Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educar em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0104-4060versão On-line ISSN 1984-0411

Educ. Rev. vol.37 Curitiba 2021 Epub 08-Abr-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.75519

DOSSIER - The biographical dimension as formation process, self comprehension and world understanding

The ambition of being another’s desire: mixed-race people’s writings from a family from the suburban of Rio de Janeiro1

* Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. E-mail: andreiaacastro@yahoo.com.br. E-mail: lualpires@gmail.com

This article seeks to challenge the narratives of the mestizo experience not only as a production of whitening but also as the staging of a stereotype. Both embodied in the experience of our family, reflecting tensions, modes, and projects of national identity. The romanticization of miscegenation, a place of production, foundation, and dissemination of the ever-dissatisfied desire to be another, marks the game of projections, simulations, and concealments of the narrative of our ancestry. As researchers, we seek to unravel some mysteries, fill in gaps, analyze the tensions of these stories that did not always tell the facts for what was said, but for the interdict, not said, ill-said. Knowing the process of formation and conformation of families, many times does not lead to knowing the process of formation and conformation of society, the country, and the world.

Keywords: Narrative; Biography; Representation; Genre; Race

O presente artigo procura interpelar as narrativas da experiência mestiça não só como produção de branqueamento, mas também como encenação de um estereótipo. Ambos encarnados na vivência da nossa família, refletindo tensões, modos e projetos de identidade nacional. A romantização da mestiçagem, lugar de produção, de fundação e de disseminação do desejo sempre insatisfeito de ser outro, marca o jogo de projeções, simulações e dissimulações da narrativa de nossa ascendência. Enquanto pesquisadoras, buscamos desvendar alguns mistérios, preencher lacunas, analisar as tensões dessas histórias que nem sempre contavam os fatos pelo que era falado, mas pelo interdito, não dito, mal dito. Conhecer o processo de formação e de conformação das famílias, muitas das vezes, no leva a conhecer o processo de formação e de conformação da sociedade, do país e do mundo.

Palavras-chave: Narrativa; Biografia; Representação; Gênero; Raça

Representation and identity

According to Chartier (1990), the concept of representation is based on two distinct realities, but which intertwine. One concerns collective identities, rites, the ways that underlie social institutions. The other refers to the person's identity, the types of individual display, and the assessment of that individual by the group. Through representation, standards, beliefs, and values are found, many of them marked by transience, instability, fluidity, but all related to aesthetic, moral, religious, philosophical, political, and economic issues, supporting relations of power, domination, and resistance. Literature, newspapers, official documents, life stories, and popular cults are instruments of construction, interpretation, dissemination, and questioning of the dominant representations, but it also projects, maintains, and subverts individual and collective identities. If representation means to give visibility to others, historically, it also means to silence another. Dominant individuals or groups, legitimized by social instances, such as class, race, and gender, disqualify, disallow or prevent the discourse of marginalized minorities, especially the dissonant ones. Considering the postulates developed by Kimbérlé Crenshaw (2012) on the concept of intersectionality, the greater the confluence between these connections of subordination, the stronger the forces of silencing and oppression will be.

This article seeks to describe the scene of the mixed-race people’s experiences. We seek to inscribe our life stories, not only in the narrative of the production of the feeling of nationality but also in the denial of this notion of belonging. A confrontation marked in the bowels or viscera of our society. The dispute that Munanga (2019) calls “national identity versus black identity”. The romanticization of miscegenation would take the place of the production of an ethnocide, of the founder and disseminator of a desire always dissatisfied with being somebody else, marking the otherness as a constant game of projections, simulations and concealments. Our double ancestry is regarded by the attempt to adjust to the identity models provided by colonial and national discourses: Maria, a black woman, who sought to find redemption in her marriage to an older, widowed European with three children. Ermelinda, a white woman who disposed of herself and her offspring to the appetites of capital, in an alterity process called by Kiening (2014) as artificial savages.

Body, desire, and consumption

At the end of the nineteenth century, to encourage consumption, advertising connected the female image with all sorts of products. In many of these advertisements, it is possible to perceive the intention of arousing the reader's attention and desire through the sensual representation of the woman's body, making everything that offered was with her equally desirable. The success of this sales strategy, as is known, was huge, and female bodies, even today, continue to be standardized, displayed, and offered, symbolically or in fact, even after so many feminist struggles.

In the private sphere, the female body was also used as symbolic capital in the acquisition in the maintenance of social status, in the case of honorable and descended mothers, wives, and daughters; likewise, for the affirmation of male virility, of those who had lovers or other types of relationships with prostitutes. In this equation, the beauty of the female body has always had weight, as well. The husband or lover, who had an admired and, above all, desired wife, enjoyed greater social prestige.

In Brazil, the long colonial slave system seems to have retaken and particularized these issues. Under intense male domination, women's bodies, especially those with darker skin, were subjected to the interests and desires of dominant men. The body of the Indians and Black women were understood as an inexhaustible and unstoppable source of pleasure, work, and exploration.

Details of Pero Vaz de Caminha's letter to King Dom Manuel, one of the first official records in Brazil, reveal that the European's view of the natives' nudity. According to the writer, the natives' naturalness and lack of shame when showing their naked bodies caused the lack of modesty of those who admired them:

There were three or four girls among those men, very young and very kind, with black hair, long by the shoulders, and their shame so high, so close and so clean from their hair that, if we looked very well, we were not ashamed ( ...) and certain it was so well made, and so round, and her shame (which she did not have) so graceful, that many women in our land, seeing such features, were ashamed, for not having their own as those did (CAMINHA, 2020, p. 5).

Among the foreigners who arrived here in the following centuries, a consensus, that was not exactly deliberate, but that exceeded the limits of nationality and doctrine, was created: it seemed that the tropics set moral and religious duties in total suspension. If the natives were not ashamed or guilty when showing their bodies, Europeans were not ashamed or guilty when admiring and desiring them. Nudity as a reflection of extreme sexuality was also affirmed as an element that brought the indigenous people closer to the animals, justifying a dehumanization that only favored the exploitation of the colonizer, which the reports of the chronicler and historian Pêro de Magalhães de Gândavo strongly exemplify:

they live like brute animals without order or fixing by men, are very dishonest and given to sensuality and indulge in vices as if there was no reason for them to be human, although, nevertheless, they always keep the males and females together, show some shame in this (GANDÂVO, 2008, p. 68).

As with the witch-hunting movements in Europe, in the New World, older women, due to their latent leadership position, continued to be demonized and feared.

Everyone follows the advice of the old women a lot, everything they tell them they do and understood it as right: here many residents do not buy any because they do not make their slaves run away (GANDÂVO, 2008, p. 69).

The small distance from the medieval imaginary also took place concerning younger indigenous women. In the speech and images produced by the travelers, the natives were portrayed as erotically treacherous creatures, capable of using the beauty of their bodies to seduce Europeans to attack them and even devour the most unsuspecting.

