Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Estudos em Avaliação Educacional

versão impressa ISSN 0103-6831versão On-line ISSN 1984-932X

Est. Aval. Educ. vol.32 São Paulo 2021 Epub 25-Fev-2022

https://doi.org/10.18222/eae.v32.7501

ARTICLES

EVALUATION OF SOCIOMORAL VALUES IN TEACHERS IN A MUNICIPAL EDUCATION SYSTEM

IFundação Carlos Chagas (FCC), São Paulo-SP, Brazil; amoro@fcc.org.br

IIGrupo de Estudos e Pesquisas em Educação Moral (Gepem), Campinas-SP, Brazil; flamacavi@gmail.com

This study aimed to identify social perspectives in moral judgments by primary and lower secondary education teachers in the municipal education system of a city in the state of Minas Gerais. We used, in a digital platform, a scale for evaluating adherence to the sociomoral values of justice, respect, solidarity and democratic coexistence, which was designed and validated by an educational research institution. Results pointed to a predominantly normative social perspective on the part of teachers. Based on such results, the teacher education program that is provided to the municipal education system should include studies on education in moral values so that teachers can progress with regard to their sociomoral perspectives.

KEYWORDS: SOCIOMORAL VALUES; LEVELS OF ATTACHMENT TO VALUES; ITEM RESPONSE THEORY (IRT); MORAL EDUCATION

O presente estudo objetivou identificar as perspectivas sociais de juízo moral dos docentes do ensino fundamental da rede municipal de ensino de uma cidade do interior de Minas Gerais. Utilizou-se, em plataforma digital, a escala de avaliação de adesão aos valores sociomorais de justiça, respeito, solidariedade e convivência democrática, elaborada e validada por uma instituição de pesquisas educacionais. Os resultados apontaram uma perspectiva social predominantemente normativa por parte dos docentes. Com base em tais resultados, o programa de formação oferecido à rede municipal deve contemplar estudos sobre educação em valores morais que possibilitem também aos profissionais avanços em suas perspectivas sociomorais.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: VALORES SOCIOMORAIS; NÍVEIS DE ADESÃO AOS VALORES; TEORIA DAS RESPOSTAS AO ITEM (TRI); EDUCAÇÃO MORAL

El presente estudio tiene el objetivo de identificar las perspectivas sociales de juicio moral de los docentes de educación fundamental de la red municipal de educación de una ciudad del interior de Minas Gerais. Se utilizó, en plataforma digital, la escala de evaluación de adhesión a los valores sociomorales de justicia, respeto, solidaridad y convivencia democrática, elaborada y validada por una institución de investigaciones educativas. Los resultados señalaron una perspectiva social predominantemente normativa por parte de los docentes. En base a tales resultados, el programa de formación ofrecido a la red municipal debe contemplar estudios sobre educación en valores morales que también posibiliten que los profesionales avancen en sus perspectivas sociomorales.

PALABRAS CLAVE: VALORES SOCIOMORALES; NIVELES DE ADHESIÓN A LOS VALORES; TEORÍA DE LAS RESPUESTAS AL ITEM (TRI); EDUCACIÓN MORAL

INTRODUCTION

The relevance of working with moral values in education and in society as a whole has been a topic of interest for those who are dedicated to quality education. It is not a matter of advocating the naïve and reductionist work that is present in transmissive and indoctrinating practices, but, to the contrary, a matter of scientifically founding school praxis on diagnosis, analysis, discussion and, mainly, on experiencing values in the schools, such as justice, solidarity, respect and democratic coexistence.

Based on Piaget’s (1994 [1920]) psychological approach, value is an affective mediation between social subjects about their ownership over objects, acts, human products. It is an affective investment that makes us act, that moves us in a particular direction. Thus, moral values are affective motivations placed on rules, principles, judgments, actions, and they define good and bad, right and wrong in human actions in a given group, culture, ethnicity. Such values guide people on how they should act, considering a set of norms, principles, laws, customs, in the relationship with others, in family, in school, in religion, in the media.

In turn, ethical values can be conceived as a deeper intentional reflection on moral values: they investigate the meaning of values, the reasons why we should follow them, which values are more appropriate or important. They allow us to reflect on the reasons to act or live in a particular way or another, on better ways to live. In addressing sociomoral values, we can understand them as those values that guide us on how to be and to live, from an intra- and interpersonal point of view, so as to be in accord with the principles established in society, in culture, guiding us on what is right, good or fair in our relationship with the other, and in collective contexts.

Nowadays, a recurrent complaint is that children and young people have been setting their lives according to values connected to appearances, to recognition through instant fame, to success and wealth. This complaint echoes in the statements of teachers, in the media, in the voice of common sense, and mainly, in studies by authors who discuss postmodernity, such as Lipovetsky (2010) and Bauman (1998).

In this context, we assume that the school is one of the main social institutions that allow, in their interactive dynamic, the maintenance or change of values in society. Thus, it plays a role as important as that of the family in building moral values, as it promotes daily coexistence between children and between young people, while assuming, in this collective life, common norms and values that are considered important to the culture one lives in. Therefore, the school should be a place of coexistence par excellence, in that it allows this coexistence to be more and more democratic, thus fostering the development of moral values.

Thus, in order for moral values to become the object of reflection, discussion and experience in the classroom’s routine and in the school as a whole, it is necessary to observe how teachers have been adhering to values in different situations in the school’s everyday life. In other words, it is important that we understand the social perspective the teacher shows as he adheres to moral values. Based on this understanding, it will be possible to plan actions that foster and strengthen the development of social perspectives which are actually moral, so as to value this aspect of education as the basis for quality and for the construction of students’ moral and ethical values.

Scale of evaluation of sociomoral values

The Carlos Chagas Foundation (FCC) developed, administered and validated, both theoretically and statistically, a scale for evaluating adherence to moral values. The scale is aimed at measuring how the values of justice, respect, solidarity and democratic coexistence are adhered to by children in lower secondary education, by adolescents in upper secondary education and by basic education teachers. In other words, it evaluates the level of sociomoral perspective of the study’s respondents as they are faced with problems involving such values. The values above were chosen considering the theoretical framework of moral development psychology based on Piaget (1977[1932]) and Kohlberg (1992), as well as on Brazilian national legislation, particularly the National Curriculum Parameters - PCN - (BRASIL, 1998), which, by defining ethics as one of education’s cross-cutting topics, emphasize the values of mutual respect, justice, solidarity and dialogue as the most relevant for the moral development of children and adolescents. Measuring instruments were designed so that, based on their results, reflections and discussions can be held with teachers, so as to help them with their work on such topics with their students (TAVARES; MENIN, 2015; MARQUES; TAVARES; MENIN, 2019).

Based on the conceptual definition of value and its descriptors, questions were designed in the form of situational stories taking place in various spaces or social environments - family, school, the internet - and containing elements of moral values. The stories always contain five response choices, which are designed to identify whether the investigated value is adhered to, with three response choices being pro-value and two being counter-value. For example: respect as opposed to disrespect and contempt, justice as opposed to arbitrariness and favoritism, solidarity as opposed to indifference and selfishness, democratic coexistence as opposed to authoritarianism and excessive individualism.

