INTRODUCTION

Improving the quality of basic education in Brazil, which refers to preschool, elementary and high school, is a problem that involves several dimensions and is not limited to teachers’ performance in the classroom. Low wages, poor working conditions in public schools and the absence of career development schemes (ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL PELA FORMAÇÃO DOS PROFISSIONAIS DA EDUCAÇÃO - ANFOPE, 2006) are among the aspects that must be considered and which help explain the low attractiveness of the teacher career, as well as the profession’s low social prestige.

On the same subject, Gatti and Barreto (2009) highlight the need for more funds for education, as well as the importance of restoring the culture of teaching as a valuable profession. In addition, the authors point out the quality of initial and continuing teacher education as one of the main factors for the valorization of teaching.

Today in Brazil, initial teacher education for basic education is carried out in: undergraduate licensure programs; pedagogical training programs for unlicensed degree holders; and second licensure programs. All these are offered by Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) (BRASIL, 2015), hence the importance of discussing the role of HEIs in the processes of initial and continuing teacher education for basic education.

Considering that the improvement of basic education in the country represents a relevant issue of collective interest and involves several factors - among which the quality of initial and continuing teacher education (GATTI; BARRETO, 2009) -, addressing the problem requires the government to design and implement articulated policies that can positively interfere with this scenario.

The discussion about the design and implementation of public policies also implies deeper theoretical insights into the field of program evaluation.

Public authorities are expected to implement policies that are effective in achieving their objectives, efficient in the use of economic and managerial resources and able to produce social effects (SECCHI, 2014; JANNUZZI, 2016).

As the society grows mature, it increasingly demands the various government levels to be ethically committed, as well as government accountability for better choices using of public resources. Arretche (2009, p. 37) emphasizes that rigorous, technically well-designed evaluations allow the “exercise of an important democratic right: control over government actions”.

In order to discuss public policies for initial teacher education with the subject of program evaluation, the present study chooses as its object of reflection the Pibid, implemented by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Capes).

Pibid is a program that fosters teacher education and the valorization of teaching, created in 2007 and implemented by Capes’ Board of Basic Teacher Education (DEB) since 2008. The program provides scholarships to undergraduate licensure students to enable their introduction into public primary schools, thus providing a training that combines theory and practice and brings licensure students closer to the school environment. The pedagogical activities developed by the licensure students are guided by a supervisor (school teacher) and an area coordinator (teacher at the licensure program), both of which also receive a grant to develop these activities.

HEIs quickly joined the program in response to Capes’ calls for new projects and the renewal of ongoing ones. Of 3,088 fellows in 2007, the Pibid expanded its coverage to 90,254 grants in 2014. That year, 284 higher education institutions coordinated Pibid projects, involving approximately 6,000 partner schools in the county or state public systems. The number of licensure students and educational institutions involved is significant in the current scenario of educational policies in Brazil, which, according to Gatti, Barreto and André (2011), suggests the need for evaluative research on its results.

PRESENTING THE STUDY

Choosing the Pibid as the focus of this investigation is justified by: the size and scope of the program, which is present in all Brazilian states; the increase in the number of scholarships within a short period of time; and the significant funds annually allocated to sponsoring it.

Another aspect that helps explain our interest in Pibid is the various and significant ways it has been defended since 2015, with the beginning of the political and economic crisis in Brazil, which pointed to real chances of reducing and restructuring Pibid. Manifestations occurred in all kinds of forms: via social networks; official letters to the Ministry of Education (MEC) and to the office of the Capes director; hundreds of letters signed on behalf of partner institutions to the program management team; individual manifestations; strengthening of the actions of the Forum of Institutional Coordinators of the Pibid (Forpibid); public hearings on the subject at the Chamber of Deputies and at the Senate. In general, the manifestations emphasized the contributions of Pibid to initial teacher education, as well as the importance of its continuity, as shown in the excerpts from the documents below:

The way it was conceived, structured and put into operation, and especially in view of the profitable environment it introduced in our educational system, the Pibid represents one of those indispensable measures for structural improvements in Brazilian education. We all know it: good students come from good teachers, and quality education requires wellqualified educators. It is in this direction that Pibid moves. It cannot be paralyzed, it cannot be prevented from reaching its objectives.2 (ACADEMIA BRASILEIRA DE CIÊNCIAS - ABC; SOCIEDADE BRASILEIRA PARA O PROGRESSO DA CIÊNCIAS - SBPC, 2015)

With the decision to study Pibid, we chose a theoretical framework of program evaluation, which allowed understanding elements of the process of design and implementation of Pibid.

Thus, this study proposes to qualitatively evaluate the process of design and implementation of the Pibid based on the theoretical-methodological framework of Theory-Driven Evaluation (TDE). The investigation was guided by the following questions:

How did Pibid design process occur?

How did Pibid implementation process occur?

Are program’s theoretical principles present in Pibid’s training experiences?

In the last ten years, how did Pibid affect the improvement of the initial teacher education process?

To answer these questions, different methods of data collection were defined based on a qualitative approach to be detailed in the section on methodological procedures.

CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THEORY-DRIVEN EVALUATION TO THE EVALUATION OF EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS

According to Worthen, Sanders and Fitzpatrick (2004, p. 69), the birth of the modern program evaluation arises from the enactment of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in 1965, in the United States:

[...] as it designated a significant increase in federal funds for education, and there was no convincing evidence, in the senators’ view, that any federal funds in education had ever resulted in genuine educational improvements.

