Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.39 Belo Horizonte 2023 Epub 03-Mar-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469839321

Childhood Education Dossier

ARTICLE - PARTICIPATORY INSTITUTIONAL SELF-ASSESSMENT OF EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS AND THE CO-RESPONSIBILITY OF EDUCATORS

1Universidade de São Paulo- São Paulo/SP/Brasil.

This article refers to some data from exploratory research, which had as its theme the implementation of Participatory Institutional Self-Evaluation, as a public policy for the evaluation of early childhood education in the municipal education system of the city of São Paulo, between 2013 and 2016. The case study involved professionals from 1869 teaching units and sought to analyze the process from the participants' perspective (FESTA, 2019). On this occasion, it is intended to focus on the educators' testimonies obtained in the questionnaire and semi-structured interview, portraying how they, at the time, conceived the issue of co-responsibility in the qualification of the daily practices of their respective institutions, since the perspective of transformation is a fundamental part of institutional self-evaluation (SORDI, 2010; SORDI; SOUZA, 2012; FREITAS, 2016; MORO, 2017). The research evidenced the resistance of professionals, from different institutions and different administrative instances, to assume the position of personal responsibility for the qualification of the service to children and their families (CAMPOS; RIBEIRO, 2016, 2017). It also brought elements that indicated the educators' difficulty in performing a truly critical analysis of their pedagogical practices (OLIVEIRA-FORMOSINHO; KISHIMOTO 2002; FREIRE, 1996), delegating to other actors or attributing to external factors the possibility of implementing the proposed and/or necessary changes. In conclusion, the data produced indicated the need, based on self-assessment, to establish relevant common goals, whose execution is an individual responsibility, but also assumed collectively, and that are intentionally articulated to the Political-Pedagogical Project of each institution (FREITAS, 2005, 2016).

Keywords: Participatory institutional self-evaluation; evaluation; quality of early childhood education; pedagogical practice

Este artigo refere-se a alguns dos dados de uma pesquisa de caráter exploratório, que teve como tema a implementação de Autoavaliação Institucional Participativa (AIP), como política pública de avaliação da Educação Infantil da Rede Municipal de Ensino da cidade de São Paulo-SP, entre 2013 e 2016. O estudo de caso envolveu profissionais de 1869 unidades educacionais e buscou analisar o processo da AIP sob a ótica dos participantes (FESTA, 2019). Nesta oportunidade, pretende-se focalizar os depoimentos dos educadores a questionário e a entrevista semiestruturada, retratando como eles, à época, concebiam a questão da corresponsabilidade na qualificação das ações cotidianas de suas respectivas instituições, visto que a perspectiva de transformação se constitui parte fundante da AIP (SORDI, 2010; SORDI; SOUZA, 2012; FREITAS, 2016; MORO, 2017). A pesquisa demonstrou a resistência dos profissionais, de várias instituições e de diferentes instâncias administrativas, em assumir a posição de responsabilização pessoal pela qualificação do atendimento às crianças e às famílias (CAMPOS; RIBEIRO, 2016, 2017). Trouxe, ainda, elementos que indicaram a dificuldade dos educadores em realizar uma análise verdadeiramente crítica de suas práticas pedagógicas (OLIVEIRA-FORMOSINHO; KISHIMOTO, 2002; FREIRE, 1996), delegando a outros atores ou atribuindo a fatores externos a possibilidade de realizar as transformações concretas julgadas necessárias. Em conclusão, os dados produzidos indicaram a necessidade de, a partir da AIP, estabelecer metas comuns pertinentes, cuja execução seja de responsabilidade individual, mas também coletivamente assumidas e que estejam intencionalmente articuladas ao Projeto Político-Pedagógico de cada instituição (FREITAS, 2005, 2016).

Palavras chave: autoavaliação institucional participativa; avaliação; qualidade da educação infantil; prática pedagógica

Este artículo se refiere a algunos datos de una investigación de carácter exploratorio, que tuvo como tema la implementación de la Autoevaluación Institucional Participativa (AIP), como política pública de evaluación de la educación infantil en la Red Municipal de Educación de la ciudad de São Paulo, entre 2013 y 2016. En el estudio de casos participaron profesionales de 1869 unidades educativas y se buscó analizar el proceso de AIP desde la perspectiva de los participantes (FESTA, 2019). En esta oportunidad, se pretende centrar la atención en las declaraciones de los educadores al cuestionario y a la entrevista semiestructurada, retratando cómo ellos concibieron el tema de la corresponsabilidad en la cualificación de las acciones cotidianas de sus respectivas instituciones, ya que la perspectiva de transformación constituye una parte fundante del AIP (SORDI, 2010; SORDI; SOUZA,2012; FREITAS, 2016; MORO,2017). La investigación mostró la resistencia de los profesionales de diversas instituciones y de diferentes instancias administrativas, a asumir la posición de responsabilidad personal por la calificación del servicio a los niños y las familias (CAMPOS; RIBEIRO, 2016, 2017). También aportó elementos que indicaban la dificultad de los educadores para realizar un análisis verdaderamente crítico de sus prácticas pedagógicas (OLIVEIRA-FORMOSINHO; KISHIMOTO 2002; FREIRE, 1996), delegando en otros actores o atribuyendo a factores externos la posibilidad de realizar las transformaciones concretas que se consideran necesarias. En conclusión, los datos producidos indicaron la necesidad, a partir del AIP, de establecer metas comunes relevantes, cuya implementación sea responsabilidad de los individuos, pero también asumida colectivamente, y que se articulen intencionalmente al Proyecto Político-Pedagógico de cada institución (FREITAS, 2005,2016).

Palabras clave: Autoevaluación institucional participativa; evaluación; calidad de la educación infantil; práctica pedagógica

INTRODUCTION

Between 2013 and 2016, the Municipality of São Paulo-SP (PMSP), through the Municipal Department of Education (SME- Secretaria Municipal de Educação), developed a public policy aimed at analyzing and qualifying the contexts of educational events offered to children aged 0 to 5 years and 11 months. The action involved the implementation and improvement of the Participatory Institutional Self-Assessment of Early Childhood Education (AIP- Autoavaliação Institucional Participativa) in the Municipal Early Childhood Education Units (EUs).

In a municipal document guiding the actions of the EUs, Normative Guidance number 1 of 2013 (SÃO PAULO, 2014), the issue of the quality of Early Childhood Education appears linked to the evaluation of children and educational systems, indicating two fundamental issues: to be a democratic and participative process and, also, as a progressively conquered condition, through movements of reflection and transformation.

Given the importance of understanding how such a public policy resonated with the participants in the process, a case study was developed that sought to identify how the AIP was experienced by SME educators1, as well as the results that they attributed to this process. It was also aimed to identify whether it was possible to establish relationships between the self-assessment process and the effective transformation of pedagogical practices, developed until then (FESTA, 2019).

The research carried out was within the scope of a qualitative paradigm, performing a case study involving 1869 institutions of Early Childhood Education2. The data mentioned here were produced from the semi-structured interview carried out with the Educational Technical Assistants (ATEs), who was responsible for monitoring the pedagogical practices and conducting the training processes of the UEs of nine Regional Education Directorates (REDs) in the city.

The study used stratified proportional sampling, in the choice of individuals participating in the research. Two variables were chosen: the highest representativeness of initial participation of the units in the evaluation process, instituted by the SME and the representative number of early childhood education units of each RED, about the Municipal Education Network.

The interviews were carried out between 11/16/2016 and 12/20/2016 and had the voluntary participation of 15 ETAs. The interview script consisted of nine questions that sought information about: a) the actions of the interviewees during the implementation of the AIP in São Paulo; b) their point of view about the results presented by the educational units they monitored; c) if they identified concrete changes in the evaluation process and/or in the results of the AIP over time, and d) the difficulties they encountered in implementing a qualified AIP in the institutions monitored.

