Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Brasileira de Educação

Print version ISSN 1413-2478On-line version ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.27 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub Dec 23, 2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782022270116

ARTICLE

While you were (not) asleep: negotiation of times, routines, and rhythms through the infant’s transition process to early childhood and care

IUniversidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil.

Infants coming into early childhood education services is a growing phenomenon that has captured greater interest from researchers. However, moving beyond the focus on maternal separation, the field still needs to advance regarding the notion of transition as a process of contextual intertwining between home and early education services. One of the dimensions of transition relates to the multiple temporal, cultural, and socially circumscribed dimensions that come to establish a new everyday life. Based on a cultural-historical approach, we discuss the transition process of a focal infant. From a thematic selection centered on sleeping routines, we address the relational negotiation against the (a)synchrony of times, routines, and rhythms that materialize in the institution’s present time. Among the different elements, the thematic selection will be focused on sleep routines.

KEYWORDS transition; early childhood education services; infant; time; routines

O ingresso de bebês em instituições de educação infantil é um fenômeno crescente que vem ganhando maior interesse de pesquisadores. Contudo, para além do foco na separação materna, o campo ainda precisa avançar na noção da transição como um processo de entrecruzamento entre os contextos casa-creche, sendo um dos seus elementos constitutivos as múltiplas dimensões temporais, cultural e socialmente circunscritas, que se estabelecem a partir de um novo cotidiano. Com base em uma abordagem histórico-cultural, discutimos o processo de transição de um bebê-focal do ponto de vista da negociação relacional frente aos (des)compassos de tempos, rotinas e ritmos que se materializam no tempo presente da instituição. Entre os diferentes elementos, o recorte temático estará centrado nas rotinas de sono.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE transição; creche; bebê; tempo; rotinas

El ingreso de bebés en instituciones de educación infantil es un fenómeno creciente que viene ganando mayor interés de investigadores. Sin embargo, además del enfoque en la separación materna, el campo aún necesita avanzar en la noción de transición como un proceso de entrelazamiento entre los contextos hogar-guardería, siendo uno de sus elementos constitutivos las múltiples dimensiones temporales, culturales y socialmente circunscritas, que se establecen a partir de la nueva rutina. Desde un aporte histórico-cultural, discutimos el proceso de transición de un bebé principal para informar sobre la negociación relacional frente a los (des)ajustes de tiempos, rutinas y ritmos que se materializan en el tiempo presente de la institución. Entre los diferentes elementos, el corte temático es de en las rutinas del sueño.

PALABRAS CLAVE transición; guardería; bebé; tiempo; rutinas

Historically, the cultural, social, and political constitution of children and infants as subjects of history and rights has become more consolidated in intertwining with the construction and strengthening of a public childhood education proposal that is structured and based on State guidelines. In the Brazilian scenario, this has taken place across a transformative course of a highly complex historical and political process. Some of the indicated transformations consist of changes in family organization and its everyday living; immigration processes; reformulations of law and labor relations; the acknowledgment of children aged from 0 to 6 years as subjects of rights who should have prioritized access to care and protection; the effort to overcome traditions of philanthropy and assistencialism inherited from collective childcare institutions; and the inclusion of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) as part of the public education system, holding the State accountable for guaranteeing access to qualified care (Brasil, 1988; Brasil, 1996; Amorim and Rossetti-Ferreira, 1999; Amorim, 2013; Kuhlmann Jr., 2015).

In this complex scenario, new conditions of care and education of children throughout their first years of life have begun to be gradually built, structured, and consolidated (Amorim and Rossetti-Ferreira, 1999; Barbosa, 2010; Rosemberg, 2015). This has reverberated in cultural and social changes and led to an increasing search for childhood education services, including those offered to infants (Haddad, 2002; Brasil, 2020) through which care and education became shared between institutions and families. This movement has brought forth the challenge to structure guidelines, indicators of quality, proposals of functional practice, and planning of an adequate context for childhood (Brasil, 1996; Campos and Rosemberg, 2009; Gobbato and Barbosa, 2017; Cestaro and Santos, 2018). The challenge of welcoming and integrating infants into an institutional and collective everyday life has been posited, and that has encouraged researchers to investigate further the process comprising the enrollment and the initial attendance of infants in such institutions, which has been addressed as the transition process.

To overcome the connotation of individual “adaptation”, the notion of transition has been coined to consider the situation in its complexity and plurality, surpassing the infant’s transformations and hence including the family, teachers, and the institution itself (Amorim et al., 2004; Coelho et al., 2015; Dentz et al., on press). As a cultural and social phenomenon, the integration of infants into ECEC settings has been indicated as a paving process between the public and private spheres, which removes the children from a condition of isolation from social life and places them within a broader scenario of socialization and cultural formation (Kernan, 2010; Hedegaard and Ødegaard, 2020; Costa, Rossetti-Ferreira and Mello, 2021).

In this sense, the transition process is constructed through a transactional movement that leads to the reunion of different people (relatives, infants, teachers, and employees) and contexts (household, daycare facility, work market, etc.) that gradually come to bridge a common routine based on the sharing of time and space (Barbosa, 2013; Dentz et al., on press). The establishment of this new shared everyday life requires new times and rhythms, the connection between past experiences and future expectations, the prediction and structure of routine scenarios, and the planning of actions regarding the strategies to welcome the infant.

