Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Educação em Questão

versão impressa ISSN 0102-7735versão On-line ISSN 1981-1802

Rev. Educ. Questão vol.59 no.59 Natal jan./mar 2021 Epub 18-Abr-2022

https://doi.org/10.21680/1981-1802.2021v59n59id24637

Artigo

Gender, woman, crime, and violence: relations and tensions

3Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (Brasil)

4Universidade Feevale (Brasil)

This article challenges the limits and possibilities of articulation, as well as how to “use” woman, gender, crime, and violence in the theoretical-methodological design of a research on gender relations in schools in regions with high incidence of reported crimes against women. Reports filed in a given Specialized Police Station for Attending to Women were mapped to select a series of schools, in order to highlight the need to identify and problematize how women, gender, crime, and violence are used as categories by determining if they were considered “endogenous” or “exogenous” regarding the theorizations encompassing this survey. This process also demanded the discussion of the term “gender violence”, based in this text on concepts of gender, violence, and power. Amid instances of approximation and distancing, it was possible to recognize the theoretical-methodological effects of such categories on the survey processes, as well as the ethical challenges of using tools that produce geographies regarded as “violent”.

Keywords: Violence; Gender; Gender based on violence; Kernel mapping

O artigo discute e tensiona limites e possibilidades de articulação e “uso” das categorias mulher, g ênero, crime e violência no desenho teórico-metodológico de uma pesquisa sobre as relações de ênero em escolas localizadas em regiões de alta incidência de denúncia de crimes contra mulheres. A seleção das escolas se apoiou num mapeamento das ocorrências registradas numa dada Delegacia Especializada de Atendimento à Mulher, processo que evidenciou a necessidade de identificar e problematizar a adoção das categorias mulher, gênero, crime e violência, colocando em relevo as consideradas “endógenas” e “exógenas” frente às teorizações nas quais a pesquisa se inscreve. Esse processo demandou ainda a discussão do termo “violência de gênero” balizado neste texto pelos conceitos de gênero, violência e poder. Entre aproximações e distanciamentos, foi possível reconhecer os efeitos teórico-metodológicos de tais categorias, bem como os desafios éticos da utilização de ferramentas que produzem geografias então nomeadas e reconhecidas como “violentas”.

Palavras-chave: Violência; Gênero; Violência de gênero; Mapas de Kernel

El artículo discute los límites y las posibilidades de articulación y "uso" de las categorías mujer, género, crimen y violencia en el diseño teórico-metodológico de una investigación sobre relaciones de género en escuelas ubicadas en regiones con alta incidencia de denuncias de crímenes contra la mujer. La selección de las escuelas se basó en un mapeo de las ocurrencias registradas en una determinada Comisaría Especializada en Atención a la Mujer, proceso que puso de manifiesto la necesidad de identificar y problematizar el uso de las categorías mujer, género, crimen y violencia, destacando las consideradas "endógenas" y "exógenas" a las teorizaciones en las que se inscribe la investigación. Este proceso también exigió la discusión del término "violencia de género", basado en este texto por los conceptos de género, violencia y poder. Entre aproximaciones y distanciamientos, fue posible reconocer los efectos teórico-metodológicos de tales categorías, así como desafíos éticos de utilizar herramientas que producen geografías luego nombradas y reconocidas como "violentas".

Palabras clave: Violencia; Género; La violencia de género; Mapeo de Kernel

Introduction

The article discusses and challenges both limits and possibilities of articulation and "uses" of the categories – woman, gender, violence and crime – in the theoretical and methodological design of a research on gender relations in schools located in regions with high incidence of reported crimes against women in a city of Rio Grande do Sul/Brazil.

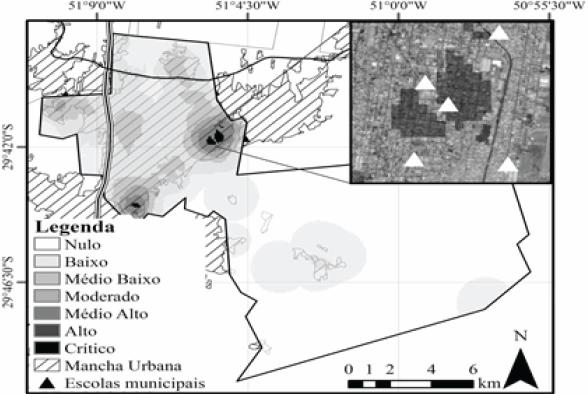

The selection of the schools was made based on a mapping (figure 1) produced with complaints registered at the Specialized Police Station for Attendance to Women (DEAM, in Portuguese abbreviation) from records circumscribed to what is defined as violence against women, the foundation on which the Maria da Penha Law (11.340, of August 7, 2006) and the Feminicide Law (13.104, of March 9, 2015) were produced. The category “violence against women”, however, poses some challenges of theoretical and methodological order, since the theoretical framework in which the research is inserted – post-structuralist gender studies that articulate with Foucauldian theorizations – strongly questions its universalizing and essentialist character.

