Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1413-2478versão On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.25 Rio de Janeiro jan./dez 2020 Epub 12-Ago-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782020250034

Article

Literacy for the deaf: beyond alpha and beta

IUniversidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco, Senhor do Bonfim, BA, Brazil.

This paper aims to theoretically and synthetically discuss the nature of literacy for the deaf through two approaches, namely: literacy in Brazilian Sign Language (Língua Brasileira de Sinais - Libras), using the SignWriting system; and literacy in Portuguese, through the Latin alphabet alphabetic-orthographic system. This text indicates the specificities of each literacy method and discusses the more prominent problems, as perceived by the author, in the current Brazilian educational scenario. The paper argues that literacy for the deaf in Libras must be addressed by teaching methods for writing sign language through the SignWriting system, and points out the need for linguistic policies that systematize and legitimize this proposal. Furthermore, it proposes premises for those teaching literacy to the deaf who teach written Portuguese as a second language.

KEYWORDS: literacy in Brazilian Sign Language (Libras); teaching Portuguese to the deaf; SignWriting system

Este artigo objetiva discutir teoricamente, em tom de síntese, a natureza da alfabetização de surdos em duas vertentes: a alfabetização em Língua Brasileira de Sinais (Libras), por meio do sistema de escrita SignWriting, e em língua portuguesa, pelo sistema alfabético-ortográfico latino. O texto pontua as especificidades de cada modalidade de alfabetização e discute as problemáticas que do ponto de vista do autor apresentam-se com maior saliência no cenário educacional brasileiro atual. O trabalho defende que a alfabetização de surdos em Libras seja contemplada também pela escrita de sinais, mediante o sistema SignWriting, e aponta a necessidade de políticas linguísticas que sistematizem e legitimem essa proposta. Ademais, propõe premissas aos alfabetizadores de surdos que ensinam a língua portuguesa escrita como segunda língua.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: alfabetização em Libras; ensino de português para surdos; sistema SignWriting

Este artículo objetiva discutir teóricamente, en tono de síntesis, la naturaleza de la alfabetización de sordos en dos vertientes, a saber: la alfabetización en Lengua de Signos Brasileña (Língua Brasileira de Sinais - Libras), a través del sistema de escritura SignWriting; y en portugués, a través del sistema alfabético-ortográfico latino. El texto señala las especificidades de cada modalidad de alfabetización y debate sobre las problemáticas que, para el autor, tienen mayor prominencia en el escenario actual educativo brasileño. El trabajo defiende que la alfabetización de sordos en Libras, sea contemplada por la enseñanza de la escritura de señas con el SignWriting y apunta a la necesidad de políticas lingüísticas que sistematicen y legitimen esta propuesta. Además, propone premisas a los alfabetizadores de sordos que enseñan la lengua portuguesa escrita como segunda lengua.

PALABRAS CLAVE: alfabetización en Lengua de Signos Brasileña (Libras); enseñanza de portugués para sordos; sistema SignWriting

INTRODUCTION

Finding the deaf world again is a real relief. Stopping making an effort. Not having to overextend myself in an attempt to speak orally. Rediscovering the hands, the ease, the gestures that fly, that speak without effort, without embarrassment. The body movement and the eye expression that speak. Suddenly, the frustrations disappear.

Laborit, 2000, p. 133

Studies about the teaching and learning of the written Portuguese language for/by deaf children are not new in the Brazilian scenario. Without intending to list them all, we present some of these studies below, in chronological order: Gesueli (1988); Costa (2001); Dechandt-Brochado (2003); Salles et al. (2004a, 2004b); Dechandt-Brochado (2006); Quadros and Schmiedt (2006); Pires and Lopes (2007); Salles, Salles, and Chan-Viana (2007); Finau (2007); Karnopp and Pereira (2012); Karnopp (2012); Pereira (2012); Gesueli (2012); and Ribeiro (2013).

Studies on the teaching and learning of sign writing for/by deaf children based on the SignWriting system, however, are lesser yet. In Brazil, Stumpf’s pioneering work (2005) stands out, published in her academic dissertation entitled: Aprendizagem de escrita de língua de sinais pelo sistema SignWriting: línguas de sinais no papel e no computador (The learning process of sign language writing through the SignWriting system: sign languages on paper and on the computer). In addition to this seminal research, other studies and publications related to the teaching and learning of sign writing presented herein, also in chronological order, are: Loureiro (2004); Denardi (2006); Barth (2008); Silva (2009); Zappe (2010); Nobre (2011); Dallan (2012); Wanderley (2012); Silva (2013); Almeida (2015); Bózoli (2015); Barreto and Barreto (2015); Kogut (2015), among others.

