Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1413-2478versión On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.25 Rio de Janeiro ene./dic 2020 Epub 20-Sep-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782020250041

ARTICLE

Historical meanings of young adults education and public policies of integration in professional education with schooling: dialogues between Brazil and France

IUniversidade Federal de Lavras, Lavras, MG, Brazil.

Using a cross-face study of adult education in France from the perspective of professionalization and the conception of training instituted by the National Integration Program of the Professional Education with the Basic Education in the Youth and Adult Education Modality (Programa Nacional de Integração da Educação Profissional com a Educação Básica na Modalidade Educação de Jovens e Adultos) in Brazil, this article sought to reflect on the meanings of integrated training for vocational training combined with increased enrollment for youth and adults as a political strategy to serve this public. The aim was to promote a theoretical discussion about the pedagogical conception and practices that respond to the specificities of the subjects of the youth and adult education, establishing a dialogue with experiences of integrated formation already consolidated in France, in order to make possible contributions to the epistemological field inaugurated by program.

KEYWORDS: youth and adult education; integrated vocational training; comparative study

Valendo-se de um olhar cruzado entre estudos sobre a formação de adultos na França, pela perspectiva da profissionalização, e a concepção de formação instituída pelo Programa Nacional de Integração da Educação Profissional com a Educação Básica na Modalidade Educação de Jovens e Adultos no Brasil, este artigo buscou refletir acerca dos sentidos da formação integrada para a formação profissional aliada ao aumento de escolarização para jovens e adultos como estratégia política para atender esse público. Buscou-se promover uma discussão teórica quanto à concepção e às práticas pedagógicas que respondem a especificidades dos sujeitos da educação de jovens e adultos, estabelecendo um diálogo com experiências de formação integrada já consolidadas na França, a fim de possibilitar contribuições ao campo epistemológico inaugurado pelo referido programa.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: educação de jovens e adultos; formação profissional integrada; estudo comparado

Al valerse de una mirada cruzada sobre la formación de adultos en Francia, por la perspectiva de la profesionalización, y la concepción de formación instituida por el Programa Nacional de Integración de la Educación Profesional con la Educación Básica en la modalidad Educación de Jóvenes y Adultos (Programa Nacional de Integração da Educação Profissional com a Educação Básica na Modalidade Educação de Jovens e Adultos) en Brasil, este artículo buscó reflejar la cerca de los sentidos de la formación integrada para formación profesional aliada al aumento de escolarización para jóvenes y adultos como estrategia política para atender a este público. Se buscó promover una discusión teórica en cuanto a la concepción y las prácticas pedagógicas que responden a las especificidades de los sujetos de la educación de jóvenes y adultos, estableciendo un diálogo con experiencias de formación integrada ya consolidadas en Francia, a fin de posibilitar contribuciones al campo epistemológico inaugurado por el programa.

PALABRAS CLAVE: educación de jóvenes y adultos; formación profesional integrada; estudio comparativo

This study was based on the understanding of the meanings and conceptions of integrated education1 to increase schooling and professional education of youth and adults and on strategies developed to serve this audience through a cross-examination of research about adult education in France - whose concept is anchored in life-long learning and is developed through an interface with professionalization - with the concept of integrated education found in Brazil’s National Program of Integration of Professional Education with Basic Education in the Modality of Youth and Adult Education (Programa Nacional de Integração da Educação Profissional com a Educação Básica na Modalidade Educação de Jovens e Adultos ― PROEJA), an integrated education program which seeks to overcome the historical separation between the education of youth and adults and professional education in Brazil.

This work started from the understanding that youth and adult education is inserted, in the realities of both countries, in distinct contexts. In France, basic education is a universalized right and adult education is inserted in a dual educational system, in which there are two educational possibilities: academic and professional. The country has a complex, centralized system, with little flexibility and that is allied to institutional criteria that are difficult to understand in the final definition of the trajectories of individuals. The system calls for certain youth, 14 years old or older, to undertake part of their education at companies for the discovery of their professional aptitudes, and that implemented and consolidated a professionalizing system as the route for youth and adults “who had left school”, and as an option for education and professional insertion. Thus, an intimate relationship between adult and professional education and its application to the lower classes is identified.

In the Brazilian context, the need for education for youth and adults is produced, among many reasons, since the right to education since childhood is not assured - although historically supported by legal measures, these only gained foundation in the most recent Federal Constitution of 1988. The existence of adults who cannot read or have too little schooling cannot be ignored and is currently linked to the production of a substantial number of students who do not conclude the regular schooling system. Thus, the education of youth and adults has historically been appropriated by the line of literacy and schooling in the early grades and with little or nearly no articulation with professional education, which is seen in experiences at union entities.

This separation between youth and adult education and professional education and the possibility to overcome this dichotomy takes place with the proposal of public policies aimed at this purpose, such as PROEJA, by means of which the government expanded the political place of youth and adult education, organizing the modality as a public policy, no longer limiting it to literacy, but guaranteeing continuity of schooling at the high school level, and innovating by proposing it in an integrated manner with professional education.

Thus, the establishment of this program in 2005 by Brazil’s Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação ― MEC), created an opportunity to overcome this dichotomy, by approximating thematic fields that had previously been independent - professional education, high school, and youth and adult education - through a proposal for integrated education. The establishment of a specific epistemological field, at the intersection of these fields, required a theoretical deepening regarding the concepts and pedagogical practices that respond to the specificities of the individuals served, and led me to establish a dialog with experiences of integrated education already consolidated in France, to offer contributions to the epistemological field inaugurated by the program.

HISTORIC MEANINGS OF PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION OF ADULTS IN FRANCE

Professional education of adults has a complex connotation in France. It is inscribed in the broader field of adult education, which Ardouin (2017) denominated as the social world of adult education. In a broad connotation, adult education is constituted by different interactions, experiences, and ideologies, which involve processes ranging from learning to read, schooling, professional education, and others. In this perspective, education is articulated in three spheres: education, work, and society.

