Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Educação em Questão

Print version ISSN 0102-7735On-line version ISSN 1981-1802

Rev. Educ. Questão vol.60 no.63 Natal Jan./Mar 2022 Epub Feb 22, 2023

https://doi.org/10.21680/1981-1802.2022v60n63id28494

Artigo

Reminiscences of the first teacher of d. Pedro II: Mariana Carlota de Verna

2Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Brasil)

The study addresses the trajectory of Mariana Carlota de Verna as the first teacher of d. Pedro II, and what led her, later, to receive the title of Countess of Belmonte. The main objective is to highlight the circumstances in which she assumed the position of preceptor of the heir to the throne of Brazil and some of the difficulties she faced to remain in it until the sovereign’s majority. On a more specific level, we sought her mentions in the periodicals of the time, analyzing how she was seen and portrayed in the nineteenth-century society of the Second Reign. The methodological procedures refer to a historical and essentially documental research, whose sources were, to a large extent, consulted in the personal archive of a countess’ descendant, besides being collected in periodicals from the newspaper library of the National Library and in studies already carried out on her. We concluded that Mariana Carlota de Verna had a strong influence on the emperor, although she kept a certain discretion in relation to her position, being considered the reference of maternal affection for d. Pedro II.

Keywords: Mariana Carlota de Verna; Preceptor; D; Pedro II; Brazil Empire

O estudo aborda a trajetória de Mariana Carlota de Verna como primeira mestra de d. Pedro II, e o que a levou, posteriormente, a receber o título de condessa de Belmonte. O objetivo central é evidenciar as circunstâncias em que assumiu o cargo de preceptora do herdeiro do trono do Brasil e algumas das dificuldades que enfrentou para se manter nele até a maioridade do soberano. Em um plano mais específico, buscou-se as suas menções nos periódicos da época, analisando-se como ela era vista e retratada na sociedade oitocentista do Segundo Reinado. Os procedimentos metodológicos remetem a uma pesquisa histórico e essencialmente documental, cujas fontes foram, em grande parte, consultadas no Arquivo Pessoal de um descendente da condessa, além de recolhidas em periódicos da hemeroteca da Biblioteca Nacional e em estudos já realizados sobre ela. Conclui-se que Mariana Carlota de Verna possuía uma forte influência sobre o imperador, embora tenha mantido certa discrição em relação a sua posição, sendo considerada a referência de afeto maternal para d, Pedro II.

Palabras clave: Mariana Carlota de Verna; Preceptora; D; Pedro II; Brasil Império

El estudio aborda la trayectoria de Mariana Carlota de Verna como primera maestra de d. Pedro II, y lo que la llevó, posteriormente, a recibir el título de Condesa de Belmonte. El objetivo principal es resaltar las circunstancias en las que asumió el cargo de institutriz del heredero al trono de Brasil y algunas de las dificultades que enfrentó para permanecer en él hasta la mayoría de edad del soberano. En un nivel más específico, se buscaron sus menciones en los periódicos de la época, analizando cómo era vista y retratada en la sociedad decimonónica del Segundo Reinado. Los procedimientos metodológicos se refieren a una investigación histórica y fundamentalmente documental, cuyas fuentes fueron, en gran parte, consultadas en el Archivo Personal de la descendiente de la Condesa, además de estar recogidas en periódicos de la hemeroteca de la Biblioteca Nacional y en estudios ya realizado sobre ella. Se concluye que Mariana Carlota de Verna ejerció una fuerte influencia sobre el emperador, aunque mantuvo la discreción en relación con su cargo, siendo considerada la referencia del afecto maternal por d, Pedro II.

Palabras clave: Mariana Carlota de Verna; Institutriz; D; Pedro II; Imperio de Brasil

Introduction

This research focuses on reconstructing the trajectory of a woman, among many, who has been forgotten and silenced in Brazilian historiography. Whether because she was closely linked to the monarchy, or because she was a noblewoman in a world where this position no longer fit, Mariana Carlota de Verna, the Countess of Belmonte, went from notoriety in the periodicals of her time to total oblivion in the future, although she played a crucial role in imperial politics, after having received an invitation from d. Pedro I to be the maid1 of his son, Pedro de Alcântara, who would later become Emperor of Brazil.

Mariana Carlota de Verna Magalhães Coutinho2 came to Brazil in 1808, along with her husband, Joaquim José de Magalhães Coutinho, and a couple of children, accompanying the Portuguese royal family, when the Court was transferred to this country, fleeing from the Napoleonic invasions (NORTON, 2008; MEIRELLES, 2015).

Like other noblemen who accompanied the royal family, Mariana Carlota de Verna occupied a prominent position at the Portuguese Court, since her family already provided services to the monarchy. Her father, Captain Ernesto Frederico de Verna3, according to documents from the Military Historical Archives of Lisbon, distinguished himself by his military achievements, commanding the 1st Regiment of Olivença and the 1st Regiment of Porto, for which he fought in the Roussillon and Catalonia Wars. He died in battle in 1795, leaving a son and three female daughters4, among them Mariana Carlota de Verna.

Mariana Carlota de Verna was born on February 5, 1779, in the city of Elvas, former province of Alentejo, in Portugal. The girl was baptized at ten days of life by her uncle, the canon vicar of Santa Fé de Elvas and vicar general of the bishopric, Pedro Antonio de Souza Almeida Castellobranco, in the church of São Salvador, having as godparents the general José Joaquim de Mello e Lacerda5, and Anna Vicencia de Souza Almeida Castellobranco, represented by her brother José Antonio de Souza Almeida Castellobranco, both uncles of the baptized6.

