediatically consumed by the students. The investigation debates the understandings and skills that the teachers possess in relation to the didactics turned to Mediatic-Visual Literacy inside their specific school contexts. In methodological terms, has a quantitative-qualitative approach, which central strategy is the action-research (THIOLLENT, 1986). To achieve that, are theoretically-methodologically articulated some concepts, such as: Human Rights (MARTÍN-BARBERO, 2011); Visual Literacy (KELLNER, 1995) and Media Education (BACCEGA, 2001). These notions oriented the empiric research developed with a teachers’ group from the municipal network of teaching in a town of Rio Grande do Sul/Brazil. The work comes from an investigative process of introductory poll, followed by a focal approach. Among the results of the research-action, it was verified with the teachers the absence of a support for the work with media images mechanism and systems, generating insecurities. However, in the intervention accomplished among a small number of teachers, it was possible to give another meaning to some of these fears, presenting other perspectives and offering new thoughts. There was, yet, the joint construction of knowledges, making other looks possible for the critical consumption of media manifestations and the importance of the conscious use of technologies. It’s particularly highlighted the creation of the Guide to Mediatic-Visual Literacy, a document oriented on the study and in the use of photographic language at school, believing that, as this research, will be possible to give opportunity for new ways of thinking and planning the processes of teaching-learning, also making possible to the educators and students the construction of knowledge that enable a more conscious and critic consumption of communicational artifacts, as well as more autonomy and responsibility to use the media technologies as a way of democratic fight and citizen expression.

Keywords: photography; media; education; human rights

O estudo versa sobre a relação entre a cultura da mídia e o território escolar, colocando em debate as compreensões e aptidões que os/as docentes possuem em relação às didáticas voltadas para a Alfabetização Midiática-Visual dentro de seus contextos escolares de atuação. Em termos metodológicos, trata-se de uma abordagem quanti-qualitativa, que tem como estratégia central a pesquisa-ação (THIOLLENT, 1986). Para isso, articula-se teórico-metodologicamente através de alguns conceitos, tais como: Direitos Humanos (MARTIN-BARBERO, 2011), Alfabetismo Visual (KELLNER, 1995) e Educação Midiática (BACCEGA, 2001). Noções essas que nortearam a pesquisa empírica desenvolvida com um grupo de docentes da rede municipal de uma cidade no Rio Grande do Sul/Brasil. O trabalho é oriundo de um processo investigativo de sondagem introdutória, que seguiu com uma abordagem focal. Entre os resultados da pesquisa-ação, verificou-se nos/as professores/as uma ausência de amparo no que se refere ao trabalho com mecanismos e sistemas de imagens midiáticas, ocasionando inseguranças. Contudo, na intervenção realizada junto a um número reduzido de pedagogos/as, foi possível ressignificar alguns desses temores, apresentando outras perspectivas e proporcionando reflexões. Houve, ainda, a construção conjunta de saberes, viabilizando outros olhares quanto ao consumo crítico das manifestações midiáticas e à importância do uso consciente das tecnologias. Destaca-se particularmente a criação do Guia da Alfabetização Midiática-Visual, documento pautado no estudo e no uso da linguagem fotográfica na escola, o qual acredita-se, assim como esta pesquisa, que oportunize novas formas de se pensar e planejar os processos de ensino-aprendizagem.

Palavras-chave: fotografia; mídia; educação; direitos humanos

El estudio trata de la relación entre la cultura de los medios y el territorio escolar, problematizando el papel del/de la maestro/a y de la escuela en la mediación de los contenidos mediáticamente consumidos por los/las estudiantes. La investigación pone en discusión las comprensiones y aptitudes que los/las docentes poseen en relación a las didácticas que se vuelven a la Alfabetización Mediática-Visual dentro de sus específicos contextos escolares de actuación. En términos metodológicos, tratase de un abordaje cuanti-cualitativo, que tiene como estrategia central la investigación-acción (THIOLLENT, 1986). Para eso, articulase teorico-metodologicamente a través de algunos conceptos, como: Derechos Humanos (MARTÍN-BARBERO, 2011), Alfabetismo Visual (KELLNER, 1995) y Educación Mediática (BACCEGA, 2001). Nociones esas que orientaron la investigación empírica desarrollada con un grupo de docentes de la red municipal de una ciudad en Rio Grande do Sul/Brasil. El trabajo parte de un proceso investigativo de encuesta introductoria, seguida por un abordaje focal. Entre los resultados de la investigación-acción, fue verificado en los/as maestros/as una ausencia de amparo en lo que se refiere al trabajo con mecanismos y sistemas de imágenes mediáticas, ocasionando inseguridades. A pesar de eso, en la intervención hecha junto a un número reducido de pedagogos/as, fue posible resignificar algunos de esos temores, presentando otras perspectivas y proporcionando reflexiones. Hubo, aún, la construcción conjunta de saberes, viabilizando otras miradas cuanto al consumo crítico de las manifestaciones mediáticas y la importancia de la utilización consciente de las tecnologías. Se destaca particularmente la creación del Guía de la Alfabetización Mediática-Visual, un documento orientado en el estudio y en el uso del lenguaje fotográfico en la escuela, lo cual se cree, así como esta investigación, que pueda dar oportunidad de nuevas maneras de pensar y planear los procesos de enseñanza-aprendizaje, además de propiciar a los/las educadores/as y a los educandos/as la construcción de saberes con los cuales se pueda ejercer más autonomía y responsabilidad en el uso de las tecnologías mediáticas como forma de lucha democrática y expresividad ciudadana.

Palabras clave: fotografía; medios; educación; derechos humanos

INTRODUCTION

Freedom to act and express an opinion, as well as the ability to interpret and produce forms of communication, are, and always will be, a human right that can also be ensured by education. Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), for example, states that "everyone has the right to education", ratifying in its enunciation an education aimed at the "full expansion of the human personality" and the duty to act in favour of the "human rights and fundamental freedoms" of the population (UN, 1948). It is understood, from such perspective, that the functions operationalized by education, which has its attributions legitimized and assessed by the State through the school institutions, need to be constantly rethought in the world in continuous transformation, given that the "educational practice that, historical, cannot be alien to the concrete conditions of the time-space in which it takes place" (FREIRE, 2016, p. 86), if it wants to continue providing society with the necessary skills for its individuals to achieve independence and dignity of existence.

Therefore, a school directed to the construction of citizenship is a school that needs to be open and integrated to the new "informational and communicative ecosystem" (MARTIN-BARBERO, 2011, p. 133), by considering that the media and the new communicational codes are intrinsically linked to the way of life and exercise the rights of being a citizen in contemporary times. Therefore, providing an education disconnected from the sociocultural conditions on which the existential reality of the subjects takes place is to hurt and neglect what is agreed in the UDHR.

Several sectors of society are reflecting on the development of this media culture, which is constantly growing and evolving. One example is the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which warns of the need to reflect on the importance of increasing pedagogical practices focused on the study of media, by identifying a more critical and active attitude in relation to the technological and communication tools that constitute the present time. Therefore, there are already numerous guidelines, official statements and documents that question the current challenges and commitments of education within this new reality of life (SOUSA, 2019).

Consequences of these movements can already be observed in Brazil, among which stands out the redesign of the Common National Curricular Base ("Base Nacional Comum Curricular" - BNCC) for the contemporary demands of teaching. In 2017, significant changes were made in the ways of thinking and guiding Basic Education in Brazil, and, in the core of these changes, there are recommendations focused on Media Education and Visual Literacy. From this perspective, it is possible to identify, among the general skills set out in the document, the understanding that schools today need to be open to the "different languages" that constitute the particular daily lives of students, so that they can "express themselves and share information, experiences, ideas and feelings" in the varied dynamics of teaching, in addition to undertake exercises that lead to the use and understanding of "digital technologies of information and communication", in order to guide to a "critical, meaningful, reflective and ethical" attitude before these communicative tools, so that they can exercise more " prominence and authorship in personal and collective life” (BRASIL, 2018, p. 9).

