Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1413-2478versión On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.24 Rio de Janeiro 2019 Epub 22-Nov-2019

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782019240056

ARTICLE

The common basic contents of school physical education in Minas Gerais: an analysis of their contexts of influence

ICentro Universitário Estácio Juiz de Fora, Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil.

IIUniversidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil.

IIIUniversidade Católica de Petrópolis, Petrópolis, RJ, Brazil.

This research aimed to analyze the contexts that influenced the production of the official curricular document for school physical education in the state of Minas Gerais: the common basic contents. We investigate the political, ideological, and epistemological aspects, adopting the Ball’s policy cycle (apud Mainardes, 2006) method and an unstructured interview script applied to the subjects who elaborated the curriculum proposal. We associated the data to relevant curriculum theories, such as those by Giroux (1997), Apple (2006), Moreira (2010) and Pacheco (2003). As results, we emphasize that the neoliberal influences on the document, as well as the false autonomy given to teachers in the elaboration process, resulted in their devaluation as transformative intellectuals.

KEYWORDS: curriculum; curriculum policy; common basic contents; policy cycle; teaching devaluation

Esta pesquisa tem por finalidade analisar os contextos de influência de produção do documento oficial curricular de educação física escolar do Estado de Minas Gerais, os conteúdos básicos comuns. Investigamos aspectos políticos, ideológicos e epistemológicos utilizando o método do ciclo de políticas de Ball (apud Mainardes, 2006) e um roteiro de entrevista não estruturada, aplicado aos sujeitos elaboradores da proposta curricular. Articulamos os dados às teorias curriculares pertinentes, tais como formuladas em Giroux (1997), Apple (2006), Moreira (2010) e Pacheco (2003). Como resultados, destacamos que as influências neoliberais sobre o documento, assim como a falsa autonomia dada aos docentes no processo de elaboração, resultaram na sua desvalorização como intelectuais transformadores.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: currículo; política curricular; conteúdos básicos comuns; ciclo de políticas; desvalorização docente

Esta investigación tiene como objetivo analizar los contextos de influencia de la producción del currículo oficial de la escuela de educación física del estado de Minas Gerais, los contenidos básicos comunes. Investigamos aspectos políticos, ideológicos y epistemológicos utilizando el método de ciclo de políticas de Ball (apud Mainardes, 2006) y un guión de entrevista no estructurado, aplicado a los elaboradores del tema de la propuesta curricular. Articulamos los datos a las teorías curriculares relevantes, como las formuladas en Giroux (1997), Apple (2006), Moreira (2010) y Pacheco (2003). Como resultado, enfatizamos que las influencias neoliberales en el documento, así como la falsa autonomía otorgada a los maestros en el proceso de elaboración, resultaron su devaluación como intelectuales transformadores. Esta investigación pretende analizar los contextos de influencia de la producción del currículo oficial de la escuela de educación física del Estado de Minas Gerais, el contenido básico común. Investigamos aspectos políticos, ideológicos y epistemológicos utilizando el método de ciclo de políticas de Ball (apud Mainardes, 2006) y un guión de entrevista no estructurado enfocado, aplicado a los elaboradores del tema de la propuesta curricular. Articulamos los datos a las teorías curriculares relevantes, leídas en Giroux (1997), Apple (2006), Moreira (2010) y Pacheco (2003). Como resultado, enfatizamos que las influencias neoliberales en el documento, así como la falsa autonomía otorgada a los maestros en el proceso de elaboración, dieron como resultado su devaluación como transformando a los intelectuales.

PALABRAS CLAVE: currículo; política curricular; contenidos básicos comunes; ciclo de políticas; devaluación docente

INTRODUCTION

According to Giroux (1997), the idea of understanding and accepting teachers as a true category of transformative intellectuals is under constant threat, which is evidenced in regular political periods by means of educational reforms commonly focused on curricula. Such reforms bring underlying “instrumental ideologies that highlight a technocratic approach to teacher training as well as classroom pedagogy” (Giroux, 1997, p. 158).

In the same direction, Apple (2006) argues that the settings of the educational system are more related to economic than intellectual aspects if most of the current educational research is correct. The knowledge acquired by schools through these reforms is not merely analytical, technical, or psychological, but mainly ideological. In other words, it results from the “research on what certain social groups and classes, in certain institutions and certain historical moments, consider legitimate” (Apple, 2006, p. 83, highlight in the original). According to the author, this knowledge is critically formulated to develop an individual who “strengthens or reinforces the existing institutional arrangements (generally problematic) in society” (Apple, 2006, p. 83).

Thus, we explicitly present the formulation of our research problem, defining our object of study and field of analysis, underlining the emergence of an educational scientific question, which can be investigated in a methodical, organized, controlled, and critical way, with results that can be empirically verified by an adequate instrument. Therefore, we ask the following questions: what aspects influence the production of a curriculum policy? How do these aspects impact the pedagogical practice and recognition of Physical Education teachers as transformative intellectuals (Giroux, 1997)? How do the epistemological reflections occur in the face of political and ideological issues?

Thus, the current research aims to analyze the official Physical Education (PE) curriculum issued by the Minas Gerais state: the Common Basic Contents (CBC). We intend to present some of the influences on its production, highlighting political, ideological, and epistemological aspects used in its construction, which reveal the organization of the educational policy that has contributed to the pedagogical devaluation of countless public teachers in the state.

As we aim to build a different way of considering PE at school, we need to understand its process of socio-historical construction in detail and identify the evidence of this process in its various contemporary forms, especially in official curriculum policies of this field. The relevance of this study is then justified by the high impact that a curriculum policy has on society. After all, as defended by Moreira and Silva (2008), curricula are artifacts that undeniably build social and pedagogical identities and, due to their institutionalization, absorb collective traditions that “result from identifiable economic and social ideologies” (Apple, 2006, p. 84).

METHODOLOGY

This is a qualitative study that aims to describe and analyze a social phenomenon: the curriculum policy for school PE in Minas Gerais, originally issued in 2005 during Aécio Neves’s administration. Since this is an analysis of the contexts of a public policy, which has impacted the education in Minas Gerais, this type of methodology is justified by the possibility of revealing ideologies, beliefs, and values from different points of view, guiding the description and interpretation of these phenomena (Latorre et al., 1997 apudRaimundo, Votre and Terra, 2012).

We have analyzed the context of the process of elaborating the CBC/MG for PE through the policy cycle method by Stephen Ball (apudMainardes, 2006), because we have considered the assumption that no curriculum reform can be analyzed without the interpretation of its elaboration context (Mainardes, 2006; Lopes, 2002; Pacheco, 2003). It is a methodological procedure regarded as an analytical model for educational programs and policies that takes into account their initial formulations as well as their evaluations.

