Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1413-2478versión On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.27 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub 23-Dic-2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782022270120

ARTICLE

Governing by numbers: Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development’s policy for basic education

IUniversidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil.

This paper proposes to analyze the assumptions of the Learning Compass 2030 project of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, aimed at education, with a view to create an international school curriculum through the definition of competencies, knowledge, skills, common attitudes, and values. By using the compass metaphor as a methodological and ideological inspiration, it spreads the idea of curriculum flexibility, lifelong learning, learn to learn and autonomy, and anticipates the needs of students in their future life and work options. We argue that terms, vocabulary, conceptions, written language, and purposes inscribed in the Common National Curriculum Base - High School are aligned to corporate and mercantile interests, and also systematize a pragmatic, instrumental and functionalist character for Basic Education.

KEYWORDS basic education; BNCC-OECD; pedagogy of competences

O artigo analisa os pressupostos teóricos do projeto Learning Compass 2030, da Organização para a Cooperação e Desenvolvimento Econômico, direcionados à educação, com vistas à criação de um currículo escolar internacional por meio da definição de competências, conhecimentos, habilidades, atitudes e valores comuns. Ao utilizar a metáfora da bússola como inspiração metodológica e ideológica, difunde-se a flexibilidade curricular, a aprendizagem ao longo da vida, a proposta de aprender a aprender e a autonomia, e antecipam-se as necessidades futuras e opções de trabalho dos estudantes. Defende-se ainda que termos, vocábulos, concepções, linguagem escrita e finalidades inscritos na Base Nacional Comum Curricular - Ensino Médio estão alinhados com proposições, concepções e interesses corporativos e mercantis, além de sistematizar um universo pragmático, instrumental, funcionalista e competitivo para a educação básica brasileira.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE educação básica; BNCC-OCDE; pedagogias das competências

El artículo tiene como objetivo analizar las premisas del proyecto Learning Compass 2030, de la Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos orientado a la educación con miras a crear un currículo escolar internacional a través de la definición de competencias, conocimientos, competencias comunes, actitudes y valores. Al utilizar la metáfora de la brújula como inspiración metodológica e ideológica, difunde la flexibilidad curricular, el aprendizaje permanente, el aprender a aprender, la autonomía y anticipa las necesidades futuras y las opciones laborales de los estudiantes. Señalamos que términos, palabras, conceptos, lenguaje escrito y propósitos de la Base Curricular Nacional Común - Bachillerato están alineados con las proposiciones, convicciones e intereses corporativos y de mercado, además de sistematizar un universo pragmático, instrumental, funcionalista y competitivo para la Educación Básica.

PALABRAS CLAVE educación básica; BNCC-OCDE; pedagogías de competencias

INTRODUCTION

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) was created in 1961 to arbitrate and coordinate, through the Marshall Plan, the reconstruction of countries devastated by World War II (1939−1945), to ensure production growth, build regulatory frameworks for the training of personnel in the scientific and technological areas and create mechanisms to overcome barriers and free up trade between countries. In these relations, Americans and Europeans operate through the determination of instruments of economic stabilization and regulation of financial transactions, industry, commerce, agriculture, infrastructure, transport, technologies, environment and education sectors, instigating competition between member countries.

Based in Paris and under the leadership of the United States, the OECD, in the decades following its creation, became an institution with international economic, legal and political power, acting as a policymaker to increase stability and consolidate a liberal economic model focused on the growth of the economy of developed countries and on the regulation of public policies, in particular, educational ones.

To operate, the OECD has an organizational structure composed of centers, agencies, offices, departments, committees, forums, working groups, technicians and specialists. In 1970, it created the Board of Education. In 2012, the Directorate for Education and Skills was created, with an expert staff, aiming to make public education a service to be exploited by the private market and achieving the status of a database, with the power to prescribe the global policy for the education of member countries and key partners.

Acting in economics, science, commerce, financial markets and industrial policy through data surveys, statistical reports, peer reviews, publications and programs, the OECD soon saw public education as another strategic niche to be explored by mercantile and financial capital. In this process of action, the documents Preliminary reflections and research on knowledge, skills, attitudes and values necessary for 2030 (OECD, 2016), The future of education and skills - Education 2030 (OECD, 2018a), and Future of Education and skills 2030: conceptual learning framework (OECD, 2018b) anticipate future competences and defend a curriculum standardization on a global scale, with knowledge, skills, attitudes and values to be developed by students, under the motto of well-being. In turn, Learning Compass 2030 (OCDE, 2019a) document presents an ambitious vision for the future of education, highlights an evolving learning framework and provides guidance points for individual well-being. Thus, it uses the metaphor of the learning compass to emphasize the need for students to learn to navigate by themselves in unknown, adverse, uncertain contexts, as well as during constant crises.

With this reasoning, in theoretical terms, it is understood that the economic base determines and produces political decisions and the legal system, and that the set of private apparatuses of hegemony are conductors of worldviews that spread in the form of agreements, protocols of intentions, loan agreements, publications, statistical reports and education programs. These business people, financiers and organizations lead and organize a Structured Global Education Agenda (Dale, 2004), using international programs, conventions and statistical reports to imprint a conception of education in the service of international competitive economic interests.

It starts, then, from the theoretical premise that documentary sources and legislation represent the historical movement and not the whole. It constitutes what is real and brings expressions of dissent, domination and asymmetries. Thus, the question is: what interests underlie the OECD’s intervention in school curricula in the Brazilian educational context? How are the alignments between the guidelines inscribed in the National Common Curricular Base) - High School and OECD propositions between 2012 and 2021? How did the pedagogy of competencies and skills become the ordering paradigm of legislation, concepts and curriculum practices in basic education?

