Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.39 Belo Horizonte 2023 Epub 03-Mar-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469838402

Childhood Education Dossier

ARTICLE - CONTEXT EVALUATION: COLLECTIVE ANALYSIS OF EVALUATIVE INSTRUMENTS

1Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR), Curitiba, Paraná (PR), Brazil.

2 Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brazil.

The context evaluation is based on a participatory methodology that articulates two axes: i) “the negotiation of quality” and ii) “the promotion from the inside”, which combine self-assessment with external assessment, in a dialogic process of confrontation of viewpoints. The objective of this evaluation is to systematize hypotheses and projects for educational improvement based on the items evaluated. It is a reflective evaluation, in which the claims, concerns and questions of interest groups are the basis for determining the problematizations and necessary changes. It is a participatory and formative evaluation process organized in stages. The present work aims to analyze one of the stages of context evaluation, in its initial phase, in two context evaluation experiences: one carried out in Rio de Janeiro-RJ and the other in Pinhais-PR. This step consists in carrying out a critical analysis of the evaluation instrument carried out by the teachers together with the external evaluator. The entire process was recorded in audio, transcribed and analyzed, having as theoretical reference the studies of Bondioli and Savio (2015), Moro and Coutinho (2018), Corsino and Branco (2019), among others. It was observed that in the two contexts evaluated, throughout the evaluation process, the results showed the importance of analyzing the instruments for the teacher training process, due to the teachers' awareness of the aspects to be evaluated, as well as for the construction of common understandings in the teams, in a participatory, dialogic and democratic process.

Keywords: context assessment; early childhood education; teacher training; democratic participation

A avaliação de contexto se baseia numa metodologia participativa que articula dois eixos: i) “a negociação da qualidade” e ii) “a promoção a partir do interno”, que aliam autoavaliação com avaliação externa, num processo dialógico de confronto de pontos de vista. O objetivo desta avaliação é de sistematizar hipóteses e projetos de melhoria educativa a partir dos itens avaliados. Trata-se de uma avaliação reflexiva, na qual as reivindicações, preocupações e questões dos grupos de interesse são a base para determinar as problematizações e mudanças necessárias. É um processo avaliativo participativo e formativo organizado em etapas. O presente trabalho tem como objetivo analisar uma das etapas da avaliação de contexto, na sua fase inicial, em duas experiências avaliativas de contexto: uma realizada no Rio de Janeiro-RJ e outra em Pinhais-PR. Esta etapa consiste na realização da análise crítica do instrumento de avaliação realizada pelos professores em conjunto com o avaliador externo. Todo processo foi registrado em áudio, transcrito e analisado, tendo como referencial teórico os estudos de Bondioli e Savio (2015), Moro e Coutinho (2018), Corsino e Branco (2019), dentre outros. Observou-se que nos dois contextos avaliados, ao longo do processo avaliativo, os resultados evidenciaram a importância da análise dos instrumentos para o processo formativo, em virtude da tomada de consciência dos professores acerca dos aspectos a serem avaliados, bem como para a construção de entendimentos comuns nas equipes, num processo participativo, dialógico e democrático.

Palavras-chave: Avaliação de contexto; Educação Infantil; Formação de professores; Participação democrática

La evaluación en contexto se basa en una metodología participativa que articula dos ejes: i) “negociación de la calidad” y ii) “promoción desde adentro”, que combinan la autoevaluación con la evaluación externa, en un proceso dialógico de confrontación de puntos de vista. El objetivo de esta evaluación es sistematizar hipótesis y proyectos de mejora educativa a partir de los ítems evaluados. Es un diagnóstico reflexivo, en el que los reclamos, preocupaciones y cuestionamientos de los grupos de interés son la base para determinar las problematizaciones y cambios necesarios. Es un proceso de evaluación participativo y formativo organizado en etapas. Este artículo tiene como objetivo analizar una de las etapas del proceso, en su fase inicial, en dos experiencias de evaluación en contexto: una realizada en Río de Janeiro-RJ y otra en Pinhais-PR. Este paso consiste en realizar un análisis crítico del instrumento de evaluación realizado por los docentes junto con el evaluador externo. Todo el proceso fue grabado en audio, transcrito y analizado, teniendo como referencia teórica los estudios de Bondioli y Savio (2015), Moro y Coutinho (2018), Corsino y Branco (2019), entre otros. Se observó que en los dos contextos evaluados, a lo largo del proceso de evaluación, los resultados mostraron la importancia del análisis de los instrumentos para el proceso de formación, debido a la major conciencia de los docentes sobre los aspectos a evaluar, así como para la construcción de entendimientos comunes en los equipos, en un proceso participativo, dialógico y democrático.

Palabras clave: Evaluación en contexto; educación infantil; formación de profesores; participación democrática

INTRODUCTION

Olhar

Ferreira Goulart

o que eu vejo

me atravessa

como no ar

a ave

o que eu vejo passa

através de mim

quase fica

atrás de mim

o que eu vejo

- a montanha por exemplo

banhada se sol-

me ocupa

e sou apenas

essa rude pedra iluminada

ou quase

se não fora

saber que a vejo

In this poem, Goulart (2010, p.352) asks the question: what do I see? And he concludes with the answer that “knowing what you see” takes us out of the condition of being almost the object seen, that is, it humanizes us. It is not enough to look; it is necessary to be aware of what you are seeing. Research has shown (KRAMER, 2009) that educational practices in Early Childhood Education often happen without awareness of why we do what we do and that pedagogical intentionality has not always been the result of collective reflections. We understand that this awareness of the look - and here we take the look as a metaphor for human action - is fundamental for doing to be a praxis (FREIRE, 1982) and not an empty action. In this process, another poem completes the reflection: “your look, your look improves/improves mine” (ANTUNES, 1995). The look of the other improves mine, because as Bakhtin (2003) warns, only the other can see of me what I do not see (like seeing the back of my neck). Only the other, with his surplus of vision, can finish my actions and reflections. From this perspective, we understand that context assessment has a lot to contribute to the construction of a collective educational praxis that triggers a dialogical action. A dialogue with ourselves, in the sense of questioning our purposes, our conceptions about children, and our educational beliefs. Dialogue with the situations that we were willing to verify and our assumptions based on what the situations, carefully investigated, suggest. As a reflective, participatory and formative evaluative movement, which challenges participants to “know what they see”, context evaluation has the potential to change everyone's actions and lead to an improvement in the educational context of daycare centers and preschools.

This work aims to analyze one of the stages of context assessment, in two different experiences: one held in Rio de Janeiro-RJ and another in Pinhais-PR. This context assessment consists of a self- and hetero-assessment methodology that aims to improve the quality of educational practices. Bondioli and Savio, based on Guba & Lincoln (1989), define context assessment as a fourth-generation assessment, that is, an assessment that seeks not only to break with the positivist paradigm, of quantitative measurements, of disregarding the context, of elimination of alternative ways to think about the object of the evaluation but also to attend to the demands, concerns, and questions of the interest groups. It is a dialogic, responsive, formative assessment that has participated as a principle. In this article, we propose an analysis of the third stage of context assessment, in two different realities and with different instruments. This phase consists of discussing the instrument as the basis for the assessment process, referring to the collective and democratic debate of each descriptor of the instrument chosen by the group, and initiating the process of negotiation of educational quality. Thus, before proceeding immediately with the discussion about the relationship between evaluation and quality, it is worth making considerations from some interlocutors regarding the conceptualization of quality.

