Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Educação em Revista

versión impresa ISSN 0102-4698versión On-line ISSN 1982-6621

Educ. rev. vol.40 Belo Horizonte 2024 Epub 20-Ene-2024

https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-469838961

Relacionado con: 10.1590/SciELOPreprints.3831

ARTICLE

STUDENT PERMANENCE IN DISTANCE LEARNING PEDAGOGY COURSES: A STUDY FROM THE OPEN UNIVERSITY OF BRAZIL

1 Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS). Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul (RS), Brasil.

Distance Education (DE) is growing rapidly in Brazil and nowadays it comprises more than a third of all enrollments in undergraduate programs (BRASIL, 2022a). However, the high dropout rates put pressure on Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to define strategies to promote the permanence of their students until graduation. In this sense, this research was structured from the need to look at the institutions and to evaluate the way they are committed to the permanence of the students in distance learning. This research aims to identify and analyze how the HEIs affiliated with the Open University of Brazil (UAB) promote the permanence of students in the Pedagogy (teacher training) distance learning programs. For this purpose, eight semi-structured interviews were conducted with coordinators of six different HEIs, and institutional documents were analyzed. Both the understanding of the managers’ statements and the analysis of the documents emphasized that the institutions have different levels of commitment to the consolidation of distance education, which reflects directly on their performance to mitigate the dropout of students. Based on the identification of weaknesses of the programs, as well as on the good practices referred to in the literature, guidelines were presented that aim to promote the permanence of students in the contexts investigated.

Keywords: Student permanence; pedagogy; distance education; Open University of Brazil

A Educação a Distância (EaD) cresce de forma acelerada no Brasil e hoje compreende mais de um terço de todas as matrículas em cursos de graduação (BRASIL, 2022a). Porém, os altos índices de evasão pressionam as Instituições de Ensino Superior (IES) a definirem estratégias para promover a permanência de seus discentes até a diplomação. Neste sentido, a presente pesquisa foi estruturada a partir da necessidade de se olhar para as instituições e avaliar de que modo estão comprometidas com a permanência discente na modalidade. Esta investigação objetiva identificar e analisar de que forma as IES, vinculadas ao sistema da Universidade Aberta do Brasil (UAB), promovem a permanência discente em cursos de Pedagogia a distância. Para isso, foram realizadas oito entrevistas semiestruturadas com coordenadores de seis IES distintas, além da análise de documentos institucionais. A compreensão dos depoimentos dos gestores e a análise documental enfatizaram que as instituições possuem diferentes níveis de comprometimento com a consolidação da modalidade a distância, o que reflete diretamente sua atuação para mitigar a evasão dos estudantes. A partir da identificação de fragilidades nos cursos, bem como de boas práticas referidas na literatura, foram apresentadas diretrizes que almejam promover a permanência dos discentes nos contextos investigados.

Palavras-chave: Permanência discente; pedagogia; educação a distância; Universidade Aberta do Brasil

La Educación a Distancia (EaD) está creciendo rápidamente en Brasil, y hoy comprende más de un tercio de todas las matrículas en cursos de graduación (BRASIL, 2022a). Sin embargo, las altas tasas de deserción presionan a las Instituciones de Educación Superior (IES) a definir estrategias para promover la permanencia de sus estudiantes hasta la graduación. En ese sentido, esta investigación se estructuró a partir de la necesidad de mirar las instituciones y evaluar cómo se comprometen con la permanencia de los estudiantes en la modalidad. Esta investigación objetiva identificar y analizar cómo las IES, vinculadas al sistema de la Universidad Abierta de Brasil (UAB), promueven la permanencia de los estudiantes en los cursos de Pedagogía a distancia. Para ello se realizaron ocho entrevistas semiestructuradas a coordinadores de seis IES diferentes, además del análisis de documentos institucionales. La comprensión de los discursos de los directivos y el análisis documental destacaron que las instituciones tienen diferentes niveles de compromiso con la consolidación de la modalidad a distancia, lo que se refleja directamente en sus acciones para mitigar la deserción de los estudiantes. A partir de la identificación de debilidades en los cursos, así como de buenas prácticas reportadas en la literatura, fueron presentadas orientaciones que tienen como objetivo promover la permanencia de los estudiantes en los contextos investigados.

Palabras clave: Permanencia estudiantil; pedagogía; educación a distancia; Universidad Abierta de Brasil

INITIAL REFLECTIONS

Distance education has been gaining more and more space in the Brazilian Higher Education scenario. Data from the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (INEP) show that, in 2021, more than 3.7 million were enrolled in distance learning undergraduate courses, which represented more than 41% of the total academic records in this modality of teaching that year (BRASIL, 2022a).

The Higher Education Census (BRASIL, 2023) shows that, in 2021, the number of individuals enrolled in distance learning degrees (1,004,915) is 56% greater than the number of subjects enrolled in face-to-face degrees (643,413). This information is important as it makes it possible to understand the centrality of distance learning in teacher training in the country. Within this context, Pedagogy courses have greater numerical expressiveness: in 2021, 390 courses were registered, totaling 598,341 enrollments, representing 59% of total enrollments in distance learning degrees, and 16% about the number of degrees in this modality. Also, the number of Pedagogy graduates is also the most significant, with 125,229 records in the year the survey was carried out (BRASIL, 2022b).

However, regardless of the course or type of Education, student dropout is a reality in Higher Education. The Lobo Institute (SILVA FILHO, 2017) published data that corroborates this statement. According to the report from this institute, in the face-to-face modality, annual dropout rates remained relatively stable for associate degrees, bachelor's degrees, and technological courses, at 20, 21, and 37%, respectively, and in the distance modality the percentages rose from 28 to 39% in associate degrees, from 25 to 33% in bachelor's degrees, and remained at 49% in technological courses, from 2011 to 2015.

Other research also pays attention to the impacts of educational dropout in distance learning. The study by Maia, Meirelles, and Pela (2004) showed that, of the 22 Brazilian HEIs that provided data on their courses, the average dropout rate in the modality was 30% per year. According to the 2018 EaD.br Census (ABED, 2019), from the Brazilian Association of Distance Education, the percentage of institutions that offer entirely distance learning courses, with a dropout rate between 26 and 50%, increased from 6% in 2017 to 22.2% in 2018. Possible explanations for this significant growth are: “the excess supply of courses and the dizzying growth in the number of enrollments - which, consequently, increase the probability of dropout -, as well as closer monitoring of these fees by institutions” (ABED, 2019, p. 65).

Considering the Latin American context and the general performance of Higher Education in the countries of this bloc, around half of the population between 25 and 29 years old who entered higher education do not complete it because the subjects they are still linked to institutions, or because they evade it (INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT/THE WORLD BANK, 2017). The study carried out by Soso, Kampff, and Machado (2023), based on data from the Brazilian Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations, in the period between 2013 and 2021, and in the annals of the Latin American Congress on Abandonment in Higher Education, in its editions from 2011 to 2021, confirm the weaknesses in the completion rates of Higher Education in the Latin American context, pointing to the need for greater involvement of Higher Education Institutions in the creation of policies to favor the retention and graduation of students, especially in Distance Learning Education.

