Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1413-2478versão On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.27 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub 27-Abr-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782022270026

ARTICLE

The government changes, do the policies change too? The case of the national special education policy

IUniversidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Policy change events generates conflicts due to the change in the status quo and the dispute over the allocation of resources. This paper analyzes the attempt to change the Special Education policy, after the government changes that occurred between 2016 and 2019 in Brazil. For this, a categorical analysis of contend is made in documents produced during the review of the National Special Education Policy from the Perspective of Inclusive Education (Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva). It was found that the proposed amendment promotes the discontinuity of school inclusion by reorganizing the responsibilities of the family, the State and the market in schooling and specialized educational assistance; resuming the Special Education model as a modality outside the regular education system; encouraging the training of professionals to work in specialized institutions; and by basing the learning assessment on standardized goals and objectives for disability.

KEYWORDS public policies; special education; inclusive education; disability

Mudanças em políticas públicas são acontecimentos que geram conflitos em virtude da alteração do status quo e da disputa pela alocação de recursos. Este trabalho analisa a tentativa de mudança da política nacional de educação especial, após as mudanças de governo ocorridas entre 2016 e 2019 no Brasil. Para isso, fez-se análise categorial de conteúdo em documentos produzidos ao longo da revisão da Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva. Averiguou-se que a proposta de alteração promove a descontinuidade da inclusão escolar ao reorganizar as responsabilidades da família, do Estado e do mercado na escolarização e no atendimento educacional especializado; retomar o modelo de educação especial como modalidade alheia ao sistema de ensino regular; estimular a formação de profissionais para atuação em instituições especializadas; e fundamentar a avaliação de aprendizagem em metas e objetivos padronizados por deficiência.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE políticas públicas; Educação Especial; educação inclusiva; deficiência

Los cambios en las políticas públicas son eventos que generan conflictos por el cambio en el status quo y la disputa por la asignación de recursos. Este trabajo analiza un intento de cambiar la política nacional de Educación Especial, luego de los cambios de gobierno ocurridos entre 2016 y 2019 en Brasil. Para ello, se realiza un análisis categórico de contenido en documentos completos a lo largo de la revisión de la Política Nacional de Educación Especial desde la Perspectiva de la Educación Inclusiva (Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva). Se constató que la enmienda propuesta promueve la discontinuidad de la inclusión escolar al reorganizar las responsabilidades de la familia, el Estado y el mercado en la escolarización y la asistencia educativa especializada; retomar el modelo de Educación Especial como modalidad fuera del sistema educativo regular; fomentar la formación de profesionales para trabajar en instituciones especializadas; y basar la evaluación del aprendizaje en metas y objetivos estandarizados por discapacidad.

PALABRAS CLAVE políticas públicas; educación especial; educación inclusiva; discapacidad

INTRODUCTION

In 2016, Brazil underwent an impeachment process that provoked profound changes in the country’s structure of government and public policy agenda. In the special education sector, this was expressed in changes in the profile of the actors involved in the administration of national policy, which allowed the entry of new ideas and issues. Thus, a movement began to alter the National Special Education Policy from the Perspective of Inclusionary Education of 2008 (Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva - PNEEPEI) (Brasil, 2007a).

Considering this context, we understand that changes in government create opportunities for actors, ideas, and new issues to access the agenda, thus, driving policy transformation (Capella, 2015; Cairney and Jones, 2016). To explore this idea, the objective of this article was to analyze recent movements for change in Brazil’s national special education policy agenda, which were substantiated in proposals for modifications in elements of the design of PNEEPEI.

Studies of the history of Special Education indicate that, over the years, certain actors had prominent roles in Brazilian policy implementation. Specialized, private, religious, and charitable institutions were responsible for attending to people with disabilities from the time of Imperial Brazil until 1994, when the first national special education policy was launched. That first period of educational services was marked by the segregation of individuals with disabilities in special schools organized into etiologies of disabilities, consolidating the so-called “specialized and institutionalized pedagogy” (Manzini, 2018, p. 4) with a focus on rehabilitation (Kassar, Rebelo and Oliveira, 2019). In that context, access to regular school was restricted to those who demonstrated learning conditions considered to be normal (Brasil, 1994).

Beginning in 2003, the State deepened its involvement with special education in a systematic and coordinated way, by implementing a series of government programs1 that incorporated the ideas of educational inclusion, which were already circulating internationally. This shift in responsibility and the progressive centralization of responsibility in the State culminated in the enactment of PNEEPEI in 2008. Silva, Souza and Faleiro (2018) affirm that, between 2008 and 2016, there was stability in the implementation of PNEEPEI, in the form of “forceful actions, [...] material programs that sought to realize [...] a group of initiatives [...] necessary for educational systems, in line with the ‘inclusionary focus’” (Silva, Souza and Faleiro, 2018, p. 8). However, this situation changed significantly from 2016 onward and instability began to characterize the period until 2019.

The first changes to PNEEPEI in an institutional context were revealed in the changes of administrators, still in 2016, in the Secretariat for Continuing Education, Literacy, Diversity and Inclusion (Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização, Diversidade e Inclusão - SECADI) and in the Board for Special Education Policies. In 2017, the Ministry of Education promoted open bids to hire consultants to debate the Special Education Policy Guidelines (Kassar, Rebelo and Oliveira, 2019). Actors linked to specialized institutions had a central role in the arenas for debate created in this process (Baptista, 2019; Kassar, Rebelo and Oliveira, 2019). In 2018, as a result of the discussions held within the scope of the Commission to Review the Guidelines of the National Special Education Policy, a proposition to alter PNEEPEI was released in the form of a draft “National Special Education Policy: Equitable, Inclusionary, and Lifelong” (Brasil, 2018a).