Therefore, within the scope of these discussions, it is necessary to delimit some notions. It is emphasized that this research assumes Visual Literacy as a dimension of performance of Media Education itself, being a significant stage involving this formative process. Its goal, therefore, is not other or below the Media Education, it only proposes to perceive the media through a more specific look to the image productions that, equally, constitute this communicative universe. In this way, a Visual Literacy, in the perspective of Media Education, seeks to teach how to produce and interpret what is exposed beyond the spoken and written word, with the intention of enabling the subjects to engage more consciously and effectively with the visual discourses that transit through the media, carrying skills to read and decipher the many ideological intentions that daily interpellated and affect life (KELLNER, 1995; BACCEGA, 2001; SOARES, 2014).

Hence, considering that Media Education and Visual Literacy present theoretical conceptions that complement each other in the definition of a certain way of thinking and acting - since an educate for the media involves sight and literacy for images -, this study chooses to conduct its investigation on the subject based on the two conceptions, which were called Media-Visual Literacy. The term literacy was chosen because it refers to the beginning of a learning system that is "linked to the state of the individual that not only dominates the codes", but also "exercises social practices based on them” (SOUSA, 2019, p. 47-48).

Therefore, Media-Visual Literacy is now positioned as an emerging knowledge. Such context manifests itself and intensifies with the possibilities arising from the digital era and with the rise of audiovisual culture. It is no longer only the school and the family that are central to the education of children and young people. Alongside these two, and with discourses that are even more attractive and adaptable, the media, in its multiplicity of images, has become another space where oppressive pedagogies circulate on the ways of being and being, today and now, in the world (GIROUX, 1995; FISCHER, 1997; FREIRE, 2016; MARTIN-BARBERO, 2011; SOUSA, 2016).

This exploratory/bibliographical study1 articulated the discussions that surround the notions of photography, media, education, and human rights, based on theoretical concepts that deal with Media-Visual Literacy (Media Education and Visual Literacy). The purpose of the research was to discuss the role of the teacher and the school in the mediation of media content consumed by students, considering the effects of media culture and images in the constitution of reality and identities of contemporary children/youth. Thus, this research project sought to apprehend which are the comprehensions, aptitudes, and afflictions that the teachers have in relation to the didactics aimed at the Media-Visual Literacy within their specific school contexts of performance.

Therefore, the core of the research was methodologically designed in two stages, both focusing on teaching staff of nine municipal schools of complete elementary education in the municipality of Novo Hamburgo (NH), in Rio Grande do Sul (RS). The quantitative first stage aimed to diagnose the perception of teachers about what it means to be literate and be literate in this current time, as well as the conceptions that educators have about Media-Visual Literacy. The second stage, qualitative, aimed a dialogical action with a focus group of teachers to build a possible practical-methodological path for the development of didactics focused on the construction of a Media-Visual Literacy within the school2. The purpose of this activity consisted in using the photographic language, from the study of its specificities, as a way for teachers to perceive ways to discuss the media and communication technologies during class time. Although the two phases have occurred in different periods, it is reiterated that both complemented each other in the investigative development of the study - orchestrated through action research (THIOLLENT, 1986).

It is also important to situate this research in its wider scientific scenario. Therefore, the efforts of this research and its researchers are anchored, above all, in the light of two fields.

The first field is called Communication/Education, an area that, by combining the knowledge of two specific sciences - Communication and Education - discusses the need for a critical training to the media and communication tools, both in the university and in the school territory. It has as reference in this study, mainly, the contribution of two important researchers in the national scenario, Baccega (2001) and Soares (2014), who have addressed the urgency of the theme. In the second field, Cultural Studies, it is cited the provocative and epistemological perspectives launched by Kellner (1995) and Giroux (1995) as fundamental to think a critical approach, based on conceptions of culture for Media-Visual Literacy.

This research seeks to contribute, through dialogue, with authors from these two fields, with discussions and proposals that lead to think about the substantiality of conducting a Media-Visual Literacy not only with an educational action restricted to the students, but also, and in an even more attenuated and preliminary way, with the teachers, through continuous training. Indeed, it is in the context of a teaching exercise that these issues or this practice become hopeful in the classroom.

It is pointed out that this article is organised into four sections: the first, called "Methodological Path", elucidates the main procedures and decisions that circumvented the application of action research in the particular context of this study, in addition to outlining the data collection techniques and the subsequent analytical work operationalised for the reading and interpretation of the information obtained; In the second part of this article, entitled "Media-Visual Literacy: A Human Right at School?" some theoretical assumptions are discussed which investigate the culture of media and images from the specificities of the school territory, to reflect on their role and function of educational institutions and their professionals. the third division of this essay proposes "Ways to Plan a Media-Visual Literacy through the Study and Use of Photographic Language in School", an idea developed from an educational process consisting of three stages, which together lead to the training and the empowerment of the gaze in the usual moments of class; Finally, the last component of this research is called "Discussing Media-Visual Literacy in Teacher Education: a Formative and Investigative Practice Developed through Action Research", which presents an ethnographic report of the trajectory covered by the researcher in the field.

METHODOLOGICAL PATH

Thiollent (1986, p. 26), a sociologist specialized in qualitative and participative research methodologies, understands research-action as "social research with a practical purpose", following "demands proper to the action and participation of the actors of the observed situation". He approaches action research from a composite of frameworks, which he calls " scientific principles", assisting the researcher in the dismemberment and ordering of the study (THIOLLENT, 1986, p. 26). It is in this sense that Sousa (2019, p. 16) elucidates the action research as an investigative structure that is regulated in four distinct stages: "exploratory, planning, action and evaluation”.

The exploratory or mapping period is the initial step that precedes the interventions that will be developed with the action subjects (SOUSA, 2019). Therefore, the planning stage, which results from the notions grasped by the researcher through the data collected in the previous phase, is a moment in which an action plan is formulated to address the weaknesses exposed by the target population (SOUSA, 2019). The implementation of the action, on the other hand, which must embrace dialogue as the main tool for the smooth progress of the dynamics, proposes that the problem investigated is collectively pondered and reflected (SOUSA, 2019). Finally, the last stage of action research, which consists of the evaluation, is an examination that should occur not only at the end of the investigative journey, but throughout the trajectory of the researcher in the field, and the study participants may deliberate about the activities as they are developed (SOUSA, 2019).

However, it is fundamental to pay attention to the linear process constituted by the referred phases of action research and to the set of technical operations that enable data collection during fieldwork. In this sense, Thiollent (1986) suggests a variety of tools and methodologies that must be reflected upon individually to understand which are the most appropriate within a singular study condition. Therefore, it is clarified that this research adhered to the following definitions.

The first decision concerns data collection from the target population in the exploratory stage (phase 1 of action research). In accordance with Prodanov and Freitas (2013, p. 98), it is reiterated that this research intended to work not with the totality of subjects that originate the universe of the study, i.e., group of people "who have the same characteristics", but with "a subset of individuals from the target population". Considering that the focus of this research are the teachers of nine municipal schools of complete elementary education in the city of Novo Hamburgo/RS, it was found that 270 teachers work in Basic Education of these institutions, forming, thus, the integrity of the sample environment.

