Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.39 Belo Horizonte 2023 Epub 15-Nov-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469840565

Relacionado con: 10.1590/SciELOPreprints.4436

ARTIGO

THE EDUCATION OF DEAF PEOPLE IN BRAZIL: AN ANALYSIS OVER 20 YEARS (2002-2022) AFTER THE PUBLICATION OF THE LIBRAS LAW

2Universidade Federal do ABC (UFABC), Sandro André, São Paulo (SP), Brasil

The education of deaf and hearing impaired people was sometimes marked by the phase of exaltation, sometimes by exclusion, which negatively impacted the entry of these people into the most diverse educational spaces. In view of this scenario, legislation was created so that the rights and human dignity of all were guaranteed. Thus, the objective is to analyze which changes Law No. 10.436/2002, popularly known as the Libras Law, provided in the education of deaf and hearing impaired people in 20 years (from 2002 to 2022), based on the statistical synopses of educational censos.Descriptive, exploratory and qualitative research is used as methodology. The analysis showed that, in these 20 years of the Libras Law, many advances have occurred, from the increase in the number of deaf and hearing impaired students in basic and higher education to the value of the Brazilian Sign Language (Libras) in the most diverse spaces of society and guarantees in relation to health. However, we are still far from an effective proportion of this public in Brazilian education, when analyzing the demographic census data.

Keywords: Libras; legislation; hearing impairment; deafness

A educação das pessoas surdas e com deficiência auditiva foi marcada ora pela fase da exaltação, ora pela da exclusão, o que impactou de forma negativa o ingresso dessas pessoas aos mais diversos espaços educacionais. Diante desse cenário, legislações foram sendo criadas a fim de que o direito e a dignidade humana de todos fossem garantidos. Objetiva-se, assim, analisar quais mudanças a Lei N.º 10.436/2002, conhecida popularmente como Lei de Libras, proporcionou na educação das pessoas surdas e com deficiência auditiva em 20 anos (de 2002 a 2022), com base nas Sinopses Estatísticas dos censos educacionais. Utiliza-se, como metodologia, a pesquisa descritiva, exploratória e de natureza qualitativa. A análise proporcionou vislumbrar que, nesses 20 anos da Lei de Libras, muitos avanços ocorreram, desde o aumento no ingresso dos estudantes surdos e com deficiência auditiva na educação básica e educação superior até a valorização da Língua Brasileira de Sinais (Libras) nos mais diversos espaços da sociedade e as garantias em relação à saúde. No entanto, ainda estamos distantes de uma proporção efetiva desse público na educação brasileira, quando analisados os dados do censo demográfico.

Palavras-chave: Libras; legislação; deficiência auditiva; surdez

La educación de las personas sordas e hipoacústicas estuvo marcada a veces por la fase de exaltación, a veces por la exclusión, lo que impactó negativamente en el ingreso de estas personas a los más diversos espacios educativos. Ante este escenario, se estaban creando leyes para que se garantizaran los derechos humanos y la dignidad de todos. El objetivo es, por lo tanto, analizar qué modifica la Ley N° 10.436/2002, popularmente conocida como Ley Libras, prevista en la educación de las personas sordas e hipoacústicas en 20 años (de 2002 a 2022), con base en la Sinopsis Estadística de censos educativos. Se utiliza como metodología la investigación descriptiva, exploratoria y cualitativa. El análisis permitió vislumbrar que, en estos 20 años de la Ley Libras, ocurrieron muchos avances, desde el aumento de la matrícula de estudiantes sordos y con deficiencia auditiva en la enseñanza básica y superior hasta la valorización de la Lengua de Signos Brasileña (Libras). en los más diversos espacios de la sociedad y garantías en relación con la salud. Sin embargo, todavía estamos lejos de una proporción efectiva de este público en la educación brasileña, cuando se analizan los datos del censo demográfico.

Palabras clave: Libras; legislación; hipoacústicos; sordera

INTRODUCTION

In 2022, Libras Act No. 10436 of 24 April 2002 will complete 20 years of its approval. It was sanctioned by the then President of the Republic, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, and is popularly known as Brazilian Sign Language (Libras Act) as a legal means of communication and expression, as well as provided about other resources of expression associated with it (BRASIL, 2002). According to Brito (2013, p. 206), "the legislative process that gave rise to the Libras Act began on June 13, 1996, when Senator Benedita da Silva, from PT-RJ, presented, in the plenary of the Federal Senate, the Senate Bill No. 131/1996 (PLS No. 131/96)". The initial negotiations, according to the author, occurred in 1993, "when leaders of this organization [Feneis] and other movement allies presented on behalf of the Brazilian deaf community the demand for officialization of Libras” (BRITO, 2013, p. 207).

