Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1413-2478versão On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.27 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub 30-Jun-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782022270055

ARTICLE

Social protection in schooling policies: some theoretical-political digressions

IUniversidade de Santa Cruz do Sul, Santa Cruz do Sul, RS, Brazil.

This article aims to examine the ways in which relevant formulators of schooling policies operate under a concept of social protection that is associated with and produced under the neoliberal gendarme. By enrolling in the field of schooling policies, it analyzes how social protection is dimensioned and intensified based on the logic of the school’s expanded social responsibility. Firstly, it places policymakers in a broader scope. Secondly, it deepens reflection about the Brazilian reality and offers some provocations. Methodologically, the article is based mainly on theoretical-political digressions from a critical perspective of analysis. The concepts of social protection presented here refer to the school as a place of welcome and protection, with creative spaces both inside and outside formal systems and the development of adaptable and flexible programs.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE social protection; schooling policies; neoliberalism

O presente artigo propõe-se a examinar os modos pelos quais os formuladores expressivos das políticas de escolarização operam sob uma concepção de proteção social atrelada e produzida sob o gendarme neoliberal. Ao inscrever-se no campo das políticas de escolarização, este estudo analisa como a proteção social é dimensionada e intensificada com base na lógica da responsabilidade social ampliada da escola. Primeiramente, sitia os formuladores das políticas em âmbito mais amplo. Como segundo movimento, realiza adensamentos acerca da realidade brasileira e tece algumas provocações. Metodologicamente, o artigo pauta-se eminentemente em digressões teórico-políticas desde a perspectiva crítica de análise. As concepções de proteção social exibidas fazem referência à escola como um lugar de acolhimento e proteção, com espaços criativos tanto nos sistemas formais quanto fora deles e com o desenvolvimento de programas adaptáveis e flexíveis.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE proteção social; políticas de escolarização; neoliberalismo

Este artículo tiene como objetivo examinar las formas en que los formuladores expresivos de las políticas escolares operan bajo un concepto de protección social vinculado y producido bajo el gendarme neoliberal. Al matricularse en el campo de las políticas escolares, este estudio analiza cómo la protección social se dimensiona e intensifica en función de la lógica de la responsabilidad social ampliada de la escuela. Primero, el estudio asedia a los formuladores de políticas en un ámbito más amplio. Como segundo movimiento, el estudio realiza densidades sobre la realidad brasileña y teje algunas provocaciones. Metodológicamente, el artículo se basa principalmente en digresiones teórico-políticas desde la perspectiva crítica del análisis. Los conceptos de protección social evidenciados se refieren a la escuela como un lugar de acogida y protección; con espacios creativos tanto dentro como fuera de los sistemas formales; con el desarrollo de programas adaptables y flexibles.

PALABRAS CLAVE protección social; políticas de escolaridad; neoliberalismo

INTRODUCTION

Combating the web of violence that often begins [...] in places that should shelter, protect and socialize people is a task that can only be accomplished by mobilizing a comprehensive protection network in which the school stands out as a possessor of expanded social responsibility. (Faleiros and Faleiros, 2007, p. 7)

In contemporary schooling policies, the discursive use of “shelter,” “protect,” “socialize” and “extended social responsibility” has become frequent, rather like a commonplace. The abovementioned epigraph refers to program School that Protects (Escola que Protege), developed by the Ministry of Education through the Secretariat of Continuing Education, Literacy and Diversity and Inclusion (Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização e Diversidade e Inclusão - SECADI) which, from 2004 to 2019, carried out activities in Brazilian schools. The objectives of the program were preventing and breaking the cycle of violence against children and adolescents in Brazil, by training professionals to act informedly in situations of violence identified or experienced in the school environment, promoting “management of care in a school that protects” through a “safety net” (Zapelini, 2010). Some universities also obtained decentralized resources to carry out the actions of such a program.

The School that Protects served municipalities that included in their Articulated Actions Program (Programa de Ações Articuladas - PAR) the promotion and defense, in the school context, of the rights of children and adolescents and the control and prevention of violence, as well as those that have a low Basic Education development index (Índice de Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica - IDEB) or were part of the Intersectoral Matrix to Combat the Sexual Exploitation of Children and Adolescents (Matriz Intersetorial de Enfrentamento da Exploração Sexual de Crianças e Adolescentes). Municipalities participating in the following programs were also served: More Education (Mais Educação); Program of Integrated and Benchmark Actions to Fight Sexual Violence against Children in the Brazilian Territory (Programa de Ações Integradas e Referenciais de Enfrentamento à Violência Sexual contra Crianças no Território Brasileiro - PAIR); and the National Program for Public Security with Citizenship (Programa Nacional de Segurança Pública com Cidadania). Through the training offered by the program to schools, elements were offered to the community, especially to professionals involved with children and adolescents, to fulfill their ethical commitments as agents responsible for the free development of the younger generations and for a comprehensive education policy yet to come (Faleiros and Faleiros, 2007).

