Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educar em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0104-4060versão On-line ISSN 1984-0411

Educ. Rev. vol.37 Curitiba 2021 Epub 15-Nov-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.81545

DOSSIER - Creativity, emotion and education

Creativity in socio-interactional pedagogy and Waldorf Pedagogy: implications for working with the gifted students 1

( Secretaria Municipal de Educação de Curitiba. Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. E- mail: ferhellenrp@gmail.com

(* Universidade Federal do Paraná. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação. Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. E- mail: tania.stoltz795@gmail.com

This article is pioneer in the discussion of the phenomenon of creativity based on Vygotsky and Rudolf Steiner, relating it to work with gifted people. Its aim is to investigate creativity in the sociointeractionist approach and in Waldorf Education and its implications for working with gifted students. Apart from important differences, the proposals of Vygotsky and Steiner meet the needs of gifted students, especially when they emphasize significant teaching mediation. The teacher, as the main mediator, is responsible for the proposal of creative and aesthetic teaching aimed at the love of knowledge and life.

Keywords: Creativity; Giftedness; Vygotsky; Steiner

Este artigo é pioneiro na discussão do fenômeno da criatividade a partir de Vygotsky e de Rudolf Steiner, relacionando-o ao trabalho com superdotados. Seu objetivo é investigar a criatividade na abordagem sociointeracionista e na Pedagogia Waldorf e suas implicações para o trabalho com estudantes superdotados. À parte importantes diferenças, as propostas de Vygotsky e de Steiner vão ao encontro das necessidades de estudantes com altas habilidades/superdotação (AH/SD), principalmente quando ressaltam a mediação docente significativa. O professor, como principal mediador, é responsável pela proposta de ensino criativo e estético voltado ao amor ao conhecimento e à vida.

Palavras-chave: Criatividade; Altas habilidades/superdotação; Vygotsky; Steiner

Introduction

Nowadays, much is discussed about the theme of creativity. This phenomenon is multifaceted and contributes significantly to Education (CSIKSZENTMIHALYI, 2007; RENZULLI, 2016; BEGHETTO; KAUFMAN, 2017; STERNBERG, 2018; PISKE; STOLTZ, 2020; ALENCAR; FLEITH, 2010). This study chooses to approach two theories that could be taken as reference in a 21st century educational system focused on creative work, especially for gifted children, who require a differentiated education. In this sense, our goal is to investigate creativity in the social interactionist approach2 and in Waldorf Education and its implications for working with gifted students.

Social interactionism and creativity

Social interactionism, inspired by Vygotsky3 (2013, 1991), is a theory of learning based on interaction that integrates, inseparably, the affective and cognitive dimensions. Learning, in social interactionism, is understood based on historical, social, and cultural contexts. Learning opens channels for development and, in this sense, the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZDP) is fundamental and central. The zone of proximal development is the space between what the child has already mastered and what he or she has not yet mastered, but which with the help of other more capable people he or she may come to master (VYGOTSKY, 2007).

For John-Steiner (1985, 1995, 2000), Vygotsky's theory of human development defines creativity as a process that includes children's play, imagination, and fantasy. It is a transformative activity where emotion, meaning, and cognitive symbols are synthesized.

Stoltz et al. (2015) note that Vygotsky attributed great importance to the phenomenon of creativity, considered fundamental in the human activity of transforming reality and innovating forms of action in the environment in which each subject finds itself. “According to Vygotsky’s cultural-historical theory, creativity is inherent to the human condition, and it is the most important activity because it is the expression of consciousness, thought and language” (STOLTZ et al., 2015, p. 67).

In Vygotsky's works, the valuing of creativity, imagination, fantasy, and innovation is notorious. For Vygotsky (2009a, 2009b), creativity can be defined as the ability to create something new, being a fundamental aspect for the transformation of the social environment. Imagination is the basis of all creative activity and manifests itself fully in cultural life, enabling artistic, scientific, and technical creation. As for fantasy, it is the fundamental element in play, where children transit from the domain of imaginary situations to the domain of the rules of their sociocultural environment. Such aspects were important to Vygotsky and motivated him to participate in important artistic and intellectual movements.

Vygotsky's proposal, with reference to creativity, turns to esthetic education. Esthetic education should not be subordinated to morals, to knowledge related to other disciplines, or simply intended to offer pleasurable activities that provoke the desire to learn. For Vygotsky (2001), esthetic education should be part of the totality of our life, and the role of the teacher is

To introduce aesthetic education into life itself. Art transfigures reality not only in building fantasy, but also in the actual production of objects and situations. One’s home and clothing, conversation and reading, and the way one walks, all these can equally serve as the noblest material for esthetic production (VYGOTSKY, 2001, p. 352, our translation).

Esthetic education is part of the culture of each social group and part of a creative form of teaching where it must be integrated into everyday school life. In his works, one can see that, for Vygotsky (1989), creativity is an aspect that emerges in culture in a diversified manner and as a result of each social context. In culture, one can perceive the expression of each nation and the manifestation of creation and invention. This attribute can be considered cultural and universal, it is a complex phenomenon that can be developed in all people differently because it depends on how and where its development occurs.

