Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Educação em Questão

versión impresa ISSN 0102-7735versión On-line ISSN 1981-1802

Rev. Educ. Questão vol.57 no.53 Natal jul./sept 2019 Epub 19-Sep-2019

https://doi.org/10.21680/1981-1802.2019v57n53id17118

Article

The teaching of graphic conventions in literacy

4Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (Brasil)

5Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Espírito Santo (Brasil)

6Sistema Municipal de Educação (Brasil)

The article discusses prioritized approaches in the teaching of graphic conventions that govern writing, focusing on the knowledge that involves the understanding of writing orientation, the segmentation function of white spaces between words and punctuation. It is a documentary research that had as corpus 28 schoolbooks of children who attended the first year of elementary education during the years 2000 in a municipality of the state of Espírito Santo and 22 notebooks of teachers who acted in the schools of that municipality in the same period. We concluded that writing has been treated in a fragmented way and disconnected from its context of production and the aspects that characterize it graphically worked disregarding that these conventions were produced in the course of the development of the history of writing. The activities show that the characteristics of the written language are not recognized as historical and cultural productions elaborated in social interactions and, therefore, full of significations.

Palavras-chave: Literacy; Written language; Graphic conventions; Teaching and learning

O artigo discute enfoques priorizados no ensino das convenções gráficas que regem a escrita, atendo-se aos conhecimentos que envolvem a compreensão da orientação da escrita, a função da segmentação dos espaços em branco entre as palavras e a pontuação. Trata-se de uma pesquisa documental que teve como corpus 28 cadernos escolares de crianças que cursaram o primeiro ano do ensino fundamental durante os anos 2000 em um município do estado do Espírito Santo e 22 cadernos de professores que atuaram nas escolas desse município no mesmo período. Concluímos que a escrita vem sendo tratada de forma fragmentada e desvinculada do seu contexto de produção e os aspectos que a caracterizam graficamente trabalhados desconsiderando que essas convenções foram produzidas no decorrer do desenvolvimento da história da escrita. As atividades mostram que as características da língua escrita não vêm sendo reconhecidas como produções históricas e culturais elaboradas nas interações sociais e, portanto, carregadas de significações.

Palavras-chave: Alfabetização; Linguagem escrita; Convenções gráficas; Ensino e aprendizagem

El artículo discute enfoques priorizados en la enseñanza de las convenciones gráficas que rigen la escritura, atendiendo a los conocimientos que envuelven la comprensión de la orientación de la escritura, la función de la segmentación de los espacios en blanco entre las palabras y la puntuación. Se trata de una investigación documental que tuvo como corpus 28 cuadernos escolares de niños que cursaron el primer año de la enseñanza fundamental durante los años 2000 en un municipio del estado de Espírito Santo y 22 cuadernos de profesores que actuaron en las escuelas de ese municipio en el mismo, período. Concluimos que la escritura viene siendo tratada de forma fragmentada y desvinculada de su contexto de producción y los aspectos que la caracterizan gráficamente trabajados desconsiderando que esas convenciones fueron producidas en el transcurso del desarrollo de la historia de la escritura. Las actividades muestran que las características de la lengua escrita no vienen siendo reconocidas como producciones históricas y culturales elaboradas en las interacciones sociales y, por lo tanto, cargadas de significaciones.

Palabras clave: Alfabetización; Lengua escrita; Convenciones gráficas; Enseñanza y aprendizaje

Initial considerations

Studies developed by Cook-Gumperz (1991), Braggio (1992), Graff (1995), Macedo (2000), Mortatti (2000), Gadotti (2005), Gontijo (2003, 2005, 2008) and Pérez (2008) show that literacy has been configured as a sociocultural process of multiple and complex nature and points to a variety of conceptions and practices about the teaching of reading and writing that have historically been part of different educational projects in Brazil.

These concepts and their appropriations translate conceptions of language and person that interfere in the forms of the organization of reading and writing teaching in schools, since, according to Cagliari (1998, p. 41), depending on how a person interprets what is language and its functioning, he organizes the teaching work in literacy. According to the author, "[...] we can see clearly in practice in the classroom, in the methods that the school uses, what is the underlying language conception [...]" to them.

In this sense, Saviani (2008, p. 51) argues that every educational act carries with it a certain political perspective. Thus, the practice of the teacher always has a political meaning in itself, regardless of whether we are aware of it or not, since the attitude in the classroom "[...] does not explain by itself, but gains this or that sense, produces this or that social effect, depending on the social forces that act on it and with which it binds". Geraldi (2006) aligns with this position and states that

[...] any teaching methodology articulates a political option - which involves a theory of understanding [...] the contents taught, the focus given to them, strategies for working with students, bibliography used, the evaluation system, the relationship with the students, everything will correspond, in our concrete classroom activities, to the path we opt (GERALDI, 2006, p. 40).

The reflections of Cagliari (1998), Saviani (2008) and Geraldi (2006) allow us to understand that any theoretical and methodological proposal is the articulation of a conception of the world and education and, therefore, a conception of political action and an epistemological conception of the object of reflection. It is in this sense that we can affirm that pedagogical practice is not neutral. It reflects social, political, economic and cultural interests of the classes that form society and can contribute to the maintenance or overcoming of pedagogical practices that "[...] naturalize the development of reading and writing in children" (GONTIJO, 2002, p. 3).

According to Bakhtin (2008, p. 209), "[...] language only lives in the dialogical communication of those who use it." That is, language, in its concrete and living integrity, do not present as finished, systematized, since, constituting daily discourse, it resists this rigidity. When we interact with individuals, we produce units of meaning that are always contextualized, circumscribed to specific situations and full of intentionality.

Thus, in the movement of social interactions and moments of interlocutions, language is created, transformed and constituted as human knowledge from its own achievements and from continuous use in different situations. This dynamic process of language use enables children, as users of language, even before entering school, to develop ideas and use information from different sources and in different social situations, understanding the purpose of the language, according to specific requirements and situations of use.

In this direction, written language is seen as a way of expanding the possibilities of interaction and interlocution between persons. In other words, it can be understood as a way of dialogical interaction, which originates in interlocution and is organized to function in interlocution. Thus, it is important to consider literacy as a discursive system, structured in use and for use, through which persons produce meanings for their statements.

In this condition, it is important that the writing process of teaching and learning is based on principles that value the use of language in different social situations, with its diversity of functions and variety of styles and that promote a proposal of teaching the language that is organize around the use and appreciation of students' reflection on the different possibilities of language use. This implies, of course, knowledge of the complexity involved in working with written language as well as a process of coding and decoding graphic signals, concerned with offering to the students concepts and ready rules. In this context, literacy is understood as

[...] a social practice in which the formation of critical awareness, the production of oral and written texts, reading and understanding of the relations between sounds and letters are developed (GONTIJO, 2006, p. 8)1.