This law is relatively brief, consisting of five sections and two subsections. In short, it recognizes the Brazilian Sign Language and explains what it means, ensures the dissemination and use and brings as a guarantee the receipt of care and appropriate treatment regarding health and, in Section 4 of the Libras Act, talks about the mandatory nature of the discipline of Libras in some courses (training courses for Special Education, Speech-Language Pathology and Teaching, in their medium and higher levels), also clarifying that Libras cannot replace the Portuguese language in written form. The last section deals with the law enacted (BRASIL, 2002).

Barely three years after the published Law No. 10436/2002, is enacted Decree No. 5626 of December 22, 2005, which regulates the new law studied here, in addition to Section 18 of Law No. 10498 of December 19, 2000. In the aforementioned decree, there is a whole detailing that the Law of Libras did not bring in its sections that impacted even more directly on the education of deaf people in Brazil from 2005. Thus, several developments were caused by virtue of the law and the decree mentioned.

Legislation prior to 2002 also covered deaf people. Among them are the Brazilian Special Education Policy of 1994, the National Education Guidelines and Bases Act (Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional -Law No. 9394/1996), the Notice No. 277/1996, Decree No. 3298/1999, Decree No. 3956/2001 and Law No. 10172/2001. However, neither of these legal provisions there was a specific legislation and that covered in a direct way the deaf people in Brazil and their language.

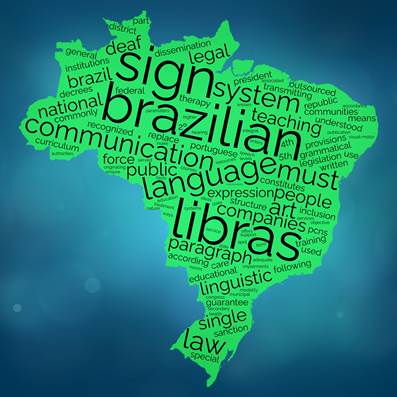

Towards a better understanding of Law No. 10436/2002, through a visual resource such as the word cloud, it is possible to "[...] identify the words that appear more, the higher the frequency, the greater will be its graphic or visual representation. It is a process considered simple, but a very imagetic way to understand what is analyzed" (ROCHA et al., 2021, p. 514). From this explanation, we present figure 1with the word cloud exposure of Law No. 10436/2002.

Source: Elaborated by the authors, based on the Libras Act of 2002.

Figure 1 Word Cloud of Law No. 10436/2002

Through the word cloud, displayed in Figure 1, it was possible to visually identify what else the law studied here talks about. In first place, there is the word 'language' (which appears seven times in the text), followed by Libras, communication and expression and others, since these are the words that make up such legislation and represent much of it. It is also noteworthy that the law is formed by more than 130 different words.

After 2002, other legislation was enacted and impacted the lives of deaf people, in a direct or indirect way. For example, in 2014, the Law No. 13005 was enacted, which approved the National Education Plan (PNE) and brought some strategies aimed at deaf people "to ensure the provision of bilingual education in Brazilian Sign Language - LIBRAS as a first language and in the written form of the Portuguese language as a second language, for deaf and hard of hearing students from 0 (zero) to 17 (seventeen) years" (BRASIL, 2014, without pagination).

In 2010, the Law No. 12,319 is published, which regulates the profession of Translator and Interpreter of Brazilian Sign Language (BRASIL, 2010), a professional of fundamental importance in the deaf community. The law also regulates other issues, such as training, attribution and the precepts for their performance, based on zeal, ethics and appropriate technique. In 2015, it is published the Law No. 13146, which established the Brazilian Inclusion of People with Disabilities Act (Statute of the Person with Disabilities), in which deaf people are covered in several aspects, including: right to bilingual education, Libras teaching, training of translators and interpreters of Libras, translation of public notices in Libras, some rights being acquired and others reaffirmed through such legislation. In this context, "the LBI [Lei Brasileira de Inclusão da Pessoa com Deficiência (Brazilian Law for the Inclusion of the Person with Disability)] presents the person with disabilities from the perspective of independence, autonomy and respect for their choices, not reducing them to a merely clinical and pathologizing issue" (ROCHA; OLIVEIRA, 2022, p. 3).

