1 Introduction

The post-World War II world has been characterized by the growing emphasis given to scientific and technological research as a powerful strategic resource and an important ally for the promotion of economic development ( MOREIRA; VELHO, 2008 ). Here in Brazil, the first National Graduate Degrees Plan – PNPG, which was drawn up in 1974, already showed an alignment with the international trend of subordinating graduate degrees policies to the needs of national development through the training of researchers and professionals in high level ( BRASIL, 2004 ). Since the 1970s, the Federal Government has been making efforts on granting scholarships, including those ones abroad, as one of the ways to train researchers and professionals Brazil needs. In 1974, for example, it was estimated that there were around 1,400 graduate students (master’s and doctorate) abroad ( BALBACHEVSKY, 2005 ; BRASIL, 2004 ).

As one of the results of policies implemented to the graduate programs, Brazil experienced a strong expansion of its graduate degrees system (CIRANI; CAMPANARIO; SILVA, 2015).Even so, that did not mean a path without conflicts or a threatening moment to the development of Brazilian science and its graduate degrees system. It is necessary to recognize the strong resistance that research associations, researchers and Graduate Programs have exercised in the face of constant - but not always beneficial - changes in policies in the scientific and educational area in Brazil.

The scenario set by Graduate degrees policies in Brazil is perfectly in line with the training needs in a country which has not had a consolidated university system yet. Furthermore, the possibility of studying at foreign universities for at least one period tended to favor the development of partnerships and, therefore, increase scientific cooperation. This is the scenario in which we set ourselves the objective of understanding how investment in Graduate scholarships for studies abroad has been carried out in the field of Education.

The Education area plays a crucial role in teacher training policies and the production of scientific knowledge to face the persistent and big challenges in Brazilian Education. This area position itself justifies the need for a more accurate look at the vicissitudes and idiosyncrasies which the Education area goes through in the context of the internationalization of higher Education.

In Brazil and Latin American countries during the late 1990s, those responsible for Educationbegan to remodel the objectives of undergraduate and graduate courses so that they could be competitive on the international scene. This remodeling was carried out based on research in the area that contributed in a theoretical and practical way to undergraduate and graduate courses in Education (GATTI et al ., 2019); taking into account the sociocultural and political specificities of the several institutions in Brazil.

Since universities have been aware of these changes in course objectives and their demands, they have been carrying out actions and partnerships to expand the internationalization of their research (FINARDI; SANTOS; GUIMARÃES, 2016). However, the dissemination of studies aligned with the need of a region’s social issues comes up against the predominance of the English language. Countries whose most population is English-speaking can have greater access to research and international discussions; consequently, countries which use other languages predominantly have had less reach and taken less part in discussions and actions for the internationalization of research (FINARDI; SANTOS; GUIMARÃES, 2016). On the other hand, due to the wide use of the Portuguese and Spanish languages in several countries of the Global South, mainly because of their colonial past, South-South partnerships in the scope of Higher Education are facilitated through the use of these languages.

This historical approach leads us to a concept of Internationalization of Higher Education whose goal is to promote economic and technological development based on intercultural training beyond borders and strengthening local social insertion ( MOROSINI, 2019 ) aimed at intercultural skills. The author also presents that Internationalization can be carried out in 4 formats: Integral, Curricular, Outgoing and at Home.

Possible actions can be mentioned, such as the Curriculum Internationalization, Internationalization at Home (IaH), English as a Medium Instruction (EMI), Collaborative Online International Learning (Coil) Outgoing and the Exchange (incoming), in addition to Diploma in Co-tutoring Regime, Cooperation Agreements between Higher Education Institutions, Network Research Projects, publications in a foreign language, among others. Furthermore, there are other actions, for instance: i) promoting domestic internationalization among researchers; ii) encouraging teachers’ training and performance across countries; iii) implementing internationalization policies in Higher Education in medium and long term ( MOROSINI, 2017 ).

The Internationalization of Higher Education is an issue discussed in different environments and from different perspectives, including international relations. Since 1969, the American Convention on Human Rights (also called the Pact of San José, Costa Rica),whose chapter 3deals with Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, states in its article 26 that for progressive development, it is necessary that the States develop actions “through international cooperation, especially economic and technical, in order to progressively achieve the full effectiveness of the rights arising from economic, social and educational, scientific and cultural norms [...]”. Accordingly, in 1988, the Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the field of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (known as the Protocol of San Salvador) describes in its article 13 that regarding the Right to Education“1. Every person has right to Education” and that “3. States [...] recognize that [...]: c. Higher Education must be made equally accessible to all, according to their ability, by whatever means are available and, especially, by the progressive implantation of free Education”.

The World Education Forum (2015) organized the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals for Education (SDG4) with the Incheon Declaration of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization ( UNESCO, 2016 ). Despite being a declaration, this soft law had the participation of 120 ministers from over 160 countries present, as well as several people involved and interested in quality Educationfor all.