The phenomenon of student dropout is complex and multifactorial, which means that different studies may consider discrepant factors to measure it, making it difficult to calculate absolute rates. However, a consensus seems to emerge from the literature: when the two teaching modalities are compared, both present dropout rates at worrying levels, and Distance Education has the highest rates of this phenomenon. Student abandonment is alarming in every sense, especially in a context in which Distance Education grows considerably every year.

To a better understanding of this phenomenon, it is necessary to articulate an investigation that analyzes whether Higher Education Institutions are committed, from their structuring documents to promoting student retention. To this end, this study uses the scope of a Pedagogy undergraduate course in distance learning due to the large volume of students. It is proposed to investigate in the context of the Universidade Aberta do Brasil, a government initiative of great relevance in Brazilian public Distance Education.

As the objective is to look exclusively at institutional management and its different constituent elements, it is considered that Cislaghi's (2008) contributions express the desired approach to Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). According to the author, student retention is the “[...] situation in which the student maintains interest, motivation and finds at the HEI the conditions that he considers essential to continue regularly attending the undergraduate course he entered” (CISLAGHI, 2008, p. 5). The considerations of this author and his model for undergraduate student retention (CISLAGHI, 2008, p. 74) were central to the elaboration of the data collection instrument developed for the research described in this article and, subsequently, for the organization of the analysis and discussion of the results.

Therefore, this investigation aims to identify and analyze how Higher Education Institutions, linked to the Universidade Aberta do Brasil, promote student retention in distance Pedagogy courses.

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH

This investigation with a qualitative and exploratory nature, linked to the master's degree in education, had as its research universe six public Higher Education Institutions in the southern region linked to UAB and involved the study of various aspects of their distance Pedagogy courses. The project was submitted and approved by the Scientific Committee of the University promoting the research, with a letter of consent from the Board of Directors of Distance Education of the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES- Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) - Ministry of Education (MEC), the foundation responsible for the organization of the UAB System.

The data collection process began with semi-structured interviews with course coordinators, Distance Education coordinators, and the Universidade Aberta do Brasil at the institutions. These professionals were chosen due to their proximity to the courses analyzed to provide an accurate understanding of institutional actions to promote retention. All interviewed managers registered their agreement to participate in the research through an Informed Consent Form (ICF). The interviews were carried out remotely, using videoconferencing software and they were recorded and transcribed with the permission of the interviewee. The type of semi-structured interview was chosen, as it “characterizes a script with open questions and is recommended for studying a phenomenon with a specific population”, in addition to allowing “flexibility in the sequence of presenting questions to the interviewee” (MANZINI, 2012, p. 156).

The interview script was prepared considering the contributions of Manzini (2003, 2004) on the organization and formulation of questions and the theoretical considerations on student retention by Kember (1995 apud SANTOS, 2020, p. 65-66), Tinto (1997) and Cislaghi (2008). The document consists of a set of 13 questions, some composite, that ask the participant to identify, describe, and evaluate aspects of their performance of colleagues and the institution where they work.

The initial questions were formulated to get to know the respondent and the context of the activity and enter the topic of the interview. The first thematic block, following Cislaghi's (2008) considerations on the permanence model, refers to issues of the institutional environment, such as mechanisms for monitoring students' trajectories and dropout rates, forms of social and academic interaction, institutional actions to inform students at the time of entry and to promote retention. The second thematic block aims to understand how the institution provides students with spaces to verbalize their perception of satisfaction with the course and the institution, an important aspect to avoid dropping out. The third block refers to the external environment and how the institution can support the student concerning their issues. These questions were prepared to analyze how professionals perceive existing actions to promote student retention in their context of activity.

In addition to conducting the interviews, we collected institutional documents considered important to the topic under study. A priori, the documents considered for analysis were the Pedagogical Project of the Course (PPC) and the Institutional Development Plan (PDI), basic elements for the accreditation of institutions and course offerings. However, upon recommendation from managers at the time of the interviews, the results of the institutional assessment completed by students and teachers were incorporated into the corpus of analysis, based on the report prepared by the Own Assessment Committee (CPA- Comissão Própria de Avaliação). Such documents, publicly accessible and found on institutional websites, were analyzed based on interviews with managers, generating subsidies that enriched the discussion of the results. With this, it was possible to identify whether there were policies at the institutional level that encourage student retention and whether the managers' statements represent actions structured in these documents.

The content of the interviews was examined using the methodology proposed by Alves and Silva (1992), based on a qualitative analysis system. Given the large volume of information generated after transcribing the interviews, the authors emphasize the need to revisit the research assumptions. The qualitative analysis method, according to them, consists of an initial reading phase in which the researcher must be “impregnated” by the data collected, and, in this process, relationships between different points of the discourse and with the base literature emerge. To ensure that no information is missed, the authors recommend to record the different interpretations.

The literature on the topic is a fundamental anchor for the interview analysis process, as the reflections that relate to the interviewees' statements are extracted. According to Alves and Silva (1992), this conversation exercise between the research literature and the collected data depends greatly on the researcher's experience and his perception when meeting all this information. “Gradually the analysis takes place, and the researcher begins to work on deepening the data that will be contained in a structure, guided by the theme and central questions” (ALVES; SILVA, 1992, p. 67).

ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

Six public Higher Education Institutions participated in the research. The data collected consists of 8 interviews with managers (carried out between September 15th and October 20th, 2020), in which 5 were coordinators of distance Pedagogy courses, 1 was coordinator of Distance Education, 1 was a coordinator of the Universidade Aberta do Brasil of one of the institutions involved and 1 manager who accumulates these last two functions; in addition to 18 documents, including Institutional Development Plans, Pedagogical Projects of the Course and professor and student evaluation reports.

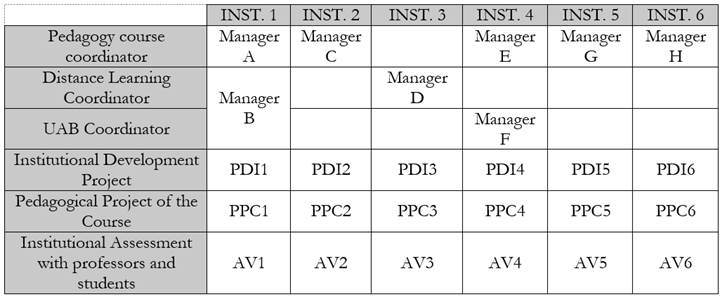

To preserve the identity of the individuals and institutions involved in the investigation, an alphanumeric system (Box 1) was organized to reference, throughout the text, the origin of the data collected. It is important to highlight that the male gender was used to designate interviewees of both genders, despite most of the participants being female (6).

The interviews took place remotely and lasted about 60 minutes. Managers were invited to answer a set of questions from basic questions regarding their performance to specific questions regarding student retention. Such questions were organized into groups, according to the 3 dimensions of Cislaghi's model (2008), which is how the analysis is presented in this section. The managers' notes, together with the institutional documents and reviewed literature, constitute the essence of the content presented in the following paragraphs.

