Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Share

Revista Brasileira de Educação

Print version ISSN 1413-2478On-line version ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.27 Rio de Janeiro 2022 Epub Dec 23, 2022

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782022270110

ARTICLE

Public and private schools: social representations of teachers

ISecretaria de Educação do Município de Osasco, Osasco, SP, Brazil.

IIUniversidade Ibirapuera, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

The objective of this research is to identify the social representations of teachers about public and private schools. Questionnaires with closed and open questions were applied to 87 teachers who work in formal education institutions in the metropolitan region of São Paulo. Data were analyzed with the support of the Descending Hierarchical Classification. The results pointed to representational elements regarding the public school about the lack of commitment of the parents, the imposition and lack of government support, lack of resources and investments, free education, and teacher devaluation. Regarding the private school, these teachers indicated the existence of institutional and parental support, of financial conditions, of paid teaching and learning, of apostilled content and knowledge for the labor market. It is hoped that discussions of these results will contribute to thinking about effective educational policies for both segments.

KEYWORDS teacher; education; qualitative research; social representation

O objetivo desta pesquisa é identificar as representações sociais de professores sobre a escola pública e a particular. Foram aplicados questionários com questões fechadas e abertas para 87 professores que atuam em instituições de ensino formal na região metropolitana de São Paulo. Os dados foram analisados com o apoio da Classificação Hierárquica Descendente. Os resultados apontaram elementos representacionais a respeito da escola pública sobre a falta de compromisso dos pais, a imposição e falta de apoio governamental, a falta de recursos e investimentos, o ensino gratuito e a desvalorização do professor. No que se refere à escola particular, esses professores indicaram a existência de suporte institucional e dos pais, de condições financeiras, de ensino-aprendizagem pago, de conteúdo apostilado e de conhecimentos para o mercado de trabalho. Espera-se que as discussões desses resultados contribuam para se pensar políticas educacionais eficazes para os dois segmentos.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE docente; educação; pesquisa qualitativa; representação social

El objetivo de esta investigación es identificar representaciones sociales de profesores sobre la escuela pública y particular. Se aplicaron cuestionarios con cuestiones cerradas y abiertas para 87 profesores que actúan en instituciones de enseñanza formal en región metropolitana de São Paulo. Los datos fueron analizados con apoyo de clasificación jerárquica descendente. Los resultados apuntaron elementos representacionales respecto la escuela pública sobre la falta de compromiso de los padres, la imposición y falta de apoyo gubernamental, falta de recursos e inversiones, educación gratuita y desvalorización del profesor. En lo que se refiere a la escuela particular, estos profesores indicaron la existencia de soporte institucional y de los padres, de condiciones financieras, de enseñanza-aprendizaje pagado, de contenido apostillado y conocimientos para el mercado de trabajo. Se espera que discusiones de estos resultados contribuyan a pensar políticas educativas eficaces para los dos segmentos.

PALABRAS CLAVE docente; educación; investigación cualitativa; representación social

INTRODUCTION

The Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil (CRFB) of 1988 provides for two types of schools: public and private. These two types of schools are subdivided into for-profit and non-profit. Non-profit private schools are classified as philanthropic, faith-based, and community. A private school is any of the ones maintained by an individual or legal entity governed by private law. And all these schools have the right to freedom of education as long as they comply with the general norms of the Brazilian education system, the constitutional and legal norms. When profitable, private schools cannot depend on public funds and must support themselves with resources from their presence in the market (Brasil, 2016).

Public investment in education in elementary and secondary education in Brazil in relation to all member and partner countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is significantly higher than the portion dedicated to higher education. Public institutions in the early years of elementary school have, on average, more than five students per classroom compared to private institutions (Brasil, 2017).

In relation to teachers’ salaries, Brazil also has an initial value well below the average when compared to the averages of OECD countries, data that could or could not guide the attractiveness and/or choice of the profession. Furthermore, these teachers have less opportunity to allocate time to activities outside the classroom, such as preparing classes and collaborating with other teachers or students who have learning difficulties (Brasil, 2017).

According to research carried out by Lima and Sales (2007), teachers from public and private schools have a negative representation of public school teaching. In this context, students are considered underprivileged in the cognitive and cultural aspects, due to the teachers’ lack of commitment to the students’ teaching and learning process.

By generating and communicating interactions within and between groups, knowledge becomes a factor in collective life, which can reflect representations that are both constructed and acquired, thus knowledge becomes a social phenomenon. For Moscovici (2012), social representations refer to preparation for action, both by leading the behavior and modifying and reconstituting the elements of the environment in which the behavior must take place. The human is a thinking being who formulates questions and seeks answers and, at the same time, shares the realities represented by him.

In the dynamic approach proposed by Moscovici (2012), two processes give rise to representations: objectification and anchoring. The analysis of these processes allows us to understand how the functioning of the cognitive system interferes with the social and how the social interferes with cognitive elaboration. Objectification is the process through which a representation is crystallized: abstract notions are transformed into images whose internal content, after being decontextualized, forms a figurative nucleus to, finally, transform the images into elements of reality. Anchoring is a process that transforms something strange, disturbing, and intriguing into particular categories, and compares it to a paradigm of a category that is considered to be appropriate. The first creates reality itself, the second gives it meaning.

