Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista da FAEEBA: Educação e Contemporaneidade

versión impresa ISSN 0104-7043versión On-line ISSN 2358-0194

Revista da FAEEBA: Educação e Contemporaneidade vol.31 no.67 Salvador jul./set 2022 Epub 13-Ene-2023

https://doi.org/10.21879/faeeba2358-0194.2022.v31.n67.p268-287

Articles

TERRITORY MITÃ KUERA: THE MULTIETHNIC SETTING OF BEING AN INDIGENOUS CHILD

*Master’s sutdent form the Postgraduate Program in Educacionand Interculturality (PPGET) at the Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados. Teacher of the Basic Educacion. E-mail: adrieli.marques18@gmail.com

**Doctorate in History from the Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (UFGD). Professor at the Postgraduate Program in Educacion and Interculturality (PPGET). Professor of the Graduate Course inIndigenous Intercultural Licentiate (Teko Arandu) at the Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (UFGD). E-mail: cassioknapp@ufgd.edu.br

***Doctorate in Agronomy - Plant Procuction - from the Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (UFGD). Professora at the Postgraduate Program in Educacion and Interculturality (PPGET). Professora of the Graduate Course in Rural Educacion (LEDUC) at the Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (UFGD). E-mail: andreiasangalli@ufgd.edu.br

The Mitã Kuera territory, the territory of the indigenous child, was affected by the world scenario experienced since the beginning of 2020, and had to adapt to changes resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic. In this context, the main objective of the present study was the characterization of the universe of the Guarani and Kaiowá indigenous children, in the Dourados Indigenous Reserve (RID) during this period, listing the changes in the individual and family way of life of indigenous children in situations of social isolation. The development of the research was based on different strategies of the qualitative approach including literature review, ethnographic research and field research (at this time restricted to on-site visits to the municipal indigenous schools of the Dourados Indigenous Reserve). For now, the research contributes by reaffirming that indigenous children try on, experience and transmit their cultures and also their knowledge among themselves and with the adults they live with. When considering the current scenario, indigenous children sought to adapt to social isolation, without losing the essence of playing and being a child. As for the school education process, traditional educational practices are pedagogical movements that are developed throughout the growth of indigenous children and reveal knowledge necessary for the formation of culture and identity.

Keywords: indigenous childhood; indigenous school education; interculturality

O território Mitã Kuera, território da criança indígena, foi afetado pelo cenário mundial vivenciado desde o início de 2020, tendo que adaptar-se às mudanças resultantes da pandemia por Covid-19. Nesse contexto, o objetivo central de investigação foi a caracterização do universo das crianças indígenas Guarani e Kaiowá, na Reserva Indígena de Dourados (RID), durante esse período, elencando as mudanças no modo de viver individual e familiar das crianças indígenas em situação de isolamento social. O desenvolvimento da pesquisa pautou-se em diferentes estratégias que se inserem na abordagem qualitativa, dentre elas a revisão bibliográfica, a pesquisa etnográfica e a pesquisa de campo (nesse momento restrita a visitas in loco nas escolas indígenas municipais da Reserva Indígena de Dourados). Para o momento, a investigação traz contribuições no sentido de reafirmar que as crianças indígenas experienciam, vivenciam e transmitem suas culturas e também seus saberes entre si e com os adultos que convivem. Ao considerar o atual cenário, as crianças indígenas buscaram adaptar-se às condições de isolamento social, sem perder a essência do brincar e do ser criança. Quanto ao processo de educação escolar, as práticas educativas tradicionais constituem movimentos pedagógicos que vão se desenvolvendo ao longo das fases de crescimento das crianças indígenas e revelam saberes necessários para a formação da cultura e da identidade.

Palavras-chave: infância indígena; educação escolar indígena; interculturalidade

El territorio Mitã Kuera, territorio del niño indígena, fue afectado por el escenario mundial vivido desde el inicio de 2020, teniendo que adaptarse a los cambios resultantes de la pandemia por Covid-19. En ese contexto, el objetivo central de investigación fue la caracterización del universo de los niños indígenas guaraníes y kaiowá, en la Reserva Indígena de Dourados (RID) durante ese período, enumerando los cambios en el modo de vivir individual y familiar de los niños indígenas en situación de aislamiento social. El desarrollo de la investigación se desarrolló en diferentes estrategias que se insertan en el abordaje cualitativo, entre ellas, la revisión bibliográfica, la investigación etnográfica y la investigación de campo (en ese momento restringida a visitas in loco en las escuelas indígenas municipales de la Reserva Indígena de Dourados). Por el momento, la investigación aporta contribuciones en el sentido de reafirmar que los niños indígenas experimentan, vivencian y transmiten sus culturas y también sus saberes entre sí y con los adultos que conviven. Al considerar el actual escenario, los niños indígenas buscaron adaptarse a las condiciones de aislamiento social, sin perder la esencia del juego y del ser niño. En cuanto al proceso de educación escolar, las prácticas educativas tradicionales constituyen movimientos pedagógicos que se van desarrollando a lo largo de las fases de crecimiento de los niños indígenas y revelan saberes necesarios para la formación de la cultura y de la identidad.

Palabras-clave: infancia indígena; educación escolar indígena; interculturalidad

Introduction1

This research was carried out during the world scenario experienced since the beginning of 2020, which required changes in behaviors and attitudes in order to survive a pandemic resulting from Covid-19. In this context, the focus of the study was the indigenous child, with the central objective of investigation to characterize the way of being and living of Guarani and Kaiowá indigenous children in the Dourados Indigenous Reserve (RID) in terms of time and space2 during the Coronavirus Pandemic (Covid-19), listing the changes in the individual and family way of living without disregarding, however, that this is a socio-historically constructed territory by the State and that also affects the ways of living of these children. The understanding of the territory by indigenous children is in line with Fernandes (2008, p. 3):

When analyzing space, we cannot separate systems, objects and actions, which complete each other in the movement of life, in which social relations produce spaces and spaces produce social relations. From this perspective, the starting point contains the arrival point and vice versa, because space and social relations are in full motion in time, building history. This uninterrupted movement is the process of producing space and territories.

The intention of recording the changes, some spatial and temporal, in the Territory of the Guarani and Kaiowá indigenous children in the Dourados Indigenous Reserve is an opportunity to produce records about the knowledge of the Guarani and Kaiowá indigenous culture and, above all, the way of being and living of the indigenous child. With regard to studies on Indigenous Children, “it is essential to start from the space in which children live, it is important to take into account their values, customs, rituals, beliefs and, finally, the Guarani and Kaiowá way of being, the ‘ñande Reko” (MACHADO, 2016, p. 17).

In the historical-social perspective, it is understood that childhood is a socially constructed concept and the result of the historical development of humanity. Therefore, the idea of a unique childhood, abstract and disconnected from the dynamics of society cannot be sustained, as children are beings with different histories and experiences, having different mechanisms, requirements and conditions to be part of the social environment in which they live. (MORAIS, 2020, p. 33).

Indigenous early childhood education is constituted in several formative spaces: the family, the school space, the media, the relationships with their people, and with the karai, for the Guarani and Kaiowá indigenous people, the “others”, that is, the non- Guarani and/or Kaiowá. In agreeing with Kramer (2007, p. 16) that “child culture is, therefore, production and creation and that children produce culture and are produced in the culture in which they are inserted (in their space) and which is contemporary to them (in their time)”, it is necessary to look at indigenous children from the new life situations.