This approach represents a way of considering the trajectory of a policy through a post-structuralist perspective that combines subjective understandings permeating analyses of the multiple contexts around the elaboration of the educational policy. It aims to evidence that political texts are open to many interpretations and that new meanings, even ideologies, might rise and be attached to them since the circulation of political documents enables new readings from one context to another.

Ball (apudMainardes, 2006) presents his theory based on different but interconnected contexts. It comprises five contexts: influence, text production, practice context, results/effects, and political strategy (Raimundo, Votre and Terra, 2012). We focused on the contexts of political influence and text production, which are involved in the elaboration of the object of research. We have examined these two steps through the lens of relevant contemporary curriculum theorizations, as seen in Giroux (1997), Pacheco (2003), Apple (2006), Moreira and Silva (2008), among others. We have chosen to analyze the category “devaluing and deskilling teacher work,” as shown by Giroux (1997, p. 158). Under this guideline, we will describe the contexts of the educational reform that resulted in the CBC for PE in Minas Gerais, as well as its repercussions based on relevant theories and analysis of speeches from the CBC developers.

The context of influence (and political strategy) is related to the moment in which interest groups establish standards and principles that have the function of guiding politics. In this phase, constant struggles for political discourses (powers) take place.

It is in this context that interest groups compete to influence the definition of the social purposes of education and what it means to be educated. Social networks inside and around political parties, the government, and the legislative process are active in this context. It is also in this context that the concepts acquire legitimacy and form a basic discourse for politics. (Mainardes, 2006, p. 51)

The context of political text production is characterized by the elaboration of a text that aims to show what politics is to the school community. It is an essentially bureaucratic context that depends on laws, rules, and regulations, also involving disputes. To Mainardes (2006, p. 52):

these representations can take various forms: official legal texts and political texts, formal and informal comments on official texts, official statements, videos, etc. Such texts do not necessarily have internal coherence and clarity, and they can also have contradictions. [...] Politics is not made and finished in the legislative moment, and the texts need to be read considering their specific time and place of production.

As an instrument to investigate contexts and data collection, we have elaborated a guide for focused unstructured interviews, which has been used with central developers of the curriculum proposal analyzed, following the orientation by Marconi and Lakatos (2010). Each one of the four meetings with the four developers, that took place between interviewer and interviewee separately, without any kind of intervention, lasted from 90 to 120 minutes on average.

Next, we present the description of the mentioned guide for the interviews:

Personal presentation: full name/age, academic qualification (undergraduate and graduate), and professional history (major points and current occupation);

Conversation about the undergraduate period. Why have you studied PE? (remarkable memories, preferences, subjects, important professors, physical practices and/or experiences, researches, trips, congresses, etc.). Discussion about the pedagogical aspects of PE in their formation courses;

What do you understand by curriculum? Curriculum theories and their authors represented in the CBC. General epistemological assumptions and epistemological positioning of PE;

How did the invitation to elaborate the CBC/MG for PE happen? Participants. Professional occupations of the group;

How was the dynamic and what were the procedures to elaborate the CBC? Steps. Organization and workplace;

Do the participants know the previous curriculum documents for PE in Minas Gerais? Past influences;

The Renewal Movement of Brazilian PE and its influence on CBC;

Organization of the four thematic axes of the CBC for PE;

Groups of professional development (GDP) in the PE field in Minas Gerais;

Political educational context in Minas Gerais and Brazil when the CBC was elaborated.

The individuals’ academic profile is highlighted as follows: all of them have an undergraduate degree in PE and a doctoral degree in education and have taught for at least 30 years in formal contexts. Though publicly known, their names were preserved during the analyses in order to avoid eventual embarrassments from some of their statements, thus respecting ethical precepts. Therefore, the order of presentation of the individuals as described during the analyses of the answers, represented as interviewees 1, 2, 3, and 4, does not correspond to the chronological order of the meetings. We emphasize that all interviews happened with the individuals’ agreement, and all of them signed an informed consent form.

In the structure of this work, we have developed an analysis of the context of political influence on the CBC for PE in schools, showing how large international liberal corporations invested in Brazilian education in the 1990s and 2000s and the implications of this process in the elaboration of the educational policy in Minas Gerais. Next, we have underlined the influences from the context of political text production and the Professional Development Program (PDP), a moment in which schoolteachers were invited to participate in the elaboration of the political text. We have demonstrated the flaws of their participation, their false autonomy, and the devaluing of their category, highlighting statements by the individuals interviewed. Lastly, we have listed the final considerations of the study.

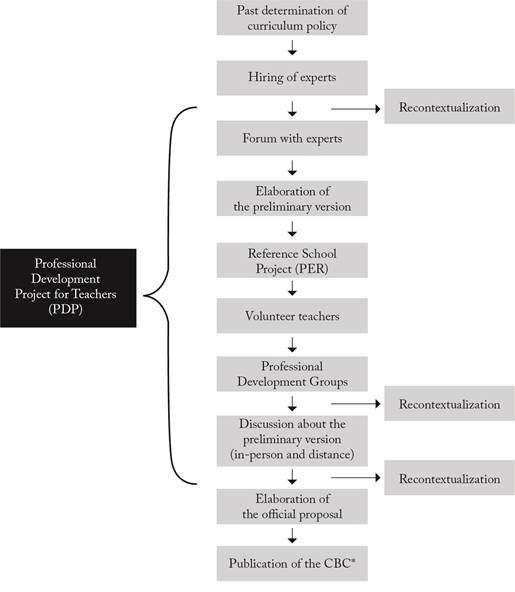

In Figure 1, we reveal the scheme (and hierarchy) of the elaboration flow of the curriculum policy for PE in Minas Gerais and identify its moments of recontextualization. The final curriculum resulted from a long political and ideological process, thus consolidating the point of view that it is a consequence of a complex and concatenated social organization (Sacristán, 2000).

CONTEXTS OF INFLUENCE ON THE COMMON BASIC CONTENTS FOR PHYSICAL EDUCATION: POLITICAL, IDEOLOGICAL, AND EPISTEMOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS

We present our interpretation of the Minas Gerais educational policy, considering the whole 1990 decade up to the CBC issue date in 2005 when the curriculum proposal in question appeared. We reiterate that a curriculum policy cannot be understood out of its elaboration context (Sacristán, 2000; Lopes, 2002; Pacheco, 2003; Neira and Nunes, 2009). In this sense, every study that aims to advance our understanding should consider that “the curriculum policy rules general decisions and is manifested by a certain legal and administrative ordering” (Sacristán, 2000, p. 107). Thus, disregarding the real context in which the object is immersed, processed, and manifested means neglecting the understanding of the reality we aim to explain.

