Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.40 Belo Horizonte 2024 Epub 20-Ene-2024

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469838823

Relacionado con: 10.1590/SciELOPreprints.3805

ARTICLE

NETWORKED FEMINISM: THE ONLINE AND OFFLINE MILITANCY OF THREE YOUNG FEMALE TEACHERS1

1Universidade do Estado de Minas Gerais (UEMG). Ibirité, MG, Brasil.

2Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG). Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil.

The article investigates the militant practices of three young female teachers, active in multiple agendas and who use social media as a venue of resistance. Data were collected from a netnography carried out on these teachers' Facebook networks, followed by an interview. We submitted an ethical-political study, based on the concept of ethics by Michel Foucault. We understand that the teachers recognize their moral obligation to resist and defend, responding to a specific type of feminism, a networked feminism, which is based on alliances with other struggles. The teachers seem to bring tension to the school and its curriculum with themes and agendas of resistance and militancy, which generates debates. In addition, we identified a militant experience shaped by practices that rely on the transforming power of the small constraints and tensions produced in social networks and in life styles, and that are exposing attempts to degrade truths that are hard to be destabilized.

Keywords: Militancy; feminisms; teaching; ethics and politics; netnography

O artigo perscruta práticas de militâncias de três jovens professoras, atuantes em múltiplas pautas e que fazem uso das redes sociais como lócus de resistência. Os dados foram obtidos em uma netnografia realizada na rede social Facebook dessas professoras, seguida por entrevista. Propusemos um estudo ético-político, fundamentado no conceito de ética em Michel Foucault. Consideramos que as professoras reconhecem a obrigação moral de lutar e defender, respondendo a um tipo específico de feminismo, um feminismo de rede, que se dá a partir das alianças com as demais lutas. As professoras parecem tensionar a escola e o currículo escolar com temas e pautas de luta e de militância, o que provoca debates. Além disso, identificamos uma experiência de militância constituída por práticas que apostam na potência transformadora dos pequenos constrangimentos e tensionamentos produzidos nas redes sociais e nos modos de vida, e que estão revelando tentativas de corroer verdades difíceis de serem desestabilizadas.

Palavras-chave: Militância; feminismos; docência; ética e política; netnografia

El artículo examina prácticas de militancias de tres jóvenes profesoras, actuantes en múltiples pautas y que usan las redes sociales como lugar de resistencia. Los datos fueron obtenidos en una netnografía realizada en la red social Facebook de estas profesoras, seguida por entrevista. Propusimos un estudio ético-político, fundamentado en el concepto de ética de Michel Foucault. Consideramos que las profesoras reconocen la obligación moral de luchar y defender, respondiendo a un tipo específico de feminismo, un feminismo de red, que viene a partir de las alianzas con las otras luchas. Las profesoras parecen tensionar la escuela y el currículo escolar con temas y pautas de lucha y militancia, lo que provoca debates. Además, identificamos una experiencia de militancia constituida por prácticas que apuestan en la potencia transformadora de tensionar y avergonzar de forma sutil que se produce en las redes sociales y en los modos de vida, y que están revelando intentos de corroer verdades difíciles de desestabilizar.

Palabras clave: Militancia; feminismos; docencia; ética y política; netnografía

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the variety of social resistance have multiplied and got updated. Movements such as the so-called Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street and many others were originated in the digital environment and spread through the streets, indicating new modes of action (CASTELLS, 2013). The movement of June 2013, in Brazil, was no different, since it has characterized the inseparability between the uses of digital media and the new modes of political action.

In this circumstance, militant teachers face up other issues in their own way of making militancy, in other words, the virtual environment and the streets have become the new challenges. Contemporary mobilizations for education coexist with the ebullience of movements to occupy the streets, with call to action through social networks and with the explosion of agendas that involve subjectivities. This scenario calls for other ways of acting: solidary, connected, networked.

This article presents the results of a thesis interested in investigating the militant practices of three young female teachers, active in multiple agendas and who use the Facebook network as a venue of resistance. The three teachers surveyed were aged between 32 and 34, were in their first years of teaching militancy and worked in public schools in Belo Horizonte and the metropolitan area: Zaida is a Geography teacher in Elementary Education; Marcela is a history teacher, also in elementary school; and Samara is a high school Physical Education teacher. Zaida, Marcela and Samara are fictitious names.

These teachers have similar attributes with regard to militancy: they are affiliated with political parties and respond to calls from unions, but, above all, they respond to calls from contemporary movements: they take to the streets to defend issues of work and rights social; but they also take to the streets to defend different life styles. They are active teachers and use social networks as a possibility of resistance. Among the agendas they publish on social media, we find school, public education and the teaching profession; also, feminisms, LGBT clamors, anti-racist struggles, among other causes that have shared nowadays's landscape of movements and mobilizations of the present2.

Methodologically, the resource used was netnography, defined by Kozinets (2014, p. 10) as “a specialized form of ethnography adapted to the specific contingencies of today's social worlds mediated by computers”. For this author, among the ethical and methodological precepts that guide netnography, there are conventional notions of research ethics, such as user consent, reaching broader issues that concern autonomy, authorship and the right to privacy of users of the virtual space. Aware of these precepts, we observed the teachers' Facebook networks, checking the records from the period between January 2015 and December 2019. From this monitoring, we selected speeches and militant practices that they published on the social network.

Following the netnographic research, we carried out an interview with each one of them. In the research, the netnography and the interview were taken as part of a single method - a hybrid method -, since what was apprehended from the teachers' militant experience is the objectivation of what they published on social networks and what they said about the published content.

From a philosophical point of view, we resort to Foucault's theories, using the author's tools to apprehend today's issues. From the dilemmas of the present, Michel Foucault sought to elaborate a history of forms of thought, using, for that, the retreat to the past, in the search to understand the conditions of emergence of what is said today. Especially in the final phase of his studies, what he presents to us is the potency of the ethical-political relationship to think about the present, which takes place in bodies, in experiences and in resistance struggles. With Foucault's lens, what we proposed in the research was an ethical-political study, understanding contemporary militancy as an experience.