Thus, the first section of this article discusses how the logic of numbers directs and promotes the propositions made with regard to education by the OECD; the second section analyzes the ideas of an international curriculum, theoretical and marketing foundations that govern such perspective; and the third reveals, through historical mediations, the conceptual and theoretical alignments in public basic education in the state of Goiás.

GOVERNING BY NUMBERS AND INTERNATIONAL STATISTICAL INDICATORS

The OECD is an international regulatory organization made up of 36 member countries, with key partners Brazil, China, India, Russia, South Africa and Indonesia, and is focused on regulating economic growth, arbitrating tariffs and barriers, promoting policies aimed at global financial stability, strengthening the free market and furthering technological advances between markets. Since the 1990s, it has led a neoliberal economic program and advocated the free movement of capital, opened up national economies, deregulating them, promoted state reform and structural adjustments that altered the relationship between the state and civil society, adopted fiscal balance, encouraged privatizations, urged the adoption of public-private partnerships, and finally promoted the adoption of instruments of national regulation. Since the Seattle meeting in 2002, tensions have increased at international summits of organizations in which corporations, rentiers and financiers defend private commercial services and public services - education and health - that can be offered by the for-profit private sector.

In this context, they trigger actions, conventions and agreements in which OECD experts proposed a modus operandi, either through policy convergences or policy transfer (Ball, 2001), or through the government of numbers, statistical reports, indicators and inventories (Popkewitz and Lindblad, 2016). This means that data from the education systems of the country of origin are translated into reports and publications by the Center for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) and by the Directorate for Education and Skills, generating indicators and metrics with a view to improving the educational quality of member countries and partners.

Economic and political contingencies and advances in information and communication technology have moved merchants and rentiers to organically include public education as a business niche. Studies by Pereira (2016), Popkewitz and Lindblad (2016), Freitas and Coelho (2019), and Hypólito and Jorge (2020) point out that the OECD acts in the superstructure through strategies and ideologies that are transported in agreements, programs, evaluations by peer reviews, statistical reports, Education at a Glance, the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), and publications contributing to rank member and partner countries on the international circuit.

This logic of numbers, translated into statistical indicators, ranks, categorizes, classifies and separates countries, institutions, regions, schools and people, in addition to pointing out other market niches. Such logic conceives the child, the people, as reduced to statistical data and subject to the mechanisms of social control (Popkewitz and Lindblad, 2016). However, numbers help in organizing and understanding social dynamics and typify people, groups and institutions. Numbers serve to exclude and include, and they are useful for ruling and dominating. Acting by the logic of numbers and international reports indicates forms of domination, intervention and political-ideological control of the dominant over people, groups and institutions. Numbers carry ideologies, visions, values and power. Deprived of historical context, numbers can cover or uncover and legitimize decisions and programs aimed at economic, technological and social interests. Numbers and statistical reports indicate to neoliberal governments and financial organizations the possibilities for growth, whether in private commercial services or in state public services. They are crooked and they are profitable. Numbers hide and reveal, as they circulate views of the superiority of the private market in the administration of public institutions and, at the same time, show and confirm inequalities, exclusions and hierarchies.

The government’s logic by numbers that are manufactured by data and information extracted from the countries’ education programs supports an ideological and operational structure capable of interconnecting economic policy interests and educational policy. This neoliberal logic emphasizes that low economic growth results from the low quality of education, verified and measured by the Program for Indicators of Education Systems (INES); PISA; the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIACC); and Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS).

Chart 1 shows, chronologically, OECD publications and educational programs developed between 1960 and 2020.

Brazil’s relationship with the OECD, as an associated country and as a key partner, implies providing education statistics and figures; adhering to rules, regulations and conventions; paying the financial costs; making adjustments to the economy; participating in committees and implementing programs related to education, as shown below.

Chart 1 - OECD publications and educational programs: 1960−2020.

|

|

European Productivity Agency | 1953 |

| Office for technical-administrative personnel (OSTP) | 1958 | |

|

|

Mediterranean Regional Project (MRP) | 1961 |

| Educational statistics program and quantitative analysis techniques | 1961 | |

| Scholarship program | 1962 | |

| Center for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI) | 1967 | |

| Department of Education | 1970 | |

| Program focus on school and on the teaching and learning process and on development and research policies | 1970 | |

| Analysis and teacher training program | 1970 | |

| Program for Institutional Management in Higher Education (IMHE) | 1971 | |

| School building construction program (PEB) | 1972 | |

| International Training Program for Education Management | 1973 | |

|

|

Program for Indicators of Educational Systems (INES) | 1983 |

| Education at a Glance - Panorama of Education | 1992 | |

| Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) | 1997 | |

| Policy Advisory and Implementation Program (PAI) | 1998 | |

|

|

Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) | 2008 |

| Program for Assessment of Higher Education Learning Outcomes (AHELO) | 2010 |

Source: Adapted from Papadopoulos (1994) and Pereira (2016).

The cooperation between Brazil and the OECD dates back to the early 1990s, when the OECD began working with four Latin-American countries (also including Argentina, Chile and Mexico). Brazil joined its first OECD Committee, the Steel Committee, in 1996 and became a member of the Development Center in 1997. Since then, cooperation has grown steadily, and Brazil is now the key partner most engaged in the Organization (OECD, 2018c, p. 6).

