Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Educação em Questão

versión impresa ISSN 0102-7735versión On-line ISSN 1981-1802

Rev. Educ. Questão vol.61 no.69 Natal jul./sept 2023 Epub 19-Dic-2023

https://doi.org/10.21680/1981-1802.2023v61n69id33196

Article

Between looking and reading: the photographic image present in children’s literature books

2Universidade Federal de Lavras (Brasil)

This text considers the image in children's literature books are texts capable of leading the young reader to a movement of dialogue and production of meanings. Given this, this article aims to analyze three different children's literature books that bring photography as art that composes the illustration, in order to reflect on the dimensions of narratives, aesthetic and literary present in such books and possibilities of working with illustrated narratives with the photography in educational practices. Opted for descriptive research, with a qualitative approach, based on the analysis of three children's books that bring photography as focus of illustration. As theoretical basis, the research was based on the studies of Sontag and Flusser on photography, Ramos on children's literature and Santaella on reading images. The study pointed out that photography associated with children's literature sharpens the eye, instigates the reading of images and favors the involvement of small readers.

Keywords: Photographic image; Children's literature; Visual literacy; Visual education

Este texto considera que a imagem presente nos livros de literatura infantil são textos capazes de conduzir o pequeno leitor a um movimento de diálogo e produção de sentidos. Objetiva analisar três diferentes obras da literatura infantil que trazem a fotografia como arte que compõe a ilustração, de modo a refletir sobre as dimensões das narrativas, estéticas e literárias presentes em tais obras e possibilidades do trabalho com livros ilustrados a partir da imagem técnica nas práticas educativas. Optou-se pela pesquisa descritiva, de abordagem qualitativa, a partir da análise de três obras da literatura infantil que trazem a fotografia como foco de ilustração. Com base nos estudos de Sontag e Flusser sobre fotografia, de Ramos sobre literatura infantil e Santaella sobre leitura de imagens, foi possível apontar que a fotografia associada à literatura infantil aguça o olhar, instiga à leitura de imagens e favorece o envolvimento dos pequenos leitores.

Palavras-chave: Imagem fotográfica; Literatura infantil; Letramento visual; Educação visual

Este texto considera que la imagen presente en los libros de literatura infantil son textos capaces de conducir al pequeño lector a un movimiento de diálogo y producción de significados. O artículo pretende analizar tres obras diferentes de literatura infantil que acercan la fotografía como arte que compone la ilustración, con el fin de reflexionar sobre las dimensiones narrativas, estéticas y literarias presentes en tales obras y posibilidades de trabajar con libros ilustrados desde la imagen técnica en las prácticas educativas. Optó por una investigación descriptiva, con un enfoque cualitativo, basada en el análisis de tres obras de literatura infantil que traen la fotografía como foco de la ilustración. Con base teórica en los estudios de Sontag y Flusser sobre fotografía, Ramos sobre literatura infantil y Santaella sobre lectura de imágenes, fue posible señalar que la fotografía asociada a la literatura infantil agudiza el ojo, instiga la lectura de imágenes y favorece la participación de los pequeños lectores.

Palabras clave: Imagen fotográfica; Literatura infantil; Alfabetización visual; Educación visual

Introduction

In this text, we bring as a centrality a reflection on photography as text. For this, we start from the perspective of the image as a visual text, as it consists of illustrated and sequenced narratives, it promotes the reading and understanding of its features and other elements that compose it. Photography allows the recording of moments, situations, people, objects, natural scenarios, in short, everything that the eye can capture, whether for remembrance agency, for documentary record, or as a form of identification or even entertainment, as different ways of attributing to the photographic image a historical, social and cultural character.

Considering that photographs record events and that they confer importance and immortality to what has already happened, Sontag (2004) shows us that such images are artifacts, since they represent pieces of value of the universe that surrounds us, they are relics found, they are fantasy and at the same time information. Whoever collects photos, consequently, collects the world, after all, to honor a photographic image is to enjoy art and simultaneously be impacted by the evidence of reality.

In addition to the perception of photography as a record, Manguel (2001, p. 29) points out that the image can be perceived as a work of art, considering that it is used as a "[...] an artifice to communicate ideas, sensations, a vast poetry."

In this aspect, Flusser (2000) explains that images are surfaces with meanings, which encourages us to consider that the image present in children's literature books can be perceived as texts capable of leading the young reader to a movement of dialogue and production of meanings.

Photographic art allows for a multiplicity of interpretations, it allows the reader to see the image beyond the frames. For Santaella (2012), photography represents a testimony of reality because it evidences the undeniable presence of the object then photographed, a particularity that attracts and brings the attention of readers, including children.

By thinking that children's books can be loaded with representations, because in addition to "[…] a material support for the text, the book, with the content it carries and with the materiality that characterizes it, represents a form of expressiveness and production of meanings […]" (Goulart, 2016, p.80), which mobilizes actions, relationships and interactions in a dialogical way.

Therefore, this article aims to analyze three different works of children's literature that bring photography as an artifact of illustration, in order to reflect on the dimensions of the narratives, aesthetics and literature present in such works and the possibilities of working with illustrated books from the technical image in educational practices.

For this, we opted for a descriptive research, with a qualitative approach, based on the analysis of three different works that bring photography as the focus of illustration. As a theoretical basis, the research is based on the studies of Flusser and Sontag on photography, Ramos and Santaella on image reading, among other authors who discuss the themes.

For a better organization of the proposed discussion, this article is divided into three sections: first, we present a discussion about the practice of reading images and the differentiation between seeing, looking and apprehending the photographic image. Then, we discuss the relationship between the potentiality of the image as a resource for the imagination and, finally, we explore the works in question, through a reflexive analysis of each one of them.

Reading images: between seeing, looking and apprehending the photographic image

Because we consider that the image is characterized as a visual text, which informs and communicates ideas, we can question what is meant by text? To advance in the discussion, we look to Belmiro (2014, p. 321) who, based on linguistic theories, defines text "[...] as a production, whether verbal, sound, gestural, imagery, in any situation of human communication, structured with coherence and cohesion".