Over time, the field of evaluation grew complex with the emergence of new theoretical positions and new methodological approaches.3 Since this research was based on principles of Theory-Driven Evaluation for an evaluative study of Pibid, we sought to identify the researchers who contributed to its proposition.

Lipsey (19934 apud CORYN et al., 2011) recognizes that the combined work of Rossi and Chen in the 1980’s made a major contribution to the debate about the role of theory in evaluation. The studies published at the time proposed that each social program embodies a theory of action, which in turn reflects the assumptions inherent in the program and how it hopes to bring about change in the social problem it addresses. Rossi and Chen (1987) argue that it is the role of evaluators to make that theory clear.

With the development of modern program evaluation, Rossi and Chen (1987), acknowledged as authors who discuss questions related to evaluation methods, proposed a new current, with a view to overcoming the limits of the previous phase. The authors write about theory-driven evaluation as part of a movement to overcome the so-called “black-box” evaluations, which only allow the final product to be evaluated, and report only on the success or failure of an intervention. In turn, theory-driven evaluation seeks causal relationships between program components, thus allowing to understand the successes and errors and to identify the intervention’s weaknesses (CHEN, 1989).

Davidson (20055 apud CORYN et al., 2011) emphasizes that one of the advantages of this approach is the fact that a program’s theory explicitly shows the relationship between its various components. He also highlights the potential of theory-driven evaluation to generate information that can contribute to improve the program itself.

Coryn mentions Scriven and Stufflebeam as the main critics of this approach. Scriven (19986 apud CORYN et al., 2011) considers that the evaluator’s role is to determine whether programs are effective, rather than explain how they work. In turn, Stufflebeam (20017 apud CORYN et al., 2011), argues that it is not easy to apply a program’s theory, which is often misunderstood. In addition, he considers that this is a costly evaluation type and that there may be conflicts of interest in considering the evaluation process stakeholders.

In contrast, the same article lists a number of researchers who support the approach:

Contrary to the critics’ assertions, however, the value of theory-driven evaluation, to some, remains not only in ascertaining whether programs work but, more specifically, how they work (Chen, 1990, 2005a, 2005b; Donaldson, 2003, 2007; Donaldson & Lipsey, 2006; Mark, Hoffman & Reichardt, 1992; Pawson &Tilley, 1997; Rogers, 2000, 20078). (CORYN et al., 2011, p. 207)

In his study published in 1994, Chen responds to that criticism with two arguments: first, if Scriven uses as an example the evaluation of products such as cars, televisions and watches to say that the evaluator’s role is just to judge the quality or merit of the product, Chen finds it inappropriate to judge the value of social programs exclusively by the achievement of goals or by external merits. The author emphasizes that it is equally important to gain insight into how the goals of the program have been achieved; and, secondly, program improvements are an essential part of evaluations, which justifies the importance of including stakeholders’ views (CORYN et al., 2011).

The book Theory-Driven Evaluation, published in 1990, is recognized as an important milestone which has helped to consolidate the theorydriven approach to evaluation. Since then, it has been adopted frequently by theorists, researchers and practitioners (ROSSI, 1990; CORYN, 2011). For this reason, we selected Chen as the main theoretical framework for the purposes of this study in order to guide us in outlining the Pibid Theory, to be discussed later.

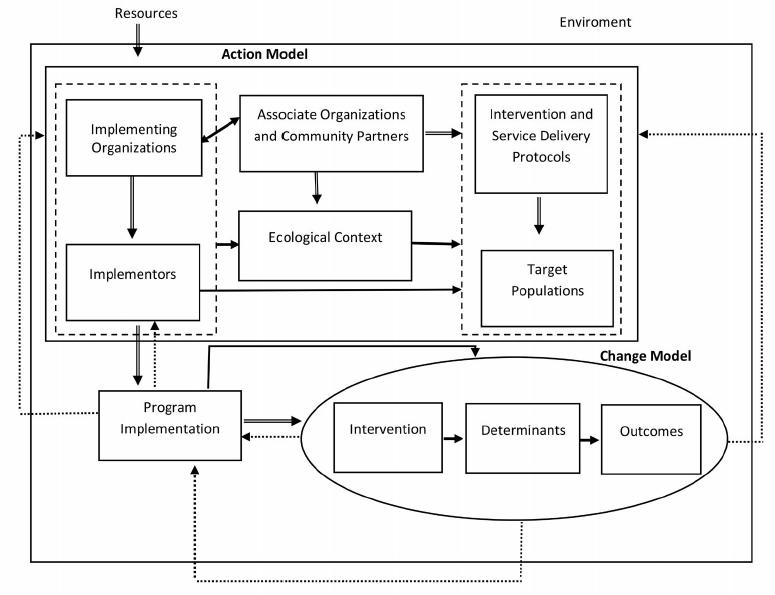

According to Chen (2005), Theory-Driven Evaluation is a stakeholder-oriented methodological approach that seeks to conceptually explain the model of the program by clarifying how and why the observed outcomes are achieved. The program’s theory is outlined from the definition of two analytical frameworks - i.e., the action model and the change model - and is usually represented as a framework (CORYN, 2011),9 which presents the relationships between the expected actions, the actors involved, elements of the context and the outcomes, as can be seen in Figure 1.

The program theory conceptual framework (Figure 1) shows that the action model must be properly implemented to activate the transformation process in the change model. In order for the program to be effective. According to Chen, (2012, p. 18):

[...] the action model must be solid and its change model plausible. The implementation should also be going well. The arrows illustrate evaluation feedback, whose information can be used to improve the planning or development of the action model. Likewise, change model information can be used to improve the implementation process and the action model.