Considering the significant number of existing studies and in an attempt not to expand on themes that have already received theoretical treatment, this article aimed mainly at holding a concise theoretical discussion on the nature of learning to read and write in the Brazilian sign language (Língua Brasileira de Sinais - Libras) using the SignWriting system - systematic set of graphic units that allows direct recording of any sign language - and in Portuguese, which adopts the Latin alphabetic-orthographic system - also used for the graphemic record of other oral languages worldwide - as a recording tool.

Thus, the present work is divided into four thematic sections with the following content script:

teaching deaf individuals to read and write in Libras and the specificities of the SignWriting system for the Latin alphabetic-orthographic system;

teaching deaf individuals to read and write in Portuguese and some premises for deaf literacy teachers;

the underlying problems of learning to read and write in both Libras and Portuguese for deaf individuals, given the specificities of each language; and, lastly;

the final considerations of the author.

TEACHING DEAF INDIVIDUALS TO READ AND WRITE IN LIBRAS

When it comes to teaching deaf individuals to read and write and when regarding this process as “understanding the alphabetic-orthographic system, which leads to the ability to read and produce written words” (Soares, 2018, p. 36), the first reference many people have is learning the Latin alphabetic-orthographic system to write and read in Portuguese. However, such a writing tool, despite allowing deaf people to learn to read and write in Portuguese, understood in this work as the second language of these individuals, does not favor the same learning in Libras - assumed in this text as their first language.

Deaf people learn to sign (talk) in Libras naturally when they are integrated into an environment that routinely uses this language. Therefore, the acquisition of Libras by deaf children does not require formal teaching of the language but their participation in the signing community (Quadros, 1997). Consequently, language acquisition - be it oral or signed - is not the same as literacy. Given the statements above, affirming that a child or adult who has linguistic competence in Libras is literate in Libras, would be a misconception.

What is, then, the literacy in Libras advocated in this work? It is learning a writing system able to record from the smallest constitutive units of the Libras lexicon to its morphology and spatial syntax, enabling the reading and writing of numerous texts, without the need to translate them into an oral language. In this article, the SignWriting system - an orthographic system for reading and writing in any sign language - is considered as an instrument capable of enabling deaf and non-deaf individuals to learn the written dimension of Libras. Assuming this premise means that, for the author of this work, Libras is not a language without writing, despite what other authors argue, and that literacy in Libras needs to fill the school spaces that include deaf students.

The choice for the SignWriting system in this article - to the detriment of other writing systems proposed for the written record of sign languages - to discuss teaching deaf people to read and write in Libras is not random. In addition to being one of the sign language writing systems “most in evidence lately”, Stumpf (2016, p. 83, 114) explains that

[...] most linguists who work with sign languages agree that SignWriting is the only system prepared for communication between people, considering that the Stokoe system, as well as others, has the purpose of writing the language for research, being very limited and focused on the notation of the sign, not the context.

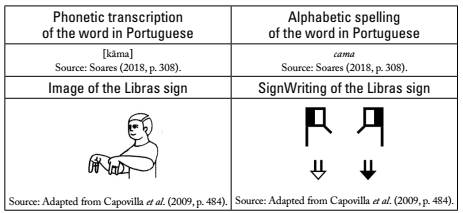

Understanding segmental writing as a way of representing the spoken/sign language - recognizing their arbitrary characteristics, not always bijective and sometimes obscure -, it should be demonstrated, even if briefly, how Latin alphabetic-orthographic systems and SignWriting work in relation to the language pair under analysis - Portuguese and Libras. Note the examples in Figure 1:

Author’s elaboration.

Figure 1 - Representation of the word/sign CAMA (bed) in alphabetical writing and SignWriting.

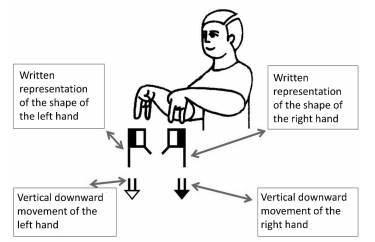

Soares (2018, p. 46) explains that “unlike logographic or ideographic writing systems, which express the meaning - the semantic content of speech -, alphabetical writing expresses the signifiers - the sounds of speech -, decomposing them into their fundamental units, the phonemes [...]”. The SignWriting system follows the same logic of alphabetic writing systems, as it records the fundamental body-visual units that constitute the sign, namely: hand shape, location, movement, palm orientation, and body-facial expression. These components can be better understood in the Figure 2, using the same example previously shown in Figure 1:

Source: Adapted from Capovilla et al. (2009, p. 484). Author’s elaboration.

