Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.39 Belo Horizonte 2023 Epub 10-Jun-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469841031

ARTICLE

CODE OF ETHICS FOR THE TEACHING PROFESSION: EDUCATORS’ PERCEPTIONS AND OPINIONS

1 Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

2 Secretaria de Educação do Estado de S.Paulo. São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

3 Universidade de São Paulo. São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

The present research aimed to analyze the perceptions and opinions about the existence of a code of ethics for the teaching profession among the following groups: teacher educators, Basic Education teachers, and undergraduate students. The data were collected through a digital form filled out by the groups. The analysis indicated the need for an instrument that guides the actions of teachers when facing thorny situations, which are not discussed during study but are often part of everyday school life. Conversely, a concern was raised over who would develop this instrument and how it would be used by institutions. The results point to the demand of undergraduates, teachers, and teacher educators for educational processes that emphasize aspects of guidance, reflection, and decision-making in day-to-day school situations. The inclusion of these topics in teacher education courses is essential so that they can actively and critically participate in the continuous construction of a possible code of ethics or reflective practices regarding the principles and values that guide their profession. It is argued that the presence of the subject “code of ethics” in teacher education curricula is fundamental, as trainees need to be warned that future attributions in their daily work are not only limited to teaching, but also involve responsibilities arising from issues that emerge in this context and from the impact of their decisions on students, teachers, and institutions.

Keywords: Ethics; Teacher Education; Code of Ethics; Values

A presente pesquisa teve como objetivo analisar as percepções e opiniões sobre a existência de um código de ética para a profissão docente entre os seguintes grupos: formadores de professores, professores da Educação Básica e licenciandos. Os dados foram obtidos a partir de um formulário digital, o qual foi preenchido pelos grupos mencionados. A análise dos dados indicou a necessidade da existência de um instrumento que oriente as ações dos professores frente a situações espinhosas, as quais não são discutidas nos cursos de formação, mas fazem parte do cotidiano escolar. Por outro lado, houve uma preocupação sobre quem elaboraria esse instrumento e como este seria utilizado pelas instituições. Os resultados apontam para a demanda dos licenciandos, professores e formadores de professores por processos formativos que privilegiem aspectos da orientação, reflexão e tomada de decisões em situações do dia a dia da escola. A inclusão desses temas nos cursos de formação de professores faz-se essencial para que estes possam participar ativa e criticamente da contínua construção de um possível código de ética, ou de práticas de reflexão sobre os princípios e valores que norteiam sua profissão. Defende-se que é fundamental a presença do tema “código de ética” nos currículos de formação de professores, pois os formandos precisam ser prevenidos de que as suas futuras atribuições, no cotidiano laboral, não se limitam apenas ao ensino mas envolvem também responsabilidades decorrentes das questões que surgem nesse contexto e do impacto de suas decisões sobre estudantes, docentes e instituições.

Palavras-chave: Ética; Formação Docente; Códigos de Ética; Valores

La presente investigación ha pretendido analizar las percepciones a partir de las opiniones recolectadas sobre la existencia de un código de ética para la profesión docente entre formadores de docentes, docentes de la Educación Primaria y secundaria, y estudiantes universitarios. Los datos han sido recolectados a través de un formulario digital, difundido entre los grupos mencionados. El análisis indicó la carencia de un instrumento que oriente la actuación de profesores en situaciones delicadas, generalmente no discutidas en los cursos de formación y que están en el cotidiano escolar. Por otro lado, hay también una preocupación sobre quién desarrollaría este instrumento y cómo sería utilizado por las instituciones. Los resultados también indicaron la demanda de universitarios, docentes y formadores de docentes por procesos de formación que privilegien aspectos de orientación, reflexión y toma de decisiones en situaciones escolares cotidianas. La inclusión de estos temas en los cursos de formación docente es fundamental para que uno pueda participar activamente en la construcción contínua de un posible código de ética, o de prácticas de reflexión sobre los principios y valores que direccionan su profesión. La incorporación del tema “código de ética” en los currículos de formación docente es fundamental, ya que es necesario advertir a los universitarios que sus futuras atribuciones no se limitan a enseñar, sino que también implican responsabilidades derivadas de cuestiones que surgen a partir de ese contexto y del impacto de sus decisiones en los estudiantes, profesores e instituciones.

Palabras clave: Ética; Formación Docente; Códigos de Ética; Valores

INTRODUCTION

Often, teachers face ethical dilemmas in their daily work. In addition to a set of activities that are specific to it, various situations in the educational context can cause uncertainties, divergences, and controversies, without being sufficiently considered, requiring quick positions, and leading to decisions that may have unfair consequences.

The identification of some problems that commonly occur in the classroom, in the school, and in an academic environment, for which there are no clear answers and paths, would result in a preventive effort in teacher preparation, allowing teachers to put their values into practice and act accordingly to them, even considering the difficulty in identifying an ethical dilemma.

According to Ferreira (2010), autonomy, that is, the possibility of deciding by ourselves, does not guarantee ethical decision-making. Applied ethics only occurs in the relationship with the other, as it requires knowledge about one's values, principles, norms, and identity.

Thus, treating the ethical dilemmas and decisions that are part of the teaching professional life intuitively is just ignoring all the complexity that involves the exercise of decision-making. Applied ethics, according to Cortina and Martinez (2005), consists of the application of ethical principles, both from a utilitarian, Kantian, and dialogic perspective, investigating how these principles can help guide different types of activities. In this application, it must be considered that each type of activity has its moral requirements and its specific values. The authors point out that ethicists need to develop applied ethics cooperatively with specialists in each field; thus, it is necessarily interdisciplinary. Another highlight is that, in the elaboration of a professional code of ethics (CE), according to La Taille (2006), it is necessary not only to know the morality of society, which is diverse but also to consider the specificities of the profession. The author also proposes that university professors, when presenting the codes of ethics of the profession that the students have chosen, do not make the mistake of reducing them to a list of rules to be memorized.

From this perspective, this paper intends to discuss the possible implications of the existence or not of a code of ethics for teachers, based on the perceptions and opinions not only of teachers but also of future teachers and their educators.

PROFESSIONAL CODE OF ETHICS

Sá (2001), when presenting the importance of professional ethics, emphasizes that each set of professionals must follow a behavior to guarantee the harmony of the work of all, that is, from the conduct of each one, in a certain form of regulation of individualism before the collective. This consideration, in our view, highlights the point of permanent tension between the public and the private, a relationship that is often the subject of any discussion or ethical reflection. The author points out that “social feeling is imperative in the construction of ethical principles, and these are incomprehensible without it” (SÁ, 2001, p. 110). It is interesting to point out that the vocation for the collective has been rare nowadays, in the same way, the common good and the attention to the social have not received so much attention, and it is in these spheres where, unfortunately, egocentrism seems to prevail more. Considering the world of work, the emphasis on individualism can generate the risk of ethical transgression, hence the need for the protection of professional activities through ethical standards (SÁ, 2001).