The initial part of the interviews was made up of introductory questions that aimed to find out how long the individuals had been working in management. All interviewees demonstrated that they had extensive experience with distance higher education, even if, at times, they had recently taken over management. In summary, the managers’ working time is:

Manager A: participated in the proposal to develop the Distance Learning Pedagogy course at his institution and has been in charge of the coordination for more than 6 years;

Manager B: has worked as a coordinator for almost 2 years, but has been teaching in the modality since 2009;

Manager C: has been in the coordination since 2018; however, he worked as an administrator of the Pedagogy course at another institution;

Manager D: has worked as a Distance Education coordinator for almost 5 years and, since 2018, he has been the deputy coordinator of UAB at his institution;

Manager E: has worked as a professor in the Pedagogy course for 13 years, he was previously a tutor coordinator and has been working as a distance course coordinator for almost two years;

Manager F: took over the general coordination of UAB at his institution less than 6 months ago, but has been teaching for 10 years on a distance learning degree course;

Manager G: he served as coordinator of the Pedagogy course in both modalities simultaneously at his institution for 3 years and now he has been dedicated only to managing the distance learning course for 2 years;

Manager H: has worked in Distance Education at his institution for almost 20 years and recently left the position of course coordinator, where he worked for 5 years.

Category referring to the institutional scope

After the introductory questions, interviewees were invited to answer a series of questions about elements of the institution's activities. These elements refer to the scope of institutional practices that, for this investigation, include the entry and reception of students, monitoring of the academic trajectory, the forms of integration provided during the course, monitoring of dropouts, and practices to promote permanence. Each component is divided into subsections that help to define the analyses.

Entrance and welcome of students

The first question referred to the existence of actions promoted by the courses to get to know their students when they enter the institution. These actions are highlighted as important by the literature reviewed as they enable the identification of academic incompatibility with the chosen course, in addition to pointing out possible gaps in knowledge of basic education and other factors that may put the student's retention at risk. This question is based on the theoretical models of Kember (1995 apud SANTOS, 2020, p. 65) and Tinto (1997) when considering that students carry attributes before they enter into the course that can determine the quality of their training trajectory.

Managers A and E, as course coordinators, reported holding face-to-face meetings at centers - units outside the headquarters, with a support structure for academic activities provided for in the course PPC - to welcome students and introduce them to both the institution and the course.

The course coordinator, the deputy coordinator, and two or three other professors who are available during that period usually go to these visits to talk to the students, to introduce the course proposal, what the dynamics are like, the issue of eight semesters, and face-to-face meetings (Manager A).

[...] the policy was to go to the centers, introduce the course, the university, it was always with that in-person model. [...] But I know about this movement, there was a lot of going to the centers, and then the students got to know the professor through the subject (Manager E).

Manager F, the UAB coordinator at his institution, also commented on the practice of courses promoting a moment of integration at the beginning of training but highlighted that the activity is optional: “Our idea is always to be welcomed in the first semester [...]. So, we recommend and try to help the courses as much as possible so that they can hold inaugural classes, travel to the centers, sometimes they welcome the student, explain the progress of the course, and do an activity”.

However, the speeches do not represent practices recorded in institutional documents. Some coordinators, such as interviewee B, reported that this process of welcoming and acclimatizing students takes place through a course in the first semester. Managers C and D added that this activity, in addition to providing students with knowledge about the instruments used in the modality, encourages the integration of new students.

Manager H stated that his institution does not have a specific policy for welcoming and getting to know its new students. Also, coordinator G said that this practice is only carried out in the face-to-face Pedagogy course at his institution and added: “There is no type of student assistance, or that goes to meet this student at the Universidade Aberta do Brasil so that it can be done the permanence of this student, for example” (Manager G).

What can be seen in the interviewees' responses is that, although some institutions recognize the importance of this moment of welcoming, getting to know students, and introducing them to the dynamics of the course, there is no written protocol on the organization and obligation of this practice. In general, the pedagogical projects of the courses describe a process of adaptation to the modality that occurs in the first semester as a discipline; however, this practice exists only to provide students with mastery of basic knowledge and skills regarding technological resources used, as described in the quality references for distance learning (BRASIL, 2007, p. 10).

Returning to what Lara et al. (2017) said, the causes of student dropout in the first semesters of the course are related to difficulties in adapting to university life and the methodology for developing activities, which requires access to and mastery of digital technologies. Furthermore, some students do not have study habits and have educational gaps in basic education.

What is sought, in proposing actions to welcome students, follows the same direction as what was shared by Ferreira et al. (2017) on the process of connecting students. That is, the ways of bringing the student closer to the training principles of the course, the university's operating process, and Distance Education systems; to introducing learning environments and tools in which students can interact socially and academically within and outside the course; to publicize events and projects aimed at integrating students with their educational interests; to generate actions that allow students to identify how the program they are part of adds value to their life project; establish actions with the student assistance sectors to accompany students, always paying attention to what they need, and to establish empathy to measure their connection with the course.

Monitoring the academic trajectory

This question referred to monitoring the student's academic trajectory and the variables considered in the process. In the model proposed by Cislaghi (2008), to avoid dropouts, the institution is responsible for monitoring the academic performance of students, specifically the grades obtained in the course. However, this question was posed in a broader sense since there are other qualitative issues to be considered in the academic trajectory. Following Kampff (2017) and Barbosa (2018), students value the attention and concern of course tutors and professors as a way of monitoring their academic development, in addition to providing greater rapprochement between them. The authors state that this supervision is necessary, especially about time management due to issues relating to students' personal lives, which interfere with the development of their training.

The analysis of the pedagogical projects of the courses indicated that distance tutors were responsible for this practice. Among the numerous tasks of tutoring, the PPC of Institution 4 highlights the importance of this process to prevent student dropout: “It is also the task of tutoring to promote collaborative and cooperative work between professor/researcher, professor/trainer, and professor/student, encouraging group study and motivating them during the course to avoid dropping out of school.” (PPC4, p. 10). Also, the PPC of Institution 2 highlights this as one of the tutor's duties: “Mapping, for monitoring, student access, to act preventively in the mechanisms that can trigger evasion.” (PPC2, p. 24). Despite commenting that the course does not have this supervision praxis, the manager of the same institution (Manager C) said that it is the tutors who know the students.

The same occurs in the case of Manager H: “No, we do not have a monitoring policy in this regard. What happens is that some tutors control and check which students are not participating. But we don’t have to monitor closely and create actions to try to interfere in these issues.” Manager G stated that there is no student monitoring due to the lack of human resources. However, the PPC of the course it coordinates also assigns the distance tutor the task of monitoring the students' development.

According to the considerations of Santos (2020), the development of permanence in Higher Education requires coordination between management, professors/tutors, and students, working together towards quality and equitable education for all. The aforementioned coordinators seem to have indicated a mismatch of these gears by providing the understanding that the monitoring work carried out by the tutors does not reverberate in the performance of other course professionals, that is, there is no evidence of an intentional articulation of the results of this monitoring and possible opportunities for improvement identified by tutors in work meetings with professor and coordinators, which harms not only the monitoring of students but also the promotion of retention as a whole, given the multifactorial origin of evasion and the benefits that discussion of elements present in monitoring, between different institutional actors, could bring about the improvement of academic processes in several dimensions.

