Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista da FAEEBA: Educação e Contemporaneidade

versión impresa ISSN 0104-7043versión On-line ISSN 2358-0194

Revista da FAEEBA: Educação e Contemporaneidade vol.31 no.68 Salvador oct./dic 2022 Epub 13-Ene-2023

https://doi.org/10.21879/faeeba2358-0194.2022.v31.n68.p215-230

Articles

CHILDREN´S DIGITAL LITERATURE, SOUND EXPERIENCES AND LISTENING TO STORIES

*Ph.D. in Linguistics and Literature from the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Faculty member in the Doctor of Education and Cultural Studies program at the Lutheran University of Brazil (ULBRA). E-mail: ekirchof@hotmail.com

**Ph.D. in Education from the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA). Faculty member at the Faculty of Education at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), Salvador, Bahia. E-mail: gisellylima@ufba.br

This article discusses the potential of voice in digital children’s literature in terms of what it adds to the experience of listening to stories by children and young people. The article presents the results of the analysis of the way in which the voice is used, in seven digital narratives for children, as a semiotic resource capable of producing meaning effects such as humor, affectivity, immersion, among others. The corpus of analysis is composed of Brazilian and international productions, and the theoretical foundation that supports the reflections is based on the studies of Walter Ong, Frédéric Barbier and Roger Chartier on orality, written culture and digital culture; in Gunther Kress’ studies on multimodality; and in Paul Zumthor’s studies on the poetic word. The analysis reveals that digital children’s literature brings up aspects of the narrative tradition and also promotes ruptures in this tradition by converting the voice into a semiotic resource that makes up the literary work, which becomes multimodal and interactive.

Keywords: digital children´s literature; orality; digital culture

O presente artigo discute sobre as potencialidades da voz na literatura infantil digital quanto ao que ela acrescenta à experiência de audição de histórias por crianças e jovens. O artigo apresenta os resultados da análise do modo como a voz é utilizada, em sete narrativas digitais para crianças, como um recurso semiótico capaz de produzir efeitos de sentido tais como humor, afetividade, imersão, entre outros. O corpus de análise é composto de produções brasileiras e internacionais, e a fundamentação teórica que sustenta as reflexões se baseia nos estudos de Walter Ong, Frédéric Barbier e Roger Chartier sobre oralidade, cultura escrita e cultura digital; nos estudos de Gunther Kress sobre multimodalidade; e nos estudos de Paul Zumthor sobre a palavra poética. A análise revela que a literatura infantil digital recupera aspectos da tradição narrativa e também promove rupturas nessa tradição ao converter a voz em recurso semiótico que compõe a obra literária, a qual se torna multimodal e interativa.

Palavras-chave: literatura infantil digital; oralidade; cultura digital

El propósito de este artículo es discutir el potencial de la voz en obras de literatura infantil digital y su aportación a la experiencia de escuchar historias para niños y jóvenes. El artículo presenta los resultados de un análisis que investiga cómo se utiliza la narración con voz, en siete narrativas digitales para niños, como recurso semiótico capaz de producir efectos de sentido como humor, afectividad, inmersión, entre otros. El conjunto de obras seleccionadas está compuesto por producciones brasileñas e internacionales, y la base teórica que sustenta las reflexiones se apoya en los estudios de Walter Ong, Frédéric Barbier y Roger Chartier sobre oralidad, cultura escrita y cultura digital; en los estudios de Gunther Kress sobre multimodalidad; y en los estudios de Paul Zumthor sobre la percepción sensorial de la palabra poética. El análisis revela que la literatura infantil digital recupera aspectos de la tradición narrativa y también promueve rupturas en esta tradición al convertir la voz en un recurso semiótico que conforma la obra literaria, que se vuelve multimodal e interactiva.

Palabras clave: literatura infantil digital; oralidad; cultura digital

Introduction1

Digital culture has been transforming print culture nowadays, just as, in the past, print culture has also transformed orality, which is no longer the hegemonic way of structuring social relations and symbolic organization of human experience. The evolution of the ancestral practice of telling and listening to stories is an example of how such transformations take place in a non-linear way and of how the different material objects, semiotic modes and cultural models constitute the narrative and literary experience. On the other hand, despite these changes, from the ancestral narrator, who was given the sacred power to safeguard the memory of his people, to the new ways of narrating brought up by written and digital culture, the human voice has remained as an indispensable resource for the fruition of the poetic word.

Given this context, in this article, we propose a discussion about the possibilities that digital children’s literature presents regarding the experience of listening to stories by children and young people. Based on the theory of multimodality and in dialogue with studies by Paul Zumthor (1997, 2000) on the role of sensory perception of the poetic word, we seek to demonstrate that the voice, in digital narratives for children, is also capable of producing poetic effects, even if its material form is not a living body. Hence, we analyzed how the “acoustic dimension of voice” and “voice-mediated interactivity” were projected, in a set of digital narratives for children, with the intention of producing certain meanings and effects. The works analyzed are A história do Pequeno Grande Traço (BLOCH, 2018), Little Red riding hood (NOSY CROW, 2013), Marina está do contra (WOLDE, 2017), The monster at the end of this book (SESAME WORKSHOP, 2011), The heart and the bottle (JEFFERS, 2011), Spot (WIESNER, 2015) and Quanto Bumbum! (MALZONI; ESTEVES, 2016).

Before presenting the analyses, however, we initially engage in a discussion about the relationship between orality, written and digital culture, based on authors such as Walter Ong (1982, 2012), Gunther Kress (2010), Frédéric Barbier (2005), Roger Chartier (1987, 1994), among others. Then we bring a section on the relationship of orality with printed children’s literature. In the penultimate section of the article, we briefly discuss the limits and potentialities that the human voice acquires in the context of digital media for the poetic experience, based on the reflections of the Swiss scholar Paul Zumthor (2000) on the poetic word. Finally, we end it with the analysis of seven book apps, in which we seek to demonstrate that there is a new experience provided by the human voice in literature that is made possible by digital technologies. We conclude that, despite the losses in relation to everything that involves the embodiment that characterizes the natural human voice, it is possible to recover the traits of a corporeity that remains capable of producing effects on the reader.