In the sphere of schooling, adult education corresponds to those who return to their studies or that are at a stage of a qualifying education. In the sphere of work, it involves continued professional education and, also, in-service education. Between schooling and work, education exists by an alternance or education in immersion. In the sphere of society, adult education is aimed at families, with an emphasis on education for health or for social accompaniment, without an aim at qualification or a consideration for employment, but to improve integration with or life in society.

Adult education is diversified and present in different social worlds. In this aspect, there is a need to understand the interaction between policies and practices, considering the youth and adult public in a situation of social and professional learning and of different levels of schooling, and the practices of integration for that purpose.

Studies by Ardouin (2017) and Wittorski (2016) identified that the professional education of adults in relation to the world of work has gained projection in current national education policies in France. There have been expressive changes in the conceptual field of professional education of adults, including a new approximation between the school and the work systems, to exclusively serve the economic field.

The professional education of adults is the fruit of a socio-historical construction, in which is seen a passage from the idea of permanent education and life-long learning until reaching the idea of education throughout life in the current historical moment. This change reveals a dispute of ideological currents, between that of a broad education of citizens and education for employability.2

The idea of permanent education has its origin in a discourse by Condorcet in the National Assembly of France, when he instituted public instruction in 1792. The principles of that document called for the broad education of citizens, social justice, the development of knowledge, the democratization of access to education for all and lifelong learning. According to studies by Ardouin (2017), permanent education is inscribed in the values of popular education for cultural education and education of citizens. The France, this idea was institutionalized as a foundation of professional education for adults under Law no. 71-577 of July 1971, which established the system of professional education for youth and adults, in article 1º:

Continued professional education is part of permanent education. Its objective is to allow the adaptation of workers to technical changes and to working conditions, to support their social promotion for access to different levels of culture and professional qualification and their contribution to cultural, economic, and social development.3 (Free translation)

This concept of professional education for adults, thus, has a broad meaning, and proposes preparation for the world of work, without, however, being restricted to technical and operational education. It expresses a desire for an education that can provide individuals with opportunities to produce their own development, but that above all contributes to social and economic development.

In the 1990s, the concept of adult education came to be based on the idea of lifelong learning. The Hamburg Declaration (UNESCO, 1997) about adult education introduced the idea of learning throughout life as a key to the 21st century and the foundation of societies, and through it, the education of youth and adults was consolidated in the line of schooling and continuing education. As expressed by Paiva (2009, p. 180), the true meaning of youth and adult education is that of continuing education, which is presented by the diversity of educational actions linked to matters of gender, ethnicity, professionalization, and environmental issues, which can provide individuals with more suitable conditions to act given the complexity of contemporary life.

Three aspects delineated by the Declaration deserve to be emphasized, as they concern youth and adult education as a right:

the establishment of youth and adult education as a human right, a means for the construction of an equitable and just world, and a way to assure the participation of all in societies;

as a responsibility of the State, which is responsible for developing public policies; and

the formulation of education policies for youth and adults that are committed to their needs and specificities.

These guidelines encompass not only adult education, but also that of youths and professional education.

Ardouin (2017), although recognizing distinctions, understands that there are more points in common between lifelong and permanent education, which leads him to defend them as synonymous concepts, and as the foundational concepts of professional education of adults in France.

Lifelong learning, in turn, is related to the need of individuals to learn continuously, considering the maintenance of employability in organizations, or to allow obtaining a job. Its function is aimed, firstly, at meeting employability needs, before it is aimed at society. The adoption of this concept by the French State took place in the 2000s, in contrast to the expansion of the humanist idea of permanent education, found in the system of professional education, justified by practical problems and limitations identified in statistical studies by French research institutes. Ardouin (2008) attributed to the (statistical) results of these studies the failure to achieve the objectives foreseen by the system for continuing education, the development of an unequal model (because of the level of qualification and the professional situation of the individual, etc.), as it is mostly used by already educated individuals and with disparities related to the professional sector. In conclusion, the initial education acquired in primary schooling winds up being the sole means for qualification and continuing professional education becomes a means to maintain competencies,4 though without making it viable for all individuals - due to the complexity and poor clarity of the educational system - the possibility to construct other professional alternatives and paths.

The discussion about competencies in France began in the 1970s, based on the questioning of the concept of qualification and professional education, which was mainly technical, due to the identification of a gap between the needs of the business world and the qualification of workers. Without ignoring the multiplicity of definitions coexisting in the current situation of French professionalization, I identified that the idea is prevalent of competencies as a set of social and communication learnings constructed by learning and education, which implies mobilization, integration, and the transfer of one’s own knowledge and resources in a socio-professional context (Le Boterf, 1994). This is a characteristic that is not intrinsic to the individual, but a quality attributed or recognized by others, as a result of an effective action applied in a professional situation (Wittorski, 2011).

The French context is complemented by the fact that the European Community found similar disparities in access to education in other European systems, which led to the proposal by the European Parliament, of a policy to develop education based on concepts and guidelines found in the White paper about education and training, in 1996 (the European Year of Education and Lifelong Learning). This document identified that the ultimate goal of education and “formation” is employability; and that of “formation” is to develop the autonomy of each individual and their professional competence, providing each one access to general education and to the ability to be employed in a productive activity. The White paper, by focusing on professional education for employability, reveals the reductive character of education in terms of its social, cultural, and professional dimensions.

It is also highlighted that these proposals occur amid transformations and crisis in the socio-economic realm of the European context and influence and engender changes in the conceptual field and in policies for professional education of youth and adults in France, with the substitution of the idea of permanent education present in the law of professional education of 1971, by the notion of lifelong education found in the Labor Code, law no. 391 of May 4th, 2004, article 4º:

Professional education throughout life is a national obligation. The objective of continued professional education is to support the professional insertion or reinsertion of workers, to allow them to remain employed, to support the development of their competencies and access to different levels of professional qualification, and to contribute to economic and cultural development and to their social promotion. (Free translation)5

This article of the Labor Code reveals that the perspective of education as a right, and which has a collective and social purpose, previously linked to permanent education, gives way to the concept based on a logic of operational educational, with an emphatic duty to adapt to the needs of the productive world.

