Introduction

Listening to stories is a practice that gives us great pleasure from young ages to adulthood. We can easily remember times when we heard stories, whether told by our grandparents, family, friends or teachers. The act of listening is part of the essence of the human being, as it has been present since the beginning of humanity, and thus it often contributes to their human and reading formation as well as being a way of feeling certain emotions, living art, experiencing conflicts and to amaze oneself. (ABRAMOVICH, 2009).

Thereupon, considering the importance of listening to stories, the relevance of telling them is perceptible, and as storytelling is an art (SILVA, 1986) it is necessary that telling a story is not done at random, but in a prepared and studied way so that the experience is significant for both the teller and the listener.

Therefore, the topic of this paper emerged from the experience of researchers at the Center for Studies in Reading and Literature for Children and Youth (CELLIJ), and in an internship at the Wiclife elementary school, in Ashland, USA, where there was a close contact with Children’s Literature and the practice of storytelling in the Storytelling Time - Hora do Conto - project and in the activities of the school library of that institution.

This research is characterized as an experience report. In this article, besides to the theoretical concepts that support our studies, we will present two reports that contribute and enrich the discussion to be addressed.

In the first stage of the investigation, we carried out a bibliographic research which, according to Fonseca (2002, p. 31-32), is a

[...] survey of theoretical references already analyzed, and published by written and electronic means, such as books, scientific articles, web site pages. Any scientific work begins with a bibliographic research, which allows the researcher to know what has already been studied on the subject.

Next, we analyze some experiences lived by the researchers, and we chose two that successfully represent the subjects will be dealt in this study.

At first, in this space of the University, children from different classes of public and private schools come to CELLIJ throughout the year to hear stories and have contact with books at Children’s Library of Prudente (BIP). In the Wiclife school library, activities with the literary text are in charge of the librarian, one of the authors of this paper.

Both institutions, through those responsible for the dissemination of children’s literature among children, assume the importance of hearing stories, and the relevance of telling them.

Keeping that in mind, we sought to report the meaning of planning actions for the act of telling stories, bringing some steps and suggestions for this preparation, based theoretically on Silva (1986), Sisto and Motoyama (2016), Abramovich (2009), Busatto (2003) and others, highlighting the differences between reading aloud and storytelling (BAJARD, 1994).

Beyond that, this article also presents two practical examples that aim to highlight the experiences of the entire planning and execution process of a storytelling cycle carried out at the Center for Studies in Reading and Children’s and Youth Literature “Maria Betty Coelho Silva” (CELLIJ), located in State University of São Paulo “Júlio de Mesquisa Filho” in Presidente Prudente and at the Wiclife school.

To this end, from reading this text, it will be possible to have more knowledge of what storytelling really is, its importance, and why this practice needs to remain alive, be prepared and cared for as well as carefully studied by authors who discuss this millennial art.

Plan to Tell: The importance of Storytelling

The art of narrating and telling stories is not a new practice, on the contrary, it is one of the most remote activities of humanity, “since the emergence of ancient civilizations, individuals have sought a way to express themselves and communicate and, hence perpetuate the collective memory of its people” (SILVA, 2014, p. 30). This quest to leave a mark on human history led men to look for a way to communicate, and in this way narrative became part of peoples’ culture.

Upon discovering language, whether verbal, written, imagery or symbolic, human beings began to relate, and therefore assumed their natural condition of being social, which is developed through the interaction with other subjects (SILVA, 2014).

Mankind used to communicate in different ways, even in prehistory the narrative was present, and it has been found on the walls of caves, reporting the daily life of that people in cave paintings, “this form of communication has been changing, evolving, but the the need to pass on to the next generations the culture of the peoples, new pieces of information, reports of lived experiences has remained, and with it the act of telling stories.” (ZOCOLARO; DONÁ; SOUZA 2020, p. 1639).

From the relationship with other peoples and cultures, human beings began to transmit thier own culture, values, to share stories, experiences, and in this way start a tradition that enriches and fullfills our humanity, the tradition of storytelling.

Through traditional storytellers’ orality, whole societies perpetuated and transmitted costumes, values and social organization to future generations. Oral stories enlarged human consciousness, allowing individuals to know thw universe and themselves. (SILVA, 2014, p. 20).

As societies evolved, written language was created and spread, standing out from oral tradition.

The oral tradition, which for a long time held a prominent position, began to lose ground to writing, which has gaiend prestige since its birth, once it is the one that best fullfills the need of modern people (SILVA, 2014, p. 29).

However, the author Valéria Silva (2014) tells us that by putting aside the oral tradition, mankind also moved away from what is its essence, since it is in the affirmation that people are primerly built , that they relate to and identify themselves. Moreover, despite the importance given to written language, the practice of storytelling, according to Celso Sisto (2012) reappears and gains different grounds and prestige.

Societies that did not develop writing, or took longer to enter the literate world, according to Silva (2014), present oral language as the major way of communication, and thus,

In these cultures, traditional storytellers, represented by the elderly, griots, craftsmen, conselours and other members of community, when telling oral stories, fulfil the functions of transmitters and receivers of such stories (SILVA, 2014, p. 31).

In this perspective, oral narrative has been manifesting its presence and importance since the beginning of communication, and with it, storytellers have become essential subjects in society, so that this practice has reached the present day, proving to be still very important. relevant even with the advancement of written language, technology and society.

From small family or population centers to library and theater rooms, the storyteller remained the order of the day. Some wanted it forgotten, others believed in the solidary force of those who bring people together to enchant through the word. More than gathering people, the storyteller has become mandatory in the promotion of reading as well as in the rescue of playfulness and fantasy. Instead of vanishing in time, the storyteller has multiplied. (SISTO, 2012, p. 49).

Hence, it was through the voice of storytellers that the tales of oral literature were perpetuated in humanity, until historians, literati and others went in search of listening and recording, transforming such narratives also into written language (BUSATTO, 2003).

