Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1413-2478versão On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.26 Rio de Janeiro 2021 Epub 14-Out-2021

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782021260066

ARTICLE

Multiliteracies and the feminine in memes by high school students of Instituto Federal do Mato Grosso do Sul

IUniversidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil.

IIInstituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de Mato Grosso do Sul, Aquidauana, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil.

This work presents the results of a teaching proposal carried out at Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Mato Grosso do Sul (Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Mato Grosso do Sul), Aquidauana campus, on the perspective of the pedagogy of multiliteracies. Its purpose is to analyze the process of (re)signification of the feminine before and after the teaching proposal, via an interpretative research approach, in memes produced by students of the technician courses of Buildings and Information Technology (IT). In a transdisciplinary perspective, it is based on studies on multiliteracies, meme, gender and feminism, and shows that the construction of meanings on the feminine happens via the questioning of the hegemonic norm of gender, as well as its accompanying policy of surveillance of the body and behavior of women. This occurs before and after the proposed intervention; however, some cases are qualitatively significant as to the changes in the construction of the female after the intervention, moving towards a greater empathy for human suffering.

KEYWORDS multiliteracies; meme; gender; feminine; high school

O trabalho apresenta resultados de uma proposta de ensino realizada no Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de Mato Grosso do Sul, campus Aquidauana, na perspectiva da pedagogia dos multiletramentos. Objetivou analisar, em memes produzidos por estudantes dos cursos de Edificações e de Informática, o processo de (res)significação do feminino antes e depois da proposta de ensino, por meio de abordagem interpretativista de pesquisa. De modo transdisciplinar, o artigo ampara-se em estudos sobre multiletramentos, meme, gênero e feminismo e mostra que a construção de sentidos sobre o feminino se dá pelo questionamento da norma hegemônica de gênero, em seus desdobramentos para a política de vigilância do corpo e do comportamento das mulheres. Isso ocorre antes e depois da proposta de intervenção, no entanto alguns casos são qualitativamente significativos quanto às mudanças na construção do feminino após a intervenção, na direção de maior empatia em relação ao sofrimento humano.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE multiletramentos; meme; gênero; feminino; ensino médio

El trabajo presenta los resultados de una propuesta de enseñanza realizada en el Instituto Federal de Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología de Mato Grosso do Sul, campus Aquidauana, bajo la perspectiva de la pedagogía de los multiletramentos. El objetivo fue analizar, en memes producidos por estudiantes de los cursos de Edificaciones y de Informática, el proceso de (re)significación del femenino antes y después de la propuesta de enseñanza, por medio de un abordaje interpretativista de investigación. En una perspectiva transdisciplinaria, se ampara en estudios sobre multiletramentos, meme, género y feminismo y muestra que la construcción de sentidos sobre lo femenino se da por el cuestionamiento de la norma hegemónica de género, en sus desdoblamientos para la política de vigilancia del cuerpo y del comportamiento de las mujeres. Esto ocurre antes y después de la propuesta de intervención; sin embargo, algunos casos son cualitativamente significativos en cuanto a los cambios en la construcción del femenino después de la intervención, hacia una mayor empatía hacia el sufrimiento humano.

PALABRAS CLAVE multiletramentos; meme; género; femenino; escuela secundaria

INTRODUCTION

This paper presents some of the results from a research on the meaning assignment processes of the feminine constructed in memes produced by high school students (also taking vocational training) at Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Mato Grosso do Sul (Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Mato Grosso do Sul), Aquidauana campus. Personal motivations, as well as the lack of discussions of this nature in the referred technological educational institution, are some of the reasons why we conducted a study with students from two vocational training courses, which are integrated to high school programs. The focused courses were Buildings and Information Technology (IT), and the initial purpose was to expand and build students’ knowledge about gender and feminism issues, based on the perspective of the pedagogy of multiliteracies (New London Group, 2006).

Two important facts have encouraged us, both for the concretization of the teaching project and for the discussion we propose here: on February 3, 2015, the first Brazilian Women’s House, a means of ensuring assistance to victims of violence, was inaugurated by President Dilma Rousseff in the capital city of the state of Mato Grosso do Sul. According to the 2014 Annual Balance of the Secretariat of Policies for Women (Brasil, 2014), Campo Grande was the Brazilian capital with the highest attendance rate recorded in the service; in 2016, it ranked second, staying behind only Brasília. Moreover, we diagnosed that, in Aquidauana - a small town located 139 km from Campo Grande -, the records of violence against women are notorious. This drove the city’s Executive, on November 7, 2017, to sanction law n. 2540/2017, which established the Municipal Week for the Combat of Domestic and Family Violence Against Women.

In our point of view, both the implementation of this law and the creation of the Women’s House corroborate the need to think about actions that can somehow reduce violence rates in the state. Bearing this context in mind, schools, as social institutions and as a place to shape and create human beings as social subjects, need to commit to promote discussions that allow a better awareness of the social place historically demarcated to women, in order to highlight the “violence and human suffering as constitutive of hegemonic and binarizing cultural formations of gender and sexuality” (Biondo, 2015, p. 211)1.

According to Miskolci (2017, p. 42), “it is in the school environment that collective ideals about how we should be begin to appear as demands and even as impositions, often in a violent way”. Such constructs are cultural - evidently, also political - and aim to conform the subjects to a hegemonic gender norm, and may lead to marginalization for those who resist it. Moreover, through reading, comprehension and oral and written production activities, the language classroom is a favorable place for the construction of meanings and reflection on how to act in the social world (Moita Lopes, 2002).

The aforementioned vocational training courses had Portuguese language classes, in which this project was developed. Our work, in this sense, focused on the reading, reflection and production of diverse and multimodal texts, in order to foster both critical awareness about cultural aspects, hegemonic and subversive formations of gender construction, and the work of signification from languages other than just writing - two educational axes implied in the pedagogy of multiliteracies (New London Group, 2006). In light of all the material produced by students and registered by the teacher responsible for these classes, we present a discussion about the meanings of the feminine in memes created by the students. In this sense, two basic questions guided us in this proposal: How does the process of (re)signification of the feminine occur in the memes produced by the students? Do the memes reveal any changes in relation to the meaning construction of the feminine, in comparison to the understanding of these students before the teaching project?2

It is also worth mentioning that this initiative is intended to align with the proposals of the Federal Institute of Mato Grosso do Sul, since its political course project contemplates “initiatives aimed at professional qualification, community development, political training, and numerous cultural issues guided in spaces other than the school” (Instituto Federal do Mato Grosso do Sul, 2017, p. 8).