The paradigmatic transition in the field of professional education of adults has caused it to lose broad conceptual contours; having become focused on the professional dimension from the perspective of employability, it becomes a line of education throughout life, as Ardouin (2017) affirms. The civic and collective dimensions disappear, and the socio-economic dimension of education becomes institutionalized. This change reveals the predominance given to market demands, in detriment to broader social and cultural concerns, and that professionalization has become the perspective of the current policy of professional education of adults, in France.

CURRENT SITUATION OF POLICES OF PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION FOR YOUTH AND ADULTS IN FRANCE: PROFESSIONALIZATION AS AN OPTION

Given the current institutional orientations concerning continuing professional education, the political and pedagogical adoption of professionalization as an educational possibility for youth and adults can be identified. Thus, I will reflect on the meanings and questions that involve professionalization as an option for education.

The idea of professionalization is a polysemic concept. Studies by Wittorski (2016) and Geay (2016) help identify the central meanings of professionalization in a classical and more current perspective.

In a historical perspective, the term professionalization is related to practical conduct in a certain field, related to the learning of a certain occupation. Geay (2016) relates the meaning of professionalization to an opposition between intellectual work and manual labor that had been established in the 13th century, when the term profession came to be restricted to certain occupations taught in the realm of universities, and which could no longer be learned exclusively by practicing the occupation. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the expression professionalization had distinct connotations. In Anglo-Saxon countries, it was associated to the idea of the liberal professional; while in France it was associated to the constitution and organization of groups of workers with their own rules, in a context of political struggle of these distinct groups over space, within a highly elitist hierarchical structure.

Thus, from a sociological and traditional perspective, professionalization can be understood as a legitimizer of professions. It is understood as a process by which a labor practice or trade becomes a profession, aimed at meeting the needs of the work environment. It involves a process of negotiation and the recognition of transforming a task into a profession, with the establishment of educational exercises and procedures. This idea is related to the recognition of an occupation as a profession that has its own rules and procedures, which supposes the establishment of practices to be developed at an institutional level, whether at a university or large school that also offers professional education.

From the perspective of the current meaning, professionalization can be grasped from two complementary meanings:

professionalization as an integration between work and education. It is a process that considers the work activity as the space-time of education, allowing in loco education, integrated to work; or which promotes a moment of retrospective or prospective reflection on working situations, to experiment with new professional practices that give emphasis to the logic of quality/effectiveness;6

professionalization as a qualification for work. In this sense, the field of education seeks to reveal the professionalizing character of its offers for education, in an attempt to convince those who contract a service that there is a need for education to practice the service, that they can have access to effective educational measures, to improve the location and performance of their educational practices. That is, they seek to develop the effectiveness of measures that seek to improve the place and legitimacy of the offer and practices of education.

The discussion about effectiveness (efficacité, in French) and efficiency (efficience, in French) began in the 1970s with the global crisis and worldwide questioning of the bureaucratic model of State administration that arose with the advent of globalization. The reformulation of this model resulted in the adoption of the managerial model in public administration, which emphasizes excellence in administrative management. The concept is associated to the logic of results, which is obtained by achieving the objectives established with the available resources (Barbier and Wittorski, 2015). Thus, I understand that in the field of professional education, effectiveness is found when individuals have command of all the skills determined as necessary to exercise their profession, regardless of the company for which they work.

The concept of efficiency (efficience), in turn, is often confused with the term effectiveness, however it concerns the proportion between resources mobilized and the results obtained (Barbier and Wittorski, 2015). Efficiency represents the guarantee of results already obtained or greater results using as few available resources as possible (which may include various kinds, such as: institutional, human, financial, temporal, spatial, methodological, etc.). Thus, an action is efficient when an individual uses the resources in a rational manner to obtain the expected success.

These measures are part of a dispute of concepts of professionalization found in the logic of education-employment and education-occupation. The opposition is presented respectively between a perspective focused on adaptation, which involves the idea of training or development of “specific” competencies, and a “transversal” perspective, which values the idea of development of generalist or transferable competencies to various jobs and professions (Wittorski, 2008).

An important aspect in the discussion on concepts of professionalization concerns the theoretical lines that characterize professionalizing education. One line defends education specifically focused on a job or professional field; a second line understands that the education would be focused on practical issues, adopting knowledge constructed in an “operational” manner; and a third line affirms that it involves the education of professionals in partnership with companies.

The current meanings of professionalization and its growing use as a pedagogical fundament in the education of adults are at the heart of economic and social transformations of a market aegis, focused on logic of results and decentralization of power, delegating to individuals the responsibility for greater efficiency in the work environment. The consequences observed are in the realm of the political-normative orientations found in law no. 391 of May 4th, 2004, concerning continuing professional education of adults, in which can be identified a passage from the logic of education to the logic of professionalization.

This transposition is justified in the discourse of greater approximation between the field of work and education, in which work situations and activities become the direct and indirect means for the education of workers.

The appeal of professional education of adults aimed at the education of citizens and for human and social development is substituted by the concept of education at the service of needs raised by the flexibilization of work, and which seeks to construct a profile of an autonomous, responsible, and adaptable professional. It also seeks to favor the continuous development of competencies that accompany the constant changes found in situations of work and that assure high effectiveness of labor activities. It also establishes the “specification/particularization” of competencies, a multi-tasking profile of the worker and the loss of power of professional associations over the identity of professional profiles. These aspects allow inferring that the meaning of professionalization is related to the discourse of polyvalence.