The other interviewees, on the other hand, stated that the student monitoring process is carried out by the internal structures of their courses. Managers A and B, from the same institution, commented on the holding of meetings between the course coordination and the Structuring Teaching Center (NDE-Núcleo Docente Estruturante):

Student monitoring is carried out by the coordination and the course's Structuring Teaching Center, which is made up of me, as president of the NDE, and five other colleagues. In other words, we meet quarterly to evaluate student participation, whether they are carrying out the activities, what are the main difficulties in developing the activities, whether they are attending face-to-face meetings, or why they are not attending face-to-face meetings (Manager A).

Manager A, when asked about the meetings, denied the participation of the tutors, and added that they are involved in the institutional evaluation process, just like the professors. The coordinators of Institution 4 reaffirmed the work of coordination and internal structures of the course in monitoring activities. They addressed the student monitoring promoted by the course to prevent students from missing or failing subjects due to the difficulties in re-offering curricular components. Furthermore, they did not mention the role of the tutors when answering the question.

Finally, Manager D commented that, in each academic unit of the institution, there are technicians in educational matters who assist professors and tutors in monitoring students; however, he did not mention the quality of the actions promoted.

When exploring the data relating to this question, the importance of distance tutors in monitoring the academic trajectory of students is clear, including preventing student dropout. This finding is present both in some managers’ speeches who recognized the importance of tutors even without signaling what is established in the pedagogical projects, and the reviewed literature. Santos and Giraffa (2016) highlighted that the tutor is considered the link with the student and that this professional, by encouraging the student's participation, is nurturing the feeling of belonging to the course, the institution, and academic life.

The responsibilities arising from this monitoring attach even more importance to the training of the body of tutors described in the Quality References for Distance Learning, in the “Multidisciplinary Team” dimension (BRASIL, 2007, p. 22), in the Institutional Development Projects and Pedagogical Projects of the Courses. Whatever the nature of the monitoring actions promoted by coordination and other institutional structures, described very briefly by some managers, the contributions of tutors need to be integrated.

Social and academic integration

The interviews also included questions about the types of integration provided to students during their training. We inquired not only about the social ties between students and between them and the body of teachers, tutors, and course managers but also about integration movements for academic purposes, addressing, among other things, the participation of students in scientific events, projects teaching, research, and outreach.

Before considering what the managers said, it is necessary to highlight that the three theoretical models that support the construction of the interview questions understand these forms of integration as essential to the progression of students in their training. Tinto (1997) conceives social and academic integration as a complex multidimensional process that links the relationship between professors and students to the involvement provided by academic and social communities at the university level. The author suggests that:

For some students, high levels of academic engagement and resulting learning may not be enough to compensate for the feeling of social isolation; for others, sufficient levels of social integration can offset the lack of academic involvement. These students remain because of the friendly relationships they developed. The absence of any academic involvement typically leads to failure and, therefore, disengagement. (TINTO, 1997, p. 616, our translation).

Although the author recognizes the speculative nature of this statement due to the difficulties in measuring student involvement and its relationship with retention, he states that integration must be considered, as it directly impacts students' commitment to their education.

Regarding social involvement, Santos (2020) highlights the importance of providing activities that involve all actors in the academic community, generating relaxed environments with possibilities for exchanging and sharing experiences. Such actions can be planned by students to meet their training demands and to promote coexistence at the university.

Managers highlighted the importance of support centers in carrying out activities of this nature. Interviewees C and H commented that student integration occurs during face-to-face moments, but there is no specific policy for this. Manager G added: “At the centers, exclusively. At the centers there is a party, an event, the students are integrated and from there, they have the possibility of experiencing the university”.

As UAB coordinator, Manager F stated that it is important to ensure that the courses carry out the actions they consider necessary in this regard: “The courses have their specificities and needs for greater or lesser integration, so management acts to always be open to pay, so to speak, the teachers' daily wages, cars, fuel, drivers. All this assistance is rarely denied” (Manager F). Manager D (Distance Learning coordinator) attributed these integration activities to both the course and the center, affirming the role of management in encouraging practices such as the formation of study groups and other actions beyond the mandatory face-to-face moments.

On the other hand, coordinator B, in addition to mentioning face-to-face activities, admitted that actions for social integration needed to be planned in his institution's distance learning courses, involving the discussion of different themes based on culture.

Among the Pedagogical Projects of the Course analyzed, no references were found to students' social integration projects. The same happens for the Institutional Development Plans, with exceptions for the document from institution 1, which reads: “Expand integration actions for Distance Education students” (PDI1, p. 68). Despite this, there is no other information about what activities are covered or how they are intended to be carried out. The same institution, in its student evaluation report, shows some results that may be indicative of social integration. The document shows data according to a Likert scale, where 1 means very bad and 5 means very good. The questions “Face-to-face meetings, as a moment of learning and class integration, are...” and “Web conferences, as a moment of learning and class integration are [...]” (AV1, p. 3) received averages above 4 in the evaluation of the distance Pedagogy course.

The report from Institution 5 also shows an issue that appears to be related to the social integration of students. In this report, however, there is no differentiation between the courses and distance learning students are evaluated as a whole:

In question number 10, which deals with the integration of distance learning students with the University, a total of 33.33% of respondents classified this element as sufficient, 20.63% classified it as very good and 25.40% classified it as excellent, totaling 79.37% positive reviews. The average obtained by the indicator was 3.48 points, being classified as sufficient. (AV5, p. 33).

Regarding student integration for academic purposes, however, institutional documents had more to contribute. Participation in scientific events, teaching, research, and outreach projects are mainly registered in pedagogical projects as complementary activities. Issues such as student representation activities in academic directories, superior councils, course boards, and municipal councils are described; participation and presentation of works at scientific events, as well as their publication in proceedings, or academic magazines and journals; monitoring at the institution's headquarters or the center; participation in teaching, research, and outreach projects; participation in research groups; among others.

In practice, however, managers admitted that there are difficulties in integrating distance learning students. Manager B, in addition to mentioning the holding of university exhibitions promoted by the institution, commented on student participation in these projects:

We have things to improve, as I told you today, there is still a lot of progress to be made in outreach, teaching, and research projects, mainly. [...]. We have some PIBID projects, for example, PIBID institutionalized in Distance Learning. But these are still quite isolated movements, I don't have this yet institutionalized in the sense of scholarships, or participating in programs, so this still needs to mature. [...] And all of this appears in the evaluations, this reflects what students want, they need to participate more in the university. (Manager B).

When Manager B said: “[...] I don’t have this yet institutionalized in the sense of scholarships”, he commented on the fact that distance students do not have the right to be scholarship holders in these projects. Another important issue, recognized by interviewee B, is the fact that the courses do not encourage the formation of academic directories and that there are numerous actions to be carried out to involve the students in their training. Manager A, from the same institution, complemented the issue of scholarships by saying that this factor discourages student participation. The interviewee, when commenting on academic integration activities, cited extension courses and lectures held at the institution's headquarters, to which distance students are invited, in addition to encouraging group activities at the centers. Manager A added that, with the pandemic, several academic events have been promoted online, such as web conferences, workshops, and thematic lives.