This mapping stage aimed that among these 270 teachers, at least 105 teachers would constitute the introductory survey, which occurred by means of electronic questionnaire in the survey model. For this equation, it was considered a confidence level for the sample of 95%, against a margin of error of 6%, besides opting for a homogeneous profile in the distribution of the target population. Therefore, these teachers had their perceptions ascertained in the composition of a probabilistic scenario that corroborated to evidence the context of Media-Visual Literacy in complete elementary schools in the city of Novo Hamburgo/RS.

The second resolution involved the performance of the practical actions of the investigation (phase 3 of action research). In this regard, it is clarified that the formation of this focus group arose from an intentional selection, that is, a "small number of people [...] chosen intentionally on the basis of their relevance to a given subject" (THIOLLENT, 1986, p. 63). This class was made up of a sample of 18 teachers, with two teachers representing each of the nine schools that make up the sample universe described above. For this, it was requested to the pedagogical coordination of each one of the institutions to indicate professionals who were interested in the discussions surrounding the theme of this study to compose the dynamics of the research-action. Moreover, it was asked that, in this designation, it was considered a teacher of the early years and another one of the final years, to have a diverse group of educators in relation to the level of school performance.

The methodological path followed by means of action research has been succinctly elucidated and the way this study organized and interpreted its findings is explained below.

Beforehand, it is important to emphasize that the quantitative stage of this research did not aim at an individual examination in relation to the information collected, once this ascertainment was constituted as a situational diagnosis (THIOLLENT, 1986) concerning the problematic inquired, which derives from the initial exploratory period of the research-action. The quantitative approach presents, amidst the 110 replies obtained, significant data which already enable a relevant interpretative construction for the investigation. In this study, however, it is integrated as a set of elements which are interwoven with a collection of larger referential bases concerning the problematic (herein referring to other aspects and notions which emerged from the other phases of action research and which, equally, complemented and affected the analyses).

Thus, it is hereby made clear that the central data corpus, on which the analytical effort of this study is focused, refers to the set of records that originated from this closer work with the study subjects (field diary notes, video and audio recordings, photographic records, and interviews). These mechanisms, besides helping to document the information, contribute, according to Patias and Hohendorff (2019), to the control of subjectivity, a characteristic that results from this closer relationship between the researcher and the individuals involved in the research.

Therefore, the complexity of the data from the phases of action research were interpreted and theoretically confronted considering two analytical perspectives: "the school culture" and the "culture of the school" (OLIVEIRA, 2020, p. 8). For Oliveira (2020, p. 8), school culture indicates "a way of operationalize the knowledge within specific institutions in modern societies", i.e., it thinks the school territory and its internal dynamics of performance in a broad and culturally aligned perspective. On the other hand, the culture of the school, according to the same theorist "takes into account the heterogeneity that is hidden in the apparent homogeneity of education systems", i.e., what distinguishes each institution in its own commitment and activity, considering the particularity of their subjects and the community that surrounds it (OLIVEIRA, 2020, p. 8). Therefore, it was about analysing the Media-Visual Literacy from issues involving the macro and micro educational environment, from conceptions that universalize (academic view) and others that singularize (native view) this pedagogical conduct in schools.

Finally, it is important to point out that, although it is not the intention of this work to discuss in depth the results of the exploratory period, some conceptions and statistics of this stage will be presented during the theoretical explanation of the research (which will occur in the next sections), in order to understand some of the problems that led this study to design the dynamics that involve the interventions resulting from action research.

MEDIA-VISUAL LITERACY: A HUMAN RIGHT AT SCHOOL?

Kellner (1995, p. 106) reflects on the concept of "a new critical pedagogy which attempts to broaden the notion of literacy", as being an expansion of what is called culture, in which a move away from ideas which, for a long time, subjugated certain cultural manifestations as superior and inferior, worthy, and unworthy of being conceived as products of human knowledge, is noted. The educational system, often clinging to such premises, started to limit its learning methodology in the construction of certain languages and artifacts of culture, sometimes disregarding, over time, the emergence of other knowledge that also materialized as relevant expressions of human scholarly (PEREIRA; FILLOL; MOURA, 2019). Therefore, a pedagogical construct is sometimes evident which, as a rule, considers the "knowledge" and the "experience" acquired by individuals outside the school perimeter as irrelevant and as "common sense knowledge" and therefore "not worthy of respect” (FREIRE, 2014, p. 16).

Indeed, we exist amid a multicultural society, mediated by "different technologies of writing and reading", i.e., a society that expresses the world in different ways, which implies the multiple literacies concept that enable individuals to read and interpret these varied meanings that are produced in this same collective space of life (SOUSA, 2019, p. 50). The world can be seen, written, and interpreted under different conceptions, being able to be written, photographed, sculpted, painted, sounded, filmed, publicized, sung etc. In short, the world can exist and recreate itself under unique optics of human manifestation.

Many of these speeches, are carefully produced and permeated with intentions, causing action and awareness, i.e., a learning. They contribute to the formation of "behaviours and values in force throughout society" (SOUSA, 2016, p. 175). In this context, it becomes unfeasible an irresponsible attitude of the school to ignore the presence of the media and their images in the constitution of being, since different technological tools mediate consciousness and realities through the representations that weave about individuals and their daily lives (KELLNER, 1995; GIROUX, 1995; FISCHER, 1997; BACCEGA, 2001; MARTIN-BARBERO, 2011; SOARES, 2014; ALBINO, 2015; RADDATZ, 2015; SOUSA, 2016; SOUSA, 2019; PEREIRA; FILLOL; MOURA, 2019).

From this standpoint, when the teachers participating in the initial diagnosis of this research were asked if Media-Visual Literacy is a human right nowadays, it can be observed, among the exposed perceptions, that 93.6% considered that yes, since everything "that we do nowadays involves the media, it becomes something of everyday life, object of communication and everyone must be inserted and with the ability to discern. It is a right as communication and expression of language and thought" (Teacher of the Final Years of Schooling, with more than 20 years of teaching). However, 6.4% of the respondents do not consider it a human right, given that "there are other demands that are more essential" at school (Teacher of the Final Years of Schooling, with over 20 years of teaching) or that "it is an option, but not fundamental, at least in the Early Years" (Early Childhood Teacher, with over 20 years of teaching).

Furthermore, still within the negatives of this same question, it was found that 3% of the participants reported a lack of knowledge on the theme, exposing "doubt on the concept of human right and the relation with Media-Visual Literacy" (Teacher of the Final Years of Schooling, with more than 10 years of teaching). Among the affirmative answers, it is also interesting to note the recognition of the teachers, 23% of them highlighting the omnipresent factor of the media in our daily lives and the pedagogical role played by the media: "the media is responsible for influencing our tastes, gestures and attitudes, we are in contact with it many hours a day. Therefore, we can be manipulated if we don't know how to understand the objective of the speeches, advertisements, images, etc." (Teacher of the Final Years of Schooling, with more than 20 years of teaching).

Martin-Barbero (2011) compares the influence of the media in our society with the same significance and the same indispensable value of the environment for the world. For the author, the vital importance assumed by a “green ecosystem” correlate to what he calls "communicative ecosystem" (MARTIN-BARBERO, 2011, p. 125). Kellner (1995, p. 108) also makes a comparison of similar valuation, alluding to a world taken by "a flora and fauna made up of varied species of images", referring especially to those that are configured in a media way of being. Likewise, Santaella (2012, p. 11), that thinks modern society as a "real forest of signs". The authors, when making these and other relations, allude not only to the significant space conquered by the media in everyday life and social relations, but also the dominant aspect and the imperative character of the communicational discourses in the structuring of reality and the maintenance of life. Without a doubt, the media is today a basic axis on which human existence and the very way of existing in the world is based. (SOUSA, 2016).

