Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1413-2478versão On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.26 Rio de Janeiro 2021 Epub 08-Out-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782021260064

ARTICLE

Criticism to the erasing of women in industrial education: the history of female insertion in the Federal Technical School of Espírito Santo (1950-1970)

IUniversidade Federal do Espírito Santos, Vitória, ES, Brazil.

IIUniversidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói, RJ, Brazil.

IIIInstituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

We analyzed the insertion of women in education and in Brazilian society, based on their access and permanence in industrial education courses at a federal institution in the period from 1950 to 1970. By comparing and crossing the sources, we question the version official about the beginning of female participation in the group of students that would have occurred in the 1970s when the institution was already called Federal Technical School of Espírito Santo. However, operating methodologically with the intertextuality of documents and photographs, on the one hand, we highlight attempts to erase the processes of exclusion of women in this historical context and, on the other hand, we conclude that the beginning of female insertion had occurred well before, even in the years 1950, when the teaching unit was still named Escola Técnica de Vitória.

KEYWORDS female insertion; historiography; photography; Federal Technical School of Espírito Santo

Analisamos a inserção da mulher na educação e na sociedade brasileira por meio de seu acesso e sua permanência em cursos de ensino industrial em uma instituição da rede federal no período de 1950 a 1970. Por meio da comparação e do cruzamento das fontes, questionamos a versão oficial sobre o início da participação do sexo feminino no conjunto do corpo discente, que teria ocorrido na década de 1970, quando a instituição já se denominava Escola Técnica Federal do Espírito Santo. Entretanto, operando metodologicamente com a intertextualidade de documentos e fotografias, de um lado, evidenciamos as tentativas de apagamento dos processos de exclusão do sexo feminino desse contexto histórico e, por outro, concluímos que o início da inserção feminina já ocorrera bem antes, ainda nos anos de 1950, quando a unidade de ensino ainda se nomeava Escola Técnica de Vitória.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE inserção feminina; historiografia; fotografia; Escola Técnica Federal do Espírito Santo

Analizamos la inserción de las mujeres en la educación y en la sociedad brasileña, a partir de su acceso y permanencia en los cursos de educación industrial en una institución federal en el período de 1950 a 1970. Al comparar y cruzar las fuentes, cuestionamos la versión oficial sobre el inicio de la participación femenina en el grupo de estudiantes que habría ocurrido en la década de 1970 cuando la institución ya se llamaba Escola Técnica Federal do Espírito Santo. Sin embargo, operando metodológicamente con la intertextualidad de documentos y fotografías, por un lado, destacamos los intentos de borrar los procesos de exclusión de las mujeres en este contexto histórico y, por otro lado, concluimos que el inicio de la inserción femenina ya se había dado mucho antes, incluso en los años 1950, cuando la unidad didáctica todavía se llamaba Escola Técnica de Vitória.

PALAVRAS CLAVE inserción femenina; historiografía; fotografía; Escuela Técnica Federal de Espírito Santo

INTRODUCTION

The theoretical-methodological debate on the use of photography as a historical source, in the context of female insertion in industrial education, necessarily involves the relationship between the conceptions of history and photography. It also consists in the field of articulation between historiographic knowledge and the aesthetic expression of the visual record of human social existence. Incorporating some elements of the field of history developed by Benjamin (1987), Ginzburg (1989), Bloch (2001), Hobsbawm (2003) and Fontes (2014), and in tune with historical-dialectical materialism via Malerba (2006) and Saffioti (2013), we sought to problematize hegemonic versions of the current historical periodization of female presence in industrial education, in the period between 1940 and 1970, in the Brazilian federal system of professional education.

We focus upon the historical trajectory of the current Intituto Federal do Espírito Santo (IFES) [Federal Institute of Espírito Santo] as object of analysis. The institute arises in 1910, then known as Escola de Aprendizes Artífices do Espírito Santo [School of Artisan Apprentices of Espírito Santo], product of the national policy of the president at the time, Nilo Peçanha, who gave rise to the federal system of professional and technological education in 1909. The institution became Escola Técnica de Vitória (ETV) [Technical School of Vitória] in 1942, and, later, in 1965, it became known as Escola Técnica Federal do Estado do Espírito Santo (ETFES) [Federal Technical School of the State of Espírito Santo]. After its denomination was changed again in 1998 to Centro Federal de Educação Tecnológica do Espírito Santo [Federal Center for Technological Education of Espírito Santo], in 2011, it was finally refounded as IFES, a component of the federal system of education, and remains so until today. Operating with the concepts of mediation by Ciavatta (2004), of intertextuality by Mauad (2008) and of ideology by Kossoy (2000), applied to photograph as an object, we intend to point out some of the limits of the validity of information present in photographic images, relativizing its value as a historical source in comparison with other documentary sources on the educational process in the space-time under discussion.

In order to analyze the social insertion of women in the history of Brazil, we take as a basis the work of Heleieth Saffioti (2013), who highlights the historical role of education in the process of constituting inequality between men and women. The author explains how, in the historical process, the access of women to work and education is developed and articulated in order to define, impose, maintain, deepen and/or reproduce, in each phase, the more or less distinct roles between men and women in Brazilian society.

For the author, in colonial Brazil, and even in the empire, when social and economic life was located in rural areas and women’s lives were restricted to the private space, the school offer for female contingents was residual (in small numbers and in a smaller proportion when compared to men), segregated (confined to certain spaces without coeducation), private (without universal public structure), religious (in Catholic and Protestant spaces), of a welfare nature (in spaces such as orphanages) and limited (granting only the most elementary levels of instruction with bias in preparation for domestic work). But when this school offer deepens and intensifies, in Brazil as a whole or in certain spaces considered more developed, the combination of the elements constituting the social, cultural and economic insertion of women changes.

For the author, with the advent of coeducation1, despite the opposing forces, as the school offer developed, an increasing number of women gained access to education, resulting in the progressive redefinition of the social roles of men and women and a greater equality of gender relations (Saffioti, 2013). But the same author warns that this process was neither linear nor progressive, being developed in slow steps, with blockages and antagonizing reactions. According to the author, until 1930, the frequency of girls in high school was extremely low, not only because of the scarcity of this type of educational institution, but especially because of the low implementation of the coeducation regime that often assigned remnant sits to women, with preference to underaged girls (Azevedo, 1964 apudSaffioti, 2013).

In vocational education, the specific context of this study, female insertion, even before the 1930s, took place in favor of semi-professional education segregated to domestic activities or linked to music, sewing, headgear or clothing. In general, educational activities happened in female-only spaces, such as convents, girls’ schools etc. But what interests us here is how this happened, and, especially, the reaction to the first movements of democratization of female insertion in predominantly male spaces, whether in industrial production or vocational education, linked both to industry and to industrial schools.

According to Saffioti (2013), the later insertion in industrial education, or even in industrial work, did not represent the overcoming of the structural condition of female subalternity in Brazilian society. In any case, the delay in the democratization of educational opportunities for women is explained, on the one hand, by the numerous ties to the widespread dissemination of coeducation, and, on the other hand, by the conservation of productive spaces as exclusive to men, which has served to maintain the relations between men and women in Brazil archaic and deeply unequal.

In this sense, not attributing to industrial work the power to equate women and men for performing more valued complex work in society, but considering the insertion into a typically male educational world, as an important stronghold of machismo and the exclusion of women, we observe that analyzing, through historiography, the moments in which this insertion took place and how it took place is relevant from the historical and historiographical point of view. We intend to demonstrate the way in which the “official memory” of an institution at the local level, like others at the national level2, tends to hide the way in which they reacted negatively to the first attempts to democratize women’s access to education in general and to industrial education in particular.

In our hypothesis, there was a process of erasing the concrete experience of the initial insertion of women in a specific time-space under analysis, since the “official” memory treats this subject by denying historical facts so as not to have to explain how the process took place. Thus, the first attempts of admission of women were taken institutionally as non-existent or unsuccessful, and the causes attributed to the students themselves, who would not have manifested “inclinations to the occupation”, which can only be overcome by a detailed process of historiographic reconstruction and problematization of the documentation available. To this end, the use of only a few documents was not enough, but the cross-checking of photographic images with school records, taken as primary historical sources as a whole, as taught by Bloch (2001) and Mauad (2008), helped us to understand how the historiographical object under discussion occurred. The secondary sources, however, fed an “official memory” that served to hide the initial attempts of insertion of women, also erasing the practices of exclusion based on the values of masculinity and meritocracy, still present in the institution, a current example of the quality of public education in the country.

