Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1413-2478versión On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.27 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub 11-Nov-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782022270112

Article

The circularity of the management team of the Ministry of Education of the Fernando Henrique Cardoso governments

IUniversidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, ES, Brazil.

This article analyzes the circularity of the Management Team of the Ministry of Education of the Fernando Henrique Cardoso governments (1995–2002). Its theoretical-methodological foundation is critical-documental analysis as in Marc Bloch, and it seeks, in Jean-François Sirinelli's theories, the understanding of intellectuals. It uses the Gephi software and takes as sources Lattes resumes and Google searches. The periodization was divided into two moments: until 2002, to understand the influence of circularity before and during the occupation of the place of power; and from 2003, to understand the spaces that began to circulate with the end of the FHC administration. The results point to a circularity consonant with a political culture based on the recommendations of multilateral organizations, as well as the continuity of this political culture after the end of the government and the influence of intellectuals on educational policies due to the spaces in which they began to circulate.

KEYWORDS education; political culture; management team

Este artigo analisa a circularidade da Equipe Dirigente do Ministério da Educação dos governos de Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995–2002). Tem como fundamentação teórico-metodológica a análise crítico-documental, em Marc Bloch, e busca, nas teorizações de Jean-François Sirinelli, a compreensão dos intelectuais. Utiliza, como ferramenta de auxílio, o software Gephi. Assume como fontes os currículos Lattes e pesquisa no Google. A periodização foi dividida em dois momentos: até 2002, para compreender a influência da circularidade antes e durante a ocupação do lugar de poder; e a partir de 2003, para entender os espaços que passaram a circular com o fim do governo. Os resultados apontam uma circularidade consonante a uma cultura político-educacional firmada nas recomendações dos organismos multilaterais, assim como a continuidade dessa cultura política após o término do governo e as influências dos intelectuais nas políticas educacionais graças aos espaços em que passaram a circular.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE educação; cultura política; equipe dirigente

Este artículo analiza la circularidad del Equipo Directivo del Ministerio de Educación en los gobiernos de Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995–2002). Su fundamento teórico-metodológico es el análisis crítico-documental, en Marc Bloch, y en las teorías de Jean-François Sirinelli, la comprensión de los intelectuales. Utiliza el software Gephi. Toma como fuentes Lattes Currículums y búsquedas de Google. La periodización se dividió en dos momentos: hasta 2002, para comprender la influencia de la circularidad antes y durante la ocupación del lugar de poder; ya partir de 2003, comprender los espacios que empezaron a circular con el fin del gobierno. Los resultados apuntan a una circularidad en consonancia con una cultura política basada en las recomendaciones de organismos multilaterales, así como la continuidad de esta cultura política tras el fin del gobierno y la influencia de los intelectuales en las políticas educativas debido a los espacios en los que empezaron a circular.

PALABRAS CLAVE educación; cultura política; equipo directivo

INTRODUCTION

When analyzing the most recent High School reform, represented by Law No. 13.415/2017 and by the Common National Curriculum Base for High School (BNCCEM), researchers in the field of educational policy1 understood it as a resumption of the educational project of the 1990s, especially the octennial policies of Fernando Henrique Cardoso (FHC).

Ciavatta and Ramos (2012) compared the 1998 and 2012 versions of the National Curriculum Guidelines for High School (DCNEMs) and found that the latter maintained an adaptive and uncritical view of the labor market and its functionality for the business sectors, a continuity of the 1998 DCNEMs, even in a period when power was in the hands of a group with a progressive bias.

In this sense, Motta and Frigotto (2017) highlighted the speed at which the high school reform was approved, followed by the BNCCEM in 2018 and the DCNEMs in the same year. For the authors, this reform put an end to high school as the last stage of basic education. Even critics of the Law of National Education Guidelines and Bases (LDBEN/1996) and the National Education Plan (PNE 2014–2024) understood that the High School reform ignored the assumptions of these legal provisions and deepened the changes foreshadowed in the 1990s. In this direction, Silva (2018) understood that the discourse of the current High School reform retroacted to the educational conceptions of the mid-1990s, especially with regard to competency-based education and the idea of competitiveness, producing managed training.

In an analysis of Provisional Measure No. 746/2016, Cunha (2017) concluded that one of the functions of this regulation was to contain the demand for higher education through mergers of the curricular branches of high school, which had already occurred in the 1970s and 1900s but added to a crisis in private higher education as a result of unprecedented corporate centralization and concentration of capital. In addition, the author highlighted the performance of Maria Helena Guimarães de Castro in the FHC government and her return to a place of power in the Michel Temer government, attributing to her the foundation of the current High School reform.

Given the above, the question was: how did this resumption of the educational project of the 1990s happen? Where did the subjects responsible for forming the political-educational culture of the 1990s circulate before occupying the place of power? Where did these subjects start to circulate when they no longer held a place of power in the Federal Executive (from 2003)?

Thus, based on Bloch's (2001) understanding that the past does not change, but that lack of knowledge of it compromises the comprehension of present and future actions, the objective was to identify and analyze the circulation and connections of the subjects who were responsible for developing the political-educational culture of the 1990s (1995–2002), before and after occupying a place of power, to understand how this political culture was resumed in current educational reforms.

THEORY AND METHOD

As a theoretical-methodological foundation, critical documentary analysis was used (Bloch, 2001). When writing about historical observation, Bloch (2001, p. 73) stated that, “[…] as a first characteristic, the knowledge of all human facts in the past, most of them in the present, must be knowledge through vestiges”. Thus, in the vestiges of the links to institutions and the circulation of the subjects of the Ministry of Education (MEC) Management Team (1995–2002), the way in which their conceptions of education constituted the political-educational culture of that period and continued to influence Brazilian education (since 2003) was sought.

Accordingly, the evidentiary paradigm of Ginzburg (1989) was mobilized, from which the evidence and clues left in the sources were captured, evidencing the connections and conceptions of the subjects. The concepts of center and periphery and power relations (Ginzburg, 1991) were also used to understand the disputes in the constitution of a political culture, expressed through the tensions of tactics over strategy (Certeau, 2011).

Understanding how the political-educational cultures of the subjects who designate them are constituted is important, insofar as it is understood that political cultures play a fundamental role in the legitimization of regimes or in the creation of identities. Berstein (2009, p. 31) defines political culture as: “[…] a group of representations that carry norms and values that constitute the identity of great political families and that go far beyond the reductionist notion of political party”.

The author considers the perspective of an unalterable national political culture to be inadequate. The proposal would be to think about it in plural terms, identifying the different political cultures that integrate and dispute the same national space. According to Berstein (2009, p. 36), “[…] the sociability networks that define the cohesion of the group: the diversity of its nature, the frequency of meetings […]” should also be taken into account.

At the same time, Berstein's (2003, p. 60) theorization of political parties was appropriated and understood as the “[…] place where political mediation operates”, located between the problem and the narrative, seeking to articulate the needs and aspirations of society.

In addition, Sirinelli's (2003) theorizations were mobilized to understand subjects as intellectuals and the motivations that lead them to gather in groups, and Rioux’ (2003) studies on associations (institutions) were drawn on, along with the indications that were captured from them to understand the political culture.

The MEC Management Team is so named because it is made up of those who were part of the group of civil servants under the Executive Branch's discretion, of free appointment and exoneration, with greater hierarchical proximity to the minister and with decision-making capacity. The list of professionals who made up this team in the period (1995–2002) — considering the dynamism of the political field — was found in the annex of the book A revolução gerenciada: educação no Brasil 1995-2002 (The revolution managed: education in Brazil 1995-2002) (Souza, 2005), totaling 60 members.

The study adopted as sources the Lattes curricula of the subjects and, when information on their links and circularity was not found, Google was used. In addition, the Gephi software2 was used as an instrument to aid the analyses, to determine the circularity networks of the subjects.

Periodization was divided into two times: the first comprises the circularity of the subjects until the year 2002, to identify the influences of their connections until the period in which they were in the MEC Management Team; and the second refers to the circularity of subjects from 2003 onwards, to analyze the way in which these subjects began to influence educational policies in the spaces in which they circulated, when they no longer occupied a place of power.