Manager G, after mentioning some isolated actions of academic integration at the centers, such as the creation of a student representation and the holding of academic weeks, stated that the participation of students in teaching, research, and outreach projects at his institution depends on professors who receive scholarships and offer them to distance learning students, but there is no investment from UAB for this purpose.

At institution 4, Manager F stated that all events held at the institution's headquarters are extended to distance learning students and recognized that greater work is needed to publicize teaching, research, and extension projects so that academics are aware that they can participate.

Manager D stated that the main academic integration activity is an event that takes place at the institution's headquarters and involves students from all courses and modalities to present their work. The interviewee explained that an important management move has been to ensure that all notices open for in-person are also available to distance students, and cited, as an example, the participation of distance learning students in the Institutional Teaching Initiation Scholarship Program. (PIBID-Programa Institucional de Bolsas de Iniciação à Docência).

Managers C and H stated that there are no structured actions aimed at academic integration in the courses they coordinate. Manager C said: “There is no project, a teaching project, there is no outreach project. There is not. There is not. They don't participate. There is not. What there is, there is on paper. In the pedagogical project. But in practice it doesn’t exist” (Manager C). In the same sense, Manager H stated that there is no specific policy for academic integration activities. According to the interviewee, students are not prevented from participating in teaching, research, and outreach projects, but these actions are not publicized due to the lack of mentors.

Student evaluations from some institutions presented questions relevant to the types of integration provided throughout the course. In the report from Institution 1, questions about support for participation in scientific events, opportunities to participate in teaching, research and outreach projects, participation in student movements, and student representation had an average between 3 and 4 (regular and good) in the Pedagogy Distance Course, being flagged in the reports as points to be improved (AV1). At Institution 4, questions about opportunities to participate in events, research, and outreach projects were below the expected average. This did not happen, on the other hand, in institution 5, in which issues such as encouraging student participation in outreach actions, integration of distance learning students with the University, institutional incentives for student production and participation in internal or external events, and the participation of distance learning students in management bodies (campus/pole) had rates considered sufficient.

Student integration, as an important element for academic progression, is widely recorded in the reviewed literature. Regarding the centrality of the center and face-to-face meetings for students' social involvement, Barbosa (2018) considers that they are motivating elements for students due to the possibility of exchanges between peers, the strengthening of friendship bonds, and the alleviation of the feeling of isolation, common in distance learning courses. Araujo (2015), in his studies, seeking to identify the factors that led to student dropout, reports that more than half of his sample indicated that they missed face-to-face meetings and that they did not feel comfortable studying alone and interacting through virtual platforms. Miranda (2016), regarding the measures that could mitigate the phenomenon of evasion, stated, among other causes, the need to increase the number of face-to-face meetings.

Although managers addressed issues such as holding lectures, seminars, and events with work presentations, issues described by most pedagogical projects as complementary activities, it was evident that the most frequent comments are around student participation in teaching, research, and outreach projects. In the dialogue with the interviewees, it was noticed that each institution has a very particular context regarding the involvement of students in these projects and it was also evident that students on distance learning courses do not have the same involvement in these academic issues as students of face-to-face courses and that much still needs to be done to reduce this difference.

Evasion monitoring

The discussion in this section is about the means used by management in monitoring dropout rates. Monitoring this data is essential for all Education systems, regardless of the modality, and can provide valuable information about the quality of the practices carried out in the course, as well as the means to improve them. When addressing this issue, some managers cited practices carried out to prevent evasion.

Manager B stated that monitoring this phenomenon, in his institution, is done through the compilation of data in the SisUAB system, also mentioned by coordinators C and F. Interviewee B added that close monitoring of students is the main monitoring mechanism of dropout in his institution, including highlighting the role of tutors in this regard.

Manager D communicated that, in his institution, there is no single monitoring policy, but rather joint work in the courses, which begins with the action of the tutor.

Then it passes to coordination. From there, it is observed that if the student is not responding to the contact, the coordination tries to intervene and contact the center, with the center's coordination, as it is at the center that people get to know each other, especially in small towns. And then this attempt is made to contact and get closer to understand the student's case and, eventually, recoveries and extension of deadlines so that the student does not give up. (Manager D).

The issue of extending deadlines is due to an attempt by management to ensure that the student follows the curricular trajectory described in the PPC. Other interviewees also commented on a particularity of distance learning courses, which is the difficulty in re-offering subjects, as the courses are not continuously available in the UAB system. “Theoretically, a distance learning student could not fail, because we have no guarantee of continuous flow” (Manager E). Manager D added: “If the student fails or withdraws, they are removed from the course because we do not have an alternative to welcome them and then, at another time, for them to return. So, in Distance Learning, this is a very important factor that ends up facilitating evasion, in the evasion numbers” (Manager D).

Coordinator F explained that, although the students' employment status is monitored, each student represents a specific reality that demands management attention. He added that, in the first semesters, dropout rates are higher.

Some students think they will be able to handle the modality, and a greater flexibility in their study time, but end up not organizing and realizing that they are not students with the profile to carry out distance activities. Others, because they realize that it wasn't what they wanted, so I think that, when we don't welcome them, the possibility of this student dropping out is even greater. (Manager F).

From the same perspective, Manager A reported that the first semesters are more sensitive to the loss of students and that the main tool for combating dropout in the course is the teaching evaluation by the student, produced by the CPA: “Because the teaching evaluation by the student also monitors this issue of reasons for evasion, whether due to difficulty, lack of interest, lack of accessibility in the environment, lack of interest in the course, in other words, it has this possibility”. Manager H cited teacher evaluation by students as a means used by the course to monitor dropout rates and concluded by saying that student participation in this process is very low.

About the documents issued by the CPA, cited by interviewees A and H, the data provided in the documentation available to the public only offers an analysis of the course's situation. No matter how detailed they are, the questions are general and, therefore, the reports do not allow identifying the individual situations of the students, which could indicate the reasons for their evasion. Therefore, the data that is available to the public are not adequate tools for monitoring evasion rates.

Regarding Pedagogical Projects for Courses and Institutional Development Plans, no information was found directly related to the description of policies or evasion monitoring actions.

Promotion of student retention

This section deals with promoting student retention, both based on the mechanisms that the institution must reduce dropout rates, and based on the experience of managers when speaking about what they consider important in this process.

Manager A, addressing institutional practices to reduce dropout rates, shared that going to centers was highly encouraged before the pandemic to form study groups. Another issue raised by the coordinator regarding activities at the support centers refers to the fact that many students do not have adequate equipment to study at home. When discussing important practices related to student retention, he stated that there are a series of issues involved and pointed out some necessary changes in his institution.