In the Incheon Declaration, it was discussed ( UNESCO, 2016 , p. 7) that in the next 15 years Education would need actions to achieve the vision of SDG4 “to ensure inclusive and equitable quality Education, and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. Still in this Declaration, our attention is drawn to the last two goals (4b and 4c), which are about “[...] expanding considerably the number of scholarships available to developing countries in the world [...]” and “[...] increasing the contingent of qualified teachers, including through international cooperation for teacher training, in developing countries [...]”. It is important to consider the inequalities in investment which occur in the Brazilian context between the different regions of the country ( COSTA; CANEN, 2022 ), thus limiting opportunities and accentuating differences in the national development of Higher Education.

In international relations, the importance of geographic or political spaces lies in the economic potential that can be generated ( CHANG, 2003 ). In the case of Unesco and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Brazilian foreign policy has been strongly inserted, mainly with a Permanent Diplomatic Delegation to Unesco since 1958 ( BRASIL, 1958 ) and, more recently, with the aim to intensify its relations to be accepted into the OECD through closeness with the US government ( EMBAIXADA E CONSULADOS DOS EUA NO BRASIL, 2022 ).

To meet the challenges of quality Educationfor all, Brazil has participated in international assessments in both Basic and Higher Education. Its results still do not correspond to the 9th economy in the world ( BRASIL, 2021 ); it is among the last in the Pisa ranking ( BRASIL, 2019 ) and has no universities among the 100 best in the world. It also has the 87th HDI ( PNUD, 2022 ). It is important to consider what other nations do and what can inspire the adaptation to Brazilian economic and cultural context, as well as how we can improve the qualification of our professionals.

In particular, this study aims to investigate the area of Education (one of the 49 areas of Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel– Capes evaluation) through a description and comparison of the distribution of Capes scholarships abroad, considering the international partner programs, the destinations of these scholarship holders by macro-regions (Latin America, North America, Africa, Asia, Europe and Oceania) and by important economic blocs/forums for Brazilian foreign policy, such as the Southern Common Market (Mercosur), Brics, North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta) and European Community.

Thereby, based on data from the results about the main destinations of Capes scholarship holders and the most present languages in these actions regarding Education field, we will be able to discuss their possible impacts on Brazilian society to contribute to additional reflections on improving research funding and international cooperation.

Therefore, the general objective of this study was to analyze the Internationalization of Higher Education in Brazil through the distribution of scholarships abroad in Education by Capes from 1998 to 2020.

The following sections of the article will present that the study was carried out through a quantitative analysis of the Brazilian case of sending scholarship holders abroad with data collected from 1998 to 2020. The data show an increase over the 2010s, with emphasis on Science Without Borders and with strong insertion in the countries of the Global North. In the end, we discuss the results from the perspective that the internationalization of Higher Educationin Brazil still has difficulties with national valuation policies, as well as the need for better positioning and protagonism with Latin America and Africa.

2 Methods

The research was a case study with a quantitative approach ( SPRINZ; WOLINSKY, 2002 ), with data on the number of scholarships awarded by internationalization programs linked to Capes, the main research promotion agency in Brazil for graduate training.

Data on the distribution of Capes scholarships in the area of Education (area of policy and evaluation of graduate Studies in Brazil) were analyzed considering the following variables: Year, Country of destination, Institution of Higher Education, Predominant language of the institution, Macro-region and Economic Block. Data were collected from the Capes Georeferenced Information System (Geocapes) available at https://geocapes.capes.gov.br/geocapes/ and are freely accessible (BRASIL, 2022). The variables that were not collected by the Geocapes system and that were attributed are “Predominant language of the institution, Macro-region and Economic Block”, because, for the purposes of this study, such information becomes fundamental for a better understanding of the destination of the scholarships.

Regarding the analysis by blocks or economic forums, each country in the organized sample was included in only one block/forum that would be of higher interest for discussion in the study. Therefore, the 4 (four) countries which are part of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) were inserted in this study in other groups: United States and Canada were counted only in Nafta; Russia and China in Brics. In addition, it should be noted that the United Kingdom was still considered as part of the European Union, since the data refer to a period in which that country was still part of the bloc. Portugal was only considered as part of the European Union, and not in the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP).

Data analysis took place in two procedures considering: 1) total data from Capes scholarship holders with possible repetition over the years; and 2) data without repetition of scholarship holder in the modality (every 5 years). Most of the quantitative data were analyzed in the second procedure, since due to the way data are made available on the Geocapes website, it is not possible to identify whether a scholarship holder in one year is the same or not in the following year. Considering the georeferencing presented on the Geocapes website represents a portrait of scholarship holders abroad in each year, we can infer that this is data that repeats from one year to the next, especially if we consider, for example, that the European academic calendar starts in September and a scientific stage scholarship holder (known as doctoral sandwich in Brazil) who had 6 months of grant will be counted in the year of implementation of the scholarship and in the year of return. Therefore, in the same way, the longest period of scholarship of a modality that is the full doctorate (48 years), it is possible that this scholarship holder appears in the data in 5 years in a row.