Regarding the temporal aspect of the transition, some studies emphasize the different moments that compose the transition process to ECEC: the one before the beginning (first contact of the family with the institution), when the infant starts attending the institution, and the sequence of this attendance (Dentz et al., on press). Among these moments that encompass the process, the one most often approached by the literature is the beginning of attendance, especially the first week, for which the literature proposes: a shorter time of stay on the first day, with a gradual increase on the following days and flexible hours (Vitória and Rossetti-Ferreira, 1993/2013; Peixoto et al., 2015; Grande et al., 2017); and more attention to the moments of meeting and saying goodbye to the parents in the arrival and departure (Comotti and Varin, 1988; Rapoport, Bossi and Piccinini, 2018). Specifically, regarding the routine at the beginning of attendance, authors suggest giving infants signs of predictability, which can include rituals of music and ludic activities (Mauvais, 2003), to foster interactions between teachers and peers (Picchio and Maier, 2019). For example, a practice of special importance according to Peixoto et al. (2015) is that, at the beginning of attendance, at the institution, the teachers should incorporate the same care routine carried out at home by the family with the infant.

The focus of the literature often lies on strategies that intend to minimize the negative impacts of separating the baby from family members (Bossi et al., 2014; Klette and Killén, 2018; Martins et al., 2014; NICHD, 1997/2006; Vercelli and Negrão, 2019), especially the mother, and how the teacher should create bonds with this infant to prevent them. In this sense, special attention has been dedicated to the first days, emphasizing the importance that the process be conducted gradually. In the different periods when the infant is at the ECEC institution, it is important to pay attention to the moments of arrival and departure because of the separation/reunion with the mother. Therefore, the periods that tend to be considered in studies about transition are those around the process of separation of infants and family members, to a point in which even the matter of acceptance or rejection of the institutional routine ends up being more examined through the lenses of socio-emotional adjustment (or not) during the time of separation (Martins et al., 2014; Bossi, Brites, and Piccinini, 2017).

It is important to emphasize, however, that the transition also tackles the challenge of integrating the baby and the family into the institutional routine, and that the process requires the reorganization of their flow of life (Amorim et al., 2004). While establishing this new everyday life, it is necessary to deal with scenarios, routines, schedules, and people that can be very different from those that were known before (Rossetti-Ferreira et al., 2008). Besides, the infant comes to be inserted in a context that operates under a collective nexus that substantially impregnates and changes the forms of organization of time and space (Pairman, 2018).

Therefore, in terms of transition as the construction of a new everyday life and as a sociocultural transaction, the matter of constituting time practices, such as the establishment of rhythms and routines, is not usually as explored or analyzed as it should be. Authors point out that the lack of problematization may lead to the risk that such practices become fragmented and mechanical, without proper consideration of the infant’s trajectories and the broader institutional and social conditions found in the practices of time regulation in ECEC institutions (Barbosa, 2000; 2010; 2013; Birkeland, 2019). Also, the relational dynamic between multiple interlocutors (White et al., 2020) who participate inside and outside the ECEC institution is lost, as well as the transactional flow between the different parties, which enables the negotiation or even the reformulation of the propositions.

In this sense, the daily transit between different localities, temporalities, and structure of daily actions throughout the infant’s back-and-forth transit from home to the ECEC institution emphasizes the matter of establishing different routines and rhythms as a point of analysis for the transition process. Therefore, this article aims to discuss how temporal arrangements constitute the transition process of the infant to ECEC through the encounter and negotiation of different temporal periods which become materialized in the routine and display the contrast of times and rhythms between the families, the child, and the institution.

METHODOLOGY

This study derives from doctoral research projects (Costa, 2021; Dentz, 2022) connected to a larger project (Amorim, 2016). By investigating multiple case studies (Yin, 2005), we aimed to analyze some of the many dimensions related to the transition process of infants who went from exclusive household care to that shared with collective institutions, such as ECEC settings.

The main project was approved by the Brazilian National Research Ethics Committee (No. 60076516.9.0000.5407) and the aforementioned doctoral projects were approved by a local Research Ethics Committee (Certificates of Ethical Appraisal Submission - CAAE No. 68655317.9.0000.5407 and No. 60077616.9.0000.5407), according to guidelines from Resolution No. 466/12 of the Brazilian National Health Council. With the consent of the institutions and the research participants, the data were organized and stored in a database, composing a common empirical material to be analyzed considering different investigative questions related to the subject of the transition. Authorization was granted by the participants (the authorization of participation of the infants was granted by their guardians) for the use of the data and images that will be presented here. The names are fictitious.

The data were generated based on the longitudinal follow-up of focal infants who were in the process of starting at an ECEC institution. The collection consisted of video recordings and non-directive observation of the pivotal subject on different dates throughout their first school year in an institution, and here more specifically, a daycare center.

The records of each collection section comprise video recordings (nearly two hours per collection) of routine moments (arrival, sleeping moments, changing, bath, meals, departure), interactions (between infants, teachers, relatives, and other people), and moments attributed to playtime. The observation forms contain the description of the action flow and infant’s interaction, as well as the routine experienced on that day, indicating the time at which events took place. Besides these records, the transcription of the first interview with the parents was also analyzed.

In this article, we highlight the records of the three first collection dates of a single case study, which correspond to the first day, second week, and end of the first month of an infant’s attendance, whom we will call Sofia.