Due to the massive replacement of enslaved indigenous labor by African labor, consolidated at the turning of the 17th century, the same figuration of an erotically available and highly astute woman was easily linked to black women and widespread both in the colonies and in the Portuguese metropolis. African women and their Brazilian descendants, reified and exploited, immediately received the image of “the hottest lovers”, of women always willing to fulfill any and every male desire. The representation of these ardent "brunettes", "browns" or "mulattos", bringing to light all the significant burden underlying these terms, contributed to the consolidation and diffusion of this vision, the basis for stigmatization, subordination, and social marginalization. Whether they were the color of Jambo (a type of Brazilian tropical fruit), cinnamon, or ripe wheat, the mention of the different skin tones resulting from miscegenation was often coupled with the stereotyped description of the body of Brazilian women in general: stiff breasts, thin waist, wide hips, large buttocks, and shapely legs. This whole set of attributes would usually determine peculiarities movements, presented as attractive and lustful gestures and movements when they sing and dance to popular rhythms.

However, sight, hearing, and touch were not separated from taste and smell concerning the perception of the female body. According to Alain Corbin (1987), the olfactory subtleties allowed new management of desire for the bourgeois. Mothers, sisters, wives, and daughters should exhale the delicate scent of flowers, consistent with modesty and discretion. Gardens are now separated from home gardens and more handcrafted perfumes are surpassed by fragrances prepared by perfumers. Musky scents or those that aroused appetites, such as fruit, herbs, and spices, could be interpreted as erotic olfactory messages, is intended for those who wanted to awaken their libido and were willing to “sensual enjoyments” (CORBIN, 1987, p. 239).

This prescription regarding aromas and flavors, for Affonso Romano de Sant’Anna (2011), would be realized in the distinction between the “woman-flower” and the “woman-fruit”, a division created and exercised by and for male control. In the space division of the wealthy Brazilian homes of the nineteenth century, the place of the white woman would be the entrance to the house, decorating, like a flower, the garden, the façade, and the halls; the mulatto, as a fruit, would be in the back, the kitchen, the vegetable garden, the orchard, spaces linked to gastronomic and erotic food. And it is “between the garden and the kitchen, that the ghosts of the lover poet wander, who in his words dramatize the conflicts of the average man of his time” (SANT’ANNA, 2011, p.16).

SOURCE: “O Mequetrefe” (The Good-for-nothing).

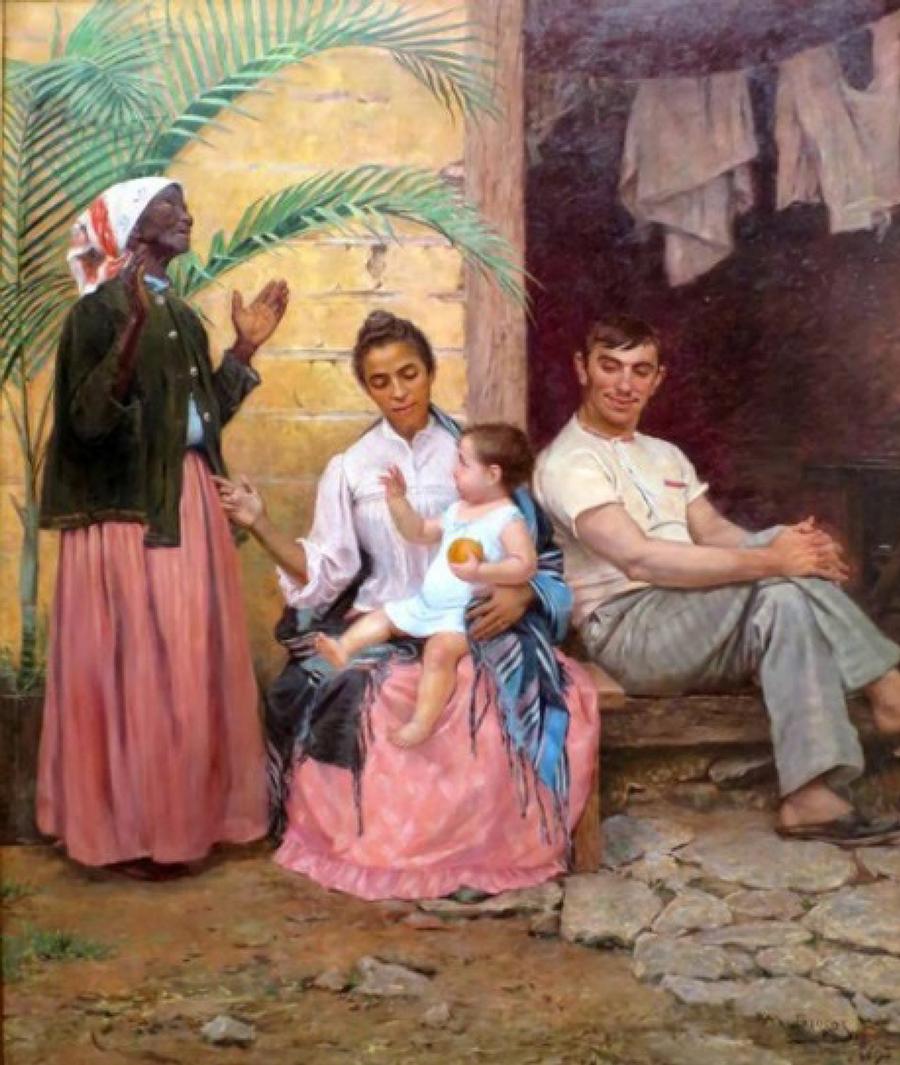

PICTURE 1 ILLUSTRATION OF THE NEWSPAPER “O MEQUETREFE” (THE GOOD-FOR-NOTHING)

The mulatto woman is said to be unbeatable in the kitchen and bed. Cooking, loving, two complementary activities, become synonymous and are explored in all their complexity and ambiguity, as we see in the image of “O Mequetrefe” (The Good-for-nothing). The meal brought by the mulatto at the same time indicates her social situation, a woman belonging to the working classes prepares her food, and the cannibalistic erotic look cast by the wealthy white man, whose possessions are represented by the enormous wallet. Passages from the famous and controversial book by Gilberto Freyre, “Casa Grande and Senzala”2 (1933), reveal how the sexual reification of Brazilian women obeyed, from the social imaginary, a chromatic spectrum: “[...] the brunette woman has been the Portuguese favorite for love, at least for physical love. [...]. Regarding Brazil, the saying goes: “White to marry, mulatto to f ..., black to work” (FREYRE, 2005, p. 71-72).

The mulatto woman was “the desired one”, but to enjoy the pleasure of feeling in a prominent position, it was necessary to weaken her. The “mixture”, encouraged, legitimized, trivialized, in the intimate sphere, was the realization of a false promise of redemption. In the project of the nation, miscegenation aimed at the whitening process of the Brazilian people and the destruction of plural ways of making oneself under multiple signs of identities.

Full of ideas, desire, and advertisement of the policy whitening explicit put on stage, on the canvas of The Redemption of Cam, by the Spanish painter Modesto Brocos. The painting was successful in Europe, accompanied by the caption: “the black becomes white, in the third generation, due to the crossing of races The poet Olavo Bilac, under the pseudonym of Fantasio, in the Gazeta de Notícias, also made his contribution by saluting Brocos' work in the Gazeta de Notícias with the following words: - dawn daughter of the diluculum, granddaughter of the night ... Cham is redeemed!.. (FANTASIO, 1895, p. 1).