It should be noted, then, that the valorization of a school that protects and cares for is not recent. “The school has, for a long time, assumed the position of a space for healing” (Fabris, 2014, p. 59). However, the advent of modernity has challenged it to further expand its purposes and come in contact with the social environment (Silva et al., 2014). When it comes to schooling policies in the contemporary Brazilian context, these policies gained different contours in the 1990s. Studies by Shiroma, Moraes and Evangelista (2007), Cavaliere (2009), Saviani (2009) and Evangelista (2013) describe governmental actions and State reconfigurations that took place in this period. In short, by presenting the School that Protects program it is possible to introduce the theme of the trends seen in social protection within school education, presenting theoretical-political digressions of some relevant formulators of this policy web.

In order to do so, the paper delves into the formulators of such a web in an international context, given their critical role in designing policies aimed at the school context. It seeks to emphasize the directions taken by such bodies since the 1990s, when schooling policies started to gain different contours in some reference documents: the Jomtien Declaration, with its emphasis on “satisfying basic learning needs,” and the New Delhi Education for All Declaration, in the 1990s; the Dakar Declaration in the 2000s, produced by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) - “the Dakar Framework for Action: Education for All;” and the executive summary of the World Bank, entitled Learning for All: Investing in People’s Knowledge and Skills to Promote Development - 2020 Strategy for Education, dating from 2011, which deals with more contemporary strategies.

The visibility given to Brazilian schooling policies reveals trends in social protection that are linked to the underlying logic of the formulators of this web, since international organizations start to play a tutorial role in the reforms of national States (Arrighi, 1998). Other policies worth highlighting are the latest National Education Plan (2014-2024), the document that guides Integral Education (Brasil, 2009), mentions of programs such as More Education, among others, and the National Common Curricular Base (Brasil, 2016). Having given these outlines, some considerations will be made about social protection policymakers.

RELEVANT FORMULATORS OF SOCIAL PROTECTION TRENDS IN BRAZILIAN SCHOOL EDUCATION

In his recent article “Educational policies in Brazil: the disfigurement of school and school knowledge,” José Carlos Libâneo (2016), referring to “an unsettling question: what are schools for?” elucidates how much the “dilemmas about the school’s objectives and ways of functioning are recurrent in the history of education.” For him, in discussions regarding the conceptions of school and knowledge, the latest research has shown that educational practices are “linked to group interests and power relations at international and national levels” (Libâneo, 2016, p. 40). In his studies, the researcher indicates one of the guidelines most present in World Bank documents, namely: “The institutionalization of poverty alleviation policies expressed in a conception of the school as a place of shelter and social protection, of which the implementation of an instrumental or results curriculum is one of the components” (Libâneo, 2016, p. 41). These policies carry the “disfigurement of the school as a place of cultural and scientific training and, consequently, the devaluation of significant school knowledge” (Libâneo, 2016, p. 41).

The decade that registered a strong international presence in Brazil in organizational and educational terms was the 1990s, a period marked “by major events, technical advice, and abundant documentary production” with regard to education (Frigotto and Ciavatta, 2003, p. 97). The so-called educational reform had, as its protagonists, “international and regional organizations associated with market mechanisms and representatives ultimately responsible for guaranteeing the profitability [...] of large corporations” (Frigotto and Ciavatta, 2003, p. 96). International organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) mentor the reforms of peripheral countries and direct educational investments (Arrighi, 1998). The World Trade Organization (WTO) also has an ascending influence, “since, in 2000, during one of its last meetings, it signaled to capital that one of the most fruitful spaces for profitable businesses was the educational field” (Frigotto and Ciavatta, 2003, p. 96).

In the specific field of education, “internationalization means the modeling of educational systems and institutions according to supranational expectations defined by international organizations linked to the great world economic powers, based on a globally structured agenda for education.” Supranational expectations are expressed “in the documents of national educational policies such as guidelines, programs, bills,” among other elements (Libâneo, 2016, p. 43). In addition to the international organizations mentioned, it is noteworthy that those most active “in the field of social policies, especially in education” are: the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the World Bank, the IADB, the UNDP, and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). These operate through international conferences and meetings (Libâneo, 2016, p. 43).