For the second procedure, we used an adaptation of the “systematic selection of sample elements” (SAMPIERI; COLLADO; LUCIO, 2013) to carry out a longitudinal analysis of the 23 sample events (23 years of collection) without data repetition. For this, being k=N/n where k is the interval (5 years) and N the event number (23). As the first year of available data is 1998 and this study seeks to observe the insertion of scholarship holders from Capes over the years, it was appropriate to analyze the first sampling year event as 1998 and the remaining 4 samples every 5 years. We also present the most recent data available on Geocapes, which, it should be emphasized, may present the repetition of data from 8 full doctoral scholarship holders who were abroad in 2020 and it is not possible to identify when they started their activities, due to the way they are available on Geocapes. Still according to data from Geocapes, in 2020, no full master’s scholarship was observed abroad, another possible group of repetition of data from 2018 and 2020. Therefore, data from years 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, 2018 and 2020 were analyzed.

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics using SPSS 20.0 software. As for ethical aspects, this research followed the norms established in Resolution No. 510/16 of the National Health Council pursuant to Art. 1, item V that explains that “research with databases, whose information is aggregated, without the possibility of individual identification” does not require submission to an Ethics Committee ( BRASIL, 2016 ).

3 Results

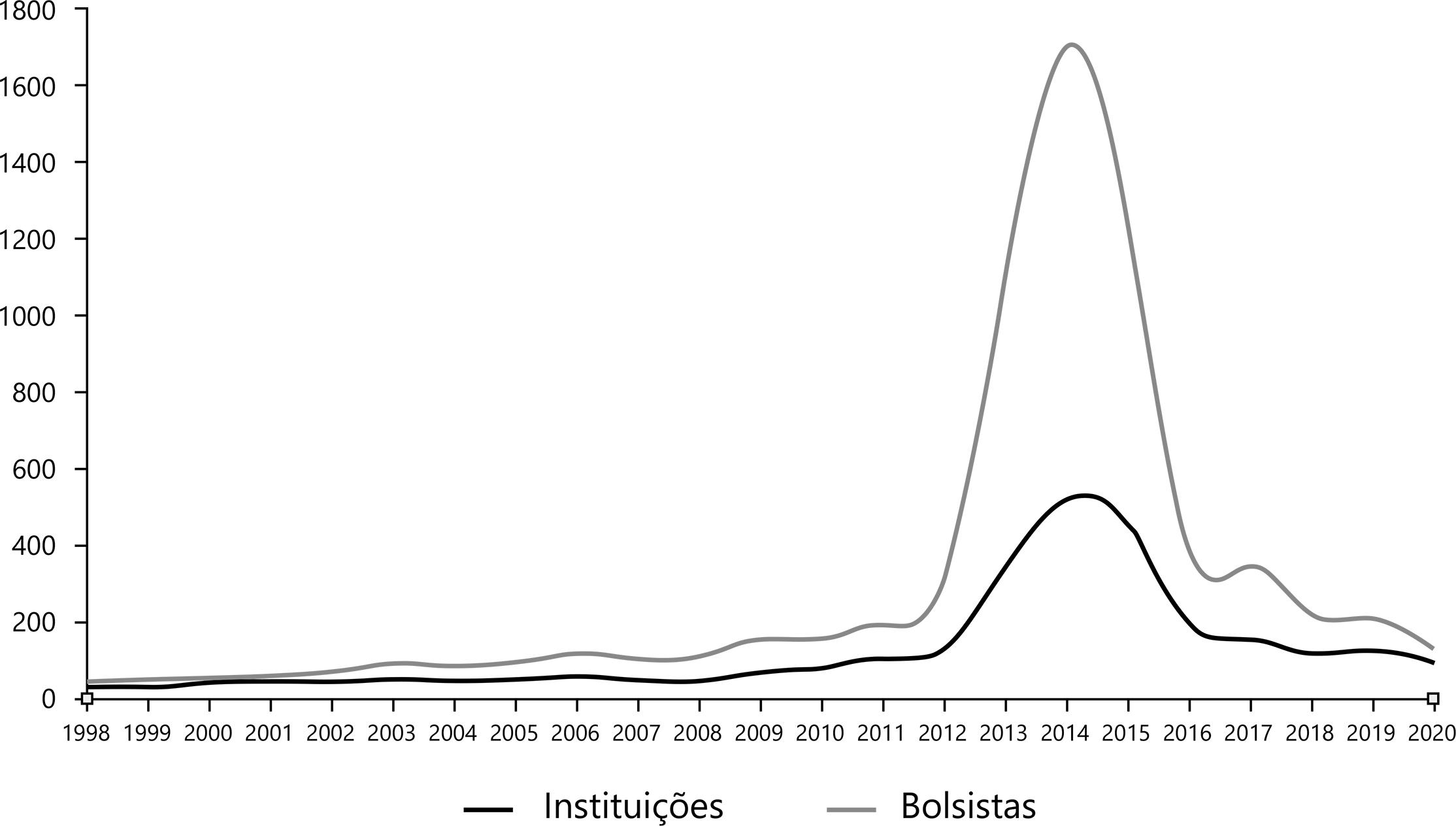

In Table 1 , we can see the number of institutions abroad receiving Capes scholarship holders each year:in 1998 there were 33 institutions and 46 scholarship holders, and in 2014 reached the top numbers, with 518 institutions and 1,705 scholarship holders. Also, the years with no repetition of scholarship holders in the same type of scholarship have been highlighted in Table 1 and a growth can be seen both in the number of institutions and in the number of scholarship holders.

