Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Compartir

Revista Brasileira de Educação

versión impresa ISSN 1413-2478versión On-line ISSN 1809-449X

Rev. Bras. Educ. vol.28 Rio de Janeiro 2023 Epub 07-Feb-2023

https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-24782023280019

ARTICLE

Education in human rights from the perspective of teachers in the public network of Rio de Janeiro

ITribunal Regional Federal da 2ª Região, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

IIUniversidade Veiga de Almeida, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

IIICentro Universitário Augusto Motta, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

The objective of this work was to verify whether teachers from the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro have the concern to teach human rights. A questionnaire was applied through the Google Forms platform, with objective and subjective questions, which were answered only by teachers of ensino médio, fundamental II and educação de jovens e adultos, which sought to identify human rights education practices developed by them in the teaching-learning process. From the data collected in the exploratory research, it was concluded that the public-school teachers, despite all the difficulties they face, seek to transmit values and attitudes of respect to human rights, and that, although their teachings are the fruit of their own experience as teachers and citizens, there is a concern to form character, besides only transmitting theoretical knowledge.

KEYWORDS education in human rights; transversality; public school

O objetivo deste trabalho foi verificar se os professores da Região Metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro têm a preocupação de ensinar direitos humanos. Foi aplicado um questionário pela plataforma Google Forms, com questões objetivas e subjetivas, o qual foi respondido por professores que lecionam no ensino médio, no ensino fundamental (anos finais) e na educação de jovens e adultos, com o desígnio de identificar as práticas de educação em direitos humanos desenvolvidas por eles nos processos de ensino-aprendizagem. Pelos dados levantados na pesquisa de caráter exploratório, chegou-se à conclusão de que o professor da escola pública, apesar de todas as dificuldades que enfrenta, procura transmitir valores e atitudes de respeito aos direitos humanos e que, embora seus ensinamentos sejam frutos de sua própria experiência como professor e cidadão, há uma preocupação em formar caráter, além de apenas construir conhecimentos teóricos.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE educação em direitos humanos; transversalidade; escola pública

El objetivo de este trabajo era verificar si los maestros de la región metropolitana de Río de Janeiro tienen la preocupación de enseñar derechos humanos. Un cuestionario fue aplicado por la plataforma de Formularios de Google, con preguntas objetivas y subjetivas, respondidas únicamente por profesores de escuela secundaria, escuela fundamental II y enseñanza de jóvenes y adultos, que buscaban identificar las prácticas de educación en derechos humanos. desarrolladas por ellos en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje. A partir de los datos recogidos en la investigación exploratoria, se concluyó que el profesor de la escuela pública, a pesar de todas las dificultades a las que se enfrenta, busca transmitir valores y actitudes de respeto a los derechos humanos y que, aunque sus enseñanzas son fruto de su propia experiencia como profesor y ciudadano, existe una preocupación por formar carácter, además de transmitir únicamente conocimientos teóricos.

PALABRAS CLAVE educación en derechos humanos; transversalidad; escuela pública

INTRODUCTION

At the international level, the discussion on human rights, henceforth HR, took on a dimension after the barbarities that occurred during the Second World War (1939-1945), which culminated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), approved in 1948 by the General Assembly of the United Nations (UN) (ONU, 1948). This document introduced a concept of universal and inalienable rights into the internal rules of the Member States. For Schütz and Fuchs (2017), the theme of HR became the focus of concerns in the 21st century, being the topic of debates in several international conferences, as well as the object of public policies in several nations of the world, becoming an object of study for numerous researchers, since HR involves our daily lives and are related to themes such as education, work, social exclusion, diversity, equality, alterity, ethics, among others.

At the national level, during the military regime (1964-1985), Brazil experienced a period of drastic reduction in political activities and, consequently, a minimization of the exercise of citizenship. For Candau (2012), from the Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil of 1988 (CRFB/1988), known as the Citizen Constitution, the Brazilian State has made a systematic effort to defend fundamental rights and, responding on many occasions to the demands of different social movements, incorporating in its public policies the affirmation of HR, to progressively expand the inclusion of new rights.

The movements for the democratization of the country led to the recognition by the State that there is no development exclusively in the economic field, without corresponding social and political development, making human rights education, henceforth HRE, a matter of considerable importance.

Education should be understood as the formation of the human being to develop their potentialities of knowledge, judgment, and choice to live consciously in society, which also includes the understanding that the educational process itself contributes both to conserving and to changing values, beliefs, mentalities, customs, and practices. According to Schütz and Fuchs (2017), education is a prerequisite for acquiring civil liberties, since civil rights are intended for the use of individuals with broad mentalities, who, in addition to having learned to read, write, and calculate, have learned to reflect on their actions.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the 2030 Agenda (ONU, 2015), promoted by the UN, to be implemented in all member countries by the year 2030, seek, among other approaches, to ensure inclusive, equitable and quality education, in addition to promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all. This same right was already provided for in Article 26 of the UDHR (ONU, 1948), which stated that everyone has the right to education, aimed at the full development of the human personality, strengthening and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.

Piovesan (2005) teaches that education is both a human right in itself and an indispensable means for realizing other HR. As a right of emancipation, education is how economically and socially marginalized adults and children can combat poverty. Education plays a vital role in women’s autonomy, protecting children from forced labour and sexual exploitation, promoting HR and democracy, protecting the environment, and controlling population growth.

Real protection of HR requires not only universalist, but also specific policies aimed at socially vulnerable groups as victims of exclusion. For Piovesan (2005), the effective implementation of HR requires the universality and indivisibility of rights, added to the value of diversity. Alongside the right to equality, the right to difference emerges dialectically as a fundamental right. It is therefore necessary to overcome inequalities and, at the same time, value diversity, promote redistribution and recognition. Currently, these are the challenges in which the HR issue is situated.

HRE emerges as an important strategy, as it has as its ultimate objective the construction of a society that recognizes the other in its rights. According to Silva (1995), this education must necessarily deal with the realization that we live in a multicultural world. Thus, “[...] education in human rights should affirm that people with different roots can coexist, look beyond the boundaries of race, language, social condition and lead the student to think of a hybridized society.” (Silva, 1995, p. 97, our translation).

In view of the above, this study aimed to verify whether teachers in the Metropolitan Area of Rio de Janeiro are concerned with teaching HR. A survey questionnaire, consisting of objective and subjective questions, was conducted through Google Forms platform. The set of questions were answered by teachers who teach high school, middle school and youth and adult education (YAE), aiming to identify the HRE practices promoted in the teaching-learning processes.

GOVERNMENT POLICIES IN HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION

In the formulation of the CFRB/1988, HRE appears intertwined in order to constitute a general orientation for Brazilian educational policy. The Constitution, known as the Citizen Constitution, paved the way for other historical developments in the areas of education and HR.

