Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Brasileira de Educação

Print version ISSN 1413-2478On-line version ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.27 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub Feb 25, 2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782022270019

ARTICLE

Indigenous inclusion in higher education: guarani and institutional perspectives

ISecretaria de Estado de Educação do Estado do Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, MT, Brazil.

IIUniversidade Estadual de Maringá, Maringá, PR, Brazil.

This article aims to highlight some elements for the understanding of the contemporary processes of indigenous educational inclusion through the analysis of the meeting between institutional perspectives and perspectives of Guarani university students. This reflection is the result of an ethnographic work with official documents, particularly those mobilized in the realization of the Vestibular of the Indigenous Peoples in Paraná, and guarani experiences in the Universidade Estadual de Maringá, between the years 2014 and 2016. The central argument explores the contrast between forms of recognition and identification that relate, without erasing their specificities. While the comparison between state reification logics and the Guarani multiplicity is pursued, the text reveals points of contact through which partial alliances are pursued, sought by both parties, which present themselves as perspectives that dialogue, conflict and operate modes to know irreducibly different.

KEYWORDS indigenous education; Guarani; university; inclusion

Este artigo busca destacar alguns elementos para o entendimento dos contemporâneos processos de inclusão educacional indígena por meio da análise do encontro entre perspectivas institucionais e perspectivas de estudantes universitários Guarani. Tal reflexão é fruto de um trabalho etnográfico com documentos oficiais, particularmente aqueles mobilizados na realização do Vestibular dos Povos Indígenas no Paraná, e vivências guarani na Universidade Estadual de Maringá, entre os anos de 2014 e 2016. O argumento central explora o contraste entre formas de reconhecimento e de identificação que se relacionam, sem apagar suas especificidades. Ao mesmo tempo em que se persegue a comparação entre lógicas estatais de reificação e a multiplicidade guarani, o texto revela pontos de contato através dos quais são efetuadas alianças parciais, buscadas por ambas as partes, que se apresentam como perspectivas que dialogam, conflitam e operam modos de conhecer irredutivelmente diferentes.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE educação indígena; Guarani; universidade; inclusão

Este artículo busca destacar elementos para el entendimiento de los procesos contemporáneos de inclusión educacional indígena a través del análisis del encuentro entre perspectivas institucionales y de estudiantes universitarios Guaraní. Esta reflexión es fruto de un trabajo etnográfico con documentos oficiales, particularmente aquellos movilizados en el Vestibular de los Pueblos Indígenas en Paraná, y vivencias guaraní en la Universidad Estadual de Maringá, entre los años 2014 y 2016. El argumento central explora el contraste entre formas de reconocimiento y de identificación que se relacionan, sin borrar sus especificidades. Al mismo tiempo que se persigue la comparación entre las lógicas estatales de reificación y la multiplicidad guaraní, el texto revela puntos de contacto por medio de los cuales se efectúan alianzas parciales, buscadas por ambas partes, que se presentan como perspectivas que dialogan, contradicen y operan modos de conocer irreductiblemente diferentes.

PALABRAS CLAVE educación indígena; Guaraní; universidad; inclusión

The relativising effect of multiple perspectives will make everything seem partial; the recurrence of similar propositions and bits of information will make everything seem connected.

Marilyn Strathern, 1990, p. xx.

On the night of March 9th, 2018, in the city of Maringá, 2017 undergraduates from the Universidade Estadual de Maringá (UEM) celebrated their graduation with a joint ceremony. At the time, 712 undergraduates from 24 different courses received their graduate degrees. Amidst the newly graduated crowd and their traditional caps, a person stood out in the ceremony’s visual frame by wearing a kangwaa, Guarani for “thing to be worn on the head”; known to the non-indigenous as cocar (headdress). That undergraduate was a Guarani who would receive his pedagogy diploma. His relatives watched him in the audience, but one of them wore an even bigger kangwaa - the cacique (village chief) of the Indigenous Land Pinhalzinho (Terra Indígena Pinhalzinho), in Tomazina, Paraná. The event publicly marked the contact of the academic form, part of an institutional and state practice, and the Guarani perspective.

UEM is one of the important places to think about the indigenous presence in the municipality of Maringá. Though the municipality lacks any villages or Indigenous Lands, there is an expressive presence of indigenous people who live or pass through the city. Many of the Guarani and Kaingang who live in the municipality are UEM students who took the Entrance Exam for the Indigenous Peoples in Paraná; a selection process aimed at opening supplementary vacancies for indigenous students in the state’s eight public universities. This circumstance configures a complex of relations made of the contact between the contemporary organizational methods of Brazil’s inclusive education (Carniel, 2018a) and the multiple indigenous experiences with universities’ institutional apparatuses. Nonetheless, how can we understand this gathering of such diverse people and perspectives? Would inclusion be the appropriate term? How do indigenous peoples relate to practices and policies meant to be inclusive? What happens when our intercultural aspirations for the admission of indigenous people finally realize themselves?

