Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Educar em Revista

versão impressa ISSN 0104-4060versão On-line ISSN 1984-0411

Educ. Rev. vol.39 Curitiba 2023 Epub 14-Nov-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-0411.87509

Dossier - Education, Health and Childcare: knowledge, expertise and social practices

Isolated childhood: public policie for leprophylaxis in Maranhão (1930-1950)1

*Universidade Federal do Maranhão, UFMA, São Luiz, Maranhão, Brasil. E-mail: rosyane-dutra@ufma.br

**Universidade Federal de São Paulo, UNIFESP, São Paulo, São Paulo, Brasil. E-mail: celia.giglio@unifesp.br

The article aims to disseminate partial results of research carried out within the scope of the doctoral course in education, on public policies for children in Maranhão, with a focus on the period of the Estado Novo, where the concern with the epidemics that spread throughout the state triggered prophylactic practices to control of individuals sick with leprosy. In the case of the children, they were isolated in a preventorium, called Educandário Santo Antonio, after their parents were diagnosed with the disease and institutionalized in Colônia do Bonfim, a leper colony located in a region far from the city of São Luís. Based on the analysis of literature such as reports, state decrees, and bibliography produced by intellectuals about the period of government of Paulo Martins de Souza Ramos in Maranhão, we evidence political practices of subordination of children to the wishes of a society that wanted to get rid of the nuisance that they generated, despite being healthy children. Interlocutions with Erving Goffman’s theory (2008) elucidated the institutionalization of childhood as a strategy for control, surveillance, and stigmatization of individuals marked by suffering from the disease under the discourse of a policy for prophylaxis. The research results show the construction of a policy of segregation aimed at the underprivileged population in Maranhão, focusing on children, healthy children of leprosy patients, who were subjected to work, and a hygienist and moralizing education that left marks on this generation.

Keywords: Public Policies; Childhood; Leprosy; Maranhão

O artigo objetiva divulgar resultados parciais de investigação desenvolvida no âmbito do curso do doutorado em educação, sobre políticas públicas para a infância no Maranhão, com recorte no período do Estado Novo onde a preocupação com as epidemias que se alastravam pelo estado desencadeou práticas profiláticas para controle dos indivíduos enfermos pela Lepra. No caso das crianças, foram isoladas em preventório, denominado Educandário Santo Antonio, após os pais serem diagnosticados com a doença e institucionalizados na Colônia do Bonfim, leprosário localizado em região distante da cidade de São Luís. Com base na análise de literatura como os relatórios, decretos estaduais e bibliografia produzida por intelectuais sobre o período do governo de Paulo Martins de Souza Ramos no Maranhão, evidenciamos práticas políticas de subordinação das crianças aos anseios de uma sociedade que queria se ver livre do incômodo que elas geravam, apesar de serem filhos sadios. As interlocuções com a teoria de Erving Goffman (2008) elucidaram a institucionalização da infância como estratégia de controle, vigilância e estigmatização dos indivíduos marcados pelo sofrimento da doença sob o discurso de uma política para a profilaxia. Os resultados da pesquisa permitem constatar a construção de uma política de segregação voltada à população desvalida no Maranhão, com foco nas crianças, filhos sadios dos enfermos de Lepra, as qual foram submetidas ao trabalho e a uma educação higienista e moralizante que deixou marcas nessa geração.

Palavras-chave: Políticas Públicas; Infância; Lepra; Maranhão

Introduction

Public policies in Brazil, during the Estado Novo, were focused on population control and the creation of institutions for the surveillance of individuals. Concerning public health, departmentalization rationalized services for the population, especially those affected by the epidemics that were spreading across the country and which required more effective government action. In the case of Maranhão, between 1930 and 1950, specifically, in the Paulo Martins de Souza Ramos’s government, governor, and federal intervenor, there was the effectiveness of the General Directorate of Health and Assistance, which included the Technical and Administrative Section, responsible for coordination and execution of policies for the prophylaxis of epidemic diseases in the state

The leprosy epidemic in Brazil advanced in the first decades of the Republic and required that at that time, some decisions were taken by the federal government to control the disease. The establishment of an Inspectorate for the Prophylaxis of Leprosy and Venereal Diseases had repercussions on the actions that should be carried out in the Brazilian states, such as the construction of leprosariums and preventers for the isolation of the sick and their healthy children. This policy of restricting individuals with positive diagnoses subjected children to social exclusion and the disciplining of their conduct (PINTO NETO et al., 2000)2.