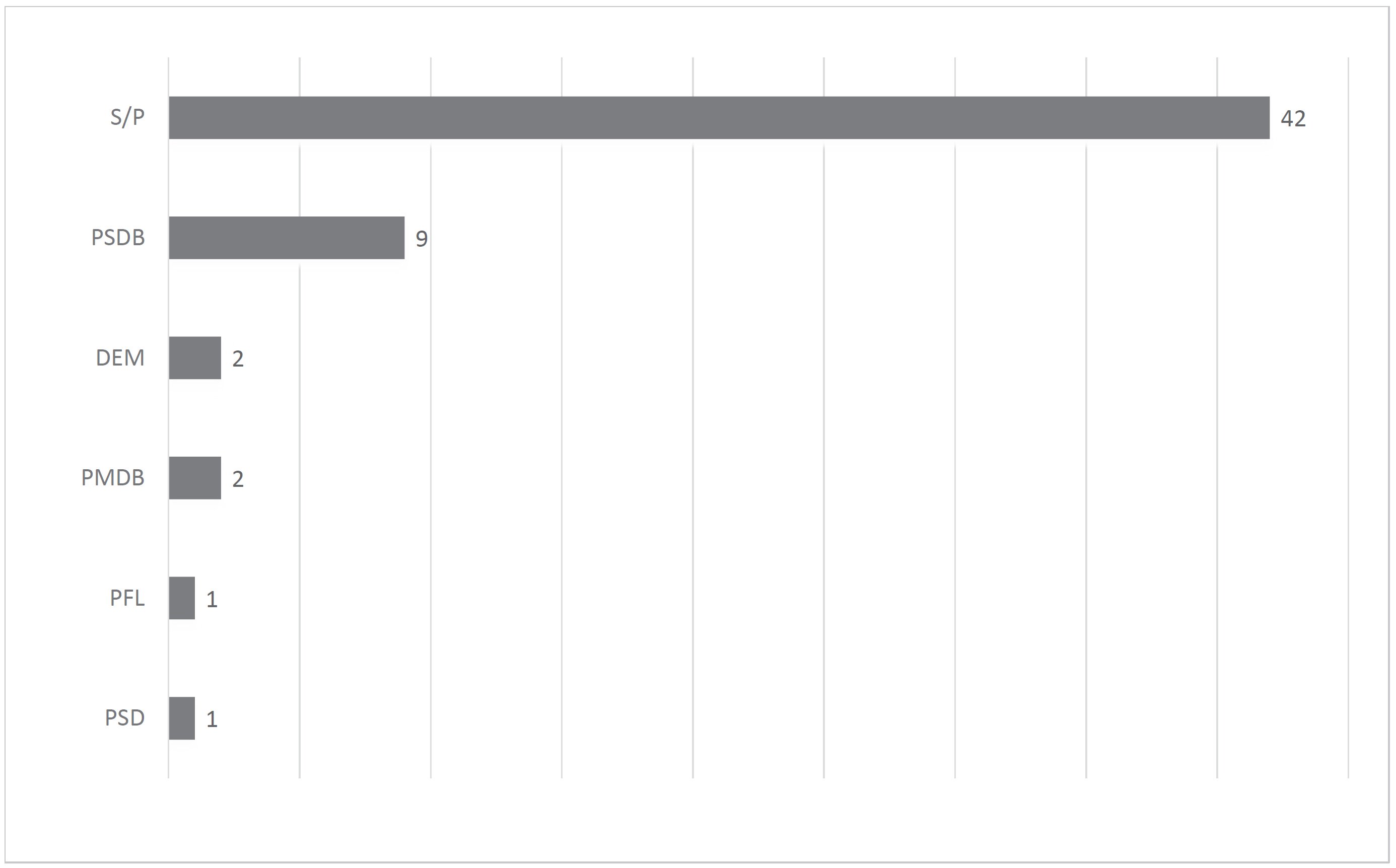

This article is organized into two analytical sections: the first addresses the political-partisan affiliations of the 60 subjects of the Management Team, generating Graph 1; and the second examines the circularity of the subjects in two periods: until 2002 and from 2003 onwards.

POLITICAL PARTY AFFILIATIONS

Berstein (2003, p. 69) understood that the political party emerges as a revealer of fundamental problems, in which its supporters seek the common point of solutions, as they become holders “[…] of a political culture which its members share and which gives rise to a tradition. Often passed down through generations.” In this way, the connection of subjects to the political parties that emerged, especially in the period after redemocratization, indicates the need for them to align themselves with organizations that translated their way of thinking, that is, to reaffirm the political culture they intended to constitute. According to the author, the political party is a historical phenomenon by definition and has the ability to provide the researcher with evidence about groups and subjects.

Thus, when analyzing the political party connection of the subjects of the MEC Management Team, a certain coherence was found regarding the ideological spectrum, mainly in alignment with the government's party coalition, as shown in Graph 1.

Most of the Management Team had no political party affiliation (S/P, 42 people on the team). Some of them were career civil servants of the MEC or from other ministries and were used in commissioned positions. Luciano Oliva Patrício (no party affiliation) represented one of these cases: before joining this team, as executive secretary, he held a position in the Ministry of Planning, but he was already in the Ministry of Finance, having been a fundamental subject in the creation of the Real Plan, which he considers the highest point of his career (Patrício, 2020).

Thus, Patrício was already known to Paulo Renato Souza3 and to president FHC himself, who understood that it was pertinent, in the composition of the MEC's staff, to include subjects who understood the fiscal issue in general and, specifically, in education. Even without being linked to the party coalition of the place of power, Patrício pointed out its importance: “[…] as Executive Secretary, I was number 2 in the Ministry of Education, taking over as interim minister in the place of Paulo Renato Souza. I carried out many acts as minister of education and participated in public policies that revolutionized Brazil” (Patrício, 2020, p. 1). The choice of Patrício as number 2 in the ministry also indicated a certain educational concept and the government's concern with public spending.

The fact that Patrício did not have a party affiliation was one of the aspects that allowed him to circulate in different governments: Collor, FHC, Lula, Dilma and Temer. However, there was an approximation of Patrício with the educational project of FHC, mainly because he considered that the educational policies developed in that period promoted an educational revolution in Brazil. Patrício's circularity was understood by him as an aspect of his survival in successive governments, especially since he had no party affiliation:

The FHC government was a very plural government, the Ministry of Health always had a very strong presence of people and ideas from the PT [Workers’ Party] and other left-wing parties; there was always room for that within the government. In the 2002 electoral campaign, Serra and Lula exchanged pleasantries about the support that the PT had given to EC 29, which substantially increased the Ministry of Health's resources, and then, throughout the Lula government, there was room for ideas and people who had contributed to the FHC government. I am a survivor of that time, I went from the first level of the FHC government, I stayed for a while in the second level of the Lula government, and I was able to contribute and I even had the opportunity to demystify many things, because those who are outside the government always imagine that the government is doing everything wrong, and that they could do better […]. So, I can say that one of the great fortunes I had was having the opportunity to help successive governments live with the history that came from previous governments. (Patrício, 2020, p. 2)

Patrício (2020) drew attention beyond the partisan issue in the composition of the Management Team: the way in which subjects are influenced by the space they occupy. In addition, he considers that it was a fundamental piece for the governments that came after FHC to understand the conflicting relationship between social policies and the fiscal issue.

Eunice Ribeiro Durham and Pedro Paulo Poppovic were two members of the MEC Management Team, also without partisan ties; however, they were part of the most important educational wing of the government. Durham was trusted by Paulo Renato Souza and by FHC4 and Poppovic; in addition to being personally close, she had close academic relationships with the president.

Durham, during the period in which she served as Secretary of Educational Policy at MEC, was a defender of the evaluation policies implemented at the beginning of the government (1996); however, when she joined the National Education Council (CNE), in 2001, there were tensions between her conceptions and those of the minister of education. She would have stated that her agreement with Paulo Renato Souza, with reference to “[…] basic education, was not repeated in relation to higher education”. (Durham, 2001, p. 1) The importance of understanding the place from which the subject speaks is evidenced by the professor herself, in a study published while she was in a place of power:

All authors have their own perspectives, which guide their judgment. Mine isn't completely free either. Therefore, I believe it is important to clarify that I was part of the Ministry of Education team from the beginning of this government until the beginning of 1997. Since then, I have been part of the National Education Council. I believe, however, that the agreement between the analyses I carried out before this government, while I was part of the opposition, my line of action in the Ministry and the considerations that I present here, shows that there was objectivity in the assessments of the recent evolution of the Brazilian educational system (Durham, 1999, p. 252).

Thus, it is understood that a place can change the subjects’ conceptions differently, even if they belong to the same space and are apparently aligned with regard to educational conceptions. Durham had a type of position when she was in the executive part of the government (with a commissioned position). However, from the moment she started to occupy a place with other characteristics — Deliberative Council, Chamber of Higher Education of the CNE (CNE/CES), in which, after being named, she had autonomy in her positions —, she started to have another type of understanding. As much as she agreed with the political agenda in relation to basic education, her conception with regard to higher education differed, as political cultures are not static and can change with transformations in subjects and perspectives.