Regarding the interrelationship between the right to education and HRE, Candau (2012) asserts that, at first, the reflections on these fields took place independently. However, they gradually approached each other and assumed the perspective that considers HRE as a component of the right to education and an essential element of the quality of education that we want to promote. Thus, these two concerns are intertwined in the search for the construction of an education committed to the formation of subjects of law and the affirmation of democracy, justice, and the recognition of diversity in Brazilian society.

Public policies are programs, actions and activities promoted by the State, with the participation of public or private entities, ensuring a certain right of citizenship. According to Batista, Muniz and Lucena (2015), public policies correspond to rights guaranteed in the Constitution, such as the right to education. For the authors, public policies are a set of actions and activities the State organizes to promote certain rights, aiming to combat social problems. “It is a way of enforcing rights, intervening in social reality.” (Batista, Muniz and Lucena, 2015, p. 15, our translation). In relation to the public policies for HRE, they play a fundamental role in reducing social inequalities, as they promote HR aiming at the construction of a just society.

According to Rêses and Costa (2015), public policy in HRE is situated in the context of a capitalist state influenced by the degree of popular participation, related to a broader policy: educational policy. Both are considered social policies that gained greater visibility in developing countries in the last decades of the 20th century as well as belonging to the multidisciplinary field (sociology, political science and economics) and directed to the nature and process of public policies.

HRE, for Zluhan and Raitz (2014), was configured in a more structured way in Brazil from the second half of the 1980s, together with the process of redemocratization of the country. In this context, the recognition and affirmation of human rights have emerged as important instruments for the construction of an active citizenship and issues related to social, economic, and cultural rights, in the personal and collective spheres, began to be emphasized. And, at this moment, the activities of HRE bear considerable relevance.

In this perspective, Freitas (2005) states that HRE aims to promote participatory and active teaching and learning processes, which are based on this education, to raise consciousness that allows social actors to assume attitudes of struggle and transformation, reducing the distance between the discourse and the practice of HR in daily life.

According to Pereira (2017), in Brazil, it is from the 1990s, when the State assumes a role of interlocutor before social movements, that HR become part of the agenda of educational policies. In this sense, Zenaide (2005) assures that it was at this moment that, in Brazil, HRE becomes part of the curricula of educational institutions. In accordance with Zenaide (2005, p. 361, our translation),

Education in Human Rights begins in a non-formal way in social movements and civil society organizations, in public universities through extension actions, not only with schools but also with popular neighbourhoods, later reaching formal education with educational institutions and the security and justice system.

The World Conference on Human Rights in 1993, known as the Vienna Conference, defined, internationally, the objective of world peace through education, as well as emphasizing the importance of training and education to work in this area. The conference recommended all states and institutions to include HR, humanitarian law, democracy, and the rule of law as school subjects in the curricula of all educational institutions in the formal and informal sectors. Rêses and Costa (2015) state that the conference ensured the indivisibility and integration of HR, recommending that countries adopt HRE, with a view to producing cultural changes.

In Brazil, the practical effect of the measure was the launch, in 1996, of the first National Human Rights Program (NHRP), on the initiative of the Federal Government, together with the creation, in 1997, of the Secretariat of Human Rights, replacing the former Secretariat of Citizenship Rights, linked to the Ministry of Justice. Tosi (2006) points out that the national program inspired state and municipal programs, as well as a new language and culture in HR. For Pereira (2017), the Secretariat’s objective was, in articulation with civil society and federal entities, to coordinate, manage and monitor the National Human Rights Plan and its implementation.

Also in 1996, the Law of Guidelines and Bases of National Education (LGBNE) (Law No. 9.394/1996 - Brasil, 1996) was enacted , having as perspective the relationship between education and citizenship in the learning process. In this context, Zluhan and Raitz (2014) add that LGBNE brought some references that relate to HRE in its Art. 1: “Education encompasses the formative processes that take place in family life, in human coexistence, at work, in educational and research institutions, in social movements and civil society organizations and in cultural manifestations.” (Brasil, 1996, s. p., our translation).

In 2003, the Federal Government created the National Human Rights Education Committee (NHREC), aiming to prepare and monitor the National Human Rights Education Plan (NHREP), take a stand, and present proposals for public policies, suggest training, capacity building, information, communication and research in HR and policies that promote equal opportunities. In the same year, the first version of the NHREP was launched, being improved, and updated in 2006.

The National Human Rights Education Plan (NHREP) is the result of the State’s commitment to the realization of human rights and a historical construction of organized civil society. While deepening issues of the National Human Rights Program, the NHREP incorporates aspects of the main international human rights documents to which Brazil is a signatory, adding old and contemporary demands of our society for the realization of democracy, development, social justice, and the construction of a culture of peace. (Brasil, 2006, p. 11, our translation)

The NHREP considers that education is understood as a right and a way to access other rights. Thus, Pereira (2017) emphasizes that thinking about the development of human beings and their potentialities involves a significant effort to perceive education as one of the viable alternatives for human dignity to be guaranteed in all contexts of society.

The NHREP is the result, at the national level, of the World Human Rights Education Program (WHREP) promoted by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, whose objective is to provide public managers and HR activists with subsidies and guidelines for the elaboration of educational programs based on respect for HR.

Building on the foundations established during the UN Decade for Human Rights (1995-2004), this new initiative reflects the growing awareness international community’s growing awareness that human rights education produces far-reaching results. By promoting respect for human dignity and equality and participation in the democratic decisions-making, human rights education contributes to the long-term prevention of abuses and violent conflicts. (UNESCO, 2006, p. 2, our translation)

Tosi and Ferreira (2014) point out that WHREP consists of an Action Plan divided into two phases - to better link and articulate governmental and non-governmental efforts around a culture of promotion and defence of HR. The so-called First Phase of the World Programme (2005-2009) brings together recommendations, references, and concrete targets for basic education. The Second Phase (2010-2014), in turn, gives priority to higher education and training in HR for teachers, civil servants, security forces, police and military agents. UNESCO (2006) points out the need for HRE to be present in the development of education programs in all UN member countries.

The situation of Human Rights education in school systems differs widely from country to country, from well-developed policies and actions to little or none. Whatever the status of Human Rights education or the situation or type of education system, the development of Human Rights education should be on each country’s education agenda. Each country should establish realistic goals and means of action for action in accordance with its national context, priorities, and capacity. (UNESCO, 2006, p. 5, our translation)

The NHREP (Brasil, 2007) brings, in its structure, guidelines, objectives, principles and plans of action which address five key components: basic education; higher education; non-formal education; education of professionals of the justice and public security systems; and education and media. It also seeks to encourage the production of research on HRE, making new information available and broadening knowledge.