In addition to the positions for and against the values, according to Kohlberg’s (1981, 1992) theory, the response choices present levels of sociomoral perspective1 which show different ways in which people adhere to values. According to the stages of social and moral development, individuals may start from a very self-centered social position, when adhering to a value, by using it only to suit their own needs and points of view (an egocentric social perspective). Later on, they will go through a period in which they extend their considerations to their closest ones (affectively important people such as parents, family, group of friends), and to authorities, rules and social conventions (institutionalized authorities, written and conventional law - a sociocentric social perspective). Finally, people may move on to adhere to values, recognizing that they can be necessary, good or fair to anyone, due to a greater principle concerning the human being’s dignity as the means and the end for any moral principle (a perspective that transcends social conventions, or a perspective that is actually moral).

Below we present an evaluation item concerning the value of justice in order to exemplify the structure of the questions in the measuring instruments that form the scale of sociomoral values.

During break time, in the queue at the dining hall, Manoel accidentally bumps into a classmate and knocks down his food. The classmate starts to call him names, saying he is “a clumsy nerd, a useless moron”. Your teacher saw what happened. What should she do?

C1 - She should scold the one who knocked down the food and give a written warning to the one who called him names.

C2 - She should send a note to their parents showing the problem and asking them to take action about their children.

P1 - She should talk to both students and ask them to sort it out by themselves, after all, they are no longer children.

P2 - She should talk to both students and say they should not fight, and make clear that that is not the attitude expected of the school’s students.

P3 - She should talk to them both and help them find a solution to the conflict.

The scale of justice has four levels ranging from an attitude that counters this value to one that adheres to it from an actually moral social perspective. Here, it is worth noting that there are three aspects of justice: retributive justice, which refers to the attribution of consequences to acts that are considered infractions (penalties); distributive justice, dealing with the distribution of goods, duties, rights among individuals, based on equality and equity; and procedural justice, which reveals the form of judgment established among people. The item above, the situation with Manuel, concerns an item of retributive justice.

The designed items were submitted to experts in psychometrics and in moral development, who evaluated the items’ contents and whether they fitted the reference matrix and its descriptors, thereby validating the contents. After being semantically revised according to the experts’ feedback, the items were arranged so as to form questionnaires which were administered in print to lower secondary students in grades 5-9 (4,503), to upper secondary students (4,193) and to basic education teachers (1,325) at 75 public and private schools. The booklets for children had 16 questions involving two values in each booklet; for adolescents, 20 questions, also with two values in each booklet; and for teachers, 25 questions, with each booklet focusing on three values.

The collected data were processed and analyzed using the Item Response Theory (IRT), more specifically the Gradual Response Model proposed by Shimejima (ARAÚJO; ANDRADE; BORTOLOTTI, 2009). The FCC’s Scale of Evaluation of Sociomoral Values was thus theoretically and statistically validated, which allows identifying the levels of adherence to the investigated moral values. Based on the example above, of an item referring to the value of justice, we exemplify in Chart 1 the description and the response choices by adherence level.

CHART 1 Example of description of the levels of adherence to the value of justice and its response choices

| DESCRIPTION OF THE LEVELS OF RETRIBUTIVE JUSTICE | ||

|---|---|---|

| LEVELS | DESCRIPTION | RESPONSE CHOICE |

| LEVEL 1 | In conflict situations, the person chooses an expiatory sanction, resorting to family authority. Values contrary to justice may also stand out, such as inequality, discrimination, excessive individualism and authoritarianism. | C1 - She should scold the one who knocked down the food and give a written warning to the one who called him names. C2 - She should send a note to their parents showing the problem and asking them to take action about their children. |

| LEVEL 2 | In conflict situations, the person chooses to impose, through authority, a reparation that is proportional to the infraction, or to affirm, through authority, the desirable behavior by means of talks (maintenance of social conventions). | P1 - She should talk to both students and ask them to sort it out by themselves, after all, they are no longer children. |

| LEVEL 3 | In cases of rule breaking or conflict with authorities in the school environment, a person at this level can choose to talk rather than use an expiatory sanction, though they may do so in order to avoid conflicts, because of personal convenience. | P2 - She should talk to both students and say they should not fight, and make clear that that is not the attitude expected of the school’s students. |

| LEVEL 4 | In the field of retributive justice, the person seeks dialogue, aiming at solutions with everyone involved, rather than using sanctions. At this level, the person chooses dialogue between equals, considering that everyone has the same conditions, rights and abilities to solve conflicts through dialogue. |

P3 - She should talk to them both and help them find a solution to the conflict. |

Source: Data from the study.

In Chart 1, we can see that, besides the counter- and pro-value positions (C1, C2 and P1, P2, P3), the item’s choices are also represented in levels that show the way of adhering, understood in this study as the social perspective from which the value is used. In other words, two choices counter the value at the egocentric (C1) and/or sociocentric (C2) level - Level 1. The other three choices affirm the value addressed in the story from sociomoral perspectives at increasing levels of decentering (P1 egocentric, P2 sociocentric and P3 moral), respectively, Levels 2, 3 e 4.

Considering the possibilities of investigation provided by FCC’s evaluation scale, as well as the relevance and complexity of topics related to the measuring of values in education, we made a diagnosis, along with teachers in the municipal education system of a city in the state of Minas Gerais, so as to observe how they adhere to sociomoral values and thus help them set about designing programs and projects in the schools, aiming at intentional work on values in education, based on evidence found through diagnosis at the institutions.

The context of the study

Since the beginning of their 2016-2020 administration, the municipal education management team had been stressing the importance of working with values in the school. Thus, the first action taken by the Municipal Department of Education (SME) was to evaluate the School Climate in every unit, also by administering a scientific instrument.2 Once the diagnosis for each school was made, the SME team developed a training program to address those aspects that were recognized as the weakest in the system regarding coexistence between people, but also involving knowledge building.

The SME’s target, i.e., implementing the Coexistence Plan as a municipal public policy for education, required commitment to ensuring rigor in the diagnosis. Thus, partnering with research support institutions and using scientific instruments would help the school conduct intentional, well-planned work oriented towards ethical coexistence.

Some of the results of the climate evaluation denounced centralizing and coercive relationships between the different actors in the schools (teachers, students, management team). Even though the results varied from school unit to school unit, there was already evidence that the heteronomous moral tendency not only predominated but, in some cases, was strengthened by relationships in which threats, for example, were constantly present in all kinds of interaction. Therefore, in order to better guide and organize the continuing education program provided by the SME to the municipal system’s personnel, knowing teachers’ and students’ social perspectives in adhering to the moral values of justice, respect, solidarity and democratic coexistence made the planning process even sounder. The goal of providing students with education for moral and intellectual autonomy presupposes, on the part of the system’s personnel, particularly of teachers, stances that reflect and promote such characteristics. In other words, the heteronomous teacher is unable to contribute to educating the autonomous student. His practices and stances prevent or hinder the exercise of reciprocal respect in relationships that is essential to the development of autonomy.

In this direction, the SME accepted FCC’s proposal to administer the evaluation instruments to students in the municipal system’s schools, and expanded the proposal so as to have the instruments administered to teachers in the system before administering them to the students.

The SME’s objective was to know, first, the social perspective of teachers in adhering to social values, in order to analyze the results in a dialogue with the findings concerning the quality of human relationships across the schools; subsequently, the instrument would be administered to the students, and the results would be analyzed for both groups, thus helping the SME team plan training actions to meet the schools’ needs and expectations.