It is the explanation of the link between objectification and anchoring that allows us to understand certain behaviors since the figurative nucleus of the representation depends on the relationship that the subject maintains with the object and on the purpose of the situation. The world changes faster than the idea that is made of it. The transformation of the complex into the simple (objectification) and the strange into the familiar (anchoring) allows an integration of the new and the unknown (Moscovici, 2012).

However, it is necessary to consider that the fact that social representations have their origins in the socio-structural and dynamic conditions of a group does not prevent individuals from giving these representations a unique touch. Each one is subject to particular experiences even though they are part of the same social group, which, in turn, makes possible different perceptions and apprehensions of an object, in relation to other individuals in their group.

In this sense, knowing what teachers think in the segments of the public and private education network, identifying and analyzing what makes them different as professionals, depending on the context in which they are inserted, what values and social representations are embedded in their conceptions of school, may help to understand certain choices.

The understanding of the teacher’s social representations about the spaces they perform, and the symbolic exchanges of teaching and learning contribute greatly to understanding the place they occupy in society, their space of action, a place of living values and norms that help them to solidify and create identity characteristics (Cardoso, Batista and Graça, 2016).

The school universe, in its multiple forms and possibilities, interferes with the taking of a position by the same teacher, whether working in public or private schools (Lima and Sales, 2007). In this way, it is necessary to understand the experiences lived and resignified by teachers or even the possible influences of relationships and social representations marked by status and professional devaluation.

Therefore, the objective of this research is to identify the social representations of teachers about public and private schools. It is expected that the understanding of the results of this study will be able to indicate the predictive social representations that guide the behaviors of this group and allow the discussion for the researched contexts.

METHODOLOGICAL COURSE

The method used was a qualitative approach, exploratory and descriptive, based on the Theory of Social Representations. The research was carried out in three educational institutions, two public and one private, located in the western region of São Paulo.

The inclusion criteria established for participation were teachers who had an employment relationship with the educational institution (public and private schools) and who agreed to participate in the research. In such a way, the research was developed with a non-probabilistic sample of 87 teachers, 65 teachers from the public network, and 22 from the private sector of education.

For data collection, a sociodemographic questionnaire and one composed of four questions were proposed to each participant, in the following order: What do you think about public school? What do you think about private school? What are the advantages and disadvantages of public school? What are the advantages and disadvantages of private school? This script of questions sought to contemplate the ideas, beliefs, and values socially shared by the participants about public and private schools.

The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the promoting institution, opinion No. 2,252,692/2017. Data collection took place in two stages: initially, prior contact was made with the participants to present the research objectives, clarifying the procedures to be followed; then the data were collected by the researcher herself, collectively in the teachers’ rooms of the educational institutions, on days and times previously scheduled with the responsible managers. Therefore, the research took place in three meetings in each institution (a total of nine meetings). The questionnaires were answered for an average of 30 minutes per group of participants.

Participants’ answers were processed using the software Interface de R pour analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires (IRAMUTEQ), which made it possible to organize the answers through the Descending Hierarchical Classification, which is presented in the present study in the format of dendrogram figures. These dendrograms present the percentages of the classes and the words (parallel to their utterance contexts) with their frequencies and attributions of a degree of significance with the class through the chi-square test (Camargo and Justo, 2018). Each class comprises a set of text segments (ST), which are related by the vocabulary used, referring to specific semantic fields. The results of the dendrograms are described following the horizontal order (from left to right) of class distribution.

SOCIAL REPRESENTATIONS ON PUBLIC SCHOOLS

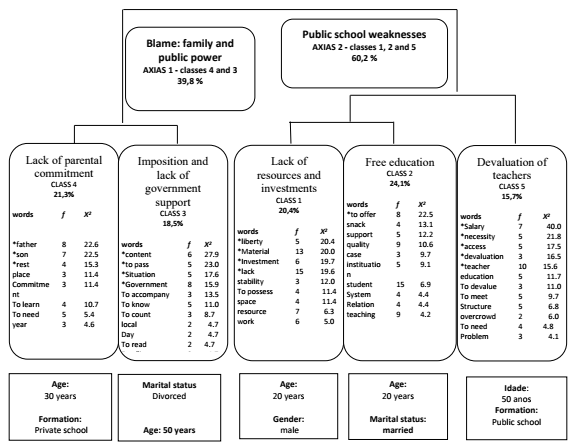

The results of the first monothematic corpus are presented in Figure 1, in the format of a dendrogram with the distribution of classes, which were categorized according to semantic inferences from their content:

Caption: f = frequency; x2: chi-square; * level of significance of the word with the class p<0.0005. Source: Elaborated on the results of the IRaMuTeQ software.