It is imperative to emphasize that, for the last decades, the Brazilian educational system has been endeavoring to achieve the universalization of Brazilian Basic Education and the idea of quality has been guiding the debates on educational policies, which currently culminate in the elaboration of the Common National Curricular Basis (BNCC1). It aims to reach the levels of developed countries, following the standards defined in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). This purpose is defended by Law number 9,394/96 (Law of Directives and Bases - LDB), which provides a national process to evaluate school performance in partnership with the state and municipal education systems, considering some priorities and ensuring quality.

This perspective of qualitative profit in Basic Education was already adopted by the Brazilian policy in effect during the 1990s, a period in which “the Brazilian government promoted educational reforms in all levels of education” (Nunes, 2016, p. 26). This was an idea defended in international discourses on education during the Jomtien World Conference on Education for All, which resulted in the World Declaration on Education for All, highlighting the need for developing countries, such as Brazil, to offer quality education. This meeting resulted in many inclusion initiatives, actions to reduce grade retention, and projects for national education, some of which were prominent in Minas Gerais.

That was the broad influential context before the CBC, in which the education perspective that would guide local policies was discussed. From the Thai conference, Brazil elaborated: the Decennial Plan of Education for All (1993-2003), which mobilized government, civil society, states, and cities; Strategic Policy Plan (1995-1998), which established a commitment made by the country that aimed to expand and improve the quality of teaching; the Fund for Maintenance and Development of Basic Education and Valorization of Teaching (FUNDEF), which was also implemented. Lastly, the LDB/1996 also focused on the quality of teaching and the correction of school flow (Raimundo, Votre and Terra, 2012).

Consequently, this set of laws and plans “followed the global orientation to reorganize neoliberal politics, presenting the principles of administrative and managerial reforms in schools, creating mechanisms for regulating the efficiency, productivity and effectiveness of education” (Raimundo, Votre and Terra, 2012, p. 851). Also according to the authors, “the influential context of educational reforms, especially in Minas Gerais, disseminates the neoliberal perspective, influencing the definition of policies and priorities that serve the market logic” (Raimundo, Votre and Terra, 2012, p. 850).

The neoliberal idea is also related to meritocracy and seems to correlate distinctive curriculum policies as having the same characteristics and functions in different places. It would be a type of strategy reinforced by globalization that implies that this is the only way to achieve progress. According to Pacheco (2003), this position is usually present in discourses that support recent curriculum policies, a phase that promoted the idea that private is superior to public.

In the 1990s, schools adopted the most elementary characteristics of neoliberal ideas. In other words, market conceptions became linked to education due to the transposition of the corporative managerial model to schools and also for political and administrative decentralized practices, carried out to establish democracy. Nunes (2016) adds that, in this period, the country had its local economy working “as a unity of the world economy” (Nunes, 2016, p. 27), being forced to adjust to deregulated global dynamics. The author affirms that “the State becomes incompetent, and the market logic starts to solve social issues. Therefore, the State becomes subordinated to the economy” (Nunes, 2016, p. 27), turning education into merchandise. This is also represented by the idea that the commodification of knowledge and education makes the State cease to be the provider to become just the assessor (Ball, 2004).

Reinforcing the analysis of the Brazilian education in this period, Caparroz (2003) highlights that the implementation of policies, such as the National Curriculum Parameters (PCN), depended on funding and determination from international institutions (World Bank, International Monetary Fund - IMF, United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization - UNESCO), which had been “dictating worldwide rules, based on the neoliberal conception, for educational policies, and imposing rules that [should] be followed and obeyed in order to obtain resources for the educational field” (Caparroz, 2003, p. 310).

Nunes (2016) also states that, in the 1990s, the goal established by international organizations (IMF, Inter-American Development Bank - IDB, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development - IBRD, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development - OECD) was to overcome poverty, with these institutions assuming “the role of ministries of education, [...] interfering (implementing) in policies for basic and higher education” (Nunes, 2016, p. 27-28). Lopes (2002) complements it by emphasizing that all these organizations invested large amounts of money in high school reforms all over the country.

We present excerpts from the interviews to expand the analysis, aiming to identify how the organizers of the CBC for PE understood the political context of the period in which the document was elaborated. The statements testify to how the recontextualization process offers a proper space for ideological insertion:

Interviewer: How do you interpret the educational political context of Minas Gerais and Brazil at the time the CBC was elaborated?

Interviewee 2: It’s very funny, because when they called us to take part in it, someone from our group, with a more critical view on Physical Education, said: “Don’t you do a project for Aécio Neves.” Do you get it? [And I said:] “For Aécio Neves? No, I’m not doing a project for Aécio Neves, I’m making a project for the Brazilian and Minas Gerais people, for the children.” What I think is this, if you throw stones and say: “No, I’m not going to do this because that guy belongs to that party,” then you don’t have a way to intervene. That’s what I believe, you know? For instance, I strongly believed in the Secretary of Education [as] a person, but of course, it was a PSDB2 administration, which had another political perspective. But it doesn’t matter, what matters is someone willing to do good, advance the school.

Nunes (2016) argues that decontextualization is usually the first stage of recontextualization, “because some texts are selected to the detriment of others, while social questions and relationships from other social spheres are brought into focus” (Nunes, 2016, p. 38). According to the author, this promotes some kind of “repositioning of opinions given the State discourse, structuring the field of recontextualization. Amidst these conflicts, the ideology action and the hybridization of discourses gain space” (Nunes, 2016, p. 38). In the following excerpt, we observe how this argument is reinforced:

Interviewee 4: We thought carefully about it, we problematized this question a lot, if we were going to assume this movement, mainly because we were, especially me, against the administration [PSDB] at that time. But [...] we considered that we could make a great contribution to a more critical Physical Education in the Minas Gerais State and, probably, if another group assumed it, it could become another proposal. At that moment, few professors from UFMG [Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais] had been invited, and they hadn’t assumed it exactly because of the political issue, and we completely understood, right? That was it [...], it could get in the hands of another Physical Education group, professors with another conception. [...] After all that we had to answer, it seemed like we were from the government when you see [their] seals in the documents and whatnot. [...] Then we had to go to many forums to explain it to our fellows because it seemed like we were from the government and it was not like that.

Lopes (2002) asserts that a set of general policies, implemented with different intensities, is always subject to processes of hybridization due to their subtleties and variations when facing recontextualization. From the answers, we can infer that, despite having followed the thread of political coherence presented by the Secretariat of Education, it was the contextualized debate that made the space for a new ideological intervention (from the group of specialists). At that moment, the discourse was displaced from one position to another, changing the decision-making, and rules for social order were created, even though they had “good intention.” We can notice that the individuals interviewed saw party affiliation as correlated to “doing good or evil.” Since central power belonged to PSDB, they needed to intervene in some way, i.e., the way considered by the group as ideologically better, the “good” one.