A Scientific Collaboration Agreement was signed by the research institution responsible for the evaluation of values and by the Municipal Government/Department of Education with the purpose of administering the instruments during May and June 2018.

METHODOLOGY

Based on the structure of FCC’s scale of evaluation of adherence to sociomoral values, we organized a questionnaire intended for teachers in the municipal system. It was planned to be administered via an on-line platform (Survey Monkey) and it has two parts. The first part has 40 items: 10 referring to the value of justice; 10 to the value of respect; 10 to solidarity; 10 to democratic coexistence; and two open-ended questions (one relating to democratic coexistence and the other to respect). The second part of the questionnaire is formed by questions that aim to characterize the profile of respondent teachers (sex, age, socioeconomic status, education, time in the profession, positions held in the profession) and their work context (questions about social relationships in school and in family).

The respondents were 873 teachers of grades 5-9 at 33 units in the municipal system - 35 schools and 8 units of the Municipal Program for Youth.

In this context, this question seems necessary: what is the level of adherence to the values of justice, respect, solidarity and democratic coexistence that the teachers participating in this survey present?

Hypothetically, it is possible to think that the level of adherence to values reveals a few characteristics of the teachers regarding the work to be developed in basic education, particularly in primary and lower secondary education, concerning moral values, as well as their main perspectives in the different values evaluated.

Thus, the objective of this study was to identify the presence of and the way of adherence to the sociomoral values of justice, respect, solidarity and democratic coexistence in teachers in the municipal education system of a city in the state of Minas Gerais, based on their judgment of problem situations presented in the questionnaire.

Statistical processing

The procedures of analysis of the collected data were different for each set of responses of the teachers. Regarding data from the questionnaires of adherence to sociomoral values and their response choices, we employed the same method used to validate the Scale: Item Resonse Theory (IRT) (ARAÚJO; ANDRADE; BORTOLOTTI, 2009).

IRT allows studying latent variables, i.e., variables that cannot be directly observed or measured, e.g., certain forms of knowledge or personality characteristics. Adherence to values can also be indirectly measured as a latent trait. Thus, in order to measure this trait, we analyzed the response choice marked by participants for each situational item about values, which asked what the story’s main character should do. To this end, we used one of IRT’s analysis models: the Gradual Response Model proposed by Samejima. It is suitable for analyzing polytomous responses, i.e., all possibilities of response are viable, there is no right or wrong. The items for evaluating the values addressed here followed that logic, they had five possibilities of response (the counter-value choices, i.e., C1 and C2, and the pro-value choices, i.e., P1, P2, P3), and not just one correct and one wrong answer (ARAÚJO; ANDRADE; BORTOLOTTI, 2009).

Based on this methodology, we were able to identify the levels of adherence for each value, considering being for or against the investigated value, in addition to the three social perspectives considered as ways of adherence (an egocentric, sociocentric or moral perspective). Level 1 corresponds to a counter-value stance; Level 2 to a pro-value one, from the egocentric perspective; Level 3 corresponds to a pro-value stance from the sociocentric perspective; and Level 4 corresponds to a pro- -value stance from the moral perspective.

Regarding the open-ended items, about democratic coexistence and respect, the contents of the responses to the two questions were analyzed in two steps. In the first, responses were processed using the Alceste (Analyse Lexical par Contexte D’un Ensemble de Segments de Texte) software, a program that analyzes textual data in order to identify the essential information contained in a text. On the second step, to confirm the results obtained with Alceste, we read the questions in order to identify the categories the responses might be classified into. Finally, the categories were compared with the data obtained with Alceste, and we found compatible results.

RESULTS

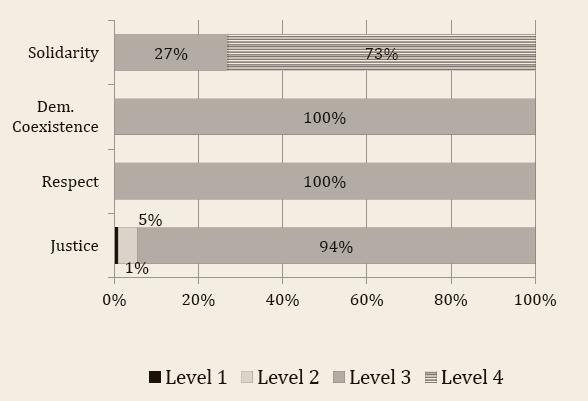

Graph 1 presents the distribution of teachers over the levels in the scales of the four studied values (solidarity, justice, respect and democratic coexistence), which were estimated based on the established cutoff levels, using IRT to process the scale.

Source: Data from the study

GRAPH 1 Distribution of teachers over the levels of adherence to the investigated values

We can see, in Graph 1, that the value for solidarity showed the highest level in the scale (Level 4 - moral perspective for 73% of teachers). At this level, people choose, to a greater extent, solidarity towards the other or towards the group, because they seek equality or the common good, because they are sensitive to the other’s need, or because they share feelings and perspectives. Therefore, adherence to the value occurs due to an inner motivation which predominates over social norms.

Another 27% of teachers adhere to the value of solidarity at Level 3 in the scale, a sociocentric perspective, i.e., one that is centered on group relations and on more conventional social norms. Thus, the study’s data present responses in line with the evaluated value, however, these respondents tend to choose to refer the solution of problems to authorities, or to take actions that meet solely the norms established by social conventions. As to the value of democratic coexistence, 100% of teachers adhered to this value at Level 3, which means that, in seeking solutions for problems involving collective conflicts, the teachers often choose to turn to solutions using rules, regulation, or even resort to the intervention of the authorities in charge of the matter, even if they thought, at some point, about the possibility of considering the participation of all. In these cases, the teachers seek social approval, which is related to being in accord with social conventions.

Regarding the value of respect, 100% of the teachers adhere to it at Level 3. Thus, they try to act in accordance with, and even with obedience to certain laws, rules or authorities. So for them it is a matter of making sure that their actions are in line with social conventions and do not imply consequences that might be unpleasant to themselves or the group.

The predominance of responses at Level 3, both for democratic coexistence and for respect, strongly points to an heteronomous moral tendency, according to Piaget (1977 [1932]) and according to Kohlberg’s (1992) conventional level of moral reasoning, in which the presence of regulators external to the individual, such as norms and the hierarchical pressure arising from the relationship with authorities, guide individuals’ actions.

Finally, concerning justice, the teachers present adherence at the lower levels (1 and 2) in the scale, though in a small proportion. Thus, 1% of them had counter-value stances, i.e., faced with a conflict between students, they tend to act by choosing an expiatory sanction, resorting to authoritarianism. So, exclusion from the class, not listening, involving the family immediately, and lowering the students’ grades without trying to understand the fact were frequent examples of actions that reflect non-adherence to the value of justice on the part of the teacher. At Level 2 in the scale are 5% of the teachers, which means that, faced with an unfair situation, these teachers seek solutions that lead to equal treatment in order to avoid conflicts, due to personal or institutional convenience, or they resort to authority, imposing a solution that is proportional to the infraction. The value for teachers who adhere to the value of justice at Level 3 is 94%, which reflects, again, a sociocentric perspective that is much more oriented towards equality than towards equity in relationships.

