Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Educar em Revista

Print version ISSN 0104-4060On-line version ISSN 1984-0411

Educ. Rev. vol.37 Curitiba 2021 Epub Nov 07, 2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.78130

DOSSIER - Challenges for evaluation in and of Early Childhood Education

(Re)creating spaces and sharing knowledge: Evidential Evaluation as a central axis of pedagogical work of Physical Education in Early Childhood Education1

( Universidade Federal do Tocantins; Miracema do Tocantins, Tocantins, Brasil. E-mail: marcielbarcelos@gmail.com

(( Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo; Vitória, Espírito Santo, Brasil. E-mail: wagnercefd@gmail.com

The article analyzes evidential evaluation in Physical Education classes in Early Childhood Education, focusing on the production of assessment practices and their experiences. It takes the perspective of an existential Research-action method, carried out with a teacher trained in Physical Education and 17 children from a Municipal Unit of Early Childhood Education in Vila Velha, Espírito Santo (ES), Brazil. The data showed the potential of the evidential evaluation in that context, articulating the assessment practices and the children's narratives to give visibility to the memory of the formative path.

Keywords: Assessment; Physical Education; Early Childhood education

O artigo analisa o uso da avaliação indiciária realizada nas aulas de Educação Física na Educação Infantil, focando a produção de práticas avaliativas e as experiências construídas por meio delas. Assume perspectiva da pesquisa-ação existencial realizada com um professor formado em Educação Física e 17 crianças de uma Unidade Municipal de Educação Infantil de Vila Velha/ES. Os dados evidenciaram as potencialidades da avaliação indiciária naquele contexto, articulando as práticas avaliativas e as narrativas infantis com o intuito de dar visibilidade à memória do percurso formativo.

Palavras-chave: Avaliação; Educação Física; Educação Infantil

Introduction

The purpose of this article is to analyze the use of evidential evaluation2 (SANTOS, 2005; VIEIRA, 2018) carried out in Physical Education classes in Early Childhood Education, focusing on how the learning was constructed by the teacher and the children, highlighting the meanings attributed to the path formative.

From a conceptual point of view, evidence evaluation is a political act that presents itself as part of the knowledge weaving process. It bases on prospection and heterogeneity without previously defined closed models, with is no concern to label or classify, but rather to identify the "known," the "unknown," and the "not-yet-known" in development. Therefore, the evaluator's task is permanent in interpreting signs, evidence from which judgments and decision-making manifest. By investigating, the teacher refines their senses and exercises/develops different knowledge to act according to the needs of those involved, individually and collectively (SANTOS, 2005, 2008; VIEIRA, 2018).

Thus, understanding the evidence produced in/by the teaching-learning process is essential to yielding an evaluative practice beyond error and success, considering the children's repertoires as clues and signs of their learning. The evidential evaluation (SANTOS, 2005), in this case, acts in the action-reflection-action of the pedagogical processes, enabling conscious judgment about what is done, what is learned, and what is done with what is learned, enhancing analysis of formative processes.

This investigation and search for evidence of learning through evaluation practices intertwine those who evaluate and those assessed in a dialogical relationship, simultaneously constituting and being constituted. The challenge posed to children to construct meaning and knowledge anchored in their daily lives marks the mediation between what is taught and what is learned. With this, they shift from a consumer of content to producers of knowledge, protagonists of their formative paths, and simultaneously share assessment practices with the teacher. Furthermore, this article provides continuity for a 15-year collective effort to enhance the studies on evidential evaluation through research that takes everyday school life as the locus of its production (SANTOS, 2005; SANTOS et al., 2014, 2016, 2019a; 2019b; VIEIRA, 2018; VIEIRA, 2018; LANO, 2019; VIEIRA; FERREIRA NETO; SANTOS, 2020). The concern is to go beyond the types of research characterized as problem diagnostic, providing concrete possibilities for evaluation in primary education.

The need to develop the theoery of evidence evaluation and the gap in research on the evaluation practices of Physical Education teachers in Early Childhood Education justify this study as evidenced by Alves (2011), López-Pastor et al. (2013), Glap, Brandelisse, and Rosso (2014), Santos et al. (2018) and Vieira (2018), when mapping production in journals, theses, and dissertations. Vieira, Ferreira Neto, and Santos (2020)highlight that, although scholars have dedicated studies on assessment for learning to analyze daily school life in the past 20 years, there is still a lack of investigations that provide teachers with different ways to produce assessment practices in child education.

Intending to contribute to this debate and expand studies on the evaluation of Physical Education in Early Childhood Education, we proposed using (CERTEAU, 1994) evidential evaluation. For this, the following questions guided us: is it possible to produce evaluative practices that show the meanings attributed by children to their learning? Is it possible to accept narratives as a possibility of an evaluative tool in childhood education? How to understand children's learning from the imagery records produced in everyday school life?