In 2017, the deaf became the subject of the essay of the Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (Enem-National High School Exam) and even won the right to have written proof, translated into Libras, in video format. For Junqueira and Lacerda (2019):

The Enem video test in Libras, available in digital format and on individual computers, is organized like the standard tests, with items prepared from the general competence matrix, but selected and adjusted to ensure a quality translation into Libras. (JUNQUEIRA; LACERDA, 2019, p. 30).

The impacts of a translation of the Enem exam into Libras are still little known and need further deepening in the analysis of the indicators (test scores and writing), which does not take away the merit of such an achievement and its importance for the Brazilian deaf community. It should be emphasized that this translation meets the right of all to accessibility to achieve equity in the assessment processes. We must also analyze and propose measures that can improve the correction process of the essays, as stated by the authors: "Enem in Libras represents a paradigm shift in the evaluation of people who have Libras as their first language, setting a recognition of the linguistic rights of this population”(JUNQUEIRA; LACERDA, 2019, p. 1).

Decree No. 10.502/2020 (BRASIL, 2020), repealed by the Unconstitutionality Action No. 6590, the National Policy for Special Education: Equitable, Inclusive and with Lifelong Learning (PNEE-2020) was established, which, despite not being specific for deaf people, is quite contemplative in relation to this public. According to Rocha, Mendes and Lacerda (2021), "deaf people seem to compose a separate group of students who make up the target audience of Special Education (PAEE) and, apparently, the PNEE-2020 would be configured as two policies in one, with different actions for two distinct groups [deaf people and PAEE]” (ROCHA; MENDES; LACERDA, p. 14). Therefore, it seems that deaf people were more contemplated than those with other disabilities in the aforementioned document. Even at the ceremonial launch of PNEE-2020, there was an investment in the use of Libras, used by the first lady and in the speech of several ministers, in an attempt to use the specific educational needs of deaf students to justify a change in the principles of Brazilian Special Education.

The education of the deaf is highlighted again in the national scene in 2021, specifically with the enactment of Law No. 14.191/2021, which amends Law No. 9394 of December 20, 1996 (Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional-Law of Directives and Bases of National Education), in order to provide for the modality of bilingual education for the deaf, comprising a modality of school education, beginning at zero years of age and extending throughout life. The Act brings from innovations and guarantees to aspects that reaffirm what had already been mentioned in other legislation. Again, in Figure 2, we will bring the word cloud for a better visualization of the aforementioned legislation and the words it carries, for a better view of what it deals with.

Source: Elaborated by the authors, based on the Libras Act of 2002).

Figure 2 Word cloud of Law No. 14.191/2021

Thus, the Law No. 10436/2002 paved the way for other legislations to consolidate legal guarantees, once understood as "favors", welfarism and aid to the less fortunate, in this case, the deaf and hard of hearing people. Analyzing the Law No. 10.436/2002 and its impacts on the education of deaf people 20 years after its publication is to have the possibility to rescue the past and portray the present, so that future research can bring comparative advances and setbacks that permeate a set of people who for years were little contemplated by public policies, but who organized themselves, as a deaf movement, in the fight for their rights and achievements (BRITO, 2013).

Accordingly, the objective of this research was to analyze what has occurred in deaf education after 20 years of recognition of the Libras Act in Brazil, especially through the main Brazilian statistics. The following question was the guiding question of the study: has the Libras Act contributed to wider access of deaf people to Brazilian educational spaces and in what proportions this occurred?

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACHES

This research adopted a quantitative methodology, using the statistical method, which is able to provide data and information about the target population, without considering them absolute truths, "but with a high probability of being true" (GIL, 2008, p. 17), so as to draw an overview of the contributions of Law No. 10436/2002 for the education of deaf people.