The program theory is a non-linear conceptual model intended to guide the evaluation, facilitating the understanding about the program’s operation (CHRISTIE; ALKIN, 2003). The model allows revealing the explicit or implicit assumptions made when the program was designed, as well as the reasons why the program would be appropriate to overcome the public problem in question (CHEN, 2005). In addition, the program theory clarifies context factors and mechanisms that may or may not contribute to the success of the intervention.

The analysis of the action model allows understanding how the context factors and the activities of the program are organized so that its implementation can result in the expected changes. In turn, the change model allows understanding how the intervention affects the observed outcomes, in order to answer the following evaluative question: does the program adequately act on the right determinants in order to generate the expected change?

Based on this framework of Theory-Driven Evaluation, we sought to outline a plausible Pibid Theory so that the evaluative questions that guide this study might be satisfactorily answered. Therefore, in the next section we present the methodological procedures adopted over the course of the study.

METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURES

Based on the model proposed by Theory-Driven Evaluation, the study was structured in two stages.

Initially, efforts were made to collect data in order to outline the Pibid Theory and the respective “action and change models”, as guided by the first two research questions. In order to understand the political and institutional context during the Pibid design and implementation processes, different methodological strategies were used, such as: analysis of Pibid formal documents; and semi-structured interviews with different managers who worked at Capes, MEC or the National Education Council (CNE).

Then, we conducted a content analysis of the abstracts of articles published in the working group on the training experiences of Pibid, at the 5th National Meeting of Licensure Programs (Enalic) and at the 4th National Pibid Seminar, held in 2014, in order to check whether the principles postulated in the Pibid Theory are actually present in the program’s training experience. This step is related to the third research question.

In turn, the fourth question is the most comprehensive, and presupposes an articulated reflection on the three previous questions.

Our study was based on these three different methods of data collection, which were chosen in a way that is consistent with the perspective of a qualitative approach, which, according to Chizzotti (2011), seeks to interpret the meaning of the event based on the meaning people attribute to the phenomenon.

The very choice of Theory-Driven Evaluation as our theoretical framework among other possible approaches was based on the fact that it values a nd considers in its model the vision and understanding of the actors involved. The conceptual framework we proposed is based on the explicit and implicit assumptions of stakeholders (CHEN, 2012), and therefore it was necessary to find methodological strategies that allowed accessing the viewpoints of the program managers and beneficiaries in order to help outlining the action model and the change model.

OUTLINING THE PIBID THEORY

Pibid is a program that fosters initial teacher education and the valorization of teaching by providing scholarships to undergraduate licensure students to enable their introduction into public primary schools.

The dynamics of the program consist in providing of scholarships as an incentive and valorization tool to licensure students who are members of teaching initiation projects developed by HEIs, in partnership with basic education schools in the public education system. Operationalizing the projects required not only the scholarships, but also the transfer of annual resources to fund the development of the planned activities.

The HEIs send a single institutional project to Capes, in response to its calls for projects; that single project compiles the subprojects that correspond to each of the licensure programs interested. The projects must meet the requirements of each call, but they generally should involve licensure students in the daily life of partner public schools since the beginning of their teacher education. The proposals should also detail the criteria for the selection of fellows, partner schools and the strategies for monitoring and evaluating results.

In the Pibid design, the scholarship represents an instrument of attraction and valorization of its participants. In addition to the licensure students, the other actors in the project are also benefited with a monthly grant,10 according to the following modalities: Teaching initiation (licensure students); Supervision (public school teachers - basic education - who supervise at least five and a maximum of ten students-fellows); Coordination of area (licensure teacher who assists in managing the project at the HEI), Coordination of management area (licensure teacher who assists in managing the project at the HEI) and Institutional coordination (licensure teacher who coordinates the Pibid project at the HEI).

The licensure student is the focus of the action, the main beneficiary of the program (target population). He circulates between the spaces of the HEI (implementing institution) and the school (ecological context), under guidance of the coordinator of area and the supervisor, a basic education teacher (implementors). In turn, the Capes (implementing institution) has a direct relationship with the Institutional Coordinator (implementor), who is responsible for managing the project and for mediating the dialogue between all parties involved.

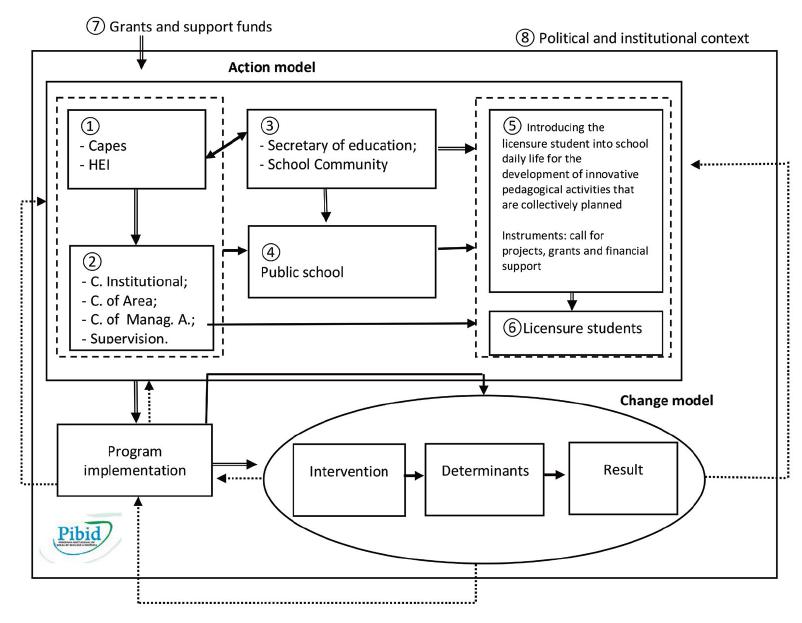

The Figure 2 below refers to the action model that represents the actors involved in the Pibid implementation process and facilitates understanding the program dynamics.