The field of the concepts of professional education of adults in France is found within a situation of changes and disputes, permeated by contradictions that emerge from ideological views based on distinct questions, according to each social group involved or responsible for promoting education (society, companies, individuals, unions, etc.). At the heart of this ideological dispute, from the perspective of organizations, a logic of competencies that stand out for having accompanied constant changes since the inaugural situations of labor has prevailed.

There is no denying that the logic of competencies has an affinity to and traits of the Human Capital Theory, establishing new contours according to the current needs of capitalist sociability. It is based on the dynamic of competitive markets and on high productivity, which is a function of the adequate development and use of competencies by individuals. According to this logic, the development of competencies in the process of education is the essential foundation and result of the adaptation to the instability promoted by the contemporary capitalist system.

The elements in question converge for a close identification of professionalization with the idea of professional development (Wittorski, 2016): a process highlighted by the development of specific and local competencies, guided by a concept of what would be a “good professional” adopted by the distinct organizations. Education in loco is undertaken during the professional activity of individuals; and through it, professional identity is negotiated - which presupposes the discussion, evaluation, and definition between individuals and organizations of professional qualifications, and involves professional reorientation - which involves the movement of the individuals’ return to educational processes to obtain a new profession, through which they seek to promote the development of knowledge and competencies and the construction of a professional profile. This entire process can also be associated to the idea of professionalization of education (Geay, 2016).

Professionalization understood in this way points to an ambiguous aspect in the invocation as a concept of adult education. At the same time that it indicates an instrumentalist inclination of education for the market, it also questions the limits and fragilities of the essentially scholastic educational format that the professional education of adults historically assumed in the French context.

Geay (2016) also indicates that the background of this idea is the historically constructed hierarchy between theoretical education and practical learning. This idea dates back to the 18th century, when the school format established a specific place for the learning of social practices that, until then, were transmitted through work itself, which led to the devaluation of practical knowledge. Although professional schools had been created in this period, with the pretension of reconnecting practical and intellectual knowledge, this only consolidated the professional practices as applications of scientific and technical knowledge. This is a pedagogical paradigm expressed by the “theory-practice” relationship which became the ultimate foundation of the teaching of professions in the realm of schools.

This educational logic, when adopted in its radicality after World War II, by French institutions dedicated to the professional education of youth and adults, revealed the premise that theoretical knowledge and its transmission pertained to the period of childhood and adolescence, while to adulthood pertained the application of theoretical knowledge (learned in school) in the professional practices. The concept of professional education on this basis contributed to a devaluation of practical learning in relation to studies and represented the effective denial of knowledge from experience and work as educational principles. The counterpart to this logic arose from the economic and social crisis of the 1970s, with the proposal of integrative alternance, as a pedagogical strategy for the professionalization of youth and adults. On the other hand, alternance was born as a disparaged model, as the heir of the devalued status of professional learning.

INTEGRATIVE ALTERNANCE: A COMPLEX SYSTEM FOR PROFESSIONALIZATION

Education in alternance is currently the most important expression of professional education for youth and adults in the French system. It is a pedagogical proposal aimed at professional qualification through an integration between schools or other educational institutions and the world of labor. The development of alternance was an ambitious intention because it sought to articulate various actors and logics and to propose experiential practical knowledge as an educational principle. It is a complex educational proposal offered as a pedagogical alternative to the essentially school-based model which professional education for adults has historically become.

In alternance, organization and temporality can take place in juxtaposition, in negotiation and/or in integration between schools or other educational institutions, companies and the individuals being educated:

Alternance in juxtaposition, education takes place concomitantly in the educational institution and the company. They are two distinct formative logics that operate in parallel and without parameters and objectives common to the two educational institutions. Individuals move between school and company and act under the guidance and criteria of each. There is no dialog between the learnings and educational practices of each. In this type of alternance, it is up to students to promote the synthesis of the learning obtained between the time in school and in the field of labor. The only point in common between the institutions is the presentation of the diploma at the conclusion of the training.

Alternance in negotiation the educational objectives are adjusted between an instructor in the school and a tutor at a company. The process takes place through the guidance of the individuals in the systematization, formalization, and construction of a reference for education. If on the one hand the times and objectives are specific to each institution, on the other hand, the educational process considers what is established in each space as a function of the reference for the education of the individuals. In this case, the individual is guided to practice what is said in the space of education and the activity that is practiced in the workspace and vice-versa. There is recognition of the importance of the learning at each institution without, however, an effective and formalized exchange between them.

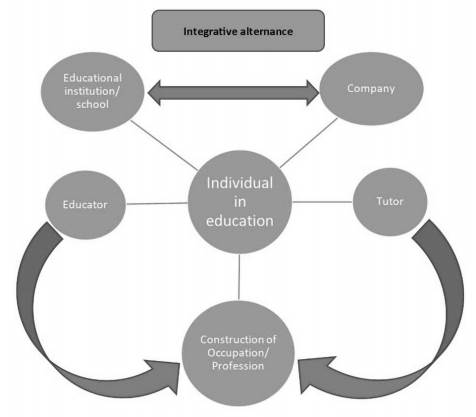

Alternance in integration or integrative alternance promotes effective joint action by the institutions. More than a negotiated education, the organization of time, objectives and proposal of the educational institution and the company are defined in a coordinated manner through dialog. The interaction and integration between the school and the company are intermediated by the instructor and a tutor, respectively. Both move through the institutions, in order to identify and define the role to be played in the formative path. The distinction of the alternance in integration is the construction of the process of professional education by two parties.

The model of integrative alternance, due to its being based on permanent dialog and interaction, reveals a peculiar pedagogical approach to professional education for youth and adults, by engaging proposals and practices of worlds that are traditionally separate. The form of temporal organization between the institutions and the individuals involves a complex integration: the time at the company guides what will be done by the individual during the time of education, at the same time that, what was done and learned in education will determine and organize what is done at the company, as procedures and actions to be undertaken by individuals (Figure 1).