Among the situations, it is intended to deepen the debate on indigenous school education in order to show how the indigenous school has dealt with children’s time and space, considering that, previously, the presence of the school, the knowledge and the educational process were based on the transmission of knowledge from parents to children. And supported by Knapp (2020), it is also necessary to be attentive to school standards established in the territories, as schools must guide their own pedagogy, based on their territorial context.

When debating the construction of an indigenous school that takes into account indigenous pedagogy for effective interculturality, one cannot forget that each school is part of a different reality, and this is accentuated when indigenous schools of different peoples are compared. (KNAPP, 2020, p. 86).

From this proposition, an initial question arises: how has the school encompassed the specificities of indigenous children and contributed to guaranteeing the transmission of indigenous cultures that circulate in the school space? In an attempt to answer this question, we sought to characterize the current panorama of indigenous schools existing in the territory of the Dourados Indigenous Reserve, in terms of the provision of basic education and assistance to indigenous students.

Another existential milestone, which impacted child development and the educational process, is the Covid-19 pandemic. In view of this new life situation, this study sought to understand how the daily life of the child in the community was materialized in terms of the way of being and living in the family, children’s play, and the necessary adaptations to provide formal education due to the suspension of faceto-face activities in indigenous schools during the pandemic period.

Research locus and methodologies

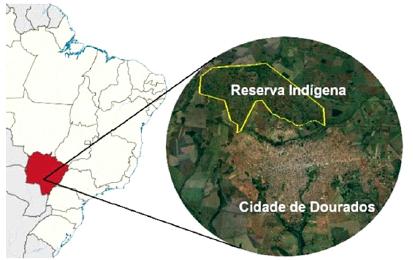

The Dourados Indigenous Reserve (RID) was created in 1917 by the former Indigenous Protection Service (SPI), among one of the 8 reserves demarcated to bring together the indigenous people who lived in the present south of the state of Mato Grosso do Sul in the context of agropastoral expansion for the occupation of space by non-indigenous colonization. This reserve is made up of the Jaguapiru and Bororó villages, with an official area of 3,475ha, and is located in the municipality of Dourados, state of Mato Grosso do Sul (Figure 1). In 2014, the number of indigenous people was 15,023, belonging to the Guarani Kaiowá and Guarani Ñandeva3 (Tupi-Guarani linguistic family) and Terena (Aruak linguistic family) ethnicities.

Among the investigative alternatives comprising the universe of qualitative research is the ethnographic methodology, which allows an analysis based on the experience of problem-situations, as “it is based on observation, on the record of the field diary, on conversations and interviews. The researcher remains immersed in the environment to be researched for a certain time [months or years]” (OLIVEIRA, 1994, p. 25).

To approach the territory and the role of indigenous children, the theoretical basis was anchored in indigenous researchers: Aquino (2012), Machado (2016), João (2011), Lescano (2016) and Morais (2020); and non-indigenous researchers who promote debates on territory, territorialities, intercultural education from an external perspective, among them: Fernandes (2008), Knapp (2020), Castro (2017) and Martins (2018).

The sudden changes caused by this pandemic situation and experiencing this process aroused a feeling of obligation to record the lives of indigenous children and the necessary adjustments for that time, especially in the educational context in the indigenous villages of Dourados. To deepen the analysis and reflections on this topic, a documentary study was carried out based on municipal legislation and guidelines, as well as school guidelines for students during the suspension of classes, which lasted from March 2020 to December 2021, and in the process of planning the return to face-to-face activities (started in the second half of 2021).

And, to diagnose the real situation of indigenous schools during the pandemic period, on-site visits were carried out to five schools in the area of the Indigenous Reserve, between August and October 2021. During this period, only managers and teachers were present in schools, following a relay schedule, as classes remained suspended. Thus, we sought, through dialogue with managers, to gather information about the way in which schools were organized to serve students and parents and to develop pedagogical activities. It should be noted that dialogues were permeated with uncertainties in the functionality of methods applied to the pedagogical service, and insecurities about the face-to-face return, when and how it would be, how many students would return to schools, how to follow the biosafety rules for preventing contagion among students.

Anchored in data provided by school managers and in information collected in the documentary study, the results are structured on the analysis of two categories: indigenous childhood and the indigenous child. The approach to childhood emphasizes the life territory of the indigenous child and the necessary readaptations in times of Covid-19. And, in order to highlight the scenario of indigenous students returning to schools after a long period of non-face-to-face school education, indigenous school education was discussed before and during the pandemic, emphasizing the impasses and alternatives found to maintain the provision of school education for indigenous children.

Childhood in the Dourados Indigenous Reserve

In the Dourados Indigenous Reserve, there is a continuous process of space alteration, which reflects on the transformation of indigenous children development. There is a lot of talk about territorial issues of this indigenous reserve, that is, about a reality that needs to be broadened, especially in relation to indigenous children living in a space of precarious territorialization, understood by Mota (2011, p. 160) as

[...] the recreation and reproduction of the way of life of these societies in the precepts of Tekoyma, considering that the reserve is fundamentally the expression of the incorrect way of living (Teko Vai). The precariousness of living in the RID implies in territorial resizing that constitute other Guarani and Kaiowá territorialities and multi-territorialities. It also implies the construction of new frontiers of encounter and disencounter with the other, new ways of imagining others, of being and being in the world.

Given the context of population density, this Indigenous Reserve, which we call home, is experiencing an aggravation of the precariousness process described by Mota (2011). Our indigenous people suffer from a lack of natural resources: lack of drinking water, no forests and the little remaining soil is not always suitable for production, which are relevant factors for the sustainability of indigenous peoples. Currently, many indigenous families practice subsistence agriculture, although this practice was not part of indigenous culture; but today it is necessary, since the population faces difficulties in terms of food.

When we refer to children, we know that they are experiencing a process of transformation of their traditional way of living, because each one knows that in the very near future, when they start their family, they will be in even smaller lands, so we see that we need to expand our territories and leave what Brand (2008, p. 25) characterizes as confinement.

This population was subjected to an extensive confinement process, with the loss of territory and the commitment of natural resources relevant to sustainability. Spatial confinement also created special difficulties for social organization of this population and its autonomy. The process of territorial confinement was accompanied by the imposition of the national, non-indigenous school system, which historically played an important role in the policies of integration of indigenous people into national society.4

The Guarani and Kaiowá culture has undergone changes and resignifications influenced by historical issues. The processes to maintain their traditions, as well as their language, were crucial aspects to be considered in the history of this indigenous people, but the Brazilian State, in view of the indigenous as a transitory category, felt/feels in the right to expropriate their land, separate them from nature.

The Brazilian State and its ideologues always bet that the indigenous people would disappear, and the sooner the better; they did the possible and the impossible, the nameless and the abominable to do so. Not that it was always necessary to physically exterminate them for that - as we know, however, the resort to genocide remains widely in force in Brazil -, but it was nevertheless necessary to de-indigenize them, transform them into ‘national workers’. Christianize them, ‘dress’ them […] above all, sever their relationship with the land. Separating the indigenous (and all other indigenous) from their organic, political, social, vital relationship with the land and with their communities that live off the land - this separation has always been seen as a necessary condition to transform the indigenous into a citizen. In a poor citizen, of course. Because without the poor there is no capitalism, capitalism needs the poor, as it needed and still needs slaves. (CASTRO, 2017, p. 5).