Source: prepared by the authors.

1) Implementation Organizations; 2) Implementors; 3) Associate Organizations/Partner Communities; 4) Ecological Context; 5) Intervention; 6) Target Audience; 7) Resources; 8) Environment.

FIGURE 2 Pibid Theory Conceptual Framework

Item 4 refers to the ecological context, understood here as the main locus of the program action, which, in the case of Pibid, is basic education schools.

With an understanding of the action model, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of Pibid’s objectives in order to advance the discussion about the change model.

Based on the documentary analysis, some variation was found in the statement of the program’s objectives in the different Pibid regulations issued from 2007 to 2013. However, we were able to identify that the focus of the program is the licensure student and the improvement of his training process. To conduct this study, we assumed that the main objective of the Pibid is: to improve the quality of the initial teacher education process.

According to Chen (2012), the change model describes the causal process generated by the program and, in order for it to be defined, three elements must be observed: the goals of the program, its determinants and its results.

To explain what determinants are, the author clarifies that in order for programs to reach their goals, they require a particular focus, with clarity about the lines the project must follow: “Each program must identify the mechanism or lever on which it should intervene to meet its need” (CHEN, 2012, p. 18). In other words, the determinants are constructs on which the interventions must act so that the expected changes are brought about. The change model proposes the following question: does the program act appropriately on the determinants to generate the expected change? A graphic representation of the model makes it easier to understand it (Figure 3).

Therefore, it is important to understand whether the Pibid acts on the correct determinants to result in better initial education processes.

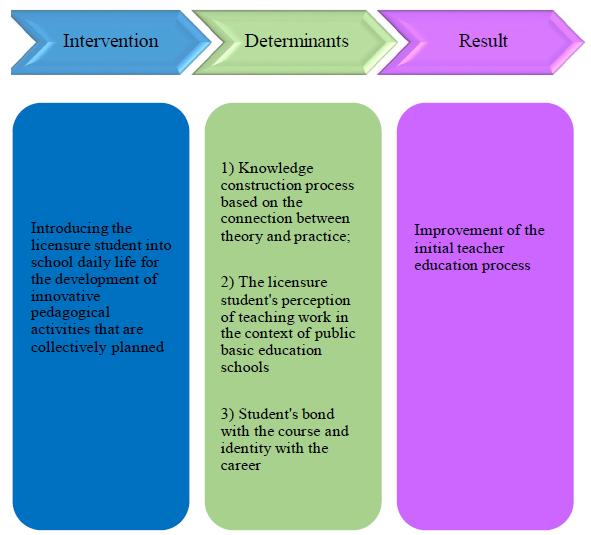

The change model was outlined based on documentary analysis and interviews, which helped outline the program theory, revealing explicit and implicit premises about how the proposed action intends to interfere with results. The action model clarifies how the Pibid’s intervention occurs. Considerations on the objectives of the program set forth in the ordinances regulating the program led to an understanding of the results that Pibid intends to achieve; in turn, the determinants were defined based on the convergence between what the theorists of the area say about the problems and gaps in teacher education and what is set forth in the sections on the dimensions of teaching in Pibid Regulation, n. 96, of 2013 (BRASIL, 2013), and Resolution no. 2, of 2015 (BRASIL, 2015a) of the CNE on the National Curricular Guidelines for Initial Teacher Education in Higher Education and Continuing Education. It is worth considering that both documents were issued and published after a wide discussion involving the managers and coordinators of Pibid, entities related to educators’ movements, and researchers interested in the area of teacher education.

From the analysis of the documents above, we were able to define three determinants on which the Pibid operates with a view to improve the initial teacher education process. In order for the program to achieve the expected result, it must be able to interfere with: 1) the process of knowledge construction, guaranteeing the connection between theory and practice; 2) the licensure student’s perception of the teaching work in the context of public basic education schools; and 3) the bond the licensure student forms with the program and with the teaching career.

Figure 4 summarizes the change model, facilitating its understanding:

Once the action and change models are defined, the question is whether the principles postulated by this program theory are present in Pibid’s everyday training experiences.

ANALYSIS OF PIBID’S TRAINING EXPERIENCES IN THE LIGHT OF THE PROGRAM THEORY

At this point in the study, the dilemma was to find a strategy that would allow us to understand how the Pibid materializes on an everyday basis. Our intention was to know a vast repertoire of experiences that enhanced the actors’ point of view and minimized the interference of the researcher. Thus, we decided to analyze 507 abstracts of the articles published in the Annals of the 5th Enalic and 4th National Pibid Meeting (2014). After checking the files, we excluded those without abstracts, as well as two cases of duplicate texts, so that 493 abstracts remained for analysis.

In order to access the reports of experiences contained in the abstracts of the academic articles chosen as corpus of this study, the method we chose was content analysis, which is intended to interpret communication (BARDIN, 1977). Content analysis seeks to extract meanings from the text (ORLANDI, 2015), and the most common technique is categorical analysis, which consists in dividing the text into thematic units which are then grouped into categories.

After the defining of the categories, the material was coded in a process by which excerpts of the texts were classified and aggregated using the MAXQDA software, which helped treat and organize the information.