Figure 2 - Presentation of fundamental sign units from SignWriting.

Figure 2 shows that the body-facial expression component (also known as non-manual expression) is not present in the writing of the sign ( ) CAMA. This situation occurs when the body-facial expression is neutral, not requiring, therefore, its written record. The palm orientation can be seen in the written sign, since each hand is shown in two colors (

) CAMA. This situation occurs when the body-facial expression is neutral, not requiring, therefore, its written record. The palm orientation can be seen in the written sign, since each hand is shown in two colors (  ) - half black and half white -, a writing rule of the SignWriting system to indicate that the palms of the hands are in an ipsilateral position.

) - half black and half white -, a writing rule of the SignWriting system to indicate that the palms of the hands are in an ipsilateral position.

What this basic and superficial explanation about SignWriting intended, rather than to make a meaningless digression, was to demonstrate that Libras - as a body-visual language - does not have a written format based on the Latin alphabet-orthography. It should be noted that the SignWriting system has the same functional nature as the alphabetic writing systems, but calling it an alphabetic system would not be appropriate for at least two reasons: first, the etymology of the word alphabet and its meaning; second, the lexicon of sign languages and the SignWriting system itself do not work based on letters. It would be more appropriate to say that SignWriting is a sublexical segmental writing system for sign languages with functional nature similar to that of alphabetic writing systems of oral languages.

Research conducted by Stumpf (2005) strongly indicates that teaching deaf children to read and write in Libras using the SignWriting system enables these individuals to learn writing in a way that makes real sense to them. In her study, Stumpf (2005, p. 266, emphasis added) concluded that

Writing needs to be a significant activity for the child. In the present study, children can write based on their understanding of sign language, not requiring the intervention of oral language. We also found that, in classes with deaf individuals in which teacher and students communicate in sign language, children actually try to write the signs when encouraged to do so.

Stimulating the writing of signs through the SignWriting system allows deaf children to comprehend writing as a representation of the sign language. As this writing evokes the learner’s whole linguistic knowledge of Libras, without the need for translation/interference into/from Portuguese. When writing in this system, deaf children “learn to establish correspondences between signs and the symbols of SignWriting”. Stumpf (2005, p. 106) also argues that

The decomposition of the written sign - connecting different fundamental graphical elements, represented by writing, with phonological, morphological, syntactic, and semantic-pragmatic aspects of the sign language - allows the learner to understand the process and try to produce their own writing.

Decomposing what is being written, understanding the writing process, and independently producing their own writing are activities that require metalinguistic awareness of the language the individual is learning. This metalinguistic awareness is not restricted to phonemic awareness, but also extends to other levels of the language. The emphasis on the metalinguistic potential of SignWriting, in this section of the study, does not mean that teachers should consider that their deaf students’ mastery of sublexical segmentation of Libras linguistic units is the end of the reading and writing learning process. Here, the intention is only to highlight the specificities and functional capabilities of SignWriting in contrast to the Latin alphabetic-orthographic system.

This article assumes that ideological power relations permeate all formal education work with language - written or signed/spoken. In this regard, language is understood to be socially used not only for communication but also as an instrument of domination, exclusion, and stratification. Therefore, when teaching deaf children to read and write beyond the alpha and beta, be it in Libras or in Portuguese, the aim should be to prepare them so they can (Freire, 2016, p. 102) “reduce the disadvantages in the struggle for life” and “acquire a fundamental instrument for the necessary fight against injustice and discrimination that target them”.

TEACHING DEAF INDIVIDUALS TO READ AND WRITE IN PORTUGUESE

This work does not deny that writing in Portuguese materializes on paper, among other things, the image of the sound of the language evoked when writing and reading a text. However, it should be noted that, although the non-deaf child begins to understand the logic of the alphabetic system and segment the words in order to grasp the phonemic metalinguistic dimension of writing as they assimilate this skill in Portuguese, the same does not usually1 occur among deaf children learning to read and write in oral languages. This situation occurs because, among other factors, the writing of oral languages graphically records (Soares, 2017, p. 28, emphasis added) “the visual representation of the speech chain”, which is inaccessible to deaf individuals due to the obviousness of their sensory condition - hearing loss.