For Dourado, Oliveira, and Santos (2007), defining and conceptualizing quality education requires keeping up with historical changes and local particularities, considering social transformations and the new demands resulting from them. Cury (2014) when discussing the National Education Plan (PNE- Plano Nacional de Educação) states that educational quality is multidimensional, as it depends on initial and continuing teacher training, career plans, more dignified salaries, structural conditions, and adequate pedagogical resources and the guarantee of significant learning, which is understood to be available in school documentation - pedagogical project, planning, among others - and in educational-pedagogical practices. For this author, the PNE contemplates such dimensions, legitimizing their values.

With this, it is interesting to emphasize, in agreement with Peter Moss (2008, p. 17), that “the concept of quality is neither neutral nor free of values”. It is a subjective question, a specific way of seeing the world. Thus, the definition of quality is based on values and beliefs. It is a relative concept, articulated according to each context and socially constructed (DAHLBERG; MOSS; PENCE, 2019). For Moss (2008) defining quality is a process and this process is important per se.

According to Anna Bondioli and Donatella Savio (2013, p. 17), when thinking about educational quality, it is essential to consider “the very purpose of such institutions, being places of life, of culture, of “care”. The quality of an educational institution is what allows it to pursue this purpose in the best possible way (BONDIOLI; SAVIO, 2013, p.17, emphasis added by the authors). In this sense, they seem to agree with Moss, when they state:

Quality is not a fact, it is not an absolute value, and it is not adequacy to standards or norms established a priori and coming from above. Quality is a transaction, that is, a debate between individuals and groups who have an interest in the institution, who have responsibilities towards it, who are somehow involved with it, and who work to make explicit and consensually define values, objectives, priorities, ideas about what the institution is like and how it should or could be. (BONDIOLI; SAVIO, 2013, p.23).

Moss (2017, p.20-21) deals with the quality definition process as

[...] opportunities to share, discuss and understand values, ideas, knowledge, and experience;

- the process must be participatory and democratic, involving different groups that include children, parents, relatives, and professionals in the field;

- the needs, perspectives, and values of these groups may differ at times;

- defining quality should be seen as a dynamic and continuous process, involving regular review and never reaching a final, “objective” statement (emphasis added by the author).

Dahlberg, Moss, and Pence (2019, p. 119) propose the “meaning construction discourse”, which aims to deepen the understanding of the pedagogical work in the educational institution through a dialogical process and critical reflection with others. According to Savio (2018), “evaluating a given context means defining its quality profile, strengths and instabilities through comparison and negotiation” (p. 75). In this perspective, quality is understood as the result of confrontation and negotiation processes between the individuals that make up the educational context, mediated by an external participant, trainer/researcher. It is a participatory training methodology whose principles are “negotiation of quality” and “promotion based on from the inside”.

Bondioli and Savio (2015) understand the “negotiation of quality” as a process of explaining and adjusting conceptions and values among the members of the evaluated context. In this process, the individuals must share their intentions and aspirations to reach to minimum consensus among those who are part of the educational context (BONDIOLI, 2014). Through dialogue between them, the negotiation their values are woven and defined which are essential and shared by the group. Quality parameters and criteria are discussed in the collegiate dialogue to create a collective conscience about what will be evaluated. Freitas (2005), points out that “negotiated quality” it is not meant that each institution defines “autonomously and separately its quality indicators. This could lead to the perpetuation of economic inequalities in the form of school inequalities and vice versa (BOURDIEU; PASSERON, 1975; BOUR DIEU, 2001) or the creation of “schools for the poor”. (p.924). The author also states that:

It is important to emphasize that the definition of indicators, despite the local characteristics that will strongly explain the difficulties or facilities of implementation, is established in the set of needs and commitments of the public education system. It should also be noted that, for the public sector, quality is not optional, it is mandatory. In this sense, an intelligent and critical interface with the local community and with central public policies is a necessity (FREITAS, 2005, p. 924).

The “promotion from the inside” concerns the reflection of the educational practice in the quality indicators proposed in the evaluative instruments, individually and collectively by the participants of the process. Savio (2018) states that this reflective process takes place on two levels. The first of them involves the punctual observation of the educational actions around what is being evaluated in the educational context and the denaturalization of what is usual, reflecting on them in the sense of questioning “why do they do that action”. The intention is to question what is the objective of what is done and what are the foundations and references that support it. The second level concerns the comparison between “what you do” and “why you do it” with “what could be done” or “how you would like to do it”. It is in this reflective process, in the investigation of the differences between these two levels - what happens, why it happens, how it could be and how I can improve it - that “promotion from within” takes place. When reflecting on their educational practices, professionals become aware of them and their intentions and can think of possibilities and strategies, collective and individual, to improve the educational context.

The context evaluation methodology is characterized by the use of instruments with items, and indicators, to be evaluated and by the articulation between self-evaluation and external evaluation, in an evaluation process that does not end with verification but aims at a collective plan of actions for institutional improvement. The instrument chosen for the evaluation process aims to propose and encourage reflections on what is being evaluated in a given educational reality, such as the physical, relational or social environment; educational practices, educational strategies, and interventions; the curriculum in action; the organization of work among professionals, etc. - to raise awareness about the choices made (BRASIL, 2015). For Bondioli (2004) a reliable instrument demonstrates which are the relevant aspects to be observed and proposes quality parameters based on explicit criteria, allowing a confrontation between the real and the ideal school. It imposes a decentering concerning the situated view, invites the production of data and information for the issuance of a judgment, and encourages debate. Each instrument delimits the objective of the evaluation as well as defines the evaluation criteria. Through the instrument, fundamental questions are raised for the reflection of the individuals of the educational context involved in the evaluation process, it works as a mediator of the reflective-formative process.

To carry out the evaluation process as a whole, according to the methodological approach in question, successive steps must be followed by the trainer/researcher in a reflective and transactional way. Generally, seven steps are performed:

1st - the initial step is the explanation of the interest in carrying out the self- and hetero-evaluative path of context assessment for a given educational reality. Based on the idea of “promotion from within”, the educational community raises which members are interested in participating to form working groups (WGs), with a maximum of 20 participants, so there may be one or more WGs, who will be involved throughout the evaluation process.

2nd - the working group negotiates and defines the objectives of the evaluation and what will be evaluated.

3rd - there is the choice of the instrument to be used in the evaluation process and its critical analysis mediated by the trainer/researcher external to the group, who can be a specialist or a more experienced professional.

4th - the context assessment is carried out based on the instrument chosen and analyzed by the group. From the instrument, observations are made in a common time of the educational practice by those involved in the evaluative paths, trainer/researcher, and teachers, to evaluate the educational practices. That is, the answers to the instrument are marked based on what was observed and scores are assigned.

5th - the responses and instrument scores assigned by the trainer/researcher/external evaluator and teachers/internal evaluators are compared to discuss discrepancies. From this process, the strengths and those that need to be improved emerge, which allows the researcher/trainer to identify what are the educational characteristics of that institution and capture what points to be discussed and negotiated with the group.

6th - points to be improved are discussed and decisions, strategies, and goals are negotiated by the group and mediated by the researcher/trainer to improve educational quality.