There is a strong subjective component linked to the most “passionate” conceptions followed by the consultants, a type of Manichaean partisanship endorsed by the group. Thus, the input of ideology into the pedagogical discourse brought an aspect of misrepresentation to the process of recontextualization, due to its detachment from the discourse of political reference, initially considered valid (Ball, 2001). In Pacheco’s words (2003, p. 10-11):

In fact, curriculum is central to the debate on educational issues. Curriculum is a mandatory theme in the political agenda of various governments, legitimized by different ideologies. Curriculum, curriculum policies, and education are treated with passion: [...] something that makes us sensitive and turns us into actors of a will.

In this path of political and ideological influences, the curriculum proposal (Minas Gerais, 2005) indicates that the consultants debated the laws, official national documents, as well as different educational and curriculum theories that promoted the control and regulation of the PE field in schools at that time.

In addition to the LDB/1996, the National Curriculum Guidelines for basic education, established by the National Council on Education, assign to Physical Education the same value as other curriculum components, abandoning the notion of it as a mere activity devoid of educational purpose (as in the legislation issued in 1971), and it begins to be considered a field of knowledge. [...] The National Curriculum Parameters (PCN) also define Physical Education as the curriculum component responsible for introducing the individuals to the universe of body culture, which encompasses multiple skills developed and put into practice by society in relation to body and movement (Minas Gerais, 2005, p. 15).

The dialog observed in the interviews also reveals the importance of influential documents such as PCN, even when they do not stand out, because the consultants unfold different memories from the process.

Interviewee 2: But I think that it [the CBC] was much more influenced by this (pointing at some books that she brought to the interview), the things that were happening in the world of Physical Education, you know? The discussion from the CBCE [Brazilian College of Sports Sciences], then, this critical view on Physical Education. [...] We read the PCN, I actually participated in those ad hoc, right? [...] The PCN reflected everything that was happening in Physical Education at that time. More or less, then, this way, I think it helped in giving us a reference.

Interviewee 4: For sure. In fact, they are the main reference, right? For us, at that moment, not only the law but also the parameters and guidelines. We worked very close to these proposals.

Interviewer: Do you mean LDB, PCN, and DCN [National Curriculum Guidelines]?

Interviewee 4: Yes.

As the “PCN for Physical Education is presented as a device built based on multiple approaches” (Caparroz, 2003, p. 327), we consider that the neoliberal view on technical efficiency and production of skills and abilities would not be ignored by the Minas Gerais group. PCN stands out as a support element for CBC, funded by foreign corporations. Despite the consultants’ attempt to work with the critical conceptions of PE, as we infer from the interviews, the neoliberal trace of previous investments engendered by large corporations marked the construction of the policy. As claimed by Apple (2006), many liberal educational reforms “tacitly served social and conservative interests for stability and social stratification” (Apple, 2006, p. 86).

As shown in the presentation of the document, the words from the secretary of education at that time corroborate our understanding that, overcoming the developers’ critical attempts, the CBC for PE favored the idea of maintaining the social status quo supported by the neoliberal perspective on efficiency and performance, which aimed to insert the students in a market already stabilized and stratified:

Establishing the skills, abilities, and competences that basic education students should acquire, as well as the goals the teacher must achieve in each grade, is an indispensable condition for the success of any school system that intends to provide quality educational services to the population. The definition of common basic contents (CBC) for the final grades of elementary and high school represents an important step towards turning the Minas Gerais State education network into a high-performance system (Minas Gerais, 2005, p. 9).

Apart from political and ideological aspects, the PE curriculum field in that moment of the reform in Minas Gerais was already under the epistemological influence of critical theories, as we observe in correlated publications (Rocha et al., 2015) and the statements of the interviewees, who intended to create a certain rupture with traditional hegemonic ideas in this field3. Their declarations reveal a clear effort to give the document a less reproducible aspect. However, we can infer that there was some kind of epistemological disconnection in the conceptual predetermination to organize the document during the first recontextualization, which helped maintain some gaps. Although the individuals adopted various critical assumptions - notably based on Marx -, other influences were also observed.

Interviewer: What can you say about the Renewal Movement of the Brazilian Physical Education? Did this movement influence how the CBC group developed their work? In what sense? Which books and works were used? How were these ideas represented in the CBC?

Interviewee 1: Particularly, I don’t remember much about it. [...] I don’t remember this expression. [But I remember] the concept [of Physical Education] as an intrinsic part of the pedagogical content of a school [...]. We began to understand Physical Education as a field of knowledge. That’s what I think was the ace in the hole for us to systematize knowledge, establish a curriculum.

Interviewee 2: We [were] immersed in this, in this so-called “renewal” movement, right? So, let’s see. By immersed I mean, I think this comes from, for example, from the early 80s, let’s say, in 1984 Medina’s book was already discussing: Physical Education takes care of body [and mind]. Next, Kunz’s works were released and helped a lot. The João Batista Freire’s books, they came [and] we were describing it with a more psychological view, right? I guess works by Valter Bracht and the “Author Collective” [...], Kunz with his idea of “moving.” And we also have Mauro Betti’s output.

Interviewee 3: Well, in fact, this “renewal” movement encompassed all fields, didn’t it? [...] So this was the source from which we took our ideas, to which we identified ourselves and recognized our experiences, and which we brought to this proposal, to the pedagogical guidelines, right? Everything else that we produced was related to that root, that group with more progressive thinking [...]. And then we realize there was a dispute to occupy this place [...] that [previously] belonged to a more technical Physical Education, a Physical Education more focused on results [...]. This view, this [critical] perspective on school education, focused on the student, we managed to sneak in it.

Interviewee 4: That is exactly the proposal, right? Then, of course, the classic works. The Collective, Jocimar Daolio comes to strongly discuss the concept of culture, right? [...] Collective texts, the ones by Bracht. [...] Elenor Kunz, Didactic-Pedagogical Transformation, Teaching and Change, the ones on history, those by Carmem Lúcia, Mauro Betti.

From the answers, it is possible to recognize the clear influence of various authors from the Renewal Movement4 in the field, but it is imperative to emphasize that we did not identify meaningful evidence of them in the document, which presents few quotations by the authors mentioned in its theoretical framework, without any practical unfolding. We should note the following statements:

Interviewee 3: So, this is very nice. This is good. So, we were really taking these [critical] authors, engaging with them, and appropriating [their work].

Interviewer: Now, there was a disagreement with more traditional perspectives, such as sports training, rules and tactics training, it’s clear in the others.

Interviewee 3: Yeah, but what happens next? Then, that’s what I say. These “theoretical landmarks” are one thing. Another thing is how they become class. That’s the question.