We also refer to some data from a questionnaire that was answered voluntarily between 11/21/2016 and 12/28/2016, by 208 educators (teachers, managers, and educational supervisors) from institutions linked to these same REDs. The questionnaire consisted of 47 questions, answered digitally/online. The topics addressed involved: a) the identification of respondents in functional and educational terms (without nominal identification); b) knowledge of the AIP (instruments used, methodology, and purposes of the evaluation process); c) the relationship between the practices proposed in the self-assessment document and everyday educational practices and d) the AIP results in the reflective processes, everyday actions, and training.

The analysis described in this article will bring elements about how the study subjects conceived, at the time, the issue of co-responsibility in the qualification of the daily actions of their respective institutions, since the perspective of transformation constitutes a founding part of the AIP (SORDI, 2010; SORDI; SOUZA, 2012; FREITAS, 2016; MORO, 2017).

AIP IN THE CITY OF SÃO PAULO- SP BRIEF HISTORY

Between 2013 and 2014, using the Quality Indicators in Early Childhood Education (BRASIL, 2009d), a federal instrument produced for institutional self-assessment of Early Childhood Education, the SME carried out the AIP in 441 units of its network3 (CAMPOS; RIBEIRO, 2016). According to the secretariat, the main objective was to start the debate on the network about the AIP, verify the difficulties of the evaluation process and also build a document similar to the existing one but produced at the municipal level, which considered the local specificities in quality monitoring of Early Childhood Education in São Paulo (SÃO PAULO, 2015).

After shared reviews of these two processes, which involved most of the professionals from the municipal network and several families assisted, a final version of the guiding document for the AIP in São Paulo was produced in 2016, also with the wide participation of educators in the network, which has since become in effect: Quality Indicators of Early Childhood Education in São Paulo4 (SÃO PAULO, 2016).

The municipal document specifies the relationship between the guiding instruments for implementing the AIP and the objectives expected with the process

The indicators, therefore, seek to translate the different aspects of quality to facilitate discussion and collective reflection; its evaluation should indicate to the participants the ways to be indicated in the plan of action to obtain the quality improvements identified from the self-evaluation process developed in the Educational Unit (SÃO PAULO, 2016, p.11).

The AIP process takes place annually, until today, with the aforementioned document as a guide.

AIP: quality, participation, and transformation

Quality is a polysemic term. The perspective of quality adopted in this study, which is also underlying the proposal of the São Paulo AIP, is conceptually related to the paradigm designated by Oliveira-Formosinho (2009) as contextual. In this conception, the quality of a given educational context is the result of participation, negotiation, and sharing of meanings, quality is achieved in the process and will never be integrated.

Thinking about the participatory issue of the AIP process is fundamental to understanding its real objectives. For Terrasêca (2016), in the concept of self-assessment, the meaning of the term self is not only linked to the assessment of oneself, but concerns the exercise carried out together with others, based on the logic of an intersubjective confrontation and adjusted to the principle of reflection (individual and, at the same time, collective) on the work developed aimed at qualifying the educational service.

From this angle of analysis, the search for quality and the performance of the AIP are intertwined, because it is to qualify the action carried out in the context that the evaluation takes place, also considering possible effects and/or reverberations in broader contexts.

However, carrying out evaluation processes with the mere intention of knowing without using this knowledge for the benefit of those involved in the action is, at the very least, a great loss of energy, and ethically reprehensible since qualified education is a citizen's right.

We agree when the SME (SÃO PAULO, 2016) points to the AIP as an instrument that educational units should use to analyze their actions to support more conscious and consistent decision-making, which moves toward the construction of appropriate educational practices for Early Childhood Education:

Institutional evaluation can be a powerful tool for reconstructing practices resulting from the confrontation and negotiation of positions, interests, and perspectives; and also, to strengthen internal relations, as well as other decision-making bodies in the Education Network (SÃO PAULO, 2013, apud SÃO PAULO 2016, p.8).

We believe that, for the much-desired “qualification” to occur, it is necessary, in addition to effective (real) knowledge of the context in which the educational actions take place, a critical analysis of the pedagogical practice developed based on various perspectives and an effective engagement for transforming the educational context (spaces, times, relationships) and the pedagogical culture (OLIVIERA-FORMOSINHO, 2007), which involves practices, dominant beliefs and values, and the theoretical framework adopted. The data collected in the study described here point to the difficulties of educators in carrying out actions in this sense, a fact that we will now report.

We start from the assumption that every institution has its institutional culture, which guides its actions through a set of beliefs, values, and principles, determining what it aims to develop and/or achieve in that context and the expected behavior of its members. In this set, its members build and make the culture of a given context tangible, whether it is conscious or not for its members.

Therefore, although each individual has different perceptions of the same environment or situation, constituting their meanings, there are common elements in their conceptions that are constructed in a certain collective context, shared by the group. This configuration ends up formatting certain “recurring” conceptions that characterize the culture of that educational institution (FESTA, 2019, p.147-148).

Through the shared analysis of the Quality Indicators proposed for Early Childhood Education, in correlation with the actions carried out in the institution's daily life, the AIP provides for a) a situated and faithful assessment of what happens in a given context; b) the projection of changes to be effective for the qualification of the service provided and c) the planning of how such changes should occur.

To this end, in its methodology, the AIP already includes evaluative moments for the construction of a plan of action that includes the desired changes and the planning of monitoring the implementation of the planned changes.

For Formosinho and Machado (2009), the school should be invited to take the lead in its transformation, since change is considered a learning process, which must take place in an organization that restructures itself to become a learning community - not just for the students, but for everyone involved. In this way, the restructuring of the school appears to be associated with the improvement of the school curriculum and also with the professional development of those who are there.

Melo (2014, p.100), emphasizes that, for the self-evaluation of schools to be a relevant instrument for improving institutions, it is necessary “[...] that the school organization holds, practically and symbolically, the power to know and improve”, starting from the internalization of work coordination procedures and the transformation of educational practice, moving away from an industrial-bureaucratic logic towards an autonomous-professional logic.

According to Oliveira-Formosinho and Kishimoto (2002), reflection and transformation must go together, and the school is an organization that must continually think about itself, its social mission, and its structure, confronting the development of its activity, in a process that is both evaluative and formative. That is, reflectively thinking about the present to project the future.

In the study carried out, regarding the possibility of the AIP process generating concrete transformations of the action in the units in which they worked, especially in the implementation of the elaborated plans of action, the informants who worked in the monitored EUs brought (initially) encouraging data: for 57% of the educators5, who answered the questionnaire, the AIP was able to affect daily activities and only 37% did not obtain these results.

In the data from the ATEs interviewed, who accompanied the formative processes and, to some extent, the evaluations carried out by different EUs, there are more references to the transformation potential that can emanate and/or derive from the AIP, than to the concreteness of actions actual transformations that have taken place.

