Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Compartilhar

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versão impressa ISSN 1413-2478versão On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.27 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub 26-Ago-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782022270078

ARTICLE

Full-time teaching and segmentation of the offer: analysis of the ETI and PEI programs in the São Paulo state public system

IUniversidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

IISecretaria da Educação do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

The article analyzes the implementation of two Full-Time Teaching Programs in the state public education system of São Paulo, seeking to understand their effects on the dynamics of the system with a focus on expanding the segmentation of educational offer and educational inequalities. For that, we resorted to the analysis of documents that guide the programs, interviews with former secretaries and members of the State Department of Education, as well as producing, from the microdata of the School Census (2019), graphs, tables and maps to understand the organization of each of the programs. The data show that, although they originally had different proposals, the two programs are currently similar in terms of supply and service conditions, better than those found in other schools in the chain. Thus, it is possible to verify the segmentation of the offer on the network, induced by the Programs, which can contribute to the reproduction of educational inequalities.

KEYWORDS full-time teaching; offer segmentation; educational inequalities

O artigo analisa a implementação de dois Programas de Ensino em Tempo Integral na rede pública estadual de educação de São Paulo, buscando compreender seus efeitos sobre a dinâmica da rede com foco na ampliação da segmentação da oferta educacional e das desigualdades educacionais. Para tanto, recorremos à análise de documentos que norteiam os programas, a entrevistas com ex-secretários e membros da Secretaria Estadual de Educação, bem como produzimos, a partir dos microdados do Censo Escolar (2019), gráficos, tabelas e mapas para compreender a organização de cada um dos programas. Os dados apontam que, apesar de originalmente terem propostas diferentes, os dois programas se assemelham, atualmente, no que se refere às condições de oferta e atendimento, melhores do que as encontradas nas demais escolas da rede. Com isso, é possível verificar segmentação da oferta na rede, induzida pelos Programas, que pode contribuir na reprodução das desigualdades educacionais.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE ensino em tempo integral; segmentação da oferta; desigualdades educacionais

El artículo analiza la implementación de dos Programas de Enseñanza de Tiempo Completo en la red pública educativa estatal de São Paulo, buscando comprender sus efectos en la dinámica de la red con un enfoque en ampliar la segmentación de la oferta educativa y las desigualdades educativas. Para ello, se recurrió al análisis de documentos que orientan los programas, entrevistas a exsecretarios y miembros de la Secretaría de Estado de Educación, así como a producir, a partir de los microdatos del Censo Escolar (2019), gráficos, tablas y mapas para comprender la organización de cada uno de los programas. Los datos muestran que, aunque originalmente tenían propuestas diferentes, los dos programas actualmente son similares en términos de condiciones de oferta y servicio, mejores que los encontrados en otras escuelas de la cadena. Así, es posible verificar la segmentación de la oferta en la red, inducida por los Programas, que puede contribuir a la reproducción de las desigualdades educativas.

PALABRAS CLAVE enseñanza a tiempo completo; segmentación de ofertas; desigualdades educativas

INTRODUCTION

The theme of Integral Education has marked the history of education in Brazil and, recently, with the approval of the High School Reform,1 it has come to the fore in debates on educational policy. In the case of the state public education in São Paulo, two Integral Education Programs2 were developed. The first one, the Escola de Tempo Integral Program (Programa Escola de Tempo Integral - ETI),3 was launched in 2005 under Gabriel Chalita’s management at the State Education Bureau (Secretaria Estadual de Educação - SEDUC-SP);4 the second, the Ensino Integral Program (Programa de Ensino Integral - PEI),5 was launched in 2012, during the administration of Hermann Voorwald as part of the Educação - Compromisso de São Paulo (ECSP)6 program. In 2020, both programs were still running. However, while a decrease in ETI schools has taken place, there has also been a significant increase in PEI schools in recent years.

Thus, the main objective of this text was to understand the effects of these programs on the dynamics of the state public education network in São Paulo, focusing on the possible expansion of the stratification7 of educational offers and educational inequalities. So as to develop this investigation, survey and analysis of the resolutions were carried out, considering guidelines for both programs and which are available on the SEDUC-SP website.8 In addition, a set of graphics, tables, and maps were produced based on microdata from the School Census (Censo Escolar, 2019),9 in order to understand the dynamics of the organization of each program. At the same time, we used interviews with former secretaries of Education and members of SEDUC-SP. This material was obtained within the scope of the research “Política educacional na rede estadual paulista (1995 a 2018)”,10 funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP),11 which analyzed the management dynamics of São Paulo’s public education system. All the heads of the department, who remained in the position for more than one year during the research, were willing to grant an interview, except for one person.12

In this way, the text was organized into three sections. In the first one, there is a brief review of the Integral Education literature, seeking to have both programs under analysis in the different theoretical-conceptual perspectives and the recent agenda of educational-related policies in Brazil. In the second section, the documents that guide these programs of São Paulo’s public education system were presented and discussed. In the third section, the data set on both programs were analyzed, having the year 2019 as a reference. As mentioned before, the objective of this study was to understand the similarities and differences between the two programs as well as their impacts on the organization of public education in the state.

INTEGRAL EDUCATION IN DISPUTE

The theme Integral Education has been present in educational debates for a long time. According to Cavaliere (2010), the concept has been used from the classical conception of Athenian Paideia, which sought to develop the formation of subjects in different aspects of the human condition: cognitive, emotional, and societal. The expansion of schooling throughout the Modern era, marked by an education split from everyday life, led to the emergence of educational trends that proposed to (re)establish the link between school education and life at the end of the 18th century. “Integral Education” emanated from these formulations by presenting varied conceptions from the philosophical-educational movements, such as Rousseau’s naturalism, Basedow’s philanthropism, Condorcet’s political education, Pestalozzi’s social neo-humanism, the pedagogy of action of Dewey, the pedagogy of work by Blonski (Larroyo, 1974), or even the polytechnic in the Marxist tradition (Machado, 1989).

In Brazil, the theme stands out in different proposals during the 20th century, highlighting the Manifesto dos Pioneiros da Educação Nova,13 from 1932; the Escola-Parque or Centro Educacional Carneiro Ribeiro,14 conceived by Anísio Teixeira and implemented in 1950 in Bahia; the Ginásios Vocacionais15 of the 1960s, in São Paulo; the Centros Integrados de Educação Pública (CIEP),16 conceived by Darcy Ribeiro and implemented in the 1980s, under Leonel Brizola’s administration in Rio de Janeiro - popularly known as “Brizolões”; and the Centros Educacionais Unificados (CEU),17 inaugurated in 2003 in the city of São Paulo under Marta Suplicy’s administration.

Keeping due differences between such movements and conceptions, the concept of Integral Education is directly linked to the understanding of a multidimensional formation of individuals, considering the different forms of expressing knowledge and the need to value the multiple formative experiences that lack in the school space. However, the concept of Integral Education does not necessarily correspond to the expansion of the school hours, typical of Full-Time Teaching models. Such conceptions, erroneously seen as homologous, correspond to two distinct models that have their own characteristics and that must be distinguished for a better understanding.

There is no need to present here the broad debate in the literature about the differences between education and teaching, which is not the scope of this text. In general terms, it is worth noting that the concept of education involves a more comprehensive and complex proposal for the formation of individuals, which is composed of curricular content learning, but also of attitudes and values that aim at human development in its entirety. Teaching, on the other hand, is understood mainly as the transmission of curricular content and knowledge, established as a more restricted and specific proposal for the formation of individuals (Paro, 2018). This distinction reinforces the interpretation evidenced throughout this article, that the programs developed by SEDUC-SP being analyzed here are defined as Full-Time Teaching proposals, since they are based on the expansion of the daily-school hours - more hours of classes per day, meaning the expansion of contents transmitted to students - and not as programs of Integral Education, whose proposal should be structured in order to provide students with a broad formation of individuals in the different spheres that build human development.