Encouraging public policies that favor access to information and communication technologies. Encouraging students to establish even more a sense of belonging to the institution [...]. It is a battle, from the beginning of the course, for students to have a permanence grant, which only in-person students have. And scholarships for participation in teaching and research projects. Only in-person students can participate in university notices. (Manager A).

No mesmo sentido, o Gestor E não citou práticas que foram estruturadas no curso para a permanência discente, mas, sim, destacou a importância do polo e das disciplinas como principais fontes de manutenção dos discentes:

In the same sense, Manager E did not mention practices that were structured in the course for student retention, but rather highlighted the importance of the center and the disciplines as the main sources of student retention:

Because the centers with an active coordinator, an active teaching assistant, [...] who is there to listen to the student, welcomes the student there; the internet is working, there are computers in good condition, there is material for it [...]. Evasion is found in the most disorganized areas. [...] So we must think about distance learning, I would say that the center and discipline are the main elements of maintenance [...] (Manager E).

Manager F, from the same institution, commented on the existence of a student service center and stated that the course coordinators' commitment to maintaining direct communication with students has contributed to their retention. The Manager added: “My experience shows me that when we know a student and when we know about the infrastructure of the center, how that city is organized, it is always more positive than treating them as a group of people who are doing distance education”.

Manager C stated that, in his institution, there are no structured policies to combat dropout and shared some practices that are carried out on the course, highlighting the role of the tutor. Such practices are marked by the constant engagement of students in the effort to continue their education.

Manager D highlighted, as a mechanism for reducing dropout rates, the existence of an institutional structure that supports class planning. According to him, the diversification of methodological strategies has been one of the focuses of coordination, providing technical and technological support to professors so that they can create increasingly interesting and motivating classes for student participation. Manager D also commented that informing new students about the development of a distance learning course can make them decide more consciously about distance learning.

Managers G and H only stated what they consider important for the institution to take into consideration to promote student retention. Manager G reiterated that many of the prejudices that the distance learning modality faces come precisely from the lack of assistance policies and engagement in student training. Coordinator H stated that he did not know the exact reason for the evasion; however, he denied that the financial issue was a problem, as students have their studies subsidized by the State.

When discussing the mechanisms of their institution to reduce dropout rates, as well as what they consider important to promote student retention, the managers addressed a series of issues that are pertinent to their context of operation. Some of them are supported in the reviewed literature, such as what was commented by Manager D about providing those interested in the course with more information about the dynamics of the development of activities in the distance modality. Faria et al. (2011) highlight that it is necessary to clearly explain the prerequisites for following classes, preventing the student from being negatively surprised. Radin (2015), when interviewing managers, mentions the importance of disseminating quality information to new students and comments on encouraging the formation of study groups at the centers, as mentioned by Manager A.

Reading the institutional documents contributed to the perception that the institutions do not have specific policies to promote retention, but that there are student support structures that aim to assist in this regard, some of which were explained in the coordinators' testimony. In the documents analyzed, however, there is no mention of student support activities carried out only for distance students or that are applied in the modality. The pedagogical projects of institutions 2 and 5, mention the National Student Assistance Program (PNAES), established by Decree 7,234, of July 19, 2010, which states: “Art. 3rd PNAES must be implemented in conjunction with teaching, research and extension activities, aiming to serve students regularly enrolled in in-person undergraduate courses at federal higher education institutions” (BRASIL, 2010, p. 5).

Category referring to the student

Following Cislaghi's (2008) theoretical model for retention, the second thematic block of interviews includes characteristics intrinsic to the student. The author considers the students with their aspirations, interests, skills, and attitudes, as reflected by the following variables: commitment to the institution, which encompasses components that influence the student's perception of the HEI in which they are studying (overall satisfaction with the institution); and commitment to the objective, which involves factors that influence the student's perception of the quality of the course, the training they receive and the usefulness of the diploma based on the effort required to maintain their connection. According to research by Lemos (2017) and Barbosa (2018), student satisfaction and commitment have a positive relationship with their retention of the course.

In the words of the managers, the main mechanisms used to address these issues are the evaluations promoted by the CPA of each institution. Manager F ratified the mandatory practice and talked about how distance learning courses were gradually included in the process to evaluate issues specific to the modality. The same interviewee also commented that, eventually, courses can also apply their assessment instruments to a specific demand. Manager E, from the same institution, illustrated this fact by mentioning a process of valuing student feedback through questionnaires, reserved only for management. According to him, “This semester, [...] we already carried out a survey that came out at the beginning of May via Google Forms, with 380 respondents, a very significant sample of our students, addressing pandemic issues, work issues, and course attendance”.

The managers of Institution 1 also mentioned carrying out parallel assessments and the process of adapting the institutional assessment for distance learning courses. Manager A explained that there is an optional assessment practice for each subject that is promoted by the Distance Education Center. Subsequently, this data is presented to students so that they can analyze the potential and difficulties faced in the previous year. Manager B highlighted the process of institutionalizing the evaluation of distance learning courses and the benefits that this practice brought to improving the quality of these courses.

After discussing the institutional evaluation process, conducted by the CPA, Manager D admitted that there are some issues to be improved for effective implementation in distance learning courses. Among them, he highlighted the absence of items in the evaluation instrument relating to the technological infrastructure dedicated to distance learning.

Manager G stated that evaluation is a necessary process for the qualification of the course and mentioned that the UAB system does not offer subsidies for the application of its instrument.

Interviewees C and H, despite having commented on institutional assessments at other points in the interview, did not bring additional elements to the discussion. Coordinator C cited an evaluation carried out at the end of each subject, with results available only to the teacher involved, and Coordinator H denied carrying out evaluation processes.

The analysis of the most recent evaluations, available on institutional websites, made it possible to verify how each report was prepared and what criteria were considered in the evaluation process. To qualitatively characterize these documents, we have:

INST. 1 - It has a specific assessment for the distance learning modality, breaking down the data by course. Students, professors, and tutors participate in this evaluation process, and evaluate different aspects, including those related to course coordination and the infrastructure of the support centers;

INST. 2 - Institutional assessment is carried out by Campus, covering several courses of different academic degrees, levels, and modalities. Although the evaluation involves all individuals working in these units, there are no specific questions for Distance Education;

INST. 3 - The evaluation process is conducted by units, but, at the School of Education, the distance Pedagogy course is not represented, nor by its students, making a localized evaluation in the distance learning modality unfeasible;

INST. 4 - It has a specific assessment for the distance learning modality and breaks down the process by course. Students can evaluate a wide range of issues related to the course, including coordination, tutoring, and physical structures. The professors’ evaluation, however, does not seem to include the distance learning Pedagogy course;

INST. 5 - Despite carrying out a specific assessment for distance learning courses, addressing issues of infrastructure at the centers, integration of students with the university, and coordination activities, there is no division by courses. Only students and tutors participate in the process;

INST. 6 - The most recent report, available on the institutional website, indicates a specific evaluation of each distance course, however, there are only considerations about the performance of professors.