A longitudinal analysis such as that conducted is uncommon, even more so involving a 20 year period, in which a historical series is generated, thus providing "general overview, of approximate type, about a given fact" (GIL, 2008, p. 27), a characteristic of exploratory research. Finally, it was also used the descriptive research, seeking the "description of the characteristics of a given population or phenomenon or the establishment of relations between variables (GIL, 2008, p. 28). The information was collected from the websites of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), through the IBGE System of Automatic Recovery (Sidra), the Basic Education Census, through the Statistics Synopsis, and the Higher Education Census, through the Statistics Synopsis.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

According to Rocha (2019, p. 46), "the data of the Basic Education and Higher Education Censuses were collected for the first time in 1995, however, disabled people start to integrate the counts from 1996, in Basic Education, and 1999, in Higher Education". The collection of data of disable students and, among these, the deaf people, already occurs for more than 20 years annually by the National Institute for Educational Research "Anísio Teixeira" ("Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira" - Inep), which indicates a maturity in the gathering of this information and what increases even more the reliability of its use, including the Statistical Synopses, published with the microdata annually and that, sometimes, is the target of criticism by researchers in the area, but that is endowed with public faith and must be used by those who know the mutations of such and even of the microdata (ROCHA, 2019).

The data that made up Table 1 are those released in the Statistical Synopses of the Basic Education and Higher Education Censuses. They reflect a scenario close to the reality of the population of deaf and hearing-impaired students in Brazil and provide subsidies to draw a profile of these in the educational scenario and thereby help us in understanding the developments (or involutions) and changes in a period of 20 years after the publication of Law No. 10436/2002. We emphasize that these numbers do not mean improvement in the education quality or even greater permanence of this population, but represent statistically portrays what we experience.

Noteworthy is that until the year 2006, deaf students and hearing impaired students were grouped in the same category of disability in the Census of Higher Education, without distinction between them, which changed from the year 2007, when deaf students and hearing impaired students began to be understood differently. In the Basic Education Census, this distinction was detected in 2003 and, as of 2004, the counting was already different for the two groups. Table 1 presents data related to deaf and hearing impaired students in Basic Education.

Table 1 Historical series of the data of deaf and hearing-impaired students in Basic and Higher Education

| YEAR | HIGHER EDUCATION | BASIC EDUCATION | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DEAFNESS | HEARING IMPAIRMENT | DEAFNESS Clas. Com. | HEARING IMPAIRMENT Clas. Com. | DEAFNESS Clas. Excl. | HEARING IMPAIRMENT Clas. Excl. | |

| 2002 | No records | 344 | No records | 7.689 (1.69) | No records | 35.582 (1.58) |

| 2003 | No records | 665 | No records | 8.772 | No records | 36.242 |

| 2004 | No records | 975 | 5.383 | 8.411 | 17.179 | 19.509 |

| 2005 | No records | 1245 | 28.293 | 6.769 | 10.761 | 2.654 |

| 2006 | No records | 1.400 | 26.750 | 6.825 (1.55) | 17.165 | 4.197 (1.66) |

| 2007 | 442 | 1.004 | 16.407 | 18.418 | 16.120 | 13.205 |

| 2008 | 600 | 1.524 | 18.057 | 22.332 | 14.917 | 11.205 |

| 2009 | 1.889 | 4.653 | 18.160 | 24.317 | 12.441 | 8.118 |

| 2010 | 2.162 | 2.531 | 22249 | 30.251 | 11.123 | 7.200 |

| 2011 | 1.582 | 4.078 | 25.974 | 31.190 | 9.870 | 5.582 |

| 2012 | 1.650 | 6.008 | 27.540 | 32.221 | 8.910 | 5.236 |

| 2013 | 1.488 | 7.037 | 25.362 | 31.617 | 8.007 | 4.521 |

| 2014 | 1.629 | 5.321 | 24.411 | 31.041 | 7.023 | 4.142 |

| 2015 | 1.649 | 5.354 | 22.945 | 31.329 | 6.202 | 3.872 |

| 2016 | 1.738 | 5.051 | 21.987 | 32.121 | 5.540 | 3.521 |

| 2017 | 2.138 | 5.404 | 21.559 | 33.994 | 5.081 | 3.448 |

| 2018 | 2.235 | 5.978 | 20.893 | 36.066 | 4.997 | 3.241 |

| 2019 | 2.556 | 6.569 | 20.087 | 36.314 | 4.618 | 2.954 |

| 2020 | 2.758 | 7.290 | 18.994 | 36.588 | 4.145 | 2.854 |

| 2021 | No records | No records | 17.795 | 36.239 | 4.046 | 2.751 |

| 2022 | No records | No records | No records | No records | No records | No records |

Source: Elaborated by the author, based on data from Inep (INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA, 2023a; 2023b).