In this conception of literacy, language is considered as a sociocultural activity, developed in the verbal interaction between persons and, as such, obeys to conventions of use based on socially established norms that should serve as a basis for individuals to understand each other. With this perspective, the literacy process, one of the conditions for learning written language, involves the appropriation of knowledge about the writing system, which encompasses characteristics of the writing system,

[...] the history of alphabets, the distinction between drawing and writing, our alphabet, the letters of our alphabet (graphic categorization of letters, functional categorization of letters, direction of writing movements when writing letters), organization of the written page in the various textual genres, the symbols used in writing, the blank spaces in writing, the relations between letters and sounds and between sounds and letters (GONTIJO; SCHWARTZ, 2009, p. 16, our emphasis).

Therefore, it is considered that such knowledge integrates the discursive linguistic system and that it demand to be taught in a contextualized way and integrated to the reading and writing dimensions of texts, in order to promote the reflection on the language and the relations of these forms with the context in which they are used, enabling the learner to understand their use in daily life, increasing the possibilities of acting critically in society. It is opportune to point out that language, as a system, evidently has a rich arsenal of linguistic, lexical, morphological and syntactic resources. However, these resources are neutral, if they are not defined by the conditions of discursive production that contribute to the manifestation of meaning.

Based on these settings, in this article, we seek to reflect on the prioritized approaches in the teaching of graphic conventions that conduct the writing, attending to the knowledge that involves the understanding of the orientation of writing, the function of the white space segmentation between the words and punctuation. For this, the text is based on activities recorded in schoolbooks of children in the first year of literacy as of their teachers in one of the municipalities of Espírito Santo in the year 2000.

In addition to these initial considerations, this article presents, initially, reflections on theoretical perspectives that discuss the teaching of writing in literacy. Then, it outlines the methodological contributions that guided the study and analyzes the activities contained in schoolbooks, which reveal how teachers have been dealing, in the classroom, with the teaching of these graphic conventions that conduct writing. Finally, it presents the final considerations.

Perspectives on writing teaching

The appropriation of written language by children was studied by Ferreiro and Teberosky (1985). The authors, based on Piaget's psychogenetic studies on child development, conceived writing as a system of representation and considered that children, in the learning process, are related to this system as a conceptual object. In this sense, they understood that writing was placed for the learning process as an object of knowledge. For the authors, the children elaborate hypotheses about the functioning of writing and consider that, in order to the students understand how it works and how the written language is structured, the school must allow students to construct the concepts of reading and writing. After that, they believe that children become autonomous to make use of language in life.

According to Ferreiro and Teberosky (1985), in the process of appropriation of written language, the child, when formulating hypotheses about what writing represents and how we write, begins to understand the principle of the alphabetical basis of the system. From this point on, other learning is necessary as the rules of orthographic registry of words, that are, essentially, arbitrary; fluency in the reading process and the proper structuring of what you write, both at the level of the sentence and in the text. The authors' theorizations seek to show that the child needs to develop reading and writing skills, resulting from an understanding of the functioning of written language.

The Ferreiro and Teberosky's (1985) researches on writing psychogenesis has cast doubt on the notion of readiness and the belief that there are prerequisites for literacy, shifting emphasis from aspects related to motor coordination skills and acuity for the aspects related to the construction of the representation mechanism. From the perspective of the authors, the learning of reading and writing in literacy presupposes that the child has understood that writing is a way of representing through the alphabetic system. The studies of the researchers led to the valorization of the idea of "constructive error" in the learning process of writing and gave centrality in this process to the person himself/herself and not only to the content addressed. The conception of person from which the authors depart is what underlies the Piagetian theory. The child is seen as a cognitive person, who seeks to understand the world actively, that is, acting on it and on the objects of knowledge.

The trajectory that children go through learning to read and write has also been an object of interest of Vygotsky (1989) and Luria (1988), who, well before Ferreiro and Teberosky, investigated the prehistory of written language and showed, from the researches, that children's learning of writing begins with the appearance of the gesture, which contains future writing. Luria (1988), from his experiments, found that the development of writing in the child occurs through transforming of an undifferentiated scribble into a differentiated sign. This process, for Luria (1988), begins even before the child enters school and is taught how to take the pencil. Literacy, according to the author, involves the appropriation of mechanisms of symbolic writing and use of symbolic means to enable recall.

Following this same assumption, Vygotsky (1989, p. 121) considers that "[...] gesture is writing in the air [...]". Thus, through gestures (finger pointing, role-plays, mimetics, scribbles and games - in the sense of children's games invented when the children are alone or together with other children), the children attribute the sign function to the object and give it meaning. For the author, the symbolic representation in the game is a particular form of language at an early stage, leading to written language. Therefore, in the literacy process, children need to learn not only the use and functions of the written code, but the diversity of aspects that characterize written language. The works of Vygotsky (1989) and Luria (1988) highlighted that, in addition to gestures, scribbles and games are means used by children to attribute meaning to objects and to the world. So, learning to write involves learning to produce meanings.

For Gontijo and Schwartz (2009), writing is a form of language, because it allows the appropriation of new forms of expression and communication. In this way, their learning constitutes a fundamental tool to assure to the children their cultural and social insertion, since in with

[...] appropriating writing, individuals affirm themselves as persons, transform and potentiate natural abilities, as well as reflect on the language they use in daily life and increase the possibilities of relating to others (GONTIJO; SCHWARTZ, 2009, p. 19).

However, the basic condition for the written use of language involves, on the part of the students, the appropriation of very specific knowledge that, in turn, constitute one of the guiding axes of the work of teaching and learning that demands to be conducted in a conscious and intentional way by the literacy teacher. Gontijo and Schwartz (2009) emphasize that initiating literacy by working the knowledge on the writing system is to give children the conditions to understand the symbolic relationship that constitutes written production, that's because they need to understand that this symbolic system includes rules linked to the relations of linguistic forms among themselves and the relations of these forms to the context in which they are used in reading and writing practices. That is, in the literacy process, understanding writing to make use of it involves appropriating its characteristic aspects.

The mentioned studies show that the learning of writing, in literacy, encompasses several knowledges that, in turn, constitute contents of the work of teaching and learning that take place in classrooms. The graphic conventions of written language are one of the fundamental knowledges of working with children in literacy. Cagliari (1998) draws attention to the fact that children in the initial learning of written language experience conflicts between pauses in speech and writing, since there is no fixed correspondence between pauses in speech and the signs that represent them in written texts, as the comma and the dots. The author also points out that the "segmentation of words in writing, indicated by white space, corresponds even less to pauses or segmentations in speech" (CAGLIARI, 1998, p. 127).

Therefore, it is not simple for the child in literacy to understand that we do not write as we speak and there is, in addition to an orthographic normalization for written language, graphic conventions such as writing from left to right and from top to bottom. The learning of writing by children requires a systematic process of teaching orthographic conventions, but also of graphic conventions such as the placement of blank spaces in alphabetic writing, the direction of writing when writing texts.