Another aspect to be problematized involves the univocal relationship that is established between crime and violence (DEBERT; GREGORI, 2008), a point of attention for studies that articulate with legal instances. In summary, the production of a mapping that intends to particularize regions based on what the legislation proposes as denunciation of crimes of “domestic and family violence against women” put us in front of important issues to be discussed and tensioned, based on the conceptual framework that we assumed in the project.

In the scope of this problematization, we produced two arrangements denominated here as “endogenous” and “exogenous” categories referring to the theoretical-methodological axis to which the research project is circumscribed. Thus, endogenous are the categories based on the theoretical framework that allowed us to delimit, within the scope of the project to which this article is linked, the questions as well as the methodological and analytical course of the investigation. Exogenous are categories that are constituted from references that, although placed under suspicion and erasure in the scope of this theoretical referential, constitute themselves as those fundamental to some stages of the study – especially the production of the Kernel maps.

Our focus in this article, therefore, is the theoretical and methodologica discussion that localizes and tensions these two arrangements, since they make it possible to build bridges and give coherence to the field work and the analyses to be carried out in another stage through the investigation in the schools.

Women, family, home, and crime: theoretical tensions of the exogenous categories

The Maria da Penha Law and the Feminicide Law both emphasize and reify, in their formulation, the centrality of the category woman. Although the Maria da Penha Law, currently more peaceful , and the Feminicide Law, still quite controversially , have put on the agenda the inclusion of trans women as passive agents foreseen in the laws (MESSIAS; CARMO; ALMEIDA, 2020), these legislations name the woman as a legal figure of universalizing pretension, whose condition of unquestionable acceptability concerns a set of biologica markers in their bodies.

It is worth emphasizing that the legal figure of “woman”, a law individual, “victim of violence”, emerges as the result of a historical process in which feminist and women’s movements have denounced and put on the agenda the condition of abuse and murder of women, the result of gender power relations in our societies. With greater emphasis, from the 1980s on, the numbers that circumscribe violence against women have been registered and confrontation actions have been demanded by organized movements that denounced the impunity of the violation of women’s rights (SANTOS; IZUMINO, 2005). The “honor crimes” (legitimate defense of male honor) or “crimes of passion” and the “private/family” view, very common and socially accepted in that period, allowed the non-punishment of the abuses experienced (CAMPOS, 2015). The term violence against women, therefore, highlighted the female oppression by the condition of their sex, an understanding articulated with the assumptions of patriarchy, a reference aligned with international feminist discussions and global pacts to eradicate discrimination against women . Thus, in the early 1980s, the understanding of violence against women took shape in Brazil, reiterating the notion of the “victim/subordinate” woman (SANTOS; IZUMINO, 2005), whose experiences of abuse would be a constant, regardless of the historical moment and social contexts (DEBERT; GREGORI, 2008).

From the standpoint of policy organization, the term “violence against women”, by resorting to the universalizing and essentialist character of the category, was effective in making gender-based abuses visible. By producing an understanding of women as dominated and victims, it also served to sensitize State agencies, which, according to Santos and Izumino (2005), tended not to understand violence experienced by women as a crime, as well as to blame the victim for the aggression suffered. In sum, the notion of “violence against women” makes public and recognizable not only the abuses experienced, but also an understanding of violence in the prevailing relationships between men and women. In 2006, the terminology was ratified in the Maria da Penha Law , and the meanings produced and attributed to it are today even more strongly linked to two other categories: family and home . Thus, family, woman, and domicile, besides being the basis for the changes in the code of criminal procedure, typifying the crimes , organize the Specialized Police Stations for Attendance to Women and circumscribe the people and the types of denunciations that will be received in these institutions.

It is worth emphasizing, however, that the articulation between women, family, and home was not inaugurated by the Maria da Penha Law and seems to have been produced in a process that involves the political demands of organized social movements. From 1985 on, with the implementation of the first Police Station for the Defense of Women (DDM, in Portuguese abbreviation), the service to victims began to show some patterns of complaints that were repeated, generating an index of records that highlighted situations and actions of abuse experienced by women in the domestic environment and mostly practiced by their spouses or partners. In general, the phenomenon related to complaints in the Police Stations for the Defense of Women came to be considered as an effect of a dysfunctional family organization, whose ballasts seem to have contributed, according to Debert and Gregori (2008), to some understandings that produce a homogenizing effect of what is understood as domestic and family violence against women.

In the state of São Paulo, in 1996, there was an expansion the scope of the Police Stations for the Defense of Women to also investigate crimes against children and adolescents in order to include not only the protection of women but also the protection of the family. This broadening of the scope of the Police Stations for the Defense of Women contributed to the understanding of family violence as synonymous with violence against women, against the elderly, and against children and adolescents. This semantic shift also produced an understanding of violence against women as abuse perpetrated against the wife or partner, restricting the problem to the domestic and family sphere and thus reducing the emphasis on violence produced by gender asymmetries (DEBERT; GREGORI, 2008).