This document returns to the model that offers exclusive places in special institutions, schools, or classes for people with disabilities, indicating a distancing from the directives of PNEEPEI. In addition to the proposals for altering the design of the policy, the observed context reinforces the arguments that “continuity as well as rupture are features present in Brazilian special education” (Baptista, 2019, p. 3). As such, a proposal for change in the content and context in which it is presented, “goes much further than clashes between issues: ‘for or against inclusion’; ‘for or against special schools’; ‘inclusionary education or special education’” (Kassar, Rebelo and Oliveira, 2019, p. 14), but represents a challenge to the constitutional principle of universal access for students to regular schools, and that the State is responsible for guaranteeing this right, as is internationally recognized.

Due to its social impact, it is pertinent to analyze the process of change in national special education policy. In other words, it is accepted that public policies express and operationalize ideas and values in relation to the groups they affect, influencing their access to social goods and opportunities. In the case in question, the paradigms that support the Special Education policy indicate, produce, and reproduce the social role of the beneficiaries by defining their schooling conditions, and, consequently, the conditions and quality of life.

In this sense, the elements of the design of Special Education policy that were the focus of intense debate and proposals for change were analyzed here. This was conducted by using a comparison between PNEEPEI and the proposed “National Special Education Policy: Equitable, Inclusionary and Lifelong”. After identifying the central themes, an analysis was conducted on the types of changes that occurred, based on categories proposed by the analytical model of endogenous changes.

The article has five parts, in addition to this introduction and the conclusion. The first part presents theories in the field of public policy that point to the change in government as one of the causes of the change in policy. The second addresses the methodological procedures adopted. The third and fourth parts describe the design of the policies based upon the categories outlined. The last part analyzes the types of change that occurred in each dimension of policy change.

EXPLAINING THE CAUSALITY OF THE CHANGES

Policy change studies are part of the epistemic community of the so-called Public Field and their purpose is to produce knowledge about the causes of policy change. One of its hypotheses is that change in institutional properties, and their consequent endogenous alterations, contribute to the change in image and content of a specific sectoral policy. Along these lines, this study adopted the methodological contributions offered by the model for analyzing endogenous changes in policies and institutions.

The model proposes tools to investigate, on the one hand, institutional change occurring at critical junctures in situations of political emergency and rupture, and on the other, institutional change caused by the presence of veto players and by the discretionality of the agents (Mahoney and Goertz, 2006; Mahoney and Thelen, 2009; Heijden and Kuhlmann, 2017). This article considers the first proposition, that is, it begins with a change in a political context to analyze change in public policy.

The model elaborates a set of propositions that link particular modes of incremental change to features of the institutional context and properties of institutions themselves that permit or invite specific kinds of change strategies and change agents. (Mahoney and Thelen, 2009, p. 22)

In addition to these premises, we also use the definition of institution proposed by Mahoney and Thelen (2009): institutions are distributive instruments that imply a dispute over power and resources. Thus, by altering the institutional properties, the allocation of resources between actors and the results of public policy disputes are also changed. This means that institutional change winds up defining “winners” and “losers” that form coalitions and establish equilibrium in decision making. In this way, the basic existing properties within each institution are, in themselves, possibilities for change (Mahoney and Thelen, 2009, p. 32).

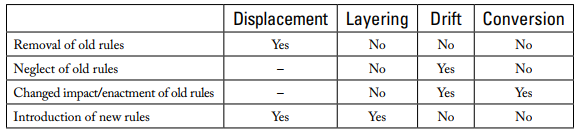

To explain the relation between political context and changes in institutions, Mahoney and Thelen (2009) elaborated a typology of changes in public policy taking into consideration the fundamental points of institutional transformation. This analysis incorporated this proposal to classify the results of institutional changes on the types of proposals for changing the content of national special education policy (Figure 1).

There are four types of change: displacement - the policy underwent not only a removal of its old rules, but also, the introduction of new ones; layering - new rules are introduced with the same or greater importance than the previously existing policy rules, that is, even if the old and new rules can coexist, the act of introducing a new rule causes it to completely assume or share the importance previously conceded exclusively to the former; drift - indicates that a policy change altered the impact of the existing rules due to a change in the institutional environment itself; and conversion - indicates that there was a strategic change in the way the existing rules came to be applied and interpreted.

METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURES

The analysis of the content of the proposals to alter the Brazilian national special education policy is guided by three questions: what are the characteristics of the institutional context in which the change is being debated (actors and administrative structure)? What is the product of this context (content proposal)? Considering the current validity of an implementation model for the schooling of people with disabilities, what are the points opposing it?

The methodological procedures were organized in a qualitative, exploratory, and non-experimental design, comprised of the content analysis method and by techniques for documentary and categorical analysis. The content analysis method offers explicit avenues for textual analysis for purposes of social research (Bardin, 1977; Bauer, 2002) and, therefore, was organized into three phases: pre-analysis; exploration of material; and treatment of results, inference, and interpretation. The NVIVO 12 qualitative data analysis software was used as a support tool for the application of the techniques.

The following documents were chosen in pre-analysis to serve as sources for composing the database: PNEEPEI); the work agenda (in the form of a slideshow - Brasil, 2018c) used in the first meeting to debate the policy change, held in April 2018; the transcripts of the debate in the Chamber of Deputies and the public hearing entitled “Special Education, Models and Perspectives”, both held in 2018; and lastly, the “draft” of a proposed alteration to PNEEPEI, submitted for public consultation and entitled the “National Special Education Policy: Equitable, Inclusionary and Lifelong” (Brasil, 2018a).

The timeframe of analysis was divided into two periods. The first covers the beginning of the enactment of PNEEPEI, in 2008 until 2016, when the first changes took place in the management of Special Education, in the Secretariat of Special Education, Diversity and Inclusion and in the Directorate of Special Education Policies, which had been stable up until then (Kassar, 2014). The second period began in 2016 and extended to the end of data collection in 20192.