MULTILITERACIES AND THE MEME

Multiliteracies pedagogy was proposed by a group of scholars known as The New London Group (NLG), in 1996, in view of the expansion of the use of digital technologies in society and with the goal of broadening literacy pedagogy, in order to connect multiple cultures and the diversity of texts in circulation in social practices. According to such researchers, literacy pedagogy should, henceforth,

account for the growing variety of text forms associated with information and multimedia technologies. This includes understanding and mastering competently forms of representation that are becoming increasingly significant in the global communication environment, such as visual images and their relationship to the written word. (New London Group, 2006, p. 61, our translation).

By turning its gaze to multisemiotic texts involved in the production of meaning, the NLG points to the relations of similarity, distance or complementarity of other modalities (image, color, sound) with writing, creating space for new thoughts concerning the traditional graphocentric practices in formal teaching-learning institutions and/or situations. The complementarity of languages is fundamental in contemporary literate practices, which need to be understood in their diversity, “in a broader perspective than that of conventional graphocentric literacy with its textual and graphic-visual patterns, typical in print media” (Signorini, 2012, p. 284).

In this paradigm, for Knobel and Lankshear (2006), we must see reading and writing as ways to make sense of our experiences in the world, shifting comprehension processes to particular cultural universes and understanding that different types of texts also require “backgrounds and skills somewhat different” (Knobel and Lankshear, 2006, p. 2). It is assumed, therefore, an expansion of writing and reading skills, presupposed in the immersion in multiple practices regarding culture and, in general, based on hypermedia.

The authors point out that many of the changes in reading and writing processes today are linked to the expansion and broadening of the use of digital, networked technologies. Such use demands new things to be done, keeping up with the continuous changes related to digital networks and technologies, as well as paying attention to the social, cultural, and political contexts, which will have a great influence on the practice of reading and writing. Thus, schools need to promote skills to aid students in dealing with an approach to language use that is attentive to cultural multiplicities and textual multisemiotics, especially those amplified by hypermedia (Knobel and Lankshear, 2006; New London Group, 2006).

Among the multimodal texts in circulation in the digital world, memes, the object of analysis of this paper, is a term which has been constituted many years ago, as an apheresis of mimeme, as proposed by biologist Dawkins (2017). According to this author, “Mimeme”, of Greek etymology, has the same root as mimesis and means imitation. The initial phoneme was intentionally deleted, as Dawkins (2017) sought a simple name whose phonetic sequence resembled “gene”, resulting in “meme”. Based on a Darwinian perspective, the author presents an analogy by stating that, just as genes replicate through the process of duplication of a double-stranded DNA molecule, the meme is responsible for cultural replication, which occurs through the social activity of transmitting information. In his view, replication occurs by genetic and cultural factors, the latter understood as behaviors, habits, ideologies, and values spread through imitation or copy.

When addressing this digital genre in the field of language, Recuero (2018, p. 124) states that “the propagation of the meme is cyclical and does not always imply the faithful reproduction of the original idea. On the contrary, changes and transformations are frequent and compared, in his approach, to genetic mutations: essential for the survival of the meme”. The author also states that memes are propagated based on the perception of the social gain that the person who disseminates it will obtain. The researcher calls this motivation social capital; in other words, it is what drives someone to spread the meme: reputation, visibility, popularity etc.

As for their composition, according to Inocêncio (2016, p. 10), memes are built from repetitions of a primary model, which can be transformed in various ways, through intertextuality and via retextualizations that usually distance themselves from the original version, even though this can be identified. For the author, they are a way to express oneself and to participate socially, and are capable of expanding debates and political actions of subjects in their interactions on the internet, enabling other ways of “being” on the web.

Milner (2012, p. 48) points out that memes function almost entirely as a joke, except that some of them require reflection on political issues, and, like other popular culture texts, can act as “a powerful political satire”. For the author, memes are still often used as a representation of discourses and identity, so as to reinforce, once again, its political character. Thus, reflecting on how memes are made can reveal aspects of the social participation of subjects, since individual choices intertwined with cultural connections are revealed via the formal elements of a text (Milner, 2012).

Because it is a multisemiotic text, we also know that, in the production of a meme, there is quite some work in relating verbal and imagetic languages, so that, together, they produce an effect of meaning imbued with social criticism. Therefore, in the process of creating a meme, even if they are not aware of it, students choose the image that best suits the criticism exposed in verbal language - and vice versa, making multiple semiosis operate together in the production of meanings. In this perspective, Kress and Van Leeuwen (2006) claim that, when producing signs, people make formal choices in order to align with the meanings they intend to express, in any medium in which it is immersed.

In order to bring pedagogical practices and the social world closer together, we chose the meme genre for this study, not only because it is part of the students’ daily relations with language, but also with the purpose of engaging them in the discursive practices of the classroom. By proposing the construction of this genre, whose circulation occurs almost solely through social networks, we corroborate Rojo’s (2009, p. 12) proposal that it is also the school’s task to “enhance multicultural dialogue, bringing within its walls not only the valued, dominant, canonical culture, but also local and popular cultures and mass culture to make them voices of a dialogue, objects of study and criticism”.

We further understand from Barton and Lee (2015, p. 48) that the producer of an online circulating text, such as the meme, is a “designer”, as it is up to him or her to choose among layout options, images, and other available languages, which especially underlines the notion of no neutrality in text. Following Fabrício’s (2006, p. 48) conceptions, we assume that “our discursive practices are not neutral, and involve ideological and political choices (intentional or not), crossed by power relations, which cause different effects in the social world”.

Therefore, working with memes may “embody the best of participatory media: democratic participation, diverse dialogue, and relevant debate” (Milner, 2012, p. 22), as well as the possibility of challenging naturalized discourses, providing opportunities for questioning and resignification. From this perspective, producing this textual genre can be an important learning practice, a way to participate and act in social life by engaging in social network interactions in the context of rapidly expanding internet access (Knobel and Lankshear, 2006).

In view of these possibilities, we understand the production of memes as a way to expose and question social places and behaviors traditionally reserved for women. We dedicate ourselves to this theme in the following section.

GENDER AND THE FEMININE

Gender studies, although far from being organized as a totally homogeneous field, usually share a common ground: the questioning of the historical subordination of women in relation to men. For Matos (2008), all areas interested in discussing gender issues should start from this point in order to understand and to launch explanations about the various faces of dominance and oppression that involve gender relations. From this common place, social movements and epistemologies were built around the subject “woman”, initially, and on the idea of “gender”, from the mid-1970s and strongly in the 1980s.

When questioning the historical subordination of the feminine, Saffioti (1987, p. 11) points out that it is a naturalized process in our culture, as discrimination against other social categories, and warns that naturalization is “the easiest and shortest way to legitimize the superiority of men” (white, heterosexual, middle class, Christian), considered in its humanist reference. The author understands naturalization as a certain social construct that seems unquestionable, as if it were given by nature. It is also in this direction that Louro (2003) highlights the way society classifies and labels the subjects, dividing them between opposite poles of categories and fixing their identities. For the author, “it defines, separates and, in subtle and violent ways, also distinguishes and discriminates” (Louro, 2003, p. 16).