Qualitative analysis of this nature presupposes that the inference process is based on the presence of the theme or category, and not just on the frequency of its appearance in each individual communication (BARDIN, 1977). Considering that a limit of the data chosen refers to the reduced and objective text imposed by the format of an academic article abstract, the material presents what the informants decided to reveal and prioritize in that short space about their experience with the program.

The greatest research effort was put in the content analysis of the abstracts because they contained the narratives of the beneficiaries about the program, which can collaborate to validate the Pibid Theory. Therefore, the goal of this stage of the study was to verify if there is correspondence between the principles postulated in the program theory and beneficiaries’ reports on their experiences with Pibid.

During the first reading of the texts, in order to know the content of the material to facilitate the next stage of construction of themes and categories, a first analysis was carried out with the purpose of verifying the quality of the corpus chosen for the analysis and what the articles represented in relation to Pibid.

As for the authorship, there were all the profiles of Pibid fellows: coordinators (HEI faculty); supervisors (basic education teachers); and students (licensure students), who account for the largest group, appearing as the leading authors in 300 articles of a total of 493.

The distribution of the articles according to geographic region corresponded to the expectation that the event of national scope would be able to gather experiences from all regions. The fact that the event took place in city of Natal helps explain the significant participation of fellows from the Northeast Region, with 44.8% of the articles. However, even the regions with a smaller representation, i.e., North and Central West, with 11.2% of the total, still participated in the selection, with 55 articles each.

In relation to the states, it was surprising that the Working Group (GT) in question managed to gather 24 states, not only Amapá, Rondônia and Roraima. In relation to type of HEI to which the authors of the articles are affiliated, all profiles are present, with most of the experiences coming from public HEIs. Although the percentage of 8.1% of experiences related to private institutions appears small, if we consider the total of 493 articles, it represents the opportunity to access 40 accounts of experiences at these institutions.

With regard to the areas of knowledge, of the 28 licensure programs selected in the Pibid call for projects 2013, we can find experiences in 23 areas, not only articles from the areas of Agrarian Sciences, Nursing, Religious Education, Letters-Italian and Theater.

With the content analysis of the abstracts of the 493 articles selected, themes emerged that were grouped into categories to facilitate the understanding of the experiences of Pibid fellows, whether they were students, supervisors or coordinators, in relation to the determinants outlined by the program theory.

The guidelines for analyzing the abstracts were taken from the change model in order to check for the presence of the principles of the Pibid Theory in the informants’ accounts. We found a correspondence between the categories that emerged from the content analysis and the guidelines previously defined by the change model, as presented in Table 1.

CHART 1 Code System for the Content Analysis of the 493 Article Abstracts

| COLOR | CATEGORIES | THEMES | CODIFIED SEGMENTS | DOCUMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a .Article Information | a. Title | 493 | 493 | |

| b. Pibid Training Experience | b. Account on Pibid teaching experience | 393 | 381 | |

| 1. Articulation between HEI and School | 1.1. Introduction into school through Pibid | 115 | 104 | |

| 1.2. Being closer through internship | 18 | 12 | ||

| 1.3. Contribution to HEI | 5 | 5 | ||

| 2. Collectively planned activities and processes | 2.1. Planing Content | 319 | 267 | |

| 2.2. Planning Routine | 70 | 64 | ||

| 3.Pedagogical strategies | 3.1. Differentiated class methodology | 356 | 264 | |

| 3.2. Making didactic material | 44 | 35 | ||

| 3.3. Considerations on the results of intervention | 262 | 235 | ||

| 4. Introduction into school’s daily routine | 4.1. Observations in the school environment | 86 | 80 | |

| 4.2. Management context | 58 | 50 | ||

| 4.3. Material context | 16 | 15 | ||

| 4.4. Context of the relationship with the school community | 25 | 23 | ||

| 4.5. Relationship with supervisor | 35 | 29 | ||

| 5.Theoretical perspective of pedagogical practice | 5.1. Article theoretical foundation | 31 | 30 | |

| 5.2. Theoretical reflection about practice | 341 | 280 | ||

| 5.3. Reflection about the social context of learning | 140 | 126 | ||

| 6. Bond with licensure program | 6.1. Grants and support funds | 1 | 1 | |

| 6.2. Identity with licensure program | 18 | 17 | ||

| 7 . Building a teacher identity | 7.1. Becoming a teacher | 167 | 129 | |

| 7.2 Expectations about profession | 52 | 50 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from GT 15, Enalic (2014).

Category a, referring to “Article Information”, corresponded to the coding of the titles of the 493 articles analyzed. The information worked as an important marker to track the evolution of the analyzes, since all documents would necessarily have their title codified only once. Category b, “Pibid Training Experience”, sought to identify all articles that explicitly announced an account of an experience with the Pibid. A total of 381 articles were identified with this purpose, thus confirming the expectation that the texts represented a very diverse range of experiences within the Pibid.

Categories 1, 2 and 3, respectively “Articulation between HEI and School”, “Collectively planned activities and processes” and “Pedagogical strategies”, dialogue with the change model, which says that Pibid’s intervention consists in: introducing the licensure student into the school’s daily life for the development of innovative pedagogical activities that are collectively planned.

Categories 4, 5, 6 and 7, respectively “Insertion into school’s daily routine”, “Theoretical perspective of pedagogical practice”, “Bond with licensure program” and “Building a teacher identity”, converge, in turn, with the elements announced in determinants.