7th - finally, the context evaluation process is evaluated as a whole - the choice of instrument, the performance of each of the steps, the mediation of the trainer/researcher, the interactions of the teachers among themselves and with the trainer during the process, whether the objective was reached, etc.

At all stages of the context assessment, it is important that each participant freely share their point of view, that there is empathy and trust among the members, and that a collective commitment to the evaluated context is built.

In this article, we will analyze the third step of the context assessment methodology in two experiences with different evaluative objectives, instruments, and educational realities. One of them was carried out in an Early Childhood Education School of the municipal public network of Rio de Janeiro - RJ. It aimed to evaluate educational practices in the field of language in preschool through the Context Assessment Instrument of Educational Practices of Orality, Reading, and Writing - IAPEOLE (Instrumento de Avaliação de Contexto das Práticas Educativas de Oralidade, Leitura e Escrita), developed to carry out this evaluation process. The other investigation was carried out with the municipal public network of Pinhais - PR (MORO et al., 2022), to debate the theme of the play and the possibility of this network carrying out an evaluation process based on the Good News instrument. Boa Creche Lúdica (SAVIO, 2011). The text is organized into three parts. In the first part, we make a brief characterization of the two instruments developed for the context assessment methodology. Then, we analyze the third phase of the methodology in both experiences and discuss what crosses them. Finally, we conclude with reflections on the possibilities of the methodology in the process of institutional self- and hetero-evaluation regarding the awareness of educational practices by teachers and their potential for reflection so that prospects for improving the quality of educational practice are established.

BRIEF CHARACTERIZATION OF THE INSTRUMENTS: “CONTEXT EVALUATION OF THE EDUCATIONAL PRACTICES OF SPEAKING, READING, AND WRITING-IAPEOLE” AND “GOOD PLAYFUL CARE”

The Context Assessment Instrument for Orality, Reading, and Writing Educational Practices - IAPEOLE was developed by Branco, Corsino, Bondioli, and Savio (2020 1) to think about a dialogic educational practice for children aged 3 to 5 years and 11 months, consistent with the National Curriculum Guidelines for Early Childhood Education - DCNEI- Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação Infantil (BRASIL, 2009), which consider children as the center of the educational process and interactions and play as axes of pedagogical work. In addition to this document, the instrument used Bakhtin's studies (1995, 2003) as a theoretical basis, which considers language in its discursive dimension and constituent of the subject.

The instrument is based on ten principles that are explained in its introduction. Among them, we will highlight a few below. Children are considered active and creative individuals who form themselves in their relationships with each other. They not only receive the other's word but also interpret and transform it. The interactions they establish with each other and with their surroundings are understood as interlocutions, as they are linked to the production of meaning. They are answers that trigger new questions and new answers, in an uninterrupted interlocutory flow. Play, written in the singular because it refers to the symbolic game of make-believe, is linked to interactions, since it is taken as an important voice of children, as it is how they re-signify what they live and feel, participate in culture, produce culture in relationships with their peers, interact with each other, develop, in addition to other inherent processes. Orality, reading, and writing practices, to make sense to children, need to be developed in meaningful, real, and/or imaginary situations. Oral expression, which is accompanied by gestures and intonations, is seen as a possibility to talk about oneself, the other, and the world, narrate, argue, defend a point of view, etc. Reading is understood as a significant action in which subjects expand their symbolic universe, their references, and their knowledge of themselves, others, and the world. It is the place for fabulation, imagination, creation, encounter, and interaction with the other, as well as language use and reflection on it. Children's participation in writing practices is taken as a possibility of recording different situations, both by the children, with spontaneous writing and drawings, and by the teacher, but always as part of a discursive process. The performance of the adult who reads and writes allows children to get to know different genres, functions, and materialities.

The instrument started with some questions: how are orality, reading, and writing considered in educational practices with children aged 3 to 5 years and 11 months? How is the educational context organized to provoke and sustain situations and games in which children can express orally and graphically, register in different ways, read, listen, narrate and create stories, speak, and talk, among others? What materials are available and what times are allocated for these practices? What is the role of the adult in this process? What has been prioritized in the teachers' planning?

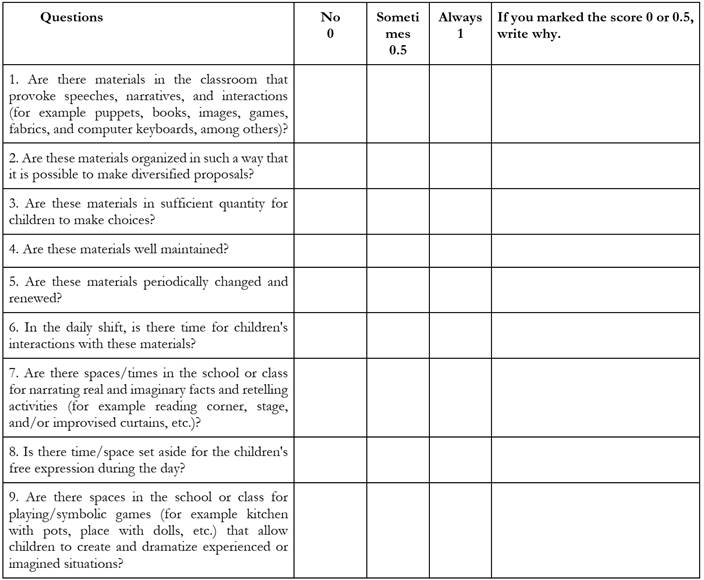

The instrument's construction process was based on the following documents: “Contributions to national policy: assessment in Early Childhood Education based on Context Assessment” (BRASIL, 2015); the “Reading and Writing Project in Early Childhood Education” (BRASIL, 2016), especially Notebook 5, and the Auto Valutazione Della Scuola dell'Infanzia - AVSI instrument (BONDIOLI; FERRARI, 2008). From them, 10 principles and 71 questions were obtained, grouped into three areas: i) materials and organization of the environment (space and time), ii) educational proposal and role of the adult, and iii) planning; the first two being subdivided into two blocks: orality and reading/writing. These three areas also correspond to guiding principles. Each question is scored on what was observed throughout the research period, on a scale of 0 to 1 as follows: yes (1 point) - corresponds to the questions that were observed as constantly present in the educational context; sometimes (0.5 point) to items seen occasionally or infrequently and no (0 point) to those that were not observed in the period. The answers “sometimes” and “no” are asked for justifications that will subsidize the confrontation of points of view between the self-evaluation and the external evaluation. It should be noted that the instrument is also composed of a general definition of each area and each block.

As an example, we bring below the indicators related to the orality block in area i) materials and organization of the environment (time and space)

A1. Orality

Even before birth, children are named and referenced, they are part of various enunciations and interlocutions. At birth, the mother feeds them, puts them on the lap, cares for them, and also gives the word that comes coated with tones, rhythms, touches, and affections. The verbal is accompanied by appreciative accents, non-verbal expressions, assumptions, feelings, and life. It is initially with his body that the child dialogically experiences the world, in a continuous relationship with the other, which also requires a constant negotiation of meanings and production of meaning. Interactive processes are interlocutory processes, although they are often non-verbal, as they share meanings and constitute language, speech, thought, and consciousness. When we refer to orality, verbal and non-verbal processes are in question, such as gestures, intonations, and the enunciative context. All understanding is a reply and there is no first or last word, as we enter an uninterrupted enunciative flow. Orality relates to this flow. It is worth highlighting that each sphere of human activity constitutes discursive practices that we can identify a set of genres. Each genre has a compositional structure, relatively stable, which is appropriated and used by the interlocutors. We also learn to speak in gender. In this item, the context assessment focuses on how much the available spaces and materials, as well as the time for their exploration, can provoke and sustain the children's enunciative processes.