Table 1 Number of institutions and scholars abroad in each year

| Year | Numberofinstitutions | Number of scholars abroad in each year |

|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 33 | 46 |

| 1999 | 33 | 52 |

| 2000 | 43 | 57 |

| 2001 | 47 | 62 |

| 2002 | 46 | 73 |

| 2003 | 51 | 93 |

| 2004 | 49 | 88 |

| 2005 | 53 | 97 |

| 2006 | 59 | 118 |

| 2007 | 50 | 106 |

| 2008 | 49 | 112 |

| 2009 | 70 | 157 |

| 2010 | 83 | 160 |

| 2011 | 105 | 195 |

| 2012 | 132 | 315 |

| 2013 | 342 | 1,100 |

| 2014 | 518 | 1,705 |

| 2015 | 461 | 1,244 |

| 2016 | 199 | 399 |

| 2017 | 153 | 346 |

| 2018 | 120 | 226 |

| 2019 | 125 | 209 |

| 2020 | 95 | 131 |

Source: Data from GeoCapes (BRASIL, 2022)

Graph 1 visually shows the growth in the number of institutions and scholarship holders abroad over the years 1998 to 2020, with an important turning point in the year 2011 to 2012, the period of implementation of the Science Without Borders Program, by the first Dilma Government.

Source: Data from GeoCapes (BRASIL, 2022)

Graph 1 Number of foreign institutions and scholars abroad between 1998 and 2020

Analyzing the continents which received the most scholarship holders, we observed that Europe has always been ahead and North America in second place. Only in the 2013 and 2018 data (based on the research method used), we identified that the other continents received several scholarship holders, but that in 2020 Africa and Central America did not have any scholarship holders.

Table 2 Continent and its highest number of scholars in every 5 years and 2020

| 1998 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | 2018 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 65 | 9 | 0 | |||

| CentralAmerica | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||

| North America | 12 | 18 | 11 | 314 | 48 | 25 |

| South America | 1 | 1 | 3 | 24 | 11 | 5 |

| Asia | 23 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Eurasia | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Europe | 33 | 74 | 98 | 538 | 151 | 96 |

| Oceania | 134 | 4 | 1 |

Source: data from GeoCapes (BRASIL, 2022)