When we talk about experience, it is important to understand that it takes place in the field of ethics, understood as a relationship with oneself, meaning a way of self-formation, a way of being, a process of subjectivation. The processes of subjectivation, in their turn, are connected to the ways of conducting oneself and the other; they are therefore political.

In his latest studies, Foucault (2009; 2010) considers the ways of behaving as a field of experience, by relating the ways in which the individual constitutes himself as a moral subject of his actions and the implications of this in the relationship with others. On this point, Foucault (2009, p. 34) offers us an important elucidation in History of Sexuality II, when he states that,

[...] “moral” is also understood to mean the actual behavior of individuals in relation to the rules and values proposed to them: it is thus designated the way in which they submit more or less completely to a principle of conduct; by which they obey or resist a prohibition or a prescription; by which they respect or neglect a set of values; the study of this aspect of morality must determine in what way, and with what margins of variation or transgression, individuals or groups conduct themselves in reference to a prescriptive system that is explicitly or implicitly given in their culture, and from which they have a more or less clear conscience.

Thus, Foucault (2010, p. 310) considers that we have different ways of conducting ourselves through certain codes of action, so that “what we call morality is the effective behavior of people” and involves the relationship with oneself and with the other. Anchored in Greek ethics, the author considers that this moral conduct goes through four main aspects, which can be taken as an analytical tool for the ethical-political study: the first of them is what the philosopher calls ethical substance and which seeks to respond to the question “What aspect or part of me or my behavior is related to moral conduct?” (FOUCAULT, 2010, p. 308). Ethical substance has nothing to do with essence, but with the matter worked on by ethics; it is the way in which the individual constitutes himself as a matter of his moral conduct.

The second aspect is the mode of subjection or “the way in which people are called or incited to recognize their moral obligations”. In the mode of subjection is placed the “attempt to give existence the most beautiful form possible” (FOUCAULT, 2010, p. 309). It is an aesthetic way, a stylistic existence, it is a choice for a certain way of existing. It goes through the way in which the individual relates to the rules of his conduct and obliges himself to put them into practice.

The third aspect of the relationship with oneself is an activity of self-formation, of self-practice, of elaboration of ethical work, of austerity, which seeks to answer: “what are the means by which we can change ourselves to become ethical subjects?” (FOUCAULT, 2010, p. 310). They are practices of austerity, since they imply an exercise of oneself over oneself, a work of self-formation that intends to achieve a certain way of being, a certain way of transforming oneself into a moral subject of one's conduct.

Finally, the fourth aspect is the teleology of the moral subject or purpose, which is based on the following question: “what kind of being do we aspire to when we behave in accordance with morality?” (FOUCAULT, 2010, p. 310). The purpose indicates which constitution is aimed at conforming a certain way of being characteristic of the moral subject. It is in this sense that,

[...] to be called “moral” an action must not be reduced to an act or a series of acts conforming to a rule, law or value. It is true that every moral action involves a relation to the reality in which it is carried out, and a relation to the code to which it refers; but it also implies a certain relation to oneself; this relationship is not simply “self-consciousness”, but the constitution of oneself as a “moral subject”, in which the individual limits the part of himself that constitutes the object of this moral practice, defines his position in relation to the precept he respects, establishes for itself a certain way of being that will count as moral realization of itself; and, for that, he acts on himself, seeks to know himself, controls himself, puts himself to the test, perfects himself, transforms himself (FOUCAULT, 2009, p. 37).

In Foucault's, the constitution of oneself as a moral subject goes through the bonds, at least, between ethics, politics and the truthful saying (FOUCAULT, 2011). And what is the strength of these bonds? Inspired by Foucault, a series of studies tend to look for such bonds in contemporary movements and mobilizations. They are movements, demonstrations, struggles, causes that bring with them, or demand, an incisive refusal, which manifests itself in bodies and in ways of life. Movements that show the explosive power of the courage of the truth, fundamentally when they launch in their agendas traces that they are in search of rupture, of the transgression of what normalizes and conforms.

The young militant teachers we investigated are teachers and militants who seem to us to be strongly connected to this strength of courage: they take part in street movements; they resist and defend multiple agendas, with multiple focuses; experience the “female spring” and feminisms; use social media intensively. Among its causes is the struggle for education, but also movements in which subjectivities are latent.

We refer, then, to the ethical framework that Foucault presents, in order to address the elements that are at stake in the teachers' experience of themselves. In other words, we are interested in looking at this militant teaching, trying to identify which ethical substance it is bonded to, which modes of subjection conform its stylistics, which self-training work is in place and what the researched teachers aspire to when they carry out the militant work, thus creating a unique experience.

When experiencing this ethical framework in the research, we were able to infer that the experience of militancy of the researched teachers works, as far as possible, as an orientation, a way of living; in it, there are imperatives, rules, practices and statements that, although not necessarily new, are triggered in the act of militancy. They are: resist and defend causes and agendas of themselves and others; enlist your body in the political struggle; take to the streets, denounce, live up to what you say; act together with those who fight your fights.

Our concern in this article is, therefore, following these ethical-political orientations, showing a possible ethical framework for female teachers and, consequently, reviewing their political effects.

RESIST AND DEFEND CAUSES AND AGENDAS OF YOURSELVES AND OTHERS

Inspired by the formulations of Foucauldian ethics and taking ethical substance as a reference, as mentioned earlier, we identified a principle that incites teachers to live a militant life, working as a calling, a summons, an ethical concern that is very strongly presented to the young teachers surveyed, that is, resist and defend causes and agendas of yourselves and others.

Expressions such as a fight, we fight, I fight reveal the verb that summons teachers' militancy to do their ethical work: to fight. In the set of what they published on Facebook and what they said during the interview, the verb to fight appears many times along with the verbs to defend, to transform and to resist: they struggle to defend, they struggle to transform, they struggle to resist: They struggle to defend the causes of workers, the poor, the so-called identity minorities and all those who suffer injustice.