The Instrument of Boa Creche Lúdica (SAVIO, 2011) recognizes playing as crucial for the child’s growth and well-being and “provides the active participation of the child and indicates playing as the “authentic voice of childhood, the main instrument to be able to carry it out” (SAVIO, 2013, p.257). Based on studies of the sociology of childhood, especially Corsaro (2011) and Mayall (2007), and psychoanalysis, especially Winnicott (1975), it starts from the assumption that playing is the voice of the child, its main form of expression. Observing the game is a privileged way to hear and listen to this voice to accept the children's point of view. It is also an important means of promoting children's participation in educational contexts designed for them. Savio (2013, 2011), in addition to the contributions of such authors, dialogues with J.Piaget, l. S. Vygotsky, J. S. Bruner, C. Garvey, S. Isaacs, S. Freud; M. Klein, A. Bondioli, T. Musatti, among others2. The author points out that observation as a tool to enhance the child's participation does not exempt adults, especially teachers, from maintaining and reverberating complex issues, such as, for example: listening to the child's voice without distorting it, so as not to be based on the adult-centered references for the interpretation; when and how to report to children to give them space without giving up their educational role as adults.

The main question of the instrument is: what educational conditions are the best for children's play? It was collectively prepared in an investigative-training process led by Donatella Savio, which involved 90 professionals from municipal and affiliated daycare centers in Modena, Italy. The instrument is based on a conceptual map that brings the meanings and educational reference values and six indicators (which sub-divided make up a total of ten items) with quality aspects to be evaluated to qualify a good daycare center, in its ludic dimension. They are: educational projects and play; spaces for play; play materials; times for play; formation of groups for play; and adults and play. The indicators related to space and materials are divided into three others, considering the reference room, and internal and external common areas.

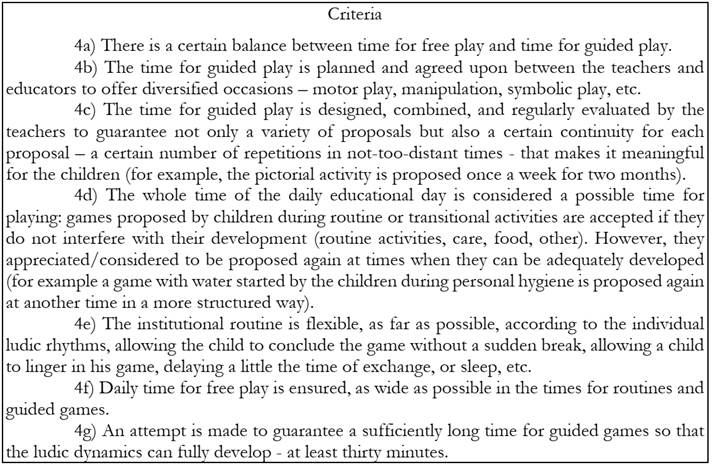

Thus, each of the ten indicators brings the description of circumstances that characterize a “good ludic daycare center” and are evaluated based on established criteria to guide the attentive and sensitive look of the professionals, from a lack of quality to a quality of excellence in the daily offer of possibilities for children's games. There are seven criteria for each indicator. Below, in Chart 1, one of the indicators that make up the instrument can be seen as an example.

Source: Translated and organized by Catarina Moro, based on Savio (2011).

Chart 1 Indicator 4: Playtime

The score follows a scale from “0” to “1”, as it best meets the requirements of each criterion: “0” if it does not meet that requirement at all, “0.5” if it corresponds to the partial fulfillment of that requirement, and, “1” if it corresponds to the full fulfillment of the criterion. Each indicator may not receive any score - when all criteria from “a” to “g” are not scored; up to score 7 - when all criteria receive a score “1”. Thus, the score of the indicators may vary between “0” and “7”.

For Bondioli (2004) the validity of the evaluation process as a whole depends on the adherence of the participants of the work groups to the criteria and quality parameters proposed by the instrument. The debate on the indicators and assessment criteria contained in the instrument encourages reflection (the basis of a formative assessment course) on the very idea of quality, implicit in the effort to judge whether the instrument's proposals coincide with those of the institution. Good assessment instruments outline a model of the evaluative object; determine what information will be collected, and declared, for each essential element that engenders an environment as educational; they define the evaluation criteria and envisage an achievable ideal for each specific element. Following the context assessment paradigm of the Pavia researchers, an investigation in Brazil focused on the ad hoc construction of an instrument for playing, which enabled the group of professionals involved to increase their awareness of the individual and collective perspectives related to the theme. It also provided the deepening of related concepts and a very unique modality of continuing education in terms of playing (COUTINHO; MORO; VIEIRA, 2019).

DISCUSSION OF INSTRUMENTS

Views on language, orality, reading, and writing

The evaluation process carried out by IAPEOLE was developed in a School of Early Childhood Education in the municipal public network of Rio de Janeiro. The municipal education network in the city of Rio de Janeiro has 634,007 children and young people, distributed in 1,544 schools. There are 144,206 children enrolled in daycare and preschool classes. There are 536 school units exclusively for Early Childhood Education and another 73 units with pre-schools and early years of Elementary Education.

The research field school is located in the South Zone of the city. At the time of the study, it had about 140 children, mostly from the low class, from 3 years to 5 years and 11 months, distributed in seven full-time classes. The choice of the research field school was due to the request of one of the members of the management team to carry out the evaluation.

Seven of the 12 teachers at the school voluntarily participated in the Working Group and the discussion of the instrument. Also, the pedagogical coordinator and the assistant director, and a volunteer Scientific Initiation scholarship holder who acted as an external observer to record the process participated in the study. For the discussion of the instrument, 2 meetings were held lasting 2 hours each, which were only possible due to the collaboration of teachers who did not participate in the research when they volunteered to stay with the classes of the members of the workgroup during the discussions.

The WG member teachers received the instrument in advance and were asked to do a critical reading individually to come to the meetings with questions and suggestions. In the two instrument discussion meetings, the researcher/trainer sought to create a welcoming environment of horizontal participation (MIGNOSI, 2001; BONDIOLI, 2015). The intention was to give the discussion a conversational tone so that everyone felt comfortable participating. After reading each instrument item - principle or question - a space was opened for discussion of what had been read. To encourage debate, the researcher/trainer tried to ask questions to the group or to one of the participants, such as: what did you think? What is your opinion on this issue? Is it clear? Is there any point that caught your attention?

Throughout the meetings, we observed how much participation is not given beforehand, especially in hierarchical contexts as observed in municipal schools in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Thus, participation was being built in the democratic process that was sought to establish in the discussion of the instrument in which trust in the researcher/trainer and the group's perception that the voice of each member mattered were fundamental achievements to seal the commitment to the evaluation. The difference in participation between the first and second meetings was clear and the reflections raised demands for deepening the reflections. There were many moments when points of view diverged and differences were confronted. Next, we highlight three discursive events that bring moments from the discussions of the collective reading of the instrument. It is important to mention that, for ethical reasons, the names mentioned are fictitious.