Like so many Brazilian families, we are going through this process that we call for the ambition of being “what somebody else wants”. This worked as a motivation for the links and the familiar plots. The examination of private memories places autobiographical writing as a rich source of analysis and studies of Brazilian society as an “imagined community” (ANDERSON, 2008, p. 30). Because we believe that the individual plots offer threads that are relevant to collective understanding, we decided to open our alphabets to describe the paths of our ancestry and ancestry.

Ancestry and redemption

The first path to be taken is great-grandmother’s on the mother’s side: Maria Ramos Gouvea, a black woman, born in 1910, in Serra da Canoa, traveled the paths from Sabinas do Quilombo São José da Serra to Paracambi. We do not have, in memory, reports of our great grandmother as a quilombola4 person. We became aware of this fact through Brother Benedito's death certificate buried in a quilombo cemetery. The same silence is felt regarding the quilombola’s person presence in the official history of the county of Paracambi. Despite having a neighborhood called Quilombo, Paracambi is presented in historiography only by the Jesuit occupation, responsible for the fervent local faith; colonial rule, through the Santa Cruz farm; hydrographic wealth, represented by the Rio dos Macacos (Monkeys River); and the Estrada de Ferro Dom Pedro II (Dom Pedro II’s Railway), which in the republican period became part of the Federal Railway Network (RFFSA).

Paracambi got modernized when it received the Companhia Têxtil Brasil Industrial (Brazilian Textile Industry Company), which was installed there aiming at the exploitation of the richness of the waters of its rivers, of the woods of the forests and the workforce of the quilombola population who remained in the place. The only single part of the black population that did not migrate. The remaining workers, in possession of their newly guaranteed freedom, migrated to other locations. This population movement even marked a change in the region's economic activities. As Gênesis Torres (2008) states in an official publication of INEPAC:

By looking for some other theoretical references, we were able to establish a relationship between the black quilombola presence in Paracambi and the understanding of the flourishing and the prevalence of African sacred in our family. Through Mattos (2006), we became aware of the reports of Toninho Canecão, Quilombo's political leader, who narrates the arrival and departure of the black groups of workers in the region. Toninho traces routes very similar to our family's: leaving the coffee farms, passing through Valença, until reaching the favelas (slums), the poor neighborhoods, and the Baixada Fluminense.

Our family arrives in Paracambi coming from Minas Gerais. Maria Sabina Ramos was born in 1878, the daughter of the enslaved black woman, Sabina das Dores, and her white master, António Inácio Seixas. She comes into the world after the Free Womb Law, being welcomed by the popular knowledge and memories of the captivity. Her mother was a midwife, healer, and knowledgeable about activities that served early childhood. According to official documents, she lived in Serra da Canoa, in Valença, a region belonging to the important Quilombo São José da Serra. Maria Sabina gets married, raises her children: Sebastiana, Paulino, Francisco, Benedito, João, and Maria. The woman prematurely loses some and brings so many other children into the world. Our great-grandmother Maria, a remnant quilombola, had access to the alphabet in precarious ways with public instruction in the province of Rio de Janeiro. The region had a few farm schools. Maria defined herself as someone who could only read, never write. Still very young, she worked at the fabric factory until she married António. After the marriage, she moved to São João de Meriti. In addition to welcoming, caring for and raising her three children from her husband's previous marriage, Maria had ten other children. Among these, only six met adulthood: Niuza (our grandmother), Neuza, Ari, Aroldo, Amauri, and Nilda. The other four did not survive, angels died, a condition very common at the time.

The fruits Mary had were not only sons, daughters, grandchildren, granddaughters, great-grandchildren, and great-granddaughters. She brought the seeds of the culture and a sacred quilombola. Her family's Umbanda5 temple made the Quilombo reappear in the waves of the generations, being the root of cultural resistance against the onslaught of a national identity forged from the logic of the process of whitening the population and the cultural erasure. The black geopolitical space was kept alive in the performances of spirituality. The space for the Umbanda temple is very similar to the Quilombo space. The temple reopened the Quilombo by resisting the identity erasure, which Munanga (2019) called ethnocide, the cultural route of genocide.

SOURCE: authors’ private collection

PICTURE 5 CELEBRATION FOR IEMANJÁ AT CABOCLO PENA VERDE’S TEMPLE

In image five, we can see Sandra Maria (our mother), Maria Ramos' granddaughter, in our family's temple, located in the suburb of Rio de Janeiro. Our temple, directed by Mother Neusa, was commanded in the ancestral condition by Maria Sabina. Vovó Sabina became popular as a well-known entity in several Umbanda temples in Rio de Janeiro. Despite all the stereotypes fixed in the black father and mother figures, we see that the popular imagination creates its icons of authority in the symbolic space, claiming for itself a place of representation, memory, and devotion. Old black men, in their ancestral condition, gain image and cult value. Its presence in the sphere of the sacred reveals the ineffectiveness of a colonial order that aimed to inscribe the other in the fixed order of denial, as stated by Bhabha:

Once again, it is the space of intervention that emerges in the cultural interstices that introduces creative invention into existence. And, one last time, there is a return to the staging of identity as an iteration, the re-creation of the self in the world of travel, the re-establishment of the border migration community (BHABHA, 2001, p. 29).