In this way, considering the changes in the way of being Guarani and Kaiowá, the way of being a child in the RID has also been transformed, which is sometimes not even understood internally, as some attitudes come to be understood, even by leaders, as acts of rebellion. In Lescano’s reflections (2016, p. 51),

It is necessary to think of the culture and teko that form the current identity as elements of resistance, the appropriation and knowledge of these two fields of force is extremely important to continue maintaining and building cultural protection. Today, internal and external values are already known and are constantly changing, which also creates the way of being of the poor, disorganized, confused, unprepared people. The cultural elements of the Kaiowá were shaken and many have already been replaced with other values, which the omba’ekuaáva - prayers and elders - call false ha’e raanga, which is no longer true. The knowledge of communities has already suffered and still suffers a constant bombardment of information that is everywhere, by mechanical and immaterial means, from outside, which are no longer outside, both blend together to continue to stabilize.

Returning to the cultural origins of children, the understanding of these specificities by indigenous leaders would be a way to establish effective actions for a better understanding of childhood. Therefore, it would be necessary to urgently look at all forms of violence and exploitation to which many children are subjected, in addition to the prejudice they already suffer for being indigenous. As Fernandes (2008, p. 5) points out, leaders can contribute a lot:

Each institution, organization, subject, etc., builds its territory and the content of its concept, as long as it has the political power to maintain them. These territory creators explore only one or some of its dimensions. This is also a political decision. However, when exploring one dimension of the territory, it reaches all the others because of the principles of totality, multiscalarity and multidimensionality. Understanding each type of territory as a totality with its multidimensionality and organized at different scales, based on its different uses, allows to understand the concept of multi-territoriality. Considering that each type of territory has its territoriality, the relationships and interactions of the types show us the multiple territorialities. It is for this reason that the policies implemented in the territory as property affect the territory as a space of governance and vice versa.

Source: Field research archive.

Figure 2 Guarani and Kaiowá children putting out fire in the Dourados Indigenous Reserve.

The children, even if they are small, understand that the territory of the Dourados Indigenous Reserve has been affected and degraded by the proximity to the urban center of the city of Dourados. There are facts that show how necessary action is, and often it will be the children who will participate, to advance or to acquire their rights. Figure 2 shows a fire in the Jaguapiru Village and the action of children, who with great courage went to put out the fire so that it did not reach the adjacent woods. What is exciting is that the Guarani and Kaiowá indigenous children were not paralyzed by the fear of flames, but understanding the harm that the fire would do to the village, they organized themselves as possible to put out the fire. In situations like this, children act with an instinct to defend the preservation of life on Earth, characterized in their ancestry.

Each child has their own way of observing, learning, being shaped according to the place of experience, with the traditions and customs experienced in the family space, because, as Gallois (2006) points out, the existing space and time are no longer the same as in the past. Social changes point to the current situation. Children bring with them knowledge that is passed on from generation to generation, in conversation circles, when playing and helping their parents; and these are updated or resignified knowledge and give continuity to cultures. These identities, as described by MOTA (2011, p. 253),

[...] are made and unmade in the intertwining of experienced territorialities, in the transit of living across borders, therefore, between multiple territories, allowing different forms of identification with the space and with the people of/in the lived spaces, as well as enable the participation of multiple territorialities, since there is an intensification of encounters with the other, hitherto unknown.

These processes have been experienced by indigenous children, who participate and occupy different spaces. In the corner of the Aty Guassu (Great Assemblies of the Guarani and Kaiowá) groups, they were there, listening and learning. As Bhabha (2010, p. 21) highlights:

By reenacting the past, it introduces other immeasurable cultural temporalities in the invention of tradition. This process removes any immediate access to an original identity or ‘received’ tradition [...], realigns the usual boundaries between public and private, high and low, as well as challenging normative expectations of development and progress. Even with difficulties of safeguarding customs and beliefs through so much transformation, we know that children are the only ones who can carry knowledge forward.

Indigenous childhood in times of Covid-19

When considering the different realities of existence of Brazilian indigenous peoples, they have always lived in constant social, economic, cultural and environmental conflicts. In the RID, these conflicts include issues related to social organization, indigenous health, indigenous schools, lack of infrastructure, with emphasis on basic sanitation. In addition to these confrontations, in 2020 the future of our indigenous generations was crossed by a new sanitary reality, resulting from the new coronavirus (Covid-19), which further opened up the existing sociocultural inequalities and amplified the ills in indigenous communities.

The Guarani and Kaiowá understand the coronavirus as a reflection of the current world we live in, being the announced result of human disrespect that generates an imbalance in nature. They remember the weeping, the tears of our Nhandesy Alda Silva, when her Oga Pysy (Casa de Reza) was criminally burned in July 2019 at RID. And there, in great clamor, she expressed her attempt, along with her husband Nhanderu Getúlio Juca, to save the Xiru - an altar with spiritual meaning, which is the space where dialogue with the sacred takes place. For not being able to save him, they lamented: “There is nothing to be done, many terrible things will come for humanity, mainly diseases and hunger.” And that time has come, less than a year later.

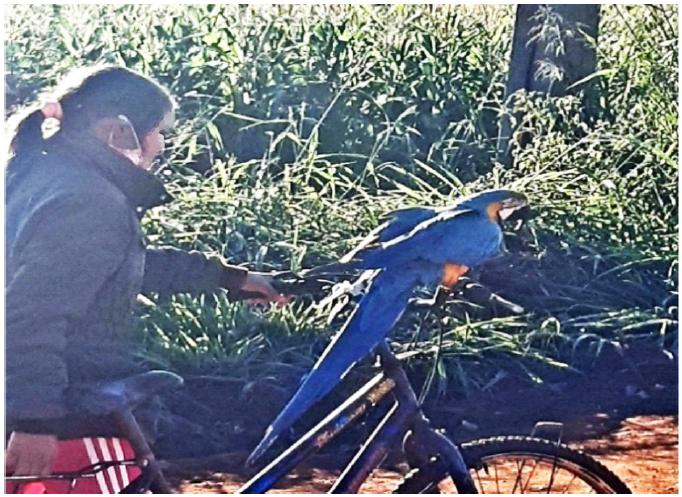

And, at that moment, indigenous children also somehow knew how to adapt to this time, whether at home, at school and/or in their daily living context. In other times, when the natural areas of the RID were preserved, indigenous children used to meet to play in the trees, to bathe in the rivers. Currently, Guarani and Kaiowá children no longer have many spaces with natural resources for fun. For this reason, among the games they perform, individually or collectively, are playing in tree tops, cycling on RID roads and playing with wild animals (Figures 3, 4 and 5).

Aquino (2012) observed the development process of Guarani and Kaiowá children in the Amambai Reserve, a scenario similar to the RID, and described games as learning mechanisms:

Learning happens through play, imitation, observation and in different ways, an informal school without rules, they learn and complement to meet their needs, they assimilate the real ways of each phase of their life, fulfilling the rituals of each phase of passages that each people has. The children world is very interesting, there are mysteries that they pass on to adults and I need to decode the messages that the little ones give us. (AQUINO, 2012, p. 93).