Vygotsky (1997, 2009a, 2009b) defines culture as a product of both social life and also of the social activity of each human being. For Vygotsky, every inventor, even a genius, is always a consequence of his time and his environment (STOLTZ; PISKE 2012; PISKE et al., 2017).

Stoltz (2010) emphasizes that the cultural constitution of each subject is influenced by the action of other subjects who are also in their social environment. Vygotsky (1989) states that we become ourselves through other subjects. Based on this principle, the essence of the cultural development process is logically related to social interactions. Cultural development is the process where the social environment establishes meaning for the subject, making him/her a social and cultural being. Signification becomes the universal mediator in this process and the bearer of this signification is the other, the symbolic place of historical and cultural humanity (VYGOTSKY, 1989).

Development of creativity has a transforming power and is expressed in a differentiated way, because the act of creating and inventing does not only take place in great discoveries and fabulous inventions, but whenever any human being combines ideas, formulates solutions, comes up with something innovative, modifies their environment and imagines situations that develop their creative potential. Based on the higher psychological processes4 each human being relies on their cognitive resources that are related to their perception, attention, abstract thinking, and imagination in order to develop their creativity. For Vygotsky (2009a):

According to an analogy made by a Russian scientist, electricity acts and manifests itself not only where there is a great storm and blinding lightning, but also in the pocket flashlight. Similarly, creation, in fact, exists not only when great historical works are created, but everywhere that man imagines, combines, modifies and creates something new, even if this something new looks like a tiny speck compared to the creations of geniuses. If we take into account the presence of collective imagination, which unites all these often insignificant grains of individual creation, we will see that part of everything created by mankind belongs to the anonymous and collective creative work of unknown inventors (VYGOTSKY, 2009a, p. 15-16, our translation).

For Vygotsky (2004) it is fundamental to touch the human being through their emotions during the process of creation and during the act of teaching. Teaching that integrates emotion and cultivates it during each moment of learning instigates the desire to learn and awakens curiosity. Creativity, in turn, is the principle of the creative process and should be addressed through artistic practices. To achieve this objective, it is crucial to set goals and act to develop creativity through playful teaching.

The Vygotskyan theory understands that psychological functioning occurs in the best way if there is mediation that works on each subject's potential continuously and efficiently. Mediation is so important that it is precisely through mediation that potentialities and imagination emerge and acquire more life. It works on the child's potential zone, relative to what it has not yet mastered, so that with interaction with more capable subjects, what was previously potential (knowledge that the child has not yet mastered) can become real (the child’s own domain).

Piske and Stoltz (2020) point out that in teaching, the teacher's mediation could expand horizons by establishing educational measures where the gifted child goes beyond the standardized limits of education. In this sense, imagination, creation, and invention are aspects to be explored and motivated to seek the true meaning of teaching. A child learns a lot by playing, interacting with other children. When playing, their greatest fantasies come to the surface. Vygotskyan theory focuses on the social and cultural aspect of each subject in everyday interactions. In child development, it approaches play from the understanding that it is the social that is the basis for action in the child's playing activity. The act of playing is so important that Vygotsky (2007) highlights that play creates zones of proximal development and that these provide qualitative leaps in child development and learning.

For Leontiev (1994), a follower of Vygotsky, playing is the moment when the most relevant changes take place in a child’s psychic development. Playing is the transition path to higher levels of development during the child's life. Thus, Leontiev (2005) emphasizes activities based on playing, in which each child can discover many solutions and can also understand relationships between itself and its environment. Through play, the child is able to analyze its limits and capabilities, as well as being able to compare its abilities with other children in its social group. Playing enables children to acquire cultural codes and understand their social function in society. Leontiev (1994) states that playing changes over the course of different age groups and in relation to the socio-historical context. After a child masters speech, games involving exercise gradually decrease and give way to o symbolic games.

Vygotsky (2007, 2009a, 2014a, 2014b) emphasizes that playing is fundamental to the social and intellectual development of each child, because the processes of representation and symbolization lead them to abstract thinking during the games they play. Therefore, it is possible to emphasize that playing instigates imagination, fantasy, goes beyond reason, and motivates the child to have enjoyable social experiences during the teaching and learning process in a creative way. According to Vygotsky (2007):

[...] drawing and playing should be preparatory stages for the development of children's written language. Educators must organize all these actions and the whole complex process of transition from one type of written language to another. They must accompany this process through its critical moments, up to the point of children discovering that they can draw not only objects, but design their speech. If we wanted to summarize all these practical demands and express them in a unified way, we could say that what must be done is to teach children written language and not just how to write letters of the alphabet (VYGOTSKY, 2007, p. 145, our translation).

It is in the creative and engaging context that the various possibilities of invention emerge and enable the development of creativity in social interactionism.

Piske, Stoltz and Camargo (2016) explain that according to Vygotsky, gifted students need different procedures in the classroom. As such, teacher mediation will have to intervene during the development of special forms of talent and potentialities. This mediation will make the difference so that these students have access to specialized care where their creativity can be developed. In this aspect, Vygotsky (1998, 2009a, 2009b) points out that children's fantasy has no restraint. Creative activity is based on the ability of our brain to combine different things, and depends on the richness and diversity of our experiences. Therefore, imagination originates from experiences over the course of life.

