Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1413-2478versão On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.25 Rio de Janeiro jan./dez 2020 Epub 15-Out-2020

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782020250042

ARTICLE

Non-white and peripheral teachers: history of teaching in Brazil*

IUniversidade Federal da Paraíba, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil.

IIUniversidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Duque de Caxias, RJ, Brazil.

This is a study on teaching in Brazil under a historical perspective. Based on ethnicity, class, gender, and territory, we analyze the trajectory of teachers in Brazil from the middle of the 19th century to the first decades of the 20th century. We used official documents, newspapers, and photographs as main sources. Theoretical contributions from social history and social history of education grounded the analysis. We concluded that these analytical categories must be included in teaching research, favoring non-white and peripheral teachers who represent a significant part of teachers in Brazil.

KEYWORDS: teaching; non-white teachers; peripheral teachers; history of education

Trata-se de pesquisa sobre a docência no Brasil em perspectiva histórica. Com base em raça, classe, gênero e território, analisam-se trajetórias docentes no Brasil entre metade do século XIX e início do século XX. Utilizam-se documentos oficiais, jornais e fotografias como fontes primárias. Os aportes teóricos da história social e da história social da educação embasam a análise. Conclui-se sobre a urgência de incluir as categorias analíticas abordadas em trabalhos sobre a docência, privilegiando não brancos(as) e periféricos(as), que compuseram importante parte de professores(as) brasileiros(as).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: docência; não brancos(as); periféricos(as); história da educação

Se trata de una investigación sobre la docencia en Brasil desde una perspectiva histórica. A partir de raza, clase, género y territorio, se analizan las trayectorias docentes en Brasil entre mediados del siglo XIX y principios del siglo XX. Los documentos oficiales, periódicos y fotografías se utilizan como fuentes primarias. Las contribuciones teóricas de la historia social y la historia social de la educación apoyan el análisis. Se concluye sobre la urgencia de incluir las categorías analíticas abordadas en los trabajos de docencia, privilegiando a los no blancos y periféricos, que constituían una parte importante de los docentes brasileños.

PALABRAS CLAVE: docencia; non blancos; maestros periféricos; historia de la educación

INTRODUCTION

In her text “Da grafia-desenho da minha mãe, um dos lugares de nascimento de minha escrita” (From my mothers’ writing-drawing, one of the places where my writing was born), writer Conceição Evaristo recalls her first contact with writing during her childhood, having her mother as a teacher. Her mother was a washerwoman in Minas Gerais State in the early 20th century; therefore, she needed sunlight to dry the clothes of her white costumers:

Maybe, the first graphic sign ever introduced to me as writing came from one of my mother’s old gestures. […] I still remember, the pencil was a fork-shaped wood stick, and the paper was the clay mud on the ground right by her legs. Mom would bend and carefully hold and roll-up her skirt, tying it around her thighs and belly. Squatting, with part of her body was almost touching the wet ground, she would draw a huge sun, full of legs. […] It was a writing ritual that included multiple gestures; her whole body would move, not just her fingers. Our bodies moved in space following mom’s footsteps in the page-ground where the sun would be written. That move-writing gesture was a ritual to call up the sun. Creating the star on the ground. (Evaristo, 2007, p. 16)

She also describes her bonds to school and the public library, as well as her schooling, which allowed her to become an elementary school teacher before starting college to study literature - the very reason for her notoriety and acknowledgment. However, the starting point of this trajectory is marked by the learning of a language considered ancestral. She was taught by her first Master, her illiterate black mother, who struggled for her family’s survival. What do these experiences - both mother’s and daughter’s, a future writer who used to be a teacher - tell about the history of teaching in Brazil?

We aimed at presenting the trajectories of non-white and peripheral teachers by analyzing the factors contributing to the historiographic debate about the profession. Teachers’ training, education practices, and the history of their profession are traditional topics in the history of education. The historical perspective of teaching is the object of research, the very axis of scientific conferences, the topic of special issues in journals, and the focus of studies ordered by the History of Education Work Group. On the other hand, the herein proposed topic starts from teachers’ trajectory, but it does not follow a linear and bibliographic perspective (Bourdieu, 1996; Ginzburg, 1991). Based on individual and collective dimensions, such a choice corroborates our understanding of the meaning of becoming a teacher and the construction of teaching practices. This proposition dialogues with the topic addressed in the 39th Annual meeting of the National Association of Post-Graduation and Research in Education (Reunião Anual da Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Educação - ANPEd): “Public Education and Research: Attacks, Struggles, and Resistance”, since the teaching profession in Brazil has been the object of public reflections about the importance of acting as a teacher and the need for policies to value teachers’ training and practices. In contrast, this profession has also been the target of attacks, threats, complaints, distrust, and precariousness.

Research on the history of education, with emphasis on the teaching practices of non-white peripheral individuals, reveals a background of struggles and resistance that go back to the ways in which teachers were instructed and sought to instruct. Antonio Nóvoa warns that the history of the teaching profession “cannot be separated from the place occupied by its members in production relationships and from the role they play in social order maintenance” (Nóvoa, 1991, p. 123). Therefore, besides the importance of national intervention in institutionalizing a field of knowledge and rules for the teaching practice, we highlight the teacher’s performance, the place they hold in social relationships, since “they will not only respond to the social need for education but also create it” (Nóvoa, 1991, p. 123). Thus, from the perspective of these individuals’ history, we will present our investigations about black teachers from the province of Parahyba do Norte in the late 19th century and the Baixada Fluminense region in the early 20th century, analyzing studies carried out by researchers who have been building this history.

We used different sources that had mainly the press and government documents from the 19th and 20th centuries in common. We benefited from the contribution of recent Brazilian research about non-white intellectuals and teachers to substantiate the use of ethnicity and gender concepts, as well as studies on the local history of education to address the territory category (Faria Filho, 2009). Based on E. P. Thompson, we used the concepts of experience, habits, and class as the common theoretical input, and, following a cross-sectional perspective (Davis, 2016), we methodologically assessed ethnicity, gender, territory, and class.

We used the dissertation by Angélica Borges as a methodological reference to search for teachers’ names. She used elementary public school teacher Candido Pardal as a compass to assess life and professional trajectories connected to territory: “accordingly, we must understanding the local dynamics involving schools and their members, the relationships built among teachers, students, and inhabitants, as well as their effects on the schooling process and on the formation of the teaching profession” (Borges, 2014, p. 106). Still on the history of the teaching profession, Marcelo Gomes da Silva’s dissertation (2018) about association practices and networks for teachers’ sociability as “workers of thought” in the First Republic also highlights the methodological possibilities that could be applied to studies on school individuals and their marks in the local history, mainly using the resource of word search in the digital archives of the National Library.

Firstly, we will address the “black” teaching process, and, next, we will use the peripheral territory as a resource to assess the teachers’ trajectories, limiting the research period between the late 19th century and the 1930s.

TEACHERS’ SKIN COLOR AND TRAJECTORIES IN THE 19TH CENTURY

Before the late 20th century, education was usually perceived as an exclusive attribute of the white and wealthy population in different knowledge fields. The lack of records on ethnicity in the most consulted official sources, the idea of educational legislation limiting the participation of non-white individuals in the 19th century, and the synonymy between slaves and black people in analyses about the slavery period were some of the explanations for the scarcity of research about this topic. According to an academic production perspective, during the slavery period, the Law would have prohibited “blacks” (enslaved and free) to have access to school (Mattoso, 2001[1982]; Moysés, 1994; Pinto, 1987).