These records demonstrate the experience of Guarani and Kiowá children and the relationships they establish with nature in their territory. On this is based the importance of understanding the current universe in which childhood develops, the relationships they establish with the family, and the lived experiences, as these aspects are essential for identity construction and for the choices they will make (MACHADO, 2016). And, “when they live together and exercise the values of their culture, they also relativize things, the sense of ownership and value the playful and collective aspects... Toys, most often harvested from nature, do not need to be kept, cleaned, conserved, disputed” (NOAL, 2006, p. 16).

Source: Field research archive.

Figure 5 Child playing with a baby monkey found in forest fragments present in the village

In the RID, Guarani and Kaiowá children are constantly around adults and always seek to participate in collective activities, or in conversations, to hear stories told. Learning with children, and also teaching them, has a meaning of preserving life, because it is through these moments, together with the community, school and family, that strategies are developed to maintain the natural biodiversity of the different terrestrial ecosystems and aquatic habitats present in indigenous territories, even in the face of the numerous interferences to which they are subjected, as pointed out by Machado (2016, p. 21):

Families seek to safeguard the cosmology, spirituality and beliefs that they still know and that are passed on by their elders. However, it is important to highlight that the transmission of the original and traditional culture suffered interference from policies arising from the colonizing process and state policies. Ancestral knowledge and spiritual rituals were less and less transmitted to new generations, due to restrictions or even forgetfulness. However, even with so many social changes and interference, the Guarani and Kaiowá people still seek to live the ‘ñande reko’, that is, the indigenous way of life.

As part of the culture, the indigenous child is always at the side of their parents and grandparents, but when it is necessary for them to be alone or take care of their siblings, they play the role of authority in the midst of other children. Thus, children try on, experience and transmit their cultures and also their knowledge among themselves and with the adults they live with (GUTIERREZ, 2016, p. 24).

In the case of the Guarani and Kaiowá culture, children are considered thinking beings and reproducers of knowledge and when an adult is not around, it is the older child who assumes the role of the adult, caring for and protecting younger children with the same responsibility as the adult. (AQUINO, 2012, p. 47).

It is necessary to include in this debate the rituals present in the Guarani and Kaiowá culture. Indigenous children, from birth, undergo a series of rituals, which are necessary for their development, that is, for their well-being.

The stages of development are passages occurring throughout the life of the Guarani, as a process of growth and maturity. It is about the formation of the person, according to the ñande reko - own way of being to become a good Guarani or Kaiowá, as well as for affirmation of the collectivity, the construction and continuous strengthening of the identity as a differentiated people, maintaining the operation of the gear of knowledge, from cultural elements already presupposed. (LESCANO, 2016, p. 37).

These rituals aim at a healthier development, within the understanding that for the Guarani and Kaiowá the body is safeguarded from evils, that is, by going through these rituals the body will be protected, with greater resistance to diseases. This would be one of the reasons why the indigenous children of the RID have been less affected by the evils caused by Covid-19.

This situation allows to reflect on the fact that the Kaiowá child is considered a small inhabitant of the land and, consequently, runs a greater risk of being affected by evil spirits. To protect the body and soul of the newborn, it is necessary, for example, that the child undergoes a specific ritual, which is extremely focused on the aspect of their soul. After this soul is fixed in the child’s body, which is more safely done through prayer, the xamã instructs the mother giving numerous basic guidelines on the care of the newborn. If the newborn is well cared for, it will behave well when it reaches adulthood, respecting the social rules of society and the Kaiowá deities (JOÃO, 2011, p. 25).

Thus, the territoriality, spatiality and temporality of the indigenous child are expressed through knowledge of trees, knowledge of forms of nature, of waters, of what is essential to indigenous life. And “even under adverse life conditions, Guarani and Kaiowá children receive cultural teachings for the construction of an ethnic identity and also learn to live in different spaces with other ethnicities and with non-indigenous people” (MACHADO, 2016, p. 21), and exercise the transmission of knowledge, traditions and cultures of their people, including in the act of playing.

The indigenous child and school education

When considering the consolidation format of the RID, which is not a single traditional Tekoha, but multiple Tekoha kuera occupied by various kinships, including different ethnicities, schools have been established over the years to meet local demand. In the Bororó village are located the Agustinho Municipal Indigenous School, the Araporã Municipal Indigenous School and the Lacuí Roque Isnarde Municipal Indigenous School. In the Jaguapiru village are located the Tengatuí Marangatu Municipal Indigenous Polo School, the Ramão Martins Municipal Indigenous School and the Guateka - Marçal de Souza State Indigenous Integral High School. There is a seventh school, the Francisco Meireles Municipal School, which is located on the edge of the RID area, more specifically in the Kaiowá Mission, but is recognized as an indigenous school for primarily serving indigenous children and adolescents.

Considering the presence of this number of indigenous schools in the RID, it could be said that there is a peculiar service guaranteed to indigenous children, adolescents and young people, and according to cultural specificities of ethnic groups present in these school spaces. Nevertheless, as observed by several other researchers, especially Machado (2016, p. 18), “[...] school education is also part of the lives of these children in the village, and brings a standard model of the urban school. The challenge of the present time is to find proposals and a dialogue between ancestral and schooled education”.

Even treading paths to offer schools organized to meet the indigenous time and space and that provide dialogue between the cultures present in this territory, the organizational guidelines, academic calendars, contents and pedagogical practices are still established from what is proposed for urban schools. The absence of investments and qualification through continuous training is also a reality.

Briefly historicizing the process of consolidation of indigenous school education, since the Federal Constitution enacted in 1988, indigenous communities have been officially recognized as having the right to offer their own school education.

Art. 210. Minimum contents will be established for basic education, in order to ensure common basic training and respect for cultural and artistic, national and regional values. [...] § 2º Regular elementary education will be taught in Portuguese, ensuring that indigenous communities are also able to use their mother tongues and their own learning processes. (BRASIL, 1988).

At the end of the 1990s, the following were published: Opinion CNE/CEB 14/1999, which deals with the National Guidelines for the operation of indigenous schools; and Resolution CEB 3, which established the National Guidelines for the operation of indigenous schools (BRASIL, 1999).

In 2002, the Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity proposed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) established the inclusion of cultural diversity as a fundamental theme in school education and teacher training, as verified in the General lines 7 and 8 of the Action Plan, which should:

7. Promote, through education, an awareness of the positive value of cultural diversity and to improve, to this end, both the design of school programs and the training of teachers. 8. Incorporate traditional pedagogical methods into the educational process, as much as necessary, in order to preserve and optimize culturally appropriate methods for the communication and transmission of knowledge. (UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION, 2002, p. 7).

In 2009, Decree 6861/2009 instituted the organization of Indigenous School Education in ethnoeducational territories, defining that:

Each ethnoeducational territory will comprise, regardless of the political-administrative division of the country, indigenous lands, even if discontinuous, occupied by indigenous peoples who maintain intersocietal relationships characterized by social and historical roots, political and economic relationships, linguistic affiliations, shared cultural values and practices. (BRASIL, 2009).

And in 2012, the National Curriculum Guidelines for Indigenous School Education in Basic Education were sanctioned through the CNE/CEB Opinion 13/2012, approved on May 10, 2012 (BRASIL, 2012a), and the CNE/ CEB Resolution 5, on June 22, 2012 (BRASIL, 2012b). One of the highlights is in Article 9, Paragraph 1, in which “Elementary Education must guarantee indigenous students favorable conditions for the construction of good living in their communities, combining, in their school education, scientific knowledge, traditional knowledge and their own cultural practices” (BRASIL 2012b).