Waldorf Education and creativity

The principles of Waldorf Education, founded by Rudolf Steiner (1985, 1996), are centered on the freedom of each human being to act, feel, and think. Veiga (2012, 2014, 2015) explains that Waldorf Education is based on the attempt to ground teaching and learning in a holistic view of the human being.

Waldorf Education is fundamental in achieving quality education that aims to meet students’ needs in an integral way (PISKE; STOLTZ, 2020; STOLTZ; WIEHL, 2019a; 2019b; VEIGA, 2015; RANDOLL; PETERS, 2015; STOLTZ; WEGER, 2015; BACH JR, 2015). Waldorf Education sees nature and the universe, cognitive, emotional and volitive development as forming a kind of unity, there is no exclusivity as far as intellectuality is concerned because the fundamental objective is to emphasize that each individual is perceived as an integral being in all dimensions of their development (STOLTZ; VEIGA; ROMANELLI, 2015; PISKE; STOLTZ, 2014; PISKE, 2018; PISKE; STOLTZ, 2020).

According to Bach Jr. (2012, p. 12, our translation) anthroposophical thinking in Waldorf Education encompasses "affective and volitional dimensions in child development, by influencing the soul of teaching and expanding human relationships with a spiritual focus". Waldorf Education does not reduce life to the application of equations, to the one-sided considerations of what is only sensory; rather, Waldorf Education goes beyond the sensory aspect by deepening a broader, spiritual knowledge. "Spirituality as referred to here relates to a dimension of human profoundness, a new way of experiencing and living as a human being, appropriate to the moment in question" (BACH JR., 2007, p. 11, our translation). Waldorf Education is based on Anthroposophy, the science of the spirit and philosophy of life that means human wisdom, integrates scientific, artistic and spiritual thoughts, and is related to the most intimate human essence with regard to oneself and one’s relations with the universe and nature. Anthroposophy understands the human being in its physical, psycho-emotional, soul and spiritual aspects (STEINER, 2000a, 2013).

Keim (2014) explains that Steiner defines education as "a process of social interaction that focuses on reaching the immaterial dimension of the person, with a view to expanding their capacity to act for the dignity and emancipation of life" (KEIM, 2014, p. 193, our translation). Thus, Waldorf Education focuses on integral human development and its transdisciplinary character leads to innovative teaching. Espírito Santo (2008) points out that Waldorf Education can be considered pioneer in providing transdisciplinary practice, developed on the basis of creative living. Waldorf Education seeks to attend to all stages of child development. The Waldorf Education team is dedicated to make this teaching an art that educates children in an integral way, involving doing, feeling and thinking (STOLTZ; WEGER, 2015).

When we turn our gaze to the education of gifted children in Waldorf Education, we can consider that their potentialities will be developed as a whole. As far as gifted children are concerned, in Waldorf Education they will be able to practice the same activities as children of their own group, there is no specific form of teaching for them, and grade acceleration is not encouraged. The focus of Waldorf Education is on interaction between children and their performance that makes them free to do their activities with autonomy. In Waldorf Education, there is no interest in fostering a specific area of the gifted child, but rather a commitment to creative experience and depth of knowledge in different areas.

Piske and Stoltz (2020) consider that when a gifted child is placed within Waldorf Education it should not have great difficulties, because the pedagogical method used is broad and seeks to involve feelings, emotions, as well as cognitive development. Moreover, the curriculum is planned to meet the various stages of development, favors the full extent of the potential of each child, and deals with child development as a whole, seeking to awaken and enhance all abilities at all stages. It is possible that when a gifted child is taught in this way it may become a subject with broad culture, a human being well informed about the world and the history of humanity, having access to various practical and artistic skills, showing reverence and constant contact with nature, acting with initiative and freedom of expression concerning various subjects. As it is a completely creative form of education, the gifted child can develop its creativity in a broad and continuous way.

Waldorf Education respects all children's specificities and characteristics, valuing their potentialities and talents, emphasizing that human growth and development do not happen in a linear manner and, consequently, cannot be measured or understood in the same way.

By considering the human being as a free being, Waldorf Education organizes its curriculum considering individual freedom and the stages of development, which are called seven-year stages, as follows. The first seven years of life are dedicated to knowledge and maturation of the body. Imitation is the basis of learning. A child invents and creates diverse games using its imagination. Signs of physical maturity will appear at around age seven. From seven to fourteen years of age, artistic activities bring out feelings and emotions. Thus, these activities work toward ethical behavior, that is, the feeling of fraternity with others and reverence toward people and nature. From fourteen to twenty-one years of age, thoughts, logical reasoning, and a critical sense of the world begin to be structured in an abstract way. The basic virtue that the adolescent desires is the search for self-knowledge and knowledge of those around them (BARFIELD, 2020).