Orality, written culture and digital culture

As Meek (2004, p. 25) emphasizes, written culture is developed and established through language, that is, it is a “language subject”. The same can be said of digital culture, since, from the perspective of multimodality, language is defined as a set of semiotic resources that can be used for the production of meanings and for communication between human beings (KRESS, 2010). The German semiotician Gunther Kress (2010) warns us that written verbal language is just one among several other semiotic modes that we use to produce meanings and communicate. Likewise, according to Kress (2010, p. 28), “in communication, several modes are always used together, forming sets of modes, which are designed so that each mode has a task and a function”. In other words, when we communicate, we usually mix visual, spatial, tactile, gestural, auditory and oral semiotic resources to build and convey our messages (KALANTZIS et al., 2016, p. 2).

Historically, orality precedes writing. As Canadian theorist Walter Ong (1982, p. 14) claims, the stories of genuinely oral cultures - today, increasingly rare - are very different from the narratives that circulate in literate societies, since, among many other characteristics, a narrative not influenced by writing will always be dependent on its immediate context of production and reception, presenting itself as a unique verbal performance of ephemeral duration. On the other hand, a story born in the culture of writing, even if it is oral, can be printed on some material object and, for this reason, acquires autonomy and independence in relation to the immediate context of production, and can be repeated over time. The narratives that emerge from digital culture, in turn, incorporate the affordances of sound and writing, as they are able to add different semiotic modes, in addition to introducing new possibilities of composition, such as moving images, interactivity, hypertext structures, hypermedia. and transmedia, among others.

According to Ong (1982), the effect of the emergence of writing on oral culture is not restricted to the possibility of translating sounds into letters or spoken words into written words, as the fixation of speech in space restructures thought and consciousness itself, since it turns words into objects or things. For this reason, the mere oralization of written texts, for Ong (1982), is not characterized as a phenomenon of oral culture in a strict sense, but should be defined, rather, as a type of secondary orality. Likewise, we can say that the mere transposition of written texts to digital media is not configured as a primary phenomenon of digital culture either. An analogy with the concept proposed by Ong (1982) allows us to conclude that primary digitality is organized from language and thought structures made possible by digital technologies, such as hypertext, multimedia, hypermedia, interactivity. Therefore, texts structured in the logic of written culture, although available for reading on digital device screens, constitute what we could call secondary digitality.

The emergence of printed books and their dissemination gave rise to several secondary orality practices associated with reading throughout history. Among book and reading historians in Europe, the prevailing understanding is that, during Ancient Times and the Middle Ages, for example, the practice of reading aloud and listening to written texts, in groups, was very common. However, with the increasing circulation of printed books, especially from the 18th century onwards, readers began to increasingly privilege the mental and silent experience of reading. For the historian Frédéric Barbier (2005), strong evidence that manuscripts from Ancient Times and the High Middle Ages were presented to be read aloud - either individually, in a way addressed to a group or through the mediation of a slave secretary - is the fact that his texts are arranged in scriptio continua; that is, they were not punctuated, divided into paragraphs or had words separated by spaces.

After Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press with movable type, the book gradually became more accessible. Along with the advance of literacy policies, printing stimulated and popularized the practice of reading as an individual, intimate, private act that demands a great emotional, intellectual and spiritual effort (CHARTIER, 1987). On the other hand, Chartier (1987) also warns us that it would be a mistake to consider that the spreading of silent reading would have replaced oral reading practices from Modernity onwards. An example of this kind of practice in the 18th century was the sale of song booklets in markets by the socalled chanteurs de foire, the song merchants. Before the sale of their booklets, these merchants would sing the songs that would be sold, accompanied by the sound of violin. As it can be seen, even in Modernity the oral practices of reading stories never disappeared.

Voice and children´s literature

One of the fields in which it is possible to perceive, in a special way, different modes of secondary orality is children’s literature. In fact, the link between this literature and orality goes back to the very origin of several texts considered children’s classics, such as fairy tales and countless versions of rhymed poems of popular origin. In the 18th century, when children’s books stood out as a profitable object in several European countries, the fairy tale turned out to be one of the most popular genres to compose these books (RUSSELL, 2014).

Originally, these narratives belonged to the oral tradition and were not necessarily addressed to children. It was only after being collected and adapted by writers such as Charles Perrault, in France, The Grimm brothers, in Germany, Hans Christian Andersen, in Denmark, Andrew Lang, in Great Britain, among others, that they began to be used. as a source for children’s books. At the same time, numerous poems of popular origin were also collected to compose these books, which, like fairy tales, had until then been transmitted orally from generation to generation.

The link between orality and children’s literature also stems from the use of children’s books as a pedagogical artifact. The expansion of the educational system in many European countries from the 18th and 19th centuries onwards has created the need for the production and publishing of “school books” and “children’s books”, although, as Ellis (1963, p. 3) points out, “it is quite arbitrary to draw a distinction between ‘children’s books’ and ‘school books’” to characterize the works of that time, since rarely, in that period, the narratives used in children’s books were simply a way of providing literary pleasure, since they were mostly used to fulfil the need to teach about morality and good manners.