From the point of view of this research, the Maria da Penha Law, the crimes typified by it, as well as its agencies and mechanisms, will produce the indiviudals of the crime and the abuses likely to be reported. It seems reasonable, therefore, to understand that the studies that take the complaints in the Police Stations for the Defense of Women as part of the empirical material are affected by the agency of the processes through which women, family, and home come to constitute themselves as categories that mark and (de)limit what is understood as violence against women and gender violence.

Gender and violence: tools for the analysis of conflictive dynamics

The notion of “woman” as a universal individual who, to a greater or lesser extent, shares a set of characteristics, personality traits and experiences assumes that the materiality of the body produces effects on social phenomena. Sometimes understood as a determining cause of male and female behaviors, sometimes as the basis upon which society constructs meanings about being a man and a woman, the sexed body, in these cases, is conceived as a pre-discursive element for the social construction of gender (NICHOLSON, 2000).

Despite being strongly contested and located outside the theoretical framework of this study, “woman”, as a legal figure, passive agent foreseen in the law, constitutes the category that allowed the mapping and identification of the regions of high incidence of denunciation of crimes perpetrated against women. What circumscribes the category “woman” can be understood at the same time as a limit – because it fixes and essentializes – and as a possibility, since it allows, in the relations between women, family, crime and domicile to map and produce a set of questions centered on gender.

Adopted as the central concept of our study from the post-structuralist perspective, gender problematizes and opposes the essentialist and universalizing notions that are sustained, to a greater or lesser extent, in the biology of bodies to, then, constitute itself as a category that allows understanding mechanisms from which individuals are constituted as embodied and generified individuals (MEYER; SILVA, 2020). Gender would be, in this approach, “[...] a primary way of giving meaning to power relations [...]” (SCOTT, 1995, p. 86), here articulated to Michel Foucault’s analytics of power.

In these terms, power is taken as a productive force that cuts across and modulates the entire social fabric and, as such, is exercised in relation, as an “action that influences the action” of individuals and the collectivity with the purpose of managing life and behavior. In power relations, things, institutions, precepts and subjectivities are valued, knowledge is activated, sustained and delegitimized, individuals become “subjects” and ways of relating are produced (PASSOS, 2010).

As a power relation, gender inscribes itself on bodies (and produces them) through disciplinary and regulatory technologies that also constitute and cut across the processes of formulation and organization of doctrines, knowledge, institutions, and policies. Gender, therefore, can be understood as “[...] an organizer of the social and culture [...]” (MEYER, KLEIN, DAL'IGNA, ALVARENGA, 2014, p. 898), cause and ground of naturalized inequalities in bodies. In this direction, Scott (1995, p. 2) signals that “[...] gender is the knowledge that establishes meanings for bodily differences. We cannot see sex differences except as a function of our knowledge about the body”.

Gender can be defined, then, as a way of knowing that traverses and constitutes different discourses. Its potency, in tactical and strategic terms, resides in its capacity to be taken as an essential and universal nature and, therefore, non-problematized. Once individuals become gendered “subjects” in culture, it is in this field of struggles for signification that different discourses will name what is proper and adequate for men and women, and produce pedagogies of gender and sexuality. Based on the naturalization of the binary pair male and female and on heterosexuality as the normal way to exercise sexuality, certain ways of living life are produced as desirable, normal, and legitimate. And, in this dynamic, which makes social action intelligible, places, practices and subjectivities are produced that legitimize and make gender violence possible. According to Meyer (2009, p. 39): “[...] it is in the context of naturalized gender and sexuality power relations, sanctioned and legitimated in different instances of the social and cultural spheres, that certain forms of violence become possible”. In these terms, for Meyer (2009), gender violence is founded on discursive and non-discursive practices that, by instituting and prescribing the desirable and unacceptable, create conditions for violence to happen, an argument that allows fruitful articulations with the understanding of violence developed by Tereza de Lauretis (1994; 1989) about the “technologies of gender”.

Produced for/by power, gender technologies constitute “[...] techniques and strategies [...] by which gender is constructed [...]” (LAURETIS, 1989, p. 38) and, as mechanisms guided by a given rationality, they are articulated to other technologies, coordinate and compose knowledge, instruments, institutions, produce and organize spaces, distribute objects and people. Founded on and legitimated by “gender norms”, the technologies associated with them produce and incorporate mechanisms of regulation, named by Butler (2004) as “gender regulations”, technologies that aim to normalize individuals from parameters of regularity. In this mechanics that focuses on the individual and on the population in order to govern behavior, Lauretis and Butler incorporate violence as a regulatory mechanism in the order of power relations.

While crime is understood as a product of criminal classification, violence configures a broader notion that involves the social recognition of abuse, which characterizes it as a historically and culturally practice (DEBERT; GREGORI, 2008; MEYER, 2009). In other terms, from studies such as those of Fonseca (2000) and Schraiber, Oliveira, Hanada, Figueiredo, Couto, Kiss, Durand, Pinho (2003) it is possible to conceive that violence is produced in the order of language that names certain behaviors and events as violent, constructing individuals, objects and, therefore, violence itself as a social fact. Thus, understanding relationships which, to some extent, are permeated by violence, involves the need to understand the social dynamics which make them possible (ARAUJO, 2008), which demands a set of theoretical-methodological and ethical-political tools to “see” the processes related to abuse as practices socially recognized as such.