Based on the data, there is evidence that it is rather unlikely for teachers to provide a sociomoral environment that is conducive to the development of moral autonomy, since the moral perspective that is most frequent among the respondents, i.e., the sociocentric perspective, is the one that relies on external regulation as elements of coercion for desirable conventional behaviors. Therefore, rare or nonexistent is the constant exercise of reflection and validation of principles that is necessary to the process of self-regulation which characterizes and is indispensable for the development of autonomy. There are strong signs that, in situations where the values of justice, respect and democratic coexistence are concerned, the type of intervention that is most used by teachers reflects a conventional paradigm regarding work on values, in which there is the belief in discursive, normative and punitive effectiveness

It is worth noting that the data presented here, referring to the presence of values and how they are adhered to by the teachers in the municipal education system of Minas Gerais who participated in the survey, reveal a tendency that is very close to data found in studies about the construction and validation of FCC’s scale of sociomoral values. In other words, we found in Tavares et al. (2016) a different progression for each value measured in the 1,315 participant teachers, with the value of solidarity being the one in which teachers were concentrated at Level 4. The values of respect and democratic coexistence revealed 100% of responses at Level 3 (the sociocentric perspective) and, finally, the value with the lowest level of adherence, as regards social perspectives, was justice, with a predominance of responses at Level 3 and 6% of teachers at Level 2, which is adherence from an egocentric perspective.

The results presented in this study showed that the responses of teachers in Minas Gerais are in line with the trend found in FCC’s studies. Regarding the value of justice, in which teachers’ responses were at the first two levels in the scale, the authors note that:

This difficulty in items on justice may be related with the stories being situated in the school, with contents dealing with the use of penalties and school rules for students. In these situations, teachers seldom marked response choices that indicated solutions relying on the values of equality and equity, or even on the employment of sanctions by reciprocity. (TAVARES et al., 2016, p. 205)

In view of the above, the feedback that the SME provided to the schools on the survey’s results consisted in illustrating, by means of examples collected from reality at the units, how the social perspectives that were most frequent in the results translated into everyday situations experienced in the classroom. Encouraging reflection based on real data referring to each educational unit expands the possibility of awareness raising among the unit’s personnel, who usually recognize when there is a contradiction between what they advocate in discourse and how they act. Analyzing results together with the schools strengthens the idea of an education that is centered on the institution’s reality, and generates an immediate intervention regarding reflection about one’s own practice.

As to the open-ended questions, the first of them presents an institutional problem that should be discussed by everyone involved, so they can come to a solution together, thus characterizing a case of democratic coexistence. We consider that democratic coexistence takes place in situations of conflict, dissent or decision-making involving different positions. The solutions or positions taken by the group should be based on dialogue, on cooperative and democratic participation, thereby rejecting solutions made in an authoritarian or submissive way. Thus, in our view, democratic coexistence includes people’s active participation, by means of dialogical exchange, in choices and decisions that affect their social and collective life, as well as in discussing and making rules, norms and laws that regulate them. The question bellow investigates this value:

In a hospital, there are many specialists, but in the last few months, complaints were made because the specialists are failing to detect basic health problems in patients. To solve the situation, the body of practitioners has suggested periodical meetings, however, because their schedules are full due to the hospital’s great demand, the team hasn’t been able to negotiate its meetings. What would you suggest in order to make these meetings happen?

Clearly, there is a problem the specialists need first be aware of, so they can come to the proposition of a solution together. This question was responded by 862 teachers (unit of context). Alceste organized the text into 905 units (text fragments) to process the set of responses. Of these, 854 were selected for analysis, which corresponds to 91% of their use, meaning that the teachers’ statements are homogeneous and can be classified, according to the content of responses, into five different classes, as shown in Chart 2.

CHART 2 Classes of categories and their contents for question 41

| CLASS 3: 31% | ||

|---|---|---|

| The emphasis is on seeking a solution in which everyone can attend and, to that end, they should use as strategy dialogue, negotiation and flexible meeting times. |

“[...] negotiating a time so that everyone can attend.” “[...] presenting choices of time in which everyone can attend.” “I would schedule meetings at alternative times so that everyone can attend.” “Fixing times in three shifts, and so everyone would attend.” |

In this category, the teachers sought to set a time or alternative times so that everyone might attend, through negotiation and dialogue. This position is closer to the concept of democratic coexistence. |

| CLASS 1: 24% | ||

| This class aims at a more operational solution, i.e., teachers are proposing ways of holding meetings so that everyone can be informed of what is happening. |

[...] arranging meetings with small groups at different times, with one person to represent each group and communicate the group’s opinions.” “[...] talking again and proposing small group meetings with the representatives, to share what was discussed” “[...] to reorganize, maybe in smaller groups, and elect representatives to share with the other groups what was discussed.” |

In this class, the concern is that everyone be informed, since not everyone can attend; so there appears the figure of the group representative. Following this order, the possibility of using technology to hold meetings was mentioned in this class. |

| CLASS 2: 15% | ||

| This class presents a solution that is a little less democratic, as it involves voting, i.e., “the opinion of the majority prevails”. |

“I would run a poll to choose the best day and time in which most people in the group could attend.” “Running a poll to find the best day for most specialists, and after the poll, summoning them.” “[...] choosing, by means of an election, the best day for most of the personnel, and holding it. Finding the best way to share with absentees what was decided at the meeting. Then, setting the number of days one can be absent from these meetings.” |

Teachers’ statements indicate some degree of authoritarianism, as can be seen in terms like “summoning”, “number of days one can be absent” and the need for people to be ready to attend as fast as possible, thus reveling a more sociocentric position. |

| CLASS 5: 10% | ||

| There is an authoritarian discourse which places in the hands of the authority the decision on what should be done, when and how. |

“The body of practitioners should schedule the meeting, because if you wait until everyone has time, there will never be a meeting.” “The hospital should find a suitable time that best meets the hospital’s needs, and so the situation is solved.” “The hospital’s senior management should schedule extraordinary meetings, to solve the problem.” |

These responses move away from the concept of democratic coexistence and take on an egocentric position according to which respondents exempt themselves from the responsibility of deciding on the best way to organize the meetings. |

| CLASS 4: 20% | ||

| Here, a counter-value position is taken, with the hospital management being expected to take administrative measures to improve working conditions. |

“Reorganizing the shifts of those working at the hospital.” “Reorganizing the other appointments of the specialists, after all, these meetings are also important to the evolution of medical procedures.” “[....] that these meetings be included in the hospital’s schedule as mandatory.” |

There is an authoritarian position with punitive consequences. |

Source: Data from the study.

From the analysis of the classes above, we can see that most teachers take on a position of democratic coexistence by trying to include everyone (Class 3) or by proposing alternatives that seek to include the majority and to make it possible for those who could not attend to be informed on what was decided and to give their opinion later (Class 1). These positions correspond to 55% of the analyzed text units.

However, 30% of responses reveal egocentric or counter-value positions, exempting themselves from the responsibility and placing it in the hands of the hospital management, scheduling the meetings based on the management’s needs, rewarding attendance at the meetings or hiring new specialists and firing others. This result reinforces the need for the SME to provide specific continuing education, as it denotes, again, a heteronomous tendency in teachers, precisely the ones who should foster the development of children’s and adolescents’ autonomy. The second open-ended question refers to the story of a young man who comes out as a homosexual, being from an extremely traditional and conservative family whose patriarch does not accept any position that counters his costumes. Therefore, it concerns the value of respect, on the assumption that the family should take on a position of embracing and tolerating diversity, particularly in its members.