For example, the Jomtien Declaration signals “that education can contribute to achieving a safer world” (WCEA, 1990). Its third article discusses the universalization of access to education and the promotion of equity (WCEA, 1990). The New Delhi Declaration on Education for All, produced in India in 1993, refers to the education systems of countries that have already made important progress in providing education “to substantial contingents of [the] population,” and indicates the “need to develop creative approaches both inside and outside formal systems.” One of the elements it highlights is the “quality and relevance of basic education programs through the intensification of efforts to improve the status [...] and implement other necessary reforms to […] education systems” (UNESCO, 1993).

Yet another document, formulated in Dakar in 2000, brings out the need to rethink Brazilian educational policies “with a view to the new social horizons that are outlined for the 21st century,” where the biggest obstacle is the “elimination of poverty.” It points to the formulation of assistance policies as a priority to be taken by local governments, developing “adaptive and flexible programs” in education within national contexts (UNESCO, 2000, p. 18); the promotion of “inclusive educational policies with diversified modalities and curricula to serve the excluded population;” the “articulation of educational policies with intersectoral policies to overcome poverty,” aimed at the population in situations of social vulnerability (UNESCO, 2000, p. 31).

Among its most recent strategies, the World Bank, in the area of Education for the 2011-2020 decade, presented an executive summary entitled “Learning for All: Investing in People’s Knowledge and Skills to Promote Development - 2020 Strategy for Education by the World Bank Group -- Executive Summary” (Banco Mundial, 2011). Its preface points out that the “impressive rise of middle-income countries, led by China, India, and Brazil, has intensified the desire of many nations to increase their competitiveness through the development of more skilled workforces.” That is why the bank’s “strategy” for the Education sector up to 2020 sets the objective of “learning for all,” which is supported by three strategic pillars: investing early; investing smartly; investing for all (Banco Mundial, 2011).

The World Bank’s executive summary implements the key priority of “targeting the poor and vulnerable, creating opportunities for growth, promoting global collective action, and strengthening governance - set out in its recent post-crisis directions strategy” (Banco Mundial, 2011, p. 2). The new strategy is central to learning for one simple reason: “Growth, development, and poverty reduction depend on the knowledge and skills that people acquire, not on the number of years they spend sitting in a classroom” (Banco Mundial, 2011, p. 3). In this sense, learning for all means ensuring that “all students, not just the privileged, can acquire the knowledge and skills necessary for a happy and productive life” (Banco Mundial, 2011, p. 5). According to its outlines, “the know-how of education programs and policies is essential to improve the performance of education systems around the world” (Banco Mundial, 2011, p. 6).

The three international documents mentioned here in order to tap into aspects of the measures promoted from the 1990s onwards indicate the central role that such organizations play in the global macrostructure and, above all, in the guidelines concerning school education:

In the 1990s, the Jomtien and New Delhi (1993) Declarations on Education for All provided remarkable guidance to local policies; in other words, education, when offered “to substantial contingents” of the population, guarantees a “safe world;”

In the 2000s, the document formulated in Dakar points to new social horizons in the 21st century, pointing to the formulation of assistance policies, with the development of “adaptive and flexible programs” in education, as well as educational policies having “diversified modalities and curricula to serve the excluded population,” articulated with intersectoral policies to overcome poverty;

As the most recent strategy of the World Bank for the Education sector, with goals through to 2020, three emphases are seen in 2011: investing early, invest smartly and investing for all - pillars that enable all to acquire the knowledge and skills necessary for a happy and productive life.

The so-called relevant formulators of social protection trends in schooling policies inscribe education in an agenda of poverty alleviation, providing the “neoliberalism of a future” that places a supportive policy context at the top (Leher, 1998, p. 9). According to Marília Fonseca (1998), education is treated as a compensatory measure to protect the poor and alleviate possible tensions in the social sector. In the language of international organizations, “education is the solution to prevent the problems deriving from capitalist expansion, as a result of marginality and poverty. Hence, learning and schooling are meant, first and foremost, to help solve social and economic problems within the criteria of the global market” (Libâneo, 2016, p. 47).