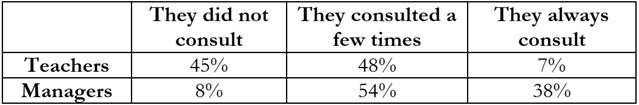

However, when asked whether they had re-read and/or revised the plan of action drawn up in the AIP, only 36% of teachers and 77% of managers who responded to the questionnaire stated practices in that direction. When asked if they consulted the plan of action (which is prepared in this systematic evaluation with a view to transformation), to review and/or redo their plans, the sample was configured as follows (Box 1):

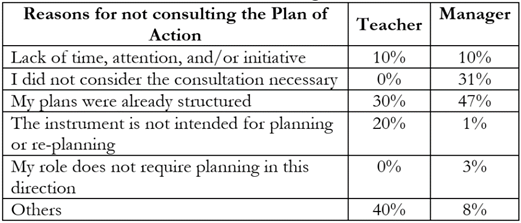

Of the professionals who reported not having consulted the prepared a plan of action, the thematic-categorical content analysis of the responses generated the table below about the reasons for doing so (Box 2):

It is obvious that for 30% of teachers and 47% of managers, the fact that their plans were already structured before the evaluation process led them not to consult the Plan of Action to re-plan their work, even showing the collective agreements from the AIP, which should be implemented to qualify the work developed so far. This is combined with the fact that 31% of unit managers did not consider consultation necessary.

For 20% of the teachers followed in the study, the document produced to guide the AIP process is not an instrument for planning and/or re-planning their actions.

According to our point of view, after carrying out the evaluation and identifying weak points in the practice developed in the EU, a careful reading of the descriptors used as an analysis parameter and reflection on their necessary developments in concrete actions, could indeed be a guiding element for the review of the plans of each educator and the institution as a whole.

As an example, we bring some descriptors that are part of dimension 3 - Multiplicity of experiences and languages in playful contexts for childhood:

INDICATOR 3.3 - BABIES AND CHILDREN EXPRESS THROUGH DIFFERENT LANGUAGES THAT ALLOW ENJOYABLE, STIMULATING, AND ENRICHING EXPERIENCES

3.3.1 Do teachers propose to babies and children games with sounds, rhythms, and melodies with the voice, signs, gestures, babbles, whispers and vibrations and offer musical instruments, sound objects, and access to musical cultures?

[...]3.3.4 Do teachers encourage babies and children to create paintings, drawings, constructions, and sculptures with different materials and supports (paper, floor, sand, plastic), suitable for the age group and specific needs, favoring free exploration and choice in their creative process?

[...]3.3.6 Do teachers tell stories or read books daily, of different genres and with different resources (Braille, Libras, audiobooks), for babies and children, promoting the literary experience?

[...]3.3.7 Do teachers encourage babies and children to handle books, magazines, and other texts, providing opportunities for contact with textual carriers and reading behavior?

[...]3.3.8 Do teachers encourage children, individually and in groups, to narrate their experiences, and their life stories, to tell and retell stories? (SÃO PAULO, 2016, p.37).

Sordi (2002, p.77) helps us to think about the great difficulties that arise when there is a need and/or desire to transform a given institutional culture, erected and perpetuated, in some way, in the educational institution. The author says:

We live in a positivist assessment culture in which there is no room for doubt and no time for reflection and participation. Everything is orchestrated to run smoothly, without hesitation. There is no interest in questioning the logic at stake (SORDI, 2002, p.77).

In this sense, it makes sense that some participants see the AIP as an episodic fact, without the need for major reverberations in their daily actions.

In the advice provided during the process of establishing the AIP in São Paulo, in the same period as the study reported here, Campos and Ribeiro (2017) systematically pointed out the difficulty of self-criticism present in the various educational institutions they monitored. Dealing with the analysis of data from managers present in training courses called “Regional Workshops”, the authors report:

Most of the responses, given by 17 groups (77%), pointed to the challenges inherent in carrying out a self-assessment: difficulty in self-assessment, in reviewing everyday practices, in denaturalizing the look, a tendency to always look “outside” and the lack of tradition in a culture of participatory self-assessment. (CAMPOS; RIBEIRO, 2017, p.50).

The research carried out brought results that strongly corroborate this statement and that pointed out the difficulty of institutions in promoting processes of critical analysis of pedagogical practice (CAPP), aimed at transforming and qualifying everyday tasks.

As an example, we will bring up the issue of “greening” as a result of the evaluations of the Eus, which we now present.

The AIP uses a color system (red, yellow, and green) to analyze the actions of the educational unit in the quality indicators and established descriptors, as goals to achieve a social quality service in Early Childhood Education.

According to the guiding document of the São Paulo AIP (SÃO PAULO, 2016, p.18), the color green should be assigned “[...] if the group assesses that these actions, attitudes or situations exist and are already consolidated in the institution, [.. .] indicating that the improvement process is already on the right path”; the color yellow is used “[...] if, in the institution, these attitudes, practices or situations occur from time to time, but are not consolidated” which indicates that they deserve care and attention; and the color red should be used “[...] if the group considers that these attitudes, situations or actions do not exist in the institution” and that the situation “[...] is serious and deserves immediate action”.

In institutions where the green color was predominant in the AIP results, in one or several dimensions analyzed, this result became known as “greening”, that is, when there was a predominance in the sense of validating the actions as already developed and understanding that the improvement actions were already in the right direction.

In the survey, several ETAs interviewed pointed out this issue, which even generated the need to carry out training processes aimed at managers of the units they worked. One of the examples is the following:

It was a school that gave everything green. It was a total greening. There was nothing that turned yellow, for you to have an idea. And then when... in the issues that were discussed, like, religiosity, for example, the school was respected, saying yes and then [...] but at school, on the posters, you saw the exact opposite of that. The school project was said to be about values. But Christian values. Christian values. So[...] how is that? (E.2.J) (FESTA, 2019, p. 168).

The interview results attributed the large existence of greening to different reasons: a) fear of negative evaluation by partners, families, or the SME; b) the difficulty of critically analyzing their educational practice; c) lack of experience in shared self-assessment processes; d) disbelief in the need and/or possibility of change.

The research asked the participants to identify, from the nine dimensions evaluated in the AIP, those which, in their educational unit, obtained the highest percentages of green concepts (Box 3).

The issues most related to educators' daily lives and their pedagogical practice (dimensions 2,3,4,66) were considered the ones with the highest percentage of indicators with green concepts (64% of managers and 86% of teachers). These same dimensions (2,3,4,6) were considered the most in need of transformation, by only 27% of managers and 19% of teachers.

According to 67% of the managers and 63% of the teachers, the plan of action of their educational units did not foresee any type of intervention for the indicators to which the green color was attributed, which leads to the understanding that the pedagogical practices that are directly linked to daily activities with children are no longer, in many units, the target of the idealization of qualification projects.

We believe that the fact that interventions directly linked to pedagogical practice are not included in the plans of action can become a disservice to the set of actions of the institution if this results from decisions arising from the lack of clarity of the real situation of the educational context or the lack of awareness of the necessary co-responsibility of those involved in the production of everyday realities (co-authorship).

Several study participants mentioned the educators' difficulties in carrying out a critical analysis of the pedagogical practice, which would fundamentally explain the greening of the dimensions more linked to their direct action with children in the daily life of the EUs. In most interviews, ETAs pointed to greening as a result of this difficulty:

And then we talk about it, how difficult it is for you to prevent the greening from happening in some themes. For example, the issue of gender. The gender issue [...] at my school was green. Green, supergreen. The children have shelves of toys for boys and girls, and they make lines for boys and girls, but “we don't have any problems” (E.1.R) (FESTA, 2019, p.169).

You have some dimensions there that are extremely linked to the teacher's work, the daily practice in the classroom, and then you usually see this dimension, these greens, because the people who are there in the room, at the forefront of the application [...] normally, in plenary sessions, they are either professors or administrators. And these people do have difficulty recognizing that their practices may be red. So, I leave it green [...] (E 8.C) (FESTA, 2019, p.174).

We also had situations, for example, in the dimension that speaks of the multiplicity of experiences, where everyone is green. Because I work with language. It's a language that's still quite fragmented... so, how much did we need to bring this dimension together with the integrative curriculum, and then we start to notice some yellowness. But at first, they didn't even dwell on that introductory text. “Oh, is it the languages? Ah, we do” (E.7.F) (FESTA, 2019, p.175).