In order to destabilize this naturalization, gender studies developed in the wake of postmodernity and posthumanism strongly question gender norms instituted in society. Based upon post-structuralist thoughts that were spread in France in the 1980s, especially by Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida’s ideas (Narvaz and Koller, 2006), studies on gender performativity and queer theories (Nelson, 2006; Louro, 2008; Butler, 2017), for example, assert the need to understand gender categories and stereotypes as social constructions that take place in interaction and language.

To Butler (2003, 2018), gender performativity has to do with the power of language to promote actions in the social world. Thus, performing gender is equivalent to an action, to a way of making gender exist or happen, and, in this way, it is possible to subvert the gender norm established by Western culture, expanding the possibilities of existence of gender identities. According to this norm, there would be fixed social and sexual behaviors for one or the other side of the male/female binary.

The “famous” scholar suggests the deconstruction of “gender binarism” in order to denaturalize it, since, according to her, the act of classifying people as male or female based on their biological sex imposes on human beings behaviors and social expectations, preventing them from constituting their individuality. In this view, people who do not meet these “social expectations” are marginalized. Thus, the philosopher claims that language practices play a key role in the process of gender signification in culture, because they are constructed according to power relations that can prescribe discourses of invisibility for the category of woman, for example. According to Butler (2003, p. 161), “naming is both the establishment of a boundary and also the repeated inculcation of a norm”.

In this same vein, Goellner (2003, p. 29) states that “language does not only reflect that which exists. It creates the existent itself, and, in relation to the body, language has the power to name it, classify it, define its normalities and abnormalities”. Keeping this in mind, as we understand language in a broad way, resonating the theories of multiliteracies that have guided our work and this paper, image is also a way to (re)signify gender in our society. Thus, according to Sabat (2003, p. 150), “the construction of images that value a certain type of behavior, lifestyle or person is a form of social regulation that reproduces more commonly accepted standards in a society”. Once there is awareness about these forms of control, it is possible to establish a position of resistance and to question the hegemonic gender order.

It is worth noting that, in the context of interaction, when subjects perceive discourse as a social construction, they can see themselves as real actors in the construction of meanings in the social world, which includes “the possibility of allowing resistance positions in relation to hegemonic discourses, that is, power is not taken as monolithic and social identities are not fixed” (Moita Lopes, 2002, p. 55).

It is in this perspective that we understand the real need for schools to be responsible for discussing oppressive gender norms in their relation to the female subject, as well as to establish themselves as a resistance to the social-discursive constructions that act in the configuration of oppression, in order to reduce inequalities, and, consequently, human suffering. In this sense, based on Hooks (2018, p. 47), we believe that “unless we work to create a mass movement that provides feminist education for everyone, women and men, feminist theory and practice will always be weakened by the negative information produced in most mainstream media” (Hooks, 2018, p. 47-48).

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Our research is in the field of applied language studies and, thus, it is important to understand that its theoretical and methodological approaches have a complex nature, since it involves a varied set of theories that mark its multidisciplinary character. To analyze the object from a perspective that involves several fields of knowledge, as Kleiman (1998, p. 66) points out, “is to identify major social problems which may interest more than one area and whose study needs the efforts of several subdisciplines of Applied Linguistics”. Rajagopalan (2003) also emphasizes the importance of interaction with other branches of knowledge, as, for him, “the great moments in the history of linguistics have invariably been those in which there has been intense interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary dialogue around broader issues involving language” (Rajagopalan, 2003, p. 40-41).

In addition, our research is interpretive and qualitative, as the data generated and collected was analyzed via the progression of the proposed steps in which we were involved as teachers and researchers. For this reason, it is also an ethnographic research, given the daily immersion of one of the researchers in the research field and the process of deliberate involvement in the analysis of the data. This is an important characteristic of research in Applied Linguistics, in which there is concern about the characterization of the participants and the “situational, institutional, and microsocial context in which they operate” (Kleiman, 1998, p. 61).

Moreover, given the importance of triangulation of more than one type of record to be configured as data in qualitative research, this study had its corpus of analysis built by the production and collection of the following records: online questionnaires, audio recordings of classes, notes in field diary, and also interaction and proposed activities in a private page created on Facebook. These records were developed from a teaching project conducted in the high school vocational training course of the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Mato Grosso do Sul, Aquidauana campus, as aforementioned.

The teaching project was carried out from May 22 to June 12, 2018, in order to promote the critical engagement of students of this vocational training, as well as to enable the reading and production of multimodal texts, meeting the pedagogy of multiliteracies. It involved a total of 58 students from the 5th semester of two vocational training courses integrated to high school, namely the Buildings and the Information Technology (TI) courses, composed of 26 and 32 students, respectively.

The first step consisted of the application of a 20-question questionnaire - 3 of which were essay questions and 17 multiple-choice questions -, organized by the teacher using Google Forms. After answering the questions, the system itself structured the answers, generating graphics for the questions, helping in the organization and analysis of the data. The key question which, besides giving us a diagnosis of what they understood about the issue, allowed us to plan the next steps, was: what is feminism? Besides this question, other questions were asked about the understanding of the concepts of feminism, gender, and sexism, as well as others about traditionally feminine social behaviors.

After gathering the answers, we conducted the first analysis of the information generated, which allowed us to think about which activities could be proposed for the intervention/teaching project - which was a period of reflection and debates, as well as the reading and production of texts regarding the theme addressed. In order to illustrate the students’ first considerations about the issue, we present, in Table 1, six answers to the key question - “what is feminism?” - which we consider representative.

Table 1 - Answers from students of Instituto Federal do Mato Grosso do Sul to the question “what is feminism?”.*

| “A movement in which women want to benefit from equality” |

| “Equal rights, in which women believe in equality.” |

| “Movement made by women to try to have space in society.” |

| “Feminism to me is a ‘fight’ of women, even men, to fight a conservative society, sexist groups. Showing that women are able to perform any activities, perform any profession they wish, without being seen as ‘macho women’, seen as WOMEN, capable women who can and are prepared to perform diverse tasks, which, until recently, were performed only by men.” |

| “An ideology that supports and places women as the center of society.” |

| “Women’s struggle for equality in the society we live in, bringing recognition to both women and men, without demeaning any individual.” |

Source: Authors’ personal file, 2018.

*The answers were translated from Brazilian Portuguese by the authors.

Considering these answers, we observed that there were, among the students participating in the research, those who thought that feminism is a movement that circumscribes only women, or that its objectives would be the inversion of power between men and women. In order to promote questioning and broaden visions regarding the theme addressed, resignifying common sense notions, we followed the understanding that “feminism is essentially plural, a philosophical project of social and political transformation against oppressions of sexuality, gender, race, belief, and social class” (Pinto, 2018, p. 11). Guided by this understanding, we proposed four intervention meetings, which were recorded in video, and, at points, in a field diary. As for the activities, we chose to work with different textual genres (comic strips, opinion articles, music and video clips, news reports, and memes), in order to discuss how the female figure was constructed in these texts.