The history of education also shows that “slaves and free black people” were not allowed at school. Handbooks used in the training of different generations of researchers and teachers did not relate education to the black population, arguing that such an association could not be made before the republican period (Fonseca, 2007). The claim of restrictive legislation was common, and this perspective can still be seen in studies published in a collection about the history of Brazilian education from the 16th to the 21st century. The author stated that “the few urban schools existing at the time would not allow the presence of free black people, let alone slaves. Reading, writing, and counting were very rare skills among slaves” (Maestri, 2004, p. 202). The historian’s interpretation lies in the fact that education could only be associated with slaves in the form of threats and physical punishment, never as school or literacy. In this regard, prior to the republican period, school spaces were forbidden not only for slaves but also for “free black people”. When new investigations started to be published, other explanations for the lack of black people in schools emerged, such as the one advocating that the First Republic expelled black teachers from schools (Müller, 2008) or that the Vargas Era “gradually whitened teaching staffs in Rio de Janeiro” (Dávila, 2006, p. 147). As we will show in the second section of the current study, results from recent research contradict the interpretations of the aforementioned authors.

Investigations carried out in the last few years have contributed to change this scenario. An extensive scientific production conducted in almost all provinces/states of Brazil assessed the literacy universe from different perspectives (students, teachers, teaching material, work, among others) and showed “slight traces of command of reading, writing, and counting” (Bastos, 2016), including among slaves and manumitted individuals, let alone the free black population. Education institutionalization processes were much more complex than previously perceived (Santos and Ananias, 2017; Barros, 2018a; Fonseca, 2007; Gondra and Schueler, 2008; Veiga, 2008).

Initially, the Brazilian student population was not exclusively composed of white individuals. In 1989, Zeila Demartini assessed the memoirs of teachers heard during the investigation about immigrants in São Paulo and found records of black students in the First Republic. Afterward, research on the black population’s access to education emerged, emphasizing the existence of students in public or private institutions. Those judicial conditions were: enslaved or freed. Their ethnicity could be black or multiracial. Finally, their background could be free Africans, Africans’ children or born free from non white brazilian mothers. This plurality pointed to students’ diversity.

The analysis of provincial laws and regulations and the overcoming of issues regarding the association between “slaves” and “black people” helped surpassing previous analyses. Education legislation in the 19th century was diversified; thus, prohibitions in a province, or in a specific year, could not be taken as a general rule during the empire (Barros, 2016). Studies on slavery and abolition carried out in the social history field since the 1980s have contributed to overcoming the synonymy between “black people” and “slaves”. Recent studies addressing the skin color, skills, and conditions of the population highlighted the need to take polysemy into account in the history of education (Barros, 2018b). Non-white individuals could be slaves, as well as free, manumitted, free African, black, and multiracial individuals since the Brazilian population was built over slavery and miscegenation.

Since the early 19th century, diversity was not just observed among students but also among teachers. When reflecting on her pioneering study about a black teacher, Adriana Maria Paulo da Silva mentioned her surprise, at the end of her research, when she found out the “skin color” of the referred teacher. The interest in Pretextato dos Passos e Silva originated from the fact that he was sought-after by families of black and multiracial children, and for his preference for this group of students at the Court, in the 1850s:

The first document I found was Eusébio de Queirós’s granting, and when I found the dossier of teacher Pretextato, I confess, I did not think he was a ‘black’ teacher. It was Pretextato who specified, who detailed his skin color and that of his students. (Silva, 2002, p. 153)

Similar to Pretextato’s, other records of non-white teachers date back to the early imperial period; they also included women. The most illustrious case may be the one of Maria Firmina dos Reis (1822-1917), who is acclaimed by researchers from the literature, history, and black feminism fields due to her work as a writer and for the first Brazilian abolitionist novel. She is seen as the “interpreter of Brazil” (Zin, 2018, p. 10) and attracted the attention of researchers on the history of education for working as an elementary school teacher for more than three decades (Santos, 2016). According to Cruz, Matos and Silva (2018, p. 153),

it was the teaching profession, with progressive women adherence, from the early 19th century, that allowed tracing and expanding the spaces for women in the intellectual field, favoring their participation in the literature and the press, as was the case of Maria Firmina dos Reis.

Although still poorly investigated by the history of education, there are other examples of black teachers, such as Luciana Teixeira de Abreu (1847-1880), who graduated at the Teaching School. She was an elementary school teacher in Porto Alegre, published works in the local press, was part of an important literary society, and advocated for women’s right to higher education (Silveira, 2016, p. 248). Another example was Bernardina Maria Elvira Rich (1872-1942), who was born and worked in Cuiabá. She was the author, editor, and founder of Mato Grosso Federation for Women Progress. Bernardina stood out for her work as a teacher, for discussing women’s issues, and for being an intellectual who reflected on education (Gomes, 2009).

Other studies have focused on the trajectories of black teachers. Philippe José Alberto Junior (1824-1887) attended the Bahia Teaching School and stood out as a teacher in the Court. He was teacher and principal at the Niterói Teaching School and an active abolitionist. His family was closely related to teaching - his wife and children were teachers (Villela, 2012). Hemetério José dos Santos (1858-1939), who was investigated by many generations of researchers (Gomes, 2011; Müller, 2006; Silva, 2015), had a similar trajectory. He was born in Maranhão and moved to Rio de Janeiro. He taught at the Pedro II School and the Rio de Janeiro Military School - he was a Lieutenant Colonel - (Müller, 2006, p. 146), and participated in debates about education and matters concerning skin color (Silva, 2015). Also in Rio de Janeiro, the son of Africans and freed slave Israel Soares (1843-1916) taught at a night school for enslaved and manumitted individuals, standing out as an abolitionist. Israel is also known for fighting against ethnic prejudice in post-abolition years (Silva, 2017).

Two black teachers worked in Bahia at the same time: Carneiro Ribeiro (1839-1920) and Cincinato Franca (1860-1934). The first one was teacher and principal at the Bahia Provincial Lyceum, vice-principal at the Bahia Elementary School, and director of public education. Similar to his contemporary colleagues, he acted on many fronts: he launched the Bahia Academy of Letters, was a member of the Bahia Geography and History Institute, and wrote for newspapers and magazines. Besides, he created the Carneiro Ribeiro Elementary School, where his children also taught later on (Pitanga, 2019). Cincinato Franca, in turn, was a public elementary teacher who worked at night and was an active abolitionist, teaching free and manumitted individuals (Cavalcante, 2016).

The history of education in the province of São Paulo also involves non-white teachers. Antonio Ferreira Cesarino and the sisters Bernardina, Balbina, and Amância directed a school for girls in Campinas, between 1860 and 1875. Perseverança School was a private institution, but it provided scholarships, even for poor children of slave origin. Among other actions, they adhered to the Republican Party because they believed that “with the Republic, the government would implement measures related to popular education and education for freed individuals” (Pereira, 1999, p. 284). Also in São Paulo, José Rubino de Oliveira (1837-1891), a black man of poor origin (Cruz, 2009), studied in the Episcopal Seminar and attended Law School in the Judicial Academy, where, later on, he taught, after participating in nine civil service entrance examinations for the position.

We found references to Felicíssimo Mendes Ribeiro in Minas Gerais. He was a black elementary school teacher in Juiz de Fora, who taught former-slaves in a night school. Moreover, he was concerned with poor students and signed teaching manifestos (Silva, 2013). Felicíssimo was admired by locals, and his name was mentioned in a petition from 1903, in which residents demanded the reopening of the school of the “esteemed teacher, who directs that school, due to his proven skills and dedication to teaching” (Silva, 2013, p. 75).

The prestigious career of Nascimento Moraes (1882-1958) draws attention. He was the son of an enslaved woman and attended high school at the Maranhão Lyceum. He was a private teacher and taught at the Teaching School and the Lyceum. He married another teacher, published many texts in the local press, and stood out as a writer. Target of racist attacks, Nascimento Moraes created his own teaching method and “advocated for social and educational inclusion for the poor” (Cruz, 2016, p. 211).

The aforementioned trajectories have many convergent points, despite regional and temporal specificities and individual matters. As was the case with other teachers, those individuals acted in different spheres (brotherhoods, parties, associations, abolitionist groups), had experience in different levels and types of education (elementary school, high school, higher education, night school), and were writers (literary and theoretical works, manifestos, books, press). Sometimes, they addressed ethnic (discussing being black), class (advocating for education to the poor), and gender (analyzing women topics) issues. Most studies show the role of ethnic belonging in their experiences.