The organization of integrative alternance reveals what constitutes an educational practice with a logic that is different from conventional proposals for professional education, involving distinct actors and logics that attest to its complexity. For Clénet and Roquet (2005), alternance is complex because it responds to three functions that relate individuals and organizations with the world of work, such as: learning, socio-professional integration, and qualification. The need for learning among youth and adults is due to difficulties in schools or professional environments, when the traditional teaching-learning process is not able to resolve the problems presented. The alternance is constructed from educational practices, inverting the traditional school logic of theory and practice. The function of socioprofessional integration takes place when there are ruptures in connections that generate exclusion, a system for reconstruction of the ties of individuals with other people and organizations; and the function of qualification is related to the administration of human resources, employability, and the development of competencies. About this logic, alternance can be understood as a “complex system, with entangled origins that are difficult to dissolve or organize” (Clénet and Roquet, 2005, p. 44).

Complexity, as taught by Morin (2007), is characterized by unpredictability, which takes place in systems that engage human, social, and professional actions, such as education in alternance. They involve unique actions that cannot be completely foreseen, because they respond to the unexpected, to the unprecedented, and also produce unpredictable effects. These actions can be explained and understood when in their context and when one seeks to understand the reasons for the actions of the actors (Geay, 2016).

In a complex system, behavioral modeling is sought in situations that relate to its context, when it is required to identify what is the project, the objectives for determined actions and the effects produced. The intention is not only to resolve problems already foreseen, but to formulate the problem in a situation identified as complex. In the case of education in alternance, as a complex model, the question involves overcoming the simplification caused by learning of techniques in educational institutions, applied to situations and universes that are also complex, given that the logic always involves simplification in handling problems, by means of solutions learned. Integrative alternance acts as an alternative to non-simplification, by confronting the duality between complexity and simplification. The confrontation takes place by means of the proposal to take advantage of real work situations, experiences in loco as the raw material for education, to be able to understand it, model it and have it emerge or appear as a problem. It uses situations that allow expressing dimensions that must be noticed.

The complex system of education in alternance also reveals that understanding and explaining practices and problematizing professional situations establish a rich dialog with an interdisciplinary approach. Interdisciplinarity involves a multi-referential reflection, the crossing of various references, different views and analyses that allow other forms of relating with knowledge and of grasping the complexity of situations. It is also based on a posture of reflexivity of the individuals engaged in education, as a perspective on their own positions in the educational process, and in the situations experienced - practitioners who are also researchers of their practice. The alternance thought of in this way indicates that, in terms of conception, knowledge and practice of real work situations are not faced in juxtaposition, but rather treated in a way to integrate the knowledge from practice and formal knowledge.

For this perspective, alternance is defended by Geay (2016) as a form of response to an excess of schooling in the professional education of adults that is constructed based on a historical polarization between theoretical and practical knowledge and which established a combative opposition between the school world and the world of work. It is a complex system that allows an interface between theory and practice.

Although this opposition was accentuated in the context of a society of services, in which a distinction was established between occupations in the technical and human fields, this model made professional activities more complex, requiring professional profiles with greater initiative, autonomy, and creativity and that carry the design of education by competencies. These changes question the formalized knowledge of schools, as they no longer fully respond to the needs that arise from day-to-day work situations. That is, professional education exclusively in the school model does not allow the construction of a “know-how” that responds to innovations that arise in the work context. From this logic, Geay (2016, p. 77) affirms that “there is a new professionalism, in which schools alone are no longer sufficient. It involves a quite broad practice that is learned in alternance and that it is not possible to learn solely in school”.

With the challenge of responding to the gaps left by the essentially school model in the education of youth and adults, it can be said that this finding is based on the presumption that there is knowledge that is not learned in a formalized and organized way as proposed by schools, but that must be experienced to be learned. Thus, I understand that integrative alternance takes experience as an educational principle.

Experience is presented as a means that allows greater familiarity with work situations and with aspects that cannot be grasped in a school environment. Experience in alternance would be a means for direct initiation, in the work environment, to the occupation chosen, when the individuals in initial or continuing professional education can experience, systematize, and theorize the experience, which is not restricted to a situation of systematized theoretical knowledge supplied by the school.

The centrality given to experience in education by alternance reveals a direct implication in relation to the valorization of the knowledge of practice or the knowledge of doing, as constituents of competencies that cannot be transmitted. In this regard, it is perceived that the education of professional competencies becomes the purpose of alternance, in an attempt to overcome the supremacy of formal knowledge in the professional training of youth and adults.

Thus, the question raised by alternance addresses the dissonance in the visions and logics of education found between the systems of work and school. In the system of work, the production of knowledge is commonly known by its utilitarian character, that is, the validity of the knowledge is subordinate to its utility. On the other hand, the logic of the school system is that of teaching systematized forms of knowledge and developing the acquisition and understanding of this knowledge as a function of their own. The justification for this logic is its later application in practice.

The challenge of alternance is to guarantee that the actors in the process appropriate both functions, in situations in which they occur. By being located in a field of distinct logics with real difficulty of cooperation, alternance requires dialog and a cooperative work environment, which promotes the construction of a formative system in real interface/intercession with the human quality of the process. In this way, the institutional/organizational question is simultaneously a challenge and strategy for making the connection between distinct systems - that is, a catalyst to the demands presented.

A CROSS-EXAMINATION OF PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION OF YOUTH AND ADULTS BETWEEN BRAZIL AND FRANCE: POSSIBLE DIALOGS

By plunging into the conceptual field of professional training of adults in France, I found that there is an identification between the perspective of professionalization, by the mechanism of integrative alternance and the policy of integrated professional education with basic education for adults in Brazil, by means of the PROEJA experience.

Thus, a cross-examination of the policy and experience of integrated professional education in both countries offers an opportunity to reflect on the concept of youth and adult education from the perspective of professional education, at different levels of schoolings.