In the speeches of Samara, Zaida and Marcela, we found elements inherited from the historical conjuncture studied by Éder Sader (1988), when researching the progression of popular movements in the region of São Paulo, between the 1970s and 1980s. Such conjuncture when "new characters come to the scene" bringing to light a discursive reorientation of the left, a reordering of the Catholic Church for social issues and the assumption of a new unionism. In the teachers' speeches, it is possible to identify argumentations that move between agendas based on Marxism, unionism, Christian liberation, social justice, necessary community engagement and, of course, new subjectivities.

Samara, Zaida and Marcela are teachers who respond to union calls, get involved in teachers' strike movements, and are supportive of labor movements from other categories. They are ready to resist and defend male and female workers.

Thus, the contemporary call for resistance and defense seems to be composed of the inheritance of an combination of discourses. In addition to labor issues, resisting and defending also involves ideas of the common good, the culture of peace, social justice, revolution, collectiveness... Marcela's speech well represents the functioning of these ideas in her calling to militancy:

[...] I believe in a society where people will live with more justice, where the means of production will be shared more fairly and equally, where people will have more opportunities, and where the basics of life will not be denied or negotiated, as quality healthcare, an education that is liberating, that is for a culture of peace, that is progressive, the right to housing, leisure, culture (MARCELA, 2018 - interview excerpt).

In this thread though, it is also possible to identify that the activism of the teachers responds to an ethical call for resistance to hateful, retrograde, discriminatory, institutionalized speeches, as well as those located in social networks and in everyday relationships. Activism that presents itself strongly in the fight against machoism, sexism, LGBT phobia, racism, among others. In the agendas they defend, there is the idea of a range of rights in several directions.

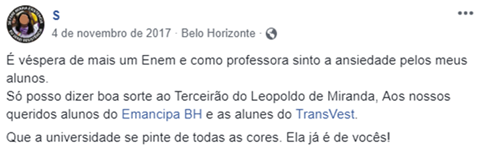

When they turn to the fight and defense of education in a more specific way, we again see the broadening of the agendas. On the one hand, they fight and defend agendas that involve wages, working conditions, better infrastructure, among others. On the other hand, they introduce new subjects in this struggle. Samara, for example, says that she wants “the university to paint itself in all colors”, referring to the entrance, in Higher Education, of her public school students, of low-income students who attend the popular prep course in which she works (Emancipa) and also the “TransVest students” (exclusive pre-university course for transvestites and transsexuals), denouncing the exclusion of this population from school and higher education courses.

Source: Samara’s Facebook, 04 nov. 2017.

Translation: It's the eve of another Enem Exams and as a teacher I feel anxiety for my students.

I can only say good luck to the Third Year of Leopoldo de Miranda, to our dear students of the "Emancipate" BH and the students of the Transvest.

May the university be painted in all colors. It already belongs to you!

Picture 1 - May the university be painted in all colors

To live a militant life today, for the teachers, is to be open to the struggle of others, a solidary call to issues of inequalities, but also of identities. This call, however, is not new; it emerges in the explosive 1960s, with movements that required other ways of being and living. Here, we highlight the fact that Foucault (2006) identified, in the 1960s, the awakening of the political vision to what made up the struggles that were considered to be minor: sexuality, gender, ethnicity, ecology. Issues that were outside the political activism practiced until then and that began to arouse people's interest. Issues that, in contemporary times, have been presented as a strength for causes, movements, street demonstrations, activism.

By answering the call to fight and defense as a militant life, understood as an expansion and embracement of different struggles, the teachers, just as Laclau (1986) did, question the limits of the notion of class struggle, expanding this notion that is still very precious for union activism. Thus, as Foucault (2015) taught us, teachers emphasize multiplicity more than isolated struggles. And more: it is with the female body that they present themselves to the diversity of these struggles. For them, it is only possible to respond to a call for a militant life, by expanding the struggles for feminism, a discussion that we will see below.

ENLIST YOUR BODY IN THE POLITICAL STRUGGLE

For the female teachers, no one is obligated or required to be militant, but for those who choose this path, there seems to be an imperative: if you want to fight and defend, enlist your body in politics! The trail we follow is that, through feminism, young female teachers present their bodies to the public scene and respond to the call to fight. Through feminism, they recognize a moral obligation to fight and defend. The feminism practiced by the teachers seems to be the mode of subjection, the way they invest their energies and their moral obligations in the struggles they carry out.

Feminism is defined by Margaret McLaren (2016) as a movement with broad positions and theoretical references, but which is based on the fight against the various forms of subordination of women. The feminist movement has formed an alliance with other struggles, such as the LGBT movement, the black movement and many others. In addition, feminism is also a practice, as it considers theory to be relevant to the female experience.

Currently, there is a whole literature that is concerned with presenting the different feminisms, as did McLaren (2016). Our intention, in this article, was to verify how the researched teachers achieve their struggle and defense obligations through a practiced feminism.

Teacher Zaida, for example, refers to the organization of women as another form of struggle against capitalism, against oppression, in favor of freedom and the right to be a woman. Below is an excerpt from a post, in which the teacher suggests an alliance between women, which refers to the idea of sisterhood or a relationship of sisterhood, alliance, affection or friendship between women:

The pain of each one of us is overwhelming, too strong to be transformed into numbers. (...) Let's be there for each other. Let's all be against this system that subjugates us. (...) I do not accept this capitalism that destroys us every day. I want freedom for all of us, not one less, and a society where not one is lying in the street, crying in despair. (ZAIDA - Facebook, 20 set. 2016).

For her part, teacher Samara is dedicated to feminism in her activism practices, especially in relation to the LGBT cause. In this case, activism for others is inherent to her own life. In the following excerpt, Samara refers to her sexuality as a political act, as a flag of struggle and resistance to social norms that seek to impose ways of being and acting.

Being a lesbian woman is a political act. Talking about who we are in a sexist, LGBT phobic, racist society, full of so many prejudices, is to position ourselves on which side we are. (...) We are women who love other women. And we'll talk about our loves because that's normal. Because we will talk about it even in politics (SAMARA - Facebook, 22 mai. 2018).