Methodology

The methodological production of this article is within the complexity of everyday school life (ALVES, 2003), especially in Early Childhood Education, which assumes a logic of schooling that differs from the subsequent stages, constituting formative spaces that dialogue with the children's integral education (BARROS, 2009; MOTTA, 2013; DIAS, CAMPOS, 2015). In this sense, going to the field was not regarded as a self-contained action of data collection. Instead, it's considered an (inter)action of production, in which children and teachers (re)create and attribute context meaning at every moment.

Thus, the scientific method used to produce an evidential evaluation (SANTOS, 2005, 2008; VIEIRA, 2018) in Early Childhood Education permeated the collaborative action between practitioners involved in this research. Imbued with this intention, we assume existential Research-action (BARBIER, 2002) as a scientific method.

Barbier (2002) highlights that the method allows: a) to detach from methodological instruments that frame the researched reality; b) propose a reflection-action that enables a transformation of the daily life, and c) promote a reflection on the activity produced and how it can be (re)created.

Thus, existential Research-action "[...] resides in a change in the subject's attitude (individual or group) to the reality that ultimately imposes itself (reality principle)" (BARBIER, 2002, p. 71, our translation). From this perspective, we approach the school context to understand the rationales existing in that place. Based on the productive consumption of practices, we stress the schooling process based on the evidential evaluation.

We conducted the study at the Municipal Primary Education Unit, located in Vila Velha, Espírito Santo (ES), from February 3 to December 21, 2017, every Tuesday and Friday during that school year, from 7 am to 11 am. Group 4 comprised seventeen children (eleven boys and six girls aged four to four years, 11 months, and 29 days).3

At first, we identified both the specificity of the assessment carried out by the institution's educators and the reasons that lead them to assess in Early Childhood Education, as well as the characteristics of the teaching work:

fragmented conception of the curriculum by teachers trained in Pedagogy and Physical Education and its mobilization in daily school life.

disarticulation of individual projects from the institutional project.

understanding of evaluation anchored in the quantitative paradigm.

predominance of "observation" as an evaluative practice, focusing on behavior at the expense of learning.

learning rights worked on an itinerant basis.

Teacher Lucas4, who received his degree in Physical Education from Faculdades Integradas Espírito-santense (Faesa) in 2013, collaborated with our study. As we experienced the daily routine of the teacher's interventions, we began to analyze the clues (GINZBURG, 1989) left behind. For Lucas, Physical Education in early childhood enhances motor development, a concept associated with his formative trajectory as a gymnastics coach.

On August 10, 2017, we met with teacher Lucas to discuss his pedagogical project. At this meeting, we collectively decided to modify both the project and the logic of the work, approaching the perspective of evidential evaluation. Table 1 presents the modifications.

TABLE 1 - METHODOLOGICAL ORGANIZATION OF WEEK CLASSES

| HOW IT USED TO BE | ||

|---|---|---|

| Monday | Wednesday | Friday |

| Motor-skill circuit/experience activities | Motor-skill circuit/experience activities | Free class or toy day |

| AFTER MODIFICATIONS | ||

| Physical activities consisted of games, jamborees, and adventures | Physical activities consisted of games, jamborees, and adventures | Register and explanation of learnings of the week |

SOURCE: elaborated by the authors

In line with the changes made in the project and the organization of their classes, the teacher felt the need to expand actions to fortnightly meetings to discuss the practices and content developed with the children, especially on the production of evaluation records. We realized that it would be necessary to understand existential Research-action (BARBIER, 2002) as a collaborative action, as the problem does not present itself a priori but emerges from the needs demanded by the research participants. Thus, we started to plan the workweek, the imagery records produced, and the children's narratives.

Our sources are composed of image narratives by Lucas and the children (drawings, photos, and videos). Through them, we sought the meanings attributed to learning from the perspective of what they did with what they learned (SANTOS et al., 2014, 2016, 2019a, 2019b; VIEIRA, 2018), using the children's records with oral narratives to recreate the context of learning and show its consumption and appropriations (CERTEAU, 1994). For Certeau (1994), everyday life is a place marked by the practices of those who compose it. By having contact with these practices, people appropriate them, making different consumptions that are re-signified into practices to meet their demands.

The oral narratives recorded in a field diary were produced both by the gym teacher and by the children during classes at other times in the daily life of the Early Childhood Education institution5. These narratives contributed to advancing in decision-making on how to reorient the development of the intervention project and other methodological actions in an action-reflection-action process. We also used the descriptions present in the field diary to promote another look at the analyzed action.