The written language then ensured that these tales reached the present day, but contrary to what some believed, such as Benjamin (1998) who stated that the art of narration was on its way to an end, it did not erase the strength of oral narrative, which for being part of the human essence, continued to exist, and makes itself present through the voice of storytellers.

There was a time when men, women and children gathered to tell and hear stories of witches, fairies, heroes, villains, talking animals and many other characters. This time still exists. The art of storytelling never ended even though many would bet it has no room in the contemporary world, marked by sophisticated technology in communication and a frenetic pace in modern families’ lives. Mankind, however, did not abandoned its human condition, and the need of telling and hear stories is undoubtedly, part of its nature. (BARBOZA, 2008, p.48, apud SILVA, 2014, p. 50-51).

In this context, understanding that the act of telling stories is part of the essence of the human being, listening to stories is also inserted in their humanity and therefore is very important for the development of any person.

If diving into this universe is fascinating for us adults, who forgot to get inebriated by magic, imagine for a child, who deliberately builds up a world where everything is possible. By telling him/her a story, we would be providing a rare fulfilment, as we would collaborate to broaden and enrich his/her universe. (BUSATTO, 2003, p.12).

Thus, offering children moments to hear stories is giving them the opportunity to enjoy magic, fantastic possibilities, expanding their experiences. Fanny Abramovich (2009) claims that it is from the story that children will discover new places, other times, other ways of acting and being. Besides, for the author

By hearing stories one can (also) feel important emotions such as sadness, anger, irritation, well-being, fear, joy, dread, insecurity, tranquility, and many others, experiencing everything that the narratives provoke in those who hear them [...] (ABRAMOVICH, 2009, p.17).

In this way, having contact with the stories, for the child, is having contact with all these feelings, which are so human that they end up humanizing us, it is discovering possible challenges to be solved, it is living the climax together with the characters.

Given the above, recognizing the importance of stories, how they have echoed in our humanity since we were little, opening ourselves to a world of magic, human pain and forming ourselves in the real world, it is important to look for activities that offer these moments of telling for children, because we want all of them to have access to the most legitimate storytelling, in which, based on the storyteller’s preparation, the listener can be taken to another level, to the most beautiful human sensations.

That is why the art of storytelling involves technique, preparation, knowledge of the story, use of voice, gestures, body and audience:

storytelling involves art, aesthetics and, above all, it makes use of performance with all its characteristics, among them, gestures, body expression, voice, the choice of a good plot and appropriate techniques so that the stories are transmitted and appreciated by listeners (SILVA, 2014, p. 21).

Thus, in order to awaken and open the children’s imagination through the telling and use of literary texts, it is necessary that the story is well told, that it is prepared as well.

It is not only about telling it: it is about doing it well, in a beautiful way, with a crafted language, to affect the other with a good glimpse of what is not easily found on a daily basis with a balanced aesthetic appeal. Only then we can say that our commitment is also to literature. (SISTO; MOTOYAMA, 2016, p. 112).

By understanding the act of telling, we know, through narrative, to captivate the audience in an easier way, to make them feel the tale, to travel along with the story. When we don’t prepare the story, there’s a great chance that this won’t happen, and thus, give room to a narrative that doesn’t matter.

Nothing is more unpleasant than a dull narrative, one that goes along twists, giving room for yawning, deconcentrating and makes the mind wander into places away from those to be suggested by the text (BUSATTO, 2003, p. 65).

As a result, there are several factors to think about when preparing the storytelling, so that it is captivating and legitimate, that it has a commitment to art and literature, and promote it to children, through the use of voice, gestures, performance. , sensations and enchantments that the narratives convey.

Thus, we will discuss below about this necessary planning to tell stories.

Storytelling Planning

Abramovich (2009) shows us that to tell any story it is good to know how it is done, understanding that storytelling is an art, it is necessary that whoever is telling it is prepared, knows the different techniques for each audience, knows how to create the atmosphere, engage with the story, as it is the telling “that balances what is heard with what is felt [...]” (ABRAMOVICH, 2009, p. 18).

With this in mind, it is necessary to prepare the telling carefully, thinking about several aspects. One of them is the choice of the story that will be told. Silva (1986) states that to choose the narrative it is necessary to take into account factors such as the literariness of the work, in addition to rethinking whether it is interesting to listeners, depending on their age group, the place where the narrative will be told, if it is an outdoor space, an indoor and even if they are listeners of different ages or with very different realities. Thus, this author claims that “before telling a story, we need to know if it is an interesting and well-crafted subject. If it is original, it demonstrates a high level of imagination and is able to please children.” (SILVA, 1986, p. 14)

In order to choose the story, is it also important to take into consideration the connection between the storyteller and the text. Once there is no such connection, storytelling will end up being just a way of transmitting pieces of information (BUSATTO, 2003).

Before raising the awareness of listeners, the story must sensitize the teller. The way we see the story is the same of which it is seen by the other. If we take it as distraction or entertainment, it will sound just like this. However, if we believe it can be a light to our way, this is how it will be taken.(BUSATTO, 2003, p. 47 - 48).

Hence, according to the authors concerned, it is important that the storyteller likes what will be narrated, and understands the narrative, “It’s no use dedicating yourself to the text, if you don’t understand its meaning and intention” (BUSATTO, 2003, p. 60). If the teller does not feel close to the story, it is better not to tell it at all, as he/she will be transmitting along with the story his/her anxieties regarding it and the way of narrating. “We cannot hope for a story to involve people if we are not willing to be with it, narrating every detail with its own intention, after all, words can contain much more than their strict meaning” (BUSATTO, 2003) , p. 62).

Thus, after choosing the story, it is necessary to study it, which for Silva (1986) is “first of all, having fun with it, capturing the message that is implicit in it and then, after some readings, identifying the its essential elements” (SILVA, 1986, p. 21) so that, in this way, the teller becomes familiar with it, perceives the moments to rise or fall the intonation and control the speed of the narrative, to use the gestures, the body, and where the story allows new elements to be added, such as objects and techniques. “Studying the story is also choosing the best way or the most appropriate form to present it” (SILVA, 1986, p. 31).