A first aspect to highlight refers to the dimension of the context of social exclusion in France, and of poverty in Brazil, to which the policies of professional education are linked. In the French realm, the professional education of adults is located at the heart of the crisis of the social welfare State, in which is observed the failure of mechanisms of economic regulation and social policy. The action of the French State is currently focused on the issue of employment, on the logic of employability. Professional education is found amid a crisis of employment and of social policies, in order to respond to business needs and as a form of obtaining greater effectiveness concerning social justice, in an attempt to couple individual rights that encompass employment and social promotion.

In Brazil, professional education is linked to a social context of inequality and poverty, based on an idea of development, considered as economic growth, in which relations of power and environmental limitations are disregarded. Given historical structural unemployment and poverty, the logic of the minimum State and the sovereign market is still imposed through deregulation of this market, flexibilization of labor contracts and privatizations, erasing “the inheritance of the redistributive policies and the mechanisms of social regulation and that of the market” (Frigotto, Ciavatta and Ramos, 2009, p. 1.308). Professional education in Brazil has become one of the formulas to meet the needs imposed by capital, given the instabilities of the market and assuming a relation with development under the imperative of human capital, the society of knowledge and pedagogy of competencies and employability.

From a historical dimension, a distinction is identified between institutionalized policy and policy via program. Professional education in France is based on a reality in which basic education is a universalized right, with an educational system that allows the interface of schooling with professional education, in what would correspond to high school in Brazil. The legal organization of a system of professional education was developed with ideologically inverse perspectives, for adults and youths already initiated in labor activities. At its origin, professional education of adults is understood as a form of adaptation of workers to changes in technology and labor, to support the promotion of and to provide access to all levels of culture and professional qualification, contributing to cultural, social and economic development. Currently, the system is reduced to an economic perspective and education is presented as an individual option and an instrument for insertion, reinsertion, and professional adaptation. Even if the educational system has suffered changes and lost its humanist perspective, it remains part of a coordinated policy in action and is integrated between government, private institutions, companies and worker unions, which reveals its strong level of institutionalization.

In the Brazilian case, there is deep inequality among the population in terms of access to quality basic education. There are high levels of illiteracy and a low level of schooling among the economically active population (EAP). In this context, the policy of professional education is developed without integration or interface with schooling and is based on a reiterated investment of State resources in private-public partnerships. It is found under the near-exclusive control of the country’s corporate System S,7 which offers fast courses under the logic of training.

The historic lack of articulation between professional education and youth and adult education is, therefore, seen by the tenuous actions of the State in guaranteeing schooling associated to professional education to individuals, as workers or potential workers. There are some experiences in the Ministry of Labor in conjunction with union entities such as the Single Workers’ Center (Central Única dos Trabalhadores ― CUT), a national confederation of unions, for example. Although the law of National Education Guidelines and Bases determines in paragraph 3º, of article 37 that youth and adult education should be articulated with professional education, with specific curricula and methodologies, policies for the reintegration of unschooled workers into the fields of school and professional education are practically inexistent. In this regard, Paiva (2009) affirms that professionalization was sought by productive sectors, and that the logic of Brazilian society understood it as a means for the education of the poorest, given that general education to prepare for higher education was aimed at the middle classes and the wealthy. Even when considering professional education at a high school level, those professions for which courses are offered are those that are subaltern in the world of work, without promoting the autonomy of the subjects.

This situation reflects the dichotomy produced between an education that “prepares for the labor market” and that “prepares for life”, reflecting the structural duality between professional and propaedeutic education, which is marked in the history of Brazilian education, as well as the idea that human or professional education is conducted before practice and not in dialog with it. The overcoming of the separation between general education and professional education was thus late to occur, with the proposal PROEJA’s public policy.

This historical review led me to plunge into the dimension of experiences with professional education conducted in an integrated manner by integrative alternance in France and by PROEJA in Brazil, which are conceptually similar, but which move between a pragmatic conceptual logic closer to the world of work, with an eye on employability, and the logic of humanist education focused on the development of the individual and the social, but with low expectation for professional insertion.

Conceptually, in the French context, the perspective for professionalization prevails as an option for adult education, when it calls for greater articulation between professional education and the productive world, with integrative alternance being a preferential mechanism for education in this field. This is a pedagogical device that establishes a relationship between two distinct social worlds - a joint process, in which part of the education occurs in a school institution and another part in the world of work.

In the Brazilian case, government expands the political place of education for youth and adults, organizing it as a modality, no longer restricted to literacy, but guaranteeing its continuity in terms of schooling, in the realm of high school, and even innovating by proposing it in an integrated manner with professional education, by means of PROEJA. The objective of the program is aimed not only at the expansion of the public spaces that offer professional education for adults, but also presents itself as a strategy for the universalization of basic education.

In epistemological terms, the complexity of integrative alternance is recognized by the fact that it proposes to overcome hierarchies between theoretical and practical knowledge, through an integration between the school world and the world of work, as a form of professional education for adults. PROEJA, meanwhile, is based on another logic of complexity, by proposing the curriculum as a form of integration between basic and professional education and the presumptions of the modality of education of youths and adults that recognizes the need to offer a course that considers the experiences and knowledge of individuals until they return to school. Work is the educational principle of the program and also the concrete focus of the understanding of the economic, social, historical, political, and cultural meaning of the sciences, arts, and technology. In this conception of education, in which work is an educational principle, general and specific knowledge and practical knowledge from the world of work are inseparable, complementary, and not hierarchical.

In terms of public policy, integrative alternance is highly institutionalized, and is formally structured and financed by the French State with intersectoral co-participation. Differently from the French experience, PROEJA in Brazil was born under the format of a public policy expressed as a program, with a strategy for gradual budgetary and human resources incorporation at institutions of professional education already established nationally, which foresaw its institutionality and consolidation as a State policy over a few years. Nevertheless, the complex mechanisms for acceptance and assumption of a new public in these teaching institutions did not guarantee the continuity and institutionalization of the policy at the scope of and with the requirements needed by the potential demand from the youth and adult individuals who had not completed elementary schooling. The policy practiced at these institutions recognized that the responsibility of the State for education for all was at the mercy of a political and ideological commitment of the professionals in youth and adult education in the country, without adequately responding to the level of commitment with the service to be provided to the population.