We discuss our data in three topics that address different assessment practices. The first focuses on the use of emojis, the second focuses on drawing, and the third emphasizes building a collaborative portfolio between the teacher and the children.

Evidential evaluation and the production of evaluation practices in Early Childhood Education: exploring modal language

As we inserted ourselves in Lucas's teaching and learning process, we began to appropriate the meanings created and recreated by the children in their interactions with peers and for Corsaro (2011), peer interactions are ways in which children share their cultural production through play. In this movement, they understand the social reality in which they are immersed. In turn, they begin to internalize and contribute to the change of cultures surrounding them, including the practitioners of daily school life, always marked by playfulness and make-believe, thus creating ways of living that unique space.

We performed a positive reading (CHARLOT, 2000) of that movement. We decided to work with modal language6 to make sense of children's expressions, feelings, desires, difficulties, and dissatisfactions in Physical Education classes. In this way, we created a space for self-evaluation based on what was very close to them, the emojis. Immersed in the evidential logic (SANTOS, 2005), the teacher built emojis with the children with ☹sad, 😊 happy, and 😐indifferent faces to share their experience impressions with the teacher and friends. It is important to highlight that the insertion of the emoji that represented “indifference” emerges from the need to analyze the “spaces-in-between” of learning, a frontier space where “knowing” and “not knowing” are found (SANTOS, 2005). This required an investigative practice from the teacher (ESTEBAN, 2001), questioning what goes on in daily life, cunningly sifting through the evidence provided by the children as they practice the school spaces, in our case, in Physical Education classes.

Employing emojis as an evidential evaluative practice placed us in a complex field. In this sense, the appropriation of technological equipment and different media into the educational context as an assessment tool of teaching and learning unavoidably construes new relationships with the world (CHARLOT, 2000), especially with the children's families.

Charlot (2000, p. 69, our translation) highlights that "[...] there is, in fact, a self [...] immersed in a given situation, a Self that is a body, perceptions, systems of acts in a correlated world of our own acts". By appropriating this self, which is involved in the relationships shared with children, we proposed to delve into the ways of living childhood.

Figure 1 below shows the construction of the emojis with the children in one of the moments they assessed their experiences in the Physical Education class.

As the children completed their emojis, they narrated their achievements, sometimes asking for an assessment from the teacher, sometimes showing their learning; Carlos is concerned with the aesthetic dimension: "Teacher, look at mine! It's beautiful, right?"; Luiza highlights the smile drawn on her emoji: "Here's mine, it's happy"; Augusto presents his way of performing the task: "I managed to do it, I did it like this"; João asks for help with the completion of his emoji: "Teacher Lucas, can you help me cut?".

The narratives show different moments in the construction process of emojis, highlighting: the aesthetic dimension and the value judgment on their production; the design and its meanings; success in the task while signaling their learning; the need for help to complete the activity based on the understanding that it is only possible to finish, at that moment, in the relationship with the other (CHARLOT, 2000).

Santos et al. (2019a) highlight that the children's intentions, when narrating their experiences, especially the evaluative ones, are not restricted to mere description. They produce effects and expand the possibilities of understanding their experiences, constituting a learning memory.

To narrate their learning means turning it into clues (GINZBURG, 1989), allowing projections that favor understanding knowledge, assembling, and (re)assembling what happened. Moreover, searching and researching the event produces practices that enhance the relationships with learning, especially those inscribed in the body.

We agree with Nunes and Corsino (2020) when they emphasize that the richness of pedagogical work in Early Childhood Education is due to the quality of interactions, which allows the production of different meanings of experiences in space. When using emojis as an evidential evaluative practice, children can qualify the exchanges and dialogues. This process promotes a conscious assessment of what they have learned.

At the same time, emojis as an evaluative strategy also served as a self-assessment process, as they enabled the children to analyze their formative path. From the conceptual typologies of the assessment point of view (CASANOVA, 1997), we observe the use of emojis as a practice that transits between kinds of agents. The first is hetero assessment (centrality on the one who proposes assessment, in this case, the teacher), and the second is self-assessment (centrality on the evaluated subject, in this case, the children).

In addition, the use of emojis to mediate children's interactions with the teacher continued into the 2017 school year, after he used a storytelling game to work parkour moves. We recorded the following narratives.

The use of emojis allowed the teacher to locate and listen to the children about their learning process, mediating the physically appropriated knowledge and carrying out a movement towards his and the children's reflection about their progress. The narrative presented in Figure 2 highlights João relating the experience to the object of teaching, parkour.