Considering educational regulations, the Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional (LDB)18 from 1996 (Brasil, 1996a) brings a forecast of gradual expansion in school hours through a common effort between municipalities, states, and Federal Union in articles 34 and 87. But it was only with FUNDEB,19 in 2007, that there was a financial contribution to the municipalities and states which contributed to an increase in daily-school hours. In the same year, as part of the Education Development Plan (Plano de Desenvolvimento da Educação - PDE),20 the federal government developed Mais Educação,21 which is the main policy that triggers Integral Education, initially focused on schools with students from families in situations of social vulnerability.

Alongside these processes, movements in favor of public education put full-time education under the spotlight, making it part of the National Education Plan (Plano Nacional de Educação - PNE)22 between the years 2014-2024. In target 6 of this law, it is seen that the offer of this teaching model must be “at least 50% (fifty percent) of public schools” corresponding to “at least 25% (twenty-five percent) of students in Elementary School” until 2024 (Brasil, 2014). Item 6.2 recommends that the most vulnerable sectors of the population will be the focus of public policy, prioritizing early childhood education.

Studies that deal with different aspects were found in the programs of São Paulo, such as the work done by Mota (2008), which brought a debate on the changes in teachers’ labor rights since the implementation of the ETI Program in 2005. In order to make changes in work dynamics in ETI schools, Faveri (2013) analyzes the action of workshop professionals in schools in Campinas, relating it to the process of the precariousness of teachers’ work conditions. In addition, Dib (2010) analyzes the relationship between ETI and the improvement of learning, especially those linked to the São Paulo Education Assessment and Performance System (Sistema de Avaliação e Rendimento de Educação de São Paulo - SARESP),23 based on a case study in a public school located in Assis, countryside of the state of São Paulo. Some of the studies focus on the problems of implementing full-time policies in the state public-education system of São Paulo. In one of them, Torres (2016) demonstrates the inconsistencies between the documents that guide the ETI Program and the conditions found in a school in the city of São Paulo.

In another research, we found investigations that seek to understand similarities and differences between both education programs adopted in the state public education-system of São Paulo. In one of them, Babalim (2016) analyzes the programs’ conceptions of integral education based on interviews with teachers and pedagogical coordinators of the schools involved. However, the analysis ends up focusing only on teachers and coordinators of PEI schools, which makes a detailed analysis of this comparison difficult. The work by Valentim (2018) presents a more detailed comparison of both policies, with an emphasis on continuities and discontinuities, taking guidelines, conceptions, curricular dynamics, implications for teaching work, school infrastructure, among other aspects into account.

Despite the range of topics covered, there are still few studies that seek to comparatively analyze both programs in terms of coverage, enrollment dynamics, spatial dimension, as well as the effects that each of them has on the overall dynamics organization of the educational system. From our perspective, it is essential to assess the possible impacts of these Full-Time Teaching programs on school inequalities. On the one hand, this discussion is even more important when the extension of the school hours does not occur with the expansion of the size of the education public system (for example: without the construction of new schools) and, still, without the development of compensatory policies that minimize the inequalities of access and permanence, as it has been happening in the case of the state education public system of São Paulo. The understanding of the characteristics and problems that mark both São Paulo Programs can give us information to comprehend and improve the policy aiming at equity in the national context of Full-Time Teaching advancement.

Thus, the next section of the text aimed to present both programs of Full-Time Teaching developed by the state of São Paulo, analyzing their guidelines and resolutions in order to relate them with the analysis of the data in the third section of this article.

ETI AND PEI: PRINCIPLES AND LEGISLATION

In 2005, the state government of São Paulo started the implementation of the ETI24 project, which aimed to extend the time spent by students in school from 5 to 9 hours by offering curricular workshops after school hours. Covering all grades of Elementary and High School, the project started in 508 schools, gradually decreasing to 215 in 2019. Without receiving extra investment from the state government, the schools that joined the program did not undergo physical adaptation and neither did their teaching staff have specific training. (Caiuby and Boschetti, 2015)

According to resolution by SEDUC-SP n. 89, from December 9th, 2005, in article 2, the project’s main objectives are:

to promote student’s permanence in school, fully assisting them in their basic and educational needs, reinforcing school performance, self-esteem, and the feeling of belonging;

to intensify opportunities for socialization at school;

to provide students with alternatives for action in the social, cultural, sporting, and technological fields;

to encourage community participation through engagement in the educational process implementing the construction of citizenship;

to adapt educational activities to the reality of each region, developing the entrepreneurial spirit. (São Paulo, 2005)

It is important to emphasize that such objectives point to the strengthening of the bond between students and the school unit (SU), enhancing the understanding of the school as a privileged place for the socialization of children, adolescents, and young people. Due to the objectives expressed in the resolution, it is possible to have ETI as one of the Full-Time Education policies close to what Cavaliere (2007) called the welfare concept.

Concerning the criteria for choosing the schools that will participate in the Program, the option for areas of great social vulnerability is evident (São Paulo, 2005), being closer to what is later reassured by PNE (2014-2024).

In relation to curricular dynamics, Article 5 of the aforementioned Resolution points out that:

The ETI curricular organization includes the basic curriculum of Elementary School and actions aimed at:

Istudy guidance;

Artistic and Cultural activities;

Sports activities;

Social Integration activities;

Curricular Enrichment activities. (São Paulo, 2005)

One of the main criticisms in relation to the curricular organization concerns the hiring of workshop professionals in very different working conditions from those of other education professionals. As mentioned in the previous section of the article, there is a set of investigations that analyze the implications of ETI in the process of precariousness of working conditions in the state public education system of São Paulo, with emphasis on workshop professionals.

Thus, it is possible to verify that ETI is consolidated as a program to extend school hours, focusing on populations in vulnerable areas and based on a perspective that includes the school as an important space for socialization. Although it is not possible to verify a direct relation with the production of educational results mindset in the documents that establish the Program, mainly measured from standardized evaluations, which is one of the hallmarks of the management model adopted by SEDUC-SP since 1995, some researchers identify such mindset in some of the activities developed in ETIs. Torres (2016), when investigating an ETI school in the city of São Paulo, highlighted the centrality that SARESP occupies in the conduction of activities, in the planning processes, and in teachers’ meetings producing a process of curricular narrowing in the opposite direction of a possible proposal of Integral Education.

In 2011, as part of the São Paulo ECSP,25 the state government, during the administration of Herman Voorwald, presented PEI26, laying “the foundations of a new school model and a more attractive policy for teachers’ career” (São Paulo, 2014a, p. 6). Starting in 2012, having 16 high schools spread over 13 cities, it incorporated Elementary schools the following year and reached a number of 417 schools located in 152 municipalities in 2019. The Program is distinguished by having:

1) full-time students, with integrated, flexible, and diversified curricular standards; 2)school aligned with the reality of young people, preparing students to carry out their Life Project and be protagonists of their education; 3) infrastructure with theme rooms, reading rooms, science, and computer labs; and 4) teachers and other educators in a regime of full and integral dedication to each school. (São Paulo, 2014a, p. 13)

PEI schools present some curricular changes, such as the inclusion of elective subjects, Study Orientation, Youth Clubs, Life projects, and nine and a half hours of tutoring classes in the weekly work schedule. Based on SE Resolution n. 68, of December 12th, 2019 (São Paulo, 2019a), PEI schools that offer Final Years Elementary School and High Schools were able to organize themselves in a single shift, lasting nine hours and 50-minute classes, or two seven-hour shifts, with 45-minute classes.