However, since 2000, Brazil has participated in the PISA, with the objective of assessing the acquisition of a certain amount of content, measured by international indicators. The organization, dissemination and maintenance of the educational information and statistics system, the payment of financial costs, the elaboration of questions, as well as the entire application of the evaluation program in the country is carried out by the National Institute of Educational Studies and Research Anísio Teixeira (INEP). This position of Brazil leads to political alignments, as the OECD’s educational prescriptions and programs are accepted and translated into speeches and actions, legislation, plans, programs and projects in educational management with the consent of the federal government and conducted by private groups in the service of corporate and mercantile interests, including All for Education, Group of Institutes, Foundations and Companies (GIFE) and the All for the Base Movement.

THE LEARNING COMPASS AND THE IDEALS OF A COMMON INTERNATIONAL CURRICULUM

Discussions about a project in a global perspective for education advanced when the OECD (2005) created the Project Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo) with the intention of creating a solid conceptual framework, outlining objectives for countries to promote education throughout life. This context includes the report of the International Commission on Education for the 21st century of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization - Unesco (1993-1996), chaired by economist Jacques Delors. He spread the adage learning throughout life, and the pillars of education learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together and learning to be accepted and taken as mainstays of education policies in Brazilian states and municipalities (Delors et al., 1996).

In 2015, the perspective of comparability between countries led the OECD to lead the Education Project 2030, in a movement with representatives from different countries, institutions, entrepreneurs, experts and leaders, with the objective of deepening the fundamental future competences expected of the student, in an attempt to foster technological and economic growth. To this end, the OECD Directorate for Education and Skills, in the documents Learning Compass 2030 (OCDE, 2019a) and The Future of Education and Skills (OECD, 2018a), proposed the creation of a conceptual framework for learning and the creation of an international curriculum for comparability between countries, educational institutions and people. The structuring of the supranational reference matrix took place in two phases. In the first, it brought together expert staff and governments, leaders, entrepreneurs, managers and directors for the conceptual redesign of the international curriculum; in the second, in 2019, it consolidated the concept of competencies and skills with a common supranational curriculum proposal, to be implemented in different countries.

Then, the document Future of Education and Skills 2030 Conceptual learning framework - Concept Note (OECD, 2019b) prescribed the skills of the future: cognitive and metacognitive skills; social and emotional skills; and physical and practical skills. Furthermore, three key points are highlighted:

1. technologies have shifted workers from routine tasks to others that require metacognitive, emotional and creativity skills;

2. to maintain themselves, workers will need new skills, flexibility, curiosity, a positive attitude towards lifelong learning; and

3. social and emotional skills are equally essential to becoming a responsible citizen. In another document, Future of Education and Skills 2030 Project (OECD, 2018b, p. 2-3), the organisation asks:

- What competencies (skills, knowledge, values and attitudes) do today’s students need to shape the future for themselves and social and environmental well-being?

- How to design learning environments capable of promoting these competencies? That is, how to design and implement a future-oriented curriculum?

- What will schooling be like in the future?

In the position of international leadership, the political and operational capacity to govern by numbers has become an effective means of domination by the OECD. In this movement, it acts to regulate the economy, the financial sector and public policies, and presses for an association of the public school with the productive sector, similarly to companies. The organization questions, in the document Learning Compass 2030 (OCDE, 2019a, p. 1):

- What kinds of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values are needed to understand, engage and shape a changing world towards a better future in 2030?

- How can policies and practices be effectively transformed to support youth learning and well-being in the context of changing societies, as well as economies?

Note that the compass metaphor carries political and ideological underpinnings. In a subtle way, the OECD reaffirms neoliberal precepts such as free trade, competitiveness, flexibility, privatization and partnerships in the service of the capitalist order. By defining the learning compass, it established a cartography of education in the world, ensuring the prerogative of a global leadership in the direction of the future of education, in parallel with the World Bank and corporations related to the business field. Who is interested in the anticipation of Basic Education? Who in interested in the pedagogies of learning to learn? Alerts sound in the writings of Freitas and Coelho (2019) and Arelaro (2020), demanding that we resume actions and projects aimed at human and integral formation.

These foundations are in the political-educational agreements between countries and corporations that govern globalized capitalism. They are about carrying out private commercial services and invading public services as if they were private. Education has been directed according to the prerogatives and corporate interests of capitalism, from a pragmatic, instrumental perspective, aligned with the emerging needs of the world of work and the new social order. The purpose of creating a supranational curriculum takes up the global ideology of education linked to corporate interests, especially in the document Learning Compass 2030 (OCDE, 2019a), which sets out the competencies, skills, attitudes and values that are required of the individual to live in a capitalist society.

How can we equip them to thrive in an interconnected world where they need to understand and appreciate different perspectives and worldviews, interact respectfully with others, and take responsible action for sustainability and collective well-being? (OCDE, 2019a, p. 2).

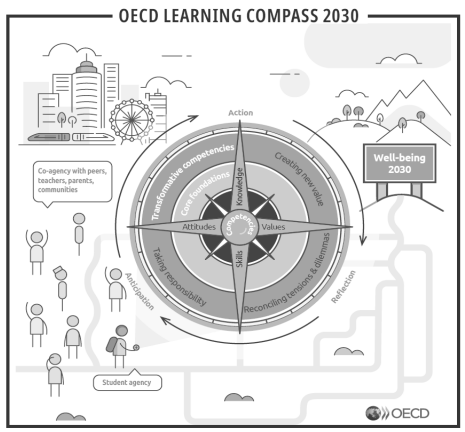

With these directions, the OECD defined the steps for the consolidation of its expansionist and planetary project, since “[…] the compass traces the bases of a common international curriculum, applicable to all types and levels of education and dynamic.” (RBE, 2020, s.p.). The learning compass has competencies as its core, outlined on the basis on the principle of circularity, which involves the reciprocal and uninterrupted interaction between action, reflection and application, enabling the dissemination of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values as guiding axes of school curricula (OCDE, 2019a), as can be seen in Figure 1.