For this study, respect was defined as recognition of the value of each person considered in their singularity. We highlight mutual respect, which is defined by reciprocity in relationships: the duty to respect is connected to the right to be respected and to demand so (BRASIL, 1998, p. 86). Any action that harms one’s dignity, such as violence, humiliation, exploitation, rejection, manipulation and various forms of discrimination, is to be repudiated.

Pedro is the youngest grandson in a traditional, patriarchal family in which the grandfather gathers everyone each week to make sure the traditional and cultural values are kept. During a talk with his father, Pedro reveals his sexual orientation. Since then, the father wants to avoid the family gatherings as much as possible, precisely because he doesn’t know what to do with this revelation. In your opinion, how should Pedro’s father act?

The question was responded by 854 teachers, thus composing the text to be analyzed. Alceste subdivided the set of responses into 884 text fragments to be analyzed. Of the set of these fragments, the program considered for analysis 780 sentences formed by the vocabulary that stood out in the text. These sentences correspond to 89% of the use of the set of responses, thus revealing that the teachers’ statements are homogeneous and can be classified, according to their contents, into four distinct classes, which are organized in Chart 3.

CHART 3 Classes of categories and their contents for question 42

| CLASS 3: 27% | ||

|---|---|---|

| In this class, responses emphasize total support to the son, respecting his opinion and seeking comprehension and respect from the family towards his son. |

“He should support his son and try to open the dialogue in the family so his son can be understood and embraced.” “He should respect his son’s sexual orientation and talk to the whole family so that they do the same.” “He should listen to his son, support him and bring the case to the family. He should ask for comprehension and provide a family environment to receive him.” |

Classes 3 and 4 show similar responses;

in both, the teachers are in favor of support to the son and of disclosure to the family,

based on dialogue. Class 3, with 27%, and Class 4, with 17% of the sentences, correspond to the majority of teachers’ responses - 44%. Together, these two classes indicate a moral stance by the father regarding the value of respect, since he deals with the situation by showing unconditional support to his son, without avoidance regarding the family, and he tries, through dialogue, to get their comprehension and respect. |

| CLASS 4: 17% | ||

| Responses stress dialogue with the family, so that they understand and accept his son. |

“He should seek help with the other family members, in order to define the best way to talk to the grandfather about the subject, thus ensuring family union, truth and respect for the grandson’s orientation.” “He should create an opportunity for a talk, at one of the family gatherings, about the importance of tolerance, of respect, about the new family concepts, the positive change in society and, when the moment is right, reveal his son’s sexual orientation.” “Hiding the fact will not change things, I would try to dialogue with the family.” “The father should reveal to the grandfather his son’s sexual orientation, and, together with Pedro, they should decide on the best way to tell the rest of the family about it, without prejudice or exclusion.” |

|

| CLASS 2: 38% | ||

| These teachers’ statements recommend that the father should continue to go to the family gatherings, without taking any action, however, the justification for this option is divided in two distinct positions: the first emphasizes the need to respect the son and take no action until he says he is ready for this revelation; the second corresponds to acting naturally and letting the family notice it by and by, and only then should the father take action. | a) He should respect his son and say something only when his son is feeling ready to assert his position to the family: “He should keep the family gatherings and respect his son’s orientation, and leave up to him the best moment for disclosure.” “Father and son should talk and ponder whether they should tell, because Pedro has to be comfortable enough, but they should not stop going to the family gatherings, because this is a subject that doesn’t have to be exposed or justified.” “The gatherings must be kept, and it is Pedro who should reveal it, if he wants to, to the family, when the moment is right. They should go to the gatherings, he should do nothing about it and should not expose his son, and respect Pedro’s will regarding when to expose himself.” b) He should do nothing and let things go naturally: “He should keep the family gatherings, and so everyone will gradually see Pedro’s sexual orientation, and he won’t have to reveal it.” “He should act naturally and let the family see it by themselves.” “There is no need to avoid the family gatherings or say anything, unless he is asked, then tell the truth.” “He should act naturally, say nothing, because this is more and more common.” |

In Class 2, there are sentences indicating two different positions regarding adherence to the value of respect: the first represents a moral position, for although he was told by his son, he should respect him and say something only when Pedro is felling strong and sure he wants to tell the family. The second reveals a position of personal comfort (an egocentric position), as it is better for him to do nothing and avoid unnecessary trouble at the moment. |

| CLASS 1: 18% | ||

| This class corresponds to seeking professional help. As with Class 2, we observe two distinct positions, one that is more positive and the other showing difficulty dealing with this subject. |

a) Seeking help to support him on the best way to act: “He should seek even professional help and guidance to find the best way to solve the situation, together with his son.” “He should turn to a psychologist for professional help to find some guidance on how to deal with this situation, so as to harmonize the relationship between family members.” “[...] he should face the situation and stand by his son, seeking psychological help to find a way to impart this information to the other people in the family, without further harm as possible.” b) Seeking help to be able to understand his son and assert his position to the family: “He should find a support group to talk about it and start to internalize the fact, in order to gradually accept it, as it is new to him, and he also needs time.” “He should find a psychologist that can help him accept this situation.” “This situation is very difficult, he should rely on the church and really ask God to do the best.” |

This class reveals, on the part of teachers, some difficulty dealing with the subject, since while accepting the son’s position, the father needs external help, thus relying on authority (an egocentric position). However, it also shows their difficulty accepting the son’s revelation, thus indicating a similar position to that of the family (a counter-value position). |

Source: Data from the study.

The responses to the open-ended questions show that most teachers take positions at Level 4. However, we also found an important proportion of teachers who take positions at Levels 3 (sociocentric), 2 (egocentric) and 1 (counter-value). Therefore, we find it important to develop collective work that might contribute to exchanging information, so that, through debate, these teachers might review their way of thinking and acting.

Study of the relationship between adherence to sociomoral values and teachers’ profile and context

This stage of the study sought to examine the relationship between the profile and context of the teachers participating in the study and the modes of adherence to the analyzed values. The variables for profile and for context were surveyed by means of questions about the topics below.

CHART 4 Variables for context and profile included in the teacher questionnaire

| VARIABLES | INDICATORS |

|---|---|

| Personal characteristics | Sex; age; religion; working condition |

| Family relation | Family composition; complete family (father, mother, siblings); incomplete family (father or mother and sibling); does not live with the family |

| Rules on family life | Punishment; authority; contract; support |

| Socioeconomic status | Education of the person who supports the family; consumption goods |

| Relationship with the school | Whether the person has failed grades, likes the school and likes to attend classes; how they are treated by the teacher |

| Self esteem | How does the person feel that people see them at school, in family and among friends |

| School coexistence situations | Mistreatment on the part of peers and teachers |

| Internet use | Researching; reading news; participating in social networks |

Source: Data from the study.

In order to investigate the relationship between the profile and context variables and the modes of adherence to values, we used AID (Automatic Iteration Detector). This method produces classification trees based on tests of association between variables, and it divides the set of data into mutually exclusive subsets. In other words, based on the score obtained for adherence to the investigated value (dependent variable), according to the predictive variables (of profile or of context), the investigated group is divided into two or more statistically distinct groups. Then, these groups are successively divided into smaller subgroups. The division of groups ceases when there are no more predictive variables to produce significant segments.