The marriage register of Joaquim José de Magalhães Coutinho and Mariana Carlota de Verna dates from September 21, 1796, and was performed at the Parish of Nossa Senhora da Lapa, in the city of Lisbon7. On that occasion, the future countess was already 17 years old and an orphan. The couple had three children, Ernesto Frederico de Verna Magalhães Coutinho, born on May 8, 1799, in Lisbon; Maria Antonia de Verna Magalhães Coutinho, born on December 26, 1806, also in Lisbon; and Leopoldina Isabel de Verna Magalhães Coutinho, born on January 22, 1817, in Rio de Janeiro. It is believed that the choice of the youngest daughter’s name was in honor of the Empress Leopoldina, because the date of the marriage with Pedro I, on November 28, 1816 (REZZUTTI, 2017b), as well as the disclosure in the periodicals of the time8, was very close to the birth of Mariana Carlota de Verna’s daughter.

Along with some information about Mariana Carlota de Verna until her establishment at the Court of Rio de Janeiro (CUNHA, 2021), this article aims to verify the circumstances that led this woman to an important position in the Brazilian imperial house and, later, to receive the title of Countess of Belmonte, which gave her the notoriety, forged in the periodicals of Rio de Janeiro and other provinces, during and after the exercise of her functions as the sovereign’s maid.

Thus, the central objective is to highlight the context in which she assumed the position of preceptor to the heir to the throne of Brazil and some of the difficulties she faced to remain in this position until the emperor’s majority. On a more specific level, we sought her mentions in the periodicals of the time, analyzing how she was seen and portrayed in the nineteenth-century society of the Second Reign.

To this end, the methodological procedures used refer to those related to historical and essentially documental research, whose sources and collections consulted were largely acquired by Manoel Ignacio Cavalcanti de Albuquerque, great-great-grandson of the Countess of Belmonte, from the originals existing in the National Library of Elvas, Portugal, which today belong to the Personal Archives of Luciano Cavalcanti de Albuquerque (LCA), also a descendant of the countess.

By working with the aforementioned personal archive, the historiographical operation carried out approaches that described by Cunha (2019), when he states that this type of documentary set makes it possible to know individuals in their life stories, their memories and their experiences, as well as:

[...] to size up the undertaking of their authors, who, by valuing certain events and experiences, signaled not only their desire for immortality but also to preserve actions and achievements, of their own and of those of their contemporaries, avoiding both their erasure and forgetting and remitting to the future the understanding and judgment of the plots of which they were participants (CUNHA, 2019, p. 28-29).

Besides the personal archive, other memorialistic information about the countess was obtained in biographical works, especially Henri Raffard’s Apontamentos acerca de pessoas e cousas do Brasil (1899) – Notes about people and things of Brazil –, partly produced on the accounts of her granddaughter, Francisca Carolina de Verna Magalhães Fonseca Monteiro de Barros.

As for the periodicals, they were accessed and researched in the digital newspaper archive of the National Library by consulting the pages referring to the period between 1808 and 1855, i.e., from the time Mariana Carlota de Verna arrived with the Portuguese royal family in Brazil until her death in 1855. However, the search was extended to the year 1859, since the time intervals in the digital newspaper archive website are nine years.

The words used to conduct the search were Mariana Carlota de Verna’s full name; the way the young monarch called her, “Dadama”; and, finally, her title of nobility: “Countess of Belmonte”. From the years cited, Mariana Carlota de Verna appears in the periodicals from 1834 to 1857, but the publications intensify after 1844, the year in which she received the title of countess.

References to the countess were found in news from several newspapers and magazines, even from other provinces, as, for example: O Diario Novo (Pernambuco)9, O Globo Jornal Commercial Litterario e Politico (Maranhão)10, and A Revista – Folha Política e Litteraria (Maranhão)11, mentioned in this study. However, most allusions to it appear in the periodicals of the Court in Rio de Janeiro, among them, Jornal do Commercio, Almanak Administrativo Mercantil e Industrial do RJ; O Republico; Diário do Rio de Janeiro; and Correio Mercantil e Instructivo, Politico, Universal.

Among the periodicals cited, it is worth mentioning those that constantly mentioned the countess, such as the Almanak Administrativo Mercantil e Industrial do RJ, in which she is present in the annual editions; besides the Correio Mercantil e Instructivo, Politico, Universal, which records her social appearances; as well as those in which she is criticized, as in the Diário do Rio de Janeiro.

The periodical Almanak Administrativo Mercantil e Industrial do RJ, also known as Almanak Laemmert, was published from 1844 to 1889 by Tipografia Universal de Laemmert (Laemmert’s Universal Typography), which operated on 71 Lavradio Street, in the Lapa neighbourhood, and later on 61B Inválidos Street, in downtown, both in Rio de Janeiro city. The typography started its activities in 1838 and its founders were the brothers Eduard and Heirich Laemmert, two Frenchmen who immigrated to Rio de Janeiro. The Almanack Laemmert is considered the first almanac in Brazil and had much importance and diffusion at the time (LIMA, 2006; DONEGÁ, 2012; ANTUNES, 2015). Its edition was annual and brought all kinds of announcements, private and public, publications of the Court, data from institutions, transport routes etc. It had a plethora of information in a single printed material, composing a very detailed portrait of that society. In it, the Countess of Belmonte appears in all the editions from 1845 to 1855, the year of her death, especially in the list of nobles of the Imperial Court.

The Correio Mercantil e Instructivo, Politico, Universal was a periodical that circulated from 1848 to 1868, with daily four-page publications divided into diverse sections, such as: news from abroad, diverse news, maritime notices, announcements, and auctions. It had political and literary columns in the form of pamphlets and chronicles. It was printed in the typography of the owner of the periodical, Francisco José dos Santos Rodrigues, located at 13 Quitanda Street, in Rio de Janeiro (ABREU; TOGNOLO, 2015). In this newspaper, the countess was invariably exalted in her public appearances, contributing to the propaganda of her proximity to the imperial family.