Figure 1 - Dendrogram referring to the public school corpus.

AXIS 1: BLAMING: FAMILY AND GOVERNMENT

Lack of parental commitment (class 4): corresponds to the second largest class, since it represents 21.3% of ST retained for analysis (N=23). This class mainly presents the answers given by teachers aged 30 years, and who reported having their basic training coming from a private school. This result may be related to the possibility that these teachers have lived their school years with the participation and/or demands of their parents. And they can still attribute the commitment of these parents to the context of the private school.

The contents that make up this class highlight the lack of commitment of parents to monitor and concern themselves with the development of their children’s formal education within the public school. The following ST exemplifies the content of this class:

The public agency is poorly structured to receive children or parents who have to work and have nowhere to leave their children. Most of them don’t care if their child is learning or not, what matters is that they have a place to stay. (Postgraduate teacher, 2018)

Imposition and lack of government support (class 3): corresponds to the second lowest class since it represents 18.6% of the ST retained for analysis (N=20). This class mainly presents the answers given by divorced teachers, aged 50 years. This result may be related to the possibility that these teachers have a more refined political critical sense, as they were an eyewitness of a different public school in other times of government regimes. The contents that make up this class point to the lack of support and the imposition of models with curricular contents by the government as negative factors in public schools. The following ST exemplifies the content of this class:

In theory, the public school is a wonderful organ, but it has become a place of sadness in practice, due to a government that aims at the non-thinking being and oppresses its professionals, and the majority public of this school are people who are there to avoid starvation. (Postgraduate teacher, 2018)

AXIS 2: WEAKNESSES OF THE PUBLIC SCHOOL

Lack of resources and investments (class 1): corresponds to 20.4% of the ST retained for analysis (N=22). This class mainly presents answers given by male teachers, aged 20 years. These results may be related to the possibility that these young teachers have a practical ideal of education based on the use of materials that optimize the teaching-learning processes.

The contents that make up this class show that the disadvantages of public school are related to the lack of material and structural resources, which demand the need for investments. The following ST exemplifies the content of this class:

The public school could be much better if it had a real appreciation of the government in investments. Therefore, the disadvantages are the lack of investment in physical resources, laboratories, libraries, and computer room, among others. (Postgraduate teacher, 2018)

Free education (class 2): corresponds to the highest class since it represents 24.1% of the ST retained for analysis (N=26). This class mainly presents the answers given by married teachers, aged 20 years. These results may be related to the possibility of gratuity not being an existing reality in their family responsibilities. Therefore, free education is something highlighted by them that draws the attention of this group of teachers.

The contents that make up this class present objectified representational elements that remind us that the public school is a public service offered free of charge by the government to all individuals in a universal way. Jodelet (2001) states that objectification is the process by which the individual reabsorbs an excess of meanings, materializing them, that is, it is a process of formal construction of knowledge, by the individual. The following ST exemplifies the content of this class: “It has greater accessibility to the population. It offers school lunches, uniforms, and school supplies in some cases.” (Postgraduate teacher, 2018).

Teacher devaluation (class 5): corresponds to the lowest class since it represents 15.7% of the ST retained for analysis (N=17). This class mainly presents the answers given by teachers aged 50 years and who declared their training coming from a public school. These results may be related to the possibility that these teachers experienced a time when the public school teacher was more valued.

The contents that make up this class indicate that, regarding the devaluation of the teacher’s profession in public schools, the representational element low remuneration stands out. The following ST exemplifies the content of this class: “The teacher needs to take from his salary to meet needs, the rooms are overcrowded and there is a devaluation of the teaching staff.” (Postgraduate teacher, 2018).

SOCIAL REPRESENTATIONS ON PRIVATE SCHOOLS

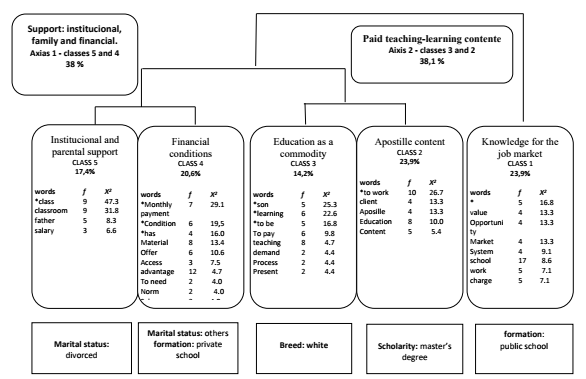

The results of the second monothematic corpus are presented in Figure 2, in the format of a dendrogram with the distribution of classes, which were categorized according to semantic inferences from their content.

Caption: f = frequency; x2: chi-square; * level of significance of the word with the class p<0.0005. Source: Elaborated on the results of the IRaMuTeQ software.

Figure 2 - Dendrogram referring to the private school corpus.