Therefore, we must reflect why the school is not, even today, effective in incorporating other ways of reading and interpreting reality, bringing, for example, the media repertoire itself as a theme for discussion and reflection in the classroom (COSTA, 2013). For Albino (2015), in these spaces, the source of knowledge, within what is important to be known about the world, is still the words - whether those that make up the textbooks of the various subjects or those that are written on the blackboard by the teacher and mechanically copied by the students in their calligraphic notebooks.

This disharmony, between what adolescents understand in their daily lives - mainly through the intimate relationship established through the media with what they assimilate as being a typically school content -, is not an exclusive situation of contemporaneity, given that the school has shown itself, over time, as an institution unable to adapt to the transformations that society and its individuals have been undergoing (PEREIRA; FILLOL; MOURA, 2019). The fact is that now, in a world that reveals itself in many ways technological and mediatized, such disagreements become more evident, leading us to ponder on which premises the school has been settling and shaping its ways of teaching or, in other words, what it has been conceiving as a significant knowledge to be undertaken with/to the students. For Pereira, Fillol and Moura (2019, p. 41, our translation), the education system is still rooted in an "excessively scholarly vision of learning, which seems to marginalize the knowledge that young people develop with and through media and digital platforms”.

According to 16% of the teachers participating in this research, this ineffectiveness occurs due to the lack of knowledge about how to work the visual language and technical resources of media production in the educational environment, in which many teachers report "a need to expand the knowledge in relation to the visual elements" (Teacher of the Final Years of Schooling, with more than 10 years of teaching), demonstrating that "there is a lack of background" on the subject (Early Childhood Teacher, with more than 15 years of teaching), in addition to indicating "that a training course would be of great help" for the inclusion of these other literacies in daily teaching practice (Teacher of the Final Years of Schooling, with more than 5 years of teaching).

Nevertheless, when we approached the educators, in the same exploratory period, about being a school and teacher's commitment to make the students media and communication technology literate, it was found in the answers given that 20.9% did not think it was a responsibility of the institutions and their professionals, since, according to them, "not everything is the school's commitment, if we attribute everything to the school, it will not be able to take care of it in only 4 hours a day" ((Early Childhood Education teacher, with more than 10 years of teaching). As stated by the teachers, "nowadays, the teacher educates to form the character of the child, teaches the contents pertinent to the curriculum" (Early Childhood Education teacher, with more than 3 years of teaching), and that "the demand of the contents themselves absorbs the entire class period [...] available" (Early Childhood Education teacher, with more than 20 years of teaching).

Baccega (2001) points out that the main educational commitment today should be precisely to reflect the democratic context from these media representations of the world. For the author, it is necessary to learn to read these visual texts coming from the media and question which are the intentions and the truths that guide the creative content of these productions in circulation. Moreover, it is common the perception of children and young people, in relation to the knowledge acquired with the media, that they work "as a quick and instantaneous elixir" for the resolutions of the difficulties that guide life, as a kind of practical manual, constantly updated, of how to live in a world that, at all times, reinvents itself and transforms itself into a new existence (PEREIRA; FILLOL; MOURA, 2019, p. 43, our translation). Therefore, it is precisely on the content of these "utopian discourses of informal learning" that the current pedagogical commitment of formal education resides, that is, to promote a posture of greater wisdom and discernment in the consumption of these media-visual lessons (PEREIRA; FILLOL; MOURA, 2019, p. 43, our translation).

When the teachers were questioned if visuality lacked an education regarding its language and its specific form of communication, 86.4% said yes, noting that "images are often used as a referential complement, but can be used in a much more applied manner" (Teacher of the Final Years of Schooling, with over 5 years of teaching), considering that visuality "was not part of the training of many professionals who work in education, in addition to being a resource widely used by the media, and rich to be exploited" (Early Years Teacher, with over 20 years of teaching). Even so, 13.6% of the participants reported there was no need for media-visual literacy, pointing out, among other issues, that "the image is universal, and therefore it rarely needs explanations" ((Teacher of the Final Years of Schooling, over 3 years of teaching) or as "something already intuitive, [...] for this generation" of children and young people (Teacher of the Final Years of Schooling, over 20 years of teaching).

In the meantime, the intention is to show in this study, amid the convergence of these different perceptions, how essential is the need for the school to take the images, especially those that are forged as media productions, as "a terrain of pedagogical and ideological struggle" on which society and its individuals begin to format and establish themselves as organization and people (GIROUX, 1995, p. 137). Educating for media and images, in this sense, comes to "emancipate" individuals "from contemporary forms of domination, leading them to be "more active citizens, competent and motivated to engage in processes of social transformation" (GIROUX, 1995, p. 137).al” (KELLNER, 1995, p. 107).

Not recognizing Media-Visual Literacy as a human right nowadays is the same as "repeating the hegemonic process of the dominant classes, which have always determined what the dominated classes should know and can know" (FREIRE, 1994, p. 80). After all, as pointed out by Martin-Barbero (2011, p. 134), "free people are people able to read advertising and understand what it is for, and not people who let their own brains be massaged". Therefore, in the search to cooperate with these new tasks of education, it was formulated a practical-methodological process for the development of a Media-Visual Literacy from the study of photographic language in school, which can be a didactic plan re-signified and adapted to the most varied objectives and contexts of teaching.

PATHWAYS TO PLAN A MEDIA-VISUAL LITERACY THROUGH THE PHOTOGRAPHIC LANGUAGE STUDY AT SCHOOL

The Media-Visual Literacy, is an essential formative action, as already elucidated, in the context of imagery relations of the contemporary world. It is in this sense that Santaella (2012), when reflecting on the credulity of our gaze against the different ways of seeing and conceiving the contemporary world, points to the urgency and the need for the school to appropriate the responsibility of educating for this agglomeration of images that surround the daily life, in order to literate not only verbally, but also visually their students. According to the author, visual education consists in developing the look for the critical reading of images, improving the perception of the students in relation to the senses that permeate the textual structure of this communication, so that they identify what originates and manifests itself in the internal organism of the representations.

Furthermore, Dondis (2015, p. 3), reflecting on the concept of literacy, considers that its notion implies leading a group of people to share the "meaning attributed to a common body of information", and that in image education, therefore, this same intention should also be operationalised: "to build a basic system for learning, identifying, creating and understanding visual messages that are accessible to all people", and not only for individuals who have been particularly instructed in this language, such as photographers and other communication professionals.

Hence, when reflecting on a proposal of Media-Visual Literacy in school, with its possible strands of action and construction of knowledge, it was sought for working methodologies that surround the universe of images with the intention of applying them both to the field of meaning, process of elaboration of these speeches, as the interpretation, reading system and decoding of these messages. Moreover, it was sought for tools and dynamics conducive to the specificities of the place of education and their subject/subjects (schools, students and teachers), taking into account, also, that the visual language intended to conduct the training was the photographic.

The photography choice as a pedagogical tool occurs exactly for recognizing that the images are one of the main communicative tools of nowadays - and here thinking not only in the imagery product, but also in enabling mechanisms of these productions. Undoubtedly, it is in this extensive amount of images, which confront us every day, that we observe the relevance and power of this language and its technologies in the ways of communicating, relating and manufacturing meanings in contemporary times. To produce and consume images is to produce and consume existences in an increasingly visual world (KELLNER, 1995; FISCHER, 1997; SOUSA, 2016).