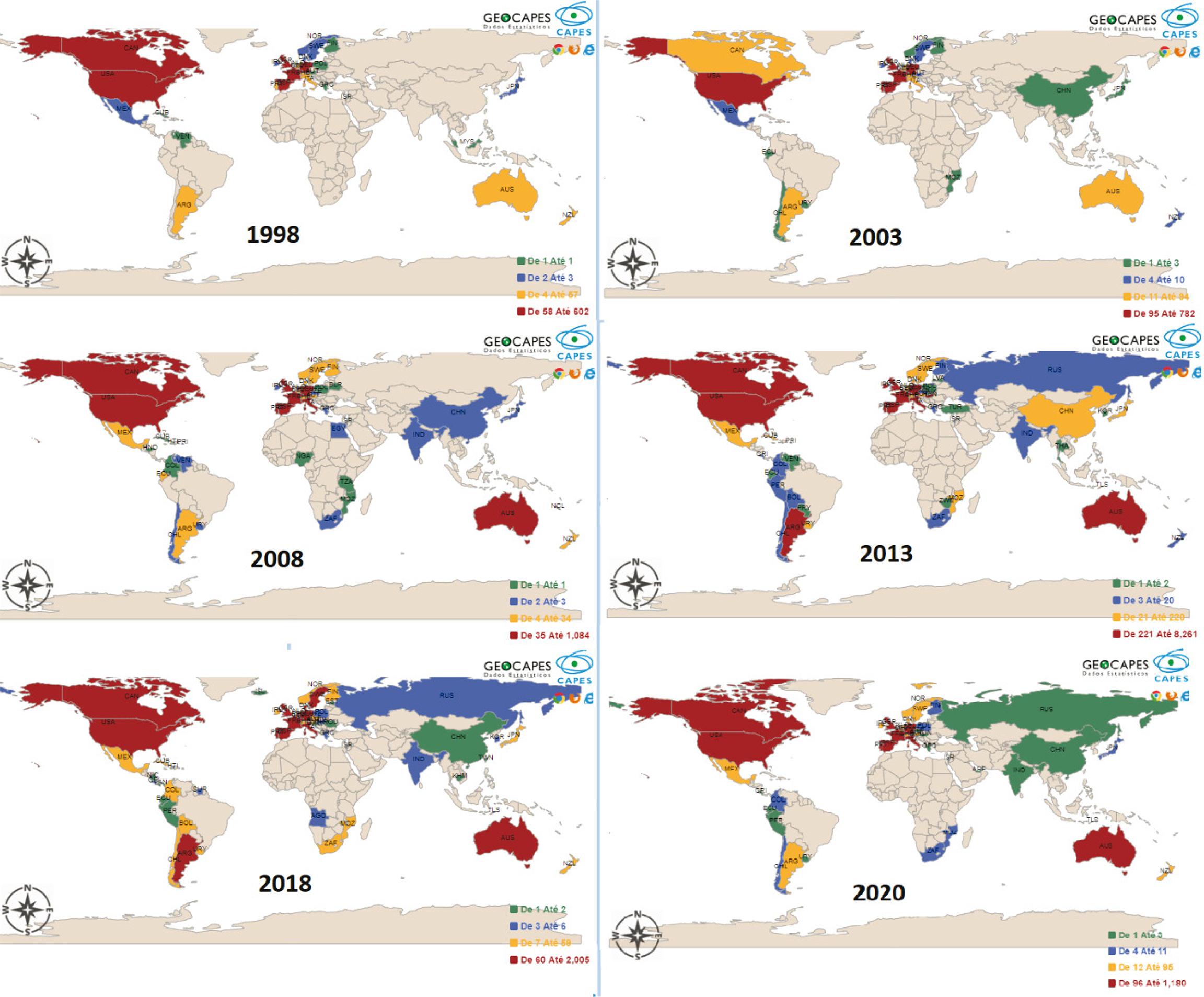

These data from the destination continents are in line with the following images, which have a compilation of 5 images extracted from Geocapes with the georeferencing of the countries where there were Capes scholarship holders from any area (not just Education, the focus of this article) in each one of the years 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, 2018 and 2020, following the methodology adopted by this research. The multiplicity of countries is clearly perceived when comparing the years 1998 to 2013.

Source: Image captures from

Figure 1 Compilation of 6 georeferencing images of the destination countries of Capes scholarship holders from all areas in the years 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013, 2018 and 2020.

When analyzing the languages in which the scholarship holders were immersed in the destination institutions, there is a wide use of English, French, Portuguese, and Spanish in the years 1998, 2003 and 2008, but it is interesting to notice that in 2013 the Italian language ranked second compared to the others ( Table 3 ).

Table 3 Languages which the scholars had contact with

| 1998 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | 2018 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German | 1 | 6 | 3 | 51 | 5 | 5 |

| Danish | 1 | |||||

| Spanish | 8 | 13 | 22 | 95 | 44 | 28 |

| French | 19 | 24 | 14 | 82 | 30 | 25 |

| Hungarian | 16 | |||||

| English | 14 | 23 | 18 | 406 | 54 | 30 |

| Italian | 2 | 1 | 5 | 117 | 8 | 5 |

| Japanese | 4 | 1 | ||||

| Mandarin | 6 | |||||

| Dutch | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Norwegian | 3 | 1 | ||||

| Polish | 1 | |||||

| Portuguese | 2 | 26 | 50 | 218 | 81 | 32 |

| Russian | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Swedish | 1 |

Source: Data from GeoCapes (BRASIL, 2022)

Regarding the analysis by blocks or economic forums, it is worth remembering what was explained in the methodology. Each country in the sample was included in only one block/forum that would bring more contributions to the interpretation of the results of Brazil’s relations with other blocks/forums. So, 4 (four) Apec countries were organized, in this study, in other groups: for Nafta, United States and Canada;for Brics, Russia and China. It is observed that the European Union together with Naftahave a strong and long history of receiving Capes scholarship holders in their institutions. Despite this, the other Apec countries, the Community of Portuguese Language Countries and Mercosur had a great rise in 2013, but that did not happen in 2018 ( Table 4 ).