Language: representation of thought, instrument, work area?

The researcher/trainer reads the first principle of the instrument: “Language is conceived under the discursive and constituent perspective of the subject, closely related to thought and consciousness, therefore, it cannot be considered just as a mere instrument or area of work”. Question: - What do you think about this principle?

I agree. I see how language differentiates children and people. [The difference is] in the way each one expresses themselves, in the way they use that language. It is dissociated from that [perspective] in which the subject is the one who speaks. - Carla speaks in a tone of criticism of what would be another perspective.

She is the representation of thought. If the child does not speak, the thought is almost closed. -Laura complements Carla's speech.

(…) And this part here where it says “it cannot be considered a mere instrument or area of work”, [what did you think]? - Ask the researcher/trainer to encourage the participation of other members of the group.

It constitutes the individual. So, it cannot just be an instrument. - Laura

It permeates all the other activities we do. - Carla

She's worked all the time. We don't plan to work [orality or writing], and we don't separate the activities [does not divide into activities] of oral and written language. You're working with the language all the time. - says Wanda.

It is part of the body itself, so to speak, like a foot or a hand, or a leg. It is an instrument of coexistence. It is not possible to say that it is just an object of study or something that we can work on. (…) - Laura says as soon as Vanda finishes.

(Field diary, August 9, 2018)

Carla shows that she understands that everyone expresses and appropriates language differently, according to their characteristics. For her, language goes beyond speech by saying that “(...) it is dissociated from that [perspective] in which the subject is the one who speaks”, and can be expressed in different ways. When the researcher/trainer questions it again, the group says that language “permeates all the other activities we do”. It complements the previous speech and brings the idea of language as a constituent of the subject, not seen as an instrument, or a work area. It seeks to dialogue with the perspective of language present in the instrument.

On the other hand, Laura states that language is “a representation of thought”. She believes that “if the child does not speak, the thought is almost closed”. This goes against the interactions he establishes with the children. For example, on the phonetic level, the child starts to speak a word, however, on the semantic level, the first word pronounced is a complete sentence that contains the meaning of a whole, that is, the thought does not coincide directly with speech (VIGOTSKI, 2001). In a second moment Laura states that language “constitutes the individual” and “it can not only be an instrument", she initially seeks to dialogue with Carla's perspective. These statements seem to indicate that she understands language as constituting the subject and beyond a mere object. However, later on, she says that: “language is part of the body; it is an instrument of coexistence” when trying to tune her speech with that of another colleague, Vanda. Finally, she says that it is not “just an object of study or something we can work on”. Laura's speeches reveal that, on the one hand, she seeks to tune her speech with the language conception present in the instrument, even though she is not clear about the concepts she refers to.

Vanda tries to relate the principle of the instrument with the educational practices present in the school. She shows that she considers that language is present in all educational activities, with oral language and written language addressed inseparably. In this sense, she says that “[she does not divide into activities] oral and written language” because she works on “language all the time”. On the one hand, it seems that the perspective of language is present in her speech dialogues with the first principle of the instrument, but on the other hand, she seems not to recognize the specificities of written language. A fact that is later problematized in another part of the instrument.

Bakhtin (1995) postulates that understanding someone else's word means orienting, “finding your proper place in the corresponding context” (p. 132). The teachers sought to find this suitable place, at times their lines dialogued with the instrument, and at others not. It is evident, in the speeches analyzed - in particular, by Laura and, sometimes, by Vanda - the attempt to dialogue with the conception of language present in the instrument, even without understanding it very well.

“For 50 minutes a day, the children were free to decide”

(...) One of the teachers reads all the questions from the orality subarea of the Materials and environment organization area (time and spaces. (...) Thus, when the reading is finished, one of the teachers returns to the question “there is time in the daily workday for the children's interaction with these materials [materials used for language activities (puppets, costumes, books, etc.)]?”.

- It's [about] this issue of routine. We have to include this moment to access the [linguistic and free expression] materials in our routine, that is, we have to dedicate time within the routine, follow a routine that has time to include activities with these artifacts - says Angela trying to understand.

- At the time when I was Head of Early Childhood Education (...) there was lunchtime, which was for the whole school, and patio time, when I left the room. But, (...) within the daily routine I had a moment that I put in the planning of diversified activities in which the children had the freedom to choose the space they wanted to use. So, some stayed in the house, others in the games. (...) For 50 minutes of the day, the children were free to decide [what they wanted to do]. We agreed that you can't do everything in 50 minutes. One day I could make a drawing, the next day in another corner, and the next in another (...). There was also a concern that the game's shelf would always be moved, changing the collection. Because they lose interest in the toy that is there. They always had that possibility. - says Laura, in an explanatory tone.

(Field diary, August 9, 2018)

Ângela, when listening to the question, understands that it concerns the organization of the routine, especially in the organization of a delimited time for carrying out activities with the linguistic materials. She seems not to understand that the question refers to the children's interaction with these materials so that they can express themselves freely, without adult guidance.

The same can be observed in Laura's speech, a member of the school's management team. She tries to explain how the children's interaction with the linguistic materials took place, during the routine she instituted with her class: she organized the room into corners with a diversified work proposal. However, she delimited the time to 50 minutes a day, evidencing an institutional organization of time and not necessarily related to the needs and rhythms of the children.

The instrument assumes that “the properly organized context is capable of sustaining the idea of a competent child” (FORTUNATI, 2009, p.84). This means allowing this competence to manifest when organizing an educational context that is centered on children, with their specificities and rhythms, and not on adults. The child as the center of the pedagogical proposal, as postulated by the National Curriculum Guidelines for Early Childhood Education (BRASIL, 2009), presupposes an organization of the context that gives autonomy to children. The instrument presents the materials and organization of the environment as a possibility to promote interactions and meaningful experiences.

Thus, both Laura and Ângela seem not to have understood the instrument's proposal in the materials and organization of the environment. They interpreted the question relating to the offer of proposals directed and controlled by the adult. This a fact that was discussed and resumed at the time of the comparison of scores and that was presented as one of the points to be improved in the school.

“Now I'm seeing how important it is.”

(...) During the discussion of the instrument, the researcher reads one of the questions from the reading subarea of the proposed educational area and role of the adult:

- “Do the teachers invite the children to “read” the texts (books, newspapers, comics, etc.) made available to them (for example: tell me/tell us what the story of this book is...)?” - Then she asks: - What did you think of this question?

The teachers look at each other in silence. Until Rosa says:

They ask to retell a story. Children ask this. - She says it as if it were something natural. Then, in this case [the instrument refers to] it is us. If we invite [children to read stories] - Juliana explains thoughtfully.

I do that sometimes - reflects Rosa

I do not do this. (...) I don't think I value that. Maybe it's not intentional. I never stopped to separate space for valuing the child to do this. Now, I'm seeing how important it is. - says Juliana as if she were reflecting

(...) I tell the story and the children say: teacher, I can now read the story my way. I answer: yes, you can. Sometimes one wants it and everyone wants it too. Everyone can't go, but one or two will do. The space for the book is there. - Clara (...)