Other speeches obtained in the interview show the difficulty of educators, from different instances and institutions, in analyzing in depth the conceptions and basic principles that supported each dimension of analysis proposed in the AIP. This obstacle ended up, according to several testimonies obtained, generating superficial evaluations that brought with them few actions in the sense of real criticism. As quoted, for example, by E.1.R in the interview, in which he says he has identified in several EUs that dimension 27 “[...] of listening, it is always green, because [...] children talk a lot, then they are heard. They talk a lot, they talk all the time.”

In the interview, E.1 emphasizes that, despite the evident misunderstanding of the concept of listening, as presented in the AIP guiding document, educators end up judging that their action is consistent with the desired quality proposal. The document says:

Thus, the listening of babies and children is not restricted to the auditory capacity of adults. It means, above all, the intentional, ethical, respectful, and non-judgmental willingness to understand the imaginative, creative, and poetic ways that babies and children have of seeing, feeling, and thinking about the world, their hypotheses, dreams, creations, cultures, desires, needs, as well as the challenges, concerns, and inequalities that mark their lives from early childhood.

Such an understanding makes it possible for planning, pedagogical documentation, and evaluation to be built with babies and children welcoming, encouraging, and challenging the exploration of the world, expanding their forms of creation, construction of knowledge, and coping with relations of inequality.

[...] It is, therefore, the guarantee of a child's right and a need for educators who transform their educational practice based on listening, guaranteeing children's participation and authorship in the construction of new and meaningful learnings. (SÃO PAULO, 2016. p.33-34 emphasis by us).

Kishimoto (2004) states that knowledge, because it has been built over an experience lived by professionals in their daily action, in a given contextual reality, is even difficult to transform, which will only be possible from reflection on the same practice, circumscribed by other perspectives and other conceptions. The author says that “[...] the teaching culture took a long time to build its solidity. The demolition will require time and persistence, and it is not the theory that will demolish such a structure, but the constant dialogue with practice illuminated by new concepts” (KISHIMOTO, 2004, p.337).

Unveiling the practice, which starts from reflection and is expressed through negotiations that use language as a resource, is according to Oliveira-Formosinho (2002) the only way to access the process of construction of meanings by the adult. For Formosinho and Machado (2009), the question of the constitution of the practice of educators does not appear disconnected from relational contexts, being always changing and suffering great influence in their learning paths.

[...] Significant learning is continuous, it influences the three dimensions of practice (mutual commitment, joint enterprise, and shared repertoire), it is open to the integration of new participants and it involves the organization the adaptability that guarantees its continuity as an emerging structure (FORMOSINHO; MACHADO, 2009, p.115).

In this sense, it is possible to consider the AIP as an aid in the reconstruction of teaching knowledge, since the process involves the collective analysis of actions, carried out based on the quality parameters accepted by a given social group, and which must be carried out in a participatory situation. Also, it includes proposing, carrying out, and monitoring effective transformation actions, to be carried out by those responsible (who are also defined by the collective).

This procedure needs to be carried out with seriousness and commitment by all instances and subjects involved to generate significant proposals for qualifying the practices developed, as well as the implementation of concrete actions in this direction. Melo (2014) highlights the importance of organizational learning for the realization of more concrete and lasting transformations:

Organizational learning corresponds to the phenomenon of knowledge acquisition by members of the organization associated with the impact that this knowledge has on the ways of thinking or doing within the organization Thus, organizational learning has a personal - cognitive - component associated with the acquisition of knowledge or skills by one or more people from the organization and an institutional component - action - associated with the impact of this acquisition of knowledge on the organization's work processes. There is only organizational learning when these two elements come together: acquisition of knowledge by the individual and action on the organization's processes (MELO, 2014, p.107).

Oliveira and Serrazina (2002) state that the idea of reflection and transformation is linked to how problems in professional practice are dealt with and require acceptance of the state of uncertainty. They claim that it is the recognition of a given problematic situation that will drive the individual and/or group towards discovering new paths of action, and building and implementing solutions. “This process involves equating and re-equating a problematic situation. [...] The reconstruction of some actions may result from new understandings of the situation” (OLIVEIRA; SERRAZINA, 2002, p. 33).

Thus, if the concrete actions of everyday practice are not analyzed, problematized, and constituted as difficulties to be overcome, how can we expect effective transformations?

For Cappelletti (2002, p.14-16), evaluating an institution means moving an entirely practical and theoretical structure, in which daily actions are based, which generates the appearance of “risk zones”, whether from the perspective of creating impressions negative about what is evaluated, either to point out the concrete need for transformations that need to be produced to qualify the actions.

Although we are clear that reflection on their work is a constituent part of the teaching profession, we know that such “risk zones” can indeed generate insecurities and resistance to evaluation.

In the study carried out, most of the participating ETAs mentioned that the fear of being evaluated was part of the process of many EUs, whose educators feared the concrete consequences for their careers in the case of negative evaluations. In the answers to the questionnaire, this question appeared clearly when educators reported that there was “[...] initial difficulty in understanding that the answers aim at educational evolution and are not sources of institutional shredding” (Q.G.48); there was the “[...] concern of the servers in revealing data that could harm them or for which they are punished” (Q.G.59) and even though “[...] the answers end up being manipulated, because the PMSP uses them as a punishment of teachers [...] and not as a goal to invest in education”. (Q.P.210).

In the interviews, this same bias was reported:

In some places, some entities 11, the principals met beforehand to see what they were sending, because there was a fear that this would generate a burden for the entity and that the entity would run the risk of losing the term of the agreement for not complying with it. those things. So, a filter was passed on what they would be able to send to us[...] (E.4.C). (FESTA, 2019, p.162).

The first impact of the evaluation was like this: “What do they want with this? Are you trying to rank us? Will it become a bonus? Will it become punishment?” So, as much as it was brought up in the speech that, that it wasn't going to happen, that wasn't the objective, that was the feeling that people had, of distrust, of even a certain step back to it (E.9.M). (FESTA, 2019, p.162).

Another issue concerned the fact that this professional had his work somehow negatively judged. Some ETAs interviewed illustrate this well, when referring to the speech of managers, and say:

It seems that at times indicators come up against my work: “Are you speaking badly?” And this saying “bad things about my work” is[...] it's a democratic process, of thinking that everyone is part of the school, that everyone has a voice: families, children, teachers, the management team, the cleaning team, the support team, everyone has a voice at school (E.2.C). (FESTA, 2019, p.163).

So, this capacity for self-criticism, this capacity for understanding what red means, however subjective it will be, but what does it mean? [...] So this need to prove that my work is good, not to sign their incompetence. So, this is (a little) anxiety (E.4.C). (FESTA, 2019, p.163).

Our current educational system uses evaluative processes, most of the time analyzing children's learning, with evaluators being teachers and/or higher levels of public administration. The use that is made of the data obtained follows a ranking perspective of the institutions and the actions developed, not having encouraging public policies that use the evaluation as a management resource to qualify the service, as proposed by the AIP.

Therefore, it is understandable that this distrust and this fear of assessing assertively are present. Our defense is that such insecurities can only be overcome, based on the adequate use of the results of the AIP by the educational unit and by other bodies of the public sphere, in addition to defending the urgent and continuous implementation of training actions that help those involved in understanding what is intended to be achieved with this type of evaluation and what is the role of each of those involved.

Co-responsibility - a delicate issue

The data obtained brought several elements in valuing the promotion of reflective processes on the curriculum carried out in the institution's daily life, as a result of the AIP.