By bringing the image as visual text, we understand that it is possible to narrate stories from the act of looking, observing and examining landscapes. Exercising this practice with freedom allows the reader, no matter how young, it is possible to reconstruct memories and associate them with what is being seen, in this way the ability to report in the manner of the child who is being seen is incorporated and, in this sense, Ramos (2013, p. 110) explains "[...] each one will construct the story based on their emotional contents and intellectual repertoire [...]" and she adds:

Seeing and describing scenarios are ways of selecting what impresses and discarding what doesn't make sense. To wrap up the words, but to be able to express what is seen, what is lived and what is imagined helps to elaborate a discourse about reality, to create a way of speaking and thinking that is one's own when one is a child (Ramos, 2013, p. 48).

Therefore, we live in the digital age, surrounded by technology at the reach of our hands and eyes: in advertisements, on television, on cell phones, on the streets, in stores, in traffic, in the restaurant or in the waiting room of an office, images embrace us, block our eyes, wherever we turn, there they are, drawings, paintings, photographs, printed or moving. And for this reason Queirós (2012, p. 94) admits that: "[...] Being silent has become impossible. Perhaps they have discovered that silence is dangerous because it allows us to engage in the deepest dialogue: when our real-self talks with our ideal-self. It is by populating silence that we reconstruct what has been given to us".

The photographic image as text implies a discursive act, as Bakhtin and Volochínov (2012, p. 127) confirm, if a book can be considered "printed speech act", in the same way, we refer to the image as an act of silent speech, acting as visual statements, full of meanings. Silence represents the responsive action provoked by the image.

By populating silence with what is said in a different way, with the thinking of relationships built or reconstructed from the visible, from what was perceived or read, from what had been experienced, we understand that the image can be understood as part of our human formation. Therefore, we can ask: how have educational institutions inserted the text image, as a power of the reader's critical and reflective formation about himself and the world? According to Azevedo (2002, p. 19), most schools are unaware "[...] solemnly the importance, the peculiarities and the possibilities of the knowledge transmitted through images […]" and denounces the fact that Brazilian society despises the act of seeing as a source of knowledge and adds:

[…] we do not have the practice of looking at an artistic work for long minutes, of appreciating it, studying its composition, relating it to the historical moment, inventing ways of seeing it (Azevedo, 2002, p. 19).

Based on the studies of Ramos (2013), we realized that we were not encouraged to practice the act of looking, nor were we encouraged to describe images and narrate based on images with the intention of understanding them. For the author, in schools art is despised, considered a discipline of little importance, so we lack theoretical tools that allow us to unravel an illustration, a painting, a sculpture or a photograph, to explore what we see while contemplating or rejecting an image from the art of looking.

In this way, we highlight the fact that seeing does not mean reading, looking does not mean decoding, much less interpreting. We see images, but we don't understand them, we don't pay them the attention they deserve. Based on Flusser (2000), the subject looks at an image and does not decode it, but absorbs what he sees, assimilates that information not understood and reproduces it back in the real world. Santaella (2012) confirms that the image reader is not aware of the real message contained in the visual texts that, even without understanding and deciphering what he sees, absorbs this content, due to the naivety with which the reader deals with such images loaded with meanings.

In view of this, we can affirm that "seeing is an act of knowledge", understanding that looking consists of perceiving, observing, examining and reflecting on what is being seen, to the extent that correlating and evaluating allows the image reader to think and imagine based on their own experiences, knowledge and visions of the world (Ramos, 2013, p. 34).

For Manguel (2001), what we read in an image varies according to the person we are and what we have learned prior to that moment. In this way, the child identifies with the images of the books when he recognizes what he sees and, based on the references of his own world, relates the figures to his reality, to his daily life and the environments he frequents.

Thus, based on Manguel (2001, p. 27), such identification between reader and image occurs because "[...] We can only see things whose image is identifiable, just like reading in a language we know". With this, we understand that the image, which is manifested by art, takes us back to some memory, activates the memory of the reader, who sees, looks and remembers, because the image invites the observer to think. For Manguel (2001, p. 273), in the specific case of the image, as an authentic monument that shows itself as both memory and reflection, the author explains that it carries the message: "remember and think".

In this sense, it can be seen that the photographic image, being an art, invites us to reflect, to think, awakens reactions, takes us to a certain moment already lived, to a certain place or person, connects us to memories, summons us to a reflection. Photography as art represents the union between creativity and sensitivity to the particularities of visual narrative, that is, to language, metalanguage, visual arts, or graphic arts in dialogue with the book object, the reader is guided in a trajectory of seeing and examining, entering the process of reading images (Castanha, 2008).

The photographic image as memory represents something that has passed, something that has happened and has been recorded and proven in the image, "[...] Photography does not speak (necessarily) of what is no more, but only and certainly of what has been [...]” (Barthes, 1984, p. 127). Therefore, it is understood that what is represented there is not the real object, but a copy, an approximate representation of that object, "[...] it is the absent thing reconstituted in memory [...]", analyzes Dalcin (2013, p. 94).

In the case of reading a narrative composed solely of images, the reader, based on imagination, is able to read and create what happens between the scenes of one page and another. This is because it is part of the continuous sequence of events, of clearly defined actions that represent and maintain the narrative flow.

In a work of visual texts, this continuous process of movement is manifested by the images and the way they are organized within the literary work, because according to Dalcin (2012, p. 14), they act "[...] orchestrating, together with the author, this whole process, the editor is the first reader to look for marks in the creation that really bring the space of time between the scenes [...]".

Children identify what they see, so such images tend to help the young reader connect with the work, which can be read by both a child and an adult. According to Hunt (2010, p. 237), young children tend to distinguish illustrated objects "[…] regardless of an object's position in space, children tend to recognize them to the point of easily being able to name them."

We realized that the act of looking at and observing colors and scenery can awaken children's fascination with the images and result in their involvement in the work. According to Benjamin (2009, p. 69), the process of involvement through illustrations occurs in the following way: "[...] It is not the things that leap from the pages towards the child who imagines them - the child himself penetrates things during contemplation, like a cloud that is impregnated with the colorful splendor of this pictorial world." And in this direction, the author adds once again the effect of the magic of illustrative colors on children's eyes: "[...] in this permeable world, adorned with colors, [...] the child is received as a participant [...]", the child sees himself as an integral part of the book because he is enchanted by the illustrations and identifies with what is shown (Benjamin, 2009, p. 70).