FOCAL PARTICIPANT AND CONTEXT

Sofia was an infant (6 months and 13 days) who lived with her two parents and an older sister. She was enrolled in a philanthropic daycare center located in a city in the state of São Paulo. The search for this service was owed to the fact that the mother had to work. The institution held a public-private partnership with the municipality, and due to being located near an industrial district, it received a significant contingent of families of workers from this sector. The group of infants in this daycare center was composed of 20 infants and three teachers who, respectively, attended and worked full-time.

THEORETICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL REFERENCE

This study is based on the theoretical-methodological perspective from the Network of Meanings (RedSig), grounded on the cultural-historical framework (Werebe and Nadell-Brulfert, 1986; Valsiner, 1987; Vigostki 1991; 1993). Such an approach was elaborated considering the dialogue between theory, research, and praxis produced through a collective enterprise among its authors and ECEC professionals, aiming to build knowledge about the development of young children and infants in ECEC institutions (Rossetti-Ferreira et al., 2008).

RedSig conceives human development as a phenomenon that unfolds in and through the multiple relations that exist in a mesh of semiotic elements that are dialectically interrelated and include the several practices and conceptions around the most basic constitutive processes of the person. This implies that development always takes place in culturally organized and socially regulated contexts (Rossetti-Ferreira, Amorim and Silva, 2000).

In these contexts, the possible action flows are structured, enhanced, or limited by the action of/with the other, through the articulation of several elements (organic, physical, material, interactive, symbolic, etc.). Such an articulation, from the point of view of constraints as channeling, may facilitate or hinder specific modes and processes of (co)constitution (Rossetti-Ferreira, Amorim and Silva, 2004; Silva, Rossetti-Ferreira and Carvalho, 2004). All of these processes are immersed within a social and historical matrix that interconnects the micro and macro social dimensions of the processes. This matrix becomes concrete in the here and now of the different situations and events that manifest themselves in their contextual, personal, and interactive components, which are intertwined in a mutual constitution that leads to the continuous production and transaction of meanings (Rossetti-Ferreira, Amorim and Silva, 2004).

The developmental processes are always situated within space-time contexts, so that time and space constitute an inseparable binomial. Time manifests itself through several temporal dimensions that simultaneously inscribe themselves in the here and now of events, in the proposals of space-time organization, in the modes of relations, and in the institutional practices, thus evoking, updating, and projecting elements in the present time, living time, historical time and prospective time (Rossetti-Ferreira, Amorim and Silva, 2004). In this sense, the visibility of the here and now situations includes a temporal whole, in which it is possible to identify the intertwined signals from a historical time; the transformations from the lived experiences; and the expectations/collective and individual goals that dialogue with the interpersonal practices that occur in the present time and place (Rossetti-Ferreira, Amorim and Silva, 2004).

Therefore, our understanding is that transition involves several time scales and maintains itself in constant transformation based on a succession of events, development of new skills, and persistence or rupture of specific modes of relationship. In this movement, the transition process and its multiple components can be re-signified and restructured, “[…] leading to the availability/construction of new significations/skills/relations of the involved parties.” (Amorim et al., 2004, p. 155).

By recognizing the challenge for the researcher to contemplate the vastness of elements in their complexity, the focus of the analysis will contemplate a thematic selection to which research instruments and tools should be employed to provide visibility to the multiple and dynamic constitution of the processes and their complexity (Rossetti-Ferreira et al., 2008). Therefore, the construction of the corpus of analysis was based on the aforementioned perspective and its theoretical-methodological assumptions.

CORPUS CONSTRUCTION AND ANALYSIS PROCEDURE

Due to our familiarity with the case of the focal infant, for this study, we have selected sleeping routines as the focus of the analysis, given their connection with previous experiences of the infant and the structure of the contextual schedule of the daycare center. Based on this theme, we raise issues that are brought forth before enrollment, and, from the start of attendance, we characterize and map the different sleeping routines in the morning in terms of the institutional proposition of sleep or wake periods during the morning period.

For this purpose, inspired by the methodology employed by Silva and Muller (2017), we indicate the uses of sleeping time employed both by the institution and by the focal infant throughout three collections during the first month of attendance. Based on this mapping, we sought to understand how the infant acted concerning this routine proposition and the thereafter interactive implications. Hence, we pursued to identify how the here and now of the sleep-wake routines proposed by the institution and Sofia’s particular rhythms brought multitemporal evidence, and how the space-time regulation of the institution, such as the “temporal meanings”, revealed itself in Sofia’s transition flow during the first month.

RESULTS/ANALYSIS

THE FAMILY AND TIME PRIOR TO THE ENROLLMENT

In the initial interview, the parents reported that Sofia had gone through long periods of somnolence because she had been born premature and that she commonly stayed in the crib or the stroller in her day-to-day. They also reported expecting that the daycare center would contribute to Sofia’s development, considering the positive experiences they’d had with their older daughter at the same institution. They believed that one of the ways that the institution could help was through the establishment of routines. The topic stands out during the interview as the word was mentioned 17 times. In one of the excerpts, reproduced below, the mother indicates that, at home alone with the child, it is hard to maintain the constancy of routines, whereas she expects that, in the daycare center, this would be more likely to be implemented:

Mother: And at the daycare, the routines, you know, because at home we don’t have them. And for Berenice (older sister) it was very good, so I believe it will be good for Sofia too. I try to create a routine, but they take us off of the routine [laughter].