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development - OCDE (2019a).

Figure 1 - The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Learning Compass 2030.

At the core of the compass rose is the individual; around it are the competencies; and, at the ends, knowledge, skills, attitudes and values, with then another two circles. In the first are core foundations and in the second, between the points of the compass, are: transformative competencies, taking responsibility, reconciling tensions and dilemmas, and creating new value, which expand to the other circle with sectioned arrows, indicating a circular movement for action, reflection, anticipation. In the corners of the compass, the actors were placed: peers, teachers, parents, communities and student-co-agency, chosen by the OECD as responsible for the well-being of each one and the entire planet.

The Learning Compass 2030 (OCDE, 2019a) defines the three transformative competencies expected of students to shape a better future: taking responsibility, creating new values, and reconciling tensions and dilemmas. In the representation of the compass, fundamental conditions and basic knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that constitute the elements of the instrumentalization of learning for the curriculum of any country are defined. There is an emphasis on agency and co-agency, which means having the ability, motivation, will and values to positively influence your life and the world around you.

THE THEORETICAL PRINCIPLES COVERED IN THE OECD CURRICULUM PROPOSAL

By proposing an international school curriculum, the OECD expands an ideology based on market assumptions, conditioning the education programs and policies of the adept countries. It believes that an international curriculum can result in improved academic performance, boosting learning to learn with a rhetoric of a responsible and proactive citizenship in the face of everyday uncertainties, and zeal for well-being. This view is found in the document Curriculum (re)design: a series of thematic reports from the OECD Education project 2030, and states that “[…] an evidence-based curriculum design is probably the best possibility to equip students with the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values they need to shape their future and thrive.” (OCDE, 2019a, p. 2).

In this way, the Organization assumes that a curriculum in itself has the power to equip students. Note that historical determinants are suppressed, structural issues are hidden, migrations are erased, and the student is remembered as a number tied to corporate interests. With linear, sterile and mechanical reasoning, governments are offered a perfect formula for equipping students. We know that different principles and foundations order and structure a school curriculum. However, how to explain so much interest in the public basic education curriculum? And what are the theoretical principles covered in the OECD’s propositions?

Experts are aware of the rejections of the proposition of an international curriculum and point out three designs: official written curriculum, defined by government agencies, which discloses what students should learn; implemented curriculum, which refers to the interpretations and experiences of teachers who organize teaching; and achieved curriculum, which concerns the learnings that students are able to demonstrate (OCDE, 2019a). It is important to note here the old strategy of domination: some think and others do. Furthermore, they operate with a conception of curriculum detached from history, decontextualized from the structural conditions, processes and interrelationships and connections that permeate educational policies and pedagogical work in public schools. In this way, the pedagogies of learning to learn stipulate that the learning that the individual does for himself and that develops social and emotional competencies is more desirable.

It is observed that the focus is the student-agency, and there is no disagreement that school education should really develop, in the subject, intellectual autonomy and freedom of thought, but there is criticism because the pedagogies of learning to learn establish a hierarchy of values, in which learning alone is situated at a higher level than learning from exchanges, from the transmission of knowledge through social relationships. By doing this, they highlights the instrumental, autonomist, efficient and individualist perspective of education, in which, according to Saviani (2013, p. 439-440), “[…] neotechnicism is present, feeding the search for total quality in education and the penetration of corporate pedagogy, consummating the process of adopting the business model in the organization and in the functioning of schools.” (Duarte, 2001).

The second principle refers to the theory of human capital (Schultz, 1973), translated into the idea of competencies and abilities anchored in the need to train individuals to be capable of surviving the permanent changes in society and, at the same time, being able to accept the hierarchical and domination structures. In other words, if the context requires productive, effective, efficient and competent agents, education is assigned the function of producing them, according to the needs of the market. As a result, as Schultz (1973, p. 33) claims, human beings are recognized on the basis of their productive potential, since “[…] by investing in themselves, people can expand the range of choice of position at disposition. This is one of the ways free men can increase their well-being.”. Competencies and skills are two pillars of support for the OECD policy for Basic Education in countries, whose foundations are in the supposed knowledge society and in the superiority of the market for the distribution of educational policies. They affirm that

[…] education must prepare individuals to accompany society in an accelerated process of change. That is, while traditional education would result from static societies, in which the transmission of knowledge and traditions produced by past generations was sufficient to ensure the formation of new generations, the new education must be guided by the fact that we live in a dynamic society. The individual who does not learn to update himself will be condemned to eternal anachronism, to the eternal lag of his knowledge. (Duarte, 2001, p. 37)

Under the logic of knowledge society, competencies have become the shapers of individuals, in accordance with the needs of the emerging world and with the interests of the productive machine. According to Jimenez (2003, p. 4), this translates into stating that, according to this conception,

[…] the new worker must, above all, know how to be versatile in dealing with new work instruments, agile and flexible in reasoning and decision-making, in addition to being harmonious, cooperative and emotionally balanced.

With this reasoning, the third principle refers to the logic of numbers and statistical reports, pointed out by Popkewitz and Lindblad (2016), which serve as instruments for comparing and regulating the education policy of countries. Thus, they unleash forms of domination through intervention in the curricular designs and programs in which the country participates. Note that home country school data, obtained from running programs, are transformed into numbers that later serve to justify the need for a worldwide curriculum and the standardization of international tests and examinations. Accordingly, control policies are legitimized, with a view to the formation of productive citizens aligned with the new social and legal systems.