AXIS 1: INSTITUTIONAL, FAMILY, AND FINANCIAL SUPPORT

Institutional and parental support (class 5): corresponds to 17.4% of ST retained for analysis (N=16). This class primarily introduces you to the answers given by divorced teachers. The contents that make up this class highlight that the support of the school and the parents is essential in the context of the private school. However, social representations about private schools, as well as public schools, are based on truths conveyed by common sense, devoid of criticism, and crystallized in the form of social representations. This inference can be observed in this ST: “There are fewer students per class, more technological resources, more parental involvement, making teaching easier.” (Postgraduate teacher, 2018).

Financial conditions (class 4): corresponds to 20.6% of the ST retained for analysis (N=19). This class mainly presents the answers given by teachers who have declared other marital status and who come from training in a private school. The contents that make up this class indicate that private schools have adequate and sufficient financial conditions and resources that allow them to offer quality education and better working conditions for teachers. The following ST exemplifies the content of this class:

It is one where education is offered in a private way, that is, a monthly fee is paid to have access to education, and this education is offered in accordance with the school’s conceptions with its norms and rules. The advantages are quality teaching, good facilities for students, comfortable rooms, materials to work with. The disadvantages are that education is not free and food and lunch are not offered. Access to this education is for the few, only for those who can pay for it. (Postgraduate teacher, 2018)

AXIS 2: PAID TEACHING-LEARNING CONTENT

Education as a commodity (class 3): corresponds to the lowest class since it represents 14.2% of the ST retained for analysis (N=13). This class mainly presents the answers given by the teachers who declared white color. The contents that make up this class show the non-free nature of teaching and learning in the private school. At the same time, they sell an education like any other commodity. The following ST exemplifies the content of this class:

Incentives to teaching practices are recognized as subsidies aimed at education and learning, where, in turn, students feel motivated to knowledge. Those responsible for funding these studies are present in the evolution of their children. The disadvantage is when those responsible see the private school as an obligation for teachers to teach because they are paying, and this is seen by the children as well. (Postgraduate teacher, 2018)

Apostille content (class 2): corresponds to one of the largest classes, since it represents 23.9% of ST retained for analysis (N=22). This class mainly presents the answers given by teachers who declared to have a master’s degree. The contents that make up this class show that the apostille content is an instrument widely used in the context of the private school. The following ST exemplifies the content of this class:

It is considered a company because it treats its students as customers. Its teaching is usually more advanced, working normally by an apostille method. The advantage is quality teaching. The downside is a lot of pressure on the student. (Postgraduate teacher, 2018)

Knowledge for the labor market (class 1): also corresponds to one of the largest classes, since it represents 23.9% of the ST retained for analysis (N=22). This class primarily presents answers given by teachers aged 40 and 50. The contents that make up this class show that the private school is concerned with preparing students for the job market. The following ST exemplifies the content of this class:

It provides more rigorous and systematic teaching geared toward the demands of the job market. It presents well-guided pedagogical proposals and with constant demand from coordinators and managers, which generates more involvement of professionals. (Postgraduate teacher, 2018)

DISCUSSIONS

PUBLIC SCHOOL

The process of blaming the student for educational problems derives from an objectified movement produced throughout history (Sant’ana and Guzzo, 2016). Moscovici (2012) explains that objectification unites the idea of unfamiliarity with that of reality, thus becoming the true essence of reality. Firstly, perceived as a purely intellectual and remote universe, objectification appears and is perceived as physically and accessible (Moscovici, 2012).

The student who did not follow the contents taught in the classroom was often the one who was socioeconomically underprivileged, and who, for some reason, did not incorporate the rules imposed on everyday school life (Boto, 2014). These exclusionary practices labeled and stigmatized students, as they exclusively attributed the cause of school complaints to the student, that is, the problems were focused on individual characteristics and on the students’ family and social environment.

This strange scenario that can disturb and intrigue has taken it for granted for students to drop out of school at the behest of their parents. According to the dynamic character that a social representation has (Moscovici, 2012), this reality was anchored according to the paradigms of the current public school. For Jodelet (2001), objectification does not guarantee the organic insertion of knowledge. It is the anchoring process, in a dialectical relationship with objectification, that will guarantee it. The anchoring process concerns the social rooting of representation. Its function is to perform the cognitive integration of the object represented in a preexisting system of thought. In this way, the new elements of knowledge are placed in a network of more familiar categories.

According to the Law of Directives and Bases of National Education (LDBEN), education is the responsibility of the family and the State (Brasil, 1996). However, the blame for the problems in the public education network also affects the participants of the educational process, such as teachers, students, and their families. From an integral and multidisciplinary vision of the human being, the formal school can stimulate autonomy, critical participation, and creativity of individuals. For this, it is necessary to consider the family, community, and social context of the students (Sant’ana and Guzzo, 2016).

In research carried out by Freitas (2014) with future teachers in an interventional project carried out in a public school, it was observed that the approximation of these undergraduates made possible the concrete experience with the working conditions of teachers, students, family members, and community. This provided an opportunity to raise awareness with a sense of co-responsibility in the face of existing problems. Therefore, the experience served to demystify negative ideas of what they heard about the public school in order to familiarize themselves with the reality witnessed. Bringing the family closer to the school could also provide better awareness of the daily problems experienced.