(Field diary, August 17, 2018)

Teacher Rosa, at first, does not realize that the instrument is referring to the adult inviting the children to “read” the different types of text made available to them. Therefore, she says that it is a natural movement of the children, and it is evident in the intonation that this is not an intentional pedagogical action. recreate different narratives. When Clara says “the space of the book is there” she restricts her action to organizing the space of the book. Undoubtedly this is fundamental, but would it be enough?

The question made Juliana face the fact that she did not invite the children to “read” “intentionally” and realize that this invitation would be a way to place the child at the center of the educational process. Juliana, by sharing her reflection, leads Rosa and Clara to think about their practices.

Given this, it is possible to note the power of the instrument in terms of the possibility of fostering reflections on their practices and sharing among the group of teachers so that some learn about the practices of others, share knowledge and concepts, and collectively problematize.

Visions and understandings about games and playing

The path taken from the instrument of “Good Playful Day Care” (SAVIO, 2011), which came to be identified in the investigation as “Assessment of Playful Contexts in Early Childhood Education”, had as its purpose the reading, study, and analysis of its translation3, to consider the potential and adequacy of triggering a process of reflection and improvement of the quality of the offer of games to groups of children in the educational units of the municipal network of Early Childhood Education in Pinhais, metropolitan region of the capital of Pinhais, state of Paraná. (MORO et al., 2022).

This Network provides regular care for children up to 5 years and 11 months of age from 21 Municipal Centers for Early Childhood Education (CMEIs) and 22 Municipal Schools, and most of the final classes of Early Childhood Education (Kindergarten 5) are offered in Elementary Schools. However, also for these units, the guidance and follow-up of the pedagogical work are carried out by the Early Childhood Education Management (GEINF- Gerência da Educação Infantil).

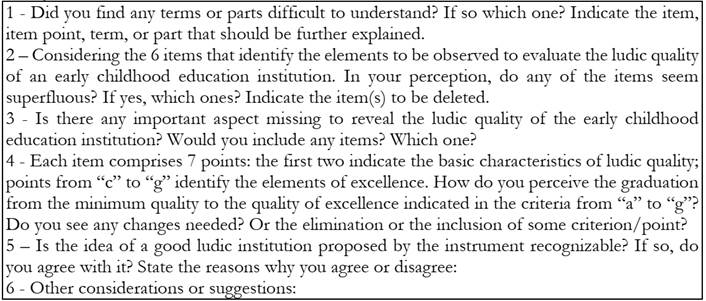

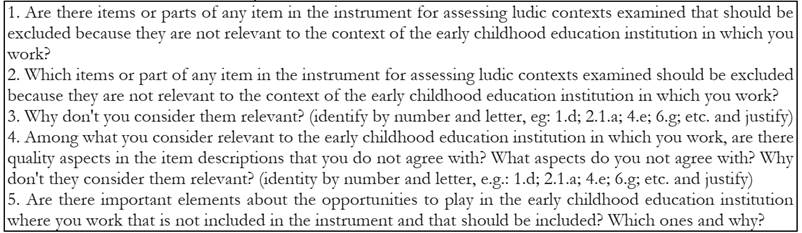

Regarding the route taken, the first meetings between the technical team (5 professionals) from GEINF/SEMED and the researcher-trainer took place in the second half of 20194 to discuss playing in early childhood education and its centrality in making educational of the Network. There were 5 meetings of approximately 2 hours each. For the evaluation of the assessment instrument, the script set out in Chart 2 is the basis for discussions within this smaller and beginner group in research training.

Then, during the process, a group of six educational units was chosen for a pilot research using the instrument translated and adapted to the Network, in which there was at least one unit: i) exclusively for children from 0 to 3 years old; ii) exclusively for children from 4 to 5 years old; iii) for children from 0 to 5 years old; iv) that assisted only Kindergarten V and with different dimensions of the internal/external spaces, v) reduced or vi) wide and; vii) in which the management team had already started debates about playing with the teachers and/or other professionals. Four meetings were held with the pedagogues and principals of the 6 units, all online, with a duration of 2 and a half to 3 hours. The 3 final meetings for appreciation and debate of the instrument, occupied 3 hours of work each and involved a large group, also gathered online via the Google Meet platform. It was made up of the researcher-trainer, the 5 GEINF professionals, 118 educators, 9 pedagogues, 8 professors, and 6 principals5. A total of 147 participants were involved in the process.

Source: Elaborated by Catarina Moro (2019).

Chart 2 Script for evaluating the Instrument “Assessment of Ludic Contexts in Early Childhood Education”.

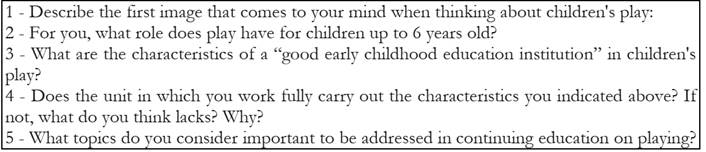

To introduce the discussion with the expanded group of educators and teachers, we organized a form on Google Docs to obtain information about the group and their understanding of play and its role in the educational daily life of the units. In addition to requesting some data about the participants and linkage with the stage and with the municipal network, some ideas were raised from the questions listed in Chart 3.

Source: Elaborated by Catarina Moro (2020).

Chart 3 Questions about play and its presence in Early Childhood Education”.

In this survey, professionals reported romanticized images concerning play: “happy children playing in a group, smiling, having fun”, “old and wheel games”, “lots of scattered toys”, “children running outdoors”, “wide spaces”, “situation of free imagination”. Other images associated with more education aspects, such as “children learning while playing”, “playing is a fundamental role in learning and integral development”, and “for the development of creativity, imagination, and abstraction, to build knowledge and develop skills”.

Regarding the relationship between the provision of quality play by the institution, there was reference: to children having “freedom to play and express themselves”, the appreciation of play in the Pedagogical Proposal, the possibility of playing every day of the week, the organization of environments and selection of toys by the teachers/educators, their participation in the games, the contact with structured and unstructured toys, the respect and involvement of children as protagonists and “architects” in playing, as they have a say in the planning of spaces and choice of toys. Also relevant for the group is the institution providing training on playing and other related topics.

After analyzing these preliminary data, and continuing the investigative-training path, the teams of the units had access to the translation of the instrument for an individual reading followed by the response to another form also proposed via Google Docs, in which there were 5 questions related to the analysis of the document and which would be a basis for mobilizing the discussion of the theme in online meetings. Below are the questions on the form that were answered by 141 professionals - educators (the majority), teachers, pedagogues, and directors. (Table 4).

Source: Elaborated by Catarina Moro (2020).

Chart 4 Questions for evaluating the Instrument “Assessment of Ludic Contexts in Early Childhood Education”.

The reading and critical appreciation of the instrument raised essential reflections in the group that raised questions about which one could think there were no doubts. However, the awareness of the role of playing in the educational daily life of institutions implies asking what constitutes play. How can or how should the teacher's intervention be so that the game does not become a didactic activity? How to define and differentiate “free play” from “guided play”? What is heuristic play? This stage of the evaluation process turns out to be crucial for understanding and discussing certain concepts and the notion of quality implicit in the different criteria of each indicator. Thus, how to think about how important and decisive they are: the planning and organization of times and spaces and the role of adults, teachers, and other professionals who share the daily experiences in Early Childhood Education institutions.