Therefore, any approach that teaches written Portuguese to deaf people based on the phonological paradigm is problematic. Cardoso-Martins and Corrêa (2008, p. 279) explain that this paradigm

[...] is based on the assumption that the main task of the child when learning to read and write consists of understanding that letters represent sounds in the pronunciation of words. As a result, this paradigm has stimulated studies on the relationship between the development of knowledge of letter-sound correspondences and phonological awareness, on the one hand, and the development of writing, on the other.

The adoption of approaches that teach deaf people to read and write in Portuguese grounded on the phonological paradigm has been counterproductive and disastrous for deaf learners. In this scenario, Pereira (2012, p. 239) declares:

[...] it is essential to change the concept of writing that still predominates in most institutions that assist deaf people in Brazil. A concern with reading and writing skills persists, that is, with teaching letters, their combination into words, their encoding and decoding, while little or no importance is given to the uses of writing as broader social practices (literacy). Consequently, many deaf students, despite being able to identify isolated meanings of words and use the phrasal structures studied, cannot effectively use the language [...].

In fact, teaching deaf people to read and write beyond the alpha and beta is not only necessary, but urgent. However, certain aspects need to be very clear when considering the literacy of deaf people in Portuguese. First, teachers and educators must understand that, rather than Portuguese, Libras is the language of reference for the construction of the world knowledge and thought organization for the deaf student. Understanding and accepting this aspect is a fundamental principle, since it reveals a radical difference between deaf and non-deaf students, leading to profound implications for the teaching and learning process in Portuguese classes.

Currently, in Brazil, the inclusive educational model determines that deaf and non-deaf children attend classes together in all disciplines, including Portuguese. Usually, during the reading of a text, for example, Portuguese teachers do not need to expand on the meaning of the words, unless one of them is a word that escapes the everyday vocabulary of their students. Teacher correctly assume that all students are native Portuguese speakers and that it is unnecessary to explain the lexical-semantic aspects of the text. Nevertheless, in classrooms with deaf students, this assumption is misguided, as it is very likely that these students do not know the meaning of almost all words in the text.

The second crucial aspect is that, unless the teacher has full linguistic competence in Libras and Portuguese, deaf students will not have the desired success in learning to read and write. This situation happens because deaf students, when learning Portuguese writing, depend on formal instruction to reach them through the language that best organizes their intellectual thought, in this case, Libras. The teacher will have to resort frequently to the similarities and contrasts between formal, discursive, and pragmatic linguistic aspects of one language and the other.

Using the same example of the inclusive classroom, with deaf and non-deaf students reading a text, let us suppose that the teacher, who does not know Libras, which is very common in Brazilian schools, suggests that deaf students search the meaning of each Portuguese word of the text in Libras dictionaries, printed or virtual. That strategy, at first, could work. However, “the main difficulty for deaf people when writing an oral language” - saving the idiosyncratic specificities of polysemy - “is not the lexicon but the syntax” (Stumpf, 2005, p. 44).

The point here is: how can teachers, who do not have full linguistic competence in Libras and Portuguese, explain the functional words from the Portuguese text, such as “de/da” and “no/na” (“of” and “in”, both referring to masculine and feminine nouns, respectively), to deaf students? A teacher with full linguistic competence in Libras and Portuguese, knowing that these functional words do not have correspondents in Libras and that they will assume a different semantic value depending on their syntactic context, understands that it would be useless to propose that deaf students search the meaning of the words in dictionaries. A more reasonable and efficient approach would be the conscious intervention of teachers who, through direct and formal instructions, explain the possible occurrences for these functional words in certain syntactic contexts, indicating their respective semantic values in each case.

A third point that teachers of deaf students should consider is that the teaching of Portuguese writing must start with the reading of actual texts produced in that language. Since deaf people do not learn the oral modality of Portuguese, written texts will be their main access to contents in this language. There is nothing to discuss, however, about texts produced specifically for the teaching of deaf readers. The teaching approach for this population must be differentiated, for the reasons presented herein, but caricaturing the use of writing or cultural productions, aiming to adapt them to deaf students, would not be appropriate.