According to Lima and Machado (2018), parents do not participate in their children’s school life due to lack of time since they work most of the day; and because the meeting schedules are irreconcilable with the work routine. In such a way, it can be pointed out a failure of communication between parents and the school, because it is as if the school did not prioritize the participation of parents in the meetings. It is worth mentioning that many have parents who do not show interest in knowing the school context of their children due to their low expectations in relation to school.

With regard to the speeches of the participants that point to imposition and lack of government support, it is necessary to understand that, in the current neoliberal scenario, education is seen as a commodity and the public sector is attributed the responsibility for the crisis and inefficiency of the Brazilian educational system. Some teachers, in turn, feel oppressed in the face of circumstances that negate their teaching activity and blame the government for the problems existing in public schools (Oliveira, 2009; Sant’ana and Guzzo, 2016).

This lack of critical perspective on the conduction of educational policies, within the relations of production in capitalism, is configured as an obstacle to the awareness of teachers about the reality experienced. This does not mean that the public authorities do not have responsibilities in the formulation and implementation of educational policies, since they belong to a larger group that has control over the country’s social, economic, and political system, which is connected to capitalist interests (Sant’ana and Guzzo, 2016).

In addition to the salary issue, teachers claim to be devalued by the disrespect and disregard of the government, given the precarious working conditions. In order to qualify a representation as social, it is necessary to define the agent that produces it and emphasize that the function of representation is to contribute exclusively to the processes of behavior formation and orientation of social communications (Moscovici, 2012). In this context, these teachers point out that education is not a priority for government officials (Nascimento and Rodrigues, 2017).

According to Soares (2014), the effectiveness and quality of education depend on the attention and responsibility shared between public power, civil society, and other education professionals. In this sense, Nascimento and Rodrigues (2017) emphasize that education has served to maintain the capitalist-based social structure and the transformation of this education depends on the movement of society. In this way, revolutionary actions are necessary, which cross the walls of the school and reach everyone’s awareness of the promotion of education with equity.

According to a survey on working conditions and health of teachers carried out in a public school system in southern Brazil, the lack of pedagogical teaching materials in the classroom was mentioned by 50.4% of the interviewed teachers (Silva and Silva, 2013). Facing difficulties and challenges in public educational institutions can bring frustrations to teachers, as they perceive themselves as part of a gear inserted in a larger, often inaccessible system (Nascimento and Rodrigues, 2017).

The use of technological resources also presents scarcity and/or deficiencies in the public school, due to the difficulties of acquisition, maintenance, and appropriation by the teachers of these technologies. In contrast, teachers are faced with students at school who were born and grew up in the midst of technological effervescence, so they can be considered digital natives (Piedade and Pedro, 2019).

The difficulties encountered by teachers in public schools are also related to the lack of their own financial resources, due to low remuneration. In this context, many take on secondary jobs and work double shifts between family responsibilities and work. Despite these challenges, teachers need to enter the classroom and forget about problems, and still find time to reinvent stimulating ways of teaching, in order to keep students’ attention (Brasil, 2017).

Alves-Mazzotti and Wilson (2004) explain that the teacher’s competencies depend on a series of structural issues that go beyond the sphere of the classroom, which imply the support of the school, the family, society, and the public power, in short. The lack of structure and materials at school and the resulting violent scenarios in the family and in society are obstacles that teachers face in public schools. Therefore, these professionals need organizational resources among their peers within the school institution, as well as organizing their own creative skills to mobilize appropriate didactic-pedagogical resources for each teaching-learning situation.

Despite the free and universal character of the public school being a right instituted by the LDBEN (Brasil, 1996), it is possible to notice the welfare image transmitted in the speeches of the teachers of the present research. According to Martínez and Pinho (2016), the lunch offered in public schools is a right of users guaranteed by the National School Feeding Program (PNAE), which promotes food supplementation and healthy behaviors in public schools. In this sense, it can be emphasized that exclusion does not occur in the access to school, but in the discriminatory educational process that is sometimes found in educational institutions.

On the other hand, some teachers anchor that public schools should be geared towards the development of citizens with critical thinking, with an emphasis on the diversity of all individual and/or group values and beliefs. Jodelet (2001) explains that even if an object is inserted in the same social context, it can be seen from different perspectives and present different systems of values or counter-values.

Boto (2014) says that, since the mid-19th century, in Portugal, teachers’ salaries were low and only those who did not have the capacity to work in other positions valued by society applied for positions designated for teaching. Teaching in public schools was encyclopedic, and to change this scenario it was necessary to simplify the program, activate severity assessments, and increase salaries and benefits for teachers.

Despite the wage devaluation, some changes have marked teaching work overtime, as a craft within a capitalist society. In addition, teaching learning began to be built in practice, there was an appreciation of teaching work, women began to exercise and dominate in greater numbers in the magisterium, and people began to believe in the globalization of teaching (Figueiredo and Bonini, 2017).