Specific conditions are established for teaching work, such as the Full and Integral Dedication Regime (Regime de Dedicação Plena e Integral - RDPI),27 defining 40 week-working hours to be fully complied with at the school; and the Full and Integral Dedication Bonus (Regime de Dedicação Plena e Integral28 - GDPI) which adds a value of 75% to the base salary.29 It is worth mentioning that, so as to work in PEI schools, teachers go through a selection process and, after being approved, are qualified to work as PEI teachers. This means that they do not have stability in the position in that school, despite maintaining the employment bond with SEDUC-SP as a public servant. In order to remain in the position, teachers need to undergo periodic evaluations, as described in paragraph 2 of article 1 of resolution SE n. 68, of December 17th, 2014:

§ 2 - The evaluation of their performance will subsidize the decision regarding the permanence of the professional in the Program, depending on the development of skills, engagement, and fulfilment of the attributions provided for in the pedagogical and/or management model, as the case may be, in accordance with what establishes Complementary Law 1164, of January 4, 2012. (São Paulo, 2014b)

To join the Program, schools must respect minimum infrastructure and demand30 criteria, defined annually by the State Department of Education, and have the consent of the School Council. After joining, they receive a higher financial contribution when compared to another state’s public education system. A good example of the difference in budget between PEI schools and other schools is that the average cost per student among school units in regular part-time education was BRL 3,446.00 (being BRL 527.00 Operational, BRL 1,981.00 Teachers*, and BRL 937.00 School Staff) in 2017. In PEI schools, it was a total of BRL 9,073.00 (BRL 1,103.00 Operational, BRL 5,580.00 Teachers*, and BRL 2,387.00 School Staff) - an increase of 163%.31

Therefore, it is possible to verify that both Full-Time Teaching programs developed by SEDUC-SP have different operational and organizational principles. On the one hand, we have a model based on the perspective of extended school hours for the poorest population, without relevant curricular changes (only the adoption of workshops in the afternoon) or transformation in the conditions of infrastructure, work, and permanence of students. On the other hand, we have a program based on the perspective of a management-result mindset, based on the pressure on teachers and students, expressed by the job instability in schools, for instance. However, a more detailed look at both programs’ data can help to understand their current similarities, as well as the raising of explanatory hypotheses.

Thus, in the next section of this text, we sought to understand how these two models of Full-Time Teaching impact the general school dynamics, enrollment-condition offers, and the increase or decrease of educational inequalities among the schools in the state.

ETI AND PEI: EXPANDING SCHOOL HOURS, OFFER’S STRATIFICATION

Data from the School Census was the reference to carry out the analysis presented in this section of the text, available on the website of Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira (INEP)32 for the year 2019, covering the entire territory in the state of São Paulo. Information related to the number of schools in each program comes from a consultation with SEDUC-SP. Data referring to the Education Development Index of the State of São Paulo (Índice de Desenvolvimento da Educação do Estado de São Paulo - IDESP)33 were collected from the Educational Data website of the State Education Bureau.34 The information related to the Management Complexity Index (Índice de Complexidade de Gestão - ICG)35 and INSE36 were obtained from the INEP Educational Indicators website.37 The website of Fundação Sistema Estadual de Análise de Dados38 (SEADE), an agency belonging to the state of São Paulo, was the source of the data about the São Paulo Social Vulnerability Index (Índice Paulista de Vulnerabilidade Social - IPVS).39 Data were pulled together by making use of RStudio, Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS), and Microsoft® Excel® software, which also contributed to the development of graphics and tables.

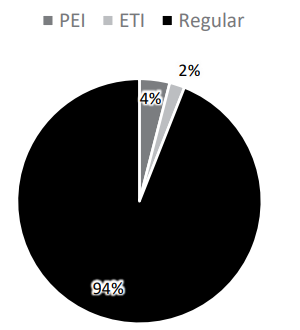

Concerning general data, 4,602 regular public schools out of more than 5,000 schools managed by SEDUC-SP were identified in 2019, in addition to PEIs (417) and ETIs (215), with 3,123,111, 141,817, and 62,954 enrollments in each program, respectively. The enrollment distribution in the education public system is illustrated in Graphic 1.

Source: Organized by the authors, 2022, based on Censo Escolar, 2019 (INEP, 2020a).

Graphic 1 - Enrollment Distribution in the state public-education system of São Paulo (2019).

When comparing the dynamics and the type of service offered, it is possible to notice differences between PEI, ETI, and other public schools in the state of São Paulo (Chart 1). Firstly, it is possible to highlight that both programs take place in schools with a lower average of enrollments: while PEI schools have an average of 50.5% fewer enrollments, ETI schools have 43.1% fewer enrollments compared to regular schools. The number of classes also reflects such data. In both PEI and ETI schools, the average number of classes per school is 50% lower than in regular schools. Regarding the average number of students per class, there were no significant differences when comparing PEI schools with regular ones. On the other hand, ETIs have classes 13% smaller than those seen in regular schools.

Chart 1 - Statistical information - Averages (2019).

| Average enrollment per school | Average of classes per school | Average number of students per class | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | 679 | 22 | 32 |

| PEI | 340 | 11 | 33 |

| ETI | 293 | 11 | 28 |

Source: Organized by the authors, 2022, based on Censo Escolar, 2019 (INEP, 2020a).

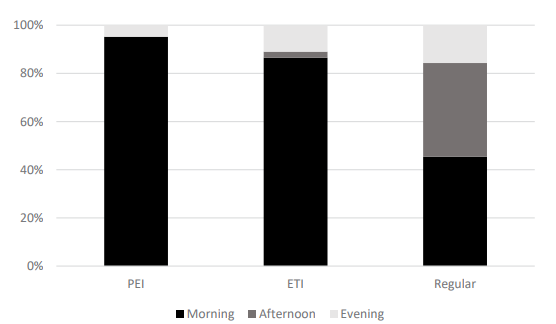

Regarding the shift and stage of enrollment distribution, it is possible to verify (Graphic 2) that both PEI and ETI schools concentrate their activities during the day. However, it is important to emphasize that the presence of night enrollments in ETIs is more significant than in PEI schools and it is also closer to the numbers in regular schools, which is also confirmed when it comes to the percentage of Young-Adult Education enrollments.

Source: Organized by the authors, 2022, based on Censo Escolar, 2019 (INEP, 2020a).

Graphic 2 - Shift enrollment distribution in PEI, ETI, and Regular schools (2019).

In an interview,40 João Palma, Assistant Secretary of Education of São Paulo between 2011 and 2013, points out the impacts of the Program on enrollment dynamics:

Sure enough, 700 out of thousands of students changed schools when they got to know that it would become a full-time school. Until today, you can see that the average student in these so-called full-time schools is no more than 400. They became small schools. And they were schools that had twice or three times as many students. Where did they go? They changed to those that were not full-time, and some even dropped out.

The interviewee also highlights the effect on enrollment offer in evening classes:

And another thing, they abandoned the evening shift. They abandoned the evening shift and are emptying the YAE. As I see it, the reality is that young workers are not taken into account, disregarding the law that states that these schools must take students’ conditions into account, etc. So, if the Department of Education valued the students who work, they would have already built a pedagogical project for them.

According to Palma, in the context of the elaboration of the policy, it is possible to perceive that there was some concern about the possible impacts that it could have on enrollment dynamics in the schools in the state of São Paulo. It acknowledges that the choices made also considered such impacts and assumed them to be one of the social costs to implement the policy. If we add this information to the impossibility of universalizing the Program, pointed out by the secretary, Herman Voorwald,41 the effect of stratification in the state public-education system of São Paulo produced by the Program is even more evident.

Universalization is not supported by this model, for several reasons. First, the vast majority of municipalities with less than 50,000 inhabitants in the state of São Paulo have one public High School. And how do you turn a public High School into a full-time school? You cannot. So, you don’t have the facilities to make it possible. The second reason is that, in many cases, the family needs the youngsters to work or to take care of the siblings after school hours. So those pupils can’t go to school, even if they want to. We’ve talked to these parents countless times so that they would not take children out of these schools.

It is also worth mentioning that there was tension between the defenders of PEI and ETI due to the different treatment received by each program. It was pointed out in an interview42 with Valéria de Souza, who worked in the administration of the State Education Bureau under Herman Voorwald management, responsible for the articulation of ECSP and manager of PEI:

(...) But it was difficult because we had an ETI school, which was in the background, you know? It is complicated. I said, “Secretary, you have a school model in a group, you have...”, he said, “no, integral education, the more it expands, the more absorbs the ETI”. And it was very harmful to state public-education system of São Paulo in the state because they even made jokes saying the ETI was the ugly duckling while full-time education was the beloved child. So, it got even more complicated. Today, after so many years of expansion, the ETIs are all migrating to the Full-Time Teaching Program. But we had a lot of tension in the schools, which is complicated because the Secretary is passionate about the Programa Ensino Integral.