It is worth mentioning that the criteria for the placement of white space are based on the understanding of morphological classes, which are not yet understood by children at the beginning of literacy. Thus, it is common for children to perform, during literacy, separations beyond those predicted by conventional orthography, which the literature of the area calls hypersegmentations.

Silva (1994) warns that children use criteria for the placement of white space, based, in most cases, on idiosyncratic and particular segmentation strategies. According to the author, in the process of constructing the writing segmentation, the child incorporates segmentation solutions observed in the writing itself and also proposes personal solutions for each case, based on the experience with the writing which is exposed in the school context. There are moments when the child segment according to the spelling conventions.

These reflections, regardless of their theoretical perspectives, point out that aspects related to graphic conventions are also placed as specific knowledge to be worked in literacy, taking into account written language in its linguistic and discursive dimension.

Methodological contributions of the research

We carried out a documentary research that had as corpus 28 schoolbooks of children who attended literacy classes during the years 2000 in a municipality of the State of Espírito Santo and 22 of teachers who worked in the schools in that municipality in the same period. The proposal was to seek to understand what is prioritized in the teaching of graphic conventions that conduct writing in literacy, paying attention to the knowledge that involves the understanding of the orientation of writing, the function of segmentation of white spaces between words and punctuation.

Thus, we assume in the research the qualitative approach that, in the field of educational research, starts from the assumption that the human sciences have its starting point in the text, since the human sciences

[...] are the sciences of man in its specificity, and not of a dumb thing or a natural phenomenon. Man, in his human specificity, always expresses himself (speech), that is, he creates text (albeit potential). Where man is studied outside the text and independently of this, it is no longer a question of the human sciences [...] (BAKHTIN, 2003, p. 312).

The schoolbooks were taken as a support of speeches about the teaching of graphic conventions that conduct writing. According to Marcuschi (2008), although all texts materialize in some support, the definition of what is a textual support still raises discussions in the theoretical field, but the author warns that the support of a text is "[...] a physical surface in a specific format that supports, fixes and shows a text [...]" (MARCUSCHI, 2008, p. 8). Thus, each documentary source that integrates the corpus was taken as support of discourses produced by persons located and dated, socially and historically.

The 50 schoolbooks that compose our corpus were taken as documents that testify reading and writing practices carried out at school. Studies carried out by Hérbrard (2001), Chartier (2007), Vinão (2008) and Mignot (2008) demonstrate that, throughout the history of educational institutions, forms of schooling have created ways of documenting students' school practices. Among them, we can affirm that the schoolbooks were constituted in support for excellence of the teaching of reading and writing in the school. Thus, the schoolbooks were understood as a testimony of school cultures, curricula, knowledge of the history of countries, values and ideas that circulated in certain times and contexts.

According to Hébrard (2001), before the first third of the nineteenth century, teaching of reading preceded teaching of writing and one of the main pedagogical innovations of this century was the non-temporal separation between teaching of reading and writing, which meant an important fact in the evolution of school literacy. According to Hébrard (2001), the school, then, changes its form of literacy. With this, the schoolbook is intended to carry out the activities proposed by the teacher for the teaching of the mother tongue, at the same time be accountable for parents and/or those responsible for student learning and creates visibility to the teacher's intellectual work. This author further states that the schoolbook, both because of its insertion in the history of the school and because of its concern for its conservation, is "[...] certainly a precious witness of what may have been and still is school work" (HÉBRARD, 2001, p. 121).

Revealing a growing interest in everyday or ordinary writing, Vinão (2008) argues that education researchers found, in schoolbooks, undoubted advantages of reaching educational institutions to know and study this "black box" of the school practices' reality. The progressive introduction of schoolbooks in the school space, replacing white sheets, as an adequate graphic space for recording the activities/works to be developed, has been affirming since the mid-nineteenth century. Therefore,

[...] these are the most appropriate source, if any, for the study of teaching, learning and the school uses of written language, that is, school literacy and the dissemination, in this context, of written culture (VINÃO, 2008, p. 17).

According to the author, there are still two other advantages in analyzing schoolbooks. The first is that their records allow us to glimpse different ideologies and school values, making it possible to study school practices very closely. The other is that the regularity of these records, due to a prolonged time, also allows to verify "[...] the lag or distance existing among the theoretical proposals, the legality and the practices of teachers and students" (VINÃO, 2008, p. 17).

Thus, through organized writing in the schoolbooks, both an inner and an outer reality, subjective and objective, represented and instituted are revealed. However the author points out that schoolbooks immortalize part of teaching and learning, we know that they will never portray what actually happened, because "[...] they are silent, they do not say anything about the oral or gestural interventions of the teacher and of the students" (VINÃO, 2008, p. 25).

In spite of these limitations, we considered in this study, based on Mignot (2008, p. 7), that the schoolbooks are bearers of "[...] collective and individual memories", dialoguing with the institutional context, constructing meanings. According to the author, knowing an educational institution schoolbook allows reflecting on learning processes, curriculum, memories, life stories, content records taught and evaluated, communication between parents and guardians, considering that the schoolbooks speak of the practice regarding school discourse and not only of pedagogical practice.

The access to the schoolbooks was given after sending an informative, distributed in all the schools with classes of literacy of the municipality of Viana, Espírito Santo. The informative paper outlined the objectives of the research and requested the collaboration of the schools' teaching staff to locate student and teacher schoolbooks. After that, we made visits to the schools for contact teachers and students and material collection. In the possession of the schoolbooks, we carried out the mapping of all registered activities that dealt with knowledge about the writing system worked in the 1st year of Elementary School. From the mapping of activities, it was possible to identify the axes of literacy that were most recurrent in the schoolbooks, which will be dealt with in the next section.

The teaching of graphic conventions revealed by schoolbooks

The documentary corpus of the research allowed identifying 8,927 activities recorded in schoolbooks, both teachers' and students', which revealed that knowledge about the writing system has been one of the most privileged axes in children's literacy, as shown in table 1.

Table 1 Literacy axes located in the schoolbooks

| F | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of the writing system | 5.257 | 58,89 |

| Reading | 2.615 | 29,29 |

| Text production | 1.055 | 11,82 |

| Total | 8.927 | 100 |

The percentage of 58.88% represents a quantitative of 5,257 occurrences of activities related to the knowledge on the writing system; followed by reading practices with 29.29%, which represent 2,615 exercises proposed and, with only 11.82% of frequency, appears text production activities, for a total of 1,055 exercises. Among the knowledge about the writing system, we can note the emphasis attributed to the knowledge of the alphabet, the relations between sounds and letters, the graphic and functional categorization of letters, the orientation and alignment of writing and punctuation marks. In this set, in turn, we notice a much smaller percentage of activities destined to the domain of graphic conventions, which reveals that aspects considered complex by the scholars of the area, as for the appropriation of writing, may be being disregarded in the literacy of children, as evidenced by the quantity shown in table 2.