These data lead us to confirm the difficulties and obstacles that all critical theorizations gathered spread over the development of PE in schools. It would seem strange that the consultants knew the critical theorizations but did not use them while organizing the document if we did not also recognize the strength of the political and ideological influence of instrumental and economic intents previous to the process of elaboration. The neoliberal political influence from the 1990s and the Marxist pragmatic difficulties were enough for the development of skills and abilities intended for the market to prevail and persist. According to Apple (2006), it is crucial that we consider the debates on educational policies in their broader historical context, because, without it, we cannot fully understand the relationship between what schools actually do - guided by educational policies - and the more extensive aspect of economics, particularly the one related to the Minas Gerais neoliberal context.

In addition, concerning critical theorization issues, we agree with the arguments by Neira and Nunes (2009) when they explain that, for the last 30 years, critical theories have not succeeded in presenting practical and compelling basis for showing to the academic community how to develop a critical PE successfully in schools by means of human moving. They explain that “not all curricula [...] respond to the social function the school has been assuming in contemporary times, that is, forming citizens to critically act in public life, with the purpose of building a more democratic society” (Neira and Nunes, 2009, p. 92). Thus, despite the existence of studies that aim to highlight the social and philosophical debate in the field, there is no consensus yet among the scholars on PE being part of both Human and Biological Sciences5. The authors go on to reveal that “teachers are seduced [by] old promises” (Neira and Nunes, 2009, p. 92) historically built in this field, founded on other areas of science, on which they base their pedagogical interventions. Customarily, “the analysis of the same [school] education plan shows conceptions and proposals that conform to different approaches: developing agility, enhancing motor coordination, promoting critical positioning, or improving physical conditioning” (Neira and Nunes, 2009, p. 92).

Epistemologically arguing about the real possibilities of a critical curriculum theorization seems to be a crucial point for contemporary PE. In addition to the pedagogical guidelines described in the Author Collective (1992), a reference critical work in the field, very little has been done since then to form a critical curriculum principle, “as all formal curricula [...] involve and indicate control purposes” (apudMoreira, 2010, p. 91). What Moreira (2010) discusses concerning the “hidden curriculum” is also combined with the problem in focus, because critically managing issues about hierarchies and power, school rituals, rules, aspects of school space and dynamics, among other things, does not seem easy to solve. We finish this section by quoting Moreira (2010, p. 90-91):

Little has been achieved in terms of transforming curriculum theories into concrete proposals. Critical authors avoid more defined guidelines, making professors and experts in curriculum need a high degree of creativity to operationalize what they can understand from the dense and complex texts elaborated by those authors.

Lastly, one of the interviews eventually revealed the clear impact of this critical curriculum theorization on schoolteachers. In the following excerpt, the data almost speak for themselves. The same interviewee demonstrated a fundamental contradiction. Has the CBC proposal for PE been enriching for teachers? Have they understood how to perform their pedagogical work better based on the critical theory? We can observe the incoherence in the following statements:

Interviewee 4: But whoever worked with the Common Basic Contents, and still works with them, always gives us this feedback, that it was important, it organized their mindsets and so on.

Further on, in another moment of the same interview:

Interviewee 4: The teachers themselves reported that the proposal was beyond what they could understand, what they comprehend. Even in the written form, right? They could not understand, you ask me what Body Culture is, for example, they could not comprehend what was being said. Many of them were saying, “it’s very pretty, very beautiful, but it’s not for us, right?”.

CONTEXT OF POLITICAL TEXT PRODUCTION: THE PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM FOR TEACHERS

Advancing the analysis, as noted on the website of the Minas Gerais State Secretariat of Education6 (SEE-MG), one goal of the set of educational policies established by Aécio Neves’ administration was to improve public schools, recovering their excellence. To this end, the Reference School Project (PER) promoted educational subprojects with specific targets, but that complemented each other.

Three subprojects were created - the PDPI (Project of Pedagogical and Institutional Development), the PROGESTÃO (School Management Project), and the PDP (Professional Development Program for Teachers), under the responsibility of teams formed in intermediate management instances, the Regional Boards of Education (SRE) - and, inside the schools, they should complement the elaboration of a plan setting goals and actions that educational institutions should develop with the support of the SEE-MG (Rezende and Isobe, 2011, p. 73).

Accordingly, we have analyzed the elaboration and implementation of the Professional Development Program for Teachers (PDP), which represented the conception of teaching training following the State standpoint at the time of the curriculum reform in Minas Gerais, understood as one of its main axes (Rezende and Isobe, 2011). In the PDP, the Professional Development Groups (GDP) were formed, comprising public school teachers, who were attending a qualification course with CBC organizers, aiming to reflect on the contents of school PE as established in the proposal. There was the possibility of some teachers intervening in the document, according to local realities; however, our analysis reveals the flaws of this false process of decentralization, which has also led to a false autonomy and a clear depreciation of schoolteachers. We should keep in mind that decentralization “is not a local achievement, but the result of national policy: it was desired, defined, organized, and put into practice by the State” (Charlot, 1994 apudPacheco, 2003, p. 95).

PDP aimed to optimize the works done by the CBC, being partly responsible for developing the curriculum policy. In the PER context, the CBC was articulated with school practice by means of the debate between the consultants (the interviewees in this research) and the PE teachers of the mentioned state schools. It was an intense text production that seemed to involve some community but presented significant gaps. In the excerpts of the interviews, we confirm its importance as a crucial step in the policy flow, bringing together the PE teachers who belonged to the schools selected.

Interviewee 1: We had [nearly] 200 teachers and 200 reference schools. And professionals of different fields from these schools had to be qualified for this. And then the structure was the following. There were 200 schools and four of us [coordinators]. We divided the schools, [with nearly] 50 schools per consultant. We sent this to them [the teachers]. They received this content. And then they had to give it back. And then, step by step, we stratified it in several meetings: principles, contents, competences, and abilities. We used to go to [the hotel] Canto da Seriema and had some time [to debate]. We sent e-mails [asking]: “What do you agree with? What do you suggest? What would you change?” So, we talked with the [school] teachers. [...] And they had some time and got back to us. We summarized these propositions. And after analyzing this feedback [we’d get back to the hotel]. Thus, it was a collective construction.

The meetings that resulted from the creation of PER were crucial for the elaboration of the State curriculum policy. This administration initially selected some schools to participate in the process, considering efficiency and competence development as significant quality indicators. According to the SEE-MG website, “all schools that [had] high school students [would receive] funds [...], but those participating in Reference Schools would be included first.”

The SEE-MG indicates that, in the first stage, the project aimed to cover 102 cities, 337,4 thousand students, and 10,8 thousand teachers, and the 213 first schools were selected in accordance with specific criteria, namely:

localization in cities with more than 30 thousand inhabitants;

with more than one thousand high school students.