In this sense, this article intends to present data on the performance of the prophylactic policy against leprosy in Maranhão, highlighting the isolation of children in Educandário Santo Antonio, a preventive center located in São Luís that kept the healthy children of parents diagnosed with the disease isolated of family members and society. From the documental analysis of the reports of the governor/federal interventor Paulo Ramos, state decrees, and texts published by intellectuals of medicine from Maranhão about the period in Maranhão, we identified the discourses and practices for prophylaxis and isolation of individuals sick with leprosy and their healthy children, who, under the control of Ladies of Assistance, were subjected to abandonment, moralization, and erasure of their stories.

The contributions of Goffman’s studies (2008) mobilized reflections on the institutionalization and stigmatization of individuals who are interned by State coercion. The author’s analysis of the policing of conduct in total and closed institutions, and the medicalization of bodies made it possible to understand the functioning of public policies during the Getulist dictatorship period and its impact on Maranhão’s reality. The studies by Câmara (2009) brought historical contributions to the “Estado Novo” period in Maranhão.

Maranhão Novo and policies for leprosy prophylaxis

In Maranhão, the creation of the Directorate of Health and Assistance, in 1938, which brought together the General Directorate, Dr. Paulo Ramos, the Osvaldo Cruz Institute, the Health Districts and the Social Assistance, Hospital, and Emergency Services, coordinated the actions of Public Health policies. Specifically, the Social Assistance Services included the hospitals and other institutional spaces that managed the prophylaxis of epidemics and chronic diseases, such as tuberculosis, leprosy, and mental illnesses, including a hospital for “psychopaths” (MARANHÃO, 1941, p. 114).

The initiatives to combat leprosy were led by the Maranhão physician Achilles Lisboa, who held various positions in the state administration and who had adopted the speeches to inform the people of Maranhão about the disease. In his articles, published in newspapers and separate manifestos for the circulation of his ideas, he advised on the behaviors that the population should adopt to avoid contagion. His performance in the 1930s in Maranhão led to the creation of public health policies against tropical diseases, viruses, and epidemics such as Leprosy. In its manifesto “Catecismo de Defesa contra a Lepra”, published in 1936, in addition to guiding the population, Lisbon demarcated its position in favor of the elite it represented, considering people residing in the periphery and the rural area as lacking in hygiene and, therefore, vulnerable to disease transmission (CÂMARA, 2009).

Strict, immediate prohibition, by the police or by the health authority itself, of the public being admittedly contagious leprosy patients, especially prohibiting them from entering churches, public offices, trams, cafes, commercial establishments, markets, everywhere, after all, where there is an agglomeration of healthy people and edible foodstuffs are exposed, it must be severely established (LISBOA, 1936, p. 14).

In addition to this public manifestation of combating the disease, Lisbon’s speeches sounded like a treaty against poverty and helplessness, blaming him as a reason for the emergence of epidemics, due to the absence of adequate sanitary conditions to prevent the spread of the disease. Peripheral and rural ways of life and cultures are disregarded in their positions, labeled as habits linked to trickery and practices of daily idleness: “with many other evils of African immigration, such as leprosy, ‘yaws, ainhum, diamba, timbó, bilharzia, tambor, bumba-boi, Necator’ also came, which is, more than malaria, an essential factor in our tropical anemia and, therefore, in the laziness, ineptitude, and sluggishness of our workers rural” (LISBOA, 1947, p. 103).

In this way, Lisbon communed with the eugenicist project of the interventional governments that commanded Maranhão under the eyes of Getúlio Vargas, the president who determined policies and politicians in Brazil. From 1930 to 1945, the State of Maranhão was governed by politicians appointed by Vargas, who valued the political unity of the federation in terms of their management. From José Luso Torres to Clodomir Cardoso, there were 12 federal intervenors in the period, chosen by the presidency of the republic, to administer the government of Maranhão, with the administration of governor Paulo Martins de Sousa Ramos, who was an intervenor in Maranhão for 9 years (1936 -1945) and built new institutions for the administrative organization, which according to him, was found in real chaos. The government of Ramos was the longest-lasting and modified the administrative scenario of the state (CÂMARA, 2009).