In this study, for each investigated value, a classification tree was processed. It should be noted that this is an exploratory study whose results are estimates indicating a tendency towards greater or smaller adherence to the values, not causal relationships. The study underscores points that should be observed in school’s everyday life.

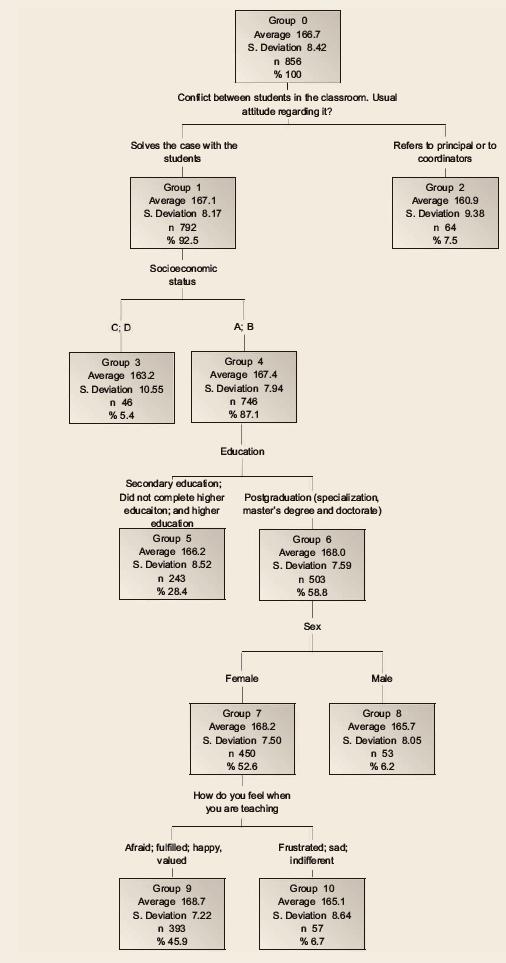

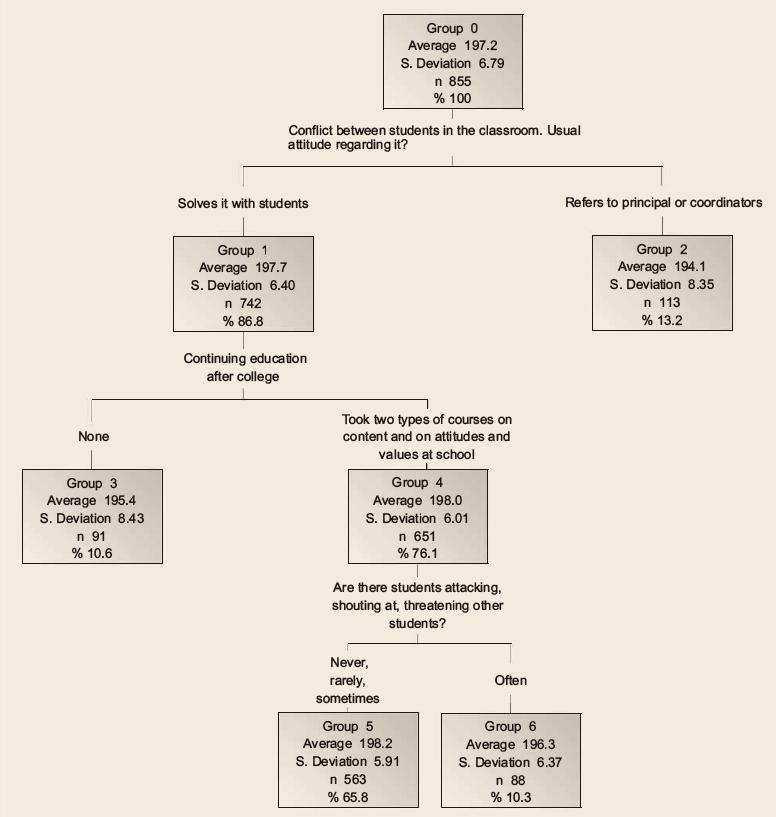

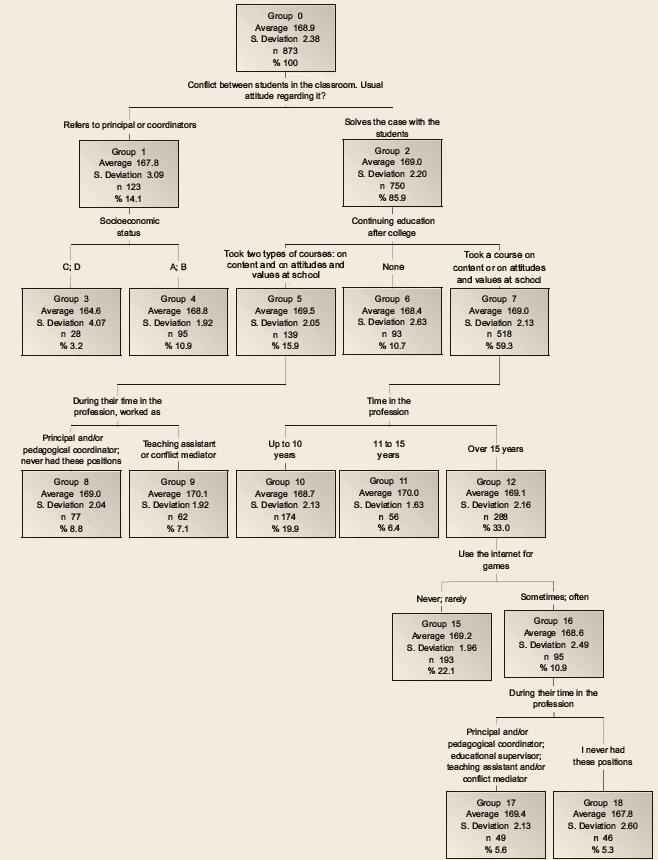

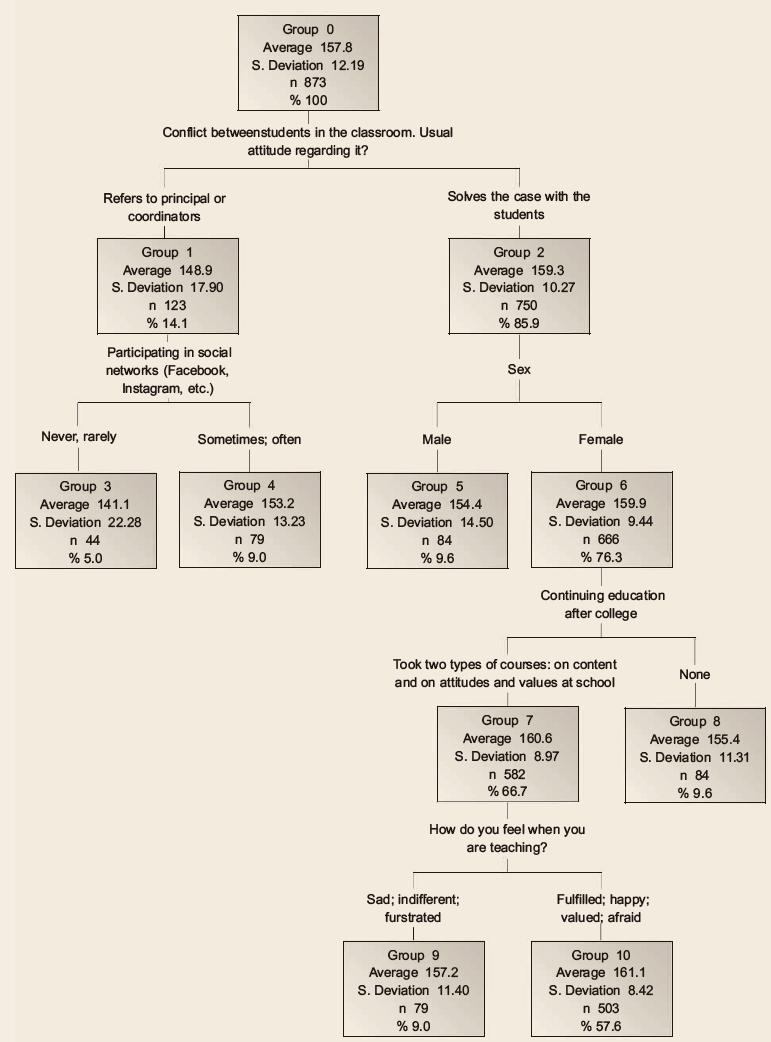

The figures below present the classification trees for the values of solidarity, democratic coexistence, respect and justice.

Source: Data from the study.

FIGURE 1 Teacher classification tree regarding adherence to the value of solidarity, according to the profile and context variables

As observed in all classification trees studied here, the variable that predominates regarding the teachers’ adherence to the value of solidarity refers to their attitude when conflicts happen in the classroom. Thus, when the teacher solves the conflict in the classroom, adherence to the value of solidarity tends to be greater (group 1, average 167.1; 92.5% of teachers) than when his attitude is rather punitive and he refers the matter to the school principal or to the coordinators (group 2: average 160.9; 7.5% of teachers). This punitive attitude indicates a smaller score regarding adherence to the value of solidarity; it is worth stressing that this is the smallest group, with only 7.5% of the teachers.

The greatest score for adherence to the value of solidarity was found for teachers who, in addition to solving the cases in the classroom (group 1: average 167.1; 92.5% of teachers), belong to socioeconomic levels A and B (group 4: average 167.4, 87.1% of teachers), hold a postgraduate diploma corresponding to a specialization, a master’s or a doctoral degree (group 6: average 168; 58.8% of teachers), are female (group 7: average 168.2; 52.6% of teachers), and feel fulfilled, valued, happy and afraid (group 9: average 168.7; 45.9% of teachers). Feeling afraid may reveal a position of caution about their work, of being careful about the consequences of their actions.

Source: Data from the study.

FIGURE 2 Teacher classification tree regarding adherence to the value of democratic coexistence, according to the profile and context variables

As with the solidarity adherence tree, the variable that divides the group concerns how teachers act when situations of conflict occur in the classroom. Therefore, when the teacher solves the conflict in the classroom, adherence to the value of democratic coexistence tends to be greater (group 1: average 167.6; 86% of teachers) than when he has a rather punitive attitude and refers the matter to the school principal or to the coordinators or supervisors (group 2: average 194.2; 13.2% of teachers). This punitive attitude reveals a tendency towards a smaller score for adherence to the value of democratic coexistence; it is worth underscoring that this is the smallest group, with only 13.2% of teachers.

The group of teachers with greatest adherence to the value of democratic coexistence has the following characteristics: when conflicts occur in the classroom, they tend to solve them in the classroom with the students (group 1: average 197.6; 86% of teachers); they correspond to those who, in their continuing teacher education, attended refresher courses in the discipline they teach and/or courses related to mediation in the school environment or to sociomoral values (group 4: average 197.9; 76.1% of teachers), and who have never or rarely noticed other students shouting at or threatening their peers (group 5: average 198.2; 65.8% of teachers).

Source: Data from the study.

FIGURE 3 Teacher classification tree regarding adherence to the value of respect, according to the profile and context variables

