Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1413-2478versão On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.27 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub 16-Jun-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782022270037

ARTICLE

Is didactic training essential for professors? The strategies applied by management professors in the classroom

IUniversidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

IIUniversidade Estadual do Piauí, Uruçuí, PI, Brazil.

The purpose of this research is to understand the professors’ role and the strategies used by Management professors for a better performance in the classroom. This is a qualitative study, based on semi-structured interviews with professors in this field. The analysis is based on the inductive method proposed by Gioia, Corley and Hamilton. It shows that postgraduate training is commonly detached from professional practice, given that its main focus is on research in detriment of professor training; on the other hand, when a professor training course is offered, professors have a better understanding of their role in the teaching-learning process. Thus, here are some of the main contributions of this study: professor training develops significant skills in teaching performance, making professors more confident in their teaching practice; the combination of professor training with learning based on practice promotes better resourcefulness in the classroom; and learning from peers was the most commonly used strategy to resolve issues in the classroom.

KEYWORDS professor training; teaching practice; strategies and classroom; management

O objetivo desta pesquisa consiste em compreender o papel da formação docente na área de administração e as estratégias utilizadas para melhor atuação em sala de aula. Trata-se de um estudo qualitativo, baseado em entrevistas semiestruturadas com professores da área. A análise dos dados foi a de conteúdo, conforme o método proposto por Gioia, Corley e Hamilton. Pela análise, observa-se que a formação na pós-graduação é comumente descolada da atuação profissional, haja vista que existe demasiado foco na pesquisa em detrimento da formação enquanto docente; por outro lado, quando há uma disciplina de formação docente, os professores compreendem melhor seu papel no processo de ensino aprendizagem. Assim, entre as principais contribuições deste estudo, destacam-se: que a formação docente desenvolve habilidades significativas para a atuação dos professores em sala de aula, tornando-os mais confiantes na prática docente; que a combinação da formação docente com as aprendizagens vivenciadas na prática permite que o professor tenha melhor desenvoltura em sala de aula; e que a aprendizagem com os pares foi a estratégia mais utilizada para resolver as questões em sala de aula.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE formação docente; prática docente; estratégias e sala de aula; administração

El propósito de esta investigación es comprender el rol del profesor y las estrategias que utilizan los profesores de gestión para un mejor desempeño en el aula. Se trata de un estudio cualitativo, basado en entrevistas semiestructuradas con profesores de gestión. El análisis se basa en el método inductivo propuesto por Gioia, Corley y Hamilton. Del análisis se observa que la formación de posgrado suele estar desvinculada de la práctica profesional, dado que el foco mayoritariamente es la investigación en detrimento de la formación docente, por otro lado, cuando existe una disciplina de formación docente, los docentes tienen una mejor comprensión de su papel en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Así, entre los principales aportes de este estudio podemos ver que: la formación docente desarrolla habilidades significativas en el desempeño docente, haciendo que los profesores tengan más confianza en la práctica docente; que la combinación de la formación docente con el aprendizaje experimentado en la práctica permite al docente tener un mayor ingenio en el aula; y, que aprender con compañeros fue la estrategia más utilizada para resolver problemas en el aula.

PALABRAS CLAVE formación del profesorado; práctica docente; estrategias y aula; administración

INTRODUCTION

Brazilian higher education has undergone changes in the last decades, marked by the creation of the National Education Guidelines and Framework Law (Brasil, 1996), which provided a significant expansion of the offer of vacancies in higher education as a result of public policies aimed at national development (Fernandes et al., 2013). The offer of vacancies led to the opening of undergraduate programs, accompanied by the expansion of postgraduate courses (Alves and Oliveira, 2014). This increased the demand for qualified professors, since the law that enabled such growth also imposed requirements in terms of quality of education, highlighting the importance of awarding higher education institutions (HEI) based on their performance in assessments (Brasil, 1996), among them professor evaluations (Rodrigues, 2012; Bisinoto and Almeida, 2017).

This scenario fostered the discussion of professor training, which has been considered essential for the improvement of quality indicators in education. The higher education professor is generally required to have knowledge of specific content (Lourenço, Lima and Narciso, 2016), but the teaching act goes beyond this type of knowledge. To be a professor, mastering a particular discipline is not enough; it is also necessary to be able to deal with situations requiring pedagogical knowledge to articulate different possibilities of action, and this requires specific training (Veiga, 2011).

This type of knowledge is lacking in several areas, including Management/Administration, the central focus of this research. As explained by Joaquim and Vilas Boas (2011) and Ferreira, Moura and Valadão Júnior (2015), training, in many cases, comes down to the teaching stage, which is characterized by little freedom of action and an absence of proper monitoring of knowledge of the process. Therefore, Management/Administration graduate students have little contact with pedagogical knowledge and techniques. This scenario has negative consequences for teaching practice, affecting the area under study (Bastos, 2007; Ferreira, Moura and Valadão Júnior, 2015) and the very subjectivity of professors working in it.

In view of these issues, this paper focuses on professor training in graduate Management/Administration programs. This topic has been little discussed in academia - Maranhão et al. (2017) found that only 0.48% of research in conducted in the field of Management/Administration is dedicated to professor training. This paper therefore aims to understand the role of professor training in the field of Management/Administration and the strategies used for a better performance in the classroom.

The results of this study contribute, in general, to interdisciplinary studies in the areas of Education and Management/Administration. This contribution can be divided into three areas. The first addresses the “multiple influences affecting professor training” (Cunha, 2013, p. 609). The second is concerned with teaching within the area of Management/Administration, an interest which needs to occupy a more privileged position so that discussion can lead to the creation of training programs and policies. The third area seeks to understanding and problematize professor training in the field of Management/Administration in order to have a wider take on the teaching profession, thereby drawing attention to the complexity of the theme, pointing out directions and avoiding the large personal and social investments made in training professors being lost due to lack of preparation and dissatisfaction, which can result in abandonment of the profession.