Paulo Ramos and Achilles Lisboa, therefore, became allies in the configuration of health policies during the dictatorial regime of the Estado Novo, articulating science and politics for the organization of spaces for isolation and treatment of leprosy patients, a disease that ravaged the city and demanded immediate government initiatives. As early as 1933, during the government of Antonio Martins de Almeida, President Vargas was already presented with the real situation of the state concerning the epidemic in an Exhibition, a category of a report intended to render accounts of the activities that were carried out in the federative units. At the time, the only place for isolation of the sick was the Leprosário do Gavião, a village that operated in Bairro Lira until 1937, behind the central Cemetery of the city of São Luís, of the same name (CÂMARA, 2009)

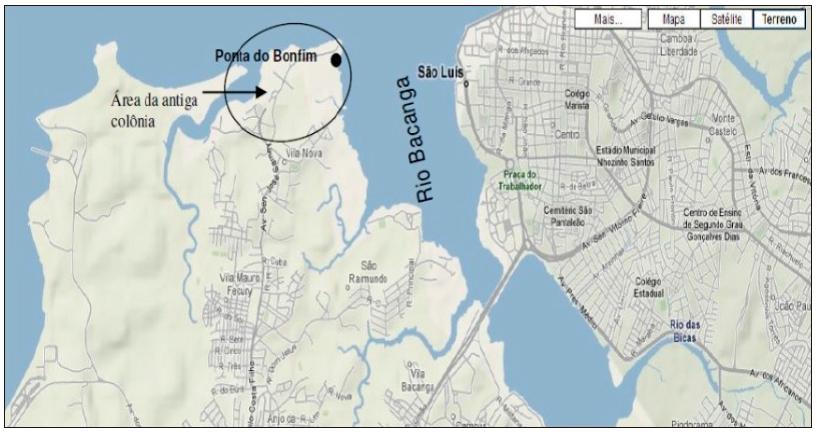

In that report, Almeida (1933, p. 54) highlighted the need to build a new, wider leper colony to accommodate the number of patients who came from the interior of the State, since the existing space no longer had sanitary conditions for functioning: “the conditions of the hovels in this human depository are on the verge of ruin, not resisting the first rains or wind that are already announced”. Ponta do Bonfim was the place chosen for the construction of the new colony, delivered in 1937. In 1935, Decree nº 799, of March 22nd, authorized the supply of materials for the construction of the Leprosarium in Ponta do Bonfim.

The Secretary General of the State is hereby authorized to sign a contract with the firm Guilherme Bluhm of this square, for the supply of necessary materials for the installations of the Leprosarium of Ponta do Bomfim, following the proposal presented by the referred firm; revoked the provisions to the contrary (MARANHÃO, 1935, p. 12).

Ponta of Bonfim (Figure 1), chosen due to its distance from the capital, had a privileged location on the other side of the bank of the Bacanga River, which runs through the central region of the island of Maranhão. That is, the sick were left there by boat and were completely isolated, which caused countless sufferings to the families of these people, in addition to the stigma that marked not only the sick but also their families. “By definition, of course, we believe that someone with a stigma is not fully human. Based on this, we make various types of discrimination, through which we effectively, and often without thinking, reduce their chances of life” (GOFFMAN, 2008, p. 15). In addition to the Colony, other policies were created to extend the service aimed at approaching the family ties of the sick: dispensaries and preventers.

The studies by Câmara (2009), which started from the analysis of the documents of the implementation of the Colony of Bonfim and interviews with former inmates, showed the inefficiency of the Brazilian isolationist system for the treatment of leprosy. In Maranhão, with scarce resources, the intention of building a leper colony outside the city was to truly remove the sick from living with others, said to be healthy. “Such barriers contribute to the maintenance of the exclusion of Bonfim egresses from social life and to the silencing of their memories, which do not appear in the history of the neighborhood formed in their surroundings” (CÂMARA, 2009, p. 36).

In São Luís, the Frei Querubim Dispensary operated where, according to Paulo Ramos, in his Exhibition to the Maranhense People (1938), “outpatient treatment of contagious people, census, surveillance and diagnosis of recent or disguised cases of leprosy” (1938, p. 17). Thus, suspected cases could be attended to diagnose the symptoms that, perhaps, were manifesting in their bodies. They were necessary spaces for population control and normalization of social life, isolating confirmed cases under medical authority. Coercion over the sick population developed a sense of fear and anguish when the diagnosis was confirmed, as they would learn of isolation and the loss of their parental ties.

The National Plan to Combat Leprosy was a government program created in 1935 that provided for the construction of leprosariums, dispensaries, and preventers, based on data from the 1933 Leprologica Census3. A Getulist plan was developed in the Ministry of Education and Health, with Capanema as minister and leader of the objectives of exterminating leprosy in Brazil (MACIEL, 2007). Built based on policies developed in other countries, the plan was organized based on Brazilian statistics on the spread of the disease in each state.