Life as it is in the newspapers: fictions and family memories

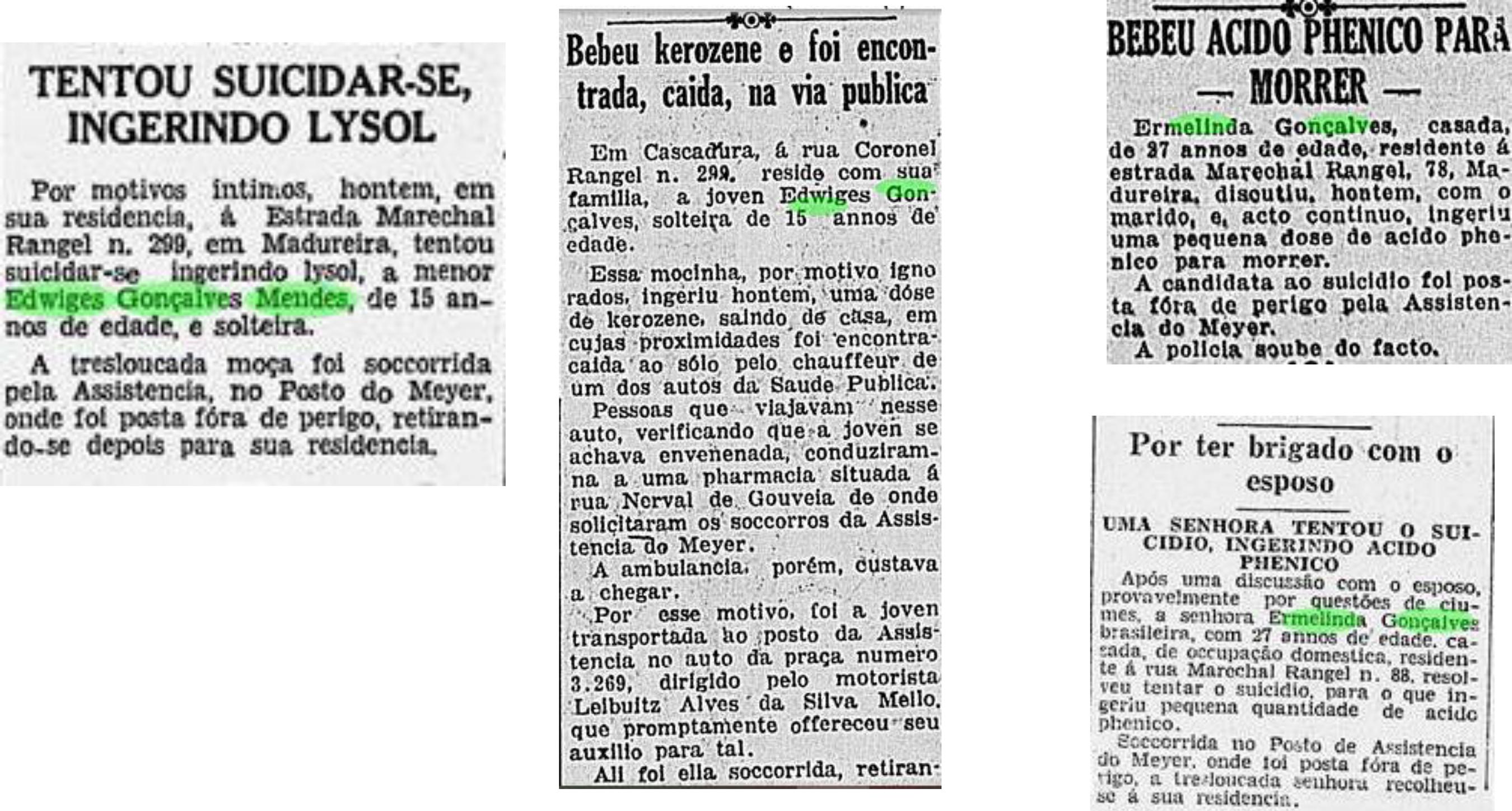

The second route belongs to Ermelinda and her daughter Edwiges, our great-grandmother and great-aunt on the father’s side. The two starred in scandals that filled with meat and blood and the newspapers from that time. Until the death of José Gonçalves Mendes, a military man, husband, and father, both mother and daughter fairly occupied the social places for white women in Rio de Janeiro's in the early 20th-century society. However, this conformity originated in a defloration process. The marriage between José and Ermelinda repaired the “bad step” taken by the young couple, but the record of the criminal prosecution was never extinguished, being possible to consult it, until today, in the Information System of the National Archives (SIAN):

Formally married, birth certificate of the first and only daughter, a house in the military village of Marechal Hermes. An important and happy family, the boy's great-uncle, Francisco José Gonçalves Vieira, enjoyed position and prestige, a lot of businesses in Brazil, many properties in Portugal. Her aunt, Laura Vieira Alves, widow and heir to a wealthy fabric and port wine merchant. The helpful cousin, António Inácio Alves Júnior, a capitalist whose money made the economy wheel spin in both countries. But death came early for him. A failed home made up of a beautiful young mother and a beautiful young daughter, now without support, without provision, without protection. António Ignácio seemed to be the solution. Fraternal arms, ingenuity to manage the business and the household. Ermelinda accepts the court of the rich protector, thinking that that affection would quickly make heritage and marriage walk alongside.

One more pregnancy out of wedlock, one more settling of accounts. However, maintaining consensual carnal conjunction with an older widow was not a crime. Glória Emília, “an interesting little girl”, would remain the illegitimate fruit of this connection. Nothing illegal, but very immoral for that society. The story told by the mother was the charitable profile of a foundling. Another helpless one for António Ignácio to protect. Status quo almost obeyed.

However, Ermelinda's eldest daughter did not want to keep portraying here as dumb in that affair. At fourteen, following her mother's footsteps, she runs off with a military boyfriend. Things do not go as expected. In their love nest, the girl finds more than one companion. Screams, cries, violence, and rape. The protector discovers the aviator's whereabouts in the Military Organization and arrives with the police to rescue Edwiges.