Carlgren and Klingborg (2006) also explain that one of the ways of working with art in Waldorf education includes Eurythmy, or art of movement. Eurythmy, developed by Rudolf and Marie Steiner, can have a scenic, pedagogical or therapeutic character. This art seeks to make music and speech visible, addresses the themes of the curriculum, working with geometric shapes, rhyme, metrics, stories, among other subjects, enabling greater self-discipline, concentration, and sensitivity in seeing things, touching them, feeling them, and interacting with the outside world. This art of movement enables sensitivity and respect for others, respect for their differences, self-regulation or self-mastery in acting, thinking, and speaking. Furthermore, art provides "Steiner's conception of the other and the phenomenon of otherness, as it is based on Goethe's distinction between the analytical intellect (rationality) and the productive intellect (intuitive thinking)" (VEIGA, 2010, p. 38, our translation).

Sensitivity is an essential aspect that gives meaning to knowledge. Schiller (2013) explains that the path to intellectual development has to be opened by the heart: "The role of affectivity, linked to the process of education and cognition, lies in the foundation and cultivation of values of relationship with the phenomenon of life" (BACH JR., 2010, p. 279, our translation). Besides empirical and logical science, Waldorf Education opts for a form of teaching that unites affectivity and rationality, because both are extremely important for education that proposes integral development of the child. In other words, there is no efficient cognitive development if it is not based on an affective attitude, on a form of teaching that integrates the emotion of learning and achieving that which is acquired through feelings.

In Waldorf Education, feelings are touched by what is beautiful. The beautiful fully infects the soul by a stimulus that transcends the sensory aspect. Human sensitivity comes from the beauty that is conferred to it when witnessing an artistic work, an esthetic state that occurs in the proportion and the extent that involves each subject when experiencing what is beautiful. "Through beauty, the sensitive human being is led to form and thought; through beauty, the spiritual human being is led back to matter and delivered back to the sensitive world." (SCHILLER, 2013, p. 87, our translation).

Piske and Stoltz (2020) point out that human beings have a need for contemplation that unites them with the esthetic aspect of art, of the beauty contained in artistic expressions. The esthetic experience is promoted in Waldorf Education in order to develop freedom (STOLTZ; WIEHL, 2019b). Beauty, however, does not lack matter, it is not on a level of abstraction that makes it impossible for us to experience it intentionally. Henriques (2008) explains that in every esthetic experience there is an amalgam of objectivity and subjectivity.

Esthetic pleasure derives from sensitivity in perceiving what is beautiful in harmonies that are contained in art, which is the supreme form of expression. "It is in the sensitive itself, in the very act of perceiving, that esthetic pleasure resides: in the direct perception of harmonies and rhythms that hold, in themselves, their truth" (DUARTE JR., 2002, p. 91, our translation). In Waldorf Education, "The esthetic state is a new mental disposition, when it comes into existence it is for the sake of affirming the humanity of the subject" (BACH JR., 2012, p. 21, our translation). Sensitivity and reason are simultaneously activated in the esthetic state that can be considered precise, real, and active in the process of creation.

Although Steiner (1997, 2013, 2000a, 2000b) does not establish a relationship with the teaching of gifted children, he values and emphasizes the importance of affectivity, emotions, and feelings during learning. Similarly, studies in the area of giftedness point to the relevance of education that can meet the socioemotional needs of the gifted child (KANE; SILVERMAN, 2014; KANE, 2016, 2018; PETERSON, 2014; LUBART, 2003; MAUD, 2013; PIECHOWSKI, 2014; PFEIFFER, 2016; PEREIRA et al., 2016; GROSS, 2014, 2016; ALENCAR, 2007, 2014; PISKE, 2013, 2018; PISKE; STOLTZ, 2018, 2020), among others.

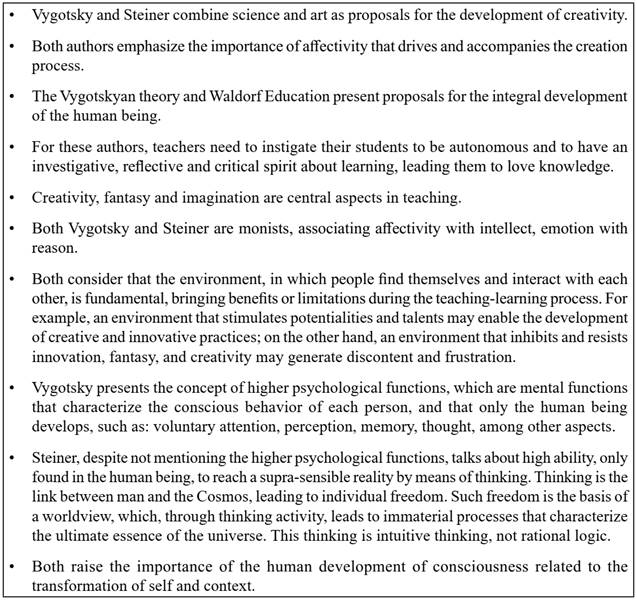

Convergences between Vygotsky and Steiner

Vygotsky and Rudolf Steiner dialogue in certain aspects and contribute to Education in a broad and deep way, making us reflect on a quality and creative form of teaching based on their enriching proposals. Convergences between Vygotsky's social interactionist theory and Steiner's Waldorf Education can be seen in the chartbelow.