In the phase for exploring the material, content was systematized into categories of analysis. For this operation, the strategy employed was an analysis of word frequency in the documents, which indicates the probability of influence of a given content over an event and, additionally, winds up revealing the content that was most debated (Bauer, 2002). As a result of the exploration of the material, the following five categories of analysis were structured, namely:

schooling: involves the proposed model for operationalization of schooling, that is, it delimits the design of education and the standard of quality. It also designates the actors responsible for its implementation (the State, specialized institutions, and families);

modality of Special Education: refers to forms of understanding Special Education. The interest is in investigating whether it is considered a modality transversal to all stages of regular education, from elementary to higher education, or a modality separate from regular education policy;

professionals: refers to the attributions and guidelines for the education of professionals involved with the education of people with disabilities; support professionals, classroom teachers, clinical professionals, resource room monitors, school administrators, among others);

specialized educational services (SES, in portuguese: atendimento educacional especializado - AEE): concerns the means of implementing policy, addressing express determinations about the locus of the SES (regular school, clinic or special institution) and of the other services destined for students with disabilities;

evaluation of learning: indicates the parameters used to evaluate learning, in general, of students with disabilities;

In the last phase of content analysis, an analysis was conducted of the proposed policy change as compared to the prevailing PNEEPEI. To support a systemization of the changes, we used the typologies of policy change developed by Mahoney and Thelen (2009), explained above. Although in both periods the political context is incorporated as a factor in the analysis, it is understood to be a starting supposition for the main objective: to examine the content produced in this context. In this way, the analysis carries the expectation of producing objective inferences from a focal text for its social context in an objective manner and also incorporating the content as “the representation and expression of a writing community” (Bauer, 2002, p. 4).

INCLUSIONARY EDUCATION: AN ONGOING POLICY

In studies about Special Education policy, it is understood that there is an interdependence between the implementation of the Inclusionary Education Program: Right to Diversity (Brasil, 2003) and the formulation of PNEEPEI. The goal of the Inclusionary Education Program was to consolidate an educational system that would integrate people with disabilities into its public via the incorporation of an “inclusionary perspective” in the formulation and implementation of actions for school inclusion (Kassar, 2011; Kuhnen, 2017; Caiado, Jesus and Baptista, 2018; Kassar, Rebelo and Oliveira, 2019). In the concept of inclusionary education, the educational system must guarantee access, permanence, and quality education to each student, regardless of ethnicity, gender, age, disability, social context, or any other condition.

To consolidate this system, the program designated hub municipalities in each Brazilian region, defining them as multipliers, and implemented two main actions. Thematic seminars were held with public administrators and teachers about education, human rights, values and concepts linked to disability, inclusionary legal benchmarks, and other themes involving special education, to achieve the goals of raising awareness and forming an “inclusionary concept” to be used as a foundation in educational systems. Secondly, multipurpose resource rooms were implemented, as a result of the “Program to Implant Resource Rooms”: environments offering specific didactic and pedagogical equipment and materials for specialized educational services for all people with special educational needs, not only those with disabilities (Kassar, 2014).

After four years implementing the Inclusionary Education Program and expanding its activities beyond the hub municipalities, the Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação - MEC) issued Ministerial Ordinance no. 555/2007 (Brasil, 2007b), which created the work group responsible for presenting the proposal that would become the foundation for the current Special Education policy. The group was composed of Special Education administrators and researchers who were significantly involved in the production of knowledge within the field of Special Education. Some of these actors also attended the series of social inclusion workshops and training sessions in the Brazilian municipalities (Baptista, 2019).

The document, officially released in 2008, entitled “National Special Education Policy from the Perspective of Inclusionary Education” (Brasil, 2007a) made it mandatory to offer a position to people with disabilities at all stages of Brazilian basic and higher education. The policy determined that the State had primary responsibility for ensuring disabled people access to the right to education.

The total number of disabled students enrolled in specialized institutions and special classes in 2007 was higher than those enrolled in regular educational institutions - 341,000 and 304,000 respectively - based on educational indexes provided in a school census by National Institute of Studies and Educational Researches (Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira - INEP). In 2008, this changed: enrollments in specialized institutions or special education classes dropped to 315,000, while those in regular schools rose to 374,000. Census data for 2018 revealed that of a total of 1,066,446 students with disabilities enrolled, 896,000 were in regular schools, while 169,000 were in specialized education institutions or exclusive classes (INEP, 2007, 2008, 2018).

Another important characteristic was the incorporation of the provisions of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Convenção sobre os Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência, 2006), which later became a regulation approved with the status of a Brazilian constitutional amendment (Brasil, 2009). The convention prescribes the inclusion of the Social Model of Disability in the formulation and implementation of policies and “[reaffirms] the universality, indivisibility, interdependence and interrelation of all fundamental human rights and liberties” and guarantees “that all persons with disabilities can fully exercise them, without discrimination” (Brasil, 2009, p. 1).

Thus, the design of PNEEPEI is based on the inclusionary paradigm. At this point, it is appropriate to verify how this system of ideas manifests itself in policy instruments. This will be done here by analyzing the central elements of the policy design using the five categories outlined.

The first category concerns the proposal for operationalization of the schooling of people with disabilities. Through it, we identified a learning design based on a confrontation of discriminatory practices. The text states that:

In recognizing that the difficulties faced in educational systems reveal the need to confront discriminatory practices and create alternatives to overcome them, inclusionary education assumes a central position in the debate about contemporary society and the role of schools in overcoming the logic of exclusion. (Brasil, 2008, p. 14)

Thus, the guideline related to schooling is the determination of inclusionary education as the pedagogical design for school, while it configures it as a central agent in overcoming the exclusionary logic.

From the perspective of inclusionary education, Special Education constitutes a pedagogical proposal of schools, defining its target public as students with disabilities, global development disorders and elevated abilities (giftedness). In these and other cases, that involve specific functional disorders, Special Education acts in an articulated way with regular teaching, gearing it toward serving the special educational needs of these students. (Brasil, 2008, p. 15)

The document then indicates that the operationalization of schooling is the responsibility of educational systems and makes no reference to a standard of quality that guides the services. The role of families in educational design is mentioned only superficially.