THEORETICAL-METHODOLOGICAL DISCUSSIONS

Based on assumptions of historical-dialectical materialism, the theoretical-methodological basis of our analyses, we took the contradiction capital/work, in its interface with the matter of gender, in order to critically portray the official memory of the historical trajectory of the emergence of women’s presence in an important industrial education institution.

Organizing historical sources with the goal of producing a structured historiography, in procedures of document analysis of images and school records of the centennial institution, we sought to operate with a conception of history taken as a method and as a process, in which the phenomenon under analysis is problematized in its movement of being and its becoming, with a view of its genesis and its development. For this conception, the historical investigation takes the records of images and the school flow as traces that enable the inductive-analytical reconstitution of the movement of reality. In this bias, history as a social production of human existence and as a research method is situated at the level of representation by thought, memory and by the writing of history in which the social subjects involved are produced and producers of social and historical reality (Malerba, 2006).

Thus, to write the history is to reconstruct the social phenomena from the traces accessible by the researcher, whose conclusions are always partial, because they depend on the sources used and the questions asked by the historian. For this reason, every history is a history of the present time, since the historian questions the sources influenced by the issues that afflict society of his time, to generate a “historical truth” that is always in process of affirmation and validation (Hobsbawm, 2003).

According to Fontes (2014, p. 189), “to consider truth as a process is to admit that we tend to it, but that it will never be finished. It also means admitting that the contradictory requires discussion and debate, not imposition”. Thus, as history unfolds, the questions asked to the sources are changed, new documents are discovered, and historical perspectives are transformed. For this operation, the researcher must look critically and questioningly at the sources - and with photography it would not be different.

In the case under discussion, we highlight photography as a historical source, but, in methodological terms highlighted here, its use has limits, as well as the “truth” that is revealed in it, because we consider that every trace needs to be compared to others, thus:

The notion of historical source should be problematized in the light of a criticism that considers it a support of social practices, overcoming the naive view that sources contain the past, and reveal themselves to the look of the present, for their pure existence. Every historical source is the result of a historical operation (Certeau, 1979). It does not speak for itself, it is necessary that questions are asked and that it is taken into consideration its nature as an artifact and object of material culture, associated with a social function and its trajectory through the ages. (Mauad, 2008, p. 21, free translation)

This reflection of the author leads us to think about the relationship between photography and truth. For a long time - and even today, in some cases -, photography has been seen as a proof of truth. However, this idea ends up reducing and limiting it. Starting with the idea that photography is a culturally/aesthetically/technically elaborated representation, Kossoy (1998) argues that the photographic image has multiple faces and realities: the first, more evident, inner, a reality of its own; the second, external, intentional.

Photography has its own reality that does not necessarily correspond to the reality that involved the subject, object of the record, in the context of past life. It is the reality of the document, of the representation: a second reality, constructed, codified, seductive, in no way naive, innocent, but which is, however, the material link of time and space represented, a decisive clue to unravel the past. (Kossoy, 2000, p. 22)

Similarly to Kossoy’s (2000) argument, Kosik (1976) argues that a phenomenon indicates essence, but also hides it. The essence is mediated to the phenomenon, not immediately given to understanding, and manifests itself in something different from what it is, despite being a component of reality next to appearance. It is constituted, still, of more complex processes, with diverse meanings, depending on the social beings and the dynamics of the phenomena involved. Thus, to know an object is to reveal its social structure. Ciavatta (2004) argues that it is essential

to go beyond appearances, capture the world of mediations, of social processes (technical, economic, political, environmental, scientific etc.), of the hidden essence of the phenomenon. They are articulated relations that are reconstructed at the level of historical knowledge, within a certain social totality that is part of the objective world. (Ciavatta, 2004, p. 46)

The author also indicates paths:

The historical perspective of mediations implies including as properties of the object the connections that determine it in situations of given time and space, the only way to find the explanation without falling into the abstract scheme of a mechanical relation. It is about not losing sight of the meaning that the object has not only as singularity, but also as particularity. Mediation is a necessary step to describe the particularity of the object, the relation of the apparent, singular or contingent, to the most comprehensive process that determines it. (Ciavatta, 2004, p. 46)

In this manner of thought, we can conceive photography as mediation, as an example of an object that shows and hides reality, in a double movement. As an object, the photograph is simultaneously image/document and image/monument. For Le Goff (1996), it is collective material production that carries intentional construction of a certain memory, which shelters certain values, ideas, traditions, behaviors, but not other values. It consists, therefore, of image/monument, of record produced as something to be perpetuated. As a photographic image, more than a frozen and spontaneous fragment of a past event, it results from the conscious intrusion of the photographer, who produced it. For Kossoy (1998), three are the essential elements for the realization of a photograph: the subject, the photographer and the technology. The first one is what deserves to be photographed. The second one has a direct influence on the result of the process, as it gives the perspective, the angle etc. The third one, in addition to giving clues about the historicity of the photographic object, also influences the result obtained.

Nowadays, we live a process of trivialization of photography, because we have, in our hands, smartphones capable of registering numerous “poses”, contrary to what was common at the time of the daguerreotypes, in which the photographed individuals had to stand still for a few minutes for the image to be captured. Machado (1998) raises some questions about the latest technologies, arguing that these changes have an impact on the traditional concept of photography, changing the act of photographing, as well as the consumption of photographs.

The author argues that photography is the recording of light on a chemically coated film, and that photochemical grains converted into units of mathematically controllable color and brightness are called pixels. Therefore, it faces technological changes, as pixelization, seeking to shed light on the processes of photo modification, such as editing. However, it is essential to remember that non-electronic techniques have been used to edit photos for a long time.

In addition to the reflection about the relationship between photography and truth, the discussion about photographic editing also brings about the relationship between photography and ideology. Until the trivialization - not in a negative sense - of cellphones with cameras, photography was an artifact belonging to the elite. That is, only the families whom (and how) it was interesting to photograph were photographed. Photographing was a choice. As it is also today, because we choose what, how and when the record is worth (even if there are many). The use of photography as a historical source is subject to countless conscious and targeted choices, both in the production, handling and/or preservation of documents that will serve, as stated by Le Goff (1996), as a monument, intentionally constituting a hegemonic memory. In contrast to the matter of memory evidenced by documents in the form of images preserved as monuments, there is the case in which memory is intentionally erased or forgotten, or even destroyed.

Benjamin (1987) and Ginzburg (1989), in the field of history, or even Santos (1988), in the field of sociology, defend the reconstruction of a history “of counterpoint”, which values counter-hegemonic narratives, or a kind of sociology of absences, which cognitively insert themselves in the countercurrent idea of producing a kind of epistemological inversion and taking the absent, or even the clue, in counterpoint to convergent and dominant data, which, mostly, confirms the version of the winners, in order to point out divergent data that highlights the version of the defeated, showing that another narrative based on another historiographical path is possible.

WOMEN’S INCLUSION IN INDUSTRIAL EDUCATION: CONTRIBUTION OF THE PHOTO INTERFACE AND OTHER TYPES OF SOURCES TO THE ANALYSIS OF WOMEN’S PRESENCE

To analyze the insertion of women in Brazilian society - and more specifically in industrial education -, we highlight historical elements from the period of 1950 to 1970, which, on the one hand, brought about the beginning of the overcoming of their exclusion in the access to education and work, but, on the other hand, highlight the contrary reactions in masculine spaces-times of industrial education, criticizing the official historiography, in addition to the use of photography as a historical source.

CO-EDUCATION IN BRAZIL: FROM LAW TO PRACTICE IN THE 20TH CENTURY

To address the theme of women’s insertion in industrial work and industrial education in the 20th century, due to our access to sources, we chose to signal the movement that goes from the elements of national reality to the aspects of local reality, outlining itself in IFES, whose origin dates back to the schools of artisan apprentices created in Brazil in 1909, and later, in early 1910, in Espírito Santo (Sousa, 2019).

According to data from Brazil (2009), such institutions, originated in the orphanages, had their public constituted of male children who were compulsorily picked up in urban spaces for the purpose of implementing an eugenic project under the pretext of educating for industrial work. They were teaching units that provided primary education content and design rudiments, and educated for artisanal work, but which were more similar to rehabilitation centers, where the target public would be the abandoned children to be attended by an educational project of a correctional and welfare nature.