Teacher Marcela is the mother of two children, born in 2017 and 2019, respectively. During this period, issues involving motherhood were the subject of many of her reflections, especially with regard to the woman-mother's power of action. In her publications, Marcela presents the daily issues experienced by women as a call to resist. In many of these posts, she mentions real situations in our country, such as violence and lack of social support, suffered mainly by mothers in situations of greater poverty.

Marcela, Zaida and Samara also frequently post on their social media issues related to the liberation of women's bodies, whether from the point of view of abuse, inequality or female pleasure. Another type of publication that gains prominence among the active militancy of teachers is that which concerns the denunciation of situations of violence suffered by women.

We can say that Samara, Zaida and Marcela speak, each one, from their own experience, but they have in common the fact that they trigger feminism as a political act. Topics such as violence against women, free and safe abortion, female empowerment and support networks among women are regular topics that the teachers post on Facebook. From these problems, they establish their militancy practices.

This way, they resist and denounce gender issues, straining social relations. They make it clear that the feminism of this militancy is constituted from everyday issues, from lives lived, from the difficulties and urgencies that women face. It is also a feminism constituted from theories, such as gender studies developed in recent decades; of women's institutional political practices; of growing feminist engagement on social media3. For this reason, our bet is that the researched teachers respond to a networked feminism, an expression invented to say that they share an experience of feminism with multiple connections, they are in the fight for the life lived, they are in social networks - which is also interspersed by the historical, political, academic, everyday practices and experiences - and do not renounce the broad spaces and forms of struggle. It seems that the combination of everyday issues experienced by women, their urgencies, their needs and their limits, that is, the set of their struggles, is the material with which the militant teachers feed and conduct their political practices.

TAKE TO THE STREETS, SPEAK OUT, LIVE UP TO WHAT YOU SAY

The concern now is to present the practices with which the teachers respond to this network feminism, which striggles are at stake in virtual militancy; and what struggles are at stake in the pursuit of militancy as a way of life, which includes teaching. In pursuing these practices, we base ourselves on the third element of Foucauldian ethics, austerity, which Foucault (2010) refers to as an activity of self-training, a practice of the self, an elaboration of ethical work, that is, a battle of the subject about his/her self in order to become a certain kind of person.

Between what the teachers published on Facebook and what they said during the interview, we can find feminist practices of liking, sharing and posting, in which we identify the overlapping of online life and offline life, which occurs through the dissemination of feminist discourses on social networks and their effects on lived life.

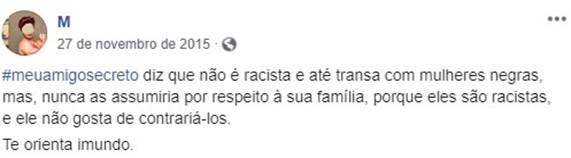

Fabiana Martinez (2019) suggests that the emergence of the use of social networks and the dynamicity of online connections have produced new narratives for feminism. The author endorses that, like the vast majority of social movements, feminism spreads through the networks, using multiple platforms to disseminate, generate, promote its agendas and demands and, thus, also transforms itself. As an example of the feminist role of teachers in social networks, we can mention the engagement in virtual campaigns4. These campaigns help to think about the growth of collective support networks for women in the virtual space and in the discourses they put into dissemination, such as not blaming victims of violence. In the social networks of Samara, Zaida and Marcela, we find campaigns, such as #meuamigosecreto:

Source: Marcela's Facebook, 27 nov. 2015.

Translation: #mysecretfriend says he is not racist and even has sex with black women but would never publically acknowledge them out of respect for his family, because they are racist and he doesn't like to contradict them.

Seek orientation, filthy.

Picture 2 - Campaign #meuamigosecreto ( my secret friend )

Virtual campaigns are among the practices that are common on social networks and generally refer to movements whose agendas require engagement. Certainly, these virtual practices have strength because they are spontaneous and collective, reaching people who do not need to identify themselves as feminists to engage.

Samara, Zaida and Marcela are militants who act intensively through social networks, but also respond to calls for mobilization and take to the streets 5. What they put into practice is a relationship between digital media and street politics, which presumes the constitution of a performative environment. The militant aesthetic of the bodies that occupy the streets is composed of posters, catchphrases and performances. This is important, as the inherent relationship between social networks and movements is based on imagery, therefore, it requires photographs, videos and sounds. It is also an aesthetic of seeing and being seen, as shown in figures 3 and 4:

Source: Zaida's Facebook , 15 mai. 2019.

Translation: More than 100,000 young people and workers took to the streets today! Against

social welfare reform and against Bolsonaro's cuts!

Picture 3 - Zaida, 15 mai. 2019 - BH

Source: Samara's Facebook, 15 mai. 2019.

Translation: Youth is revolution!

Still ecstatic about today's act and the wonderful wave of youth!

We are together with more than 250 thousand people on the streets of BH

Picture 4 - Samara, 15 mai. 2019 - BH

Paradoxically, it is important to consider that the uses of digital networks that intersect causes, agendas, movements are present in broad human relationships and are effectively inserted in our daily lives. From this angle, the digital environment that we operate on a daily basis has been an important instrument for the world of capital and consumer relations. Advertising and advertising strategies dominate digital marketing and its dynamic updates. Therefore, the same digital media that leverage movements and expand speech venues are also at the service of consumption and marketing logic.

These consumption and marketing logics are intrinsic to neoliberal rationality. Dardot and Laval (2016, p. 17), in The New Reason of the World, treat neoliberalism as a rationality, that is, a “set of discourses, practices and devices that determine a new way of governing men according to the universal principle of the competition”. The authors refer to Foucault (2008) who, in Birth of Biopolitics, dealt with an archeogenealogy of neoliberal thought, reconstructing the conditions of emergence of liberal thought in the 18th century, to show the displacements promoted by neoliberalism in the post-World War II period.