Another part of preparing for storytelling is to reflect on the way and the means to tell, checking the technique that will be used, as well as choosing which external elements will be added. At this moment, according to Sisto and Motoyama (2016), the storyteller uses his sensitivity to understand if in the story there is a possibility to use external resources, or if the simple narrative is better, which, for Silva (1986, p. 31), it is one that “does not require any accessories and is processed through the narrator’s voice, his/her posture. The storyteller, in turn, with his/her hands free, concentrates all the strength on body expression”.

In this sense, “external resources are objects, costumes, instruments, scenarios, projections that help the storyteller to enrich his performance by interacting with the listeners, providing them with a differentiated aesthetic experience” (SISTO; MOTOYAMA, 2016, p. 117).

Nevertheless, to choose such resources, the teller must dialogue with the story to know which media “it accepts”, because if this is neglected, the exaggerated elements, instead of adding to a better experience with the story, will divert the audience’s attention, and jeopardize the narrative. That is why it is very important to study the story, so that we understand the necessary elements, and the technique according to what it “requires”, that is, the narrative offers “clues” that help us choose the best resource and/or technique.

In addition to reflecting on external resources, Sisto and Motoyama (2016) talk about another type of resource that the storyteller should be aware of: internal resources. An example of this would be diving into the story, identifying with it, getting emotional, rehearsing it, repeating it, getting into the narrative and thereby preparing your story, discovering the essential external resources that leave the teller and listeners calm in the reception of the oral text. “It is important to be aware that if the teller is not well prepared, the use of external resources will be insufficient” (SISTO; MOTOYAMA, 2016, p. 121). Thus, the success of the narrative depends deeply on the relationship of the storyteller’s commitment to the rehearsal and study of history, as well as to the techniques and resources chosen.

Another relevant factor is to create the environment for storytelling, after choosing the narrative, studying it, thinking about the resources and rehearsing it, it is important that the teller creates an engaging magic while he is telling, and that thus captivates attention. from the beginning to the end of the activity, making each action in the story add more meaning to the story, and make it even more interesting.

[...] It is good that the one who tells the story is able to create a touching and captivating environment, enchantment... knows how to control the pace, makes breaks, allows time for children´s imagination builds scenarios, depicts monsters, creates dragons, breaks into houses, get the princess dressed, think of the priest´s face, feels the horse galloping, imagine the crooks’ appearance and so on... (ABRAMOVICH, 2009, p. 21).

It is at this moment that all the preparation previously made will be put into practice, the storyteller will use the chosen technique, the lines, the movements, the songs, all prepared beforehand. It is in the act of telling the story, of captivating the audience, of vividly passing on the chosen narrative, and “for the narrative to be alive, you [the teller??] must also be alive. Perceive each passage of the text, feel it as if it were part of you, as if those experiences were also yours” (BUSATTO, 2003, p. 62).

Given the above, it is understandable the importance of the audience, it is for them that the story is prepared, so that they can experience together with the storyteller the pleasurable moment of telling a story and thus be closer to this art. It is the listeners who make stories happen, without them, any story is still just an idea, subject to the unpredictability of the audience. Thus, “for a storyteller, the story only comes true, it only becomes reality when it is shared with the listeners. Before that, it is just a hypothesis and is almost entirely in the realm of possibilities” (SISTO; MOTOYAMA, 2016, p. 116).

As the audience is indispensable for storytelling, it is important to think about the storyteller’s relationship with his listeners, look them in the eye, respect the time to imagine the story, this interaction with the audience is one of the characteristics that differentiates “Reading” from “Telling”. Since unlike reading the story aloud,

Telling requires a direct connection with the audience which, in this case, comes from internal resources such as emotions, affections, personal experiences, and the external ones like gestures, intonation as well as the narrator’s body expression (SILVA, 2014, p. 55).

Bajard (1994) tells us more about this difference. For him, “Reading” is a personal practice, “saying” is reading aloud transmitting the text to someone, and “telling” is free, not tied to the text, allowing adaptations. Thus, for the author, telling is not just saying (reading the text aloud); in saying it is only necessary to convey the text as it is written. Both saying and telling require preparation, but when telling the text, the storyteller can reformulate it according to the needs of the moment, giving rise to spontaneity, to the narrator’s creativity, “the storyteller knows how to fill his plot with contributions that stem from spectator interventions” (BAJARD, 1994, p. 105). These adaptations will only be possible by knowing the text and the possibilities allowed by it.

Before the text, the reader is not alone; the identification with the characters takes place in his/her innermost being. With regards to the storyteller, this identification is carried out amongst others and does not refer to the private field, but to the social one. Being able to assume the words of a character, translate the ‘ha ha ha’ on a written text into sounds requires that the storyteller plays the character in front of others (BAJARD, 1994, p. 95).

Matos (2005) also brings us the difference between reading aloud and storytelling.

[...] the art of the storyteller involver body expression, improvisation, interpretation, interaction with the listeners. The teller, as we have seen, recreates the story with his/her audience as he/she tells it. The reader, int turn, lends his/ her voice to the text. He/she can vocal resources so that reading become more engaging for the listener, but does not recreate the text, neither improvise by using audience stimuli. (MATOS, 2005, p. 9).

In storytelling, still according to Matos (2005), what is wanted is this immediate interaction with the listener, the audience’s reactions are essential to develop the narrative and, consequently, help in the understanding of the oral text.

In this way, it is possible to understand how telling a story involves more than the simple transmission of a narrative, and how it is more than reading a book aloud to a child. Telling is free, with the use of hands, gestures, with the story in the head, and can be adapted according to the audience’s response, the story that is alive, because at each moment, without losing its essence, it can change from shape depending on what the audience’s eyes ask for.