To understand the role of the professional code of ethics, it is important to bring the definition of professional classes, which the present study adopts, among other notions:

A professional class is characterized by the homogeneity of the work performed, by the nature of the knowledge preferably required for such execution, and by the identity of qualification for the exercise. The professional class is, therefore, a specific group within society, defined by its task performance specialty. (SÁ, 2001, p. 116).

Although there are historical records of the existence of groups of workers for millennia, it is only in the Middle Ages that the beginning and organization of the working classes as a social phenomenon are recognized, when artisans gathered in corporations.

The value relationships between the outlined moral ideal and the different fields of human conduct can be brought together in a regulatory instrument, in this case, the professional code of ethics, which aims to establish ethical ideal lines, that is applied ethics. In this respect, the criteria of conduct of an individual before his group and the social whole can be a result of this code, and the interest in its fulfillment becomes everyone's interest, hence the importance of an ethical mindset and a relevant education that lead the willingness to act following established principles.

According to Sá (2001), the need for a contract of attitudes, duties, and states of conscience, finds in the code of ethics a solution among professional classes who graduated from university courses, such as accountants, doctors, engineers, lawyers, etc. The author points out that order must exist to eliminate conflicts, or rather, to “prevent the good name and social concept of a category from being tarnished” (SÁ, 2001, p. 118).

It should be noted that, in organizing a code of ethics, it is necessary to outline its philosophical basis. This base must be based on the required criteria to be respected in professional practice, which generally involves relationships with service users, colleagues, the professional class, and society. In the case of the teacher, the relationships with the student, with their parents or legal representatives, with fellow teachers, and with all actors in the school and academic communities, as well as with the nation, must be considered.

Thus, the philosophical basis is important and necessary to form the structure of the code of ethics, intending to establish how a professional can conduct the exercise of the profession not to harm third parties and to guarantee an effective quality of work.

It is worth noting that the experiences of elaborating a code of ethics generally had the participation of institutions and their leaders as their triggers, but such elaboration needs to arise from a broad debate and the intervention of all those involved, to guarantee its feasibility and scope. Updating such codes has always been necessary due to changes not only in customs, technological advances, and social policies but also in all factors that influence conduct.

The Code of Medical Ethics (CEM- Código de Ética Médica) of the Federal Council of Medicine (CFM- Conselho Federal de Medicina), for example, indicates, in its presentation, the need to revise its previous text, considering technological innovations and forms of communication and relationships. The text also highlights that

[...] By meeting a natural and permanent need for improvement, the review of the CEM was carried out under the prism of zeal for the deontological principles of medicine, one of the most important being absolute respect for human beings, with action in favor of the health of individuals and the community, without discrimination. (CFM, 2019, p. 7).

In this line, we highlight the deontological character present in the codes of ethics of different professions, elaborated by professional councils. For example, the Brazilian Bar Association (OAB, 1995) presents it in its Title I, Chapter I - on fundamental deontological rules:

Art. 1. The practice of law requires conduct compatible with the precepts of this Code, the Statute, the General Regulations, the Provisions, and the other principles of individual, social, and professional morality.

Art. 2. The lawyer, indispensable to the administration of Justice, is a defender of the democratic rule of law, citizenship, public morality, justice, and social peace, subordinating the activity of his Private Ministry to the high public function he exercises.

In addition to ethical principles and duties and rights, codes of ethics also indicate prohibited conduct, ethical infractions, and regulations for conducting an ethical disciplinary process, as cited in the document by the Federal Council of Engineering and Agronomy (CONFEA, 2020, p. 37):

Article 13. An ethical infraction constitutes any act committed by the professional that violates ethical principles, fails to comply with the duties of the office, practices expressly prohibited conduct, or violates the recognized rights of others.

Article 14. The typification of ethical infractions for disciplinary proceedings will be established, based on the provisions of this Code of Professional Ethics, in the manner determined by law.

CODE OF ETHICS FOR THE TEACHING PROFESSION

The adoption or not of the teaching ethics code has been a controversial topic. Silva, Ishii, and Krasilchik (2020) bring an overview of the aspects addressed by the literature relevant to the subject and some codes of teaching ethics in certain countries. The authors' idea was to bring up this controversy as a contribution to the professionalization of teachers, so that they can anticipate situations of ethical dilemmas that occur in the school environment, in their complexity and contradiction, giving these dilemmas a better direction; anticipation that may be present in their initial training.

A relationship between the quality of teaching and the quality of teachers' professional performance is recognized. Such a relationship ignores some variables that teachers cannot control such as low salary levels, economic and social inequalities, and devaluation of the social function of the school, among others (CASTILHO, 2018). Allied to these variables is teacher training, since, for a long time now, a low-value model has often been chosen, which is based on highly theoretical courses or on internships distanced from a reflective approach, which do not result from in the development of complex and diversified skills necessary for teaching.

Teacher training programs, both for Basic and Higher Education, have prioritized the cognitive domain and end up ignoring issues of the affective domain typical of school and academic daily life, many of them with a strong ethical component. In studies on the perception of teachers about their training, most of those surveyed understand that, throughout graduation, there is a greater emphasis on informative aspects and the predominant concern with intellectual and technical training; only a small portion of them understand that the courses place greater emphasis on the formative and creative aspects, providing the development of a more ethical and critical awareness of the world (SILVA, 2008).

In Brazil, when present, codes of teaching ethics are linked to the institutions where the teachers exercise their profession, unlike other professions, which have them in their way, without institutional ties. We emphasize that, when discussing ethical aspects of the teaching routine, we want to leave the territory of legality and reflect on the legitimacy of the discussions undertaken here.

Castilho (2018) states that each profession has a profile that distinguishes them from others. In the case of teaching professionalization, four aspects are considered: theoretical and practical mastery, ethical and deontological mastery, personal mastery, and prestige and social influence. The first three domains, in the words of the author, refer to the identity character, that is, to the set of specific knowledge and qualities. The theoretical and practical domain assumes the possession of knowledge related to the scientific area, which is the object of teaching, and its respective methodologies. The ethical and deontological domain requires a more in-depth approach, as it is a profession with responsibility in the process of building and forming the personality of children, adolescents, and young people. However, paradoxically, according to Castilho (2018), there is a considerable absence of theoretical production of a deontological nature in this domain, ending up being the direct regulation of the State that is imposed. In this respect, this study intends to fill part of this gap.