In addition, the colorful stimulus presented to the child's eyes encourages the practice of orality, refers to the "[...] exhaustive exhortation to the description contained in such images", because "it awakens the word in the child [...], in this way "[...] the child penetrates these images with creative words [...]", according to Benjamin (2009, p. 70). This can be considered one of the factors that explain the possibility of expanding the vocabulary of the young reader. In view of these considerations, we can affirm that the illustrations bring the child closer, connect the child to the book object as well as collaborate for their sensory evolution.

In this sense, the child as a spectator who watches a show, who reads a scene on a page, or even on a stage, notices the details, the colors, and this child questions, imagines and invents. And from the moment one understands the image observed as a stage, the impact of that figure on the eyes of the reader is highlighted, who sees, understands, questions, remembers, feels and, in turn, transforms himself after such an experience.

Ribeiro (2008, p. 124) explains this impact of the illustrative image on the reader as follows: "[...] we observe, we understand, we agree or disagree with its form, we touch, we are touched, or we look away; however [...] at the end of the book, when the image impregnated on the retina disappears, "[...] we are no longer the same as before [...], because [...] we have been initiated".

For Ramos (2013), the observer is the one who, based on his dedicated concentration and repetitions of this act, feels the need to create ways to see better and better. We read a photographic image, just as if we read a narrative, so it can be understood as a text, because by recording a moment, a fact, a scene, a situation, it provokes feelings, ideas, reconstructs memories, reactions, which, according to Manguel (2001), is capable of narrating and informing, as well as sensitizing and creating dialogue with the reader.

The act of looking, examining, perceiving, observing, allows the reader to attribute to each image the expansion of its limits, beyond its frame, as detailed by Ramos (2013). For Flusser (2000, p. 9), the interpretative and dialogical potential of images is characterized as "[...] mediations between the world and human beings [...]", in the words of Manguel (2001, p. 286): "To become an image that allows us an illuminating reading, a work of art must force us into a compromise, a confrontation, it must offer an epiphany, or at least a place to dialogue." In this way, the photographic image becomes a discursive space, creating a dialogical relationship between the reader and the image.

However, we know that at the beginning of the history of photography, people did not look at photographic images for a long time, perhaps out of fear or apprehension, there was the impression that the photo could look back at the observer, "[...] the sharpness of these physiognomies was frightening […]", points out Benjamin (1994, p. 95). The same phenomenon happened with the people who were going to be photographed, they did not look directly at the camera, they acted timidly, and possibly because of such behaviors the embarrassed posture, characterized by avoiding the gaze, became a trend after the heyday of photography, in the nineteenth century.

However, it is precisely this look that is necessary in the process of apprehension of the image. Reading, examining and interpreting requires the reader to think, to feel, it means learning to read images, to decode them, it is the necessary act for the reader to become visually literate. From this perspective, Santaella (2012, p. 74) names the interpretative effect of a photographic image as "reading the photograph".

Just seeing a photograph quickly is not enough for the development of your reading, a superficial look makes it possible to understand it superficially, because it does not allow a deeper understanding, not being enough to really understand it. To read an image, it is not enough just to take a brief look, it is necessary to examine it carefully and realize that its meaning is on its surface, in its traces and lines, which must be followed carefully with the eyes. In order to deepen the meaning of the image, we must allow the gaze to examine, contemplate, navigate the surface by feeling and following the paths of the image (Flusser, 2000).

The reading of a photograph consists of looking at it carefully, aware that it represents a visual language, "[...] it means turning the gaze into a kind of machine for feeling and knowing [...]", adds Santaella (2012, p. 80). Thus, contemplation is necessary, so that the reading takes place in search of a trajectory, following the course of the lines, lights and shadows offered by the photograph to the eyes of the observer, "[...] because the immanent meaning of the subjects and subjects photographed is inseparable from the singular arrangement that the photographer chose to present" (Santaella, 2012, p. 80).

By learning to read images, the subject becomes visually literate and from sensitivity becomes able to develop the necessary skills to observe and know the content of what he sees, in this way reading a photograph implies discovering how the content present there is presented, it means acquiring the corresponding knowledge. But how does this process take place? Santaella organizes this movement on three levels as follows:

There are at least 3 levels of seizure of a photo. First of all, any photo produces in us some kind of feeling, sometimes imperceptible, sometimes very intense. However, notwithstanding the importance of feelings, they correspond only to the first level of apprehension of a photo. On a second level, we see a photo, that is, we identify its subject, what is photographed in it. Thus, when we look at a photo, we recognize traces, we identify what has been photographed. When this identification is not immediate, we look for clues and play with guesswork and guesswork about the place and the situation that appear there. But it is only at the third level of apprehension that the difference between seeing and reading photos emerges (Santaella, 2012, p. 79).

Therefore, we realize that even with all the skill of the photographer, the observer feels the need to look for a "[...] a small spark of chance [...]" that awakens him, declares Benjamin (1994, p. 94). For the author of the image, to photograph is to extend and prolong the gaze beyond the record, to capture the sparks of the moment. In this sense, we found that every photograph awakens in some way a type of feeling in its reader, which can cause both the effect of recognition and estrangement in those who contemplate it (Ramos, 2013).

This is due to the fact that the "[...] photographs impress us, move us, bother us, in short, imprint different feelings on our minds [...]" (Mauad, 1996, p. 5). In the same perspective, Barthes (1984) points out that images provoke varied feelings, sometimes good, sometimes not so much, and can cause indifference or even aversion, irritation, sympathy and connection.

For Benjamin (2012, p. 18) the feeling of disturbance caused by the photographic image directs the reader to seek a certain way to understand it, because this image requires a specific type of reception, "[...] no longer being adequate for an uncompromised contemplation" and Barthes (1984, p. 62) adds: "Photography is subversive, not when it terrifies, disturbs or even stigmatizes, but when it is thoughtful."

The Potential of the Image for the Imagination

By looking, feeling and/or reading an image, we produce meanings, from the first contact with the image, to the moment of apprehension and reading, arriving at its result as a product of a choice, the result of a reflection. By observing the images, the child becomes visually literate, he learns to examine, analyze, develops the sensitivity of the gaze, points out Santaella (2012). Thus, the reading of the images occurs when a story is narrated, such as "[...] it is also the appropriation, invention and production of meanings, [...] because in addition to intellection, it is the engagement of the body, inscription in space and relationship with oneself" (Dalcin, 2012, p. 15).