ANALYSIS OF RESULTS

The outlining of the Pibid action and change models contributes to the discussion regarding the first two questions guiding the research, which seek to understand how the process of design and implementation of the program took place.

Regarding the environment, which represents, in the action model, the macro context in which the Pibid is situated, the documents and interviews allowed understanding that in 2007 there was a favorable political and institutional conjuncture for the emergence of the program.

The movement of educators articulated in entities such as the National Association of Postgraduation and Research in Education (ANPED), the National Association for the Professional Educators Formation (ANFOPE), the National Confederation of Workers in Education (CNTE) and the Forum of the Directors of Faculties of Education at Brazilian Public Universities (FORUNDIR) presented their criticism to the Ministry of Education about the lack of actions for initial teacher education in the Education Development Plan (PDE), launched in April 2007. Haddad remembers the time the Pibid was proposed:

It [the Pibid] arises amidst criticism to the PDE. After the PDE was launched, the entities related to teacher training pointed to this gap. The PDE has a lot of good things, it’s an almost complete program, but it has nothing innovative in the area of t eacher education, initial teacher education. And then we assimilated the criticism, we saw it was pertinent [...]. The Pibid was, therefore, a response from the Ministry to a pertinent criticism to the PDE. 11 (HADDAD, 2017)

The Pibid was then launched as part of the PDE’s complementary actions in December 2007 and was well received by the institutions because there was a convergence between the program’s design and the issues that were being debated in universities, as Dourado (2017) points out:

Because I think it’s important to say that, let’s say, these references were already being discussed, i.e., the Pibid is only well assimilated, the way I see it, because it brings references that the universities had been discussing. The universities already felt that need. 12

The HEIs quickly adhered to the Capes calls for projects and started their projects.

The implementors, defined as the actors responsible for operationalizing the program, in the case of Pibid, are Capes and the HEIs. From the institutional perspective, the program faced a beginning marked by legal and budgetary difficulties, due to the need to adapt their formal instruments to the new teacher education actions. Once the obstacles were overcome, Capes proved a favorable institutional environment for the implementation of the program, mobilizing budgetary resources and personnel for its management. The program expanded as new calls for projects were launched. And the implementing institutions, i.e., Capes and the HEIs built a productive dialogue, which resulted in improvements in the Pibid’s legal regulations. Later in the history of the program, the institutional coordinators organized themselves as a forum to facilitate their dialogue with the Capes management team, and amidst a crisis scenario, formed a movement at national level in defense of the program.

With regard to the target audience, it became clear from the action model outlined that the main beneficiaries are the licensure students, and the focus of Pibid is on their initial education process. Dourado (2017) reinforces that view:

[...] the central element of the Pibid is that it was necessary to ensure students a more effective initiation in teaching, and to that end, a greater articulation was necessary between the teacher education institutions and basic education schools, therefore Pibid comes with this design. Primarily a program focusing on licensure programs. 13

Based on the Pibid theory, we can say that any other expectation of results for the program means to extrapolate from what its design allows. In this respect, it is worth remembering former Minister Mercadante’s criticism to the program at the time of his inauguration speech at the MEC, in October 2015:

[...] another recognized complementary program in teacher education, the Pibid (Institutional Teacher Initiation Scholarship Program), which currently serves 90,000 fellows, retains only 18% of them as teachers in public basic education. Let’s review Pibid. 14 (BRASIL, 2015b)

However, results of a survey with Pibid alumni conducted in 2017 revealed that 64.1% of respondents are working in the area of education. The study concluded that Pibid, along with two other programs analyzed, represent:

[...] an advance in initial teacher education to reduce the distance between the training provided in higher education and the work place, allowing better articulation between theory and practice and contributing to the improve the quality of licensure programs.15 (ANDRÉ, 2017, p. 2)

Silveira (2017) also refutes the idea that Pibid prioritizes the improvement of education in primary schools, and insists that its main purpose is to improve the teacher education process for licensure students:

What is Pibid’s real focus? Is it to solve schools’ Ideb? No, Pibid doesn’t have that design however much he wanted to in the beginning, it never had that design. Because then, it would be another program. Is it really for us to research the school? It’s not that either. It’s possible to research the school, but we won’t solve the school’s problems. [...]. So perhaps what was most important for Pibid was to engage the student in the school dynamics. 16

With regard to the ecological context, in the case of Pibid, the public system of basic education schools was considered the main locus for the program’s action. When analyzing the profile of the projects’ partner schools, based on the infrastructure scale proposed by Soares Neto et al. (2013), the following distribution was observed:

TABLE 1 Distribution of the number of schools in Pibid by infrastructure level

| LEVEL | FREQUENCY | PERCENTAGE (%) |

| Elementary Infrastructure | 362 | 7.30 |

| Basic Infrastructure | 2.083 | 42.3 |

| Adequate Infrastructure | 2.334 | 47.3 |

| Ideal Infrastructure | 133 | 2.7 |

| No Information | 18 | 0.4 |

| Total | 4.930 | 100 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from CGV17/DEB/Capes.

It is observed that 47.3% of Pibid partner schools were found to have an adequate infrastructure, “allowing a more conducive environment for teaching and learning” (SOARES NETO et al., 2013), with spaces such as library, teacher’s room, computer lab, children’s toilet, as well as a sports court and internet access. In addition, 42.3% of the units are categorized as schools with a basic level of infrastructure, which includes a principal’s office and some equipment such as TV, DVD, computers and printers.

The basic and adequate infrastructure levels were found to provide the licensure students with conducive spaces for them to develop differentiated teaching-learning methodologies so as to experience teaching.