Aiming to stimulate the exchange of experiences, each school designated another one with which it could associate in order to transfer the benefits and knowledge acquired through the PER. The principals received forms in which they made diagnoses presenting the necessity for material investment. Throughout the stages, education professionals who worked in state schools were trained, infrastructure was improved, equipment was acquired, and so on. In the Secretary of Education’s words7:

This is a select group of schools that will have a fundamental task in the public educational system of Minas Gerais. The main interest is in students’ learning, and the current challenge is to have a competent public school, able to change young people’s lives. The expectation is for the whole system to improve after this and other projects. This is not a mere investment program, its purpose is to enhance student performance.

Before the organization by subjects, there were meetings that composed a regular forum, held within the precincts of the SEE-MG. The forums on professional development (FDP) were prior meetings between only the government and experts, characterizing a recontextualization and hierarchical decision-making.

Interviewee 4: The forum, it was organized under the coordination of the secretariat and with all experts of all fields. And then we’d discuss how this could be done, how this material could be made and so on, right? We’d have a meeting, maybe every couple of weeks, every Monday afternoon over there in the secretariat, with all experts and consultants, for us to discuss this general material from all subjects. After that, each subject would organize its own GDP, the [professional] development groups.

It is important to emphasize that, during the interviews, we observed how the process had been conducted hierarchically and how certain epistemological and political decisions had been organized, which presented a previously “ready” and closed structure, which demanded standardized documents from the group responsible for its elaboration.

Concerning the organizational structure of the Physical Education subject throughout Basic Education, the State Secretariat of Education defined the Common Basic Contents (CBC) following the LDB guidelines, [with] relevant and necessary contents for the development of competences and abilities considered indispensable to students in each school level. Therefore, they should be mandatorily taught in all state schools in Minas Gerais (Minas Gerais, 2005, p. 31).

However, we can infer that the consultants had some autonomy to develop the text of the document, which occurred before the dialog established with the state school teachers. Nevertheless, the curriculum policy was not reduced to the original text, since the state was the first to theorize, followed by the experts. According to Pacheco (2003, p. 15), the initial texts coming from the government

are work documents that symbolize the official discourse of the State, gathering different interests and alliances elaborated in several levels of action. However, they are macropolitical texts inserted in a line of technical rationality when the contexts of political microdecision are marginalized. Thus, we can recognize that curriculum political decisions are fragmented and multicentered.

The interviews reveal the differentiation between macro- and micro-political decisions. In the context of macro-policies, aspects of the powers expressed by the documents and in the text production are questioned, socio-economic groups and their influences are identified, as well as the government function, understood as a complex structure. Regarding micro-policies, schools, teachers, and students have a role in shaping the practical curriculum, namely, the elements that are not directly controlled by the government (Pacheco, 2003). In the author’s words, “the practice is sophisticated, uncertain, complex, and unstable, which means to say that this plan presents power structures, informal decision networks, and discourse practices that actively intervene in the curriculum decision” (Pacheco, 2003, p. 16).

Interviewee 1: We received the guiding document for the CBC from the State. And they had already prepared everything. What they wanted, where they wanted to go. So, they were like “look, we must have an introduction.” And then they showed us what other subjects had already done. They gave us one that was already underway and said, “look here, it’s more or less like this, but you have to adjust it to the Physical Education content.” So, they had a script. Everything was standardized. Every subject had the same elaboration pattern.

Interviewee 2: It was like this: our first task was to elaborate a base text. So, they gave us a script. [...] It must have an introduction; it must have the reasons to justify Physical Education in school. So, we spent some time writing this document. What was the second step? Writing the document. This was for the so-called reference schools, they picked 220 schools in Minas Gerais [to carry out the PDP in them].

The foundation for epistemological and technical decision is attributed to experts. This group prioritizes the contents, the history of the field, and its planned organization, while their political positions are ignored, preventing the category from having more qualitative and critical participation. The curriculum becomes an instrument brought to the classroom and tested on students, “regarded as a product offered and not a project that must be understood, interpreted, and transformed” (Pacheco, 2003, p. 26). In the same direction, Giroux (1997) argues that government policies impact the current educational scenario in the world, suggesting “reforms that ignore the intelligence, judgment, and experience that teachers could provide in such a debate” (Giroux, 1997, p. 157).

After this elucidation, we underline that the State power does not need to adopt explicit forms of coercion when assuming a predetermined and closed curriculum policy, used as a domination measure that helps establish/preserve a specific discourse as hegemonic. In other words, if the school remains an uncritical reproducible institution, it becomes part of this opportune mechanism of ideological maneuvers and interests in maintaining the status quo.

The GDP also worked as articulation nuclei of the PDP and aimed to plan curricular activities, bringing teachers together, usually by affective and intellectual affinity (divided by themselves). The SEE-MG established a workload of 180 hours divided between in-person and distance modules for the working groups to plan the implementation of the CBC. It is noteworthy that many teachers do not like having to follow new rules imposed by institutional hierarchies, especially in a context already worn out by strikes, claims for better salaries, lack of structure, etc.

Interviewee 3: At that time, the teachers had a huge grudge against the state because of their salaries [and other conditions]. So, they would go there slightly upset, thinking that we were from the secretariat. So, first, we had to say that we weren’t from the secretariat, that we were there willing to help and that, even though they were unhappy with the whole situation, they had to understand that [the moment] would be important for their formation.

In the case of the CBC, we should add that the participating schoolteachers were not paid for their new task. However, the contents would be mandatory in all Reference Schools, and the teachers who had been part of it initially would act as “disseminators” of the ideas discussed in the GDP.

Interviewee 2: Because this was determined by the secretariat: “get together in the best way you can, but you need to have a coordinator, a rapporteur, etc.” [...] And those people were really working voluntarily, because they weren’t paid overtime or anything to do the job, right? But the idea was groups that could have some affinity, with nothing compulsory, and that were willing to discuss things together.

Interviewee 4: If my memory serves me correctly, there were more or less 220 reference schools, and then it seems that the teachers volunteered to work, right? Now I don’t remember if they received anything for it, but they surely had a lot of work. And then what was the movement? We’d make, we’d discuss internally, the fours of us, and we’d send [by e-mail] tasks to the schools, and the “reference teachers” would discuss with their peers, answering those questions we had asked and sending them back to us. And then we’d give them back to the teachers, so this was the come-and-go movement, which was very enriching, for sure, because we couldn’t listen to all schools, could we? Two or three thousand schools at that time, but in a certain way, the teachers were valued in this movement for us to elaborate. So, this was very fruitful.