The party independence (S/P), in general, and the academic relevance of the professor are indications that guaranteed her decision-making autonomy, even though she was aligned with the political-educational culture of the government, as she stated. Durham (2009, p. 4):

Besides, I am a resignation champion. I was at CAPES [Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel] and I resigned when José Goldemberg went to the Ministry and called me to be the Secretary of Higher Education. When Goldemberg resigned from the MEC, I resigned too. I came back due to a personal request from Fernando Henrique. I went to MEC with the commitment to do the university reform and I stayed for almost three years. As Paulo Renato gave up doing the renovation, because he was very enthusiastic about basic education, I resigned. I have to admit that basic education was actually more important than university reform, but I regret that it was not done. I was asked again to join the National Education Council when Gianotti left. I stayed there four years. I resigned again for disagreeing with the political guidelines that were being followed. I still believe that higher education reform was and is necessary.

Durham (2009) emphasized that she never wanted to pursue a political career, and that the political positions she held were offered to her. This corroborates the fact that she was called to occupy places of power due to her academic trajectory, mainly in relation to her studies on higher education, despite not being accepted by the Faculty of Education of the University of São Paulo (USP), which contributed to the discontinuity of her studies in this area.

The Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), FHC's party, naturally represented the largest affiliation of the Management Team, with nine members. The PSDB was founded after redemocratization and in the effervescence of political cultures that sought to establish themselves as predominant. Its emergence took place after a collective split between members of the Brazilian Democratic Movement (PMDB), understood as the most progressive wing of the party. For Roma (2002), the PSDB did not have its birth in the same way as the classic social democratic parties, as its origin took place far from popular movements, with parliamentary exclusivity.

The political conception of the PSDB was clear from its birth, especially with regard to its move from liberal to social orientation, according to Roma (2002, p. 74):

It is often said that the PSDB, from 1994 onwards, moved ideologically from a center-left to a right-wing position in the political space. This shift would be expressed in the redefinition of its political guidelines, leaving aside the social-democratic ideology to adopt a government program labeled as neoliberal. This shift to the right, with more market-friendly policies, would have been, above all, the cost that the party had to pay to reach the government and to govern in alliance with the PFL. However, contrary to popular belief, this liberal programmatic orientation was already clearly established from the beginning of the party.

The subjects of the MEC Management Team linked to the PSDB possibly positioned themselves on the side of governability; that is, they were inclined towards the liberal orientation due to the places around which they circulated — precepts assumed since the government project and deepened when they occupied the spaces in a place of power. These subjects, who were affiliated with political parties, had a certain understanding of the conceptions and principles on which the party was based. However, as highlighted by Berstein (2003), the link between subjects and parties did not always occur as a consequence of a concise alignment with their conception or ideological current. Sometimes, it is in the form of a diffuse political culture that the conception of the party is imposed on its members, through symbols, and even adopting slogans that characterized them as belonging to that group.

Maria Helena Guimarães de Castro, Gilda Figueiredo Portugal Gouvêa and Minister Paulo Renato Souza stood out as exponents of the PSDB in the composition of the MEC, considered as such by the president of the Republic himself:

Looking back, there was no sector of the ministry, and even of education in a broad sense, that passed unscathed to the action of the minister and his collaborators. It is hard to name which ones, because there were so many. But I certainly do not do injustice if I say that Maria Helena Castro, Iara Prado, Gilda Portugal Gouvêa and Pedro Paulo Poppovic count among them. (Cardoso, 2005, p. 17)

Cited by the president as a member of the main core of the MEC, Iara Glória Areias Prado was affiliated with the PMDB, a party that became part of the government coalition and was the most important in forming the basis for the approval of matters in the Legislative. Likewise, the president also mentioned the prominence of Eunice Ribeiro Durham (non-party) and Barjas Negri (PSDB) in the success of the educational project during the period in which he was in government:

All this was possible because the government and the minister, as well as their collaborators, had an idea of what they wanted, of the direction to be taken, within the democratic philosophy already highlighted. This mark has been seen since the fundamental battle that was the approval of the new Law of Directives and Bases of Brazilian Education, which would not have been won without the persistence of the ministry technicians, such as Eunice Durham, and the support of many parliamentarians, among which I highlight Senator Darcy Ribeiro. In the same way, if Paulo Renato were not an economist and did not have the valuable help of another economist, Barjas Negri, the [Fund for the Maintenance and Development of Elementary Education and the Valorization of Teaching] FUNDEF, which implied a true tax reform, including constitutional change, it would be unthinkable. (Cardoso, 2005, p. 18, bold emphasis added)

In this direction, the president, in a way, justified the prevalence of economists in the composition of the MEC Management Team, understanding that this area of training was essential for educational policies, especially those of financing, to have social and fiscal success. This understanding of FHC is an indication of the way education was thought of in his government, especially in the appropriation of concepts of State reform, such as efficiency, effectiveness and accountability.

The other parties present among the subjects of the Management Team were part of those that made up the government coalition. Thus, even if in the lower levels they were affiliated with opposition parties or linked to them — as shown by Patrício (2020) —, the main nucleus was not occupied by subjects with different thoughts and divergent educational conceptions. For the educational project developed since the campaign to be successful, an aligned composition was necessary.

In this way, political parties put themselves in a position of mediation between their representatives and politics, but they are not a reflection of the positions of the subjects that integrate them. The analysis of party links composes an analytical category to understand political culture but does not determine it.

CIRCULARITY OF THE SUBJECTS OF THE MANAGEMENT TEAM: UNTIL 2002 AND FROM 2003

In order to understand the constitution of the political-educational culture of this period, the subjects’ links to institutions of different natures were analyzed. Access to information on the circulation of 30 subjects from the Management Team was obtained (until 2002 and from 2003 onwards), as shown in Chart 1.

Chart 1 Subjects of the Ministry of Education Management Team in Figures 1 and 2.

| Subjects in Management Team | Position in MEC | Name(s) in figure(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Abílio Afonso Baeta Neves** | President of Capes/Secretary of Higher Education | NEVES, A. A. B. |

| Aldino Jorge Graef** | Special Advisor of Executive Secretary | GRAEF, A. J. |

| Antonio Emilio Sendim Marques*** | Director of Projeto Nordeste and Fundescola | MARQUES, A. E. S. |

| Antonio Floriano Pereira Pesaro*** | Secretary of Projeto Bolsa Familia/Fies | PESARO, A. F. P. |

| Atila Freitas Lira** | Secretary of Education, Media and Technology | LIRA, A. F. |

| Barjas Negri** | Executive Secretary of FNDE | NEGRI, B. |

| Carlos Alberto Xavier** | Cabinet Deputy Chief | XAVIER, A. C. |

| Carlos Eduardo Moreno Sampaio** | Director of Treatment and Dissemination of Educational Information | SAMPAIO, C. E. M. |

| Edson Machado de Sousa** | Cabinet Chief | SOUSA, E. M. |

| Eliana Graeff Martins** | Chief of Legal Advice | MARTINS, E. G. |

| Eunice Ribeiro Durham*** | Director of National Education Policy | DURHAM, E. R. |

| Fernando Henrique Cardoso* | President of the Republic | CARDOSO, F. H. |

| Francisco César de Sá Barreto*** | Secretary of Higher Education | BARRETO, F. C. S. |

| Gilda Figueiredo Portugal Gouvea** | Special Advisor/Interim Minister | GOUVEA, G. F. P. |

| Iara Glória Areias Prado** | Secretary of Basic Education | PRADO, I. G. A. |

| Iza Locatelli*** | Director of Saeb | LOCATELLI, I. |

| João Batista Gomes Neto* | Director of Treatment and Dissemination of Educational Information | NETO, J. B. G. |

| José Luiz da Silva Valente** | Director of Development of Higher Education | VALENTE, J. L. S. |

| Luciano Oliva Patrício** | Executive Secretary | PATRICIO, L. O. |

| Luiz Roberto Liza Curi*** | Director of Higher Education Policy of Secretary of Higher Education | CURI, L. R. L. |

| Maria Helena Guimarães de Castro*** | President of Inep | CASTRO, M. H. G. |

| Maria Inês Fini*** | Director of Enem | FINI, M. I. |

| Marilene Ribeiro dos Santos*** | Secretary of Special Education | SANTOS, M. R. |

| Mônica Massenberg Guimarães** | Executive Secretary of FNDE | GUIMARAES, M. M. |

| Paulo Renato Souza*** | Minister of Education | SOUZA, P. R. C. |

| Pedro Paulo Poppovic*** | Secretary of Distance Education | POPPOVIC, P. P. |

| Raul Christiano de Oliveira Sanchez** | Minister's Private Secretary/Director of Bolsa Escola | SANCHEZ, R. C. O. |

| Raul David do Valle Junior** | Secretary of Education, Media and Technology/Proep | VALLE JR, R. D. |

| Tuiskson Dick** | Director of Capes Programs | DICK, T. |

| Ulysses Cidade Semeghini** | Director of Monitoring of Fundef | SEMEGHINI, U. C. |

| Vanessa Pinto Guimarães** | Secretary of Higher Education | GUIMARAES, V. |

Source: The authors.

*Subjects only in Figure 1.