At the present study, we choose to count deaf and hearing impaired students as a same category for the following reasons: a) if we compare with the year 2002, there will be a bias, because in Basic Education and Higher Education, deaf and hearing impaired students were taken as a same category; b) possibility that who puts the data in the census may not have the same thorough understanding about each of the disabilities (understand such differences) and, although the data are self-declared, many students (or parents) end up not declaring correctly and, when the categories are close (such as deafness and hearing impairment), the probability to the error may be accentuated; and c) in the demographic census of 2010, the IBGE did not distinguish the category deafness and hearing impairment, but only differentiated the levels of hearing impairment, thus, unifying the data from the educational censuses, we can compare them to those collected by the IBGE and other sources of information.

We identified, by data from the Statistical Synopses, that from 2002 to 2021 (latest data available on the Inep website), there was an increase of deaf and hearing-impaired students in Brazilian Basic Education, in common classes and schools, of over 600%. In classes and schools with special requirements, there was an opposite movement, with a reduction of about 80% in the number of enrollments of this public. If we add the specialised and common schools and classes (as the same category), we have an increase in the mentioned period of 40.6%. However, what most caught our attention was the increase in enrolments in Higher Education, which, from 2002 to 2020, grew by more than 2,800%.

The increase in enrollment is really something considerable, especially in the Higher Education. However, when we compare the enrolment of deaf and hearing-impaired students to the overall enrolment, something unusual occurs: in Higher Education, these students represented, in 2002, 0.009% (344 out of 3,479,913 enrolments) and, in 2020, the percentage was 0.11% (10,048 out of 8,680,354 enrolments), a increase of over 1,100% (from 2002 to 2020). According to Lima (2018, p. 215), "the formulation of a language policy aimed at serving Deaf people in Higher Education is very recent, since it stems from Law No. 10436/2002 [...]". Thus, the impacts of this inclusion are still being felt in slow steps.

In the data presented above, it can be seen that the increase in Higher Education, when analysed the group of deaf and hearing impaired people, was 2,800%. When the comparison with the enrolments in general is analysed, this growth was lower, around 1,100% (which goes from 0,009% of the enrolments to 0,11%). It is worth noting that the increase in overall enrolments in Higher Education was around 150% (from 2002 to 2020). Rocha, Lacerda and Lizzi (2022), when addressing the inclusion of deaf students in Higher Education, state that "these students are users of the Brazilian sign language (Libras), implying a relationship of linguistic difference in the university context, in which the language of circulation of most (Portuguese) differs, as to modality and structure, from Libras”(ROCHA; LACERDA; LIZZI, 2022, p. 14).

In this sense, in the research conducted by Rocha and Santos (2017) with deaf students at the Universidade Federal de Santa Maria (UFSM), it was possible to identify that, sometimes, in the relationship between deaf student and hearing teacher, there is "[...] lack of interest of these in learning sign language, [...] lack of understanding of these regarding the use of visual resources and the provision of extra time and differentiated correction of semantic aspects of deaf students in written assessments" (ROCHA; SANTOS, 2017, p. 840). For Rocha, Lacerda and Lizzi (2022), what happens with hearing impaired students is that "[...] generally perform orofacial reading and establish communication via Portuguese language, even if precariously [...], which may generate in the institution a certain 'comfort' by not having to make major adjustments to receive them" (ROCHA; LACERDA; LIZZI, 2022, p. 10), this "comfort", so named by the authors, may cause a greater variation of data for students with hearing impairment than for deaf students, for example: in the year of 2009, in higher education, there were 4,653 students, in 2010, there were 2,531 and in 2011, 4,078, which makes evident variations and even "disobligations" in having to declare students who demand few or no adjustments in their inclusion.

In Basic Education, in 2002, deaf and hearing impaired students in specialized schools and common schools were 43,271 of the 54,716,609 enrolments, which represented 0.07% of these. In 2021, the total enrolment was 46,668,401 and deaf and hearing impaired students were 60,831, which represented 0.13% of the enrolment, that is, from 2002 to 2021, there was an increase of 85% of enrolments when compared to students in general. However, when we analyse the growth or decrease of basic education in general, we find that in 2002, we had 54,716,609 enrolments and in 2021, 46,668,401, that is, there was a decrease of about 15% of the enrolments. In general, the enrolments have decreased in recent years, but the deaf and hearing impaired people have been in a steadily increasing curve, except in the analysis of specialised schools and classes, because from there it follows a national and international trend.