Table 2 Knowledge about the writing system identified in the schoolbooks

| Knowledge of the writing system | F | % |

|---|---|---|

| To know the letters of our alphabet, including their graphic and functional categorization. | 3.726 | 69,43 |

| To dominate the relations between phonemes and graphemes | 1.452 | 28,72 |

| Mastering Graphic Conventions | 99 | 1,85 |

| Total | 5.277 | 100 |

The data indicates that the letters of the alphabet, including its graphic and functional categorization, have a greater incidence in literacy practices, making up 69.43% (out of 3,726 total occurrences) than the knowledge associated with the relationships between phonemes and graphemes with 28.72% (out of 1,452 occurrences) and, above all, the work developed with the graphic conventions, which totaled 1.85% (out of 99 occurrences).

It should be emphasized that, in the set of activities related to learning about the writing system of the Portuguese language, the graphic and functional categorization of letters, the conventional direction of writing and the comprehension of the white space segmentation between words and punctuation were worked simultaneously. We will deal, initially, with the conventional direction of writing.

The conventional direction of writing

In literacy, the teaching of conventional direction of writing is important, because students do not always understand that it is a convention that needs to be followed, since writing obeys certain principles of organization. The history of writing shows that, despite being a common mode among writing systems, not everyone uses writing from left to right and from top to bottom (CAGLIARI, 2007). Gontijo and Schwartz (2009) emphasize the relevance of children learn that the direction of writing follows patterns shared by users of a given system, enabling their understanding by all. The authors point out that, for those who already read and write,

[...] principles that conduct the direction of writing do not present difficulties, but for learners of reading and writing it is not so and, for this reason, they must be taught. Children need to understand that, conventionally, we write from left to right and from top to bottom (GONTIJO; SCHWARTZ, 2009, p. 37).

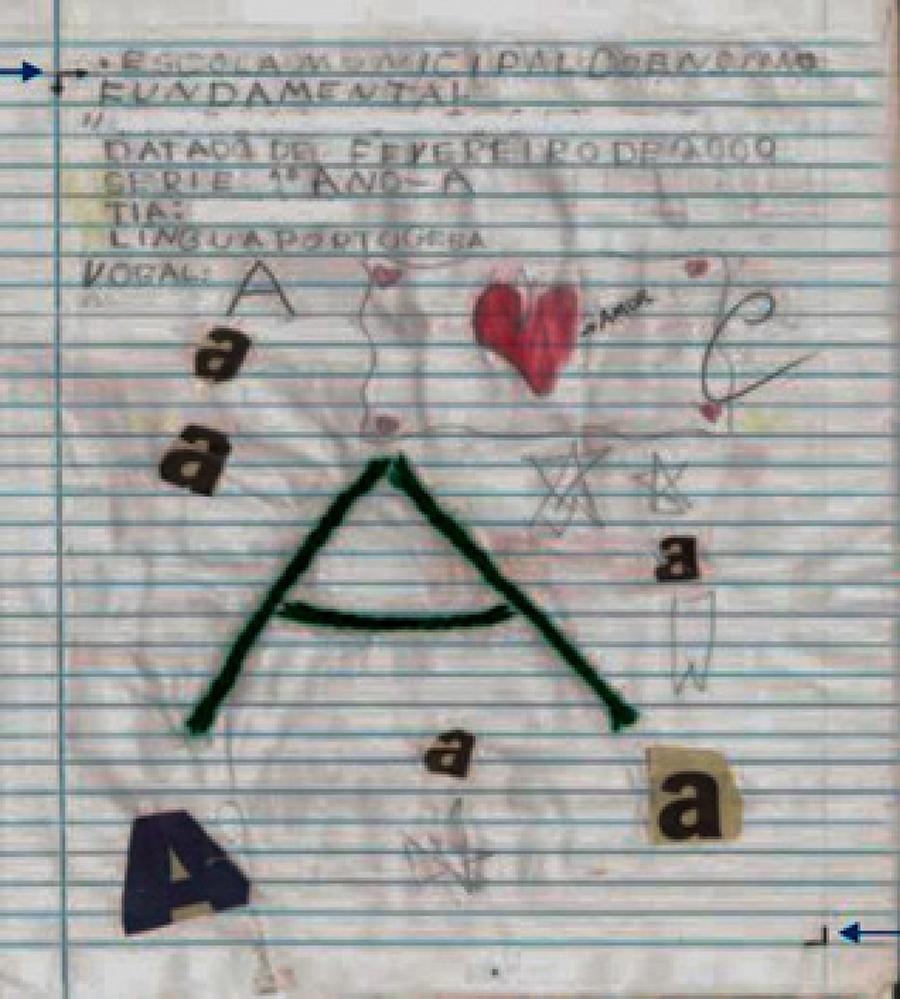

The schoolbooks show that graphic conventions such as the direction and the alignment of writing have been systematized in literacy classes through activities that focus on the teaching of other knowledge such as the graphic categorization of letters of the alphabet. Along with this type of activity, it is possible to infer that the direction and the conventional alignment of the writing have been worked by the teacher through the use of markings in the students' schoolbooks to indicate the conventions to be followed, as shown in picture 1.

Source: Schoolbook A1/2009 - downtown region (Viana/Espírito Santo).

Photography 1 Teaching activity of the direction and conventional alignment of writing

Although the activity is intended to teach the graphic categorization of the letter "A", it is possible to verify that, as a strategy of teaching of the direction of writing, some marks in the sheet of the schoolbook have served to guide the student the direction that he should follow to write the header (name of school, date, series and teacher's name). We verify this in the upper left margin, where two arrows appear: indicative of where the child should start writing and the direction that should follow from left to right, from top to bottom.

Still in the upper part of the sheet, a pencil a little dot is visible, indicating that this mark can be used for the demarcation of the beginning of the accomplishment of the school task. In the lower part of the schoolbook's sheet, on the right side, it is also possible to observe a marking that suggests a delimitation of the margin and the space to be respected in writing. We also notice in this schoolbook that the marking of the upper left margin with a little dot was used by the student for ten consecutive pages, most likely until the time she could follow the left margin with autonomy, without needing any type of marking.