Only institutions that have specific student assessments for distance Pedagogy courses will be considered. At INST. 1, most of the questions evaluated, relating to tutors, the course, the center's infrastructure, students, and the HEI in general, received grades above 4 (between good and very good). Questions that could perhaps be considered to measure student satisfaction address the contribution of the course to their formation as citizens, to professional training, and the acquisition of theoretical and practical knowledge in the area. All these questions were well evaluated. The same report does not present specific questions about the student's commitment to the training they receive, although the participation of students in teaching, research, outreach projects, student movements, and university representation bodies may, to a certain extent, represent this engagement. These questions were evaluated as regular by the students; however, this fact may be related to the lack of incentive for these actions, as reported by the managers of this HEI.

The student assessment produced by INST. 4 also presents a good evaluation of most of the topics covered. Students at this institution report that they are satisfied and have a feeling of belonging to their course. There are no questions about academic commitment in this assessment.

As previously explained, the issues relating to the student addressed in this section are relevant to their continuation of the course. Some institutions do not have specific assessments for distance training, despite it being a very important tool for monitoring students and other components of the course.

Category referring to the scope external to the institution

In this section, we discuss aspects related to students' personal lives that may affect their permanence on the course, as well as the level of institutional action on such aspects. When questioning the managers, the interviewer suggested that they talk about topics such as the difficulties of adapting to the modality, reconciling studies with work and family issues, and financial difficulties.

Most interviewees pointed to personal issues as influencing students' retention. Manager D, for example, commented on the student's difficulties in organizing their time, considering the numerous responsibilities they carry beyond academic life. And he added: “So, the student ends up failing, it's not always because of a lack of knowledge, but because they didn't have time to study the topic, to read, I think that's the biggest impact we have on dropout rates is because due to the lack of time organization” (Manager D).

In the same sense, Manager F also addressed personal issues and reflected on the student profile that hinders his academic career:

This profile of the student in distance learning is still difficult, as we still have a lot of issues in our society with face-to-face meetings, activities, and face-to-face schools, with very little use of technological resources, often limited by difficulties in accessing the internet and technologies, and I think this is something that makes it very difficult for students to stay. (Manager F).

When addressing the characteristics of students that make their training difficult, Manager E highlighted, in addition to their academic profile, the fact that many students have great difficulties in mastering the digital tools used in the course. According to him, this is when face-to-face support centers are important and must coordinate, together with the Educational Technology Centers, actions to promote the digital inclusion of these students.

Manager A also commented that reconciling home, work, and study is a difficulty present in the lives of students. To this end, they try to encourage the organization of a weekly agenda of activities. The same coordinator adds that the students' main difficulties involve access to quality home internet and the infrastructure available at the centers to support students in their training. In Article 13 of Decree 9,057 (BRASIL, 2017), it is stated that the processes of institutional accreditation and re-accreditation, authorization, recognition, and renewal of recognition of distance learning courses will be subject to on-site evaluation only at the institution's headquarters, which may represent a step in the opposite direction to maintaining the quality of student support centers.

When addressing how personal issues influence the development of the course, Manager H explained that making deadlines more flexible is a strategy used to avoid student dropout: “There are individualized services, so students, center coordinators, and tutors get in contact with me and report the problem. And together we looked for an alternative to help this student” (Manager H). When asked if any student was unable to continue the course due to work and family issues, Manager C also cited the flexibility of deadlines: “But the issue of children, the issue of being head of the family, female head of the family, having to work. So, they sent it to me if I could increase the deadline for delivering that task. That's right. This happened” (Manager C).

Manager G, however, highlighted the technological fluency of some students as a determining factor for their retention. This issue was also raised by other interviewees who, in general, mentioned that the process of adapting to the modality, provided in the first semester, would be sufficient to guide students in conducting their learning.

Most managers deny the influence of financial issues on students' retention and, at the same time, recognize that their institutions do not have the means to support students in this regard. Manager B commented that throughout the period he has overseen coordinating Distance Learning and UAB at the institution, he has not received cases of dismissal for financial reasons but added: “And I see it as necessary in the coming years, [...] for example, scholarships, technological equipment, transportation assistance, food assistance, which are not provided for distance learning courses” (Manager B).

Coordinators D and G knew that student aid, available via the Federal Government, is only available to in-person students and that there are no specific resources from UAB to promote financial support policies for students. Manager H said that students of the modality can request financial aid from the university, but: “[...] I confess that, during the period in which I was coordinator, I never publicized this, because I wouldn’t be able to meet. But there’s nothing that stops it” (Manager H).

Regarding aspects determining student retention, the managers' responses presented some points in common such as the students' issues as the most relevant: family and work responsibilities were identified as the main factors interfering with the organization of time and dedication to the course. On the same topic, some studies in the reviewed literature bring similar considerations. Laham (2016), in her research on the possible causes of abandonment, highlights the influence of factors external to institutions, causes that the author calls exogenous. Araujo (2015), based on information from his sample of dropout students, states that the main reason that led to leaving the course was the lack of time to carry out the activities. Castro and Rodríguez (2016) point out that many students, despite being motivated and satisfied with the academic program when they begin their studies, have their stay in the course hampered by personal factors. Furthermore, the authors report that some students claim to have difficulties adapting to the modality, a fact commented on by managers E and G. The coordinators highlighted that, for some students, difficulties with using digital technologies remain during the course, even with the digital literacy subject in the first semester.

On the students' factors, interviewees C and H shared that making work delivery deadlines more flexible is a common movement in their courses, which demonstrates empathy with the student's situation, a strategy also highlighted in the investigation by Treviño, Ávila, and Loreley (2015).

Financial issues were not mentioned by managers as factors that affect student retention, and according to them, there were no cases of students who ended up dropping out because of this. According to the coordinators, the cost of maintaining students on the course is very low due to the exemption from monthly fees. Despite this, there was a need for some contributions such as assistance with transportation and food or a scholarship to remain in the degree program.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

This investigation was conceived through the chaining of several elements linked to distance Higher Education in Brazil. The objective was to identify and analyze how Higher Education Institutions, linked to the Universidade Aberta do Brasil, promote student retention in distance Pedagogy courses. To this end, semi-structured interviews were carried out with eight managers, including five course coordinators, one distance learning coordinator, one UAB coordinator at the institution, and one manager who accumulates these last two functions; and analysis of 18 institutional documents, including Institutional Development Plans, Pedagogical Projects of the Course, and institutional evaluation reports.

The exploration of this set of information provided indications of actions for student retention that exist in each context, represented by welcoming practices for new entrants, monitoring of academic trajectories, engagement activities provided, and mechanisms for monitoring dropout rates, among others, and encouraging the reflection on opportunities not yet implemented in institutions. It is noteworthy that each HEI, based on the analysis of their operating conditions, showed different levels of commitment to the institutionalization of Distance Education, being aligned with the considerations gathered in the reviewed literature. The plurality of contexts revealed by the investigation reflects the UAB system itself, which, as a public policy, encompasses the provision of distance learning courses in different institutions.