HIGHER EDUCATION TEACHER TRAINING IN BRAZIL

Education, in its general sense, has social and economic relevance, in that it contributes to place individuals in both society and the market, leading to the circulation of wealth and operating as a vector for human development (Justen and Gurgel, 2015; Maranhão et al., 2017). It is not restricted to a single environment, but rather can be developed in family life, by socializing with other individuals, at work, in social practices, in teaching institutions (schools), and through social and cultural movements. As regards the institutional aspect, education and teaching can be divided into two levels: basic education and higher education (Brasil, 1996).

Higher-level education encompasses different courses and programs, such as sequential, undergraduate, graduate (specialization, master’s and doctoral programs) and extension courses (Brasil, 1996), and plays a strategic role in the Brazilian state (Nunes, 2007) to promote social mobility and economic prominence (Costa, Costa and Melo, 2011). The valorization of higher education stemmed from:

advance of capitalism (Karawejczyk and Estivalete, 2003; Justen and Gurgel, 2015; Nogueira and Oliveira, 2015);

the increased importance of productive work; and

the relevance of professional training (Justen and Gurgel, 2015).

With the expansion of public and private universities in Brazil, there has emerged a need to implement assessment systems and programs in order to guarantee quality standards in the country’s higher education. Such practices are not specific to Brazil; however, the topic is controversial and, when assessment is on the agenda, discussion of the conceptions and concepts that should guide the procedures and consequences of professor evaluations (Rodrigues, 2012) is fostered.

One of such discussions regards professor quality. This is measured not only in terms of knowledge of the contents taught in a specific course by the professor being evaluated, but also involves pedagogical issues he/she is not always trained for. Teaching skills are part of the assessment tools and place professors in defensive situations because these evaluations, especially in private HEIs, have been used to classify professors and to decide on the continuity or not of the employment agreement, rather than simply as one of the elements of the training process (Rodrigues, 2012).

As regards professor training, it is important to differentiate such education from certain pedagogical techniques. The first is more complex and encompasses aspects that are not limited to the mere reproduction of practices and knowledge produced by others, but also refer to a set of behaviors and interactions infused with intentionality that allow the trainee to overcome his own limitations (Garcia, 1995). Contact with theories and further aspects of professor training can enrich professional practice, including in arenas that go beyond pedagogical techniques and also fall into the moral and ethical spheres (Imbernón, 2011).

It can be said that, in graduate Management/Administration programs of academic nature, professor training has been neglected, as it is given most of the time only by the teaching internship. This becomes clear when we analyze the curricula of 117 graduate (master’s and doctoral) programs in Management/Administration authorized by the Brazilian Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES) (Brasil, 2021). Of these programs, 60% (70) do not have a discipline concerned with teaching besides the internship. And in these, which include a teaching internship (83), the internship is only mandatory for scholarship holders in 20% of cases. This finding is compatible with Azevedo and Cunha’s (2014) argument: that there are few initiatives for professor training, either initial or continuous, to support higher education professors in Brazil. Such conclusion was also reached by other studies, such as those by Souza-Silva and Davel (2005); Canopf et al. (2018) and Osten et al. (2019). This is a contradiction, since training at this level and for this modality of teaching presupposes professor training.

This scenario has emerged from a conception of graduate study which gives centrality to training for research rather than for teaching. This began in 1988, when CAPES changed its priority from establishing teaching/research faculty boards to assessing graduate activities in Brazil (Patrus, Shigaki and Dantas, 2018). Given the way graduate Management/Administration programs in and their assessment systems are structured in Brazil, the assumption is that content knowledge itself would be enough to qualify a good professor.

Nevertheless, research supervision and classroom teaching without grounding can result in a practice with no guarantee of satisfactory didactic-pedagogical performance (Veiga, 2014). This seems to result from what Garcia (1995) termed a “cultural myth”, that is equally assumed by novice professors: that classroom experience is the most important and indeed makes for a good professor. This gap between theory and practice is aggravated in applied social science programs because, in the context of professors’ employment opportunities, especially in the area of Management/Administration, the proficiency that comes from professional experience seems to compete on equal terms with academic degrees. Thus, as long as they comply with the minimum requirements of the Brazilian Education Law (Lei de Diretrizes e Bases - LDB), HEIs seem to favor professors who have professional experience and mastery of content, making these the primary requirements for the exercise of teaching (Valverde et al., 2007). In this way, a message is conveyed to professors that the theoretical components are important, but it is the practice, both in the classroom and in managerial/administrative jobs, that really counts.

Therefore, it can be safely stated that there are important deficiencies in the training of Management/Administration professors in Brazil (Souza-Silva and Davel, 2005; Maranhão et al., 2017), one of which has to do with assessment of their professionalism (Malusá, Pompeu and Reis, 2014). This is a challenge for both the professors themselves and the HEIs, since admitting “professionality”, according to Imbernón (2011), would mean abandoning the assumption that formal knowledge of a given subject is sufficient for the teaching-learning process. Such knowledge, although necessary, has already been deemed insufficient, since being a professor demands more than merely transmitting formal, completed knowledge. The idea of training professors includes understanding their role in society and what the act of teaching means. Roldão (2007, p. 95) argues that:

In light of the most current knowledge, it is important to advance the analysis to a level that is more integrative of the real complexity of the action in question and its profound relationship with the professional status of those who teach: the specific role of teaching can no longer be defined by the simple transmission of knowledge, not for ideological reasons or simply as pedagogical options, but for socio-historical reasons.