It is interesting to note that for more than 15% of all educators who answered the questionnaire, the possibility of reflecting on their practice, which would be generated by the AIP, was considered one of the most positive aspects of the process. A similar appreciation came about in the sense that, as a result of the AIP carried out, the optimization of reflective processes within the unit took place.

The possibility of identifying the defects and qualities of the actions developed was also widely recognized by the study participants and evidenced in several speeches, such as:

I think the gain is in this, bringing an external perspective to the discussion, for me to go beyond what this school culture has already built[...] And I, as a manager, am also involved in this, and I don't see it either. I need that outside look, don't I? (E.7.M) (FESTA, 2019, p.246).

According to Alarcão (1996, p.175), reflection is a specific way of thinking because “[...] it implies an active, voluntary, persistent and rigorous scrutiny of what we believe or what is usually practiced, it highlights the motives that justify our actions or convictions and sheds light on the consequences to which they lead”. It is the act of being reflective that enables thought to be “meaningful”.

It is essential to point out that so-called “reflexive” processes, which are not authentic and have a secure basis in what is conceptualized as a social quality for education in a given historical-cultural context, can, as Oliviera and Serrazina (2002) say, be used only to corroborate actions already implemented.

Reflection may have as its main objective to provide the teachers with correct and authentic information about their actions, the reasons for their actions, and the consequences of that actions; but this reflection can also only justify the action, seeking to defend from criticism and justify it. Thus, the quality and nature of the reflection are more important than its simple occurrence (OLIVEIRA; SERRAZINA, 2002, p. 34).

To overcome the evaluative perspective conventionally used by educational policies, which is concerned with measuring the efficiency of educational institutions according to the market logic of capitalist society, AIP participants will be required not only to have a propositional attitude but also a proactive one in changing, a fact that needs to be intentionally and qualifiedly fostered (before, during and after the moment of self-assessment).

The study pointed out the difficulty of educators, from several institutions and different administrative instances, in assuming the position of personal responsibility for the care provided to children and families, as well as for their qualifications. That is the difficulty of critically analyzing their pedagogical practice to recognize the weaknesses of educational action and seek effective ways to overcome them.

Such difficulties were related, according to the research subjects, to the little daily reflective exercise on their action, to the need for educators to have more agency over planning and more effectiveness (concrete action) in the implementation of changes since usually it is required of them only compliance with educational programs already outlined and there is little experience of situations involving sharing/dialogue/negotiation.

The lack of habit of sharing and making decisions in the collective was pointed out as a difficulty in numerous lines throughout the interviews:

We don't have a history of social participation, and we will be called upon to evaluate public policy. So, it is logical, it is difficult, and there will be an emptying, but as we have to think about qualifying the document to improve this participation, this presence, it is not even participation (yet), it is the presence of the families, of being there (E.8.C). (FESTA, 2019, p.233).

We come from many years of fragmentation, power disputes, and virtual walls. Comprehensiveness [...] empathy, and listening to the other [...] are the document's greatest difficulty and also its greatest potential. It's collectivity. It's difficult (E.3.M) (FESTA, 2019, p.233).

Sordi (2009) emphasizes that each participant in the AIP process must both propose action priorities and commit to reflection on their responsibilities to achieve the goals established in the collective, that is, “[...] their protagonist action it is not restricted to suggesting changes to others, but realizing equally willing to change” (p.41). For this, it is necessary that people consider the transformation project relevant and decide to participate with responsibility and social commitment in it and that these subjects perceive themselves with some governance over the reality of the school, conceiving the change that comes from within as a fundamental element for build the face of the school.

In the words of Freitas (2016, p.134)

[...] such direction also requires that the internal community of the schools mature a perspective of internal negotiation that mobilizes its actors and moves them in the direction of the demands that must be made of themselves, as conductors of the formation of our youth. This is not achieved by inspecting our schools and subjecting them to constant auditing based on comparisons of averages or proportions of students at this or that level of learning. What is needed is a mobilization process based on participation, or, if we like, based on a participatory accountability style.

Some ETAs interviewed said they believed in the possibility of the AIP enabling reflective processes, with a view to transformation, but they highlighted the need for real involvement of the participants for this to occur:

The document, I think has the potential to help in training for this, and the other difficulty is, you need a team, the coordinator, or the teacher who recognizes the potential of the document's questions, of self-reflection. I would point out the potential of the document, of the process, and also the difficulty of the unit, of the teacher who is there, to do this self-reflection (E.8.C) (FESTA, 2019, p.229).

If I come from a task position, the Plan of Action of the indicators becomes one more. The PEA is another, and the PPP is another. One has no link with the other[...] And the Plan of Action is one more because we have the PPP disconnected from the unit's goal plan, which is disconnected from the Plan of Action, which is disconnected from the PEA. So, [...] it's an inheritance that we have to fragment things (E.3.M) (FESTA, 2019, p.229).

In response to the statement in the questionnaire, about the AIP being an unnecessary action, since the unit already has the habit of reflecting on its actions, we found that 74% of the educators thought that the AIP was still a necessary action, considering that the reflective exercise was not yet a completely established habit in the institution in which they worked.

As for taking responsibility for the transformation processes, Pinazza (2013) states that the teachers' feeling that the pedagogical practice does not belong to them, and that the changes originate from the outside, ends up generating an accentuated malaise (common among them), which lead them to develop mechanisms of “[...] isolation and exacerbated individualism, which keeps them away from sharing their experiences and anxieties and, ultimately, from the path of a common school project” (p.6).

The study presented here identified that the participants believed that the difficulties and/or problems that were effectively pointed out in the AIP were, in most cases, attributed and/or linked to factors that escaped the immediate governance of its participants, evidencing a tendency to de-responsibility and, sometimes, a “victimization” in the face of the situation experienced.

According to the information provided by the research collaborators, this fact was recurrent in the actions of the educators, but also the management of the units. Several mentions were made in this direction, for example:

I brought this greening up to discuss with the managers, and then it was interesting because then, either I throw it away or I also remove it from my responsibility. So, they started to say, “ah, teachers can't see themselves, teachers can't see their practices”. So, the multiplicity of languages part is the one that greened the most, and it was the one that greened the most. So, we see a little bit of what happens within the units in the manager and teacher. The teacher also gives it to the management and the management to the teacher (responsibility12) (E.9.M). (FESTA, 2019, p.175).

According to the participants, the AIP proved to be more effective in institutions that had greater experiences of participatory and democratic nature, and the institutionalized spaces that allowed the decentralization of power generated greater involvement of the individuals in the proposed self-assessment model, which evidenced postures that were not linked only to the results obtained, but also to reflective processes on the actions developed in everyday life.

Several ETAs mentioned the relationship they established between the “profile” of EUs managers and their actions in the development of the AIP, as well as in its consequences:

So, we realize that there are managers who get involved, who believe, who believe in the strength of the document, and who mobilize communities, and teachers for it to be effective, for it to be effective in its proposal. Some managers have nice words, but we see that they don't have the involvement and the Plan of Action, it shows us that. So, we often see in the Plan of Action that the discussions were not very shallow or that they still did not reach maturity in this assessment. And some managers don't believe it, some didn't come, they didn't attend the training, so we already notice some issues in this absence. Some fight, so they focus on the points that they consider fragile and they came up with this very proposition of clash, of opposition in the document. We noticed these profiles of managers (E.9.M). (FESTA, 2019, p.208).

The manager's profile will determine the quality in which this public policy was [...] and will be implemented in the unit. There are several managers, principals, coordinators, and assistants who have a more democratic, more progressive profile, and understand this public policy as an instrument for qualifying this practice and not as a means of finding culprits or anything like that. When this management trio is in tune, it is clear that the quality of this assessment, this discussion, is much more [...] purposeful (E.2.T) (FESTA, 2019, p.209).