Currently, the modes of organization of the capitalist model, under the influence of neoliberal policies, have caused the fragmentation and precariousness of the teacher’s work (Sant’ana and Guzzo, 2016; Figueiredo and Bonini, 2017). Faced with this scenario, teachers have a role opposite to capitalist assumptions, as their work is not aimed directly at transforming concrete nature, but at mediating individuals’ awareness of the reality around them (Abu-El-Haj and Fialho, 2019).

Therefore, representational elements were identified in the responses of the teachers participating in the research that negatively affect the public school. For this, these teachers blame the lack of commitment of parents and/or guardians of students and the impositions and lack of support from the public power with regard to the adversities that occur in public schools. The weaknesses of the public school pointed out by these teachers are related to the devaluation of the teacher, and the lack of material resources and investments, within a welfare scenario.

PRIVATE SCHOOL

In Brazil, the process of developing a business sector in education is old, dating back at least to the period of the military dictatorship. However, this was disguised, as the legislation prohibited educational institutions, by their nature, from making a profit. It was only with the enactment of the 1988 CRFB that the possibility of for-profit schools was made explicit. The subsequent regulation of this device in the LDBEN and in the complementary legislation accelerated its growth (Brasil, 1996; Brasil, 2016). These dimensions demonstrate a much broader process of transformation of the educational sector into a mercantile activity. Likewise, this transformation is worldwide, representing one of the dimensions of globalization. In view of this, the question of education as a commodity is raised (Oliveira, 2009).

Education is not a commodity since it refers to the expression of a desire or a banner of struggle rather than something that is mirrored in reality. It can only be accepted as a must, as a programmatic formulation (Oliveira, 2009). In this sense, as a commodity, private education has a price, a monetary value that fluctuates within the logic of supply and demand, not being accessible to everyone.

In the outsourcing of the pedagogical process, private for-profit institutions sell to schools what is disseminated, that is, as teaching systems that offer services and products, such as teaching materials for students and teachers, which include handouts and cd-roms, in-service teacher training and monitoring of the use of acquired materials. This purchase represents more than the simple acquisition of teaching materials. For Saviani (2010, p. 771, our translation), the implication of the term system, when it is adopted in the educational field, presupposes coordinated and integrated option of parts in “[…] a whole that articulates a variety of elements that, when integrated into the whole, do not lose their own identity.”.

It seems that these private institutions, more than mere suppliers of materials and equipment, start to happen the design of the local educational policy and the organization of the teaching and administrative work carried out in each of the teaching units. The private institutions that offer the education systems, with some exceptions and variations, tend not only to determine the contents to be developed by the teachers, but also the working times, routines, and teaching methodology. The performance of the assistance provided also monitors the implementation of the purchased material, with variations in regularity and practices.

The representation of a private school as a company that forms competitive and content-oriented individuals for the job market, by those surveyed, seems to be based on outdated concepts and visions about the world of work. In this sense, more than content, preparation for the world of work requires skills improvement.

Variables related to the school level, such as the number of computers in the school, principal and student selection process, schooling, age, and salary of teachers can have very small effects on student performance. However, having one or more computers and more than 20 books at home improves learning, as does having electricity and living in small families (Menezes-Filho, 2012).

Menezes-Filho (2012) explains that, in the Brazilian public system, class size does not seem to be important to explain school performance. On the other hand, the number of class hours has a positive and statistically significant effect, that is, students who spend between four and five hours or more in the classroom perform better than those who spend less than four hours. This provides a public policy proposal: that students stay in school longer, even if it means increasing class sizes.

The participation of families in their children’s school life is also highlighted in the representation of the private school. Menezes-Filho (2012) shows that the variables that most explain school performance are family and student characteristics, such as the mother’s education, color, school delay and previous failure, the number of books, the presence of a computer at home and work outside from home.

Sant’ana and Guzzo (2016) state that family factors and social groups interfere much more with student performance than political and financial resources committed to education. Despite the support offered by the private institution and the parents, the responses of the teachers participating in the research showed that private school also has disadvantages related to the lack of freedom for the development of teachers’ autonomy in the teaching-learning processes.

For Oliveira (2018), there is a progressive shift from the concept of professional qualification to the notion of professional competencies. The old concept of qualification was related to the organized and explicit components of worker qualification: school education, technical training, and professional experience. It was related to the educational level, formal schooling and its corresponding diplomas, and, in the world of work, to the salary scale, positions, and the hierarchy of professions.

In the competence model, it is not only the possession of school or technical-professional knowledge that matters but also the ability to mobilize them to solve problems and face the unforeseen in the work situation. The unorganized components of training are extremely important. The competency model thus refers to the individual characteristics of workers.