Busatto (2003 states that telling stories is forgetting the pedagogical fora while, and going in search of an inheritance left by our ancestors, and which is often forgotten, even though it is part of our being.

Therefore, looking through the trajectory of oral narrative, it is possible to perceive the importance of storytelling over time and in the present day. It is important to offer audiences of all ages, but especially children, moments to listen to stories, to calm down, and to let the imagination work from the oral narrative, from the performance of the storyteller. As it is a very rich practice, storytelling cannot be lost, and cannot be prepared in any way, it requires care and preparation for this moment.

To exemplify more clearly the difference between saying and telling, we will explore an activity elaborated with the proffering of a book in the Wiclife school library and then, a moment of storytelling at CELLIJ, located at Universidade Estadual Paulista de Presidente Prudente that is dedicated to the study, preparation and storytelling.

Telling an image text: reflections and discussions

The strong presence of images in children’s literature books can lead to a false perception that every illustration has a decorative or utilitarian character, serving as a support for the verbal text. However, there is a range of works that is characterized not only by the presence of image and text, but by the significant load arising from this mutual relationship, in which the two elements are indispensable for the production of meaning. This is the case of the illustrated book, whose text emerges from the reading of words and images, which maintain an interrelationship that goes beyond the mere co-presence of these languages. In this type of work, according to Nikolajeva and Scott (2011, p. 15), “[the] verbal text has its gaps and so does the visual. Words and pictures can fill in each other’s gaps, fully or partially.” Thus, both verbal and visual text can be evocative or independent of each other.

The illustrated books correspond, therefore, to hybrid works composed of two distinct languages that sometimes complement each other, sometimes contradict each other, thus giving rise to a third text, arising from the interrelation between words and images. However, it is common for picture books to be treated as “an integral part of children’s fiction, being analyzed by critics with a [uniquely] literary approach, discussing themes, issues, ideology or gender structure”, so that either “[. ..] neglect the visual aspect or treat images as gender structures” (NIKOLAJEVA; SCOTT, 2011, p. 17).

According to illustrator Celia Berridge, what makes picture books receive “such a synthetic treatment in reviews is not because they are considered deficient from a serious evaluation, but because they are all considered the least important part of the book’s universe” (1981 apud). HUNT, 2010, p. 233).

An important landmark in the establishment of the picture book in the United States is the work Onde vivem os monstros (1963), written and illustrated by Maurice Sendak. This book “[...] introduces a new conception of image, which allows the representation of the child’s unconsciousness” (LINDEN, 2011, p. 17). Such representation takes place from the frames of the pages, which increase or decrease in size, depending on what Alex, the protagonist, feels and experiences.

A few years later, in Brazil, in 1969, Ziraldo published Flicts and contributed significantly to the inauguration of the contemporary illustrated book in the country. In this work, the author, through the articulation between words and images, gives life to an unusual character: a color. Not just any color, but a “very rare and very sad / that was called Flicts”, and that was trying hard to find its place. In this way, as an author-illustrator, Ziraldo revolutionized the hierarchy of text over illustration, expanding the space of relevance of images. This revolution, according to Vasques (2008, p. 02), “was not limited to illustration, but to the incorporation of illustration and form as significant texts, indispensable to the understanding of the work”.

After this period, as mentioned before, an important number of authors, illustrators and author-illustrators emerged and were capable of producing children’s books with images that articulate in the most different ways with the verbal text, expanding it or modifying its meaning, thus creating , new texts composed of words and images, that is, illustrated books.

However, in general, there are few studies that more specifically address the images and the image-text relationships in these works. At most, the imagery aspect of the works is mentioned or observed through a purely aesthetic perspective, without any analysis of its articulation with the verbal text. Another aspect that goes unnoticed by research and analysis is the paratextual elements of the works, namely: cover, title, guards, title page, among others (GENETTE, 2018). The materiality of books is a factor that still goes unnoticed, but that has shown increasing importance with regard to the production and reception of contemporary picture books. Thus, we are also interested in showing readers the meanings of paratexts, which have come to present different functions in this type of work over the years.

After the discussion about some gaps regarding reading activities focusing on the articulations between words, images and paratexts, it is worth highlighting another pressing issue, in our view: there is an object that has been undergoing fundamental changes since the 1960s., but which, nevertheless, seems to continue to be read with the same gaze. Thus, it can be conjectured that such carelessness with the visual aspect is related to the enormous predominance of studies focused on the analysis of verbal literary text, restricting the theoretical framework about illustrations in the context of children’s literature. In general, this helps to understand the reasons why adults lose the ability to read illustrated books, even ignoring the whole and seeing illustrations as mere decorative elements (NIKOLAJEVA; SCOTT, 2011). In many cases, even illustrations are not only neglected, but also excluded from the teaching-learning process for children. We believe it is essential, therefore, that this audience is led to exercise the ability to read images so that they can choose, recommend and work with illustrated books with children. In this case, it is a process of “literacy” of image reading, from the paratexts of books.

From these theoretical assumptions, an important work developed by the Wiclife school librarian is the utterance and all the discussions that permeate the reading aloud activities at school. In this article we chose to show how children can be interested in so many languages t hat are impregnated in an illustrated book. Sessions at the Ashland School Library take place in two ways: the first assists the teacher with their curriculum content through research and book exhibitions, and the second occurs weekly with storytelling, author visits, reading aloud and/or activities for discussion and book removal, this one is open. Students can attend the library freely, without scheduling appointments, for handing and picking up books and other reading materials.

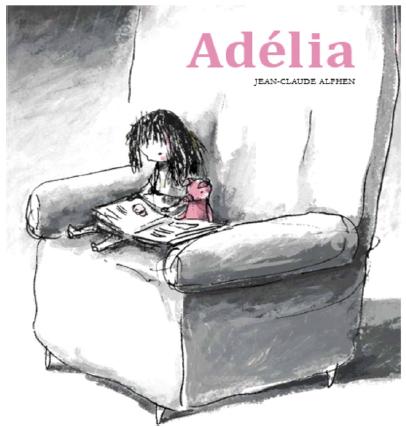

A few years ago a partnership between Wiclife and CELLIJ was established and in this sense, many national and foreign books were shared. The librarian is fluent in the Portuguese language and values working with all cultures. Thus, below we will discuss a reading activity, exemplifying the work done by Stevenson with the book Adélia de Asphen (2016).