As Reynolds (2011) highlights, recent research on the first publishers in England, dedicated to the production of children’s books, has revealed that the publishing market, in the 18th century, sought inspiration in homemade materials used as tool for teaching reading in social circles, such as those Jane Johnson had produced in the 1740s to teach her own children to read: cards, mobiles, toys and costumized books. Such materials emerged only in the 1990s. Reynolds (2011, p. 27) also clarifies that 18th century publishers sought to associate their children’s books “with homemade reading materials used by a careful adult - usually a mother, reading aloud and teaching children - with the aim of replacing them with their own printed versions of those same materials”.

Since 18th century, children’s literature has been a great ally of education and, both inside and outside school contexts, children’s books work as support for a large and wide range of practices involving the mediation of voice. In fact, gathering a certain repertoire of oral narratives, as well as the promotion of the production of books designed for children, resulting from the schooling process, has helped to constitute children’s literature itself as an autonomous literary system. This unquestionable institutional validation is, even today, one of those responsible for the growing social appreciation of literary narratives in childhood, on the one hand, and of the cultural practices around them, on the other.

The social value attributed to narratives is also supported by studies that bear the importance of traditional tales, in particular their symbolic function. The phantastic elements (GILLIG, 2004) present in these stories, along with the memory of human experiences condensed in them, play a structuring role in the psychosocial formation of children, according to scholars such as Bruno Bettelheim (1980), Jean-Marie Gillig (2004) and Clarissa Pinkola Estés (2018), among others. The presence, at school, of fairy tales, which today are part of the primordial repertoire of the narrative experience in childhood and whose origin relies on oral tradition, is due to the written record, via children’s book, and to the development of practices of sharing these stories for pedagogical purposes. Although there are many ways in which such practices occur, we highlight, here, storytelling and shared reading.

As part of a long tradition kept through mouth-to-mouth communication, the practice of storytelling, nowadays, faces obstacles in the school curriculum, and teachers are not prone to overcome them and invest on transmitting a story based on memory resources even though it is been recognized that this practice promotes an inner aesthetic experience with remarkable contributions to human formation (GIORDANO, 2013; SANTOS, 2013). In general, teachers lack a prior training that favors storytelling, making it dependable on individual wishes or rare institutional initiatives to break with the written-based tradition that marks formal education (SANTOS, 2013).

Shared reading, supported by the book, is a practice more frequently seen at schools, supported by research that reports its contributions to linguistic and literary training (BONAGAMBA, 2019; COLOMER, 2010; MENOTTI; DOMENICONI; COSTA, 2020; NOBLE et al., 2019), areas that rely on knowledge historically articulated with the formal curriculum. Strictly, the practice of shared reading involves reading aloud for one or more people who read it along, with structured oral interactions that seek engagement in reading (MENOTTI; DOMENICONI; COSTA, 2019). This type of reading is more associated with literary reading, especially picture books, and for children of preschool age, when the visualization of illustrations is necessary. However, reading aloud without the text, be literary works or not, has also been named that way.

As we can see, there is a difference between storytelling and shared reading. Although both are characterized as voice-based practices, they bear different articulations with orality. The first, even when using written sources, in the act of telling, relies on the memory and singularities of each narrator, who mobilizes his own linguistic and gestural repertoire, evoking the narrative tradition of oral culture, its repository, its meanings or motivations and establishing a type of dual relationship with the listener, but which constitutes a single act of co-presence (ZUMTHOR, 2000). Now in the act of shared reading, the voice is a means of conveying the written language and the literary discourse produced, mostly, by a particular author, involving a triple relationship, which involves the book, the reader and the listener even though the reader’s performance may add layers of meaning to the act of reading through the intonation of his voice and the gestures which come with it.

The disembodiment of voice on digital midia

In all secondary practices of orality presented in the previous sections, whether linked to children’s literature or other contexts of reading and listening to texts, the human body is necessarily the bearer of the voice that narrates. On the other hand, with the emergence of electronic media - such as radio, television and digital media - which include any type of computerized materiality -, the body is no longer the source of speech during the listening experience, as these media have the ability to automatically (re)produce the human voice.

Back to the 1980s - thus, prior to the popularization of digital technologies - Walter Ong (1982, p. 3) had highlighted the importance of electronic media being able to capture sounds and, therefore, also spoken words, which led him to conclude that “the electronic age was also the age of ‘secondary orality’, the orality of telephones, radio and television, which depend on writing and printing for their existence”. Today, with the development and ubiquity of digital media, it is possible to say that secondary orality has reached an even more complex stage, since, unlike electronic media, digital supports comprise different semiotic modes, making the representations we build in the contemporary world increasingly multimodal.

The Swiss intellectual Paul Zumthor (2000) helps us to think about the limits and potentialities that sound acquires in the context of digital media for the poetic experience, for two main reasons. First, because voice plays a central role in his theories about poetry and, second, he includes, in his theories on the reader, sensory perceptions or, in his terms, the “living body”. (ZUMTHOR, 2000, p. 27).

Since the 1970s, when he dedicated himself to the study of voice in poetry during the Middle Ages, as well as to the study of poetic practices carried out in different non-European cultures - such as the griots of Burkina-Faso, the rakugoka of Japan, the Brazilian repentistas, among others -, Zumthor (2000, p. 34) concluded that “performance is the only living mode of poetic communication”. This thesis is so central to his thinking that it led him to claim that there is a difference between literature, understood as a specific type of poetic manifestation produced in Western society, and poetry, a broad primary phenomenon, which encompasses not only Western literature, but any anthropological practice that involves the sensorial perception of texts taken as poetic by some particular and concrete subject.

For Zumthor (2000), poetic performance depends on a convergence of three instances: subjects who produce metamimetic texts - that is, texts whose primary function is not to represent the world, but to emancipate language from the power that time has to consume us; a set of texts that have qualities understood as metamimetic by these same groups; and an audience capable of recognizing such qualities. However, the poetic experience itself emerges only when there is a ritualization involving these three instances, through which particular subjects are affected not only mentally, but also in their sensory perception system. In this sense, the most original examples of this poetic manifestation are connected to the oral performance of poetry, which necessarily demands the presence and engagement of both poet and listener in the same ritualistic act.