From an ethnographic research done with Guarani students from Maringá (Costa, 2016) and the documents which constitute the Entrance Exam for the Indigenous Peoples in Paraná, this study aimed to reflect upon this affirmative action and some of the ways the indigenous presence at UEM has been perceived, organized, and experienced, especially between 2015 and 2016. The idea is to draw a comparison that would produce partial connections (Strathern, 1990) between state perspectives - comprised of documents, laws, agreements, and the different institutional sectors constituting the inclusion and accessibility policies of indigenous people in universities - and Guarani perspectives constituted with and through the university experience. Through this comparison, we hope to contribute to the debate on the multiple, controversial meanings of universities’ practices and policies which aim to diversify the subjects, knowledge, ways of knowing, and worlds to be known.

DIFFERENCE AS FORM: ON UNIVERSITY REIFICATION

The state of Paraná was one of the first Brazilian states to regulate state laws aimed at including indigenous peoples in undergraduate courses. The selection process has taken place annually since 2002; its first edition was hosted at Universidade Estadual do Centro-Oeste (UNICENTRO). The result of a state-wide affirmative action, the entrance exam is regulated by State Law no. 13.134/2001, which “reserves three vacancies [per institution] to be disputed via entrance exams for state universities, among indigenous people who are members of indigenous societies in Paraná” (Paraná, 2001). In 2006, the policy was updated by State Law no. 14.995/2006, which increased the number of vacancies in each entrance exam to six1.

Each year, the Entrance Exam for the Indigenous Peoples in Paraná takes place in a different university, which is responsible for its organization alongside the Commission University for Indigenous Peoples (Comissão Universidade para Índios - CUIA). According to joint resolution no. 006/2007, CUIA is composed of up to three members from each of Paraná’s universities (appointed by their respective deans); has a permanent and interinstitutional character; and “the goal of enabling members of indigenous communities to access, remain, and complete undergraduate courses at public universities in the state of Paraná” (Paraná, 2007). According to this document, the formal requirements for CUIA members are: experience in intercultural education; teaching, research, and extension with indigenous or traditional populations; and commitment to inclusion policies. Each university also has a group of professors from different areas of knowledge that make up the so-called local CUIA.

Despite the state’s pioneering spirit in proposing affirmative policies geared toward indigenous populations; some authors, such as Paulino (2008), and Amaral (2010), emphasize that the implementation of these policies happened without due inquiry and participation of indigenous peoples and academic staff. Which is, however, unreflective of the indigenous demand for university admission. On the contrary, according to its organizers, the entrance exam’s 17th edition, for example, had 725 approved registrations (cf. UEM, 2017a).

The selection process consists of different stages and documents. Our study will have as its starting point the 2017 Candidate Handbook (UEM, 2017b) - the institutional form most valued by those responsible for the entrance exam that reached the hands of indigenous peoples of the state that year. This document will lead us to other documents, such as the registration form (UEM, 2017c), the letter of recommendation/self-declaration (UEM, 2017d), and the socioeducational questionnaire (UEM, 2017e). Thus, our research is guided by the perspective in which the anthropologist’s fieldwork is to follow his interlocutors, be they people or documents.

One of the most striking aspects of the candidate handbook is its cover image. The graphic design is a key point; authored by a non-indigenous student at UEM’s visual arts course and made in low poly2, it shows an indigenous face (Figure 1). This image was also used in the advertising poster for the XVII Entrance Exam for the Indigenous Peoples in Paraná.

Universidade Estadual de Maringá; XVII Entrance Exam for the Indigenous Peoples in Paraná; Candidate handbook. Source: UEM (2017b).

Figure 1 - Candidate handbook cover.

It would be difficult, and perhaps even naïve, to claim that indigenous peoples would simply not recognize themselves in that image, making it, therefore, a mere ethnocentric fiction. On the one hand, it seems evident that the typical representational forms, with which modern design frames universities’ institutional communication, tend to create stereotyped figures of “the different”, externalizing the indigenous from the power articulations that reify colonial differences. On the other hand, upon receiving the handbook, many Guarani to whom we quickly talked to realized the place they occupy in this State game of educational inclusion policies - they are the other. After all, as José, a Kaingang student, observed during a 2017 UEM Social Sciences class: “We are not the ones who need interculturality; you are. We already know how you think. To be multicultural, you are the ones who need to know how we think”.

This relation between the institutional form, and the Guarani and Kaingang perspectives is radicalized when we survey the material. On the very first pages we find a “Letter from indigenous students to candidates” (UEM, 2017b, p. 4). The contents of this letter refer to a reception by UEM’s indigenous students to the entrance exam candidates. The Portuguese version, shown in Figure 2, is followed by versions in Kaingang and Guarani, the two most spoken indigenous languages in the state.

A particular aesthetic to the writing of the document is readily apparent. The narrative employs an apparently indigenous form throughout the handbook elaborated by the universities. However, in a brief reading of the document (UEM, 2017b), one may observe a series of linguistic imperatives, such as “the candidate must” (p. 7-8, 12, 38), “the candidate will only be able to” (p. 7), “will not be granted” (p. 7), “will be eliminated from the selection process or will have his registration cancelled” (p. 7), “will not be allowed” (p. 8), among other variations. These imperatives are not exclusive to the Entrance Exam for the Indigenous Peoples in Paraná, for they are common in many state selection processes, and mirror the official grammar - abstract, bureaucratic, classificatory, individualized, selective, and universalist - through which educational systems usually confer different meanings to their inclusive aspirations (Carniel, 2013).