SOURCE: Piske (2018), Piske and Stoltz (2020).

CHART 1 - CONVERGENCES5 BETWEEN VYGOTSKY'S THEORY AND STEINER'S WALDORF EDUCATION

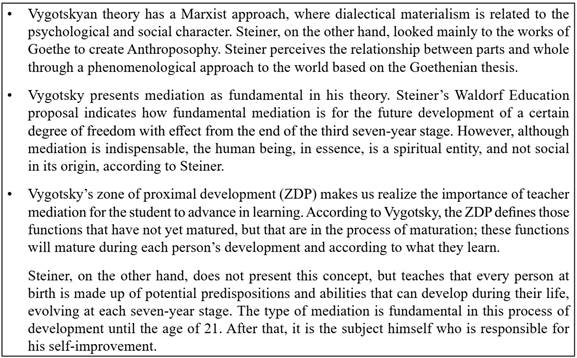

Divergences6 between Vygotsky and Steiner

Vygotsky and Steiner diverge in several aspects, their theories present antagonistic issues, however, it can be said that they complement each other when it comes to aspects of human development. If, in the case of Vygotsky, his theory focuses on social interactionist relations and the development of consciousness, in the case of Steiner, his worldview requires an understanding beyond the material aspect, transcending materiality and advancing to the spirituality of each being. The chart below indicates the divergences found.

SOURCE: Piske (2018), Piske and Stoltz (2020).

CHART 2 - DIVERGENCES BETWEEN VYGOTSKY'S THEORY AND STEINER'S WALDORF EDUCATION

In both in the convergences and the divergences between the theories, Vygotsky's sociointeractionism and Steiner's Waldorf Education address educational measures capable of dealing with the specificities and needs of each student, providing the possibility of reflection, autonomy, freedom of expression, investigative and critical spirit for a comprehensive and quality education that meets their needs. Both go beyond reductionism and fragmented teaching, pointing out the importance of learning in an inter and transdisciplinary way.

Final considerations

The objective was to investigate creativity in the social interactionist approach and in Waldorf Education and its implications for working with gifted students. Discussion based on these great thinkers, Vygotsky and Steiner, is extremely important for education. Although in their theories there is no in-depth discussion about the education of gifted students, the authors draw attention to the need for appropriate procedures for a form of teaching that allows progress at each stage of development, emphasizing playful teaching. In this aspect, teaching will depend on the mediation of a teacher trained to deal with the special educational needs of these students (PISKE; STOLTZ, 2020).

Vygotsky's and Steiner's proposals meet the needs of gifted students, especially when they emphasize that mediation must be meaningful. Teachers, as the main mediators, are responsible for awakening in students a love for knowledge and for life. In addition, they can enable students to make progress in the various areas of knowledge, mainly through creative teaching. In this sense, their progress will depend on teachers being prepared to perceive and deal with the needs of each student, expanding their knowledge, especially in their area(s) of interest. Expansion of this knowledge will rely fundamentally on playing and artistic practices that will comprise significant and quality education with the purpose of meeting the needs of the emotional, social, and cognitive dimensions of these students.

REFERENCES

ALENCAR, Eunice Maria Lima Soriano de. Características socioemocionais do superdotado: questões atuais. Psicologia em estudo, Maringá, v. 12, n. 2, p. 371-378, 2007. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br /pdf/pe/v12n2/v12n2a18.pdf . Acesso em: 22 out. 2021. [ Links ]

ALENCAR, Eunice Maria Lima Soriana de; FLEITH, Denise. Criatividade na educação superior: fatores inibidores. Avaliação, Sorocaba, v. 15, p. 201-206, 2010. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-40772010000200011. Acesso em: 22 out. 2021. [ Links ]

ALENCAR, Eunice Maria Lima Soriano de. Ajustamento Emocional e Social do Superdotado: Fatores Correlatos. In: PISKE, Fernanda H. R et al. (org.). Altas habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD): Criatividade e emoção. Curitiba: Juruá, 2014. p. 149-162. [ Links ]

BACH JR., Jonas. Educação ecológica por meio da estética na Pedagogia Waldorf. 2007. 239 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2007. [ Links ]

BACH JR, Jonas. A filosofia de Rudolf Steiner e a crise do pensamento contemporâneo. Educar em revista, Curitiba, n. 36, p. 277-280, 2010. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://www.scielo.br/pdf/er/n36/a18n36.pdf . Acesso em:10 nov. 2010. [ Links ]

BACH JR, Jonas. A pedagogia Waldorf como educação para a liberdade: reflexões a partir de um possível diálogo entre Paulo Freire e Rudolf Steiner. 2012. 413 f.Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2012. [ Links ]

BACH JR, Jonas. O pensar intuitivo como fundamento de uma educação para a liberdade. Educar em revista, Curitiba, n. 56, p. 131-145, 2015. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://www.scielo.br/pdf/er/n56/0101-4358-er-56-00131.pdf . Acesso em:11 nov. 2015. [ Links ]