Karnopp (2012), when reporting some of the testimonies collected from deaf university students, explains that, for these individuals, reading entire works was a novelty experienced only when they started their academic education. According to them, during basic education, the readings proposed consisted of short texts from newspapers and magazines. Teachers avoided suggesting reading and writing activities, presuming that deaf students would have extreme difficulty in reading and writing or that they disliked these activities. The author continues her account:

Isabel, 21 years old, university student, declared that students in her class questioned the teacher’s work by asking: “Why don’t we read books now that we are in high school?” The teacher replied that such activity was extremely difficult for deaf students and that they needed to study the vocabulary, grammar, and sentence structuring in small texts first before reading books. Upset by the teacher’s answer, they went to the library in their free period to choose some books. When they arrived, the librarian gave them only thin, childish books, explaining that those were easier for them. The students did not read the books recommended, as the subject did not interest them, and, at the same time, they did not want to leave the library with a book suitable for an age group different than theirs. They feared that someone would question why they, as young adults, were reading a children’s book. They returned to class and completed high school without reading a single book. (Karnopp, 2012, p. 154-155)

This case illustrates how the concern, albeit well-intentioned, of some teachers in adapting the reading content available to deaf students, can limit and inhibit the pursuit of these students for works written in Portuguese. Deaf students’ exposure to texts on different topics can be a good opportunity to expand their vocabulary repertoire and other surface structures present in the texts. In addition, much of the knowledge historically accumulated can only be accessed through reading materials, many of which are only available to deaf people in Portuguese.

LEARNING TO READ AND WRITE IN LIBRAS AND PORTUGUESE: PROBLEMATIC ASPECTS

The strongest issue regarding the teaching of deaf individuals to read and write using SignWriting is the social use of this writing system. Currently, studies conducted on the subject leave no doubt that “the content written in SWS [SignWriting system] follows the thought organization and grammatical structure of Libras without interference from any spoken language” (Stumpf, 2016, p. 87), but the predominating writing in the social practice of Brazilian citizens is Portuguese-graphocentric, with hegemony of the Latin alphabetic-orthographic system. Thus, even if deaf children learn to read and write in Libras, which of these social practices would require using the SignWriting system? Would it be a writing system restricted to the school and academic environment? If so, which subjects would adopt SignWriting as the writing system during classes? Only Libras?

The questions are not so simple to answer. Much of what is intended when it comes to teaching deaf people to read and write in Libras using SignWriting depends on a consistent linguistic policy that systematizes at least four measures: first, defining SignWriting as the official Libras writing system; second, the training of all Libras teachers must include the compulsory teaching of SignWriting; third, adopting SignWriting as the writing system when teaching deaf children to read and write;2 and fourth, having financial support to develop and distribute didactic and educational materials written in SignWriting.

Confusing the social use of writing with its utilitarian perspective, however, is unreasonable. This scenario is particularly worrying when teaching deaf children to read and write in Libras using SignWriting, as this short utilitarianism might limit their opportunity for contact with a writing format that provides them with a direct interaction between the written record and their natural language. In her dissertation, Stumpf (2005) states that, during her sandwich Ph.D. fellowship in France, some professors and students did not accept the proposal of teaching reading and writing in the French Sign Language (Langue des Signes Française - LSF) using SignWriting, as they believed that the priority should be to teach reading and writing in French, only. As a certain student put it, “LSF writing is not useful for work in the future” (Stumpf, 2005, p. 200).

Teaching deaf people to read and write in Portuguese leads to many problems and controversies that could feature in this topic, but only one of them will be further discussed here: the psycholinguistic factor of communicative continuity. Capovilla et al. (2006, p. 1.942) explain the continuity phenomenon in the following terms:

The hearing and speaking child shows continuity between three basic communicative contexts: transient self-communication (i.e., the thinking), transient communication with others face-to-face (i.e., the talking), and perennial communication in a remote and mediated relationship (i.e., the writing). As a result, all their linguistic processing can concentrate on the spoken word of the same language: They can use the same words from their main spoken language to think, communicate, and write. For this child, the primary (i.e., spoken language) and secondary (i.e., written alphabetical language) linguistic representation systems are compatible.

Deaf children might face a rupture of the psycholinguistic factor of communicative continuity during the process of learning to read and write in Portuguese. They think in Libras, establish their face-to-face interactions in Libras with other Libras-speaking interlocutors, but when they need to write, they are instructed to do so in Portuguese. The result of this discontinuity is easily noticeable in the syntactic organization of texts produced by deaf individuals taught to read and write in Portuguese, as they transfer to paper a reflection of their syntactic thought originated/organized in Libras. On this characteristic of texts written by deaf people, Perlin (2003, p. 53) explains that “deaf individuals will always write in the border language, not in politically and epistemologically correct Portuguese as hearing people do”.