As one of the guiding principles regarding education, Batista, Muniz and Lucena (2015) emphasize the importance that the plan gives to HRE as one of the solid foundations, and should be present in the curriculum, in the training of school personnel, in the Political Pedagogical Project (PPP), in the teaching materials, in the management model and in the evaluation, hence all school practice should be oriented towards HRE.

In this context, Gorczevski (2013) state that NHREP represents a continuous commitment to the implementation of public policy to consolidate HR awareness in the search for the improvement of the Democratic Rule of Law. It emerges as a governmental attempt to establish a universal plan for HRE based on the principles of democracy and social participation.

However, as the NHREP is a plan based on government public policies, although it should be a state policy, unfortunately most planned actions, due to a number of factors, have been discontinued and/or disjointed in recent years. For Pereira (2017), most factors are due to the failure to strengthen actions and programs at the level of public education policy and other actions were extinguished due to paradigm changes.

It is necessary to advance in the actions of HRE, with a view to the protection of HR, with concrete measures in formal and informal education that value tolerance, dialogue, and peace in relations, valuing respect for diversity in the family environment and at school.

METHODOLOGICAL RESEARCH PATH

This research has as its starting point the UDHR and the UN 2030 Agenda, which established in its SDG-4 to ensure inclusive, equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. Within this context, HRE gains fundamental importance because it stimulates reading, discussion, reflection and change of habits within and outside the school environment, contributing to the intellectual and character formation of the student in a democratic society.

Based on this premise, that is, that HR should be part of the student training process still in primary education, we sought to ascertain how teachers and the school institution approach HRE, since HR issue translates a value of considerable importance for life, as well as its positive effects in a society, in which great violence and disrespect to human beings, their rights and their peculiarities are spread.

In this sense, Andrade (2015) states that the school, as an environment of social coexistence, has the duty to propagate conceptions that revolve around ethics, dignity, and citizenship. This is because the school is not only a space for cognitive knowledge training, but a place for the formation of civic attitudes, a space for individuals to improve citizen, moral, civic, and professional postures.

The research universe was delimited, initially restricting its scope to teachers from public schools in the city of Rio de Janeiro, who teach middle school (6th to 9th year), YAE and high school. Subsequently, it was also extended to public school teachers in nearby cities to Rio de Janeiro municipality (Metropolitan Area), in view of the initial difficulty in obtaining answers to the survey questionnaire. It is noteworthy that the expansion of the research to neighbouring municipalities did not affect its results, considering that teacher training does not differ, and the school curriculum has pedagogical similarity. The specific choice for the middle school, YAE and high school is justified considering that HRE fosters discussions, reflections, behaviours, and pedagogical practices that would be better assimilated by students within an age group corresponding to the segments limited by the research. Nevertheless, it should be noted that HRE must be part of school context at all levels of education. The choice for the public school system is because they receive students from lower class households - those who are directly affected by social inequalities and need the protection of the State regarding the violation of HR.

In the research, a questionnaire containing ten objective questions were used as an approach procedure - the last question with the possibility of the teacher describe a case regarding HR matter they have experienced. The objective of the questionnaire was to verify whether teachers, regardless of what they taught, worked transversally themes related to the content of human rights, considering that there is no specific school subject for this.

In this investigation, qualitative and quantitative research (quali-quantitative) was used. The exploratory method was chosen to gather information on the training of teachers, their age group, and the area where the school is located in. It was also analysed the themes in HR that are addressed in the classroom and at school and which of these themes have greater receptivity among students. It was also verified how these educators are approaching HR within the school context, more specifically, in the classroom. The study also focused on whether the violence experienced by students in their daily lives creates an obstacle in the teaching activity to develop values, reinforce attitudes, and practices which uphold HR, as well as whether violence, aggressiveness and indiscipline behaviours of students constitute an impediment in the teaching practice regarding these themes.

As Gil (2002) explains, exploratory research, along with descriptive research, are usually conducted by social researchers concerned with practical performance. In this case, the concern was towards the implementation of a culture focused on HRE in public schools within the field delimited by the research.

According to Medeiros (2004), exploratory research aims to provide information regarding the object of the research and guide the formulation of hypotheses. For Gil (2002), it can be said that these studies have as their main objective the refinement of ideas or insights generation. In most cases, these investigations involve interviews with people who have had practical experiences with the problem researched or the analysis of examples that promotes understanding.

Researchers collect data about an instrument or test or gather information about a behavioural control list. In this context, Creswell (2010) explains that data collection may involve visiting a research site, observing the behaviour of individuals without predetermined questions, or conducting an interview or a survey by a questionnaire in which the individual is allowed to speak openly about a topic with or without specific questions. The type of data analysed can be numerical information gathered on instrument scales (quantitative research) or text information recording and reporting what the participants said (qualitative research). In some forms of research, as in the present study, both quantitative and qualitative data are collected, analysed, and interpreted. The data collected by instruments can be expanded with open observations. In this case of mixed approaches, the researcher makes inferences about both quantitative and qualitative databases.

The questionnaire was created and shared with the teachers through Google Forms, a free and user-friendly online form creation tool. The teachers received the link to the form via WhatsApp on their mobile phone. Once answered, the responses were automatically sent to the researchers’ database. The survey was sent to teachers and school principals within the researchers’ contact network.

During the period from December 20th, 2019 to January 13th, 2020, a pre-test of the research instrument was conducted to remedy any impropriety that may exist or resolve any dubious issue, which could harm or influence the result of the survey research.

In this sense, Gil (2002) clarifies that it is necessary to pre-test each research instrument before its use to develop the application procedures, assess the vocabulary used and ensure that the questions or observations make it possible to measure the intended variables.

It is worth noting that, during this pre-test phase, an education specialist, who tested the questionnaire, drew attention to the fact that it would not be properly, technically speaking, to call inclusive education a modality of education (Question No. 6), a term initially used by the researcher, clarifying that special education would be a modality of education, based on Art. 58, of LGBNE:

Art. 58. Special education, for the purposes of this Law, means the type of school education offered preferably in the regular school system, for students with disabilities, global developmental disorders and high abilities or giftedness. (Wording given by Law No. 12.796, of 2013) (Brasil, 1996, s. p., our translation)

Therefore, given the observation, it was preferable to reformulate the question to clarify that inclusive education is an education process encompassing students with any type of disability or disorder.

Relevant to mention here that the form was shared randomly, without any worrying about prioritizing teachers from a single school or of a specific school subject. The intention was to share the survey among municipal, state, and federal schools, regardless of the teacher’s area of activity or gender.

Professor Gil (2002) draws attention to the fact that, in a survey, the preservation of the identity of respondents is a high ethical relevance issue. A major dilemma of the researcher is the decision about whether to reveal the identity of the respondent. In fact, remaining incognito can be advantageous for obtaining certain data. However, invading the privacy of others without consent is undoubtedly an unethical procedure. Therefore, considering the identification of the school and even the teacher-respondent as irrelevant, it was decided not to require identification, either from the school or from the teacher.