There is, therefore, sufficient evidence that educational policies formulated by international organizations since 1990 have governed school policies in our country, and there are reasons to suspect that they have negatively affected the internal functioning of schools and the pedagogical-didactic work of teachers. With school education restricted to the purpose of solving social and economic problems and to market criteria, its role is compromised in its priority purposes of teaching content and promoting the development of students’ intellectual capacities. In this way, such policies lead to the impoverishment of the school and to low levels of student performance and, in so doing, lead to the social exclusion of students at school even before their social exclusion from society. (Libâneo, 2016, p. 48)

In view of the approaches outlined so far, it should be pointed out that the purpose of this study was to show that the centrality of social protection, associated with the emergence of neoliberalism, tends to produce new conceptions, different contemporary trends. Such conceptions can be observed in the set of measures taken by international organizations addressed in this study. In other words, the relevant formulators of schooling policies in Brazil operate guided by a concept of social protection linked to and produced under the neoliberal gendarme.

The concepts of social protection highlighted refer to the school, in general, as a welcoming shelter; with creative spaces both inside and outside formal systems; with basic education programs that intensify efforts to improve status; with the development of adaptable and flexible programs; with diversified modalities and curricula to serve the excluded population; with educational policies working alongside intersectoral policies to overcome poverty. A space that has the poor and vulnerable as its goal; a privileged place of poverty reduction that depends on the knowledge and qualifications people acquire, rather than the number of years they spend sitting in a classroom; where the knowledge and skills necessary for a happy and productive life are gained. These conceptions suggest that education contributes to building “a safer world.”

Having made this point, the paper will now show the ways in which relevant policymakers are mentioned in the local governmental policies of Brazil, as well as the tendential forms of social protection as depicted in national education policy documents such as guidelines, programs, bills, among others. In this sense, it asks the following questions: do schooling policies, especially contemporary ones, operate under a political logic that is anchored in the notion of social protection that has been gradually expanding? How do schooling policies articulate social protection actions?

BRAZILIAN EDUCATION POLICIES: SOME EVIDENCE OF SOCIAL PROTECTION TRENDS

In the approaches presented so far, emphasis can be perceived to fall mainly on: the quality and relevance of basic education programs (WCEA, 1990); the formulation of assistance policies as a priority to be taken by local governments in developing adaptable and flexible education programs (UNESCO, 2000); the interaction of education with intersectoral policies to overcome poverty; the know-how contained in education programs and policies (Banco Mundial, 2011). The School that Protects program makes it possible to visualize the articulation of a “social protection network” with the school as a central space, not only to welcome and make the world safe, but also as a strategic place to identify, denounce, and prevent forms of violence against children and adolescents - a place of expanded social responsibility (Faleiros and Faleiros, 2007).

In order to approach the ways in which Brazilian schooling policies articulate social protection actions, it must be pointed out that, with regard to the history of education, discussion around school policy formulation has had defining moments. One of these had to do with “the role of classical pedagogies” within the traditional conception of education. Another, in the first decades of the 20th century, referred to the Escola Nova movement, “inspired by John Dewey and other modern guidelines, as expressed in the Manifesto of the Pioneers of Escola Nova launched in 1932, led by Anísio Teixeira.” The National Education Association (Associação Nacional de Educação - ANDE), in the 1980s, played an important role in favor of a critical view of the democratization of education, prioritizing access to significant content (Libâneo, 2016, p. 48).

More recently, there have been movements to value public schools at the initiative of educators, almost always semi-official. Educational policies have been based on guidelines set by international organizations, as previously analyzed, since the Brazilian government’s adherence to the formal recommendations issued by the World Conferences on Education for All and other events sponsored by UNESCO and the World Bank. (Libâneo, 2016, p. 48)

Thus, with regard to policies that are supported by and adhere to international recommendations, such as those operating in Brazil, the education system’s expansion in the 1990s had its specifics. Researcher Eveline Algebaile (2009) points out that this expansion was not based on a consistent educational proposal, but there was an understanding that education minimizes risks and social tensions. Thus, to meet this idea, it was not necessary to devise a sophisticated education system; on the contrary, it sufficed to use the structure of the public-school network to provide social services, with the objective of alleviating poverty.

To deepen the matter, it is important to consider some current Brazilian policies on which notions of social protection and the articulation of actions are based, discussing the ways in which such policies and guiding documents contribute to the expansion and promotion of social protection. As an analytical material, some up-to-date references and guidelines for schooling policies in progress in Brazil are taken.