Thus, professor training can be understood as a complex process that has multiple determining factors. It is not a neutral or sterile practice, but is inserted in a framework in which there are tensions and contradictions (Roldão, 2007). Hagemeyer (2004) states that the role of a college professor is organized in three fields: those of scientific, technical-didactic, and human-social competence. It must be pointed out that college education is not an atheoretical practice, but, as Garcia (1995) argues, it is based on a very specific idea of man and social practice.

From a practical point of view, professor education can raise the quality of education and, therefore, is apt to be the object of public policies. Furthermore, it is seen as a means to attract students to HEIs that, based on the logic of education as a promising market, use the professor as an attractive factor to bring in students who, in this approach to teaching, are treated as customers.

From the point of view of the individual, the training given to professors can be considered, further, as a process that reveals the mode of production of society and of the individual. Aguiar and Ozella (2006) claim that human activity is always meaningful. For them, while working, man performs an internal as well as an external activity, operating in both with meaning, and language emerges as a key element of social and self-consciousness. Consciousness is then processed by the language, thoughts, and actions that a person realizes in his/her relationship with other humans. Perception of the meaning of professor training itself is the result of an elaboration of the meanings of teaching and reflects the movements present in the practices that are concretely performed by professors.

It is also worth noting that recent studies have addressed the theme of professor training and practice. One of these is by Carneiro et al. (2018), who, when evaluating the practices used in a Management/Administration program, identified during the teaching-learning process that some practices aimed to align theory and practice, while, however, being centered on traditional teaching. Our findings point to a discourse of appreciation of pedagogical training, which nonetheless is still incipient. Maranhão et al. (2017) conducted a quantitative survey of studies dealing with pedagogical education in the main Management/Administration events and journals, and found few publications on the subject; the existing ones discuss teaching practice, the importance of teacher training and the competencies involved in pedagogical practices.

Denicol Júnior et al. (2018), when surveying studies on pedagogical education in publications of the main Management/Administration events in Brazil (Teaching and Research in Management and Accounting [Encontro de Ensino e Pesquisa em Administração e Contabilidade - EnEPQ] and National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Administration [Associação Nacional de Pós-Graduação e Pesquisa em Administração -ANPAD]), observed that this type of training takes place through workshops, teaching internships and, when offered, graduate courses. Based on these results, it can be said that there is an insufficiency and/or absence of subjects dealing more deeply with the pedagogical aspects of the professor’s activity. In addition, the authors emphasize that the internship or teaching practice is a common requirement in graduate studies, but, while it is a way to make the candidate more familiar with the profession, it is not mandatory for all students, but only for those who hold a scholarship from CAPES or from the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq).

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH

Considering the nature of the proposed research problem, the qualitative approach was found to be the most appropriate for this study. Stake (2010) defines this approach as: interpretive, based on experience, situational and personal; therefore, it is understood that meanings are subjective and capable of being observed from different viewpoints. Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña (2014) explain that qualitative data have the potential to highlight complexity, whereas the qualitative approach allows the researcher to emphasize people’s experiences, that is, it seeks to understand the meanings that people give to events, processes, and structures and how they interact with the meanings of the world around them. In view of the objective of the research, which is to understand the role of professor training in the area of Management/Administration and the strategies used for a better performance in the classroom, interviews were conducted with eight professors who are also doctoral candidates in the field. They now work or have worked in public and private universities in the states of Paraná and São Paulo. Of this group of interviewees, 60% had taken a teacher training course during their graduate studies, while 40% had not.

After defining the cases, data collection was carried out through semi-structured interviews, consisting of eight interviews with doctoral students who are also Management/Administration professors. Interviews lasted an average of 25 minutes. All were transcribed later, resulting in 42 pages of material for analysis.

Examination of the data was operationalized through content analysis which, according to Saldaña (2011), is based on the systematic review of texts, images and/or videos. During analysis, the researcher makes an interpretive effort to visualize the present or latent meaning of the data. In this sense, content analysis was performed using the holistic coding method and the methodology proposed by Gioia, Corley e Hamilton (2013). The latter is widely used in high-impact research, as it ensures transparency and reliability in data management, giving the researcher flexibility in finding results. This type of content analysis is different from traditional approaches that perform a coding based on the theory. As a type of grounded theory, Saldaña (2016, p. 166) points out that when the researcher starts from holistic coding, he “understands the themes or basic issues of the data, absorbing them as a whole rather than analyzing them line by line”.

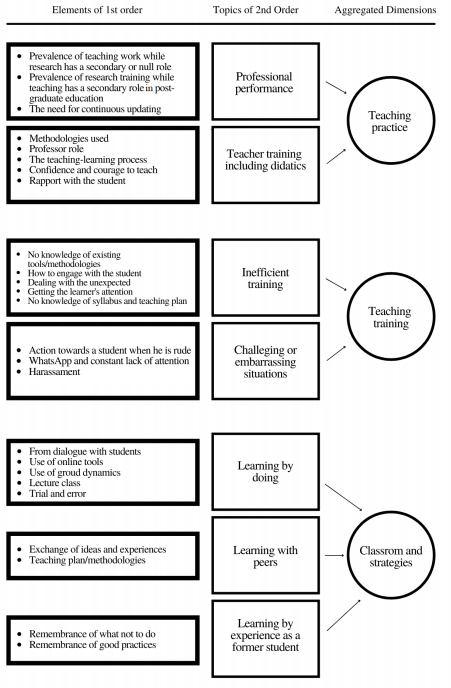

Based on the methodology of Gioia, Corley e Hamilton (2013), this research is defined as inductive, and the steps used for analysis were:

compilation of the most relevant parts of the data (first-order elements);

classification of the summary of the excerpts into second-order themes;

and, finally: finding the aggregate dimensions of analysis that guided the results and analysis section, characterized by issues related to “teacher training”, “teaching practice” and “classroom and strategies”, as exemplified in the Appendix 1.

RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

In order to reach the goal of this study and considering the interpretive nature of the investigation, it is necessary to contextualize the education pursued by Management/Administration professors.

The professional context of these professors is characterized by:

the fact that the sector is an investment field attracting groups interested in its profit potential (Locatelli, 2017);

due to the first item, the field of higher education is dominated by private institutions (INEP, 2017) which mostly do not privilege research - most studies are carried out in public HEIs (CAPES, 2018);

the expansion of e-learning programs (Arruda and Arruda, 2015);

young students that are already working in the job market; and

substandard working conditions (Santos, 2012).

Given this scenario, it is more likely that a graduate student will be hired by a private HEI, as a part-time employee, receiving remuneration per hour-class given (Souza-Silva and Davel, 2005) or per task - in the case of e-learning -, not having many research opportunities. This reality is not only a construction of private HEIs, but a decision made by previous governments in view of the State’s incapacity to deliver higher education, transferring responsibility to the private sector.

The practices adopted by a significant number of private HEIs are not considered adequate for the professor’s work and for teaching in general. Souza-Silva and Davel (2005, p. 119) claim that, when the student is considered as a source of profit, the logic of education is inverted and he begins to be viewed as a client who cannot be contradicted, which leads to, for instance, approval in academic courses without actual proficiency and prevents the formation of a “competent, critical, and reflective citizen”. This scheme, according to the authors, places the teacher as a resource in a production line. The consequence of this has been, according to Locatelli (2017, p. 79), the loss of “critical capacity and intellectual status” by the teaching profession.

This context, coupled with the complexity of the teaching activity, can affect the daily lives of teachers, a complexity that intensifies when there is no adequate training to face the challenges of a new career. This will be shown in the presentation of the results of this study.

The speech of the respondents, who are both professors and doctoral students, corroborates studies regarding the facts of Management/Administration graduates’ professional activity. This is due to the fact that in Brazil, with very few exceptions, there are no positions for researchers. Activities and recruitment are focused on teaching while research is left in the background - especially in undergraduate courses - in addition to not being considered part of the teaching process. This is exactly the opposite of what occurs with graduate training, where research is privileged, as described by Osten et al. (2019).

[...] there are often professors who only want to be researchers, but in Brazil, there are not many opportunities for that. So, he has to be a teacher too. (I1)

[...] like it or not, even if we are researchers, we are going to work as professors in the classroom. (I3)

[...] both in the master’s and doctoral degrees, 99% of our time is for research. We know very well that, when this process ends, we will be faced with a teaching career [...] which is not concerned only with research. (I6)

Although people look for a doctoral degree to pass a competitive examination, research plays a secondary role in the process. (I8)

The dichotomy between training for research and for teaching, according to Patrus, Shigali and Dantas (2018), is a consequence of CAPES’ great valorization of research and scientific publication. However, this way of viewing graduate studies does not resonate in the daily lives of graduates because, even if they perform graduate research activities, the undergraduate classroom is a reality for all of them. This is the context of professor training in Management/Administration.

Therefore, the teaching activity still seems to be centered on the reproduction of practices. Professors consider the use of peer-learning relevant, as can be seen in the following extracts:

[...] a positive feedback from the students or experiences of colleagues that we commented on, I saw that they were assertive. (I4)

You don’t know what a teaching plan is and you don’t know what a lesson plan is, and you don’t understand why there’s a mandatory reference [...] you end up learning from your colleagues. (I5)

[...] so every course assumes, from a pedagogical point of view, which I believe it is, it assumes a very well-done planning of which competences the student has to absorb [...] and I, as a professor, was never prepared for this, so I confess that, in the first term, in my first experience, I started out without adequate planning, or one that I would consider adequate, [...] so I had in my plan, the plan I had was content-based, [...] but not a broader plan in the sense that I really should have, outlining how I should really behave methodologically. (I6)

I remembered my former teachers, and I learned how to teach while working, [...] but I could handle it, in some way, like it or not, we are students and we know how we would like to be taught. (I8

Furthermore, those who have not undergone any teacher training rely even more on the experience they have had as students and on their fellow teachers. Thus, the lack of professor training at graduate level generates the need for professors to seek alternatives, as they explain:

It was a painful process, because you end up learning from your colleagues. (I5)

What really happens is that the professor, I mean.... the doctoral student ends up having to learn by doing, without any guidance, or any previous methodology learning, he ends up having to learn how to teach his class by trial and error, which happens in most cases nowadays. (I6)

This is the opposite of what was observed by Pryjma and Oliveira (2016, p. 851), who saw professors working in a solitary way, with a “lack of sharing of teaching practices with peers and the lack of support and guidance from the pedagogical team”. A possible explanation for this difference in findings may lie in the level of trust placed by professors in some of their colleagues or even in the area they are working in, which, in the above-mentioned study, was the field of exact sciences.

However, a more significant learning experience is perceived by those with some training on teaching. For those who have never had any contact with teacher education disciplines, peers seemed to be used as an emergency resource to deal with more basic activities such as the preparation of teaching plans and the understanding of operational issues. Respondents who received training, on the other hand, seemed to take better advantage of their peers for more in-depth discussions about the teaching-learning process.