However, even though the Entrance Exam for the Indigenous Peoples in Paraná’s handbook does not tell us much about the specificity of this affirmative action, it seems to suggest something about the image of the state, assuming in the document a restricted and objectified form. From it, indigenous students of different municipalities are organized and subjected to the selection process. The test consists of two stages, divided across two days3. The first stage is the oral test, which, according to the handbook,

[...] will evaluate, after the reading of a proposed text, the candidate’s ability to talk about a given topic, interpret, and give an opinion on the positions and arguments present in the text, so as to relate the text with others which compose the oral tradition or other reading experiences. (UEM, 2017b, p. 39, our emphasis)

It can be seen in the construction of this stage, the appreciation of the orality as a characteristic common to indigenous peoples. The Handbook still states that “before argumentation begins, among other criteria, the bank will talk to the candidate about their educational trajectory and life story. This will not, however, interfere in the grade attributed to the candidate” (UEM, 2017b, p. 39).

The importance of language over grammar also appears in the second stage, composed of an essay, and an objective test (portuguese - text analysis, foreign language [english or spanish] or indigenous language [Guarani or Kaingang], biology, physics, geography, history, mathematics, and chemistry). Among the specific contents evaluated in the Portuguese section of the objective test are: differences between writing and orality; language and its situational uses; linguistic varieties. Other aspects of the test are also striking; the biology section, for example, includes biodiversity, genetic heritage, biopiracy, public policies on the health of indigenous people, and environmental legislation. These themes, in one way or another, have their specificity and proximity to the debates associated with indigenous populations both nationally and internationally (cf. Carneiro da Cunha, 1999, 2009; Soares, 2010; Teixeira and Dias da Silva, 2018).

However, despite this appreciation for orality and linguistic variety, the essay emphasizes portuguese grammar. One of the essay’s evaluated criteria is “the ability to write about a certain theme within the required textual typology, while obeying the standard use of the language” (UEM, 2017b, p. 39). In case of a tie in general ranking, the first two tiebreaking criteria value the Portuguese language: “a) higher score in Portuguese - Essay; b) higher score in Portuguese - Textual Analysis” (UEM, 2017b, p. 38).

As previously stated, the handbook takes us to other documents, such as the registration form, the letter of recommendation/self-declaration, and the socio-educational questionnaire. The documents listed have distinct purposes and produce several questions about spoken language, habitation, and ties to indigenous communities. We emphasize, however, one aspect pervading several of these documents; i.e., ethnicity and belonging to an indigenous community (UEM, 2017b, 2017c, 2017d, 2017e).

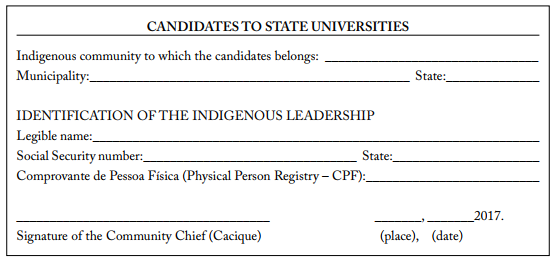

In the registration form (UEM, 2017c, p. 1), a single-page document, the candidate needs to fill a gap with “the ethnicity to which they belong” and indicate whether they “belong to an indigenous community in Paraná” or “to an indigenous community in another state of the Brazilian territory”. In the letter of recommendation/self-declaration (UEM, 2017d, p. 1), also only one-page long, it is necessary to write again your “ethnicity”, sign a term declaring “that I belong to an indigenous ethnicity” and, if they are to apply for state universities, the indigenous leadership’s (cacique) signature endorsing the “indigenous community to which the candidate belongs” (Figure 3). The socioeducational questionnaire (UEM, 2017e, p. 1) contains questions such as “What is your father’s indigenous ethnicity?” and “What is your mother’s indigenous ethnicity?”.

These three documents emphasize a need to belong to a community and fit into an ethnicity. Making visible, then, the objectification of the category ethnicity so that the candidate must be either one thing or the other. This identification process renders these categories intelligible, and the selection devices activated by identity policies, legitimate (Carniel, 2018b). Among the Guarani, this state/institutional form of endorsing this category produces a series of interesting contrasts, shown in the following topic.

THE FORM OF DIFFERENCE: ON THE GUARANI MULTIPLICITY

Based on fieldwork carried out with UEM Guarani students between 2014 and 20164, ethnicity is a repeatedly activated category, surrounded by controversies. Indigenous ethnology has a certain convention: the Guarani living in northern Paraná are linked to a Nhandewa subgroup. The classification is inspired, above all, by the division established by Schaden (1974) of three Guarani subgroups that supposedly inhabit the Brazilian territory: the Ñandéva, the Mbüa, and the Kayová. This division has been widely reproduced in the ethnological literature and by institutions such as the UEM5.

This conventional triad of Brazilian Guarani subgroups is so widespread in indigenous ethnology, that there would not be room in this study for a bibliographic review of the works reproducing Schaden’s classification. However, it is symptomatic that recent research has been problematizing this tripartition, or, at least, pointing to its precariousness. According to Assis and Garlet (2004), there is no consensus on how Guarani peoples are classified, given the doubt in classifying them into subgroups, ethnicities, or partialities. There are also attempts to avoid reified, bounding categories such as tribe, ethnicity, and society. One example is the notion of Guarani networks, proposed by Macedo (2009), to think the connections between people and meanings in an open relational tessitura. In this study, it was the Guarani who pointed to the insufficiency of the conventional classification model.