Following the regulations for Indigenous School Education, and in order to meet the demands of schools regarding the provision of specific training for indigenous teachers, Opinion CNE/CP 6/2014, approved on April 2, 2014 (BRASIL, 2014) and Resolution CNE/CP 1, of January 7, 2015 (BRASIL, 2015), established the National Curriculum Guidelines for Training Indigenous Teachers in Higher Education and High School Programs.

Thus, there is an understanding that the challenge would no longer be legislative, since within what we expose here, there is already an important contribution on the recognition of a schooling process that includes respect for the languages and cultures of indigenous peoples in Brazil. In addition to this scenario, as of 2018, Basic Education has the Common National Curriculum Base (BNCC) as a guiding and unifying document. When verifying which proposals guarantee the specificities of indigenous schools, the BNCC proposes:

Ensure specific skills based on the principles of collectivity, reciprocity, integrality, spirituality and indigenous alterity, to be developed from their traditional cultures recognized in the curricula of teaching systems and pedagogical proposals of school institutions. It also means, in an intercultural perspective, considering their educational projects, their cosmologies, their logics, their own pedagogical values and principles (in line with the Federal Constitution, with the International Guidelines of the ILO - Convention 169 and with UN and UNESCO documents on indigenous rights) and their specific references, such as: building intercultural, differentiated and bilingual curricula, their own teaching and learning systems, both for universal content and indigenous knowledge, as well as teaching the indigenous language as a first language. (BRASIL, 2018, p. 17-18).

Investigating the recommendation that the BNCC establishes on the provision of intercultural education, there is only mention of this offer in the Arts discipline:

The complexity of the world, in addition to favoring respect for differences and intercultural, pluriethnic and plurilingual dialogue, which are important for the exercise of citizenship, are characteristics to be developed for Elementary School, in the Art syllabus that includes Visual Arts, Dance, Music and Theater. (BRASIL, 2018, p. 193).

Despite these two highlights emphasizing the importance of intercultural education, the BNCC emphasizes the effectiveness of interculturality only in the relationship between learning other languages, and, in this case, the English language. And although the proposition referring to the intercultural dimension mentions the interaction between contemporary cultures, Brazilian indigenous traditional cultures remain invisible.

The proposition of the intercultural dimension axis is born from the understanding that cultures, especially in contemporary society, are in a continuous interaction and (re) construction. In this way, different groups of people, with different interests, agendas and linguistic and cultural repertoires, experience, in their contacts and interactional flows, processes of constitution of open and plural identities. (BRASIL, 2018, p. 245).

In this dynamic process, today’s indigenous school is still seeking to meet the objectives established in the past, which advocate:

[...] the conquest of the socioeconomic-cultural autonomy of each people, contextualized in the recovery of their historical memory, in the reaffirmation of their ethnic identity, in the study and valuing their own language and science - synthesized in their ethno-knowledge, as well as access to information and technical and scientific knowledge of the major society and other societies, indigenous and non-indigenous. The indigenous school has to be part of the education system of each people, in which, while ensuring and strengthening the indigenous tradition and way of being, it provides the elements for a positive relationship with other societies, which presupposes that indigenous societies fully master their reality: understanding the historical process in which they are involved, critical perception of values and counter-values of the surrounding society, and the practice of self-determination. (BRASIL, 1994, p. 12).

Even in the face of the right to a proper school education, Machado (2016, p. 18) points out that the education of Guarani and Kaiowá indigenous children in the Dourados region occurs, in a way, by the traditional way of these peoples, transmitted from generation to generation by families, but often the school belittles traditional knowledge, as if there was no value in knowing and being indigenous, resulting in a neglected indigenous school education.

The current reality, therefore, continues to repeat the context of previous times, in which there is a dichotomy in the formation of indigenous children during the school period: they come into contact with the knowledge of Western society, but when they return to family life, they experience the knowledge traditions that are part of their daily lives. Thus, in this dichotomy, indigenous culture continues to be denied and overlapped by Eurocentric culture, preventing the ideal intraculturality from taking place.

Intraculturality consists of a social process starting from the awareness, by the indigenous people, that arises with the taking of the reins of their own history, from the most remote records of their historical memories and their ancestry, seeking to learn in the struggles and resistance against all forms of discrimination, oppression and forced integration. It is the combination of two factors: an internal one (tradition) and an external one (modernity), a characteristic situation of Brazilian and Latin American indigenous society. (MARTINS, 2018, p. 58).

Based on what Martins (2018) has exposed, a path to the indigenous school can be noticed. The exercise of intraculturality that allows collective and integrated work between teachers, managers and the school community to value indigenous ancestral knowledge that circulates in these spaces, since it can consist of a pedagogical practice of valuing the subject and its territory.

Impasses and alternatives of indigenous school education in times of Covid-19

With the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic, the official suspension of face-to-face classes at the Dourados Municipal Education Network took place in March 2020, and the regulation of non-face-to-face pedagogical activities, as of Resolution 2020 (DOURADOS 2020). Based on this regulation, the Indigenous Schools sought several ways to reach their students, but many of the families were, and still are, in a situation of extreme vulnerability, being inaccessible via technological instruments to continue the school calendar.

The Brazilian education as a whole needed to organize actions in order to maintain the bonds of students and families with educational institutions and this stressed the debate in the first stage of Basic Education. Certain groups and educational agents have stood up in defense of the use of technological resources also for working with children in Early Childhood Education, as has been done in other stages of Basic Education and Higher Education. (ANJOS; FRANCISCO, 2021, p. 127).

Seffner (2021) analyzes some impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on the Brazilian public educational field, when looking at the effects of the prolonged period of isolation. Regarding the school and the schooling processes, discourses on Distance Education (DE) as an alternative, or even hybrid teaching, have made the students’ learning process precarious, even though, so far, it is difficult to quantify the damage that the withdrawal from face-to-face classes caused in the educational process. Moreover, Seffner (2021, p. 47) stated that “there is no condition for school learning in Basic Education disconnected from the surroundings of school culture and school daily life”. This same understanding becomes even more important in the case of indigenous schools.

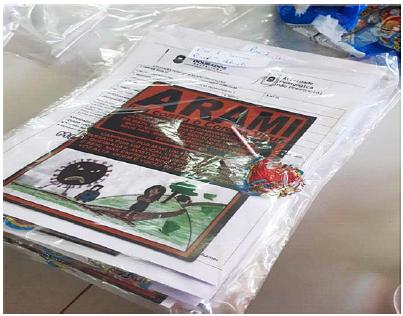

In contact with adversities of the scenario, principals, coordinators, education managers of the RID were forced to adapt to the new practices. And verifying that most indigenous families were not able to guarantee their children the following of remote/virtual classes due to the lack of access to cell phones, notebooks or internet network, the viable alternative for that moment was the organization of Non-face-toface Pedagogical Activities (APNP) in printed form (Kuatiá - paper, in the Guarani Indigenous Language), which were given to parents of children and adolescents so that they could continue school activities at home (Figure 6).