The thesis by Elaine Cristina Rossi Pavani (2019), who studied the exclusion and socio-spatial interactions of graduates of a school in the city of Vitória (ES), analyzes the creation of these spaces for the isolation and education of children born to leprous parents. The author points out that institutionalization through isolation was a proposal followed by Brazil based on the experiences of American and European countries and was defended as the main measure for those affected by the disease. “The carriers of the disease were compulsorily hospitalized in leprosariums, healthy children were hospitalized in preventers and the dispensaries performed the diagnosis of the disease and the referral to the appropriate institutions” (PAVANI, 2019, p. 121).

The dispensaries and preventers followed the guidelines signed between the federal and state agencies and monitored the rates of the disease in Brazil, through national and state conferences. The 1st National Conference on Social Assistance to Lepers, held in Rio de Janeiro between November 12 and 19, 1939, was promoted by the Federation of Societies for Assistance to Lazarus and Defense against Leprosy (FSALDL) in dialogues with all Assistance Societies to Lázaros and Defense against Leprosy present in each state, established the criteria for the functioning of these spaces. In the final document of the conference for disclosing the commitments with the assistance institutions, clauses on the families of the sick are identified:

10. - In order to provide moral and material assistance to Lázaro’s family, which contributes favorably to keeping him in isolation, all possible means must be used, mainly the following: a) - collecting and keeping minor children and health of leprosy patients; b) - supporting in a particular way the healthy wife of Lázaro, whose assistance, in certain cases, deserves special attention, being able to grant her even the financial aid that will be maintained only, until her social readjustment; c) - providing all possible support to other relatives who depend on the leper, especially the parents supported by him; d) - supporting as if relatives were any disabled person whose subsistence depended on the hospitalized Lazarus; e) providing, with special care, moral assistance to minors dependent on Lázaro and not taken to suitable establishments, at least until they reach the age of majority, directing them according to good social principles; f) - still trying to lead in life, obtaining placements, for the children and dependents of lepers, ensuring at the same time the continuity and improvement of the situation of each one; g) - do not neglect a well-oriented health education program in relation to leprosy, when providing assistance to Lázaro’s family (BRASIL, 1939, p. 432).

Surveillance of the lives of family members was one of the measures taken after the diagnosis was made in the sick individual, to combat the spread of the disease to the rest of the population. The sanitary police4 was, therefore, a necessary system for the diagnosis and coercive conduct of sick individuals to leprosariums, and their children to preventoria. Other family members received health visits and medication for preventive treatment. “1st - Sanitary Police: Visits by a doctor to vacant houses - 637; visits by guards to vacant houses - 541; visits by guards in systematic police - 19,926; subpoenas served - 267; served subpoenas - 135; dispatched projects and plans - 113” (MARANHÃO, 1941, p. 117).

In 1942, Paulo Ramos’ Report to the President of the Republic, explained the movement of the Dispensary to care for cases diagnosed in Maranhão.

the year in question, the movement at the Dispensary was as follows: Attendances for the 1st exam 28; lepromatous type 13; open cases 23; notifications received 34; contacts examined 56; appearances for review 33; attendances for treatment 237; prescribed prescriptions 130; injections are given 1,268; laboratory tests 145; home visits for treatment 124; home visits for surveillance 202; patients sent to Colonia do Bonfim 27 (MARANHÃO, 1942, p. 146).

Thus, under continuous surveillance, the population was subject to the prophylactic policies of the Paulo Ramos government, which inaugurated spaces with the discourse of prevention, but which stigmatized the sick and marked them under the pretext of epidemiological measures.

The isolation of children as prevention: the Educandário Santo Antonio

The Preventório, called Educandário Santo Antônio (Figure 2), had this name because it was attached to a Convent of the same name, in the neighborhood of Cutim Anil, in São Luís. Treated as a place of charity for confining children, daughters of the sick who were isolated in the Colony of Ponta do Bonfim, it belonged since its inauguration, on December 8, 1941, to a Society for Assistance to Lazarus and Defense against Leprosy in Brazil5.

The Preventorium for the healthy son of Lazarus, built at the expense of the Union and under the auspices of the Society for Assistance to Lazaros and Defense against Leprosy in Brazil, was inaugurated on December 8, 1941, on the occasion of the visit to this capital, from Dr. João de Barros Barreto, worthy Director General of the National Health Department (MARANHÃO, 1941, p. 121).

The Society, a female philanthropic organization for the cause of leprosy in the country, was transformed into a health and assistance policy, as it insisted on the referral that should be given to poor healthy children, daughters of the sick, as they would have to be taken to preventers under coercion. of State. This welfare institution, with the participation of elite women, led the speeches and positions on the treatment that should be carried out in the scope of preventers.