It is up to teaching systems to organize special education using an inclusionary educational approach, providing the functions of instructor, sign language translator-interpreter and interpreter-guide, as well as monitor or caretaker of students needing support in hygiene, feeding, locomotion, and other activities in everyday school life that require constant assistance. (Brasil, 2008, p. 17)

In summary, the schooling proposal of the 2008 national special education policy presents an educational design that assigns the responsibility for schooling people with disabilities to the regular educational system.

The specification modality of Special Education as a “modality transversal to all levels, stages and modalities” (Brasil, 2008, p. 16) suggests that the implementation should be articulated with the national education policy. The incorporation of the text of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Convenção Internacional sobre os Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência, 2006) indicates that the policy “[recognizes] the importance of accessibility to the physical, social, economic and cultural means, to healthcare, education, and to information and communication” as well as “the fact that […] people with disabilities continue to encounter barriers to their participation as equal members of society, and violations of their human rights”, recommending that “all educational systems - public and private - and all modalities and stages of education offer disabled people access to schooling” (Brasil, 2009, p. 2).

Regarding the professionals involved with Special Education, the policy defines the attributions according to their role in implementation, highlighting the agents of implementation who are in direct contact with beneficiaries: common regular education teachers, those in the resource rooms and in SES centers. In terms of their training, there is emphasis on guidelines specifically aimed at teachers, indicating that “[they] must have as a foundation of their initial and continued education, general knowledge for the exercise of teaching and specific knowledge of the field” (Brasil, 2008, p. 17). It also reaffirms the need for pedagogical knowledge that guarantees the possibility of offering interdisciplinary schooling. Although the document refers to education, its designations are generic, and it does not specify the field or guidelines for continuing education.

This training enables their work in specialized educational service and should enhance the interactive and interdisciplinary nature of their performance providing special education services and resources in common regular educational classrooms, in the resource rooms, in specialized educational service centers, in accessibility centers in higher education institutions, in hospital classrooms and in home environments […] Considering knowledge of inclusionary educational system administration, in order to develop projects in partnership with other architectural fields. (Brasil, 2008, p. 17-18)

This signifies that professionals working in SES should also have training in the implementation of inclusionary educational systems. Their work would take place via services that contemplate the target public of Special Education with the goal of providing “curricular enrichment, instruction in language and specific codes of communication and signing, technical help, assistive technology, etc.” (Brasil, 2008, p. 16). Among these attributes, those pertinent to specific expertise in teaching, translation, and interpretation of sign language, Portuguese language, Braille and Soroban are emphasized. Highlighted among them, are: the focus on mobility and autonomy of studies, incentives for alternative forms of communication in the school environment, the production and adaptation of didactic and pedagogical materials, and the use of assistive technology resources.

Regarding specialized educational service, all the guidelines proposed by the PNEEPEI are based on the following assumption:

It is understood that people change continuously, transforming the context in which they are inserted. This dynamism requires pedagogy aimed at altering the situation of exclusion, emphasizing the importance of heterogeneous environments that promote the learning of all students. (Brasil, 2008, p. 15)

Therefore, the SES is responsible for identifying, preparing, and organizing the “pedagogical and accessibility resources that eliminate barriers to the full participation of students, considering their specific needs (Brasil, 2008, p. 16).

[…] the activities developed in specialized educational services differ from those carried out in the common classroom and are not substitutes for schooling. This service compliments and/or supplements the education of students with a focus on autonomy and independence in and out of school. (Brasil, 2008, p. 16)

Offering bilingual education for the inclusion of deaf students, so that the teaching of sign language and Portuguese can be developed simultaneously within regular schools, is also the responsibility of SES. It is steered so that deaf students can be in regular classes with other deaf peers. Once the services are defined, it is evident that the locus of specialized educational services is the regular school. Even in cases of students with specific functional disorders, or other types of disabilities that are unrecognized in the context of inclusion, the articulation of specialized service with regular schooling is envisioned (Brasil, 2008, p. 16).

Finally, with regard to the learning assessment of students, no model or metric is presented, it is merely emphasized that, like the other categories, education must be conducted using the students as their own parameters. Another element of the 2008 policy is the absence of differentiation between the evaluation of students with disabilities and the pedagogical assessment of others.

EQUITABLE AND LIFELONG: AN INCLUSIONARY CHANGE?

The change in presidential administration and the change in actors responsible for special education in SECADI and in the Board of Special Education Policies led, in 2017, to the publishing of public bids to select specialist consultants to support the National Education Council’s Chamber of Basic Education in the process to revise the National Curriculum Guidelines for Special Education. Through the public bid, the Commission for the Review of Special Education Guidelines was formed, within the purview of the National Council of Basic Education (Kassar, Rebelo and Oliveira, 2019).

The first meeting with the revision of PNEEPEI on the agenda was attended by: Maria Amendolla (National Union of Municipal Education Administrators - União Nacional dos Dirigentes Municipais de Educação), Terezinha Assman (Instituto Benjamin Constant), João Figueiredo (National Institute of Education for the Deaf - Instituto Nacional de Educação de Surdos), Paulo Nascimento (National Council of People with Disabilities - Conselho Nacional de Pessoas com Deficiência - CONADE), Francisco Djalma (Council of Organizations of People with Disabilities - Conselho de Organizações das Pessoas com Deficiência), Ester Pacheco (Federation of Associations of People With Down Syndrome - Federação das Associações das Pessoas com Síndrome de Down), Ana Figueiredo (Brazilian Council for the Gifted - Conselho Brasileiro para Superdotação), among other representatives of the National Federation of the Association for Parents and Friends of the Exceptional (Federação Nacional das APAES - FENAPAES), Federação Nacional de Pestalozzi, and the Brazilian National Organization of the Blind of Brazil (Organização Nacional de Cegos do Brasil). As a result, the first official letter was drafted and sent to the Minister of Education, Rossieli Soares, which pointed to the change in the situation of special education since the implementation of PNEEPEI as justification for the policy revision (MEC, 2018a, p. 2).