According to Saffioti (2013), from the 1940s on, the educational legislation, despite rehearsing some progress in coeducation, whether in primary and/or secondary education, or even in industrial education (still extremely masculinized), in its internal contradictions and in its implementation, did not immediately change the picture of women’s exclusion from access to education. Decree-law 4.244 of 1942 (apudSaffioti, 2013), for example, discriminated against women and dealt a blow to the process of accepting the coeducation in progress by defining “women’s secondary education”. Although the decree-law did not institute segregated education for both genders, it suggested that women’s education should happen in special classes, that is, in women’s classes. Article 25, title III, states that “in secondary schools attended by men and women, the education of women will be taught, whenever possible, in exclusive women’s classes” - version present in Decree 8.347 of 1945 (apudSaffioti, 2013, p. 320).

The author’s data informs, still in 1955, that the exclusion of access to school education was more evident in the case of women. The Brazilian population at the time had a percentage of 51.65% of illiterate people, of which 23.44% were men and 28.21% were women; that is, for 8,570,524 illiterate men, there were 10,311,962 women in the same situation. In the same year, the number of enrollments in the two stages of secondary school (elementary and high school) was 311,996 for men and 261,768 for women, and 39,540 men and 35,832 women completed their courses in the previous school year (Saffioti, 2013). Data such as this indicates to us enormous difficulties not only regarding access to schooling, but also regarding the permanence and completion of school studies, which leads us to inquire about what additional barriers would be brought to women in their work of professionalization or schooling, with the goal of overcoming roles traditionally aimed at women.

According to Saffioti (2013), the transition from men’s schools to coeducational schools was not free of obstacles and shocks. It is worth remembering that the first buildings that housed artisans’ schools, created in each Brazilian capital in 1909, inherited orphanage structures that, like the Colégio das Fábricas (Factory College, 1809), Casas de Educandos Artífices (Artisans’ Students Schools, 1840) and Asilos dos Meninos Desvalidos (Orphans’ Asylums, 1854), were designed to serve as a boarding school for boys. To the extent that these spaces were disarticulating education and housing, hospitalization and professionalization, the coexistence between the genders was becoming more viable, although culturally uncommon.

In Brasil (2009), we noticed little female presence in photographs in industrial schools. At most, they appear in the photographs as assistants, cooks and teachers of educational units, or even spouses who accompany male teachers and managers in commemorative moments. Only in the 1950s, as we can see in Figure 1, the photos portrait women in the workshop spaces. In this first uncommon image, we can observe the presence of black women in industrial technical education at the Technical School of Salvador/Bahia. We consider that the black presence was very common in the federal system before the industrial schools assumed the status of Federal Technical Schools and started to offer the high quality vocational secondary education, a kind of passport for higher education, when it becomes the target of greed of the elites.

Source: Brasil (2009).

Figure 1 - Mechanical Workshop of Escola Técnica de Salvador (Technical School of Salvador), 1950s.

In Figure 1, we are able to see an instant register in which the photographer is located to the left of the students, who, wearing clean women’s clothing and careful hairdos, are located in front of a lathe and simulate performing machining activity. Analytically, we consider that, in the face of other sources of the centennial collection of the federal system dialoguing with intertextuality (Mauad, 2008), we can assume the relative actuality of the female presence in that space-time. This image should also be seen as mediation (Ciavatta, 2004) of a historical-social process that helps us inquire, and, if possible, understand, aspects of the process of insertion of poor black women in that professional education institution.

Images of female students in this system among those gathered by Brasil (2009) and Sousa (2019) will be much more evident from the 1970s when they appear in the spaces of laboratories and workshops. Although the laws already allowed their presence and the data informed corroborates enrollments and even graduations, the photographs of the institutions refer to a recent, quite masculinized past. In this case, in the trail of Benjamin (1987), we can say that they already presented themselves, but they were not systematically portrayed in industrial learning activity.

Looking at Figure 1, it is possible to notice students operating machines in the mechanical workshop. By the presence of the machines, we can identify that the physical space portrayed is a mechanical workshop, with students working in pairs on each machine. In the image, the students are wearing uniforms, dresses below the knees, with two rows of buttons, short-sleeved white shirts and dark ties. They look carefully at the heavy machines with which they interact.

The presence of women in these spaces was unusual. Portrayed in a rare way, in Figure 1, the presence of women, although authorized by legislation since the 1940s, was not fully guaranteed in 1950. According to the organic law of industrial education present in decree-law nº 4.073, of January 30, 1942, in article 5, “the right to enter industrial courses is equal for men and women. To women, however, it will not be allowed, in industrial education institutions, a work that, from the point of view of health, is not suitable for them” (Brasil, 1942).

Even before the transformation of technical schools into autarchies, their institutionalization into federal technical schools and the curricular organization of technical and industrial schools, educational practices made a distinction between men and women. For male students, it would be given pre-military education - article 26, paragraph 1 -, and, for female students, domestic education with “occupations that are proper to the household administration” - article 26, paragraph 2 (Brasil, 1942).

FROM THE SCHOOL OF ARTISTIC APPRENTICES TO THE FEDERAL CENTER OF TECHNOLOGICAL EDUCATION: NOTES ON PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION IN ESPÍRITO SANTO (1910-1990)

Among the roles and possibilities of the historian (Bloch, 2001), the reconstruction (or identification) of a space-temporal delimitation based on the use is highlighted, but especially on the interlocution of various types of sources. In the present case, we have structured an investigation on the phenomenon, in view of the search for traces of local history, methodologically guided by resources present in the micro history.

In our investigative section, besides the temporal definition, we elected as locus a federal institution of professional education, nowadays called Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Espírito Santo (IFES) (Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Espírito Santo). Based on documents detailing its trajectory, from its creation in 1910 until the 1970s, we sought the historicity of the phenomenon under study.

Initially called School of Artisan Apprentices of Espírito Santo, it was inaugurated on February 24, 1910 (located in downtown Vitória, at Presidente Pedreira street, nº 13)3 (Sueth et al., 2009). In this phase, it worked as a boarding school, following a pedagogical project of the primary-professional and correctional-welfare type, aiming at the public of children aged between 10 and 12. Later, on December 11, 1942, it became known as Escola Técnica de Vitória (Technical School of Vitória), transferred to the neighborhood of Jucutuquara (Vitória Avenue), with boarding and semi-boarding school regime, guided by a high school-professional educational project with a Taylorist-Fordist approach, intended for young people from 13 to 15 years old.

The good organization of the collection in the school records sector and in the memory center, an integral sector of the Nilo Peçanha library, which belongs to Campus Vitória, allows us to go through many aspects of the history of the institution in almost all the period from 1910 to 1998, when the institution became Centro Federal de Educação Técnica do Espírito Santo (Cefetes) (Federal Center for Technological Education of Espírito Santo). In this collection, even if there are gaps, the set of documents is rich and detailed. Among the primary sources, we highlight:

enrollment minutes from 1910 to 1934 (manuscripts);

evaluation minutes from 1911 to 1934 (manuscripts);

payroll from 1914 to 1917 (manuscripts);

student lists from 1910 to 1934 (manuscripts and typewritten);

invitations to course graduations from 1942 to 1970;

individual student cards from 1942 to 1994 (typewritten and on microfilm rolls);

sparse photographs from the period from 1910 to 1998;

school newspapers: O Eteviano, Gitec and ETFES, dating from 1949 to 1980.

Several historiographical works organized and analyzed these and other sources to tell and organize the documentary elements of the institution’s history, of which we highlight:

The Etevian Mistletoe - organized by Joaquim Bothéquia (1979);

100 years of the Young Titans - organized by Sueth et al. (2009);

a master’s thesis from the professional education course, The memory of professional and technological education at IFES: ways to access and disseminate documentary sources on campus Vitória, by Janda T. de Sousa (2009);

a doctoral thesis, Mathematical education and professional training: links of a history, by Antônio Henrique Pinto (2006);

a doctoral thesis, Interdictions and resistances: the difficult paths of women’s schooling in the EPT, by Maria José Resende Ferreira (2017).