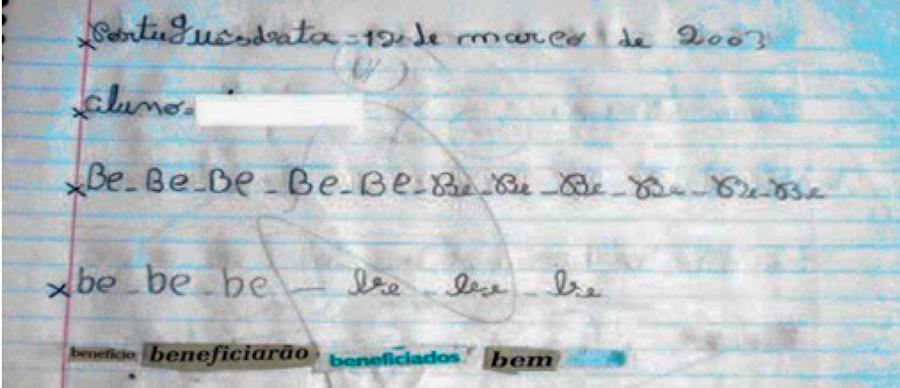

Marking with a dot, arrows and letter X seems to be common strategies used to work this knowledge, since they appear recorded in other schoolbooks with the same objective of guiding the directions to be observed in the use of written language, as shown in photography 2.

Source: Schoolbook A 22/2003 - downtown region (Viana/Espírito Santo).

Photography 2 Activity performed with margin demarcation

The letter X, in this case, is used as a mark to refer to the place where the child should start writing, as shown by the activity that aimed to teach the syllable "BE" and the different graphic categorizations (upper case, lower case, shape and cursive), using a sequenced copy of the syllable itself and words beginning with the syllable in question cut from newspapers and magazines. It should be noted that the letter X was used as a mark only on the left side of the schoolbook, pointing out that it was a form of demarcation of the margin and the spacing between lines that should be respected by the children when performing the writing activity.

The set of schoolbooks evidences that the teaching of the conventional direction of writing has prioritized the activities themselves, directed to the teaching of the writing system to work this knowledge with children, which, as indicated in the schoolbooks, is gradually being appropriated by the students. In this way, they also use their own markings to make margins, delimit space, divide the activities in the sheets of the schoolbook and organize their writings using the same demarcations used by the teachers. Thus, as pointed out by Vygotsky (1989), children in the initial phase of the appropriation of writing repeat gestures and actions of adults.

It is worth to point out that the set of activities registered in the schoolbooks and aimed at the use of teaching in the conventional direction of writing did not involve texts of different genres, which indicates that the teaching of this knowledge seems to be restricted to writing activities of daily headers and their own responses to these activities, thus, denoting that the teaching of this graphic convention prioritizes writing practices that are carried out in a school context.

This is corroborated by the fact that in the records of schoolbooks, both of teachers' and students', we do not notice activities that could lead children to explore characteristics of the conventional direction of writing in different printed materials, in order to provide an understanding of marks on the page of a printed form. For example, a sequence of letters expressing different meanings or different forms of text alignment on the page, depending on the textual genre and the medium in which it is served. Even so, in the written language of Portuguese language, the organization of writing obeys conventions of ordering and directing (from left to right and from top to bottom).

Segmentation of the white spaces

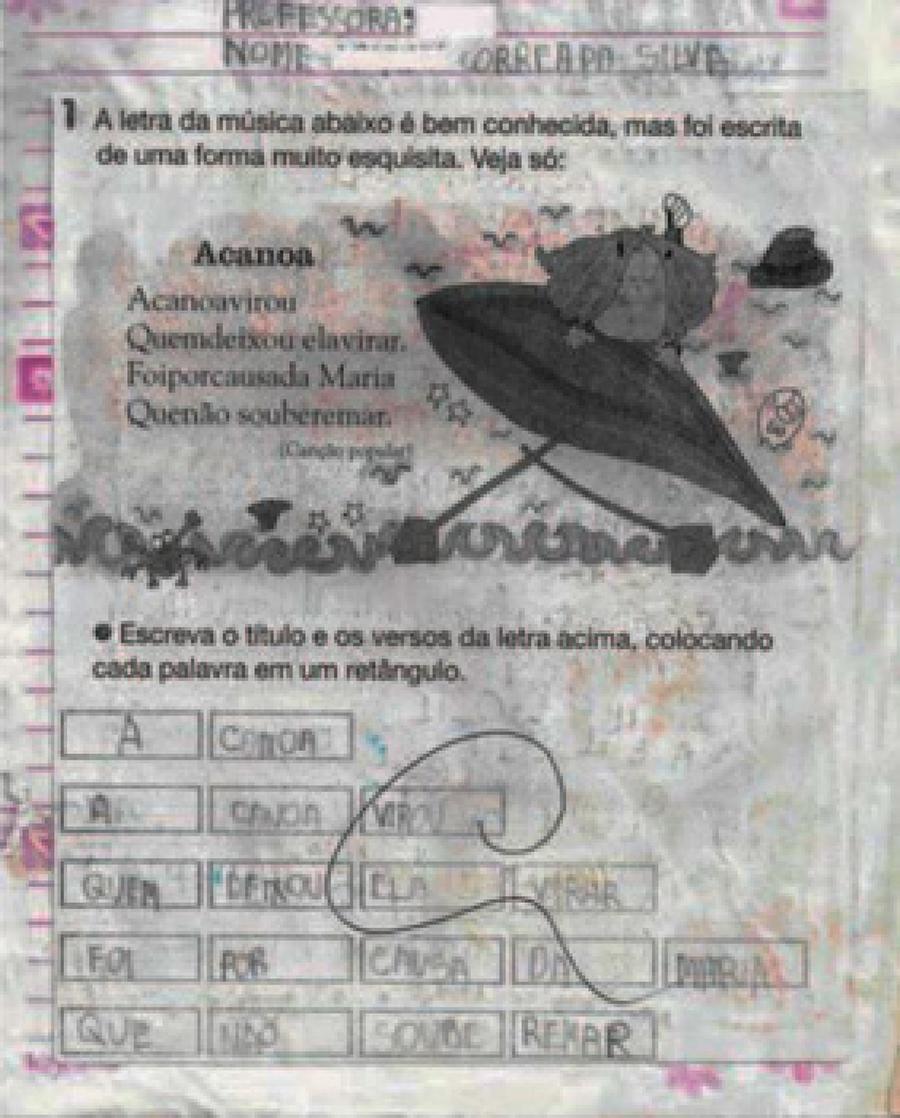

The white spaces between the words also represent a social convention that needs to be learned at the beginning of the literacy process. The work with this knowledge gives students the understanding that, "[...] in speech, there are not, as in writing, regular separations between words, except in situations marked by the intonation of the speaker" (GONTIJO; SCHWARTZ, 2009, p. 43). For the teaching of this knowledge, schoolbooks show the preponderance of activities involving fragments of texts such as adults' and children's songs and speeches, presented to the children without separating between words, so they write each word of the text within a rectangle.

Source: Schoolbook A 20/2004 - Vila Bethânia region (Viana/Espírito Santo).

Photography 3 Activity with first name

This type of activity is common in schoolbooks as a strategy used to teach children to segment speech units that will be represented in writing. This activity favors children's understanding that the organization of the writing system is related to the fact that the linearity of writing has different characteristics of speech linearity. Thus, we have noticed that the teaching of the segmentation of the speech to the writing has been accomplished through activities that lead the children to identify words that compose texts. In this case, the schoolbooks point out that there is a tendency, at the beginning of literacy, for words that form texts.