Teaching devaluing seems to be implicit, but it becomes emblematic in the context. The teacher was not required to participate, but when contributing to the project, he or she would not be recognized in the pro labore. It is a “labor exploitation” proposed by the secretariat, which Giroux would call “proletarianization of teacher work” (Giroux, 1997, p. 158). The goal was to cut expenses, but with a remarkable increase in workload for most participants, namely, those more vulnerable in the pedagogical process and more likely to lose in the political power struggle. The government hired the project organizers, paying their salaries, but ignored the importance of financially valuing the extra effort of those who best know the necessities of the school and who need material and intellectual stimulus the most8. To Giroux (1997, p. 158), it is imperative to reveal and

examine the ideological and material forces that have contributed [...] to the tendency to reduce the teachers to the status of specialized technicians within the school bureaucracy, whose function then becomes one of managing and implementing curricular programs rather than developing or critically appropriating curricula to fit specific pedagogical concerns.

It is worth making a second comment about a statement by interviewee 4 when she affirmed that the debate by means of virtual mail had been “very enriching.” However, we ask ourselves: “enriching for whom?” Because the expert herself highlighted that they could not listen to all suggestions, and next she argued that “in a certain way the teachers were valued.” This is what Giroux (1997) would call the proliferation of “teacher-proof curriculum materials” (Giroux, 1997, p. 160), attributing to teachers the mere role of reproduction and implementation.

We argue that the central power merely aimed to maintain the hegemonic situation, only paying the experts that, supposedly, should contribute to the interest of the state, “whose social function is primarily to sustain and legitimate the status quo” (Giroux, 1997, p. 197). Besides believing in a transformation, many volunteers who accepted this work intended to mitigate possible future demands coming from the proposal, whether practical or bureaucratic, which could increase their already huge work demand and damage the teaching even more. We identify a veiled control discourse by the central power, a certain threat diluted in the process, inserted in educational reforms that show little confidence in the ability of public school teachers in offering intellectual leadership to young people. In the analyzed case, the teachers were not required to participate if they did not want to, which seems even democratic, but they would have to apply what was predetermined. To Giroux (1997, p. 157),

where teachers do enter the debate, they are the object of educational reforms that reduce them to the status of high-level technicians carrying out dictates and objectives decided by experts far removed from the everyday realities of classroom life. The message appears to be that teachers do not count when it comes to critically examining the nature and process of educational reform.

The organization of the GDP in the format described shows that the volunteer teachers worked only as less relevant pieces, instead of being welcomed as transformative intellectuals in the elaboration of the proposal, which should have been structured according to much more critical aspects. This is what Giroux (1997, p. 163) calls “making the pedagogical more political and the political more pedagogical,” a condition that he regards as fundamental to understand the teacher as a transformative intellectual. First, schooling should be inserted in the political sphere, considering its praxis as part of a project against economic, political, and social injustices. Second, work should be done in favor of emancipation, making knowledge problematic and using critical and affirmative dialog to question what type of society is the best for everyone.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Our work has aimed to discuss the influential contexts existing in the flow of the curriculum policy for PE in Minas Gerais. Based on the Policy Cycle methodology, we have described the contexts and stages of recontextualization, all of them marked by significant ideological and subjective elements that contributed to the devaluing of teachers.

First of all, the inspiration in the PCN and the support of large neoliberal corporations for the education in Minas Gerais since the 1990s - which established goals of productivity, efficiency, effectiveness, and evaluation for the school, understood as qualitative mottoes of neoliberal thinking - created a meaningful space for the ideological influence of market in the flow of politics. The educational policy was reinforced to primarily assist the central political power and the business community to the detriment of actual pedagogical needs to support teachers and students.

Secondly, within all political contextualization, we have presented elements of epistemological influence resulting from the analysis of the interviews, as well as the relevant literature (Neira and Nunes, 2009; Moreira, 2010), emphasizing all difficulties faced by critical theories to consolidate a curriculum policy based on Marxist premises.

A third aspect concerns the false prerogative of autonomy attributed to school institutions by the central power, confirmed by the low involvement of PDP schoolteachers, unable to express themselves adequately, due to the small number of meetings and the lack of any financial incentive from the government for them to do their intellectual work. Teachers were seen as mere disseminators of a predetermined curriculum political structure, which also represents a rapid and fragmented flow of recontextualizations. Rezende and Isobe (2011) corroborate and identify the teachers’ feelings towards the numerous reforms, guidelines, and bureaucracies that interfere in their pedagogical practice:

Defined by economic interests unconnected with what happens in the school routine, the continuous reforms, projects, and guidelines, which override the teachers and disorganize their “expertise”, make us skeptical about “pedagogical materials” and sterilize the school foundation, covered with discouragement, powerlessness, anger, and survival strategies that make them move away from their teaching purpose (Rezende and Isobe, 2011, p. 78).

The whole investigation encourages us to think about some challenges that could advance the research on curriculum policies. Beyond the necessity to explore other contexts of curriculum production, it seems evident that new analyses should consider the premises of the obstacles presented by critical theories to subsidize curricula for PE that are more consistent and even more pragmatic for the pedagogical practice in the field. One issue that draws our attention concerns the recent debates on “epistemology of practice” (Neira, 2018), that is, curriculum productions conducted based on the pedagogical practices of schoolteachers, which would contribute to a considerable revaluation of the teaching work neglected in the CBC. Such subject has been constantly discussed in the field through cultural studies and the categories used in post-critical theories, which actually seem to contribute to some advancement in this issue (Neira, 2018; Neira and Nunes, 2009; Barbosa and Nunes, 2014; Bonetto and Neira, 2017).

Similarly to a recent and relevant curriculum literature review (Rocha et al., 2015), we highlight the elaboration and implementation of curriculum proposals subsidized by critical and post-critical theories on the pedagogical practice of PE schoolteachers as a field for posterior studies to be developed, as well as “the exploration of how school skills have been systematized in the pedagogical practice” (Rocha et al., 2015, p. 191). To the authors, the biggest challenge seems to be favoring the teachers involved with the pedagogical practice of PE in school.

Giroux (1997) also brings meaningful reflections on the importance of considering the teaching category as intellectualized and capable of acting on the formulation of curriculum policies in a straight and incisive way. One of these reflections involves the idea of regarding schools as “economic, cultural and social sites that are inextricably tied to the issues of power and control” (Giroux, 1997, p. 162). In the author’s perspective, apart from conveying the objectivity of knowledge, schools represent skills, values, and practices singularly selected and extracted from a broader culture. They validate epistemology, policies, ideologies, and peculiar ways of understanding social reality.

It is clear to us that the result of the continuous curriculum reforms is the organization of the daily school routine according to experts in curriculum, instruction, and evaluation, “to whom the task of conception is attributed, while teachers are reduced to the task of implementation” (Giroux, 1997, p. 160). In the face of the analyses, we can infer that the debates that happened in moments of recontextualization have not been sufficient for a significant and qualitative implementation of the policy. The existing gaps among the initial political discourse, the experts’ discourse, and the understanding by the teachers who will reproduce this policy have been marked by recontextualizations immersed in strongly ideological aspects. Once more, the discussion about the importance of teachers’ local action has been left aside.