In the two indigenous villages of the RID, teachers who worked under the responsibility of the municipality of Dourados were instructed to organize themselves, so that those who belonged to the risk group would not go to work in person, while the other professionals, who were outside the risk, should work in a staggered way to meet the demands of the school, delivery and collection of APNP. In this dynamic, some teachers were diagnosed with Covid-19 and began to have another concern in addition to the educational difficulty. Those who continued to develop activities in the online format reported difficulties related to the internet signal in the indigenous territory and the lack of technological resources. Finally, difficulties in guaranteeing schooling in this period increased, and many children and adolescents were left unattended.

Other situations occurred in this context; many parents or guardians of indigenous students did not go to school to get APNP. So, the teachers and pedagogical managers took on another role, that of going out in search of children from an active search for the delivery and/or collection of the APNP. Many difficulties were observed in this process, with little or no return during the entire period of the pandemic in 2020. Often, during the active search, teachers came across children playing and in their leisure time. When inquiring about the absence of parents at school for the withdrawal of APNP, they justified that they did not go to get them because they simply believed that this time of pandemic was not the time to be worried about school, but about life.

The concern expressed by indigenous parents, in being a time to worry about life, is closely related to so many other difficulties faced by indigenous families. They went beyond educational issues, including food shortages. For this reason, schools also started to distribute staple baskets to indigenous families every two weeks. In this sense, the need to rethink the precariousness in teaching structures is perceptible and, at the same time, how the school and its agents sought attempts to overcome the deepening situations with Covid-19.

In view of the difficulties mentioned above, of how indigenous schools still repeat the teaching of urban schools, and then the difficulty of effectively putting their specificities and differences into practice, it is important to consider that the school constitutes a privileged place in which there is a constant process of deconstruction and exchange of experiences, being a space for sharing the being and traditional indigenous knowledge. Thus, there is a space for intra-, inter- and transculturality, as long as they are advocated:

[...] self-acceptance and self-recognition to achieve an internal personal or community-intracultural development, seek, above all, a self-realization of the subject. The means to achieve it is nothing more than recognition and interaction with the other, based on respect and tolerance, denying prejudices that are often disguised. (MARTINS, 2018, p. 58).

With regard to children, the need to consider them the responsibility of the entire society in which they are inserted is reaffirmed, especially when dealing with difficult times like these.

We talk about childhoods, given the existence of a plurality of realities in movement and in confrontation. Children produce everyday plots in the spaces and times of their existential geographies; therefore, they need to be understood in their social and cultural contexts. Children are intersectionally marked by their dimensions of class, ethnicity, nationality, gender and social class, that is, by various political, economic, cultural, geographic and social factors, which prevent us from thinking about them in the singular. The different childhood experiences, their ways of living and resisting in these times are questioning Early Childhood Education. (SANTOS, 2020, p. 86-87).

Considering this period of return to classes, as of October 2021, there were different understandings of safety when returning to face-to-face classes by indigenous families, such that many students remained in remote teaching. Systematized data on the return of face-to-face activities by indigenous school are listed in Table 1.

From the numbers, it was found that the Araporã Municipal Indigenous School (EMI) is the one with the highest permanence (74.7%) of students enrolled in remote education. The Tengatuí Marangatu EMI also had a significant number of students who remained in remote teaching (53%) for the 2021 school year. From these values, even in the second half of 2021 there was a lot of uncertainty regarding the return of face-to-face school activities by indigenous families.

As for students who did not attend (return) to schools, the Araporã EMI had the highest emptying in the number of students when compared to other schools, with a 9.5% dropout rate. This is a worrying factor, and it is necessary to seek information about the reasons that led these students to drop out of school.

The Agustinho and Lacuí Roque Isnarde EMI showed no students in a situation of school dropout, that is, 100% students returned to school, even though more than 50% remained in remote teaching during 2021. It should also be noted that the Agustinho EMI is the school that has the most students in face-to-face teach- ing, and for this reason it has developed a more rigorous safety protocol when compared to the other schools.

It was not possible to access information regarding the situation of students enrolled at the Polo Tengatuí Marangatu Municipal Indigenous School and at the Francisco Meireles Municipal School, so there are no records about them in Table 1.

Table 1 List of RID indigenous schools in the face-to-face and remote teaching in the 2021 school year.

| SITUATION OF ENROLLED STUDENTS ON RETURN TO FACE-TO-FACE CLASSES | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCHOOL NAME | Total of AM(1) | EP students(2) | % EP students | ER students(3) | % ER students | AA(4) | % AA | Place |

| Tengatuí- Marangatu | 681 | 232 | 34.1 | 431 | 63,3 | 18 | 2.6 | Jaguapiru Village |

| Ramão Martins | 411 | 183 | 44.5 | 204 | 49.7 | 24 | 5.8 | Jaguapiru Village |

| Araporã | 685 | 108 | 15.8 | 512 | 74.7 | 65 | 9.5 | Bororó Village |

| Agustinho | 645 | 362 | 56.1 | 283 | 43.9 | 0 | 0 | Bororó Village |

| Lacuí Roque Isnarde | 148 | 101 | 68.2 | 47 | 31.8 | 0 | 0 | Bororó Village |

| Total | 2.570 | 986 | - | 1.477 | - | 107 | - | |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on research data.

(1) AM - enrolled students

(2) EP- Face-to-face Education

(3) ER- Remote Education

(4) AA- Absent students - who did not return to face-to-face or remote classes in 2021.

Weaving considerations on school dropout, it is necessary to remember the socioeconomic, cultural and infrastructural barriers already faced by indigenous families, established before and amplified by Covid-19. Regarding access to education, Morais (2020, p. 30) describes the difficulties encountered:

The difficulties that children living in Bororó and Jaguapiru villages have to get to urban school represent one of the reasons that lead them to skip classes and consequently have their pedagogical performance impaired. Some teachers stated that some indigenous students sometimes skip classes for a week and their families do not provide any justification for their absence from school. In the research, it was possible to perceive that the reasons for school absences are related to the weather conditions of rain and cold in certain periods of the year, as well as the lack of means of transport, since most students use bicycles to go to school and often they reported - when asked - that they had skipped classes because their bikes were broken or they were being used by other family members.

The confrontations mentioned above, among many other impasses, make it difficult to implement an indigenous school that promotes intra-, inter- and transcultural education. Both indigenous children and indigenous schools play a key role in maintaining traditional indigenous knowledge, but the interaction between customs and systematized knowledge requires “the opportunity to develop skills that allow them to understand and deal with the modern world, acquiring tools that make it possible to obtain and assimilate knowledge accumulated by humanity, integrating it with the knowledge built by the ancestors” (AQUINO, 2012, p. 100).

For this reason, it is necessary that this school is attentive to the needs of its communities, promoting the construction of knowledge that favors the exchange and articulation of new alternatives for indigenous society, breaking with the current scenario of difficulties and socioeconomic inequalities present in the territories, preparing the children of today to continue the re-existence of their cultures in the future.

Final considerations

The Mitã Kuera Guarani Kaiowá territory is established by the protagonism of the way of being and living of indigenous children in the different stages of development. And even though this territory is marked by numerous socioeconomic, infrastructural, health and educational difficulties that already existed and were expanded with Covid-19, it constitutes a space-time of intra-, inter- and multicultural personal and collective constructions.