A fact often unnoticed is that, when deaf people write in Portuguese, sign language is not being continuously converted into sign writing - as occurs when they write and read in SignWriting -, but rather the translation of a thought generated/organized in Libras - a language whose production and reception modality is body-visual - into a writing that works within the structural format of the Portuguese language, which is auditory-oral. Therefore, in this case, deaf individuals do not think and write in the same language; they actually translate Libras (source language) into Portuguese (target language) in order to make the target text understandable, accurate, consistent, and cohesive for both the writer and the reader. Not surprisingly, Perlin (2015, p. 57), when referring to the written production of deaf people in Portuguese, concludes that “deaf individuals should not be required to produce a symbolic construction as natural as hearing individuals”.

Given the arguments above, it is not intended to deny the importance of the Portuguese language for the inclusion and participation of deaf people in social spheres, as well as their movement and access to higher social strata. This is a truism that no longer needs to be discussed, in the same way that we should not affirm that teaching Portuguese writing and its orthographic intricacies to deaf people is useless. This is intended, nonetheless, to alert teachers that this specificity of deaf literacy students demands the adherence to teaching approaches that take into account the cognitive load required from this population in the learning process of writing in Portuguese.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Based on the aspects discussed in the previous sections of this article, two proposals for teaching deaf people to read and write were presented, which are not mutually exclusive nor dichotomous, but equally necessary. We underline that learning to read and write in Libras, in the current scenario of education for deaf people in Brazil, corresponds to the most vulnerable and hazy learning modality in standardizing documents for national education. On the other hand, literacy in Portuguese already has legal support and educational policies that seek to ensure this right to deaf people - with many obstacles, gaps, and little theoretical knowledge, resulting in an inefficient teaching process that perpetuates learning asymmetries.

Among the premises for educators teaching deaf students to read and write in Portuguese, presented in the third section of this article, we highlight that training teachers with an in-depth knowledge of the language pair Libras/Portuguese is crucial to ensure the success of the formal teaching of Portuguese writing for this population, enabling them to satisfactorily master the writing of the main national language. No matter the educational model adopted - inclusive education: regular school attended by deaf and not-deaf students; or bilingual education: school planned specifically for deaf students, using Libras as the teaching language in all classes and Portuguese as the second language in the written modality -, the priority should be satisfying the demand for training of teachers with the necessary professional qualification to meet the needs imposed by deaf education.

We recognize that the suggestion of using linguistic policies to guide possible solutions for the underlying problems related to teaching deaf students to read and write in Libras using the SignWriting system, presented with more detail in the fourth section of this work, may sound like an imposition and corporatism by an author converted to suttonism.3 Nevertheless - acknowledging the necessary and healthy contrary positions in the current scenario, in which research papers and proposals for new writing systems for sign languages within academia thrive, as well as the reader’s right to make their own value judgment about this text -, our main expectation is that teaching deaf people to read and write in Libras be practical and based on guiding systematizations that define and ensure its implementation in Brazilian schools with deaf students.

Lastly, we expect that the considerations, discussions, and proposals presented in this work encourage readers and researchers, deaf and non-deaf, to reflect on the proposed theme. The lack of research - especially longitudinal studies on the learning of SignWriting by deaf children and the systematized teaching of Portuguese writing for deaf people - to provide the scientific support necessary for the pedagogical practices of teachers is still a reality. Unfortunately, this lack - not absence - of research, despite not enabling, can stimulate improvisation and school inertia concerning the teaching of reading and writing to deaf people in Brazil.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, M. L. G. A importância da escrita de sinais junto com o ensino da Libras. 2015. Dissertação (Mestrado Profissional em Ensino em Ciência de Saúde) ― Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2015. [ Links ]

BARRETO, M.; BARRETO, R. Escrita de sinais sem mistérios. 2. ed. rev. atual. ampl. Salvador: Libras Escrita, 2015. [ Links ]

BARTH, C. Construção da leitura/escrita em língua de sinais de crianças surdas em ambientes digitais. 2008. 141 fls. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) ― Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2008. [ Links ]

BÓZOLI, D. M. F. Um estudo sobre o aprendizado de conteúdos escolares por meio da escrita de sinais em escola bilíngue para surdos. 2015. 188 fls. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) ― Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Maringá, 2015. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Relatório sobre a política linguística de Educação Bilíngue - Língua Brasileira de Sinais e Língua Portuguesa. Brasília, DF: MEC/SECADI, 2014. Available in: Available in: http://www.bibliotecadigital.unicamp.br/document/?down=56513 . Access in: May 23, 2019. [ Links ]