In the course of his studies on voice and poetry in the Middle Ages, this author concluded that the silent reading of literary texts only reaches its aesthetic potency to the extent that, somehow, it is also able to affect our bodies, even if in a different way, just as a listener is affected by a ritualized work in an act of performance. Due to the predominance of writing in Western society from Modernity onwards, there was a loss of the oral and performative dimension of poetry, which, for him, is equivalent to a loss of the poetic identity itself. In his terms, “For being used, in literary studies, to dealing only with writing, we are led to remove the text from the global feature of the performed work and focus on it alone” (ZUMTHOR, 2000, p. 30). However, when we focus on the written text and neglect the originally oral dimension of all poetry, we also lose the ability to understand its most fundamental characteristic, namely, the pleasure generated by the experience of its fruition, which is, by its time, based on the pleasure of taking part in a performance.

More than studying reading as a neutral act of decoding information, then, Zumthor (2000, p. 24) seeks to understand “the reader reading, the operator of the action of reading” and, therefore, considers it essential to question himself about “the role of the body in reading and perceiving literality” (ZUMTHOR, 2000, p. 23). Although he does not deny the existence of other criteria to define the poetic effect of a work, this author believes that, in the individual act of reading, poeticity is defined as a type of pleasure on the body that “emanates from a personal bond established between the reader who reads and the text as such. For the reader, this pleasure constitutes the main criterion, often the only one, of poeticity (literariness)” (ZUMTHOR, 2000, p. 24). From this perspective, literary value is not defined as something essential, fixed or absolute, because, although it also depends on the way in which the signifiers are mobilized and articulated to produce effects of enjoyment on the body that perceives it, there is no guarantee that each reader will be affected alike by the same poetic composition. In this sense, the Swiss theorist even states that, for a teenager in love, sugary novels full of clichés, such as the stories in the Harlequin series, may have a “true poeticity, although for many individuals in our society this may be an imposture, or simply a non-existent trait” (ZUMTHOR, 2000, p. 25).

When dealing with electronic media, the Swiss scholar refers to a relative loss of the body which is part of the poetic performance as a producer. In other words, in the enjoyment of works mediated by electronic technologies, this author believes that the effects regarding “corporeity, weight, heat, the real volume of the body whose voice is just expansion” (ZUMTHOR, 2000, p. 16). On the other hand, we believe that, despite the disappearance of the body in electronic and digital sources, in recent digital works, the recorded and reproduced voice is linked to a sort of corporeality, i.e., the verbal-visual-kinetic representation of living bodies, which are figurative as characters and narrators who also express themselves through the oral modality. In works of children’s digital literature, the voices of these fictional characters are placed at the service of literary communication with the child and, on this wise, as well as printed works and oral performances, they also seek to stir up poetic effects on readers. Hence, if it is true that the poet’s living body disappears from the performance that constitutes the enjoyment of electronic works, it is equally true that the voices of the artificial bodies dwelling these works also aim to affect the reader’s body, providing him with poetic pleasure.

Sound and children´s digital literature

With the development and popularization of digital technologies in recent years, different agents related to the world of books were more likely to use electronic devices as source of reading. In this context, physical bookstores are being gradually replaced by sales platforms over the Internet - especially the giants Amazon, Google, Apple, but also streaming platforms focused on the book market. Physical libraries, in turn, as the study by G. Sayeed Choudhury and David Seaman (2013), among others, suggests, are increasingly lying on the purchase of electronic texts, collections of digital images as well as audio and video titles. Another space where many digital books are available are self-publishing platforms - such as Wattpad and Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing (KDP). In most of these spaces, there are works originally printed that were digitized using programs such as PDF and EPUB, along with original works that, although designed for reading on screens, are structured from the same elements that constitute the printed book format: linear sequence of pages, cover, back cover, etc. As we can see, this sort of work does not explore the potential provided by digital technologies to produce new reading experiences and, therefore, they are an example of what we called “secondary digitality” in the first section of this article.

On the other hand, there are also literary experiments that incorporate interactive, hypertextual and hypermedia structures, as well as multimedia resources such as animations, voice reproduction, interactivity, and moving images. In this set, the so-called book apps of children’s literature stand out, they can be defined as productions with resources displayed by an application software, which allows the reader to physically interact with the representations, enjoy immersive experiences through the gyroscope or the camera, move images and letters with the touch of the fingers, start small animations, play games and listen to music, soundtracks and sound effects that comes along with narratives or poems, besides being able to record and listen to the narration of the written text.

In recent years, researchers from different areas and theoretical fields have been arguing over the effects of such resources on reading, cognition and literary enjoyment. To this extent, while some researchers emphasize losses and risks, others point out new possibilities of reading and fruition. An example of research focused on the limits of digital works can be found in Tomopoulos, Klass and Mendelsohn (2019). These authors claim that digital works promote a solitary interaction between the child and the device, which would imply the loss of important speech interactions with adults that contribute to the development of cognitive skills and affective relationships.