For Dardot and Laval (2016), neoliberalism is the rationality that structures and organizes the action of the rulers, but, above all, of the ruled; it is the “reason of contemporary capitalism”. This rationality works because neoliberalism develops “the logic of the market as a generalized normative logic, from the State to the most intimate of subjectivity” (DARDOT; LAVAL, 2016, p. 34). It is the logic of market construction based on competition, which is the general norm of economic practices.

Escape from the neoliberal rationality indicated by Dardot and Laval (2016) involves the constitution of alternative forms of subjectivation to the model of entrepreneurship of the self, of competition. For the authors, the possible counter-conduct to this rationality requires another way of conducting oneself and the other, it requires an ethical and political link that proposes another way of being.

If we are in a neoliberal rationality that is of the order of competition, of acting as a self-enterprise, of taking advantage of opportunities and that operates in the field of what seems to be free choice, it is important to know to what extent the practices of Samara, Zaida and Marcela respond to this rationale and/or point to another.

Obviously, Samara, Zaida and Marcela respond to the questions that gain the most of engagement on social networks, trigger the most cited and shared hashtags and, thus, are in the battle game of trending topics. They are users of social networks in a context in which digital marketing has taught them how to attract followers, likes for posts and a whole set of engagement metrics and competition between profiles6. What we can highlight, however, is that their practices suggest possibilities of escaping neoliberal capture, as they seek to live their militancy as an ethos, as a way of life; to the extent that their practices indicate an inherent relationship between what they say and the way they live.

Samara, Zaida and Marcela have in common the fact that the stories and events they report, in which they identify a transformation of themselves, shape the way of being of each of them, as they impact the choices they make. They seem to work on a daily basis for coherence between what they say and the way they live.

Tomamos como exemplo a relação de Marcela com o Sistema Único de Saúde, o SUS. A sua opção pelo uso do SUS é consonante com seu discurso de luta e defesa dos serviços públicos. Durante a entrevista, ela relata:

It's hard to imagine that someone who has never ridden a bus can say how good or bad public transportation will be, right? Or the person who doesn't go to the SUS when stomach hurts, when has kidney colic, [...] how will one measure the quality of that care. So, it is my choice too, to live the public life, to live everything that is public and this is part of my life and the life of my family (MARCELA, 2018 - interview excerpt).

Marcela reiterates her use of the SUS as a choice and not as a financial impossibility of contracting the private system. In general, the type of defense of the SUS that Marcela practices is only possible because she effectively uses public health services. It is the speech of a militant who knows the reality of what she says, listens horizontally, lives and speaks her truth.

The search for coherence between what they say and the way they live also seems to manifest itself in the way in which the teachers practice their teaching. Between what they published on social networks and what they said during the interview, they left some clues as to how struggle and militancy agendas reach the school. An example of this is the way in which Marcela reports her pregnancy as a period of curiosity and reconciliation with her teenage students. The pregnant body of the teacher, future single mother, raised questions like “don't you have a husband?”. From questions like this, Marcela reports the opportunity to raise the debate on sexuality, on ways to prevent pregnancy; but also about female choices, about different family structures, about feminism. When questioned about her relationship with the students, Marcela considers teaching to be an activity that cannot be exercised impartially, neutrally, and, therefore, in an apolitical way:

But I can't imagine a teacher being someone so tough in the classroom that the students never know anything about who he or she really is or what he or she thinks. I think that the teacher is not that professional of total impartiality, because we are about human work [...] they are human beings relating to human beings, with their successes and failures and with their certainties and uncertainties as well. I think that the greatest privilege we have in our work is the capacity for human involvement that we have, I think that makes all the difference (MARCELA, 2018 - interview excerpt).

Samara also states how her militancy reaches the classroom. A process that completely escapes the idea of indoctrination, of converting the students to what she takes as truth, but which goes through the very way she lives. Samara says that she is guided in the field of Physical Education by the idea of body culture, according to which bodies are political and have identity:

In Physical Education, we have a set of philosophical and pedagogical streams on how to order the discussion of the body. I have been following for many years, by choice, body culture, as an orientation on how to act pedagogically, and it is a Marxist stream, it is a stream that we have been studying for many years and building in Brazil, since the times of 1980. And then, one of the things, and this is a bit in line with the LGBTIQ debate, which we also advanced a lot, is that the body produces culture, it produces and reflects the space you build, that way you experience yourself in society. So our body, it is political, this political body assumes an identity, it assumes a space and assumes how it identifies itself and how it is reflected in society (SAMARA, 2018 - interview excerpt).

Being a militant teacher marks in a certain way the way these teachers work with their specific contents in the daily life of the school. Samara, for example, reported the attention she devotes in her classes to machoism, racism and LGBT phobia in sports practices. The teacher reports that the work with these themes has been well received by the school, by the student body, but she does not fail to consider that situations of discrimination happen in the school environment, noticeably with young people who are outside heteronormativity.

On this matter, it is interesting to present Zaida's statement about a class council, in which she shows the resistance that certain themes encounter within the school's walls, even among male and female teachers. Zaida's astonishment, then in her first year of teaching, seems to be with the naturalization of discriminatory speeches among her co-workers. She is faced with practices in which sexuality and religiosity that escape the norm try to be ruled, even if only by attributing a bad school evaluation. The teacher reports:

Today, during the class council at the school where I work in the mornings, they held a criticism session about an undisciplined student. The criticism was related to the fact that the student was a lesbian. (...) I remember the first time I saw this student in the classroom, she started a conversation and already managed to get into the subject that she attracted women, I reacted naturally, I didn't show astonishment. She never behaved to me in the defiant way the other teachers reported today. About a group of friends from the second year, they said that they formed the “lgbt trio”, because now their subject was just about that. And this was placed as a complaint in the class council. The lowest grade of the lgbt trio in geography was 23 out of 25. About a third-year gay student and Umbandist student, it was said with irony “Dandara, now he wants to be called Dandara”. Another one who rocks on the grades and the subject, but openly demonstrates his sexual and religious orientation (Facebook social network Zaida, 04 Aug. 2018).