More than helping children to take the reins of their formative path, by carrying out this dialogic movement (FREIRE, 2001), the teacher operates with different practices regarding the child's previous knowledge and their ways of using it in their educational path. Through this, they resignify their actions, give meaning to the place and form they understand, and intervene in their daily lives, contributing to the formation of autonomy and reality itself.

Later, teacher Lucas highlighted that listening to the narratives allowed him to reflect on his actions and on what the children learn:

It is good that they [children] say everything. They tell me what they liked, what they wanted to do. Then I get these insights [information] from them, and I'll quickly think about the next classes, impressive! I always see something new (Teacher Lucas).

Conscious decision-making is one of the characteristics of evidential evaluation (SANTOS, 2005; VIEIRA, 2018). The clues left by the children in their formative path guide their performance qualification, understanding of the learning appropriated and (re)created by the children in their interactions.

In this dialogic movement, the children returned to the experienced moments, identifying the differences between what they were already doing (zone of actual development) and indicating the new learning through different narratives, including from the point of view of objectification-denomination (CHARLOT, 2000), translating their knowledge into utterance through gesture. In objectification-denomination, learning is appropriated in relation to the object, which is given visibility through discourse (enunciation). Charlot (2000) states that the epistemic relationship of this knowledge permeates the actions that were objectively constructed to achieve that learning or the relationship that the subject establishes with learning, through emotions and perceptions.

It is essential to clarify that we also recorded other children's movements from the use of emojis. Luiza used the 😐 and highlighted: "Today I did somersaults, it's difficult!"; Maria, who used the 😊, narrated: "I did it." At that time, only Nicole used the ☹, emphasizing what she couldn't do: "I didn't roll".

The children's narratives show the different meanings attributed to their learning through the use of emojis. This serves as an indicative practice of what they do with what the teacher offers in Physical Education classes. At the same time, the narrated constructions highlight the relationship they establish with the teaching content.

Teacher Lucas' narrative, when reflecting on this movement, reminds us that listening to children, considering their narratives as learning clues, changed their way of relating to what they produce in the daily activities of Early Childhood Education:

[...] that day, I saw that he did some things right, but I had no idea how heavy it was for them when they couldn't do it. Then, at the time, also based on what you said, listening to the children and, this is a new experience for me, I said here. The next day I kept an eye on him, I paid more attention. It helped him to learn how to roll properly, of course, well within the class limits. So, for me, only this part alone was already worth talking about and reading the texts (Teacher Lucas).

From the contact with the evidential evaluation, the teacher signals the change in their practice, transforming their way of being a teacher through new methodological and assessment tools. When listening to children in this perspective, they understand their potential to mobilize teaching objects and their meanings to their achievements.

Abraão (2003), studying the memories of teacher education, clarifies that, when narrating their story, the teacher analyzes themselves, opposes themselves, and resumes dimensions of their work, confronting themselves especially about what is new in their life. This movement allowed Lucas to reframe his practice according to the demands of everyday school life.

For Abraão (2003), teachers announce their narratives seeking to build their present and future self in the articulation of their past self. When reviewing his practices, Professor Lucas self-evaluated his actions in the past, understanding the changes in the present and signaling a new way of practicing Physical Education in Early Childhood Education, enhancing what he had already been building with children.

The work with evidential evaluation, from the perspective of what one does with what one learns (SANTOS, 2005; VIEIRA, 2018), evidences the child to produce their value judgment about what they have learned, allowing them and the teacher to identify their advances and consciously make adjustments in the formative paths. The use of emojis enabled this movement as a diagnostic evaluative practice, which opened a communication channel between teacher and children, enhancing the production of narratives about learning.

At the same time, this double movement (hetero-assessment and self-assessment) favors, in its dialogic process, the formation of children towards self-regulation of their learning. We support the investigation of teaching strategies to broaden the understanding of what happens in everyday school life. Such reflection on the teaching-learning processes enhances, for example, the recognition of emojis as a pedagogical and evaluative action. In this way, considering the child as a producer of culture and knowledge, the protagonist of their formation, allows teachers to investigate (ESTEBAN, 2001), expanding their interpretive base and looking for clues and signs.

Drawing as an evaluative practice of Physical Education in Early Childhood Education

In developing the theorization of evidential evaluation, we noticed a concern in presenting concrete evaluative practices produced in everyday school life. Among them, we highlight the use of drawing (2016, 2014 ,2019a, 2019b; LANO, 2019; VIEIRA, 2018; VIEIRA; FERREIRA NETO; SANTOS, 2020). The use of drawing by the indicative evaluation signals a way for children to represent their bodily experiences through another language (VIEIRA; FERREIRA NETO; SANTOS, 2020).

But how will this movement be in Early Childhood Education? By sharing time and spaces of Early Childhood Education with teacher Lucas, we proposed rescheduling the classes (Table 1) and destined Fridays to produce records on the week's experiences.