[...] but we talked to exchange ideas on how to work with these groups. We worked a little more with active methodologies than lectures to attract more attention, to prompt the student to bring what he was learning at the company into the classroom and vice-versa. (I1)

None of the respondents reported the use of research as a way of producing knowledge to be addressed in the classroom - teaching with research is obliterated in favor of knowledge that is ready-made and produced “out there”, especially in the area of Management/Administration, and must be imparted to the student, who, in turn, has a passive role. For Malusá, Pompeu and Reis (2014), the current teaching pedagogical practice requires changes, and research in undergraduate education could serve as a tool to improve teaching quality and student autonomy. In addition, bringing research into the classroom can generate more significant learning, since the student will be investigating his own reality. This issue is addressed by Freire (1996), for whom teaching requires research - a production that goes beyond the transmission of knowledge.

Likewise, respondents said very little about the role of the student, who, when mentioned, is portrayed as someone who needs to be motivated or controlled. One of the challenges teachers face is the need to continuously think of strategies to create more attractive classes in order to awaken the students’ interest. In addition, two interviewees pointed out the difficulty in keeping up to date in the sense of searching for new case studies, examples, news, and reformulating the teaching plan.

A challenge like that, for me, I think is keeping up to date. [...] We adapt to the situation. (I3)

I think the biggest challenge I have in the classroom, firstly, is to make students pay attention, forget the cell phone, forget the notebook, forget the tablet [...]. (I4)

[...] the biggest challenge is WhatsApp. Because the detour of attention is massive. In the past, a professor could manage when a person was not paying attention. It was one in 30-40 students. But now, with the mechanisms of simultaneous dissemination to everyone, at any deviation of focus, heads get down. (I7)

Here, it can be speculated that lack of training makes professors adopt a position in which they are the holders of knowledge rather than facilitators of the learning process, who foster student autonomy. Their professional context can also interfere with the way professors perceive their role in the classroom. In this sense, as pointed by Souza-Silva and Davel (2005) and Locatelli (2017), private HEIs tend to treat the student as a client, and this generates tensions and contradictions since the teacher has to act as an audience leader for demanding spectators, in addition to having to take care of students’ meaningful learning - two roles often incompatible with each other. This finding corroborates the results of Osten et al. (2019), which showed that professors kept silent about the student’s role in the learning process, as if professors were solely responsible for it.

Professors, regardless of having received training or not, realize that teaching practice requires much more than content knowledge. This is compatible with the study of Hagemeyer (2004). Lack of, or incomplete, training on teaching and its conditioning factors make such situations be viewed as challenges for which professors are not properly prepared, as can be seen in the following extracts:

[...] others have the knowledge, but cannot impart it to the students. (I1)

[...] an experience in undergraduate teaching is more challenging. [...] we have to learn to take action and behave in front of people. [...] a student nearly came to blows with me during a class. This is a little complicated to deal with. (I2)

I think teaching is a challenge, I think that when we enter the classroom, we see that many things are not the way we think they are. (I3)

I suffered a lot because, when you are hired at an educational institution, you go to the classroom and you don’t know what a course syllabus is. (I5)

[...] you are going to be a professor at a public or private university, you end up being placed in different situations, a large part of your time is teaching. [...] you end up having to work with three axes: teaching, research and extension. (I6)

And then I had a little bit of a harassment problem with a student of mine who made a joke. Because I used to live in another city, she asked: “Do you want to sleep over at my place? There is only one mattress, though.” (I8)

It is observed that professor training, for instance by means of a course focusing on the pedagogical process of higher education, can benefit professors in training; still, it seems to be insufficient. Those who had received training considered that taking a specific course had made a significant difference to their teaching practice, because it was through that course that they were able to better understand the role of the professor, the limitations of his/her action, how decision-making works in the classroom and what tools to apply according to the class and subject content, as shown below:

Yes, first it [the course] gave me courage. I wouldn’t have had the courage to go head-on with the coordination if I didn’t have such a foundation, such as what is right and what is the real role of the teacher, I would have had a lot of doubt about that, because I had no knowledge at all. (I3 - received training)

A very basic reason is for me to feel more confident in the classroom, so when you understand a little more about the teaching-learning process, how you need to impart the content to the students, to understand that the classes […]. (I8 - no training)

Professors who were not prepared for teaching seemed to feel more insecure in their performance than those who had had some preparation. This result is compatible with studies by Darling-Hammond (2000), Bastos (2007) and Junges and Behrens (2015). The group that completed the professor training course reported greater easiness and skills when dealing with adverse situations in the practical field. Thus, we agree with Bastos (2007) when he states that many problems could be avoided if graduate students had previously had the opportunity to discuss the constraints of teaching practice while still in graduate school. In this sense, it is necessary to reaffirm the need for the professionalization of professors (Imbernón, 2011), especially those in Management/Administration.

There seems to be a consensus among the interviewed professors that professor training should take place as early as during the Master’s level of training. This is due to the fact that most of the Brazilian graduates work as professors:

During the master’s I think there should be. Not during the doctorate! Because during the doctorate degree, a candidate is trained to be a researcher. [...] In the Master’s, I believe, in my point of view, that teacher training should be mandatory. (I5)

Here two analyses can be made: the first is that respondents are still immersed in a context in which the two stages of training are believed not to be complementary and to have different objectives. This is not consistent with reality, since the role of the former graduate has been, regardless of the level, teaching. The other conclusion that can be reached is that respondents still consider that one subject dedicated to professor training could provide the necessary background for teaching, which shows their lack of knowledge of the complexity and extent of teaching education. Specialized literature in the area (i.e., Garcia, 1995) admits that professor education should be a continuous, systematic and organized process involving several stages and that, in initial training, a series of activities must be developed. Here, such steps and knowledge were unknown to all interviewees.