In this sense, violence is also a category formulated within a given theoretical framework, which, in the case of this text, takes the power as a key concept. Although meant and appropriated in different ways (SANTOS, IZUMINO, 2005), the notion of gender violence that we adopted is based on the following premises: it is produced in the agency of power relations, marked by asymmetries and by the intersection of gender with other social markers; gender is a regulatory norm that produces individuals and positions them in multiple arrangements and is not circumscribed only in relations between women and men.

We argue that power constitutes a field of relations that: 1) produces a set of more or less understandable and justifiable conditions for violence to happen (MEYER, 2009); 2) makes use of the effects of violence in the processes of conducting conducts, marking differences, reiterating inequalities, and focusing on the body of those who resist the norms (BUTLER, 2004). However, since the Foucauldian theorization, power relations, while offering a vigorous field to understand the dynamics between violence and gender, pose some theoretical challenges by establishing violence as something that occurs at the outer limit of these relations.

For Foucault (2012), power relations do not operate in the order of repression or coercion. Power is established in relationship, therefore, it is exercised by individuals in order to conduct practices and behaviors through convincing . In this way, to established power, it is essential that the other in the relationship is also conceived as an individual that has a field of possibilities of reactions, inventions and various responses. Resistance, in these terms, emerges as a constituent of these relations, a way of escape, even if temporary, an unimagined response that emerges in this vast field of possibilities (FOUCAULT, 2012). These assumptions bring to light another condition for the exercise of power: freedom. For Foucault, in the absence of freedom, power relations are replaced by relations of domination and the individual, prevented from acting, becomes an object (FOUCAULT, 2012)..

However, violence is not dissociated from the practices of government, being used as the ultimate resource in its procedures, an action that, despite coercing and dominating, is put into operation by a given rationality, generating effects desirable by it. Understood as “[...] a mobile element that acquires various expressions [...]”, reason, in its plurality and diversity of forms, guides and acts in numerous power relations (COSTA, 2018, p. 161). Inscribed in biopolitics, the reason that guides the government is sustained in a set of knowledges that refine the mechanisms of power and make violence possible and its effects desirable. According to Foucault (2012, p. 312) “[...] violence finds its deepest anchorage and draws its permanence from the form of rationality we use. Between violence and rationality there is no incompatibility”.

From Foucault’s notes, it is possible to think of the uses of violence as an action that aims at the adaptation of behavior to a given normality, a type of governmental procedure that goes through active maneuvers. Centered on life, the rationality linked to violence should be understood in its capacity to normaize the ways of living, dying, and procreating (COSTA, 2018).

In this same sense, but from different perspectives, Foucault (2012), Breines and Gordon (1983) problematize the thesis that characterizes violence as suspension or breakdown of order, a practice arising from irrationality or social anomaly. For these researchers, (family) violence and, therefore, gender violence is, rather, an indication of the search for the maintenance of a normalized type of social functioning by reaffirming gender expectations, submissions, and dependencies. Lauretis (1989) not only endorses Breines and Gordon's understanding but also seems to challenge the boundaries established by Foucault between power and violence by asserting that gender is constructed by technologies of gender and violence is generified and generifying. In conceiving violence and its effects in the dynamics of the technology of gender, Lauretis assumes, within the framework of Foucauldian theory, the arguments presented by Breines and Gordon (1983, p. 492) that “[...] violence is not necessarily deviant or fundamentally different from other means of exercising power over other people [...]”, it is, rather, a mechanism of the technology of gender itself.

In these terms, it seems possible to us to add the argument developed by Butler (2014) that defines gender as a norm that, as such, besides governing social intelligibility, produces regulation mechanisms that make use of gender violence as an action that intends to lead individuals to a given zone of normality.

Understood as a measure that establishes principles of comparison, the norm establishes actions that homogenize and, at the same time, highlight differences. Related to power, it acts less with force and more through an ability to (re)orient its own strategies and tactics, refining its actions and objectives to persuasion. As far as those norms are triggered, the triggering itself and its effects can rearrange their course. Thus, gender norms are only constituted as such to the extent that they produce a (re)idealized and (re)instituted social reality through the arrangements of everyday life. As a norm that establishes its own disciplinary and regulatory regime, gender is constructed through its technologies, regularities and modes of individuation, as well as classificatory parameters of persons (BUTLER, 2014). The regulatory mechanisms that are based on established gender norms are triggered both in the process of evaluating conduct and in the action of coercive apparatuses. Grounded and legitimized in the norm, gender violence, as mechanisms of regulation, function in conflict dynamics.

Based on the understanding of gender as a regulatory norm, Butler takes violence as a form of social punishment of those who transgress established and naturalized gender relations, an argument that allows us to consider the effects of such violence in the processes of hierarchy and maintenance of order based on gender and sexuality.