The author also points out:

Other professions with greater social relevance have deontological codes of mandatory observation, regulated by professional orders, which ensure respect for the respective fundamental values. But, as is known, this self-regulation does not exist for the teaching profession, as it is only protected by a statute that sets out contents and functional duties but is empty in terms of deontology. (CASTILHO, 2018, p. 221).

Thus, an in-depth debate, carried out by society, on the fundamental values of the teaching profession would be essential to increase respect for teaching and, at the same time, to create, among its professionals, an ethical conscience, on which the elevation also depends on the status of teachers (CASTILHO, 2018).

The personal domain emphasizes respect for the way of being of each professional, their individual qualities, the characteristics acquired through experience, their intellectual trajectory, and the permanent reflection on their professionalization. As the teaching profession has a relational component of a pedagogical nature, the variable that stands out most in the personal domain is the example, according to Castilho (2018, p. 222), in teaching, “more than any other profession, of the positive side, as in the negative, the example is dominant”. This aspect of teacher professionalization is related to the social value of the profession. The same author indicates that the exercise of the teaching profession fulfills the right to education and the respective constitutive process of individuals and, in this sense, reveals its importance for society (CASTILHO, 2018).

Another aspect of professional autonomy is related to the degree of independence and responsibility of each one in the norms that regulate professional teaching practice, that is, in the case of teaching, autonomy is limited to didactics in the classroom. Castilho (2018) points out that such collective professional autonomy does not exist due to the absence of deontological and self-regulation references, as already pointed out, and the constant intrusive tendencies of the bureaucratic centralism of the State and its governments.

The fourth aspect stems from the others presented and refers to social status, which is expressed in salaries, prestige, and social influence. There is a diversity of professions, naturally, with different social recognitions. Generally, the degree of recognition is related to the relevance and responsibility of the profession, in this sense the teaching profession assumes prominence, as it responds to a basic human right: the right to education.

In this scenario, few researchers have been challenged or even dedicated, in their studies, to considering the ethical problems inherent in the teaching profession. Denisova-Schmidt (2016) highlights the challenge of maintaining academic integrity in the face of recurring situations, such as fraud in class attendance; undue substitution by colleagues or strangers in carrying out tests or assignments; plagiarism; use of bribes to facilitate admission to course programs; obtaining advance copies of exams and tests; use of unauthorized materials or tools during examinations; obtaining monographs or other documents over the Internet; presentation of false documentation. This reveals the pertinence of academic integrity as a current ethical dilemma and its place in the discussion on the code of ethics.

We routinely make ethical decisions, consciously or not, based on our values, which we do not identify. Faced with pluralism in society, which also affects ethical and moral aspects, it is to be expected that many do not share the same values, that is, many will disagree with our decisions, which may end up in conflicts. The ethical-moral approach can be “an aptitude for the peaceful resolution of conflicts” (CORTINA; MARTINEZ, 2005, p. 36). The origin of the conflict lies in the disharmony of subjective ends with the ends of the social group and the antagonistic interests of the different social groups; thus, “the novelty would consist in situating the moral scope preferably in that of the resolution of action conflicts, either at the individual level or at the collective level” (CORTINA; MARTINES, 2005, p. 37). Ferreira (2010, p. 28-29) adds that conflict is part of the human condition, constituting “a painful process of thinking about difference as a possibility”.

Considering that there are no ready-made answers to the complicated situations faced by a teacher, what can be offered are ways of thinking about such situations.

It should be noted that not all ethical issues are ethical dilemmas. According to Anderson (2001), individuals engage in clearly illegal or unethical acts. A teacher who discards the negative evaluations of his students and presents only the positive ones is an example of an unethical act. From this example, we can conjecture: must the dilemma have occurred earlier, when the professor considered submitting all the evaluations or discarding the negative ones, to be better considered by the institution?

Thus, the dilemma implies a choice between two or more equally balanced alternatives for solving an ethical problem. Dilemmas are considered thorny problems, without clear paths, and place the individual in a situation of uncertainty. They only occur when reality requires the choice of principles that the subject considered fundamental for his life, that is when these principles are placed under suspicion in situations in which the subject chose between two or more principles and values that he considered immutable, fundamental to his exercise of autonomy (FERREIRA, 2010). The dilemma can arise in several contexts, such as the professional context.

Anderson (2001) suggests an approach for teachers to face ethical dilemmas. The first step is to identify the educator's values. To this end, the author proposes two questions: when we violate certain values, will we feel sadness or guilt? What values do we consider most important? (ANDERSON, 2001).

According to the author, the singular principle that should guide all attitudes and decisions of teachers is that of basic respect for students, considering their intellectual diversity, predisposition to learning, honesty, and integrity, and avoiding stereotypes and prejudices, because, indistinctly, everyone deserves respect (ANDERSON, 2001).

Anderson (2001) also categorizes decision-making as absolutist or relativist postures. For the author, the educator who respects the rules without considering the possibility of changing them or the existence of exceptions, regardless of the context, is absolutist, with arguments based solely on justice, in a way of actively maintaining, sustaining and justifying the social order in a certain kind of legalism. On the other hand, relativists consider the context and individual circumstances to decide. It may be that the relativist would be close to decisions based on principles, characterized by Kohlberg (1984) as the post-conventional level. At this level, there is a clear awareness of the relativity of personal values and an emphasis on procedural rules in the search for consensus that must be respected, because they are part of the social contract. The sociomoral perspective adopted by the subject is that of the relative priority of the individual concerning the social. The relativist considers the moral and legal points of view but recognizes that sometimes these clash and do not integrate easily.

It should be noted that, to treat all students with an attitude of basic respect, an ethical teaching attitude must be necessary, but not enough to resolve ethical dilemmas. What cannot be ignored is the power that the teacher has and how his actions affect the students' lives, whether through words or attitudes.

In addition to basic respect for students, so that teachers do not abuse this power, other principles can be applied when ethical dilemmas and problems are confronted. Some of these principles are autonomy, beneficence, and justice, which are related to the traditional theoretical current of Bioethics, called principialist.

Another essential principle that can be applied when the teacher faces ethical dilemmas is truthfulness, in which there is no possibility of an educator being seen as an ethical individual. Even though there are several interpretations of what the truth is, a compromise is required, differentiating what we have seen from what we think or believe, and preventing a fact from becoming distorted or misrepresented.

In a study carried out by Silva, Ishii, and Krasilchik (2020), the implications of the existence or not of codes of ethics for educators were discussed, highlighting an overview of these aspects addressed by the literature and by existing teaching codes of ethics in Brazil and abroad, which allowed the authors to point out that the implementation or not of these codes is a controversial topic.