Considering the application of photography in the context of this literacy, it was questioned to the teachers, in the introductory survey of this research, if they consider photography and its creation mechanisms important pedagogical tools inside the school, as much as paper and pencil. Regarding this understanding, 95.5% of the teachers said yes, indicating that it is a relevant "visual aid" "to compose scenarios and social changes" (Teacher of the Final Years of Schooling, with more than 10 years of teaching), in order to provide "the students with a space to express themselves through photographs" (Teacher of the Final Years of Schoolings, with more than 15 years of teaching). However, 59.1% of the respondents said that, although they are interested in working with photography in the classroom, they would not know how to develop a didactic strategy based on the language, 55.4% saying they do not have the technical knowledge to do so.

Thus, in an effort to contribute to the media and images study to be understood by teachers as a possible pedagogical conduct in the daily reality of the classroom, it was developed a methodological procedure based on the perspectives of three associations, which relate to different "moments of the cognitive process, involving the organs of vision and visual mental and linguistic processes", which are "image/vision, image/thought and image/text" (COSTA, 2013, p. 39). According to Costa (2013), these divisions, for representing specific cognitive stages of the human intellect, when they are articulated in teaching practices, such as school practices, instigate new skills and abilities of students. In this sense, we will take these three categories defined by the author as steps of a process of Media-Visual Literacy based on photographic language, following a methodological order that we consider as relevant to the assimilation of concepts and practices by students.

The first stage, called "image/text" (COSTA, 2013), aims to lead the students to understand how to communicate and how to produce senses through the fundamentals that give origin to the photographic language - with the intention of demonstrating that, as well as the verbal writing, the images (and here, especially, the photographic ones) also embrace an idea, expressing a concept, being able to be de-naturalized, thus, the idea of these expressions as organic and factual records of everyday life. The next phase, called "image/vision" (COSTA, 2013), suggests putting into practice, through exercises of observation and capture, the elements of photographic language that were previously elucidated, in order to break with the notion of a naive passive action of the gaze on the technical apparatus of production (the camera, in the case of this study). In turn, the "image/thinking" (COSTA, 2013), third and last stage of this formative process, proposes to undertake a system of reading the set of photographic texts produced by the students during the activities of observation and visual creation, in order to reflect on the different visions that we cultivate of reality and how the look is constantly taught to mean the world within a certain set of precepts and standards.

Finally, considering the actions that would be developed with the teachers focus group in the qualitative stage of this research (explanation that will follow), a Guide to Media-Visual Literacy at school was prepared, a document that gathers, in a didactic and illustrative way, the three stages that were succinctly presented here, besides including suggestions of activities and support materials for each phase of the process. Moreover, this script was also structured with the dissemination of this practice in mind for other professionals and their schools, not being a material restricted to the teachers and institutions of this research. Thus, it is informed that the content is available for download3.

DISCUSSING MEDIA-VISUAL LITERACY IN TEACHER EDUCATION: A FORMATIVE AND INVESTIGATIVE PRACTICE DEVELOPED THROUGH ACTION RESEARCH

Once the diagnosis stage was concluded (phase 1 of the action research, of quantitative scope), it was possible to have a more explicit view from the analysis of the set of answers provided by the teachers participating in this mapping (as described in the methodological path). The understandings and unknowns were comprehended, as well as the difficulties and divergences around Media-Visual Literacy in Elementary Schools in the city of Novo Hamburgo/RS. Since then, it was developed the planning of actions that allowed to discuss these issues with the group of teachers who constitute the qualitative stage of this work, as a way to elucidate and face the problems exposed.

It is fundamental to explain beforehand that the dynamics that made up the interventions of this research in the field were conceived and promoted within a formative program entitled " Non-discriminatory Education", an agreement between the Education Department of Novo Hamburgo (SMED/NH) and Feevale University (Feevale), developed by the Research Group Children in the Media: Study Center in Communication, Education and Culture of Feevale. The purpose of this activity was to create spaces to raise awareness and sensitivity among teachers working in the city's public school network through discussions on the different relationships between human rights and the pedagogical exercise of these professionals.

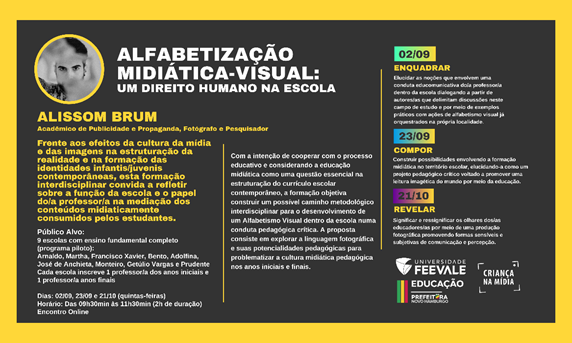

Source: Criança na Mídia ('Children in the Media',2021).

Figure 2 Training Card/Activity with the teachers

hus, in view of the alignment of the objectives of this study with the intention of the aforementioned Programme, three formative and investigative actions linked to the dynamics of this project were organised, named Framing, Composing and Revealing. Therefore, to invite the institutions participating in this research to enrol in these three meetings4, a card was produced detailing the general purpose of this realization and the designs that guided each specific front, besides punctuating the target audience (which followed the sample composition rule already elucidated in the methodological section of this study), as well as the day, time and place of the meetings, which were held online, given the pandemic context at the time5 always on Thursday mornings, from 9:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m., totalling 2 hours of duration per session.

Hence, in the introductory meeting, called Framing (Enquadrar, in Portuguese), which took place on September 2, 2021, the proposal was to demarcate some issues that outline the primary topics of this research. For this, it was discussed, initially, with the group of teachers about the current scenario of Media-Visual Literacy in Elementary Education schools in Novo Hamburgo /RS, through the data seized in the local research-diagnosis on the subject, because as Thiollent (1986, p. 65) warns, "in action research the questionnaire is not enough in itself. It brings information about the universe under consideration" that need to be, subsequently, worked with a representative group of the sample.

Moreover, we sought to elucidate the notions that involve an Educommunicative conduct (SOARES, 2014) of the teacher at school, both through a theoretical perspective, dialoguing from authors that delimit important discussions in this field of study, and through practical examples with actions of Media-Visual Literacy already organized in the community. The effect of this first conversation with the educators is clear in the report of one of the teachers participating in the meeting:

I have to say that I am concerned about that minority, which is a minority. But we saw there [in the data presented in the exploratory phase] colleagues who believe that working with the media at school or working with images at school is not associated with what is fundamental to work with, right? I don't see a division between our media work and study and literacy, or as it appeared there [...] Let's say, I don't see that the media work is something else: "ah, it's another chapter of what is essential to work at school". I think that things go through each other, right? Things multiply themselves like that. (Teacher-participant, oral information).

Living in a society that is placed around the media, it is imperative to put "on the agenda discussions that refer to the right to communication as a fundamental human right" (SOUSA, 2019, p. 42), that is, as a basic and essential good for the unfolding of contemporary existence. Therefore, Media-Visual Literacy, once incorporated into the essence of school practice, according to the understanding expressed by the teacher, comes to be a means for this right to become an increasingly tangible benefit in the daily reality of people (MARTIN-BARBERO, 2011). However, such practices to be inserted in the school, although they are perceived by most teachers (according to the data exposed in the exploratory stage) as relevant and fundamental pedagogical conducts, are still sometimes misunderstood and unfeasible way of some professionals:

I always thought I was very incompetent in this area, but listening to everything that Alissom brought to us, you can feel how this is in our essence and in our daily lives, to be able to look at this, right? It is much more than technology, it is another logic, right? I don't need to master technology to work on these issues. (Teacher-participant, oral information).