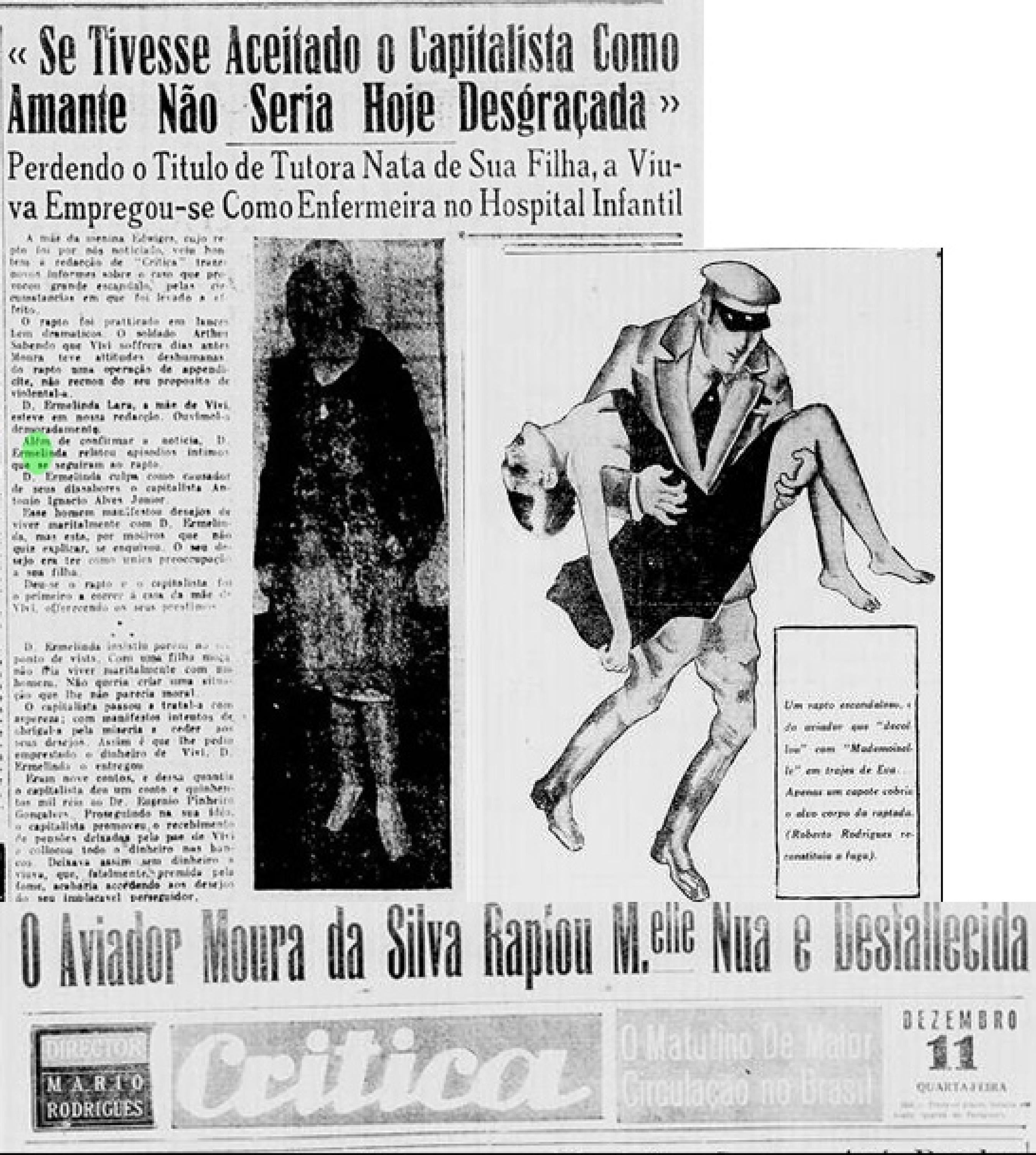

Ermelinda, seeming to ignore the difference between seduction and collective rape, thinks about accepting the reparation provided in the Penal Code. Marrying the victim and the aggressor seemed to be viable for that lady. Not for António Inácio, though. He does everything he can to keep his mother away from his daughters. Edwige is enrolled in a girls' boarding school. Glória Emília is going to live at her grandparents' house. Ermelinda does not accept the situation and seeks to give the greatest punishment she could to those who lived on the given word backed by the name. She tells her version of the story to the journalists in the family of the writer Nelson Rodrigues who, on purpose, ignored the facts that occurred to tell not how life was but how it could be.

Text and illustration told the story of those characters. The narrative was constructed through two overlapping basic elements: the history of the legal action and the life of those who were involved. The texts produced in a simple and hyperbolic language were published with great illustrations, allowing a quick apprehension of the subject addressed. The seductive aviator. The fellow who awaits. The escape with the fainting and naked girl in her arms. The police investigation. Compulsory hospitalizations. Two daughters without a mother. A savior turned into a "hawk" hunting two pigeons. A man who took advantage of his mother to be with the daughter.

However, the dealer had to choose between the custody of his little daughter, Glória Emília, and his most precious asset: honor. The blackmail was not well succeeded. For him, the ink-stained name of the newspaper meant a broken business. For Ermelinda and Edwiges, who were no longer part of the beautiful, demure, and homegroup, that was a guarantee of instant fame. Meanwhile, António Inácio tried to get up. The two, addicted to attention, continued to populate the pages of the newspaper of the time, helping them to sell to readers an escape, even if fleeting, from the monotony of the daily basis, a truce in worries, a relaxation in tensions and oppressions from the day-to-day, a result of the sensations forbidden to the “good citizen”:

SOURCE: A Batalha, 1930. Correio da Manhã, 1929. Diário Carioca, 1930.

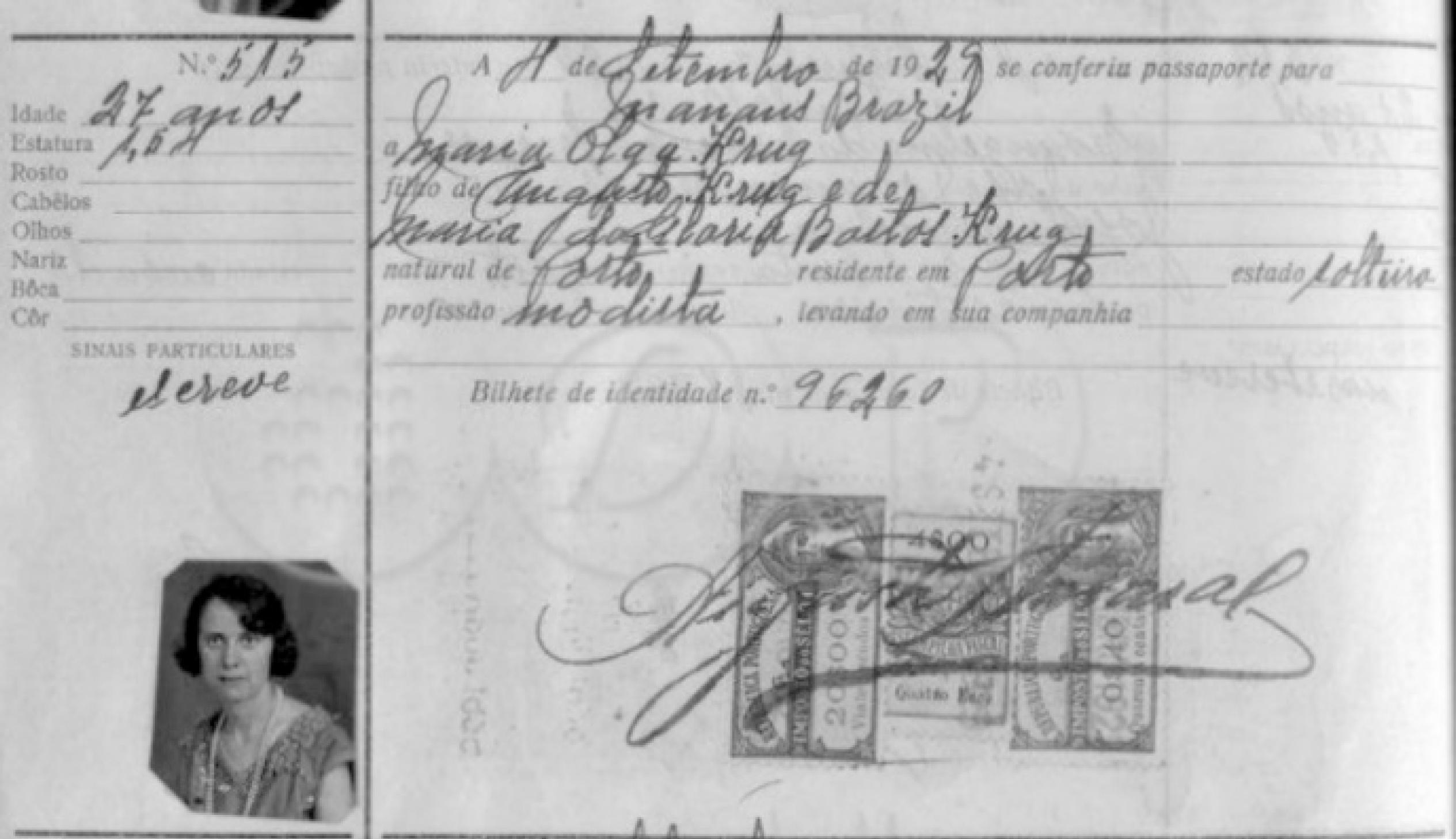

PICTURE 8 SOME NEWSPAPER CLIPPINGS WITH NEWS ABOUT ERMELINDA AND [EDUCAR1]

After the demoralization caused by the successive reports and interviews published by Crítica (Critics), António Ignácio would never be who he used to be in the past. Small businesses in the suburb of Rio. Real estate rentals, money tied up in warehouses and bakeries. The dream of setting up the capital's first ready-made garment production in Parisian molds went down the drain. The only legacy of this visionary and aborted venture was to meet his life partner. Marie Olga Krug, a Franco-Lusitanian dressmaker, hired to work in the confectionery, also foreign, alone and with a small son in her arms. The four got together and created another family. New dreams, new annoyances, but these are already other stories.