The Diário do Rio de Janeiro was the first daily newspaper published in the country and ran from 1821 to 1878. Its founder, Zeferino Vitor de Meireles, obtained an official license to open a typography, the Tipografia do Diário, located at 79 Ajuda Street in downtown Rio de Janeiro. In the first edition, the editor emphasized that the periodical would be essentially informative, with various commercial ads and news about various publications, keeping out of political discussions (CLAUDIO, 2016). From 1845, however, the periodical underwent an expansion in all senses and included political themes, literary columns and international news, remaining this way until its extinction. In an 1847 edition, the countess is accused of influencing the monarch in government decisions, calling attention to the fact that she was a woman and had influence with the emperor in political matters.

Along the same critical line, the newspaper O Republico questioned the title of the Countess of Belmonte, highlighting her role in palace life. Launched in Rio de Janeiro in October 1830, it circulated irregularly until December 15, 1855. Edited by Antônio Borges da Fonseca, a supporter of the implementation of the republican regime in Brazil, it was a periodical of liberal inclination, which made opposition to conservative and monarchist groups.

According to Tânia de Luca (2011), when working with news from periodicals, one must consider the motivations that led to the decision to make something public, besides noting that the news is impregnated by political biases that must also be analyzed. During the first half of the 19th century, much of the press was controlled by the monarchy, which imposed a certain type of censorship. Thus, the mentions of the Countess of Belmonte, in this period, are mostly praiseworthy. However, in some of them, it is possible to notice a depreciative tendency, or even an explicit criticism, although to a lesser extent.

Anyway, the several allusions to Mariana Carlota de Verna in the periodicals of the Court, from chambermaid to Countess of Belmonte, give an idea of the profile of this woman and her public activities, always marked by having been the first teacher of Pedro II and his maternal reference.

De dama Corte à “aia” de d. Pedro II: resistindo às intrigas palacianas

Arriving in the city of Rio de Janeiro along with the royal family, Mariana Carlota de Verna and her husband started a life surrounded by simplicity and the need to adapt to a reality quite different from the one they were used to in the official residences of Portugal, full of luxury and comfort. Life at the Brazilian Court, at the beginning of the 19th century, was considered exotic to the newcomers, considering the landscape, the climate, and the inhabitants, which constituted a scenario quite different from a European Court.

Maria Graham (1990) relates in her memoirs some of these characteristics of the Rio de Janeiro Court during the reign of Pedro I, which, although it had evolved since the transfer of the royal family to Brazil, still had a certain improvisation in relation to ceremonies and protocols. For the Englishwoman, who was to be the preceptor of the emperor’s eldest daughter, Princess Maria da Glória, it was an immense challenge to educate a noble child in the midst of the lack of common rites in European palaces. In trying to implement them in the princess’ room, Maria Graham soon realized how difficult it was to occupy the position of preceptor in the family of the sovereign of this country, being suddenly dismissed by him, and leaving her impressions about the period – less than two months – that she spent in the function, detailed and published in her memoirs about d. Pedro I12.

If numerous qualities and capacities were required of the person chosen to be the maid of the emperor’s wife, Princess Maria da Glória, even greater challenges were required of the person who would take care of the male child, Prince Pedro II, especially because of palace intrigues.

Still in 1825, d. Pedro I had, once again, the task of choosing a preceptor, since the empress was pregnant again and it was expected that it would be a male child, that is, the heir to the throne. Therefore, the responsibility increased, considering that the job of preceptor of a future emperor was considered a function of State.

The chosen one was Mariana Carlota de Verna who, by then, was already a widow and aroused the admiration and respect of d. Pedro I, besides having a high prestige at Court. Her choice occurred because, besides being Portuguese, which would avoid the problems already experienced with Maria Graham, she was considered a very distinguished, cultured lady, of great catholic faith and from a good family, attributes that made her the right person to take care of the August child.

According to Vasco Mariz (2016), before the choice for the maid, in one of his visits to the Engenho Novo farm, Mariana Carlota de Verna’s residence, the monarch, who had a reputation as a ladies man and conqueror, “wanted to court” her, but the lady elegantly dodged the jokes.

Although there is not enough historical evidence to prove any relation between the romantic interest of the emperor, according to the account of Vasco Mariz (2016), and the invitation to be a maid, the fact is that d. Pedro I was a very ladies’ man and, even with the significant age difference between the two – he was 27 and Mariana Carlota de Verna, 46 – it is possible that he was interested in the future preceptor of his children, because, according to Setúbal (1993), besides being charming, she had an unquestionable beauty in relation to the other women of the Court.

However, we deduce that the real reason that led the emperor to choose Mariana Carlota de Verna for the position of his unborn son’s maid was her exemplary conduct, her modesty and the devotion that her family had always shown to the monarch. Thus, convinced that she was the person capable of masterfully taking on this occupation, he spared no effort to convince her to accept the invitation. One month before the birth of the child, d. Pedro I had already highlighted “D. Mariana” to be his son’s maid, motivated by her virtues and her unusual knowledge among the ladies of the time (FREITAS, 2001).

However, according to Raffard (1899) and Lyra (1977), initially, the widow declined the invitation alleging that she was already 46 years old and had three children under her guardianship, the youngest being 8 years old. In addition, she had all the obligations at her farm in Engenho Novo, including with other family members and the servants who lived there. D. Pedro I insisted with her, saying that everything would be under her responsibility, so that, in the middle of 1825, everyone from the Engenho Novo farm was employed in the São Cristóvão Palace, starting a public life for Mariana Carlota de Verna as preceptor of the future emperor.

The birth of d. Pedro II, on December 2, 1825, strengthened the monarchy at that troubled time. The emperor had proclaimed Brazil’s independence and gave a legitimate Brazilian heir to the throne. There was much celebration of his birth, with three days of parties, to the sounds of cannons and bells (REZZUTTI, 2019a). It was at this time that Mariana Carlota de Verna settled in the São Cristóvão Palace, at the service of the imperial family, to assume the position of little d. Pedro II’s maid. In a letter addressed to her son, Ernesto Frederico de Verna Magalhães Coutinho, dated January 27, 1826, she reported her satisfaction with the position and the recognition she was getting.

