Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1413-2478versión On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.27 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub 24-Nov-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782022270114

Article

Professional empowerment of literacy teachers in collaborative virtual sessions

IUniversidade Federal do Tocantins, Palmas, TO, Brazil.

IISecretaria Municipal de Educação de Palmas, Palmas, TO, Brazil.

In this article, two interconnected educational situations are investigated. Both were carried out in the remote teaching of a subject for the initial training of literacy teachers. The first situation corresponds to virtual sessions with an exposition by a schoolteacher about her own literacy practice implemented in a public school. The second corresponds to the production of reflective reports about these sessions written by teachers in initial training. A qualitative approach is adopted for data analysis and the study is characterized as participatory research. The latter is justified by the nature of the collaborative work responsible for the mutual empowerment of those involved. Among the results produced, there is the fact that the participants have given new meaning to the negative representations shared by them about the educational institutions represented in the research.

KEYWORDS remote learning; reflective writing; teacher education; university

Neste artigo, duas situações educativas interconectadas são investigadas. Tais situações ocorreram no ensino remoto de um componente curricular para formação inicial de alfabetizadoras. A primeira corresponde a sessões virtuais com exposição de uma professora sobre a própria prática alfabetizadora implementada numa escola pública. A segunda, à produção de relatos reflexivos sobre as referidas sessões escritos pelas professoras em formação inicial. Assume-se a abordagem qualitativa para a análise dos dados e caracteriza-se o estudo como uma pesquisa participante. Essa última se justifica pela natureza do trabalho colaborativo responsável pelo empoderamento mútuo dos envolvidos. Entre os resultados produzidos, há o fato de os participantes terem ressignificado as representações negativas compartilhadas por eles em torno das instituições educativas representadas na pesquisa.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE ensino remoto; escrita reflexiva; formação de professores; universidade

En este artículo se investigan dos situaciones educativas interrelacionadas. Tales situaciones se llevaron a cabo en la modalidad de educación a distancia del componente curricular para la formación inicial de alfabetizadoras. La primera corresponde a sesiones virtuales con exposición de una maestra sobre su propia práctica alfabetizadora implementada en una escuela pública. La segunda corresponde a la elaboración de informes reflexivos sobre estas sesiones redactados por docentes en formación inicial. Se adopta un enfoque cualitativo para el análisis de datos y el estudio desde la investigación participativa. Esto último se justifica por la naturaleza del trabajo colaborativo responsable del mutuo empoderamiento de los involucrados. Entre los resultados producidos, se encuentra el hecho de que los participantes han dado un nuevo significado a las representaciones negativas que comparten sobre las instituciones educativas representadas en la investigación.

PALABRAS CLAVE educación virtual; formación del profesorado; escritura reflexiva; universidad

INTRODUCTION

The article discusses the collaborative work developed between a school teacher and a university professor in the pre-service education of alphabetization teachers.1 The main goal of the present study is to contribute to the teaching practices in these institutions, which implies bringing forth the productive aspects as well as the sensitive areas of the pedagogical work that was conducted. Therefore, the discussion concentrates mostly on the pre-service education of literacy teachers.

The context of the discussion comprehends synchronous sessions of nightly remote classes for the Teaching Degree in Pedagogy offered at Universidade Federal do Tocantins (UFT), Campus in Palmas, during the pandemic triggered by the SARS-CoV-2, the cause of Covid-19. The article consists of a critical analysis of the educational and collaborative work developed in the sessions, assessed by the participants as productive pedagogical experiences that were made possible by an adverse situation.

The sessions focused on children's literacy experience. A professor, an alphabetization teacher and three classes of pre-service teachers participated in the sessions for three consecutive academic terms. The work was part of the activities for the course Alphabetization and Literacy2 taught by that professor. Naturally, the situation allowed the school teacher to take on the role of guest and prompted the title Dining with the Alphabetization Teacher for the meetings.

In pre-service education, alphabetizing children is a very challenging issue for several reasons, among which two are highlighted in this article:

persistent controversies regarding the methods and theoretical approaches chosen to alphabetize children; and

debilities in the pre-service education of alphabetization teachers due to generalist teaching degrees and to traces of their poor basic schooling.

These reasons were aggravated, respectively, by the recent publication of the national policy for alphabetization (Brasil, 2019) and by the temporary changes in the guidelines for academic activities at university due to adoption of remote teaching during the pandemic.

The recognized importance of the virtual dinners as well as highlighted challenges regarding alphabetization reinforce the intention to contribute to the teaching practices in Brazilian teaching degrees and underscore the importance of collaborative work between schools and universities — an experience that could extend beyond the pandemic. The experience analyzed here reveals the production of sustainable knowledge capable of guiding the work of professors and teachers. This means the co-construction of specialized knowledge based on the dialogue between representatives for those educational institutions. An indicative of that process is that this article was written by both the professor and the school teacher.

The present study fits the scope of Applied Linguistics, being developed by the research group Práticas de Linguagens (PLES — UFT/CNPq). The study is also characterized as a participatory action research, due to the participants’ engagement in the collaborative virtual sessions, that sought to meet a demand shared by the participants for continued professional development, which started with sharing and developing knowledge for children's alphabetization practices.

The research data was generated through the analysis of reflective reports written by pre-service teachers to problematize, systematize, and develop theoretical and practical issues discussed in the dinners. The analysis of the documents relied on scientific literature selected from the alphabetization studies in Brazil (Cagliari, 2007; Freire, 2016; Silva, 2019), literacy studies (Magalhães and Celani, 2005; Signorini, 2006a, 2006b; Silva, 2014; 2020; 2021), and higher education studies (Demo, 2011; 2015), as well as on information about the virtual sessions presented by the authors. Therefore, a qualitative approach (Silva, 2011) was adopted in the analysis, informed by the linguistic analysis of the verbal materiality (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014).

This article is organized in three main sessions, in addition to this introduction, the final remarks and the references. The first presents the theoretical bases that supported the pedagogical work conducted in the synchronous sessions. The second describes an adverse institutional context for pre-service alphabetization teachers. The third presents data analyses as evidence of the empowerment of participants during the dinners.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION OF THE WORK

Underlying the pedagogical work in the required course Alphabetization and Literacy is the understanding that universities are spaces of knowledge construction and that researching is a constitutive element of being a professor. Therefore, the critical attitude about one's own work becomes indispensable for professors in pre-service teacher education, which are called teaching degrees in Brazil.

That indispensability is due to the tendency of constructing teaching and pre-service teacher education for basic school as objects of scientific investigation for teaching degree professors (Silva, 2011). The relevance of an equally critical attitude for school teachers is added to the argument, thus universities must inspire and influence the undergraduate students. The mere reproduction of knowledge is unproductive, both for university activities and for the educational work done at schools, after all investigating is necessary to identify and to solve problems or to overcome challenges within the agitated path of teaching, or external ones, brought from social spaces (Silva, 2020; 2021).

In this perspective, such educational institutions are spaces of authorship, words used by Demo (2015, p. 8; our translation) to name “[…] the ability to research and to elaborate knowledge in the double sense of an epistemological strategy to produce knowledge and the pedagogical educational condition […]: educate better, producing knowledge with authorship […]” (original highlights). Previously, the author also claimed the need to change teachers’ concept and practices, since they are not defined “[…] by classes, but by authorship […]” (Demo, 2011, p. 21, our translation).