When asked about the content that should be part of the training, respondents were expected to list elements that, at some point in their practice, had been missing. Based on their answers, it is clear what types of situations were experienced which generated tensions and contradictions, as can be seen in the following extracts:

I think mainly of what tools we have available, what methodologies, the main methodologies that we have, both active, passive and those traditional ones. [...] teach [...] look at the student and at us as human beings. (I1)

Maybe didactics can help, to make us think of something more practical. (I2)

Other than the methodology curriculum, you do not have any career instruction. (I5)

[...] I think it would have to be divided into two aspects: theoretical and practical. The theorist would deal with the different epistemologies, ways of teaching, [...] possibilities, what are the possible ways of imparting knowledge. (I6)

I have no concept of methodology. [...] I think there is something more solid behind the assumptions of pedagogy that can help us, but it’s far beyond presenting typologies, the type of class, what is a flipped classroom; you work it out in practice, I think it is much more assumptions of learning, of memorization, that type of thing. (I7)

[...] it had to be almost a revamping of what it means to be a professor, really, what the professor’s role is or should be. Whether he is a knowledge or content facilitator. The one who does not know anything, I will treat as a student or as a learner - I will treat as an apprentice. In that sense of the importance of the teacher to the construction of knowledge, and also another thing, which is what we talked about, we end up coming from a teaching process based on a single model. (I8)

The answers show that a variety of factors impact the daily lives of professors, which they are not adequately trained for. The needs presented by them range from career structuring and possibilities, to theoretical aspects of the teaching-learning process, to, finally, techniques that can be used in the classroom. These are the most relevant topics, although they cannot be treated as isolated elements during a professor training course.

Another challenge pointed out by the interviewees is having to deal with students having different profiles, qualifications and financial statuses, since there are different worlds and perceptions to be considered. Here, it is important to remember that a professor deals with several demands, not just those pertaining to the classroom. He/She should not only have the necessary skills to teach a class, but must also be prepared to deal with adverse situations and different types of people. This has been observed in the study carried out by Hagemeyer (2004, p. 87), who points out that the teacher’s work is performed in three divergent fields: the scientific competence field, the technical-didactic field, and the human-social field, also related to the cultural field. For the author, the teaching profession requires the inter-relational treatment of these fields, and the teacher, “by experiencing the multiple pedagogical knowledge, develops his scientific and technical didactic competence to master the act of teaching and training”; however, “these fields of teaching action cannot ignore the human-social field and its personal and cultural contribution”.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

In summary, the results of this research show that the role of professor training lies in: preparing teachers for the challenges of the classroom, guiding them in the use of teaching methodologies and appropriate techniques according to students’ realities, furthermore, also directing them in the main perspectives of the teaching career. Understanding this role helps professors in the making to refrain from using the trial-and-error method in the classroom, applying in its place, with theoretical and practical support, mechanisms that enable them to face more successfully those adversities demanding more than the techniques and knowledge of the area of Management/Administration, thus promoting an efficient, high-quality teaching-learning process. We highlight that professor training in graduate Management/Administration programs is relevant for the initial development of knowledge that is necessary for teaching practice, in that it fosters important skills for teaching performance.

As for the strategies used by Management/Administration professors to solve problems in the classroom, we can point out: conversations with peers for more in-depth discussions about the teaching-learning process; the use of research as a form of knowledge production; understanding of the student’s role; constant updating and adoption of a facilitator behavior. Therefore, based on the aforementioned synthesis of the understanding of the role of professor training and the strategies used for problem solving, the goals of this research have been accomplished.

Our findings enable us to criticize the excessive valorization of publications that has been adopted by regulatory agencies and that leaves aside the concern with teaching education, suggesting that conducting research grants an ability to tackle the complexities of a professor’s daily life. However, it should be noted that training is a continuous process throughout the teaching career. Responsibility cannot be entirely attributed to graduate courses in Management/Administration, and professors themselves should seek continuous training throughout their careers. They can and should look for ways to acquire knowledge of didactics, teaching practice, the role of the professor in the classroom, social relationships and the context in which the professor works. This entire process helps the teacher minimize the adversities encountered in the classroom and to better deal with conflicts and career challenges.

Due to the complexity of the matters professors have to deal with, over and above technical training, it can be said that training cannot be reduced to a course subject or to practice-based learning (as in the case of internships), nor even to learning from peers. This is because the activity requires continuous and frequent training in order to consolidate and recycle knowledge of teaching.

Evidence for this can be found in the current scenario, where there is a need for flexibility and updating so professors are able to face the challenges of online and distance learning. In the face of this new reality, professors have to adapt to the lack of visual contact and physical space, and learn to deal with technological channels, methodologies and resources that are different from what they are used to. In addition, there are challenges of internet access and students’ own lack of motivation to spend too much time in front of the screen of a notebook or cell phone. Therefore, it is up to the professor to build a new way to communicate with students, to build knowledge and to understand that technological resources are only means to operationalize the teaching-learning process, for the real focus is on the people involved.

Among the main contributions of this study is the discussion of professor training and its impact on teaching practice from the viewpoint of doctoral students in Management/Administration, a discussion that is still incipient in the area and relevant, given that the Management/Administration area is currently one of the ones with the largest number of students in the country. Moreover, from the main results of this research, it was perceived that:

professor training develops significant skills for classroom teaching performance, making professors more confident in their teaching practice;

the combination of training and learning from practice allows professors to have a better classroom performance; and

learning from peers was the most used strategy to solve issues in the classroom.

As for a future research agenda, we suggest further exploring the difference found in this study with regard to peer learning. Results were contradictory to those of previous studies - is a professor’s learning process solitary or peer-assisted? And what kind of relationship is established in the latter case?

Finally, this study allows us to reflect on the role of professor training for teaching practice and the strategies used by the teacher to better perform in the classroom, since adequate training serves as a basis to develop qualified, ethical, human, and market-ready professionals. This is also because, without such training, professors tend to experience more difficulties in dealing with adverse events in the classroom and with the teacher-student relationship, making the knowledge construction process more difficult.