THE BEGINNING OF THE SCHOOL OF ARTISAN APPRENTICES IN ESPÍRITO SANTO (1910-1940)

To prove the phenomenon under study, we took student’s admission notices and lists of students enrolled in the collection of memory of the institution referring to the period from 1910 to the 1930s. According to Sueth et al. (2009), one month before the inauguration of the school, in January 1910, the building that would be the first headquarters of the School of Artisan Apprentices of Espírito Santo (EAAES) was donated by the governor of the state, Jerônimo de Souza Monteiro, who appointed its first administrator, José Francisco Monjardim. Immediately, according to Sueth et al. (2009), the first call for enrollment to the educational institution was published on page 42 of the Diário da Manhã newspaper, on January 27, 1910:

Since February 15, the enrollment for primary and design evening courses, and also for learning in Woodworking, Carpentry, Tailoring, Blacksmith and Foundry and Electricity is open. These courses are free and funded by the federal government (Ministry of Agriculture, Trade and Industry). According to [...] Decree n° 7.763 of December 23 of last year, underage students will be admitted, as long as their parents and guardians request it within the deadline [...] for registration and they meet the following requirements, preferred the disadvantaged of fortune: guardians of 10-year-olds; maximum age of 13 years old; not suffering from any infectious disease; having no physical disability that makes them unable to learn the trade. Each student will only be given the learning of a single trade, consulted the respective aptitude and inclination. (Diário da Manhã, 1910, apudSueth et al., 2009)

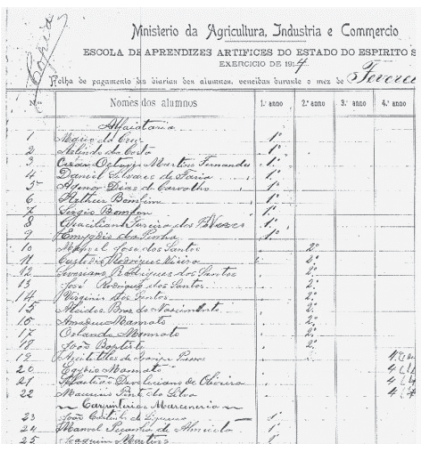

The document shows that the search for enrollment was not intense, given the reiteration of the announcement calling possible students, but low-income, likely low-schooling families, would not have access to newspapers, and this notice would have been restricted. From the point of view of the issue of the presence of women, the exclusion of girls is not explicit in the text, as is clear the exclusion of people with disabilities, but the use of “each student”, “blacksmith” and “disadvantaged ones”, not flexed in the feminine, if, on the one hand, does not exclude girls, it also does not show that they would be part of the intended public. To advance the search for the eventual presence of women, we searched in manuscript documents (minutes of the EAAES and list of payments of the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade) for any hint about the gender of the students. Looking at Figure 2, we are able to see an excerpt of a page with data on students’ remuneration in February 1914, which are listed in a list of names of students enrolled in the 1st, 2nd and 4th grades of the Tailoring course. This excerpt may indicate that the low demand forced the federal government to pay those who attended school.

Source: Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, Memory Room Collection, Campus Vitória.

Figure 2 - Payroll of the students at the Tailoring course of the School of Artisan Apprentices of Espírito Santo (EAAES) - Feb 1914.

However, based on the survey of sources present in the collection, we observe a more complete list, organized in alphabetical order, with the first 80 students enrolled in the daytime and evening courses at EAAES in the period from 1910 to 1911.

Abel de Almeida/ Admião Macedo/ Agenor José dos Santos/ Alberico Bittencourt/ Alberto de Freitas Guimarães/ Alício Francisco Alves/ Álvaro Gonçalves Ferreira/ Amâncio Paiva/ Antenor Rezende/ Antônio Ávila Junior/ Antônio da Rocha Tagamo/ Antônio dos Anjos/ Argeu Pereira/ Aristóteles Passos/ Ascendino Ferreira Lemos/ Ascendino Leal/ Basílio Ferreira dos Passos/ Benedicto Bahia/ Benedicto Olívio/ Benício Pereira/ Bernardo Clemente Gonçalves/ Bráulio Santa Clara/ Dario de Almeida Vidigal/ Dario Vidigal/ Demétrio Evangelista de Andrade/ Egydio Mannato/ Eugênio Bizzi/ Eugênio Campos Telles/ Eustoigenes Calmon Costa/ Evaristo Martins/ Fernandino Martins da Victória/ Firmino Rangel Álvaro Gonçalves/ Francisco Pedro Neves Xavier/ Heynozolino de Alcântara Soares/ Jaime Ribeiro da Silva/ Jancintho Landim de Menezes/ Jerônimo Gonçalves Felix/ João Bahia/ João Baptista do Nascimento/ João Justiniano da Fraga Santos/ João Justiniano Pinto da Fraga/ João Manhães/ João Pereira Porto/ João Ribeiro da Silva/ João Ribeiro da Victória/ Joaquim Pereira da Silva/ José Carlos da Andrade/ José da Rosa Ribeiro/ José Romancinno do Nascimento/ Lazaro Borges/ Leocádio dos Passos Salles/ Leocondino Cruz/ Lúcio de Oliveira/ Luis Moreira de Carvalho/ Luis Paiva/ Luis Passos/ Lydio Martins Flores/ Manoel Genésio/ Manoel José dos Santos/ Manoel Moraes da Victória/ Manuel dos Passos/ Maurício Pinto da Silva/ Miguel do Nascimento/ Olindo Cassilhos/ Olintho Faria dos Santos/ Olívio Camponez/ Onelatino Borges Caldeira/ Oscar Aniceto do Prado/ Osvaldo dos Santos/ Palmerino Motta/ Paulino dos Santos/ Pedro Patrocínio/ Plínio Miguel do Nascimento/ Sebastião Deocleciano de Oliveira/ Silvio Barreto Bacio/ Themis Landim de Menezes/ Umberto Mannato/ Urbano Salgueiro Filho/ Vasco da Silveira/ Vicente Balbi/ Virgínio dos Santos. (Lima, 2010, p. 6)

Without the image of the group, and analyzing only the list, we tried, through the characteristics of the names, to eventually associate them or not to the female gender. Looking at the list, only a few clues are signalized. Only one name could be feminine, which is the name “Themis”. This data, however, does not assure any certainty, but, methodologically, as Ginzburg (1989) teaches, it could be an important vestige.

Nevertheless, in order to advance the identification of the advent of women’s presence in the institution from the beginning of the XX century, a phase in which few spaces were destined for the education and/or schooling of women, we analyzed written, but also imagetic sources, in order to highlight the presence of women in these spaces of education. Throughout the study, we cross-checked this information with other ones, available in IFES’ collection.

The initial attempt was to observe this issue through the images, because the presence of women in the photographs would give us evidences to reveal the phenomenon under discussion; however, in light of Kossoy (2000), Ciavatta (2004) and Mauad (2008), we return to the basis that photographs do not portray the historical facts in an absolute way, as they can also be the object of manipulation, both in their production and in their preservation.

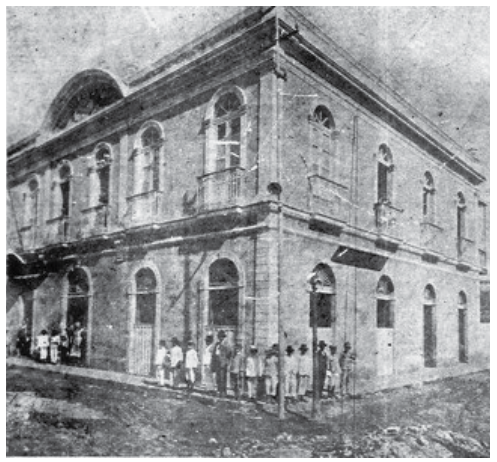

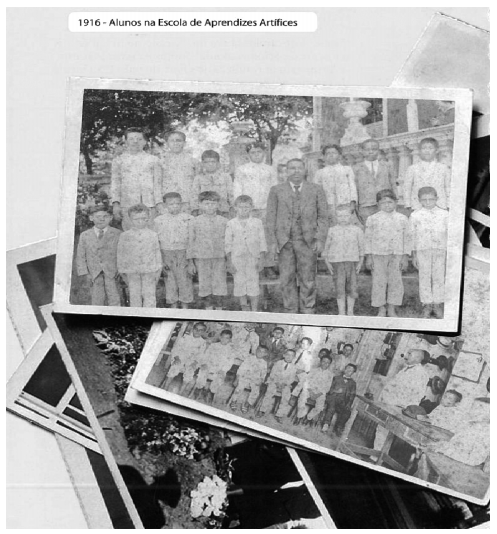

However, in cross-checking with other types of sources, the use of images as a historical source can provide more eloquent evidence of women’s presence in the institution, as well as allow the historiographical debate on the validity, importance and nature of the plurality of sources of historical research. For this, initially, we brought images of the alleged students profiled (Figures 3 and 4), which allowed us to notice and/or evaluate the presence, absence and/or erasure or exclusion of women in the EAAES.