[...] well rewarded with the good treatment I have received from the Emperor. I am treating our Prince, which is enough to ease my sorrows and all the work I have, which I am getting used to with perfect health, and everything is paid for with a cheerful face and the Father’s approval. To everything that I do he has not yet found any recommendation to make, he always tells me, “You understand this better than I do”, is all one can hope for, so that everyone else follows suit […] while for the others, rest assured that I am very well. [...] In the Prince’s room a rotten peace reigns, from us to the girl in the room. Every day I hear only happy speeches in which they repute themselves for being with us. I am everyone’s lawyer, and anything they want, they come to me, so I think of myself as at home. This, you will say, is a lot of presumption, but I also tell you so that you will know that you do not have such a bad mother [...] (RAFFARD, 1899, p. 161).

Henri Raffard (1899) says that Leopoldina relied entirely on Mariana Carlota de Verna and her daughter Maria Antonia to take care of Princess Francisca and the crown prince. The empress, on the other hand, was divided between her role as mother, her studies, and her participation in politics. Added to that, she faced many personal problems, from the departure of her friends José Bonifácio and Maria Graham from the palace, to the humiliations she suffered with the presence of her husband’s mistress, the Marquesa de Santos13, in her house and throughout the Court (CARVALHO, 2007).

Feeling down and physically weakened, after complications from a miscarriage, on December 11, 1826, Empress Leopoldina died. There was great consternation in the city, as she was much loved and admired by the population. After Leopoldina’s death, d. Pedro I continued his affair with his mistress for two more years, but opted to marry a noblewoman, who was incessantly sought after in Europe, in view of the fiancé’s bad reputation that kept all the suitors away. Finally, he was accepted and married by proxy to the German princess Amelia of Leuchtenberg who, at the age of 17, arrived in Rio de Janeiro on October 16, 1829.

However, d. Pedro I’s popularity only decreased, as, besides the rumors that circulated about the circumstances of Empress Leopoldina’s death, he lost the Cisplatine War, had frequent conflicts with the Chamber of Deputies, and was obsessed with handing over the throne of Portugal to his daughter Maria da Glória. In 1831 the situation reached its limit and after several manifestations of hostility to him, he had no alternative but to abdicate the throne on April 7, 1831, in favor of his son.

Before returning to Portugal, by decree, d. Pedro I named José Bonifácio as tutor to the future emperor. On April 9, 1831, the child d. Pedro II, motherless and now without his father and stepmother, was taken to the City Palace in the company of Mariana Carlota de Verna, his maid, to be acclaimed emperor.

After a legitimacy dispute with the General Assembly to keep the wish of d. Pedro I, the nomination of José Bonifácio as tutor of the prince, the dispute was solved with the holding of an election to validate the guardianship of d. Pedro II and his sisters (RANGEL, 1945). In face of the stress caused by the dispute, already with less power, José Bonifácio took office as tutor four months after d. Pedro I’s departure, on August 24, 1831. From April to August, the Marquis of Itanhaém held the position. Even with all the crisis and political clash in the Regency period, the young monarch meant two of main goals in life for José Bonifácio: the monarchy and the unity of the country (CARVALHO, 2007). When he took office, José Bonifácio was already 68 years old and it wasn’t long before the coexistence in the Palace between him and Mariana Carlota de Verna started to generate conflicts.

The strangeness between them started when the tutor named Ana Romana de Aragão Calmon, the Countess of Itapagipe to the position of chambermaid in March 1832, leaving Mariana Carlota de Verna dissatisfied for feeling left out (FREITAS, 2001). With this, José Bonifácio, who already faced resistance in politics, also started to encounter it inside the palace. Two groups were formed among the ladies of the Palace, one in favor of the Countess of Itapagipe and of the niece of Mariana Carlota de Verna, Joaquina Adelaide de Verna e Bilstein, and the other commanded by Mariana Carlota de Verna, her daughter Maria Antonia, her niece Maria José de Verna e Bilstein and the sisters Marianna and Joanna Pinto (RAFFARD, 1899).

According to Rangel (1945, p. 85), the courtly manner of Mariana Carlota de Verna and the arrogance and presumption of José Bonifácio placed them in incompatible positions, with one displeasing the other. For the author, José Bonifácio was a cultured and friendly man, but a bit harsh, and “[...] could not support with bonhomie that nest of envies and appetites of various jobs and half height, in the administrative and domestic round of a house [...]”. Certainly, there must have been a lot of power struggle in that house and Mariana Carlota de Verna would have been at the center of it, since she probably considered herself to be close to d. Pedro I and chosen by him to be his son’s maid. As the tutor was the maximum figure inside the São Cristóvão Palace, dealing with all the charges of the children’s education and the functioning of the house, it is believed that he came into conflict with Mariana Carlota de Verna for judging that some of her decisions or ways of acting clashed with what he believed to be correct.

Another question Rangel (1945) raises is the possibility that the tutor had as principle that the education of a prince should be given exclusively by men, thus having a certain fear of the female supremacy that Mariana Carlota de Verna exercised in the education of d. Pedro II. However, it is an assumption that the tutor had read and was sympathetic to a manuscript from the National Library of Paris that supports opposition to women in the education of King John V.

Henri Raffard (1899) believes that José Bonifácio was influenced to believe that Mariana Carlota de Verna was conspiring against him and plotting his departure with the wife of Aureliano de Souza Coutinho, his enemy, and the butler Paulo Barbosa. What is known for sure is that two sides were established in the palace: one supporting the tutor, and the other against him. And this internal division was perceived by political groups opposed to José Bonifácio, who used it to achieve their purpose, to dismiss the tutor. The so-called Clube da Joana (Joana’s Club), a name given to a group of friends and politicians to which the minister of justice, Aureliano Coutinho belonged together with Paulo Barbosa, was opposed to José Bonifácio and feared the return of d. Pedro I.