By intervening in a pedagogical rationality solidified in years of teaching, it is common to perceive the fear and, many times, the teachers' unpreparedness facing this new educational commitment, especially in relation to the intention and the use of technologies in the Media-Visual Literacy. Along these lines, it is pertinent to reiterate that the intention is not that teachers act as facilitators between technologies and students, but as mediators in the use of these different devices, to articulate class spaces that discuss this relation of consumption and production of meanings through techno-communication devices (RADDATZ, 2015). In view of this, Soares (2014, p. 19), warns that "an adequate formation of teachers for the XXI century demands their transformation into managers of communicative processes, in which the dialogue becomes a support for the pedagogical articulation”.

Therefore, to conclude this initial moment of sociability, we proposed an exercise with the group of teachers with the intention of raising awareness of the possibilities and meanings that emerge from the work with the visual language, but specifically through photography and its technologies, seeking to demonstrate its potential in promoting a more empathetic, conscious, and critical look at the different realities of life. The teachers were invited to visit the Photographic Exhibition Criança na Mídia: Tempos de Discriminação e Direitos Humanos (Children in the Media: Times of Discrimination and Human Rights), with the idea of rediscovering this international pact for life through the relationship between human rights, photography, and childhood. After browsing the virtual version of the Exhibition, the participants were challenged to select an Article of the Declaration to compose a photographic re-reading, to contextualize and give new meaning to the chosen Article based on components and experiences of their own daily lives.

Using the elaborated photographs6, we shared the compositions with the group and, together, we tried to unveil which article of the Declaration the author of the image tried to imprint in its production. Initially, during the conduction of the dynamics, the composer of the photograph did not present the meanings sought with his/her visual construction, thus allowing the group to develop an interpretative and subjective look over the several creations. These multiple perceptions, in turn, allowed different Rights to be seen for each image, seen and understood from different approaches of the human existential condition. After some reflections on the set of photographs produced, the author of the image spoke about the Article he or she tried to represent. Below, one of the images designed and analysed by the group of teachers:

This photograph, according to its author, sought to represent Article three of the Declaration, which in summary states that all persons have the right to life and to live in freedom and security. The image proposed to expose the existence of the gypsy people and was captured by the teacher inside the car, because, according to him/her, it is a common reality that calls his/her attention on the way he/she travels every day between his/her home and the school where he/she teaches. The association with the Article occurs because the teacher notices the disrespect and lack of dignity experienced by this community every day:

They suffer a lot of prejudice; they have no right to security. I also related it to the indigenous people because there's a market near here and when they go to the market, they are frowned upon because of the way they live. What happens is that many people think that, in fact, just like the indigenous people, they should evolve, they don't see it as a form of their culture. This situation of movement was on purpose because I wanted to say that I pass by, right, and like everyone else, suddenly we pass by several times, and we don't even notice [...]. (Teacher-participant, oral information).

Although the photographs were composed based on a specific Article and the dynamic was based on discovering which Human Right was part of the colleague's creation, the objective of the activity was not for the teachers to succeed in the interpretative reading of the image, that is, to find out what the author of the image proposed to transmit as a creative concept. Thus, through this exercise, we wanted to ponder with the teachers that it is impossible to look at life without looking at the integrality of Human Rights, since they manifest the essence of our dignity to exist. Therefore, in the search to discover the Article established in the image, the teachers realized that it is difficult to determine only one, since all of them are important and vital to live fully in the world.

It was possible to demonstrate to the teachers that, when promoting Media-Visual Literacy in the classroom, Human Rights will always be circumventing the discussions that involve this educational action, given that the commitment to the notion of these Rights "is simultaneously the means and the end" (MAIA, 2007, p. 99) of any pedagogical activity aimed at a critical view. It is along these lines that authors such as Candau (2007), Maia (2007) and Raddatz (2015), affirm the importance of thinking about an education for Human Rights that goes beyond paper, books and theories, being photography a great tool for this, because it enables to think these Rights by the factor of subjectivity, that is, how the students relate to these Rights and what they say about their ways of life. Therefore, Media-Visual Literacy goes beyond knowing how to deal with technologies, and/or, in the specific case of this study, knowing how to read and produce photographs: it is an educational action that, through the gaze and the gaze towards life, emancipates and promotes citizenship. According to Genevois (2007, p. 10), "it is not enough to recognise and affirm Rights on a political and legal level. It is necessary to accomplish, above all, a work of formation, which reaches hearts and minds".

The second meeting, called Compor, which took place on September 23, 2021, sought to weave together with the teachers some procedures of production and reading of images, through theoretical and practical exercises involving the use of photographic language and its mechanisms of expression (methodological proposal that was briefly presented in the fourth section of this article and that makes up the Media-Visual Literacy Guide. In short, the goal of this meeting was to break with the idea of a visual literacy restricted to "the use of works of art or the erudition in cultural and artistic terms", presenting to the teachers’ new possibilities and teaching needs facing the current communicative reality of humanity and the visual amplitude that surrounds this exchange of information increasingly diverse and prolific (COSTA, 2013, p. 51). The discussion content is perceptible in the reflection conducted by the teacher:

We talked about all that repertory, a painters' repertory, right? And around the end, after a long time of working, I thought but, people, I only have here European canons and some American ones. Only images of male and white painters. And then, after many years of only working with images, I started to work on the supply of images, right? Of course, we must show them, but I also started to feel the need to discuss with my students what was available to them as media. (Teacher-participant, oral information).

The point of view exposed by the educator conflicts with the theoretical approaches that subsidize the argumentations and the deductive of this study, when pointing that the educational institutions need to integrate other expressions of human knowledge (KELLNER, 1995; MARTIN-BARBERO, 2011; SOUSA, 2019), making use of technologies and languages that surround the subjects' reality, which means a search for the "construction of open and creative communicative ecosystems in educational spaces" (SOARES, 2014, p. 19). Due to this logic, it becomes important to understand the communication systems, in its different models and formats, not as adversaries of the teacher, but as important allies in the promotion of an emancipatory education, contributing with the accomplishment of the school function of developing individuals that reflect about the social problems and that are transformers of their own existential conditions (FREIRE, 2014; GIROUX, 1997).

Therefore, the school must remain open to "the dialogue about people's daily lives, about their relationships with the media system in the context of the information society, in order to educate for citizenship” (ALBINO, 2015, p. 339).

It was paying attention to these considerations that we aimed to present the photographic language as a powerful and attractive support for the development of this literacy with the students, since photography, as well as other images, is a common media in the daily reality of this generation and with which children and young people are daily relating and exchanging meanings. Studies on media training practices in the educational environment point to positive results in this approach between teaching, technologies and the different languages of expression (DELIBERADOR; ALVES; LOPES, 2013; SOUSA, 2019). Therefore, by reflecting with the teachers on a teaching process based on photography, the teachers were able to expand their view on how to work with the media in their own school contexts. Such topic is evident in the following teacher's report.

Since our last meeting, I decided to work with the ninth year of Elementary Education with photography, in which they had to choose some space in the school, to reflect about the school, but through some experience of their own. And it was really cool because that's what we were seeing, they look, but they don't see. They look at that place every day, they stop, but they don't stop to think why they chose that space in the school to stay, right? It even caught my attention that one of the boys, who is very introverted, took a picture of a reflection. When he showed me the photo, I immediately didn't know the place. He took a picture of a water puddle reflection and turned it upside down, and showed me the upside down image. It was an abstract work, it was beautiful, then he explained to me why that image was there. (Teacher-participant, oral information).