Additionally, several other studies allow us to conclude that the possible damages caused by digital works do not lie in the simple presence or absence of digital resources, but to the lack of quality that characterizes the way they are used in some works. In their research with children, Hoel and Tønnessen, for example, concluded that “the success of multimedia resources lies in their good integration with storytelling and the opportunities they provide for extratextual discussion” (KIM; HASSINGER-DAS, 2019), p.5). Moreover, these researchers also point out that, “whether using printed books or digital books, the important thing is to open ‘room’ for dialogue [about reading] and, in the case of digital books, such opportunities can be offered through support” (HOEL; TØNNESSEN, 2019, p. 203). Amongst the various multimedia resources that integrate the works of digital children’s literature, sound resources stand out. The fact that digital works can emit sounds makes them different from printed books, with very few exceptions, such as some kinds of toy books that are also endowed with sounds, for example. In the theoretical field of multimodality, two main semiotic modes are defined for having hearing as the primary channel of reception, namely: the audio mode and the oral mode (KALANTZIS et al., 2016). While audio meanings range from “ambient or background sounds in our environment, to sounds that have symbolic meaning, and to the complex meanings represented in music” (KALANTZIS et al., 2016, p. 401), oral signs, although they are almost always mixed with audio meanings, are defined by speech and the human voice and, therefore, cover the phenomenon of secondary orality.

Audio meanings are widely explored in literary narratives produced or adapted as book apps, for instance, musical scores and different sorts of sound effects in the stories, many of which are triggered by the physical interaction of the reader with the narrative, for example, when he touches the so-called “hotspots”. Now the oral mode is presented in functions such as “Read to me” and “Self-play” - which narrate the stories automatically -; “Audio recording” - which allows readers to record their own voice narrating the story; the “Automatic narration of single words”, usually triggered by touch. At the level of the story itself, orality is often used to give voice to the narrator and characters, and very often its manifestation depends on the reader’s physical interaction with some element of the narrative.

It is important to highlight that the presence of the voice in the composition of these works produces meanings, but also effects on the reader’s body, which are different from those produced by reading printed texts. When such meanings and effects are coherently integrated with the poetic proposal of the work, they are capable of providing a significant experience of literary enjoyment. Given the above, we propose a discussion about two main dimensions regarding the use of voice in children’s digital narratives to produce poetic meanings and effects: the acoustic dimension of the voice; and voice-based interactivity. The first dimension comprises the meanings generated by the matter of acoustic expression in the context of each narrative; the second dimension, in turn, covers the meanings and effects generated by the possibility granted to the reader to participate in the production of the sounds of the narrative via interactivity.

The acoustic dimension of voice

Since digital literature, in addition to written verbal signs and images, also mobilizes sound signifiers in its composition, the analysis of digital works needs to take into account the effects of meaning that voice, as a literary signifier, is capable of producing at the sensorial and mental level of the listener. On the whole, in digital works, the voice can be present in “narration” - when the voice of a narrator leading the plot is heard -, in the “dialogue” - when the characters communicate orally with each other, with themselves, with the narrator and, sometimes, even with the reader - and through “uproar” - vocal sound manifestations in the background of the scenes, such as murmurs and whispers.

With regards to narration and dialogue, the acoustic characteristics of the voice act, above all, as signs concerning identity (gender, age, regional, national, etc.) of the speaker. By associating the acoustic information with the one contained in the images and in the verbal text, the reader creates his own representation of the narrator and the characters. Often, the identity characteristics of the characters and the narrator are repeated in each semiotic modality - text, image and sound - and the effect produced on the reader, in this case, is a greater degree of immersion in the narrative universe. On the other hand, in some works, these characteristics are dissociated in order to produce stylistic effects, such as humor.

In the Little Red riding hood app (NOSY CROW, 2013), for example, Little Red Riding Hood is the main character in the story and one can tell, by her voice, she is a child. The characters Grandma, Mom and the wolf, although visually depicted as adults, also express themselves with children’s voices, in a necessarily lower tone, in order to imitate the voice of an adult. This fake adult voice, actually composed of the altered child’s voice, brings humor to the reading experience of this app. In addition, such practice refers to the typical orality of a puppet theater, in which the puppet handler modifies his own voice to add a certain identity to the characters. As we can see, in this work, the creative use of the acoustic dimension of the characters’ voice refines the experience of fruition.

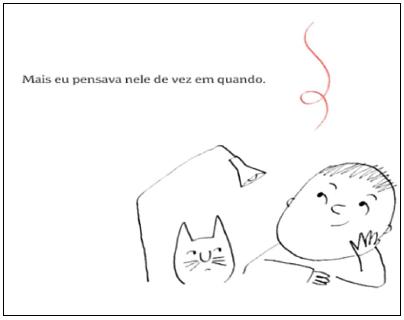

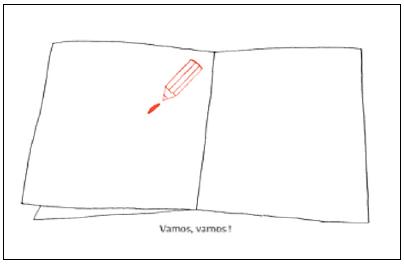

The Great Story of Pequeno Grande Traço (BLOCH, 2018) is another example in which the age characteristics of the narrator-character provided in the visual and sound modalities are used in a creative way: while the visual signs that make up the protagonist, at the beginning of the story, depict a child, the voice of the narration resembles an adult from beginning to end. The plot of this work is built around a great and powerful relationship that begins when the protagonist, as a boy, finds a piece of red string and takes it to his house. Both grow together and “design” life from new experiences and, at the end of the story, the protagonist becomes an adult. Imagination and creation are the engine of the relationship follow the boy’s growth throughout his life: as he grows up, his universe expands and gains density.

From a visual perspective, the narrative is characterized by the minimalism of its animated illustrations, in which, on the white pages, only the boy and his private world stand out: his cat, his drawing board and his objects. Almost everything is drawn with a thin black outline, only the small string is red. Orally, as previously said, although the images depict a child protagonist since the beginning, his voice tone reminds one of an adult man, which reveals the construction of an analepse - a narrative resource that produces the effect of retreat in time - through the articulation between the visual and sound mode. The acoustic characteristics of the voice narrating it, in the Portuguese version of this work, also provide information about the origin of the protagonist, who has an accent related to the Northeast region of Brazil, easily recognized by the Brazilian reader. This linguistic variation chosen for the narrator’s voice brings, to the experience of fruition, echoes of a culture that is embodied and affects the reader aesthetically.