We reflected on Graciliano Fontino Lordão, a teacher from Parahyba in the late 19th century, in an attempt to change how teaching is perceived in Brazil. The main activities of this province were agriculture - sugarcane and cotton - and livestock, which depended on the labor of slaves and free workers. Parahyba faced economic and social crises during the imperial period, mainly due to economic displacements to Southern provinces and to drought seasons, common in the region. Concerns with the workforce, the black participation in the social structure, and the incipient economy were linked to the restlessness of material conditions. Yet, the school expansion in Parahyba was observed through the increase in students and teachers in the 1800s, the number of laws and rules to regulate education practices, and the concern with teaching. We will highlight how being “black” may have influenced the trajectory of a teacher who was acting in this society.

A BLACK TEACHER IN PARAHYBA DO NORTE

Similar to individuals presented in the introduction of this article, Lordão was a non-white man who stood out in the literacy universe, mainly as a teacher. Son of a black woman and a catholic priest, he was prominent in the local society as a teacher and congressman. He also wrote to the local press, acted in public management, owned lands, and used to be called “colonel”.

Awareness about his skin color came from the Homens do Brasil em todos os ramos da atividade e do saber - Paraíba. Volume II: Parahyba (parahybanos ilustres) (Brazilian men in all sorts of activity and knowledge - Paraíba. Volume II: Parahyba (Distinguished Parahyba Citizens) (Bittencourt, 1914). In addition to birth and death announcements, important titles and deeds, the compendium of biographies of distinguished people from Paraíba listed aspects of ethnic belonging in some characters, which are not reported in other personalities (considered white).1 Lordão was described as:

Famous Latinist and teacher. He was born in Parahyba City on August 12, 1844. He dedicated his life to teaching and was a devoted elementary school teacher for many years. Man of good height, but black, he had superior intelligence, great Latinity, was a province congressman form many terms, and held responsible positions in tax-receiver bureaus in Parahyba. On March 13, 1906, he retired as manager of Recebedoria de rendas da Capital do Estado. In this same year, he died. He organized the first Bill of Stamps of the state. He was a member of the Parahyba History and Geography Institute. (Bittencourt, 1914, p. 139, emphasis ours)

The meager text, characteristic of the work, does not fit his trajectory of more than four decades of public life in Parahyba. Lordão attended the Parahyba Lyceum, was a clerk at the Brotherhood of Our Lady of Mercy (for multiracial people), as well as a private Latin teacher, private teacher authorized by the province government, and public elementary school teacher. He lived in different regions of the province, moving to different cities due to his teaching and political careers. He was a member of the Liberal Party, reaching the positions of first state secretary and state congressman. Lordão owned lands in the province’s hinterlands, was granted the title of Lieutenant Colonel in 1891 and acted as a public servant after he retired as a teacher.

He started his “educational training” in the early 1860s and retired in 1888. Beyond his “huge popular prestige” (Tavares, 1907), we must reflect on how his black origin might have affected his teaching trajectory. Most documents or news about him do not allude to his skin color/ethnicity. Despite implying that he was the son of friar Fructuoso, a teacher at the Lyceum, his biography did not mention his skin color, the name of his mother, or that he was a “natural son” (son of a single woman); however, it showed traces of his origin. His necrology recalls: “The obscurity of his birth highlighted his willpower, the value of his merits, the not so common power of his great skills” (Tavares, 1907, p. 21). Would “obscurity” be a metaphor for his origin? According to the biographer, the “old liberal […] brightly crossed the scale of social positions, free from strange support, reaching the very honorable post he held when he died […]” (Tavares, 1907, p. 1). The “scale” as well as being “free from strange support” seem to indicate his accomplishments, despite his “obscure” origin.

Different episodes shine a light on the importance of Lordão’s skin color in his trajectory, which started with his first move to the inland of the province when he was approved for a teaching position. He had tried for the Latin teacher position in the city of Pombal but ranked second in the selection process. In 1865, he was called to work in Cuité. Although approved for teaching Latin, he was assigned to teach elementary school classes. Less than two months later, he requested the Director of Public Education to be nominated for the Latin position in the city of Areia (O Publicador, 12/28/1865). Apparently, his request was not granted; one year later, he was still working as a teacher in Cuité.

This cycle would be repeated again and again; the request for teaching Latin and his permanence as an elementary school teacher. Did his skin color influence the perpetuation of his career at a teaching position of lower prestige? This question has no objective answer, only signs that can help us understand these relations. In an article published “by request” in 1866, an anonymous person praised his work as an elementary school teacher by stating that “Graciliano Fontino Lordão, an acting elementary school teacher in Villa do Cuité, deserves much more respect and consideration, which he has always appreciated, despite the insults of literate fools”. That was the narrative of the “test of Latin art” taken by the “son of Capitan Antonio Gomes Barretto”, a 9-year-old boy, in the city council. According to the author, “the act was quite solemn, given the great number of people from all classes and categories, who came from many places to see the act, never before seen in that village, despite the seat being created in 1836”. After complimenting the “confidence” and “awareness” of the boy, and highlighting the presence of a marching band in the ceremony, the author continued:

That is how our friend prevailed over the unjust who intended to belittle his merit, that is how our friend proves to deserve the trust the president of the province had in him; that is finally how our friend responds to the warmth of the sensible audience that has always appreciated him, becoming even more commendable to parents, more useful to the province, more necessary to his country. (O Publicador, 12/6/1866, emphasis ours)

He praised the teacher by stating that the students “our friend found only knowing how to add and mechanically list some arithmetic rules, he leaves, after nine months of teaching, as masters of Portuguese grammar and well-prepared in accounting”, complimenting him “for his good performance as a teacher” (O Publicador, 12/6/1866).

We do not know who are the “literate fools” who had insulted Lordão, and to whom he had proved his value, but the indication of the presence of “all classes and categories” is intriguing. This mention could refer to skin color or juridical belonging (slaves, manumitted individuals, and free people). What would be the uniqueness of the situation, even with the seat existing for three decades? The teacher’s skin color? Or the fact that the test was taken in the city council? Why would it be so fancy (in the city hall, with a marching band)? Was it the fact that the boy was the son of a local authority? Was it to also publicly test the teacher? Nevertheless, due to the success of the test, the author considered that Lordão “prevailed over the unjust who intended to belittle his merit”, without naming the detractors or exposing the reason for these insults. Did the teacher’s origin bother the local residents? Despite the narrated success, maybe these malicious men were partially responsible for Lordão’s successive attempts to move out of Cuité. Soon after, he was transferred to Pombal and, afterward, to the capital of the province.

In July 1868, Lordão was once again mentioned in the press; this time, responding to a “public criticism” made by an “advertiser” of the conservative-leaning Jornal da Parahyba. In a text published by the competitor newspaper, he answered the accusation of excessive rigor with his students and, at the same time, being “too soft” with his disciples, who had behaved badly in his absence:

It is also my duty to declare to Mr. advertiser, whose name was properly kept secret, that he did not speak the truth when he mentioned that the slave mother of the poor child, severely punished by me, disallowed me in my own classroom due to excessive punishment for her son. She did nothing but ask me whether her son was also involved in the commotion that I had just investigated, to which I answered - yes. However, different from that, I must stress that this is a slander; because (I am not referring to slaves) if anyone dared to dismiss my authority in the performance of my profession, I would have been strong and fierce enough, in the form of law, to fight for my scratched dignity and show to those who believe they must express their opinion that a teacher has superiors to whom those who feel offended can appeal, when it comes to his professional practices. (O Publicador, 7/20/1868)

Besides pointing out the presence of slaves among public school students, the declaration of the teacher was strong concerning the attempt of taking away his “authority”. He advocated that, regardless of the person accusing him (“I am not referring to slaves”), he should be respected, his dignity should be preserved, and complaints about his professional practice should be sent to “higher” instances. Did the effort in positioning himself result from the fact that he was a black teacher? Did his skin color influence the criticism, or was his political stance (at the moment he was already affiliated to the Liberal Party) enough for the conservative newspaper to condemn him? A black teacher having a non-white student in a public school, whose regulations denied the enrollment and attendance of slaves, offers many options for reflection (Barros, 2016). The narrative allows thinking of how black people used to interact with each other during the slavery period and after the abolition.