One of the planning instruments of our Democratic Rule of Law guiding the execution and improvement of public education policies is the National Education Plan. Among the strategies laid out to reach the 20 goals set by the new plan, the following stand out: an emphasis on the beneficiaries of income transfer programs, in collaboration with families and public agencies for social services, health, and protection; the creation of a protection network to counter associated forms of exclusion; the establishment of adequate conditions for educational success, in collaboration with families and public agencies for social work, health, and protection of children, adolescents, and youth; intersectoral coordination between public health, social services, and human rights bodies and policies, in partnership with families; the institution of a program to build schools with adequate architecture and furniture for the provision of full-time care, primarily in poor communities or for children in socially vulnerable situations; the offer, by private social service entities, of activities aimed at expanding the school day of students enrolled in public schools of basic education; the promotion, in partnership with the areas of health and social work, of access to school for specific population segments (Brasil, 2014, p. 50-65).

Another current reference text for the national debate is a document entitled Integral Education (Brasil, 2009), which presents a proposal for full-time schooling. The interaction between education, social services, culture, and sport, among other public policies, constitutes an important intervention for “social protection, prevention of situations of violation of the rights of children and adolescents, improvement of school performance and permanence in school, especially in more vulnerable territories” (Brasil, 2009, p. 25). The document also stresses that “we should not be afraid to admit that the school, at this point in time, occupies a central place in ‘caring’ for children and young people, even if it faces numerous challenges and does it in a solitary way” (Brasil, 2009, p. 29).

It considers, in addition, “the contexts of vulnerability and social risk,” recognizing that education is an “important resource for breaking the cycles of poverty” and that this is the converging challenge and commitment of the main social policies in Brazil today. Initiatives for the coordination of public policies in different social areas are considerable. “Social Services and Education, for example, have school attendance as a criterion for permanence in the Bolsa Família Program, which is verified by coordinated interministerial actions” (Brasil, 2009, p. 45). The document itself, when questioning “why integral education in the contemporary Brazilian context?,” claims that “an analysis of social inequalities [...] is required for the construction of an Integral Education proposal.” This construction, in Brazil, has taken place alongside the State’s efforts to offer redistributive policies to combat poverty (Brasil, 2009, p. 10).

We also highlight the New More Education Program as a “strategy of the Ministry of Education which aims to improve the learning of Portuguese and Mathematics in elementary school, by expanding the school day of children and adolescents.” Since 2017, the Program has focused on pedagogical monitoring in Portuguese and Mathematics and developed activities in the fields of arts, culture, sports, and leisure, boosting the improvement of educational performance by complementing the workload in five- or fifteen-hour per week shifts and after-school hours (Brasil, 2016). It should also be mentioned that among the poverty alleviation policies is the instrumental or results-focused curriculum, “associated with the curriculum of conviviality and social welcoming, with a strong appeal to social inclusion and acceptance of social diversity, aiming to prepare individuals for a type of citizenship based on solidarity and the containment of social conflicts” (Libâneo, 2016, p. 49).

Specifically with regard to the National Common Curricular Base published in 2016, the text makes it clear that the existence of a common base demands “coordinated actions in its resulting policies, without which it will not fulfill its role of contributing to the improvement of Basic Education quality in Brazil” (Brasil, 2016, p. 26). It also shows that, for “social inclusion to be effective, it is essential to incorporate the narratives of historically excluded groups into curricular documents.” The common base intends to “guide a Basic Education that aims at integral human formation, at the construction of a fairer society, in which all forms of discrimination, prejudice, and exclusion are fought” (Brasil, 2016, p. 33).

We now proceed to summarize the problematizations produced in this study.

POSSIBLE PROVOCATIONS

The in-depth analyses carried out so far provide an opportunity to build important understandings about social protection in School Education. As a central aspect, a permanent concern to equalize social inequalities through schooling is present throughout the investigative path pursued. The idea that the school is socially responsible stands out clearly, proving to be stronger than the concern with knowledge itself or the teaching-learning process, especially when contexts of social vulnerability are involved. When we analyze the guiding documents of Education, both international and national, which are endorsed by important researchers in the area, we note that schooling, especially from the 1990s onward, has been displaced to a secondary role by education policies, and education quality has become secondary in this view.

Attention should be brought to the fact that the implications of such a process have a greater impact on municipal education networks since, according to the school census, Brazil has 184.1 thousand basic education schools, the largest network being under the responsibility of municipalities (61.3%). The number of schools per education level is highest for the early years of elementary school, and lowest for high school (INEP, 2018). Bearing in mind these rates, enrollment rate in basic education is also relevant. There are 48.6 million students enrolled in the 184.1 thousand basic education schools in Brazil. The municipal network holds 47.5% of these enrollments (INEP, 2018).