Decree-Law Nº 30, of January 25, 1938, established a new organization for the services of the Directorate of Health and Assistance of the State of Maranhão. In Title IV, on Leprosy Prophylaxis, a single chapter, article 83, mentioned aspects about children and the separation they would have to suffer from sick parents, isolated at home or in hospitals, right when they were born “and kept, until adolescence, in preventers, specially designed for this purpose” (MARANHÃO, 1938, p. 78). In the sole paragraph of art. 91, the regulation prohibited the attendance of children born to lepers in schools, without strict supervision, “and as long as they present suspicious symptoms, they can no longer remain among healthy children” (MARANHÃO, 1938, p. 78). Article 95, item 1, highlighted the work carried out by private initiatives in the organization of the preventorium, in particular, the work already carried out by the Assistance Society.

Private institutions that cooperate in the fight against leprosy will be subject to existing legal provisions and, with regard to prophylactic action, must obey the technical guidance of the Health and Assistance Board, under whose supervision they must operate, and it is their responsibility to preferably: a) care for the healthy children of leprosy patients; b) assistance to the families of hospitalized patients; c) social assistance to hospitalized patients; d) assistance to those discharged from leprosariums, home isolation, dispensaries and preventers; e) assistance to leprosy patients and their families, whenever due to the local situation, and in agreement with the health authority, hospitalization has not yet been possible; f) cooperation with the public authorities in health education, provided that the technical guidance of the health authorities is followed; g) aid or creation of study and investigation centers as well as cooperation in the treatment of patients, provided there is articulation with the official service (MARANHÃO, 1939, p. 85)

Decree-Law Nº 518, of October 23, 1941, granted Educandário Santo Antônio exemption from fees for materials purchased by the Society for the composition of the disease prevention space by confining children. These political practices demonstrated the government’s alliance with philanthropy to guarantee the functioning of the preventorium, as a necessary institution

Considering that the Society for Assistance to Lazarus and Defense against Leprosy, in this capital, its president, requires a waiver of storage, foreman, and statistics fees for 45 volumes of furniture and equipment imported for the installation of Educandário Santo Antônio - preventorium for healthy children de Lázaros (MARANHÃO, 1942, p. 94)

The Societies, constituted in several Brazilian states, and organized as a Federation in 1935, are now presided over by Eunice Weaver, married to the North American Charles Anderson Weaver, the social worker, who graduated from the University of North Carolina, started to dedicate dedicated himself to social assistance for lepers, having founded and chaired the Society for Assistance to Lazarus and Defense Against Leprosy, aligning himself with the interests of the Ministry of Education and Health, and obtaining considerable financial support (SANTOS, 2011). According to the studies by Gomide (1991), the women of philanthropy in favor of the leprosy patients made possible, through the purchasing power that their husbands held, the consolidation of a strictly feminine nationalist policy, which looked at children as a threatened future. In line with medical-hygienist discourses, the women of the Federation of Assistance Societies coined segregationist practices for children, to protect a society that banned them. In Maranhão, the director Maria Joaquina Maia de Andrade, daughter of the landowner Manoel José Maia and married to the doctor Annibal de Pádua Andrade, as director of Educandário Santo Antonio corresponded to the aspirations of the Federation of Societies for Assistance to Lazarus and Defense against Leprosy, following the rigidity imposed on the education and surveillance of children, daughters of lepers hospitalized in Colonia do Bonfim. He was at the forefront of the works of Sociedade and Educandário between the years 1938-1947, according to data from the Federation, collected in the work carried out by professors Francieli Lunelli Santos and José Augusto Leandro, from the State University of Ponta Grossa (SANTOS; LEANDRO, 2019).

In the research by Santos and Leandro (2019), a survey was carried out of Brazilian preventers and their boards, made up of women from the Federation, and in Educandário Santo Antônio, a preventorium from Maranhão, Maria Joaquina’s performance strictly followed the provisions of the Internal Regulations of the Preventories approved by the same Federation, in 1941, which reported on children who expressed an interest in studying (letters, arts or sciences) could study outside the establishment with all expenses paid. However, in reality, this did not happen, as the opportunities were extremely limited and the internees ended up having access only to the primary course, which was taught in the institutions. The regiment followed the norms of the Preventories Regulation of the National Department of Health, which regulated the time that children should stay in the institution.

19. The Prevention must consist of a nursery, an observation pavilion, general pavilions, a professional school, or a similar institution. 20. Children under 2 years of age and those born in leprosariums must be admitted to the nursery.

21. Children from 2 years of age up to 12 years of age, males, and females up to the age of majority, will be admitted to the general pavilions.