Through the use of equipment and common languages to the students' reality, it becomes possible to develop skills related to "autonomy and freedom of thought", being possible, from teaching activities (as the one described by the teacher), to promote a more critical attitude of the students about these devices and the communicative content of these productions (RADDATZ, 2015, p. 395). Photography, once inserted in the essence of the school activity, allows the manifestation of diverse "opinions and points of view", besides being an important communicative tool for the students to feel "safe to recognize and guarantee their rights", to see and value their own living and dwelling space. (RADDATZ, 2015, p. 395). The central issue when thinking about a new pedagogical logic that provides opportunities for other ways of media literacy and reflection is that "in the case of media technologies, it is not enough to master their use, but also the citizen's attitude towards them" (SOUSA, 2019, p. 114). Moreover, it is also of substantial importance to expand these perceptions to the relationships and the calls that emanate from other agencies and artifacts of socialization, such as the media environment and the cultural products that arise from the media:

We should take this exercise of looking at the framing and composition - the way the composition and framing is thought out - in the images that have been consuming our daily routine. Children watch a lot of YouTube, watch a lot of things on their mobile phones, teenagers use social networks a lot. I would take this proposal further, so that we can perceive the images that are in that media that we consume the most, to be able to reflect a little about it, to establish this discussion about the intention of the one who produces the image and puts it in the media, often we do not stop to think about why we are consuming or why this is appearing or not to us. (Teacher-participant, oral information).

Although photography possesses its own characteristic of communication and structuring of the message in relation to other types of images, its productive and interpretative systems allow to establish relations with the other conceptions of this nature. In turn, by understanding the technical procedures for the elaboration of a photograph, assimilating the set of components that encode and signify these visual messages, it is possible to broaden the students' look about these and other constructions that permeate the media, reflecting critically, thus, about the origin and the ideological operation of such communicational artifacts. The elements of photographic language - such as "angle, plane, perspective, lighting, focus", among others - constitute a path of possibilities for the conceptualization and examination of these symbolic productions (DELIBERADOR; ALVES; LOPES, 2013, p. 21). These constituents are pictorial information formulated by the photographer or sender now of capture, leaving a conceptual trace inside the image that, in turn, signs the authorship of the work and helps to reveal its creator's intention. Therefore, when we understand these technical processes of production and critical reading of images, enabling a more questioning look about these productions, we come to understand that the photographic representations, as well as many other visual manifestations, do not reproduce the "real", but strategically reconstruct it from the arrangement of certain signifiers (JOLY, 2012).

Kellner (1995, p. 127), says that a study about "familiar cultural" objects of the students, tends to reveal the game of intentions and interests that permeate this field of human production, clarifying how it happens and which are these modes of subjectivation. In this sense, understanding how these constructions affect the self and how they affect the very place of existence, means to apprehend "how society constructs some activities as having value and as being beneficial, while devaluing others" (KELLNER, 1995, p.127). Therefore, the main intention when Media-Visual Literacy is advocated as a human right in school is just that: de-naturalizing these productions that affirm standards for oneself, such as "gender roles and models of sexist and racist behaviour" (KELLNER, 1995, p. 127).

Finally, after being glimpsed by the teachers the possibilities that involve the approximation between photography and school, appropriating the own codes of this language and understanding how to apply it in the formative processes that bypass the education system, the last action, called Revelar (Reveal), took place on October 21st, 2021. This action sought, through a dynamic photographic production by the teachers themselves, to lead the group to express themselves and interpret their colleagues through the visual language, as a way of promoting affective and subjective forms of communication and perception through images. Below is one of the photographs produced that was interpreted by the teachers' group.

This activity started from the reflections of the last meeting (Compor), in which the teachers had to put into practice the elements they had understood about the photographic language, with the intention of revealing the way they look at the world. The author of the photograph above (figure 4) exposed that his/her way of seeing life is given in the

[...] texture of the form, in the lights that are reflected in the colours, through the perspective imposed by the flower, composing a delicate and soft point of view that unveils itself in the innocence of movement. Life gazing with a focus on depth of field, weaving plans through drawing representing beauty in a subtle, intuitive way that awakens sensitivity and emotion. (Teacher-participant, oral information).

The visual language component that predominates in the conceptual creation of this photograph is the depth of field. By applying the selective focus, the author of the photograph chooses to blur the foreground, focusing on the adjacent layer of the image, thus symbolising his search for a more compassionate point of view before the multiple layers that constitute daily life. Thus, the view can be understood as an "organizing, structuring and hierarchical function" of the real (COSTA, 2013, p. 42), after all, the gaze is called, at every moment, to configure a certain way of seeing. This happens in the definition of perspectives and views, in the choices of what we will focus or hide from the possibilities of contemplation. Consequently, the readings of the images produced provided "the humility and tolerance exercise", since it led the teachers to become "aware of the different worldviews that the same reality triggers" (COSTA, 2013, p. 43), thus providing the opportunity to locate the Media-Visual Literacy within a sensitive pedagogical practice, which seeks to recognize the uniqueness that dwells in each context of existence (ALBINO, 2015).

When we talk about revealing, it is also life-gazing, isn't it? The trainings make us look at life. Besides bringing situations to think about the school and the students, they also cause us a glimpse into our lives. And this is very important, I think we must have these moments to stop, talk and share, because this also constitutes us as teachers, as professionals. Because our students, who are there in the classrooms, also have a life and we must know how to look at it. (Teacher-participant, oral information).

To carry out a critical and reflective work that is based on the real life of the pupil inside the classroom is the essence that solidifies the proposal of this literacy action: to hold the "notion that pupils have different histories and incorporate different experiences, linguistic practices, cultures and talents" (GIROUX, 1997, p. 161) and, as such, they need to be seen and heard in their particularities and understood in their specific ways of expressing themselves. It is about allowing the students to socialize their own field of experiences, in order to turn the experiences of their being into an experience of teaching, transformation and democratic training (FREIRE, 2016). Therefore, the "critical literacy in photographic language" is a possible way to build these principles in the classroom (DELIBERADOR; ALVES; LOPES, 2013, p. 32).

I think it's very important to work on this kind of thing, because when they see what's around them, they recognize their place. Because, many times, they go to school, see that everyday life, the routine, and end up forgetting to see what is happening around them. It becomes that thing like that, the exercise without thinking, the automatic, right? The person starts to become automatic. I think they need to stop once in a while, stop to think, stop to look. I always tell them: "it is no use looking, you have to see". [...] And I think photography is perfect for this. (Teacher-participant, oral information).

Therefore, it was aimed, in the different discussions and actions operationalized with the teachers of this research, to show the Media-Visual Literacy as a didactic that relates to the practices of an emancipatory education (FREIRE, 2016), a teaching model that seeks not only to instruct, but to transform through the built knowledge. According to Freire (1994, p. 79), fostering a "reading of the world", with a critical and interpretative view on the circumstances that govern life, should always be one of the main pedagogical commitments of educational institutions, to provide, in the classroom, "a discourse that unites the language of criticism and the language of possibility" (GIROUX, 1997, p. 163). In the words of the teacher participant of the study, to do so, it is fundamental to understand that "it is not only the teacher bringing knowledge, but the students with their experiences enriching" and giving new meaning to school "knowledge" (Teacher-participant, oral information).

The Media-Visual Literacy, as a critical pedagogical project in school, will only be effective if conducted through a dialogical action, in which teachers need to oppose an authoritarian and oppressive posture, that is, recognizing that it is necessary to build knowledge with the students and not only for the students, since for many teachers teaching still "is to transfer to the learner the package of immobilized knowledge so that the learner mechanically memorizes the package" (FREIRE, 2014, p. 14). 14). According to Freire (2014, p. 17), "the good teacher is the one who, taking the student from his here, is not content with his here as a teacher and seeks to go beyond his here as a student". In this regard, in agreement with Martin-Barbero (2011, p. 123), for that to happen, the initial basic step, before taking any concrete action in school, is to ask what is the "communicative-pedagogical model" that prevails in the educational space, being essential "to start from the problems of communication before talking about the means”.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Although some authors' notes, on which this study is based, are conceptions of a certain time-historical, it is possible to realize, through more recent investigations on the theme (as this one that was developed), that, even today, facing the new visual forms of the subjects communicate and produce social meanings, the images continue being a cultural reality often put in second plan when thinking the teaching logics in the school space. Moreover, when comparing classic bibliographies from the field of education, as Freire (1994), Kellner (1995) and Giroux (1997), with more contemporary literature that equally think the area from the impositions of the universe of communication, as Martin-Barbero (2011), Albino (2015) and Sousa (2019), it is possible to realize how much the assumptions converge, indicating a linear educational path and few and other meanings (consideration that only includes the delimitations that tangent this research).