His teaching period in Campina Grande is an important moment to reflect on his practices. In addition to being a regular elementary school teacher, his performance in the night school was recorded in official documents. In 1873, when listing private establishments with the “humanitarian intention of hosting and educating homeless orphans”, the president of the province stated that “a night school was founded in Campina Grande, taught for free by teacher Graciliano Fontino Lordão, and funded by private individuals who joined for this purpose. - It has 35 students enrolled and regularly attending the classes” (Falla dirigida á..., 1873, p. 23). The class was “taught for free”, and the teacher had no obligation of keeping it. Besides the importance he might have given to the initiative, this was an opportunity to increase his income because, in the following year, he received an annual bonus of 450$000 from the provincial government for his night classes (Concessão de gratificação… 10/14/1873).

Although brief, we should also pay close attention to the time when Lordão lived between Campina Grande and Fagundes, where he also used to teach. The early 1870s were marked by great popular turmoil in the region, and the district was the epicenter of the so-called Quebra-quilos movement. This movement was led by the poor population - white and black people, free individuals and slaves - and spread through Parahyba do Norte and other three provinces (Rio Grande do Norte, Pernambuco, and Alagoas).2 The night class happened within this very context. We have no evidence that Lordão or any of his students participated in Quebra-quilos. However, farmers, cowboys, blacksmiths, construction workers, butchers, and backers formed the social basis of Quebra-quilos (Lima, 2001), and all these professionals attended the night classes at that time.

These examples indicate possible impacts of skin color on the teaching experience and on how to get into this profession. Considering the individual and collective dimensions, Lordão’s trajectory informs about how the experience of being a black teacher affects the constitution of a teacher, the school, and its members. Similar to Lordão, other men and women had their paths marked by the color of their skin during the process of becoming a black teacher in the 19th century, by acting in the production of “protection, cooperation, and reciprocity relationships” (Munhoz and Vidal, 2015, p. 128).

In the next section, we will add the trajectory of peripheral teachers in the 20th century to the discussion, based on a study about teachers from a municipality in Rio de Janeiro State.

PERIPHERIES AND TEACHERS’ TRAJECTORIES IN THE 20TH CENTURY

Due to our investment in research on the local history of education, we investigated women who worked as teachers in Baixada Fluminense, metropolitan area of Rio de Janeiro City. By limiting the municipality of Iguaçu as the study site, the term periphery takes on a historiographic and epistemological meaning. Historiographic because studies on the history of education in Rio de Janeiro State not focused on Rio de Janeiro City, when the state was the center of national politics, are recent. The contemplation of other locations considered peripheral made the term an epistemological invitation for the creation of other scales of observation of individuals and schooling processes (Faria Filho, 2009), posing challenges to the constitution of the document corpus.

The term peripheral refers to a position in relation to what is seen as the core, be it a territory or a situation. Greater value is attributed to what is central, while what is peripheral and marginal carries a certain stigma. We aimed at staying away from this binary and hierarchic logic in order to think about the teaching places related to the history of schooling processes and subjects in certain territories, based on their trajectories, as well as about the stories that address the plurality of work conditions and situations within the teaching profession. The condition of being peripheral, therefore, is cross-sectional (Davis, 2016) and nurtured by the confluence of skin color, gender, and class.

Still on the perspective of the periphery, the territory as scenario given to the researcher should be denaturalized. Different contexts mark the history of Iguaçu in the 1930s. In 1933, political and civil society groups from the first district, Nova Iguaçu, which were favored by the citrus production, had spread a sense of euphoria with the celebrations for the 100th anniversary since the foundation of Vila de Iguaçu. According to researchers focused on Iguaçu History, among the initiatives and celebrations, mayor Sebastião de Arruda Negreiros ordered a collection of pictures of schools and roads from the municipality. The search in school attendance maps of the municipality, which are kept in the Public Archive of Rio de Janeiro State (Arquivo Público do Estado do Rio de Janeiro - APERJ), can help to map public schools from a given region and identifying teachers’ names and titles. Thus, comparing these maps to the original captions of the school pictures, we identified part of the schools and teachers photographed in Iguaçu, in 1933.

After comparing the 74 pictures from the Arruda Negreiros Collection to APERJ documents, we found 19 public elementary schools in the first district, Nova Iguaçu. Among them, 15 had only one teacher in each school. Eight municipal elementary schools had records of teachers approved in civil service entrance examinations and/or graduate teachers, as well as teachers without a degree. In 1933, each of the seven state schools had tenured teachers approved in civil service entrance examinations.

Previous research helped us find “hybrid experiments” of arrangements among school types, organization of school shifts, grades, classes, and number of teachers. These arrangements characterized the constitution of elementary schools in Iguaçu between 1929 and 1949 (Dias, 2014). Records of alterations in the organization of school shifts, grades, and classes corresponded to changes in records of the “adjunct staff”.

Among the school types, we found schools with only one teacher and one or more school shifts, with more than one teacher and only one shift, and with more than one teacher and more than one shift. Out of the four schools from the main-district with more than one teacher in 1933, Rangel Pestana School stood out for the 13 teaching positions registered. Among the 13 teachers of this school, only one was an “acting teacher without a degree”, Maria Amélia Kelly Marques; all others were graduated and approved in civil service entrance examinations.

TEACHING PLACES IN IGUAÇU

The name of teacher Maria Amélia Kelly Marques is found in four different schools between 1929 and 1935. Her admission at mixed high school no. 3 was recorded by the full teacher: “The adjunct teacher Maria Amélia Kelly Marques took office and started working on the 17th, and did not miss work until the 31st” (APERJ, 02712, 03/1931). The main teacher of the school made another note in the following month:

Maria Amélia Kelly Marques - from the 1st to the 7th, and from the 12th to the 31st, missed work on the 8th, 9th, 10th, and 11th because she was transferred to the 28th girl school in Nilópolis, whose transference act was later canceled. She returned to her position in this school under my coordination on the 12th. Carmen Torres Maldonado - Full Teacher. (APERJ, 02712, 04/1931)

In April 1933, Maria Amélia also worked as a non-adjunct acting teacher at the mixed state school no. 33 (APERJ, 02716), and, in June of the same year, she signed the attendance maps at the municipal night school for boys. She also signed the maps at the Nigh School between April and November 1935 (APERJ, 02684). As already mentioned, the name Maria Amélia is in the attendance maps of adjunct teachers from the Rangel Pestana School from June to November 1933, as an acting teacher without a degree, and from May to November 1935, also as an acting teacher. In 1937, Maria Amélia was the substitute teacher without a degree at the mixed high school no. 27, in Nilópolis (APERJ, 02700). We observed these classifications and the possibilities of change between schools when we crossed data from the attendance maps of different schools located in the same territory. This situation was quite common between 1929 and 1949 and demonstrates a continuity in comparison to the previous period in the same municipality.

Isabela Bolorini Jara (2017) assessed public teaching staffs in Iguaçu between 1895 and 1925 and revealed that, due to the rules to start and remain working as a teacher in public state schools, teachers were always susceptible to great mobility within school staffs. They were “cowgirls of education”, since they could be asked to go to schools in different municipalities throughout their careers, either of their own volition or due to the demand from governmental agencies. Different names demonstrated the conditions required to be admitted as a teacher and to build a career as one. Legislation expeditions aimed at standardizing the training, admission, and career conditions for public teachers were also recurrent. A movement that stood out was the “Becoming the State by teaching”, a pillar of elementary school institutionalization. This scenario did not change in the 1930s and 1940s, as shown in our investigation on work situations, locations, nominations, transferences, and teacher licenses based on the teachers’ names found in attendance maps from Iguaçu schools.