The virtual dinners with an alphabetization teacher were characterize as a collaborative activity aligned with the concept of university described before. Therefore, the teaching degrees are not only responsible for pre-service teacher education, they also need to be involved in the teaching practices at school. To that end, the notion of dialogue presented by Freire (2016) to guide the process of alphabetization of adults was assumed throughout the meetings in the pursuit of the empowerment of the participants: the professor, the alphabetization teacher and the pre-service teachers.

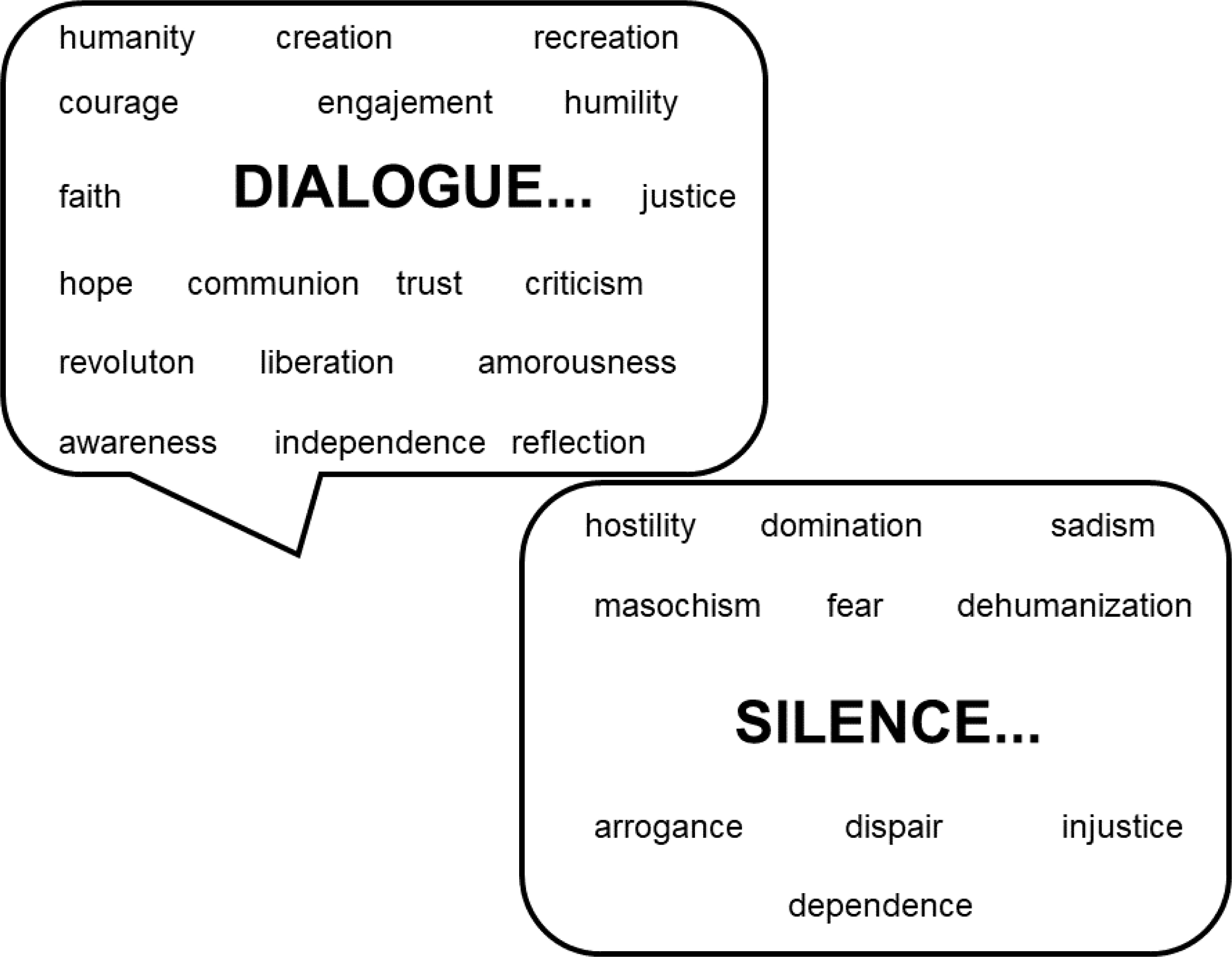

A synthesis of the notion of dialogue constructed by Freire (2016), opposed to what he conceived as anti-dialogue or silence, is presented in Figure 1. The lexical choices that define the concepts used by the author are shown separately.

The words that define dialogue demand a humbler attitude from university representatives before the work conducted at schools. There is an arrogance that is frequently noticed in the dominating attitude that tells teachers what they must or must not do in their workplaces. This shows not only that teachers “[…] do not see themselves as capable of producing their own knowledge […]” as claimed by Demo (2011, p. 100; our translation), but universities tend not to recognize them as producers of specialized knowledge.

With faith in the commitment of participants and hope to break with the reproduction of silence, the activity sought the engagement and the communion among the participants in the virtual dinners as well as the shared responsibility for the mutual development of amorousness, trust, courage, independence, and justice. In that effort, criticism and some small revolutions were also cultivated in the participants’ professional practices. Making visible the participation of the alphabetization teacher and the undergraduate students in addition to enabling a harmonious interaction with the professor regarding teaching practices at schools and universities allow for the claim that efforts were made to avoid silence and trigger empowerment, in the sense proposed by Freire and Macedo (1990). The immediate contributions of this work will be illustrated in the analysis section of this article.

Another characteristic of dialogue is reflection. This is a very stimulated activity in contexts of pre-service education, with practical consensus on the relevance of pre-service education of critical educators who can “[…] reflect on their practices and about their students’ education […]” (Magalhães and Celani, 2005, p. 146; our translation). In Applied Linguistics, research is conducted on the use of pedagogical instruments to foster in teachers the habit of reflecting on their practices. Magalhães and Celani (2005), for example, investigate reflective sessions as tools to empower English Language teachers during a reflective continued development course. The sessions were conceived as a “[…] collaborative space for teachers to examine their classes critically […]” (Magalhães and Celani, 2005, p. 135; our translation).

Reflection is informed by the adequate theoretical knowledge taken as reference, showing that thinking critically about one's own work (and, sometimes, in collaboration with colleagues) is performed by articulating and negotiating theoretical and practical knowledge, both directed to the professional conduct (Tardif, 2002). Reflecting can also be triggered by writing, as shown by Silva and Fajardo-Turbin (2011) and Silva (2014) in their investigations on the required supervised internship reports written by undergraduates in the Languages Teaching Degree. The experiences of required internships that consisted in either teaching or observing the supervisors’ classes at school were discussed in that particular context.

During the dinners, reflective reports were produced by the undergraduate students, which will be displayed on the analyses presented later in the article. Before the virtual sessions, the undergraduate students had been instructed to take notes on the points of the alphabetization teacher's lecture that they considered the most relevant and subject of discussion in the reports. These texts are catalyst genres as proposed by Signorini (2006b, p. 8; our translation) to name “[…] discursive genres that favor the development and the potentiality of actions and attitudes that are considered more productive for the educational process, both for teachers and their learners […]”.