THE TEACHING PROJECT IN WHICH THE DATA WERE GENERATED

When approaching gender identity and feminism themes in the classroom, we sought to promote means and discussions that would allow students to contest, (re)elaborate and (de)construct discourses.

Thus, we started the first meeting with the song “Desconstruindo a Amélia” (“Deconstructing Amélia”), by Brazilian singer Pitty3, exploring lyrics and audio. Besides a suggestive title4, given all the semantic charge attributed to the name Amélia - synonymous with housewife -, the song brings in its narrative the stereotype of the woman in a patriarchal culture. However, she, at a certain point, no longer accepts the condition she is in and decides to change the outcome of her story. The song’s lyrics reveal social constructs naturalized as proper and exclusive to the “feminine universe”, mainly regarding domestic services (“The opportunity made her so gifted/ She was educated to take care and serve [... ]), but these constructs are questioned (“Turn the table, take over the game/ She makes a point of taking care of herself/ Neither servant nor object/ She no longer wants to be the other/ Today she is one too”), in order to highlight the subversion of behaviors culturally linked to female subjects. It is also worth mentioning that we chose this song because of its popularity among students in the research context. Moreover, Pitty, who is a Brazilian singer, has gradually gained the spotlight in discussions of gender, because many of her songs’ content presents critical views regarding oppressive discourses that are culturally naturalized.

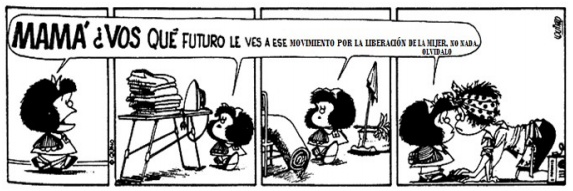

In a second moment, we presented some Mafalda comic strips by Argentinean cartoonist Joaquín Salvador Lavado Tejón, known as Quino. As a contextualization activity, we exposed the nationality of the producer of the strips, so that, besides situating the space given to the feminine in another country, we could also raise questions about possible similarities (or not) with the Brazilian cultural reality. Considered by many as a transgressor, Mafalda, always portrayed as a child, is a character that usually brings many reflections about the regulatory norms that define what is “appropriate” to the feminine. She often criticizes the way her mother and her friend Susanita reinforce normative representations of patriarchal domination. The Figure 1 is one of the Mafalda 5 strips that we used in our intervention project.

Source: My Hero, 2006. Available at: https://myhero.com/Mafalda_lyon_france_06_ul. Accessed on: May 14, 2018.

Figure 1 - Mafalda comic strip.*

In a subsequent class, we presented the April 18, 2016 article from the Veja magazine, authored by Juliana Linhares, entitled Marcela Temer: bela, recatada e do lar (Marcela Temer: a beautiful and demure housewife), which was the subject of much debate at the time of its publication, especially for the accusation that it reinforced cultural stereotypes reserved for the female gender by means of using the image of Brazil’s then first lady, Marcela Temer. We proposed a discussion on the politics of “power over the female body”, which has been on the feminist agenda in its various movements and strands (Del Re, 2009, p. 20), as well as the need for the other’s gaze in the cultural constitution of the feminine, highlighted by Bourdieu (2014, p. 97), who stated that women “are continuously guided in their practice by the anticipated assessment of the appreciation that their bodily appearance and their way of carrying the body and displaying it may receive”.

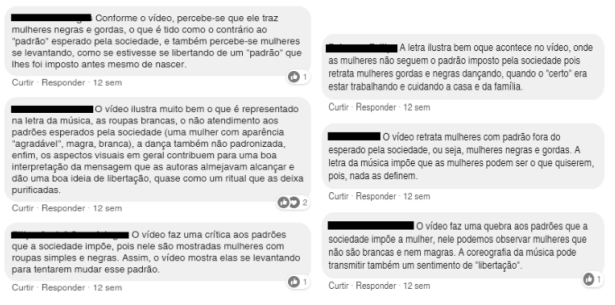

The other classes from the project were held in the IFMS computer lab, which is the best equipped basic education institution in the city in terms of technological apparatus. Currently, it has six computer labs, which have allowed the development of activities involving various languages and internet access. This gave us the opportunity to create a private group on Facebook, to which we added the students and at which we proposed two activities: the publication of a comment about the lyrics and the music video of the song “Triste, Louca ou Má” (“Sad, Crazy or Mean”), from the Brazilian group Francisco, el Hombre (2016); and the production of memes that represented their positions regarding the issues that had been discussed in class, about the social construction of gender.

Regarding the video clip, we used the following production command: “Listen to the song and watch the video. After that, make a comment on the visual elements used in the video that contribute to the production of meaning (relate lyrics and video)”. The choice of the video clip was motivated by its intertextualization with The Second Sex, by the well-known feminist theorist Simone de Beauvoir, as well as for being a text that mobilizes multiple semiotics. Although these comments are not analyzed in this paper, we consider it relevant to mention that they were produced individually, that is, without interaction with colleagues, as it would be usual on Facebook. We believe this may be related to the fact that the context within this social media is still directly connected to a school assignment, and more than that, to an evaluation school assignment; as illustrated by some examples reproduced in the sequence (Figure 2), students only liked other classmates’ posts, but did not comment on them. The English translation for each of these comments can be found on Table 2.

Source: Authors’ personal file, 2018.

Figure 2 - Comments about the video clip posted by students on Facebook.

Table 2 - Comments about the video clip posted by students on Facebook (English translation).

| As you watch the video, you notice that it features fat black women, which are understood as the opposite of the “standard” expected by society, and you also notice women standing up as if they are freeing themselves from a “standard” that was imposed on them even before they were born. | The lyrics of the song illustrate well the images presented in the video. The women do not follow any socially imposed standard, because they are fat, black dancers. According to the lyrics of the song, it is expected that they stay at work and take care of the house and the family. |

| The video illustrates very well what is represented in the lyrics of the song; the white clothes, the non-conformity to the standards expected by society (a woman with a “nice” appearance, thin, and white), the dance, which is also non-standardized/choreographed, are all aspects that contribute to the interpretation of the message that the lyrics seek to achieve, because it provides an idea of liberation, almost like a ritual that leaves them purified. | The video features women outside the socially expected standard, that is, black and fat women. The lyrics express women can be whatever they want, because appearances and possessions do not define them. |

| The video criticizes the standards that society imposes, because it shows black women wearing simple clothes. Thus, the video shows them standing up in order to question the imposed standard. | The music video presents a breaking of standards regarding what society expects from women, since we notice that the women are neither white nor thin. The choreography of the song can also convey a feeling of “liberation”. |