According to Carvalho (2007), the tutor of d. Pedro II allied with the caramurus (the name by which all those who revolted against the imperial government called the imperial soldiers in the Farrapos’ War – Rags’ War) and even took part in conspiracies inside the São Cristóvão Palace, aiming the emperor’s return, and, with this, his relations with the Regency became unsustainable. In the midst of so much chaos, the tutor suffered another hit, this time from fate: Princess Paula Mariana, at the age of 9, died of malaria and hepatitis, on January 16, 1833. The girl’s death severely shook her brothers and everyone in the house, including Mariana Carlota de Verna, who took care of the princess during the eleven days she was ill and held her in her arms at the moment of her death (CALMON, 1938). As he was responsible for the children’s welfare, the death of one of them put in doubt his competence in performing the job (FREITAS, 2001).

At the height of the palace intrigues, in August 1833, Mariana Carlota de Verna and her daughter Maria Antonia were dismissed from their positions by José Bonifácio, who nominated as chambermaid the Countess of Itapagipe to occupy, concomitantly, the position of d. Pedro II’s maid. Even after she left the position, Mariana Carlota de Verna kept her room in the Palace, as she continued to frequent it, especially when the young monarch was ill (RAFFARD, 1899).

For Rangel (1945, p. 122), José Bonifácio, when removing Mariana Carlota de Verna from her position as maid, signed his own expulsion sentence, because “that Portuguese woman” had the sympathy of almost everyone in the Palace and of “Clube da Joana” (Joana’s Club). Moreover, the palace intrigue went beyond the walls of the Palace and spread to the whole city, which sided with Mariana Carlota de Verna and clamored for the tutor’s departure. On December 2, there was a riot and cries of “Down with the tutor!” at a performance in the São Pedro’s Theater, at which the whole Court was present. On this occasion, ironically, the minister Aureliano Coutinho himself made a speech trying to calm the spirits (RANGEL, 1945).

Finally, on December 14, José Bonifácio’s suspension was decreed and the Marquis of Itanhaém was nominated as d. Pedro II’s tutor, and ordinances were issued obliging those responsible for the main services of the São Cristóvão Palace, the Santa Cruz Farm, and the Treasury of the Imperial Household not to accept any order that came from José Bonifácio (RANGEL, 1945).

The next day, the government ordered him to leave the São Cristóvão Palace, but José Bonifácio reacted to the order and only after seven hours of resistance, he was taken to his country house in Paquetá island, where he was to stay in a kind of prison-exile (FREITAS, 2001). The new guardian, appointed temporarily on December 14, 1833, was the Marquis of Itanhaém, a retired military officer, a man who did not take part in the Regency’s political quarrels. On August 11, 1834, the name of the new tutor was accepted by the Legislative General Assembly (RAFFARD, 1899). Mariana Carlota de Verna was advised by Paulo Barbosa, with rejoicing over the overthrow of José Bonifácio, as the letter shows:

Your Excellency Madam. The tutor is under arrest and in his place is the Marquis of Itanhaém. The governors are expecting Your Imperial Majesty and A.A. right now and want the tutor to summon Your Excellency to the Palace; however, by order of the governors, please come to the city’s Palace today as soon as possible, where you will receive the tutor’s order. Please accept my congratulations. Yours faithfully and affectionately servant. Paulo Barbosa da Silva (BARBOSA apud RAFFARD, 1899, p. 358).

Aureliano Coutinho, Minister of Justice, in a letter, also congratulated Mariana Carlota de Verna for the fall of the tutor, showing that Palace intrigues played a key role in the overthrow of José Bonifácio and that she was a key player. In other words, despite being a woman who lived in a male universe, silenced by the opposite sex (PERROT, 2005), her voice, appropriated by men, was decisive at that time.

Congratulations, Madam, it was hard, but we overturn the colossus on the ground: the conspiracy was ready to explode any day now, and they even distributed 18,000 cartridges and some weapons the day before yesterday; everything was discovered and arranged in time; the former tutor resisted the Regency’s orders and Decree, and it was necessary to use force and arrest him. It would be good for you to come to my house today, since we are going to speak to the new tutor to call you to the Palace, because it is very convenient that you have a friend and trustworthy person next to the Monarch – I have no time for anything else – I am Your Excellency’s affectionate respectful and servant. Aureliano (COUTINHO apud RAFFARD, 1899, p. 358-359, emphasis added).

As soon as the new tutor took office, he called Mariana Carlota de Verna and her daughter Maria Antonia to return to the Palace, this time as interim chief chambermaid, registered in a decree of September 1, 1834, becoming titular on August 1, 1840, and remaining so until d. Pedro II’s majority (RAFFARD, 1899).

The countess in the periodicals of the time: the notoriety of the courtesan

The Countess of Belmonte was one of the few noble women, besides the representatives of the imperial family, who had great notoriety in the press, both at the Court of Rio de Janeiro and in other provinces, as can be observed in the periodicals of the time. Between 1834 and 1857, Mariana Carlota de Verna appears in 73 occurrences in newspaper and magazine articles, intensifying her citation in the periodicals after she obtained the title of countess by the imperial dispatch of May 05, 1844.

It is worth noting that the decree appointing Mariana Carlota de Verna as Countess of Belmonte is much later than the beginning of her work as preceptor. When d. Pedro II made her countess, he was 18 years old and a married man; he no longer needed a maid, or a preceptor. The countess, in turn, was 65 years old, an advanced age for the time.

It is noted that this is one of the first actions that d. Pedro II took when he was consolidated as emperor, and the first of its kind that he executed in relation to a woman. Probably, the emperor wanted to repay his former maid with a title of nobility, in gratitude for her services during his childhood and teenage years.

However, Mariana Carlota de Verna began to be mentioned in the periodicals when she still held the position of chambermaid, starting in 1834. Silva Maia (1940, p. 110) explains that this position was considered superior to other ladies at the Palace, and was held by a noblewoman who served the empress and her daughters, with privileges such as: “[...] in the acts, in which the ladies have a seat in the presence of Her Majesty, she always had the preeminence of sitting on a cushion, even though she was not a marquise”. This explains, in part, the heated contention and disputes that occurred around the position that, by itself, already conferred high prestige. Mariana Carlota de Verna is reported as occupying this position in the Jornal do Commercio (RJ), November 8, 1834, when she had not yet received the title of countess.