The questionnaire was answered by 120 teachers from the public school system, in the Metropolitan Area of the city of Rio de Janeiro, who teach middle school, high school and YAE at the municipal, state, and federal levels, from January 14th, 2020 to March 13th, 2020, obtaining the percentage shown in Graph 1.

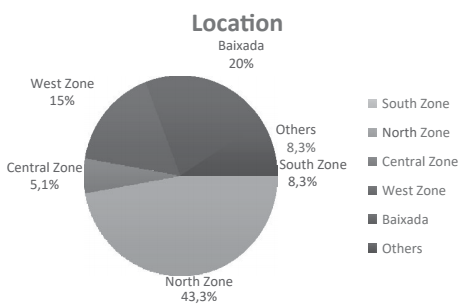

Regarding the level of education, by sphere of activity, we have the data of Chart 1. As for the location of the school, where the teachers work (Graph 2), 43.3% are from the North Zone, 20% from the Baixada Fluminense, 8.3% from the South Zone, 8.3% from other locations (Niterói and São Gonçalo) and 5.1% from the Central Zone.

Chart 1 - Level of education by sphere of activity.

| Federal | State | Municipal | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High school | 13 (10.8%) | 59 (49.2%) | 0.0% | 60.0% |

| Middle school | 1 (0.8%) | 5 (4.2%) | 30 (25.0%) | 30.0% |

| YAE | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (4.2%) | 7 (5.8%) | 10.0% |

YAE: youth and adult education.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

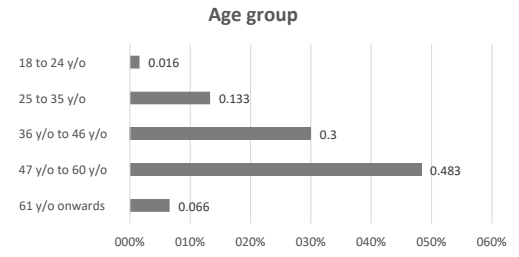

As for the age group, we have the distribution presented in Graph 3, which shows that about 85% of teachers were born before the 1988 Citizen Constitution was enacted, thus receiving educational and social training during the military regime.

Graph 4 shows the teachers divided into exact and non-exact sciences: the exact sciences - mathematics, chemistry, biology, and sciences - encompass 25% of the teachers; while the non-exact sciences - writing, geography, Portuguese, Brazilian literature, sociology, history, English, Spanish, philosophy, religious education, visual arts, plastic arts, and physical education - concentrate 75%.

It was expected that in non-exact sciences there would be the largest number of teachers providing HRE. However, the proportion of 25% of teachers in the exact sciences who are concerned with providing HR content in parallel with the syllabus of their school subject represents an advance in HRE - as it demonstrates that the teacher from this group is fully aware of HRE in the full training of the student as a citizen.

A PERCEPTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION: RESEARCH WITH MIDDLE SCHOOL, YOUTH AND ADULT EDUCATION AND HIGH SCHOOL TEACHERS OF THE PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM IN RIO DE JANEIRO AND NEARBY AREAS

This section examines and discusses the collected data obtained from a questionnaire answered by 120 teachers. They are middle school, YAE and high school teachers in the Metropolitan Area of the city of Rio de Janeiro. The focus was on these teachers’ concern in addressing HR, verifying whether they promote practices of citizenship, environment and sustainability in the classroom and their own involvement in the culture of HRE. It also sought to assess whether the teacher believes that it is possible to approach a culture of HR with students, believing that these attitudes will contribute to the general training of these students.

It was intended to demonstrate, through the research instrument, that HRE comes from a State public policy that presupposes the realization of a collective involvement, with the participation of the student and the school community: teacher, technical staff, and other members of the school board to recognize HR as a curricular activity of reflection that should be present in the teaching-learning processes.

According to Bourdieu (1989), research should be understood as a rational activity and not as a mystical search. The attitude of the researcher must be like that of one who humbly dedicates themselves to a craft, opposing to a show, an exhibition in which they only seek to be seen - science must refuse the certainties of definitive knowledge, as it can only progress if it perpetually questions the principles of its own constructions. Thus, to do science, it would be necessary to “[...] avoid the appearances of scientificity, even contradict the norms in currency to challenge ordinary criteria of scientific rigour.” (Bourdieu, 1989, p. 42, our translation).

In this sense, it is also worth highlighting the foundations of Bourdieu’s (1989) reflexive sociology, in which he teaches us that research must adopt and pursue a flexible character, keeping the researcher open to criticism and deducing, therefore, useful arguments. And he adds that we must still be receptive to innovation and the chance of enriching ourselves with mistakes, since by avoiding them, systematically, the opportunity for new contributions is missed.

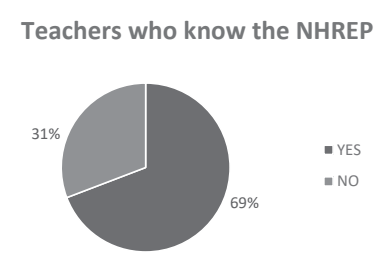

Regarding the first question of the form, we seek to verify whether the respondent is aware of the NHREP, a program instituted in 2007 by the Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC) together with the Special Secretariat of Human Rights, both Federal Government, in partnership with UNESCO. It was created to guide educational policies aimed at the constitution of a culture of HR to be implemented by the government, with society, to contribute to the improvement of a democratic State, addressing five key components: basic education; higher education; non-formal education; education of professionals of the justice and public security systems; and education and media.

Of the data collected (Graph 5), 83 (69%) respondents reported knowing the NHREP and only 37 (31%) teachers do not know it. Considering the federal, state, and municipal spheres of activity, as shown in Chart 2, 57.1% of federal teachers, 78.3% of state teachers and 56.8% of municipal teachers know the NHREP, concluding, therefore, that there is a greater role for the dissemination of the program at the state level than in the other spheres of education.

NHREP: National Human Rights Educational Plan. Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 5 - Teacher who knows the National Human Rights Educational Plan.