Among other issues, it is possible to observe the weaknesses that many teachers have when facing this new educational reality, in which it is possible to identify teachers that still do not recognize the media and the communicational technologies as another pedagogical space that shares the function of teaching, relating, for example, the Media-Visual Literacy concept only with the use and manipulation of electronic instruments by the students, disregarding, in this perspective, the search for autonomy and criticality before these creations that constitute our visual way of expressing and consuming information in the current media society. Moreover, although the teachers, in their majority, recognize Media-Visual Literacy as an important contemporary school commitment (according to the data exposed in the introductory survey of this research), it was found (in the more focal work with the teachers) that many are not supported by processes and methods that would allow them to work with the productive mechanisms and the interpretative systems of media images, thus manifesting a certain insecurity to conduct and mediate these discussions in the classroom.

In this regard, the outcomes of this work, considering its quanti-qualitative approach, developed through action research, allowed to establish a little of the scenario of Media-Visual Literacy in Elementary Schools in Novo Hamburgo/RS, a diagnosis that, although it has not been fully discussed in the scope of this article, allows reflections and future productions. Nevertheless, the intervention carried out in the school territory, from the work promoted with some teachers through the study of the photographic language, provided an opportunity for new ways of thinking and planning the teaching-learning processes, as well as providing the educators and students with the construction of knowledge which enables a more conscious and critical consumption of the communicational artifacts, as well as enabling more autonomy and responsibility in the use of media technologies as a form of democratic struggle and citizen expression. According to the evaluation of a participating teacher: "An extremely sensitive training that, in addition to providing moments of reflection on life, provided support material for teachers to develop this work in schools" (Teacher-participant, verbal information).

In the light of the above, the research indicates that schools will be able to effectively exercise their role as educational institutions of society, acting as a democratic space and citizen training, when in fact they reallocate their role facing this cycle of transformations through which the world has gone and will still go through. Namely, when they develop an educational commitment more in line with the needs of the citizen and of a world in transition. Today, undoubtedly, this will only be possible when the school recognizes and assumes "the media technicality as a strategic dimension of culture", dialoguing with these other " experience fields in which these changes are processed” (MARTIN-BARBERO, 2011, p. 132).

REFERENCES

ALBINO, Jacqueline Meneguel. A complexidade do cotidiano nas relações educativas. In: LAGO, Claudia; VIANA, Claudemir Edson (Org.). Educomunicação: caminhos da sociedade midiática pelos direitos humanos. São Paulo: USP, 2015. p. 335-342. [ Links ]

BACCEGA, Maria Aparecida. A construção do Campo. Revista USP, São Paulo, n. 48, p. 18-31, dez./fev. 2001. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Brasília, 2018. [ Links ]

CANDAU, Vera Maria. Educação em direitos humanos: desafios atuais. In: SILVEIRA, Rosa Maria Godoy et al. Educação em Direitos Humanos: fundamentos teórico-metodológicos. João Pessoa: Editora Universitária, 2007. p. 399-412. [ Links ]

COSTA, Cristina. Educação, imagem e mídias. 2. ed. São Paulo: Cortez Editora, 2013. [ Links ]

DELIBERADOR, Luzia Mitsue Yamashita; ALVES, Fabiana A.; LOPES, Mariana Ferreira. A fotografia como linguagem para a formação cidadã. Discursos fotográficos, Londrina, v. 9, n. 14, p. 13-35, jan./jun. 2013. [ Links ]

DONDIS, Donis A. Sintaxe da linguagem visual. 3. ed.São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2015. [ Links ]

FISCHER, Rosa. O estatuto pedagógico da mídia: uma questão de análise. Educação e Realidade, Porto Alegre, v. 22, n. 2, p. 59-80, jul./dez. 1997. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Entrevista inédita de Paulo Freire [Entrevista concedida à jornalista Marta Luz] Juazeiro Panorama. Bahia: Rádio Juazeiro, 24 abr. 1983. Programa de Rádio. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Paulo Freire: Pedagogia do Oprimido trinta anos depois. [Entrevista concedida a Dagmar Zibas]. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, n. 88, p. 78-80, fev. 1994. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Entrevista com Paulo Freire. [Entrevista concedida a Nilcéa Lemos Pelandré]. EJA em Debate, Florianópolis, ano 3, n. 4, p. 13-27, jul. 2014. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da indignação: cartas pedagógicas e outros escritos. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2016. [ Links ]

GENEVOIS, Margarida. Prefácio. In: SILVEIRA, Rosa Maria Godoy et al. Educação em Direitos Humanos: Fundamentos teórico-metodológicos. João Pessoa: Editora Universitária, 2007. p. 9-12. [ Links ]

GIROUX, Henry A. Memória e Pedagogia no maravilhoso Mundo da Disney. In: SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da(Org.). Alienígenas na sala de aula: uma introdução aos estudos culturais. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1995. p. 132-158. [ Links ]

GIROUX, Henry A. Professores como Intelectuais Transformadores. In: GIROUX, Henry A. Os professores como intelectuais: rumo a uma pedagogia crítica da aprendizagem. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1997. p. 157-164. [ Links ]

JOLY, Martine. Introdução à análise da imagem. 14. ed. Campinas: Papirus, 2012. [ Links ]

KELLNER, Douglas. Lendo imagens criticamente: em direção a uma pedagogia pós-moderna. In: SILVA, Tomaz Tadeu da (Org.). Alienígenas na sala de aula: uma introdução aos estudos culturais. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1995, p. 104-131. [ Links ]

MAIA, Luciano Mariz. Educação em direitos humanos e tratados internacionais de direitos humanos. In: SILVEIRA, Rosa Maria Godoy et al. Educação em Direitos Humanos: Fundamentos teórico-metodológicos. João Pessoa: Editora Universitária, 2007. p. 85-102. [ Links ]

MARTIN-BARBERO, Jesús. Desafios Culturais: da Comunicação a Educomunicação. In: CITELLI, Adilson Odair; COSTA, Mari Cristiana Castilho (Org.). Educomunicação: construindo uma nova era de conhecimento. São Paulo: Paulinas, 2011. p. 121-134. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Amurabi. Etnografia e pesquisa educacional a partir de Antropologia Interpretativa. Revista Eletrônica de Educação, São Carlos, v. 14, p. 1-12, jan./dez. 2020. [ Links ]

ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS - ONU. Declaração Universal dos Direitos Humanos. Paris, 10 dez. 1948. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://nacoesunidas.org/direitoshumanos/declaracao/ . Acesso em: 2 out. 2020. [ Links ]

PATIAS, Naiane Dapieve; HOHENDORFF, Jean Von. Critérios de qualidade para artigos de pesquisa qualitativa. Psicologia em Estudo, Maringá, v. 24, p. 1-14, 2019. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, Sara; FILLOL, Joana; MOURA, Pedro. El aprendizaje de los jóvenes con medios digitales fuera de la escuela: De lo informal a lo formal. Comunicar, Huelva, n. 58, p. 41-50, 2019. [ Links ]