Source: Authors’ personal file (2018).1

1 The translations are arranged in the same position as the original answers in Image 2.

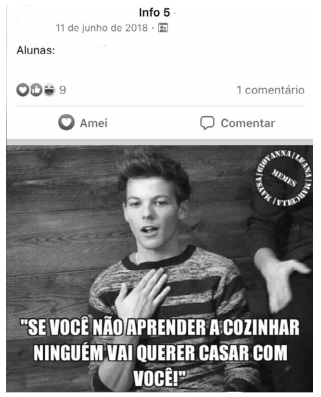

As for the activity of producing memes, we suggested the classes should be divided into groups of 3 to 5 members. Afterwards, we asked them to use the website https://www.gerarmemes.com.br/, or any other online address that they knew and/or had affinity with, in order to produce memes that represented some of the gender issues discussed in class. Each group had to create at least three memes. Once they had finished, the productions should be published on the Facebook page with the names of the people in the group, as shown in Figure 3.

Source: Authors’ personal file, 2018. Translation of written content in the image: If you can’t cook, nobody will want to marry you. *For ethical reasons, we chose not to use the names of the students involved in the research. Since the memes were produced in groups, we refer to the producers as students.

Figure 3 - Meme and group identification.*

Given the interpretativist perspective of this study, among the 43 memes produced, due to length issues, we chose two of them for analysis: one from an IT course group (composed of four female students) and one from a Buildings course group (composed of two male students and two female students).

The choice of examples was due to their representativeness as to the meanings of feminism presented in the set of productions. These two memes were also chosen because they are examples that reveal some of the changes related to such constructions before and after the teaching project briefly situated here. It is worth mentioning that the analyses reflect the teacher-researchers’ critique of the students’ critique, presented via memes. These analyses are also based on the questionnaires and field impressions, notes and observations, in line with ethnographic studies.

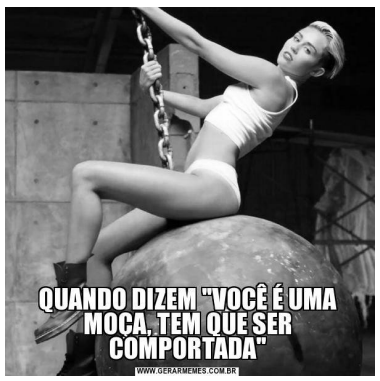

CONSTRUCTIONS OF FEMININITY IN MEMES: ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

In all the memes produced, we observed processes of (re)signification of the feminine based on the themes and agenda of contemporary gender theories, such as equal rights, policies against violence, intersection between gender, sexuality, and race, among others, which were discussed in the classroom. In the case of the memes selected for analysis, like many others that made up the corpus of this research, the meanings of the feminine are constructed by questioning the hegemonic gender norm, in its unfoldings for the policy of surveillance of the female body and women’s behavior, above all. This is what the meme on Figure 4, produced by the group of students from the IT course, illustrates.

Source: Authors’ personal file, 2018. Translation of written content in the image: When they say “you are a girl, you should have good manners.”

Figure 4 - Miley Cyrus meme.

In this example, the image of the famous American singer and actress Miley Cyrus, dressed in white6 and clutching a wrecking ball is presented in the background, to which the text “When they say ‘you are a girl, you should have good manners’” is superimposed. Together and by contrast, the image and the written message refer to the behaviors traditionally related to the feminine and apprehensible from the news article Bela, recatada e do lar, discussed with the students during the teaching project. The written content is what guides our understanding, as it is positioned in the foreground and focuses on the idea that women should behave “accordingly”; nevertheless, it is only by the junction between the image and the written content selected for the production of the meme that the latter is revealed as ironic: in opposition to the presupposed coy woman, the singer’s image alludes to the daring woman and questions the moral vigilance regarding female behavior, resignifying the stereotype of the coy woman, still very present in contemporaneity, as the aforementioned report showed.

It is interesting to note that Miley was, for some years, the protagonist of the children’s show Hannah Montanna, produced by Disney Channel, and had an established image with this audience. However, in her later works, specifically from the album Bangerz, released in 2013, on, the singer shows herself in a more daring and adult version, distancing her image from the puerile universe, and, concomitantly, placing her in a younger pop scenario. Currently, she is quite popular among the latter audience and is engaged in feminist agendas; she often exposes on her Instagram profile messages about female empowerment and demarcates her resistance to hegemonic gender discourses.

The synthesis is important for us to understand the possible motivation of the students who produced this meme: four teenagers who followed the whole process of transition of the artist, as we identified in an informal conversation with the group and recorded in the field journal. The picture used is a scene from the music video Wrecking ball, in which Miley appears first naked and then wearing short clothes. In an interview for Elvis Duran and the Morning Show (MILEY CYRUS AND MARK RONSON…, 2018), she revealed that her nudity in her music video is a metaphor for how vulnerable she feels.

The vulnerability mentioned by the singer herself can be inferred, in the meme, by the contrast between the idea of lightness (little clothing and the white color, detached position of the character throwing the body back) and the representation of strength (wrecking ball, heavy work boots, contrast of white with the colors gray and black, serious expression and gaze directed to the reader/observer). It is, therefore, a construction of the feminine that does not remain only in the unilateral stereotypes of the “beautiful and demure housewife”, but integrates strength, daring and a projection of power traditionally attributed to the masculine. It is to this last semantic field that Miley’s short hair also refers, along with other attributes of strength culturally associated with men and contrary to the ideal of behavior presented ironically through the written sentence.

Regarding the social construct of power, it is also pertinent to note that the vertical angle presents the image captured from bottom to top, suggesting, according to Kress and Van Leeuwen (2006), that the represented participant holds power. According to Riot-Sarcey (2009), power has always been at the center of human struggles and crises, circumscribing itself, in gender relations, to the male figure and the exclusion of women from “power as potency” by the subjection to their husbands embedded in the culture of patriarchy. The “free woman”, in turn, would have always been related to the public, scandalous, and, therefore, subjugated woman. For the author, by fighting “for equality, feminism is for women the means to reach both the power of speech and the power of action” (Riot-Sarcey, 2009, p. 188).

Therefore, the meanings of the feminine constructed by the group of students through the semiosis enabled by the meme overcome some of the constructs and social and hegemonic expectations related to the feminine gender. This overcoming is corroborated, in our view, in the suggestion of movement implied in the image of the wrecking ball, which alludes to destruction, and, simultaneously, to reconstruction. In this sense, these meanings are similar to what some students in this same group understood about gender before the intervention proposal. This is what we observed in the answer of one of them, when asked about what she understood by feminism: “It is a kind of popular movement among women, with the goal of equalizing who is ‘more’ in charge, to make everything reach a certain balance between men and women”. Another student in the group, before the intervention, also seemed to have ideas about the feminine similar to those that can be inferred from the meme. When asked what she meant by sexism, she answered that it was “the act that some men commit, thinking that they are ‘superior’ to women in everything. For example: men are paid to work in society while women must take care of the house and the children. It’s as if women do not have the right to have a ‘voice’”.