In addition, acknowledging drawing as an evidential evaluative practice provides another form of analysis relating to the children's experiences (JOSSO, 2002). Moreover, the specificity of childhood and how they interact and appropriate the teaching objects and their meanings inevitably cross the experiences.

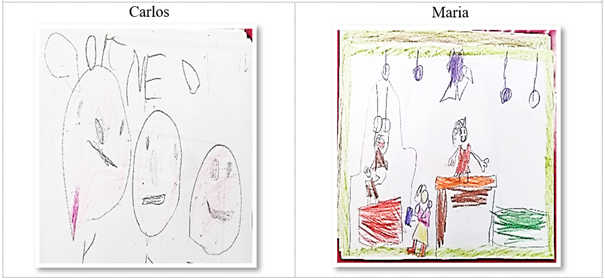

The first imagery narratives showed little evidence of what was going on in the daily complexity of Physical Education classes; however, as the work evolved, the records presented other systematizations that gave clues to the appropriations. Figure 3 shows two drawings produced by the children, which provide clues as to how this evaluation practice was advanced and gained meaning as the children appropriated and transformed the experiences.

The drawings presented were produced in different weeks: Carlos's, in the week of the presentation of emojis, and Maria's, recalling a visit to the gym court of a private university located in the same city. The children made them as the final parkour assignment.

In the indicative evaluation, the teacher takes an investigative perspective, analyzing what is and is not said about the children's productions. In this case, the drawings possibly delivered information to explore the gaps about the meaning production of the experiences.

The relationship established by children with emojis was the subject of the first drawings. The authors' narrative gives evidence of what marked their experience with the production of emojis: "I did it, I liked it because I cut it" (Carlos).

By building his emoji, Carlos gave visibility to his protagonism, highlighting the challenge he took on, which became a learning experience, marking that specific moment and creating a memory of his formative trajectory. This movement also indicates the very uniqueness of the path, providing subsidies for understanding the importance of the procedure in Early Childhood Education.

Oliveira-Formosinho (2007) highlights that, in pedagogical work, one often neglects the perception of children as culture producers, impacting the way they understand the teaching and learning processes and their participation in them.

In this way, Maria's imagery narrative reveals the meanings she attributes to the learnings during her visit to a private university7. In the field diary, we recorded her dialogue with the teacher:

Lucas: What did you do here? [points to drawing].

Maria: The visit to the gym.

Lucas: This is what? [points to rings].

Maria: It's where you hang and do it like this [makes a gesture similar to a twirl with her hand].

Lucas: Did you do it?

Mary: Yes.

Lucas: Did you like it?

Maria: A lot.

Lucas: And this, what is it? [points to the green part].

Maria: This is where we make a flip. I made a flip! Did you see it?

The narrative reveals not only the record of learning through drawings. By analyzing Maria's picture and considering the investigative path of the teacher, Maria highlights her learnings and what she did with them, including making hand gestures in the representation, creating an embodied appropriation that materialized in an utterance.

Reading the clues and traces in the evidence assessment allows the teacher to understand what the children have learned and what is under construction in the formative path. This process supports the classes' ways of production to enhance children's educational path from the specificity of Physical Education.

It is crucial to emphasize that we are not defending a specific sport modality for young children. We are otherwise signaling how they appropriate experiences and create memories of learning, evidenced by evaluation practices favoring the production of narratives. The teacher himself recognized this movement:

"[...] that day, the assistants were doing flips with the children, but now I realized that they went there and something from process stuck with them. If it hadn't, they wouldn't even be repeating the word 'flip.' They would have used another reference" (Teacher Lucas).

Esteban (2001) emphasizes that evaluation is a constant action of investigating oneself. Thus, when questioning himself, teacher Lucas reflects on the clues he created, aiming at the production of meanings through the analysis of the drawings by their authors, the children, recognizing the learning process, and acquiring subsidies to enhance his planning.

It is essential to consider what Coêlho and Souza (2020) reiterate about narratives in Early Childhood Education. The authors argue that narratives are relevant in the formative path since it is possible to reinvent oneself and assign meaning to shared experiences in educational contexts.

An investigative practice (ESTEBAN, 2001) from the evidentiary logic (SANTOS, 2005; VIEIRA, 2018) allows the rescue of memories through drawings and narratives revealing the individual formative path and providing subsidies for constant change. In this direction, documentary production in Early Childhood Education must be open and consider the complexity of the network of meanings that children produce in their narratives.

The portfolio as an evaluative practice

Villas Boas (2010) highlights that, in the portfolio production, a careful selection of the materials that make up the document is necessary to recognize the trajectory of the work produced by the teacher and the children and, consequently, their evaluation.