**Subjects only in Figure 2.

***Subjects in Figures 1 and 2.

Capes: Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel; Fies: Student Financing Fund; FNDE: National Fund for Educational Development; Saeb: National Basic Education Assessment System; Inep: National Institute for Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira; Enem: National High School Exam; Proep: Program for the Expansion of Professional Education; Fundef: Fund for the Maintenance and Development of Elementary Education and the Valorization of Education Professionals.

CIRCULARITY OF SUBJECTS UNTIL 2002

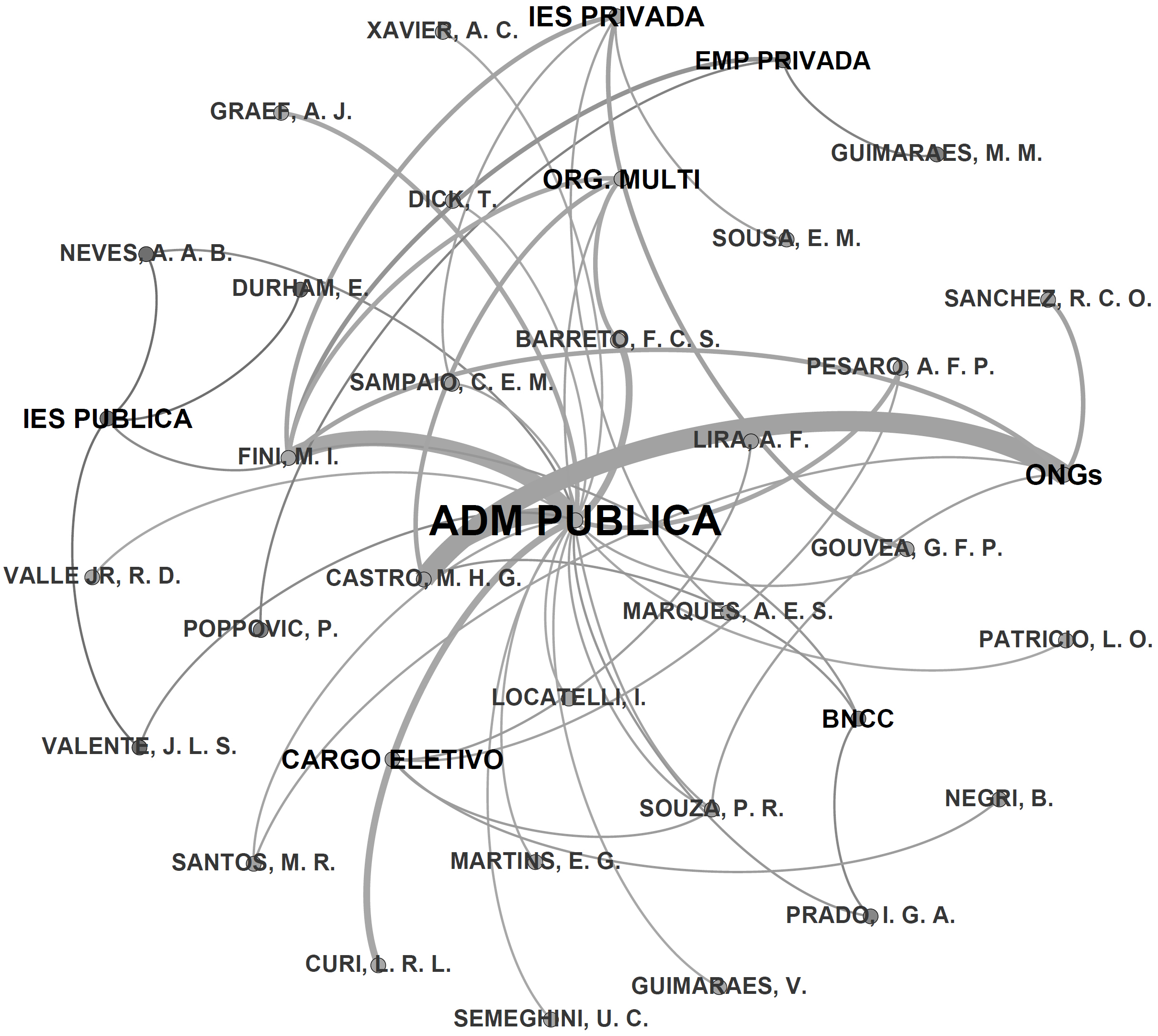

Considering the period until 2002, of the 30 subjects of the Management Team from which the information was obtained (Chart 1), 14 were linked to some type of institution, including associations, unions, societies and organizations of another nature, such as those with multilateral formation, as per Figure 1.

Source: The authors.

Figure 1 Institutions linked to the subjects of the Ministry of Education Management Team (until 2002).

According to Rioux (2003, p. 103), organizations that do not compete for the vote or for the direct exercise of power, “[…] on behalf of the interests they invoke in proportion to the pressure they exert on opinion and public authorities, not only have access to politics but contribute to structuring what political scientists call a political system”. Thus, although non-partisan organizations do not exert direct influences on the practices of the place of power, they contribute to the constitution of a political culture.

In this way, even the most unimpressive organizations should be considered, as their conceptions can somehow find resonance in subjects of relevance in the political scenario, and their activities are legible through the marks they leave in statements to the press, internal bulletins, annual reports or newspapers. From Figure 1, different types of organizations were identified: a) business — Grupo Abril; b) scientific — Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science (SBPC), Brazilian Academy of Sciences (ABC), Association of Scientific Societies (ASC), National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Social Sciences (ANPOCS), Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLASCO); c) economic — World Bank (WB), International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Organization of American States (OAS), Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP), Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA); d) educational — Association of Parents and Friends of the Exceptional Children (APAE), Brazilian Association of Anthropology (ABA), National Association of Directors of Federal Institutions of Higher Education (ANDIFES), Brazilian Association of Educational Assessment (ABAVE), National Union of Municipal Directors Education (UNDIME); e) multilateral — United Nations (UN), International Labor Organization (ILO); United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

The larger names (labels) represent a greater number of lines connected to them, that is, more subjects linked to these institutions, and the names in lighter gray correspond to the subjects of the Management Team. Emphasis is given to the UN, SBPC and BM — the first with four subjects with some type of association, and the second and third with three linked subjects. The UN, the SBPC and the WB stand out in the connection network that was formed by the links of the subjects and has Paulo Renato Souza and FHC as those who constitute its nucleus.

The institutions that appear in Figure 1 have their own educational concepts: some in defense of specific interests, such as ANDIFES, which seeks to position the interests of federal universities in the dialogue with the Federal Government, with the associations of professors, students, technical-administrative and civil society; others, with the aim of exerting influence on the development of educational policies, such as UNDIME, in the quest to represent municipal education at the federal level. The educational concept of multilateral organizations is observed through recommendations issued by its subdivisions, such as the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) of the UN.

IPEA, which appears linked to Antônio Emilio Sendim Marques — also associated with IBRD —, pointed to the educational concept and the need to combine issues related to the financing and development of education. The School Strengthening Fund (Fundescola), of which Marques was director, made up the list of five educational projects signed with the WB in that period, with the corresponding counterpart from the Brazilian government (Pinto, 2002).

The WB was another institution that played a leading role in Brazilian educational policies, generating a series of studies that sought to analyze its role (Leher, 1999; Silva, 2003; Barreto; Leher, 2008; Figueiredo, 2009; Mota Júnior; Maués, 2014). In Figure 1, the WB's connection appears with Maria Inês Fini, who was a consultant for the institution, with Minister Paulo Renato Souza, who composed its technical staff (director), and also with João Batista Gomes Neto, who had been its consultant since 1986.5

Fini (2019, p. 2), when answering in an interview with Revista Nova Escola about her experience as director of the National High School Exam (ENEM), related the preparation of the test to the experience that Paulo Renato Souza had abroad, when he composed the staff of the WB:

Minister Paulo Renato [Souza] wanted an exam very similar to that which exists today, modern, and which provided access to Higher Education. He had been a technician at the World Bank, and his children took a milder entrance exam, where they took the SIT [SAT], and he was very impressed. He wanted something similar in Brazil. […] he then wanted to create a reference for the completion of Basic Education.

What Fini (2019) called the SIT was, in fact, the Scholastic Aptitude Test or Scholastic Assessment Test, the SAT, as explained by the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (INEP) when relating it to the ENEM:

Another very important exam and more similar to ENEM is the SAT (Scholastic Aptitude Test or Scholastic Assessment Test). This is a standardized US educational exam, given to high school students, which serves as a criterion for admission to North American universities. (Brasil, 2011, p. 2).

In this sense, Fini's (2019) response, her relationships with the bank, as well as those of Souza and Gomes Neto (Figure 1), in addition to the emphasis that INEP gave to the US exam, indicated not only the inspiration of the national education leaders in the American model, but also the influence of the relationships that these subjects established with the multilateral organization (WB) in the constitution of the political-educational culture of that period.