On the day of the utterance, the children of the 2nd. Grade of Junior High School arrived at the library and the librarian had been waiting for them with a large screen set up in front of them, a mat with cushions so that the students could sit comfortably to listen and discuss the utterance/reading aloud.

The librarian started the activity by presenting the book and its the cover, because it is, along with the title, the first contact with the work, “which can seduce or not to read, attracting attention and inviting the reader to enter the universe that the book comprises” (RAMOS; PANOZZO, 2011, p. 76).

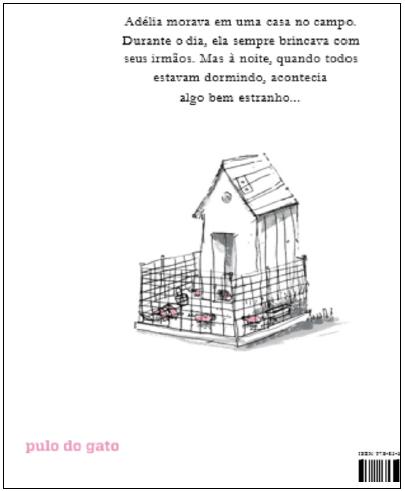

The name of the book appears in pink font. Below it, a little girl and a little pink pig are reading a book, sitting in a large armchair. The title determines the work, however, its combination with the images of characters generates a “confusion” and “ambiguity”. As from the image and the title we can think: is Adelia the girl or the pig?

From this questioning the librarian started to explore the back cover, which still does not answer the initial question and the ambiguity is reinforced by the color of the little pigs. There is already a perspective on the reality of the animal/pig in the text. But the question remains: Who is Adelia? At this point the librarian wanted to know if any student would make the relationship between the color of the little pigs and the title of the story.

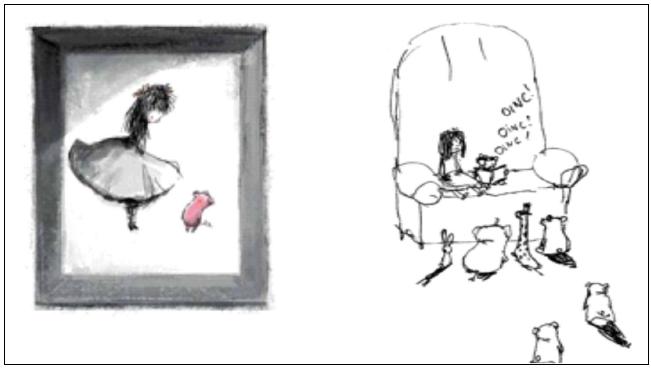

With the mystery in the air, Stevenson sets out to explore the endpapers. The function of the endpapers is to present an introductory scene to the narrative, or to sum up the story and even influence the interpretation (NIKOLAJEVA; SCOTT, 2011). In the initial cover sheet of the work Adélia, we find only the girl reading a book, while the final cover complements with the main character, the pig and the two of them reading a book.

The librarian then, through questioning, encourages the children to establish relationships between the initial endpaper in which the girl is alone and the final one in which both the girl and the pig silently read a book. However, listeners still cannot answer the initial question, who is Adélia?

He then proceeds to explore the title pages, which begin to indicate that the pig is not a “common” animal, the image of the girl standing with the pig allows several interpretations and even deconstructs the hypothesis of being, for example, a toy. The final title page enlarges the cover image, because now the girl and the pig are on the sofa and it is clear that the reading is carried out by Adélia, the pig.

Only then, after exploring all the paratexts Stevenson begins the telling of the story. With the reading aloud the children understand that throughout the day, “Adelia plays with her brothers. At night, when everyone is asleep and silence reigns, something different happens in her country house”(ALPHEN, 2016).

The text presents a pact of friendship that is sealed through the books - mystery. The visual language makes the readers anxious to discover the secret between Adélia and Eveline. The story is full of symbolism and evokes the first readings and the passion for the literary text. After all, the characters share a love for reading, for books, and it is this feeling that seals the friendship explored throughout the narrative.

Thereby, the marking of the paratexts of Adélia’s work consists as a provocation to know and understand the importance of their appropriation within the literary mediation process and demonstrate that with some pedagogical resources we can enable the interaction and participation of children, because as Vasconcellos (2011, p. 35) says, in many situations we need to “[...] provoke a shock with something that seems so normal”. Given the above, we need to think about this issue inside not only classrooms, but also school libraries. We also need to rethink the planning of activities with reading, since a teaching action is essential to “plan and define, intentionally, the activities” (GIROTTO; SOUZA, 2010, p. 53).

In this process, teachers are the main responsible for promoting access to the literary text, but for this, it is important to understand that there are several ways for the interaction between reader/listener and text. The results also indicate the importance of exploring the paratexts, as well as the narrative and illustrations for the expansion of reading experiences. We believe that the verbal and visual language presented in a book, such as Adélia, contribute to the teachers and children’s experience of children’s literature as artistic expression and perception of the world.

CELLIJ and the Storytime project: a space for storytelling

Understanding the importance of storytelling for the development of human beings and the formation of readers, there is at the Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, Presidente Prudente Campus, the Study Center of Reading and Literature for Children and Young People (CELLIJ). In this Study Center there are several projects aimed at reader training, among them the Storytime Project.

The group involved in this project, university scholarship students and volunteers, performs storytelling on a weekly basis throughout the year for several schools in the Presidente Prudente region.