Source: Brasil (2009).

Figure 3 - School of Artisan Apprentices in Espírito Santo. 1910-1917. Inaugurated on 02/24/1910 - Presidente Pedreira street, nº 13 - downtown Vitória.

Source: Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, Memory Room Collection, Vitória campus and Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo’s diary (2009).

Figure 4 - EAAES Classes of 1916 - downtown Vitória.

Far from trying to obtain or produce a definitive or unquestionable historiography, photographs, as well as documents in general, need to be read carefully, taken as monuments intended to produce a memory that often combines with the erasure of other sources. We know that societies and institutions produce and/or preserve documents with many intentions, including that of generating an ideologically determined historical narrative (Le Goff, 1996; Pinsky and Luca, 2009). In other words, in the process of producing and preserving images, some are erased and other information is reiterated for specific reasons and intentions. Thus, even photographs are far from being free of ideologies and their political and institutional use. Often, the images show, but also hide. We can notice, in Figures 3 and 4, photographs taken probably between 1910 and 1916 (commemorative document at the time of the centenary of the federal system of Cefetes, 2009), that the apprentices are posed.

From the analysis performed, we believe that there was a construction of scene, since the underage students (children and teenagers) profiled were possibly dressed and organized to be photographed while posing. Therefore, these images, in which there is a total absence of female individuals (such as female teachers or students), are not spontaneous. Assuming the indiciary bias of Ginzburg (1989), we problematize the scene; we do not know if girls had been removed from the scene, or if, in fact, they were not part of the student body or faculty.

To try to clarify this issue, we will cross-examine the photographs with each other (as states Mauad, 2008) and with other types of documents (as state Pinsky and Luca, 2009). That is, in the interlocution between the written sources in their relation to what they reveal to us (or what they hide, as Benjamin, 1987 states), the images, when intercrossed, help us understand in the set of sources. Thus, starting from the lists available in the collection, we attempted to define a historiographical position in the composition of the gender of the student body on the space-time under discussion. Initially, in view of the analysis of the national context of the legislation and the sources available in the local space, in the chronology of the years 1910 to 1930, we can conclude that, probably, there were no women in the institution.

TECHNICAL SCHOOL OF VITÓRIA (1940-1965): THE WOMEN’S PRESENCE THAT HAD BEEN FORGOTTEN BY OFFICIAL MEMORY

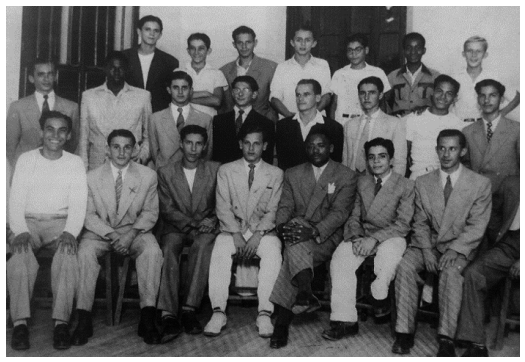

Continuing with the analysis in the decade of 1940, year in which the institution, installed in a new building, became Escola Técnica de Vitória (Technical School of Vitória), we noticed changes in the types of courses offered, as well as in the ages of the students. Neww courses included Basic Industrial Processes (Typography and Binding, Leather Arts, Woodworking, Tailoring, Mechanics of Machinery, Painting and Metalwork). According to Sueth et al. (2009), the group in Figure 5 constituted the first class formed, in 1946, in the ETV’s new headquarters in Jucutuquara, inaugurated in 1942. According to the authors, in this image, students Loadir Carlos Pasolini and Admercil Silva, who would become school employees, are present. Also featured is Jair Marino, author of the institution’s anthem.

Source: Sueth et al. (2009).

Figure 5 - First graduated class at Escola Técnica de Vitória (ETV) (Technical School of Vitória), in 1946 - new headquarters in Jucutuquara.

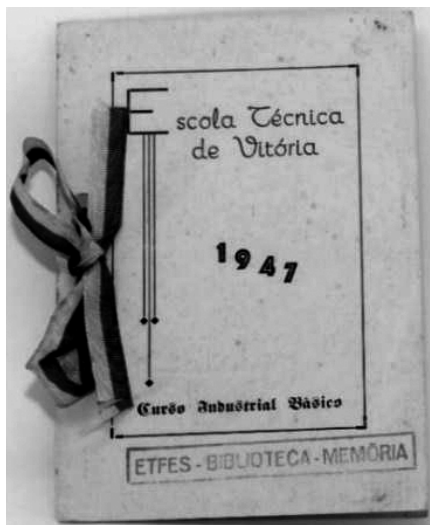

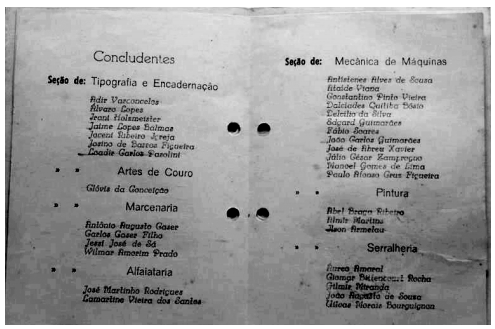

Considering different sources throughout the study, we came across the graduation invitations available in the memory room (Figures 6 and 7), IFES collection, campus Vitória. In them, it was possible to see evidence of the presence of women in the institution, although, because they are graduation invitations, they report only graduated students. According to the documents, in 1947, students whose first names were Adir, Álvaro, Irani, Jaime, Joceni, Josino and Loadir4 graduated in Typography and Binding; Clovis in Leather Arts; Antonio, Carlos, Jessi and Wilmar in Woodworking; Joseph and Lamartine in Tailoring; Antístenes, Ataíde, Constanino, Dalcíades, Delcilio, Edgard, Fabio, João, José, Julio, Manoel and Paulo in Mechanical Machines; Abel, Almir and Ilson in Painting; and Aureus, Giomar, Gilmir, João and Uilcas in Woodworking. Out of these names, Adir, Irani, Joceni, Loadir, Jessi, Dalcíades, Giomar and Uilcas are names that could be feminine, which does not make it clear whether there were women in these courses or not.

Source: Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, Memory Room Collection, Campus Vitória.

Figure 6 - Cover of invitation for the graduation of Escola Técnica de Vitória’s Basic Industrial course in 1947.

Source: Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, Memory Room Collection, Campus Vitória.

Figure 7 - Page 4 of Escola Técnica de Vitória’s Basic Industrial Course - 1947.

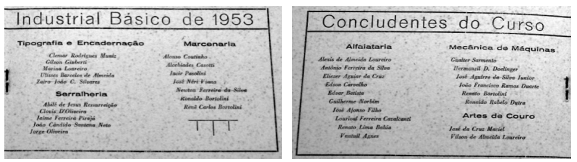

However, in the 1953 invitation with the list of ETV course graduates (Figure 8), the female participation becomes more explicit. Out of the 25 graduates, among several male names, there are characteristically feminine names, such as Clemar, Jacir, and, above all, Marina, indicative of women’s presence. On the trail of Ginzburg (1989) and Le Goff (1996), we need to relativize this source, because it is the record of course graduates. That is, it is possible that certain male or female enrolled students have taken the course, and, eventually, not completed it. Thus, people who were excluded before the completion of the course may have had access to these classes.

Source: Instituto Federal de Vitória, Memory Room Collection, Campus Vitória.

Figure 8 - (A and B) Invitation pages of graduate students - Escola Técnica de Vitória’s Basic Industrial Course - 1953.

Based on the documentation available in the collection, a list of students who took, between 1950 and 1964, the basic industrial course in the Technical School of Vitória for the occupations of Typography, Binding and Tailoring, is seen in Chart 1. We can observe that not all women completed their courses in three years. Some of them left in the same year they began the course, or within one, two or three years, while others stayed four years to complete their education.