It is argued, therefore, that a school built to meet Indigenous School Education must respect the particularities of each of these children and, in this sense, reinforce the understanding of being indigenous, as well as enable the participation of indigenous communities in building a specific pedagogy that dialogues with the sociocultural and environmental characteristics of the Guarani and Kaiowá indigenous territory, whether in early childhood education or in other instances of school education, as Aquino (2012, p. 23) confirms:

[…] each people have its traditional way of teaching others, it is varied according to their ethnic group that defines their life goals since their gestation, each group has its own way of educating and caring for their children and also for the people around them, in accordance with their principles of divinity and morals received from the ñanderu.

Traditional educational practices constitute pedagogical movements that are developed throughout the growth stages of indigenous children and reveal knowledge that allow to understand the teaching-learning temporalities in the spaces of culture and identity formation, and “this knowledge is constituted with a web of cultural values and customs representing the stages of childhood human development that can support the didactic and pedagogical organization of indigenous school education” (GOMES; NASCIMENTO, 2017, p. 350).

Finally, the scenario resulting from Covid-19 has greatly increased the difficulties of ensuring good living in indigenous territories, impacting, to a lesser or greater extent, the processes of child development. Nevertheless, it is essential to recognize that indigenous children carry their own culture that is shaped in constant contact with “other cultures”, constituted among the ethnic groups circulating in their territories. Establishing dialogue between these cultures in formal education spaces is a promising alternative for recognizing differences, accepting diversity and valuing identities

REFERENCES

ANJOS, Cleriston Izidro dos; FRANCISCO, Deise Juliana. Educação Infantil e tecnologias digitais: reflexões em tempos de pandemia. Zero-a-Seis, Florianópolis, v. 23, n. Especial, p. 125-146, jan./jan., 2021. Disponível em: https://doi. org/10.5007/1980-4512.2021.e7900.7. Acesso em: 18 nov. 2020. [ Links ]

AQUINO, Elda Vasques. Educação escolar indígena e os processos próprios de aprendizagens: espaços de inter-relação de conhecimentos na infância Guarani/Kaiowá, antes da escola, na comunidade indígena de Amambai, Amambai - MS. 2012.118 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Católica Dom Bosco, Campo Grande, MT, 2012. Disponível em: https://site.ucdb.br/ public/md-dissertacoes/10911-elda-vasquesaquino.pdf. Acesso em: 18 nov. 2020. [ Links ]

BHABHA, Homi. O local da cultura. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 2010. [ Links ]

BRAND, Antonio. Educação Escolar e sustentabilidade indígena: possibilidades e desafios. Ciência e Cultura [online], São Paulo, v. 60, n. 4, p. 25-28, out. 2008. Disponível em: http:// cienciaecultura.bvs.br/scielo.php?script=sci_artte xt&pid=S0009-67252008000400012. Acesso em: 20 nov. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Casa Civil. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Brasília, DF, 1988. Disponível em: http:// www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/ constituicao.htm. Acesso em: 18 nov. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Comitê de Educação Escolar Indígena. Diretrizes para a Política Nacional de Educação Escolar. 2. ed. Brasília, DF: MEC/SEF/DPEF, 1994. (Cadernos de Educação Básica. Série Institucional; 2). Disponível em: file:///C:/Users/Usuario/ Downloads/F3D00026.pdf. Acesso em: 20 out 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Casa Civil. Lei nº 9.836, de 23 de setembro de 1999. Acrescenta dispositivos à Lei no 8.080, de 19 de setembro de 1990, que “dispõe sobre as condições para a promoção, proteção e recuperação da saúde, a organização e o funcionamento dos serviços correspondentes e dá outras providências”, instituindo o Subsistema de Atenção à Saúde Indígena. Brasília, DF, 1999. Disponível em: http:// www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9836.htm. Acesso em: 9 out. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Presidência da República. Casa Civil. Decreto nº 6.861, de 27 de maio de 2009. Dispõe sobre a Educação Escolar Indígena, define sua organização em territórios etnoeducacionais, e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF, 2009. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ Ato2007-2010/2009/Decreto/D6861.htm. Acesso em: 20 out. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Câmara de Ensino Básico. Parecer CNE/CEB nº 13/2012, de 10 de maio de 2012. Brasília, DF, 2012a. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_ docman&view=download&alias=10806pceb013-12-pdf&category_slug=maio-2012pdf&Itemid=30192. Acesso em: 20 out 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Câmara de Educação Básica. Resolução CNE/CEB nº 5, de 22 de junho de 2012. Define Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Educação Escolar Indígena na Educação Básica. Brasília, DF, 2012b. Disponível em: http:// portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_ docman&view=download&alias=11074rceb005-12-pdf&category_slug=junho-2012pdf&Itemid=30192. Acesso em: 25 out 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Conselho Plena. Parecer CNE/CP nº 6, de 2 de abril de 2014. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Formação de Professores Indígenas. Brasília, DF, 2014. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_ docman&view=download&alias=15619-pcp00614&category_slug=maio-2014-pdf&Itemid=30192. Acesso em: 25 out 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Conselho Nacional de Educação. Conselho Pleno. Resolução CNE/CP nº 1, de 7 de janeiro de 2015. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para a Formação de Professores Indígenas em cursos de Educação Superior e de Ensino Médio e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF, 2015. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_ docman&view=download&alias=16870-res-cnecp-001-07012015&category_slug=janeiro-2015pdf&Itemid=30192. Acesso em: 25 out. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum Curricular (BNCC). Brasília, DF, 2018. Disponível em: http://basenacionalcomum.mec. gov.br/images/BNCC_EI_EF_110518_versaofinal_ site.pdf. Acesso em: 9 out. 2021. [ Links ]

CASTRO, Eduardo Viveiros de. Os involuntários da pátria: reprodução de aula pública realizada durante o ato Abril Indígena, Cinelândia, Rio de Janeiro 20/04/2016. ARACÊ - Direitos Humanos em Revista, São Paulo, ano 4, n. 5, p. 187-193, 2017. Disponível em: https://edisciplinas.usp. br/pluginfile.php/4865765/mod_resource/ content/1/140-257-1-SM.pdf. Acesso em: 9 out. 2021. [ Links ]

DOURADOS. Prefeitura Municipal de Dourados. Resolução nº 51, de 22 de maio de 2020. Dispõe sobre a regulamentação das atividades pedagógicas não presenciais. Diário Oficial do Município de Dourados: ano XXII, n. 5.169, p. 1, Suplementar, Dourados, MS, 22 maio 2020. Disponível em: https://do.dourados.ms.gov.br/wp-content/ uploads/2020/05/22-05-2020-SUPL.pdf. Acesso em: 22 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

FERNANDES, Bernardo Mançano. Entrando nos territórios do Território. In: PAULINO, Eliane Tomiasi; FABRINI, João Edmilson (org.). Campesinato e território em disputas. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2008. p. 373-302. Disponível em: http://docs.fct.unesp.br/docentes/geo/bernardo/BIBLIOGR AFIA%20DISCIPLINAS%20POSGRADUACAO/BERNARDO%20MANCANO%20FERNANDES/campesinato.pdf. Acesso em: 23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

FOLHA DE DOURADOS. Mapa da Reserva Indígena de Dourados. 2012. Disponível em: https:// www.folhadedourados.com.br/wp-content/ uploads/2021/07/x-113.jpg. Acesso em: 11 fev. 2022. [ Links ]