The storytellers form a team that works in “Storytime” and defines a theme to be worked on an average of three months. Some stories are chosen within this theme to be read in group, discussed and from then an average of two narratives are selected to be prepared for storytelling. From this selection (thematic and literary), the whole environment of CELLIJ is also prepared according to these selections and aims to make the space a reading mediator. Thus, when viewing an object that refers to fairy tales, for example, the child may expand his previous knowledge and want to read other texts, other stories.

The group is also involved in studies and preparation moments so that the storytelling sessions are all organized and previously planned, with a prior and careful choice of story, technique, and scene objects, so that the story is well received by the audience, and all external elements to the story will contribute positively to the storytelling moment, and to the participation and interaction of the listeners.

Thus, it is still the team’s goal to keep alive the traditional practice of storytelling and through the invitation for the children to sit and pay attention also bring them closer to reading and the literary world.

This way, even with all the planning, the project’s storytellers emphasize the performance of the storyteller, such as the techniques that allow a positive bond between the story teller and the participants. The atmosphere created at CELLIJ allows children to participate in the situations proposed by the story, which in this case, are planned and understood by the story tellers, giving credibility to the performance. The function of these story tellers, therefore, is not only to tell a story, but also to mediate the relationships between the listener, the text, the space, the reading, and literature books.

Next, we will talk about how the planning process of the theme cycles, the stories, and the environments take place, bringing examples of practices experienced in a storytelling cycle at CELLIJ.

The storytelling journey: planning in the CELLIJ theme cycles

Cycle “ Several Versions of Little Red Riding Hood”

Returning to the aspects already discussed in this article, storytelling is an art, and therefore requires technique, preparation, and study.

It needs to be planned and rehearsed, so that, with quality, with the right resources, it can delight the audience, and thus make the listeners get involved and enjoy it, offering a moment of pleasure with literature, leading them to want to seek more stories, later, in books.

To show this whole process in practice, the development of preparation and action of the storytelling cycle at CELLIJ with the theme “Several Versions of Little Red Riding Hood” elaborated and executed during the months of February to June 2018 will be brought in this section.

In the “Storytime” project at CELLIJ, before the preparation of the cycles, the group meets to think about a theme that will be worked on for the next months. To think about the details to be prepared, the group uses as support the studies by Solé (1986) who defends the importance of thinking not only about the moment of reading, but also about planned moments before, during and after reading. Thus, these moments are designed to offer the listeners a more meaningful experience, also visiting CELLIJ.

So, in February 2018, the team met and, in a dialogue about several themes, we selected the one that we will discuss below.

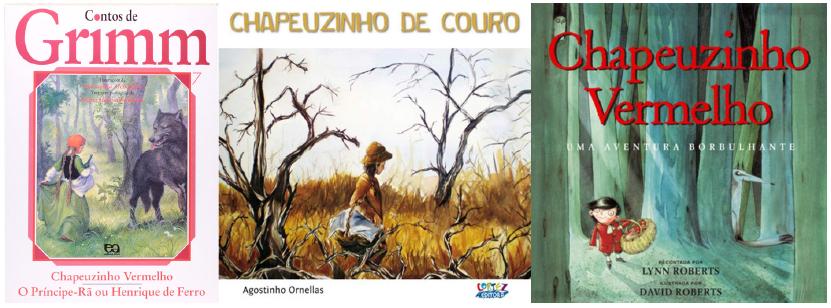

The project’s guiding teacher suggested working on fairy tales; there would be two stories, a classic fairy tale and a current one. The suggestion was accepted by the group and everyone started to look for children’s books on the subject at the Biblioteca Infantil de Prudente (BIP), also part of CELLIJ. Some children’s books were brought and, after discussion, the books Chapeuzinho Vermelho (Little Red Riding Hood) (GRIMM, 1997), Chapeuzinho Vermelho: Uma aventura borbulhante (ROBERTS, 2009), and Chapeuzinho Amarelo (BUARQUE, 1995). This way, the storytelling would be planned and executed with these three texts.

One of the reasons for choosing fairy tales is because, according to Souza and Cardoso (2016, p. 147), it is important that

the new generations have insight into children’s literature considered classical, which emerged from the Medieval Popular Novel, which, in fact, has its roots in oriental sources. When we talk about children’s classics, fairy tales or wonderful tales, we immediately remember Perrault, the Grimm Brothers, Andersen, or La Fontaine’s fables, but we forget that most of the time they are not the real authors of these narratives. With the exception of a few stories written by them, such as Andersen, the achievement of these 17th century writers, interested in the folk literature of their countries, was to gather and record in books the tales of the oral tradition, and these works spread throughout the world.

The authors also talk about the relevance of approaching the classic tale with a retelling, as is the case of Chapeuzinho Vermelho: Uma Aventura Borbulhante (ROBERTS, 2009), and Chapeuzinho Amarelo (BUARQUE, 1995), because it is taken into consideration that “the interpretation of the literary work benefits from the reading that compares and puts them in dialogue, seeking to broaden the critical understanding of them” (p. 150).

Moreover, Souza and Cardoso (2016) complement by saying that

Such procedure is supported by the dynamics of literature itself, which takes place in the course of constant dialogue between texts, forming a kind of continuation permeated by mirroring, exchanges, disagreements, and reinvention. In this way, every author would be in a dialogue with previous and contemporary writers (p. 150).

So, after choosing these three texts, other meetings were held to think about how the stories should be told and what techniques and objects should be used. Considering that the children probably already knew the original story of Little Red Riding Hood and could even find it boring to listen to it again, we thought that for this story one of the storytellers could come in in a costume as Little Red Riding Hood and ask them what they knew about the story. This way, children would tell the story, and the teller would only direct the facts told by the children to the Grimm Brothers version, and together they would remember and tell the story. According to Silva (1986) this technique is called simple storytelling with the interference of listeners, when children complete or participate in storytelling.