The diversity of names given to work situations in municipal and state schools and the displacement of teachers between schools in the region encourage the investigation of individual trajectories, but they also show the dynamics of a movement broader than the experience of school institutionalization. The analysis of the history of individuals in the territory, as illustrated in the trajectories introduced below, allows knowing the aspects of “becoming teaching”.

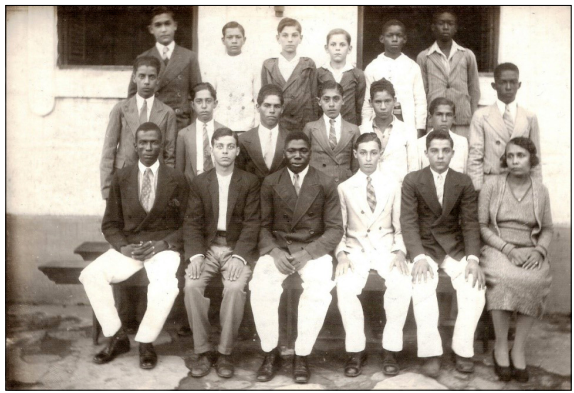

Venina Corrêa taught in other schools from the region before taking office as the principal of Rangel Pestana School, in 1931. She was also in the list of inspectors, and her visits are mentioned in the school attendance maps of the region in 1933 (Figure 1).

Teacher Venina is in the center of the image, she is wearing a floral dress and is seated between the two other teachers.

Figure 1 - Venina Corrêa.

Biographic data mention that she was born in Niterói in 1891. The search for her name in the digital archives of the National Library and in the Iguaçu paper Correio da Lavoura showed her presence in the region since the 1920s and her extensive participation in the social life of Iguaçu. In 1920, she was a teacher in the 14th public school in Paracambi. In 1929, she was a “tenured teacher” at the Mixed School no. 2, in the central area of the municipality (APERJ, 02711). According to records of attendance maps, the Rangel Pestana School was launched in 1931, where Venina remained as principal until 1944. In the press, Venina Corrêa can be found in school activities, tests, and celebrations, as well as other fronts of the Iguaçu society. In 1930, she was mentioned as a member of a group of women who sought the governor of Rio de Janeiro State to discuss the nomination of Iguaçu’s mayor (Em torno da…, 1930, p. 2).

The newspaper Correio de Manhã from July 1933 published the following State Government Deliberation:

Teacher Venina Corrêa has the right to receive, since August 6, 1929 - the day after she reached 20 years as a teacher -, the annual income of 3:600$000, established for teachers with more than 20 years of service, and, since March 1, 1930, the annual income of 4:200$000, determined for elementary school principals in service for more than 20 years, based on the table of decree no. 2383, of January 28, 1929, taking into account what the teacher has already received; the needed credit will remain open. (Actos do governo…, 1933, p. 10)

This excerpt presents a relevant set of data, both because it informs her length of service and date of admission to public schools (1909) - therefore, at the age of 18 - and for indicating the legislation about the teaching career in the 1930s. This information leaves traces that could be followed to map the legislation that regulated public teaching in Rio de Janeiro State in the early 20th century.

When following this clue and searching the 1900-1909 period, we found 70 mentions of the name Venina Corrêa in the digital archives of the National Library. Thus, using this research tool, we could recover aspects of the teacher’s professional career.

In 1905, Venina Corrêa’s request to apply for the admission test to the Teaching School was granted (Escola Normal, 1905a, p. 2). On February 27, she was called for the written test and on the 28, for the oral text. Her enrollment was authorized in March 1905 (Escola Normal, 1905b, p. 1). In the following years, her name was published in calls for written and oral tests for the first, second, and third grades. The types of tests, the content, and students’ results were published on the papers of Niterói and Rio de Janeiro. Her participation as a student in celebrations and tributes also emerged in the routines of the Teaching School; in 1907, the paper published a speech made for the birthday of a teacher from the Niterói Teaching School (Dr. Sebastião Lessa, 1908, p. 2).

Thus, due to her name and trajectory, the temporal edges of the research on teaching expanded beyond the initial study interval: 1933. The understanding of different work situations depends on research about policies focused on the public teacher profession in the Rio de Janeiro State Government at different periods. Therefore, municipalities are a privileged analysis resource to assess the movements to “Becoming the State by making schools” (Dias, 2014) and “Becoming the State by teaching” (Jara, 2017).

For example, by crossing data from attendance maps and pictures, we could identify the same tenured teacher: Maria Paula de Azevedo, who worked in schools in the morning, afternoon, and night shifts. She is the example of a triple-shift case.

She is seen in all school pictures of Mixed School no. 2 and in the picture of the night school no. 2. Assessing the attendance maps, we found the same name, Maria Paula de Azevedo, at the Mixed School no. 2 (APERJ, 02711). She taught at the municipal night school no. 2 between 1931 and 1936 (APERJ, 02707).

Her name remained in the maps of the Mixed School no. 2 (which worked in two shifts in 1933) up to 1938, when Elza Cerqueira, who started signing the maps, informed that the teacher’s departure led to the many students leaving the school. Enrollments had to be organized once again: “This is the reason why the enrollment this month was so low” [sic] (APERJ, 02707, 08/1938) (Figures 2 and 3).

Source: Instituto Histórico e Geográfico de Nova Iguaçu.

Figure 2 - Maria Paula de Azevedo at the Night School no. 2.

Source: Instituto Histórico e Geográfico de Nova Iguaçu.

Figure 3 - Maria Paula de Azevedo at the Mixed School no. 2.

Thus, photographs from the Arruda Negreiros Collection raised questions about the trajectory of non-white teachers, such as Maria Paula de Azevedo. Based on the image below, we also wonder about the presence of a black teacher at the Mixed School no. 9 in Jeronymo de Mesquita (Figure 4).

Camilla Leonidia Netto signed as “tenured teacher” in the attendance maps of the mixed high school in Jeronymo Mesquita (APERJ, 02673) in 1929,1931, and 1932, and as “full teacher” in 1933 and 1935 (there are no maps of 1930 and 1934). We found no biographic data, such as birth date and location. The search for her name in the digital archives revealed that, in 1932, she started receiving a special bonus from the Rio de Janeiro State Government because she reached 30 years of service as a teacher on December 17, 1930 (A professora obteve…, 1932, p. 6).

She attended the Teaching School and was a sophomore student in the 1900 class (Escola Normal, 1900, p. 2). Therefore, based on when she reached 30 years of teaching, we can conclude that her length of service included the period she was still a student in the Teaching School. In January 1902, she took the senior year tests. In January 1903, she finished the program at the Teaching School (Escola Normal de Nictheroy, 1903, p. 2), and in June, she was among the graduate students. The graduation ceremony, in June 1903, counted with the presence of Quintino Bocaiuva, the president of the state, who conducted the event (Escola Normal, 1903, p. 1).

The published note called “Farewell” mentioned her nomination for Iguaçu in 1904: “As Camilla Leonidia Netto, nominated teacher at Piedade Mixed School, in the municipality of Iguaçu, could not, as she wished, personally say goodbye to her friends and acquaintances, she does so through this note” (Despedida, 1904, p. 3). In Iguaçu, Camilla fought to receive her payment from coletoria (tax collector office) for her work as a teacher at the 6th school of the municipality (Diretoria das Finanças, 1904, p. 1). In 1906, at her own request, Camilla was transferred from the 6th Piedade Mixed School to a school in Anchieta, also in Iguaçu (O Fluminense, 1906, p. 1).

Trajectories such as that of Camilla Leonidia and Venina Corrêa, who studied in the Niterói Teaching School and were later nominated to work in Iguaçu, led us to reflect on the displacement demands teaching imposed to women throughout different regions in the Rio de Janeiro State. Teachers could be nominated for more than one school or migrate from school to school. There were many cases of displacement to the capital, Niterói. When we reduced the observation scale (Revel, 1998) to districts in the same municipality, we noticed that a single school would present several changes in the teaching staff throughout months and years; these changes were more acute in schools located in rural areas.