Chart 1 - First students enrolled in the courses of the Technical School of Vitória, 1950-1960.

| Name | Course | Ingress | Egress |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marina Loureiro | Typography and Binding | 1950 | 1953 |

| Gilda Toscano Brito | Typography and Binding | 1950 | 1954 |

| Zilda Trindade | Typography and Binding | 1950 | 1951 |

| Dalva Silveira Pinto | Typography and Binding | 1950 | 1951 |

| Dulce Ferro | Typography and Binding | 1950 | 1950 |

| Anizia Luiza Espírito Santo | Typography and Binding | 1950 | 1952 |

| Janedir Glória Nascimento | Typography and Binding | 1950 | 1954 |

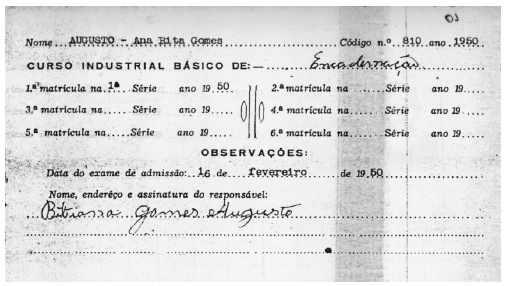

| Ana Rita Gomes Augusto | Typography and Binding | 1950 | 1950 |

| Maria Imaculada Soares | Typography and Binding | 1951 | 1951 |

| Jaila Borges | Tailoring | 1951 | 1952 |

| Maria da Glória Marculano | Typography and Binding | 1952 | 1955 |

| Nair Varejão Pádua | Tailoring | 1952 | 1952 |

| Vanda Maria Lucas | Tailoring | 1952 | 1953 |

| Telma Alves Paiva | Typography and Binding | 1957 | 1960 |

Source: Produced by the authors from the collection with the enrolled lists, graduation invitations and student cards linked to the period from 1950 to 1960.

As stated by Sousa (2019), the legislation from 1940 on allowed women to attend industrial school. However, despite the possibility of enrollment, in elementary school in Brazil, as described by Souza (2008), few of them were able to complete secondary education, in general, and industrial education, in particular.

According to information from documents detailing students who failed, as well as from the institution’s selection notices present in the collection, many were the mechanisms of exclusion and selectivity. In addition to the admission exam and the directioning of the schools that defined which courses women should and could take, in some cases, the exclusion of students (but especially female students) justified the withdrawal of the student by failure or maladjustment to perform the job.

For this, the expression that the student “did not reveal inclinations to the occupation” was registered in the individual student’s card, and then included in the “bulletin of merit”.

The documentation indicates the presence of women in the 1950s, highlighting their link to Typography and Binding courses, as it is a less manual and lighter activity. According to Pinto (2006), this public was more tied to the Tailoring courses, which would be similar to the Modeling and Sewing course, officially aimed at women and still offered in some technical schools in other states.

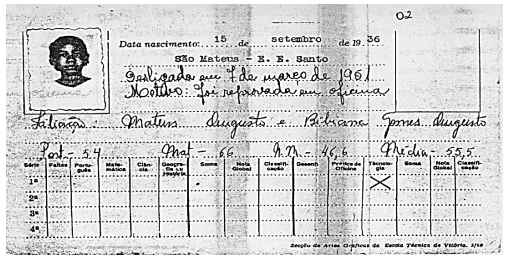

In times when black, and probably poor, women were studying at the Technical School of Vitória, taking courses generally in Tailoring, Typography and Binding, the documentation observable in Figures 9 and 10 reveals that the failure in the sequence in one of the grades meant the exclusion, which was the case of the student Ana Rita Gomes Augusto.

Source: Collection of individual records from the school records room of Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, Campus Vitória.

Figure 9 - Page 2 of the individual registration form of the student Ana Rita Gomes Augusto, 1950.

Source: Collection of individual records from the school records room of Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo - Campus Vitória.

Figure 10 - Page 1 of the registration of the student Ana Rita Gomes Augusto, from 1950.

Although few photographs show images of women among the students of this institution, the female presence was real, although often unfeasible or little tolerated. A student, seen in Figures 9 and 10, daughter of Mateus Augusto and Bastiana Gomes Augusto, born on September 15, 1936, at the age of 14, took an admission test on February 16, 1950, getting a score 54 in Portuguese and 66 in Mathematics; however, she failed the workshop, which resulted in her egress on March 7, 19515.

Here, the institution seems to give students responsibility for their own learning. It is worth knowing whether such procedure affected all students in the same way, or whether women were preferred or not in disapproval and exclusion. Apparently, the meritocratic and selective tradition of the institution that excluded students who did not reach the approval in any of the stages-grades-years of the courses, which prevented the permanence of the aforementioned student, has come a long way. In the trace of the problematization of historical sources, it is worth asking if this procedure was more forceful in the case of women, or if the exclusion occurred systematically with men as well, and whether there was a higher or lower incidence depending on race and social conditions.

ESCOLA TÉCNICA FEDERAL DO ESPÍRITO SANTO (FEDERAL TECHNICAL SCHOOL OF ESPÍRITO SANTO) (1965-1990): QUESTIONING THE OFFICIAL MEMORY ABOUT THE PRESENCE OF WOMEN IN THE INSTITUTION

After the period from 1909 to 1942, industrial education, despite its association with the federal government, did not have a good physical and pedagogical structure. But this type of institution became elitized, and, over time, a model of teaching quality, especially in the 1960s, when they became federal technical schools and an intense demand of local elites who aimed at higher education was highlighted. Admission exams resulted, not occasionally, in classes of students composed mostly of larger contingents of white males from wealthy classes.

After being transformed into autarchies by the Kubitschek government in the 1950s, the technical schools became, in the turn from the 1960s to the 1970s, federal technical schools in the military government that, in the middle of the “Brazilian miracle”, would improve their infrastructure even more and progressively extinguish the technical-high school courses (basic industrial, industrial learning and industrial high school), fully homogenizing the school offer in technical courses of 2nd degree, tendentially directed to an increasingly white and middle-class or upper-class public. Thus, following the logic of human capital theory and in order to reproduce the workforce in quantity and quality required by capital, military governments had to provide a type of public school of professional education in a differentiated way. It was thus obliged to finance and ensure the reproduction of complex work for greater production of relative surplus value for the industrial projects in progress.

From the late 1950s to the early 1970s, there was an intense phase of transformations in the institution. In 1959, by law 3.552, technical schools were elevated to the status of autarchy (Sueth et al., 2009, p. 75). In 1961, the industrial course is extinguished and the technical course in Roads begins. In 1965, ETV was renamed ETFES by Law 4.759 (Ministry of Education’s ordinance of September 3, 1965, apudSueth et al., 2009, p. 77). Industrial learning classes were closed in 1968 and industrial high school in 1973.

Due to the quality, the ETFES, formerly called the Technical School of Vitória, with its boarding school and military school regime, still seen as a school for the poor ones, started to be sought out by people of all ethnicities, classes and gender in the admission exams. In this context, after a decade of being systematically excluded, white, middle-class girls, who were high school graduates in the 1960s or in the 1970s, sought the institution when coming to high school, in order to obtain professional education in technical courses allowed to them. Sueth et al. (2009) reiterates the presence of women only from the 1970s and only in technical courses. This important work, commemorating the 100 years of the institution, alluding to a situation of raising the flag, states that, in 1972,

for the first time a female teacher was chosen and not a male teacher, to salute the flag [...]. Teacher Maria Helena Teixeira de Siqueira. Interestingly, this was also the year in which conditions were created for the admission of women in technical courses, with bathrooms and changing rooms for students created. [...] It was also this year that the records marked the first female names in the list of graduates of technical courses: Lucineia Gonçalves da Silva and Arlete de Vargas Guimarães (Buildings). (Sueth et al., 2009, p. 111)

Observing the student’s documentation in Figures 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, we notice that the student was regularly enrolled, and that, in the request (Figure 11), forwarded to the school board, which refers to the student as a pioneer. The work of Ferreira (2017) reiterates the inaugural presence of women from 1971, when the opening of enrollment for women would have been regulated. The author, who researched management documents of the time, states that, according to the minutes of the board of teachers, “Mr. President informs that in the next year the choice for the females students will be free” (Ferreira, 2017, p. 95).