Researcher: You mean to have specific times to do each thing?

Mother: Yes, you know, because when we are alone, we can’t keep that routine for each thing […] So I think it is good for them to have a routine. I believe that going there is better than staying at home […].

The mother also reports that she believes it will be easier for her daughter to get used to the new routine in the daycare center because she is still a baby:

Mother: [...] I think it is easy because they are still very young. For me, I prefer it […] to enroll her now, because for them it is a little easier because they are still learning their development, than later when they’ve already learned the different routines of the house. […] Because now they get used to the routine a bit easier than when they are a little older.

The expectations regarding the transition include imaginative anticipation of scenarios about what the infant might need and experience and relate to expectations of how the institutional functioning will be connected to that child and meet his or her needs (White et al., 2020; Winther-Lindqvist, 2021). Through expectations, the conceptions which are semiotically generated, culturally shared and socially valued emerge and materialize themselves in the constitution of a contextualized present time, which begins to circumscribe the construction of social exchange throughout time (Scorsolini-Comin and Amorim, 2008).

In this sense, from the time before enrollment, the relationship between transition and routine is indicated as being a different aspect in the contrast between the household and institutional contexts. The specificity of the group context and a larger division of tasks among adults are aspects anticipated by the mother as something that will enable more stable routines, which is understood, also in the social corpus, as something desirable for the infant’s development. Besides, the expectation that the younger infant can get more easily used to the changes in routine, in a certain way, channels the moment/age in which the mother decides to enroll her daughter in the institution.

Considering these elements that appear even before enrollment, we now turn to the characterization of the institution and its structure of the reception period, focusing more closely on the morning routine.

THE INFANT-INSTITUTION ENCOUNTER AND THE TIMES OF RECEPTION AND EARLY ATTENDANCE

The institution in which Sofia was enrolled destined a single, large room for the group of infants, which was internally subdivided composing two large distinct areas: one for baths, changing, and meals; and another one, larger, equipped with a rubber mat for the infants to stay on (which used to be on the floor). As a transition strategy, the early attendance of infants was staggered throughout the first week, with a few infants starting per week, and their stay increasingly progressing. The parents did not enter this group’s room, not even during the reception week. The conversations between parents and teachers about the infant’s routines and habits usually happened at the time of arrival and departure and were usually spontaneous after specific events of the day.

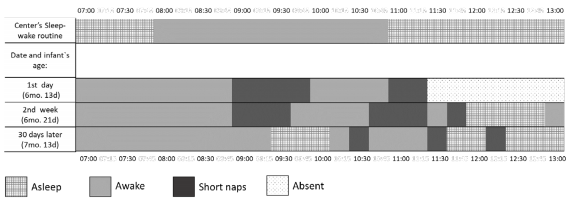

This institution operated in a full-time regime: the daily attendance was initiated at 7 a.m. and ended at 4:30 p.m. However, due to the focus of this article, we will only discuss the morning routine, which is shown in Chart 1, and we will proceed to a more detailed characterization of the sleeping routines. As soon as the infants arrived, they were placed in car seats for sleeping for a short period, from 7 to 8 a.m. One of the reasons why the institution had established this first sleeping moment, upon arrival, was because of the parents’ working hours, which required the infants to wake up very early before going to the center. Following this nap, the infants woke up, or were woken up, at 8 a.m., then were bottle-fed and afterward moved on to the routine designated as “playtime”. During this period, the teachers divided themselves between staying and playing with the infants in the room and working on baths and diaper changes. At 10 a.m., the teachers would place the infants on the car seats, line them up close to the fence and offer them lunch. After lunch, the room was reorganized with mattresses on the ground for another sleeping moment, which lasted for about two hours, from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m.

Chart 1 - Summary of the morning routine at Sofia’s daycare center

| Routine | ||

|---|---|---|

| Morning | 07h-08h | Brief nap |

| 08h-10h | Bottle/playtime and diaper change | |

| 10h-10h30 | Lunch | |

| Morning/Afternoon | 11h-13h | Longer nap |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Turning now to Figure 1, the diagram counts Sofia’s sleeping periods during the three first collection dates. It indicates the time that the institution attributed to the routines that came before the infant’s sleep or wake time, and the moment when the focal infant took shorter or more fragmented naps (which we indicate as a nap) or even had longer periods of sleep (which we indicate as sleep).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 1 - Sleep and wake routines proposed by the institution and monitoring of the focal infant sleeping times.

However, in Figure 1, we identified that, regarding the propositions of sleeping routines, in the initial month, Sofia did not fall asleep completely during the first sleeping period in any of the collection days (she only took a brief nap on the first day at the end of the period). During the wake-period routine that followed, when the teachers placed the infants on the floor and offered them toys or organized more structured activities, it was observed that Sofia usually showed signs of sleepiness (yawning, scratching her eyes, tiredness, etc.), and often cried. Such a state also seemed to affect her mood and willingness to play to the point when Sofia’s crying became more intense, she entirely refused the proposed activities and was not willing to interact with adults and other infants during these moments.