The portfolio's organization consisted of recording the activities developed during the training actions, allowing for an assessment of the entire process at the end. In this case, considering the purposes of the evaluation (CASTILLO ARREDONDO; CABRERIZO, 2012), the portfolio gained formative and summative contours.

In this way, the inventive character of the evidential evaluation allowed us to signify the portfolio so that it could be "read" by all those who participate in the daily school of Early Childhood Education. It became an assessment tool of the whole learning carried out in the educational process. Thus, we inventoried (SANTOS, 2005; SANTOS et al., 2014, 2016, 2019a, 2019b; VIEIRA, 2018) different ways of producing the portfolio, assuming it as a formative assessment tool in the construction process, and summative in the registration and communication of the learning for practitioners of daily school life.

The portfolio8 consisted of recording formative memories collaboratively between the teacher and the children in a self-evaluative movement that allowed for reflection-investigation. The following narratives highlight how the self-assessment process went through the assembling of the portfolio.

Thus, the document built collaboratively between the teacher and the children had the following logic: introduction9, lesson plan10, imagery records11, and text connecting the actions12.

Carlos: Teacher, that day was good [points to the class where the children drew emojis on the board].

Lucas: Yeah, I liked it too. What did you learn that day?

Carlos: I learned how to make emojis and learned how to talk using emojis.

Children: Me too [other children shouted together].

Carlos: I learned how to draw emojis. I didn't know how to draw emojis before.

Lucas: Come on, but did you only learn emojis?

Children: No! [impossible to identify the voices].

Carlos: I liked "Simon says" and the gym room.

Lucas: What did you learn in the gym and playing "Simon says"?

Carlos: I learned how to do the somersaults.

Luiza: Me too, and also the hanging one (rings).

Augusto: I followed Simon. He did it like this [uses the pen to indicate a jump].

The memory of the formative path indicated the learning that took place in that school year, enabling children to self-evaluate their process and highlight their achievements. The portfolio as a methodological decision allowed recording the actions and gave visibility to the children's protagonism and the productive consumptions carried out during the Physical Education classes.

The complexity of narratives paved the way to the moments of reflection-investigation. These, in turn, indicated the learning of popular games (Simon says), drawings ("I learned to draw emojis"), specific movements (somersault, jumping, and rings), and a different way of communicating narratives through emojis.

Santos et al. (2019a, p. 7, our translation) emphasize that it is crucial to assume the narratives as evaluative sources "[...] especially due to the students' training capacity in the projection of practices and in the re-reading of their learning". This way of announcing what happened contributed to the understanding of the complexity of children's learning.

Through the self-assessment process, other actions emerged, such as the production of the portfolio cover, in which the children replaced their faces with emojis. Each child chose the face that best represented them throughout the school year.

The teacher's narrative about the inventive process of the portfolio signaled the challenges faced:

How to make a portfolio that both children and guardians can understand? I'm explaining to the children, but what about them (family members)? It's very different from what they've seen here at Umei! I have to think about how to do this (Teacher Lucas).

At that moment, based on the evidential evaluation and the individual project, we registered a way to communicate the lesson plans.

To this end, we built "subtitles" so that children could identify the symbols and present them to their families. In this way, they could explain how the class was and what they learned, connecting the lesson plans, photos, and drawings.

This movement allowed family members to understand the intentions of the formative project based on the narratives of their sons and daughters. Hence, the children were protagonists both in the portfolio production and exhibition, transforming the memories of their learning into statements.

It is also essential to highlight the pictures that the children selected to make up the portfolio. Next, we present seven photos chosen by the children in a dialogic and reflective action to compose the portfolio.

Santos (2005) emphasizes that evidential evaluation is a shared and participatory action, placing children as protagonists in their learning. Thus, when mediating the relationship established by the children with the knowledge produced, the teacher seeks to problematize the challenges faced in the educational process.

The selection of photos represented the challenging evolution of that school year and revealed how the children recognized their process of memory production of the formative path.

The selected pictures indicate that embodied practices are a specificity of Physical Education, reinforcing the need to reflect on such practices in Early Childhood Education.

It is in intertwining these different ways of knowing that the child evidences their learning and builds memories of their formative path process. Our work brought forth the singularities of learning in Physical Education, which uses different languages to enhance the formative process. Therefore, there is a stark need for an evaluative framework that permits looking beyond what children do with their learning.

Final remarks

This article aimed to present possibilities of practices based on the concept of evidential evaluation in the daily life of a preschool class at Umei, based on the actions and processes the Physical Education teacher and the children built together.