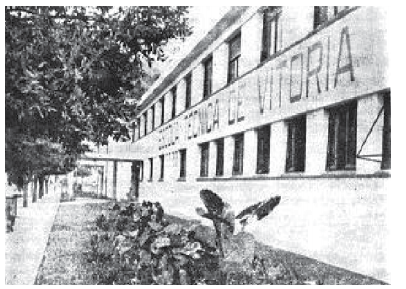

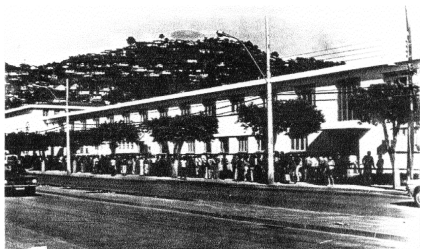

Source: O Eteviano newspaper, from Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, memory room collection, Campus Vitória.

Figure 11 - Escola Técnica de Vitória (ETV) inaugurated in 11/12/1942 - Jucutuquara (today, Campus Vitória, part of Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo).

Source: O Gitec newspaper, from Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, memory room collection, Campus Vitória. Photo collection from Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, Campus Vitória.

Figure 12 - Escola Técnica Federal do Espírito Santo (ETFES), 1980s - Jucutuquara - line up in front of the technical school on admission day.

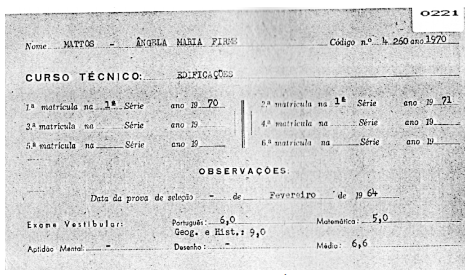

Source: Collection of individual records from the school records room of Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, Campus Vitória.

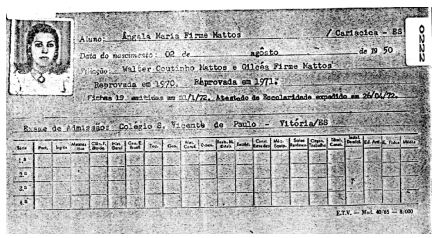

Figure 13 - Page 2 of the individual registration form of the student Ângela Maria Firme Mattos, 1971.

Source: Collection of individual records from the school records room of Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, Campus Vitória.

Figure 14 - Page 1 of the individual registration form of the student Ângela Maria Firme Mattos, 1971.

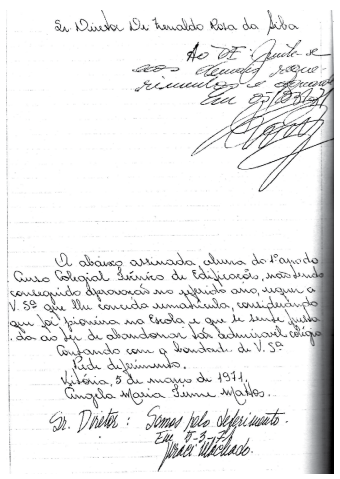

Source: Collection of individual records from the school records room of Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, Campus Vitória.

Figure 15 - Application - March 5, 1971 - by Ângela Maria Firme Mattos to the school’s principal, approved by the education board.

In an authorizing tone and unwillingly, the chairman of the council of representatives6 seems to admit this obligation, literally stating that they could not “change a constitutional device” (Ferreira, 2017, p. 95). The image of a school organization based on civic and military values was very much associated with the universe of industrial education, and, in the various photographic records of the student body in line, the male figure stands out. These fundaments were also present in the pedagogical project, associated with effort and performance, which can be observed in the school anthem, the “ETFES March”, authored by Jair Marino (graduated in the first class of 1946), with melody by teacher Maria Penedo (ETFES, 1979 apudBothéquia, 1979):

In the incessant march of progress,

Hearts vibrating with ardor,

We walk together with success,

Treading the path of labor.

We graduated with struggle and sacrifice,

From this land, the industrial vanguard.

We’re all brothers in the trade,

Yearning for an unparalleled Brazil.

Great forge of manly men,

True printer of sound ideas,

Immense barn of feverish souls, save school of young titans;

The sweet harmony in our toil.

It gains strength in the light of knowledge.

It forms the ideal, the essence of life,

Endowing man with energy and power.

Let us continue our journey;

For this fertile field of study.

Fighting and serving the beloved homeland,

Our courage will be its shield.

And we will raise the nation,

Hymns singing, full of vigor,

Renovating in its construction.

The sources of civility and value.

The strength that our voice contains;

It is the boldness of our green sea...

It’s the glow, the beauty of this land...

It is the voice of a Brazil in progress.

Here, it remains evident how the spread of the ethos of labor was tied to male virility. It is worth asking how these values entered the school organization and to what extent they collided with female presence from the 1970s onwards7. But, recapturing the debate on the beginning of female inclusion in the institution, despite the documents already presented, and having been a Metalwork student, the engineer and former school’s principal (1970-1994) Zenaldo Rosa da Silva (died on June, 6, 2020) states that women only ingressed in ETFES in 1969. In his report, the fact would have occurred, only and solely, because he, as director, in an unprecedented way, would have supported and authorized the enrollment of a student named Ângela de Matos in the Buildings course, thus inaugurating the insertion of women in the institution (apudLima, 2010). It remains unknown whether Zenaldo sought to hide the previous inclusion of women in the institution, or whether he tried to capitalize on the ineditism of this insertion for his administration.

Partially confirming this information, we have the school record of Ângela Maria Firme de Mattos, daughter of Walter Coutinho Mattos and Gilcéa Firme Mattos, born on August 2, 1950, enrolled in 1970 in the Buildings course. Despite the grades 60 in Portuguese, 50 in Mathematics and 90 in Geography/History, the referred student failed the first grade in 1970, as shown in Figures 13, 14 and 15 8.

In Figure 15, it is observed that, having failed on May 5, 1971, the student filled a request to the school’s principal Zenaldo Rosa da Silva to remain in the course in 1971. In the document, it is explicit that the aforementioned student belonged to the first year of the technical education in Buildings, and “not having obtained approval in the referred year, she required that the registration was granted to her”.

Contrasting, however, this information with Lima (2010), we found Figure 16, an from 1966 in which women were already present. It consists of at least three students, lined up and posing, at the time of the raising of the flag. This document differs from the previous information, as the data of the photo is in contrast to previous sources. Thus, if the Roads course was created in 1961 (see the Gitec newspaper), we understand that both sources need to be compared to other sources in order to know why the student Ângela de Mattos is considered the pioneer. Methodologically, working with the intercrossing of sources, in the trail of Ginzburg (1989) and Pinsky and Luca (2009), if the photographs are not sufficient, they cannot be ignored. The image, present in the collection and in the commemorative agenda of Cefetes at the time of the centenary, brings the ETV flag, as well as the presence of women - it is clear that it is the year 1966. Therefore, the offer of technical education with second degree, defined by law 5.692/71, must have favored the inclusion of women in ETFES, but it was not then that the inclusion of women in industrial education was given in the case under study.

Source: Sueth et al. (2009).

Figure 16 - Flag raising at Escola Técnica de Vitória, located in the neighborhood of Jucutuquara, in 1966.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we analyzed the insertion of women in Brazilian society from their insertion in education, based on empirical elements of women’s access to industrial education in courses offered in federal schools, problematizing its occurrence in the period from 1950 to 1970. To hold the debate on women’s inclusion in industrial education in the history of Brazil, we mobilized historical and historiographical elements of the trajectory of the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Espírito Santo (IFES), which, in the 1970s, when the institution was called Federal Technical School of Espírito Santo, had the most expressive presence of women among their students.

In order to question the official periodization according to which women had been inserted only from the 1970s on in the so-called ETFES, due to the creation of high school technical courses, we covered the historical sources available in the collections of the institution. In this movement, we highlighted, on the one hand, the complementarity of the types of historical sources, and, on the other hand, we problematized the limits of the validity of photography as a historical source.

The use of photography as a historical source is subject to numerous conscious and targeted choices in production, handling and/or preservation of documents that will serve as monuments to produce or erase a set of sources constitutive of a certain memory.

Based on the above, we believe that the erasure and denial of the insertion of women before the 1970s can only be unveiled in the comparison of sources and in the problematization of the use of photography as a historical source. The analysis of the sources revealed that other female students studied at school still in the 1950s, but that they would have been so systematically failed and excluded that, at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s, the insertion of female students was credited as an unprecedented and benevolent action of the on-call directors.

In any case, the hegemonic image of ETFES remains a masculine, sexist and militarized image of correctional and meritocratic values. Organized with rigor, the school curriculum and the spaces-times of the institution do not show the many contradictions that constitute its trajectory. The institution, in its anthem and in its masculinized and taylorized image, does not assume the systematic exclusion of women in the 1950s. Nowadays, the policies of social and racial quotas, as well as the qualification courses for youth and adults, cause discomfort by inserting individuals alien to the institution, which should be fully public and not only offer quality.