Table 4 Trade blocs or Economic forums for scholars’ destination

| 1998 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | 2018 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alba | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Apec | 140 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Brics | 6 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Caricom | 2 | |||||

| Andean Community | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Community of Portuguese Language Countries | 78 | 10 | 3 | |||

| EFTA | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Mercosul | 1 | 1 | 22 | 5 | 4 | |

| Nafta | 12 | 18 | 11 | 314 | 48 | 25 |

| European Union | 33 | 74 | 97 | 535 | 149 | 95 |

Source: Data from GeoCapes (BRASIL, 2022)

Among the most frequent destinations for Capesscholarship holders, we find Portugal, the United States, France, Italy, Australia, and Spain, respectively.Australia, Canada and Mozambique played an important role in 2013 ( Table 5 ).

Table 5 Countries where the scholars went to

| 1998 | 2003 | 2008 | 2013 | 2018 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | 1 | 6 | 3 | 51 | 5 | 5 |

| Angola | 1 | |||||

| Argentina | 1 | 1 | 18 | 4 | 4 | |

| Australia | 134 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Belgium | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Canada | 4 | 5 | 5 | 65 | 16 | 7 |

| Chile | 2 | |||||

| China | 6 | |||||

| Colombia | 1 | 4 | ||||

| Cuba | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Denmark | 1 | |||||

| Spain | 7 | 12 | 19 | 62 | 31 | 20 |

| The USA | 8 | 13 | 6 | 242 | 29 | 16 |

| France | 15 | 20 | 12 | 74 | 20 | 22 |

| Hungary | 16 | |||||

| Ireland | 45 | |||||

| Italy | 2 | 1 | 5 | 117 | 8 | 5 |

| Japan | 4 | |||||

| Luxembourg | 1 | |||||

| Mexico | 7 | 3 | 3 | |||

| Mozambique | 65 | 8 | ||||

| Norway | 3 | 1 | ||||

| Netherlands | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Poland | 1 | |||||

| Portugal | 2 | 26 | 50 | 140 | 71 | 29 |

| The UK | 6 | 8 | 7 | 25 | 12 | 8 |

| Russia | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Switzerland | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Suriname | 2 | |||||

| East Timor | 13 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Uruguay | 4 | 1 | ||||

| Venezuela | 3 |

Source: Data from GeoCapes (BRASIL, 2022)

When we compare the lists of the top 20 institutions with the most scholarship holders from Capes considering total data with possible repetition over the years and data without repetition of scholarship holders in the modality (every 5 years), it can be seen that 15 institutions remain at the top of the two lists (highlighted in gray) of those that received the most scholarships from Brazil: 5 Portuguese universities, 4 Italian, 2 Spanish, 1 Mozambican, 1 Hungarian, 1 South African and 1 Timorese. Still considering these two lists, there are universities on all continents, with emphasis on the large number of institutions in Europe. From these lists, the languages of the most predominant educational institutions were, in sequence: Portuguese, Italian, Spanish, English, French and Hungarian.

4 Discussion

It is noticed that Latin America, Africa and Asia, as well as countries from economic blocs such as Mercosur and Bricsare less explored by candidates and with few public notices from Capes itself, for instance the Brazil South-South Cooperation Program (Coopbrass), the Teacher Qualification and Portuguese Language Teaching Program in East-Timor with one of the members of the CPLP, and, more recently, the Institutional Internationalization Program (Capes/Print, enhancing a little more academic autonomy).

Therefore, it is questionable whether the current role of Brazil is to seek to join large research networks in Education and Science, or to seek to be a protagonist (player) in the development of highly qualified human resources training and research. We need to emphasize that one role does not exclude the other, but that, in the Brazilian case, it seems to us, it is too much the first one.

Wit e Altbach (2021) draws attention to the fact that the context of internationalization of Latin American countries is very much focused on the Global North and not very regional, which increases the dependency of these nations in various economic and academic aspects. Both data and Wit’s vision reinforce the idea that developing nations, even after their administrative independence, are still dependent on their settlers in the economic and political fields ( CHANG, 2003 ), and from what we have been noticing, perhaps in the academic one as well. An example of the regionalism of internationalization is the Erasmus Program, which provides interaction among academics from the European Union, and which was, in large part, promoted after the Bologna Process, an act that documented the minimum common bases of Higher Education for most courses within the scope of the European Union.

Both for joining these training and research networks and for protagonism, the actions of internationalization of Higher Education in Brazil face many limitations of a technical, linguistic, and international relations/collaboration nature (FINARDI; GUIMARÃES, 2020; MIRANDA; STALLIVIERI, 2017 ).