Reflective reports can be defined by two main functions, here reproduced according to Signorini (2006a, p. 54; our translation) in her investigation of the genre. In her study, the author analyzes texts written by Portuguese Language teachers who worked at public schools in the state of São Paulo and, at the time, were participants in an in-service education project. The two main functions are:

[1st] to give voice to teachers as workers, that is, as agents in a specific work field. Through the elaboration of a “reflective report”, processes of articulation and legitimation of positions, roles and self-referenced identities are triggered, that is, narrators/authors build them for themselves […] [2nd] to create mechanisms and spaces of reflection about theories and practices that constitute the individual and collective ways of understanding and producing/reproducing this field of work, as well as the professional, individuals and group identities.

The reflective reports under analysis in this article were rewritten under the professor's supervision. The majority of the texts needed more than one rewriting, but that would be unfeasible due to the professor's overload of academic work.3 Nonetheless, the second versions were corrected and commented on in a process similar to the one the professor adopted for the first ones. Comments and corrections were recorded using a tool in Word for Windows, and involved compliments and corrections, such as “That's a very good point!”, “I liked your text. My only observation is directed to the absence of a direct dialogue with the scientific literature in your reflective report”.

Moreover, with few exceptions, the texts displayed various linguistic debilities, from spelling and grammar mistakes to inadequate organization and content development in the paragraphs (“Notice that you started using the verb in the past, therefore, you must continue with that tense rather than alternating to present simple to report the events”; “Verb-subject agreement. Revise the use of commas separating the subject and the corresponding verb.”). In addition to interventions on form, the professor asked questions to trigger deeper reflection on theoretical and practical aspects regarding the alphabetization context, such as “How did the teacher actually did that?”; “What do you understand by literacy?”; “Be more direct, what does the teacher really do with students in remote teaching? Cite examples.”.

The collaborative approach assumed in the present participatory research contributed to reduce the asymmetry in the relationship between school and university, since efforts were made to build more horizontal interactions. This is “[…] a different way of working with education, that is, working together in complementary and cooperative ways for a better work […]” (Montaño, Martínez and Torre, 2017, p. 654; our translation). It is noteworthy, according to the authors, that “[…] using TICs [Information and Communication Technologies] has played an important role in the development […]” of collaborative works in educational settings, “[…] becoming a means of communication that fosters the exchange of information and the joint development of knowledge […]” (Montaño, Martínez and Torre, 2017, p. 653; our translation).

CHARACTERIZING THE EDUCATIONAL CONTEXT

Methodological disputes informed by different theories have perpetuated in the history of alphabetization in Brazil, and their signs are easily noticed. Relying on linguistic studies, Cagliari (2007, p. 51) mentions a “[…] duel of methods […]” in the presentation of arguments that favor the development of “[…] the technical linguistic competence of teachers to help students […]” (Cagliari, 2007, p. 71), whereas Seabra and Capovilla (2010, p. 14; our translation), based on investigations in Psychology, defend the phonic method by citing the “[…] failed model of constructivist alphabetization in the National Curricular Parameters […]”.4

Recently, the dispute around the subject intensified after the publication of the National Policy for Alphabetization (Política Nacional de Alfabetização – PNA) (Brasil, 2019). The policy defends the exclusivity of the phonic approach informed by the cognitive science of reading (Silva, 2019; 2021; Buin, Ramos and Silva, 2021; Silva and Delfino, 2021; Faria and Silva, 2022), ignoring different theoretical perspectives that have guided the most recent Brazilian policies for education, such as the work with texts and genres from the perspective of literacy studies, developed in national and international territories with anthropological and pedagogical background (Cook-Gumperz, 1991; Massini-Cagliari, 2005; Morais, 2012; Soares, 2006; 2016).

The reports in this article will show that alphabetization teachers are still familiarizing with the concept. Indeed, they are making efforts to break with methodologies responsible for having children do repetition exercises and memorizing letters and families of syllables, as is typical of traditional school practices.

The activity of alphabetization demands a pedagogical and an investigative stance informed by complex approaches,5 given that various elements interact and interfere with the children's process of alphabetization, such as biological, pedagogical, psychological and linguistic factors. This justifies the scientific work of specialists from different fields. This particular perspective was contemplated in the course Alphabetization and Literacy required by the Teaching Degree in Pedagogy, however, due to adversities in pre-service teacher education, the linguistic instruction is favored as recommended by Cagliari (2007; 2021) and Buin, Ramos and Silva (2021).

Metalinguistic knowledge is necessary to foster autonomy in alphabetization teachers, which is indispensable for teaching and enables the selection of teaching strategies and methods or theoretical approaches that are most suited for different educational settings.6 Hence, it is understood that such educators need to know “[…] the linguistic issues related to their own classroom activity […]” (Cagliari, 2007, p. 70; our translation). The explicit knowledge about how different levels of language work, involving the phonological, morphological, syntactical, semantic, and pragmatic aspects, then, becomes necessary.

All these types of knowledge contribute to the planning of educational situations that can lead to children's linguistic awareness, so they are alphabetized knowing how their language works and not just memorizing or repeating letters or families of syllables. Such knowledge also allows teachers to analyze and interpret children's hypotheses on writing. This prevents the misguided treatment of their writings and, consequently, enables the production of new educational situations that trigger children's learning and development.

According to Freire (2008, p. 34), there is not, then, a pedagogical situation (also named pedagogical situation or pedagogical practice)

[…] without a subject who teaches, without a subject who learns, without a space-time within which these relationships take place, and there are no pedagogical situations without objects that can become known. […] There is no educational situation that does not point to objectives lying beyond the classroom, that does not have to do with conceptions, ways of reading the world, aspirations, and utopias.7

Moreover, underneath the dull alphabetizing practices lies the simplified notion of language as code, which is internalized by children and teachers. Characterized as a manifestation of language, verbal language is assumed here as a complex and dynamic system, composed of numerous subsystems interconnected and equally dynamic, based on which speakers and writers choose the options available in the system. Consequently, these choices enable the production of several meanings, motivated by contextual conditions (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014).

From the perspective of linguistic forms, writing, in turn, does not represent the sounds of language and cannot be reduced to “the act of writing letters”, as stated by an undergraduate in one of the reflective reports. Writing also represents the workings of different language levels — morphological, syntactical, semantic, and pragmatic —, including beliefs, values, ideologies. In short, writing represents discourses that unfold into actions through (verbal) language, causing, for example, different feelings, such as joy, empathy, sadness, violence, and suffering.

However, what is the space given to the systematic study of Portuguese in the Teaching Degree in Pedagogy discussed in the present article? The course program is organized into nine terms corresponding to academic semesters. As shown in Chart 1, there are five required courses that could be grouped under language studies. Either directly or indirectly, such courses can contribute to the linguistic education of alphabetization teachers.

Chart 1 Systematized study on the language of the teaching degree

| COURSE | TERM |

|---|---|

| 1. Academic Reading and Writing | 1st |

| 2. Alphabetization and Literacy | 5th |

| 3. Foundations and Methods for Teaching Languages | 6th |

| 4. Children's Literature | 6th |

| 5. Brazilian Sign Language (Libras) | 8th |

Source: Based on Palmas (2007).

The Teaching Degrees in Languages are responsible for the pre-service education of Portuguese teachers for the final years of primary school (Ensino Fundamental II — EF2) and High School, whereas the Teaching Degree in Pedagogy is responsible for the pre-service education for teachers of the first years of primary school (Ensino Fundamental I — EF1). The latter degree is also responsible for the pre-service education of Kindergarten teachers and administrative staff for schools and institutions that demand specialized pedagogical knowledge.