From documents such as those needed to take the Entrance Exam for the Indigenous Peoples in Paraná, the Guarani are encouraged to belong to an ethnic group and mobilize an ethnonym. In the municipality of Maringá, Nhandewa is what is formally expected. In everyday relationships, no UEM Guarani student approaches a researcher and readily states: “I am Nhandewa” or “I am Guarani Nhandewa”. They simply say, “I am Guarani”. Since this was an important question, it was explored with our interlocutors; most of them ended up reaching the Nhandewa category and recognizing themselves as such. However, the category was mobilized differently from the institutional logic. Some of the interlocutors gave answers very similar to Schaden’s. They spoke of those three subgroups and linked themselves to the Nhandewa. Others pointed to more complex paths, talking about other modes of self-designation, such as Awa Guarani and Paraguay Guarani.

During our field research, Marlene6, a student of Portuguese and English, says her father - the txamõi (a specialist in Guarani spirituality7) in the IL Pinhalzinho - is Kaiowa, and her mother, Mbya. Therefore, following her paternal lineage, she considers herself Kaiowa - although she knows the Nhandewa language better. In her sister Laura’s version, a self-designated Nhandewa pedagogy student, their father is a Paraguay Guarani, and her mother, Kaiowa. For Laura, though her father is a Paraguay Guarani, he thoroughly regards himself as a Nhandewa, for he lives in a Nhandewa-majority village. Henrique, another brother living in Maringá, also considers himself Nhandewa.

Rodrigo, a law student, not only recognizes himself as a Nhandewa, but also as a Tupi. When asked whether he used the designation frequently, his response was, “Yes, always, Guarani Tupi, Tupi Nhandewa...”. He goes on to explain that Tupi is the linguistic branch8 - a theme to which will be approached later in this text. His wife, Eliane, a Portuguese student, bring notions of purity and mixing to her reflection. She says that nowadays there is a great mix of Nhandewa with other Guarani and whites (non-indigenous). In this sense, she claims to be difficult to define who is a pure Nhandewa. The notion of purity, for her, is associated to someone whose both parents relate to the same form of self-designation.

From Luís’ point of view, a law student, and Rodrigo and Eliane’s nephew, purity seems like an unattainable ideal. Son of a Kaingang father and a Guarani mother, he is recognized by other indigenous people and institutions as a Guarani. When asked whether he belonged to the Guarani or the Kaingang, he laughs and answers:

At that point a new idea was created; of a new ethnicity, in this case, the Kainguari [laughing]. But only a few people say that, so... But, again,… when people ask “Which are you? Are you Kaingang or Guarani?”, I don’t limit myself; I don’t specify just one. I’ll say, “I’m indigenous”, and that is that. If some comes up to me saying “Yes, but this is a scientific paper. To which do you belong?”, then I’ll say “Fine, I belong to... Guarani or Kaingang”, because my mother is Guarani. But I’m never like “Well, I’m Guarani, I’m Kaingang”. I just say, “I’m indigenous...”. (our emphasis)

When asked about his use of, or if it was common to hear in the villages, the term Kainguari, he states: “No, this is an idea my mom had, and it kinda stuck in the reserves. A Kaingang marries a Guarani, and we’ll say, ‘out of it will come a Kainguari’. It’s sorta present in the reserves, but the idea is new”. Luís compares this new ethnicity, or new idea, to the Tereguá, a mixture of Terena with Guarani, common in the Tereguá village in the IL Araribá (Avaí/SP)9. Luís’ answers are interesting when thinking about the creative way, open to transformations, self-designations are mobilized among the Guarani: “an idea my mom had...”. Within Maringá’s institutional context, Luís feels safe in recognizing himself as an indigenous man - a category already conventionalized in the relations with whites. The Kaingang and Guarani ancestry leaves Luís in a context of ambiguity and wide openness for creation, such as the idea of a Kainguari ethnicity. But since this is a new, completely unconventional idea, Luis does not publicly adhere to it easily and assuredly. He talks about it practically joking.

Though Luís enunciates the mixing without any issues; “if it is for a scientific paper”, as we highlighted in his answer, he eventually associates with one of the classifications. We must remind ourselves that “scientific papers” are connected to institutions, universities, and other research bodies. The Entrance Exam’s documents, by emphasizing the category ethnicity, push candidates - though they have the freedom to fill the questionnaire with an unconventional category like Kainguari - to a stabilization of self-designations in data and statistics. While among the Guarani, this dynamic happens in a much more open and relational way.

Thus, the self-designation of the Guarani in terms of a fixed category emerges, overall, in relation to the institutional logic. In these moments, Luís leaves aside the mixing explanation and evokes the category Guarani (Nhandewa). Let us see how this arises when he is asked about the differences among the Guarani. He says:

Let’s take the example of a tree. There is the Guarani proper, the Tupi-Guarani, and that is the trunk; where the branches come from, in this case. From this Tupi-Guarani trunk come the Guarani Nhandewa - that’s us -, come the Kaiowa... there’s like, three more... (our emphasis)

By recognizing himself as a Nhandewa, Luís evokes the classic image, disseminated by ethnology and several organizations, of the Tupi languages10 - also used by Rodrigo, as we have seen. Note that when he says that “there is the Guarani proper, the Tupi-Guarani”, he does not refer to himself, but to a reified abstraction.