The subsequent meeting, in August 2018, was attended by Rosita Carvalho (Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro - UFRJ), Miguel Chacon (Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho - UNESP/Marília), Antonio Silva (CONADE), José Turozi (FENAPAES), Moises Bauer (Brazilian Committee of Organizations Representative of People with Disabilities - Comitê Brasileiro de Organizações Representativas das Pessoas com Deficiência), Eugenia Gonzaga (Federal Public Ministry - Ministério Público Federal - MPF), and Lenir Santos (Brazilian Federation of Down Syndrome Associations and The National Council of Health - Federação Brasileira das Associações de Síndrome de Down e Conselho Nacional de Saúde). The goal of the second meeting was to draw up a draft proposal for a policy review to be presented to the Chamber of Deputies’ Commission for the Defense of the Rights of Disabled Persons (Comissão de Defesa dos Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência da Câmara de Deputados - CPD). On November 7th, CPD and the National Council on Education (Conselho Nacional de Educação - CNE) held a seminar to finalize the document, which would be submitted for public review (MEC, 2018b, p. 1).

After the document was completed, a short period of public review (from September to November) was held and the text was approved. When the draft was publicized, the Federal Public Ministry in Caxias do Sul filed a public civil suit to stop the federal government from publishing it before holding public debate, especially with people with disabilities and entities involved with inclusionary education. The need for action arose during the investigation related to the civil suit, which found that the Ministry of Education was on the verge of publishing the proposed “National Special Education Policy: equitable, inclusionary and lifelong” without allowing the participation of the public and interest groups in the drafting (Brasil, 2018b).

The next step in the debate was a public hearing in the federal Chamber of Deputies with the topic “Special Education Policy”, on September 26th, 2019. At the event, the Secretariat of Specialized Educational Modalities (Secretaria de Modalidades Especializadas de Educação - SEMESP) was represented by Nídia de Sá, the Director of Accessibility, Mobility, Inclusion, and Support for People with Disabilities. The rapporteur for the Special Education Guidelines Review Commission and counselor for the CNE’s Chamber of Basic Education, Suely Neves, also attended. Neves presented an overview of recent policy revisions and justified the changes based upon the observation of educational changes, new legislation, and current social demands (Câmara dos Deputados, 2019).

The last event was held in the Chamber of Deputies in November 2019 and was attended by Nídia de Sá, Rita Louzeiro (a pedagogue and activist for neurodiversity and the inclusion of autistic persons), Roseli Oller (a specialized educational service supervisor at the Instituto Jô Clemente), and Cíntia Macena (a pedagogue, psychoanalyst, and analyst of SES for people with intellectual disabilities). The models and perspectives to be adopted in the Special Education policy were debated. Director Nídia de Sá presented the “flexibility” model supported by the new Special Education policy, stating that “in this policy the space of special schools, special classes, bilingual schools, bilingual classes [are] considered as alternatives because there exists a public for every kind of class, for every kind of school”, thus, it is up to the family to choose the best place for the disabled person in accordance with their specific characteristics (Câmara dos Deputados, 2019, p. 4).

The following speech by Roseli Oller referred to the case of the former São Paulo Association for Parents and Friends of the Exceptional (Associação de Pais e Amigos dos Excepcionais - APAE), which ceased to be a special school and became a specialized support center that, not being a substitute for regular school, is offered outside of regular school hours. According to her, schools “did have to restructure themselves, teachers had to be retrained and we were there to contribute to the process of training these professionals” and “with this change in teaching it was observed that these students gained more autonomy, more independence, and their self-esteem improved a lot” (Câmara dos Deputados, 2019, p. 5). Cíntia Macena disagreed with the offer of spaces outside of regular school, and expressed her discontent in a response to Nídia de Sá:

So if you ask me, Cíntia, as a teacher, as a mother, as a researcher, I want my child in a regular school and I am not just talking about me, I am speaking of many, many families who fight for this, at least in the spaces that I frequent. So it is a demand not just of a professional, but of a mother, of families and people with disabilities themselves. Thus, we need the child to be in a regular school with the proper resources and support to guarantee their right to an education and not the removal of the right to share these spaces. (Câmara dos Deputados, 2019, p. 7)

This clash of ideas and strategies reveals the change in the institutional context of national special education policy compared to the previous period. Thus, it remains to be seen how these actors’ ideas were translated into elements of the policy proposal. The document submitted for content analysis is the draft entitled the “National Special Education Policy: Equitable, Inclusionary and Lifelong (2018)”. Its text states that the schooling model to be adopted “prioritizes actions of a permanent nature, directed throughout life, which promote excellence in education, aiming at maximum effectiveness of the norms” (Brasil, 2018, p. 26). These norms, to be put into effect, are guided “by individual and group singularities and attempt to consider the demands of the students through their own voices or those of their legal representatives” (Brasil, 2018, p. 26).

Another guideline that is essential to the operationalization of schooling is “beyond school education, valorize learning that takes place in other educational spaces and services in the community” (Brasil, 2018, p. 7). This perspective is related to guidelines for the schooling of people with disabilities in regular schools and classes, with a focus on incentives to diversify services, such as the establishment of bilingual education schools and classes, special schools and classes, special education services centers, educational services in hospital environments, centers of pedagogical support for serving people with visual disabilities, nuclei of pedagogical support and Braille production and centers for training education professionals and attending deaf people.

In relation to those responsible for the implementation, a commitment is affirmed between State, family, and society. The role of families is highlighted in various passages that emphasize their participation and responsibility for the schooling process. Item f, “The responsibility and participation of families in the school process”, illustrates this strategy:

As a factor for the promotion of learning of students, the involvement, participation, and accompaniment of the family are essential in the process of school development and it is up to the educational system and the family to guarantee this collaborative partnership. (Brasil, 2018, p. 8)

As a complement to this strategy, the administrators of educational systems assume the role of “guiding families and society about the limits of the action of school institutions that require effective partnerships with families and communities to achieve better development of students” (Brasil, 2018, p. 33), this guideline reinforces the fundamental role of the family for the success of the policy and points to the regular school as insufficient.