The fourth principle is linked to the perspective of the anticipated future, through the control of global knowledge. The discourse of the anticipated future is a strategy of persuasion, guided by the ideology of the sense of urgency, which brings, virtually, to the present a non-existent future. It celebrates a desired future and takes institutions and students as entities to be equipped by a formula towards an idealized future. This perspective of an anticipated future, described in the studies by Freitas and Coelho (2019), helps to explain a pair of domination, whether by the attachment and disorganization of lived life, or by the tendency of knowledge economy to transform countries into networks of interaction-exclusion. Thus, the pace of growth occurs through competition, competitiveness and flexibility in a single spectrum: “[…] the race to a new technological colonialism through knowledge and the discourse of the anticipated future.” (Freitas and Coelho, 2019, p. 3).

The transformative competencies of Learning Compass 2030 (OCDE, 2019a) are intended to structure the content, shape skills and spread values and attitudes that guide international curricula in mechanical, artificial and decontextualized learning, as prescribed in Chart 2.

Chart 2 - Guiding elements of the international school curriculum.

| Transformative competencies: Students need to be empowered and feel they can help shape a world where well-being and sustainability - for themselves, others and the planet - are achievable. All students need this solid foundation to fulfill their potential to become responsible contributors and healthy members of society. |

| Student agency/co-agency: The belief that students have the will and ability to positively influence their own lives and the world around them, as well as to set a goal, to reflect and act responsibly to effect change. Students develop co-agency in an interactive, self-effective, supportive and enriching interaction with peers, teachers, parents and communities, organically and in a larger learning ecosystem. |

| Knowledge: Includes concepts and ideas as well as practical understanding based on experience of having performed certain tasks. It recognizes four different types of knowledge: disciplinary, interdisciplinary, epistemic and procedural. |

| Skills: Corresponds to the ability to use one’s knowledge for a purpose. Skills are the ability and capacity to carry out processes, and to be able to use one’s knowledge responsibly to achieve a goal. It states three different types of competencies: cognitive and metacognitive; social and emotional; and practice and physics. |

| Attitudes and values: These refer to the principles and beliefs that influence a person’s choices, judgments, behaviors and actions on the way to individual, social and environmental well-being. Strengthening and renewing trust in institutions and among communities requires greater efforts to develop the core shared values of citizenship, to build more inclusive, fair and sustainable economies and societies. |

| Anticipation-action-reflection cycle: This is the interactive learning process through which students continually improve their thinking and act intentionally and responsibly. In the anticipation phase, students are informed by considering how actions taken today may have consequences for the future. In the action phase, students have the will and ability to act in favor of well-being. In the reflection phase, students improve their thinking, which leads to better actions for individual, social and environmental well-being. |

Source: Adapted from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development - OCDE (2019a, p. 17).

The OECD’s political and ideological views underlie the publications, agreements, statistical reports and programs such as PIACC, PISA and TALIS, and the large-scale evaluations in which countries participate. Numbers not only circulate, they also carry ideologies, visions, values, predictions, beliefs and doctrines. Thus, it is important to list the OECD’s positions, as it:

defends trade in private services and public services as a niche for the expansion of the private business sector;

advocates that the public school can be recognized as a company governed by market laws;

believes in the superiority of the free market for the provision of public Basic Education; and

stands for the slogan of lifelong learning, demanding that governments break with a static and obsolete curriculum and submit to an international school curriculum that then serves as the basis for rankings and comparisons between countries.

When OECD publications are analyzed, alignments of similar terms, concepts, ideas and conceptions in the BNCC can be observed. Examples of this alignment are in the competencies and skills enshrined in the BNCC (Brasil, 2017; 2018) and in Law 13,415/2017, which provides for High School Reform and amends the Law of Directives and Bases of National Education (LDB) No. 9394/ 1996 (articles 32 and 35 - Brasil, 1996). Both regulations establish intentions and purposes for Basic Education and guide curriculum reformulations in states and municipalities.

As an example, we saw that the Curriculum Document for the State of Goiás (DC-GO)1 aims to “[…] bring the current curricular legislation in our country closer to the reality of Goiás.” (SEDUC/GO, 2018). The alignments occur in curricular documents, political-pedagogical projects and life projects, connected to the DC-GO, which, in turn, aligns with the BNCC of Goiás.

It should be noted that the Municipal Education Network of Aparecida de Goiânia, in the state of Goiás, determined through Notice No. 004/2020, of March 10, 2020, the alignment of the Political-Pedagogical Project of school units to DC-GO and BNCC.2 This orientation is mandatory, by filling in the competencies and skills to be achieved in each of the planned contents, called objects of knowledge (our emphasis).

Through Resolution No. 2, of December 22, 2017, the Ministry of Education instituted and guided the implementation of the BNCC - Basic Education. In 2018, the BNCC - High School was approved. Of a normative nature, it defined the set of essential learning that all students must develop throughout the stages and modalities of Basic Education. The perspective of a unified curriculum for the whole of Brazil was adopted, with 60% of the contents defined by the base and the remaining 40% determined by the state and municipal schools for regional particularities. It so happens that, in practice, emphasis is given to working with content defined on a national basis (60%), to the detriment of regional and cultural content, since the former will be charged in external assessments to assess the quality of education.

Chart 3 shows the descriptors presented in the BNCC - High School (Brasil, 2018), which align with the perspectives indicated by the OECD.