Chart 2 - Percentages of teachers who know the National Human Rights Educational Plan by sphere of activity.

| Sphere | Total | Yes | % | No | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal | 14 | 8 | 57.1 | 6 | 42.9 |

| State | 69 | 54 | 78.3 | 15 | 21.7 |

| Municipal | 37 | 21 | 56.8 | 16 | 43.2 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

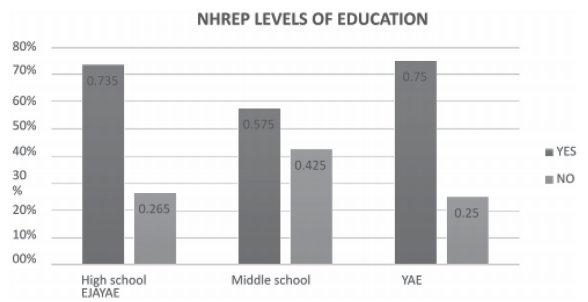

Observing Graph 6, it is concluded that NHREP is known by three quarters of the respondents who work in YAE and high school, representing positive information, since they teach both young people about to complete basic education (high school) and adults (YAE) capable of influencing others with their attitudes. The knowledge of the NHREP presupposes that teachers can improve HR attitudes, since they understand that it is a state policy to be implemented in the teaching-learning process.

NHREP: National Human Rights Educational Plan; YAE: youth and adult education. Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 6 - Teacher who knows the National Human Rights Educational Plan by levels of education.

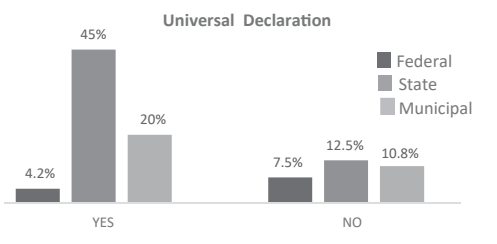

The number of teachers who have already mentioned the UDHR in the classroom was also significant (Graph 7). Among the 69.2% respondents who said they mentioned UDHR in class, it can be observed, in Graph 8, that the highest percentage are at the state level, with 45%, in relation to the federal (4.2%) and municipal (20%) levels.

UDHR: Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 7 - Teacher who has already mentioned the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the classroom.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 8 - Teacher who mentioned the Universal Declaration of Human Rights distributed by sphere of activity.

Analysing at what level of education the teacher has already mentioned the UDHR in class, it can be seen within this context, according to Chart 3, that 49 out of 83 respondents who teach at high school responded yes to the question. Among these, those who teach non-exact sciences prevail with 91.8%.

Chart 3 - Teacher who mentioned the Universal Declaration of Human Rights distributed by levels of education.

| Level | Number of teachers | Exact sciences (%) | Non-Exact sciences (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High school | 49 | 8.2 | 91.8 |

| Middle school | 24 | 16.7 | 83.3 |

| YAE | 10 | 40.0 | 60.0 |

| Total | 83 | 14.5 | 85.5 |

YAE: youth and adult education.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Also, in Chart 3, it is observed that there are 24 middle school teachers who have already mentioned UDHR in class against 10 teachers from YAE. However, it is evident that teachers working in non-exact area are the ones who have had the opportunity to address the issue.

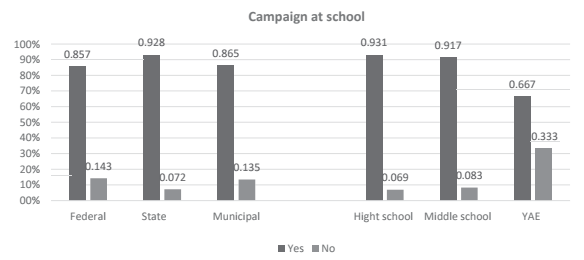

Another question focuses on whether the schools where the teachers work have already promoted any HR campaign, addressing themes such as tolerance, discrimination, racism, equality, or solidarity. As shown in Graph 9, 90% of respondents said that there has already been a school campaign where they work. However, when analysing in which sphere of activity and at what level they teach, it can be seen through Graph 10 that the most expressive results are concentrated in state schools (92.8%), high school (93.1%) and middle school (91.7%). YAE responds for 66.7% - one of the reasons for this lower performance may be the working conditions regarding this group, who study at night, when the school practically has its extracurricular activities closed.

YAE: youth and adult education. Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 10 - Human rights campaign at schools distributed by sphere of activity and level of education.

As for the location of schools that have already promoted HRE campaigns, as it is possible to observe in Graph 11, the Central and West Zones in the city of Rio de Janeiro together with Baixada Fluminense and other locations in the Metropolitan Area stand out.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 11 - Human rights campaign at school distributed by school location.

This represents a positive fact, considering that the locations mentioned are those that present a higher rate of violence and vulnerability.

Respondents were also asked about the campaigns promoted by the school. They were informed about the most varied ways of promoting HR:

Black Consciousness cultural gathering;

Day of inclusion of the person with disabilities;

Campaign on autismo;

Culture rescue;

Fight against racismo;

Campaign to combat religious intolerance;

Black Consciousness Week;

A week dedicated to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights;

Week against violence in schools;

Campaign to prevent suicide, femicide and racial intolerance;

Empowerment of minorities.

They were also asked about the development of the following projects:

Brazilianity X Afrikanity Project;

Annual Project on Cultural Heritage Values;

Racial Ethnic Project;

Human Rights Project;

Invisible Populations Project;

Black November Project;

It is worth mentioning that two respondents informed that the school promote activities to address topics on HR, since this theme is part of the school’s PPP. This shows that promoting activities related to HRE integrates teaching-learning policies.

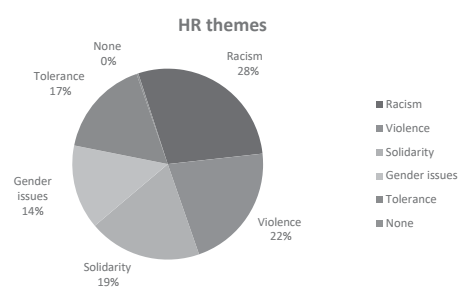

Analysing the HR themes that are addressed, racism and diversity were the most highlighted by the respondents, according to Graph 12.

Regarding the HR themes in which teachers perceive greater receptivity, racism is what stands out from the others with 72.5%, as shown in Graph 13.

HR: human rights. Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 13 - Themes with receptivity to be addressed with students.

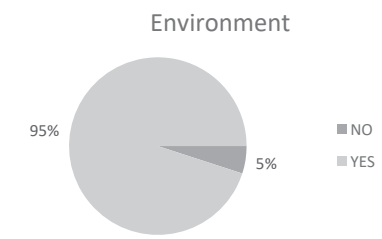

According to Graph 14, environmental themes are discussed in the classroom by 95% of teachers.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 14 - Environmental and sustainability themes discussed by the teacher.

The profiles of the 5% of respondents who did not discuss sustainability or the environment in the classroom are shown in Chart 4.In analysing this chart, it is not possible to draw a specific profile of the teacher who does not promote environment and sustainability in the classroom, except for the prevalence in the non-exact sciences. This teacher can be found in the various teaching segments since there was no greater concentration on a particular characteristic. However, in view of what has been seen, trying to outline the profile of this teacher, we would say that they work at high school level of the state school system, teach non-exact sciences at a school in Baixada Fluminense or in the North Zone and are between 25 and 35 years old.