The UN, the institution that appears at the center of Figure 1, exerted its influence as a multilateral organization through its entities (subdivisions) that operated in specific sectors, such as: International Monetary Fund (IMF), UNDP, ILO, ECLAC, UNESCO, UNICEF and the WB. With the exception of the IMF, the other mentioned entities appear in Figure 1 composing the list of associations of the subjects of the Management Team, which points to the strength of the influence exerted by the organization in the constitution of Brazilian policies, specifically educational ones. In response to the question about Brazilian educational policies being imposed by the WB and UNESCO, Cardoso (2014, p. 5) was emphatic:

Bolsa Família6 was also instructed by the World Bank! This type of comment is prejudiced because if the instruction is valid, we adopt it, if not, we discard it. This shows a provincial vision: to think that “what comes from outside is imposed by the World Bank”, as if Brazil were a country that did not have its own capacity to say what it wants and what it does not want, to adapt.

Thus, Cardoso (2014) used the very criticism, a recurrent one, of his government's educational policies to defend them. FHC argued that the periphery would have autonomy in relation to what comes from the center, in a simple movement of appropriation or rejection. However, the relationship between the center and a dependent periphery, in many ways, presupposes a fragile autonomy, although we understand that there is still no servile obedience. The question that must be asked is not in relation to the government's compulsory connivance with regard to multilateral organizations, but in relation to the alignment of the educational concept and the country project, in understandings that converge. Another point that drew attention in Cardoso's speech (2014) is what he says about “adapting”. It is believed that the former president was referring to the appropriation that was carried out in relation to the recommendations of multilateral organizations, which demonstrates an alignment of educational conception and political culture, even if not uniformly.

The OECD appears in Figure 1 linked to Maria Helena Guimarães de Castro. The OECD, especially with its International Student Assessment Program (PISA), influenced the development of Brazilian assessment policy, one of the main aspects of the conception of education for those who held a place of power, as explained by Castro (2016, p. 94):

In a joint initiative of UNESCO/Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), INEP became part of the World Education Indicators (WEI) program, with the objective of developing a basic set of indicators that would allow comparisons between countries. However, the most ambitious project of educational assessment, at the international level, is represented by the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), coordinated by the OECD. In mid-1997, INEP started to represent Brazil in the first OECD discussions on PISA 2000.

Castro (2016) highlighted the importance of the OECD and UNESCO in the integration of INEP to PISA, which points to the political-educational culture that was sought to be constituted, as well as to the importance of Brazil in the international scenario.

Accordingly, the government's adoption of an educational policy that sought to submit decision-making to the evaluation process recommended by multilateral organizations, in the search for quantifiable results, aimed to include the country in the globalized world, understanding that these data, in isolation, were sufficient for the design of educational policies. This perspective has been presented since the PSDB's Programa de Governo Mãos à Obra [Let's Get to Work Government Program] (PSDB, 1994, p. 59), of the 1994 presidential campaign, as explained in the topic on assessment:

To implement a national system for evaluating the performance of schools and educational systems to monitor the achievement of goals to improve the quality of education.

To define methodologies, objectives and goals for evaluating student performance in the various grades or stages of basic education.

To disseminate widely the results of the national assessment system.

The excerpt above refers to educational evaluation, but evaluation processes based on quantifiable metrics make up the entire government program: health, safety, economy and infrastructure. In the same way, it was planned to strengthen relations with multilateral organizations, such as the IDB, WB and OECD, which appear in Figure 1:

Historically, Brazil has been one of the main borrowers of the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank — IDB. With the stabilization of the economy and the regularization of relations with the international financial community, the resources of these organizations destined for Brazil may be expanded. (PSDB, 1994, p. 14, bold emphasis added)

Expand Brazil's participation in negotiations on the multilateral economic system within the scope of the new World Trade Organization (WTO), encourage cooperation with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and strengthen our presence in multilateral financial agencies such as the Monetary Fund International, the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank. (PSDB, 1994, p. 45, bold emphasis added)

Thus, the occupation of spaces by subjects (present in Figure 1) such as Paulo Renato Souza, Maria Inês Fini, Maria Helena Guimarães de Castro, Abílio Afonso Baeta Neves, João Batista Gomes Neto and Iza Locatelli, who had some kind of connection with these institutions and made up the place of power in the constitution of the strategy — a basis for the political-educational culture that was established —, happened due to the set of their characteristics. However, the fact that they are associated with multilateral organizations was a factor that contributed to composing the first echelon of the MEC.

The academic relevance of the subjects is also understood by their connections to institutions that aimed to strengthen specific areas or science in general. The SBPC, with three subjects connected to it (Figure 1) — FHC, Abílio Afonso Baeta Neves and Francisco César de Sá Barreto —, is an example of this movement and the government's concern to place subjects with preeminence and respectability in strategic places in scientific institutions.

The SBPC, since its creation (1948), has worked, together with the Executive and Legislative powers, in the development of laws and the release of resources for the progress and support of research and scientific dissemination, as highlighted by Alves (2018, p. 6):

Scientists from the SBPC played an essential role in the inclusion in the 1988 Constitution of the budgetary allocation for science and technology. During this process, the SBPC called on its regional secretariats to carry out the same work in the states with the constituent parliamentarians. Thus, most state constitutions started to include a budgetary link and established that foundations to support research would be created and maintained.

Thus, the occupation of subjects who participated in this process in protagonist places in educational policy reveals the attempt to ensure academic respectability not only for their trajectories and publications but also for the recognition of peers and organized movements for scientific strengthening.

In the same sense, ANPOCS, to which Eunice Ribeiro Durham was linked, was also one of the institutions representing Brazilian intellectuals. ABAVE was created at the end of the FHC administration, in 2001, and established itself as an institution responsible for maintaining the principles of the political-educational culture constituted since 1995. ABAVE appears in Figure 1, as subjects such as Maria Helena Guimarães de Castro and Maria Inês Fini were associated with it since its inception, but its effective relevance happened after the end of the FHC government, especially as a maintainer of the concept of education.

Thus, it is understood that the linking of subjects to institutions, organizations or associations took place on a voluntary basis, as the formation of sociability networks took place through the element of choice (Sirinelli, 2003). Intellectual itineraries can often occur without the conscious choices of subjects, but their insertions into sociability networks presuppose a voluntary gesture.

CIRCULARITY OF SUBJECTS FROM 2003

Analyzing where the subjects of the MEC Management Team circulated after the end of the FHC government (from 2003 onwards) allowed us to understand if the political-educational culture that was created from 1995 to 2002 was maintained, if it was re-signified in the appropriation processes, or if it was dismissed. The institutions of which they were/are part are indications of the way in which the political-educational culture they represented gained legitimacy or was weakened.

With the end of the FHC government, subjects began to occupy positions resulting from their actions, especially with the recently concluded government's alignment with the guidelines of these bodies (such as OECD, UN and WB). Thus, the influences exerted by these institutions began to rely on those who knew the educational policy from within the machine that operated it and were protagonists in the constitution of the political-educational culture of that period.