Seeing, looking, seeing are primary gestures that the subject learns and perfects, but learning to look means going beyond the mechanical gesture of simply seeing, it means leaving aside this physical activity and moving on to the next stage, which through effort and mental exercises, the subject develops the ability to absorb and understand what he observes and examines. Looking, then, becomes a way of perceiving, it begins to incorporate the act of correlating, evaluating and thinking. This more evolved movement of exploring the image allows analyses to take place, fueling creativity and the ability to invent because it triggers not only the physical, but also perceptions and the psychological (Ramos, 2013).

In this way, we understand that imagination represents freedom in a child's life, a space that sensitively opens up to the new and to the possible, even if impossible. According to Girardello (2011, p. 76) it is through imagination that the child satisfies his desire for novelty, "She is in need of the imaginative emotion that lives through play, the stories that culture offers her, the contact with art and nature, and adult mediation: the finger that points, the voice that tells or listens, the daily life that accepts."

We consider that imagination is not a gift or a quantifiable characteristic, but that, however, it has a role of great importance for the development and education of the child, points out Girardello (2011). In this sense, we highlight that fantasy is linked to emotions, intelligence and feelings, therefore, the education of imagination is shown to be an important task in the educational field, and the child's imagination can be educated, such as from looking and listening, because in the same way that the child's logical understanding is worked and developed, Their ability to fantasize and imagine also needs to be nurtured. For the author, the experience provided by the imagination is as relevant as the experiences acquired from logical thinking and, for this reason, it must be taught, fed, cultivated, otherwise it atrophies.

Imagination is cited by Flusser (2000) and declares it as a precondition for the decoding of technical images, defined as surfaces with meanings, or even as a fundamental element in the process of decoding the image, not only in the act of reading, but also in the movement of creation of visual art. For Flusser (2000), imagination represents the ability to capture and subtract surfaces from a certain place and time, as well as project them back into a space and moment, so imagination is shown as a precondition for the production and decoding of images.

In this sense, technique and magic are mixed when photography is capable of highlighting dreams, proving the improbable, highlighting the previously imperceptible, according to Benjamin (1994, p. 95) "[...] the difference between technique and magic is a totally historical variable [...]". The meaning of images is magical and for this reason it is important to consider the magic present in images in order to decode them. The magical power of images lies in their nature and in the dialogical power they possess, including their contradiction to be mediated by their magic (Flusser, 2000).

Magic, fantasy and imagination allow a greater opening for reflection, enabling the reader to exercise a dialogue between what the eyes see and what the mind seeks in memory, as we perceive from Manguel's words:

With the passage of time, we can see more or less things in an image, probe deeper and discover more details, associate and combine other images, lend it words to tell what we see, but in itself, an image exists in the space it occupies, regardless of the time we take to contemplate it (Manguel, 2001, p. 25).

Both a text and an image are capable of conveying content, but "[...] images are received more quickly than texts, they have a higher attention value, and their information remains longer in the brain," explains Santaella (2012, p. 109). Thus, the author adds that images are increasingly used as a source of knowledge transmission, playing a fundamental role in the field of observational sciences, fulfilling an explanatory, cognitive, technical or even magical, symbolic and imaginary function when related to the verbal text.

Text and image are related at all times, whether from the reading of an image or through the visualization of the word read and written. Thus, reading an image does not mean translating it into verbal language, according to Santaella (2012, p. 13), verbal and visual text are distinct and do not replace each other, "[...] they complement each other much more, so that one cannot entirely replace the other". Nikolajeva and Scott (2011, p. 21) go further and state that there is a lack of tools to decode a third text, created by the interaction of verbal and visual information, the so-called "iconotext" defined as "[...] an entity inseparable from word and image, which cooperate to convey a message".

In short, regardless of who decodes the image, it is necessary to read between the lines, that is, to go beyond the dimension of what is presented in front of the gaze, to seek the relations of meanings with the expressions and details that are not highlighted, that are not pronounceable or not visible, as we must also do with literature texts. In this way, we will not run the risk of becoming illiterate of the image, as if it were necessary to add a caption to understand the magic that is in it.

A Look at Photography as Visual Text in Children's Literature Books

In this topic, we present the analysis of three works of children's literature characterized as illustrated books that in common present photography as an integral art of the illustrative image in their narratives. The works are: Hugs there and here, by Sonia Rosa, Colorful Tricks, by Marcelo Xavier, and Contradança, by Roger Mello.

Regarding the classification of picture books, Nikolajeva and Scott (2011) explain that there are four styles of typography, and that we can understand as an illustrated book the works that display text and image, that is, written text and visual text that are equally relevant.

This relationship between the verbal text and the visual text results in valuable proposals, especially in Children's Literature, as well as in a wide variety of cultural productions, as they are languages that intertwine "[...] in life and in art, overcoming the limits with which each one operates […]", points out Belmiro (2014, p. 322) who adds: the reading mediator, should “[...] take advantage of the current format of Children's Literature books to aesthetically explore the visual texts that circulate in children's daily lives".