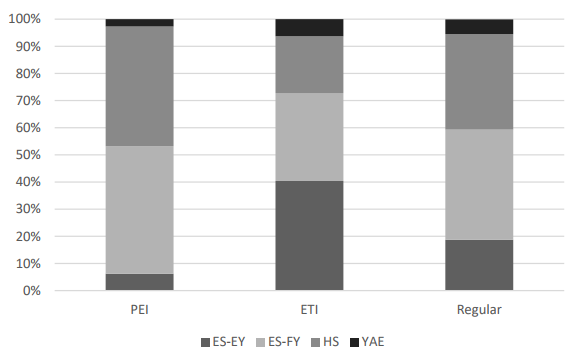

Regarding the crossing information of stage/modality enrollments, there is a difference between these programs. It is evident from the data in Graphic 3 that ETI schools concentrate enrollments in Elementary Education, being 40% in the early years. On the other hand, PEI schools have less than 5% of enrollments at this stage, concentrating offerings in the final years of Elementary School and High School. Although both programs are similar in the distribution of enrollments regarding the final years of Elementary School compared to regular schools, it appears that ETI schools have a higher concentration of enrollments in the early years of Elementary School. Moreover, PEI schools have a higher concentration of enrollment in High School compared to the distribution in regular schools.

Source: Organized by the authors, 2022, based on Censo Escolar, 2019 (INEP, 2020a).

Graphic 3 - Stage/modality enrollment distribution in PEI, ETI, and Regular schools (2019).

According to João Palma’s interview, this emphasis of PEI on High School is due to the influence of a “group of entrepreneurs” on the Department of Education who were interested in “rapidly building their workforce”:

And it starts right at the beginning of the government in 2011... the governor sets up a commission, which has some members of the Department of Education, that is, the secretary, the assistant, the Head of the Office and some businessmen. Which business? Itaú Unibanco, Fundação Lemann, Natura, Todos Pela Educação, in short, this business group. And an engineer from Pernambuco, who had implemented the full-time High School there under Jarbas Vasconcelos’ term, came here. [...]

I mean, I don’t know what High School will actually turn into… but, why did these businessmen insist on High School? To quickly form their workforce. That’s it! I remember that there was a moment when the students dropped out and Geraldo Alckmin called me. That day Herman wasn’t there. He certainly called him, as he wasn’t there, so, he called me. Then he asked, “Hey, Palma, what’s that? Are we starting with High School? Where did that come from?”, I said, “look, you need to talk to your secretary and the commission you created there, they were the ones who came up with this idea. My proposal was to start with the Elementary School since the Department of Education does not have early childhood education. So, I would start with the early years of elementary school because then I know what the family wants. They, the father and mother, want the child at school all day, so they can go to work. They take their kid to school in the morning and pick them up in the afternoon”, “so, Palma, but that was the aim”, I said, “well, governor, ((laughs)) if that was the aim, you were not heard, because they did the opposite”. Then, to patch things up, in the following year they included the Elementary School in the program too. But they continued with High School, continued insisting on High School and replicating Pernambuco standards.

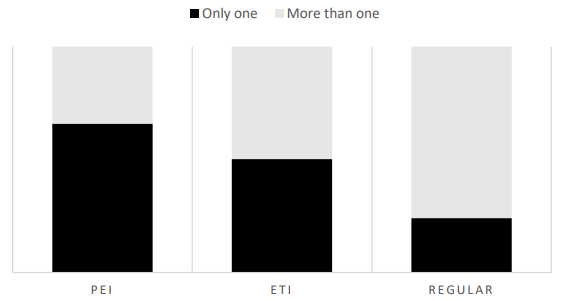

Considering the number of stages/modalities per school in each program, the difference in relation to regular schools in the state is more noticeable. More than 75% of regular schools offer more than one cycle/stage, and this figure drops to less than 50% in ETI and to less than 35% in PEI, as can be seen in Graphic 4.

Source: Organized by the authors, 2022, based on Censo Escolar, 2019 (INEP, 2020a).

Graphic 4 - Stage/modality offer between PEI, ETI, and Regular schools (2019).

This set of data points to a difference in the management complexity of schools in each of the programs compared to regular ones, indicating stratification of public education system offers. ICG, developed by INEP in 2014, aims to promote a large-scale-assessment of the results of contextual analysis in Brazilian schools. ICG takes 4 characteristics into account:

the size of the school;

the number of shifts;

the complexity of the stages offered by the school;

the number of stages/modalities offered.

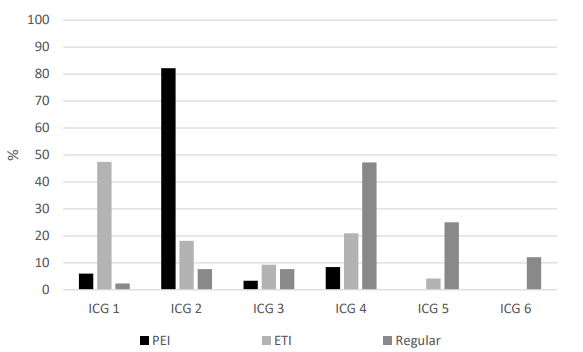

It is a scale that varies from 1 to 6, 1 being the lowest and 6 being the highest level of management complexity (INEP, 2014a). Graphic 5 shows the percentage of PEI, ETI, and regular schools according to ICG.

Source: Organized by the authors, 2022, based on ICG, 2019 (INEP, 2020c).

Graphic 5 - Percentage of schools by Management Complexity Index (ICG) for PEI, ETI, and Regular schools (2019).

It is possible to notice that PEI and ETI schools are concentrated in ICGs 1 and 2, indicating less management complexity, while regular schools are concentrated in ICGs 4, 5 and 6.

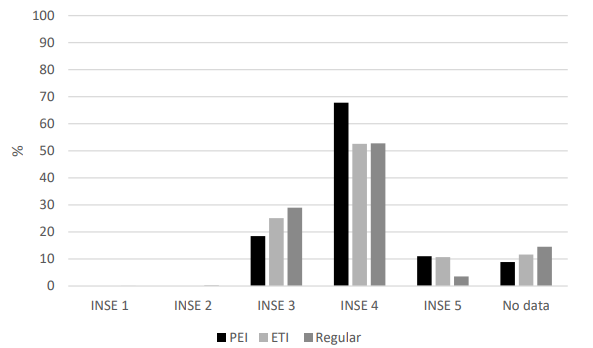

Another crucial context indicator is related to INSE, based on contextual questionnaires from SAEB and ENEM prepared by INEP in 2004 (INEP, 2014b, p. 6-7). INSE has eight levels; level I is the one with the worst student socioeconomic level. When analyzing PEI, ETI, and regular schools from INSE, we have the following result, described in Graphic 6.

Source: Organized by the authors, 2022, based on INSE, 2015 (INEP, 2016).

Graphic 6 - Percentage of schools by PEI, ETI, and Regular schools Socioeconomic Level Index (2015).

It is possible to verify that both PEI and ETI schools have a higher percentage of schools with students in INSE 5 than that verified for regular schools. While we have a little more than 3.5% of regular schools classified in INSE 5, this number rises to 10.70% in ETI schools, reaching 11% among PEIs. In the case of ETIs, this data goes against the legislation which regulates the program and indicates students in conditions of social vulnerability as priority assistance.