Furthermore, in this space of provocations, it is noteworthy that, each plan, program and project addressed in this itinerary, while bearing its own specificities, is coordinately interconnected, making visible the concepts of social protection linked to and produced under the neoliberal gendarme. The theoretical-political digressions carried out in this study point to conceptions of social protection that view the school as a place of shelter and protection; that has creative spaces both inside and outside formal systems. These notions are far from the perspective of guaranteeing quality education as a social right. We argue, then, that the propagation of adaptable and flexible perspectives of schooling and the focus on the school as an expanded care space enable and facilitate the de-characterization of the central essence of education, namely: knowledge. Unfortunately, in parallel, the potential for social protection in the school environment is weakened.

Another important issue that deserves to be revisited refers to the regime of practice in which School Education has incorporated and operationalized the most varied, different and similar, social protection actions possible. By regime of practice, we understand the different forms of materializing social protection in School Education. This can be done by means of the different policies affecting the school, as is the case of the Social Services Policy underlined in this study. In this sense, a range of experiences carried out in the school as in other spaces acting intersectorally with basic education are again stressed, such as, for example, social work in contexts of social vulnerability.

We recall, then, that the first concrete experiences of Minimum Income Programs in Brazil and their coordination with schooling began with the Program for the Eradication and Prevention of Child Labor (Programa de Erradicação e Prevenção do Trabalho Infantil - PETI), in 1996. The program transfers income, which is conditioned to regular school attendance, as well as extended working hours in the complementary shift, and is currently part of the social services of the Unified Social Services System (Sistema Único de Assistência Social - SUAS). Expanding understanding, this program is part of the International Program for the Eradication of Child Labor (Programa Internacional para a Erradicação do Trabalho Infantil - IPEC), of the International Labor Organization, of which Brazil became a member in 1992. Prior to the PETI and on a small scale, the Bolsa Escola Program (1994), which included food and gas grants and registration in the Federal Government’s Single Registry, took on a greater proportion in 2001, when two far-reaching national programs were actually created: the National Minimum Income Program School Grant (Bolsa Escola), concerned with education, and the National Minimum Income Program Food Grant (Bolsa Alimentação), concerned with health. These were merged at the end of 2003 into Family Grant (Bolsa Família).

With regard to social services, the Service for Coexistence and Strengthening of Bonds (Serviço de Convivência e Fortalecimento de Vínculos - SCFV), belonging to the Basic Social Protection of SUAS and associated with the Social Services Reference Center (Centro de Referência em Assistência Social - CRAS). The national classification of social care services (Brasil, 2009) establishes that such services can be offered to: children aged 0 to 6, children and adolescents aged 6 to 15, and adolescents aged 15 to 17. It prioritizes situations of isolation, reception, child labor, violence and/or neglect, school dropout or delay of more than two years, serving of socio-educational measures in an open environment, previous serving of socio-educational measures, abuse and/or sexual exploitation, street living, vulnerability due to disability, protection measures as per the Child and Adolescent Statute (Estatuto da Criança e do Adolescente - ECA) (Brasil, 2009).

To deal continuously with sexual violence against children and youth in the Brazilian territory, the National Plan for Confronting Child and Youth Sexual Violence was launched in June 2000. Its objective was to promote coordination between all the main actors dealing with with children and adolescents that are vulnerable to sexual violence in the country, and it was approved by the National Council for the Rights of Children and Adolescents (Conselho Nacional dos Direitos da Criança e do Adolescente - CONANDA) of PAIR in 2002.

The School that Protects Program mentioned earlier in this study and developed by the Ministry of Education through SECAD, is noteworthy. Since 2004, it has carried out activities in Brazilian schools, defending the rights of children and adolescents, in addition to fighting and preventing violence in the school context. Its main strategy is financing projects for the continuing training of education professionals of the public basic network, in addition to producing teaching materials.