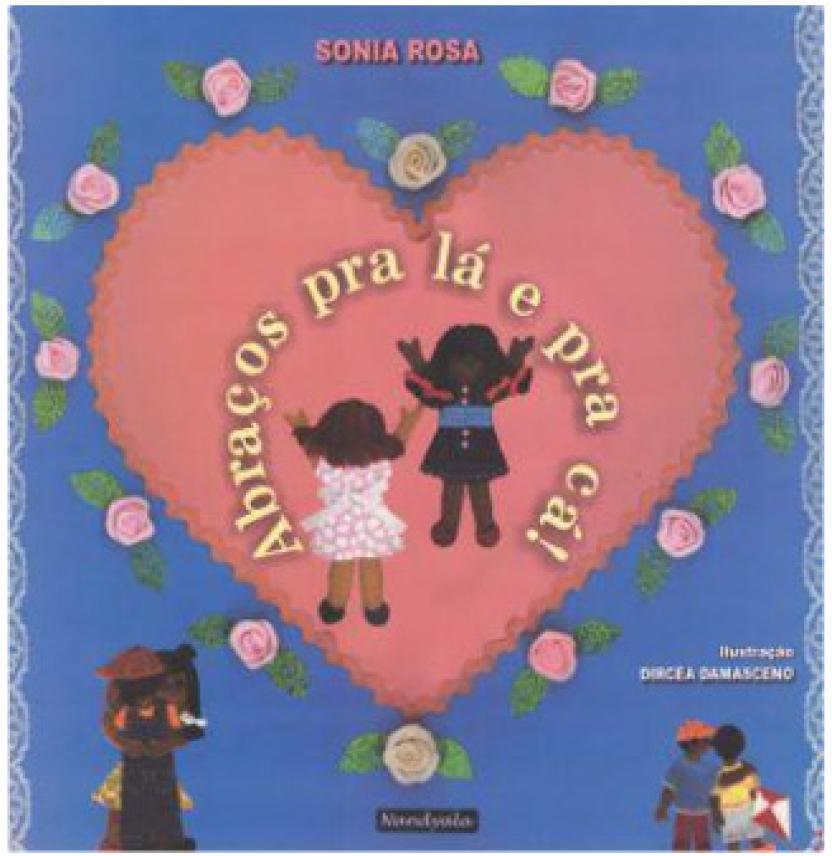

The first picture book under review is entitled Abraços pra lá e pra cá!. It was written by Sonia Rosa1 and illustrated by Dircéa Damasceno2 based on the art of sewing with fabrics, wool, threads, ribbons and buttons, among other artifacts, resulting in the creation of colorful images rich in details, recording characters and scenarios that, after elaboration and structuring, were photographed by João Sales3 and organized in the pages of a printed book.

Image 1 shows us the cover of the work, with a blue background with a pink fabric heart, with small flowers around it. In the center, two girls with arms outstretched in the air and the title of the book. In the left corner of the cover two characters hugging each other and in the right corner a character walks with his arm on the shoulder of another character. Centered at the top we read the name of the writer Sonia Rosa, centered at the bottom we read the name of the publisher Nandyala and on the right at the bottom we read the name of the illustrator Dircéa Damasceno.

Source: https://www.afropolitan.com.br/products/abracos-pra-la-e-pra-ca

Image 1 Front cover of the book Abraços pra lá e pra cá!

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVNSVTOyMSg

Image 2 Page 9 of the book Abraços pra lá e pra cá

The work was published in 2011 and consists of 16 pages illustrated using the same technique. Every page of the narrative consists of an image and a written text. The images are diverse and all created with the use of fabrics, felt, ribbon bows, buttons, threads, lace, wool, strings among other materials. The palpable art of weaving materializes in the pages of a book from the photographic record, which captures the details, the colors and allows the sequential organization of the narrated story.

In this work, the central point of the photographic image is to unite different elements, such as the scenarios sewn in fabrics with patchwork, buttons, ribbon bows, threads and other artifacts present in the sewing. We perceive in the images the presence of different colors and textures, resulting from a variety of materials and weaving techniques.

Photography here plays a fundamental role in the materialization of the palpable, it makes two-dimensional what actually has three dimensions. Sontag (2004) explains that photography constitutes a kind of grammar and what would be the ethics of the act of seeing, as they expand our awareness of what can be seen, emphasizing the fact that we have the right to observe what surrounds us.

It is a story about the importance of a hug, in which the characters experience the relevance of this act of affection so familiar in the daily lives of the characters. The scenarios are diverse, a house, the front of a school, a classroom, the grandmother's house, a garden and a birthday party table. A story of affection, where written text and visual text dialogue with harmony and lightness.

The choice of the theme "hug", an affectionate act known and practiced in our culture, reinforces the bonds between work and reader, after all, literature, in addition to favoring the teaching of writing and reading, has the power to culturally form the reading subject. In this sense, Cosson (2019, p. 27) explains that "[…] reading implies an exchange of meanings not only between the writer and the reader, but also with the society where both are located [...]".

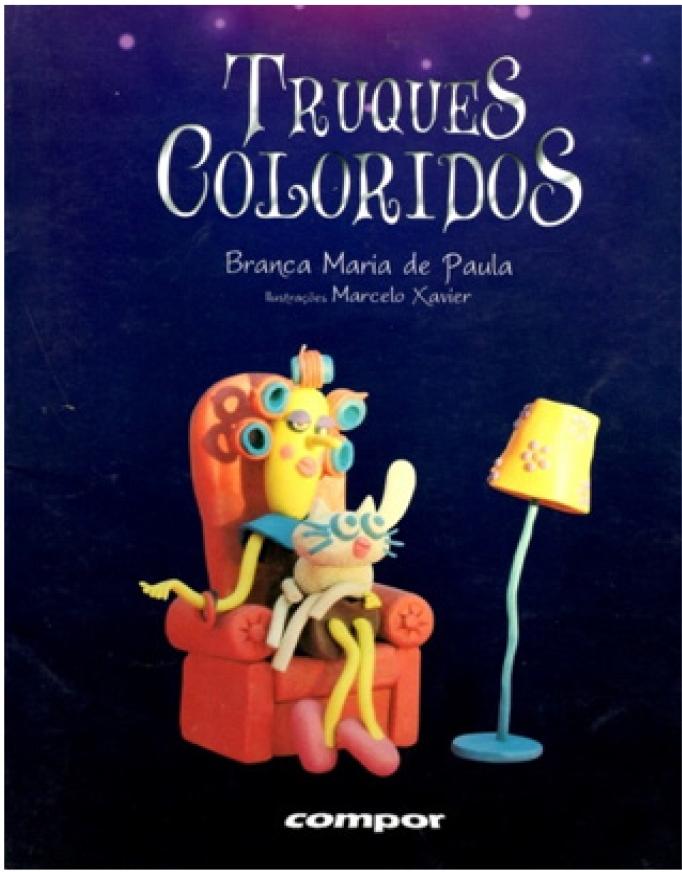

The second work under analysis is called Colorful Tricks, it was written and photographed by Branca Maria de Paula4 and the illustrations of modeling clay were created by the artist Marcelo Xavier5.