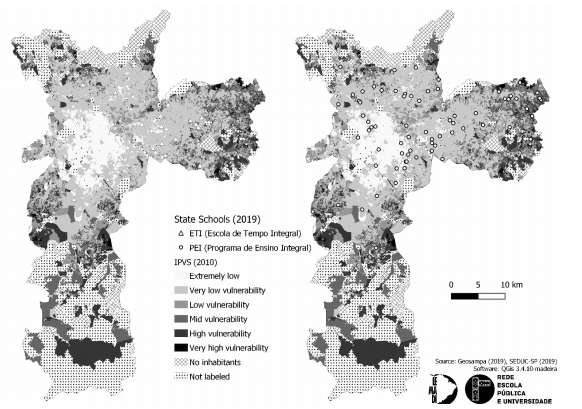

Another data used to understand the socioeconomic level of the school is related to the analysis of the location context. Studies carried out by authors such as Torres, Ferreira and Gomes (2005), Érnica and Batista (2012), among others, have analyzed how the effect of inequalities in the territory impacts school opportunities. From this, it becomes increasingly important to understand the spatial context of the schools, seeking to broaden the characterization of their students’ socioeconomic level. In order to achieve that, we present maps that correlate the location of PEI and ETI Schools in the city with the São Paulo Social Vulnerability Index (Índice Paulista de Vulnerabilidade Social - IPVS).43

The Figure 1 indicate that both PEI schools and ETIs are predominantly present in areas of lower social vulnerability in the city of São Paulo. Although it is not feasible to build a direct relationship between students’ enrollment and place of residence, INSE data, presented in the previous graphic, indicate that this is a possible correlation. In both cases, these programs are against the PNE 2014-2024 provisions regarding the expansion of Full-Time Education in the country, being even more serious in the case of ETIs since this spatial logic also contradicts the state legislation that regulates the program as mentioned before.

Source: Geosampa (2019), SEDUC-SP (2019). Following the editorial norms of the Magazine, the cartographic product is represented in black variations.

Figure 1 - PEI and ETI Schools according to the São Paulo Social Vulnerability Index (SEADE, 2010).

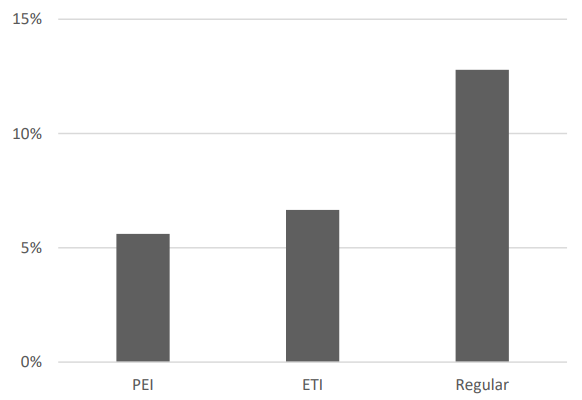

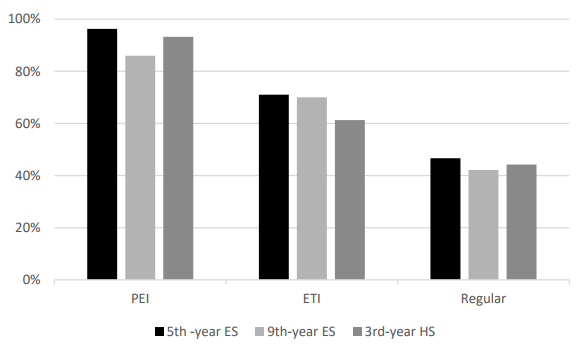

When we analyze another indicator, the age-grade disparity rate, which allows us to monitor the percentage of students older than the expected age for the year in which they are enrolled, we also find differences among the groups of schools analyzed. Data (Graphic 7) show that, in both programs, there is an age-grade disparity rate among enrolled students that is about 50% of that found, on average, in regular schools.

Source: Organized by the authors, 2022, based on Age-grade distortion rate per school (INEP, 2020b).

Graphic 7 - Average PEI, ETI, and Regular schools’ age-grade disparity rate (2019).

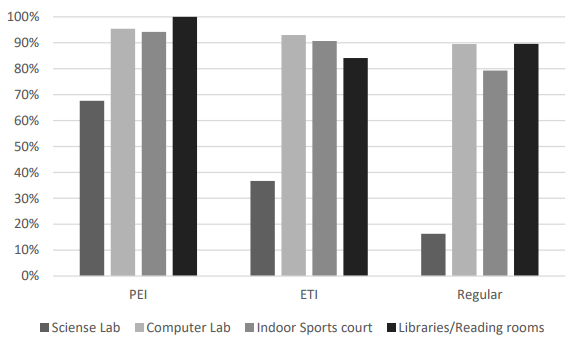

When we analyzed the data referring to school infrastructure, we found out that PEIs have better conditions compared to those found in ETI and regular ones. The difference regarding science laboratories is noteworthy: while less than 20% of regular schools have this resource, in PEI, more than 67% of the schools have this infrastructure, as can be seen in Graphic 8.

Source: Organized by the authors, 2022, based on School Census, 2019 (INEP, 2020a).

Graphic 8 - School infrastructure in PEI, ETI, and Regular schools (2019).

Therefore, it is possible to verify that despite having little participation in the number of enrollment and schools, the programs analyzed produced an offer stratification with possible impacts on the expansion of the inequalities in the state public education system, since PEI and ETI schools have better conditions regarding management complexity, age-grade disparity, and school infrastructure into account. Such stratification of the offer can be seen as a policy option, since such programs were seen as impossible to be universalized from their beginning and could cause effects on public education system inequalities, mainly by not serving the most vulnerable students.

As there is no explanation in SEDUC-SP documents when it comes to choosing the schools that will participate in the Programs, speculations about the reasons are open. From our perspective, one of these hypotheses may lie in the centrality that the result-management mindset has conducted the educational policies in the state public-education system of São Paulo in recent decades. As stated in the second section of this text, if the first education program (ETI) did not have a connection with this mindset, PEI is consolidated as a program that links the school hour extension to the production of educational results, which is seen as an improvement in IDESP in São Paulo. From our perspective, the very change in working hours extension programs, with the progressive replacement of ETI by PEI, is an important indicator of the centrality that this mindset has in the conduction of the educational policy.

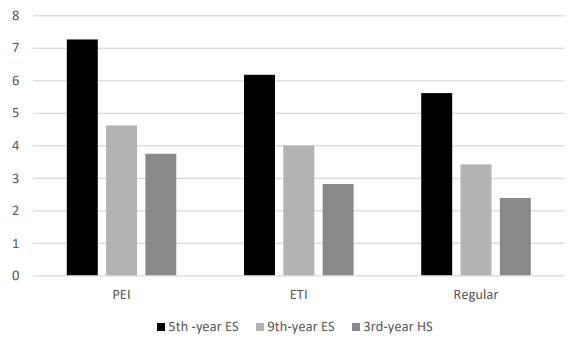

This hypothesis on the centrality of management for results and its effects on the conduction of education policies can be problematized from Graphics 9 and 10, which tackle the average performance of schools in IDESP. The best results are obtained by PEI schools.

Source: Organized by the authors, 2022, based on SEDUC-SP, 2019.

Graphic 9 - Average IDESP of schools for the group of PEI, ETI, and Regular schools (2019).

Note: For 2019, the IDESP state averages were: 5th year Elementary School 5.64; 9th year Elementary School 3.51; 3rd year High School 2.44. Source: Organized by the authors, 2022, based on SEDUC-SP, 2019.

Graphic 10 - Schools whose IDESP is above state schools’ average, PEI, ETI, and Regular schools (2019).

Among the arguments expressed by SEDUC-SP to explain this difference in results, PEI schools’ management mindset stands out with a focus on goals and management devices. However, we consider that this single variable is not enough to understand such differentiation. Since the implementation of PEI, the government of São Paulo has been using the results of SARESP and IDESP to propagate an improvement in educational quality, conceived in a hegemonic way in the New Public Management (NPM) in the sense of improving the results measured in standardized assessments (SEDUC-SP, 2015; 2017). Pointing to PEI schools as a model to be followed, the government relates, mechanically and simplistically, the expansion of the school hours to the results achieved in the educational indicators, omitting the unique condition that these schools have compared to the others.

However, in 2016, the Tribunal de Contas do Estado de São Paulo44 (TCE-SP) published a report analyzing, at random, school of state public-education system that offered full-time education (ETIs and PEIs) across the state. TCE points out some specific PEI conditions that can complexify the explanation of the results mentioned above: higher investment in infrastructure; SARESP continuous mock tests dynamics; more participation of families in their children’s academic education; the constant presence of Teaching Supervisors (up to twice as many as the number in part-time schools); a high number of school transfers in the first two years of the Program, corresponding to 20 and 15%, respectively.