The newspaper's newsroom also paid its share of that debt of misfortune and disgrace. According to professor and historian Magali Gouveia Engel (2005), Mário Rodrigues' journal was, at the same time, a politically influential page and “a follicle of scandals”. But from revealing so many secrets and outraging the life of the “common man”, the Rodrigues family would also taste its bitter poison. On December 26th, 1929, a day of little news, after the celebration of Christmas, “Crítica” (Critics) came out with the following headline: "A rumorous case of disquiet comes into court in this capital today". What followed the eye was pure sensation.

The newspaper accused Sílvia Tibau, a beautiful 27-year-old journalist and literary, of having betrayed her husband, doctor João Tibau Junior. The article, written with erotic and sensationalist nature, exuding false moralism top-bottom, revealed scathing details, not all true, as was his way. According to the writer, “the Aesculapius” Manuel de Abreu, in addition to seducing “madame Tibau”, in his own office, would have caused serious damage to the “marble and sensual” skin of the lover when trying to remove from her legs, using X-rays, pronouncedly thick hair expressions”. We grasp that honor would be washed with blood, on the same day that the report came out, Sílvia Tibau went, very well dressed, to the newsroom in the center of Rio de Janeiro. The woman would have asked to speak to Mário Rodrigues. He was not in, so she demanded a private conversation with Roberto, illustrator, and son of the writer. The girl pulled a gun out of her bag and shot him point-blank. Deeply confused, Mário would die about two months after the event, as a result of cerebral thrombosis. Nelson, who at the time was seventeen and focused on the newspaper, would have said that he owed many of his stories and style to Crítica (Critics).