Another effect generated by the acoustic dimension of the voice in this work is the reinforcement of a mood based on subjectivity and emotion. Since the story is told in the first person, building an internal focus on the main character, it brings about strong subjective tone to the speech. Besides, the visual-verbal text metaphorizes aspects of the boy’s inner world and feelings, while the images present allusions to the physical world and the episodes that make up the plot. In this context, the prosody of the narrator’s voice, which is presented by the intonation and by handling the duration of the sounds, producing verbalization and pauses, helps to anticipate and complement information to understand the minimalism of the images. The rhythm of his speech, as well as the interruption or duration of certain sounds, articulates with the visual text and helps to build meaning effects that indicate a certain emotion or brings up something unspoken that the reader needs to infer. It should be noted, moreover, that the work is interactive and, therefore, constantly demands the reader’s participation, asking him to draw along so that the narrative is completed and moves on. The verbal text articulated with the image often impels the reader to action, implying the time to draw with the red line. Within this context, therefore, orality also plays an important role, as the narrator’s intonation constitutes an important reinforcement of the invitation for the reader to take part in the construction of the plot through interactivity.

In the work Marina está do contra (WOLDE, 2017), although the narrator is neutral omniscient and, thus, is not part of the actions of the narrative, the nuances of his voice produce a series of senses and effects that provokes the reader at the moment of listening: the feminine timbre, the São Paulo accent, the smoothness, the high tone, etc. On the opening screen, among the paratextual information, the narration is recorded by the São Paulo singer Tiê. Probably, this paratextual information aims at highlighting, for the reader, the concern of the application developers with the quality of the vocal performance. In terms of the enjoyment of the work, however, the specific characteristics of voices give certain contours to the experience of reading, such as, for example, a crossing of gender, since the narration is made by a woman. Since the story deals with the daily life of a small child, his discoveries through play and his mood swings, the presence of a female voice can evoke the maternal role, as we live in a society in which the daily care of children is still linked to women.

In addition to being used to compose the narration and dialogue, the voice can also be used, in some works, to compose the uproar. This concept refers to the mass of voices or murmurs in the background of a scene, that is, vocal but non-verbal sound manifestations, such as individual or collective murmurs, whispers or speech simulations without verbal expression (MORAES, 2016, 2019). Aesthetically, this resource is often more powerful than speech itself, because, as Zumthor (1997, p. 13) states, “the most intense emotions arise the sound of the voice, rarely the language: beyond or below it, murmur and cry, immediately inculcated in the elementary dynamisms”.

Amongst the works in which the uproar was used to produce aesthetic effects on the reader are The heart and the bottle (JEFFERS, 2011) and Spot (WIESNER, 2015). In the first, created by the Bold Creative laboratory from the illustrated book by Oliver Jeffers, when representing the scene of an adult reading to a child, the sound of the reader’s voice is heard indistinguishably from his words, which are represented as muttering. The content of the book read to the child is represented through illustrations, while the voice is responsible for the emotional aspect of it, bringing a form of multimodal articulation in which one semiotic mode complements the other. In many cases, the uproar, as a vocal expression, avoids a redundant relationship between writing and speech, which could have occurred if the work sought to express, in words, what had already been represented in the illustration. In The heart and the bottle, instead of replicating information already presented in the visual mode, the voices present new information about the scene: the affectionate and calm tone, the welcoming of the adult at the moment of shared reading. This information, added to the image, is fundamental to build the emotional atmosphere of the scene in this work.

In Spot, by David Wiesner (2015), verbal language is also absent and replaced by visual, sound and interactive resources that allow the reader a progressive immersion in the fantastic worlds that compose the work, from the metaphor of a vertical journey performed by the reader on the wings of a ladybird. In this work, the reader moves through different worlds based on small elements, banal objects that are repeated in each one of them and function as portals to link the fictional spaces to each other. The different scenario built by music and sound effects contributes to compose each fictional environment that stems visually from static images, some discrete animations endowed with an interactivity that allows the reader to move in different directions across the screen, creating a zoom and long shot effect. In these worlds inhabited and visited by fantastic creatures, the uproar helps to build the humanization of the character-creatures and reinforce the images that represent the different forms of socialization between them, from a dialogue to the euphoric reactions of a crowd before a parade. By composing the soundscape and giving meaning to the characters’ actions, in Spot, the voices constitute a fundamental structural element of the plot. The network architecture of this work does not point to an end or to a single interpretation, which neither prevent stories from happening in the work nor jeopardize meanings from being constructed. In these different interconnected spaces, the reader is invited to think about the narrative architecture itself as a journey in different directions, whose objective is to enjoy the spaces and characters that are found in each of the worlds.

Voice and interactivity

Interactivity is one of the main structural elements of digital children’s literature and enables the reader’s part in the materialization of the work on the screen. This allows interaction with graphical interfaces - the visual signs that appear on the screen and contain programming code that can be activated by the user - and with physical interfaces - the devices that capture the movements, images and sounds of the user such as mouse, touch screen, camera, microphone, gyroscope. This possibility of physically interacting with the representations derives from different types of software, which allow the author/programmer to trace a script of the “reader’s role in the work, creating input cues and feedback loops for that interaction to be incorporated into the textual performance” (FLORES, 2014, p. 158). Many interactions previously seen in works of children’s digital literature involve voice and different sound effects.