We can see in image 3, on the cover of Paula's work, a character sitting in an armchair with her cat on her lap and next to it a lampshade, all made with colored modeling clay. Centered at the top of the image, we see the title of the work and just below the name of the writer and illustrator Marcelo Xavier. Centered at the bottom of the cover is the name of the publisher, Compor.

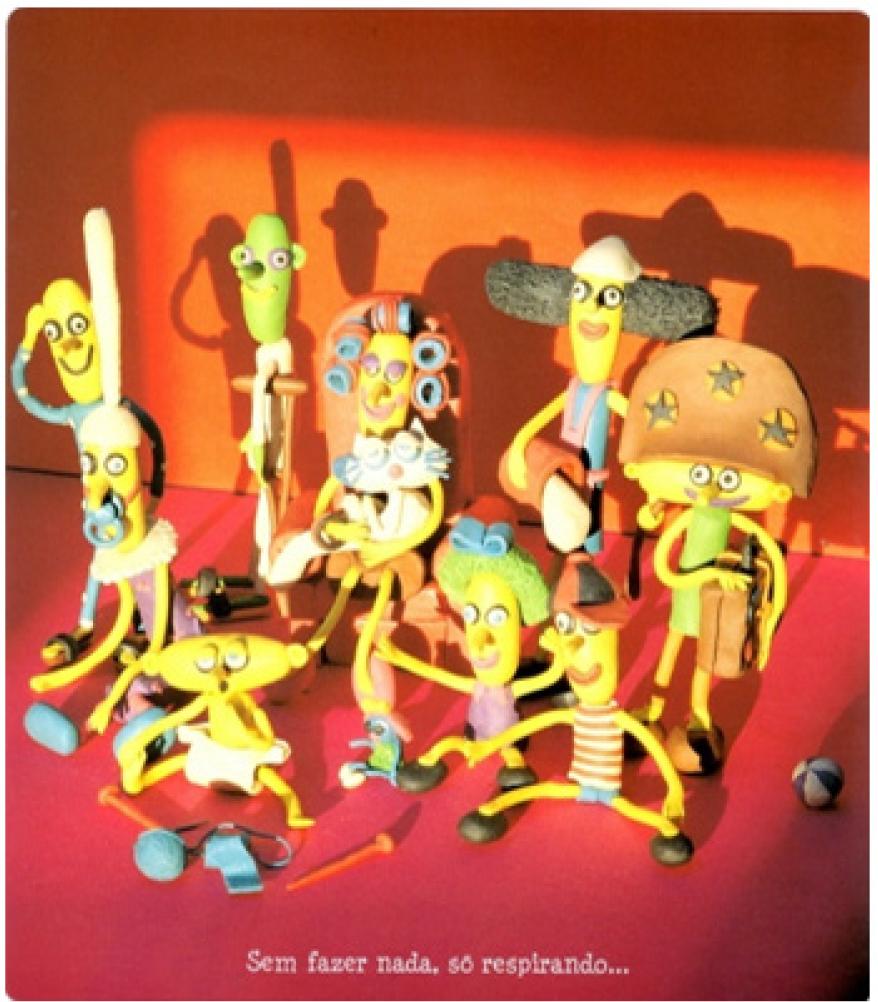

Considering that the photographic images in the printed support, here the book, can present narratives organized in a sequential way, we realize that in the work of Branca de Paula and Xavier, the writer and photographer together with the artist invest a lot of creativity when they vary characters, scenarios, colors and expressions between one page and another, which made his work not only more dynamic and fun, but also created a narrative and artistic set, which favors the reader to stay connected between one scene and another in the story, following and reading sequentially at each page change (Naves, 2019).

Here, in image 4, it can be seen that the central point of the photograph would be related to the positioning of the camera that is placed in the perspective of the reader and also of the television, which is the theme of the story. In this way, it is understood that light that hits the characters head-on is the light from the TV screen that, when turned on, keeps its viewers still "[...] without doing anything, just breathing[...]" as written in the narrative. The photography captures the puppets in their three-dimensionality, the textures, the colors, the positions of the characters, the surrounding structured scenery, and the light.

Based on Sontag (2004, p. 15), the book as a support is shown as a way of organizing and ensuring the longevity of photographic images, which outside the pages of a book or an album, are more fragile, liable to be lost or torn. Thus, the photo, "[...] when reproduced in a book, it loses much less of its essential character than a painting".

Colorful Tricks was first published in 1986 and has 26 pages that tell a story about television. All illustrations were made with modeling clay, the puppets, scenarios, objects, and the finalization of the image was made from the use of a game of lights that represented the luminosity coming from the television screen. The scenes were photographed one by one, resulting in illustrated colored pages accompanied by the written text. We observed that photography made it possible to bring to the two-dimensional pages of the printed book, the three-dimensional art of Play Doh sculptures.

We can say that the choice of malleable, colorful material that is part of the children's playing universe favors the interaction and approximation of the child with the work. According to Ramos (2013, p. 41), the "[...] Children quickly learn the language of images, because they are at a stage of development in which sensations, linked to shapes, colors and textures, are still on the surface, they have not been excessively influenced by rationalization". In this way, we observed that the sculptures, the details, the scenes created from the use of colored clay, favor the dialogue and familiarization of the narrative with the reader because they are evidenced to the child's eyes through the photographic record.