Another factor that exemplifies the role of families is the responsibility that they come to have for the standards for the quality of learning and for measures of curricular differentiation, given that families would be involved in actions ranging from “evaluation processes; planning; curricular development; accompaniment and school results” to “steering needs [to schools] and to the educational systems, when deemed necessary” (Brasil, 2018, p. 38-39).

In the analysis of the document, it is difficult to identify the guidelines for the Special Education Modality. Even if there is a reference to the transversality of education for all ages; the guidelines are aimed only at schooling for adults.

The services present new options for specialized educational services, coming to have other loci of implementation, which are identified in the description of services:

Nuclei for accessibility and Nuclei for Serving People with Specific Needs: are forms of specialized support offered at institutions of higher education, with services and human resources, technicians, technologies, and materials provided by specialized professionals, when required by university students who need support from Special Education.

Center for Specialized Educational Services (CAEE): a public or private space of a non-profit community, religious or philanthropic institution, with a contract with local government to provide specialized educational services.

Educational service in a hospital environment: Special Education services offered by educational systems, in articulation with the healthcare field, to hospitalized students, who are registered in a public-school network, seeking to continue their school learning and continuity.

Nuclei of Activities for those with High Abilities/Gifted (Núcleos de Atividades para Altas Habilidades/Superdotação - NAAH/S): a center dedicated to education and resources, provided to support the education of gifted students with strong abilities, through an interface with the common school, to offer curricular enrichment. (Brasil, 2018, p. 29-30)

In conjunction with the new alternatives for SES, two types of professionals will serve the beneficiaries: school support professionals, who are responsible for activities related to meals, hygiene, locomotion, social interaction, and communication, at all levels of public and private institutions; and the educational interpreter-guides, who carry out the interpretation-guiding of communication and of information for blind and deaf people. The education of professionals must have inclusionary orientation so that they are trained to act in common spaces of regular and specialized schools. Moreover, it is noted that the document defines guidelines not only for the evaluation of learning, but also for the evaluation of the need for SES, by recommending and “guiding the schools to issue medical, psychological and other reports from the health field, as a condition required for providing special education services” (Brasil, 2018, p. 33).

The evaluation of learning is guided “by individual and group singularities” (Brasil, 2018, p. 26) and will be carried out by preparing an Individual and School Development Plan (Plano de Desenvolvimento Individual e Escolar - PDIE). This is a tool to know students and identify their barriers to learning, to stipulate goals, ends, and objectives based on a standardized evaluation in accord with the typology of the deficiency. For the success of the plan, a universal design of learning based on high expectations about the possibilities of the student (Brasil, 2018, p. 34). Thus, the evaluation of learning consists in the “construction of a logical model that [...] allows the specification of a balanced set of indicators, [...] of the results expected by the public from this policy” (Brasil, 2018, p. 43).

The analysis of the content indicates that the proposal for policy changes does not promote inclusion, given that the emphasis on “flexibilization” of the requirement for school registration winds up distancing the design of the policy from the perspective of school inclusion, given that it encourages care in exclusive spaces. Moreover, both the exclusivity of the strategy to evaluate learning, as well as the reduced role for educational professionals, with an emphasis on complementary service, compromise the continuity of the inclusionary perspective in the special education policy.

INSTITUTIONAL CHANGE AND CHANGE IN THE NATIONAL POLICY FOR SPECIAL EDUCATION

In this section we analyze the characteristics of the institutional changes related to the National Policy for Special Education in the period of 2008-2019. Then, based on a change of political context, the changes of content will be classified based on typologies proposed by the analytical model of endogenous changes (Figure 1).

After a period of institutional and decision-making stability during the implementation of the PNEEPEI from 2008 to 2015, in 2016 a process began to attempt to change the National Policy for Special Education, concomitant to the emergence of a new government. Due to this institutional change, there was a change in the actors responsible for the administration of Special Education in the Ministry of Education, and in the Board for Special Education Policies. Consequently, the conduct in relation to policy changed.

The change in the dynamics among the actors led to openings in decision-making, allowing a specific group of actors to influence the definition of the content of the policy. This finding is based on the analysis of events, debates and documents produced during the process of revision of the policy, between 2016 and 2019, in which there was an expressive presence of actors who represented specialized institutions of a private nature, and philanthropic and charitable organizations.

In this sense, we classify the changes that took place in the political context as serial, given that there was a profound political change perceived as a rupture; perhaps not so much because of the characteristics of the political forces, but mainly for the way that it took place and its result: with a valorization and ascension of political antagonism. In this type of context, the result of the change in the public policy could be “continuity” or “discontinuity” of the status quo (Streeck and Thelen, 2005). In the case of the policy in focus, we found a discontinuity in that which is proposed as an “updating” or “revision” of its content.

In relation to schooling, it is seen that what has been debated as a proposal for change in policy called for the re-establishment of exclusive special classes for people with disabilities, while the current guideline guarantees that “people with disabilities not be excluded from the general education system by an allegation of disability” (Brasil, 2009, p. 11). In this way, the discontinuity of the current policy proposal takes place through a layering phenomenon: investments in exclusive classes expanded, and investment in the establishment of inclusionary educational systems decreased, thus increasing the chance of segregation in the exclusive classes or specialized institutions.

In terms of modality, the PNEEPEI imposes guidelines for transversal education to all the modalities of teaching in articulation with the national education policy. The proposals to change its content, on the other hand, promote the valorization of exclusive schooling for students with disabilities, constituting an initiative that is not articulated with regular education. In this way, we classify the character of change of the modality as drift, considering its opposition to the 2008 guidelines that guarantee “accessibility to physical, social, economic and cultural means, to health, education and to information and communication” (Brasil, 2009, p. 2).

Considering the category professionals, the most outstanding factors are related to the new attributions indicated for those responsible for the services provided to students with disabilities and their education. The PNEEPEI is not specific about the education of these professionals, however, it includes recommendations that their initial and continuing education provide specific knowledge in the field. In contrast, the 2018 proposal emphasizes that the education of these professionals should help them act not only in the context of regular schools, but also in special institutions. Thus, at the same time in which the previous guidelines are excluded, the new ones focus on the training and attributions of the professionals involved with schooling. For this reason, we classify the change in the category professionals as a drift phenomenon.