BARFIELD, Owen. Rudolf Steiner - Uma apresentação. Tradução de Waldemar W. Setzer. [S. l.]: Sociedade Antroposófica Brasileira. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://www.sab.org.br/antrop/Barfield_on_Steiner.htm . Acesso em: 10 jan. 2020 2020. [ Links ]

BEGHETTO, Ronald A.; KAUFMAN James, C. Theories of creativity. In: PLUCKER, Jonathan A. (ed.). Creativity and innovation: Theory, research, and practice. Abingdon, UK: Prufrock Press, 2017. p. 35-47. [ Links ]

CARLGREN, Frans; KLINGBORG, Arne. Educação para a liberdade: a pedagogia de Rudolf Steiner. São Paulo: Escola Waldorf Rudolf Steiner, 2006. [ Links ]

CSIKSZENTMIHALYI, Mihaly. Aprender a fluir. Barcelona: Kairós, 2007. [ Links ]

GROSS, Miraca U. M. Issues in the Social-Emotional Development of Intellectually Gifted Children. In: PISKE, Fernanda, H. R. et al. (org.). Altas habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD): Criatividade e emoção. Curitiba, Juruá, 2014. p. 85-96. [ Links ]

GROSS, Miraca U. M. Developing programs for gifted and talented students. In: PISKE, Fernanda, H. R. et al. (org.). Altas habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD) e Criatividade: Identificação e Atendimento. Curitiba: Juruá, 2016. p. 61-75. [ Links ]

HENRIQUES, José C. Significação ontológica da experiência estética: a contribuição de Mikel Dufrenne. 2008.174 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Estética e Filosofia da Arte) - Instituto de Filosofia, Artes e Cultura da Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, 2008. [ Links ]

JOHN-STEINER, Vera. Notebooks of the mind: Explorations of thinking. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1985. [ Links ]

JOHN-STEINER, Vera. Cognivite pluralism: A sociocultural approach. Mind, Culture and Activity, v. 2, n. 1, p. 2-11, 1995. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039509524680. Acesso em:22 out. 2021. [ Links ]

JOHN-STEINER, Vera. Creativy collaboration. Oxford, UK; New York: Oxford University Press. 2000. [ Links ]

KANE, Michele. Gifted Learning Communities: Effective Teachers at Work. In: PISKE, Fernanda H. R. et al. (org.) Altas habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD) e Criatividade: Identificação e Atendimento. Curitiba: Juruá, 2016. p. 77-93. [ Links ]

KANE, Michele. Supporting the Affective Needs of Creatively Gifted children at Home and at School. In: PISKE, Fernanda H. R. et al. (org.). Educação de superdotados e talentosos: emoção e criatividade. Curitiba: Juruá, 2018. p. 63-74. [ Links ]

KANE, Michele; SILVERMAN, Linda K. Fostering Well-Being in Gifted Children: Preparing for an Uncertain Future. In: PISKE, Fernanda, H. R. et al. (org.). Altas habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD): Criatividade e emoção. Curitiba: Juruá, 2014. p. 67-84. [ Links ]

KEIM, Ernesto, J. Ontologia de Steiner e Freire e o Bem Viver como Agentes de Libertação por Meio da Educação. In: VEIGA, Marcelo da; STOLTZ, Tania (org.). O significado do pensamento filosófico para a Pedagogia Waldorf. Campinas, São Paulo: Alínea, 2014. p. 09-32. [ Links ]

LEONTIEV, Alexis N. Os princípios psicológicos da brincadeira pré-escolar. In: VYGOTSKY, Lev, S.; LURIA, Alexander R.; LEONTIEV, Alexis N. (org.). Linguagem, desenvolvimento e aprendizagem. São Paulo: Moraes, 1994. [ Links ]

LEONTIEV Alexis, N. Conversas com Vigotski [Beceda c Vigotskim]. In: LEONTIEV, Alexis N. Stanovlenie psikhologuii deiatelnosti: Rannieraboti. Moscou: Smisl, 2005. p. 231-237. [ Links ]

LUBART, Todd et al. Psychologie de lacréativité. Paris: Armand Colin. 2003. [ Links ]

MAUD, Besançon. Creativity, Giftedness and Education. Gifted and talented International Journal, Paris, v. 28, n. 1-2, p. 149-161, 2013. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://hal-univ-paris10.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01393542/document . Acesso em: 20 jan. 2017. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, Nielsen et al. University-Based Programs for Gifted Students. In: PISKE, Fernanda H. R. et al.(org.). Altas habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD) e Criatividade: Identificação e Atendimento. Curitiba: Juruá, 2016. p. 123 -143. [ Links ]

PETERSON, Jean S. Paying Attention to the Whole Gifted Child: Why, When, and How to Focus on Social and Emotional Development. In: PISKE, Fernanda H. R. et al.(org.). Altas habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD): Criatividade e emoção. Curitiba: Juruá, 2014. p. 45-66. [ Links ]

PFEIFFER, Steven. Leading Edge Perspectives on Gifted Assessment. In: PISKE, Fernanda H. R. et al. (org.) Altas habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD) e Criatividade: Identificação e Atendimento. Curitiba: Juruá, 2016. p. 95-122. [ Links ]