Thus, based on the cross-checking of documentary sources, in which photographs and other records are included, we highlight the limits of the choice of specific isolated sources and point out the contradictions of the version assumed by the “official” historiography, according to which women’s inclusion in the old ETV would have started only in the 1970s, when the technical courses were created. The interlocution of neglected, but still existing documents in the hegemonic version, however, confirms the presence of women in industrial education in ETV in the 1950s. But this public was probably excluded by mechanisms of meritocracy and selectivity, in which the responsibility for their own learning was attributed to the students, especially the female ones. Such a process was so effective that, by the 1960s, there were no women left in the ETV benches. Thus, in ETFES, women were reinserted as if they had never entered there, which is why it was an “official memory” that the female presence would have started only with the advent of the denomination of ETFES, with the offer of technical courses, which only the systematic search and interlocution of sources can overcome. It is worth asking: how did this process occur in other centenary units of the federal system that today comprise units of the federal institutes?

REFERENCES

BENJAMIN, W. Magia e técnica, arte e política. 7. ed. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1987. [ Links ]

BLOCH, M. Apologia da história ou o ofício do historiador. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 2001. [ Links ]

BOTHÉQUIA, R. et al. O visgo eteviano. Vitória: ETFES, 1979. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto nº 7.247, de 19 de abril de 1879. Brasil, 1879. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://ead2.iff.edu.br/mod/url/view.php?id=106376 . Acesso em: 4 jul. 2019. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto-lei nº 4.073, de 30 de janeiro de 1942. Diário Oficial da União, 30 jan. 1942. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 378, de 13 de janeiro de 1937. Dá nova organização ao Ministério da educação e Saúde Pública. Diário Oficial da União, Seção 1, 15 jan. 1937. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 5.692, de 11 de agosto de 1971. Fixa Diretrizes e Bases para o ensino de 1° e 2º graus, e dá outras providências. Brasília, 1971. [ Links ]

BRASIL. 100 anos da rede federal. Brasília, MEC, 2009. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://centenariorede.mec.gov.br/index.php/fotos . acesso em: maio 2019. [ Links ]

CIAVATTA, M. Mediações históricas de relação trabalho e educação: gênese da disputa na formação dos trabalhadores (1930-1960). Rio de Janeiro: Lamparina/CNPq/Faperj, 2004. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, M. J. R. Interdições e resistências: os difíceis percursos da escolarização das mulheres na EPT. 285f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, 2017. [ Links ]

FONTES, V. História e verdade. In: FRIGOTTO, G.; CIAVATTA, M. (org.). Teoria e educação no labirinto do capital. 2. ed. São Paulo: Expressão Popular, 2014. p. 167-189. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, C. Mitos, emblemas, sinais: morfologia e história. Tradução: Federico Carotti. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1989. [ Links ]

HOBSBAWM, E. O presente como história. In: HOBSBAWM, E. Sobre história. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras , 2003. p. 315-331. [ Links ]

KOSIK, K. Dialética do concreto. 2. ed. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1976. [ Links ]

KOSSOY, B. Fotografia e história. São Paulo: Ática, 1998. [ Links ]

KOSSOY, B. Realidades e ficções na trama fotográfica. 2. ed. São Paulo: Ateliê, 2000. [ Links ]

LE GOFF, J. História e memória. São Paulo: Editora da Unicamp, 1996. [ Links ]

LIMA, M. Desenvolvimento histórico do tempo socialmente necessário para a formação professional. Vitória, 2010. [ Links ]

MACHADO, A. A fotografia sob o impacto da eletrônica. In: SAMAIN, E. (org.). O fotográfico. São Paulo: Hucitec, 1998. p. 317-325. [ Links ]

MALERBA, J. Teoria e história da historiografia. In: MALERBA, J. Teoria e história da historiografia. São Paulo: Contexto, 2006. p. 11-26. [ Links ]

MAUAD, A. M. Poses e flagrantes: ensaios sobre história e fotografia. Niterói: EDUFF, 2008. [ Links ]

PINTO, A. H. Educação matemática e formação para o trabalho: práticas escolares na Escola Técnica de Vitória - 1960 a 1990. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, 2006. [ Links ]

PINSKY, C. B.; LUCA, T. R. (org.). O historiador e suas fontes. São Paulo: Contexto , 2009. [ Links ]

SAFFIOTI, H. A mulher na sociedade de classes: mito e realidade. São Paulo: Expressão Popular , 2013. [ Links ]

SANTOS, B. S. Um discurso sobre as ciências na transição para uma ciência pós-moderna. Estudos Avançados, São Paulo, v. 2, n. 2, maio/ago. 1988. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40141988000200007 [ Links ]

SOUSA, J. T. de. A memória da educação profissional e tecnológica no IFES: caminhos para acesso e difusão das fontes documentais no campus Vitória. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação Profissional e Tecnológica) - Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação Profissional e Tecnológica, Instituto Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, 2019. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://biblioteca.ifes.edu.br:8080/pergamumweb/vinculos/000018/00001819.pdf . Acesso em: dez. 2019. [ Links ]

SOUZA, R. M. F. História da organização do trabalho escolar e do currículo no século XX (ensino primário e secundário no Brasil). São Paulo: Cortez, 2008. [ Links ]

SUETH, X. et al. 100 anos dos jovens titãs. Vitória: Edifes, 2009. [ Links ]

TOMAZ, L.C.L.; PORTO, P. O Supremo Tribunal Federal e a permissão para publicações de biografias não autorizadas: uma análise da ADIN 4815. Jus, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://jus.com.br/artigos/62181/o-supremo-tribunal-federal-e-a-permissao-para-publicacoes-de-biografias-nao-autorizadas-uma-analise-da-adin-4815 . Acesso em: dez. 2019. [ Links ]

1 With the educational reform in the municipality of the Court of Leôncio de Carvalho, instituted by decree nº 7.247, from April 19, 1879, coeducation was admitted (Moacyr, 1936 apudSaffioti, 2013). According to the law’s paragraph 3 of article 4, “in existing primary schools the ones that will be created, for the female gender, students will be received until the age of 10” (Brasil, 1879).

2 Saffioti (2003) cites Rui Barbosa, who expressed himself negatively on coeducation, attributing to it the function of resource saving only.

3 Under Law n° 378/37, the School of Artisan Apprentices of Espírito Santo was renamed Liceu Industrial da Vitória (Industrial Lyceum of Vitória), a denomination that lasted only 7 years. In 1942, it became the Technical School of Vitória, even if it did not offer technical courses.

4 The name Loadir Carlos Pasolini, who will later become an employee of the institution, appears in the photograph, but also appears in the invitation of 1947. This name, however, is scratched in pencil in the invitation, leaving room for doubt about his presence at the graduation of 1946 or 1947. This case is interesting to show how two different sources can give different, and sometimes divergent, details, demanding a further historical development.

5 Due to the time since that these facts occurred, it was not possible to obtain authorization from the student to inform this data. However, we believe that this information does not demean the student; on the contrary, it refers to the pioneering role of the student in the institution. We are supported here by legislation deriving from Ação Direta de Inconstitucionalidade (ADI) 4.815 (apudTomaz and Porto, 2015), which authorizes the production of biographies.

6 “It is worth remembering that this board was a democratic decision-making body that ran the school and was responsible for choosing the school’s principal. So much so that, in 1974 during the civil-military dictatorship, it was extinguished by Decree nº 75.079” (Sueth et al., 2009, p. 89).

7 Even having extinguished the boarding school at the time of the reintegration of women, ETFES had many similarities with the military institutions. According to Sueth et al. (2009, p. 111), “the rigidity of the discipline was so great that women, until 1980, could only put black ornaments on their hair”. This male trait of the institution was preserved in 1988, with the percentage of 72.96% of enrollments for male students.

8 Considering the period in which these facts occurred, it was not possible to obtain authorization from the student to confirm these data. Anyway, we think that these information does not detract from the student’s person. On the contrary, they refer to the pioneering role of student at the institution. We rely here on the legislation arising from ADI 4,815 (apudTomaz and Porto, 2015), which authorizes the production of biographies.

Received: August 31, 2020; Accepted: February 01, 2021

texto em

texto em