According to Betini (2010), the leadership style, support, presence, and participation of the manager in the AIP are determining factors for its success. The author says:

The role of the school management proved to be of fundamental importance in conducting the collective participation process. In schools where the leadership of the board was present, acting actively, aiming at the transformation of the school and not just day-to-day tasks, the AIP implementation process was more successful. The political action of the school leader is also characterized by establishing objectives to be achieved, surpassing their merely bureaucratic attributions (BETINI, 2010, p.120).

When considering the great influence of the form of management in the AIP and its results, one of the conclusions of the study was the defense of the inclusion of views outside the EU in the evaluation process, adding other evaluators to this movement to promote the constitution of an even broader panorama of the unit's actions, to think about processes to support change, training, etc.

We do not defend that these evaluators are unaware of the local reality, but that they are not directly linked to everyday practices to facilitate the “strange look” in the face of the realities observed and analyzed in the institutional self-assessment, as well as to encourage the promotion of effective sharing processes and negotiation to transformation. Some interviews pointed out that the greater involvement and effective participation of school supervisors13 can help the unit's collective to carry out a more qualified AIP with better results in terms of the concrete transformation of actions.

A certain difficulty of educators in transposing the discourses of the need for transformation resulting from the AIP to effecting changes is not new. Campos and Ribeiro (2016, 2017) already pointed out the resistance of professionals, from various institutions and different administrative instances, in assuming the position of personal responsibility for the qualification of care for children and families based on the reflective processes that should derive from it.

The research carried out showed, with great clarity, that the fact of attributing the problems and/or difficulties, which were effectively pointed out in the self-assessment process, to those responsible for different instances of the evaluators (teacher to managers, managers to teachers or the municipal administration, etc.) was recurrent. Through the categorical analysis of the content of the responses to the interview and the questionnaire, it was possible to identify three major categories linked to the attribution of responsibility for the difficulties encountered in qualifying the service to external factors:

) the structural issues of the building or the scarcity of resources in the surrounding community;

) the lack of material, resources, and/or training - which should be “solved” by external agents;

) demands directed at the SME and other governmental bodies.

We observed that, in the path of external accountability for the difficulties listed by the AIP, structural issues predominated in the preparation of plans of action for the units in most of the REDs monitored.

The difficult issues: soon comes a question (of) renovation, adequacy of the building, and acquisition of material. It's all concrete stuff, which has nothing to do with relationships. So, you notice a lot[...] a lot of demand for the structural issue. (E.5.M).

In 2015, the greening was complete. Total. [...] Everything (which was not green14) was external demand. Everything that the unit had already made a request here (to higher bodies15)[...] then everything turned red (E.7.F) (FESTA, 2019, p.177).

As an example, for the outsourcing of responsibility to qualify everyday action, we can also mention what we found in Dimension five (Ethnic/Racial and Gender Relations), which was considered by 13% of managers and 7% of teachers as the dimension with the greatest need for transformation. However, the ETAs interviewed reported that this “need for transformation/qualification” of EU practices was attributed by AIP participants to the lack of training and/or material, and not to the action of educators and of the educational institution in children and their families:

Concerning ethnic-racial and gender issues, as a Plan of Action [...] in the Plan of Action, they asked for training on gender issues. So, it's always outside. So, I need to have the training to be able to bring it to my group, I need to have ethnic-racial training to be able to look (E.3.M) (FESTA, 2019, p.180).

So, like that, nothing is a problem that I solve in my classroom or what I try. I have no difficulty dealing with gender issues. The problem is that there are no dolls with a pipi. I have no difficulty dealing with ethnic issues. The problem is that we don't [...] have books that [...] and so on. So, there is always a lack of material, a lack of structure, and a lack of organization (E.1.R) (FESTA, 2019, p.180).

The formation also seemed to have to “emanate from an external source”, from an instance prepared to form the other, “donating knowledge”, not being considered the educator or the group of professionals of the institution as responsible for seeking the desired qualification, in the towards minimizing the formative edges that they identified. We are not defending here that it is not the role of the SME to have qualification actions for the professionals involved in the care of children and their families, but it is about thinking about co-responsibility, self-training, professional development, whose task is also the individual and the institution in which it works.

The data revealed that, for most of the ETAs interviewed, the units that were more aware of their practices and more attentive to their weaknesses, seem to have acted towards greater demand, both in the development of the self-assessment process and in the implementation of actions from it and effected, with a view to transformation.

On the other hand, units that developed practices that were visibly more dissonant than what was proposed as a quality for this educational stage, but that, due to difficulties linked to shared reflection, were unable to identify and/or assume these weaknesses and tended to judge their work as of greater excellence.

According to Day (2001, p. 83), “[...] being an adult learner means reflecting on the purposes and practices, as well as the values and social contexts in which these are expressed”. The author points out that openness to transformation and acceptance of other knowledge is essential for reflection, although they can be extremely challenging processes for teachers' cognitive and emotional skills, as well as for their personal and professional values on which educational action is structured.

The transformation processes to qualify the service, come from the analysis of the reality (contextualized) of each educational institution. They are fundamental in the perspective of participatory self-assessment; however, the process as a whole will only be valid on the effectiveness of the proposals.

[...] To have consequences, the evaluation process needs to generate decisions and actions. Whether it is a student assessment or an institutional assessment of the school, it will only overcome the bureaucratic nature if it generates consequences, otherwise, it can become just one more form to be filled out, one more meeting to be held, one more call for parents to be held, more a report to be produced that ends up having, many times, a “shelving” end.

[...] In fact, from the school to the Department of Education, if they do not have purposeful interaction with the result of the institutional evaluation and do not elaborate an intervention plan based on the results, the evaluation will become an activity that will be much more of an obligation than a means and instrument of work improvement (SOUZA, 2012, p.46-47).

It is evident the difficulty of the “need for transformation” and the “effectiveness of changes” to take place in the EU, without the establishment of public policies that support the institution in this direction.

It also seems essential to point out that without the concrete review process carried out “on the school floor”, by those who daily build an educational practice, against the background of the institutional culture established there, public policies can present as just another “dead norm”. That is, fated to be resolved in bureaucratic terms, without effective and/or lasting consequences for the groups involved, especially children and their families, who should be the first instance of beneficiaries of this evaluation process to qualifying public education.

In this sense, we agree with Melo (2014), for whom autonomy, also present and even founding in the AIP proposal, is not enough to guarantee the desired qualification:

The central question in the operationalization of this principle of autonomy that generates improvement is exactly to avoid the mistake of assuming that the autonomy of schools, in itself, causes improvement. Now, autonomy will only bring about improvement if, in the use of autonomy, the actors /in the school change their practices, making them more effective and/or more efficient. The autonomous school must develop itself (MELO, 2014, p.106).

We believe that overcoming these difficulties will come about through the real engagement of the group of AIP participants in the sense of building a co-authorship, not only in the evaluative path but also in establishing the co-responsibility of all those involved in the implementation of the transformations agreed upon by the group as fundamental for the qualification of educational contexts and the actions that take place there.

Participatory accountability is part of a form of counter-regulation (FREITAS et al., 2012) and involves coordinated efforts by multiple actors interested in defending an educational quality that confronts the logic of short-sighted policies restricted to specific interests of economic sectors. It implies exercising the school collective in processes of appropriating everyday problems and reflecting on the future, the main function of the evaluation processes (SORDI; FREITAS, 2013, p. 91).