One of the main results created by the articulation between orality and interactivity is the immersive effect, that is, the illusion of the reader’s presence within the work itself. In some digital works for children, the reader has the power to trigger sounds and sound effects linked to the narrative space and the characters’ actions. In this way, more than just a simple observer, in these cases, the reader becomes a character, even if it is an observer character. This narrative strategy can be found, for example, in the work Quanto Bumbum! (MALZONI; ESTEVES, 2016), in which the story of the birth of a bunny is told orally by a baby squirrel narrator in the position of narrator-witness. Since this narrative focus limits the vision field, the little squirrel is initially surprised by the grouping of animals in front of the rabbits’ den. As the animals appear on the screen, small circles also appear on their bodies, which are, in fact, interface icons that invite the reader to touch them. As a reaction to touch, each animal produces its species characteristic sound. The main effect of this resource on the little reader is the illusion that he is also physically present in the forest, even being able to pat the animals awaiting to meet the newborn bunny, which react to his touches with movements and sounds. In summary, interactivity and sound, here, enable a sensorial involvement of the reader with the story.

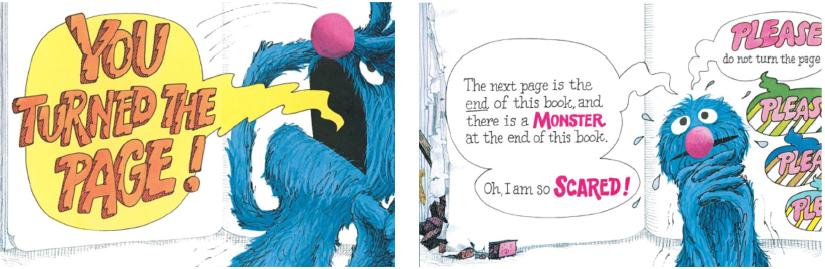

A narrative strategy capable of creating an intense immersive effect through the interaction with the voice is the oral interpellation of the reader by the characters. In the book app The monster at the end of this book (STONE; SMOLLIN, 2011), for example, the reader is inserted into the diegetic world of the narrative when he is addressed by the protagonist, a small blue monster named Grover, who is standing in front of a a great book. Early on, Grover says he is scared of monsters and, after reading on the book cover that there is a monster at the end of the story, he starts begging the reader not to turn the pages. It is important to clarify that this “conversation” between reader and character takes place simultaneously through the written and oral modes of language. As the reader fails to heed his pleas and taps on the arrows that mark the possibility of turning the page, the plot goes on, and the tone of voice in Grover’s lines reveals that he is increasingly frightened.

Although the physical interaction of the child reader, in this work, is limited to touching the arrows that mark the possibility of turning the pages, the way the voice is used instigates the child’s curiosity and imagination, as the “fear” expressed by Grover’s voice amplifies the will to know if there really is a monster at the end of the book and if it is as terrible as Grover thinks. When the reader finally reaches the last page, he discovers that the terrifying monster is Grover himself. The narrative strategy used in this work, therefore, assumes that the reader will do exactly the opposite of what is expected to, and this predicted disobedience is rewarded, in the end, because what could be a danger turns out to be a surprisingly pleasant discovery: Grover is a funny and humorous monster.

Final words

The narrative culture that has been updated in the digital form is similar, on the one hand, to the written culture because of the way it is placed at the service of writing and also because it constitutes a fixed element in the text, which always shows up with the same characteristics, in repeatable and non-accidental way - a fixity that, not long ago, was a characteristic of writing. This makes the voice an even more relevant element from a perspective of literary reception and the production of meanings in the digital experience. On the other hand, it stands with orality by allowing different readers to appropriate the text, creating new meanings with their own voices and establishing a corporeal relationship with this text.

Hence, we can say that, in digital literature, the voice, in addition to carrying characteristics that echo the corporeity of the narrator, the characters and, in some cases, the reader, also helps to build a communicative/narrative pact between reader and work, ratifying itself as a non-neutral element of narration due to its sound and prosodic characteristics. Furthermore, the new technological possibilities for the use of the voice relocates this semiotic resource in relation to the narrative tradition, since the significant elements they add are interactive and articulate with the multimodality in the literary experience, breaking with the tradition of silent writing and establishing new forms of literature reception. In this sense, the voice is not only a means of spreading the living word, but an instance of text and reading at the same time, which acts aesthetically because it deals with the spheres of sensory perceptions. It also bears something of the embodied - narrative and poetic - auditory memories, as well as presents innovative possibilities for narration and poetic composition.

Finally, it is important to highlight that, unlikely to what it can represent for traditional reading, the voice incorporated into the story, although it brings the possibility of autonomous reading by the child, does not prevent digital children’s literature from mediation. As well as other aspects that challenge the reader of digital works, the voice is a powerful semiotic resource, whose nuances of meaning demands comprehension skills, which are, in general, built in the set of narrative experiences that involve adult mediation, whether via storytelling or shared reading. In short, children’s digital literature requires the construction of a cultural ecosystem in which different narrative practices enable the pleasure of reading and also contribute to literary education.

REFERENCES

BARBIER, Frédéric. Historia del libro. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2005. [ Links ]

BETTELHEIM, Bruno. A psicanálise dos contos de fadas. 7. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1980. [ Links ]

BLOCH, Serge. A grande história do pequeno traço. Paris: Bachibouzouk, 2018. Versão para Android. Disponível em: https://play.google.com/ store/apps/details?id=com.lamanufacture.ghpt&hl=pt_PT&gl=US. Acesso em: 07 out. 2022. [ Links ]

BONAGAMBA, Camina. Leitura compartilhada de histórias e aprendizagem de palavras em crianças típicas e com Síndrome de Down. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, v. 37, n. 1, p. 73-88, 2019. Disaponível em: https://doi.org/10.12804/ revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.5975. Acesso em: 10 maio 2022. [ Links ]