REFERENCES

AGUIAR, W. M. J.; OZELLA, S. Núcleos de significação como instrumento para a apreensão da constituição dos sentidos. Psicologia: Ciência e Profissão, Brasília, v. 26, n. 2, p. 222-245, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-98932006000200006 [ Links ]

ALVES, M. F.; OLIVEIRA, J. F. Pós-graduação no Brasil: do regime militar aos dias atuais. RBPAE, Porto Alegre, v. 30, n. 2, p. 351-376, 2014. https://doi.org/10.21573/vol30n22014.53680 [ Links ]

ARRUDA, E. P.; ARRUDA, D. E. P. Educação à distância no Brasil: políticas públicas e democratização do acesso ao ensino superior. Educação em Revista, Belo Horizonte, v. 31, n. 3, p. 321-338, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-4698117010 [ Links ]

AZEVEDO, M. A. R.; CUNHA, M. I. Formação para a docência no âmbito da Pós-Graduação na visão dos seus formadores. Educação Unisinos, São Leopoldo, v. 18, n. 1, p. 97-106, jan./abr. 2014. https://doi.org/10.4013/edu.2014.181.1997 [ Links ]

BASTOS, C. C. B. C. Docência, pós-graduação e a melhoria do ensino na universidade: uma relação necessária. Educere et Educare, Cascavel, v. 2, n. 4, p. 103-112, 2007. https://doi.org/10.17648/educare.v2i4.1658 [ Links ]

BISINOTO, C.; ALMEIDA, L. S. Percepções docentes sobre avaliação da qualidade do ensino na educação superior. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 25, n. 96, p. 652-674, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-40362017002501176 [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Diário Oficial da União, Brasília, DF, 23 dez. 1996. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9394.htm . Acesso em: 3 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Cursos avaliados e reconhecidos. Plataforma Sucupira. Brasília, DF: 2021. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://sucupira.capes.gov.br/sucupira/public/consultas/coleta/programa/quantitativos/quantitativoIes.jsf?areaAvaliacao=27&areaConhecimento=60200006 . Acesso em: 3 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

CANOPF, L. et al. Prática docente no ensino de administração: analisando a mediação da emoção. Organizações & Sociedade, Salvador, v. 25, n. 86, p. 371-391, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-9250862 [ Links ]

CAPES - Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior. Edital n. 29/2018: Resultado final. Brasília, DF: CAPES; PAEP, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/capes/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/24122018-resultado-final-edital-29-2018-pdf . Acesso em: 9 mar. 2022. [ Links ]

CARNEIRO, S. N. V. et al. A formação e a prática didático-pedagógica do docente bacharel no curso de Administração. Revista Diálogo Educacional, Curitiba, v. 18, n. 56, p. 209-230, 2018. https://doi.org/10.7213/1981-416X.18.056.AO02 [ Links ]

COSTA, D.; COSTA, A. M.; MELO, P. A. A retroalimentação da educação superior no brasil. Revista Pretexto, Belo Horizonte, v. 12, n. 2, p. 61-84, 2011. https://doi.org/10.21714/pretexto.v12i2.666 [ Links ]

CUNHA, M. I. O tema da formação de professores: trajetórias e tendências do campo na pesquisa e na ação. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 39, n. 3, p. 609-625, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-97022013005000014 [ Links ]

DARLING-HAMMOND, L. How teacher education matters. Journal of Teacher Education, Thousand Oaks, v. 51, n. 3, p. 166-173, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487100051003002 [ Links ]

DENICOL JÚNIOR, S. et al. Formação docente e bacharelado em Administração: o que traz o ENEPQ na ANPAd? Educação, Ciência e Cultura, Canoas, v. 23, n. 2, p. 265-276, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.18316/recc.v23i2.4420 [ Links ]

FERNANDES, J. D. et al. Expansão da educação superior no Brasil: ampliação dos cursos de graduação em enfermagem. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, Ribeirão Preto, v. 21, n. 3, p. 670-678, 2013. [ Links ]

FERREIRA, A. C.; MOURA, E. F.; VALADÃO JÚNIOR, V. M. Formação acadêmica: uma análise das disciplinas oferecidas pelos mestrados acadêmicos de Minas Gerais em Administração. Revista de Administração IMED, Passo Fundo, v. 5, n. 3, p. 277-290, 2015. https://doi.org/10.18256/2237-7956/raimed.v5n3p277-290 [ Links ]

FREIRE, P. Pedagogia da autonomia: saberes necessários à prática educativa. São Paulo: Paz e Terra, 1996. [ Links ]

GARCIA, C. M. A. Formação. novas perspectivas baseadas na investigação sobre o pensamento do professor. In: NÓVOA, A. Os professores e sua formação. Lisboa: Dom Quixote, 1995. p. 53-76. [ Links ]

GIOIA, D. A.; CORLEY, K. G.; HAMILTON, A. L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia Methodology. Organizational Research Methods, Thousand Oaks, v. 1, n. 16, p. 15-31, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151 [ Links ]

HAGEMEYER, R. C. C. Dilemas e desafios da função docente na sociedade atual: os sentidos da mudança. Educar, Curitiba, n. 24, p. 67-85, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.350 [ Links ]

IMBERNÓN, F. Formação docente e profissional: formar-se para a mudança e incerteza. 9. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2011. [ Links ]

INEP - Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Resumo técnico: Censo da Educação Superior 2014. Brasília, DF: INEP, 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://download.inep.gov.br/download/superior/censo/2014/resumo_tecnico_censo_educacao_superior_2014.pdf . Acesso em: 3 jan. 2019. [ Links ]