Thus, gender violence is conceived as an action sustained in different discursivities that designate, establish, and systematize gender and sexuality norms and produce a set of conditions that make abuses possible. In terms of regulatory norms, gender violence is triggered as a mechanism that normalizes, regulates, and determines life in the detail. Thus, amid the conflictive dynamics that turn into violence, the asymmetry and reification of gender inequalities are not only taken to the extreme but also produce effects on the processes of governing oneself and others.

The Kernel Maps, possible questions and necessary problematizations

The mapping of the regions with a history of high rates of complaints of “domestic and family violence against women” crimes was produced from the access to the addresses indicated in the occurrences registered in the Police Stations for the Defense of Women of one of the municipalities with the highest rates of feminicide in the Vale do Rio dos Sinos Region, Rio Grande do Sul.

Historically, the municipality in question accounts an average of approximately 200 occurrences of crime against women per month, which addresses refer to three types of crimes: 1) rape and rape of vulnerable persons; 2) personal injury; 3) feminicide and attempted feminicide – crimes against the person and against sexual freedom that relate the body to the occurrence of the legal fact. Regarding the years 2017, 2018 and 2019, the addresses were grouped by type of crime and, individually generated point demarcations in the software “Google Earth”, which were imported into the software “ArcGIS” to generate three vector files using the “WGS 84 Datum” and “UTM” projection. To analyze the data, we chose to create Kernel surface maps, which have the purpose of estimating the density of an event in a given study area.

Kernel maps can be understood as a regular grid, where each cel presents a density value. This value is obtained through a previously determined radius, generated around each point of the map, in which the results of the Kernel function are summed producing the density value of each point. The result is the plotting of a map represented by a color scale, which reflects the intensity of events in adjacent areas (BEATO; ASSUNÇÃO, 2008).

The “Kernel Density” tool was used to obtain a map that considers, at the same time, the three types of crime, which allowed the crossing of information based on the importance of each crime incidence. The construction of a map that took into account only the points would hide cases of rape and feminicide, due to the lower number of occurrences of these crimes compared to those of personal injury.

The results were classified on a categorical scale and then crossed using the “Raster Calculator” tool, which considers the classification of the analyzed surfaces individually and not the number of points obtained by the number of reports. Finally, the regions that reached the highest value of incidence relative to the three types of crime were highlighted as “critical” zones.

The last step in the production of the maps refers to the identification of the schools located in the vicinity of the critical zones of denunciation incidence. For this, the addresses of the municipal public schools were registered and scored in “Google Earth” software and, later, incorporated as a shape in “ArcGIS” software, which generated the identification of schools as points on the map.

Figure 1 Map of incidence of reports of domestic and family violence against women and the adjacent schools

The map is based on the assumption that the exercises of power inscribed in social relations are conditions for both the conflict dynamics and the denunciations of crimes.

In the police inquiries registered in the Police Stations for the Defense of Women, the addresses indicated as the place of occurrence of the crimes are also the addresses of the residences of at least one of those involved in the reported crime. Marked by the category “domicile”, the places highlighted on the map are taken as territories.

Understood as “[...] dynamic object, alive and full of interrelations [...]” (LIMA; YASUI, 2014, p. 596), territories are marked by exercises of power and resistance. Fruits of historical and socio-spatial processes that sustain social relations, “[...] should not be simply seen as an object in its materiality [...]” (HAESBERT, 2003, p. 13), but as living, porous, territorial of unfixed boundaries with plural and historically dated meanings. Territory is, therefore, the locus of events, manifestations, hierarchizations and daily practices in which the sharing of meanings produces understandings, even if arbitrary, contradictory and multiple, about the place. Thus, by taking territory as a “[...] continuous production of ways of life [...]” (LIMA; YASUI, 2014, p. 598) it is understood that these same ways of life are also produced in gender relations. At the limits of the exercise of gender power, gender violence interposes itself as an equally constitutive element of the territories, a practice made possible by sharing and reifying the meanings manifested in gender norms.

In this sense, locating schools in the regions indicated by the map as “critical” allows us to produce a set of questions about the ways in which gender relations are constituted in those contexts. Taking the territories as living elements that are crossed and traverse social relations and, therefore, culture, allows us to consider the schools located there as spaces where different discourses produce a complex and intricate field of dispute for signification. Thus, the school is not only the place where things happen, it is a territory that produces meanings, articulates knowledge, many of which are conflicting and apparently divergent. Understood as an institution supposedly created to produce certain subjectivities, the school activates and produces normalizing mechanisms in the process of production of gender and sexuality individuals (cf. LOURO, 1999), mechanisms which are deeply articulated to the contextual conditions and to the moral, ethical and aesthetic principles of the community where it is inserted.