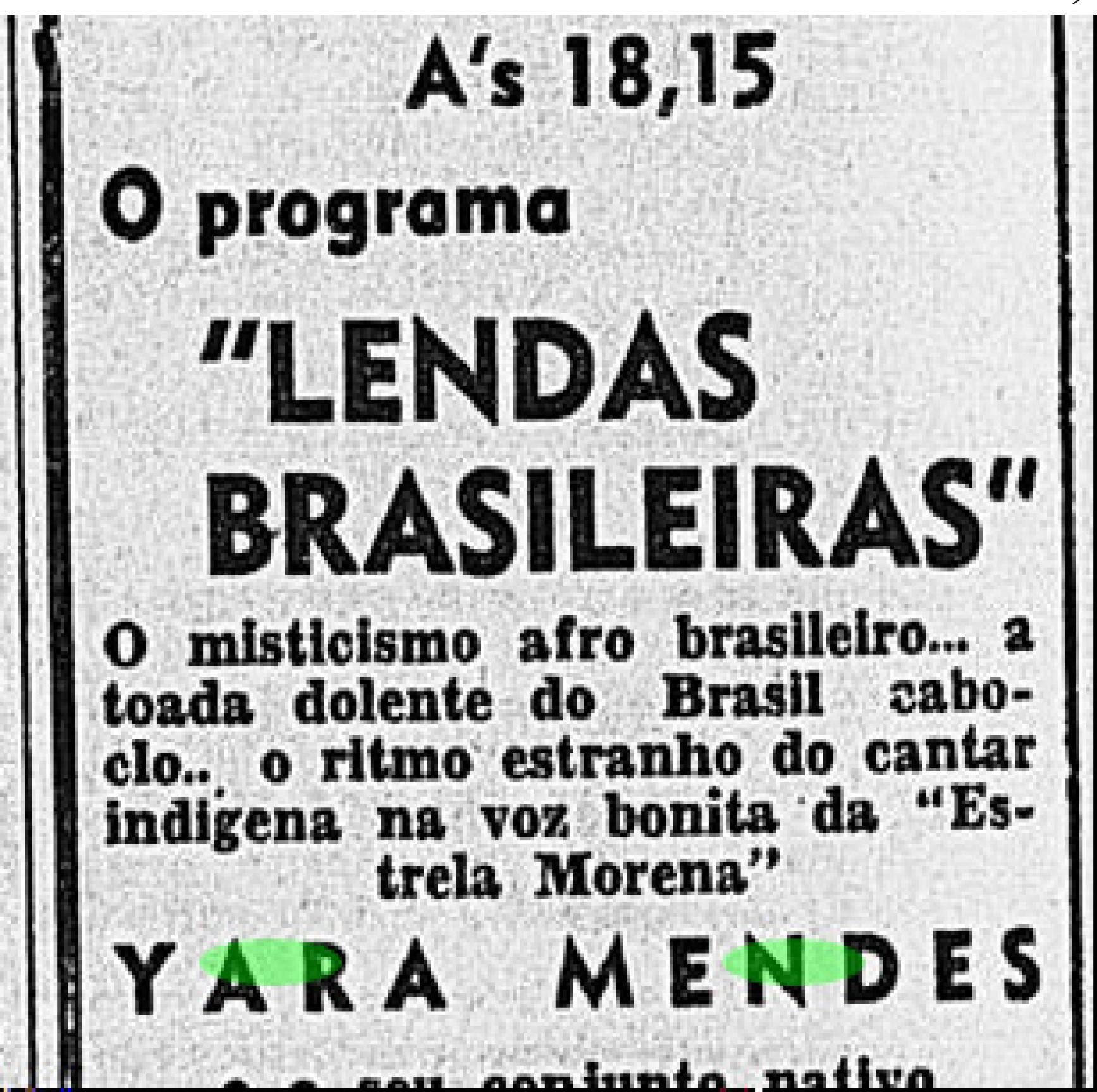

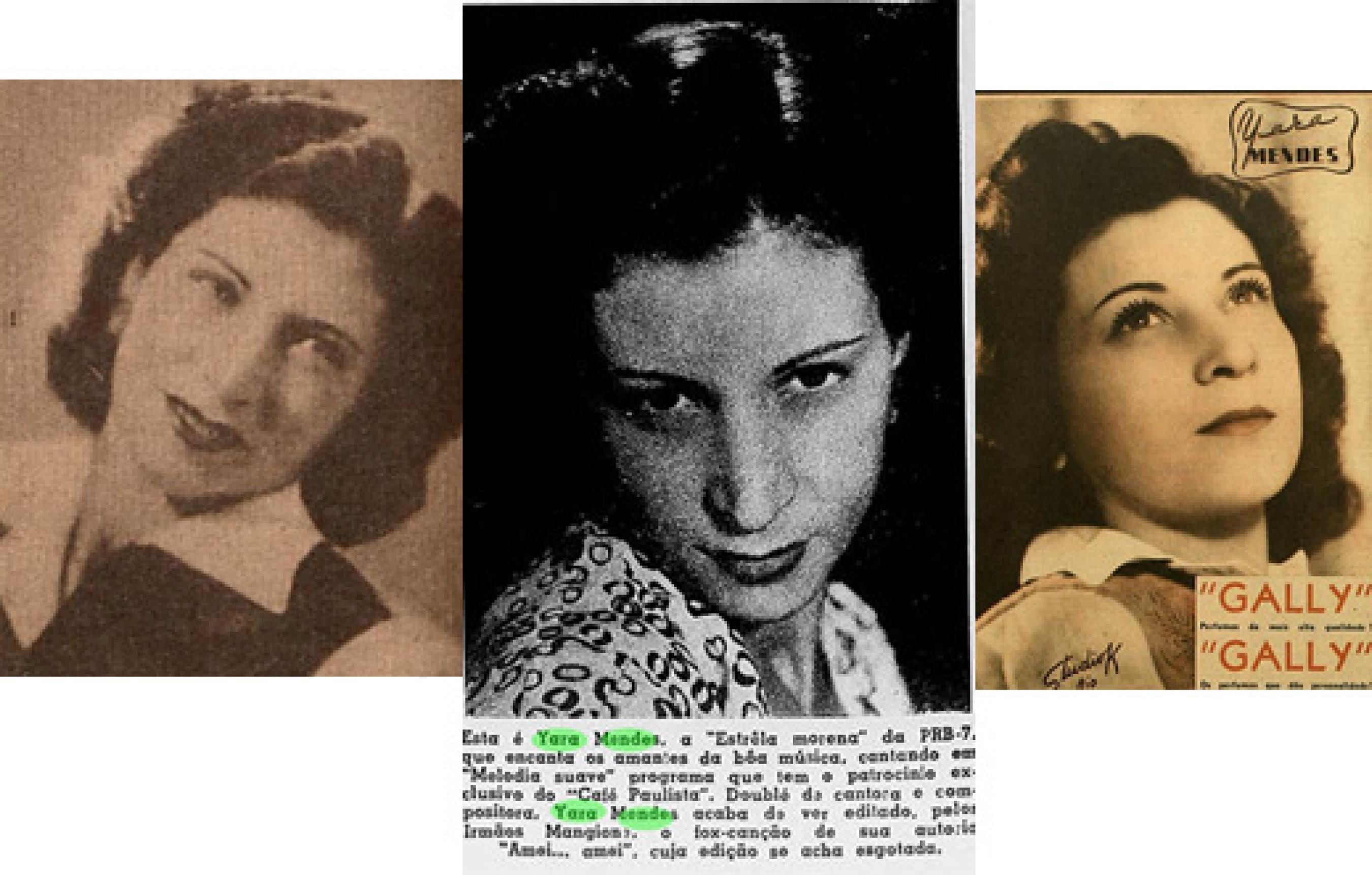

Edwiges was no longer able to get away from the limelight. António Ignácio, who continued to tutor the girl even when she decided to return to her mother's lap, managed to get her a good marriage, but the union was not long-lasting. In 1942, Edwiges, the girl with fair skin and green eyes, had already given the spotlight to Yara Mendes, the sensual “brunette star” who combined the “Afro-Brazilian mysticism” and the “strange rhythm of indigenous singing” in her “beautiful voice”, as the ad by Rádio Tupi (Tupi Radio Station) said, published in the Diário da Noite (Evening Post), on December 26th, 1942:

SOURCE: Diário da Noite, 1942.

PICTURE 11 ADVERTISEMENT FOR THE RÁDIO TUPI LENDAS E NARRATIVAS (TUPI RADIO STATION’S LEGENDS AND NARRATIVES) PROGRAM.

Although her career did not survive the golden age, the radio singer and crooner lady of the Cassino Atlântico made a success worthy of the front page of newspapers and magazine covers in the 1940s:

SOURCE: O Cruzeiro, 1943. Vida Doméstica, 1943. Vamos Ler, 1943.

PICTURE 12 NEWS AND MAGAZINE COVERS

To narrate is to brush history against the grain, including the official speech. The erasure of Edwige’s' transgressive trajectory and the invention of Yara Mendes is in step with the attempt to metamorphose the old world into the new world. The miscegenation approached only by the bias of the whitening process overlooks the copy and mimicry processes made white. Europeans, in an anthropophagic process, fed on the other racial groups. When we aim to understand Brazilian society from the perspective of imagined communities, we find the duality of the familiar/strang. Similar to what Kiening (2014) says about the symbolic production of wonderful beings, constituted through a cannibalistic practice, consumed as a travel souvenir. The prodigious resident starts to be commercialized through the tales of a universe of sensations. The situation experienced by Yara Mendes is a double twist of these narratives. Even though she is white and belongs to a family from Vila Real, Portugal, Edwiges takes on the artistic name of Yara, a Tupi name that means Queen of the Waters. We watched the passage of the white dove to the dark star Yara Mendes. Adjusted to the spotlight, the young Edwiges became objectified as one of the catalog items of the Sensual Gift of the Tropics. Among the “made in Brazil” wonders, we would have souvenirs of different species: human, environmental and cultural ones.

Conclusion

What can we find in our family albums, besides moving memories and funny jokes? The attentive journey to this important book allowed us to perceive the link between private memories and others’ experiences. When narrating our life stories, we offer historical and political testimonies of a time, a group, and an ever-changing territory. This “common me offers us an understanding of the interplay between the general narratives, which we see here as the attempt to build a national identity for the mixed-race people, such as in the Imagined Communities, by Anderson. Marias, Ermelindas, and Yaras lived the weight of the social inscriptions of their time on their bodies, giving away, facing, and concealing the political and discursive practices belonging to the gears of a barbarian capitalist regime. In everyday experiences, we feel the functioning of our society, like a place that Didi-Huberman (2011, p. 41) called “the mercantile, prostitutional kingdom, of generalized tolerance”. The existence of the woman weighed on the marriage with the foreigner that represented a way of welcoming the poor and surplus population of Europe. Inwardly, the “Redenção de Cam” (Redemption of Cam) camouflaged the perpetuation of slavery and the physical and cultural genocide of the black people that used to be dressed as love. The womanhood had been exploited by the just-born press, which did not shy away from playing lightly with the social positions and representation destined to woman.

Not everything resulted in the rubble, there is an ethical and aesthetic way of resistance in the sacred, in art, and in studies, which made up ways of recovering themselves. The perception we have of it allowed the writing of the present text along the lines of what Benjamin (1994, p. 225) says: “The gift of awakening the sparks of hope in the past is an exclusive privilege of the historian convinced that the dead will also not be safe if the enemy wins. That enemy has not ceased to win”.

The careful overlapping of life histories, through documentary sources and memories brought by heart, allowed us to perceive the mixtures and correlations between personal histories and world-historical plots. In the corners of desire, horizons made up of disputes between forces of the communities that we imagine or do not share are rising and falling apart. In the symbolism that make up the existent territories, fall over the subjects - as the only instance of self-responsibility - the threads, the correlation with strength, the consequences, fortunes, and misfortunes.