When the crying persisted, the teachers picked her up and tried to comfort her, and eventually tried to make her sleep. At this moment, as she’d eventually fall asleep, the teachers placed her in one of the cribs and let her nap for a while, even though most of the group was awake. Hence, on all collection dates of the first month, Sofia took naps “off the schedule” in the morning period. Figure 1 shows that even when they were more intermittent, the naps and sleeping moments “off schedule” lasted for about one hour, resembling the duration proposed earlier by the institution but taking place at a different time than that established by the institution for the sleep and wake cycles.

Usually, after this nap, Sofia was woken up to change diapers or to have lunch. In these moments, she facially displayed a better mood and engaged more with the activities and others. For example, on the first day, after her nap, she looked attentively and smiled at another baby. This process is shown and exemplified in Figure 2.

Source: Authors’ archive.

Figure 2 - Illustration of Sofia’s sleep and wake rhythm in the morning routine on her first day.

Finally, regarding the prolonged sleeping time, it became more established in Sofia’s routine after the second and third collections, when the focal infant was staying full-time. This second sleeping moment gradually shows more coincidence between the rhythm of the focal infant and the institution, as indicated by Figure 1, although Sofia tends to take a little longer to fall asleep in relation to the group, possibly because of the morning nap (as verified in video recordings). Therefore, the sleeping hours were very significant in the transition experience, as we will discuss next.

DISCUSSION

The presented results indicate that the (re)constitution of the infant’s routine at the beginning of attendance, in its transition process, can present significant contrast between the rhythms and proposition of routines, which we exemplify here with sleeping hours. In this case, this contrast is persistent throughout the first month, especially regarding the first sleeping hour proposed by the institution. The contrast signalizes a sort of asynchrony between the timing inherited by the focal infant from the home and the timing inherited by the institution, its structure and relationship with one of its external communities.

About the temporal complexity that is manifested in and through institutional practices, we indicate that the transition process includes several time scales and temporalities. Such dimensions of temporality can constitute themselves in a more linear or circular manner, simultaneously manifesting themselves in sequences of events and daily, weekly, monthly, or even annual cycles, therefore not being reduced to standardized time series regulated by the clock’s chronology (Pacini-Ketchabaw, 2012; Bollig, 2018).

However, it is important to focus on the fact that time is central to estimate the persistence of practices of social life, and that the institutionally proposed rhythms and routines have cultural and even ideological ideals (Rossetti-Ferreira, Amorim and Silva, 2004; Blue, 2019; Herold et al., 2022) that materialize themselves and are negotiated in the here and now of the present time of social relations. Even sleep, understood as a simple organic need, becomes regulated in a collective manner, being surrounded by routines, rhythms, and times that “[…] configure the ethos of the social status.” (Silva and Muller, 2017, p. 87).

In this sense, the case indicates that transition implicates the negotiation of the organic times of the infant in relation to a historical construction of time of the institution (Pairman, 2018; Herold et al., 2022), which, for example, through the structure of sleeping routines, attempts to meet labor-related demands, both external (i.e., industrial hours reflecting on the first sleeping period) and internal to the center (i.e., longer duration of sleep, allowing the teachers to have their lunch hour). In this temporal transaction, the body is “[…] marked and affected by historically constructed practices […]”, and such marks and effects reproduce themselves and affect the related subjects (Smolka, 2004, p. 43). Also, the different rhythms connect with each other, tensioning interests and individual and collective processes in the institutional context (Pairman, 2018; Birkerland, 2019; Blue, 2019). Facing this complexity of elements that constitute this transition dimension, the tensions can be managed with less or more flexibility by the institution.

In this regard, the institutional organization aims to enable the flexibility in the several practices, which is a central element for the transition (Peixoto et al., 2017). In the discussed case, the teachers’ flexibility of allowing and helping Sofia sleep outside the institution’s schedule had a significant repercussion in the process, shown by the clear mood change and engagement after the short naps. It is also important to mention that the physical availability of a place for naps that are off the schedule (i.e., crib) represents how spatial elements of the institution can favor coexisting different rhythms in the group and attend to children’s contrasting times (Pairman, 2018; Blue, 2019).

From the teachers’ point of view, they also needed time and interaction with the infant to learn and recognize her manifestations, thus proposing alternative practices. It is observed that transition can benefit from a broader diversification of practices conducted by several authors and institutions, and that the institution-family partnership is essential so that these discrepancies can be understood based on the respective contexts that constitute specific habits of the infant (Coelho et al., 2015; Peixoto et al., 2017). Therefore, it is also important to maintain the communication between families and teachers when it comes to contrasting rhythms throughout transition, so that the temporal flow of the infant who transits across these contexts can be embraced and treated in a more integrated and shared manner (Grande et al., 2017; Coelho et al., 2018).

Finally, regarding the matter of group routine from the stance of educational practice, it can be configured as a pedagogical tool to structure the routine of the new child (Barbosa, 2010). The recurrence of events related to time and space reference markers can contribute to make the routine more predictable, thus working as an organizing axis of memory, history and social identity of the infant (Barbosa, 2013; Behar, 2015; Dentz et al., on press). However, despite the social ideal of synchronous adjustment by establishing routines, a conception discursively materialized in the findings of this article (Rossetti-Ferreira et al., 2004), we argue for the need of openness to acknowledging contrast, asynchrony, divergent paths, and their meaning for the infant’s process (Amorim et al., 2004; Vuorisalo, Raittila and Rutanen, 2018). Such posture is essential so that the transition does not convert into the subjugation of the subject to collective hours (Barbosa, 2000; Pacini-Ketchabaw, 2012), but instead, that it can be legitimated within its relational trajectory with possible negotiations and practices that are properly (re)thought, (re)assessed, or reinforced based on the thereafter following processes.