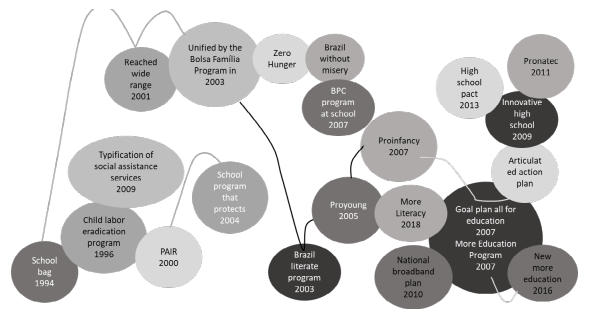

Programs such as Literate Brazil (Brasil Alfabetizado) (2003), the National Program for the Inclusion of Young People: Education, Qualification, and Community Action (Programa Nacional de Inclusão de Jovens: Educação, Qualificação e Ação Comunitária - ProJovem) (2005), the National Program for Restructuring and Acquisition of Equipment for the Public School Network of Early Childhood Education (Programa Nacional de Reestruturação e Aquisição de Equipamentos para a Rede Escolar Pública de Educação Infantil - Pro Infância) (2007) inaugurated a new regime of collaboration aimed at improving educational indicators. Adherence to the All for Education Commitment Goals Plan, intituted by Decree 6,094, of April 24, 2007, intensifies this collaboration regime, since states and municipalities devise their own coordinated action plans. The More Education Program (2007) was created in the same period.

The Benefit of Continued Provision in School (2007) stands out as a way of guaranteeing access to and permanence in school for disabled children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 who receive the Benefit of Continued Provision of Social Services (Benefício de Prestação Continuada da Assistência Social - BPC). It is an interministerial initiative involving the ministries of Social Development (Ministério do Desenvolvimento Social - MDS), of Education (Ministério da Educação - MEC), of Health (Ministério da Saúde - MS), and the Secretariat of Human Rights (Secretaria de Direitos Humanos - SDH). Following this, the National Broadband Plan gave tax exemptions and broadband internet access to the poorest population (2010), strengthening the idea of internet for all. The Brazil without Extreme Poverty (Brasil sem Miséria) Plan (2011) was created with the aim of overcoming extreme poverty throughout the national territory by integrating and coordinating policies, programs, and actions around three axes: income guarantee, access to public services, and productive inclusion. This plan was enhanced by Loving Brazil Action (Ação Brasil Carinhoso) (2012) as a way of tackling the problem of early childhood, where extreme poverty was more concentrated.

Focusing mainly on high school, the Innovative High School Program (2009) supports and strengthens the education systems of the states in developing innovative curriculum proposals for high schools. By the same token, the National Program for Access to Technical Education and Employment (Programa Nacional de Acesso ao Ensino Técnico e Emprego - Pronatec) was created by the Federal Government in 2011 and culminated in the National Pact for the Strengthening of Secondary Education, instituted in 2013. More recently, the New More Education Program (2016) is a strategy of the Ministry of Education which aims to improve learning in Portuguese and Mathematics in elementary school, by extending the school journey. Likewise, the More Literacy (Mais Alfabetização) Program (2018) aims to strengthen and support school units in the literacy process of students regularly enrolled in the 1st and 2nd years of elementary school. The Figure 1 is presented to summarize these initiatives.

Source: the author, 2018.

Figure 1 - Regime of practice of social protection in School Education in Brazil, 1994 to 2018.

Of course, it is not possible to list all existing programs. It is, however, possible to visualize the diversity of actions permeating School Education, if not directly, within the curriculum, then in a complementary, extracurricular way. Not all the points made here relate to school contexts affected by different forms of social vulnerability, but, for the most part, this is a central issue. Thus, to make a metaphorical allusion: are we, in our time, building a “shopping mall of the social” in the school space? Is the “vulnerable student,” always subject to public or private investment, who has his “gifts,” “talents,” and “dreams” addressed by socio-educational programs and projects, actually waving, at a distance, to the future? (Tavares et al., 2011 apudOliveira, 2014, p. 42).

REFERENCES

ALGEBAILE, E. Escola pública e pobreza no Brasil: a ampliação para menos. Rio de Janeiro: Lamparina, 2009. [ Links ]

ARRIGHI, G. A ilusão do desenvolvimento. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1998. [ Links ]

BANCO MUNDIAL. Aprendizagem para todos. Estratégia 2020 para a Educação do Grupo Banco Mundial. Resumo Executivo. Washington, D.C.: Banco Mundial, 2011. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://docplayer.com.br/24758-Aprendizagem-para-todos-investir-nos-conhecimentos-ecompetencias-das-pessoas-para-promover-o-desenvolvimento.html . Acesso em: 13 fev. 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Educação integral. Brasília: MEC, 2009. (Série Mais Educação.) Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/dmdocuments/cadfinal_educ_integral.pdf . Acesso em: 15 fev. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Plano Nacional de Educação 2014-2024. Lei nº 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014, que aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação (PNE) e dá outras providências. Brasília: Câmara dos Deputados, Edições Câmara, 2014. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2014/lei/l13005.htm . Acesso em: 14 fev. 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Segunda versão revisada. Brasil: Ministério da Educação, 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/ . Acesso em: 15 fev. 2017. [ Links ]