22. - Male children between 12 and 18 years of age must be sent to professional schools or similar institutions (BRASIL, 1939, p. 433).

Law Nº 610 of January 13, 1949, which established norms for the prophylaxis of leprosy nationwide, ordered state policies to guarantee education for children institutionalized in preventives: “Art. 26. Children who communicate with leprosy patients, hospitalized in preventive centers or received in homes, will be provided with social assistance, mainly in the form of primary and professional instruction, moral and civic education, and the practice of appropriate recreation” (BRASIL, 1949, not paginated). According to data from the Preliminary Report of the Working Group of the Secretariat for Human Rights and the .National Secretariat for the promotion of the rights of persons with disabilities, written in 2012, children admitted to these institutions did not receive the education guided by the legislation. Teaching was based only on learning to read, write, and mathematical operations (BRASIL, 2012). The Work it was an activity stimulated within the school, with order and discipline as impositions to maintain the good functioning of the institution.

Gomide (1991) reports that boys were interned in these spaces until they turned 18, and girls up to 21 years old, in an asylum without contact with their parents, as well as the whole community, only with authorized doctors and nurses. In the research carried out by the Maranhão social scientist Ellen Cristina Pinheiro Ferreira, in 2017, who used the methodology of oral history6 in her monographic work, there are the reports of graduates of the Educandário that bring information about the constitution of spaces and times of internal children. “The children residing at Educandário underwent constant sanitary control. The speeches of the children admitted to the institution suggest that the children were seen as possible receptacles of the disease” (FERREIRA, 2017, p. 15).

The investigation carried out with men and women who experienced the pain of separation from their families, highlights that the creation of these “anti-leper” institutions contributed to segregating and spreading prejudice against people who were taken to the hospitalization regime since they were isolated in places far from the urban perimeter. The boards that took over the administration of the school, knowing the consequences of this segregation, guided the omission of their own stories to the institution’s graduates, so that they could work and continue their lives, beyond the walls. “I suffered prejudice because we would look for a place to work and nobody would accept it, because if they knew it was the son of a sick person, they would not employ them at all” (FERREIRA, 2017, p. 33).

The State, in the speeches of representatives of the government and Assistance Societies, defended the protection of these children and the integrity of the lives of the egresses when they left the institutions to continue their lives, after isolation in the Educandário. However, after listening to the reports, Ferreira (2017, p. 34) states that “in reality, the state intervention with a pedagogical effect recommended in the Internal Rules of Education, followed by State agents, ended up promoting parental indifference”. When listening to the stories of these men and women, marked by discrimination and surveillance imposed by the illness of their family members and by the controlling policy of individuals, the form of differentiated treatment for children from Maranhão is clear. Those considered normal should have emotional bonds with their parents and be protected by law. As for those whose parents were hospitalized in the Colony, they must obligatorily keep their distance from their parents and their family and social life (FERREIRA, 2017).

It is known that several institutions responsible for ensuring the care of minors also end up being responsible for violations of the rights of these people. I have no intention of generalizing these criminal conducts by expanding them to all employees of these institutions. I just want to demonstrate the existence of this part of the population, affected by the leprosy prophylaxis policy, who did not have the disease, but who, like their leprosy parents, had to carry stigmas and undergo serious violations of human rights, resulting from the practices and inconsistencies of the State that was responsible for the physical and moral damage caused to these people, when removed from their homes and sent to establishments where the actions of employees were not supervised (FERREIRA, 2017, p. 35-36).

Mário7, a child sent to Educandário, now 77 years old, was one of the reports investigated by the researcher about daily life at the institution. Born in 1945, Mário was born in Colonia do Bonfim, and was institutionalized in the school the morning after his birth, residing there for 16 years. According to the report, there was no feeling of affection and esteem in living with the employees or with the parents, even if they were distant. The memories were not retrieved nor were the parental feelings that the children so badly needed, isolated in those spaces. He compared the treatment given by the employees and nuns who worked at the institution to the children, as “a bunch of animals on the loose”

[...] the children in the nursery had some wheelbarrows [...] they had a long iron [...] the iron stuck in the wall and they started to eat mud, clay from the wall [...] instinct of child! And the rate of children dying of anemia was high. [...] But no one was there monitoring, taking care, no! No one was there, no! (FERREIRA, 2017, p. 63).

Other reports referred to physical and verbal violence, told by Mário with great sadness and anguish. The lack of care of the people who worked at the Educandário with the children ended up causing situations of death and flight among the inmates, who suffered in the absence of their parents and family members, who were prevented from visiting the institution. Due to the lack of knowledge that these populations, mostly poor, had about leprosy and the prophylaxis policy, the government increased the level of information about the disease, alarming the inhabitants about the consequences of living with someone infected. This caused an increase in discrimination and excluded not only the sick but all their healthy family members from social life. These people were removed from the context of “a common and total creature, reducing themselves to spoiled and diminished people” (GOFFMAN, 2008, p. 66).