Aligned with the theoretical foundation, we demonstrated how the evidential evaluation, assumed as a perspective of pedagogical work, allowed the production of actions that became evaluative practices and the reflection about the involved actors' own interventions. Moreover, regarding the children as protagonists gives new meaning to understanding assessment processes as a whole.

Along these lines, we produced evaluation practices taking playfulness as a background: emojis and drawings. Both tools articulated to the children's narratives, fostering a movement of investigation of learning and production of the memory of the formative path.

This memory, associated with the inventive character of the evidential evaluation, enabled the teacher and the children to produce a portfolio, enhancing their role in the learning process and the possibility of sharing it with their families.

In this way, we signal the potential of using evidential evaluation in Early Childhood Education, expanding the meanings produced by children in their formative experiences, allowing them to identify and evidence what they do with what they learn (SANTOS, 2005; VIEIRA, 2018).

As a perspective for future research with the evidential evaluation in Early Childhood Education, we indicate its experimentation in the daycare centers, especially with children who narrate their formative experiences through other language modes.

REFERENCES

ABRAHÃO, Maria Helena Menna Barreto. Memória, narrativas e pesquisa autobiográfica.Histórias da educação, Pelotas, n. 14, p. 79-95, set. 2003. [ Links ]

ALVES, Nilda. Cultura e cotidiano escolar. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, n. 23, p. 63-74, maio/ago. 2003. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782003000200005. Acesso em: 17 out. 2021. [ Links ]

ALVES, Fábio Tomaz. O processo de avaliação das crianças no contexto da educação infantil. 2011. 348 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) ─ Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2011. [ Links ]

BARBIER, René. A pesquisa-ação. Brasília: Plano, 2002. [ Links ]

BARROS, Flávia Cristina Oliveira Murbach de. Cadê o brincar?: da educação infantil para o ensino fundamental. São Paulo: Editora Unesp, 2009. [ Links ]

CASTILLO ARREDONDO, Santiago; CABRERIZO, Jesús Diago. Evaluación educativa de aprendizajes y competencias. Madrid: Editorial Pearson, 2012. [ Links ]

CASANOVA, María Antonia. Manual de la evaluación educativa. Madrid: Editorial la Muralla, 1997. [ Links ]

CERTEAU, Michel. A invenção do cotidiano: artes de fazer. 8. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1994. [ Links ]

CHARLOT, Bernard. Da relação com o saber: elementos para uma teoria. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 2000. [ Links ]

COÊLHO, Patrícia Souza Julia; SOUZA, Elizeu Clementino. Narrativas e aprendizagens experienciais de crianças de uma escola de educação infantil rural. Revista @mbienteeducação, São Paulo, v. 12, n. 2, p. 222-240, maio/ago. 2019. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.26843/ae19828632v12n22019p222a240. Acesso em: 16 out. 2021. [ Links ]

CORSARO, William. Sociologia da infância. 2. ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2011. [ Links ]

DIAS, Edilamar Borges; CAMPOS, Rosânia. Sob o olhar das crianças: o processo de transição escolar da educação infantil para o ensino fundamental na contemporaneidade. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagogicos, Brasília, v. 96, n. 244, p. 635-649, 2015. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.1590/S2176-6681/346813580. Acesso em:16 out. 2021. [ Links ]

ESTEBAN, Maria Teresa. O que sabe quem erra?: reflexões sobre a avaliação e fracasso escolar. Rio de Janeiro: DP&A, 2001. [ Links ]

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da autonomia. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2001. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, Carlo. Mitos, emblemas, sinais: morfologia e história. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1989. [ Links ]

GLAP, Graciele; BRANDELISE, Mary Ângela Teixeira; ROSSO, Ademir José. Análise da produção acadêmica sobre a avaliação na/da educação infantil do período 2000-2012. Praxis Educativa, Ponta Grossa, v. 9, n. 1. p. 43-67, jan./jun. 2014. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.5212/PraxEduc.v.9i1.0003. Acesso em: 17 out. 2021. [ Links ]

JOSSO, Marie-Christine. Experiências de vida e formação. São Paulo: Cortez, 2002. [ Links ]

LANO, Marciel Barcelos. Usos da avaliação indiciária na educação física com a educação infantil. 2019. 148 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação Física) - Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, 2019. [ Links ]

LÓPEZ-PASTOR, Victor Manuel et al. Alternative assessment in physical education: a review of international literature. Sport, Education and Society, [S. l.], v. 18, n. 1, p. 57-76, 2013. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2012.713860. Acesso em:17 out. 2021. [ Links ]

MOTTA, Flavia Miller Naethe. De crianças a alunos: a transição da educação infantil para o ensino fundamental. São Paulo: Cortez, 2013. [ Links ]