It is observed that even though Brazil participates in different spaces with specific interests and geopolitical strategies, they converge to precepts of participation in the modern global market, mainly since the 1990s, with the Normal State paradigm. There has been a greater search for protagonism with the Logistic State paradigm since 2002 ( CERVO, 2003 ). With the Governments from 2003 to 2010 and from 2011 to 2016, many actions were developed in the foreign policy of Higher Education, with emphasis on Science Without Borders, with a view of strengthening national science with the exchange of students and researchers. However, in the Government from 2016 to 2018, there was a setback in language policy: in 2017 it was restricted granting cholarships to Portuguese-speaking countries only to candidates who took proficiency exams in the English language.

The Government’s lack of investment and enhancement policy and scientific development from 2019 to 2022 was once again clear when still in 2022, Capes did not have a National Graduate Degrees Policy after the end of the 2011-2020 decade, as well as when the MEC presented Future-seas a trend for Brazilian Higher Education,This is a program of voluntary adherence by Federal Institutes and Universities to establish private fundraising for public institutions with an emphasis on entrepreneurship and innovation, according to its proposal. This program faced a lot of criticism about this public-private relationship potentially both weakening Brazilian public Higher Educationand reducing federal funding responsibility on these institutions (PAULA; COSTA; LIMA, 2020).

Analyzing data on scholarships granted by Capes as a whole (not just for the Education area, as in this article) and Government policies since the 1950s, Cruz and Eichler (2021) confirm that theoretical elements and data show that Lula and Dilma governments were the ones that showed the most international articulation.Since the Temer Government, Brazil has been going through a periodcalled by the authors “Anchoring”, given the limited internationalization actions. The article by Cruz and Eichler (2021) also shows that the Student Mobility Index (IME) of the Dilma Government was the highest in history, with 0.118.

It is a challenge for the 12th economy in the world to grow from the 13th position in articles production in the world ( GUIMARÃES, 2018 ) and from the low rate of citations per article in several areas, mainly in Human Sciences. It is important to pay attention to goals 13 and 14 of the National Education Plan ( BRASIL, 2014 ) for increasing the number of masters and doctors in the country. Sending these students and professors to developed countries, as a custom of countries that were already developing, provided many experiences in loco and these students and professors returned to their countries of origin to be multipliers, as explained in the Incheon Declaration.

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, other possibilities of interaction mediated by computer and virtual exchange (Virtual Exchange) have been observed with actions of Brazilian students and professors in simultaneous academic interaction with foreign students and professors and in different contexts, such as courses, disciplines, meetings of research groups, boards, and events. Evidently, the virtual exchange does not replace the cultural experience of immersion, the acquisition of practical skills, access to materials or even the strengthening of bonds that everyday life enhances. However, given the financial factor of mobility and academic exchange, these possibilities can provide important alternatives for the internationalization of Higher Education (FINARDI; GUIMARÃES, 2020).

One of the great challenges of the internationalization policies of countries in the Global South is related to the financing of actions, mainly those related to mobility. Therefore, in this study, many of the programs linked to the Capes were or are in partnership with the Global North, such as the Fulbright Program, German Academic Exchange Service –Daad, International Degrees (PLI), Science without Bordersand Sandwich Doctorate Program Abroad ( Programa de Doutorado Sanduíche no Exterior - PDSE). Coincidence or not, it meets what is set out in one of the goals of the Incheon Declaration.

The financial aspect has been debated as one of the obstacles to the Internationalization of Higher Education. Popularly, it is common to hear “without resources there is no internationalization”, a thought that strongly links the internationalization policy to financial investment in the mobility of professors and students and texts translation. In part, this is well-founded and a constant political struggle for promotion is necessary, but there are other possibilities which have not been explored yet, especially in these times of pandemic, which have boosted virtual exchange.

Not being limited to mobility as a possibility of internationalization ( KNIGHT, 2011 ; KNIGHT; WIT, 2018 ), we can relate Domestic Internationalization to some local possibilities such as disciplines offered in languages other than Portuguese and partnerships with foreign researchers and research groups, taking advantage of all the possibilities of these partnerships.

It is observed that some international Educationorganizations and the use of ranking in Basic Education and Higher Education have been instruments of international policy through a movement of external legitimation to insert themselves in countries, many of them in development. In addition, Vasquez, García and Canan (2022) indicate that the United States and Europe are ahead in the rankings of the best Higher Education Institutions due to using criteria which highlight their economic and social characteristics, and thus further enhance academic mobility for their institutions. It would be frivolous to say that it is a matter of apathy or collusion on the part of the governments, since they are aware of the “game” they are involved. It is more likely that the possible movements of protagonists are limited and that many of them are coerced to participate in these actions. Perhaps here we have one more example of a softlow in action.