In 1950, with the publication of the Leprology Treaty, organized by the National Leprosy Service of the Ministry of Education and Health, with Dr. Ernani Agrícola, with a preface written by Gustavo Capanema, the Brazilian government brought together in one work a broad approach to the development of the disease since the colonial period. In chapter IX of the work, entitled The National State and the Prophylaxis of Leprosy in Brazil: the Cooperation of the Federation of Societies for Assistance to Lazarus and Defense against Leprosy, the agency explained the important role of women and the construction of a policy for the foundation of preventers and cooperation with state governments (BRASIL, 1950).

In the execution of these campaigns, the selfless ladies of the Federation traveled through numerous cities, seeking to awaken the conscience of the people by holding conferences, or utilizing the radio, leaflets, press, etc., always with the lofty purpose of raising funds for the complete fulfillment of their purposes. (BRASIL, 1950, p. 133).

Educandário Santo Antônio operated until the 1970s, continuing as a health care policy, but losing its initial objectives. It is not known exactly in what year the Educandário stopped receiving the children of the sick in São Luís, but its facilities were adapted to care for juvenile offenders since the Leprosy epidemic would have eased with the interventionist policy of the Vargas Government. Today it functions as a community nursery, still under the interests of the Eunice Weaver Foundation, presided over by philanthropic and religious institutions.

Final considerations

Assistance to children from Maranhão announced during the Estado Novo period configured an extravagant way of protecting children that acted in favor of invisibility and the erasure of the stories of stigmatized individuals. Considered leftovers of that society, the healthy children of leprosy patients were included in a policy whose rationality translated into the fabrication of an isolated and forgotten childhood. Revisiting the history of child protection institutions is a necessary epistemological path for us to consider these spaces as guidelines for public policies that, in the past, educated children based on the segregation of their bodies

Thus, discourses and practices produced in documents such as government reports and state decrees are privileged sources for understanding the performance of administrators with associations and other political groups interested in isolating children, such as the elite ladies, classifying individuals, and keeping the sick. away from the rest of the population, denying their identities. The actions of intellectuals such as leprologists ensured the circulation of nationalist ideas present in the Getulist dictatorship, which potentially excluded bodies weakened by leprosy from social coexistence. Subsequently, these policies marked the lives of children who were subjected to these so-called prophylactic measures, making them invisible in the course after leaving the institution.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, Antônio Martins de. Exposição apresentada a Getúlio Vargas pelo interventor Federal no Estado do Maranhão. São Luís: Imprensa Oficial, 1933. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Anais da I Conferência Nacional de Assistência Social aos Leprosos. Rio de Janeiro, 1939. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 610 de 13 de janeiro de 1949. Câmara dos Deputados: Rio de Janeiro, 1949. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Relatório Preliminar do Grupo de Trabalho Interno. Filhos segregados de pais ex-portadores de hanseníase submetidos à política de isolamento compulsório. SDH: Distrito Federal, 2012. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Tratado de Leprologia. Rio de Janeiro: Serviço Nacional da Lepra, 1950. [ Links ]

CÂMARA, Cidinalva Silva. O Começo e o Fim do Mundo: estigmatização e exclusão social de internos da colônia do Bonfim. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal do Maranhão, São Luís, 2009. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, Ellen Cristina Pinheiro. Filhos separados: entre construção de demandas e reconhecimento. Monografia (Graduação em Ciências Sociais) - Universidade Federal do Maranhão, São Luís, 2017. [ Links ]

GOFFMAN, Erving. Estigma: notas sobre a manipulação da Identidade Deteriorada (1963). São Paulo: LTC, 2008. [ Links ]

GOMIDE, Leila Regina Scalia. Órfãos de pais vivos: a lepra e as instituições preventoriais no Brasil: estigmas, preconceitos e segregação. Dissertação (Mestrado em História Social) - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 1991. [ Links ]

LISBOA, Achilles. Catecismo de defesa contra a Lepra. São Luís: Imprensa Oficial, 1936. [ Links ]

LISBOA, Achilles. A imigração e a Lepra. Revista de Geografia e História, São Luís, ano II, n. 2, 1947. [ Links ]