Establishing a parallel between these two degrees, the five courses belonging to the Degree in Pedagogy, represented in Chart 1, add up to one single academic semester, whereas Language Degrees typically offer additional seven semesters — given the standard of eight semesters for said degree. In other words, teachers who graduated with Language Degrees dedicate four years to the study of their mother language from different perspectives, whereas teachers who graduate in Pedagogy dedicate only one semester. According to Libâneo (2017, p. 70; our translation), “[…] it is impossible for that paradox not to jeopardize the system of pre-service education for the first years of primary school […]”.8

The criticism of the Teaching Degree in Pedagogy is necessary to expose these issues and propose solutions. The relevance of the degree in the educational and political context in Brazil is not ignored. In fact, in accordance with Demo (2011, p. 27; our translation),

pedagogy is the most important university course in our present time, since it defines what learning is. More than criticizing, it is urgent to rescue this definitely strategic degree, despite it being one of the most weak and heavily loaded with negative selection of students.

Resuming Chart 1, the three courses in highlights are taught by two specialists in linguistic studies, that is, they are professors that have undergraduate and stricto sensu graduate degrees in that field. They develop research and community outreach activities, consequently, their scientific production is also in that field, as expected from professors. During the three semesters considered for the present article, the two other courses, Academic Reading and Writing and Children's Literature, were not offered due to the lack of professors to teach them, or they were offered by professors who are not specialists in those fields, as previously described.9

The increasing vulnerability of the linguistic education for alphabetization teachers seems unavoidable in the face of remote teaching,10 adopted to ensure the continuity of academic activities and to respect the official guidelines for preserving the collective health, such as social distancing. According to the first and second paragraphs in the regulation for the didactic organization of teaching, the Resolution No. 28, of October 08 2020 (Resolução n° 28, de 08 de outubro de 2020, CONSUNI/UFT, 2020, s. p., our translation), which discusses the organization of academy activities during the emergency times of the pandemic, a substantial reduction on the workload of courses was ensured. These paragraphs are reproduced below:

§ 1° It is not mandatory that professors and students be 100% present in the same physical space and/or time for classes to be registered for both professors and students, consequently, attendance is not accepted as criterion for passing the course.

§ 2° It is mandatory the occurrence of synchronous meetings corresponding to the minimum of 25% and the maximum of 50% of the total hours in the course, and the exceeding workload is to be distributed in activities named independent studies, team work, or another format that is better suited for the course.

The first paragraph ensured that undergraduates will not fail courses by not attending classes or synchronous meetings in the remote modality. According to the document presented by the university administration, the complete absence in classes is offered as an alternative for students. Another aggravating factor is found in the second paragraph: professors are allowed to teach only 25% of the total hours of their courses. Hence, the total time destined for the five courses in Chart 1 could be reduced to the equivalent of only three courses.

Moreover, professors were impeded from teaching over 50% of the total hours originally destined for their courses. Such changes tend to affect basic school teaching, after all, the undergraduates were allowed to get to their work fields with only 25% of the hours assigned to different courses. It remains to be seen whether these changes also mean that the knowledge guaranteed to pre-service pedagogues corresponds to 25% of the content outlined in the pedagogical project of the course.

The second paragraph also claims that the remaining workload should be distributed to “[…] independent studies, teamwork, or another format that is better suited for the course […]” (CONSUNI/UFT, 2020, s. p., our translation). Research activities, then, seem to be ignored, unless they are conceived as belonging to “another format”. Such absence at a public university produces meanings; optimistically it could indicate the insistence in transmitting knowledge or in instructing, practices upon which many universities vegetate for some time, ignoring the 21st century abilities, among which research is a fundamental reference, to paraphrase Demo (2011).

The present criticism of the regimental adjustments does not mean an opposition to virtual teaching. In fact, there is agreement with the claim by Demo (2011, p. 16-17, our translation) that “[…] those who study are always present, regardless of where they are studying […] presence is a malleable and multidimensional dynamic, not limited to direct physical contact […]”. The risk is in the way professors and undergraduates understand and assume such flexibility. What does it mean to hear in frequent academic narratives that students are taking seven courses to enjoy the effortlessness of remote teaching? Undergraduates need to attend “[…] university, either physically or virtually, to produce knowledge, to exercise authorship, not to absorb rubbish […]” (Demo, 2011, p. 17, our translation).

Despite the “[…] tendency today […]” of “[…] not offering a course that is only in-person or only virtual, but a blended style […]” (Demo, 2011, p. 17, our translation), participants need to be minimally prepared and committed. In the context of the present research, several undergraduates owned out-dated equipment to access the internet and also had limited access to internet services, which limited their connection and compromised their full attendance to classes.11 The federal government should respond to such cases with robust and efficient policies, since the country's education is conditioned to teacher education and, in this case, the pre-service education of those responsible for alphabetizing children. Also in the institutional context in question, it is possible to find undergraduates with full access to the internet but who preferred to enjoy the right of not attending synchronous classes and this means absenting from all classes.12

WEAVING THE PARTICIPANTS’ VOICES

After being contacted by the course professor to share her professional experiences in the first Dining with the Alphabetization Teacher, the teacher understood that her activity would be relevant as it would provide undergraduates some contact with their future workplace. Hence, it would be possible to contribute to pre-service teacher education. This awareness did not relieve the teacher from the anguish and the fear of an unknown experience; however these feelings were overcome through courage and three attitudes she highlighted:

openness to dialogue with colleagues, which motivated her to accept the invitation;

remembering her participation in some continued development meetings to share her own practice with teachers from other schools, that led to the recognition of her work; and

remembering her experiences as supervisor of interns from other higher education institutions, which always left something good for her and contributed to her academic and professional life.

The teacher accepted the invitation based on the realization that the virtual meetings could help to continue the reflection about her own pedagogical practice. That promptness to learn new things was perceptible in her speech. As she shared some activities she did with children, theoretical articulations were also made possible. Raising awareness in undergraduates about the relevance of articulating theory and practice was also one of the reasons the teacher accepted the invitation. Indeed, this was the starting point of her exposition. The main theorists she mentioned as influences on her schoolwork were Artur Gomes de Moraes, Emília Ferreiro, Isabel Solé and Magda Soares.

In the excerpts reproduced below as examples, passages were underlined as they represented the four themes selected for analysis:

articulation between theory and practice;

reading of an adverse school context;

the guest's alphabetization practice; and

the alphabetization process itself.

Underlined and italics were used to highlight the undergraduates’ linguistic marks of reflection through writing or the schoolteachers’.

In the first excerpt of Fragments A, Tânia13 reports the process of remembrance shared by the teacher (“recalled”, “thought”, “found out”) of the time when she ignored theories during her initial teaching years. This attitude seems recurrent in pre-service teachers. Under the influence of university theoreticism, they either show some weariness toward the theories they have studied or difficulties in articulating them to the demands of their workplace. It is expected the dinners have contributed to prevent recurrent statements by the undergraduates such as: “the theories studied at university do not work for the school practice”; “theory's one thing, practice's something different altogether”.

Given the demands of her work, afterwards, the alphabetization teacher realized the importance of theory to guide practice and to answer the questions she was asking herself regarding her practice in the classroom, which began to be conceived as a laboratory. At the end of the first excerpt in Fragments A, the undergraduate student agrees with the appreciation of theory in what can be considered a paraphrases of this alphabetization teacher's speech, previously reproduced, before the student's writing of the fragment: “[…] theories are important, as they respond to teachers’ questions and concerns, contributing, therefore, to problem-solving and doubts that may rise in their practice.”.