The inspection carried out by TCE-SP showed that the schools in the Program acquired a configuration equivalent to those with the best performances in IDESP, identified by Minuci and Arizono (2009). According to the authors, the schools with the best IDESP scores “are in less vulnerable areas, with a higher proportion of students from families with better socioeconomic conditions and students with better academic performance” (Minucci and Arizono, 2009, p. 146). Such analysis leads us to question whether the choice of the school participating in the program, since no new schools were built, is not being made in accordance with these more adequate conditions for the production of educational results to the detriment of more equitable opportunities for school hour extension to students of state public-education system of São Paulo. If this is the objective, what are the consequences in the mid-and long term, for the expansion of offer stratification and the increase of the inequalities inside the state public-education system? Wouldn’t we be facing an apparent contradiction in which the extension of school time for some would represent, to a certain extent, less right to education for many others? In this regard, in an interview, João Palma stated that, following the implementation process in São Paulo of the High School model (PEI) inspired by the Integral Education model developed in Pernambuco, it was possible to identify signs of this stratification and increase in intra-public-education system inequalities:

(...) I talked to several colleagues from the University of Pernambuco, and even people there who worked for the Department of Education in previous governments, Arraes, etc., Eduardo Campos himself, and they told me, “Here in Pernambuco, it is creating a new sort of elite, it is a sort of elite in the middle of the working class”. I said, “yeah, they’re training the guys who will ((laughs)) oppress the working class themselves, even though they’re part of it”. And, effectively, São Paulo does not have a different outcome.

Thus, it is possible to verify that one of the effects of the implementation of the Full-Time Teaching Programs in the São Paulo’s state public-education system was the expansion of the offer stratification, creating unequal conditions for schooling. Such stratification cannot be seen as an error in the conduct of policy. As we have seen, it is one of its foundations, especially when one assumes that it is not possible to universalize it. As a hypothesis for future investigations, we think that such offer stratification could be seen as a step toward the constitution of a hidden quasi-market in the terms proposed by Costa and Kolinski.

Educational quasi-markets can be assumed as the result of a differentiated school offer, in which the choices of school establishments are adjusted. Quasi-market policies would work from mechanisms to encourage choice, set by offering a menu of schools to students and their parents and by establishing organized systems of information about schools and such choices. (Costa and Kolinsky, 2012, p 196)

If there is a clear defense and regulation of the school choice policy in different countries, which would be evidence of the existence of a quasi-market mindset mediating the relationship between school offer and demand, in the Brazilian case, according to the authors, what we have is a hidden quasi-market in the absence of an explicit defense of school choice policy. Thereby,

The process seems to accentuate characteristics that promote social inequality, increasing the chances of those who already enjoy some competitive advantage, often associated with the heritage of social relationships. Thus, we use the concept of quasi-market as an analytical resource to understand the phenomenon of competition for public schools that cannot be characterized as “elite” or “excellence” in the Brazilian context. (Costa and Kolinsky, 2012, p 197)

We believe that if this mindset is kept, this is an important way to assess whether such programs can trigger the expansion of school inequalities in the territory of São Paulo, which we intend to discuss in future research.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The Full-Time Teaching programs, put into dynamics in the state public-education system of São Paulo in 2005 and emerged in the wake of a perspective that intends between welfare and social protection, underwent important changes from 2011 onward due to the centrality that management-result policies assume in the state schools of São Paulo. It is in this context that we analyze the similarities and differences between the ETI and PEI Programs, demonstrating how, at the present time, they have very similar offer characteristics to each other and are different from those found in regular schools in the state.

Data show that both ETI and PEI schools have less management complexity compared to regular schools in São Paulo, with fewer enrollments, classes, stages, and modalities. In addition, they are located and serve students with lower social vulnerability. All these data indicate that the programs are in the opposite direction of PNE 2014-2024. The lack of explicit information on the criteria for choosing schools and for expanding the programs allows us to build hypotheses about the intentions adopted by both policies concerning the improvement of Educational Indexes in the state, even if this implies expanding the stratification of school offer and inequalities.

Furthermore, this stratification of the offer produced by both programs may imply the constitution of what has been called a hidden quasi-market. Being recognized by the communities as schools with better teaching-learning conditions, the Full-Time Teaching schools would be disputed by the families who would see there, therefore, an opportunity for differentiation in the schooling process of their children. The absence of equity policies (a system of permanence grants for more vulnerable students, for example) would centralize this competition in the family effort, contributing to the process of inequalities’ reproduction. Families with better socioeconomic conditions would have access to this privileged school compared to the others in the state. Thus, a vicious cycle is formed and contributes to reproducing school privileges (minimum as they may be), while different conditions of schools and the socioeconomic profile of those enrolled would contribute to the production of educational results and indices.

Because of this reproduction of inequalities dynamics through the stratification of offer, we reaffirm the importance that the debate on Integral Education and not only on Full-Time Teaching occurs by taking the complexity of the theme into account, observing the different experiences carried out in Brazil and around the world, and talking to school communities. In these terms, it is necessary to build Integral Education as a right, creating the material conditions so that all people, who so wish, can have access to it. This concept must be aligned with the challenge of building an equitable public education system in the country and cannot be configured as another stage of educational inequalities reproduction, as seen in the case of São Paulo.

REFERENCES

BABALIM, V. S. Escola de tempo integral: relato de uma experiência na rede estadual de ensino de São Paulo. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) − Universidade Nove de Julho, São Paulo, 2016. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília: Congresso Nacional, 1996a. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 9.424, de 24 de dezembro de 1996. Dispõe sobre o Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento do Ensino Fundamental e de Valorização do Magistério, na forma prevista no art. 60, § 7º, do Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias, e dá outras providências. Brasília: Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos, 1996b. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9424.htm . Acesso em: 14 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto n. 6.094, de 24 de abril de 2007. Dispõe sobre a implementação do Plano de Metas Compromisso Todos pela Educação, pela União Federal, em regime de colaboração com municípios, Distrito Federal e Estados, e a participação das famílias e da comunidade, mediante programa e ações de assistência técnica e financeira, visando a mobilização social pela melhoria da qualidade da educação básica. Brasília: Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos, 2007a. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2007/decreto/d6094.htm . Acesso em: 14 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Portaria normativa interministerial n. 17, de 24 de abril de 2007. Institui o Programa Mais Educação, que visa fomentar a educação integral de crianças, adolescentes e jovens, por meio do apoio a atividades socioeducativas no contraturno escolar. Brasília: MEC, 2007b. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/arquivos/pdf/mais_educacao.pdf . Acesso em: 14 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 11.494, de 20 de junho de 2007. Regulamenta o Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica e de Valorização dos Profissionais da Educação - FUNDEB, de que trata o art. 60 do Ato das Disposições Constitucionais Transitórias; altera a Lei n o 10.195, de 14 de fevereiro de 2001; revoga dispositivos das Leis n. 9.424, de 24 de dezembro de 1996, 10.880, de 9 de junho de 2004, e 10.845, de 5 de março de 2004 e dá outras providências. Brasília: Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos, 2007c. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2007/lei/l11494.htm . Acesso em: 14 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Decreto n. 7.083, de 27 de janeiro de 2010. Dispõe sobre o Programa Mais Educação. Brasília: Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos, 2010. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2010/decreto/d7083.htm . Acesso em: 14 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 13.005, de 2014. Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação (2014-2024). Brasília: Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos, 2014. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2014/lei/l13005.htm#:~:text=LEI%20N%C2%BA%2013.005%2C%20DE%2025,Art . Acesso em: 14 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Medida Provisória n. 746, de 22 de setembro de 2016. Institui a Política de Fomento à Implementação de Escolas de Ensino Médio em Tempo Integral, altera a Lei n º 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, e a Lei n º 11.494 de 20 de junho 2007, que regulamenta o Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica e de Valorização dos Profissionais da Educação, e dá outras providências. Brasília: Presidência da República, Secretaria-Geral, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos, 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2016/Mpv/mpv746.htm . Acesso em: 14 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n. 13.415, de 16 de fevereiro de 2017. Altera as Leis n º 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, e 11.494, de 20 de junho 2007, que regulamenta o Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica e de Valorização dos Profissionais da Educação, a Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho - CLT, aprovada pelo Decreto-Lei nº 5.452, de 1º de maio de 1943, e o Decreto-Lei nº 236, de 28 de fevereiro de 1967; revoga a Lei nº 11.161, de 5 de agosto de 2005; e institui a Política de Fomento à Implementação de Escolas de Ensino Médio em Tempo Integral. Brasília: Presidência da República, Secretaria-Geral, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos, 2017a. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2017/Lei/L13415.htm . Acesso em: 14 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Portaria n. 1.570, de 20 de dezembro de 2017. Brasília: MEC, 2017b. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/historico/PORTARIA1570DE22DEDEZEMBRODE2017.pdf . Acesso em: 14 set. 2020. [ Links ]