REFERENCES

AMORIM, K. S.; ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C. Creches com qualidade para a educação e o desenvolvimento integral da criança pequena. Psicologia: ciência e profissão, v. 19, n. 2, p. 64-69, set. 1999. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-98931999000200009 [ Links ]

AMORIM, K. S.; ELTINK, C.; VITÓRIA, T.; ALMEIDA, L. S.; ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C. Processos de adaptação de bebês à creche. In: ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C.; AMORIM, K. S.; SILVA, A. P. S; CARVALHO, A. M. A. (org.). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2004. p. 137-156. [ Links ]

AMORIM, K.S. Linguagem, comunicação e significação em bebês. 2012. 215 f. Tese (Livre-docência) - Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, 2013. https://doi.org/10.11606/T.59.2019.tde-03052019-103233 [ Links ]

AMORIM, K. S. Interações e processos vinculares do bebê a partir do ingresso na creche, em sete países/culturas: Brasil, Finlândia, Escócia, Austrália, Samoa, Nova Zelândia e EUA. Projeto temático da Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (16/24717-0). Ribeirão Preto, SP: FAPESP, 2016. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, M. C. S. Fragmentos sobre a rotinização da infância. Educação & Realidade, v. 25, n. 1, p. 93-113, 2000. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, M. C. S. As especificidades da ação pedagógica com os bebês. Consulta pública sobre orientações curriculares nacionais da educação infantil. Brasília, DF: MEC/SEB/COEDI, 2010. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=6670-asespecificidadesdaacaopedagogica&category_slug=setembro-2010-pdf&Itemid=30192 . Acesso em: 28 set. 2021. [ Links ]

BARBOSA, M. C. S. Tempo e Cotidiano - tempos para viver a infância. Leitura: teoria & prática, Campinas, v. 31, n. 61, p. 213-222, nov. 2013. https://doi.org/10.34112/2317-0972a2013v31n61p213-222 [ Links ]

BEHAR, M. P. T. Etude des micro-transitions quotidiennes et construction des repères en crèche: des professionnels en recherche. PETITE ENFANCE: SOCIALISATION ET TRANSITIONS, 2015, Villetaneuse, France. Anais [...]. Villetaneuse, France, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://hal-univ-paris13.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01259175/document . Acesso em: 21 set. 2021. [ Links ]

BIRKELAND, Å. Temporal settings in kindergarten: a lens to trace historical and current cultural formation ideals?. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, v. 27, n. 1, p. 53-67, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1556534 [ Links ]

BLUE, S. Institutional rhythms: Combining practice theory and rhythmanalysis to conceptualise processes of institutionalisation. Time & Society, v. 28, n. 3, p. 922-950, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X17702165 [ Links ]

BOLLIG, S. Approaching the complex spatialities of early childhood education and care systems from the position of the child. Journal of Pedagogy/Pedagogický Casopis, v. 9, n. 1, p. 155-176, 2018. https://doi.org/10.2478/jped-2018-0008 [ Links ]

BOSSI, T. J.; BRITES, S. A. N. D.; PICCININI, C. A. Adaptação de Bebês à Creche: Aspectos que Facilitam ou não esse Período. Paidéia, v. 27, n. Suppl 01, p. 448-456, dez. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-432727s1201710 [ Links ]

BOSSI, T. J.; SOARES, E.; LOPES, R. C. S.; PICCININI, C. A. Adaptação à creche e o processo de separação-individuação: reações dos bebês e sentimentos parentais. Psico (Porto Alegre), Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, v. 45, n. 2, p. 250-260, abr.-jun. 2014. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Constituição (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília, DF, 1988. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei n° 9394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Diário Oficial [da República Federativa do Brasil], Brasília, DF, v. 134, n. 248, 23 dez. 1996. Seção I, p. 27834-2784. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Censo da Educação Básica 2019: Notas estatísticas. 2020. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://download.inep.gov.br/publicacoes/institucionais/estatisticas_e_indicadores/notas_estatisticas_censo_da_educacao_basica_2019.pdf . Acesso em: 19 maio 2021. [ Links ]

CAMPOS, M. M.; ROSEMBERG, F. Critérios para um atendimento em creches que respeite os direitos fundamentais das crianças. 6 ed. Brasília: MEC, SEB, 2009. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/dmdocuments/direitosfundamentais.pdf . Acesso em: 21 set. 2021. [ Links ]

CESTARO, P. M.; SANTOS, N. S. O que dizem as pesquisas sobre a formação das(os) docentes da creche. In: ALFERES, M. A. (org.). Qualidade e Políticas Públicas na Educação 7. Ponta Grossa: Atena, 2018. p. 213-225. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.atenaeditora.com.br/catalogo/ebook/qualidade-e-politicas-publicas-na-educacao-7# . Acesso em: 18 fev. 2021. [ Links ]

COELHO, V. L. M.; BARROS, S.; PESSANHA, M.; PEIXOTO, C.; CADIMA, J., PINTO, A. I. Parceria família-creche na transição do bebé para a creche. Análise Psicológica, v. 33, n. 4, p. 373-389, 2015. https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1002 [ Links ]