CAVALIERE, A. M. Escolas de tempo integral versus alunos em tempo integral. Em Aberto, Brasília, v. 21, n. 80, p. 51-63, abr. 2009. https://doi.org/10.24109/2176-6673.emaberto.21i80.2220 [ Links ]

EVANGELISTA, O. Qualidade da educação pública: Estado e organismos multilaterais. In: LIBÂNEO, J. C.; SUANNO, M. V. R.; LIMONTA, S. V. (org.). Qualidade da escola pública: políticas educacionais, didática e formação de professores. Goiânia: Ceped, 2013. p. 13-46. [ Links ]

FABRIS, A. T. H. A escola contemporânea: um espaço de convivência? In: SILVA, R. R. D. (org.). Currículo e docência nas políticas de ampliação da jornada escolar. Porto Alegre: Evangraf, 2014. p. 47-66. [ Links ]

FALEIROS, V. P.; FALEIROS, E. S. Escola que protege: enfrentando a violência contra crianças e adolescentes. Brasília: UNESCO; Ministério da Educação, Secretaria de Educação Continuada, Alfabetização e Diversidade, 2007. (Coleção Educação para Todos, 31.) Disponível em: Disponível em: https://bds.unb.br/handle/123456789/817 . Acesso em: 4 fev. 2017. [ Links ]

FONSECA, M. O Banco Mundial e a educação brasileira: uma experiência de cooperação internacional. In: OLIVEIRA, R. P. (org.). Política educacional: impasses e alternativas. 2. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 1998. p. 85-122. [ Links ]

FRIGOTTO, G.; CIAVATTA, M. Educação básica no brasil na década de 1990: subordinação ativa e consentida à lógica do mercado. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 24, n. 82, p. 93-130, abr. 2003. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302003000100005 [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA (INEP). Censo Escolar 2017. Notas Estatísticas. Brasília: INEP, jan. 2018. [ Links ]

LEHER, R. Da ideologia do desenvolvimento à ideologia da globalização: a educação como estratégia do Banco Mundial para “alívio” da pobreza. 1998. 267 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 1998. [ Links ]

LIBÂNEO, J. C. Políticas educacionais no Brasil: desfiguramento da escola e do conhecimento escolar. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 46, n. 159, p. 38-62, jan./mar. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053143572 [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, M. C. A. As políticas de proteção social no contexto escolar. 2014. 145 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, 2014. [ Links ]

ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS PARA A EDUCAÇÃO, A CIÊNCIA E A CULTURA (UNESCO). Declaração mundial sobre educação para todos e plano de ação para satisfazer as necessidades básicas de aprendizagem. Jomtien: UNESCO, 1993. [ Links ]

ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS PARA A EDUCAÇÃO, A CIÊNCIA E A CULTURA (UNESCO). O marco de ação de Dakar Educação para Todos. UNESCO, 2000. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001275/127509porb.pdf . Acesso em: 12 fev. 2017. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, D. PDE - Plano de Desenvolvimento da Educação: análise crítica das políticas do MEC. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2009. [ Links ]

SHIROMA, E.; MORAES, M.; EVANGELISTA, O. Política educacional. 4. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Lamparina, 2007. [ Links ]

SILVA, R. R. D. et al. Políticas contemporâneas de escolarização no Brasil: uma agenda investigativa. Curitiba: CRV, 2014. [ Links ]

WORLD CONTINUING EDUCATION ALIANCE (WCEA). Satisfacción de las necesidades básicas de aprendizaje: una visión para el decenio de 1990. In: CONFERÊNCIA MUNDIAL SOBRE LA EDUCACIÓN PARA TODOS, 1990, Jomtien, Tailândia. Anais [...]. Jomtien, 1990. [ Links ]

ZAPELINI, C. A. E. (org.). Módulo 2: violências, Rede de Proteção e Sistema de Garantia de Direitos. Florianópolis: NUVIC-CED-UFSC, 2010. [ Links ]

Received: July 07, 2020; Accepted: July 15, 2021

texto em

texto em