Chart 4 - Continuation.

| Did not discuss environment or sustainability | ||

|---|---|---|

| Teacher | 6 | 5.0% |

| Exact sciences | 1 | 0.8% |

| Non-Exact sciences | 5 | 4.2% |

| High school | 4 | 3.3% |

| Middle school | 2 | 1.7% |

| YAE | 0 | 0.0% |

| Federal | 2 | 1.7% |

| State | 4 | 3.3% |

| Municipal | 2 | 1.7% |

| 18 to 24 y/o | 0 | 0.0% |

| 25 to 35 y/o | 3 | 2.5% |

| 36 to 46 y/o | 1 | 0.8% |

| 47 to 60 y/o | 2 | 1.7% |

| 61y/o onwards | 0 | 0.0% |

| Baixada | 2 | 1.7% |

| North zone | 2 | 1.7% |

| West zone | 1 | 0.8% |

| South zone | 1 | 0.8% |

| Others | 0 | 0.0% |

YAE: youth and adult education; y/o: years old.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The survey also posed a question regarding the inclusion of students with disabilities or disorders in the classroom. The question sought to know whether there was any form of exclusion, as shown in Graph 15. Analysing this graph by levels of education, we can see that the problem of excluding students with disabilities or disorders is more evident in middle school (25%) and in high school (23.6%), as shown in Chart 5.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 15 - Whether the inclusion of students with disabilities or disorders in the class was problematic.

Chart 5 - Inclusion and exclusion distributed by levels of education.

| Total respondents | There was no problem (%) | There was a problem (%) | Never worked with students with disabilities or disorders (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High school | 72 | 62.5 | 23.6 | 13.9 |

| Middle school | 36 | 69.4 | 25 | 5.6 |

| YAE | 12 | 58.3 | 16.7 | 25.0 |

YAE: youth and adult education.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

One question (Graph 16) addressed whether it made sense for the teacher to promote a rights-based approach to HRE in schools located in the outskirts where violence, neglect of the Public Power, inequality, and tragedies are faced daily.

HRE: human rights education. Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 16 - Teachers’ perception whether it makes sense to provide human rights education.

Only three teachers, which is equivalent to 2.5% of respondents, reported that approaching HR in schools in the outskirts does not make sense. As for the level of education, there was a representative at each one. The schools are in Baixada Fluminense and in South Zone of Rio de Janeiro. As for age, they are teachers aged 47 and over (Graph 17).

HRE: human rights education. Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 17 - Profile of the teachers who believe there is no sense in providing human rights education.

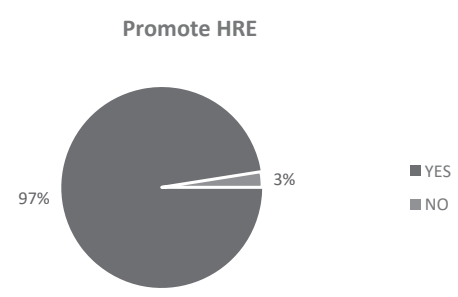

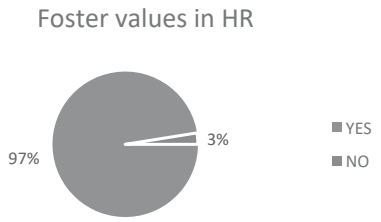

The school is the main place where the social awareness of students in training is built (Question 8). Teachers were asked whether it was possible to foster values, attitudes, and practices which uphold HR in students who face violence within and outside the school, experience social inequality, and live in poorly structured homes.

According to Graph 18, 117 out of the 120 respondents answered affirmatively to the question that it is possible to provide HRE, which represents a percentage of 97.5% of the teachers. Among these, 18% emphasized that they do not lose hope, indicating that the educator is aware that the practice of respect for HR at school contributes to the formation of citizens who are capable of positively transforming the society in which they live.

HR: human rights. Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 18 - Possibility of fostering values, attitudes, and practices which uphold human rights.

Among the three respondents (2.5%) who consider that the school is not capable of developing values, attitudes, and practices of HR, in view of the violence and inequalities that students experience, the only teacher who informed that it is no use providing HRE teaches Portuguese at the middle school in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro and is between 47 and 60 years old.

Another question (Graph 19) addressed indiscipline behaviour and attitudes in the classroom. For 99.2% of respondents, there are conditions to discuss aggressive behaviour and violence with students. Only one respondent (0.8%) considers that the school is not prepared to discuss aggression or violence with students in class. Looking into the profile of this teacher, it appears to be a teacher aged between 36 and 46 years who teaches chemistry in the West Zone, in a state high school. This teacher does not know about NHREP or mentioned the UDHR in the classroom but has already discussed environment and sustainability with students in class. Due to the characteristics presented, this is a teacher restricted exclusively to teaching chemistry to students, not considering that there is a curricular content that must be transmitted transversally - there are values that permeate the disciplines that are stratified by content. For this reason, it appears that the teacher does not work on behaviour and attitudes of indiscipline because “this is not in his/her area of expertise”. This explains why this same teacher only wants to teach the subject content, chemistry, not approaching HR through education. For this professional, HR should be a school subject taught by a specific teacher. Only in this way would it make sense to provide and promote HRE to students in public schools in the outskirts (Question 7) and foster values, attitudes and practices which uphold human rights (Question 8).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 19 - Possibility for the teachers to discuss violence/aggression in the classroom.

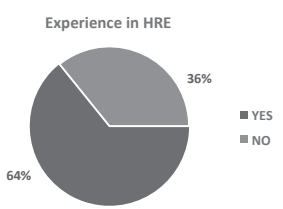

The last question sought to know whether the teachers had the opportunity to put into practice some experience in HRE with students. Once again, the result was positive for 64.2% of respondents (Graph 20).

HRE: human rights education. Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Graph 20 - Teachers who had human rights experience in classroom.

Outlining the profile of the teachers who have had HRE practices in the classroom, teachers (Chart 6) who teach non-exact sciences are the majority, 72.2% of the total. As for the sphere of activity, state (71%) and municipal (62.2%) schools are the ones that stand out the most. Regarding the level of education, there is not so much difference between high school, middle School and YAE, with a tie in the latter two (66.7%).

Chart 6 - Distribution of the teachers with experience in human rights by sphere of activity and level of education.

| Subject | Sphere of activity | Level of education | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exact sciences | Non-exact sciences | Federal | State | Municipal | High school | Middle school | YAE | |

| Total | 30 | 90 | 14 | 69 | 37 | 75 | 33 | 12 |

| Yes (%) | 40.0 | 72.2 | 35.7 | 71.0 | 62.2 | 62.7 | 66.7 | 66.7 |

| No (%) | 60.0 | 27.8 | 64.3 | 29.0 | 37.8 | 37.3 | 33.3 | 33.3 |

YAE: youth and adult education.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

A sizeable number of teachers shared their experiences in HRE with their classes. In the testimonies, teachers valued the importance of mutual respect. According to them, students have interests, are concerned, feel immensely the lack of their rights, and seek discussion, want to expose, and want to have the awareness and practice of their duties and HR. For teachers who discussed HR themes in class, they revealed that the debate has promoted changes based on the exposed demands, with positive results, good interaction, participation, and class achievement.