CAPOVILLA, F. C. et al. A escrita visual direta de sinais Sign Writing e seu lugar na educação da criança surda. In: CAPOVILLA, F. C.; RAPHAEL, W. D. Dicionário enciclopédico ilustrado trilíngue da Língua Brasileira de Sinais - volume II: sinais de M a Z. 3. ed. São Paulo: Edusp, 2006. p. 1.491-1.496. [ Links ]

CAPOVILLA, F. C.; RAPHAEL, W. D.; MAURÍCIO, A. C. L. Novo Deit-Libras: dicionário enciclopédico ilustrado trilíngue da Língua de Sinais Brasileira (Libras) baseado em linguística e neurociências cognitivas. Volume I: sinais de A a H. São Paulo: Edusp ; Inep; CNPq, 2009. [ Links ]

CARDOSO-MARTINS, C.; CORRÊA, M. F. O desenvolvimento da escrita nos anos pré-escolares: questões acerca do estágio silábico. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, Brasília, DF, v. 24, n. 3, p. 279-286, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-37722008000300003 [ Links ]

COSTA, D. A. F. A apropriação da escrita por crianças e adolescentes surdos: interação entre fatores contextuais, L1 e L2 na busca de um bilinguismo funcional. 2001. Tese (Doutorado em Linguística) ― Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, 2001. [ Links ]

DALLAN, M. S. S. Análise discursiva dos estudos surdos em educação: a questão da escrita de sinais. 2012. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) ― Universidade de São Francisco, Itatiba, 2012. [ Links ]

DECHANDT-BROCHADO, S. M. A apropriação da escrita por crianças surdas usuárias da Língua de Sinais Brasileira. 2003. 439 fls. Tese (Doutorado em Letras) ― Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” , Assis, 2003. [ Links ]

DECHANDT-BROCHADO, S. M. A apropriação da escrita por crianças surdas. In: QUADROS, R. M. (org.). Estudos surdos I. Petrópolis: Arara Azul, 2006. p. 284-322. [ Links ]

DENARDI, R. M. AGA-Sing: animador de gestos aplicado à língua de sinais. 2006. 82 fls. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciência da Computação) ― Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2006. [ Links ]

FINAU, R. O processo de formação de interlíngua na aquisição de língua portuguesa por surdos e as categorias de tempo e aspecto. In: SALLES, H. M. M. L. (org.). Bilinguismo dos surdos: questões linguísticas e educacionais. Goiânia: Cânone Editorial, 2007. p. 159-190. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P. Professora sim, tia não: cartas a quem ousa ensinar. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 2016. [ Links ]

GESUELI, Z. M. A criança não ouvinte e a aquisição da escrita. 1998. 209 fls. Dissertação (Mestrado em Linguística) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 1988. [ Links ]

GESUELI, Z. M. A escrita como fenômeno visual nas práticas discursivas de alunos surdos. In: LODI, A. C. B.; MÉLO, A. D. B.; FERNANDES, E. (orgs.). Letramento, bilinguismo e educação de surdos. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2012. p. 173-186. [ Links ]

KARNOPP, L. B. Práticas de leitura e escrita entre os surdos. In: LODI, A. C. B.; MÉLO, A. D. B.; FERNANDES, E. (orgs.). Letramento, bilinguismo e educação de surdos. Porto Alegre: Mediação , 2012. p. 153-172. [ Links ]

KARNOPP, L. B.; PEREIRA, M. C. C. Concepção de leitura e de escrita na educação de surdos. In: LODI, A. C. B.; MÉLO, A. D. B.; FERNANDES, E. (orgs.). Letramento, bilinguismo e educação de surdos. Porto Alegre: Mediação , 2012. p. 125-134. [ Links ]

KOGUT, M. K. As descrições imagéticas na transcrição e leitura de um texto em SignWriting. 2015. 161 fls. Dissertação (Mestrado em Linguística) ― Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2015. [ Links ]

LABORIT, E. O grito da gaivota. Translation of Ângela Sarmento. Lisboa: Caminho, 2000. Original Title: Le cri de la mouete. [ Links ]

LOUREIRO, C. B. C. Processo de apropriação da escrita da língua de sinais e escrita da língua portuguesa: informática na educação. 2004. 150 fls. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2004. [ Links ]

NOBRE, R. S. Processo de grafia da língua de sinais: uma análise fono-morfológica da escrita em Sign Writing. 2011. 203 fls. Dissertação (Mestrado em Linguística) ― Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2011. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, M. C. C. Papel da língua de sinais na aquisição da escrita por estudantes surdos. In: LODI, A. C. B.; MÉLO, A. D. B.; FERNANDES, E. (orgs.). Letramento, bilinguismo e educação de surdos. Porto Alegre: Mediação , 2012. p. 235-246. [ Links ]