COELHO, V.; BARROS, S.; BURCHINAL, M. R.; CADIMA, J.; PESSANHA, M.; PINTO, A. I.; PEIXOTO, C.; BRYANT, D. M. Predictors of parent-teacher communication during infant transition to childcare in Portugal. Early Child Development and Care, v. 189, n. 13, p. 1-15, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1439940 [ Links ]

COMOTTI, S.; VARIN, D. Il processo di ricongiungimento dopo la separazione diurna nel contesto dell’asilo nido. Bambini, v. 3, pág. 50-64, 1988. [ Links ]

COSTA, N. M. S. O desenvolvimento da exploração locomotora e o processo de transição do bebê à creche:(pro) posições, negociações e percursos. 2021. 211 f. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, 2021. https://doi.org/10.11606/T.59.2021.tde-21022022-115541 [ Links ]

COSTA, N. M. S.; ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C.; MELLO, A. M. A. Providing outdoor experiences for infants and toddlers: Pedagogical possibilities and challenges from a Brazilian early childhood education centre case study. In: TRONDHEIM, L.; SØRENSEN, H. V.; REKERS, A. Outdoor learning and play: Pedagogical Practices and Children’s Cultural Formation. Suíça: Springer Cham, 2021. p. 43-59. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72595-2_3 [ Links ]

DENTZ, M. V. Interação de pares de bebê em sua transição de casa para a creche. 2022. 305 f. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências) - Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, 2022. https://doi.org/10.11606/T.59.2022.tde-18032022-155642 [ Links ]

DENTZ, M. V.; CASTRO, C. R. C.; NEDER, K.; AMORIM, K. S. Processo de transição com ingresso de bebês na educação infantil: revisão bibliográfica. Psicologia USP, no prelo. [ Links ]

GOBBATO, C.; BARBOSA, M. C. S. A (dupla) invisibilidade dos bebês e das crianças bem pequenas na educação infantil: tão perto, tão longe. Humanidades & Inovação, v. 4, n. 1, p. 21-36, 2017. [ Links ]

GRANDE C. R.; NUNES I. B.; COELHO V.; CADIMA J.; BARROS, S. A experiência do bebé na creche: Perceções de mães e de educadoras no período de transição do contexto familiar para a creche. Análise Psicológica, v. 35, n. 3, p. 247-262, set. 2017. https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1174 [ Links ]

HADDAD, L. An integrated approach to early childhood education and care. In: UNESCO. Early childhood and family policy. Paris, 2002. (Series Number 3). 47 p. [ Links ]

HEROLD, L. K. M.; RUTANEN, N.; AMORIM, K. S.; REVILLA, Y. L.; HARJU, K.; WHITE, E. J. First Transitions and Time. In: WHITE, E. J.; MARWICK, H.; RUTANEN, N.; AMORIM, K. S.; KARAGIANNIDOU, E.; HEROLD, L. K. M. First transitions to early childhood education and care: Culturally responsive approaches to the people, places, environments, and ideologies of earliest care encounters across six countries. Suíça: Springer Nature, 2022. p. 225-254. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08851-3_9 [ Links ]

KERNAN, M. Space and place as a source of belonging and participation in urban environments: considering the role of early childhood education and care settings. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, v. 18, n. 2, p. 199-213, jun. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502931003784420 [ Links ]

KLETTE, T.; KILLÉN, K. Painful transitions: a study of 1-year-old toddlers’ reactions to separation and reunion with their mothers after 1 month in childcare. Early Child Development and Care, v. 189, n. 12, p. 1970-1977, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1424150 [ Links ]

KUHLMANN JR., M. Infância e educação infantil: uma abordagem histórica. 7. ed. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2015. [ Links ]

MARTINS, G. D. F.; BECKER, S. M. S.; LEÃO, L. C. S.; LOPES, R. C. S.; PICCININI, C. A. Fatores associados a não adaptação do bebê na creche: da gestação ao ingresso na instituição. Psicologia: teoria e pesquisa, v. 30, n. 3, p. 241-250, set. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-37722014000300001 [ Links ]

MAUVAIS, P. Socialisation précoce et accueil du très jeune enfant em collectivité. Devenir, v. 15, n. 3, p. 279-288, 2003. https://doi.org/10.3917/dev.033.0279 [ Links ]

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. The effects of infant child care on infant-mother attachment security: Results of the NICHD study of early child care. Child development, v. 68, n. 5, p. 860-879, 1997/2006. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01967.x [ Links ]

ØDEGAARD, E. E.; HEDEGAARD, M. Introduction to Children’s Exploration and Cultural Formation. In: ØDEGAARD, E. E.; HEDEGAARD, M. (ed.). Children’s Exploration and Cultural Formation. Springer, Cham, 2020. p. 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36271-3_1 [ Links ]

PACINI-KETCHABAW, V. Acting with the clock: Clocking practices in early childhood. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, v. 13, n. 2, p. 154-160, 2012. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2012.13.2.154 [ Links ]

PAIRMAN, A. Living in this space: Case studies of children’s lived experiences in four spatially diverse early childhood centres. 2018. 249 f. Tese (Doutorado em Filosofia) - University of Wellington, Wellington, Nova Zelândia, 2018. [ Links ]