Pinazza (2013) indicates paths for the much-desired transformation of institutional culture, based on collective effort. The author says:

For the school culture to be influenced, individual conditions must converge with the resources of the school community to have organizational development, that is, individual development and the development of professional learning communities are combined. Individual and collective efforts must have a common focus and integration, in such a way that energy is not lost in the plural, mismatched and fragmented innovations - this gives pragmatic coherence (PINAZZA, 2013, p.5).

It also emphasizes the role of leadership as a conductor of change initiatives and, sometimes, structuring the process with the development of reform strategies, leaving it with the important and difficult task of mobilizing all the actors involved with the educational practice towards the constitution of an institutional culture of change. This means understanding the need for reforms, when reality imposes the search for new equations for the challenges experienced within the unit, through investigative processes of everything that makes up everyday life. This cannot be done without strengthening interpersonal relationships and being willing to invest in the circulation of knowledge and experiences within the team (PINAZZA, 2014).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Monitoring the implementation of AIP in São Paulo in the city of São Paulo-SP, as well as its institution as a public policy for the entire municipal network, made it clear how many efforts were undertaken by the municipal administration given the exorbitant number of Early Childhood Education units in the city at the time.

It is important to point out that several findings of the study point to the validity and relevance of the action developed in the city of São Paulo-SP for the qualification of child care, as described in the doctoral thesis “Institutional Participatory Self-Assessment of Early Childhood Education in the City of São Paulo: the process from the perspective of the participants” (“Autoavaliação Institucional Participativa da Educação Infantil da Cidade de São Paulo: o processo sob a ótica dos participantes” ) (FESTA, 2019).

Thus, for example, there are effects of the AIP on the formative processes that take place within the EUs. Several data from the interview identified that the AIP was attributed a great training potential, either in terms of the possibility of unveiling the realities, which were not clearly explained before or in the promotion of proposals for continuity and/or deepening of the studies that were taking place in the institutions, whether it was in the possibility generated in the promotion of moments of shared reflection on the actions developed and/or desired:

Look, I think there are many potencies. In addition to what he even proposes, which is the question of evaluating the action, of having those points that awaken you to look into the minutiae of day-to-day life, to the roles of everyone who is there, I think that this is already a great gain for the school if the process is taken seriously, finally, and it is logical, that this is gradual (E.4.C) (FESTA, 2019, p.227).

An enormous training potential, because it triggers people's needs beyond the actions both for schools with their teams or with families, to enter into training processes, in processes of reflection, research, and deepening on issues that indirectly also are reflected in this practice (E.4.C) (FESTA, 2019, p.227).

However, it is essential to point out that among the conclusions of the study carried out is the question of the need for continuity and deepening of the formative actions of the SME concerning AIP in São Paulo, not only in questions related to how the process is carried out (in terms of operational), but especially in supporting the units to contextualize their daily practices, based on dense reflective exercises and, based on them, in the execution of concrete transformations in the educational practices that we aim to qualify.

This question is essential, since the AIP continues to be a recurrent action in the Early Childhood EUs until the present time and, from what we have news, the training actions do not occur with the same power and regularity as those carried out during the effective study.

We argue that the desired transformation depends, above all, on the training processes being triggered by the different areas of administration to

[...] Broaden the debate, going beyond the discussion of everyday practices, aiming to discuss, in-depth, the concepts, values, and practices constituted by each educator who is part of the collective of early childhood education institutions, to review and reconstruction of their beliefs, and doing so under the protection of the basic principles of quality education (FESTA, 2019, p.256)

It is also essential to emphasize that the “achievement” of quality is always in process and depends, simultaneously, on each and everyone involved in the educational action, so it cannot be expected that involvement in transformation processes will occur spontaneously and generally, without the support of adequate training processes.

In this way, looking for quality based on the analysis of the actions developed in the daily life of the institutions, in a perspective of action investigation, aimed at transformation, must be an ethical commitment of all the actors involved in the care of children and their families (from the educators directly responsible for actions developed with children, to managers who implement public policies for childhood education at the government level).

REFERENCES

ALARCÃO, Isabel. (ORG.) - Formação reflexiva de professores - estratégias de supervisão. Editora Porto. Porto, Portugal, 1996. [ Links ]

BETINI, Geraldo Antonio. Avaliação Institucional Participativa em Escolas Públicas de Ensino Fundamental. EDUCAÇÃO: Teoria e Prática - v. 20, n.35, jul.-dez.-2010,São Paulo: Rio Claro: p.117-132. Disponível em <Disponível em http://www.periodicos.rc.biblioteca.unesp.br/index.php/ educacao/article/view/4089/3296 >. Acesso em 11/07/2016 [ Links ]

BRASIL. Constituição(1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Básica. Indicadores da Qualidade na Educação Infantil / Ministério da Educação/Secretaria da Educação Básica - Brasília: MEC/SEB, 2009 [ Links ]

CAMPOS, Maria Malta; RIBEIRO, Bruna. Avaliação institucional participativa em unidades de educação infantil da rede municipal de São Paulo II. São Paulo: FCC, vol. 48.2016. [ Links ]

CAMPOS, Maria Malta; RIBEIRO, Bruna. Avaliação institucional participativa em unidades de educação infantil da rede municipal de São Paulo. São Paulo: FCC. Vol.51. 2017. [ Links ]

CAPPELLETTI, Isabel Franchi. Avaliação de currículo: limites e possibilidades. In CAPPELLETTI,I. S..(Org). Avaliação de políticas e práticas educacionais. São Paulo: Editora Articulação Universidade/ Escola. 2002. [ Links ]

DAY, Christopher. Desenvolvimento profissional de professores: os desafios da aprendizagem permanente. Porto: Porto Editora: 2001 [ Links ]

FESTA, Meire. Autoavaliação Institucional Participativa da Educação Infantil da Cidade de São Paulo: o processo sob a ótica dos participantes.. Tese (Doutorado em educação, Universidade de São Paulo). São Paulo, 2019. Disponível em: https://teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/48/48134/tde-01082019-154513/pt-br.php [ Links ]

FORMOSINHO,João.; MACHADO, João. Equipas Educativas. Para uma nova organização da escola. Porto: Porto Editora: 2009. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da Autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. Paz e Terra, São Paulo. 25.ed. Janeiro, 1996. [ Links ]

FREITAS, Luiz. C. de. Qualidade negociada: avaliação e contraregulação na escola pública. Educação & Sociedade, vol. 26, núm. 92, outubro, 2005, pp. 911-933. [ Links ]

FREITAS, Luiz.C. A importância da avaliação: em defesa de uma responsabilização participativa. Em Aberto, Brasília, v. 29, n. 96p. 127-139, maio/ago. 2016. [ Links ]

GARUTTI, Selson. A perspectiva da formação do conceito do professor reflexivo. VIIIIEncontro Internacional de Produção Científica Cesumar. CESUMAR, Centro Universitário de Maringá. Maringá: Editora CESUMAR. 2011. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.cesumar.br/prppge/pesquisa/epcc2011/anais/selson%20_garutti1.pdf . Acesso em20/01/2018. [ Links ]

KISHIMOTO, Tizuko M.. O sentido da profissionalidade par o educador da infância. In: BARBOSA, Raquel Lazzarini Leite (org.). (Org.). Trajetórias e perspectivas de formação de educadores. 1ed. São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2004, v. 1, p. 329-345. [ Links ]

MELO, Rodrigo Eiró de Queiroz. Autoavaliação e melhoria: pressupostos organizacionais. Revista Portuguesa de Investigação Educacional, vol. 14, 2014, pp. 99-116. [ Links ]