In operational terms, integrative alternance seeks adjustments between school and company, with asymmetrical exchanges, as the adjustments are more often in the realm of the school. This exchange is materialized with the construction of a referential of education, with the active interaction of an educator from the school and a tutor at the company. A beneficial relationship is evidenced between them both, but the school institution - which initially sought the educational process - also agrees to the most significant contributions. From the perspective of the company, integrative alternance facilitates recruitment and preparation of flexible labor. However, the construction of a new institutionality is observed, which imposes challenges for the interlocution between the two spheres and the individuals being educated. In terms of education, studies by Doray and Maroy (2001) indicate that improvements occur through the great adaptation of learning as a function of the targeted employment, by composing a system that has an educational principle in the experiences lived in the work environment, with a strong potential for professional insertion for students.

Similarly, PROEJA also presents challenges to the development of an integrated curricular proposal for youth and adults, through efforts to conduct interdisciplinary work to confront the hierarchy of the so-called scientific knowledge in relation to non-scientific knowledge among students and educators at the institution. The interdisciplinary strategy, implemented through the so-called integrative projects in the case of PROEJA/Federal Institute of Rio de Janeiro ( Instituto Federal do Rio de Janeiro ― IFRJ ), establishes a new form of construction of knowledge, when individuals, based on a theme chosen by a class, articulate and dialog with general and specific knowledge and practices of the course offered.

The articulation with the world of labor is established through the realization of a curricular internship, at the end of the course. The relationship between the educational institution and the company is asymmetrical and there is little dialog about the professional education of students. Approval of a student’s proposal to conduct an internship at a company is made through a technical evaluation by a teacher in the course, while the partnership between the company and the school institution is based on the “quality or not” of the students. The educational exchange and contribution occur in the experience of the students themselves. In this case, schools dialogue with the world of labor through feedback from students and supervisors of the internship at the company, which reveals the essentially scholastic format of the professional education of adults, in the Brazilian case.

WHAT IS LEARNED FROM THE CROSS-EXAMINATION

This cross-examination of integrative alternance in France and PROEJA in Brazil allowed me to reflect that the professional education of adults is related to social and economic development, which indicates that they are both immersed in a dispute over concepts of education and society, reflecting an educational duality and asymmetrical relations between social classes.

This also allowed me to perceive that the development of integrative alternance through approximations between the school world and the world of work allowed identifying a close relationship with professional insertion. In this case, the format of alternance revealed greater potential for insertion than the internship format in companies. This issue has been a critical and fragile point for PROEJA considering the articulation between integrated education and policies of employment and income, for example, for the professional insertion of the individuals served. Efforts to overcome the fragile integration between education and labor policies open paths for the establishment of other bases in the relationship between education and development, which requires serving, in a parallel manner, the criteria of social justice and the needs for economic production.

Another important point involves the concepts that support alternance and PROEJA. Integrative alternance, although presented as a pedagogical strategy aimed at overcoming an excess of schooling and a hierarchy between theoretical and practical knowledge, is based on the development of competencies suitable to employability. PROEJA, distinctly, although in an economic context dominated by neoliberal precepts, establishes the opposite, proposing education in a broad dimension, aimed at allowing individuals access to knowledge and information produced by humanity; an understanding of the world; and insertion in the world of work and better living conditions, but is not limited to this - it is dedicated to providing “education in life and for life” (Brasil, 2007).

Finally, considering that the current Brazilian context of educational reforms and removal of rights appears to converge with the configuration of educational policies that serve interests of markets and capital, I am led to question: What are the perspectives for the policy of integration of basic education with professional education for youth and adults? Will the concept of PROEJA be substituted by the idea of professionalization that is found in France? Does the concept of alternance, which reflects proximity with PROEJA’s educational proposal, present itself as a horizon in the construction of meaning for the education of youth and adults from the perspective of professional education in Brazil?

REFERENCES

ARDOUIN, T. Formation tout au long de la vie et professionnalisation à l’université: le cas des métiers de la formation à l’Université de Rouen. In: SOLAR, C.; HEBRARD, P. (dir.). Professionnalisation et formation des adultes: une perspective universitaire France-Québec. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2008. p. 71-95. [ Links ]

ARDOUIN, T. La formation des adultes: un objet frontière. In: ARDOUIN, T.; ANOOT, E.; BRIQUET-DUHAZÉ, S. Le champ de la formation et de la professionnalisation des adultes: attentes sociales, pratiques, lexique et postures identitaires. Paris: L’Harmattan , 2017. p. 23-37. [ Links ]

BARBIER, J. M.; WITTORSKI, R. La formation des adultes: lieu de recompositions? Revue Française de Pédagogie, Lyon, n. 190, p. 5-14, janv./mars 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://rfp.revues.org/4672 . Acesso em: 17 nov. 2017. https://doi.org/10.4000/rfp.4664 [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 23 dez. 1996. [ Links ]

BRASIL .. Decreto n. 5.840, de 13 de julho de 2006 Institui, no âmbito federal, o Programa Nacional de Integração da Educação Profissional com a Educação Básica na Modalidade de Educação de Jovens e Adultos - PROEJA, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF , 17 jul. 2006. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Educação Tecnológica e Profissional. Programa Nacional de Integração da Educação Profissional com a Educação Básica na Modalidade de Educação de Jovens e Adultos: documento base. Educação profissional técnica de nível médio/ensino médio. Brasília, DF : MEC, 2007. [ Links ]

CLÉNET, J.; ROQUET, P. Conceptions et qualités de l’alternance: modélisation d’une expérience régionale. Education Permanente, Paris, n. 163, p. 43-58, juin 2005. Dossier “L’Alternance: une alternative educative?”. [ Links ]