The most debated HR themes in class, according to the respondents, addressed bullying resulting from racism, violence generated by intolerance, homophobia, gender issues and inclusion. It is worth mentioning, in view of the testimonies, that these are experiences lived by students outside the school, but that they are brought to conviviality inside the school.

Based on the answers to the questionnaire and illustrated with the testimonies of several teachers, it appears that, despite all the difficulties that the public school in Brazil goes through, and in the specific case, the public school in the city of Rio de Janeiro and the Metropolitan Area, the teacher seeks to convey values and attitudes which uphold HR to students.

The vast majority of positive responses to the questionnaire indicate that teachers are not only concerned with intellectual training, but also with citizenship practices. Schools promote HR-themed activities addressing racism, tolerance, homophobia, and solidarity, values which are more sensitive to their students.

It was noticed that the theme of HR is part of the school curriculum, including in the PPP, as reported by some teachers in their testimonies. On the other hand, it was found that there is no uniform line of approaching HRE at schools, whether federal, state, or municipal. Schools and especially the teachers address HR theme according to their own conception and concepts - considering that the merit in preparing students and fostering a culture of HR comes exclusively from the teacher. From what was verified, there is not an agenda in HR to be followed, but the teacher’s own effort, built through their experiences, since teacher training courses do not prepare future teachers pedagogically as multipliers of values and attitudes regarding HR.

Thus, if the school has in its faculty engaged teachers and a participatory board involved in training citizens, going beyond the concern of only transmitting acquired knowledge, we will have students prepared to live in society, in which values such as solidarity, tolerance, and respect for others will contribute to build citizens who will respect freedom. Thus, cooperating with a more just and democratic society. In this sense, Moran, Masetto and Behrens (2006, p. 32, our translation) state that the “[…] teacher has a wide range of methodological options, possibilities to organize communication with students, to introduce a theme, to work with students in person and remotely, to evaluate them.”.

Although the number of teachers from non-exact sciences who explore HR themes was higher, there was also a considerable number of teachers from the exact sciences who are concerned with the formation of the student as a citizen. A chemistry teacher, for example, address the topic of aids and its implications for society when teaching the components of a formula that is used in pharmaceutical industry to combat this disease. The active principle of the formula became a hook to talk about this disease and all the prejudices involved.

It was also verified, through the research, that the age of the teacher and the location of the school were not significant factors to determine a behaviour that would differentiate it from other areas of the city. Providing and promoting HRE is not associated with the teacher’s age group or where the school is located. As already mentioned, it depends more on the teacher’s commitment. If there is no such involvement, including attitudes and habits that uphold HR, there is a risk of building an empty, rhetorical knowledge that needs to be avoided.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The pedagogical conception of HR themes does not require the constitution of new teaching areas but presupposes an integrated and comprehensive treatment in different areas, through the transversality of HR teaching, requiring the need for the school community to reflect and consciously act in the education of values and attitudes regarding all school subjects.

HRE needs to be understood as a pedagogical instrument, capable of creating effective and efficient learning in students. Their skills and competencies will be developed from the act of questioning everything that happens around them, and not settling in the acceptance of pre-established situations.

It is necessary to rethink ways to encourage the promotion and offer of HRE at schools, either through specific or occasional school subjects, as well as to intensify its transmission in an interdisciplinary and transversal way - through compulsory and optional school subjects, syllabus, seminars, research, conferences, field classes, films, and dramatizations among other creative methods. In this sense, the curricular plans and guidelines of the government secretariats play a role of paramount importance.

However, one of the biggest challenges for HRE is undoubtedly the teacher, who must remain consistent, since they will be responsible for the articulation of theory/practice, discourse/attitude. HRE strives towards an environment where HR are practised and lived. Therefore, the teacher’s attitude is crucial, and it is essential that their gestures reflect what they propose so that there is no gap between their experience and practice, at the risk of discrediting the entire process of training students based on the ethics and values of HR.

In this sense, the teacher needs to constantly exercise self-criticism, to confront postures, discourses, convictions, biases, prejudices, and ways of seeing the world. It presupposes a permanent reflection to always be attentive to one’s own attitudes and, often, to one’s own thoughts, in a process of self-analysis under construction. Introducing or improving HRE starts, in large part, from the political decision of the teacher willing to assume the HR as commitment and determination, forming citizens not only from their action as a teacher, but also as a professional and human being.

Based on the information brought by the teachers who participated in the study, it appears that the actions aimed at the dissemination of HR at schools start from day-to-day practices or based on knowledge obtained by the teacher through common sense, from cultural baggage seized, journalistic news, independent readings, courses, participation in events, Christian training, among others, not constituting methodological formative actions arising from the public power, as in the case of the teacher who developed a project with the students based on a book that addressed prejudice to immigrants (Strangers at our door), expanding the discussion to other topics such as religious persecution and racism.

Despite this institutional absence, there was no discourse in the testimonies of this inexistence to justify the lack of professional preparation to safely address the aspects of HRE in their area of activity, as verified in the testimony of the teacher who approached the issue of inclusion of students with deafness, saying that, “even as a teacher not qualified to meet this demand for inclusion”, he sought to facilitate the students’ learning “in addition to showing the importance of inclusion in the class”.

Thus, despite the limited universe of the research sample among a wide universe that represents teachers at high school, middle school and YAE in the city of Rio de Janeiro, the present study aims to collaborate with and to reflect on the implementation of pedagogical practices and public policies focusing on the training of individuals in HR.

It is concluded that it is the teacher’s efforts, within the limits imposed by the financial and pedagogical difficulties (representing the reality that public schools in the state and in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro go through) that drive HR practices, so necessary to the full formation of the student. It is true that the concern to teach HR does not represent the totality of teachers and public schools, but by far represents the minority, as verified in this study. However, if the school has not yet reached a satisfactory stage of development in the formation of students as citizens aware of their rights and duties, it is because there is still a lot to be done. It is necessary to work together with other public policies aimed at the development of the human person. This means having decent schools, with no shortage of teachers, a health system capable of serving the vulnerable population, police that do not enter the favela just to kill, quality public transport, etc. It is worthy showing the students that what they learn at school has a visible result when they return home, that their learning is consistent and coherent with their experience, not meaning actions and attitudes that make no sense, pure rhetoric that is learned in the classroom.