PERLIN, G. T. T. O ser e o estar sendo surdos: alteridade, diferença e identidade. 2003. 156 fls. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) ― Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2003. [ Links ]

PERLIN, G. T. T. Identidades surdas. In: SKLIAR, C. (org.). A surdez: um olhar sobre as diferenças. 7. ed. Porto Alegre: Mediação , 2015. p. 51-73. [ Links ]

PIRES, L. C.; LOPES, R. E. V. A aquisição da flexão em português escrito por sinalizantes surdos: uma reflexão inicial sobre educação bilíngue. In: SALLES, H. M. M. L. (org.). Bilinguismo dos surdos: questões linguísticas e educacionais. Goiânia: Cânone Editorial , 2007. p. 17-48. [ Links ]

QUADROS, R. M. Educação de surdos: a aquisição da linguagem. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 1997. [ Links ]

QUADROS, R. M.; SCHMIEDT, M. L. P. Ideias para ensinar português para alunos surdos. Brasília, DF: MEC/SEESP, 2006. [ Links ]

RIBEIRO, V. P. Ensino de língua portuguesa para surdos: percepções de professores sobre adaptação curricular em escolas inclusivas. Curitiba: Prismas, 2013. [ Links ]

SALLES, H. M. M. L.; FAULSTICH, E.; CARVALHO, O. L.; RAMOS, A. A. L. Ensino de língua portuguesa para surdos: caminhos para a prática pedagógica. Brasília, DF : MEC/SEESP, 2004a. v. 1. [ Links ]

SALLES, H. M. M. L.; FAULSTICH, E.; CARVALHO, O. L.; RAMOS, A. A. L. Ensino de língua portuguesa para surdos: caminhos para a prática pedagógica. Brasília, DF : MEC/SEESP, 2004b. v. 2. [ Links ]

SALLES, H. M. M. L.; SALLES, P. S. B. A.; CHAN-VIANA, A. C. Formulação de inferências e propriedades da interlíngua dos surdos na aquisição do português (escrito). In: SALLES, H. M. M. L. (org.). Bilinguismo dos surdos: questões linguísticas e educacionais. Goiânia: Cânone Editorial , 2007. p. 97-118. [ Links ]

SILVA, E. V. L. Narrativas de professores surdos sobre a escrita de sinais. 2013. 113 fls. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) ― Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2013. [ Links ]

SILVA, F. I. Analisando o processo de leitura de uma possível escrita da Língua Brasileira de Sinais: SignWriting. 2009. 114 fls. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) ― Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2009. [ Links ]

SOARES, M. Alfabetização: a questão dos métodos. São Paulo: Contexto, 2018. [ Links ]

STUMPF, M. R. Aprendizagem de escrita de língua de sinais pelo sistema Sign Writing: língua de sinais no papel e no computador. 2005. 330 fls. Tese (Doutorado em Informática na Educação) ― Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2005. [ Links ]

STUMPF, M. R. O estado da arte da escrita de língua de sinais pelo sistema SignWriting: uma meta-análise. In: BIDARRA, J.; MARTINS, T. A.; SEIDE, M. S. (orgs.). Entre a Libras e o português: desafios face ao bilinguismo. Cascavel: EDUNIOSTE; Londrina: EDUEL, 2016. p. 83-116. [ Links ]

WANDERLEY, D. C. Aspectos da leitura e escrita de sinais: estudos de caso com alunos surdos da educação básica e de universitários surdos e ouvintes. 2012. 192 fls. Dissertação (Mestrado em Linguística) ― Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2012. [ Links ]

ZAPPE, C. T. Escrita da língua de sinais em comunidades do Orkut: marcador cultural na educação de surdos. 2010. 67 fls. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) ― Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria, 2010. [ Links ]

1 There are different degrees of hearing loss. Some deaf people speak the oral language of their country of origin. Part of these individuals have a significant knowledge of oral language and use it with competence in their daily interactions with non-deaf people.

2 The Relatório sobre a política linguística de educação bilíngue - Língua Brasileira de Sinais e língua portuguesa (Report on the linguistic policy for bilingual education - Brazilian Sign Language and Portuguese language) defends the “visual literacy in sign writing for deaf individuals” (Brasil, 2014), but does not define which sign writing system should be adopted during the process of teaching deaf children to read and write in their first language.

Received: June 04, 2019; Accepted: February 10, 2020

texto em

texto em