Thus, the following problem emerges, which the present study sought to answer: what are the perceptions and opinions of teacher educators, Basic Education teachers, and future teachers about the existence of a code of ethics for the teaching profession? In this sense, the investigation aimed to analyze perceptions and opinions about the existence of a code of ethics for the teaching profession, among the following groups: teacher educators, Basic Education teachers, and undergraduate students. For this purpose, the opinions of the mentioned groups were collected, and based on categories, we undertook an analysis of the participants' justifications.

METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURES

This research is characterized as a qualitative, exploratory, and descriptive study. To obtain the data, online questionnaires (Google Forms) were applied, containing four objective questions, aiming at characterizing the participant, and an open question about the opinion on the existence of a professional teaching code of ethics (CE). The characterization of the participants aimed to verify whether there is a relationship between the different levels of professional performance and opinions about the existence of a code of ethics.

Because it is an exploratory and qualitative study, the determination of the sample size was provisional (MINAYO, 2017). The number of interviewees presented may vary according to the principles of empirical saturation and theoretical saturation (FONTANELLA et al., 2011; MARSHALL et al., 2013), which we used in this study. Empirical saturation occurs when it is confirmed to obtain categories of information that can answer the research questions and that are subject to deepening. Theoretical saturation consists of the observation that the elements of the analysis presented by the interviewees are repeated as the data are collected.

The limits of the analysis were defined as the questionnaires were answered and analyzed according to the identified categories.

The respondents - research participants -, totaled 53 people, were selected among teachers who had the following characteristics: work in Basic Education or work in higher education, in teacher training courses, or graduates. The invitation to participate took place online, in which the objectives and procedures of the research were clarified.

All respondents participated in a free and informed way. In compliance with the proper ethical procedures for research involving human beings, the questionnaire presented a brief introduction, to clarify its purposes; and the Informed Consent Form (ICF) was offered to the participants, who were asked to read the Term before answering the questionnaire, guaranteeing its voluntariness and confidentiality.

It should be noted that the research project was submitted to the Ethics Committee, and approved by it3.

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

The data collection was carried out between August and September 2020 and had the participation of 53 people. The instrument for collecting information was made available in the Google Forms application and disseminated via e-mail, based on contacts with different working groups in the education of the researchers.

The data presentation is organized according to the training level of the participants and their professional activity: 9 undergraduates, 26 Basic Education teachers, and 18 teacher educators (Table 1).

Table 1 - Research Participants

| Professional activity | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Undergraduates (L) | 9 |

| Basic Education Teachers (P) | 26 |

| Teacher educators (FP) | 18 |

| Total | 53 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The length of professional experience of the participants (Table 2) shows the diversity of experience in the teaching activity: undergraduates who do not work in the classroom (3); graduates who already work as teachers (6); Basic Education teachers with up to 15 years of experience (12) or more (14); and professionals who work in teacher training, with more than 15 years of experience (10).

Table 2 - Time teaching, in years

| Working time (years) | Undergraduates | Basic Education Teachers | Teacher educators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not applied | 3 | - | 2 |

| 1 to 5 | 6 | 2 | 3 |

| 6 to 10 | - | 5 | - |

| 11 to 15 | - | 5 | 3 |

| 16 to 20 | - | 6 | 1 |

| 21 to 25 | - | 1 | 2 |

| More than 25 | - | 7 | 7 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Regarding academic training, most Basic Education teachers (17) completed postgraduate studies, as well as teacher educators (13) - the number of PhDs (7) stands out.

Table 3 - Academic background

| Education level | Undergraduates | Basic Education Teachers | Teacher educators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete higher education | 9 | - | - |

| Graduated | - | 9 | 5 |

| Graduate/specialization | - | 10 | 2 |

| Graduate/Master's | - | 5 | 4 |

| Graduate/PhD | - | 2 | 7 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Quanto à atuação nas redes de ensino, trabalham apenas na rede pública de ensino 19 participantes, enquanto 16 trabalham apenas na rede privada. Dos demais, 16 atuam tanto na rede pública quanto privada, e 2 não responderam.

As for work in education networks, 19 participants work only in the public education network, while 16 worked only in the private network. Of the others, 16 work in both the public and private network and 2 did not respond.

Table 4 - Education area in which they operate

| Teaching area | Undergraduates | Basic Education Teachers | Teacher educators | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public area only | 2 | 15 | 2 | 19 |

| Private area only | 2 | 5 | 9 | 16 |

| public and private area | 4 | 6 | 6 | 16 |

| They did not answer | 1 | - | 1 | 2 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Again, and to make things easier, below is the context of the key question of the data collection instrument for this research:

“Ethical dilemmas are thorny problems and place the individual in a situation of uncertainty that implies a choice between two or more equally balanced alternatives for a situation that requires decision-making. Facing ethical dilemmas and making decisions are frequent actions in teaching. Studies show that teacher training programs, both for Basic Education and for Higher Education, have prioritized the cognitive domain and end up ignoring issues of the affective domain typical of school and academic daily life, many of them with a strong ethical component. Several professional areas have their code of ethics, without institutional ties, such as the one that regulates the performance of doctors, engineers, and lawyers, among others, and guides decision-making.

We want to know: should there be a code of ethics for the teaching profession? Please, justify it. Your opinion is very important for the research we are conducting.”

The answers presented by the participants indicated, in most cases, agreement or disagreement, through a “yes” or a “no”, for the existence of a code of ethics. In some, although the answer was not explicit, we interpreted the participant's position by the justification he presented. (Table 5).

Table 5 - Number of “yes” and “no” answers to the key research question; and number of answers without justification, by category of participants

| Participants | Yes | No | Without justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Undergraduates | 8 | 1 | - |

| Basic Education Teachers | 25 | - | 2 |

| Teacher educators | 18 | 1 | 3 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Among the 53 research participants, one student stated that he does not agree with the existence of a code of ethics for teaching activities. In his words:

“I believe that it is not necessary to have rules, norms, or laws to be followed so that the subject acts ethically. Perhaps, however, it would be interesting to seek to develop ethical and autonomous attitudes (so that they do not act correctly only when being observed) in Education professionals.” (L6)

The second negative answer to the question was given by a teacher trainer:

“No, because I believe that all professions have a code of ethics, including professionals in the area of pedagogy.” (FP9)

A Basic Education teacher did not explain his answer (yes or no), but pointed to the need to understand the differences between “professional rules” and what would be a code of ethics:

“There are professional rules. Ethics is more than a rule of social interaction. That is the place of morality.” (P2)

We tend to interpret the answer as “no” to the code of ethics - as professional rules. As it is about morality, the code of ethics should be part of the reflective teaching practice and not a document to be followed. We also received 5 answers that did not justify the existence of a code of ethics: 2 among Basic Education teachers and 3 among teacher educators.