In this sense, it is clear that much more than a critical view, the ability of the private school to prepare the student for the job market is represented by common sense truths, crystallized in a social representation that is detached from the current world of work. The discrepancy between the teaching of public and private schools renders the idea that individual effort is enough for the deserving of equal opportunities among the members of a society is useless. This idea encourages greater competition among students, and consequently the frustration of those who do not meet the demands placed by the government (Lima and Machado, 2018). These practices of blaming the underprivileged linked to the public power’s lack of interest in public schools and education, in general, can be configured as a type of violence.

CONSIDERATIONS

Social representations are filters that help to understand the world and guide behaviors and interpersonal relationships. The results of the present research confirm crystallized common sense truths, with social representations of a public school without quality, poorly paid teachers, disinterested in the formation of students; and the private school, socially valued, as one that offers differentiated education, that prepares the student for the job market, whose teachers are well paid and parents are present in their children’s school life.

For those surveyed, it is the institutional, economic, and cultural problems that affect the quality of public schools. Among these obstacles, overcrowded classes, schools lacking material resources, low salaries, and the devaluation of the profession stand out. Teachers’ social representations of public education see their audience as disadvantaged in learning, mainly because of their social context.

In relation to the student in private schools, the teacher is intimidated by the power that students have and resents having to go out of his way to satisfy them. Public and private education in Brazil have very different characteristics and consequently provoke different representations of schools.

Identifying social representations about phenomena related to the teacher’s professional practice offers a privileged view of the issues that guide the functioning of the school and the existing relationships in this social space. The ideological character has always permeated discussions about the public and private spheres regarding the provision of education services. The center of this discussion lies in the differences in the socializing purpose of these institutions. In the past, this was limited between Church and State. Currently, with the effective participation of secular private institutions, in addition to ideological issues, financial issues also affect this discussion.

It so happens that these distorted visions of reality end up promoting the permanence of the status quo, making it difficult to recognize another reality and to support complex processes of change in schools: there are high-quality public schools and private schools that do not meet the minimum necessary for the development of your students. The Manichean discourse of those surveyed refers to the particular binomial, good versus public, bad.

Moscovici (2012, p. 35) states that “[…] we organize our thoughts according to a system that is conditioned, both by our representations and by our culture. We see only what the underlying conventions allow us to see, and we remain unaware of those conventions.”. However, he adds that: “[…] we can through effort become aware of the conventional aspect of reality and then escape some of the demands they impose on our perceptions and thoughts.” (idem).

Considering that there is an intrinsic relationship between social representations and practices, it is concluded that one of the first steps to change teachers’ representations of public and private schools would be to make them aware of their representations and the differentiated treatment they guide, as well as the negative consequences of this practice for the students.

This, however, would not be enough. A broad program of transformations in the school system is necessary, which involves all those involved, in a way that values their experiences and emphasizes their central roles in favor of the construction of a new school, which is attentive to the changes of the contemporary world and meets the needs of students, especially those less fortunate.

The public school is a guaranteed right, and the private school is a contracted service. Both should move towards the same goal, which is to offer quality education capable of empowering the student in their training.

REFERENCES

ABU-EL-HAJ, M. F.; FIALHO, L. M. F. Formação docente e práticas pedagógicas multiculturais críticas. Revista Educação em Questão, Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, v. 57, n. 53, p. 1-27, e-17109, jul./set. 2019. https://doi.org/10.21680/1981-1802.2019v57n53ID17109 [ Links ]

ALVES-MAZZOTTI, A. J.; WILSON, T. C. P. Relação entre representações sociais de “fracasso escolar” de professores do ensino fundamental e sua prática docente. Revista Educação e Cultura Contemporânea, Rio de Janeiro, v. 1, n. 1, p. 75-87, jan./jun. 2004. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://revistaadmmade.estacio.br/index.php/reeduc/article/view/1987/972 . Acesso em: 02 out. 2020. [ Links ]

BOTO, C. A liturgia da escola moderna: saberes, valores, atitudes e exemplos. Revista História da Educação, Porto Alegre, v. 18, n. 44, p. 99-127, set./dez. 2014. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S2236-34592014000300007 [ Links ]

BRASIL. [Constituição (1988)]. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília: Senado Federal, Coordenação de Edições Técnicas, 2016. (Denise Zaiden Santos - Organizadora). Disponível em: Disponível em: https://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/bitstream/handle/id/518231/CF88_Livro_EC91_2016.pdf . Acesso em: 03 set. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº. 9.394 de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. Diário Oficial [da] União, Poder Executivo, Brasília, DF, 23 de dezembro de 1996. Seção 1, p. 27833. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://portal.mec.gov.br/seesp/arquivos/pdf/lei9394_ldbn1.pdf . Acesso em: 02 out. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira. Panorama da educação: destaques do Education at a Glance 2017. Brasília, DF: Diretoria de estatísticas educacionais, INEP/MEC, set. 2017. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://download.inep.gov.br/acoes_internacionais/eag/documentos/2017/panorama_da_educacao_destaques_do_education_at_a_glance_2017.pdf . Acesso em: 03 set. 2020. [ Links ]