About this statement, Zaida comments: “I see how conservative the school is. I honestly didn’t know how big it was” (ZAIDA, 2018 - interview excerpt). And she adds:

I think the teacher's role is to be much deeper than just passing on the content, teaching a lot of things like that. Even more so in this context that we live in, in this whole lot of repression, right? [...] Like I said in the post, a teacher making a complaint in a class council, for a student to be repressed for their LGBT matters? These boys are LGBT, what are they going to talk about? It is their life, they are teenagers (ZAIDA, 2018 - interview excerpt).

By taking to teaching what they believe and defend, the three teachers practice a scanning of the school environment that is very close to the militant way in which they see the world. Between the teaching practices and the way they live, we find stories in which they try to embody what they say, which looks like an orientation, an ethical conduct, which is manifested in the choices they make, in what they accept and what they renounce, in the way they talk. This happens, above all, in the act of life, in everyday choices; which also involves resistance, deviations, difficulties.

Thus, it is necessary to consider that the researched activist teachers are fully inserted in a kind of “digital panopticism”, as Tony Hara (2019) refers to, and certainly running the risks that this implies. But we identified that they are part of a movement of people who are interested in transforming their own lives and are committed to solidarity and cooperation practices, and, even in the virtual world, they show the way they live.

In the end, it is necessary to consider that, if networked feminism includes the resistance and defense on a multiplicity of causes and agendas, it points to a struggle that is feminist, but that does not end with this cause. Seems like the feminist practices of these militant teachers require what is common, displacing practices and discourses in the sense of announcing the possibility of emancipation for all men and women. In this sense, the purpose of these teachers' struggle becomes the requirement that we live our lives in fair conditions. Is this the meaning of contemporary feminisms? Do feminist practices alone point to a struggle of common order, in rupture with identity rigidity?

The following section is interested in these questions: after all, what is the purpose of this type of militancy? What do the militant teachers in this research actually want with their practices?

ACT ALONG WITH THOSE WHO FIGHT YOUR FIGHTS

This part leads us to the fourth element of Foucauldian ethics, which is the teleology of the moral subject or the purpose. In Foucault (2010, p. 310), this aspect discusses the conditions that one aims for by conforming to a certain way of being, characteristic of the moral subject.

We start off from the question: what do the militant teachers want with their feminist resistance and practices? In a quick answer, we can say that they want “another world”. They talk about what Veiga-Neto (2012, p. 273) identifies as convergence between activism and militancy, which is of the order of “acting forward, action for a change of status, action for another situation, different from what you have”. Or, even, about a manifest or latent desire for change, which is what Nogueira (2012) indicates as a common attribute among multiform, multiparty militancy, defenders of multiple causes. Quite often - in the captions of their photos, texts and comments they post, as well as in what they said during the interview - Samara, Zaida and Marcela declare the desire for a better world, another world. They claim that they want to transform the system and society and thus change the world; they aim for a fair life, a school that transforms, a social change.

This desire to change or transform the world, expressed by the teachers, seems to be related to the most intimate aspect of the purpose of the militancy they practice, since, to a certain extent, what they say refers to a desire for change that comes from the very life of each of them.

Samara, Zaida and Marcela are women who have accessed higher education courses and trained as teachers; they were able to problematize the relationships between poverty, social classes, racial issues, sexuality; became feminists. When talking about themselves, they go back to elements that place them on the side of the said minorities, highlighting their difficulties. Zaida and Marcela are black women, they were born and raised in the hoods and have always had a simple life history. Samara, on the other hand, lived in a middle-class neighborhood in Belém do Pará and studied in private schools, but the fact that she is a lesbian puts her life alongside those who suffer more intensely from vulnerabilities.

When they talk about themselves, they speak the truth of those who suffered prejudice, discrimination or had to overcome the difficulties imposed by social inequality or sexual difference. This inspires us to think of a purpose for this type of militancy, which is about telling one's own truth, shouting one's own cry and, thus, questioning what causes injustice, inequality and pain.

But we can also say that their militancy practices also work as a way to make them recognize, in their own bodies, the vulnerability of the other. In many stories, their own pain, struggles and vulnerabilities seem to be what motivates these women to fight for the desire for another world: the chance for Samara not surviving in this society that kills LGBT people or the overwhelming pain of “each one of us” (Women? Black? from the hoods?) to which Zaida refers. They talk about themselves, but they speak in the plural, they resort to a we, to an idea of pain and collective struggle. Thus, the purpose of the fight that desires another world is only possible by joining everyone against what makes them vulnerable and hurts.

On this matter, we turn to Butler (2018), in Bodies in alliance and the politics of the streets: notes for a performative theory of assembly. The author proposes a reflection on the idea of meeting and assembly in neoliberal societies, indicating the formation of collective alliances, in an ethics of cohabitation in public spaces. In addition, she argues that mass demonstrations - such as those in Tahrir Square and the Occupy movements - have shaped a collective rejection to the social and economic precariousness shared by those who live in vulnerable situations, configuring the bodily demand to live healthier lives, more livable ones . Thus, the issue that touches political struggles, to which Butler (2018) dedicates his research, is the claim that vulnerable bodies in precarious conditions can live lives that are possible to be lived, so that lives may have social and democratic conditions of being lived together. It is a kind of joint action whose purpose is to minimize the unfeasibility experienced by certain bodies, by certain lives.

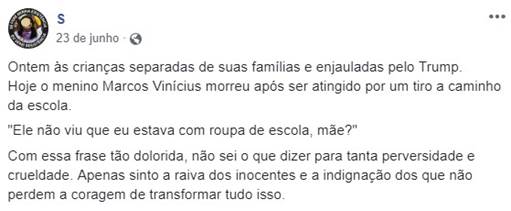

It seems that this type of alliance, which implies an ethical commitment to the other, is at work in the militancy of the teachers, to the extent that they recognize the precariousness of the other in their own bodies. This alliance action is at work when they engage in feminist denunciation campaigns on the internet, for example. Or in the sense of the following post, when Samara expresses her indignation at the impracticability of certain lives and, thus, allies herself with these bodies, with these pains and with these struggles.