Chart 3 - National Common Curricular Base descriptors and alignments with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s concepts and ideas.

| Knowledge: Valuing and using knowledge historically built on the physical, social, cultural and digital world to understand and explain reality, continue learning and collaborate to build a fair, democratic and inclusive society. |

| Scientific, critical and creative thinking: Exercising intellectual curiosity and using the approach of science, including research, reflection, critical analysis, imagination and creativity, to investigate causes, develop and test hypotheses, formulate and solve problems and to create solutions (including technological ones) based on the knowledge of the different areas. |

| Communication: Using different languages: verbal (oral or visual-motor, such as Brazilian Sign Language - Libras), written, body, visual, sound and digital, as well as knowledge of artistic, mathematical and scientific languages to express oneself and share information, experiences, ideas and feelings in different contexts, in addition to producing meanings that lead to mutual understanding. |

| Cultural repertoire: Valuing and enjoying the various artistic and cultural manifestations, from local to global, and participating in diversified practices of artistic and cultural production. |

| Digital culture: Understanding how to use and create digital information and communication technologies in a critical, meaningful, reflective and ethical way in the various social practices (including school ones) to communicate, access and disseminate information, produce knowledge, solve problems and exercise protagonism and authorship in personal and collective life. |

| Work and life project: Valuing the diversity of knowledge and cultural experiences, appropriating knowledge and experiences that allow one to understand the relations of the world of work and make choices aligned with the exercise of citizenship and with one’s life project, with freedom, autonomy, critical awareness and responsibility. |

| Self-knowledge and self-care: Knowing and appreciating oneself and taking care of one’s physical and emotional health, understanding oneself in human diversity and recognizing one’s own emotions and those of others, with self-criticism and the ability to deal with them. |

| Empathy and cooperation: Exercising empathy, dialogue, conflict resolution and cooperation, ensuring respect for and promoting respect for others and human rights, welcoming and valuing the diversity of individuals and social groups, their knowledge, their identities, their cultures and their potential, without prejudice of any kind. Arguing based on facts, data and reliable information to formulate, negotiate and defend ideas, points of view and common decisions that respect and promote human rights, socio-environmental awareness and responsible consumption at the local, regional and global levels, with an ethical positioning in relation to caring for oneself, others and the planet. |

| Responsibility and citizenship: Acting personally and collectively with autonomy, responsibility, flexibility, resilience and determination, making decisions based on ethical, democratic, inclusive, sustainable and solidary principles. |

Source: Adapted from Brasil (2018, p. 9).

When analyzing the OECD and BNCC’s concepts of competencies in the publications, conceptual alignments can be seen between them, as they are centered on the individual and on the mobilization of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values to solve everyday demands. These are skills that are based on practices related to the individual, with an emphasis on interpersonal and socio-emotional aspects, also on productive capacity, in the use of technologies, rudimentary knowledge and instrumental know-how, to make young people more responsible, productive and consuming (Libâneo, 2016; 2020).

Transformative competencies give rise to knowledge, attitudes and values that are instrumental elements for an international school curriculum. Prescribed and practiced in this way, young people are expected to assume responsibilities, evaluate their own actions and ethical goals, be active and proactive agents, develop socio-emotional, metacognitive, practical and physical skills, have the ability and knowledge to solve complex issues, know how to set goals and act responsibly in a context of change.

Like the Learning Compass 2030, the BNCC - High School is fundamentally structured around competencies and skills, with a view to ensuring that students develop their potential in the cognitive, personal and relational spheres, as tools to leverage learning and development. It defines competence as the “[…] mobilization of knowledge (concepts and procedures) and skills (practical, cognitive and socio-emotional), such as attitudes and values to solve complex demands of everyday life, the full exercise of citizenship and the world of work.” (Brasil, 2018, p. 8). When analyzing the documents, it is clear that the OECD conceives the public school as similar to an agency, a company that uses curriculum and equips students. In both documents, a concealment of the public school can be perceived, the classroom is not mentioned as a locus of school formation, nor is the political-pedagogical project. There is no reference to the school as a place for the integral formation of students, but a view is advanced that learning takes place in practice, in companies, at work. Public school as the main place of human and integral formation is hidden and despised; and the teacher is seen as a forwarder of content via curricula, which will then be assessed in large-scale examinations and tests. The student is not looked at; only the numbers are.

The OECD proposals reveal a concealment of the social function of the public school aimed at the integral formation of the subject, as a set of general minimum contents is elected that is considered necessary for work and employment, with a strong appeal to social and social inclusion and life lessons. There is a bet on the mechanization of learning and training for the resolution of standardized and large-scale tests and assessments. The school is placed in the position of disseminating pragmatic, utilitarian and instrumental knowledge to train a worker for an uncertain and tortuous job market.

OECD experts emphasize and proclaim that there is no difference between a private company and a public school. If companies manufacture and sell products, the school equips students, and they consume knowledge. Now, if the public school has become similar to a private company, it can then commercialize the curricula, enrollments, equipment, platforms, technologies, handouts, stock exchange, and fractionate the hiring of teachers, that is, assign a space of expansion of the private business sector. Thus, the social function of the public school has been replaced by the economic function, which entangles other economic organizations that work with particular principles - efficiency, quality and competitiveness - typical of the business world. Taking this public space means controlling dysfunctional, non-standard groups that live at the expense of the capitalist state and are prone to disorder.3

However, in another direction, social segments and scientific associations affirm that the public school is a social institution, a public space, in the sense of public patrimony, space of freedom and democratic principles. These spaces make us equal in rights, focused on collective, plural values and the common good. Time at school means time for freedom, for the elevation of cognitive abilities, for understanding the world around the student.