In addition to this occurrence, thirteen other references were found in the periodicals researched, in later years, that mention her as head chambermaid of the imperial palace, some even though she already had the title of Countess of Belmonte.

Yesterday (the 15th) took place the christening of His Royal Highness the newborn princess, who received the names D. Isabel-Christina-Leopoldina-Augusta-Michaela-Gabriela-Raphaela-Gonzaga. The godmother was His Majesty the widow Queen of Naples and the godfather His Majesty the King of Portugal. Around 5 o'clock in the afternoon, the empress’ chief steward, Mr. Ernesto Frederico de Verna Magalhães, dressed in rich clothes of crimson velvet and sackcloth, went, by order of His Majesty, to the respective chamber; and receiving there the August princess from the hands of her maid, led him in his arms, and among the godfathers, to the canopy room, being followed by the chambermaid the Countess of Belmonte, and by her maid Rita Rosa (RIO DE JANEIRO, 1846, p. 2, emphasis added).

As we can see, Mariana Carlota de Verna also made her son, Ernesto Frederico de Verna Magalhães, major butler of Empress Teresa Cristina de Bourbon, wife of Pedro II, which shows the personal advantages of her influence with the imperial family.

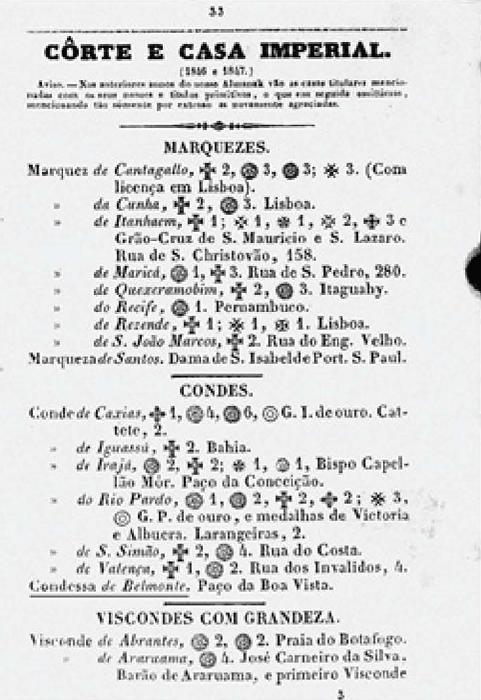

After being named countess, Mariana Carlota de Verna also began to have her name published in the lists of nobles of the Court, in which she appears annually in the periodicals from 1845 to 1855, the year of her death, as the example highlighted in figure 1.

Source: National Library digital newspaper archive

Figure 1 List of nobles taken from the edition 05, of the year 1848, of the Almanak Administrativo, Mercantil e Industrial do Rio de Janeiro RJ – Almanak Laemmert

When the above list is analyzed, draw attention the difference between men and women with titles of nobility. The Countess of Belmonte is the only woman among six men with the same hierarchical title, in the years 1846 and 1847 at the Court of Rio de Janeiro. Besides the Countess of Belmonte, only the Marquise of Santos appears in these years among the nobles of the Imperial House. According to Schwarcz (1998), during the empire in Brazil only 2.5% of all the titles of nobility were granted to the female gender.

For her services to the imperial family, Mariana Carlota de Verna received the third nobility title in the existing hierarchy, behind only the duchess and marquise titles.

Regarding this theme, in 1854, the periodical O Republico, from Rio de Janeiro, published an article criticizing the distribution of nobility titles by the monarchy, and ended it by mentioning the countess.

Human patience has limits; it is not possible to suffer eternally; and Brazil is not a farm whose fruits are exclusively for some 50 families. [...] Read this monstrous and scandalous list of dispatches, and you will see the injustices, the petty persecutions on one side, and the scandalous patronage on the other. It is not possible to analyze here all the men who obtained attention from the ministry, nor all those who were forgotten by the government; or of those, over whom the government extended its protective mantle (A MEMORAVEL MOXINIFADA DO DIA 2...,1854, p. 2).

As regards Mariana Carlota de Verna, the news item at the end questioned her receiving the title of countess instead of that of marquise: “The Lady Countess of Belmonte, who received the emperor in her arms, had no right to the title of marquess?” (A MEMORAVEL MOXINIFADA DO DIA 2...,1854, fl. 2). However, it can be deduced that d. Pedro II’s choice of the countess’ title instead of marquise to ennoble his maid was to avoid comparisons or the memory of the reasons that led to the granting of the title of marquise to Domitila de Castro Canto e Melo. The other option would have been duchess, but this title was reserved for members of the royal family.

The periodical Diário do Rio de Janeiro, from 1847, also insinuates that the countess was part of the group that would be ruling the monarch:

This time it won’t be such or such a man who will rule the monarch, and trace his conduct, it will be everyone who lives or has entrance to the palace, the doctors, the Countess of Belmonte, the Bishop of Crysopolis, Mr. Aureliano, the servants large and small! (A OPPOSIÇÃO E A CORÔA, 1847, p. 2).

Mariana Carlota de Verna was a woman with a strong personality who was close to the emperor since his birth, playing the role of second mother and preceptor, so it is possible that she was also a kind of advisor, exerting influence on d. Pedro II’s decisions.

The fragments of the periodicals cited also reflect, to a certain extent, the space destined to women in the 19th century. The question of the influence over the emperor was even more serious when the emperor was a woman, The question of the influence over the emperor became more serious because it was a woman’s influence. Women could not occupy a place of prominence and power in that society. They were only destined to domestic services and child care (PERROT, 2005). However, Mariana Carlota de Verna went beyond, and her intimacy with the emperor, whom she raised since birth, combined with her strong personality, made her an unusual woman for her time, and, although she tried to act with discretion, she certainly occupied a position of prestige and importance in the Court of d. Pedro II.