CAIUBY, B. B.; BOSCHETTI, V. R. Uma escola de tempo integral. Laplage em revista. Sorocaba, v. 1, n. 1, p. 84-97, jan./abr., 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://laplageemrevista.editorialaar.com/index.php/lpg1/article/view/190 . Acesso em: 17 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

CAVALIERE, A. M. Tempo de escola e qualidade na educação pública. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 28, n. 100, p. 1015-1035, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302007000300018 [ Links ]

CAVALIERE, A. M. Verbete: educação integral. In: OLIVEIRA, D. A.; DUARTE, A. M. C; VIEIRA, L. M. F. (org.). Dicionário: trabalho, profissão e condição docente. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 2010. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://gestrado.net.br/verbetes/educacao-integral/ . Acesso em: 29 jun. 2020. [ Links ]

CAVALIERE, A. M. Escola pública de tempo integral no Brasil: filantropia ou política de estado? Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 35, n. 129, p. 1205-1222, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302014142967 [ Links ]

COSTA, M. da.; KOLINSKY, M. C. Escolha, estratégia e competição por escolas públicas. Pro-posições, Campinas, v. 23, n. 2, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-73072012000200013 [ Links ]

DIB, M. A. B. O programa escola de tempo integral na região de assis: implicações para a qualidade do ensino. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) − Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciência, Marília, 2010. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://hdl.handle.net/11449/104825 . Acesso em: 17 jul. 2022. [ Links ]

ÉRNICA, M.; BATISTA, A. A. G. A escola, a metrópole e a vizinha vulnerável. Cadernos de Pesquisa, v. 42, n. 146, p. 640-666, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742012000200016 [ Links ]

FAVERI, R. C. C. A escola de tempo integral no estado de São Paulo: um estudo de caso a partir do olhar dos profissionais das oficinas curriculares 2013. 136 p. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Campinas, Campinas, SP, 2013. [ Links ]

FUNDAÇÃO SEADE. Índice Paulista de Vulnerabilidade Social. São Paulo: SEADE, 2010. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA. Nota técnica nº 040/2014. Brasília: MEC, 2014a. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://download.inep.gov.br/informacoes_estatisticas/indicadores_educacionais/2014/escola_complexidade_gestao/nota_tecnica_indicador_escola_complexidade_gestao.pdf . Acesso em: 14 set. 2020. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA. Nota técnica sobre o Indicador de Nível Socioeconômico das Escolas de Educação Básica (INSE). Brasília: MEC, 2014b. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://download.inep.gov.br/informacoes_estatisticas/indicadores_educacionais/2015/nota_tecnica/nota_tecnica_inep_inse_2015.pdf . Acesso em: 14 set. 2020. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA. Indicador de Nível Socioeconômico das Escolas da Educação Básica (INSE) - 2015. Brasília: MEC, 2016. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA. Censo Escolar - 2019. Brasília: MEC, 2020a. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA. Taxa de distorção idade-série por escola. Brasília, MEC, 2020b. [ Links ]

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA. Índice de complexidade de gestão da escola (ICG) − 2019. Brasília, MEC, 2020c. [ Links ]

LARROYO, F. História geral da pedagogia. São Paulo: Mestre Jou, 1974. [ Links ]

MACHADO, L. M. Politecnia, escola unitária e trabalho. São Paulo: Cortez, 1989. [ Links ]

MINUCI, E. G.; ARIZONO, N. Tipologia de escolas que alcançaram as metas do IDESP. São Paulo em Perspectiva, São Paulo, Fundação Seade, v. 23, n. 1, p. 135-148, 2009. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://produtos.seade.gov.br/produtos/spp/v23n01/v23n01_10.pdf . Acesso em: 27 jul. 2020. [ Links ]

MOTA, S. M. C. Escola de tempo integral: da concepção à prática. 2008. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) − Universidade Católica de Santos, Santos, SP, 2008. [ Links ]

PARO, V. H. A educação como exercício do poder: crítica ao senso comum em educação. 4. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2018. [ Links ]

SECRETARIA DA EDUCAÇÃO DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO. Novo modelo de Escola de Tempo Integral melhora índices do ensino médio em 26%. São Paulo: SEDUC-SP, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.educacao.sp.gov.br/noticias/novo-modelo-de-escola-de-tempo-integral-melhora-em-26-aprendizagem-no-ensino-medio/ . Acesso em: 06 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

SECRETARIA DA EDUCAÇÃO DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO. Ensino médio em tempo integral tem avanço histórico de 73,4% no IDESP. São Paulo: SEDUC-SP, 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.educacao.sp.gov.br/noticias/ensino-medio-em-tempo-integral-tem-avanco-historico-de-73-4-no-IDESP/ . Acesso em: 06 mar. 2018. [ Links ]

SECRETARIA DA EDUCAÇÃO DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO. Governo de SP anuncia mais de 400 escolas no Programa de Ensino Integral e triplica unidades no estado. São Paulo: SEDUC-SP, 2020. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.educacao.sp.gov.br/noticias/governo-de-sp-anuncia-mais-400-escolas-no-programa-de-ensino-integral-e-triplica-unidades-no-estado/ . Acesso em: 08 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Resolução SE n. 89, de 09 de dezembro de 2005. Dispõe sobre o Projeto Escola de Tempo Integral. São Paulo: SEE-SP, 2005. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://siau.edunet.sp.gov.br/ItemLise/arquivos/89_05.HTM?Time=02/05/2016%2022:00:32 . Acesso em: 26 mai. 2020. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Decreto n. 57.571, de 2 de dezembro de 2011. Institui, junto à Secretaria da Educação, o Programa Educação − Compromisso de São Paulo e dá providências correlatas. São Paulo: Assembleia Legislativa do Estado de São Paulo, 2011. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/decreto/2011/decreto-57571-02.12.2011.html . Acesso em: 26 mai. 2020. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Lei Complementar n. 1.164, de 4 de janeiro de 2012. Institui o Regime de dedicação plena e integral - RDPI e a Gratificação de dedicação plena e integral - GDPI aos integrantes do quadro do Magistério em exercício nas escolas estaduais de ensino médio de período integral, e dá providências correlatas. São Paulo: Assembleia Legislativa do Estado de São Paulo, 2012a. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/lei.complementar/2012/lei.complementar-1164-04.01.2012.html . Acesso em: 26 mai. 2020. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Lei Complementar n. 1.191, de 28 de dezembro de 2012. Dispõe sobre o Programa Ensino Integral em escolas públicas estaduais e altera a Lei Complementar nº 1.164, de 2012, que instituiu o Regime de dedicação plena e integral − RDPI e a Gratificação de dedicação plena e integral − GDPI aos integrantes do Quadro do Magistério em exercício nas escolas estaduais de ensino médio de período integral, e dá providências correlatas. São Paulo: Assembleia Legislativa do Estado de São Paulo, 2012b. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.al.sp.gov.br/repositorio/legislacao/lei.complementar/2012/lei.complementar-1191-28.12.2012.html . Acesso em: 26 mai. 2020. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Diretrizes do Programa de Ensino Integral. São Paulo: SEE-SP, 2014a. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.educacao.sp.gov.br/a2sitebox/arquivos/documentos/342.pdf . Acesso em: 26 mai. 2020. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Resolução SE n. 68, de 17 de dezembro de 2014. Dispõe sobre o processo de avaliação dos profissionais que integram as equipes escolares estaduais do Programa Ensino Integral. São Paulo: SEE-SP, 2014b. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://siau.edunet.sp.gov.br/ItemLise/arquivos/68_15.HTM?Time=10/08/2021%2012:12:30 . Acesso em: 10 ago. 2021. [ Links ]