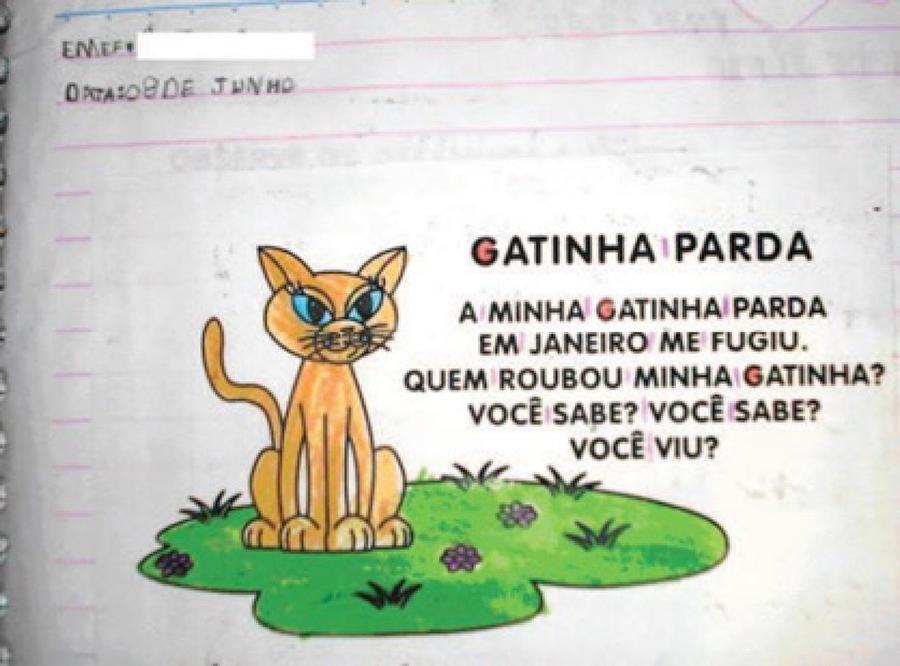

They are short texts known to children used to work on this knowledge. What differentiate has been the strategies used to guide children about the spaces to be respect between words and phrases in the texts, since sometimes they are required to paint each word with different color, sometimes they are asked to make a dash to indicate the white space between the words, as the activity presented in photography 4 exemplifies.

Source: Schoolbook A 4/2009 - Areinha region (Viana/Espírito Santo).

Photography 4 Work with white space segmentation

The schoolbooks point out that it has been usual in literacy to work on the segmentation of white spaces together with the study of letters of the alphabet, as photography 4 highlights, which shows that letter G was also object of teaching in the same text, since it was painted red in the word GATINHA (kitten, in Portuguese), indicating that the text was also used as a pretext for the study of the letter G at the beginning of words.

Thus, these types of activities, as pointed out Gontijo and Schwartz (2009), seem to be serving to work the recognition of letters of the alphabet which is another important knowledge to be appropriate in literacy. The activities work on the segmentation of speech and writing to show that both are produced in a linear sequence, since this linearity occurs differently in speech and writing.

Although the text of the activity contains punctuation marks, which also mark, in the writing, the sound pauses, it was possible to verify that these are not worked together with the white space between words, thus reducing the possibility of the children to expand the understanding that speech pauses do not always have fixed correspondence with writing pauses. According to Cagliari (1998), punctuation marks in written language are also resources used to indicate pauses in speech to give readability and meaning to what we produce orally.

Punctuation marks

In written language, punctuation marks constitute specific resources for rescuing subtleties and nuances typical of orality, since they carry prosodic information that interferes with the meanings of text produced during reading. Therefore, it is important for children to understand that these signs help in the construction of meaning in the text, that inappropriate use or lack of punctuation compromise their understanding and that can alter the content of the text read. For the written text, punctuation marks have semantic-syntactic-discursive importance. It is an aspect of the graphical convention of written language of paramount importance to be worked on in literacy.

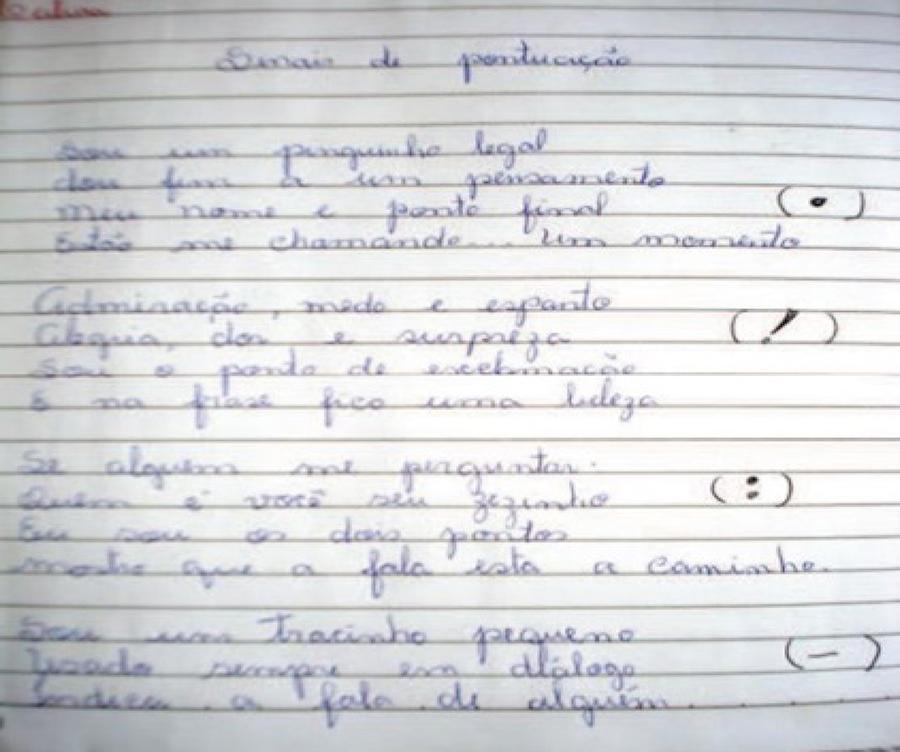

Fonte: Caderno P 10/2006 - região Marcílio de Noronha (Viana/Espírito Santo).

Photography 5 Reading on punctuation marks

The set of schoolbooks indicates that this knowledge has been worked intentionally in the literacy classes. However, the most recurrent teaching of punctuation marks activities in the schoolbooks still point to a mechanistic approach to teaching, since it is common for punctuation marks to be taught from the reading of a text that was produced for an explicit didactic purpose - the teaching of punctuation marks.