After reading and analyzing the other two stories, the group thought that the text Chapeuzinho Amarelo written by Chico Buarque would fit into a simple narrative, with the use of objects, which would be a yellow hat representing the main character and a black boot being the wolf. For the story Chapeuzinho Vermelho: Uma aventura borbulhante we thought about dramatization, and the storytellers would play the characters themselves, performing the story of the book.

After thinking about the techniques, we would use, the materials, costumes, and elements that would be added to the stories were elaborated. For example, the ending of Chapeuzinho Amarelo was adapted, and instead of being narrated, it would be sung, making children repeat it once, with us singing.

When the stories were ready, the environment that could also act as a reading mediator was planned, besides awakening in children the feeling of a magical universe of storytelling and contributing to the activation of reading strategies. These strategies are used in the formation of the cycle, as they contribute to a better understanding of the text (SOLÉ, 1998). In this way the storytelling cycle seeks to activate them during the entire time at CELLIJ, to provide a more meaningful experience between the narrative, the storyteller, the listener, and the mediation.

The strategies brought by Girotto and Souza (2010) are: prior knowledge, connection, inference, visualization, questioning, summarizing and synthesis. When faced with the environment all prepared, the child begins to make connections of what he or she is seeing with his or her previous knowledge, i.e., from an element such as wolf footprints children could remember the text of Little Red Riding Hood, and also others such as The wolf and the seven little goats, The Three Little Pigs, among several other stories, depending on their prior knowledge.

Making connections to personal experiences enhances understanding. Readers’ experiences and prior knowledge feed the connections they make. Books, discussions, newsletters, magazines, the Internet, and even casual conversations create connections that lead to new insights. Teaching children to activate their prior knowledge, as well as their textual knowledge, and think about their connections is fundamental to understanding. (GIROTTO, SOUZA, 2010, p. 67)

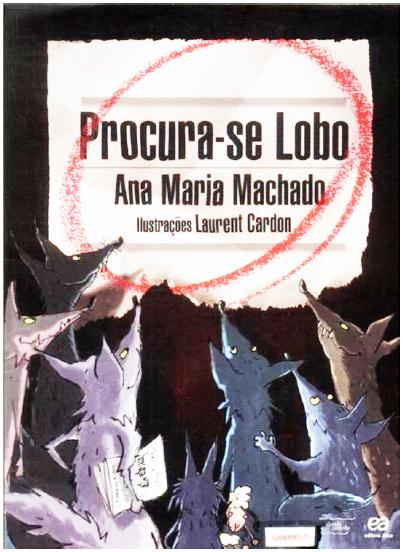

Consequently, when they arrived at CELLIJ, children found a sign on the door that read “Wolf Wanted” (which referred to another well-known book) with scratches that showed that the wolf had passed by, so our goal was to get children to start activating some of the reading strategies. For example, based on their prior knowledge, which is the knowledge they have about the world, by looking at the sign they made connections to other stories that had wolf as a character, and hypothesized (inferred) about what could happen inside CELLIJ, what stories could be told, and what surprises were to come.

For Girotto and Souza (2010, p. 76), “readers infer when they use what they already know, their prior knowledge, and establish relationships with the text’s clues to reach a conclusion, try to guess a theme, deduce a result, make a big idea, etc.”

To activate these strategies, CELLIJ uses all the spaces and among them we created the “inference corridor”, which has the objective of encouraging children to make inferences before listening to the stories, based on what they experience there. In this corridor, which precedes the entrance to the storytelling room, are placed elements that have some relation with the theme of the cycle, and the stories that will be told.

In this 2018 cycle the hallway was all characterized as if it were a forest, there were more “Wolf Wanted” signs and wolf footprints on the floor. So when the children entered, they were impressed and already began making their connections through the elements, being guided by the storytellers who in the hallway asked questions like, “What are you seeing?”, “What does this place look like?”, “What do these footprints look like?”, “What stories do you know that have a wolf?”, “Are these the stories you are going to hear?” What do you think?”

Source: Researcher’s collection (2018)

Figure 8: Inference corridor cycle “several versions of little red riding hood”.

The storytelling room was also prepared with a scenery that recalled the forest of the tales of Little Riding Hood, with Grandma’s house, and other elements that were used for the telling of the three selected stories. There was a sign indicating two paths - Grandma’s house and the dangerous path - a stone and spikes for the story Chapeuzinho Vermelho: Uma aventura borbulhante, and apples on the tree for this same story. Also making up the scenery were the yellow hat and black boot that were used in the second narrative (Chapeuzinho Amarelo). In addition, the wolf footprints that started in the hallway continued in the storytelling room, suggesting that the wolf was around, completing the mystery when he appeared in the last story. This whole environment helped the children to enter the classic universe of fairy tales.

During the storytelling, while listening to the story, the children formed mental images of the descriptions brought by the storyteller, thus experiencing the strategy of visualization.

Source: Researcher’s collection (2018)

Figura 9 The telling room: various versions of little red riding hood

When readers visualize, they are constructing meanings by creating mental images, because they create scenarios and figures in their minds while they read, raising the level of interest and thus keeping their attention (GIROTTO, SOUZA, 2010, p. 85).

Source: Researcher’s collection (2018)

Figures 10 Storytelling cycle “Little red riding hood, different versions”.

For example, in the story of Chapeuzinho Amarelo, there was only a yellow hat and a boot for the children to look at, but from the narrative they could create much more detailed mental images, as in the description “[...] A Wolf that was never seen, that lived far away, on the other side of the mountain, in a hole in Germany, full of spider webs, in a land so strange, that you will see that the Wolf didn’t even exist” (BUARQUE, 1995, n.p).

At the end of the storytelling sessions, we opened a space for dialogue about the stories, so that the children could reflect on what they had heard, ask questions, and thus expand their interpretation of the stories.

We are often commenting on what makes an impression on us: everyday facts, the last book we read, movies, plays, television soap operas. Commenting, it seems, extends the delight, leads to new readings of the plot, of the characters, to a clearer and more enlightening understanding (SILVA, 1986, p. 57).