DORAY, P.; MAROY, C. La construction des relations entre économie et éducation: l’exemple de la formation en alternance. Éducation et Sociétés, n. 7, p. 51-65, 2001. Dossier “Entre éducation et travail: les acteurs de l’insertion”. [ Links ]

FRANCE. Loi n. 71-577, du 16 juillet 1971. D’orientation sur l’enseignement technologique. Journal Officiel de la République Française, France, 1971. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000000875172 . Acesso em: 25 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

FRANCE. Loi n. 2004-391, du 4 mai 2004. Relative à la formation professionnelle tout au long de la vie et au dialogue social. Journal Officiel de la République Française, France, n.105, p. 7.983, 5 mai 2004. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000000613810&categorieLien=id . Acesso em: 25 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

FRIGOTTO, G.; CIAVATTA, M.; RAMOS, M. Vocational educatión ande development. In: MACLEAN, R.; WILSON, D. (ed.). International handbook of education for changing world of work. Germany: UNIVOC; Springer, 2009. p. 1.307-1.319. [ Links ]

GEAY, A. L’alternance comme processus de professionnalisation: implications didactiques. In: WITTORSKI, R. La professionnalisation en formation. Mont-Saint-Aignan: PURH, 2016. p. 75-87. [ Links ]

LE BOTERF, G. De la competénce. Paris: Editions d’Organisation, 1994. [ Links ]

MORIN, E. Introdução ao pensamento complexo. Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2007. [ Links ]

PAIVA, J. Os sentidos do direito à educação para jovens e adultos. Petrópolis: DP et alii; FAPERJ, 2009. [ Links ]

RAMOS, M. É possível uma pedagogia das competências contra-hegemônica? Relações entre pedagogia das competências, construtivismo e neopragmatismo. Trabalho, Educação e Saúde, Rio de Janeiro, v. 1, n. 1, p. 93-114, mar. 2003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1981-77462003000100008 [ Links ]

UNESCO ― Organização das Nações Unidas para a Educação, a Ciência e a Cultura. Declaração de Hamburgo: V Conferência Internacional sobre a Educação de Adultos. Hamburgo: UNESCO, jul. 1997. [ Links ]

WITTORSKI, R. La professionnalisation. Savoirs, Paris, v. 17, n. 2, p. 9-36, 2008. https://doi.org/10.3917/savo.017.0009 [ Links ]

WITTORSKI, R. Les rapports entre professionnalisation et formation. Education Permanente, Paris, n. 188, p. 5-9, 2011. Dossier “Formation et professionnalisation”. [ Links ]

WITTORSKI, R. À propos de la professionnalisation. In: WITTORSKI, R. La professionnalisation en formation. Mont-Saint-Aignan: PURH , 2016. p. 63-74. [ Links ]

1 The original text in Portuguese used the terminology “formação integrada”, which could be literally translated as “integrated formation”. Formação is used as a concept with a somewhat different meaning than educação in Portuguese, but this meaning for “formation” is not found in the Merriam Webster dictionary or general English usage.

2 As expressed by Frigotto, Ciavatta and Ramos (2009, p. 1.310), the term employability originated in the business world, and its meaning is related to a set of knowledge that an individual has or can have in a certain job or outside of it, which leads one to feel capable and productive. It has a meaning opposite to the relation of a lifelong tie to a company, revealing that what is important is the content of what is known or can be known. In this sense, it becomes a synonym for adaptability and security.

3 In the original: “La formation professionnelle continue fait partie de l’éducation permanente. Elle a pour objet de permettre l’adaptation des travailleurs au changement des techniques et des conditions de travail, de favoriser leur promotion sociale par l’accès aux différents niveaux de la culture et de la qualification professionnelle et leur contribution au développement culturel, économique et social”.

4 In the Brazilian context, in turn, the concept of competencies is broadly criticized by groups in the field of work and education, The concept, for Ramos (2003) and Frigotto, Ciavatta and Ramos, 2009, p. 1.310), integrates the capacity of workers to act satisfactorily in real work situations, mobilizing cognitive and socio-affective resources - a response to the society of knowledge, instability, and uncertainty. It incorporates traits of the theory of human capital and redimensions them based on a new capitalist sociability that attributes exclusively to individuals the responsibility to adapt and respond to instabilities of contemporary life.

5 In the original: “La formation professionnelle tout au long de la vie constitue une obligation nationale. La formation professionnelle continue a pour objet de favoriser l’insertion ou la réinsertion professionnelle des travailleurs, de permettre leur maintien dans l’emploi, de favoriser le développement de leurs compétences et l’accès aux différents niveaux de la qualification professionnelle, de contribuer au développement économique et culturel et à leur promotion sociale”.

6 In France, “effectiveness” gained force in the decade of 2000 with reforms to state operations, through the implementation of the Organic law related to the finance of 2001 (Loi organique relative aux lois de finances) and the General review of public policies (Révision générale des politiques publiques), which determined that the State was no longer the “State as means” and became the “the State as result”, a concept that came to guide the administration of all public policies.

7 The System S is a group of entities established by federal law and operates through a percentage of corporate revenues that offer professional training and include the National Industrial Learning Service ( Serviço Nacional de Aprendizagem Industrial ― SENAI); the Social Services for Commerce ( Serviço Social do Comércio ― SESC); Social Services for Industry ( Serviço Social da Indústria ― SESI); and the National Service of Commercial Education ( Serviço Nacional de Aprendizagem Comercial ― SENAC). It also includes the National Service for Rural Education (Serviço Nacional de Aprendizagem Rural ― SENAR); the National Service of Cooperative Education ( Serviço Nacional de Aprendizagem do Cooperativismo no Estado de São Paulo ― SESCOOP); and Social Services for Transportation ( Serviço Social do Transporte ― SEST).

Received: June 09, 2019; Accepted: April 14, 2020

texto en

texto en