Fragments A. Articulating theory and practice

The teacher reported her practice and recalled that, right in the beginning, when she got into a classroom, she abandoned many theories because shethought they were not necessary, sticking with the practice, but during her journey, she found out that she could not walk without the theory. According to the educator, “classrooms are laboratories, and theorists answer our questions so we can help students’ learning processes, so they can progress”. In this sense, theories are important, as they respond to teachers’ questions and concerns, contributing, therefore, to problem-solving and doubts that may arise in their practice. (Tânia)

In addition to visual resources and the activities, I saw that the alphabetization teacher relied on extensive theoretical knowledge that is of great importance to understand the development of literacy in each child. (Rita)

I conclude this report, emphasizing that Dining with the Alphabetization Teacher provided me with many learnings in reference to the alphabetization and the literacy process, which, as Magda Soares (2004) underscores, are simultaneous. Nonetheless, every and each educational action is based on theory and practice, and both knowledge are indissociable for an education of excellence. (Kélbia)

In the second excerpt, the student Rita also highlights the teacher's theoretical knowledge and the use of that knowledge to monitor children's development (“[…] the alphabetization teacher relied on extensive theoretical knowledge that is of great importance to understand the development of literacy in each child.”). The third excerpt shows the relevance of articulating theory and practice for Kélbia, as she underscores the conclusion of her reflective report.

During the selection of experiences to share in the dinner, the alphabetization teacher resumed her own questions during her first years of teaching, since the undergraduates could be asking themselves similar questions. These were the questions she considered: what is the best method? How to alphabetize? How to help learners with difficulties? Where to start alphabetization? The teacher tried to bring to university a meaningful display from her classroom, with evidence of the children's development and samples of the procedures that enabled that development.

To share the answers to her questions, the teacher showed part of what she built as reference to the process of alphabetization, which is composed of the work with phonological awareness and with the systematization of the properties of writing. According to the children's development, classes are not entirely expository, but students are protagonists in different experiences, involving interactions in small and large groups, to allow for collective discoveries in each educational situation.

A different issue approached by the teacher and more relevant for the undergraduate students was the diagnostic assessment of reading comprehension and the pedagogical procedures to stimulate and guide children to progress in the construction of knowledge about the alphabetic writing system. Once again, the alphabetization teacher tried to anticipate possible questions based on specific experiences. During her own pedagogical practice, she performed many diagnostic assessments, but she ignored the trajectory, the activities and the interventions needed to promote the children's learning and development.

The undergraduates realized that the alphabetization teacher worked differently from what is possible to observe at school, and which preserves the negative representation of teaching. In the first excerpt in Fragments B, the alphabetization teacher led Jane to reflect (“lead me to a reflection”; “I think”) about the continuous deficit in teaching that is exclusively attributed to teachers, who use the textbook to rewrite letters and small unconnected sentences. Such practice opposes the different alphabetization setting exposed in the dinner and which Jane described previously in her reflective report: alphabet on the walls and calendars made by students, the reading corner, pedagogical games, reading sheets, panel of combinations.

The first excerpt in Fragments B corresponds to the last paragraph of Jane's reflective report, which is less optimistic regarding the necessary changes in the alphabetization practices. Once more, the alphabetization teachers are represented as main culprits for unproductive pedagogical practices that fail to meet children's individual needs (“[…] not all educators are willing to face the challenge of alphabetization, which demands dedication and daily reinvention.”).

Fragments B. Reading and adverse school context

This moment of talking to an alphabetization teacher was essential to lead me to a reflection on how deficient our teaching is and how teachers still resist alphabetizing by using books to rewrite letters and small unconnected sentences. I think that it won't be easy to change alphabetization, it is a slow process and, as mentioned before, not all educators are willing to face the challenge of alphabetization, which demands dedication and daily reinvention. All of that to meet the particularities of each student and alphabetize them. (Jane)

Her behavior is very different from the collective imagination that I have of primary and high schools. I justify: I notice a dominant laziness in regard to reading, studying and making an effort. It seems that we have walked toward the easy and I fear there is no turning back […]. This fact is perceptible on the school desks, when the exercises are too many, the classes are long, children complain with parents, who complain with the school, which, in turn, facilitate students’ lives. The teachers, by adjusting to these demands, feel less motivated to produce more, better, and differently […]. (Sara)

In the second excerpt of Fragments B, the teacher's commitment is also recognized (“Her behavior is very different from the collective imagination […]”) and that attitude is opposed to the negative representation of teaching in the popular imagination (“[…] a dominant laziness in regard to reading, studying and making an effort.”), according to Sara's perception. At the same time that she seems to think of the teachers as responsible for the exhausting classroom routine and for the lack of investments in their own education (“[…] the classes are long, children complain with parents, who complain with the school, which, in turn, facilitate students’ lives.”). The undergraduate admits that the teachers are also demotivated by the interference of the children's parents/guardians and the school administration on the pedagogical work (“[…] by adjusting to these demands, feel less motivated to produce more, better, and differently […]”).

The surprise Sara shows before the teacher's pedagogical practice is justified by the fact that she shares a negative representation about the school culture, characterized by gross flexibility or effortlessness (“[…] we have walked toward the easy and I fear there is no turning back […]”), similar, perhaps, to what other undergraduates have observed at university according to the claims of enjoying the effortlessness of remote teaching to take seven courses in one term.

In the first excerpt in Fragments C, there are two indicatives that justify Sara's surprise (“[…] this is all revolutionary!”):

the alphabetization practice begins with the texts, sensitizing students to notice the linguistic resources responsible for various sound repetitions, which enable the work on small linguistic units, such as phrases, lines, words, symbols, and phonemes (“Starting alphabetization from the macro (text) so that through the child's own perception we can reach the micro (words) is recognizing in the child a perceptive potentiality […]”); and

the linguistic awareness developed by the teacher in her students was not part of the undergraduates’ experiences in alphabetization (“[…] I feel I was denied. It is as if from the beginning, in alphabetization, there was the assumption of our incapacity of understanding […]”).

Sara understands the most common method of alphabetization used with children in her own generation limited their development (“[…] limited the development of many potentials and abilities in my generation, that, as I said, was alphabetized in a different way.”).

Fragments C. Guest's literacy practices

For me, this is all revolutionary! Starting alphabetization from the macro (text) so that through the child's own perception we can reach the micro (words) is recognizing in the child a perceptive potentiality that I feel I was denied. It is as if from the beginning, in alphabetization, there was the assumption of our incapacity of understanding, which has already limited the development of many potentials and abilities in my generation, that, as I said, was alphabetized in a different way. (Sara)

For a pedagogy student like me, it was very important to receive the knowledge of a teacher who worries about the education of her students. It is not just about teaching them to read or write but educating a thinking and critical child. Therefore, through the course, I have been constructing my own knowledge about the process of alphabetization, deconstructing my knowledge, and actually learning the act of alphabetizing. (Teca)

To conduct her classes, the teacher also has the support of digital tools, given the current pandemic which we are living through now. I emphasize that I was impressed with the technological possibilities explored by the teacher to explore the subjects, like the tools available on Zoom, on which the teacher uses an interactive board to allow students to write on the computer/cell phone screens using the mouse or their fingers. (Kélbia)

In the second excerpt of Fragments C, it is possible to observe Teca's confrontation with a different professional attitude and an alphabetization practice, which certainly were distant from the representations shared by the undergraduates. A teacher that worries about the students’ learning and development should not cause surprise, but the undergraduate's claim seems to point to something exceptional (“[…] it was very important to receive the knowledge of a teacher who worries about the education of her students.”). The process of alphabetization starting with the children's awareness of the writing system was noted by the undergraduate, who also perceived that the approach involves the learner's critical education (“It is not just about teaching them to read or write but educating a thinking and critical child.”).