However, how to get ahold of your story if it begins to be written and is the target of clashes from so many different times and places? More than just an evaluative place, the narratives themselves allow us to “listen with our eyes” and “listen with our hearts” to the combats and confrontations that make up people, as common sense teaches us: Those who look at me like this, do not know what I have been through…

REFERÊNCIAS

ANDERSON, Benedict. Comunidades Imaginadas. Reflexões sobre a origem e a difusão do nacionalismo. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2008. [ Links ]

ARQUIVO DISTRITAL DO PORTO. Registo de passaportes- Livro 238. Porto, Portugal, 2013. Disponível em: http://pesquisa.adporto.arquivos.pt/viewer?id=411623. Acesso em: jul. 2020. [ Links ]

BENJAMIN, Walter. Obras Escolhidas. Magia e Técnica, Arte e Política. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1994. [ Links ]

BHABHA, Homi K. O local da cultura. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2001. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública. Sistema de Informações do Arquivo Nacional. Brasília, DF: SINAN, 2020. Disponível em: http://sian.an.gov.br/sianex/consulta/login.asp. Acesso em: 26 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

BROCOS, Modesto. A Redenção de Cam. 1895. 1 original de arte, óleo sobre tela, 199 x 166 cm. Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional de Belas Artes. Disponível em: http://enciclopedia.itaucultural.org.br/obra3281/a-redencao-de-cam. Acesso em: 26 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

CAMINHA, Pero Vaz de. A Carta de Pero Vaz de Caminha. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2019. [ Links ]

CASTRO, Andreia Alves Monteiro de. Cores, cheiros e sabores - Corpo feminino e literatura no Século XIX. Terceira Margem, Rio de Janeiro, Ano 24, n. 43, p. 90-106, maio-ago. 2020. [ Links ]

CERTEAU, Michel de. A escrita da História. Rio de Janeiro: Forense, 1982. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A História Cultural entre práticas e representações. Tradução de Maria Manuela Galhardo. Lisboa: Difusão, 1990. [ Links ]

CORBIN, Alain. Saberes e Odores. São Paulo: Cia. das Letras, 1987. [ Links ]

CRENSHAW, Kimberle. Interseccionalidade na discriminação de raça e gênero, 2012. Disponível em: https://nesp.unb.br/popnegra/images/library/Kimberle-Crenshaw-Intersecionalidadenadiscriminaoderaaegenero.pdf. Acesso em: 29 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

DIDI-HUBERMAN, Georges. Sobrevivência dos Vaga-lumes. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG , 2011. [ Links ]

ENGEL, Magali Gouveia. Paixão e morte na virada do século. Disponível em: http://www.observatoriodaimprensa.com.br/marcha-do-tempo/paixao-e-morte-na-virada-do-seculo. Acesso em: 29 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

FREYRE, Gilberto. Casa-Grande & Senzala. São Paulo: Global, 2005. [ Links ]

GANDÂVO, Pero de Magalhães. Tratado da Terra do Brasil: história da província Santa Cruz, a que vulgarmente chamamos Brasil. Brasília: Senado Federal, 2008. [ Links ]

GEORGE, Duby; PERROT, Michelle. Imagens da Mulher. Porto: Edições Afrontamento, 1992. [ Links ]

FANTASIO. Na Exposição II A Redenção de Cham.Gazeta de Noticias, Rio de Janeiro, 5 set. 1895, p. 1. Disponível em: http://www.dezenovevinte.net/egba/index.php?title=FANTASIO._FANTASIO_NA_EXPOSI%C3%87%C3%83O_II_A_REDEN%C3%87%C3%83O_DE_CHAM._Gazeta_de_Noticias%2C_Rio_de_Janeiro%2C_5_set._1895%2C_p. 1. Acesso em: julho, 2020. [ Links ]

KIENING, Christian. O Sujeito Selvagem. São Paulo: Edusp, 2014. [ Links ]

MATTOS, Maria Hebe. Políticas de reparação e identidade coletiva no meio rural: Antônio Nascimento Fernandes e o quilombo São José. Estudos Históricos, Rio de Janeiro, n. 37, p. 167-189, jan.-jun. 2006. [ Links ]

MUNANGA, Kabengele. Rediscutindo a mestiçagem no Brasil: identidade nacional versus identidade negra. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2019. [ Links ]

PERROT, Michele. Os silêncios e o corpo da mulher. In: O corpo feminino em debate. MATOS, Maria Izilda Santos de; SOIHET, Rachel (org.). São Paulo: Editora UNESP 2003. p. 13-27. [ Links ]

PERROT, Michele. Minha história das mulheres. Tradução de Angela M. S. Corrêa. São Paulo: Contexto, 2013. [ Links ]

QUILOMBO SÃO JOSÉ. Foto. Valença, RJ, 19 maio 2013. Facebook: Quilombo São José. Disponível em: https://www.facebook.com/437651249613493/photos/a.570338886344728/570338889678061. Acesso em: 26 jul. 2020. Facebook: usuário Facebook. Disponível em: link. Acesso em: data de acesso. [ Links ]

SANT'ANNA, Affonso Romano de. O canibalismo amoroso. Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 2011. [ Links ]

TORRES, Gênesis (org.). Baixada Fluminense: a construção de uma história: sociedade, economia, política. Rio de Janeiro: INEPAC, 2008. [ Links ]

Fontes:

A Batalha, ano II, n. 183, p. 3, 10 abr. 1930. [ Links ]

Correio da Manhã, ano XXX, n. 10875, p. 6, 10 abr. 1930. [ Links ]

Correio da Manhã, ano XXX , n. 1101719, p. 7, nov. 1930. [ Links ]

Crítica, ano II, n. 333, p.1, 11 dez. 1929. [ Links ]

Crítica, ano II , n. 337, p. 2. [ Links ]

Crítica, ano II , n. 346, p.1, 26 dez. 1929. [ Links ]

Diário Carioca, ano III, n. 735, p. 8, nov. 1930. [ Links ]

Diário da Noite, ano XIV, n. 365, p. 8, 26 dez. 1942. [ Links ]

Gazeta de Noticias, Rio de Janeiro, p. 1, 5 set. 1895. [ Links ]

O Cruzeiro, ano XV, n. 34, p. 36, 19 jun. 1943. [ Links ]

O Mequetrefe, ano I, n. 29, p. 1, 15 jul 1875. [ Links ]

Vamos Ler, ano VII, n. 354, capa. [ Links ]

Vida Doméstica, ano XXIV, 01, n. 309, p. 82, 12 dez. 1943. [ Links ]

1Translated by Alexandre Afonso. E-mail: alexandre.afonso@yessaocristovao.com.br

3Quilombo was a type of shelter for all the slaves who managed to run away from their owners. So that, quilombola was a former slave who would live with the others in the quilombo.

4Umbanda is a religion originated in Brazil with a lot of influence from the African Candomblé. Both believe in the spirits of nature and ancestors who, after life, live in a different spiritual plane.

Received: August 29, 2020; Accepted: November 08, 2020

texto em

texto em