In general, the “yes” answers to the central research question revealed three categories of reasons for the need and existence of a code of ethics for the teaching profession: (A) it would be a guiding instrument in different situations; (B) would promote professional credibility and professional development; (C) would respond to the demands of the educational scenario. At the same time, many justifications presented emphasized that the nature of the teaching work would already imply reflections on practice, in decision-making (D) and that there should be a concern about who would elaborate this code of ethics and how it would be used (E), thus emerging two more categories.

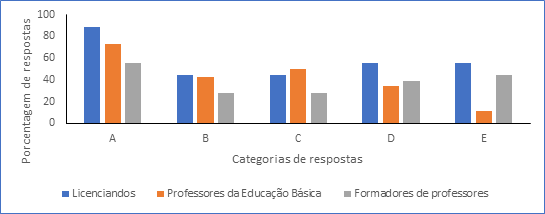

The categories of analysis mentioned above appear in different frequencies in the studied groups. Graph 1 shows, in a comparative way, the frequencies in which the categories (A, B, C, D, and E) are presented in the participants' responses.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Percentage of responses, Response category: Undergraduates, Basic Education Teachers, Teacher educators

Caption: A) guiding instrument; (B) promotion of credibility and appreciation and professional development; (C) meeting the demands of the educational scenario; (D) the nature of teaching work implies reflections on practice, in decision-making; (E) concern about who would elaborate the code of ethics and how it would be used.

Graph 1 - Comparison between the answers presented by the three participating groups

Proportionally, there are important differences in the answers presented by the studied groups. In general, undergraduates and Basic Education teachers indicate the importance of a code of ethics that guides teaching practice (89% and 73%, respectively) and its importance for valuing it as a profession (44% and 42%). Also, they indicate the need to create conditions for coordinated pedagogical work or be guided by some principles or values that do not seem to be well established, either in their initial training or in the exercise of the profession (44% and 50%) - category C. In this way, there could be greater recognition of the teaching activity as a profession, through the establishment of guidelines that go beyond institutional limits. These aspects also appear in the justifications of teacher educators but are associated with other aspects related to the existence of this code of ethics.

We also highlight the differences found in the justifications of Basic Education teachers and other groups about who would elaborate a code of ethics for the teaching activity and how it would be used. This is a concern pointed out by 56% of undergraduates, 44% of teacher educators, and only 12% of Basic Education teachers. These differences may indicate different perceptions about school issues. Teachers working in the classroom may be more familiar with the situations in which ethical dilemmas manifest themselves. Also, they note the lack of collective reflection on the guidelines, or coordination, which gives greater support to the decisions taken, which does not mean that they are not concerned with the use of such an instrument.

In any case, undergraduates seem to indicate the need for discussion about dilemmatic situations, as they perceive limits in their education when they are faced with situations experienced in school everyday life.

Teacher educators are also concerned with the way ethical dilemmas are being addressed in teaching practice, emphasizing the importance of establishing a code of ethics and not using it as an instrument of coercion or limitation of discussions about school practices.

Below are the analyzes arising from each category presented above, being exemplified by some testimonies of the survey respondents:

A - Need for a guiding instrument for teaching

This was the most common category in all the studied groups, which indicates the importance or need for a guiding instrument to guide the teaching performance, as exemplified in the testimonies of the undergraduates:

“[...] would act as an effective guide for professionals at the beginning of their careers.” (L2)

“Having a specific code of ethics, it would be possible to have a more objective direction to be followed, which would also be a guide to minimize doubts and uncertainties when making a decision.” (L8)

“[...] a Code of Ethics can be an excellent start for this. Furthermore, there is a great lack of specific methods and dealings for teachers, opening room for errors that can bring irreversible negative marks on students’ lives.” (L4)

We found that, among the undergraduates, the presence of the code of ethics leads to the idea of a guiding instrument to help the decision-making exercise, minimizing its uncertainties. For some, such as L4, the lack of this instrument can lead teachers to unfair practices, which may harm their students, which is a justification that will also be presented by teachers in service. This perception highlights the initial training phase in which the undergraduate students. With this, we recognize the complexity of teaching, and we consider it important to include this topic as an object of discussion in initial training courses, as well as the importance of mentoring, in its role of helping beginning teachers.

The justification of teachers in service gains new nuances, as can be seen in the following statements:

“[...] we would have a guideline to guide us in some decision-making, making clear the responsibilities of each individual.” (P6)

“Yes, very important to give parameters in teaching performance, in the face of specific cases, and to guarantee students confidence in educators.” (P10)

“Yes, it must exist to guide some behaviors of teachers that are inappropriate.” (P13)

These identify the CE as a guiding instrument for decision-making to avoid undesirable teaching behavior, as well as to reinforce a relationship of trust between students and teachers. In addition, they identify CE to face inequality from a perspective of inclusion:

“[...] if this code existed with clear, objective, practical and reflective rules, education would walk on a path without inequalities... everyone, regardless of race, social class, religion, and political choice, would have access to literate culture, basic and superior.” (P20)

As already pointed out, the principle that should guide teachers' attitudes and decisions is basic respect for students, considering them in all their inequalities, and avoiding stereotypes and prejudices (ANDERSON, 2001). Thus, the CE of certain countries, such as New Zealand, consider the inclusion of minorities, about the natives of that country (SILVA, ISHII and KRASILCHIK, 2020).

We noticed other types of justification among teacher educators about the idea of the CE being a guiding instrument for their work activities:

“[...] I agree with the creation of a code of ethics. Justification: - Complexity of the teacher's work. We face many dilemmas. Often, the definition of what could be 'ethical' assumes a more systemic and comprehensive look. Furthermore, our action is not neutral.” (FP3)

From the statement, we recognize the complexity of the teaching profession, in addition to the non-neutrality of its performance, as it is a profession whose activity is the relationship between people/individuals.

For participant FP6, the CE could be a form of protection for professionals in the face of unfair accusations, guiding teaching practice in dilemmatic situations, as also pointed out by FP8:

“Since we exercise a profession where contact with other people is essential, it may be worth having some guidelines that would guide behavior and practices. These could both protect professionals (for example, from unfounded accusations) and establish norms and rules of practice [...].” (FP6)

“[...] A document, without an institutional link, could at least guide teaching practice, in many delicate situations, which can be called 'dilemmas'.” (FP8)

B - Promoting credibility and valuing and professional development

In addition to the aspects related to the need to guide teaching actions regarding the school routine, the demand for professionalization ratified by a CE is also pointed out as an aspect that could contribute to the appreciation and development of the teaching activity.