Partner organizations are those that do not have an active participation in the program’s design. In the case of Pibid, education departments and the school community were recognized in the program’s graphic representation as partner organizations, but without formal responsibilities in implementing the action. Since the calls for projects did not foresee or guide the participation of education departments and school communities in the projects, that participation varied a lot, depending on the local conjuncture. Certainly, questions concerning the relationship of education departments with Pibid projects deserve attention in future studies.

Finally, with regard to Pibid intervention, it is important to highlight the role of the management tools. In addition to guiding the activities, the calls for projects establish the attributions of each of the actors and institutions involved and, together with the grants, promote the commitment and dedication of participants. Guimarães (2017) recognizes that the grants have an important role of “attraction”. In turn, Amaral (2017) highlights the role of contributing to “improve self-esteem, reduce licensure drop-off rates and improve students’ interest in enrolling in licensure programs.” Neves (2017) agrees with some of these arguments and acknowledges that:

The grant to the student, it’s an important thing. It’s important not only to attract young people to the Pibid, but they also use it as a means to remain in the program. There are several student accounts in which, because of the scholarship, they were able to stay. 18

The support funds ensure conditions of implementation:

Support funds are crucial. So when you want a policy to work, it’s critical to ensure that funding; and Pibid comes with support, even if it comes in the condition of a program within the limits of the calls for projects, but it will have a growing dynamic. 19 (DOURADO, 2017)

The instruments have played an important role in operationalizing the program on an everyday basis, along with the dynamics and relationships established between the other actors and institutions. The next step is to discuss how the Pibid’s operationalization activates the change model.

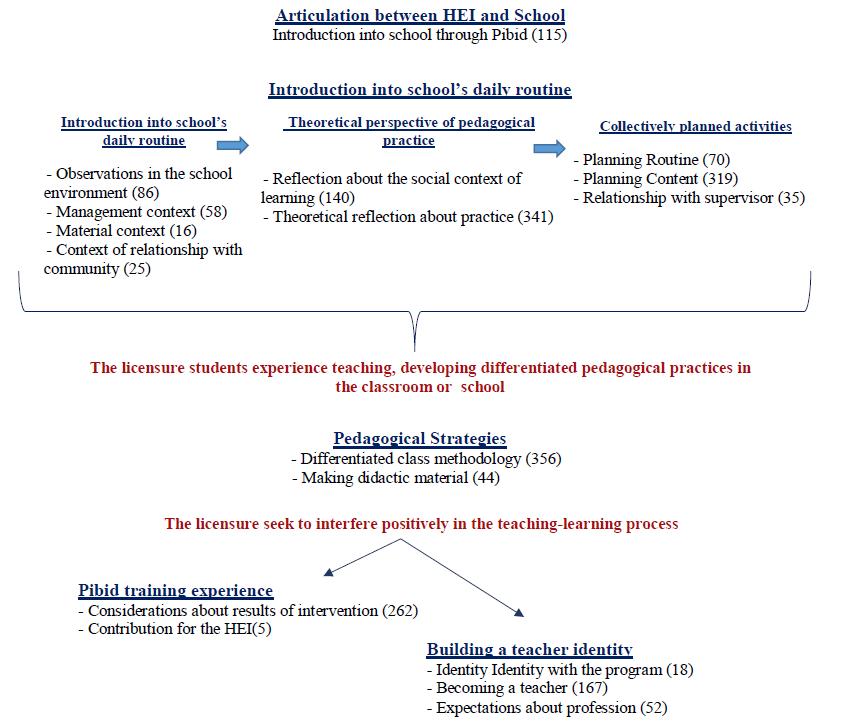

As for the third research question, i.e., whether the principles of the program theory are present in the Pibid training experiences, the analysis of the set of categories and themes helped understand how the program materializes on an everyday basis, as presented in the Chart 2:

Source: Prepared by the authors.

Note: The categories are underlined and, below them are the themes and their frequency.

CHART 2 Categories and themes related to Pibid’s intervention

Based on the analysis of the abstracts and the categories presented in the previous chart, we can infer that the articulation between the HEIs and schools, which occurs through the Pibid, allows the licensure student to be introduced into the school routine. During that time, the licensure student has the opportunity to make observations in the school environment and come in contact with the material context, as well as with the contexts of management and community relationship. From these observations of and from being closer to public basic education schools, there is a process of theoretical reflection that will found the planning of their activities. Theoretical discussions and planning are carried out in group, under guidance of the supervisor and/or the coordinator. The planning guides the activity that will be carried out by the licensure student in the classroom or school, and it almost always seeks to interfere with the teaching-learning process through the development of differentiated class methodologies, often with students making didactic material. The students’ experience in teaching interferes in their training process and in the construction of the bond they form with the licensure program and with the profession (becoming a teacher and expectations about the profession).

Note that a correspondence can be established between the categories that emerged from the analysis and the change model outlined:

Categories related to the intervention (introducing the licensure student into the school routine for the development of innovative pedagogical activities that are collectively planned):

Categories related to the 1 st determinant (knowledge building process based on the articulation between theory and practice): • Theoretical perspective of practice;

Categories related to the 2 nd determinant (licensure student’s perception of the teaching work in the context of public basic education schools):

Category related to the 3 rd determinant (licensure student’s bond with the licensure program and identity with the teaching career):

The correspondence between the principles postulated in the Pibid change model and the categories that emerged from the analysis of the accounts allows validating the Pibid theory, so that in fulfilling what is proposed for the program, it shows conditions to achieve the desired result.