Source: Samara's Facebook, 23 jun. 2018

Translation: Yesterday the children separated from their families and caged by Trump.

Today the boy Marcos Vinicius died after being shot on his way to school.

"Didn't he see I was in school clothes, Mom?"

With this painful sentence, I don't know what to say to so much perversity and cruelty. I just feel the anger of the innocent and the indignation of those who don't lose the courage to transform all of this.

Picture 5 - I feel the anger of the innocent

From this point on, the sense of resisting and defending that the teachers practice in their militancy seems to materialize in the imperative to bring everyone together against what makes them vulnerable and what hurts themselves and others. That's why they don't get tired of saying: don't leave anyone out, fight for everyone.

We need to consider that this all and everyone, as observed by Butler (2018), can have an excluding character that defines who is inside and who is outside this distinction. In his words, “even when we say ‘all’, in an effort to propose a group that includes everyone, we are still making implicit assumptions about who is included” (BUTLER, 2018, p. 10).

But Butler (2018, p. 10) also considers that “inclusiveness is not the only objective of democratic politics”, so that the exclusionary character that is present in any movement does not make unfeasible the fact that meetings and assemblies are important political prerogatives for the right of people to say whatever they have to say. Thus, when female teachers meet, on the streets or virtually, with people who are saying the same as them, they are exercising the right to appear and make demands together, with others, and they are exercising the political purpose of their struggles.

In this way, the purpose of the teachers' militancy seems to be to act together with those who fight on their side, their struggles. This purpose may be related to a type of militant pleasure that is not new and involves the joy of acting together with those who fight the same struggles, of engaging in meaningful action.

Finally, what the militant teachers in the research seem to intend with their practices is to be someone who acts, they want to be part of the solution to the problem.

SOME CONSIDERATIONS

As we stated, the experience of militancy of the researched teachers seems to work as a kind of guidance on how to live: resist and defend causes and agendas of yourselves and others; enlist your body in the political struggle; take to the streets, denounce, live up to what you say; act together with those who fight your fights. Following the trails of a Foucaultian ethical framework, these statements try to conform the dynamism of the struggles waged by the teachers. It's as if they were saying: I fight and defend myself, minorities, I expose my female body, I occupy all places, including virtual ones, I make alliances and make collective connections. Roughly speaking, this seems to sum up the ethical way in which these young militant teachers throw themselves into politics.

Based on this ethics, the militancy that the teachers bring to the classroom is also more or less guided by these guidelines, although it is not carried out in the same way as they do in other spaces. One of the questions that guided the research was to understand how the militant teachers live the task of updating the teaching class mobilizations. By locating among the practices of networked feminism the solidary struggle for a multiplicity of causes and agendas, we identified that, when these militancies reach the school, they trigger the sayings that built the mobilizations from the new unionism that emerged in the 1970s, as a collective struggle and unification by the base.

The researched teachers play at school the role of raising the debate on the agendas of the working class struggle. They are among the people who usually explain, clarify, point out the risks, the ongoing attacks on social rights; they are the ones who usually summon their colleagues to mobilize against salary arrears, for the salary adjustment to inflation indicators, among other agendas. In the way they conduct themselves, there is a militant action: they want to be someone who acts and resists the attacks on education. But this action is significant only for a portion of the collective of workers and this, obviously, generates tensions, constraints.

But we also verified that this is a type of militancy experience that is causing another type of embarrassment among their peers. Samara, Zaida and Marcela are teachers who are questioning, identifying, denouncing, pointing out situations of machoism, prejudice and discrimination in the daily life of the school. We can therefore state that the experience of militancy that responds to networked feminism is attentive to these situations: it questions the use of naturalized terms that carry prejudice; requires non-sexist language in everyday communications; proposes the inclusion of topics on diversity in school projects, among others. With these small constraints, these teachers cause small transformations in the spaces in which they work.

Another question that guided the research was to understand what the militant teachers offer to the students. After all, do the focuses, agendas, movements for which they fight and which they defend enter by the front door of the school? First, it must be said that Samara, Zaida and Marcela left evidence of the disaffection between militancy and teaching within the school's walls. In a certain sense, they indicate the inconsistency between the promise of transformation of society by the school - the “change of the world” - and what they practice in the classroom. Repeatedly, they make reference to the need to transform the school institution, even though they do not indicate ways and/or possibilities beyond the “interest of the rulers”, “effective public policies”, “investment in education”.

But we can say that the way they practice teaching puts tension in the school's curriculum, especially when they introduce themes that speak of the so-called minorities, such as the fight against racism, the defense of equal rights between genders, the critical view on consumption, respect for diversity and many others.

These themes practiced at school or outside of it, as we tried to say, are not excluded from a solidarity action that is liked, produced, published and/or shared on social networks. We also bet on the power of these small practices in this space. Of course, we are aware of the dangers of using social networks, since, among other issues, they have become a space for the dissemination of hate speech and the propagation of fake news, many of them by mass messaging, by robots. However, the militancy of the teachers in social networks is, we believe, in the building of possibilities, as an attempt to produce resistance.

Faced with the risks and dangers of this type of militancy, what seems to us is that such an experience is assigned to the task of leading and being led. It is part of a game that involves constraints and tensions in wide spaces, so that, trying to escape neoliberal appeals, it calls on minorities to think and act differently, undermining the logic of consumption, proposing other ways of presenting the body. It is an experience that is in the effervescence of the construction of other ways of re-existing.

Finally, what is being generated in this experience? There is a movement of people that is consolidating a path of no return. We are at a time when people are no longer willing to renounce who they are in favor of the norm. This demands rearrangements, new ways of making party politics that combine with differences, other ways of being militant, other ways of being a teacher, other school curriculum. It demands the creation of solidary forms of life, based on the power of collective decision, which have as a meaning the alliance between all bodies and all lives. Collectively, we have the power of displacements of discourses, which start to indicate the possibility of an ethical subjectivity that is of the order of alliance. This seems to be the direction of the fights that are taking place.