Aware of the countess’ prestige, some periodicals of the time tried to praise her, registering her presence in certain social occasions, such as receptions, masses etc. In this sense, several mentions of her name are found on these occasions, both in the periodicals of the Court, such as Correio Mercantil, and Instructivo, Politico, Universal, in the years 1852, 1853 and 1855, and in the provinces, for example, in O Globo Jornal Commercial Litterario e Politico (Maranhão) of 1854.

In the periodical O Globo Jornal Commercial Litterario e Politico (Maranhão) the presence of the countess of Belmonte was announced, in celebration of holy week, as one of the distinguished guests of the Count of Redondo, and she was the musical attraction, singing a religious solo. Apparently, the countess was part of a group of friends who gathered to enjoy music, called the “Society of Friends of Music”.

Mariana Carlota de Verna also appears in publications relating to another social group called “Servas do Senhor” (Almanak Administrativo, Mercantil e Industrial do Rio de Janeiro, 1849). These articles show the notoriety given to the countess, since she was the only lady mentioned in the periodicals among all the ladies present at the occasions reported. Nineteen publications, a high number, are also highlighted in the news in which the countess acts as a representative of some noble godmothers, as in the periodical A Revista – Folha Política e Litteraria (Maranhão) of the year 1847.

The death of the countess, which occurred on October 17, 1855, was reported in different periodicals in Rio de Janeiro and also in other provinces. The publications praised the qualities of Mariana Carlota de Verna and her contribution to the education of d. Pedro II and his sisters, as in the Diário do Rio de Janeiro: “The Countess of Belmonte was the oldest maid of honor, and her virtues, dedication to the August imperial people will make her worthy of all the respect and consideration” (CRHONICA DIARIA, 1855, page 1).

Even after her death, there continued to be mentions of Mariana Carlota de Verna’s name in the Court’s periodicals, such as Diário do Rio de Janeiro, Almanak Administrativo, Mercantil e Industrial do Rio de Janeiro and Correio Mercantil, and Instructivo, Político, Universal, between the years 1856 and 1857, demonstrating that the countess, at that time, took time to be forgotten, prolonging her erasure.

Final considerations

According to Perrot (2005, p. 34), “[...] the 19th century city is a sexed space [...]”, in which there is an absence of women as protagonists in the historical narratives. Generally, they were placed in the shadow of men, excluded from the decisions and, also, silenced, or else, they were portrayed with pejorative stereotypes, as vociferous, hysterical and megalomaniac women.

In this way, the importance of bringing up reminiscences about the Countess of Belmonte is reinforced, considering that, despite appearing in the list of nobles together with the Marquise of Santos, she did not manage to have any memory, either good or bad, beyond her time, although she had a role as relevant as that of the marquise in influencing an emperor and much longer lasting.

Her tombstone in the São Francisco Xavier cemetery, in the Caju neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro, already almost erased, also makes it difficult to read exactly what is written. It is a simple funerary monument, without any sculpture, with a stonework frame, made of light marble. There are no pictures, no photographs, but only a brick tomb, placed among so many others. The last vestige of the countess, like her, is a historically forgotten monument, amidst so many others in the São Francisco Xavier cemetery.

It seems that the tomb of the Countess of Belmonte, in block 18, number 699, reflects a characteristic that she, despite always being close to power, may have learned to preserve: discretion. According to Albuquerque, Mariana Carlota de Verna was a woman:

Discreet, without public projection, as dissimilar in this, as in other aspects – but of the same strong willed spirit – to the noisy man of state, who came, in a hard-fought, unequal and difficult contest, to dispute her authority in the salons of São Cristóvão and to inflict on her a preponderant influence, in the court and in the mood of the emperor-child, the risks of violent competition, The Countess of Belmonte, the venerable and haughty winner of the slaughtered “colossus”, needs to be better known and emerge from the iniquitous shadows in which her virtuous and memorable existence was plunged (ALBUQUERQUE, 1946, p. 183).

Discreet or not, her participation in the political events, that ravaged the 19th century in Brazil until her death in 1855, makes her an eyewitness to a good part of the country’s history, whose memory has been preserved only in a personal family archive, because her life and her story have been silenced like that of so many other women of her time.

Notas

1Maid was the nomenclature used in the 19th century, among noble families, to designate the preceptor hired to be responsible for the education of the children of the house, boys or girls, “[...] who sometimes received joint lessons” (VASCONCELOS, 2005, p. 54).

2Her baptismal name was Mariana Carlota de Verna, having added Magalhães Coutinho after her marriage to Joaquim José de Magalhães Coutinho. In this article, we will call her by her baptismal name, referring to her married surname only when it appears in the original document researched.

3German, born in the city of Kassel, before he was admitted to the Portuguese army his name was Ernest Friedrich Von Verna (ARQUIVO PESSOAL DE LCA – LCA’s PERSONAL FILE).

4Their children were Maria Ernestina de Verna, Ana Frederica de Verna, Mariana Carlota de Verna, and José Frederico de Verna.

5Transcription of an excerpt from the Livro de Baptizados do anno de 1776 a 1782 da freguesia de S. Salvador de Elvas, folio 23 (Book of Baptisms from the year 1776 to 1782 of the parish of S. Salvador de Elvas, folio 23), which belongs to Arquivo Pessoal de LCA (LCA’s Personal Archive).

6Livro de Baptizados do anno de 1776 a 1782 da Frega de S. Salvador de Elvas, folhas 72v e 73 e 73v (Baptism Book for the year 1776 to 1782 of the parish of S. Salvador de Elvas, pages 72v and 73 and 73v).

7Page 124 of Book 3 of marriage registries of the parish of Lapa, council and district of Lisbon, incorporated to the Archive of Parochial Records. (ARQUIVO PESSOAL DE LCA – LCA'S PERSONAL ARCHIVE).