This logic is, in Luís’, and also in Deleuze’s and Guattari’s thought (1995), arborescent, requiring a unity (a trunk) from which differences derive (branches). Strathern (1990) also discusses this way of thinking. She identifies two recurring images in ethnographic studies: maps and genealogies (trees). Maps contain regions, sub-regions, and divisions that, in different proportion scales, distinguish different domains (continents, countries, cities, neighborhoods, streets, etc.). In genealogical diagrams, like linguistic branches, domains (class, order, family, species, dialect, etc.) are chained into a scheme of descendancy and derivations. In both cases, the connection between one domain and the other is disproportionate, as they assume that one domain encompasses the other, thus having different complexity magnitudes. This logic, pointed out by Strathern, appears in Guarani ethnology as the idea that there is a Guarani whole composed of parts, subgroups or partialities, descendant of this whole (in Brazil, Nhandewa, Kaiowa, and Mbya).

Especially on ethnonyms, Calavia Sáez (2013, p. 7) refers to this genealogical model as an obsolete way of classifying peoples, since today’s approaches would value the attention to interpersonal bonds, co-resident parenting, indigenous peoples’ own memory, self-designation, among others that better appreciate the “indigenous ideologies of sociality”. The Guarani, however, mobilize different self-designations and ethnonyms in different relationships. When Luís activates the arborescent logic to explain Guarani ethnonyms, he does not commit to this line of thinking, but evidences that this is the language set by the institutions. They are stabilization points in which the Guarani dialogue within a continuous process of production of multiplicity.

When we delve deeper into how the Guarani think of their affiliations and self-designation use, we realize that, despite activating a genealogical classification logic in certain situations, it fails to suffice. Pedro, a nursing student, for example, offers the notion that a self-designation has less to do with ascendancy/descendancy (genealogies), and more with relationships. Pedro claims that the place of birth and habitation is what defines a Nhandewa. If someone is born and lives in a village where the collective utterance is Nhandewa, as in IL Pinhalzinho, for example, then, the common self-designation is Nhandewa. Pedro’s parents are Guarani, but he also has Kaingang and Terena relatives. But, since he was born and has always lived in Guarani villages, that is what he calls himself. The issue is not the village as geographical location (a mapped domain), but a set of relations, a form of sociality from which self-designation emerges.

Viveiros de Castro (1996) draws our attention to how our interlocutors’ uttered self-designations differ from the logic of ethnonym production. The author states that:

[...] indigenous categories of collective identity have that enormous contextual variability characteristic of pronouns, which contrasts, since the immediate Ego’s kinship to all humans, or even, all beings endowed with consciousness; its coagulation as “ethnonym” seems to be, to a large extent, an artifact produced in the context of interaction with the ethnographer. Nor is it by chance that most Amerindian ethnonyms described in the literature are not self-designations, but names (often pejorative) conferred by other peoples: ethnonymic objectification primarily reflects others, not the subject. Ethnonyms are names for third parties, belong to the category of, “they”, not to the category of “we”. (Viveiros de Castro, 1996, p. 125-126)

In this sense, it is in this logic of naming the other that the classifications made by the ethnological literature on the Guarani are understood here - especially after the division proposed by Schaden (1974) - by organizations and sectors of the State.

Throughout the text, we engendered the term Guarani without complements, as this is how our interlocutors call themselves in day-to-day relationships. But what about the Nhandewa category? Would it be just a reified ethnonym? Not necessarily. Our interlocutors studying in Maringá are Guarani, but they also associate with other forms of self-designation. Most are also Nhandewa. Marlene activates the Kaiowa category, even though she has a greater knowledge of the Nhandewa language. Luís also considers himself Kaingang and Kainguari. Rodrigo also recognizes himself as a Tupi, even though he knows the term to refer to a linguistic branch. Activating a self-designation does not concern an original and immutable belonging, but to partial connections in a relational complex constantly in the making. This variation in self-designations does not mean that this research’s interlocutors do not know who they are, but that the multiplicity of who they are is not stabilized in reified categories.

We highlight three aspects of ethnonym and self-denomination mobilization by the UEM students; our research’s interlocutors. First, institutions tend to look for self-denomination stabilization, which, according to Viveiros de Castros (1996), would produce ethnonyms. Second, Guarani self-denominations are relational, and concern a sociality characterized by multiplicity and openness to new possibilities, distancing them from ethnonym stabilization. Finally, the way the Guarani deal with self-denominations also involves the dialogue and activation of the institutional and state forms of ethnonym mobilization, especially when in contact with these organizations. Thus, the institutional logic is another relational possibility in the Guarani perspective.

Therefore, it is not simply a question of opposing Guarani sociality and the institutions’ modus operandi, but to highlight that the Guarani and the organizations follow distinct times and tendencies. The Guarani lean toward the constant production of multiplicities, while the institutions tend toward the production of reified knowledge. However, the former also reify, as in the mobilization of arborescent modes of defining ethnonyms in certain situations; while the latter also update their categories, even if it takes them a little longer. In this scenario, researchers, as interlocutors of indigenous populations and agents of research institutions, indicate that NGOs, state sectors, and other organizations permeated by technical-bureaucratic knowledge (Morawska Vianna, 2014) are also multiple in that they are open to change.