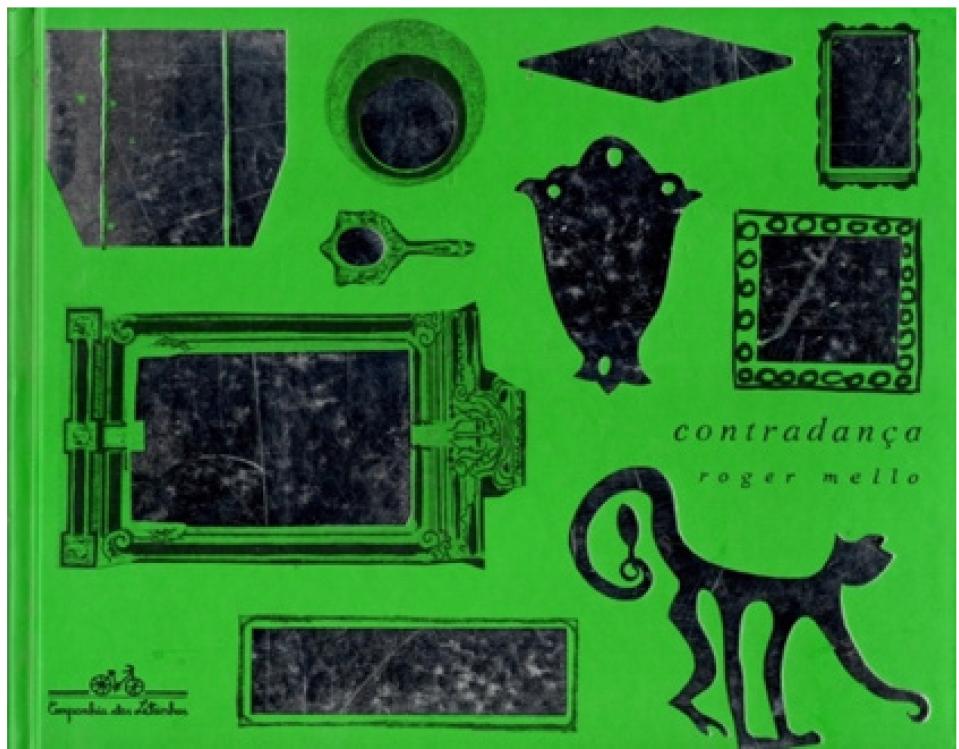

The third and last work analyzed is entitled Contradança, written by Roger Mello6. It is a story illustrated from black and white photographic images. The work does not state who illustrated and photographed the images.

The cover can be seen above, in image 5, which shows us its format, with a green background and ten black and silver images scattered throughout the space. The title of the work and the name of the author can be found on the right side of the image and the name of the publisher, Companhia das Letrinhas, in the footer on the left side of the image.

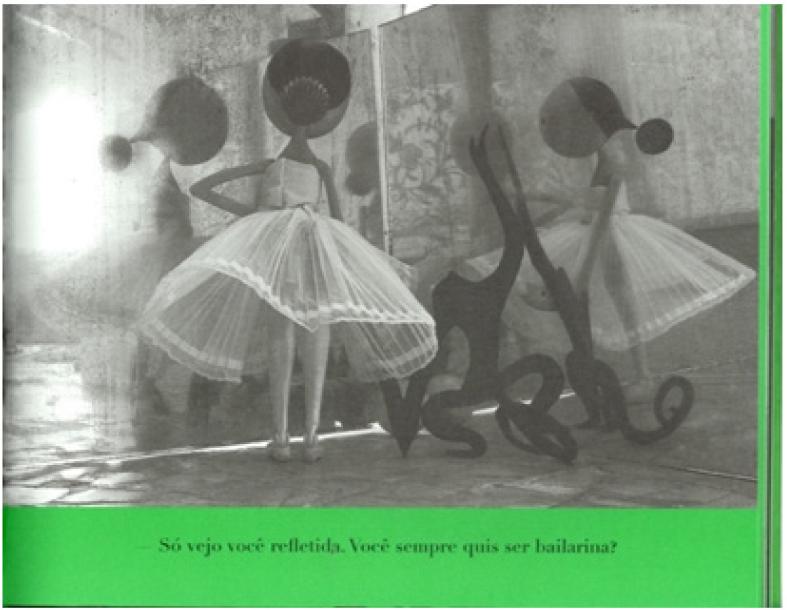

In this work, based on image 6, it can be seen that the central point of the photograph is to ensure the atmosphere of suspense, from the absence of colors, the play of shadows and reflections with mirrors. The positioning chosen to place the character, with the head bowed in front of his own reflection, the choice of angle in which the image is captured, guarantee a melancholic effect that materializes with the light stamped on the background of the image.

The entire work has only three colors: green, white and black, a visual characteristic that resulted in a dramatic or even suspenseful aspect to the story, which in its narrative embraces mystery. Factors such as this, provoked by the literature book, are explained by Cosson (2019, p. 17) as follows: literature has a "[...] major function, to make the world comprehensible by transforming its materiality into words of intensely human colors, odors, flavors and forms [...]".

Published in 2011, the story is organized into 38 pages. The illustrations vary between single pages and double pages, scenarios and real objects. Some images are drawings, others are photographs, but always accompanied by written text. The story narrated in the book is about a girl who talks to her reflection and the many possibilities it shows her to be and to be in the world, conversations that involve the themes of fear and courage.

We can think that the choice of photography guarantees the reader a differentiated experience, offers him contact with other arts that is only possible due to the testimony of the photo, which proves, shows that scene as an incontestable proof that that object was there, it exists, it is real. The characters and fabric scenarios, the story made up of modeling clay, the black and white shadows, all of this exists and has been immortalized by the photographic record, now printed on the pages of books that will circulate and can be observed and read indefinitely, as long as it is necessary to read them.

Conclusion

By prioritizing the analysis of three different works of children's literature that bring photography as an artifact of illustration, we seek to reflect on the dimensions of the narratives, aesthetics and literature present in such works and the possibilities of working with illustrated books from the technical image in educational practices. The study pointed out that the choice of the photographic image as a component of illustrative art in the works of children's literature favors the involvement of the young reader with the narrative and, above all, with his imagination. The combination of the arts on the pages of the printed book can promote the approximation between the reader and the work.

If materiality has repercussions in different ways on the relationship between reader, book and text (Goulart, 2011, 2014, 2016), photography, by composing the illustrative materiality of the work, provokes understandings and other ways of interaction between the reader and the text. It can guarantee and highlight details, the variety of materials, textures and colors, the choice of objects selected for the creation of narratives and in a documentary way, photography ensures the space of the art of weaving, the art of modeling and the art of photographing.

Therefore, we prove that the technical image in the book support offers the space and time that the reader needs to see, examine, look and read the image, understand what it carries, follow its features, identify its elements and its motives. The photograph showed the strength of the combination between fantasy and reality, presented the reader with a scenario of colorful playdough, characters of fabrics, lace and buttons, and even a story with photos of shadows and mirrors.

We understand that photography allows multiple possibilities of work, and that it has been definitively incorporated into our culture, and that its use associated with children's literature has only come to enrich practices and enhance other visual arts, bringing reading and art closer and closer to its readers, since childhood, inside and outside school spaces. After all, we live surrounded by images.