We know, however, that it is still too early to draw any conclusions, all we have today is the realization that the movement is ongoing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Programa de Capacitação de Recursos Humanos (PCRH) - FAPEMIG.

REFERENCES

BELELI, Iara; PELÚCIO, Larissa. Aperte o play para começar: desafios metodológicos de pesquisas nas mídias digitais. In.: DURÃO, Suzana; FRANÇA, Isadora(Orgs.). Pensar como método. Rio de Janeiro: Papéis Selvagens, 2018, p. 117-143. [ Links ]

BUTLER, Judith. Corpos em aliança e a política das ruas: notas para uma teoria performativa de assembleia. Trad. Fernanda Siqueira Miguens. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2018. [ Links ]

CASTELLS, Manuel. Redes de indignação e esperança: movimentos sociais na era da internet. Trad. Carlos Alberto Medeiros. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2013. [ Links ]

DARDOT, Pierre; LAVAL, Christian. A nova razão do mundo: ensaio sobre a sociedade neoliberal. Trad. Mariana Echalar. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2016. [ Links ]

FACCHINI, Regina; CARMO, Íris Nery do; LIMA, Stephanie Pereira. Movimentos Feminista, Negro e LGBTI no Brasil: sujeitos, teias e enquadramentos. Educação & Sociedade, v. 41, p. 1-22, 2020. <https://doi.org/10.1590/ES.230408> [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Carolina Branco de Castro. Feminismos web: linhas de ação e maneiras de atuação no debate feminista contemporâneo. Cadernos Pagu, p. 199-228, 2015. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1809-4449201500440199> [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Ética, sexualidade e política (Ditos e escritos V). Organização e seleção de textos de Manoel Barros da Motta; tradução Elisa Monteiro, Inês Autram Dourado Barbosa. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2006. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Nascimento da Biopolítica: curso no Collège de France (1979). Trad. Eduardo Brandão. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2008. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. História da sexualidade II: o uso dos prazeres. Trad. Maria Thereza da Costa Albuquerque. 13. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Graal, 2009. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Michel Foucault entrevistado por Hubert L. Dreyfus e Paul Rabinow. In: DREYFUS, Hubert, L; RABINOW, Paul. Michel Foucault uma trajetória filosófica: para além do estruturalismo e da hermenêutica. Trad. Vera Portocarrero e Gilda Gomes Carneiro. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária , 2010, p. 296-327. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. A coragem da verdade - o governo de si e dos outros II: curso no Collège de France (1983-1984). Trad. Eduardo Brandão. São Paulo: Martins Fontes , 2011. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. A sociedade punitiva: curso no Collège de France (1972-1973). Trad. Ivone C. Benedetti. São Paulo: Martins Fontes , 2015. [ Links ]

GOMES, Carla de Castro. Corpo e emoção no protesto feminista: a Marcha das Vadias do Rio de Janeiro. Sexualidad, Salud y Sociedad, p. 231-255, 2017. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1984-6487.sess.2017.25.12.a> [ Links ]

HARA, Tony. Fuga da peste, do sujeito e do deserto. In: RAGO, Margareth; PELEGRINI, Maurício (Orgs.). Neoliberalismo, feminismo e contracondutas: perspectivas foucaultianas. São Paulo: Intermeios, 2019, p. 291-318. [ Links ]

KOZINETS. Robert. Netnografia: realizando pesquisa etnográfica online. Trad. Daniel Bueno. Porto Alegre: Penso, 2014. [ Links ]

LACLAU, Ernesto. Os novos movimentos sociais e a pluralidade do social. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Socais. São Paulo, v. 1, n. 2, out., 1986, s/p. Disponível em:<https://www.corais.org/sites/default/files/01a_laclau_-_os_novos_movimentos_sociais_e_a_pluralidade_do_social.pdf>. [ Links ]

MARTINEZ, Fabiana. Feminismos em movimento no ciberespaço. Cadernos Pagu, n. 56, p. 1-34, 2019. <https://doi.org/10.1590/18094449201900560012> [ Links ]

McLAREN, Margaret A. Foucault, feminismo e subjetividade. Trad. Newton Milanez. São Paulo: Intermeios , 2016. [ Links ]

MEYER, Dagmar; PARAÍSO, Marlucy. Metodologias de pesquisa pós-críticas em educação. Belo Horizonte: Mazza, 2012. [ Links ]

NOGUEIRA, Marco Aurélio. Da militância política, e além - participação política no brasil. Café Filosófico Instituto CPFL. Campinas, Tv Cultura, 26 abr. 2012. Programa de Tv. Disponível em:<http://www.institutocpfl.org.br/play/vimeo-video/marco-aurelio-nogueira-da-militancia-e-alem/>. [ Links ]

SADER, Eder. Quando novos personagens entraram em cena: experiências, falas e lutas dos trabalhadores da grande São Paulo, 1970-80. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1988. [ Links ]

VEIGA-NETO, AlfredoÉ preciso ir aos porões. Revista Brasileira de Educação. Rio de Janeiro, v. 17, n. 50, maio-ago., p. 267-282, 2012. <https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782012000200002> [ Links ]

1The translation of this article into English was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq/Brasil.

2On the forms of organization of the black, feminist and LGBT movements and their contemporary relationship with social networks, see: Facchini, Carmo e Lima (2020).

3On the use of social networks as a space for action and reflection by feminist groups, see Ferreira (2015).

4Virtual campaigns have worked as one of the strategies for the online feminist field of action. Martinez (2019) lists some campaigns such as Chega de FiuFiu (2013) and Vamos Juntas? (2015), whose agenda was questioning and denouncing the naturalization of situations of harassment suffered by women in public spaces.

5On the articulation between the forms of action in the virtual environment and the movements to occupy the streets, see Butler (2018). Specifically on the articulation of feminist mobilizations online and on the streets, see Branco (2015) and Gomes (2017).

6This competition tends to be stimulated by social media tools that allow reference to the number of views, shares, likes, etc.

Received: March 18, 2022; preprint: March 21, 2022; Accepted: February 06, 2023

texto en

texto en