The predominant variable among the ones that characterize teachers’ profile and context regarding adherence to the value of respect refer to their attitude when conflicts occur in the classroom. Thus, we observe that when the teacher solves the conflict in the classroom, adherence to the value of respect tends to be greater (group 2: average 169; 85. 9% of teachers) then when he takes a rather punitive attitude and refers the matter to the principal or to the coordinators or supervisors (group 1: 167.8; 14.1% of teachers).

The characteristics of teachers who show the smallest adherence to the value of respect mean that, in conflict situations, the teacher tends to refer the students to the principal (group 1: average 167.8; 14.1% of teachers) and whose socioeconomic status corresponds to levels C and D (group 3: average 164,6; 3,2% of teachers). However, we found that this group is very small and hardly representative of the teachers in the municipality.

Likewise, the group that shows greatest adherence to the value of respect corresponds to the teachers who try to solve the conflict in the classroom (group 2: 169; 85.9% of teachers). Of this group, we highlight two profiles with greater adherence. The first profile corresponds to teachers who, in their continuing education, attended refresher courses in the discipline they teach, and also courses on topics related to mediation in the school environment or to sociomoral values (group 5: 169.5; 15.9% of teachers), and who, during their time in the profession, worked as a teaching assistant and/or a conflict mediator (group 9: average 170.1; 7.1% of teachers). The other profile corresponds to the teachers who, in their continuing education, attended refresher courses in the discipline they teach or courses on topics related to mediation in the school environment or to sociomoral values (group 7: average 169; 59.3% of teachers) and have been teaching for 11-15 years (group 11: average 170; 6.4% of teachers).

Another group that stands out in adherence to the value of respect is that of the teachers who have been in the profession for a long time (group 12: over 15 years), use the internet for games (Group 16: average 168,6; 10.9% of teachers) and have previously worked as principals or coordinators/supervisors or as teaching assistants/mediators (group 17: average 169.4; 5.6% of teachers).

Source: Data from the study.

FIGURE 4 Teacher classification tree regarding adherence to the value of justice, according to the profile and context variables

As seen earlier, the profile variable regarding how the teachers manage conflicts that arise in the classroom divides the group between teachers who solve the conflict cases with students in the classroom, indicating a greater score for adherence to the value of justice (group 2: average 159.3; 85.9% of teachers) compared to the other group, which refers conflict cases to the principal or to the coordinators (group 1: average 148.9; 14.1% of teachers).

The characteristics of teachers with smallest adherence to the value of justice correspond to the variables for which, in conflict situations, the teacher tends to refer the students to the principal (group 1: average 148.9; 14.1% of teachers); teachers in this group never or rarely participate in social networks such as Facebook, Instagram etc. (group 3: average 141,1; 5% of teachers). Indeed, we found that this group is very small and hardly representative of teachers in the municipality.

As to the variables that characterize the groups that adhere most to the value of justice, we highlight the following: the teachers who solve the conflicts in the classroom with students (group 2: average 159.3; 85.9% of teachers) are female (group 6: average 159.9; 76.3% of teachers); in their continuing education, they attended refresher courses on the content of the subject they teach, and they also attended courses on topics related to mediation in the school environment and on values (group 7: average 160.6; 66.7% of teachers), and finally, when they are teaching, they feel happy, valued, fulfilled and afraid (group 10: average 161.1; 57.6% of teachers). Feeling afraid may, in fact, reveal a position of caution regarding their work, of being careful about the consequences of their actions.