GALLOIS, Dominique Tilkin. Patrimônio cultural imaterial e povos indígenas: exemplos no Amapá e Norte do Pará. São Paulo: IEPÉ, 2006. Disponível em: https://www.institutoiepe.org.br/media/ livros/livro_patrimonio_cultural_imaterial_e_ povos_indigenas-baixa_resolucao.pdf. Acesso em: 23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

GOMES, João Carlos; NASCIMENTO, Adir Casaro. A pedagogia cultural da infância indígena Guarani e Kaiowá. Revista de Educação Pública, Cuiabá, v. 26, n. 62/1, p. 335-354, 2017. Disponível em: https://periodicoscientificos.ufmt.br/ojs/index. php/educacaopublica/article/view/4998. Acesso em: 23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

GUTIERREZ, José Paulo. A circularidade das crianças Kaiowá na Aldeia Laranjeira Ñanderu, Rio Brilhante, Mato Grosso do Sul. 2016. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Católica Dom Bosco, Campo Grande, MT, 2016. Disponível em: https://site.ucdb.br/public/ md-dissertacoes/22853-jose-paulo-gutierrezcompressed.pdf. Acesso em: 20 nov. 2020. [ Links ]

JOÃO, Izaque. Jakaira reko nheypyrũ marangatu mborahéi: origem e fundamentos do canto ritual jerosy puku entre os kaiowá de Panambi, Panambizinho e Sucuri’y, Mato Grosso do Sul. 2011. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) - Faculdade de Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (UFGD), Dourados, MS, 2011. Disponível em: https://www.ppghufgd.com/wp-content/ uploads/2017/06/Izaque-Jo%C3%A3o.pdf. Acesso em: 20 nov. 2020. [ Links ]

KNAPP, Cássio. Educação Escolar Indígena: e ensino bilíngue e os Guarani e Kaiowá. Curitiba: CRV, 2020. [ Links ]

KRAMER, Sônia. A infância e sua singularidade. In: BEAUCHAMP, Jeanete; PAGEL, Sandra Denise; NASCIMENTO, Aricélia Ribeiro do. Ensino fundamental de nove anos: orientações para a inclusão da criança de seis anos de idade. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Educação/Secretaria de Educação Básica, 2007. p. 13-24. Disponível em: http:// portal.mec.gov.br/seb/arquivos/pdf/Ensfund/ensifund9anobasefinal.pdf. Acesso em: 9 out. 2021 [ Links ]

LESCANO, Claudemiro Pereira. Tavyterã Reko Rokyta: os pilares da educação Guarani Kaiowá nos processos próprios de ensino e aprendizagem. 2016. 108 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Católica Dom Bosco, Campo Grande, 2016. Disponível em: https://silo.tips/download/ claudemiro-pereira-lescano-tavytera-reko-rokytaos-pilares-da-educaao-guarani-ka. Acesso em: 23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

MACHADO, Micheli Alves. Educação Infantil: criança Guarani e Kaiowá da Reserva Indígena de Dourados. 2016. 143 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (UFGD), Dourados, MS, 2016. Disponível em: https://repositorio.ufgd.edu.br/jspui/ handle/prefix/1346. Acesso em: 20 nov. 2020. [ Links ]

MARTINS, Daniel Valério. Conceitos de contatos culturais e de intervenção social que incidem na sociedade latinoamericana do século XXI: intra, multi, inter, trans e sobreculturalidade. Pluri, São Paulo, v. 1, n. 1, p. 55-66, jul./dez. 2018. Disponível em: http://repositorio.cruzeirodosulvirtual.com. br/index.php/pluri/article/download/33/52/. Acesso em: 20 nov. 2020. [ Links ]

MORAIS, Clotildes Martins. Crianças kaiowá e guarani em uma escola urbana da cidade de Dourados/MS. 2020, 135 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Antropologia) - Faculdade de Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (UFGD), Dourados, MS, 2020. Disponível em: http:// repositorio.ufgd.edu.br/jspui/handle/prefix/4128. Acesso em: 9 out. 2021. [ Links ]

MOTA, Juliana Grasiéli Bueno. Territórios e territorialidades Guarani e Kaiowa: da territorialização precária na reserva indígena de Dourados à multiterritorialidade. 2011. 406 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Geografia) - Faculdade de Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal da Grande Dourados (UFGD), Dourados, MS, 2011. Disponível em: http://repositorio.ufgd.edu.br/jspui/handle/ prefix/375. Acesso em: 14 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

NOAL, Mirian Lange. As crianças Guarani\Kaiowá: o mita reko na aldeia Pirakua/MS. 2006. 386 p. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas, SP, 2006. [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, Roberto Cardoso de. O trabalho do antropólogo: olhar, ouvir, escrever. Revista de Antropologia, v. 39, n. 1, p. 13-37, 1996. Disponível em: http://www2.fct.unesp.br/docentes/geo/ necio_turra/MINI%20CURSO%20RAFAEL%20ESTRADA/TrabalhodoAntropologo.pdf. Acesso em: 20 nov. 2020. [ Links ]

ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS PARA A EDUCAÇÃO, A CIÊNCIA E A CULTURA (UNESCO). Declaração Universal sobre a Diversidade Cultural. 2002. Disponível em: https://www.oas.org/dil/ port/2001%20Declara%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20 Universal%20sobre%20a%20Diversidade%20 Cultural%20da%20UNESCO.pdf. Acesso em: 9 out. 2021. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Boaventura de Sousa. A cruel pedagogia do vírus. Coimbra: Edições Almedina S.A, 2020. Disponível em: https://www.abennacional.org. br/site/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Livro_ Boaventura.pdf. Acesso em: 9 out. 2021. [ Links ]

SEFFNER, Fernando. A escolarização pública e o imprevisto mais do que previsto. Revista Interdisciplinar em Educação e Territorialidade - RIET, Dourados, MS, v. 2, n.2, p. 38-63, 2021. Disponível em: https://ojs.ufgd.edu.br/index.php/ riet/article/view/14475. Acesso em: 11 fev. 2022. [ Links ]

2To better present the concept of time and space discussed here, we rely on Mota (2011, p. 25): “[...] we consider that if there is a spatiality produced by people who move around the world, tracing their territorialities, this coming and going is marked by time, doing and undoing itself in different ways, since time is not made in the same way in all societies. [...] In this context, temporalities are not experienced in the same way in all societies, and that not all of them have, in control of the clock and calendar, the same ways of perceiving the reality in which they live, have lived or will be able to live, considering that the space-time configuration is correlated and interdependent with each other.”

3Literature recognizes the existence of three culturally and linguistically related ethnic groups in Brazil: the Guarani Mbyá (who mostly settle from Rio Grande do Sul, traveling along the Brazilian coast to the state of Espírito Santo), the Guarani Kaiowá and the Guarani Ñandéva or Nhandéva (living mainly in Mato Grosso do Sul). The latter, however, are only called Kaiowá or Guarani, so, from then on, this text will recognize the self-denomination of these ethnic groups.

4Despite the existence of a fruitful debate on the adoption of the concept of confinement by suggesting a notion of cultural immobility, here we support the report by Brand (2008) to demonstrate the vast decrease in the tekoha guassu, that is, the ancestral territory in which the Guarani and Kaiowá lived, respecting the nande reko, “our way of living.

Received: April 10, 2022; Accepted: July 11, 2022

texto en

texto en