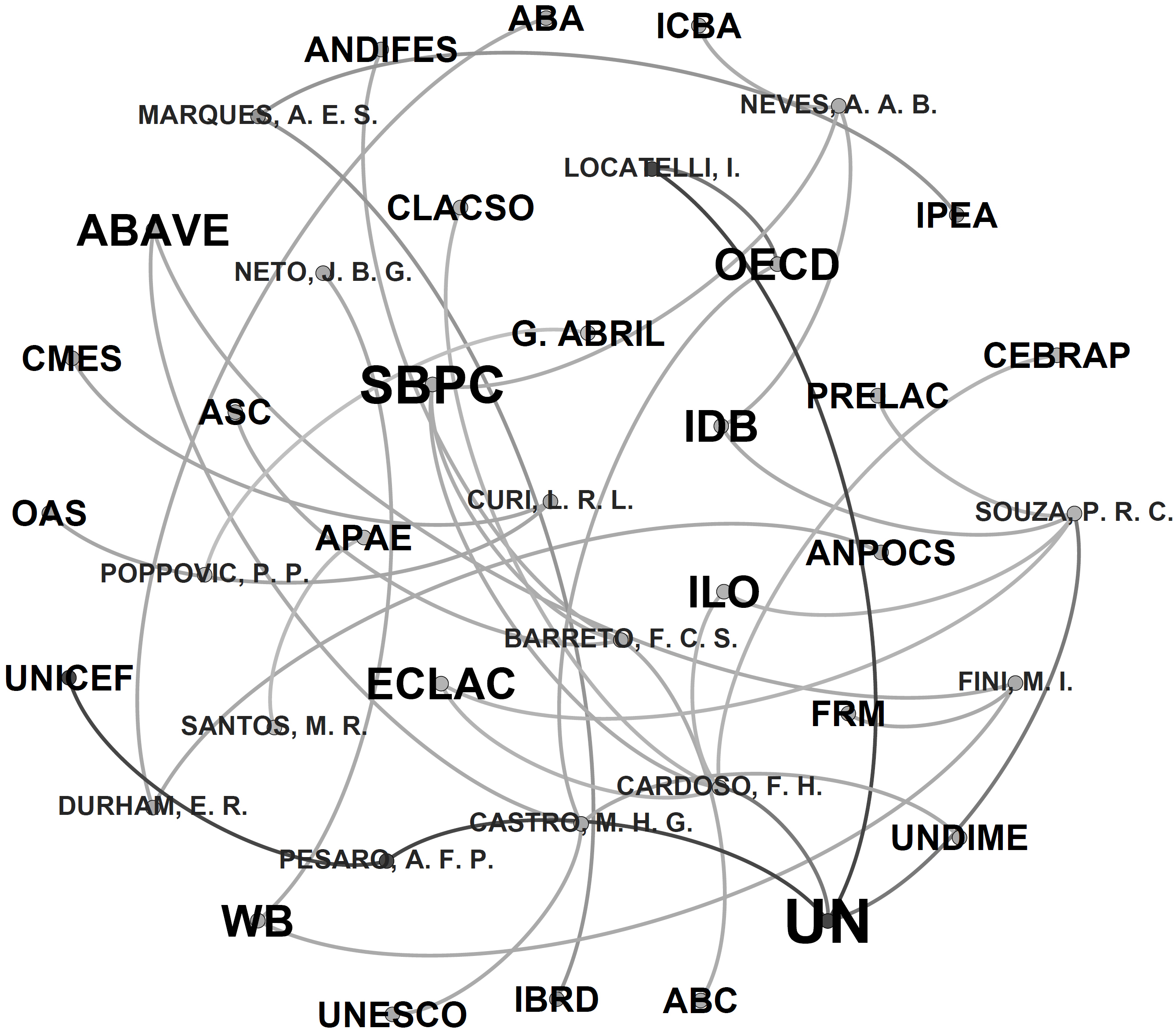

The circulation of subjects can be understood from seven groups of different natures: 1) private companies; 2) nongovernmental organizations (NGOs); 3) elected offices; 4) public administration; 5) private higher education institutions (HEIs); 6) public HEIs; and 7) multilateral organizations, as shown in Figure 2.

From Figure 2, the preponderance of public administration in the circulation of the subjects of the Management Team was identified. It was present in the trajectory of 21 out of the 30 analyzed. Some of these subjects were already effective public servants before occupying the spaces in the MEC (Patrício, L. O.; Neves, A. A. B.; Dick, T.; Sampaio, C. E. M.; Graef, A. J.). Others took up these spaces as a result of their work at the MEC or as a result of the influence and projection that being in the place of power gave them (Castro, M. H. G.; Gouvea, G. F. P.; Prado, I. G. A.; Santos, M. R.; Valle Jr., R. D.; Pesaro, A. F. P.; Guimaraes, V.; Barreto, F. C. S.; Martins, E. G.; Semeghini, U. C.; Fini, M. I.; Locatelli, I.; Curi, L. R. L.; Valente, J. L. S.; Graef, A. J.; Xavier, A. C.).

The association of the subjects of the Management Team to governments (state and municipal) that had an alignment of the political (and educational) conception to that of which they were part was the predominance among the 21 subjects who circulated in this category, such as Maria Helena Guimarães de Castro (the one with the most ties to public administration), who held the following positions: State Secretary for Social Assistance and Development of the State of São Paulo (2003–2006); Secretary of State for Science, Technology and Economic Development (SCTDE SP, 2006); Secretary of State for Education of the Federal District (SEEDF, 2007); Secretary of State for Education of São Paulo (SEE-SP, 2007–2009). She was also a member of the State Education Council of SP (2009–2010), in PSDB governments (in São Paulo: Geraldo Alckmin, from 2001 to 2006, and José Serra, from 2007 to 2010) and of the Democratas Party — DEM (in Distrito Federal: José Roberto Arruda, from 2007 to 2010). The professor returned to MEC again as president of INEP in the Michel Temer government, from 2016, and has been at the CNE/CEB since 2017.

Like Castro, Luiz Roberto Liza Curi is also in the educational public administration nowadays (beginning of 2021). The professor took office as CNE counselor in 2016 (May), during the Dilma Rousseff government, and was reappointed by President Jair Messias Bolsonaro in 2020.7 Francisco Cesar de Sá Barreto also occupies, even today, the CNE (2021), having been nominated in July 2016 for CES by Michel Temer.

In this way, it is understood that the political-educational culture constituted in the FHC government has remained represented in the public administration since the moment when FHC left power (in 2003). It now occupies either higher spaces in the education of states and municipalities (secretaries of Education), or municipal and state Boards of Education (and also the CNE), or even other public administration positions that were not related to education (for example, Raul David do Valle Junior was director of Urban Projects and Interventions at Emurb São José do Rio Preto, in 2006).

However, a subject was identified who continued in the same space in the transition of governments, namely Carlos Alberto Xavier, who was special advisor to Minister Paulo Renato Souza. He remained in the same position with Minister Fernando Haddad of the PT (from 2003). This point of congruence between the two Ministers of Education was repeated in 2006, when both were founding partners of the NGO Todos pela Educação [All for Education] —TPE.

Accordingly, the link between the subjects of the Management Team and the NGOs was present among five of them, as shown in Figure 2: Paulo Renato Souza, Maria Helena Guimarães de Castro, Marilene Ribeiro dos Santos, Raul Christiano de Oliveira Sanchez and Maria Inês Fini.8

Souza, Castro and Fini stand out as those who have (had)9 links with the NGO TPE. Souza and Castro were its founding partners and Fini is an effective partner of the organization. The TPE is configured as the most important organization influencing the development of Brazilian educational policies, sometimes guiding the agenda, since its foundation in 2006, when it had the document of its emergence (5 Metas do Todos pela Educação [5 Goals of All for Education]). Among the educational policies that had the NGO as an active subject were: the Education Development Plan (originating IDEB); the elaboration of EC 59 in 2009 (compulsory education from 4 to 17 years old); and evaluation policies (on literacy, in 2012). The NGO also pushed for the approval of the PNE 2014-2024, the approval of the BNCC (Brasil, 2017) and the National Curriculum Guidelines (DCNs) for teacher training (Brasil, 2019).10

Castro and Fini remain linked to the TPE even today, participating in conferences, meetings (webinars on Fundeb and education in times of a pandemic) and consulting (Fini and Castro contributed to the preparation of the recent Educação Já! [Education Now!], in 2018). In addition, Castro (with seven ties to NGOs) was part of Boards of Directors and established partnerships with other relevant NGOs, especially in terms of influencing the educational agenda: Instituto Natura, Instituto Braudel, Fundação Padre José de Anchieta, Fundação Bunge and Movimento pela Base Nacional Comum Curricular [Movement for the Common National Curriculum Base].

The link between these subjects and educational NGOs — TPE, Fundação Roberto Marinho and Instituto Natura, that supported recent educational reforms, especially the BNCC — points to support for curricular reforms that began in 2014, especially with the discussions around the BNCC. Castro and Fini figured as the most prominent subjects of the FHC period in support and participation in the entire process (mainly in the 3rd version) of the BNCC. The professors were part of the Management Committee of the BNCC. Iara Glória Areias Prado (Figure 2) was a critical reader of the final version of the document.

The multilateral organizations (ORG. MULTI) had the circulation of four subjects, as shown in Figure 2. In addition to Fini and Castro, who were on committees linked to UNESCO and the OECD, Souza was linked to the WB after the end of the FHC administration, not anymore as an employee of the institution, but in partnerships, consultancies and publishing about the period of his educational management on behalf of the bank (Souza, 2003). Barreto (Barreto, F. C. S.) was at the Financier of Studies and Projects (Finep)11 and at the Commission of the High-Level Scholarship Program of the European Union for Latin America (Alban).

More subjects from the Management Team could appear in Figure 2 linked to multilateral organizations, if any type of link was considered (such as publications and participation in congresses). However, for the composition of Figure 2, the official links of the subjects were taken into account (positions and participation in committees, for example).

The relationship of these subjects with these institutions extrapolated official positions. The text by Gouvêa et al. (2009), which had the participation of Sergio Tiezzi, Maria Helena Guimarães de Castro and Maria Inês Fini, in addition to Gilda Figueiredo Portugal Gouvêa, is an example of this, as it was published in a book promoted by the WB, IDB, United States Agency for International Development (Usaid), Institute for Advanced Studies (IEA) and Educational Reform Program for Latin America and the Caribbean (Preal). Entitled The Tinker Foundation and GE Foundation, its objective was “[…] to provide high-quality technical studies whose conclusions could be easily translated into educational policies” (Preal, 2009, p. 7). This publication is an indication of the understanding of these organizations on the educational policies of the FHC government, in addition to the fact that it was published in 2009, the year of the second term of the Lula government, which indicates the privileged place that the educational policy occupied in the 1990s to the detriment of the educational policy of the 2000s.