For undergraduates, the idea of the credibility of the teaching profession, offered by the CE, in addition to unifying professional teachers, gives the legitimate idea of a corporate feeling to teachers, including the defense of their rights. L4 recognizes the role of Education and its professionals as a matter of the State and not of the government, parties, or unions, despite the importance of the latter. In his perception, a CE not linked to such institutions would be a start.

“Yes, there must be. This will be helpful in unifying teachers, and thus education. Education in our country must cease to be partisan, depending on the rulers in power and order. A Code of Ethics can be an excellent start for this [...].” (L4)

As previously presented, the absence of deontological references and self-regulation in teacher professionalization can lead, according to Castilho (2018), to constant intrusive tendencies of the bureaucratic centralism of the State and its governments, as observed in the following testimonies:

“[...] just like other professions [,] teaching demands choices and decision-making that directly involve other individuals (students), having a code of ethics[,] in addition to giving greater credibility for the professional dedicated to education[,] acting as an effective guide for professionals at the beginning of their careers.” (L2)

“I think so, as it is essential that there be a group of professionals in the same area to represent the profession and with the ability to make decisions, guide paths, and defend the rights of each professional in the area.” (L9)

For working teachers, strengthening the image of the profession is a justification for the existence of a CE. In addition to receiving support from the category, it gives representation to the demands of the profession in its dignity, in the face of its growing social devaluation.

“I think it can strengthen our image.” (P6)

“I think that by obtaining a code of ethics we will have support from the category, in addition to establishing some rules and situations that can save and deprive teachers of the wear and tear and problems that the profession imposes.” (P9)

“[...] in this way, a code of ethics for the teaching profession would be useful to guide the acts of the teaching staff (in all their instances, as teachers, directors, supervisors, and managers), to give a more representative character so this profession is valued and respected as a dignified job, and not a 'little job' to supplement income.” (P11)

As already stated, the devaluation of the school's social function has strong implications for the relationship between the quality of teaching and the quality of teachers' professional performance, presenting some variables, which are low salary levels and the context of economic inequality. We noticed that, for some research participants, the CE would be a way of coping with this reality.

For teacher educators, the CE gains importance as it brings seriousness to the profession, valuing it, based on minimum quality criteria in its practice. It is important to highlight the denunciation of certain scrapping of teacher training, opening spaces for non-educational practices, and giving the impression that, in the words of the participant, “anyone can teach” and that “anyone who teaches is a teacher” (FP15). In addition, the CE would be important for the teaching corporation, offering an identity to this profession and adding political aspects to it.

“The elaboration of a specific ethical code for [the] teaching profession is extremely important, since, like the other codes, it regulates the performance in this profession, brings seriousness to the profession, and stipulates a minimum level of quality. I say this because [,] many times, the profession is devalued for not presenting solid and well-founded bases in social and ethical issues, opening a lot of space to practices that are not educational, giving the impression that 'anyone can teach' and that 'anyone who teaches is a teacher'.” (FP15)

These positions reveal aspects of everyday school life that contribute to the precariousness of the teaching profession. The existence of a code of ethics is seen by teachers to legitimize their pedagogical authority and build a professional profile for the category.

“[...] I think it is very important to have a code of ethics for the teaching profession, as we would have a guideline in some decision-making, making clear the responsibilities of each individual. I think it can strengthen our image.” (P6)

“[...] I understand that there must be a code of ethics for teachers. I think that by obtaining a code of ethics we will have support from the category, in addition to establishing some rules and situations that can save and deprive teachers of the wear and tear and problems that the profession imposes.” (P9)

“Yes, very important to give parameters in teaching performance, in the face of specific cases [,] and to guarantee students confidence in educators.” (P10)

“Teaching work requires an ethical exercise, which few can understand, because [teachers] suffer and are corrupted by hierarchical actions, which manipulate and cease the work of others, in exchange for prestige, jealousy or to reach internship levels, in exchange for economic benefits.” (P11)

C - Meeting the demands of the educational scenario

The participants also highlighted the possibility of the code of ethics for education professionals meeting current political and social demands, which require new demands from their profession, and supporting teachers whose training did not privilege ethical aspects of teaching practice:

“I understand that there are new demands for work with education and that most professionals still do not understand the new social functions that this job entails.” (P12)

Sá (2001) points out that the emphasis on individualism in the world of work can increase the risk of ethical transgression, pointing to the importance of ethical norms, as is also observed in the perceptions of the participants:

“There must be a code of ethics [,] because otherwise the door to arbitrariness is left open.” (P3)

“The fragile training of education professionals puts the area in a situation of attitudes guided by personal values and, in many cases, unethical ones.” (P4)

For the teacher trainer participants, the CE would fill an existing gap in the training of new and inexperienced teachers, who still do not know the practice:

“[...] the Code of Ethics is valuable to the extent that many teachers do not know how to effectively deal with certain situations, mainly because many do not have the necessary experience or do not yet have education training [,] since they come from other areas of knowledge. (FP4)

Such participants ratify the idea that the teacher, concerning the student, has a certain power; so the CE could promote the singular principle that should guide teaching postures, which is basic respect for students, considering them in their diversity (Anderson, 2001), avoiding any types of stereotypes:

“Yes, extremely important indeed. Education discusses many ethical issues, such as inclusion, awareness of bullying, distance learning as an accessible and democratic modality, and quotas for blacks, browns, indigenous peoples, and low-income individuals, among many others. However, in practice, the Professor assumes behaviors and postures that could be restrained if there were a code of ethics. Positions such as using the test as punishment, and pre-judging a certain student by his clothes, by his purchasing power, for example, are some of the attitudes that could be eliminated, through a code of ethics and the inclusion of the theme in the teacher training curriculum.” (FP14)

D - The nature of teaching work implies reflections on practice, in decision-making

The participants show that reflection, dialogue, and the need for ethical postures in the face of complex situations are part of the nature of teaching work. Here it is worth highlighting that the teaching profession, specifically its work, implies a relationship with the other, in this case, the student, and, in this sense, as already mentioned, should not disregard the deontological character that the CE can offer, as evidenced by some depositions:

“I believe so, since not everything should/can be applied in the classroom, with awareness by the teachers.” (L3)

“[...] it is a profession that deals directly with human beings in the process of formation, and this implies having a conscious, critical and responsible attitude, which has as principles respect for freedom of expression and thought, respect for human rights, in particular, of children and adolescents in training.” (P1)