13Marquise of Santos was the title given to Domitila de Castro Canto e Melo by d. Pedro I, in 1826. She died on November 3, 1867 (VASCONCELOS; REZZUTTI, 2018).

REFERENCES

A MEMORAVEL Moxinifada do dia 2, a que os Ministros deram o nome de despaxos de graças. O Republico, Rio de Janeiro, 22 dez. 1854. [ Links ]

A OPPOSIÇÃO e a Corôa. Diário do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 14 jul. 1847. [ Links ]

ABREU, Maria; TOGNOLO, William. Dou-lhe uma, dou-lhe duas e dou-lhe três. Vendido! – um estudo sobre anúncios de leilões de livros no jornal Correio Mercantil (1848-1868). Signótica, Goiânia, v. 27, n. 1, p. 199-220, jan./jun. 2015. [ Links ]

ALBUQUERQUE, Manoel Ignacio Cavalcanti de. A propósito da condessa de Belmonte. Anuário do Museu Imperial, Petrópolis, v. 7, p. 177-189, 1946. [ Links ]

ANTUNES, Vinícius Volcof. Aspectos da modernização carioca a partir do Almanak Laemmert (1902-1906). Programa de Residência em Pesquisa na Biblioteca Nacional, out. 2015. Disponível em: https://www.bn.gov.br/sites/defaut/files/documentos/producao/pesquisa/2015/aspectos-modernizacao-carioca-partir-almanak-laemmert-1902.pdf. Acesso em: 22 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

CALMON, Pedro. O rei filósofo: a vida de D. Pedro II. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional, 1938. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, José Murilo de. D. Pedro II. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2007. [ Links ]

CLAUDIO, Juliana. Discurso em deslocamento: a tradução nas páginas do Diário do Rio de Janeiro no Segundo Reinado. 2016. Dissertação (Mestrado em Estudos da Tradução) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos da Tradução, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2016. [ Links ]

CRHONICA DIARIA. Diário do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 18 out. 1855. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Gilmara Rodrigues da. De dama da Corte à Condessa de Belmonte: a primeira mestra de D. Pedro II (1808-1855). 2021. 178 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. 2021. [ Links ]

CUNHA, Maria Teresa Santos. (Des)arquivar: arquivos pessoais e ego-documentos no tempo presente, São Paulo: Florianópolis: Rafael Copetti Editor, 2019. [ Links ]

DONEGÁ, Ana Laura. Folhinha e Almanaque Laemmert: pequenos formatos e altas tiragens nas publicações da tipografia universal. Revista Seta, Campinas, v. 6, 2012. [ Links ]

FREITAS, Sebastião Costa Teixeira de. D. Pedro II. São Paulo: Editora Três, 2001. (v. 12). [ Links ]

GRAHAM, Maria. Diário de uma viagem ao Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Itatiaia; São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 1990. [ Links ]

LIMA, Edna Lucia Oliveira da Cunha. Fundidora de Tipo do Século XIX Anunciantes no Almanak Laemmert. Relatório de pesquisa. Biblioteca Nacional, dez. 2006. Disponível em: https://www.bn.gov.br/producao-intelectual/documentos/fundidoras-tipo-seculo-xix-anunciantes-almanack. Acesso em: 9 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

LUCA, Tania Regina de. Fontes impressas. História dos, nos e por meio dos periódicos. In: PINSKY, Carla Bassanezí (org.). Fontes históricas. São Paulo: Contexto, 2011. [ Links ]

LYRA, Heitor. História de Dom Pedro II: ascenção 1825-1870. Companhia Editora Nacional, 1977. (v. 1º). [ Links ]

MAIA, José Antônio da Silva. Apontamentos de Legislação para uso dos procuradores da Coroa e Fazenda Nacional. Anuário do Museu Imperial, Petrópolis, v. 1, 1940. [ Links ]

MARIZ, Vasco. Retratos do Império: os Orléans, os Saxe-Coburgo e outras personalidades da época. Rio de Janeiro: Topbooks, 2016. [ Links ]

MEIRELLES, Juliana Gesuelli. A família real no Brasil: política e cotidiano (1808-1821). São Bernardo do Campo: Editora UFABC, 2015 (online). [ Links ]

NORTON, Luís. A Corte de Portugal no Brasil: notas, alguns documentos diplomáticos e cartas da imperatriz. 3. ed. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional, 2008. [ Links ]

PERROT, Michelle. As mulheres ou os silêncios da história. Bauru: EDUSC, 2005. [ Links ]

RAFFARD, Henri. Apontamentos acerca das pessoas e cousas do Brasil. Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico Brasileiro, Rio de Janeiro, 1899 (Tomo LXI). [ Links ]

RANGEL, Alberto. A educação do príncipe. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Agir Editora, 1945. [ Links ]

REZZUTTI, Paulo. D. Leopoldina: a história não contada: a mulher que arquitetou a Independência do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: LeYa, 2017b. [ Links ]

REZZUTTI, Paulo. Pedro II: o último imperador do Novo Mundo revelado por cartas e documentos inéditos. São Paulo: LeYa, 2019a. [ Links ]

RIO DE JANEIRO. Diario Novo, Recife, 23 dez. 1846. [ Links ]

SCHWARCZ, Lilia Moritz. As barbas do imperador: D. Pedro II, um monarca nos trópicos. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1998. [ Links ]

SETÚBAL, Paulo. Ensaios históricos. 10. ed. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional, 1993. [ Links ]

VASCONCELOS, Maria Celi Chaves. A casa e os seus mestres: a educação no Brasil de Oitocentos. Rio de Janeiro: Gryphus, 2005. [ Links ]

VASCONCELOS, Maria Celi Chaves; REZZUTTI, Paulo Marcelo. A marquesa de Santos e o gosto pelo poder: de “favorita” à militante liberal. Revista Estudos Feministas. Florianópolis v. 26, n. 2, p. 1-15, 2018. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1806-9584-2018v26n248809. Acesso em: 17 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

Received: March 23, 2022; Accepted: May 25, 2022

text in

text in