In Basic Education, we have two important distinctions in the calculation of enrolment, as they are divided into specialized schools and regular schools, which generates, to some extent, a polarity in these two modalities of education. However, in 2021, through Law No. 14291/2021, bilingual education for the deaf also becomes a modality of school education, which may bring tensions to an already polarized field. In this recent legislation, in Section 60-A, it states that:

Bilingual Education in this context, comes to be understood as a modality of school education offered in Brazilian Sign Language (Libras), as a first language, and in written Portuguese, as a second language, in deaf bilingual schools, deaf bilingual classes, common schools or in centres of deaf bilingual education, for deaf students, deaf-blind, hearing impaired signers, deaf with high abilities or giftedness or with other associated disabilities, opting for the modality of deaf bilingual education. (BRAZIL, 2021, without pagination).

In 2020, it was published the Decree No. 10.502/2020 (BRASIL, 2020), which established, at the time, the National Policy on Special Education: Equitable, Inclusive and with Lifelong Learning ("Política Nacional de Educação Especial: Equitativa, Inclusiva e com Aprendizado ao longo da Vida" - PNEE-2020), which lasted a few days. However, it brought, quite clearly in its text, that "[...] deaf people seem to compose a separate group from the PAEE students and, apparently, the PNEE-2020 would be configured as two policies in one, with differentiated actions for two distinct groups" (ROCHA; MENDES; LACERDA, 2021, p. 14). In summary, this polarization expressed in the PNEE and already present for some time in academic discussions about specialized schools and common schools was what led, in 2012, the seven Brazilian deaf doctors (until then the only ones with a doctoral degree) to write an open letter to the Education Minister, contesting, at the time, the reason for the closure of bilingual schools:

It hurts us to see that these spaces of linguistic acquisition and mutual coexistence between sign language speaking pairs have been labelled "segregationist" spaces and schools. This is not true! Segregationist and segregating school is the one that imposes that deaf and hearing students are in the same space without having the same opportunities to access knowledge. The fact that deaf students study in Bilingual Schools, where they are considered and accepted as a linguistic minority, does not mean segregating. (CAMPELLO et al., 2012, p. 2).

All this dichotomy present in basic education certainly contributed to the strengthening of the deaf movements, and the fight for the expansion of bilingual spaces became a mantra of the deaf community, which impacted and impacts the growth in the number of enrollments and the right to use Libras as a first language and Portuguese as a second language in written modality as a way to reinforce, for example, what is advocated in Decree No. 5.626/2005 (BRASIL, 2005; STORTO, ROCHA, CRUZ, 2019). Among the numerous challenges present in the lives of deaf and hard of hearing people, it should still be considered that:

Another challenge, which does not depend only on legal aspects, is respect for difference. When we mentioned attitudinal barriers, one of the greatest difficulties to be overcome at world level is the comprehension that difference is what constitutes the human being. In this regard, the legal aspects may help to move forward, when they provide for coexistence with differences in the most diverse spheres of society (ROCHA; OLIVEIRA, 2022, p. 14).

In this regard, living with deaf and hearing impaired people, in society in general, in schools or universities, has triggered a new way of thinking about disability and Libras, with positive results from the inclusion perspective on the social slant. The regulatory/legislative frameworks have contributed to the recognition of the person with disabilities in society, in which changes occur gradually and are absorbed. Authors such as Lima (2018) contrast this position, from the perspective that "when one thinks of Deaf students, several questions put in doubt whether this experience is inclusive or if it is another experience that, masked, is associated with exclusion” (LIMA, 2018, p. 211).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

More than twenty years have passed since Law No. 10436/2002 (BRASIL, 2002) which brought important achievements for the Brazilian deaf community, because through specific legislation, recognized the Libras as a communication and expression means of this community, bringing legal guarantees in the area of health and the inclusion of the discipline of Libras in the curriculum of some undergraduate courses. It is noteworthy that:

Law No. 10436/2002 [...] refers to the recognition and legitimacy of Libras in all public spaces, and also the requirement of its teaching as part of the curricula guidelines in training courses in Special Education, Speech Language Therapy and Teaching, at high school and college levels. (LACERDA; ALBRES; DRAGO, 2013, p. 67).