“I understand that there are new demands for work with education and that most professionals still do not understand this job’s new social functions. A code of ethics would be a possibility to guide them in their dilemmas and standardize professional postures.” (P12)

“Yes, because [,] according to our patron Paulo Freire, there is no way to dissociate ethics and 'right thinking' from teaching.” (P17)

“I think there are two dimensions to this answer. One is related to teacher autonomy and concerns the incorporation of discussions on professional ethics as a transversal curricular component in teacher education, strengthening internal ethics capable of guiding teachers in their daily decisions. Another relates to the existence of a code, of a regulatory nature and, therefore, external to the subjects (connected [,] therefore [,] to an external, heteronomous control).” (FP1)

“Ethics is inherent in the act of educating. Therefore, I think that in theory, you would not need a separate code. However, we live in complex times in which the possibilities for action can be interpreted in very different ways and perspectives.” (FP5)

In the testimonies, the identity characteristics of the profession that can be advocated by the CE are evident, that is, a set of practical knowledge, among them, ethical reflection on and in action based on principles, such as respect for human rights and to freedom of expression and thought, essential to a learning environment. In addition, as it is a profession with a particular responsibility, as it participates in the training process of children, young people, and adolescents, teaching requires greater care in the ethical domain, as pointed out by Castilho (2018).

E - Concern about who would elaborate on the teaching code of ethics and how it would be used

Another aspect that deserves attention, according to the participants of this research, concerns who would elaborate a teaching ethics code and what is its purpose: guidance or control? Some testimonials, made by undergraduates, in-service teachers, and teacher educators, reveal this concern:

“Another important question is who will make this code of ethics, would it be another loophole to devalue the profession even more or not?” (L1)

“[...] I believe that a code of teaching ethics made by teachers, for teachers, and with a representative portion of these professionals, would probably reduce possible problems and maximize benefits. In short, I think it is ‘dangerous’, a shot in the foot depending on how it is done, by whom it is done, and even for whom it is done.” (L5)

“[...] this 'code of ethics' must be built by several hands, to try to cover the entire faculty [,] which is very heterogeneous. (P11)

“The elaboration of a code of ethics for the teaching profession is important, but it is necessary to ask what philosophical bases it would be based on.” (FP2)

“There should be a code of ethics on which professors could reflect. But, built by teachers in the most democratic way possible.” (FP5)

We understand this concern as legitimate, since a document of such magnitude, which is a code of ethics, would be, in our view, a possible form of concentration and exercise of power by whoever conceived or elaborated it, whether in the form of control, under the idea of maintaining a heteronomous atmosphere; thus, we recognize the complexity of this aspect. On the other hand, one of the ways of facing this absolute control (or minimizing the undertaking of such a task) would be to resort to what a democratic society intends to be, in this case, the community/society of teachers. Thus, a code elaborated by the teachers, in its various forms of representation, would be the first step. This step can be evidenced in the testimonies of undergraduates and professors in service. The philosophical basis required in the elaboration of a CE, highlighted by the FP2 participant, would be the second step, and, in this sense, such basis should be based on criteria to be respected in the teaching practice, which involve relationships with the student, with their parents and guardians, with all actors in the school community and with the cultural and legal contexts of the country.

Regarding the heteronomous relationships that the CE can establish, as already discussed, we can have teachers with more absolutist or relativist postures, and such postures are not a result of or independent of the existence of the CE, they are inherent to individuals. Thus, a teacher's relativist posture will consider the CE but will contextualize it to individual and singular circumstances in their decision-making exercise:

“[...] there must indeed be a code of ethics for the teaching profession, but in a more general context, because [,] as we deal directly with delicate issues of human beings, we need flexibility for decision-making, since each case is a different case and what applies to one may not be the best option for another.” (FP16)

“[...] I think it's important [,] in the first place, to listen to the student, even more so in times as difficult as we are currently. In general, the teacher's sensitivity and common sense should come first. [...] The code of ethics assists in guidance but does not cover all situations and their singularities.” (FP4)

Regarding the possibility of a certain “inhibition” of the teaching activity, some testimonies reveal this concern:

“[...] it's good to have, because, [sic] it would guide teachers, what is coherent or not, however, [sic] this would place the teaching area within a systematization.” (L1)

“[...] The code of ethics [...] should not be considered as a general prescription that imposes rules that are so dogmatic that they cannot pass through the sieve of the specific situation to be resolved.” (FP4)

In addition to the identified categories, data analysis allowed us to recognize other aspects of the studied phenomenon. One of them is that the results, in general, point to weaknesses concerning training and teaching activities.

Regarding teacher training, both initial and ongoing, the positive justifications for the existence of a teaching code of ethics reveal the lack of confidence by undergraduate students in dealing with dilemmatic situations in everyday school life.

“[...] the teaching action demands choices and decision-making that directly involve other individuals (students), thus [...] a code of ethics [,] in addition to giving greater credibility to the professional dedicated to[sic] education, together acts as an effective guide for professionals at the beginning of their careers.” (L2)

In addition, it is possible that their participation in internships, or even in teaching practice, reveals the predominance of attitudes that reflect personal and non-professional positions.

“[...] Furthermore, there is a great lack of specific methods and treatments for teachers, opening up room for errors that can bring irreversible negative marks on students’ lives.” (L4)

On the other hand, regarding teaching, depending on how a code of ethics is developed and used, it can direct teaching to comply with professional rules, restricting it to a heteronomous perspective, which does not allow reflection on practice.

“In the case of the teaching profession, which faces a wide variety of contexts (socioeconomic, cultural, etc.), imposing guidelines seems to me to be something that can bring more problems than benefits.” (L5)

At the same time, teachers who work in teaching indicate the need for a corpus of teaching behavior since there seems to be a lack of clarity regarding the roles played by actors in the school environment.

“[...] I believe that a code of ethics is important for some situations that the teacher experiences, especially concerning [sic] the family, so that it is clear how the professional should behave.” (P5)

Fragilities in teacher training (initial and continuing) directly affect the quality of their professional performance. The feeling of disarticulation and collective commitment in the face of dilemmatic situations in teaching practice points to the need to review the objectives of teacher education. According to a teacher educator, it is necessary to consider the

“[...] complexity of the teacher's work. We face many dilemmas. Often, the definition of what could be 'ethical' assumes a more systemic and comprehensive look. Furthermore, our action is not neutral;

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

When we started the research, our attention was drawn to the perplexity, readiness, and availability with which the participants received and welcomed the central question of this work. Despite not being present in the answers to the instrument, the contacts before and after completing the form gave us the dimension of how this subject could give clues about teacher training, the recognition and appreciation of the teaching profession, and the implications of a possible existence of a code of teaching ethics. This is an important aspect to consider, as it raises the hypothesis that there is a lack of critical approaches to the subject, that is, a “damming” of this discussion, as already pointed out by authors in the area (CASTILHO, 2018).