Attendance maps of adjunct teachers hold hundreds of names and work situations. When it comes to the names of substitute, acting, and non-tenured teachers and/or teachers without a degree, information collected from the digital archives is scarce because of the low incidence of publications of public management acts related to them. The instability of their bonds to state or municipal management makes these teachers more peripheral under the lens of research than tenured and full teachers. However, their constant displacement between schools can be tracked based on the crossing of data collected from attendance maps. Thus, the present research reveals the diversity of work situations that reflected the different possibilities of experiences and peripheral places of this profession. The several work situations, migrations between schools, nomination notes, licenses, and transferences were limited by territory and, based on a comparative perspective, we caught the history of these individuals in the gap between structure and process (Thompson, 1981, 1987, 1998, 2001), as they moved and taught, in their trajectories, bets, and rituals, as Conceição Evaristo’s mother used to do: “That move-writing gesture was a ritual to call up the sun. Creating the star on the ground”.

“CREATING THE STAR ON THE GROUND”: BY WAY OF CONCLUSION

Disputes concerning teacher training and teaching practices, and about who and how elementary school teachers must be, remain prevalent. The document Evidências do ENADE e de outras fontes: mudanças no perfil do pedagogo graduado (Evidence from ENADE and other sources - changes in the profile of graduate educators) (Beltrão, Gama and Teixeira, 2018) assesses the supply of teacher training programs, the profile of education graduates, and their participation in the labor market. It presents impressive data that show the impact of guidelines of the Law of Directives and Bases (Lei de Diretrizes e Bases - LDB) no. 9,394/1996 and the “Decade of Education” (1997-2007) on teaching in Brazil. Between revocations and renewals on the obligation of a higher education degree, the number of teaching programs, enrollments, and graduates grew exponentially between 2000 and 2016. The number of traditional (face-to-face) education programs grew by 89.7% - from 837 in 2000 to 1,588 in 2016. Distance learning programs grew by 4,733% - from 3 in 2000 (offered by public institutions) to 145 in 2016; nowadays, the highest supply is found in the private sector. The increasing number of graduates is also expressive, reaching 234% within a 15-year interval (2000-2015) if we take into account all teaching modalities and program types (from 37,083 graduates in 2000 to 123,673 in 2015) (Beltrão, Gama and Teixeira, 2018, p. 41).

The report showed an increase in the search for higher education, but also recorded the persistence of teachers without a degree in classrooms. In the last two decades, schooling, as well as specific and continuing education for pre-school and elementary school teachers, has improved. The number of education programs, enrollments, and graduates also increased significantly.

Another relevant fact concerns the socioeconomic profile: “Education graduates are among the ones who have, on average, the lowest socioeconomic status among the knowledge fields assessed by Enade” (Beltrão, Gama and Teixeira, 2018, p. X). The report highlights that a career in education is still associated with women and the idea that most teachers work “in the first grades of elementary school and in the education field”, despite many of them acting “in high school activities or in activities or not related to the field, but that pay better wages” (Beltrão, Gama and Teixeira, 2018, p. X). According to the diagnosis of wage inequality in overall occupations, although this career is mostly chosen by women, “the few men who work in this field usually earn higher wages” (Beltrão, Gama and Teixeira, 2018, p. 101).

Another study pointed out the increased number of black and multiracial teachers in Brazil in the last decade. According to the research “Profile of Elementary School Teachers”, the progressive growth in the proportion of black teachers might have two explanations, as suggested by the 2014 study conducted by the Inter-Union Department of Statistics and Socio-Economic Studies (Departamento Intersindical de Estatística e Estudos Socioeconômicos - DIEESE): “i) it could be the result of changes in the social structure of the overall population; ii) it could be the result of positive government policies to encourage a higher fraction of the population to acknowledge themselves as black” (Carvalho, 2018, p. 21). For instance, the author shows that among those who work in pre-school, 3.4% self-identified as black and 20.1% as multiracial, in 2009. This number has changed to 4.3% and 24.9%, respectively, in 2017. With respect to teachers of the first grades of elementary school, the incidence was 2.9% (black) and 19.9% (multiracial) in 2009, rising to 4.3% and 26.5%, respectively, in 2017 (Carvalho, 2018, p. 23). The explanations for such changes (that are also perceptible at other levels of elementary and high school and higher education) clearly demand in-depth analysis. Nonetheless, they reinforce the importance of studying gender, ethnicity, and class to build our understanding of the history of the teaching profession in Brazil.

The trajectories described in the current study show how teaching offers the possibility of resistance. It has allowed upward social mobility since the 1800s, not only economically but by the increased respectability, the centrality reached by the teacher in the local society. Teachers hold a crucial position “in the convergence of socioeconomic interests and expectations that are often contradictory: they work for the government as agents that reproduce the dominant social order, but they also embody the hopes of different layers of the population of improving their social status” (Nóvoa, 1991, p. 123). According to Antonio Nóvoa, this position evidences the ambiguity and the importance of this profession: “cultural agents who are also political agents” (Nóvoa, 1991, p. 124).

The closeness of these individuals with the political, management, art, and culture universes is observed in the experiences of Maria Firmina dos Reis or Venina Corrêa and other non-white individuals descendants of enslaved or freed women, coming from lower classes of society, who had to move through peripheral schools.

In the 21st century, teaching remains a possible choice for working-class children; through education, they become teachers who resist the barbarian process. Teachers create a social demand for schooling for all by demanding their own education. University, which is a privileged space for this initial and continuing education, is under attack due to the democratic advancement that involved the inclusion of non-white and peripheral individuals as undergraduate and graduate students, teachers, and professors.

Conceição Evaristo, when reflecting on the genesis of her writing and the image of her mother drawing the sun on the ground and keeping a dairy, wondered about what would make “[…] certain women, born and raised in illiterate or, at most, semi-literate environments, break with the passivity of reading and search for the movement of writing?” (Evaristo, 2007, p. 21). As an attempt to answer, she contemplates:

maybe, these women (like me) have realized that if the act of reading allows understanding the world, the act of writing exceeds the limits of the perception of life. Writing, presupposes a specific dynamism of the writer, enabling them to leave their own mark in the world. (Evaristo, 2007, p. 21)

Conceição Evaristo states that, as a black woman, the act of writing is an act of insubordination: “Our experience with writing cannot be read as ‘lullabies for landowners’, but as ways to disturb them in their unjust sleep”. We also understand that teaching, as an authorship and an enrollment, faces daily demands to resist and revolt, to disturb the landowners in their unjust sleep by creating the star on the ground.