In relation to specialized educational services, we highlight the diversification and expansion of the locus of services. Although the results are presented in terms of an expansion of services, there is a layering of guidelines, because the proposal for the specialized education services changes: there is an indication that they should be offered in different spaces and no longer in regular schools in an inclusionary perspective, and that they should substitute regular schooling.

Finally, the PNEEPEI determines that the evaluation of learning be based on individual development standards, and not on a comparison with other students. In contrast, the document related to the 2018 proposals gives preferences to a universally comparable evaluation of learning, given that it mentions the creation of an Individual Development Plan. This change is categorized as a phenomenon of conversion to indicate that the creation of the plan does not exclude the previous guidelines but changes them considerably by attributing priorities to guidelines that overlap the inclusionary values of the current PNEEPEI.

Given the situation presented, the types of change in each one of the categories of content have elements of discontinuity. The institutional changes accompany the change of actors in the decision-making spheres of policy, driving proposals to change the content that provoke a rupture with the PNEEPEI guidelines. Streeck and Thelen (2005) affirm that this type of change would lead to the substitution of current guidelines.

The study of a change in policy and of institutions can help us understand certain cumulative effects of a policy in society over time, through the observation of the strength of this change in terms of social results (Streeck and Thelen, 2005; Mahoney and Thelen, 2009; Heijden and Kuhlmann, 2017). In the case observed, the social effects or “results of change” revolve around the concretization of a social right: access of people with disabilities to schooling.

CONCLUSIONS

This study proposed to demonstrate that not only the change of government, but the change of actors responsible for the change of special education was essential to unleashing a process that sought to change the national special education policy. This movement occurred in a context of institutional change, taking advantage of the window of opportunity created by this change. The political events of 2016 defined “winners” and “losers” that shaped coalitions and established equilibriums in decision making around the policy (Mahoney and Thelen, 2009). Thus, the results found show the discontinuity of the status quo, which led to a proposal for change in various elements that are central to the design of the Special Education policy. The types found were divided into two groups: one with a character of layering of guidelines, and another that indicated a drift or conversion.

In the first group, the content about schooling and about the SES involved a layering of guidelines due to the reconfiguration in the roles of the family, the State, and the market in the Special Education policy. Although families have always had a fundamental role in the schooling of people with disabilities, with their principal role being that of caregiver, their responsibility only became institutionalized in the 2018 proposal to change the policy. This proposal attributes to private specialized institutions the responsibility for SES, attributes to the students’ families the decisions about whether or not to enroll them in the regular school and thus decreases the responsibility of the state to promote inclusionary education in common educational systems.

The shift in the guidelines concerning the transversality of the modality of Special Education and about the education of the professionals in the field composes the second group of the policy change. The proposal to create exclusive classes for students with disabilities and “lifelong” schooling indicates the organization of special education as a modality parallel to regular education, as it makes no reference to transversality or to inclusion in all school spaces. Another highlight is the drift in the principles guiding the education of the professionals, expressed by the recommendation that they have specialized education to prepare them to work in private institutions. And in the second group, we can see a conversion of the principles guiding the evaluation of learning present in the proposal for guidelines for the implementation of the PDIE, based on a global development standard.

In our analysis, the attempt to change the content of the national special education policy from the Perspective of Inclusionary Education, through institutional changes determined by the national special education policy, responds to the exclusionary interests of the new administrators of special education, which emphasizes a strong role for specialized institutions. As expressed by the documents analyzed, the content proposed promotes a discontinuity of access to schooling for people with disabilities, which is troublesome, given that it makes the attainment of a human right inviable.

After examining the changes proposed for the design of public policy, it is necessary to determine the causes of these alterations in order to anticipate changes in the access to the right to education and to understand under what parameters this right will be consolidated. It is thus important to continue to study changes in the national special education policy by using other analytical models that help understand the influence of the actors in this process. As a contribution, this study provided a systematic description of the guidelines of the proposal for change and its comparison with the PNEEPEI. The study thus serves as an investigative base for discussions about the design of Special Education policy in Brazil.

REFERENCES

BAPTISTA, C. R. Política pública. Educação especial e escolarização no Brasil. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 45, e217423, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-4634201945217423 [ Links ]

BARDIN, L. Análise de conteúdo. Trad. Luís Antero Reto e Augusto Pinheiro. São Paulo: 1977. [ Links ]

BAUER, M. W. Análise de conteúdo clássica: uma revisao. In: BAUER, M. W. Pesquisa qualitativa com texto, imagem e som: um manual prático. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2002. p. 189-218. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Política Nacional de Educação Especial. Brasília, DF: MEC/SEESP, 1994. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Programa Educação Inclusiva: direito à diversidade. Brasília, DF: 2003. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva. Documento elaborado pelo grupo de trabalho nomeado pela portaria ministerial n. 555, de 5 de junho de 2007, prorrogada pela portaria n. 948, de 9 de outubro de 2007. Brasília, DF: 2007a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Portaria ministerial n. 555, de 5 de junho de 2007. Prorrogada pela portaria n. 948, de 9 de outubro de 2007. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 9 out. 2007b. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.semesp.org.br/legislacao/migrado2576/ . Acesso em: 14 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva. Brasília, DF: MEC/SEESP, 2008. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto n. 6.949, de 25 de agosto de 2009. Promulga a Convenção Internacional sobre os Direitos das Pessoas com Deficiência e seu Protocolo Facultativo, assinados em Nova York, em 30 de março de 2007. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 26 ago. 2009. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Minuta. Política Nacional de Educação Especial: equitativa, inclusiva e ao longo da vida. MEC/Comissão de Revisão das Diretrizes da Educação Especial. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2018a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério Público Federal. Procuradoria Federal dos Direitos do Cidadão. Recomendação n. 1/2018/PFDC/MPF. Brasília, DF: MPF, 2018b. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.mpf.mp.br/pfdc/atuacao/manifestacoes-pfdc/recomendacoes/recomendacao-no-1-2018-pfdc-mpf . Acesso em: 17 out. 2018. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Fotos do arquivo original (slides): apresentação PNEE - 16-04-2018 MEC. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2018c. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto n. 10.502, de 30 de setembro de 2020. Institui a Política Nacional de Educação Especial: equitativa, inclusiva e com aprendizado ao longo da vida. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 1 out. 2020, p. 1. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/decreto-n-10.502-de-30-de-setembro-de-2020-280529948 . Acesso em: 9 mar. 2022 [ Links ]