In the final part of the second excerpt in Fragments C, Teca shows awareness of her own learning process in the course Alphabetization and Literacy, which is performed through the deconstruction of old representations about the alphabetization itself and the construction of new knowledge (“I have been constructing”, “deconstructing”, “learning”). In the third excerpt, Kélbia's surprise is noticeable before the teachers’ use of digital technologies (“I was impressed”) to teach remote classes for children (“[…] an interactive board to allow students to write on the computer/cell phone screens using the mouse or their fingers.”). Certainly, the representation about alphabetization classes shared by the undergraduate corresponded to the traditional model. It is significant that technological innovation has reached the undergraduate student through the school.

In Fragments D, three excerpts that illustrate the undergraduate's memories of the alphabetization process they were subjected to in childhood. In other words, they are confronted with the memory of the process and of the alphabetization teacher, as shown by Sara in the first excerpt of Fragments C. All the undergraduates admit that they were alphabetized through traditional school methods, rather different from the linguistic awareness approach exposed in the dinners.

Fragments D. One's own literacy process

In my educational development, I didn't experience a process of awareness in the System of Alphabetic Writing with a so dynamic didactic such as the one presented by Leonilde Campos. My alphabetization was just memorizing letters and repeating the writing of words in dotted books. (Wanda)

Some experiences are incapable of triggering reflection in students, and this favors the use of traditional methods, which unfortunately many of us were exposed to and because of that we tend to reproduce. (Raca)

In my childhood, I was alphabetized on a learn-by-heart basis, I am realizing the importance of phonological awareness “today” in college. (Jucy)

In the first excerpt, Wanda describes the teaching method she was submitted to as a practice of memorizing letters, repetitive writing of words in the dotted textbooks. In the second excerpt, Raca characterizes the traditional methods as incapable of triggering reflection in students and admits that the undergraduates exposed to such methods tend to reproduce them as they start teaching (“[…] unfortunately many of us were exposed to and because of that we tend to reproduce.”). In the third excerpt, Jucy uses the expression “on a learn-by-heart basis” to characterize the alphabetization practice she was subjected to in childhood and admits to having discovered the concept of phonological awareness in the Teaching Degree in Pedagogy (“I am realizing”).

The pre-service teachers were not the only ones to be provoked during the dinners, the alphabetization teacher herself admitted to having considered all the questions asked by the undergraduate students and by the professor in previous dinners to plan her exposition for the other meetings. Some of these questions were: what is the difference between working with children who have never attended school and children who attended kindergarten? What is the best method? How does one work with children with disabilities? How does one work with children who swap letters?

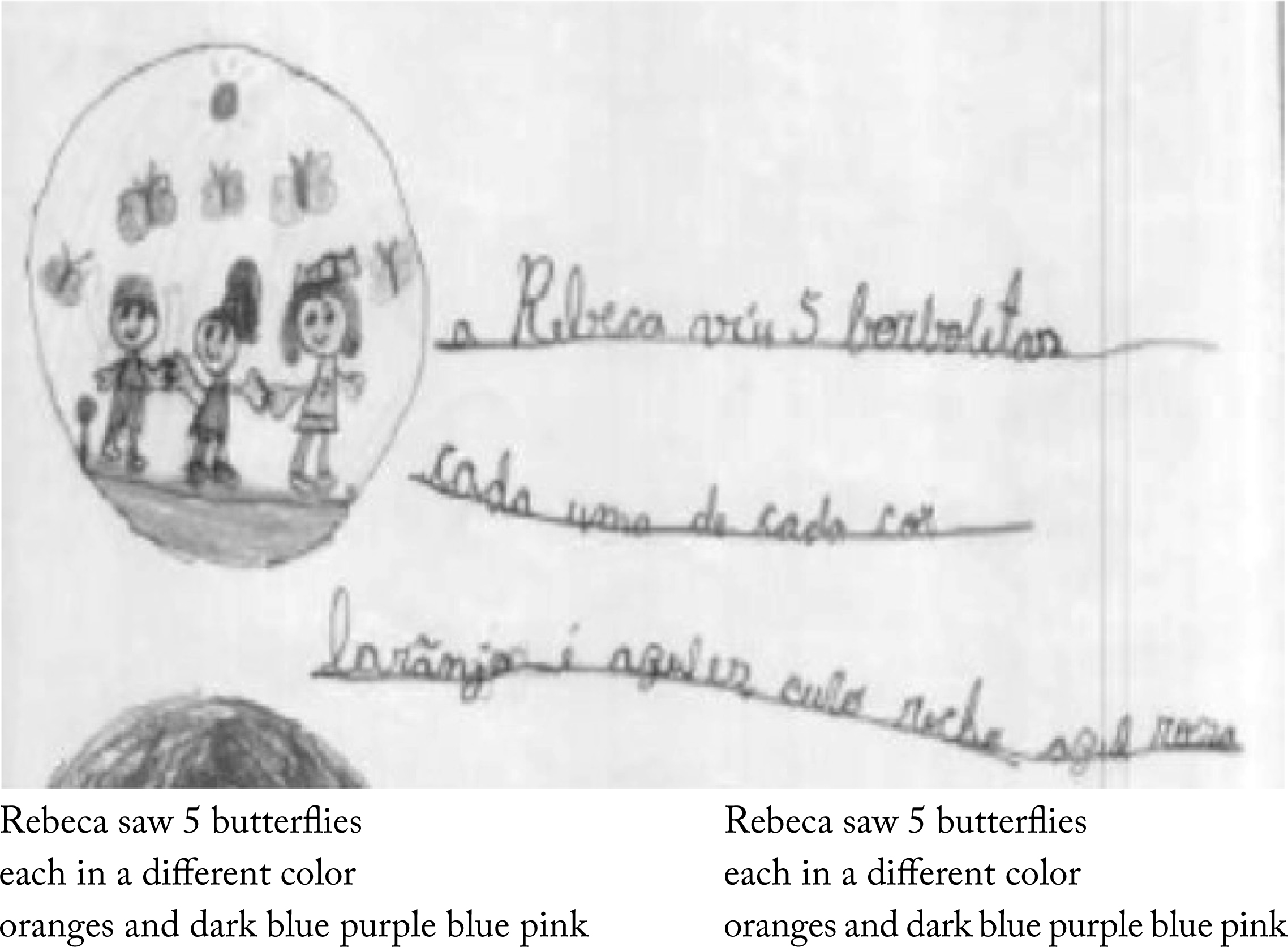

These questions and comments made during the virtual dinners led the teacher to reflect on some classroom situations. For instance, the observation made by the professor when Figure 2 was reproduced with the following word written by a 6 year-9 month old child at the end of the first year in primary school: larãnja (orãnge).