Higher education was also one of the destinations of the Manaagement Team subjects: Eunice Ribeiro Durham, José Luiz da Silva Valente, Abílio Afonso Baeta Neves, Maria Inês Fini circulated in public HEIs, and Antônio Emilio Sendim Marques, Edson Machado de Sousa, Carlos Eduardo Moreno Sampaio, Gilda Figueiredo Portugal Gouvêa and Maria Inês Fini in the private HEIs.

The professor Eunice Ribeiro Durham, despite having been one of the main sources of the government's theoretical consistency, at the end of FHC's mandates, did not circulate through different spaces (in relation to the professor's origin) destined to disseminate and maintain the political-educational culture of that period. She returned to USP (her academic origin) and dedicated herself to research. Durham had productions on higher education published after the FHC government, but this object was losing strength, especially after the end of her research group.12

It is understood that the position that the professor returned to occupy could also continue to influence Brazilian educational policies with studies, projects and guidance for masters and doctorates, which would disseminate her conception of higher education and education. However, this influence happened laterally, so that Durham was no longer at the center of national, state or municipal policy making. The professor is considered as the one who had the most academic profile among the subjects of the Management Team, especially among those who had education as the focus of their studies.

The Instituto de Educação Superior de Brasília (IESB) housed three of the subjects who circulated in private HEIs: Sousa, Sampaio and Marques. The passage of these subjects in the MEC contributed for them to occupy these spaces, in addition to keeping in circulation the political-educational culture developed in that period in the private sphere.

In private companies, Maria Inês Fini, Pedro Paulo Poppovic and Mônica Massenberg Guimarães circulated. Fini is Director of Strategic Operations at Efígie, an educational internationalization consulting firm, in addition to having her own consulting firm, F. & F. Educare. Guimarães has been with Fundação Santillana Brasil since leaving the FHC government in 2003. Fundação Santillana is associated with educational NGOs that seek to guide the Brazilian educational agenda, such as TPE. In a joint initiative with TPE and Editora Moderna, Fundação Santillana published the book Educação em debate: um panorama abrangente e plural sobre os desafios da área para 2019-2022 em 46 artigos [Education in debate: a comprehensive and plural panorama on the challenges of the area for 2019–2022 in 46 articles] (2019), in a clear attempt to guide Brazilian educational policies of the new government that had begun.

In elected offices, there are three subjects of the Management Team: Paulo Renato Souza, Barjas Negri and Átila Freitas Lira. Lira has been a federal deputy since 1987, having been licensed three times to assume the position of Secretary of Education of Piauí,13 circulating both in elected offices and in public administration. Lira's appointment to the MEC was merely political. At that time, he was affiliated with the Partido da Frente Liberal (PFL), an important party in the ruling coalition, and the appointment of these allies is an important move to make it happen.

Negri was elected mayor of Piracicaba (SP) from 2005 to 2013 and from 2017 to 2020 by the PSDB, and Souza was elected federal deputy in 2007, by the PSDB, preparing to assume the position of Secretary of Education of the State of São Paulo, in 2009.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Voluntary association reveals a relationship between “[…] constituted bodies and intermediary bodies” (Rioux, 2003, p. 129), sustaining the new aspirations of subjects, acting in the tensions, negotiations and disputes of the groups in relation to the place of power, in an attempt to reconstitute a cohesion of political cultures in a broader political culture (of the group). Thus, these connections show the influences on the constitution of the political-educational culture of the period (1995–2002), in addition to the very conception of education of the subjects in power.

With the end of the FHC administration in 2003, there was an expectation, on the part of the new elected government, of a new educational policy, with a different conception of education, which would be responsible for constituting a new project, establishing other theoretical and epistemological bases. Frigotto and Ciavatta (2003), Krawczyk (2003) and Ramos (2003) participated in the National Seminar High School: Political Construction, organized by Antonio Ibañez Ruiz, in 2003. It was a series of discussions with educators, researchers and scholars of secondary education to understand the diagnosis and establish a horizon for the last stage of basic education. However, Lopes (2004), even before completing one year of the Lula government, stated that there was continuity in the curricular policies implemented during FHC's period. He believed that there had not been the necessary breaks for the implementation of another educational project.

The political-educational culture of the subjects of the Management Team continued to influence Brazilian educational policy, so that the subjects that composed it circulated through important spaces after the end of the government which they were part of. It is understood that there was a cooling of this influence at the federal level during the period from 2003 to 2014, when these subjects were on the periphery instead of the center of federal educational policy. However, based on the BNCC discussions, they once again assumed a leading role in the national educational debate, when they reinforced the concept of education in the 1990s in a more profound way.

In this way, the circulation of subjects through different spaces and in positions capable of influencing educational policy, even if they were not in the place of maximum power of education (MEC), indicates the survival and certain maintenance of the political-educational culture constituted from 1995. Berstein (1998) believed that political culture cannot be changed abruptly, unless as a result of a drastic rupture in the political system, extending over time.

According to Sirinelli (2014, p. 47), “[…] a political ecosystem, a kind of link between an institutional device and a sociocultural foundation, is a living organism”. It arises in specific situations under particular determinants, but it also transforms as conditions and circumstances evolve. The political-educational culture created in the 1990s adopted new ways of staying active from 2003 onwards, due to different conjunctures in the political sphere. These alternatives were found by the subjects who were part of the process (Management Team or other people linked to the place of power), as well as the subjects were “found” by those who understood the education project established in the 1990s as the most appropriate for the country.

1As exemplified by Dante Henrique Moura e Domingos Leite Lima Filho (2017); Lisete Regina Gomes Arelaro (2017); Mônica Ribeiro da Silva (2018); Eliana Claudia Navarro Koepsel, Sandra Regina de Oliveira Garcia e Eliane Cleide da Silva Czernisz (2020), to name a few.

2Gephi is free and open-source software for viewing, analyzing, and manipulating networks and graphs. In the case of this study, it was used to understand the sociability networks formed by intellectuals from their connections to institutions of different types.

4Such proximity is understood from the interview Durham gave to Lilian de Lucca Torres (Durham, 2009).

5He participated in the following projects as a World Bank consultant: Projeto Nordeste II and III [Project Northeast II and III] (1992–1995); Projeto Qualidade da Educação [Project Quality of Education] in Minas (1993) and Paraná (1993–1994); Projeto Educacional [Educational Project] in Mexico (1991); Sectoral study — Secondary Education in Brazil (1988–1989).

6FHC refers to the Bolsa Família [Family Allowance] program, initiated under the PT government, as bringing together the recommendations of multilateral organizations that took place under his government with those that also took place under the PT government.

7Members of the government and its militancy were dissatisfied with this reappointment, as they would like a name more in line with their ideas. They believed that Luiz Roberto Liza Curi was too “progressive”.

8For identification of the subjects, see Chart 1.

10We also highlight Educação Já! (2018), a clear educational agenda of the organization and an attempt to impose the new PNE, especially with the expectations of greater room in the Bolsonaro government.

11Public company of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation aimed at promoting science, technology, and innovation. It has links with the OECD.

13Between 1995 and 1999, he was not a deputy, occupying the secretary of Middle and Technological Education of the MEC from 1995 to 1998.

REFERENCES

ALVES, M. C. A SBPC e as fundações de amparo à pesquisa. Ciência e Cultura, São Paulo, v. 70, n. 4, p. 8-10, 2018. Disponível em: http://cienciaecultura.bvs.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0009-67252018000400003. Acesso em: 20 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

ARELARO, L. R. G. Reforma do Ensino Médio: o que querem os golpistas. Retratos da Escola, v. 11, n. 20, p. 11-17, 2017. Disponível em: http://retratosdaescola.emnuvens.com.br/rde/article/viewFile/770/722. Acesso em: 21 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

BARRETO, R. G.; LEHER, R. Do discurso e das condicionalidades do Banco Mundial, a educação superior “emerge” terciária. Revista Brasileira de Educação, v. 13, n. 39, p. 423-436, 2008. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-24782008000300002&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt. Acesso em: 20 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

BERSTEIN, S. A cultura política. In: RIOUX, J. P.; SIRINELLI, J. F. (org.). Para uma história cultural. Lisboa: Estampa, 1998. p. 349-363. [ Links ]

BERSTEIN, S. Os partidos. In: REMOND, R. (org.). Por uma história política. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 2003. p. 57-98. [ Links ]

BERSTEIN, S. Culturas políticas e historiografia. In: AZEVEDO, C. et al. (org.). Cultura política, memória e historiografia. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 2009. p. 29-46. [ Links ]