In this direction, a teaching strategy that is usual is to take a poetic text, in the form of verses, whose main purpose is to present children with the punctuation marks (end point, exclamation mark, colon, indent and the question mark) and the situations in which they are employed. That is, these signs of writing have been worked in an expositive way from the presentation of the rules for its use, through a text that serves as a pretext for teaching the rules. The teacher follows the presentation of the rules, then proposes an activity to be carried out by the children in which they are led to repeat the uses of the punctuation marks and to identify the graphic forms that represent them, as exemplified by the activity presented in photography 6.

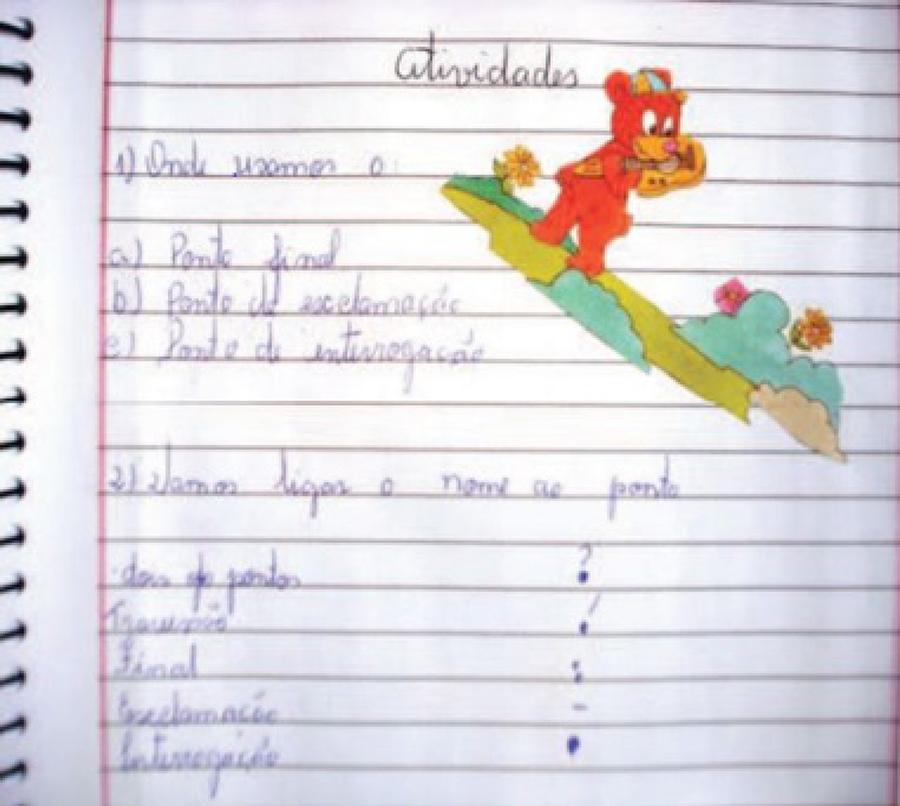

Source: Schoolbook P 10/2006 - Marcílio de Noronha region (Viana/Espírito Santo).

Photography 6 Memorization of punctuation marks activities

As shown, it is possible to verify a concern with the application of rules that try to direct and systematize the use of these marks in writing. However, Cagliari (2007) indicates that the use of punctuation marks is quite variable, and may change according to the production context, that is, a word like "one", for example, may be accompanied by the question mark, exclamation mark, ellipsis, among others, depending on the discursive communication of which it is part.

These types of recurring activities in schoolbooks show that punctuation marks have been addressed through approaches that make it difficult for learners to understand the functions of signals as resources for production of meaning. The knowledge about punctuation marks and their uses are formed, insofar as persons, speakers and interlocutors, make use of these linguistic resources in interlocution processes, in order to understand their importance for the text produced orally or in writing.

The approaches that are evidenced by the activities exemplified in photography 5 and 6 make it difficult for children to appropriate punctuation marks as resources of the written language that express meanings in oral language. Punctuation marks, when worked out in isolation from the context in which they can be used, result in "[...] formalism and exaggerated abstraction [...]" (BAKHTIN, 2003, p. 265), to avoid students to analyze their role in discursive practices. The author points out that we do not learn the language through abstract rules, as a description system, but in the concrete structure of enunciation.

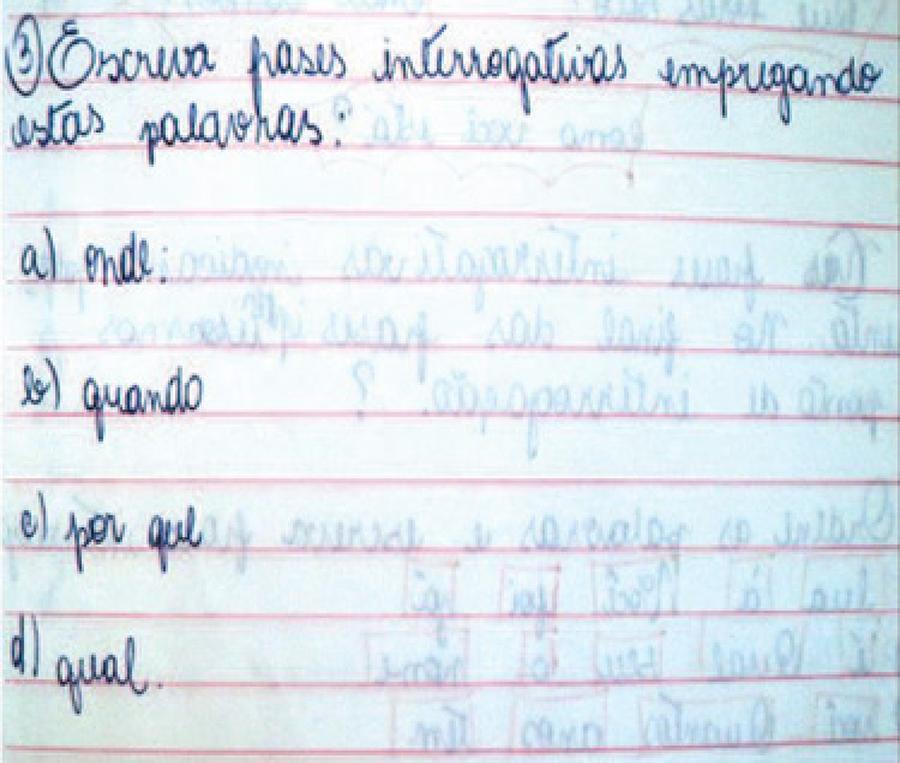

Another activity that was used as a characteristic of the teaching of punctuation marks was the request for the elaboration of sentences that require the use of a specific punctuation mark. Photography 7 exemplifies this type of activity that prioritizes the technique of mechanical use of punctuation at the expense of discursiveness.

Source: Schoolbook P 9/2007 - Marcílio de Noronha region (Viana/Espírito Santo).