The professor argued that one of the challenges in the process of alphabetization is the interpretation of the children's hypotheses on writing, which demands linguistic knowledge to analyze different levels of the language. He also stated that the students most likely used the tilde in the word “larãnjas” (orãnges) as she realized the nasal sound in the stressed syllable. Consequently, the teacher realized that, before identifying or highlighting children's mistakes, it would be important to understand that the child was aware of the stressed syllable and the use of tilde, but that they did not realize or did not know that the letter “n”, at the end of a syllable, already indicates the stressed nasal sound.14 Hence, it would not be possible to double indicate nasal sounds in a word.

A different example of the teacher's learning in the dinners concerns the interventions in situations of writing when children mistake “u” for “l” at the end of words, such as the following sentence written by a different 1st year student: “A lagarta virol uma gorboleta” [the caterpillar turned into a butterfly]. In one of the dinners, the professor explained that, in such cases, teachers can activate the morphological knowledge of verbs, since this is a case of past tense in the third person singular. To clarify the issue, the professor displayed the poem O Elefante Eduardo (The Elephant Eduardo) by Alexandre Azevedo, which presents the use of that tense in a given context.

| O ELEFANTE EDUARDO | THE ELEPHANT EDUARDO15 |

|---|---|

| O elefante | The elephant |

| Eduardo | Eduardo |

| Era tão elegante… | Was so elegant… |

| Mas, um dia, | But, one day, |

| Entrou num | He walked into |

| Restaurante, | A restaurant, |

| Comeu, | Ate |

| Comeu, | Ate |

| Comeu, | Ate |

| Comeu bastante… | Ate in abundance… |

| Bebeu, | Drank |

| Bebeu, | Drank |

| Bebeu, | Drank |

| Bebeu refrigerante… | Drank the punch… |

| O elefante | The elephant |

| Eduardo | Eduardo |

| Engordou cem quilos | Put on a hundred pounds |

| Num instante! | In an instant! |

| (Azevedo, 2011, p. 9) |

After she became aware of the verbal tense in question, the alphabetization teacher adopted what can be called a strategy of action in her classroom, as she understands that such words mean past actions. When children would ask whether a certain word was spelled with “l” or “u”, she would answer “is this a finished action in the past?”. The learners, then, were able to answer for themselves that the word was spelled with “u”.

In short, the alphabetization teacher realized that both the school and the university benefited from the virtual collaborative sessions. More importantly, due to the meetings, her students were able to continue learning, which motivates her to offer children the best. It is also noted that the dinners promoted unforgettable experiences and made her see her classroom and the university differently. The dinners reinforced the importance of theoretical support for the alphabetization practice and the need for more intentional interventions in educational situations.

FINAL REMARKS

Amid the difficulties caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the present study showed that Dining with the Alphabetization Teacher collected educational and collaborative situations that triggered the empowerment of the participants. This was made possible by the openness to dialogue on the part of representatives for school and university, who were a professor, an alphabetization teacher, and three undergraduate classes of pre-service teachers.

The virtual sessions were characterized as a productive activity during the course Alphabetization and Literacy, in the Teaching Degree in Pedagogy. The writing of reflective reports by the undergraduate students complemented the collaborative work of the dinners through the discussion of specific aspects of the alphabetization teacher's pedagogical practices, considering the theoretical contributions of the texts read throughout the course as well as the recommended readings. The main themes discussed in these reports were: articulation between theory and practice; reading of an adverse school context; the guest's literacy practice; and one's own process of alphabetization.

It is noteworthy that the interinstitutional dialogue contributed to the undergraduate students’ theoretical understanding. They realized the importance of such theoretical support in other virtual meetings and displayed increased autonomy to research unknown concepts and the interest in understanding the theoretical and methodological disputes regarding the alphabetization process. Indeed, the undergraduate students could only understand some methodological questions after the alphabetization teacher shared her practice in the dinners and after they experienced reflecting through writing and rewriting their reports.

The dinners, then, were opportunities for knowledge to be shared between the guest teacher and the professor. The latter, for example, became closer to the actual work in the cycle of alphabetization at school, which was not possible before, in the in-person teaching, when the undergraduates are supervised by generalist teachers (not by specialists in the “course subjects”) in their required supervised internships. It would be productive for the works performed by both institutions represented in the article to be mutually reinforced. In this regard, some important adjustments were made by the teacher and the professor in their own pedagogical practice throughout the three academic terms.

Finally, it is expected that teaching degrees become the vanguard of teacher education, preparing for present and future school demands. This study has revealed the importance of the school in this process conditioned by mutual trust. Such vanguard could hardly be achieved by vain universities and silenced schools.

REFERENCES

AZEVEDO, A. O ABC do dromedário. Ilustrações de Jótah. 3. ed. São Paulo: Paulinas, 2011. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais: Língua Portuguesa. Brasília: Secretaria de Educação Fundamental/MEC, 1997. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/seb/arquivos/pdf/livro02.pdf. Acesso em: 15 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Secretaria de Alfabetização. PNA: Política Nacional de Alfabetização. Brasília: MEC, SEALF, 2019. 54 p. Disponível em: http://alfabetizacao.mec.gov.br/images/pdf/caderdo_final_pna.pdf. Acesso em: 16 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

BUIN, E.; RAMOS, N. S. C.; SILVA, W. R. Escrita na alfabetização. Teresina: EdUESPI, 2021. https://dx.doi.org/10.36970/eduespi/2021314 [ Links ]

CAGLIARI, L. C. Alfabetização – o duelo dos métodos. In: SILVA, E. T. (org.). Alfabetização no Brasil: questões e provocações da atualidade. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2007. p. 51-72. [ Links ]

CAGLIARI, L. C. Práticas de alfabetização de crianças e formação de alfabetizadoras. In: FARIA, E.; SILVA, W. R. Alfabetizações. São Paulo: Pontes Editores, 2021. p. 16-41. [ Links ]

CONSELHO UNIVERSITÁRIO DA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO TOCANTINS (CONSUNI/UFT). Resolução n° 28, de 08 de outubro de 2020. Palmas: Universidade Federal do Tocantins, 2020. Disponível em: https://docs.uft.edu.br/share/s/m356DUWVSWGkBG2LOm363Q. Acesso em: 15 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

COOK-GUMPERZ, J. (org.). A construção social da alfabetização. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 1991. [ Links ]

DEMO, P. Outra universidade. Jundiaí: Paulo Editorial, 2011. [ Links ]

DEMO, P. Aprender como autor. São Paulo: Atlas, 2015. [ Links ]

FARIA, E.; SILVA, W. R. Alfabetizações. Campinas: Pontes Editores, 2022. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P. Pedagogia do compromisso: América Latina e Educação Popular. 1. ed. Indaiatuba: Villa das Letras, 2008. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P. Conscientização. São Paulo: Cortez, 2016. [ Links ]

FREIRE, P.; MACEDO, D. Alfabetização: leitura do mundo, leitura da palavra. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra, 1990. [ Links ]

HALLIDAY, M. A. K.; MATTHIESSEN, C. M. I. M. An introduction to functional grammar. 3. ed. Londres: Arnold, 2014. [ Links ]

LIBÂNEIO, J. C. A formação de professores no curso de Pedagogia e o lugar destinado aos conteúdos do Ensino Fundamental: que falta faz o conhecimento do conteúdo a ser ensinado às crianças?. In: SILVESTRE, M. A.; PINTO, U. A. (org.). Curso de Pedagogia: avanços e limites após as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais. São Paulo: Cortez, 2017. p. 49-78. [ Links ]

MAGALHÃES, M. C. C.; CELANI, M. Reflective Sessions: a tool for teacher empowerment. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, Belo Horizonte, v. 5, n. 1, p. 135-160, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-63982005000100008 [ Links ]