CAMARGO, B. V.; JUSTO, A. M. Tutorial para uso do software de análise textual IRAMUTEQ. Site do Laboratório de Psicologia Social da Comunicação e Cognição [Internet], 2018. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://iramuteq.org/documentation/fichiers/tutoriel-portugais-22-11-2018 . Acesso em: 26 ago. 2020. [ Links ]

CARDOSO, M. I. S. T.; BATISTA, P. M. F.; GRAÇA, A. B. S. A identidade do professor: desafios colocados pela globalização. Revista Brasileira de Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 21, n. 65, p. 371-390, abr.-jun. 2016. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-24782016216520 [ Links ]

FIGUEIREDO, D. C.; BONINI, A. Recontextualização e sedimentação do discurso e da prática social: como a mídia constrói uma representação negativa para o professor e para a escola pública. DELTA, São Paulo, v. 33, n. 3, p. 759-786, jul.-set. 2017. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0102-445099800747799785 [ Links ]

FREITAS, M. F. Q. A pesquisa participante e a intervenção comunitária no cotidiano do Pibid/CAPES. Educar em Revista, Curitiba, PR, v. 30, n. 53, p. 149-167, set. 2014. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.36587 [ Links ]

JODELET, D. Representações sociais: Um domínio em expansão. In: JODELET, D. (org.). As representações sociais. Trad. Tarso Bonilha Mazzotti. Rio de Janeiro: EduERJ, 2001. [ Links ]

LIMA, A. M.; MACHADO, L. B. Famílias de estudantes de escola pública: um estudo sobre relações entre representações sociais e práticas de professoras. Revista Educação e Cultura Contemporânea, Rio de Janeiro, v. 15, n. 38, p. 388-415, jan./mar. 2018. https://doi.org/10.5935/2238-1279.20180019 [ Links ]

LIMA, F. F.; SALES, L. C. As representações sociais do aluno de escola pública partilhadas por professores de língua inglesa que ensinam em escolas públicas e particulares de Teresina. Atos de Pesquisa em Educação, Blumenau, SC, v. 2, n. 1, p. 106-122, 2007. https://dx.doi.org/10.7867/1809-0354.2007v2n1p106-122 [ Links ]

MARTÍNEZ, S. A.; PINHO, F. N. L. G. Política de alimentação escolar brasileira: representações sociais e marcas do passado. Education Policy Analysis Archives, Arizona, EUA, v. 24, n. 66, p. 1-31, jun. 2016. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.2241 [ Links ]

MENEZES-FILHO, N. A. Os determinantes do desempenho escolar no Brasil. In: DUARTE, P. G.; SILBER, S. D.; GUILHOTO, J. J. M. (org.). O Brasil e a ciência econômica em debate: o Brasil do século XXI. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2012. [ Links ]

MOSCOVICI, S. Representações sociais: investigações em psicologia social. Trad. Pedrinho Guareschi. 11. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2012. [ Links ]

NASCIMENTO, I. P.; RODRIGUES, S. E. C. Representações sociais sobre a permanência na docência: o que dizem docentes do ensino fundamental?. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 44, e166148, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1678-4634201711166148 [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, R. O ensino médio e a inserção juvenil no mercado de trabalho. Trabalho, Educação e Saúde, Rio de Janeiro, v. 16, n. 1, p. 79-98, abr. 2018. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1981-7746-sol00116 [ Links ]

OLIVEIRA, R. P. A transformação da educação em mercadoria no Brasil. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 30, n. 108, p. 739-760, out. 2009. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302009000300006 [ Links ]

PIEDADE, J.; PEDRO, N. Análise da utilização das tecnologias digitais por diretores escolares e professores. Revista Educação em Questão, Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, v. 57, n. 52, p. 1-30, e-15905, abr.-jun. 2019. https://doi.org/10.21680/1981-1802.2019v57n52ID15905 [ Links ]

SANT’ANA, I. M.; GUZZO, R. S. L. Psicologia escolar e projeto político-pedagógico: análise de uma experiência. Psicologia & Sociedade, Belo Horizonte, v. 28, n. 1, p. 194-204, jan.-abr. 2016. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1807-03102015aop004 [ Links ]

SAVIANI, D. Organização da educação nacional: sistema e conselho nacional de educação, plano e fórum nacional de educação. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, SP, v. 31, n. 112, p. 769-787, set. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302010000300007 [ Links ]

SILVA, L. G.; SILVA, M. C. Condições de trabalho e saúde de professores pré-escolares da rede pública de ensino de Pelotas, RS, Brasil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, Rio de Janeiro, v. 18, n. 11, p. 3137-3146, nov. 2013. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232013001100004 [ Links ]

SOARES, A. S. A formação do professor da Educação Básica entre políticas públicas e pesquisas educacionais: uma experiência no Vale do Jequitinhonha em Minas Gerais. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, Rio de Janeiro, v. 22, n. 83, p. 443-464, jun. 2014. https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-40362014000200008 [ Links ]

Received: December 02, 2020; Accepted: February 09, 2022

text in

text in