NUNES, Maria Fernanda Rezende; CORSINO, Patrícia. Leitura e escrita na educação infantil: contextos e práticas em diálogo. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 49, n. 134, p. 100-126, out/dez. 2019. Disponível em:Disponível em:http://publicacoes.fcc.org.br/index.php/cp/article/view/6109 . Acesso em:16 out. 2021. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA-FORMOSINHO, Julia. Pedagogia(s) da infância: reconstruindo uma praxis da participação. In: OLIVEIRA-FORMOSINHO, Julia; KISHIMOTO, Tizuko Morchida; PINAZZA, Monica Appezzato (org.). Pedagogia(s) da infância: dialogando com o passado construindo o futuro. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2007. p. 13-36. [ Links ]

PAIVA, Vera Lúcia Menezes de Oliveira. A linguagem dos emojis. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, Campinas, v. 55, n. 2, p. 379-399, maio/ago. 2016. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Wagner. Currículo e avaliação na educação física: do mergulho à intervenção. Vitória: Proteoria, 2005. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Wagner dos. Currículo e avaliação na educação física: práticas e saberes. In: SCHNEIDER, Omar et al. (org.). Educação física, esporte e sociedade: temas emergentes. Aracajú: Editora da UFS, 2008. v. 2, p. 87-106. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Wagner et al. Avaliação na educação física escolar: construindo possibilidades para a atuação profissional. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 30, n. 4, p. 153-179, out./dez. 2014. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-46982014000400008. Acesso em: 17 out. 2021. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Wagner et al. Evaluation of school physical education: recognizing it as a specific curriculum component.Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 21, n. 1, p. 205-217, 2015. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Wagner et al. A relação dos alunos com os saberes nas aulas de educação física. Journal of Physical Education, Maringá, v. 27, p. 27-37, 2016. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.4025/jphyseduc.v27i1.2737. Acesso em: 17 out. 2021. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Wagner et al. Avaliação em educação física escolar: trajetória da produção acadêmica em periódicos (1932-2014). Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 24, n. 1, p. 9-22, jan./mar. 2018. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.63067. Acesso em:17 out. 2021. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Wagner et al. Avaliação na educação física escolar: analisando as experiências das crianças em três anos de escolarização. Movimento, Porto Alegre, v. 25, p. 1-17, 2019a. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.76974. Acesso em:16 out. 2021. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Wagner et al. Formação de professores em educação física e avaliação: saberes teóricos/práticos. Revista Contemporânea de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 14, p. 287-308, 2019b. Disponível em:https://doi.org/10.20500/rce.v14i29.19243. Acesso em: 16 out. 2021. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, Aline Oliveira. Por uma teorização da avaliação em educação física: práticas de leituras por narrativas imagéticas. 2018. 366 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação Física) -Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação Física, Centro de Educação Física e Desportos, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, 2018. [ Links ]

VIEIRA, Aline Oliveira; FERREIRA, Amarílio NETO; SANTOS, Wagner. Práticas avaliativas indiciárias e os sentidos atribuídos ao aprender na educação física em nove anos de escolarização. Revista Humanidades & Inovação, Palmas, v. 7, n. 10, p. 200-217, abr. 2020. Disponível em:https://revista.unitins.br/index.php/humanidadeseinovacao/article/view/2877. Acesso em: 17 out. 2021. [ Links ]

VILLAS BOAS, Benigna Maria de Freitas. Portfólio, avaliação e trabalho pedagógico. Campinas: Papirus, 2010. [ Links ]

2Santos (2015) employs the term “Evaluation as an Indexical Practice” to which we agree. Nevertheless, for text fluidity in English, the translator chose “Evidential Evaluation” (VIEIRA, 2018).

4Taking into account the ethical precepts, we chose to use fictitious names for the teacher and the children who participated in this research.

5The oral narratives were produced during classes, at mealtime, in chats in the school corridors and in weekly and biweekly planning.

6Modal language is a form of expression used by people in a given period. It is multifactorial and has no historical basis, as it is developed in everyday life and is based on the actions of the people who make up this space, through the use of what is “en vogue” (PAIVA, 2016).

7After the end of activities with parkour, Lucas started the work with gymnastics movements (rolling, handstand with three supports and cartwheels). This action aimed at the progression of previous parkour practices. This started on October 30th and ended on December 1st, 2017.

8The portfolio produced by Lucas and the children was exhibited on the last day of school in the 2017 school year (December 15, 2017).

9An informative text for family members, explaining the portfolio’s rationale in relation to its organization.

11After the lesson plans, the children selected and presented photos and drawings as “highlights”, The remaining work was filed on the back as the portfolio’s “cover”.

Received: December 01, 2020; Accepted: June 01, 2021

text in

text in