BLOCH, M. Apologia da história: ou o ofício do historiador. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Editor, 2001. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. Brasília: MEC, 2017. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Nota técnica: Teoria de Resposta ao Item. 2011. Disponível em: https://download.inep.gov.br/educacao_basica/enem/nota_tecnica/2011/nota_tecnica_tri_enem_18012012.pdf. Acesso em: 31 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Resolução CNE/CP nº 2, de 20 de dezembro de 2019. 2019. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/docman/dezembro-2019-pdf/135951-rcp002-19/file. Acesso em: 21 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, F. H. Reflexões sobre a educação superior nacional e mundial. [Entrevista com Fernando Henrique Cardoso cedida a SILVA, E.]. Educação, v. 37, n. 1, p. 129-134, 2014. Disponível em: https://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/ojs/index.php/faced/article/view/15721. Acesso em: 18 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, F. H. Prefácio – Uma revolução silenciosa. In: SOUZA, P. R. A Revolução gerenciada: educação no Brasil: 1995 a 2002. São Paulo: Prentice Hill, 2005. p. xv-xviii. [ Links ]

CASTRO, M. H. G. O Saeb e a agenda de reformas educacionais: 1995 a 2002. Em Aberto, v. 29, n. 96, 2016. Disponível em: http://rbepold.inep.gov.br/index.php/emaberto/article/view/2604/2599. Acesso em: 17 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

CERTEAU, M. A escrita da História. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Forense Universitária, 2011. [ Links ]

CIAVATTA, M.; RAMOS, M. A “era das diretrizes”: a disputa pelo projeto de educação dos mais pobres. Revista Brasileira de Educação, v. 17, n. 49, p. 11-37, 2012. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-24782012000100002&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt. Acesso em: 18 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

CUNHA, L. A. Ensino médio: atalho para o passado. Educação & Sociedade, v. 38, n. 139, p. 373-384, 2017. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/es/v38n139/1678-4626-es-38-139-00373.pdf. Acesso em: 30 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

DURHAM, E. R. A educação no governo de Fernando Henrique Cardoso. Tempo Social, v. 11, n. 2, p. 231-254, 1999. Disponível em: https://www.revistas.usp.br/ts/article/view/12315/14092. Acesso em: 17 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

DURHAM, E. R. Apresentação. In: DURHAM, E. R.; SAMPAIO, H. (org.). O ensino superior em transformação. São Paulo: Nupes, 2001. p. 7-11. [ Links ]

DURHAM, E. R. Entrevista. Ponto Urbe: Revista do Núcleo de Antropologia Urbana da USP, n. 4, 2009. Disponível em: https://journals.openedition.org/pontourbe/1713. Acesso em: 19 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

FIGUEIREDO, I. M. Z. Os projetos financiados pelo Banco Mundial para o ensino fundamental no Brasil. Educação & Sociedade, v. 30, n. 109, p. 1123-1138, 2009. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/es/v30n109/v30n109a10.pdf. Acesso em: 10 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

FINI, M. I. Entrevista à Revista Nova Escola. [Entrevista concedida a] Revista Nova Escola. 2019. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/2OqA3wg. Acesso em: 10 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

FRIGOTTO, G.; CIAVATTA, M. Ensino médio: ciência, cultura e trabalho. Brasília: Ministério da Educação, Secretaria de Educação Média e Tecnológica, 2003. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, C. A micro-história e outros ensaios. Lisboa: Difel, 1991. [ Links ]

GINZBURG, C. Mitos emblemas e sinais. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1989. [ Links ]

GOUVEA, G. F. P.; FINI, M. E.; FINI, M. I.; CUCATI, S.; CABRAL, V.; DIAS JUNIOR, A. C.; TIEZZI, S. A Reforma do Ensino Médio no Brasil: 1999-2005. In: CUETO, S. (org.). Reformas pendientes en la educación secundária. Santiago: Fondo de Investigaciones Educativas - Preal, 2009. v. 1, p. 115-179. [ Links ]

KOEPSEL, E. C. N.; GARCIA, S. R. O.; CZERNISZ, E. C. S. A tríade da Reforma do Ensino Médio brasileiro: Lei nº 13.415/2017, BNCC e DCNEM. Educação em Revista, v. 36, p. 1-14, 2020. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/j/edur/a/WzZ7F8ztWTshJbyS9gFdddn/?lang=pt. Acesso em: 16 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

KRAWCZYK, N. A escola média: um espaço sem consenso. In: FRIGOTTO, G.; CIAVATTA, M. (org.). Ensino médio: ciência, cultura e trabalho. Brasília: MEC, Semtec, 2003. [ Links ]

LEHER, R. Para fazer frente ao apartheid educacional imposto pelo Banco Mundial: notas para uma leitura da temática trabalho-educação. Trabalho e Crítica, v. 1, n. 1, 1999. [ Links ]

LOPES, A. C. Políticas curriculares: continuidade ou mudança de rumos? Revista Brasileira de Educação, n. 26, p. 109-118, 2004. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbedu/n26/n26a08.pdf. Acesso em: 25 fev. 2021. [ Links ]

MOTA JUNIOR, W. P.; MAUÉS, O. C. O Banco Mundial e as políticas educacionais brasileiras. Educação & Realidade, v. 39, n. 4, p. 1137-1152, 2014. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2175-62362014000400010&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt. Acesso em: 15 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

MOTTA, V. C.; FRIGOTTO, G. Por que a urgência da reforma do ensino médio? Medida Provisória nº 746/2016 (Lei nº 13.415/2017). Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 38, n. 139, p. 355-372, abr.-jun. 2017. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/es/v38n139/1678-4626-es-38-139-00355.pdf. Acesso em: 23 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

MOURA, D. H.; LIMA FILHO, D. L. A Reforma do Ensino Médio: regressão de direitos sociais. Retratos da Escola, v. 11, n. 20, p. 109-129, 2017. Disponível em: http://retratosdaescola.emnuvens.com.br/rde/article/view/760/pdf. Acesso em: 23 out. 2021. [ Links ]

PATRICIO, L. O. Entrevista à Rádio Difusora. São Paulo. 14 jan. 2020. Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gt6HDsoqS5Q. Acesso em: 21 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

PINTO, J. M. R. Financiamento da educação no Brasil: um balanço do governo FHC (1995-2002). Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 23, n. 80, p. 109-136, 2002. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/es/v23n80/12927.pdf. Acesso em: 20 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

PREAL. Reformas pendientes en la educación secundaria. Preal. Santiago: Editorial San Marino, 2009. [ Links ]

PARTIDO DA SOCIAL DEMOCRACIA BRASILEIRA (PSDB). Mãos à obra, Brasil: proposta de governo. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Edelstein de Pesquisa Social, 1994. [ Links ]

RAMOS, M. N. O projeto unitário de ensino médio sob os princípios do trabalho, da ciência e da cultura. In: FRIGOTTO, G.; CIAVATTA, M. Ensino médio: ciência, cultura e trabalho. Brasília: MEC/Semtec, 2003. [ Links ]

RIOUX, J. P. A associação em política. In: RÉMOND, R. (org.). Por uma história política. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV, 2003. [ Links ]

ROMA, C. A institucionalização do PSDB entre 1988 e 1999. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, v. 17, n. 49, p. 71-92, 2002. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-69092002000200006&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt. Acesso em: 21 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

SILVA, M. R. A BNCC da Reforma do Ensino Médio: o resgate de um empoeirado discurso. Educação em Revista, v. 34, p. 1-15, 2018. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102-46982018000100301&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt. Acesso em: 21 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

SILVA, M. R. Competências: a pedagogia do “novo ensino médio”. São Paulo: Cortez, 2003. [ Links ]

SIRINELLI, J. F. Os intelectuais. In: RÉMOND, R. (org.). Por uma História Política. Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ, 2003. [ Links ]

SIRINELLI, J. F. Abrir a história: novos olhares sobre o século XX francês. São Paulo: Autêntica, 2014. [ Links ]

SOUZA, P. R. The reform of secondary education in Brazil: background paper for expanding opportunities and building competencies for young people: a new agenda for secondary education. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2003. [ Links ]

SOUZA, P. R. A revolução gerenciada: educação no Brasil 1995-2002. São Paulo: Financial Times BR, 2005. [ Links ]

TODOS PELA EDUCAÇÃO (TPE). Educação Já!: sistema de cooperação federativa na educação. São Paulo, 2018. Disponível em: https://www.todospelaeducacao.org.br/_uploads/_posts/165.pdf. Acesso em: 10 dez. 2020. [ Links ]

TODOS PELA EDUCAÇÃO (TPE). Educação em debate: Um panorama abrangente e plural sobre os desafios da área para 2019-2022 em 46 artigos. São Paulo: Editora Moderna, 2019. [ Links ]

Received: April 05, 2021; Accepted: February 09, 2022

texto en

texto en