Another important aspect which has been discussed is the privatization and standardization of Education at a global level, both in Basic Education and in Higher Education. This privatization would take place through mechanisms of the global industrial vision of Education (Global Education Industry, GEI) and a societyrefeudalization ( AMARAL; THOMPSON, 2019 ) also through Education, whether via chains of private schools, or even, in our case, from a Eurocentric perspective of university and internationalization. It is interesting to remember the role of university managers in internationalization strategies and their relevance in the academic context, as presented in the study by Costa and Canen (2022) .

The needs and proposals for internationalization models are not denied here, but a more consistent reflection on the role of regional economic blocks and the geopolitical perspectives of knowledge is fundamental, both in Basic and Higher Education.

5 Final considerations

The study showed the growth in the number of institutions and Capes scholarship holders abroad in Education over the years 1998 to 2020, with an important turning point from 2011 to 2012. Portugal, the United States, France, Italy, Australia and Spain, respectively, are among the most frequent destination of Capes scholars. Among the 20 institutions which hosted the most Capes scholarship holders, 17 were from universities in Latin languages speaking countries (Argentina, Spain, France, Italy, Mozambique, Portugal, and East Timor). Also, there is a strong insertion of scholarships in countries of the global north and few actions at the regional level, and related to Brazil’s protagonism in the Latin American and African context.

It is important to understand internationalization as an instrument for the development of institutions and social impact in the region in which it operates, besides reinforcing that Brazilian foreign policy regarding the training of human resources can adhere to large research networks in Education and Science, but also have a higher position with the countries of Latin America and Africa.

The historical-critical interlocution of Education in Brazil with Latin America, Ibero-America and Africa presents several mutual advantages due to the cultural proximity and common challenges, and with that they develop into an open regionalism with potential for global insertion of relevance. Such advantages provide an extent of global academic discussions for local solutions and articulation for the scientific and economic development of the region.

It is worth calling attention to the large number of reports of experience and evaluation of the internationalization of Higher Educationinstitutions, although they were not included in this research. It remains as a study proposal to map this type of action by Brazilian institutions.

Table 6 Comparison of the first 20 institutions with more scholarship holders considering total data (with possible repetition – first column) and five-year data (without repetition in the modality – second column)

| Top 20 | N | Language | Country | Continent | Top 20 | Top 20 | N | Language | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Lisbon | 393 | Portuguese | Portugal | Europe | University of Lisbon | 76 | Portuguese | Portugal | Europe |

| University of Minho | 319 | Portuguese | Portugal | Europe | Pedagogical University | 72 | Portuguese | Mozambique | Africa |

| Pedagogical University | 251 | Portuguese | Mozambique | Africa | University of Minho | 68 | Portuguese | Portugal | Europe |

| University of Porto | 211 | Portuguese | Portugal | Europe | Universityof Coimbra | 50 | Portuguese | Portugal | Europe |

| University of Coimbra | 184 | Portuguese | Portugal | Europe | University of Porto | 49 | Portuguese | Portugal | Europe |

| University of Barcelona | 153 | Spanish | Spain | Europe | University of Barcelona | 34 | Spanish | Spain | Europe |

| University of Pisa | 87 | Italian | Italy | Europe | University of Pisa | 32 | Italian | Italy | Europe |

| National University of East Timor | 81 | Portuguese | East Timor | Asia | University of Padua | 24 | Italian | Italy | Europe |

| University of Aveiro | 66 | Portuguese | Portugal | Europe | University of Aveiro | 20 | Portuguese | Portugal | Europe |

| Eötvös Loránd University | 64 | Hungarian | Hungary | Europe | Flinders University | 18 | English | South Africa | Africa |

| University of Padua | 56 | Italian | Italy | Europe | National University of East Timor | 17 | Portuguese | East Timor | Asia |

| Complutense University of Madrid | 52 | Spanish | Spain | Europe | MacQuarie University, Sidney | 17 | English | Australia | Oceania |

| University of Montréal | 52 | French | Canada | North America | University of Rome “Tor Vergata” | 16 | Italian | Italy | Europe |

| Open University | 50 | Portuguese | Portugal | Europe | University of Bologna | 16 | Italian | Italy | Europe |

| School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences | 50 | French | France | Europe | James Cook University | 15 | English | Australia | Oceania |

| Universityof Buenos Aires | 41 | Spanish | Argentina | South America | University of Wollongong | 15 | English | Australia | Oceania |

| University of Rome “Tor Vergata” | 39 | Italian | Italy | Europe | Eötvös Loránd University | 14 | Hungarian | Hungary | Europe |

| University of Bologna | 39 | Italian | Italy | Europe | University of Alberta | 13 | English | Canada | North America |

| University Pierre and Marie Curie – Paris VI | 38 | French | France | Europe | York University | 13 | English | Canada | North America |

| Flinders University | 37 | English | South Africa | Africa | Complutense University of Madrid | 13 | Spanish | Spain | Europe |

Source: Data from GeoCapes (BRASIL, 2022)