MASSINI-CAGLIARI, G. O texto na alfabetização: coesão e coerência. Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 2005. [ Links ]

MONTAÑO, M. J. N.; MARTÍNEZ, A. L.; TORRE, M. E. H. El trabajo colaborativo en red impulsor del desarrollo profesional del profesorado. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 17, n. 70, p. 651-667, 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782017227033 [ Links ]

MORAIS, A. G. Sistema de escrita alfabética. São Paulo: Melhoramentos, 2012. [ Links ]

MORIN, E. Introdução ao pensamento complexo. 5. ed. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 2008. [ Links ]

PALMAS. Projeto Político-Pedagógico do Curso de Pedagogia do Campus de Palmas. Palmas: Universidade Federal do Tocantins, 2007. Disponível em: http://download.uft.edu.br/?d=4c4913ef-331c-4849-9216-ce987051f139;1.0:PPC%20Pedagogia%20Palmas%202007.pdf. Acesso em: 15 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

SEABRA, A. G.; CAPOVILLA, F. C. Alfabetização: método fônico. 5. ed. São Paulo: Memnon Edições Científicas, 2010. [ Links ]

SIGNORINI, I. O gênero relato reflexivo produzido por professores da escola pública em formação continuada. In: SIGNORINI, I. (Org.). Gêneros catalisadores: letramento e formação do professor. São Paulo: Parábola Editorial, 2006a. p. 53-70. [ Links ]

SIGNORINI, I. Prefácio. In: SIGNORINI, I. (org.). Gêneros catalisadores: letramento e formação do professor. São Paulo: Parábola Editorial, 2006b. p. 7-16. [ Links ]

SILVA, W. R. Construção da interdisciplinaridade no espaço complexo de ensino e pesquisa. Cadernos de Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 41, n. 143, p. 582-605, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742011000200013 [ Links ]

SILVA, W. R. Reflexão pela escrita no estágio supervisionado da licenciatura: pesquisa em Linguística Aplicada. Campinas: Pontes Editores, 2014. [ Links ]

SILVA, W. R. Polêmica da alfabetização no Brasil de Paulo Freire. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, Campinas, v. 58, n. 1, p. 219-240, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1590/010318138654598480061 [ Links ]

SILVA, W. R. Educação científica como estratégia pedagógica e investigativa de resistência. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, Campinas, v. 59, n. 3, p. 2278-2308, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/01031813829221620201106 [ Links ]

SILVA, W. R. Letramento ou literacia? Ameaças da cientificidade. In: SILVA, W. R. (org.). Contribuições sociais da Linguística Aplicada: uma homenagem a Inês Signorini. Campinas: Pontes Editores, 2021. p. 111-162. [ Links ]

SILVA, W. R.; DELFINO, J. S. Letramentos familiares na política de alfabetização. Revista Brasileira de Alfabetização, São Paulo, n. 14, p. 148-169, 2021. https://doi.org/10.47249/rba2021450 [ Links ]

SILVA, W. R.; FAJARDO-TURBIN, A. E. Relatório de estágio supervisionado como registro da reflexão pela escrita na profissionalização do professor. Polifonia, Cuiabá, v. 18, n. 23, p. 103-127, 2011. Disponível em: https://periodicoscientificos.ufmt.br/ojs/index.php/polifonia/article/view/25. Acesso em: 15 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

SOARES, M. Letramento: um tema em três gêneros. 2. ed. Belo Horizonte: Autêntica, 2006. [ Links ]

SOARES, M. Alfabetização: a questão dos métodos. São Paulo: Contexto, 2016. [ Links ]

TARDIF, M. Saberes docentes & formação profissional. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2002. [ Links ]

1In this article, literacy teachers will be assumed as females based on the understanding that most teachers in basic education schools, particularly kindergarten and first years of primary school, are women.

2T.N. In Brazil, the word alphabetization means teaching-learning to write and read, as a result of learning how the properties of the linguistic system work, whereas literacy means language practices that involve reading and writing. These meanings will be preserved in the use of these words throughout the article.

3Exceptionally, some undergraduate students insisted on rewriting their texts more than once; while the professor didn't oppose, those were the undergraduates whose texts demanded less rewriting.

4The National Curricular Parameters (Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais, PCN) are guidelines for Brazilian primary schools published during the 1990s in the 20th century (Brasil, 1997). The cited authors refer to the PCN for Portuguese Teaching. Regarding these theoretical-methodological disputes in the context of literacy studies, the works of Silva (2019; 2021) are suggested.

5Complexity means the dynamic of several human and non-human actors united in a sort of dynamic system, in which actions and feedback are triggered (Morin, 2008; Silva, 2011). Therefore, complexity is not simply conceived as something complicated or difficult.

6According to Cagliari (2007, p. 71), “Whether it is more or less phonic, more or less behaviorist, more or less cognitive is a question that, to an extent, depends on the teacher's ability and preference. Some work better within a certain approach, specifically dealing with a certain method or another”.

8On that matter, Cagliari (2007, p. 65) claims that “[…] teachers need a solid, broad education, adequate to their work as teachers and educators. The education colleges, in terms of practice, always think of the educator and forget that they will also be teachers with specific technical tasks, with scientific and artistic content that will be employed in their professional daily lives […]” (our highlights and translation).

9Given the absence of full professors to teach the courses, a part of the faculty collegiate has shared the understanding that educators themselves, that is, pedagogues with stricto sensu degrees in Science of Education should teach those courses.

10According to the first article in the Resolution n° 28 of 08th October 2020 (CONSUNI/UFT, 2020, s. p.), remote teaching is conceived as “the collection of academic activities mediated by technology at synchronous and asynchronous times conducted for in-person under graduation courses in the times of social distancing with total restriction of physical presence.”

11In the present research, there is a controversy regarding the duration of synchronous classes. There are those who understand that the 50-minute interval, the reference time for classes, should be observed for a full remote session. However, for in-person classes, each session corresponds to four consecutive classes for 60-hour courses, totalizing 200 minutes. The argument for that interpretation is the compromise of academic development of undergraduates due to computer or cell phone screens. The issue was not present in stricto sensu graduate classes. The adjustment was ignored for the course Alphabetization and Literacy, which was well received by students. Nonetheless, the professor observed closely the engagement and the development of undergraduates during the virtual classes, and adjustments were made according to the emerging demand.

12The participants authorized the recording of virtual classes for the course Alphabetization and Literacy, whose videos were made available for the class exclusive access on Google Classroom. At the present university, to record classes was an alternative given to professors and students. Recording the meetings helped the occasional difficulties faced by some undergraduates to access the internet at the time of the classes. The video recordings, then, could be accessed and even revisited for the assignments. The dinners were equally recorded and made available. Recently, the record function was deactivated on that educational platform, which might compromise academic activities due to the different uses that the academic community learned for that resource.

13Fictional names were used to identify the authors of the fragments selected from the reflective reports. Some fragments were subjected to minor corrections to prevent the reproduction of grave errors. The undergraduates have authorized the use of the excerpts for this investigation.

14The child’ use of tilde is similar to the word cãibra (cramp), which competes with the variation câimbra.

Acknowledgment

The first author of this article thanks the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the research productivity grant – PQ/1D (Proc. 304186/2019-8).

Received: August 02, 2021; Accepted: February 11, 2022

texto en

texto en