If we understand the State as Herzfeld suggests (2008, p. 20), “[...] an unstable complex of people and functions”, the figure of researchers as members of institutions can be understood as a position of dialogue concomitant with the time of the multiplicity of interlocutors, and the time of reification characteristic of institutions. If, on the one hand, the Guarani dialogue with the organizations’ knowledge and logic; on the other hand, organizations also dialogue with the multiple. For this reason, it seems important to highlight the work of CUIA teachers in the position of mediation and dialogue between the logic of the State and the indigenous perspectives.

PARTIAL REFLECTIONS

In her famous book on exchange relations and gender in Melanesia, Strathern (2006) distinguishes two types of objectification: reification and personification. Her reflections focus on how people and things are constructed, and the difference between these two modes of objectification concerns especially that which these relationships make visible. In reification, common to Western thought and the market economy model, what appears are restricted forms, things. In turn, personification, common to Melanesian thought, makes visible the relationships themselves. This is not to say that these two modes do not coexist; on the contrary, the author is inspired by Wagner’s ideas (2012) on the relationship between convention and invention, which are associated by analogy, respectively, with reification and personification. As in Wagner, these two terms imply each other. What matters, therefore, is how relationships take shape and become visible.

By placing such reflections in relation to the State and Guarani perspectives presented in this text, it is pertinent to ask the following question: What relationships do such perspectives make visible? At first, we could claim that Strathern’s West-Melanesia contrast (reification-personification) offers an analog image to the Guarani-State contrast (reification-multiplicity) shown here. However, beyond this contrasting connection between ways of knowing, the path pointed out by the Guarani and the state documents shown here is also a dialogical connection between perspectives, which does not erase their specificities. Not only is the contrast between state reification and Guarani multiplicity visible; but also the points of contact and dialogue that occur in specific and different ways.

In the State perspective, some institutional agents, such as the local CUIA, present an opening for dialogue that enables microdestabilizations. Among the Guarani, dialogue with reification is one of the infinitesimal possibilities that characterize the multiple. Partial alliances are made, sought by both parties, which present themselves as perspectives that contrast, conflict and operate irreducibly different ways of knowing.

What do these ways of knowing - not only different, but radically distinct in their conceptions of being and conceiving the world - teach us about educational inclusion? Appreciation of the indigenous presence in public universities in the state of Paraná certainly has the potential to produce political-epistemological displacements and produce fissures in the westernizing forms by which we relate to what is different (Kawakami, 2019). However, it also seems necessary to understand in depth the extent to which these presences, and their own ways of relating to the institutional universe of Brazilian higher education effectively affect the organization of university structures and their conventional processes of human formation.

In this way, we return to one of our initial questions: what happens when our intercultural aspirations for the admission of indigenous people are finally fulfilled? There are no unique and definitive answers, but taking the Guarani experience seriously may enable us to think that our longings must also be destabilized, so that we may open ourselves to multiple, possible becomings within the university.

REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, L. Os Tupi Guarani de Barão de Antonina (SP): a busca pela “Terra Boa” e os processos de regularização fundiária. In: DANAGA, A.; PEGGION, E. (orgs.). Povos indígenas em São Paulo: novos olhares. São Carlos: EdUFSCar, 2016. p. 155-171. [ Links ]

ALMEIDA, N. P. Diversidade na universidade: o BID e as políticas educacionais de inclusão étnico-racial no Brasil. 2008. 153 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Antropologia Social) - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2008. [ Links ]

AMARAL, W. R. As trajetórias dos estudantes indígenas nas universidades estaduais do Paraná: sujeitos e pertencimentos. 2010. 585 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, 2010. [ Links ]

ASSIS, V.; GARLET, I. J. Análise sobre as populações Guarani contemporâneas: demografia, espacialidades e questões fundiárias. Revista de Índias, Madri, v. 64, n. 230, p. 35-54, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/revindias.2004.i230.409 [ Links ]

BARROSO, M. M.; SOUZA LIMA, A. C. Povos indígenas e universidade no Brasil: contextos e perspectivas, 2004-2008. Rio de Janeiro: E-papers, 2013. [ Links ]

BARROSO-HOFFMANN, M.; SOUZA LIMA, A. C. Desafios para uma educação superior para os povos indígenas no Brasil: políticas públicas de ação afirmativa e direitos culturais diferenciados. Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional, 2007. [ Links ]

BEVILAQUA, C. B. O primeiro vestibular indígena na UFPR. Campos, Curitiba, v. 5, n. 2, p. 181-185, 2004. http://dx.doi.org/10.5380/cam.v5i2.1627 [ Links ]

CAJUEIRO, R. Os povos indígenas em instituições de ensino superior públicas federais e estaduais do Brasil: levantamento provisório de ações afirmativas e de licenciaturas interculturais. Rio de Janeiro: Trilhas de Conhecimento, 2007. [ Links ]

CALAVIA SÁEZ, O. Nomes, pronomes e categorias: repensando os “subgrupos” numa etnologia pós-social. Antropologia em Primeira Mão, Florianópolis, n. 138, p. 5-17, 2013. [ Links ]