PIECHOWSKI, Michael. Identity. In: PISKE, Fernanda H. R. et al. (org.). Altas habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD): Criatividade e emoção. Curitiba, Juruá, 2014. p. 97-114. [ Links ]

PISKE, Fernanda Hellen Ribeiro. O desenvolvimento socioemocional de alunos com altas habilidades/superdotação (AH/SD) no contexto escolar: contribuições a partir de Vygotsky. 2013. 166 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2013. [ Links ]

PISKE, Fernanda Hellen Ribeiro. Altas habilidades/superdotação (AH/SD) e criatividade na escola: o olhar de Vygotsky e de Steiner. 2018. 287 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal do Paraná. Curitiba, 2018. [ Links ]

PISKE, Fernanda Hellen Ribeiro; STOLTZ, Tania. Ciência e arte na educação de superdotados: um olhar a partir de Steiner. In: VEIGA, Marcelo, de; STOLTZ, Tania (org.). O pensamento de Rudolf Steiner no debate científico. São Paulo: Alínea, 2014. p. 165-180. [ Links ]

PISKE, Fernanda Hellen Ribeiro; STOLTZ, Tania; CAMARGO, Denise. A compreensão de Vigotski sobre a criança com altas habilidades/superdotação, genialidade e talento. In: PISKE, Fernanda Hellen Ribeiro et al. (org.). Altas habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD) e Criatividade: Identificação e Atendimento. Curitiba: Juruá . 2016. p. 207-217. [ Links ]

PISKE, Fernanda Hellen Ribeiro; STOLTZ, Tania. Afetividade e criatividade na educação de superdotados: uma proposta a partir da ludicidade. In: VIRGOLIM, Angela(org.). Altas Habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD): processos criativos, afetivos e desenvolvimento de potenciais. Curitiba, Juruá, 2018. p. 201-212. [ Links ]

PISKE, Fernanda Hellen Ribeiro; STOLTZ, Tania. Altas Habilidades/Superdotação (AH/SD) e Criatividade: Contribuições do Sociointeracionismo de Vygotsky e da Pedagogia Waldorf de Rudolf Steiner. Curitiba: Juruá, 2020. [ Links ]

PISKE, Fernanda Hellen Ribeiro et al. The Importance of Teacher Training for Development of Gifted Students’ Creativity: Contributions of Vygotsky. Creative Education, [S. l.], v. 8, n. 1, p. 131-141, 2017. Disponível em: http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2017.81011. Acesso em: 23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

RANDOLL, Dirk; PETERS, Jürgen. Empirical Research on Waldorf Education. Educar em revista, Curitiba, n. 56, p. 33-47, 2015. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.41416. Acesso em:11 nov. 2016. [ Links ]

RENZULLI Joseph, S. The three-ring conception of giftedness: A developmental model for promoting creative productivity. In: REIS, Sally M. (ed.). Reflections on gifted education: Critical works by Joseph S. Renzulli and colleagues. Abington, UK: Prufrock Press, 2016. p. 55-90. [ Links ]

SCHILLER, Friedrich. A educação estética do homem numa série de cartas. Tradução de Roberto Schwarz e Márcio Suzuki. São Paulo: Iluminuras. 2013. [ Links ]

STEINER, Rudolf. Verdade e Ciência. São Paulo: Antroposófica, 1985. [ Links ]

STEINER, Rudolf. A educação da criança: segundo a Ciência Espiritual. 3. ed. São Paulo: Antroposófica, 1996. [ Links ]

STEINER, Rudolf. Antropologia meditativa: contribuição à prática pedagógica: quatro conferências proferidas em Stuttgart (Alemanha) de 15 a 22 de setembro de 1920. São Paulo: Antroposófica , 1997. [ Links ]

STEINER, Rudolf. Filosofia da liberdade: fundamentos para uma filosofia moderna: resultados com base na observação pensante. Segundo método das ciências naturais. São Paulo: Antroposófica , 2000a. [ Links ]

STEINER, Rudolf. A prática pedagógica: segundo o conhecimento científico-espiritual do homem. São Paulo: Antroposófica, 2000b. [ Links ]

STEINER, Rudolf. A arte de educar baseada na compreensão do ser humano. São Paulo: Antroposófica, 2013. [ Links ]

STERNBERG Robert, J. A triangular theory of creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, Washington, v. 12, n. 1, p. 50-67, 2018. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000095. Acesso em:23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

STOLTZ, Tania. Por que Vygotsky na educação?In: RAMOS, Elisabeth C.; FRANKLIN, Karen (org.). Fundamentos da educação: Os diversos olhares do educar. Curitiba: Juruá , 2010 p. 171-181. [ Links ]

STOLTZ, Tania; PISKE, Fernanda Hellen Ribeiro. Vygotsky e a questão do talento e da genialidade. In: MOREIRA, Laura Ceretta; STOLTZ, Tania (org.). Altas habilidades/superdotação, talento, dotação e educação. Curitiba: Juruá , 2012. p. 251-259. [ Links ]