COLOMER, Teresa. Introducción a la literatura infantil y juvenil actual. Madrid: Síntesis, 2010. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. A ordem dos livros: leitores, autores e bibliotecas na Europa entre os séculos XIV e XVIII. Brasília, DF: Editora da Universidade de Brasília (UnB), 1994. [ Links ]

CHARTIER, Roger. The cultural uses of print in early modern France. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987. [ Links ]

CHOUDHURY, G. Sayeed; SEAMAN, David. The virtual library. In: SIEMENS, Ray; SCHREIBMAN, Susan. A companion to digital literary studies. Londres: John Wiley & Sons, 2013. p. 534-546. [ Links ]

ELLIS, Alec. A history of children’s reading and literature. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1963. [ Links ]

ESTÉS, Clarissa Pínkola. Mulheres que correm com lobos. São Paulo: Rocco, 2018. [ Links ]

FLORES, Leonardo. Digital poetry. In: RYAN, MarieLaure; EMERSON, Lori; ROBERTSON, Benjamin J. The johns hopkins guide to digital media. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014. p. 155-161. [ Links ]

GILLIG, Jean-marie. El cuento en la pedagogia y en la reeducacion. Cidade do México: FDE, 2004. [ Links ]

GIORDANO, Alessandra. A arte de contar histórias e o conto de tradição oral em práticas educativas. Construção Psicopedagógica, São Paulo, v. 21, n. 22, p. 26-45, 2013. Disponível em: http://pepsic. bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1415-69542013000100004&lng=pt&nrm=iso. Acesso em: 26 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

HOEL, Trude; TØNNESSEN, Elise Seip. Designing dialogs around picture book apps. In: KIM, Ji Eun; HASSINGER-DAS. Reading in the digital age: young children’s experiences with e-books. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019. p. 197-216. [ Links ]

JEFFERS, Oliver. The heart and the bottle. Nova Iorque: Penguim Group, 2011. Versão para Ipad. [ Links ]

KALANTZIS, Mary; COPE, Bill; CHAN, Eveline; DALLEY-TRIM, Leanne. Literacies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016. [ Links ]

KRESS, Gunther R. Multimodality: a social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Routledge, 2010. [ Links ]

LITTLE Red riding hood. Aplicativo disponível em: https://apps.apple.com/. Nosy Crow, 2013. [ Links ]

MALZONI, Isabel; ESTEVES, Cecília. Quanto bumbum! São Paulo: Caixote, 2016. Versão para Ipad. [ Links ]

MENOTTI, Ana Rubia Saes; DOMENICONI, Camila; COSTA, Aline Roberta. Da capacitação de professores do ensino infantil para o uso de estratégias bemsucedidas de leitura compartilhada. CoDAS [online], v. 32, n. 1, 2020. Disponível em: https:// doi.org/10.1590/2317-1782/20192018294. Acesso em: 25 abr. 2022. [ Links ]

MEEK, Margaret. En torno a la cultura escrita. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2004. [ Links ]

MORAES, Giselly Lima de. Os recursos sonoros na literatura infantil digital: um breve estudo sobre a presença da voz nos aplicativos. Leitura: Teoria & Prática, Campinas, SP, v. 37, n. 75, p. 67-80, 2019. Disponível em: https://ltp.emnuvens.com.br/ltp/ article/view/748. Acesso em: 17 jun. 2022. [ Links ]

MORAES, Giselly Lima de. Trilha sonoras de aplicativos literários para crianças e educação literária. 2016. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA), Salvador, 2016. [ Links ]

NOBLE, Claire; SALA Giovanni; PETER, Michelle; Lingwood, Jamie; ROWLAND, Caroline; GOBET, Fernand; PINE, Julian. The impact of shared book reading on children’s language skills: a metaanalysis. Educacional Research Review, v. 28, nov. 2019. Disponível em: https://www.sciencedirect. com/science/article/pii/S1747938X18305116. Acesso em: 18 jun. 2022. [ Links ]

ONG, Walter J. Orality and literacy: the technologizing of the word. London: Routledge, 1982. [ Links ]

REYNOLDS, Kimberley. Children’s literature: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011. [ Links ]

RUSSELL, David L. Literature for children: a short introduction. 8. ed. New Jersey: Pearson, 2014. [ Links ]

SANTOS, Luciene Souza. A Emília que mora em cada um de nós: a constituição do professorcontador de histórias. 2013. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, 2013. [ Links ]

STONE, Jon; SMOLLIN, Michael. The monster at end of this book. Editora Sesame Street, 2011. Versão 1.0.0. Aplicativo disponível para dispositivos iPhone e iPad disponível em: https:// apps.apple.com/us/app/the-monster-at-the -end/id409467802. Aplicativo disponível para dispositivos Android em: https://play.google. com/store/apps/details?id=org.sesameworkshop. monsterone.play&hl=en_US&gl=US. Acesso em: 07 out. 2022. [ Links ]

TOMOPOULOS, Suzy; KLASS, Perri; MENDELSOHN, Alan L. Electronic children’s books: promises not yet fulfilled. Pediatrics, v. 143, n. 4, Apr. 2019. Acesso em: 24 jun. 2022. [ Links ]

WIESNER, David. Spot. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015. Disponível em: https://itunes.apple.com/ us/app/david-wiesnersspot/id963746523?mt=8. Acesso em: 12 maio 2022. [ Links ]

WOLDE, Gunilla. Marina está do contra. São Paulo: Caixote, 2017. Versão para Ipad. [ Links ]

ZUMTHOR, Paul. Introdução à poesia oral. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1997. [ Links ]

ZUMTHOR, Paul. Performance, recepção, leitura. Tradução de Jerusa Pires Ferreira e Suely Fenerich. São Paulo: EDUC, 2000. [ Links ]

Received: June 26, 2022; Accepted: September 28, 2022

texto en

texto en