CARNEIRO DA CUNHA, M. Populações tradicionais e a Convenção da Diversidade Biológica. Estudos Avançados, São Paulo, v. 13, n. 36, p. 147-163, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-40141999000200008 [ Links ]

CARNEIRO DA CUNHA, M. Cultura com aspas e outros ensaios. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2009. [ Links ]

CARNIEL, F. A invenção (pedagógica) da surdez: sobre a gestão estatal da educação especial na primeira década do século XXI. 2013. 273 p. Tese (Doutorado em Sociologia Política) - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, 2013. [ Links ]

CARNIEL, F. Agenciar palavras, fabricar sujeitos: sentidos da educação inclusiva no Paraná. Horizontes Antropológicos, Porto Alegre, v. 24, n. 50, p. 83-116, 2018a. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-71832018000100004 [ Links ]

CARNIEL, F. A reviravolta discursiva da Libras na educação superior. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 23, e230027, 2018b. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782018230027 [ Links ]

COELHO, M. Terena e Guarani na Reserva Indígena de Araribá: um estudo etnográfico da aldeia Tereguá. 2016. 162 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Antropologia Social) - Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, 2016. [ Links ]

COSTA, S. D. F. Nos caminhos da cultura e dos dons: os Guarani e instituições no norte do Paraná. 2016. 225 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Antropologia Social) - Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, 2016. [ Links ]

DANAGA, A. Os Tupi, os Mbya e os outros: um estudo etnográfico da Aldeia Renascer - Ywity Guaçu. 2012. 133 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Antropologia Social) - Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, 2012. [ Links ]

DANAGA, A. Nomes e relações: a noção de mistura entre famílias Tupi Guarani do litoral paulista. In: DANAGA, A.; PEGGION, E. (orgs.). Povos indígenas em São Paulo: novos olhares. São Carlos: EdUFSCar , 2016. p. 227-247. [ Links ]

DELEUZE, G.; GUATTARI, F. Mil platôs: capitalismo e esquizofrenia 2. São Paulo: Editora 34, 1995. vol. 1 [1. ed. 1980]. [ Links ]

DIAS DA SILVA, C.; TEIXEIRA, C. Antropologia e saúde indígena: mapeando marcos de reflexão e interfaces de ação. Anuário Antropológico, Brasília, v. 38, n. 1, p. 35-57, fev. 2018. https://doi.org/10.4000/aa.374 [ Links ]

HERZFELD, M. Intimidade cultural: poética social no Estado-nação. Lisboa: Edições 70, 2008. [1. ed. 1997]. [ Links ]

KAWAKAMI, É. A. Currículo, ruídos e contestações: os povos indígenas na universidade. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 24, e240006, 2019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782019240006 [ Links ]

MACEDO, V. Nexos da diferença: cultura e afecção em uma aldeia guarani na Serra do Mar. 2009. 331 p. Tese (Doutorado em Antropologia Social) - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2009. [ Links ]

MAINARDI, C. Entre as redes das famílias Tupi Guarani: ensaio sobre as categorias étnicas. In: DANAGA, A.; PEGGION, E. (orgs.). Povos indígenas em São Paulo: novos olhares. São Carlos: EdUFSCar , 2016. p. 269-282. [ Links ]

MAINARDI, C.; DANAGA, A.; ALMEIDA, L. Um nome que faz diferença. Reflexões com famílias tupi guarani. In: GALLOIS, D.; MACEDO, V. (orgs.). Nas Redes Guarani: um encontro de saberes, traduções e transformações. São Paulo: Hedra, 2018. p. 321-338. [ Links ]

MORAWSKA VIANNA, C. Enleios da tarrafa: etnografia de uma relação transnacional entre ONGs. São Carlos: EdUFSCar , 2014. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Lei n. 13.134, de 18 de abril de 2001. Reserva 3 (três) vagas para serem disputadas entre os índios integrantes das sociedades indígenas paranaenses, nos vestibulares das universidades estaduais. Diário Oficial do Estado do Paraná (Executivo), n. 5969, Curitiba, 19 abr. 2001. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Lei n. 14.995, de 9 janeiro de 2006. Dá nova redação ao art. 1º, da Lei n. 13.134/2001 (reserva de vagas para indígenas nas Universidades Estaduais). Diário Oficial do Estado do Paraná (Executivo), n. 7140, Curitiba, 9 jan. 2006. [ Links ]

PARANÁ. Resolução conjunta SETI n. 006, de 26 de junho de 2007. CUIA - Resolução Conjunta SETI/UEL/UEM/UEPG/UNIOESTE/UNICENTRO/UNESPAR/UENP/UFPR. Diário Oficial do Estado do Paraná (Executivo), n. 7500, Curitiba, 26 jun. 2007. [ Links ]

PAULINO, M. Povos indígenas e ações afirmativas: o caso do Paraná. 2008. 162 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, 2008. [ Links ]

SCHADEN, E. Aspectos fundamentais da cultura Guarani. São Paulo: Edusp, 1974 [1. ed. 1954]. [ Links ]

SOARES, D. Conselho de Gestão do Patrimônio Genético: hibridismo, tradução e agência compósita. In: LIMA, E.; COELHO DE SOUZA, M. (org.). Conhecimento e cultura: práticas de transformação no mundo indígena. Brasília: Athalaia, 2010. p. 35-61. [ Links ]