SÃO PAULO. Resolução SE n. 68, de 12 de dezembro de 2019. Altera a Resolução SE n. 52, de 02-10-2014, que dispõe sobre a organização e o funcionamento das escolas estaduais do Programa Ensino Integral - PEI e dá providências correlatas. São Paulo: SEE-SP, 2019a. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://siau.edunet.sp.gov.br/ItemLise/arquivos/68_19.HTM?Time=16/08/2021%2016:42:32 . Acesso em: 10 ago. 2021. [ Links ]

SILVA, T. M. da. Educação integral ou parcial? Reflexões para além da extensão do tempo. Curitiba: Appris, 2019. [ Links ]

TORRES, H. G.; FERREIRA, M. P.; GOMES, S. Educação e segregação social: explorando as relações de vizinhança. In: MARQUES, E.; TORRES, H. G. (org.). São Paulo: segregação, pobreza e desigualdade. São Paulo: Editora do Senac, 2005, p. 123-142. [ Links ]

TORRES, T. A. R. O projeto Escola de Tempo Integral na rede estadual de São Paulo: considerações acerca do direito à educação de qualidade. 2016. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Educação, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2016. [ Links ]

TRIBUNAL DE CONTAS DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO. Relatório de fiscalização de natureza operacional sobre os modelos de educação em período integral existentes na Rede Pública Estadual de Ensino. São Paulo: TCE-SP, 2016. [ Links ]

VALENTIM, G. A. Programa Ensino Integral e Escola de Tempo Integral no estado de São Paulo: permanências e mudanças. 2018. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Faculdade de Ciência e Tecnologia, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Presidente Prudente, SP, 2018. [ Links ]

1 Initially presented as Provisional Measure n. 746, on September 22nd, 2016 (Brasil, 2016), by President Michel Temer, the Reform was approved by Law n. 13,415, on February 16th, 2017 (Brasil, 2017a).

2 Although there is an attempt of SEDUC-SP to classify these programs as “Integral Education” policies when we turn to the conceptions and definitions of Integral Education - as we briefly discussed in the first part of the text - we verify that these programs do not present the main elements that characterize Integral Education proposals and are programs based on the extension of the school hours, as the names of the programs indicate, and not properly structured programs based on the principles of Integral Education. Thus, from this point onwards, we will opt to call it “Programas de Ensino em Tempo Integral” (Full-Time Teaching Programs [T.N.]) to refer to both programs of the state public-education system of São Paulo analyzed in this article.

3 Throughout this article, public policies will be cited in Portuguese and their free translations into English will be listed in the footnotes followed by [T.N.] (Translation Note). It corresponds to Full-time School. [T.N.].

7 We can comprehend the stratification of this offer as the differentiation of schooling conditions which were analyzed from variables such as the number of classes and enrollments, distribution of shifts, cycles/stages/modalities offer, age-grade distortion, and socioeconomic level index (INSE) and management complexity.

12 Within the scope of the research “Política educacional na rede estadual paulista (1995 a 2018)” (“Educational policy in the state public-education system of São Paulo (1995 to 2018)” [T.N.]), the researchers Márcia Aparecida Jacomini, Fernando Cássio, and Eliane Bruini who are part of the project conducted interviews with Secretaries of Education and employees who worked at SEDUC-SP for a more comprehensive understanding and analysis of the educational policy adopted in the period under analysis. Interviews were conducted with: João Cardoso Palma Filho, Assistant Secretary from 2011 to 2013 (held on 11/27/2020, lasting 144 minutes); Herman Voorwald, Secretary of Education from 2011 to 2015 (held on 11/27/2020, lasting 119 minutes); with José Renato Nalini, Secretary of Education between 2016 and 2018 (held on 12/01/2020, lasting 88 minutes); with Valéria de Souza, who worked under Secretary Herman Voorwald’s administration, and was responsible for the articulation of São Paulo Education Commitment Program and being the manager of the Programa Ensino Integral (PEI) (held on 12/07/2020, lasting 127 minutes); with Maria Helena Guimarães de Castro, Secretary of Education between 2007 and 2009 (held on 01/15/2021, lasting 78 minutes); with Nayra Karam, Secretary’s of Education Advisor from March 2012 to June 2015 (interview held on 01/15/2021, lasting 49 minutes); and with Gabriel Chalita, Secretary of Education from 2002 to 2006 (in the impossibility of responding to the request to grant an interview, the former secretary answered questions sent to them by email on 02/09/2021). Only Rose Neubauer, Secretary of Education from 1995 to 2002, refused to be interviewed. With the permission of the interviewees, all the interviews were recorded and later transcribed by Simone Passos from Quality Transcriptions, so that the material was available for analysis by the researchers who are part of the project. Throughout this article, we bring excerpts from the transcripts of some of these interviews to compose our investigation and analysis of the effects of Full-Time Teaching Programs on the dynamics of the state public-education system of São Paulo.

19 Fund for the Maintenance and Development of Basic Education and for Valuing Education Professionals [T.N.], Law n. 11,494, on June 20, 2007 (Brasil, 2007c). It came to replace the FUNDEF (Fund for the Maintenance and Development of Elementary School and the Valorisation of Teaching), instituted by Law n. 9,424, December 24, 1996 (Brasil, 1996b). which was effective throughout the country from January 1, 1998, until December 31, 2006.

20 Education Development Plan [T.N.]. It was introduced alongside the Plano Metas Compromisso Todos pela Educação [All for Education Goal Commitment Program [T.N.]], established by Decree-Law n. 6094 (Brasil, 2007a). It took fifteen years to complete but ended up discontinued before that period.

21 The program was instituted by the inter-ministerial normative ordinance n. 17, April 24, 2007 (Brasil, 2007b) and regulated by Decree n. 7,083, of January 27, 2010. (Brasil, 2010)

22 National Education Plan [T.N.]. Established by law n. 13,005, from June 25, 2014. (Brasil, 2014)

24 Established by Resolution SE n. 89, on December 9, 2005. (São Paulo, 2005)

25 São Paulo Education Commitment Program [T.N.] was established by Decree n. 57,571, on December 2, 2011. (São Paulo, 2011)

26 Established by Complementary Law n. 1,164, January 4, 2012 (São Paulo, 2012a), amended by Complementary Law n. 1,191, December 28, 2012. (São Paulo, 2012b)

29 The Full and Integral Dedication Bonus (GDPI was also established by Complementary Law n. 1,164, on January 4, 2012 (São Paulo, 2012a), amended by Complementary Law n. 1,191, on December 28, 2012. (São Paulo, 2012b)

30 “To be part of the Full-Time Teaching Program, the school must under São Paulo state management, must have adequate spaces for the operation of laboratories and cafeterias, in addition to having at least ten classes of students enrolled and who are supported by families to study in full-time.” (Silva, 2019, p. 59)

31 Information available in Administrative Process SE 2,737/2014 (Agreement - São Paulo Education Commitment Program), obtained via the Access to Information Law, eSIC - Protocol: 342391810800. We thank Professor Fernando Cássio (UFABC) for making the document available.

40 Interview carried out within the scope of the FAPESP Project “Política educacional na rede estadual paulista (1995 a 2018)”, on 11/27/2020 (144 minutes).

41 Interview carried out within the scope of the FAPESP Project “Política educacional na rede estadual paulista (1995 a 2018)”, on 11/27/2020 (119 minutes).

42 Interview carried out within the scope of the FAPESP Project “Política educacional na rede estadual paulista (1995 a 2018)”, on 12/07/2020 (127 minutes).

Received: March 17, 2021; Accepted: August 31, 2021

texto em

texto em