REFERENCES

A PROFESSORA OBTEVE gratificação adicional. Correio da Manhã, Rio de Janeiro, p. 6, 25 set. 1932. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/DocReader.aspx?bib=089842_04&pesq=%22Camilla%20Leonidia%20Netto%20%22&pasta=ano%20193 . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

ACTOS DO GOVERNO Fluminense. Correio da Manhã, Rio de Janeiro, p. 10, 23 jul. 1933. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=089842_04&pasta=ano%20193&pesq=professora%20Venina&pagfis=17545 . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

SANTOS, L. R. M. M; ANANIAS, M. Talvez vos embarace o numero de meninos pobres que deve admittir cada aula: instrução pública primária - Província da Parahyba do Norte - 1849-1889. Revista HISTEDBR On-Line, Campinas, v. 17, n. 1, p. 117-138, 2017. https://doi.org/10.20396/rho.v17i71.8645825 [ Links ]

BARROS, S. A. P. Escravos, libertos, filhos de africanos livres, não livres, pretos, ingênuos: negros nas legislações educacionais do XIX. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 42, n. 3, p. 591-605, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-9702201609141039 [ Links ]

BARROS, S. A. P. História da educação da população negra: entre silenciamento e resistência. Pensar a Educação em Revista, ano 3, v. 4, p. 3-29, jan./mar. 2018a. [ Links ]

BARROS, S. A. P. Ser negro na Parahyba do Norte: cores, condições, qualidades e universo letrado no século XIX. Estudos Ibero-Americanos, Porto Alegre, v. 44, n. 3, p. 484-500, 2018b. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-864X.2018.3.29337 [ Links ]

BASTOS, M. H. C. A educação dos escravos e libertos no Brasil: vestígios esparsos do domínio do ler, escrever e contar (séculos XVI a XIX). Cadernos de História da Educação, Uberlândia, v. 15, n. 2, p. 743-768, maio/ago. 2016. https://doi.org/10.14393/che-v15n2-2016-15 [ Links ]

BELTRÃO, K. I.; GAMA, M. C. S. S.; TEIXEIRA, M. D. P. Evidências do ENADE e de outras fontes: mudanças no perfil do pedagogo graduado. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Cesgranrio, 2018. [ Links ]

BITTENCOURT, L. Homens do Brasil em todos os ramos da atividade e do saber - Paraíba. Volume II: Parahyba (Parahybanos Illustres). Rio de Janeiro: Livraria e Papelaria Gomes Pereira Editor, 1914. [ Links ]

BORGES, A. A urdidura do magistério primário na corte imperial: um professor na trama de relações e agências. 2014. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2014. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. A ilusão biográfica. In: AMADO, J.; FERREIRA, M. (org.). Usos e abusos da história oral. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 1996. p. 183-191. [ Links ]

CARVALHO, M. R. V. Perfil do professor da educação básica. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2018. (Série Documental, 41). Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.inep.gov.br/documents/186968/486324/Perfil+do+Professor+da+Educação+Básica/6b636752-855f-4402-b7d7-b9a43ccffd3e?version=1.4 . Acesso em: 10 out. 2019. [ Links ]

CAVALCANTE, I. A. A Athenas brasileira no pós-abolição: experiências na escolarização pública primária. Revista HISTEDBR On-line, Campinas, v. 16, n. 68, p. 32-56, jun. 2016. https://doi.org/10.20396/rho.v16i68.8643973 [ Links ]

CONCESSÃO DE GRATIFICAÇÃO por Benedicto Henriques. João Pessoa: Arquivo Histórico Waldemar Bispo Duarte, documentos diversos, 14 out. 1873. [ Links ]

CRUZ, M. S. A produção da invisibilidade intelectual do professor negro Nascimento Moraes na história literária maranhense, no início do século XX. Revista Brasileira de História, São Paulo, v. 36, n. 73, p. 209-230, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-93472016v36n73_011 [ Links ]

CRUZ, M. S.; MATOS, É. L.; SILVA, E. H. “Exma. Sra. d. Maria Firmina dos Reis, distinta literária maranhense”: a notoriedade de uma professora afrodescendente no século XIX. CEMOrOc-Feusp/Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, p. 151-166, set./dez. 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.hottopos.com/notand48/151-166Marileia.pdf . Acesso em: 10 out. 2019. [ Links ]

CRUZ, R. S. Negros e educação: as trajetórias e estratégias de dois professores da Faculdade de Direito de São Paulo nos séculos XIX e XX. 2009. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2009. [ Links ]

DÁVILA, J. Diploma de brancura: política social e racial no Brasil - 1917-1945. São Paulo: UNESP, 2006. [ Links ]

DAVIS, A. Mulheres, raça e classe. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2016. [ Links ]

DIAS, A. Entre laranjas e letras: processos de escolarização no distrito-sede de Nova Iguaçu (1916 - 1950). Rio de Janeiro: Quartet; FAPERJ, 2014. [ Links ]

DIRETORIA DAS FINANÇAS. O Fluminense, Niterói, p. 1, 22 jul. 1904. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/DocReader.aspx?bib=100439_04&Pesq=%22Camilla%20Leonidia%20Netto%20%22&pagfis=6017 . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

DEMARTINI, Z. B. F. A escolarização da população negra na cidade de São Paulo nas primeiras décadas do século XX. Revista da ANDE, São Paulo, n. 14, p. 51-60, 1989. [ Links ]

DESPEDIDA. O Fluminense, Niterói, ano XXVII, n. 5.584, p. 3, 16 jun. 1904. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/DocReader.aspx?bib=100439_04&Pesq=%22Camilla%20Leonidia%20Netto%20%22&pagfis=5863 . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

DR. SEBASTIÃO LESSA. O Fluminense, Niterói, p. 2, 24 jan. 1908. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/DocReader.aspx?bib=100439_04&PagFis=6864&Pesq=%22venina%20corr%C3%AAa%22 . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

EM TORNO DA nomeação do prefeito de Nova Iguassú. A Esquerda, Rio de Janeiro, p. 2, 13 dez. 1930. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=297984&pasta=ano%20193&pesq=%20Venina . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

ESCOLA NORMAL. O Fluminense, Niterói, p. 2, 28 dez. 1900. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/DocReader.aspx?bib=100439_04&pesq=%22Camilla%20Leonidia%20Netto%20%22&pasta=ano%20190 . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

ESCOLA NORMAL. O Fluminense, Niterói, p. 1, 21 jun. 1903. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/DocReader.aspx?bib=100439_04&pesq=%22Camilla%20Leonidia%20Netto%20%22&pasta=ano%20190 . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

ESCOLA NORMAL. O Fluminense, Niterói, p. 2, 18 fev. 1905a. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/DocReader.aspx?bib=100439_04&PagFis=6864&Pesq=%22venina%20corr%C3%AAa%22 . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

ESCOLA NORMAL. O Fluminense, Niterói, p. 1, 1 mar. 1905b. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/DocReader.aspx?bib=100439_04&PagFis=6864&Pesq=%22venina%20corr%C3%AAa%22 . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

ESCOLA NORMAL DE Nictheroy. A Capital, Niterói, p. 2, 31 jan. 1903. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=223085&pasta=ano%20190&pesq=camilla%20leonidia . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

EVARISTO, C. Da grafia-desenho da minha mãe, um dos lugares de nascimento de minha escrita. In: ALEXANDRE, M. A. (org.). Representações performáticas brasileiras: teorias, práticas e suas interfaces. Belo Horizonte: Mazza Edições, 2007. p. 16-21. [ Links ]

FALLA DIRIGIDA Á Assembléa Legislativa Provincial da Parahyba do Norte pelo exm. sr. presidente da provincia, dr. Francisco Teixeira de Sá, em 6 de setembro de 1873. Parahyba: Typ. dos Herdeiros de José R. da Costa, 1873. p. 23. [ Links ]

FARIA FILHO, L. M. História da educação e história regional: experiências, dúvidas e perspectivas. In: MENDONÇA, A. W. C. P. et al. (org.). História da educação: desafios teóricos e empíricos. Niterói: Editora Federal Fluminense, 2009. p. 57-66 [ Links ]

FONSECA, M. V. A arte de construir o invisível: o negro na historiografia educacional brasileira. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Maringá, v. 7, n. 1 [13], p. 11-50, jan./abr. 2007. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, C. O nome e o como: troca desigual e mercado historiográfico. In: GINZBURG, C. A micro-história e outros ensaios. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Bertrand Brasil, 1991. p. 169-178. [ Links ]

GOMES, M. M. Hemetério dos Santos: o posicionamento do intelectual negro a partir das obras Pretidão de amor e Carta aos Maranhenses. Revista Cantareira, Niterói, 15. ed., s./p. jul./dez. 2011. [ Links ]

GOMES, N. C. B. Uma professora negra em Cuiabá na Primeira República: limites e possibilidades. 2009. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, 2009. [ Links ]

GONDRA, J.; SCHUELER, A. F. M. Educação, poder e sociedade no Império brasileiro. São Paulo: Cortez, 2008. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO HISTÓRICO E GEOGRÁFICO DE NOVA IGUAÇU. Nova Iguaçu, Rio de Janeiro. [ Links ]