This research focuses on the analysis of these 20 years of the Libras Act, especially in the educational area. The advances and mismatches were identified : 1) the number of deaf and hearing impaired students in Brazil has increased exponentially in recent years, more than the overall enrolments; 2) Higher Education presents a increasing number of enrolments of deaf and hearing impaired students, above any other public, which may be associated with the creation of higher education courses in the Libras area, as provided for in Decree n. 5.626/2005; 3) there is still a gap to be overcome, because we have 344,206 people with hearing impairment in Brazil, who do not hear anything, 1,798,967 who have great difficulty to hear and 7,574,145 who have some difficulty to hear (INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA, 2016).

According to Technical Note 01/2018: "[...] it is identified as person with disability only the individuals who answered to have Great difficulty to Hear or Cannot hear at all in one or more questions" (INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA, 2018, p. 4, emphasis in original). People who have great difficulty and cannot hear at all represent 1.12% of the Brazilian population (2,143,173 out of 190,755,799). We point out that in Basic Education, deaf and hearing impaired students are represented by 0.13% and, in Higher Education, by 0.11%, compared to students in general. It is necessary to reflect that, in order to reach a correct percentage, these numbers would have to increase significantly.

The numbers show percentage growth when comparisons are made within the group of deaf and hearing-impaired students. However, when in comparison with the overall students, these numbers become minimum and it is not even respected the proportion of the percentages of the Brazilian population with hearing impairment. The IBGE data collected in 2010 (1.12% of the population) show that there is still much to be overcome and that the Law No. 10436/2002 was a very important initial moment for the deaf community. However, other public policies need to be created and/or incorporated, such as the 2016 law to reserve a quota of places for students with disabilities (BRASIL, 2016).

This research is not exhausted here, but it can and should serve as an incentive for other researchers to seek studies that identify historical series and present to society the whole contextual dimension of the advances in legislation and also in the education of the deaf community. Show and reflect on the deaf and hearing impaired people's scenario in Brazil and the changes in the education of this social group is of utmost importance.

REFERÊNCIAS

BRASIL. Decreto N.º 10.502, de 30 de setembro de 2020. Institui a Política Nacional de Educação Especial: Equitativa, Inclusiva e com Aprendizado ao Longo da Vida. Brasília, 2020. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2020/decreto/D10502.htm >. Acesso em:10/11/ 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto N.º 5.626, de 22 de dezembro de 2005. Regulamenta a Lei N.º 10.436, de 24 de abril de 2002, que dispõe sobre a Língua Brasileira de Sinais - Libras, e o art. 18 da Lei N.º 10.098, de 19 de dezembro de 2000. Brasília, 2005. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2005/decreto/d5626.htm >. Acesso em: 05/08/2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei N.º 10.436, de 24 de abril de 2002. Dispõe sobre a Língua Brasileira de Sinais - Libras e dá outras providências. Brasília, 2002. Disponível em:<Disponível em:http://www.planalto. gov.br/ccivil_03/ LEIS/2002/L10436.htm >. Acesso em: 07/08/2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei N.º 12.139, de 1º de setembro de 2010. Regulamenta a profissão de Tradutor e Intérprete da Língua Brasileira de Sinais - LIBRAS. Brasília, 2010. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei N.º 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014. Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação-PNE e dá outras providências. Brasília, 2014. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei N.º 13.146, de 6 de julho de 2015. Institui a Lei Brasileira de Inclusão da Pessoa com Deficiência (Estatuto da Pessoa com Deficiência). Brasília, 2015. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei N.º 13.409, de 28 de dezembro de 2016. Altera a Lei N.º 12.711, de 29 de agosto de 2012, Reserva de vagas para pessoas com deficiência nos cursos técnico de nível médio e superior das instituições federais de ensino. Brasília, 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei N.º 14.191, de 3 de agosto de 2021. Altera a Lei N.º 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996 (Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional), para dispor sobre a modalidade de educação bilíngue de surdos. Brasília, 2021. [ Links ]

BRITO, Fábio Bezerra de. O movimento social surdo e a campanha pela oficialização da língua brasileira de sinais. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 2013. [ Links ]

CAMPELLO, Ana Regina e Souza et al. Carta aberta ao Ministro da Educação: elaborada pelos sete primeiros doutores surdos brasileiros, que atuam nas áreas de educação e linguística. Blog Mariana Hora. 2012. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://marianahora.blogspot.com.br/2012/06/carta-aberta-dos-doutores-surdos.html >. Acesso em:13/07/2019. [ Links ]