Usually, this dialogue is initiated by the storytellers who ask: “What did you think of the stories? “Which one did you like the most? Why?”, “Which character did you like the most?” and so on, the answers were very diverse regarding preferences, but they were always excited after the stories, answering excitedly and ready to go to the next part.

After the storytelling moment, the participants went to the next room, where the Children’s Library is located, with a considerable collection of children’s books. In this cycle, when we said we were going to another environment, most of the time the participants asked if we would continue with the costumes, and they treated us as if we were still characterized by the characters in the stories, and not by our names, continuing in the universe of the stories even after the end. The children commented on what they had heard, many came to talk about their fears relating it to the story Chapeuzinho Vermelho, others said they wanted to taste Tomas’ bubbly soda, and that they were happy the wolf would not eat anyone else because of Chapeuzinho Vermelho: Uma aventura borbulhante. We can see, in this story there is an agreement made between Little Riding Hood and the wolf. In addition, they asked the storyteller, who was characterized as Little Red Riding Hood, about Grandma, and more details about her story, and they also said that they would like to go with her to the forest.

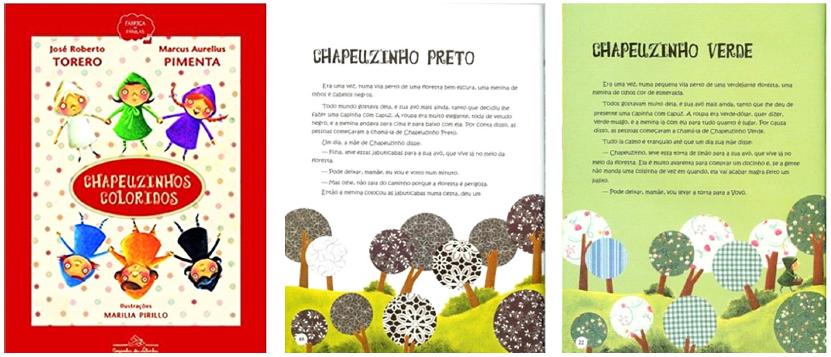

As seen previously, the BIP space is also a mediator, and is all characterized according to the theme. In a bookshelf, books that relate to the theme are separated, and in this cycle several versions of the Little Red Riding Hood story, adaptations and rewritings stand out, such as:

On the shelves of the BIP were hanging several capes of little Riding Hoods of various colors, which children could wear while doing the activity, and could feel like a version of Little Riding Hoods. This idea also came from the book Chapeuzinhos Coloridos (TORERO, PIMENTA, 2016), a book of tales in which there is a different story for each Little Riding Hood, as we can see in the pictures below: Little Black Riding Hood and Little Green Riding Hood.

So, dressed as little riding hoods of many colors, the children had a proposed activity for this cycle of writing a letter to some character in the stories they had heard, so that later Little Red Riding Hood (a storyteller dressed up as Little Riding Hood) could take it to the characters. So, they wrote the letter and Little Riding Hood collected it and put it in her basket.

These activities are carried out because, according to Silva (1986) “The story does not end when it comes to an end. It remains in the mind of the child, who incorporates it as food for his creative imagination” (p. 59). Therefore, for the author “Whenever possible, it is advisable to propose subsequent activities. The so-called enrichment activities help the children absorb this nutrient in a process of association with other artistic and educational practices” (p. 59).

Source: Researcher’s collection (2018)

Figure 13: Bip in the “several versions of the little red riding hood” cycle

Once the activities were over, the children were free to enjoy the BIP’s book collection, always under the guidance of the storytellers who pointed books, helped them read, and influenced the children’s contact with books and literature.

In view of the above, from the experience reported with this cycle of CELLIJ, it is possible to see how important it is to prepare the storytelling, the space, and the entire process for it to take place, and thus choose appropriate stories and techniques that contribute to further enrich the storytelling and the knowledge of the readers/listeners, so that the cycle, the theme, and the storytelling encourage and stimulate children to seek reading.

At CELLIJ, because it is a project for the community, and takes place in a large and static space, it is possible to have all this preparation of the place, and more time to study the stories. However, it is also possible to prepare a quality storytelling session in less time and with less space, if we continue to study the stories, and maintain the same professionalism and care in the preparation.

We are born storytellers, but many times we feel insecure or have not studied about the text and the ways of taking it to the students and children, compromising the narrative. Thus, for the reasons already listed here, we believe that to be a storyteller it is necessary to have a relationship with art. After all, storytelling should be, whenever possible, prepared, and thus will most likely reach the imagination and the hearts of the listeners, be it with thrill, surprises, or laughter. Every well-told story has a contribution to make.

Conclusion

In view of the above and taking into consideration the studies presented, we conclude that storytelling and reading stories are practices that have been present since the very first moments of humanity and are still alive today, echoing in today’s world, adapting and evolving, and also carrying tradition with them. Listening to and telling stories allows us to give others the opportunity to imagine, to wonder, to get to know, and to venture through oral narratives, which greatly contribute to the development of any person, especially children.

Listening to stories leads children to feel various emotions that humanize them, to feel pleasure and enchantment, and brings them closer to the literary universe.

Thus, because it is so important and essential, it is clear that it should not be done in any old way. Storytelling and reading stories are arts, and when done with care, with a study of the narrative, of the techniques, of the possibilities, it will sound farther, reaching more special plans to the listeners, captivating and enchanting them.

In view of this, this work brought the important issue of reading and storytelling, contributing to a better understanding of these arts, being possible through what was studied and discussed to stimulate parents, teachers, librarians or other subjects to improve their practices, providing more complex experiences to the listeners. These children in training will have more opportunity to become readers and certainly see the world in a more comprehensive way if they have contact with these ways and explore a text: whether by speaking, by telling, by activating reading strategies, by the perception of a mediating space, by the dialogical contact with the one who tells and instigates the listener to share his various stories.