On the other hand, and as an example, one of the students in the group seemed to have a very different understanding of the topic from what was presented by the meme. When asked what she understood by “feminism”, she said she understood the movement as a “doctrine of extreme (sic) equality of the female figure in relation to men”. Besides the negative connotation apprehensible from the use of the lexicon “extreme”, the student stated that she did not believe in the existence of gender prejudice and sexism in our society. Although we cannot assume that the ideas of the analyzed meme represent, in fact, the meanings of the feminine for all the students in the group, we consider it remarkable the participation of the latter in the production of meanings as distinct as the ones she presented before her involvement in the class activities.

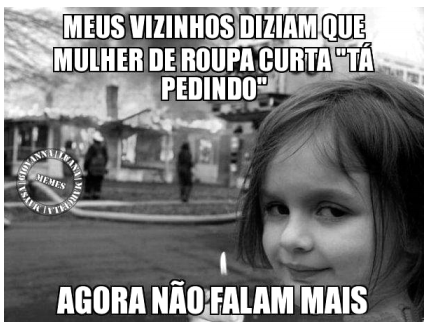

A similar movement can be observed in Figure 5. In it, two sentences are foregrounded (one at the top and one at the bottom of the figure) because of a background image: a little American girl, Zoe Roth, observing a fire department flame control test. According to information circulating on the internet (Donovan, 2018), her father took the picture and published it later with the caption Firestarter, suggesting that the girl had started the flames. This image was one of the most popular on the internet in 2004, became known worldwide as “disaster girl”, and has since been replicated in thousands of internet memes on a variety of topics.

Source: Authors’ personal file, 2018. Translation of written content in the image: top: My neighbors said that women wearing short clothes are “asking for it”. Bottom: Now they don’t say that anymore.

Figure 5 - Zoe Roth meme.

The written content at the top (“My neighbors said that women wearing short clothes are ‘asking for it’”) refers to one of the gender themes worked in the classroom, the issue of surveillance over the female body in the patriarchal system. Ultimately, they refer to the victim’s supposed guilt in “rape culture”, that is, the “set of symbolic violences that enable the legitimization, tolerance, and encouragement of sexual violation” (Sousa, 2017). Positioned at the bottom of the figure, the phrase “Now they don’t say that anymore” complements not only what is written at the top, but also the image in the background. Zoe’s sarcastic smile and gaze towards the viewer in the background are added to the image of a burning house in the foreground and introduce the ironic and debauched tone of the meme: a critique of the control over the length of clothing worn by women, culturally related to the idea of “insinuating” oneself to men and stereotypically linked to the ideologically constructed relationship between clothing and morality.

As we discussed in class, the idea of surveillance over the female body has been one of the topics on the feminist agenda since its emergence in the context of the suffragist movement inaugurated in France in the 1870s (Del Re, 2009, p. 21). The issue of who has the right over the female body (the state, medical corporations, the patriarch of the family, religious authorities, or the woman herself) has cut across feminist discussions of motherhood and abortion, as well as street protests, ever since, and has resurfaced strongly in right-wing discourses in recent years, which have generally refused to “see women as autonomous subjects” (Del Re, 2009, p. 24). By ironizing the issue through the choice of image and written content presented in the meme, the group references the relationship between the control of the female body and the social construction of morality that constitutes gender relations. According to Cornell (2018, p. 128), it is the idea of morality that underlies every attempt “to explain theoretically how it is possible to determine a system that absolutely governs the ‘right way to behave’”.

In the meme, the reader’s attention is directed to the girl’s face, which remains sharp in the picture, in contrast to the image in the background, which appears blurred. By presenting and drawing attention to a female child character, the meme also raises criticism that is usually presented about the “docility and resignation as expected characteristics of little girls” (Lakoff, 2010, p. 21). The image subverts this norm by presenting a girl who, in an act of nonconformity, sets fire to the house of those who bothered her - the ideas of the meme align with this critique in order to question it. The comic effect is then built, in the meme, mainly by focusing on Zoe, a female and childish figure, holding a candle (a symbol traditionally linked to the spiritual world, and, sometimes, to the dark universe) with an expression of satisfaction after having solved a problem that bothered her: the surveillance and moral judgment of neighbors about the size and model of her clothes.

It is worth mentioning that, during the course of the teaching project, there was a concern on the part of the teacher with the aspect of violence that could also be apprehended from the meme. When talking to the group in class, the teacher mentioned his concern by establishing a relationship with the popular saying “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth”, and questioning the students about the risk of responding to violence with violence. The students, however, said that the image, in its multiple resignifications on the internet, is commonly associated with some problem that, roughly speaking, can be “solved quickly and simply”, not necessarily in its aspect of violence. As the students mentioned, the idea of the meme consists in exposing some uncomfortable situation and suggesting an immediate way to solve it, in a comical and ironic way. Although it may sound violent, this multimodal production shows that students have contact with social networks, and, above all, that they understand the dynamics attributed to the image, as they follow the model of use/replica characteristic of memes. Therefore, we consider this could be a possibility for teachers who wish to work with the theme of violence in other (multi)literacy projects.

In any case, the subversion of the gender norm that accounts for judgments related to social behaviors assigned to the feminine (Butler, 2017) in the meme suggests an alignment of these students with some of their stances on the issue prior to the teaching project. This is the case of one of the students in the group, who, in a questionnaire that preceded the classes, stated that sexism is

an attempt to block women’s rights. We have some sayings which could be used as examples, such as: “A woman’s place is in the kitchen”, in traffic we use the expression “It had to be a woman”, when we walk alone with shorts which are above half of the thigh, they say, “Look there, she is asking for it”. In everyday situations, we see sexism, even in the right to have relations (sexual or not) with people. For example, if a girl hooks up with several boys, she gets a bad “reputation” (“slut, whore” and several other vulgar words), but if a boy hooks up with several girls, he gets a good “reputation”, of “stud”, “handsome”, “conqueror”.7

According to this same student, feminism is “the act of fighting for women’s rights. Some examples [of rights] already conquered are: voting, going to college, working outside of the home. Today we fight for the end of domestic violence, for the right to walk safely unaccompanied, and for several other reasons”. It is also interesting to note that one of the students in the group mentioned he had had, in a previous year, a sociology class and a lecture in which the theme of gender relations was discussed. According to him, in these previous moments, he had learned many things about women’s rights, and also that “we should be what we want, and if we are happy, why should we have to listen to the opinion of others?”.