However, Kuenzer (2017), Motta and Frigotto (2017), Arelaro (2020), and Silva and Silva (2020) indicate that this tension between the needs of production, circulation and accumulation of capital and the training provided by Basic Education occurs due to the folly of wanting to associate school time with productive company time. Tensions intensify because history shows us that the public school is not associated with the time of factory production. In difficult times, the public school needs to be legitimized and recognized as a place for the exercise of freedom and democracy (Saviani, 2013).

Therefore, the following is necessary: to recompose the social function of the public school; to provide everyone with an education of social quality; to democratize access to knowledge; to expand the conditions of permanence and transmission of scientific, artistic, aesthetic and ethical knowledge; to advance in the elaboration of critical thinking; and to socialize historically prepared knowledge. Finally, it is necessary to create possibilities for overcoming the forms of cultural and ideological domination by a new collective and plural consciousness, capable of opening paths for human emancipation.

LESSONS AND REFLECTIONS

The OECD, the World Bank and other financial institutions bring together multiple interests in the production, circulation and accumulation of capital and govern by numbers. In this attempt, exploiting public Basic Education for business purposes remains on the horizon of merchants, financiers and capitalists. To put an end to the political and economic foundations, these organizations reaffirm for public education the competencies, knowledge, skills, attitudes and values to be incorporated into the school curricula of member and partner countries.

BNCC alignments are in the descriptors, vocabularies and words, in the hidden sense of the terms, in the competencies and abilities and mainly in the purposes of the education emanating from the organization. In fact, the pedagogy of competencies and skills, interpersonal and socio-emotional skills, projects, life lessons and measurement of results via large-scale tests and examinations are in line with OECD purposes.

The pedagogy of competences and abilities assumed centrality in the direction of school curricula, coexisting with the perspective of integral and human education, aimed at valuing the subjects of the school and their ability to decide. Therefore, it recognizes that the curriculum goes beyond external prescriptions and attempts at global standardization, as it disregards historical, economic and cultural particularities, as well as those of access and permanence of students in school (Saviani and Duarte, 2015) and the right to education (Cury, 2008; Silva and Silva, 2020). The curriculum integrates and is part of the training, it concerns the purposes of the school, the ethical, aesthetic, cultural values and democratic principles that the school community believes in and embraces. Under rough seas, storms, dark winds and such unequal boats, the compass has to be with students, teachers and principals - subjects of the pedagogical relationship of teaching and learning in public schools.

Therefore, the public school is reaffirmed as the place for the integral and human formation of students, freedom of expression and ethical, critical and collective thinking, with a view to the cognitive elevation and emancipation of human and social subjects.

REFERENCES

ARELARO, L. R. G. Escritos sobre políticas públicas em educação. São Paulo: FEUSP, 2020. https://doi.org/10.11606/9786587047027 [ Links ]

BALL, S. J. Diretrizes políticas globais e relações políticas locais em Educação. Currículo sem Fronteiras, v.1, n. 2, p. 99-116, jul.-dez. 2001. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Lei nº 9394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília: Casa Civil, 1996. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9394.htm . Acesso em: 25 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Lei nº 13.415/2017, de 16 de fevereiro de 2017. Altera as Leis n º 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, e 11.494, de 20 de junho 2007, que regulamenta o Fundo de Manutenção e Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica e de Valorização dos Profissionais da Educação, a Consolidação das Leis do Trabalho - CLT, aprovada pelo Decreto-Lei nº 5.452, de 1º de maio de 1943, e o Decreto-Lei nº 236, de 28 de fevereiro de 1967; revoga a Lei nº 11.161, de 5 de agosto de 2005; e institui a Política de Fomento à Implementação de Escolas de Ensino Médio em Tempo Integral. Brasília: Secretaria-Geral, 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2017/lei/l13415.htm . Acesso em: 08 fev. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum Curricular. [s.d.]. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/ . Acesso em: 24 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Base Nacional Comum Curricular - Ensino Médio. Brasília: MEC, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/historico/BNCC_EnsinoMedio_embaixa_site_110518.pdf . Acesso em: 24 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

CURY, C. R. J. A educação básica como direito. Cadernos de Pesquisa, v. 38, n. 134, p. 293-303, maio-ago. 2008. [ Links ]

DALE, R. Globalização e Educação: demonstrando a existência de uma cultura educacional Mundial comum ou localizando uma Agenda Globalmente Estruturada para a Educação? Educação Sociedade e Cultura, v. 25, n. 87, p. 423-460, ago. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302004000200007 [ Links ]

DELORS, J.; AL-MUFTI, I.; AMAGI, I.; CARNEIRO, R.; CHUNG, F.; GEREMEK, B.; GORHAM, W.; KORNHAUSER, A.; MANLEY, M.; QUERO, M. P.; SAVANÉ, M.-A.; SINGH, K.; STAVENHAGEN, R.; SUHR, M. W.; NANZHAO, Z. Educação um tesouro a descobrir: relatório para a UNESCO da Comissão Internacional sobre Educação para o século XXI. São Paulo: Cortez Editora, 1996. [ Links ]

DUARTE, N. As pedagogias do “aprender a aprender” e algumas ilusões da assim chamada sociedade do conhecimento. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Belo Horizonte, n. 18, p. 35-40, dez. 2001. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782001000300004 [ Links ]

FREITAS, R. G.; COELHO, H. R. Futuro antecipado da Educação: OCDE e controle do conhecimento global. Revista Roteiro, Joaçaba, v. 44, n. 3, p. 1-24, jan.-dez. 2019. https://doi.org/10.18593/r.v44i3.21401 [ Links ]