PEIXOTO, C.; BARROS, S.; COELHO, V.; CADIMA, J.; PINTO, A. I.; PESSANHA, M. Transição para a creche e bem-estar emocional dos bebês em Portugal. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, v. 21, n. 3, p. 427-436, set-dez. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-35392017021311168 [ Links ]

PEIXOTO, C., COELHO, V., PINTO, A. I., CADIMA, J., BARROS, S., PESSANHA, M. Transição de bebés do contexto familiar para a creche: Práticas e ideias dos profissionais. Sensos-e, v. 1, n. 2, pág. 1-14, 2015. [ Links ]

PICCHIO, M.; MAYER, S. Transitions in ECEC services: the experience of children from migrant families. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, v. 27, n. 2, p. 285-296, fev. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293x.2019.1579552 [ Links ]

RAPOPORT, A.; BOSSI, T. J.; PICCININI, C. A. Adaptação de bebês à creche aos 4-5 meses de idade: as 10 primeiras semanas. Psico, v. 49, n. 1, p. 81-93, abr. 2018. https://doi.org/10.15448/1980-8623.2018.1.25750 [ Links ]

ROSEMBERG, F. A cidadania dos bebês e os direitos de pais e mães trabalhadoras. In: FINCO, D.; GOBBI, M. A.; FARIA, A. L. G. (org.). Creche e feminismo: desafios atuais para uma educação descolonizadora. Campinas: Leitura Crítica, 2015. p. 163-183. [ Links ]

ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C.; AMORIM, K. S.; SILVA, A. P. S. Uma perspectiva teórico-metodológica para análise do desenvolvimento humano e do processo de investigação. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, v. 13, n. 2, p. 281-293, mar. 2000. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722000000200008 [ Links ]

ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C.; AMORIM, K. S.; SILVA, A. P. S. Rede de significações: alguns conceitos básicos. In: ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C.; AMORIM, K. S.; SILVA, A. P. S.; CARVALHO, A. M. A. Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2004. p. 23-34. [ Links ]

ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C.; AMORIM, K. S.; SOARES-SILVA, A. P.; OLIVEIRA, Z. M. R. Desafios metodológicos na perspectiva da rede de significações. Cadernos de Pesquisa, v. 38, n. 133, p. 147-170, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-15742008000100007 [ Links ]

SCORSOLINI-COMIN, F.; AMORIM, K. S. Corporeidade: uma revisão crítica da literatura científica. Psicologia em Revista, v. 14, n. 1, p. 189-214, jun. 2008. [ Links ]

SILVA, A. P. S.; ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C.; CARVALHO, A. M. A. Circunscritores: limites e possibilidades no desenvolvimento. In: ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C.; AMORIM, K. S.; SILVA, A. P. S.; CARVALHO, A. M. A. (org.). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2004. p. 81-93. [ Links ]

SILVA, L. A.; MÜLLER, F. A construção social do tempo no cotidiano de bebês na família e na creche. Revista Brasileira de Sociologia, v. 5, n. 9, p. 87-111, 2017. https://doi.org/10.20336/rbs.192 [ Links ]

SMOLKA, A. L. B. Sobre significação e sentido: uma contribuição à proposta de rede de significações. In: ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C.; AMORIM, K. S.; SILVA, A. P. S; CARVALHO, A. M. A. (org.). Rede de significações e o estudo do desenvolvimento humano. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2004. p. 35-49. [ Links ]

VALSINER, J. Culture and the development of children’s actions: a theory of human development. Great Britain: John Wiley & Sons, 1987. [ Links ]

VERCELLI, L. C. A.; NEGRÃO, T. P. A. Um olhar sobre o período de adaptação de crianças pequenas a um centro de educação infantil e o uso de objetos transicionais. EccoS Revista Científica, n. 50, p. 1-19, 2019. https://doi.org/10.5585/eccos.n50.13320 [ Links ]

VIGOTSKI, L. S. A formação social da mente. 4. ed. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1991. [ Links ]

VIGOTSKI, L.S. Pensamento e linguagem. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1993. [ Links ]

VITÓRIA, T.; ROSSETTI-FERREIRA, M. C. Processos de adaptação na creche. Cadernos de Pesquisa, n. 86, p. 55-64, ago. 1993-jul. 2013. [ Links ]

VUORISALO, M.; RAITTILA, R.; RUTANEN, N. Kindergarten space and autonomy in construction: Explorations during team ethnography in a Finnish kindergarten. Journal of pedagogy, v. 9, n. 1, p. 45-64, jun. 2018. https://doi.org/10.2478/jped-2018-0003 [ Links ]

WEREBE, M. J. G.; NADEL-BRULFERT, J. Henri Wallon. São Paulo: Ática, 1986. [ Links ]

WINTHER-LINDQVIST, D. A. Caring well for children in ECEC from a wholeness approach-The role of moral imagination. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, v. 30, p. 1-10, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100452 [ Links ]

WHITE, E. J.; RUTANEN, N.; MARWICK, H.; AMORIM, K. S.; KARAGIANNIDOU, E.; HEROLD, L. K. M. Expectations and emotions concerning infant transitions to ECEC: international dialogues with parents and teachers. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, v. 28, n. 3, p. 363-374, Apr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1755495 [ Links ]

YIN, R. K. Estudo de caso: planejamento e métodos. Porto Alegre: Bookman, 2005. [ Links ]

Received: October 17, 2021; Accepted: March 07, 2022

text in

text in