Therefore, the Minas Gerais politics shows a sensitive idea that alludes to “management pedagogies,” which neglect the participation of the schoolteachers. On the contrary, beyond the school walls, they should be actively involved with the production of pedagogical and curriculum materials suitable for the social and cultural contexts in which they teach (Giroux, 1997). Underlying the Minas Gerais policy in question, there is the notion that every student can learn and develop from the same material produced by a select group. The subjectivity inherent in the history and experience of each student is completely ignored in this type of pedagogy, which has a strong managerial aspect.

Finally, as we have already stated, this perspective naturally leads to the necessity of attributing political features to what is pedagogical or vice-versa. In other words, the critical reflection would compose the social project that education must assume in the struggle for equality and equity, as well as the individual process of humanization. Similarly, the educational policy should be able to provide the teachers, whom we consider transformative intellectuals, with the possibility of “using forms of pedagogy that embody political interests with an emancipatory aspect; [and] treat students as critical agents” (Giroux, 1997, p. 163), able to deeply reflect on the type of society they want to help build.

REFERENCES

APPLE, M. W. Ideologia e Currículo. 3. ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2006. [ Links ]

BALL, S. J. Diretrizes políticas globais e relações políticas locais em Educação. Currículo sem Fronteiras, v. 1, n. 2, p. 99-116, jul./dez. 2001. [ Links ]

BALL, S. J. Performatividade, privatização e o pós-Estado do Bem-Estar. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 25, n. 89, p. 1105-1126, dez. 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302004000400002 [ Links ]

BARBOSA, C. H. G.; NUNES, M. L. F. A prática pedagógica de um currículo cultural da Educação Física. Instrumento, Juiz de Fora, v. 16, n. 1, jan./jun. 2014. [ Links ]

BONETTO, P. X. R.; NEIRA, M. G. Multiculturalismo: polissemia e perspectivas na Educação e Educação Física. Dialogia, São Paulo, n. 25, p. 69-82, jan./abr. 2017. https://doi.org/10.5585/dialogia.N25.6624 [ Links ]

CAPARROZ, F. E. Parâmetros curriculares nacionais: “o que não pode ser que não é, o que não pode ser que não é”. In: BRACHT, V.; CRISORIO, R. (orgs.). A educação física no Brasil e na Argentina: identidade, desafios e perspectivas. Campinas: Autores Associados; Rio de Janeiro: Prosul, 2003, p. 309-333. [ Links ]

GIROUX, H. A. Os professores como intelectuais: rumo a uma pedagogia crítica de aprendizagem. Trad. Daniel Bueno. Porto Alegre: Artmed , 1997. [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C. Identidades pedagógicas projetadas pela reforma do ensino médio no Brasil. In: MOREIRA, A. F. B.; MACEDO, E. F. (orgs.). Currículo, práticas pedagógicas e identidades. Porto: LDA, 2002, p. 93-118. [ Links ]

MAINARDES, J. Abordagem do ciclo de políticas: uma contribuição para a análise de políticas educacionais. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 27, n. 94, p. 47-69, abr. 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302006000100003 [ Links ]

MARCONI, M. de A.; LAKATOS, E. M. Fundamentos de Metodologia Científica. 7. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2010. [ Links ]

MINAS GERAIS. Governo do Estado. Secretaria de Estado da Educação. Educação Física: Ensinos Fundamental e Médio (CBC). Proposta Curricular. Minas Gerais: Secretaria de Estado da Educação, 2005. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, A. F. B. Currículo e controle social. In: PARAÍSO, M. A. (org.). Antonio Flavio Barbosa Moreira: pesquisador em currículo. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2010, p. 19-94. [ Links ]

MOREIRA, A. F. B.; SILVA, T. T. da (orgs.). Currículo, cultura e sociedade. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2008. [ Links ]

NEIRA, M. G. Educação Física cultural: inspiração e prática pedagógica. Jundiaí: Paco, 2018. [ Links ]

NEIRA, M. G.; NUNES, M. Educação Física, currículo e cultura. São Paulo: Phorte, 2009. [ Links ]

NUNES, M. L. F. O mapa do território do ensino superior e da formação em Educação Física: emerge o criador. In: NEIRA, M. G.; NUNES, M. L. F. (orgs.). Monstros ou heróis?: os currículos que formam os professores de educação física. São Paulo: Phorte , 2016, p. 17-46. [ Links ]

PACHECO, J. Políticas curriculares: referenciais para análise. Porto Alegre: Artmed , 2003. [ Links ]

RAIMUNDO, A. C.; VOTRE, S. J.; TERRA, D. V. Planejamento curricular da educação física no projeto de correção do fluxo escolar. Revista Brasileira de Ciências do Esporte, Porto Alegre, v. 34, n. 4, p. 845-858, dez. 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-32892012000400004 [ Links ]

REZENDE, V. M.; ISOBE, R. M. R. Formação docente no ensino médio: a perspectiva do Programa de Desenvolvimento Profissional em Minas Gerais. Debates em Educação, Maceió, v. 3, n. 6, p. 70-84, ago./dez. 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.28998/2175-6600.2011v3n6p70 [ Links ]

ROCHA, M. A. B. et al. As teorias curriculares nas produções acerca da educação física escolar: uma revisão sistemática. Currículo sem Fronteiras, v. 15, n. 1, p. 178-194, jan./abr. 2015. [ Links ]

SACRISTÁN, J. G. O currículo: uma reflexão sobre a prática. 3. ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed , 2000. [ Links ]

1Translator’s note: In this work, the Brazilian acronyms will not be translated. They will keep the original initial letters as used in Brazil, unless there is an already established version in English.

2This acronym stands for Brazilian Social Democrat Party, to which Aécio Neves belongs. He was the governor of Minas Gerais from 2003 to 2010.

3The hegemonic view on PE considered here is based on an essentially biological and sport epistemology.

4O movimento renovador é entendido neste trabalho como o período no qual a EF, em meados dos anos 1970, passou a receber influências teóricas de autores desenvolvimentistas, críticos e humanistas. Buscava, assim, superar a ideia tradicional do paradigma da aptidão física hegemônico da área.

5If there was a consensus, the subject could be placed in the field of interdisciplinary evaluation. This problem results in a strong component of power relations.

6Available at: https://www.educacao.mg.gov.br/component/gmg/story/971-encontro-apresenta-diretrizes-do-projeto-escolas-referencia. Accessed on: Oct. 20, 2016.

7Available at: https://www.educacao.mg.gov.br/component/gmg/story/971-encontro-apresenta-diretrizes-do-projeto-escolas-referencia. Accessed on: Oct. 20, 2016.

Received: June 01, 2018; Accepted: May 28, 2019

texto en

texto en