In sum, for this group of teachers, the variables that contributed most to a greater or smaller adherence to the values are in Charts 5 and 6 below.

CHART 5 Variables and categories of profile and context for teachers who formed the groups with smaller adhesion to the values

| VARIABLE | CATEGORY | SOLIDARITY | DEMOCRATIC COEXISTENCE | RESPECT | JUSTICE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile | Socioeconomic levels C and D | X | |||

| Never or rarely participate in social networks like Facebook, Instagram, etc. | X | ||||

| Conduct | Faced with problems in the classroom, they solve them by referring students to the principal or to the supervisors | X | X | X | X |

Source: Data from the study.

For the teachers in the municipality, the variable that seems to negatively impact adherence to the sociomoral values studied here corresponds to conduct in the classroom. The other variables regarding profile do not seem as strong as this one.

CHART 6 Variables and categories of profile and context for teachers who formed the groups with greater adhesion to the values

| VARIABLE | CATEGORY | SOLIDARITY | DEMOCRATIC COEXISTENCE | RESPECT | JUSTICE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile | Female | X | |||

| Socioeconomic levels A and B | X | X | |||

| Conduct | Faced with problems in the classroom, they solve them in the classroom with the students | X | X | X | X |

| Professional environment | When teaching, they feel fulfilled, values, happy and also afraid | X | X | ||

| They observe very few students shouting at and threatening peers | X | ||||

| Teacher education | Postgraduation diploma (master’s/doctoral degree) | X | |||

| Continuing education: courses on the contents of the subject they teach and/or on acting with students regarding attitudes and sociomoral values | X | X | X | ||

| Professional experience | Have previously worked as a teaching assistant and a teacher-mediator | X | |||

| Have been teaching for 11-15 years | X |

Source: Data from the study.

According to Chart 6, we can infer that the variables that stand out regarding greater adherence to the values are:

Teacher conduct: the teachers who solve classroom problems with their students tend to present adherence to the four values at higher levels.

Teacher education: the teachers who continue their education through graduate studies or through continuing teacher education courses also tend to present greater adherence to the four values.

Work environment: we found that the teachers who feel valued and/or work in environments where they get more respect from students tend to achieve higher scores for adherence to the values of solidarity, democratic coexistence and justice.

In general, we highlight the sex variable, which, in all studies we conducted, indicate that women tend to express a higher level of adherence to the values than men, perhaps due to the role they play in society and to the way they are raised, which is oriented to the care of children, family, etc.

As to the variables for teachers’ context and profile that stood out regarding the likelihood of better adhere to the values above, we emphasize teachers’ attitude in solving conflicts. In other words, we found that when the teacher solves the conflict in the classroom, adherence to all these values tends to be greater than when his attitude is more punitive, referring the case to the principal or to the coordinators. We also found that the teachers who attend refresher courses on the discipline they teach and courses on topics related to attitudes and sociomoral values in the school environment tend to adhere more positively to the values of democratic coexistence, respect and justice. And finally, teachers who feel fulfilled, valued and happy about their work tend to show better adherence to the values of solidarity and justice.

CONCLUSIONS

Considering these results, we can conclude that the teachers tended to the sociocentric perspective regarding adherence to three of the studied values. In general, these results indicate a strong rule-based tendency in their responses, a tendency attached to social conventions and to the politically correct. Therefore, in planning its educational policies, the SME should commit to a challenge and a necessity: systematizing training actions for school personnel regarding an education in line with values that help build more ethical human relations. Only for the value of solidarity did teachers show a moral perspective (73%), i.e., when a value is adhered to because of a motivation that is above social norms and that lies in the recognition of the dignity of each human being. In this respect, we might say that individuals tend to moral autonomy: they adhere to values they recognize by themselves as being good both for themselves and for anybody else.

The construction of fairer, more respectful relationships and of the sociomoral values embedded in them is no doubt an important goal for education. If we want an education that is complete, that considers the individual as a whole, which means considering his cognitive, affective, social and moral aspects, then it is necessary to encompass education on moral values. The school, in the dynamic of pedagogical actions, in the relationships established in the school environment, constitutes a place that is conducive to this development. Values are constantly present in the actions taking place in the school, and depending on the quality of the interactions established in this environment, we can optimize education on moral and ethical values. It is in this environment that the individual will live with the public sphere (in the sense of the collective world), establish equal relationships and live with diversity.

We saw, from the results, that teachers have a normative practice, and this shows how much they are still attached to social norms, particularly regarding the values of justice, respect and democratic coexistence, which are the hardest ones for teachers to adhere to at Level 4. This allows us to affirm that there is a real need for continuing education courses that emphasize this topic, in order to allow education personnel to reflect about their own values. Understanding these studies contributes to the process of collective transformation and helps raise awareness about the construction of fairer, more respectful relationships. It is therefore in the school’s everyday life, in the relationship with the other, that teachers should develop an interaction in the classroom and in the school space as a whole so as to promote a positive and ethical school climate in the coexistence between them and their students, and among the students themselves; in this way, the school declares and shows its social role as an institution that is responsible for educating subjects committed to the collective world, where equity is truly a reality.

REFERENCES

ARAÚJO, E.; ANDRADE, D.; BORTOLOTTI, S. Teoria da Resposta ao Item. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, v. 43, n. especial, dez. 2009. [ Links ]

BAUMAN, Z. O mal-estar da pós-modernidade. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1998. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Fundamental. Parâmetros curriculares nacionais. Brasília: MEC, 1998. [ Links ]

KOHLBERG, L. Essayson moral development: The Philosophyof moral development: moral stagesandtheideaof justice. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1981. v. 1. [ Links ]

KOHLBERG, L. Psicología del desarrollo moral. Bilbau: Biblioteca de Psicologia, Desclée de Brouwer, 1992. [ Links ]

LIPOVETSKY, G. O crepúsculo do dever: a ética indolor dos novos tempos democráticos. 4. ed. Lisboa: Dom Quixote, 2010. [ Links ]

MARQUES, C. A. E.; TAVARES, M. R.; MENIN, M. S. S. Valores sociomorais. Americana, SP: Adonis, 2019. [ Links ]

PIAGET, J. O julgamento moral na criança. São Paulo: Mestre Jou, 1977 [1932]. [ Links ]

PIAGET, J. El psicoanálisis y sus relaciones com lapsicología del niño. In: DELAHANTY, G. P. (comp.). Piaget y elpsicoanálisis. México: Universidade Autônoma Metropolitana, 1994 [1920]. p. 181-290. [ Links ]

TAVARES, M. R.; MENIN, M. S. S. (coord.). Avaliando valores em escolares e seus professores: proposta de construção de uma escala. São Paulo: FCC/DPE, 2015. (Textos FCC, 46). [ Links ]

TAVARES, M. R.; MENIN, M. S. S.; BATAGLIA, P. U. R.; VINHA, T. P.; TOGNETTA, L. R. P.; MARTINS, R. A.; MORO, A. Construção e validação de uma escala de valores sociomorais. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 46, n. 159, p. 186-210, jan./mar. 2016. [ Links ]

1“How people see others, interpret their thoughts and feelings and the role they play and the place the occupy in society” (KOHLBERG, 1992, p. 195).

Received: July 12, 2020; Accepted: September 24, 2021

texto em

texto em