In this sense, by selecting the schools based on an instrument that locates the reports in the critical zones of incidence of crimes, we consider the maps as tools that suggest certain contexts as particularly profitable to produce questions such as: Which pedagogies of gender and sexuality are activated by the schools in this context? How do gender and sexuality intersect with other socia markers in the processes of meaning production about what is acceptable and unacceptable for students? In what ways aggressiveness, force, violence, and conflict dynamics are signified and appropriated by the masculinities and femininities in course?

However, if it is possible to produce a set of questions from the maps, the materiality that informs about crime incidence zones and about the people who live there needs to be discussed, considering the effects of truth generated by its visuality and by the technical procedures employed. The process of quantification of social phenomena, according to Santos (2002), works as a strategy capable of attributing scientific, neutrality, and ideological exemption, and, therefore, a status of truth, to processes of managing life and death, at least since the eighteenth century. Especially appropriated by the normalization and control societies, the statistical data translated as percentages, indexes, graphs and tables, by saying about a given collectivity, also produce it.

Thus, spatializing gender violence without taking into account its effects of truth and without questioning its methodological and ethical limits may contribute to – at the intersection with class, race, education, among other markers – produce zones of criminality, individuals and objects of violence as a “truth” revealed through “technical exemption”. Thus, highlighting these limits and understanding this materiality and methodology as mechanisms produced and sustained by regimes of truth instituted in the present time means understanding the technique and quantification as instruments that position individuals and discourses that, through the exercise of power, name and subjectivize not only the deviations of conduct, but also the individuals of vulnerability.

In summary, the maps are the result of the use of a technique that, based on the reports of abuse and violence committed, delineates a possible territory . And, even with the limits highlighted above, the zoning in relief allows us to elaborate a productive and powerful set of questions about systems and codes of signification on which the relations and pedagogies of gender and sexuality are based, as well as the mechanisms employed in these instances and their purposes. Finally, it allows us to question what is possible, reflected upon and experienced as gender and sexuality in schools located in these regions with high rates of reported crimes of “domestic and family violence against women”.

Final considerations

The discussions and tensions put on the agenda in this text worked as a reflection process that, supported by a given theoretical-methodological matrix, allowed us to recognize the limits and possibilities of categories endogenous and exogenous to the research.

Despite the limits established by the production of meanings about what and how the notion of “domestic and family violence against women” is constituted, its understanding and its effects have produced, in legal terms, the recognition of abuse as a crime, as well as the individuals and objects of violence. In this process, data is produced and appropriated to inform about gender violence, a resource adopted in the ongoing research, to produce incidence maps of crime reports from georeferencing systems.

By placing the categories woman, crime, family and household (exogenous) under discussion, it was possible to understand a set of markers in the specificity of each concept that not only differentiate them from categories of gender, violence, power and gender violence (endogenous), but also delimit (im)possibilities of their articulations. If the exogenous categories proved insufficient from the analytical point of view, because they fix and universalize, such understanding highlights the specificities of the Kernel maps, circumscribing and refining the possible questions from their materiality and the assumptions that anchor the endogenous categories.

In recognizing the implications of the uses of the categories – woman, crime, family, and domicile – in the production of the maps, it has become fundamental to further challenge the effects of truth they produce. At the same time that the visuality and technical resources of the maps present themselves as powerfu tools for analyzing gender relations and their crossings in the social dynamics of given territorialities, they also produce regions, individuals and objects named and recognizable as violent, an ethical implication whose effects need to be considered in the methodological approaches and in the dissemination of the research results.

The challenges produced in the articulation between the concepts of gender, power and violence also allowed us to think about the processes from which violence becomes possible, as well as to take gender violence as a mechanism for regulating behaviors, a movement that seems to expand the analytical power of this category.

Between approximations and distancing, it was possible to establish some alignment between exogenous and endogenous categories to the research and, thus, recognize and indicate some of its effects (ethical, theoretica and methodological) in the instruments and techniques of investigation. This process will provide support for the next stages of the research, in which we will analyze gendered power relations that are established in the schools indicated by the maps of denunciations incidence.

Notes

1Research project entitled “Gender relations in schools located in contexts of high rates of violence experienced by women”, approved and validated by the ethics committees of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul and Feevale University, under number 88110518.2.0000.5348.

2Such terminology is adopted in the Maria da Penha Law and has been used as a descriptor of the maps produced, a strategy that aims to highlight the specificity of the mapping and what they are about: regions with high rates of reporting crimes of “domestic and family violence against women”.

3The Wording FONAVID nº 46 (2017) provides that the Maria da Penha Law applies to trans women, regardless of name change and sexual reassignment surgery, whenever the hypotheses of article 5, of Law 11.340/2006 are configured (MESSIAS; CARMO; ALMEIDA, 2020).

4The version of the bill formulated by the “Mixed Parliamentary Inquiry Commission” included the term “gender”, which was replaced by the expression “female sex conditions” by the House of Representatives through wording amendment no. 1 to Bill no. 8.305/2014 (MESSIAS; CARMO; ALMEIDA, 2020).

5Brazil became a signatory to a set of international agreements and treaties, agreeing on commitments to combat discrimination and violence against women, a movement that, by producing policies aligned to such guidelines, also generate effects on the production of meaning about what is understood by violence and women in Brazil.