JARA, I. B. O fazer-se Estado e fazer-se magistério em Iguaçu: funcionarização, agências e experiências (1895-1925). 2017. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Cultura e Comunicação, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2017. [ Links ]

LIMA, L. M. Derramando susto: os escravos e o Quebra-quilos em Campina Grande. 2001. Dissertação (Mestrado em História) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2001. [ Links ]

MAESTRI, M. A Pedagogia do medo: disciplina, aprendizado e trabalho na escravidão brasileira. In: STEPHANOU, M.; BASTOS, M. H. C. (org.). Histórias e memórias da educação no Brasil. Séculos XVI-XVIII. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes, 2004. p. 192-209. [ Links ]

MATTOSO, K. Q. Ser escravo no Brasil. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 2001 [1982]. [ Links ]

MOYSÉS, S. M. A. Leitura e apropriação de textos por escravos e libertos no Brasil do século XIX. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, n. 48, p. 200-213, ago. 1994. [ Links ]

MÜLLER, M. L. R. Pretidão de amor. In: OLIVEIRA, I. (org.). Cor e magistério. Rio de Janeiro: Quartet; Niterói: UFF, 2006. p. 151-161. [ Links ]

MÜLLER, M. L. R. A cor da escola: imagens da Primeira República. Cuiabá: Entrelinhas; Editora da UFMT, 2008. [ Links ]

MUNHOZ, F. G.; VIDAL, D. G. Experiência docente e transmissão familiar do magistério no Brasil. Revista Mexicana de Historia de la Educación, Cidade do México, v. III, n. 6, p. 125-157, 2015. [ Links ]

NÓVOA, A. Para o estudo sócio-histórico da gênese e desenvolvimento da profissão docente. Teoria & Educação, Porto Alegre, 4, p. 109-139, 1991. [ Links ]

O FLUMINENSE, Niterói, ano 29, n. 6.244, p. 1, 12 abr. 1906. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/DocReader.aspx?bib=100439_04&pesq=%22Camilla%20Leonidia%20Netto%20%22&pasta=ano%20190&pagfis=8529 . Acesso em: 20 jun. 2017. [ Links ]

O PUBLICADOR, Cidade da Paraíba, 28 dez. 1865. [ Links ]

O PUBLICADOR, Cidade da Paraíba, 6 dez. 1866. [ Links ]

O PUBLICADOR, Correspondencia. Parahyba do Norte, p. 2, 20 jul. 1868. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://memoria.bn.br/DocReader/docreader.aspx?bib=215481&pesq=%22Cumpre-me%20tambem%20declarar%22&pagfis=4340 . Acesso em: 20 ago. 2019. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, J. G. Colégio São Benedito: a escola na construção da cidadania. In: NASCIMENTO, T. A. Q. R. (org.). Memórias da Educação: Campinas (1850-1860). Campinas: Centro de Memória da Unicamp; Editora da Unicamp, 1999. p. 275-312. [ Links ]

PINTO, R. P. A educação do negro: uma revisão da bibliografia. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, n. 62, p. 3-34, ago. 1987. [ Links ]

PITANGA, I. L. Ernesto Carneiro Ribeiro: a trajetória intelectual do professor negro baiano. In: SIMPÓSIO NACIONAL DE HISTÓRIA ANPUH, 30., 2019, Recife. Anais [...]. Recife: UFPE, 2019. [ Links ]

REVEL, J. Microanálise e construção do social. In: REVEL, J. Jogos de escalas: a experiência da micro-análise. Rio de Janeiro: FGV, 1998. p. 15-38. [ Links ]

SANTOS, C. S. A escritora Maria Firmina dos Reis: história e memória de uma professora no Maranhão do século XIX. 2016. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2016. [ Links ]

SILVA, A. L. Pela liberdade e contra o preconceito de cor: a trajetória de Israel Soares. Revista Eletrônica Documento/Monumento, Cuiabá, v. 21, 2017. [ Links ]

SILVA, A. M. P. A escola de Pretextato dos Passos e Silva: questões a respeito das práticas de escolarização no mundo escravista. Revista Brasileira de História da Educação, Maringá, v. 2, n. 2 [4], p. 145-166, jul./dez. 2002. [ Links ]

SILVA, L. S. “Etymologias Preto”: Hemetério José dos Santos e as questões raciais de seu tempo. (1888-1920). Rio de Janeiro. 2015. Dissertação (Mestrado em Relações Étnico-Raciais) - Centro Federal de Educação Tecnológica Celso Suckow da Fonseca, Rio de Janeiro, 2015. [ Links ]

SILVA, M. G. “Pouco letrado” ou intelectual? As ações do professor Felicíssimo Mendes Ribeiro na cidade de Juiz de Fora na virada para o século XX. Revista Eletrônica Documento/Monumento, Cuiabá, v. 9, n. 1, out. 2013. [ Links ]

SILVA, M. G. “Operários do pensamento”: trajetórias, sociabilidades e experiências de organização docente de homens e mulheres no Rio de Janeiro (1900-1937). 2018. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, 2018. [ Links ]

SILVEIRA, C. D. M. Mulheres e vida pública em Porto Alegre no século XIX. Revista Estudos Feministas, Florianópolis, v. 24, n. 1, p. 239-260, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/1805-9584-2016v24n1p239 [ Links ]

TAVARES, J. L. Traços biográficos do Capitão Graciliano Fontino Lordão. Paraíba do Norte: Tipografia Colombo, 1907. [ Links ]

THOMPSON, E. P. A miséria da teoria. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1981. [ Links ]

THOMPSON, E. P. A formação da classe operária inglesa. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1987. [ Links ]

THOMPSON, E. P. Costumes em comum: estudos sobre a cultura popular tradicional. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1998. [ Links ]

THOMPSON, E. P. Folklore, antropologia e história social. In: THOMPSON, E. P. As peculiaridades dos ingleses e outros artigos. Campinas: UNICAMP, 2001. p. 227-268. [ Links ]

VEIGA, C. G. Escola pública para os negros e os pobres no Brasil: uma invenção imperial. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 13, n. 39, p. 502-516, dez. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782008000300007 [ Links ]

VILLELA, H. O. S. A trajetória de um professor negro no Brasil escravocrata. In: OLIVEIRA, I. (org.). Relações raciais no contexto social, na Educação e na Saúde. Brasil, Cuba, Colômbia e África do Sul. Rio de Janeiro: Quartet , 2012. p. 115-132. [ Links ]

ZIN, R. B. Maria Firmina dos Reis, intérprete do Brasil. In: REIS, M. F. Úrsula. Porto Alegre: Zouk, 2018. p. 7-12. [ Links ]

*This paper is a version of the work written for GT02 History of Education, and presented in the 39th Annual Meeting of ANPED in 2019. We chose to keep the original title, defined by the Work Group Coordination at the time of invitation.

1 Among the non-white biographees, some have acted as teachers, such as Cícero Brasiliense de Moura (1863), “teacher, lawyer, and journalist” “of mixed blood […] lives in his retreat, from where he leaves only when forced by circumstances: to teach at the Lyceum or at the Teaching School” (Bittencourt, 1914, p. 111). Cardoso Vieira (1848-1880), who taught at the Parahyba Lyceum, was “a mixed-race man of superior intelligence and maximum erudition”, “great in juridical culture, as a lawyer, journalist, and speaker”, and “extremely proud, perhaps thanks to the ingratitude to his color”; “he was very talented and had vast erudition, which, in part, mitigated that moral trait” (Bittencourt, 1914, p. 111).

2 Some imperial measures were the trigger - Recruitment Law and standardization of weights and measures, with the adoption of the French metric system. The population felt threatened and, fearing that they would become slaves (Lima, 2001), they rebelled burning papers, setting registry offices on fire, breaking weight and measurement tools.

Received: December 21, 2019; Accepted: April 15, 2020

texto em

texto em