The analysis of the instrument also led to small adjustments, and textual changes, as long as they did not distort the original idea, to better articulate it to the educational reality of the Pinhais Network and so that it could be used in educational contexts for children from 0 to 6 incomplete years. The critical appreciation of the instrument allowed collegiate involvement, with the professionals' attentive and curious participation around the theme of the play, enhancing the formative dimension involved in the process. Issues related to the theme and which are directly or indirectly guided by the instrument were highlighted as aspects to be better understood and offered to children, such as: playing in and with nature and with natural resources and materials; the importance of the time allocated to playing in the pedagogical routine”; better use of spaces outside the unit, such as parks; the value of creating opportunities for socializing and playing among children of different ages; the use of varied materialities; implement and/or expand the offers of heuristic play; approach play, periodically and systematically, in continuing training, in service.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Assessment and reflection are intrinsically linked and converging processes. Evaluating the factors that guarantee and “make” the quality of a context, as a reflective practice, is a process of raising awareness about basic pedagogical options and concrete educational problems. It is an authentic formative process (BONDIOLI, 2004). Authentic because it is the result of a displacement, of a decentralization movement that allows looking at established pedagogical practices from another place, opening up the possibility of deviating from what is often empty. Reflecting with others on “what we do” and seeking to collectively understand “why we do what we do” is an authentic formative process because it originates from the field and goes back to it.

Bondioli and Savio (2015), based on Guba and Lincoln (1989), define context assessment as a “fourth generation” assessment, that is, an assessment that seeks to break with the hegemony of the positivist paradigm, quantitative measurements, disregard the context, elimination of alternative ways to think about the object of the evaluation, non-ethical responsibility of the evaluator for what emerges from the evaluation or for the use of its results, among others. Context assessment seeks a dialogical, participatory, responsive paradigm, in which the claims, concerns, and questions of the interest group are the basis for determining the information necessary for the assessment and whose result supports the development of projects and proposals for improving the quality of the evaluated context. As quality is a polysemic and contextual concept, which implies conceptions and values, the use of an instrument in the context assessment is presented as a quality parameter of the aspect to be evaluated. A parameter that is put to the test by the group, which critically analyzes each descriptor, being able to reflect, question, agree, disagree, and negotiate its point of view in the collective. The instrument, by putting the usual in check, either to affirm a perspective or to oppose it, causes displacements; and it is precisely this movement that, when made explicit in the collective, enhances the search for consensus and points to changes.

Context assessment, in this “fourth generation” paradigm, breaks with the idea of assessment as finding or checking descriptors, elaborated from outside and often unknown by the members of the evaluated context, to establish a sustained commitment with the members of the process principles of participation, reflection, and perspective of change. An evaluation vision that is formative from the choice of the instrument, passing through the sharing of the participants' points of view, until the consensual definition of the strengths and critical points of the institution, in its structural and procedural aspects. This is an assessment of a social and political nature, in which the entire dialogical process that is inherent to it - with reflections, considerations, and opinions of the members - favors the understanding of the investigated context deeply and dynamically and allows continuous reformulations based on the demands of the group.

As observed throughout the article, the reflections based on the analysis of the instruments, which were constructed by the researcher-trainers, are an important stage in the evaluation process. The instruments, when tested, individually and collectively, with directed questions favored reflections that were not given a priori. We analyzed this stage of context assessment in two different realities, with different instruments and procedures to highlight the inflection point that characterizes this evaluative paradigm. It is not just about knowing in advance what will be evaluated, but reflecting on the evaluation, questioning the descriptors, confronting them with the reality to be evaluated, and becoming aware of the theoretical issues that support them. The process is formative in different dimensions, especially because of the possibility for the group to seek grounded understandings and consensus. Research has shown that the analysis of the instrument is a watershed in the evaluation process, as it is already part of the evaluation. As we have already pointed out, evaluation and reflection are intrinsically linked and convergent processes. Careful listening to the reflections with a horizontal and dialogical mediation by the researcher-evaluators proved to be fundamental in the process, which shows that the choice of this professional requires criteria that concern not only the theoretical knowledge of the area that will be evaluated and mastery of the instrument, as well as a democratic posture. Thus, it is necessary to invest in a training process for specialists in Early Childhood Education who can integrate a mediating posture of acceptance that simultaneously encourages reflection and active participation, both about the sharing of points of view and of experiences, of the subjects involved in the evaluation process. It is how the mediation of the process is carried out that defines the characteristics of the external evaluator as a facilitator and trainer since the participation of the members of the context evaluation is directly related to how the mediation is carried out.

Both the process of analysis of the instrument “Evaluation of the context of educational practices of orality, reading, and writing”, carried out with the 7 teachers of the municipal school in the city of Rio de Janeiro, and the process of analysis of the instrument “Boa Creche Lúdica”, which involved 147 professionals working in Early Childhood Education in the city of Pinhais-PR, showed the formative power of the methodology. The instruments are i) conceptions-of language, of play-, ii) the relationship between time and space and the materiality offered to children in Early Childhood Education institutions, ii) the role/function of the adult, and iv) the importance of proposal planning. These four dimensions, which cross both instruments, have been understood in the field of Early Childhood Education, as key points for thinking about the educational quality of daycare centers and preschools. We can state that the analyzes of the instruments' indicators outlined an overview of educational quality in orality, reading, writing, and playing. The teachers' awareness of these indicators, which took place in the participatory and democratic process, enabled the teams to build some common understandings, triggered a training process, and also demanded an understanding of the need for studies and deepening. Returning to the poem in the epigraph (GOULART (2010, p.352)) the explanation of the descriptors in the instruments favored the members' awareness of educational practices, placing them in the condition of those who “know what they see” and opening perspectives for change to improve the quality of Early Childhood Education.

REFERENCES

ANTUNES, Arnaldo. Seu olhar. Album Ninguém, 1995. Acesso em 15/02/2022 Acesso em 15/02/2022 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YOFyJ82zrX0 [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, Mikhail. Estética da Criação Verbal. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2003. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, Mikhail. Marxismo e filosofia da linguagem. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1995. [ Links ]

BONDIOLI, Anna. Indicadores operativos de análise da qualidade: razões e modos de avaliar. In: CIPOLLONE, Laura(org). Instrumentos e indicadores para avaliar a creche: um percurso de análise da qualidade. Curitiba: UFRJ, p. 47-72, 2014. [ Links ]

BONDIOLI, Anna. Riflettere sul contesto e le pratiche educative: un modello di evaluation formativa. In: Le Culture dell’infanzia: trasformazione, confronti, prospettive. Atti del XVConvegno Nazionale Servizi Educativi per L’Infanzia (Genova 2-4). Edizioni Junior, 2004, p. 159- 178. [ Links ]

BONDIOLI, Anna; FERRARI, Monica (a cura di). AVSI - Autovalutazione dela Scuola dell’Infanzia: uno strumento di formazione e il suo collaudo. S. Paolo: Edizioni Junior, 2008. [ Links ]

BONDIOLI, Anna e SAVIO, Donatella. Elaborar indicadores de qualidade educativa das instituições de Educação Infantil: uma pesquisa compartilhada entre Itália e Brasil. In: SOUZA, Gizele; MORO, Catarina; COUTINHO, Ângela Scalabrin. Formação da rede em Educação Infantil: avaliação de contexto. Curitiba: UFPR, 2015, p. 21-49. [ Links ]