Photography 7 Activity to work the question mark

The activity demands that children organize a priori their content of saying, creating an imaginary interlocutor without having specific need to ask a question, except to fulfill a school activity. We understand that the knowledge of the rules of punctuation signal use exerts a significant influence on the practice of teaching, whose use prescribes fixed rules associated to the syntax.

It is indisputable that grammar has a "[...] relevant sociocognitive function, since it is understood as a tool that allows a better communicative performance" (MARCUSCHI, 2008, p. 57). However, the use of punctuation marks in writing and, consequently, their perception is not limited to purely syntactic factors.

In the use and, by extension, in the perception of these signs, other grammatical factors act together, such as those of semantic, morphosyntactic, prosody and, above all, the discursive factor. Therefore, it is important that there is a diversity of activities that lead the students to reflect on the effects that punctuation signals operate on in the construction of text sense in both linguistic and discursive dimensions.

Final considerations

The activities recorded in the schoolbooks, both students' and teachers', make it possible to infer that the teaching of graphic conventions in children's literacy follows closer to theoretical perspectives of literacy that are based on the conception of language, that is related to formal aspects of the text. This indicates that the conception of literacy that seems to predominate in the years 2000 treats written language as an abstract system of normative and identical linguistic forms.

Thus, in the years 2000, predominate in literacy the idea that the graphic conventions of the writing system can be taught from activities that lead children to perceive it as signs to be recognized, from the exercise that lead them to recognize the conventions. Therefore, there is still in circulation in schools a misconception of writing treated as a closed-code system in which learning must prioritize mechanical activities of identification, recognition and repetition.

Thus, writing appears treated in a fragmented way and unrelated to its context of production and the aspects that characterize it graphically seen as devoid of meaning produced by men in the course of the history of writing development. The activities show that the characteristics of the written language, recognized as historical and cultural productions elaborated in social interactions and, therefore, full of meanings are still far from the literacy classes.

1The aforementioned concept was reorganized by the author in a meeting held in September 2013, during the formation process of the Pact for Literacy in the Right Age (Pmaic): "[...] a socio-cultural practice in which children, through work integrated with the production of oral and written texts, reading, knowledge of the Portuguese language system and the relations between sounds and letters and letters and sounds, exert criticality, creativity and inventiveness." However, the concept has not yet been published in articles or book to reference.

REFERENCES

BAKHTIN, Mikhail Mikhailovith. Estética da criação verbal. Rio de Janeiro: Martins Fontes, 2003. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, Mikhail Mikhailovith. Problemas da poética de Dostoievski. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2008. [ Links ]

BRAGGIO, Silvia Lúcia Bigonjal. Leitura e alfabetização: da concepção mecanicista à sociolinguística. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1992. [ Links ]

CAGLIARI, Luiz Carlos. Alfabetizando sem o bá-bé-bi-bó-bu. São Paulo: Scipione, 1998. [ Links ]

CAGLIARI, Luiz Carlos. Alfabetização & linguística. São Paulo: Editora Scipione, 2007. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Anne Marie. Exercícios escritos e cadernos de alunos: reflexões sobre práticas de longa duração. In: CHARTIER, Anne Marie (Org.). Práticas de leitura e escrita. História e atualidade. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica/CEALE, 2007. [ Links ]

COOK-GUMPERZ, Jenny (Org.). A construção social da Alfabetização. Tradução Dayse Batista. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas. 1991. [ Links ]

FERREIRO, Emília; TEBEROSKY, Ana. Psicogênese da língua escrita. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 1985. [ Links ]

GADOTTI, Moacir. Alfabetização e letramento: como negar nossa história. Porto Alegre: 2005. [ Links ]

GERALDI, João Wanderlei. O texto na sala de aula. São Paulo: Ática, 2006. [ Links ]

GONTIJO, Claudia Maria Mendes. O processo de alfabetização: novas contribuições. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2002. [ Links ]

GONTIJO, Claudia Maria Mendes. A criança e a linguagem escrita. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2003. [ Links ]

GONTIJO, Claudia Maria Mendes. Alfabetização e a questão do letramento. Cadernos de Pesquisa, Vitória, v. 11, n. 21, p. 42-72, jan./jun. 2005. [ Links ]

GONTIJO, Claudia Maria Mendes. Alfabetização na prática educativa escolar. Revista do Professor, Belo Horizonte, n. 14, p. 7-16, out. 2006. [ Links ]

GONTIJO, Claudia Maria Mendes. A escrita infantil. São Paulo: Cortez, 2008. [ Links ]

GONTIJO, Cláudia Maria Mendes; SCHWARTZ, Cleonara Maria. Alfabetização: teoria e prática. Curitiba: Sol, 2009. [ Links ]

GRAFF, Harvey. Os labirintos da alfabetização: reflexões sobre o passado e o presente da alfabetização. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1995. [ Links ]

HéBRARD, Jean. Por uma bibliografia material das escritas ordinárias: o espaço gráfico do caderno escolar (França - séculos XIX-XX). Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Campinas, n. 1, p. 115-141, jan./jun. 2001. [ Links ]

LURIA, Alexander Romanovich. O desenvolvimento da escrita na criança. In: VIGOTSKI, LEV SEMENOVICH; LURIA, Alexander Romanovich; LEONTIEV, Alex Nikolaevich. Linguagem, desenvolvimento eaprendizagem. São Paulo: Ícone Editora, 1988. [ Links ]

MACEDO, Donald. Alfabetização, linguagem e ideologia. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 21, n. 73, p. 84-99, dez. 2000. [ Links ]

MARCUSCHI, Luiz Antônio. Produção textual, análise de gêneros e compreensão. São Paulo: Parábola Editorial, 2008. [ Links ]

MIGNOT, Ana Chrystina Venâncio (Org.). Cadernos à vista: escola, memória e cultura escrita. Rio de Janeiro: Edurej, 2008. [ Links ]

MORTATTI, Maria do Rosário Longo. Os sentidos da alfabetização. São Paulo: Editora Unesp, 2000. [ Links ]

PÉREZ, Carmen Lúcia Vidal. Alfabetização: um conceito em movimento. In: GARCIA, Regina Leite; ZACURR, Edwiges (Org.). Alfabetização: reflexões sobre docentes e saberes discentes. São Paulo: Cortez, 2008. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, Dermeval. Pedagogia histórico-crítica: primeiras aproximações. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2008. [ Links ]

SILVA, Ademar. Alfabetização: a escrita espontânea. São Paulo: Contexto, 1994. [ Links ]

VINÃO, Antônio. Cadernos escolares como fonte histórica: aspectos metodológicos e historiográficos. In: MIGNOT, Ana Chrystina Venâncio (Org.). Cadernos à vista: escola, memória e cultura escrita. Rio de Janeiro: Edurej, 2008. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev Semionovich. A formação social da mente. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1989. [ Links ]

Received: March 18, 2019; Accepted: April 15, 2019

texto en

texto en