This data, combined with some student responses about discussions of gender that they had followed on television or on the internet, leads us to point out that all of the criticism about the issue presented in the meme is possibly not only the result of the teaching project of this research. As we have briefly shown in the analyses, many of the students had already had knowledge about the topic and constructed meanings about the feminine in a similar way to what was presented through the memes. However, among the cases of change that caught our attention and allowed us to answer our second research question, we highlight one that revealed changes we consider significant regarding the construction of the feminine after the implementation of the teaching project. This student was part of one of the groups analyzed. In an informal conversation with the teacher at the end of the intervention, she mentioned having been abused by a religious leader and concealed the violence at the request of her family, in order to preserve the image of the abuser. As the student reported, before the classes, she felt guilty for what had happened, however, “now [she] understand[s] that it is something much bigger than [her]”.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

This article presented some of the resignifications of the feminine constructed by students from two vocational training courses at the Federal Institute of Mato Grosso do Sul, Aquidauana campus, before and after the completion of a teaching project on gender issues and physical and moral violence related to women. The project, carried out between the months of May and June, in 2018, had the participation of 58 students from the 5th semester, and was the setting of data generation. Bearing in mind the high rates of gender violence in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, the project was also designed to compose a set of educational actions that should be connected with critical and empathetic to human suffering citizen training - in this case, the suffering linked to gender relations.

Among the records generated and collected through the project, we selected the memes produced on Facebook by two groups of students. In a transdisciplinary perspective in applied language studies, we based ourselves on theories about the pedagogy of multiliteracies, relating memes, gender and feminism, in order to better understand the following questions: How does the process of (re)signification of the feminine take place in memes produced by students? Do the memes reveal any change in relation to the meanings of the feminine, in comparison to the understandings of these students before the teaching project was carried out?

As presented in the two examples from two different groups, the students, through the association between written language and images, constructed and developed meanings about the feminine based on the subversion of the hegemonic gender norm set by modern Western culture. They did so via the production of memes, appropriating meanings in circulation in contemporary social networks and retextualizing issues through social critique - one of the skills involved in the production of memes and expected when working with the pedagogy of multiliteracies.

Moreover, we observed that the constructed meanings of femininity differed, in some cases, from the ones the students demonstrated before the intervention proposal. Although, as we emphasize, we cannot (nor do we intend to) infer that such proposal has influenced great changes, in quantitative terms, to students’ constructions about the issues raised in classroom, each example, during and after this study, has shown us the importance of critical educational work, engaged and attuned to the power relations that generate suffering among students, inside and outside of the educational institutions.

In this regard, we mobilize the voices of two students who participated in the research to finalize our considerations and highlight the idea that “gender identity is something that is not often discussed, many people suffer in silence, without being who they really are, without accepting themselves, for fear of what their friends or family will think, and when this is addressed, some doubts can be resolved”; as well as to draw attention to the fact that, if educational institutions

performed actions to clarify and raise awareness among their students, we would have a decrease in cases of hate and prejudice, as well as new ways of fighting these evils that change and cause so many negative impacts on the lives of those who suffer them. In this way, we would use the best possible tool to fight them: education.

REFERENCES

BARTON, D.; LEE, C. Linguagem online: textos e práticas digitais. Tradução: Milton Camargo Mota. São Paulo: Parábola, 2015. [ Links ]

BIONDO, F. P. “Liberte-se dos rótulos”: questões de gênero e sexualidade em práticas de letramento em comunidades ativistas do Facebook. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, v. 15, p. 209-236, 2015. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-639820155871. Acesso em: 23 ago. 2021. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. A dominação masculina. Tradução: Maria Helena Kuhner. Rio de Janeiro: Best Bolso, 2014. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Secretaria Nacional de Políticas para as Mulheres. Balanço 2014 Ligue 180: Central de Atendimento à Mulher. Brasília: Secretaria Nacional de Políticas para as Mulheres, 2014. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.mulheres.ba.gov.br/arquivos/File/Publicacoes/Balanco_Ligue180_2014.pdf . Acesso em: 11 maio 2018. [ Links ]

BUTLER, J. Corpos que pesam: sobre os limites discursivos do “sexo”. In: LOURO, G. L. (org.). O corpo educado: pedagogia da sexualidade. 2. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2003. p. 151-172. [ Links ]

BUTLER, J. Problemas de gênero: feminismo e subversão da identidade. Tradução: Renato Aguiar. 13. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2017. [ Links ]

BUTLER, J. Corpos em aliança e a política das ruas: notas para uma teoria performativa de assembleia. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira , 2018. [ Links ]

CORNELL, D. O que é feminismo ético? In: BENHABIB, S. et al. (org.). Debates feministas: um intercâmbio filosófico. Tradução: Fernanda Veríssimo. São Paulo: Editora da Unesp, 2018. p. 117-160. [ Links ]

DAWKINS, R. O gene egoísta. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2017. [ Links ]

DEL RE, A. Aborto e contracepção. In: HIRATA, H. et al. (org.). Dicionário crítico do feminismo. São Paulo: Editora da Unesp , 2009. p. 21-22. [ Links ]

DONOVAN, F. Disaster girl meme explains what was really happening. Unilad, 12 out. 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.unilad.co.uk/featured/disaster-girl-meme-explains-fire/ . Acesso em: 5 nov. 2018. [ Links ]

FABRÍCIO, B. F. Linguística aplicada como espaço de desaprendizagem: redescrições em curso. In: MOITA LOPES, L. P. (org.). Por uma linguística aplicada indisciplinar. São Paulo: Parábola , 2006. p. 45-65. [ Links ]

FRANCISCO, EL HOMBRE. Triste, louca ou má. YouTube, 5 out. 2016. 4min29s. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lKmYTHgBNoE . Acesso em: 11 jun. 2018. [ Links ]

GOELLNER, S. V. A produção cultural do corpo. In: LOURO, G. et al. (org.). Corpo, gênero e sexualidade: um debate contemporâneo na educação. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2003. p. 30-42. [ Links ]

HOOKS, B. O feminismo é para todo mundo: políticas arrebatadoras. Tradução: Ana Luiza Libânio. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Rosa dos Tempos, 2018. [ Links ]

INOCÊNCIO, L. May the memes be with you: uma análise das teorias dos memes digitais. In: SIMPÓSIO DE PESQUISADORES EM CIBERCULTURA, 9., 2016. Anais [...]. São Paulo: ABCiber, 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://abciber.org.br/anaiseletronicos/wp-content/uploads/2016/trabalhos/may_the_memes_be_with_you_uma_analise_das_teorias_dos_memes_digitais_luana_ellen_de_sales_inocencio.pdf . Acesso em: 23 ago. 2021. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO FEDERAL DE MATO GROSSO DO SUL (IFMS). Projeto Pedagógico de Curso: Informática. Aquidauana: IFMS, 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.ifms.edu.br/centrais-de-conteudo/documentos-institucionais/projetos-pedagogicos/projetos-pedagogicos-dos-cursos-tecnicos/projeto-pedagogico-do-curso-tecnico-em-informatica-aquidauana.pdf . Acesso em: 14 fev. 2018. [ Links ]