MACIEL, Laurinda Rosa. “Em proveito dos sãos, perde o lázaro a liberdade”: uma história das políticas públicas de combate à lepra no Brasil (1941-1962). Tese (Doutorado em História) - Universidade Federal Fluminense, 2007. [ Links ]

MARANHÃO. Decreto nº 799. Autoriza o Secretario Geral de Estado a assignar contracto com a firma Guilherme Bluhm, para fornecimento de materiais destinados as instalações do Leprosário da Ponta do Bonfim. São Luís: Imprensa Oficial, 1935. [ Links ]

MARANHÃO. Relatório apresentado ao Exmo. Sr. Dr. Getulio Vargas, presidente da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil pelo Dr. Paulo Martins de Souza Ramos, Interventor Federal no Estado do Maranhão. Maranhão: Imprensa Oficial, 1938. [ Links ]

MARANHÃO. Relatório apresentado ao Exmo. Sr. Dr. Getulio Vargas, Presidente da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil pelo Dr. Paulo Martins de Souza Ramos, Interventor Federal no Maranhão. Maranhão: DEIP, 1939. [ Links ]

MARANHÃO. Relatório apresentado ao Exmo. Sr. Dr. Getulio Vargas, Presidente da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil pelo Dr. Paulo Martins de Souza Ramos, Interventor Federal no Maranhão. Maranhão: DEIP, 1941. [ Links ]

MARANHÃO. Relatório apresentado ao Exmo. Sr. Dr. Getulio Vargas, Presidente da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil pelo Dr. Paulo Martins de Souza Ramos, Interventor Federal no Maranhão. Maranhão: DEIP, 1942. [ Links ]

PAVANI, Elaine Cristina Rossi. O controle da “Lepra” e o papel dos preventórios: exclusão social e interações socioespaciais dos egressos do Educandário Alzira Bley no Espírito Santo. Tese (Doutorado em Geografia) - Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, 2019. [ Links ]

PINTO NETO, José Martins et al. O controle dos comunicantes de hanseníase no Brasil: uma revisão da literatura. Hansenologia Internationalis, Bauru, SP, v. 25, n. 2, p. 163-76, 2000. Disponível em: https://periodicos.saude.sp.gov.br/hansenologia/article/view/36440. Acesso em: 25 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

RAMOS, Paulo Martins de Souza. Exposição ao povo maranhense. São Luís: Imprensa Oficial, 1938. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Francieli Lunelli; LEANDRO, José Augusto. Mulheres da Federação das Sociedades de Assistência aos Lázaros e Defesa Contra a Lepra, 1926-1947. História, Ciências, Saúde, Manguinhos, RJ, v. 26, p. 57-78, 2019. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/hcsm/a/RRjBPZx7gDMTKbkCJ6TrTyh/?lang=pt. Acesso em: 15 ago. 2022. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Vicente Saul Moreira dos. Filantropia, poder público e combate à lepra (1920-1945). História, Ciências, Saúde, Manguinhos, RJ, p. 253-74, 2011. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/hcsm/a/8sD4DNVVgvwzWbJsqdNhW8M/?lang=pt. Acesso em: 11 ago. 2022. [ Links ]

SOUZA-ARAUJO, Heraclides-Cesar de. História da lepra no Brasil: período republicano: (1889 - 1946): album das organizações antileprosas. Rio da Janeiro: Departamento de Imprensa Nacional, 1948. 380 p. [ Links ]

1This article presents the results of the doctoral thesis concluded in the Graduate Program in Education at the Federal University of São Paulo, Guarulhos, SP, developed under the guidance of Prof. Dr. Celia Maria Benedicto Giglio, in the Education, State, Work Research Line, in the Educational Assessment and Policies Research Group.

2The studies by these authors brought important contributions to research focused on public health, from the Proclamation of the Republic to the present day.

3Statistics of the number of patients with Leprosy in Brazil carried out from 1933 onwards, updated annually by each state.

4Doctors, nurses, and security guards visited places, such as residences, and forcibly conducted the probable diagnoses of leprosy in the city. Embarrassing and violent situations marked these episodes decorated as prophylactic and healing.

5The Society for Assistance to Lazaros and Defense against Leprosy began its activities in Brazil in the city of São Paulo, where it was founded in 1926. The founding meeting took place at the home of Jorge Tibiriçá, a descendant of a political family and married to Alice Tibiriçá, responsible for calling the meeting to found the society of assistance to the children of the Lázaros.

6The oral history methodology aims to rescue memories and personal facts through the storytelling done by individuals who lived through the experiences using structured interviews, which will then be analyzed to compose an interpretation of the past, not found in documents.

Received: September 07, 2022; Accepted: June 06, 2023

texto em

texto em