CAIADO, K. R. M.; JESUS, D. M.; BAPTISTA, C. R. Educação especial na perspectiva da educação inclusiva em diferentes municípios. Cadernos CEDES, Campinas, v. 38, n. 106, p. 261-265, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1590/cc0101-32622018199149 [ Links ]

CAIRNEY, P.; JONES, M. D. Kingdon’s multiple streams approach: what is the empirical impact of this universal theory? Policy Studies Journal, Oxford, v. 44, n. 1, p. 37-58, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12111 [ Links ]

CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS. Comissão de Direitos Humanos. Audiência pública. REQ n. 186/2019. Política de Educação Especial. 26 set. 2019. Disponível em: https://escriba.camara.leg.br/escriba-servicosweb/html/57137. Acesso em: 14 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

CÂMARA DOS DEPUTADOS. Comissão de Direitos Humanos. REQ n. 98/19. Educação Especial: modelos e perspectivas. 26 nov. 2019. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://docs.google.com/document/d/12I35yunSxYSsQxK1jQdjZXBlNw0dbxGV/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=111229148022054614631&rtpof=true&sd=true . Acesso em: 14 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

CAPELLA, A. C. N. Análise de políticas públicas: da técnica às ideias public policy analysis. Revista Agenda Política, São Carlos, v. 3, n. 2, p. 239-258, 2015. https://doi.org/10.31990/10.31990 [ Links ]

HEIJDEN, J. van der; KUHLMANN, J. Studying incremental institutional change: a systematic and critical meta-review of the literature from 2005 to 2015. Policy Studies Journal, Oxford, v. 45, n. 3, p. 535-554, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12191 [ Links ]

INEP - Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Censo escolar - 2007. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2007. [ Links ]

INEP - Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Censo escolar - 2008. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2008. [ Links ]

INEP - Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Censo escolar da educação básica - 2018. Brasília, DF: Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais, 2018. [ Links ]

KASSAR, M. C. M. Percursos da constituição de uma política brasileira de Educação Especial inclusiva. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, Bauru, v. 17, n. spe1, p. 41-58, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-65382011000400005 [ Links ]

KASSAR, M. C. M. A formação de professores para a educação inclusiva e os possíveis impactos na escolarização de alunos com deficiências. Cadernos CEDES, Campinas, v. 34, n. 93, p. 207-224, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-32622014000200005 [ Links ]

KASSAR, M. C. M.; REBELO, A. S.; OLIVEIRA, R. T. C. Embates e disputas na política nacional de Educação Especial brasileira. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 45, e217170, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201945217170 [ Links ]

KUHNEN, R. T. A concepção de deficiência na Política de Educação Especial Brasileira (1973-2016). Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, Bauru, v. 23, n. 3, p. 329-334, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-65382317000300002 [ Links ]

MAHONEY, J.; THELEN, K. Explaining institutional change: ambiguity, agency, and power. 1. ed. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009. [ Links ]

MAHONEY, J.; GOERTZ, G. A tale of two cultures: contrasting quantitative and qualitative research. Political Analysis, United Kingdom, v. 14, n. 3, p. 227-249, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpj017 [ Links ]

MANZINI, E. J. Política de Educação Especial: considerações sobre público-alvo, formação de professores e financiamento. Revista on Line de Política e Gestão Educacional, Araraquara, v. 22, n. 2, p. 810-824, 2018. https://doi.org/10.22633/rpge.unesp.v22.nesp2.dez.2018.11914 [ Links ]

MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. Política de educação especial deverá passar por atualização. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2018a. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/ultimas-noticias/202-264937351/62961-politica-de-educacao-especial-devera-passar-por-atualizacao . Acesso em: 18 fev. 2022. [ Links ]

MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO. Ministro apresenta panomara sobre educação especial e discute necessidade de atualização. Brasília, DF: MEC, 2018b. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/component/content/article?id=65721 . Acesso em: 18 fev. 2022. [ Links ]

SILVA, L. C.; SOUZA, V. A.; FALEIRO, W. Uma década da política nacional de Educação Especial na perspectiva da educação inclusiva: do ideal ao possível. Revista on Line de Política e Gestão Educacional, Araraquara, v. 22, n. esp. 2, p. 732-747, 2018. https://doi.org/10.22633/rpge.unesp.v22.nesp2.dez.2018.11906 [ Links ]

STREECK, W.; THELEN, K. Introduction: institutional change in advanced political economies. Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies, United States, p. 1-39, 2005. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/19498/ssoar-2005-streeck_et_al-introduction_institutional_change_in_advanced.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y&lnkname=ssoar-2005-streeck_et_al-introduction_institutional_change_in_advanced.pdf . Acesso em: 14 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

1 Inclusive Education and Rights to the Diversity Program (Programa Educação Inclusiva Direito à Diversidade, 2003); Multifuncional Feature Room Program (Programa Sala de Recursos Multifuncionais, 2010); Accessible School Program (Programa Escola Acessível, 2011); and Accessible School Transportation Program (Programa Transporte Escolar Acessível, 2005).

2 Although it was not the subject of this analysis, it should be noted that the following year decree no. 10.502/2020 was issued, establishing the National Policy for Special Education: Equitable, Inclusionary and Lifelong, which was suspended by the Federal Supreme Court (Superior Tribunal Federal - STF) in the same year.

Received: September 18, 2020; Accepted: May 21, 2021

texto em

texto em