MORO, Catarina. Avaliação de contexto e políticas públicas para a educação infantil. Laplage em Revista (Sorocaba), vol.3, n.1, jan.-abr. 2017, p.44-56. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Isolina.; SERRAZINA, Lurdes. A reflexão e professor como investigador. In: GRUPO DE TRABALHO DE INVESTIGAÇÃO - GTI (Org.). Reflectir e Investigar sobre a prática profissional. Lisboa: APM, 2002. p. 29-42. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://apm.pt/files/127552_gti2002_art_pp29-42_49c770d5d8245.pdf >. Acesso em: 27 ago. 2018. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA-FORMOSINHO ,Julia ; KISHIMOTO,Tizuko.(orgs) Formação em Contexto. Uma estratégia de Integração. São Paulo: Thomson 2002. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA-FORMOSINHO, Julia.(Org.) A supervisão na formação de professores. Porto: porto Editora, 2002. Vol1-2. (Coleção infância , 7 e 8). [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA-FORMOSINHO, Júlia; Pedagogia(s) da infância: reconstruindo uma práxis de participação. In OLIVEIRA-FORMOSINHO, Júlia KISHIMOTO, Tizuco; PINAZZA, Monica (Org.). Pedagogia(s) da infância: dialogando com o passado construindo o futuro. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas. 2007. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA- FORMOSINHO, Julia. A Avaliação da Qualidade Como Garantia do Impacto da Provisão na Educação de Infância. 2009, p.9-22. In BETRAM, T; PASCAL, C. Desenvolvendo a qualidade em parcerias. Portugal: Ministério da Educação. [ Links ]

PINAZZA. Mônica A. Formação profissional de educação infantil em contextos integrados: informes de uma investigação-ação. 2014, 408 p. Tese de Livre docência. Universidade de São Paulo. São Paulo, 2014. [ Links ]

PINAZZA. Mônica A. Encontro de Gestores. Material de apoio à formação de gestores da Secretaria Municipal de Educação de São Bernardo do Campo. São Bernardo: 2013, documento mimeografado. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (SP). Indicadores de Qualidade da Educação Infantil Paulistana. São Paulo: Secretaria Municipal de Educação /DOT, 2015. (versão preliminar abr. 2015). [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (SP). Orientação normativa nº 01/2013 : avaliação na educação infantil : aprimorando os olhares Secretaria Municipal de Educação. Diretoria de Orientação Técnica.- Secretaria Municipal de Educação. - São Paulo: SME / DOT, 2014 [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (SP). Secretaria Municipal de Educação. Diretoria de Orientação Técnica. Programa Mais Educação São Paulo: subsídios 4: Avaliação para a aprendizagem-externa e em larga escala. São Paulo: SME/DOT, 2015a. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO (SP). Portaria 5.930 de 14 de outubro de 2013. Regulamenta o Decreto nº 54.452, de 10/10/13, que institui, na Secretaria Municipal de Educação, o Programa de Reorganização Curricular e Administrativa, Ampliação e Fortalecimento da Rede Municipal de Ensino de São Paulo - “Mais Educação São Paulo”. 2013. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Secretaria Municipal de Educação. Indicadores de Qualidade da Educação Infantil Paulistana. Secretaria Municipal de Educação. Diretoria de Orientação Técnica. São Paulo: SME / DOT, 2016. [ Links ]

SORDI, Mara Regina Lemes Di. A complexidade das relações sociais na escola: problematizando as resistências ao processo de avaliação institucional. In SOUZA, Eliana da Silva; SORDI, Mara Regina Lemes Di;(Org) Avaliação Institucional como instância mediadora da qualidade da escola pública: a rede municipal de educação de Campinas como espaço de aprendizagem. Campinas/SP: Millennium editora, 2009p.35-38 [ Links ]

SORDI, Mara Regina Lemes Di. Entendendo as lógicas da avaliação Institucional para dar sentido ao contexto interpretativo. In VILLAS BOAS, Benigna Maria de Freitas. Avaliação : políticas e práticas. São Paulo: Papirus Editora. Coleção Magistério: formação e trabalho pedagógico. 2002. P.65-82 [ Links ]

SORDI, Mara Regina Lemes Di; SOUZA, Eliana da. (Org) Avaliação Institucional como Instância Mediadora da Qualidade da Escola Pública: o processo de implementação na rede municipal de Campinas em destaque. Campinas: Prefeitura Municipal de Campinas.2012, vol 2. [ Links ]

SORDI, Mara.R.L. Há espaços para a negociação em políticas de regulação da qualidade da escola pública? EDUCAÇÃO: Teoria e Prática - v. 20, n.35, jul.-dez.-2010, Rio Claro, SP, Brasil. p. 147-162. [ Links ]

SORDI, Mara R.L; FREITAS, Luiz.C. Responsabilização participativa. Revista Retratos da Escola, Brasília, v. 7, n. 12, p. 87-99, jan./jun. 2013. Disponível em: <Disponível em: http://www.esforce.org.br >. Acesso em 27/11/2018. [ Links ]

SOUZA, Sandra Zakia. Avaliação institucional: elementos para discussão. In GUARULHOS. Secretaria da Educação de Guarulhos. Revista Avaliação educacional. Abril 2012, p.46-47. [ Links ]

TERRASÊCA, Manuela. Autoavaliação, avaliação externa… afinal para que serve a avaliação das escolas?. Cad. Cedes, Campinas, v. 36, n. 99, p. 155-174, maio-ago., 2016. [ Links ]

1In this study, the term 'educators' includes all professionals who are part of the team of educational units, by 'managers' are identified professionals who work specifically in the direction, pedagogical coordination and as assistant principal and the term 'teachers' is used to refer specifically to the professionals who carry out daily teaching with children.

2The monitored units correspond to 71.9% of the total number of early childhood education units linked to the SME, since official data indicate that there are (on 11/20/2016) 2600 units, divided into 13 Regional Education Directorates (REDs).

4The municipal document (SÃO PAULO, 2016) is divided into nine quality dimensions, with 32 quality indicators that contain, in total, 189 guiding questions for the evaluation. The constant dimensions in this instrument are: a) dimension 1: educational planning and management; b) dimension 2: participation, listening and authorship of babies and children; c) dimension 3: multiplicity of experiences and languages in ludic contexts for childhood; d) dimension 4: interactions; e) dimension 5: ethnic-racial and gender relations; f) dimension 6: educational environments: times, spaces and materials; g) dimension 7: promotion of health and well-being: experiences of being cared, taking care of oneself, others and the world; h) dimension 8: training and working conditions of male and female educators; i) dimension 9: sociocultural protection network: educational unit, family, community and city.

5In this category (educators) of the table of the answers to the questionnaire are included as teachers (13% of the total), pedagogical coordinators (38%), principals (43%), assistant principals (5%) and professionals who perform other roles (1 %).

6This classification results from the analysis of the proposed indicators, the questions that should be answered to assign the colors of the indicators and also from the introductory note of each dimension, contained in the Quality Indicators (SÃO PAULO,2016).

11Non-profit entities manage institutions that serve children in kindergarten in the city of São Paulo-SP in partnership with the PMSP, with the EU administration being the responsibility of these institutions, but having the transfer of funds from the public power to maintain this attendance.

13In the municipality of São Paulo-SP, school supervisors, although not linked to a single educational unit, are responsible for monitoring the actions developed in these institutions, as they aim to implement current public policies.

The translation of this article into English was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES/Brasil.

ETHICAL PROCEDURES

38The authors declare that there is formal consent from the interviewees to use the data obtained in the study, which are available for consultation.

39We inform that both the research and its report (available in full at https://teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/48/48134/tde-01082019-154513/pt-br.php) were approved by the ethics committee from the University of São Paulo. The institution's code of ethics can be consulted at https://edisciplinas.usp.br/mod/page/view.php?id=3372100.

Received: April 20, 2022; Accepted: October 03, 2022

texto en

texto en