SOUZA LIMA, A. C. Educação superior para indígenas no Brasil: sobre cotas e algo mais. In: BRANDÃO, A. A. (org.). Cotas raciais no Brasil: a primeira avaliação. Rio de Janeiro: DP&A, 2007. p. 253-279. [ Links ]

STRATHERN, M. Partial connections. Lanham: University of Press of America, 1990. [ Links ]

STRATHERN, M. O gênero da dádiva: problemas com as mulheres e problemas com a sociedade na Melanésia. Campinas: Editora da UNICAMP, 2006 [1. ed. 1988]. [ Links ]

UEM - Universidade Estadual de Maringá. Edital n. 031/2017-CVU. XVII Vestibular dos Povos Indígenas no Paraná. Maringá: UEM/CUIA, 2017a. [ Links ]

UEM - Universidade Estadual de Maringá. Manual do candidato. XVII Vestibular dos Povos Indígenas no Paraná. Maringá: UEM/CUIA , 2017b. [ Links ]

UEM - Universidade Estadual de Maringá. Ficha de inscrição. XVII Vestibular dos Povos Indígenas no Paraná. Maringá: UEM/CUIA , 2017c. [ Links ]

UEM - Universidade Estadual de Maringá. Carta de recomendação/autodeclaração. XVII Vestibular dos Povos Indígenas no Paraná. Maringá: UEM/CUIA , 2017d. [ Links ]

UEM - Universidade Estadual de Maringá. Questionário socioeducacional. XVII Vestibular dos Povos Indígenas no Paraná. Maringá: UEM/CUIA , 2017e. [ Links ]

UFPR - Universidade Federal do Paraná. Termo de convênio 502/2004. Termo de convênio, que entre si celebram a Universidade Federal do Paraná e o estado do Paraná pela Secretaria de Estado da Ciências, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior. Curitiba: UFPR/SETI, 2004. [ Links ]

VIVEIROS DE CASTRO, E. Os pronomes cosmológicos e o perspectivismo ameríndio. Mana, Rio de Janeiro, v. 2, n. 2, p. 115-144, 1996. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-93131996000200005 [ Links ]

WAGNER, R. A invenção da cultura. São Paulo: Cosac Naify , 2012 [1. ed. 1975]. [ Links ]

1Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR) began reserving vacancies for indigenous students only in 2004. It was through an agreement with the State Secretariat of Science, Technology and Higher Education of Paraná (Secretaria de Estado de Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior do Paraná - SETI) - Term of Agreement no. 502/2004 (UFPR, 2004) - that that institution became an option for those taking the Entrance Exam for the Indigenous Peoples in Paraná. The differences between federal and state universities are linked to a broader framework of debates regarding indigenous higher education nationally (cf. Souza Lima, 2007; Barroso-Hoffman and Souza Lima, 2007; Cajueiro, 2007; Almeida, 2008; Barroso and Souza Lima, 2013). For a report on UFPR’s first Entrance Exam with vacancies reserved for indigenous students, and its specificities in relation to Paraná’s policies, see Bevilaqua (2004).

3 An important piece of information is that the test does not necessarily take place in the city hosting the Entrance Exam. In 2017, the test took place in the municipality of Pinhão and accommodation and food are offered to the candidates.

4 This field research includes a short pre-field period in 2014, and a long research throughout 2015 and early 2016. The fruits of this research, which are partially brought and revisited in this topic, are found in Costa (2016).

5 Another institution deserving of attention in these relations with indigenous students in Maringá is the Indigenist Association Maringá (Associação Indigenista Maringá - ASSINDI). An indigenist non-governmental organization (NGO) run by non-indigenous people which offers, among other actions, temporary housing to UEM’s indigenous students. For more information on ASSINDI and reflections on the Guarani relations with the institution, see Costa (2016).

7Guarani spirituality is the way our interlocutors refer to the practices involving celestial beings and entities invisible to ordinary eyes. In the ethnological bibliography, these practices are commonly called shamanism. We use, however, in this study, our interlocutors’ name for them.

8 The difference in how Rodrigo mobilizes the Tupi category and the ethnonym Tupi Guarani is ever more present in research done in the state of São Paulo. Rodrigo refers to Tupi-Guarani (the linguistic branch) as a possible mode of self-designation and, as Mainardi (2016), Almeida (2016), Danaga (2012, 2016), and Mainardi, Almeida and Danaga (2018) show, the ethnonym Tupi Guarani (without the hyphen) does not refer to that linguistic branch, but to a condition of “mixing”.

9 Marcio Coelho (2016) conducted a study on the emergence of the term Tereguá among the Guarani and Terena in the IL Araribá. According to the author, the category does not refer to a new “ethnicity” or “society”, but to a particular sociality resultant from the “mixing” between the Guarani and Terena in that locality.

10 According to the Socioenvironmental Institute (Instituto Socioambiental’s - ISA) website, within the Tupi linguistic branch, Tupi-Guarani appears as a family, Guarani as a language, and the Nhandéva as dialect, referring to terms used by Schaden (1974), and some of my interlocutors to talk of the differences between the Guarani.

Funding: This study was partially funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo - FAPESP) - process n. 2014/13320-6. The translation of the article into English was financed by the Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES) - Financial Code 1.

Received: November 16, 2020; Accepted: April 26, 2021

text in

text in