KLEIMAN, A. B. O estatuto disciplinar da lingüística aplicada: o traçado de um percurso, um rumo para o debate. In: SIGNORINI, I.; CAVALCANTI, M. C. (org.). Lingüística aplicada e transdiciplinaridade: questões e perspectivas. Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 1998. p. 47-70. [ Links ]

KNOBEL, M.; LANKSHEAR, C. Online memes, affinities, and cultural production. In: KNOBEL, M.; LANKSHEAR, C. (org.). A new literacies sampler. Nova York: Peter Lang, 2006. p. 199-227. [ Links ]

KRESS, G.; VAN LEEUWEN, T. Reading images: the grammar of visual design. 2. ed. Londres e Nova York: Routledge, 2006. [ Links ]

LAKOFF, R. Linguagem e lugar da mulher. In: OSTERMANN, A. C.; FONTANA, B. (org.). Linguagem, gênero, sexualidade: clássicos traduzidos. São Paulo: Parábola , 2010. p. 13-30. [ Links ]

LEONE, P. N. (Pitty). Desconstruindo Amélia. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.letras.mus.br/pitty/1524312/ . Acesso em: 13 maio 2018. [ Links ]

LINHARES, J. Marcela Temer: bela, recatada e “do lar”. Veja [online], 18 abr. 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://veja.abril.com.br/brasil/marcela-temer-bela-recatada-e-do-lar/ . Acesso em: 10 maio 2018. [ Links ]

LOURO, G. L. Pedagogias da sexualidade. In: LOURO, G. L. (org.). O corpo educado: pedagogias da sexualidade. 2. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica , 2003. p. 7-34. [ Links ]

LOURO, G. L. Gênero e sexualidade: pedagogias contemporâneas. Pro-posições, Campinas, v. 19, n. 2, p. 17-23, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73072008000200003 [ Links ]

MATOS, M. Teorias de gênero ou teorias e gênero? Se e como os estudos de gênero e feministas se transformaram em um campo novo para as ciências. Estudos Feministas, Florianópolis, v. 16, n. 2, p. 333-357, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-026X2008000200003 [ Links ]

MILEY CYRUS AND MARK RONSON ON “NOTHING BREAKS LIKE A HEART”. Elvis Duran Show. YouTube, 10 dez. 2018. 21min48s. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FI4L6vSE5hU . Acesso em: 8 maio 2019. [ Links ]

MILNER, R. M. The world made meme: discourse and identity in participatory media. Tese (Doutorado em Filosofia) - Universidade do Kansas, Kansas, 2012. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/handle/1808/10256 . Acesso em: 1º nov. 2018. [ Links ]

MISKOLCI, R. Teoria queer: um aprendizado pela diferença. 3. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica / UFOP, 2017. (Cadernos da Diversidade). [ Links ]

MOITA LOPES, L. P. Identidades fragmentadas: a construção discursiva de raça, gênero e sexualidade em sala de aula. Campinas: Mercado de Letras , 2002. [ Links ]

NARVAZ, M. G.; KOLLER, S. H. Metodologias feministas e estudos de gênero: articulando pesquisa, clínica e política. Psicologia em Estudo, v. 11, n. 3, p. 647-654, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722006000300021 [ Links ]

NELSON, C. D. A teoria queer em linguística aplicada: enigmas sobre “sair do armário” em salas de aula globalizadas. In: MOITA LOPES, L. P. (org.). Por uma linguística aplicada indisciplinar. São Paulo: Parábola , 2006. p. 215-235. [ Links ]

NEW LONDON GROUP (NLG). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: designing social futures. In: COPE, B.; KALANTZIS, M. (org.). Multiliteracies: literacy learning and the design of social futures. Nova York: Routledge, 2006. p. 9-37. [ Links ]

PINTO, R. P. A. O ponto de vista feminista. In: PINTO, R. et al. (org.). Feminismo, pluralismo e democracia. São Paulo: LTr, 2018. p. 11-15. [ Links ]

RAJAGOPALAN, K. Por uma linguística crítica: linguagem, identidade e representação. São Paulo: Parábola , 2003. [ Links ]

RECUERO, R. Redes sociais na internet. 2. ed. Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2018. [ Links ]

RIOT-SARCEY, M. Poder(es). In: HIRATA, H. et al. (org.). Dicionário crítico do feminismo. São Paulo: Editora da Unesp , 2009. p. 183-184. [ Links ]

ROJO, R. Letramentos múltiplos, escola e inclusão social. São Paulo: Parábola , 2009. [ Links ]

SABAT, R. Gênero e sexualidade para consumo. In: LOURO, G. et al. (org.). Corpo, gênero e sexualidade: um debate contemporâneo na educação. Petrópolis: Vozes , 2003. p. 149-159. [ Links ]

SAFFIOTI, H. I. B. O poder do macho. São Paulo: Moderna, 1987. [ Links ]

SIGNORINI, I. Letramentos multi-hipermidiáticos e formação de professores de língua. In: SIGNORINI, I.; FIAD, R. S. (org.). Ensino de língua: das reformas, das inquietações e dos desafios. Belo Horizonte: Editora da UFMG, 2012. p. 282-303. [ Links ]

SOUSA, R. F. Cultura do estupro: prática e incitação à violência sexual contra mulheres. Estudos Feministas, Florianópolis, v. 25, n. 1, p. 9-29, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9584.2017v25n1p9 [ Links ]

TEJÓN, J. S. L. (Quino). Tirinha Mafalda. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://myhero.com/Mafalda_lyon_france_06_ul . Acesso em: 14 maio 2018. [ Links ]

2 In order to propose answers to the second question, we also conducted a questionnaire with the students prior to the execution of the project. This questionnaire, along with the memes, guides some of the analyses of the study.

4 We consider it suggestive because there is a well-known song in Brazilian culture that describes a woman called Amélia as the ideal companion, as she does not care about herself (in the song). Therefore, nowadays, in Brazil, Amélia has become synonymous with submissive and resigned.

5 Translation: “Mom! What future do you see for this movement of women’s liberation? Oh, never mind. Forget it.”

6 Although the images are presented in shades of gray, we will mention the original colors during the analyses whenever they are significant for the understanding of the issues being focused.

7 An IT course student’s answer registered in Google forms. The spreadsheet automatically generated by the tool with the answers and the participants’ data - name, class and answers - are part of the researchers’ personal collection.

Received: May 12, 2019; Accepted: February 02, 2021

texto em

texto em