HYPÓLITO, Á. M.; JORGE, T. Pisa e Avaliação em larga escala no Brasil: algumas implicações. SISYPHUS - Journal of Education, v. 8, n. 1, p. 10-27, 2020. https://doi.org/10.25749/sis.18980 [ Links ]

JIMENEZ, S. V. Consciência de classe ou cidadania planetária? Notas críticas sobre os paradigmas dominantes no campo da formação do educador. Mimeo: Fortaleza, 2003. [ Links ]

KUENZER, A. Z. Trabalho e escola: a flexibilização do ensino médio no contexto do regime de acumulação flexível. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 38, n. 139, p. 331-354, abr.-jun. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302017177723 [ Links ]

LIBÂNEO, J. C. Políticas educacionais no Brasil: desfiguramento da escola e do conhecimento escolar. Cadernos de Pesquisa, v. 46, n. 159, p.38-62. jan.-mar. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/198053143572 [ Links ]

LIBÂNEO, J. C. A desfiguração da escola e a imaginação da escola socialmente justa. In: MENDONÇA, S. G.; MIGUEL, J. C.; MILLER, S.; KÖHLE, E. C. (ed.). (De)formação na escola: desvios e desafios. São Paulo: Editora Cultura Acadêmica, 2020. p. 33-51. [ Links ]

MOTTA, V. C.; FRIGOTTO, G. Por que a urgência da reforma do ensino médio? Medida Provisória nº 746/2016 (Lei nº 13.415/2017). Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 38, n. 139, p. 355-372, abr.-jun. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302017176606 [ Links ]

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT - OCDE. La definición y selección de competencias clave: resumen ejecutivo. [s.l.]: Publicações OCDE, 2005. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.deseco.ch/bfs/deseco/en/index/03/02.parsys.78532.downloadList.94248.DownloadFile.tmp/2005.dscexecutivesummary.sp.pdf . Acesso em: 28 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT - OCDE. Preliminary reflections and research on knowledge, skills, attitudes and values necessary for 2030. 2016. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/ . Acesso em: 28 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT - OCDE. Education 2030: The Future of Education and Skills. Position paper. 2018a. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/ . Acesso em: 28 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT - OCDE. Preparing our Youth for an Inclusive and Sustainable World: The OECD PISA global competence framework. 2018b. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.oecd.org/education/Global-competency-for-and . Acesso em: 28 jun. 2021. [ Links ]

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT - OCDE. Trabalhando com o Brasil. OCDE: Políticas melhores para uma vida melhor. 2018c. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.oecd.org/latin-america/Active-with-Brazil-Port . Acesso em: 26 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT - OCDE. Learning Compass 2030. 2019a. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/learning-compass-2030/ . Acesso em: 20 mar. 2021. [ Links ]

ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT - OCDE . Future of Education and Skills 2030: a Series of Concept Notes. 2019b. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/teaching-and-learning/learning/learning-compass-2030/OECD_Learning_Compass_2030_Concept_Note_Series.pdf . Acesso em: 26 jul. 2021. [ Links ]

PAPADOPOULOS, G. S. Education 1960-1990: The OCDE Perspective. Paris: Publicações da OCDE, 1994. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, R. S. A política de competências e habilidades na educação básica pública: relações entre Brasil e OCDE. 2016. 284 f. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, 2016. [ Links ]

POPKEWITZ, T.; LINDBLAD, S. A fundamentação estatística, o governo da educação e a inclusão e exclusão sociais. Educação e Sociedade, Campinas, v. 3, n. 136, p. 727-754, jul-set., 2016. https://doi.org/10.1590/ES0101-73302016165508 [ Links ]

REDE BIBLIOTECAS ESCOLARES - RBE. Futuro da Educação e Competências 2030 - Bússola de Aprendizagem 2030 da OCDE. 2020. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://blogue.rbe.mec.pt/futuro-da-educacao-e-competencias-2030-2383031 . Acesso em: 26 nov. 2021. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, D. História das Ideias Pedagógicas no Brasil. 4. ed. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2013. [ Links ]

SAVIANI, D.; DUARTE, N. (org.). Pedagogia histórico-crítica e luta de classes na educação escolar. Campinas: Autores Associados, 2015. [ Links ]

SCHULTZ, T. W. O Capital Humano: investimentos em educação e pesquisa. Trad. Marco Aurélio de Moura Matos. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1973. [ Links ]

SECRETARIA DE EDUCAÇÃO DE GOIÁS - SEDUC/GO. Documento Curricular para Goiás (DC-GO). Goiânia: CONSED/UNDIME Goiás, 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://cee.go.gov.br . Acesso em: 10 fev. 2022. [ Links ]

SILVA, M. A.; SILVA, E. F. Para onde vai o direito à Educação? Revista Artes em Educar, Rio de Janeiro, v. 6, n. especial II, p. 188-206, 2020. https://doi.org/10.12957/riae.2020.51884 [ Links ]

1 The DC-GO is composed of four volumes: Volume one - Pre-school Education; Volume two - Elementary School/First Years; and Volume three - Elementary School/Last Years, which were approved by the Goiás State Board of Education (CEE/GO) on December 6, 2018. Volume four, approved and ratified by the CEE/GO on October 8, 2021, deals specifically with the New High School, which is expected to come into force gradually in 2022.

2 Document sent to the management teams of the Municipal Convened Teaching Units that make up the Municipal Teaching Network of Aparecida de Goiânia/GO (SEDUC/GO, 2018).

3 Note that the High School Reform - Law No. 13.415/2017 expresses a form of control and direction of students towards their place as a workforce in class society (Kuenzer, 2017).

Received: August 05, 2021; Accepted: March 07, 2022

texto en

texto en