The context analysis of the HEIs, represented by the statements of managers and institutional documents, intertwined with the reviewed literature, promoted a set of insights, recorded here in the form of guidelines, to support the courses in promoting the retention of their students. The proposition of these guidelines is based on the plurality of elements that constitute this investigation and was based on the identification of weaknesses and good practices that aim to contribute to the qualification of actions to promote retention in Higher Education, especially in the distance modality and in courses Pedagogy. The proposed guidelines were:

1.Qualify the information available to those interested in joining the course

All means of disseminating the course must contain broad and detailed information about the development of distance learning, covering issues such as mastery of specific skills in digital technologies and virtual learning environments; approximate number of hours per week dedicated to activities; possible obstacles to be faced by students such as the feeling of isolation and difficulty in reconciling training and personal activities; and skills required of students related to flexible study and expected degree of autonomy. Topics relating to the specificities of the course must also be detailed, such as the number of face-to-face meetings planned, the proposed training path, and how these factors add value to the student's training, among others. For all questions, it is important to inform about the support structures of the course and the university to overcome any difficulties encountered. The objective of this guideline is to promote freshmen's access to information regarding what they are about to face, mitigating negative impacts generated by a lack of knowledge of the structure and demands of the course throughout their training.

2.Structure protocols for receiving and welcoming newcomers

Reception and welcoming activities need to be ensured for new students. Such actions must be planned with the aim of bringing the student closer to the training principles of the course and the operating processes of the university and the Distance Education system. It is necessary to prioritize two points: what the student needs to know about the institution/course and what the institution/course needs to know about the student to help the student with the identified needs and strengthen the bond at the beginning of the course. The importance of presenting, within the learning environments, communication channels with the different actors of the course is highlighted, enabling their integration. Furthermore, students must learn in detail about all student assistance programs that are available, knowing who they can talk to in cases of need.

3. Create a plan to monitor students’ academic trajectory

Student monitoring involves a series of variables such as performance in assessments, frequency of in-person meetings, access to virtual environments, and quantity and quality of contributions in discussion forums, among others. Whatever the criteria chosen by the coordination, tutors need to be considered protagonists in implementing this monitoring due to their proximity to the students. These professionals have very relevant responsibilities when it comes to keeping students on the course. In this way, it is recommended to build a plan to map the difficulties observed, so that, based on this, support actions can be developed that are viable within the institutional structure. The development of this plan must be the result of a joint effort involving tutors, professors, and coordinators and must be constantly updated to cover new issues identified through close monitoring with students.

4. Promote actions aimed at the social and academic integration of students

The promotion of social and academic integration actions for students is a basic element in their personal and professional training. Activities with this purpose need to be encouraged frequently, in virtual environments, at the centers, at the institution's headquarters, or even outside it. Giving students the opportunity to participate in academic and cultural events and the possibility of being scholarship holders in teaching, research, and outreach projects brings them closer not only to the course/institution but to their context of work as future pedagogues. Participation in student representations, whether in academic directories or course and university management, is also a factor of belonging and engagement. When reflecting on these integration actions, questions arise such as encouraging the use of methodologies that highlight the importance of group work; promoting monitoring and study groups at centers and virtual environments; and holding events that provide the exchange of experiences between students (academic weeks, lectures, training courses, artistic and cultural events).

5. Establish mechanisms to monitor course dropout rates

Monitoring dropout rates is essential for all educational systems, regardless of the modality, as it can provide evidence about the quality of practices carried out on the course, as well as indicate what is needed to improve them. It is necessary to institutionalize mechanisms that are responsible for monitoring the status of students throughout their education, to identify not only how many students drop out and in which semesters but also the possible causes of their abandonment. With this, the objective is to generate data that support the construction of practices that promote student retention.

6. Provide student support in response to the needs expressed by students

Distance learning students also have needs that require the attention of student support centers. In addition to identifying what type of assistance they need, the coordinators must seek to assist them as a way of promoting students' retention of the course. Pay attention to some support programs that are promoted in person and that could be extended to distance learning students: scholarships to stay in the degree; financial aid for low-income students; scholarships in institutional projects (teaching, research, and outreach); transportation assistance for travel to the poles; assistance with participation in academic events, psychological and pedagogical support; and assistance with the acquisition of technological and digital accessibility tools.

7. Promote institutional evaluations that consider the specificities of distance learning courses

Institutional assessments are indispensable instruments for measuring the quality of multiple factors in the academic context, in addition to being a source of information about students' connection with their education. Distance learning courses have specificities that need to be considered in these processes, requiring their evaluation instruments. It is recommended that the evaluation be carried out on a mandatory and semi-annual basis and should cover a set of issues relating to the course, students, professors, tutors, coordination, pole infrastructure, and institutional support structures, among others. Furthermore, the analysis and presentation of results are as important as the evaluation to qualify the practices carried out in the course, constituting a pedagogical process of evaluation and continuous improvement of educational processes.

These points consider the reality of 6 different Higher Education Institutions and, therefore, the global nature of these guidelines does not include the specificities of each course investigated. Furthermore, the content of these lines has a propositional character which, if applied in the contexts researched in future developments, would allow progress in the investigation of their effects. With all these clarifications, the application of these guidelines (or part of them) is encouraged in courses of the same nature as the scope of this investigation, as they are the product of theoretically based and scientifically committed research.

Student dropout and retention in Distance Education are broad themes that are still little explored in an emerging context like Brazil. Therefore, we expect that one of the contributions of this research will be to instigate new investigations in the area. Such research could expand the set of courses and institutions analyzed to obtain an even more accurate understanding of the phenomena discussed here concerning the country's educational institutions.

REFERENCES

ABED. Censo EAD.BR: Relatório analítico da aprendizagem a distância no Brasil, 2018. Curitiba: InterSaberes, 2019. [ Links ]

ALVES, Zélia Maria Mendes Biasoli; SILVA, Maria Helena G. F. Dias da. Análise qualitativa de dados de entrevista: uma proposta. Revista Paidéia, Ribeirão Preto, n. 2, p. 61-69, fev./jul., 1992. <https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-863X1992000200007>. [ Links ]

ARAUJO, Jaíne Gonçalves. Evasão na EaD: um survey com estudantes do curso de licenciatura em música a distância da UnB. Dissertação (Mestrado em Música). Brasília: Universidade de Brasília, 2015. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://repositorio.unb.br/bitstream/10482/19283/1/2015_Ja%c3%adneGon%c3%a7alvesAraujo.pdf >. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, Tais. A permanência em um curso de pedagogia a distância: um estudo piagetiano sobre o interesse das alunas. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Porto Alegre: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, 2018. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://lume.ufrgs.br/handle/10183/178779 >. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 7.234, de 19 de julho de 2010. Dispõe sobre o Programa Nacional de Assistência Estudantil - PNAES. Brasília, 2010. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2010/decreto/d7234.htm#:~:text=Decreto%20n%C2%BA%207234&text=DECRETO%20N%C2%BA%207.234%2C%20DE%2019,que%20lhe%20confere%20o%20art >. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 9.057, de 25 de maio de 2017. Regulamenta o Art. 80 da Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília, 2017. Disponível em: <Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/decreto/d9057.htm >. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (Inep). Censo da Educação Superior 2021: notas estatísticas. Brasília, DF: Inep, 2022a. [ Links ]