BONDIOLI, Anna e SAVIO, Donatella (orgs). Participação e qualidade em Educação da Infância: percursos de compartilhamento reflexivo em contextos educativos. Trad. Luiz Ernani Fritoli. Curitiba: UFPR, 2013. [ Links ]

BRANCO, Jordanna; CORSINO, Patrícia; BONDIOLI, Anna; SAVIO, Donatella. Instrumento de avaliação de contexto de práticas educativas de oralidade, leitura e escrita-IAPEOLE. Mimeno, 2020. [ Links ]

BRANCO, Jordanna Castelo. Avaliação de contexto de práticas de oralidade, leitura e escrita na pré-escola: desafios e possibilidades. Tese. Faculdade de Educação, UFRJ, 2019. Acesso em 11 de agosto de 2022. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://ppge.educacao.ufrj.br/ppge-teses-2019.html [ Links ]

BRASIL. Projeto leitura e escrita na Educação Infantil. Brasília: Ministério da Educação. Secretaria da Educação Básica. Coordenação de Educação Infantil, 2016. Acesso em fevereiro de 2022. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://projetoleituraescrita.com.br/ [ Links ]

BRASIL. Contribuições para a política nacional: avaliação em Educação Infantil a partir da avaliação de contexto. Curitiba: Imprensa/UFPR; Brasília: Ministério da Educação. Secretaria da Educação Básica . Coordenação de Educação Infantil, 2015. [ Links ]

BRASIL. CNE/CBE. Resolução no 5, de 17 de dezembro, 2009. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação Infantil. [ Links ]

CORSARO, William A. Sociologia da Infância. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2011. [ Links ]

CORSINO, Patrícia; BRANCO, Jordanna C. Avaliação de contexto na educação infantil: uma escolha para pensar a melhoria das práticas educativas. Pesquisa e Debate Em Educação, 10(1), 2020, p.1012-1026. <https://doi.org/10.34019/2237-9444.2020.v10.32016> [ Links ]

COUTINHO, Ângela M.S.; MORO, Catarina; VIEIRA, Daniele Marques. A avaliação da qualidade da brincadeira na Educação Infantil. Cadernos de Pesquisa. V.49 (174), p. 52-74, out./dez. 2019. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://publicacoes.fcc.org.br/cp/article/view/6174/pdf Acesso em: 5 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

CURY, Carlos Roberto Jamil. A qualidade da educação brasileira como direito. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, vol.35, n.129, p.1053-1066, out./dez. 2014. [ Links ]

DAHLBERG, Gunilla; MOSS, Peter; PENCE, Alan. Qualidade na educação da primeira infância: perspectivas pós-modernas. Porto Alegre: Penso, 2019. [ Links ]

DOURADO, Luiz Fernandes; OLIVEIRA, João Ferreira; SANTOS; Catarina de Almeida. A qualidade da educação: conceitos e definições. Brasília: INEP, 2007. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://td.inep.gov.br/ojs3/index.php/td/article/view/3848 . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

FORTUNATI, Aldo. A educação infantil como um projeto da comunidade: crianças, educadores e pais nos novos serviços para a infância e a família. A experiência de San Miniato. Tradução Ernani Rosa., 2009. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Educação como prática de liberdade. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 13ª. Edição, 1982. [ Links ]

FREITAS, Luiz Carlos de. Qualidade negociada: avaliação e contraregulação na escola pública. Educ. Soc., Campinas, vol. 26, n. 92, p. 911-933, Especial- Out. 2005. [ Links ]

GOULART, Ferreira. Toda Poesia , 20a. Edição. Rio de Janeiro: JoséOlimpio, 2010, p.352. [ Links ]

GUBA, Egon; LINCON, Yvonna S. Fourth Generation Evaluation. Newbury Park: Sage, 1989. [ Links ]

KRAMER, Sonia (org). Retratos de um desafio: crianças e adultos nas Educação Infantil. São Paulo: Ática, 2009. [ Links ]

MAYALL, Berry. Sociologies de l’enfance. In: BROUGÈRE, Giles; VANDERBROECK, Michel (Eds) Repenser l’èducatiomdes jeunes enfants. Bruxelles: P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2007, p. 77-102. [ Links ]

MORO, Catarina; COUTINHO, Ângela Scalabrin. Avaliação de contexto como processo formativo. Cadernos de Pesquisa em Educação. PPGE.UFES, p. 90-112, 2018. [ Links ]

MORO, Catarina; SANTOS, Nadir Fernandes dos; RODRIGUES, Francieli; SANTOS, Andressa Montilla dos. A brincadeira na perspectiva da avaliação de contexto na Educação Infantil. Revista Humanidades e Inovação. V.8, n.68, p.56-69.2022 Disponível em: Disponível em: https://revista.unitins.br/index.php/humanidadeseinovacao/article/view/7028 Acesso em: 20 maio 2022 [ Links ]

MOSS, Peter. Para além do problema com qualidade. In: MACHADO, Maria Lucia de A. (org.). Encontros e desencontros em Educação Infantil. 3 ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2008, p. 17-25. [ Links ]

SAVIO, Donatella. Il gioco e l’identità educativa del nido d’infanzia: un percorso di valutazione formativa partecipata nei nidi di Modena, Bergamo. Azzano San Paolo (Bg): Edizioni Junior, 2011. [ Links ]

SAVIO, Donatella. A brincadeira e a participação da criança: um desafio educativo e seus pontos nodais. In: e(orgs). Participação e qualidade em Educação da Infância: percursos de compartilhamento reflexivo em contextos educativos. Curitiba: UFPR, p. 243-303, 2013. [ Links ]

SAVIO, Donatella. “Promover a partir de dentro”: uma abordagem reflexiva e participativa da avaliação de contextos educativos. Pro-Posições, Campinas, v. 29, n. 2, p.72-92, Ago. 2018. <https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-6248-2016-0163> [ Links ]

WINNICOTT, Donald. O Brincar e a realidade. Rio de Janeiro: Imago, 1975. [ Links ]

1The instrument had a first version in BRANCO (2019). In the second BRANCO version; CORSINO; BONDIOLI and SAVIO (2020) underwent some changes, for example, it now has 10 principles and not 8.

3The translation was carried out by Catarina Moro; the first version was from 2017 and the current version from 2019, exclusively for research purposes.

4From 2020, all meetings were held online due to the suspension of in-person activities due to the pandemic caused by the new Corona Virus.

11The translation of this article into English was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES/Brasil.

5In the Municipal Education Network of Pinhais, the educational and management team of the unit has the following professionals: - educators - professionals with a technical medium-level qualification (Teacher Training) or a higher education course in Pedagogy, hired via civil service exam with a weekly workload of 40 hours; - teachers - professionals with qualifications in Pedagogy or a specific full degree to work in Early Childhood Education and/or early years of Elementary Education, hired via civil service exam with a weekly workload of 20 hours; - pedagogues - professionals holding qualifications in Pedagogy hired via civil service exam with a weekly workload of 20 hours working in the role of coordination or pedagogical advice; - principals - professionals elected through public consultation, belonging to the staff, statutory regime, occupying the other positions described above.

Received: February 15, 2022; Accepted: August 22, 2022

texto en

texto en