GIL, Antônio Carlos. Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa. São Paulo, SP: Atlas, 2008. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA. Nota técnica 01/2018: Releitura dos dados de pessoas com deficiência no Censo Demográfico de 2010 à luz das recomendações do Grupo de Washington. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2018. Disponível em:<Disponível em:https://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Censos/Censo_Demografico_2010/metodologia/notas_tecnicas/nota_tecnica_2018_01_censo2010.pdf >. Acesso em: 13/04/2022. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA. Metodologia do Censo Demográfico 2010. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2016. Disponível em:<Disponível em:https://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Censos/Censo_Demografico_2010/metodologia/metodologia_censo_dem_2010.pdf >. Acesso em: 31/03/2022. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA. Sinopses Estatísticas da Educação Básica. Brasília: Inep, 2023a. Disponível em:<Disponível em:https://www.gov.br/inep/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/dados-abertos/sinopses-estatisticas/educacao-basica >. Acesso em: 3/01/2023. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA. Sinopses Estatísticas da Educação Superior. Brasília: Inep, 2023b. Disponível em:<Disponível em:https://www.gov.br/inep/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/dados-abertos/sinopses-estatisticas/educacao-superior-graduacao >. Acesso em:31/01/2023. [ Links ]

JUNQUEIRA, Rogério Diniz; LACERDA, Cristina Broglia Feitosa de. Avaliação de estudantes surdos e deficientes auditivos sob um novo paradigma: Enem em Libras. Revista Educação Especial, v. 32, p. 28-45, 2019. <https://doi.org/10.5902/1984686X28732> [ Links ]

LACERDA, Cristina Broglia F. L.; ALBRES, Neiva A.; DRAGO, Silvana L. S. Política para uma educação bilíngue e inclusiva a alunos surdos no município de São Paulo. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 39, n. 1, p. 65-80, 2013. https://doi.org/<10.1590/S1517-97022013000100005> [ Links ]

LIMA, Marisa Dias. Política educacional e política linguística na educação dos e para os surdos. Tese (Doutorado em Educação). Uberlândia: Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, 2018. [ Links ]

ROCHA, Luiz Renato Martins da. Panorama nacional dos estudantes público-alvo da educação especial na educação superior. Tese (Doutorado em Educação Especial). São Carlos: Universidade Federal de São Carlos, 2019. [ Links ]

ROCHA, Luiz Renato Martins da; LACERDA, Cristina. B. F.; LIZZI, Eliângela A. S. Perfil dos estudantes público-alvo da educação especial na educação superior brasileira antes da lei de reserva de vagas. Práxis Educacional, v. 18, p. 1-25, 2022. https://doi.org/<10.22481/praxisedu.v18i49.9175> [ Links ]

ROCHA, Luiz Renato Martins da et al. Análise das sustentações orais da ação direta de inconstitucionalidade da PNEE-2020. Práxis Educacional, Vitória da Conquista, v. 17, n. 46, p. 1-22, jul. 2021. https://doi.org/<10.22481/praxisedu.v17i46.8857> [ Links ]

ROCHA, Luiz Renato Martins da; MENDES, Enicéia. G.; LACERDA, Cristina. B. F. Políticas de Educação Especial em disputa: uma análise do Decreto N.º 10.502/2020. Práxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa, v. 16, p. 1-18, 2021. <https://doi.org/10.5212/PraxEduc.v.16.17585.050> [ Links ]

ROCHA, Luiz Renato Martins da; OLIVEIRA, Jaima Pinheiro de. Análise textual pormenorizada da Lei Brasileira de Inclusão: perspectivas e avanços em relação aos direitos das pessoas com deficiência. Práxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa, v. 17, p. 1-16, 2022. <https://doi.org/10.5212/PraxEduc.v.17.19961.048> [ Links ]

ROCHA, Luiz Renato Martins da; SANTOS, Lara Ferreira dos. O que dizem os estudantes surdos da Universidade Federal de Santa Maria sobre a sua permanência no ensino superior. Práxis Educativa(impresso), v. 12, p. 826-847, 2017. [ Links ]

STORTO, Letícia Jovelina; ROCHA, Luiz Renato Martins da; CRUZ, Gilmar de Carvalho. Ensino bilíngue e inclusão de estudantes surdos no ensino regular: análise de uma carta aberta dos primeiros doutores surdos brasileiros em Educação e Linguística. THE ESPECIALIST, v. 40, p. 1-20, 2019. [ Links ]

Received: August 18, 2022; Accepted: March 17, 2023

texto en

texto en