JUNGES, K. S.; BEHRENS, M. A. Prática docente no ensino superior: a formação pedagógica como mobilizadora de mudança. Perspectiva, Florianópolis, v. 33, n. 1, p. 285-317, 2015. https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-795X.2014v33n1p285 [ Links ]

JUSTEN, A.; GURGEL, C. Cursos de administração: a dimensão pública como sujeito excluído. Cadernos EBAPE. BR, Rio de Janeiro, v. 13, n. 4, p. 852-871, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-395112349 [ Links ]

JOAQUIM, N. F.; BOAS, A. A. V. Tréplica-formação docente ou científica: o que está em destaque nos programas de pós-graduação? Revista de Administração Contemporânea, Curitiba, v. 15, n. 6, p. 1.168-1.173, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-65552011000600013 [ Links ]

KARAWEJCZYK, T. C.; ESTIVALETE, V. Professor universitário: o sentido do seu trabalho e o desenvolvimento de novas competências em um mundo em transformação. In: ENCONTRO DA ASSOCIAÇÃO NACIONAL DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO E PESQUISA EM ADMINISTRAÇÃO 2003. Atibaia: ANPAd, 2003. p. 1-16. [ Links ]

LOCATELLI, C. Os professores no ensino superior brasileiro: transformações do trabalho docente na última década. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos, Brasília, v. 98, n. 248, p. 77-93, 2017. https://doi.org/10.24109/2176-6681.rbep.98i248.2815 [ Links ]

LOURENÇO, C. D. S.; LIMA, M. C.; NARCISO, E. R. P. Formação pedagógica no ensino superior: o que diz a legislação e a literatura em Educação e Administração? Avaliação, Sorocaba, v. 21, n. 3, p. 691-717, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-40772016000300003 [ Links ]

MALUSÁ, S.; POMPEU, C. C.; REIS, F. M. Educação superior: o ensino com pesquisa na prática do docente universitário. Cadernos de Pesquisa em Educação, Vitória, v. 19, n. 40, p. 11-26, 2014. [ Links ]

MARANHÃO, C. M. S. A. et al. Formação docente em administração: um estudo bibliométrico. Revista Gestão & Conexões, Vitória, v. 6, n. 2, p. 74-100, 2017. https://doi.org/10.13071/regec.2317-5087.2014.6.2.14371.74-100 [ Links ]

MILES, M. B.; HUBERMAN, A. M.; SALDANÃ, J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2014. [ Links ]

NOGUEIRA, A. F. M.; OLIVEIRA, M. A. G. Mercantilização e relações de trabalho no ensino superior brasileiro. Revista de Ciências Administrativas, Fortaleza, v. 21, n. 2, p. 335-364, 2015. https://doi.org/10.5020/2318-0722.2015.v20n2p335 [ Links ]

NUNES, E. Desafio estratégico da política pública: o ensino superior brasileiro. Revista de Administração Pública, Rio de Janeiro, v. 41, n. spe, p. 103-147, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-76122007000700008 [ Links ]

OSTEN, F. V. D. et al. Como se constituem os professores: a formação do professor de administração no Brasil. Curitiba: No prelo, 2019. [ Links ]

PATRUS, R.; SHIGAKI, H. B.; DANTAS, D. C. Quem não conhece seu passado está condenado a repeti-lo: distorções da avaliação da pós-graduação no Brasil à luz da história da CAPES. Cadernos EBAPE. BR, Rio de Janeiro, v. 16, n. 4, p. 642-655, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-395166526 [ Links ]

PRYJMA, M. F.; OLIVEIRA, O. S. O desenvolvimento profissional dos professores da educação superior: reflexões sobre a aprendizagem para a docência. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 37, n. 136, p. 841-857, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302016151055 [ Links ]

RODRIGUES, S. S. Políticas de avaliação docente: tendências e estratégias. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas na Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 20, n. 77, p. 749-768, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-40362012000400007 [ Links ]

ROLDÃO, M. C. Função docente: natureza e construção do conhecimento profissional. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 12, n. 34, p. 94-103 2007. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782007000100008 [ Links ]

SALDAÑA, J. Fundamentals of qualitative research: understanding qualitative research. New York: Oxford, 2011. [ Links ]

SALDAÑA, J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2016. [ Links ]

SANTOS, S. D. M. A precarização do trabalho docente no ensino superior: dos impasses às possibilidades de mudanças. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, n. 46, p. 229-244, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-40602012000400016 [ Links ]

SOUZA-SILVA, J. C.; DAVEL, E. Concepções, práticas e desafios na formação do professor: examinando o caso do ensino superior de administração no Brasil. Organizações & Sociedade, Salvador, v. 12, n. 35, p. 113-134, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-92302005000400007 [ Links ]

STAKE, R. E. Qualitative research: studying how things work. New York: The Guilford Press, 2010. [ Links ]

VALVERDE, T. et al. Enfrentando desafios da formação docente na pós-graduação: descrição de uma experiência. Formação Docente: Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa sobre Formação de Professores, Belo Horizonte, v. 9, n. 17, p. 67-84, 2017. https://doi.org/10.31639/rbpfp.v9i17.152 [ Links ]

VEIGA, I. P. A. Projeto político-pedagógico da escola: uma construção coletiva. In: VEIGA, I. P. A. (org.). Projeto político-pedagógico: uma construção possível. São Paulo: Papirus, 2011. p. 9-10. [ Links ]

VEIGA, I. P. A. Formação de professores para a educação superior e a diversidade da docência. Revista Diálogo Educacional, Curitiba, v. 14, n. 42, p. 327-342, 2014. https://doi.org/10.7213/dialogo.educ.14.042.DS01 [ Links ]

Received: May 15, 2020; Accepted: June 18, 2021

texto em

texto em