CONCLUSIONS

From our analysis of Pibid’s design and implementation processes, we found that the program’s action model presents an articulation between the partner institutions and the actors, who are mobilized by incentive and valorization instruments, which results in an effective change model. Thus, by intervening on the correct determinants, the Pibid has interfered positively in the initial teacher education process.

Based on the Pibid theory and the analysis of categories of fellows’ accounts of training experiences, we found that the program has allowed students to have experiences in line with an expanded teaching concept. In addition to experiencing the teaching-learning process in the classroom, the licensure student has been encouraged to participate in the context of the school in a reflexive and committed way, including in the organization and management processes. The student’s introduction into the school occurs with key guidance by the supervisor and the coordinator, thus enriching the student’s training process. In addition, the experiences shared show the program’s important role in strengthening the bond with the licensure program and the teaching profession.

Another point refers to the observation that the Pibid theory shows that the program aims to create conditions for students to identify with the teaching profession in the course of their training process. Therefore, it is important to find strategies and methodologies that allow understanding the subjectivities of those involved, thus reaching the meanings that each of them attributes to their training process. This study advances in this direction, by finding ways to access the genuine expression of how the beneficiaries understand and value their experiences in the Pibid. The accounts translated the free choice of issues that each author considered relevant to share, either to emphasize its qualities or to make their criticism.

By reflecting on how Pibid interferes in initial teacher education processes, it was possible to conclude that the program is not exactly innovative in relation to its theoretical assumptions, since they were already established and developed by researchers of the area and by the movement of educators. However, the program innovates in the way it materializes. In that respect, Silveira (2017) considers that Pibid is:

[...] as a systematized policy in scholarship programs that can bring together the theoretical presuppositions of the field of education and combine these presuppositions with a strategic and methodological action, [...] an innovative policy. So, well, its uniqueness is not in its presuppositions, its originality lies in its strategy. And the strategy is not the same as the internship. Its originality lies precisely in enabling this theoretical density to take place in training, take place in the school, take place in the interaction between the school and the university. 20

Despite the contributions of Pibid, the program has very clear budget limits, since it is a program of calls for proposals. Considering the universe of enrollments in licensure programs, the Pibid does not even include 10% of licensure students (BARRETO, 2016). And the dilemma that is posed to managers and stakeholders in the area is to reflect on how the positive experience of the program can reach a greater number of institutions and students. The program was not designed for, and it seems unreasonable to think of universal scholarship for all students, precisely because of budget constraints. On this issue, Dourado (2017) says:

I think a part of her criticism [Elba de Sá Barreto] is quite pertinent, when you look at the number of students, of enrollments in licensure and the program coverage. A program is always limited. So, even though Pibid is a big program compared to others, it is small compared to the number of licensure enrolments. When I think about the program’s level of institutionalization, I’m not thinking about universalizing the fellowships; I am thinking that the institutions should take over the Pibid, and to that end there must be the corresponding funds, but they would be of another magnitude, that is, in terms of development, it could be differentiated. I mean, what does the Pibid do? The Pibid shows that this political-pedagogical action is an effective action that contributes to the training process. So, as such, it needs to be institutionalized. What is the best way? Is it to institutionalize by universalizing grants for all? No. It is institutionalizing into the culture of each institution, which requires support funds and then it would be an institutional support, I mean, turning the Pibid from a program into a policy is to intervene in a more comprehensive perspective of teacher education policy supported by institutions so that this can actually unfold in their institutional culture. 21

From these reflections, a new question arises: what is the possibility of reverberating the experience of the Pibid?

Somehow, the program seems to fill gaps in the curricular teacher internship. The curriculum guidelines for teacher education established by the CNE in 2002 and 2006 already incorporate a rather broad conception of teacher education that should induce processes capable of breaking with the dichotomy between theory and practice. Resolution no. 2, of 2015, of the CNE mentions the Pibid as a horizon of possibilities, as its rapporteur recalls:

[...] Then you come to Resolution 2 of 2015, and that resolution reinforces this identity of teaching initiation a little when it has 400 hours of practice as a curricular component and 400 hours of supervised internship. And, in that design, it opens the possibility of, the Pibid is nominally cited as a horizon of possibilities. It means the institutions could think of their teacher initiation project that wouldn’t necessarily have to be the Pibid, but with that formulation. So you see, it’s the spreading of a policy that would obviously require financial induction and could be in the same way as Pibid itself or by turning the Pibid into a policy. 22 (DOURADO, 2017)

The resolution sets forth that licensure programs provide their students with 400 hours of practice as a curricular component and 400 hours of supervised internship. These two spaces are intrinsic in all licensure programs and should involve all their students. In this respect, it is possible to think of the Pibid as a program that induces differentiated initial education processes. One expects that, based on its successful experience, the Pibid can interfere in the institutional culture of HEIs so they might review their internship proposals and curricular practices. Then, perhaps in the future, it will be possible to speak of the contribution of the Pibid to the overcoming of the fragmented 3+1 training model,23 which is still present in licensure programs.

Finally, the evaluative study of the Pibid based on the model proposed by Theory-Driven Evaluation provides an important contribution to the proposals of curricular internship, practices as a curricular component or even other programs that may be formulated, as it indicates that other initiatives intended to improve initial teacher education should seek to interfere in the three determinants pointed by the change model outlined in the Pibid Theory: 1) providing knowledge building processes based on the articulation between theory and practice; 2) interfering in the licensure student’s perception of teaching in the context of the public basic education schools; and 3) strengthening the student’s bond with the licensure program and the teaching career.

text in

text in