STOLTZ, Tania et al. Creativity in Gifted Education: Contributions from Vygotsky and Piaget. Creative Education, [S. l.], v. 6, p. 64-70, 2015. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://www.scirp. org/journal/PaperInformation.aspx?PaperID=53210 . Acesso em:11 out. 2015. [ Links ]

STOLTZ, Tania; VEIGA, Marcelo; ROMANELLI, Roseli A. Apresentação. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, v. 31, n. 56, p. 15-18, 2015. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.41831. Acesso em: 23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

STOLTZ, Tania; WEGER, Ulrich. O pensar vivenciado na formação de professores. Educar em revista, Curitiba, v. 31, n. 56, p. 63-83, 2015. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.41444. Acesso em: 23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

STOLTZ, Tania; WIEHL, Angelika. Das MenschenbildalsRätselfürjeden. Anthropologische Konzeptionen von Jean Piaget und Rudolf Steiner im Vergleich. Pädagogische Rundschau, [S. l.], v. 73, n. 3, p. 253-264, 2019a. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.3726/PR032019.0024. Acesso em 23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

STOLTZ, Tania; WIEHL, Angelika. Rudolf Steiners Erkenntnis theorie als Grundlage der Waldorfpädagogik. In: WIEHL, A. (org.). Studienbuch Waldorf-Schulpädagogik. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt/utb, 2019b. v. 1, p. 103-118. [ Links ]

VEIGA, Marcelo. Cada homem é um problema! Considerações sobre a compreensão do outro com base no enfoque científico de Goethe. In: GUÉRIOS, Ettiène; STOLTZ, Tania (org.). Educação e Alteridade. São Carlos: Edufscar, 2010. [ Links ]

VEIGA, Marcelo. How Much “Spirit” Should Higher Education Afford?Other Education: The Journal of Educational Alternatives, Kenilworth, v. 1, n. 1, p. 166-170, 2012. Disponível em:Disponível em:https://www.othereducation.org/index.php/OE/article/view/daVeiga_1_1_166170_2012 . Acesso em:23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

VEIGA, Marcelo. O significado do pensamento filosófico para a Pedagogia Waldorf. In: VEIGA, Marcelo; STOLTZ, Tania. O pensamento de Rudolf Steiner no debate científico. Campinas: Alínea, 2014. p. 9-32. [ Links ]

VEIGA, Marcelo. Revisiting humanism as guiding principle for education: anexcursionintoWaldorf Pedagogy. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. 56, p. 19-31, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://ojs.c3sl.ufpr.br/ojs/index.php/educar/article/view/41417 . Acesso em:11 out. 2015. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. “Concrete Human Psychology”. Soviet Psychology, [S. l.], v. 27, n. 2, p. 53-77, 1989. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-0405270253. Acesso em: 23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. Obras escogidas. Madrid: Visor, 1991. v. 1. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. “The History of the Development of Higher Mental Functions”. New York: Plenun Press, 1997. (The Collected Works, v. 4) [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. As emoções e seu desenvolvimento na infância. In: VYGOTSKY, Lev S. O desenvolvimento psicológico na infância. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1998. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. A educação estética. In: VYGOTSKY, Lev S. Psicologia pedagógica. São Paulo: Martins Fontes , 2001. p. 323-363. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. Teoria de las emociones: Estudio histórico-psicológico. Madrid: Ediciones Akal, 2004. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. A Formação Social da Mente. São Paulo: Martins Fontes , 2007. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. Imaginação e criação na infância: ensaio psicológico: livro para professores. São Paulo: Ática, 2009a. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. Imaginação e arte na infância. Lisboa: Relógio d’Água Editores, 2009b. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. La conciencia como problema de la psicologia del comportamiento. In: VYGOTSKY, Lev S. Obras escogidas, tomo I: El significado histórico de lacrisis de la Psicología. Madrid: Machado Grupo de Distribución, 2013. p. 39-59. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. Imaginação e criatividade na infância. São Paulo: Martins Fontes , 2014a. [ Links ]

VYGOTSKY, Lev S. Obras Escogidas - II: Pensamiento y Lenguaje - Conferencias sobre Psicología. Madrid: Machado Libros, 2014b. [ Links ]

1Research financed by the scholarship granted by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). Case number: 88881.134528 / 2016-01. Research financed by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Productivity Grant -, n. 311402 / 2015-1 and 307143 /2018-0. Translated by David Harrad. E-mail: davidharrad@hotmail.com

3Among the several different ways in which the name Vygotsky is written, we will use the form most commonly found in the English language, Vygotsky.

4Higher psychological processes refer to the fundamental psychological functioning of human beings, such as consciously controlled actions, active memorization, voluntary attention, intentional behavior, and abstract thought. Higher psychological processes are different from more elementary mechanisms such as automatic reactions, reflexes, and simple associations. This differentiation between higher psychological processes and elementary mechanisms is fundamental to the understanding of human development and a privileged focus in Vygotskyan theory.

5The convergences presented here are centered on essential aspects of Vygotsky's and Steiner's theories, not discarding the possibility of other aspects not mentioned.

Received: June 17, 2021; Accepted: August 29, 2021

texto em

texto em