The results of this investigation may bring significant contributions to teaching activities in teacher training courses and, according to the justifications of the three groups of respondents, clarify the reasons for the elaboration or not of a code of ethics for the teaching profession.

Among the positive justifications, both undergraduates and teachers and teacher educators indicate the need for an instrument to guide teachers' actions in the face of thorny situations, not discussed in training courses, which are part of the school routine, with serious implications for student development. On the other hand, there is concern about who would develop this instrument and how it would be used by educational institutions. The distrust in its purposes is based on the historical perspectives of the development of educational systems.

In any case, the results of this work point to the demand of undergraduate students, teachers, and teacher educators for training processes that favor aspects of guidance, reflection, and decision-making in everyday school situations, which directly or indirectly imply the quality of students' learning. These formative processes can lead to the need to elaborate a code of ethics or even other systematic interventions in the formative processes of teachers.

It is worth highlighting here the suggestions obtained in this research, in case the elaboration of a code of ethics is opportune:

To ensure the participation of teachers and other actors in the school community in the preparation of this document;

To guarantee its permanent (re)construction, through reflections on the principles and values on which it will be based;

To prevent it from being used as rules of professional conduct, that is, the code of ethics would not simply be an object of legality but also of legitimacy.

The inclusion of these themes in teacher training courses is essential so that they can actively participate in the continuous construction of a possible code of ethics or reflection practices on the principles and values that guide their profession.

Preparing to face dilemmatic situations in the relationship with students, colleagues, and institutions is fundamental for the full exercise of the teaching activity. Thus, we argue that the presence of the theme “teacher code of ethics” in teacher training curricula is fundamental since trainees/licensing students need to be warned that their future attributions, in their daily work, are not only limited to teaching but also involve the responsibilities arising from issues that arise in the school context and the impact of their decisions on students, teachers, and institutions.

REFERENCES

ANDERSON, Dinah. Values and Ethics. In: ROYSE, D. Teaching tips for College and University Instructors. A practical Guide. A Person Education Company: Needham Heights, MA, 2001. [ Links ]

CASTILHO, Santana. Para uma ética prática da profissão docente. In: NEVES, Maria do Céu P.; JUSTINO, David (coord.). Ética Aplicada - Educação. 1. ed. Lisboa: Edições 70, 2018, 332 p. [ Links ]

CONSELHO FEDERAL DE ENGENHARIA E AGRONOMIA (CONFEA). Código de Ética do Profissional da Engenharia, da Agronomia, da Geologia, da Geografia e da Meteorologia. 13. ed.ÉTICA CONFEA/CREA, CDEN, 2020. p. 37. Disponível em: https://www.confea.org.br/midias/uploads-imce/Cod_Etica_13ed_com_capas_para_site.pdf. Acesso em:26 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

CONSELHO FEDERAL DE MEDICINA (CFM). Código de Ética Médica. Resolução CFM no 2.217/2018, de 27 de setembro de 2018, modificada pelas Resoluções CFM n. 2.222/2018 e 2.226/2019. Brasília: Conselho Federal de Medicina, 2019. 108 p. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://portal.cfm.org.br/images/PDF/cem2019.pdf . Acesso em:26 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

CORTINA, Adela; MARTINEZ, Emilio. Ética. São Paulo: Loyola, 2005. [ Links ]

DENISOVA-SCHMIDT, Elena. The Global Challenge of Academic Integrity. International Higher Education, n. 87, Fall 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://brunner.cl/2016/09/international-higher-education-number-87/ . Acesso em:16 ago. 2018. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Amauri C. A morada da ética aplicada. Cadernos da Escola do Legislativo, Belo Horizonte, v. 12, n. 19, p. 17-35, jul./dez. 2010. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://cadernosdolegislativo.almg.gov.br/ojs/index.php/cadernos-ele/article/view/238 . Acesso em:6 mar. 2019. [ Links ]

FONTANELLA, Bruno J. B.; LUCHESI, Bruna M.; SAIDEL, Maria Giovana B.; RICAS, Janete; TURATO, Egberto R.; MELO, Débora G. Amostragem em pesquisas qualitativas: proposta de procedimentos para constatar saturação teórica. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro, v. 27, n. 2, p. 389-394, fev. 2011. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/csp/a/3bsWNzMMdvYthrNCXmY9kJQ/?lang=pt . Acesso em:7 jun. 2022. [ Links ]

KOHLBERG, Lawrence. The Psychology of Moral Development - essays on moral development. London: Harper & Row Publishers, 1984. [ Links ]

LA TAILLE, Yves de. Moral e Ética: dimensões intelectuais e afetivas. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2006. [ Links ]

MARSHALL, Bryan; CARDON, Peter; PODDAR, Amit; FONTENOT, Renee J. Does sample size matter in qualitative research? a review of qualitative interviews in research. Journal of Computer Information, London, v. 54, n. 3, p. 11-22, 2013. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.scirp.org/%28S%28351jmbntvnsjt1aadkposzje%29%29/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=2564793 . Acesso em:7 jun. 2022. [ Links ]

MINAYO, Maria Cecília de S. Amostragem e saturação em pesquisa qualitativa: consensos e controvérsias. Revista Pesquisa Qualitativa, São Paulo (SP), v. 5, n. 7, p. 01-12, abr. 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://editora.sepq.org.br/rpq/article/view/82 . Acesso em:10 jun. 2022. [ Links ]

ORDEM DOS ADVOGADOS DO BRASIL (OAB). Conselho Federal. Código de Ética e Disciplina da OAB. Diário da Justiça: seção 1, Brasília, DF, p. 4000-4004, 1 mar. 1995. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.oab.org.br/content/pdf/legislacaooab/codigodeetica.pdf . Acesso em:26 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

SÁ, Antonio L. Ética Profissional. 4. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2001. [ Links ]

SILVA, Paulo F. Bioética e valores: um estudo sobre a formação de professores de Ciências e Biologia. 2008. 214 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2008. [ Links ]

SILVA, Paulo F.; ISHII, Ione; KRASILCHIK, Myriam. Código de Ética Docente: um dilema. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 36, jun. 2020. ISSN 1982-6621. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698215216. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://educa.fcc.org.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-46982020000100401&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt . Acesso em:12 ago. 2022. [ Links ]

1The translation of this article into English was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES/Brasil.

Received: September 02, 2022; Accepted: March 12, 2023

texto en

texto en