6This understanding started to be problematized by feminist theorists who contest the biologics and foundationalist assumptions that support this notion of woman and some aspects of gender studies. In addition, these same theoreticians also started to suffer criticism from some feminist groups by taking the conditions of inequality in relational gender terms and “dismantling” the binary oppositions of tormentor/victim.

7The Maria da Penha Law inaugurates the notion of “Violence against Women” in legal rhetoric and practice, since the legal concepts of domestic and family violence against women only came into existence after the amendment of the Code of Criminal Procedure through the Law 11.340/2006.

8Family violence is that practiced by individuals who have some degree of kinship (consanguinity or conjugality ties) with the victim. Domestic violence refers to abuse against (or perpetrated by) persons who live partially or wholly in the household, and may or may not be related to members of the same family (BRASIL, 2010).

9Typifying refers to making abuse a crime under the law.

10Despite the possible articulations, it is worth pointing out the substantial difference in the way the authors relate violence and power. While Meyer keeps a certain distance between such concepts, Lauretis incorporates violence as a component of certain arrangements of the technology of gender, understood fundamentally as a technology of power. Later on, these issues will be better developed.

11The guidance of the conducts of self and other constitutes the purpose of “governmentality” for Foucault. “Fundamentally person-centered”, governmentality refers to the ways of governing, whose analysis highlights the rationality of the techniques and instruments that restrain the conduct of the population in a double perspective: the relationship between individuals and the government (institution/state) and the relationship of the individual with the other and with himself (FOUCAULT, 2008a).

12The analyses of power carried out by Foucault (2008b; 2010) in the history of madness and prisons allow us to understand a certain gradient between freedom, power and violence by pointing out that power is exercised even in the contexts of prisoners and convicted individuals, but within a set of limits. For Foucault, such institutions are constituted as a space of restricted and organized freedom with a propensity to coerce behavior through action on bodies..

13For this article, we decided to hide the name of the city, the neighborhoods and the schools where the areas of high incidence of crime reporting are located. However, in other spaces and circumstances, locating these regions was a politically productive strategy to foster reflections together with the Police Stations for the Defense of Women and with the partner schools.

14It is worth noting that the meanings attributed to the abuses are not universal (DUTRA, 2013); the reports registered at Police Stations for the Defense of Women depend on a set of conditions to happen. This puts under suspicion the possible understanding that the regions of the city that report the most complaints are effectively the regions where there are more crimes or gender-based violence.

REFERENCES

ARAUJO, Maria de Fátima. Gênero e violência contra a mulher: o perigoso jogo de poder e dominação. Psicologia para América Latina, México, n. 14, out. 2008. Disponível em: <http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1870-350X2008000300012&lng=pt&nrm=iso. Acessos em: 1º mar. 2021. [ Links ]

BEATO FILHO, Cláudio; ASSUNÇÃO, Renato. Sistemas de Informação Georreferenciados em Segurança. In: BEATO FILHO, Cláudio (org.). Compreendendo e avaliando: projetos de segurança pública. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2008. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Secretaria de Políticas para as Mulheres. Norma Técnica de Padronização das Delegacias Especializadas de Atendimento às Mulheres. Brasília: UNODC/ DEAMs, 2010. [ Links ]

BREINES, Wini; GORDON, Linda. The New Scholarship on Family Violence: Signs, v. 8, n. 3, 1983. [ Links ]

BUTLER, Judith. Regulações de gênero. Cadernos Pagu, Campinas, n. 42, p. 249-274, jun. 2014. Available from: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104--83332014000100249&lng=en&nrm=iso. Access on: 1º mar. 2021. https://doi. org/10.1590/0104-8333201400420249. [ Links ]

BUTLER, Judith. Undoing gender. New York: Routledge, 2004. [ Links ]

CAMPOS, Carmen Hein de. A CPMI da Violência contra a Mulher e a implementação da Lei Maria da Penha. Revista Estudos Feministas, Florianópolis, v. 23, n. 2, p. 519-531, aug. 2015. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104--026X2015000200519&lng=en&nrm=iso. Access on: 1º mar. 2021. https://doi. org/10.1590/0104-026X2015v23n2p519. [ Links ]

COSTA, Helsrison Silva. Poder e violência no pensamento de Michel Foucault. Sapere Aude, v. 9, n. 17, p. 153-170, 13 jul. 2018. [ Links ]

DEBERT, Guita Grin; GREGORI, Maria Filomena. Violência e gênero: novas propostas, velhos dilemas. Revista brasileira de Ciências Sociais, São Paulo, v. 23, n. 66, p. 165-185, feb. 2008. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102--69092008000100011&lng=en&nrm=iso. Access on: 1º mar. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-69092008000100011. [ Links ]