Notes

1Sonia Rosa is from Rio de Janeiro, a teacher and storyteller. Writer's website: www.soniarosa.net.

2Dircéia Damasceno is a retired teacher and storyteller. She enjoys telling stories, writing and making dolls.

4Branca Maria de Paula is from the city of Aimorés, Minas Gerais, writer, photographer, screenwriter and has a degree in Philosophy from UFMG. She is part of Micros-Beagá collection at the Publisher Pangeia.

5Marcelo Xavier is a self-taught artist, born in the city of Ipanema, today he lives in Belo Horizonte MG. Graduated in Advertising from PUC Minas, he has a total of 21 published books and several awards.

6Roger Mello is an illustrator and writer from Brasilia, born in 1965, he has received the Jabuti award nine times.

REFERENCES

AZEVEDO, Ricardo. Imagens iluminando livros. 2002. Disponível em: www.ricardoazevedo.com.br. Acesso em: 5 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

BAKHTIN, Mikhail; VOLOCHÍNO, Valentin. Marxismo e filosofia da linguagem: problemas fundamentais do método sociológico na Ciência da Linguagem. Tradução Michel Lahud e Yara Frateschi Vieira. São Paulo: Hucitec Editora, 2012. [ Links ]

BARTHES, Roland. A câmara clara: nota sobre a fotografia. Tradução Júlio Castañon Guimarães. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1984. [ Links ]

BELMIRO, Celia Abicalil. Textos visuais. In: FRADE, Isabel. Cristina Alves da Silva; VAL, Maria da Graça Costa; BREGUNCI, Maria das Graças de Castro (org.). Glossário ceale: termos de alfabetização, leitura e escrita para educadores. Belo Horizonte: UFMG/Faculdade de Educação, 2014. [ Links ]

BENJAMIN, Walter. Pequena história da fotografia. In: BENJAMIN, Walter. Magia e técnica, arte e política: ensaios sobre literatura e história da cultura. 7. ed. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1994. [ Links ]

BENJAMIN, Walter. Reflexões sobre a criança, o brinquedo e a educação. Tradução Marcus Vinicius Mazzari. 2. ed. São Paulo: Duas Cidades, 2009. [ Links ]

BENJAMIN, Walter. Benjamin e a obra de arte: técnica, imagem, percepção. Tradução Marijane Lisboa e Vera Ribeiro. Rio de Janeiro, Contraponto, 2012. [ Links ]

CASTANHA, Marilda. A linguagem visual no livro sem texto. In: OLIVEIRA, Ieda de (org.). O que é qualidade em ilustração no livro infantil e juvenil: com a palavra o ilustrador. São Paulo: Dcl, 2008. [ Links ]

COSSON, Rildo. Letramento literário: teoria e prática. 2. ed. São Paulo: Contexto, 2012. [ Links ]

DALCIN, Andreia. Rodrigues. A leitura do livro ilustrado e livro imagem: da criação ao leitor e suas relações entre texto, imagem e suporte. In: SEMINÁRIO DE PESQUISA EM EDUCAÇÃO DA ANPEd SUL, 9, Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul, 2012. [ Links ]

DALCIN, Andreia Rodrigues. Um escritor e ilustrador (Odilon Moraes), uma editora (Cosac Naify): criação e fabricação de livros de literatura infantil. 2013. 236 f. Mestrado (Dissertação de Mestrado) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 2013. [ Links ]

FLUSSER, Vilem. Towards a philosophy of photography. Great Britain: Reaktionbooks, 2000. [ Links ]

GIRARDELLO, Gilka. Imaginação: arte e ciência na infância. Pro-Posições, Campinas, v. 22, n. 2, p. 75-92, maio/ago. 2011. [ Links ]

GOULART, Ilsa Vieira. O livro nas memórias de leitura. Revista Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 32, n. 115, p. 567-582, abr./jun. 2011. [ Links ]

GOUULART, Ilsa Vieira. Entre a materialidade do livro e a interatividade do leitor: práticas de leitura. Revista digital de biblioteconomia e ciência da informação. Campinas, v. 12, n. 2, p. 5-19, maio/ago. 2014. [ Links ]

GOULART, Ilsa Vieira. A compreensão e conceituação de livro num jogo de representações. Revista Leitura: Teoria & Prática, Campinas, São Paulo, v. 34, n. 67, p. 69-82, 2016. [ Links ]

HUNT, Peter. Crítica, teoria e literatura infantil. Tradução Cid Knipel. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2010. [ Links ]

MANGUEL, Alberto. Lendo Imagens: uma história de amor e ódio. São Paulo: Companhia de Letras, 2001. [ Links ]

MELLO, Roger. Contradança. São Paulo: Companhia das Letrinhas, 2011. [ Links ]

NAVES, Ludmila Magalhães. Educação para/do olhar: a dupla representação da ilustração nos livros de imagens de Marcelo Xavier. 2019. 135 f. Dissertação (Mestrado Profissional em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Lavras, 2019. [ Links ]

NIKOLAJEVA, Maria; SCOTT, Carole. Livro ilustrado: Palavras e imagens. Tradução Cid Knipel. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2011. [ Links ]

PAULA, Branca Maria de. Truques coloridos. Belo Horizonte: Compor, 2011. [ Links ]

QUEIRÓS, Bartolomeu Campos de. Ler é deixar o coração no varal. In: QUEIRÓS, Bartolomeu Campos de. Sobre ler, escrever e outros diálogos. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2012. [ Links ]

RAMOS, Graça. As imagens nos livros infantis: caminhos para ler o texto visual. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2013. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, Marcelo. A relação entre o texto e a imagem. In: OLIVEIRA, ILeda de. O que é qualidade em ilustração no livro infantil e juvenil: com a palavras o ilustrador. São Paulo: DCL, 2008. [ Links ]

ROSA, Sonia. Abraços pra lá e pra cá. Belo Horizonte: Nandyala, 2011. [ Links ]

SANTAELLA, Lucia. Leitura de imagens. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 2012. [ Links ]

SONTAG, Susan. Sobre fotografia. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2004. [ Links ]

Received: July 11, 2023; Accepted: November 06, 2023

texto en

texto en