DUTRA, Maria de Lourdes; PRATES, Paula Licursi; NAKAMURA, Eunice; VILLELA, Wilza Vieira. A configuração da rede social de mulheres em situação de violência doméstica. Ciência e saúde coletiva, Rio de Janeiro, v. 18, n. 5, p. 1293-1304, May 2013. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413--81232013000500014&lng=en&nrm=iso. Access on: 1º mar. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232013000500014 [ Links ]

FONSECA, Claudia. Família, fofoca e honra: etnografia de relações de gênero e violência nos grupos populares. Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS, 2000. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Segurança, território, população: curso Collège de France. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2008a. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel História da loucura na Idade Clássica. São Paulo: Perspectiva. 2008b. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Vigiar e punir: nascimento da prisão. 22. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2010. [ Links ]

FOUCAULT, Michel. Estratégia, poder-saber. Ditos & escritos IV. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2012. [ Links ]

HAESBAERT, Rogério. Da desterritorialização à multiterritorialidade. Boletim Gaúcho de Geografia, v. 29, n. 1, p. 11-24, 2003. [ Links ]

LAURETIS, Tereza de. A tecnologia de gênero. In: HOLANDA, Heloisa Buarque (org.). Tendências e impasses: o feminismo como crítica cultural. Rio de Janeiro, Rocco, 1994. [ Links ]

LAURETIS, Tereza de Technologies of gender: essays on theory, film and fiction. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. [ Links ]

LIMA, Elizabeth; YASUI, Silvio. Territórios e sentidos: espaço, cultura, subjetividade e cuidado na atenção psicossocial. Saúde Debate, Rio de Janeiro, v. 38, n. 102, p. 593-606, s:ept. 2014. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103--11042014000300593&lng=en&nrm=iso. Access on: 1º mar. 2021. https://doi.org/10.5935/0103-1104.20140055. [ Links ]

LOURO, Guacira Lopes. Pedagogias da sexualidade. In: LOURO, Guacira Lopes (org.) O corpo educado: pedagogias da sexualidade. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 1999. [ Links ]

MESSIAS, Ewerton; CARMO, Valter; ALMEIDA, Victória. Feminicídio: sob a perspectiva da dignidade da pessoa humana. Revista Estudos Feministas, Florianópolis, v. 28, n. 1, 2020. Av:ailable from http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104--026X2020000100208&lng=en&nrm=iso. Access on: 1º mar. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9584-2020v28n160946 [ Links ]

MEYER, Dagmar Estermann; SILVA, André Luiz dos S. Gênero, cultura e Lazer: potências e desafios dessa articulação. LICERE – Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação Interdisciplinar em Estudos do Lazer, Belo Horizonte, v. 23, n. 2, p. 480-502, 2020. Disponível em: https://periodicos.ufmg.br/index.php/licere/article/view/24092. Acesso em: 1º mar. 2021. DOI: 10.35699/2447-6218.2020.24092. [ Links ]

MEYER, Dagmar Estermann KLEIN, Carin; DAL'IGNA, Maria Cláudia; ALVARENGA, Luiz F. Vulnerabilidade, gênero e políticas sociais: a feminização da inclusão social. Revista Estudos Feministas, Florianópolis, v. 22, n. 3, p. 885-904, dez. 2014. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-026X2014000300009&lng=en&nrm= iso. Access on: 1º mar. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-026X2014000300009. [ Links ]

MEYER, Dagmar Estermann. Corpo, violência e educação: Uma abordagem de gênero. In: JUNQUEIRA, Ricardo. Diversidade sexual na educação: problematizações sobre a homofobia nas escolas. Brasília: Editora MEC/Unesco, 2009. [ Links ]

NICHOLSON, Linda. Interpretando o gênero. Revista Estudos Feministas, Florianópolis, v. 8, n. 2, p. 9-42, 2000. [ Links ]

PASSOS, Izabel Friche. Violência e relações de poder. Revista Médica de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, v. 20, n. 2, p. 234-241, 2010. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Cecília MacDowell; IZUMINO, Wânia Pasinato. Violência contra as mulheres e violência de gênero: notas sobre estudos feministas no Brasil. In: Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y El Caribe, da Universidade de Tel Aviv. 2005. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Luís Henrique Sacchi. Biopolíticas de HIV/AIDS no Brasil: uma análise dos anúncios televisivos das campanhas oficiais de prevenção (1986-2000). 2002. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre. 2002. [ Links ]

SCHRAIBER, Lilia; d'OLIVEIRA, Ana Flávia; HANADA, Heloísa; FIGUEIREDO, Wagner; COUTO, Márcia; KISS, Lígia; DURAND, Júlia; PINHO, Adriana. Violência vivida: a dor que não tem nome. Interface, Botucatu v. 7, n. 12, p. 41-54, fev. 2003. Available from: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1414-32832003000100004&lng=en&nrm=iso. Access on: 1º mar. 2021. [ Links ]

SCOTT, Joan. Gênero, uma categoria útil de análise histórica. Revista Educação e Realidade, Porto Alegre. V. 20, n. 2. p. 71- 99, 1995. [ Links ]

Received: April 01, 2021; Accepted: May 12, 2021

texto em

texto em