Hence, we have not yet verified in the student in training attitudes and practices which uphold HR, a great deal can be explained by the lack of other practices absent in society that are at odds with what the student is led to learn in the classroom.

REFERENCES

ANDRADE, E. A. Análise da violação dos Direitos Humanos na escola pública. 2015. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Especialização Educação em Direitos Humanos) - Universidade Federal do Paraná, Irati, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://acervodigital.ufpr.br/bitstream/handle/1884/42299/R%20-%20E%20-%20ELIANE%20APARECIDA%20DE%20ANDRADE.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y . Acesso em: 25 jan. 2023. [ Links ]

BATISTA, J. H. M.; MUNIZ, I. G.; LUCENA, M. I. H. M. Políticas públicas e educação em direitos humanos: o PNEDH e o caso brasileiro. Direcho y Cambio Social, n. 40, abr. 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.derechoycambiosocial.com/revista040/POLITICAS_PUBLICAS_E_EDUCACAO_EM_DIREITOS_HUMANOS.pdf . Acesso em: 4 abr. 2020. [ Links ]

BOURDIEU, P. O poder simbólico. Tradução: Fernando Tomaz. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Bertrand Brasil, 1989. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Lei nº 9394/96, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília, DF: Presidência da República, 1996. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9394.htm . Acesso em: 4 abr. 2020. [ Links ]

BRASIL. Comitê Nacional de Educação em Direitos Humanos. Plano Nacional de Educação em Direitos Humanos. 2. tiragem, atualizada. Brasília: Secretaria Especial dos Direitos Humanos, Ministério da Educação, Ministério da Justiça, UNESCO, 2007. [ Links ]

CANDAU, V. M. F. Direito à educação, diversidade e educação em direitos humanos. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 33, n. 120, p. 715-726, jul.-set. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-73302012000300004 [ Links ]

CRESWELL, J. W. Projeto de pesquisa: métodos qualitativos, quantitativos e misto. 3. ed. Tradução: Magda Lopes. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2010. [ Links ]

FREITAS, F. F. B. O ensino de direitos humanos no centro de humanidades da UFPB. In: ZENAIDE, M. N. T.; DIAS, L. L.; TOSI, G.; MOURA, P. V. (org.). A formação em direitos humanos na universidade: ensino, pesquisa e extensão. João Pessoa: Editora Universitária/UFPB, 2005. p. 130-153. [ Links ]

GIL, A. C. Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa. 4. ed. São Paulo: Editora Atlas, 2002. [ Links ]

GORCZEVSKI, C. A educação e o plano nacional de educação em Direitos Humanos: efetivando os direitos fundamentais no Brasil. Revista do Direito, Santa Cruz do Sul, n. 39, p. 18-42, jan.-jul. 2013. https://doi.org/10.17058/rdunisc.v0i0.3550 [ Links ]

MEDEIROS, J. B. Redação científica: A prática de fichamentos, resumos, resenhas. 6. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2004. [ Links ]

MORAN, J. M.; MASETTO, M. T.; BEHRENS, M. A. Novas tecnologias e mediação pedagógica. 10. ed. Campinas, SP: Papirus, 2006. [ Links ]

ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS - ONU. Declaração universal dos direitos humanos. [s.l.]: Nações Unidas, 1948. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://brasil.un.org/pt-br/91601-declaracao-universal-dos-direitos-humanos . Acesso em: 21 fev. 2020. [ Links ]

ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS - ONU. Agenda 2030 para o Desenvolvimento Sustentável. [s.l.]: Nações Unidas, 2015. Disponível em: Disponível em: https://brasil.un.org/pt-br/91863-agenda-2030-para-o-desenvolvimento-sustentavel . Acesso em: 28 nov. 2019. [ Links ]

PEREIRA, D. A. A. Formação inicial de professores: um estudo de caso sobre a educação em direitos humanos. 2017. 160 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade Católica de Brasília, Brasília, 2017. [ Links ]

PIOVESAN, F. Educação em direitos humanos no ensino superior. In: ZENAIDE, M. N. T.; DIAS, L. L.; TOSI, G.; MOURA, P. V. (org.). A formação em direitos humanos na universidade: ensino, pesquisa e extensão. João Pessoa: Editora Universitária/UFPB, 2005. p. 71-81. [ Links ]

RÊSES, E. S.; COSTA, D. R. A política pública de Educação em Direitos Humanos e formação de professores. ARACÊ - Direitos Humanos em Revista, ano 2, n. 2, maio, 2015. [ Links ]

SCHÜTZ, J. A.; FUCHS, C. Educação escolar e Direitos Humanos: necessidades de uma aproximação. Perspectiva Sociológica, n. 20, 2. sem. 2017. http://dx.doi.org/10.33025/rps.v0i20.1473 [ Links ]

SILVA, H. P. Educação em direitos humanos: conceitos, valores e hábitos. 1995. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação) - Universidade de São Paulo, 1995. [ Links ]

TOSI, G. Direitos humanos como eixo articulador do ensino, da pesquisa e da extensão universitária. In: ZENAIDE, M. N. T.; DIAS, L. L.; TOSI, G.; MOURA, P. V. (org.). A formação em direitos humanos na universidade: ensino, pesquisa e extensão. João Pessoa: Editora Universitária/UFPB, 2005. p. 22-41. [ Links ]

TOSI, G.; FERREIRA, L. F. G. Educação em direitos humanos nos sistemas internacional e nacional. In: FLORES, E. C.; FERREIRA, L. F. G.; MELO, V. L. B. (org.) Educação em direitos humanos & educação para os direitos humanos. João Pessoa: Editora Universitária da UFPB, 2014. p. 33-60. [ Links ]

UNESCO. Plano de Ação: Programa Mundial para Educação em Direitos Humanos. Primeira Fase. Paris: Unesco, 2006. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.dhnet.org.br/dados/textos/edh/br/plano_acao_programa_mundial_edh_pt.pdf . Acesso em: 2 abr. 2020. [ Links ]

ZENAIDE, M. N. T. A educação em direitos humanos. In: TOSI, G. (org.). Direitos Humanos: história, teoria e prática. João Pessoa: Editora Universitária UFPB, 2005. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.cchla.ufpb.br/ncdh/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/2005.DH_.-historia-teoria-pr%C3%A1tica.pdf . Acesso em: 22 mar. 2020. [ Links ]

ZLUHAN, M. R.; RAITZ, T. R. A educação em direitos humanos para amenizar os conflitos no cotidiano das escolas. Revista Brasileira Estudos Pedagógicos, Brasília, v. 95, n. 239, p. 31-54, jan.-abr. 2014. Disponível em: Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbeped/v95n239/a03v95n239.pdf . Acesso em: 1 abr. 2020. [ Links ]

Received: December 16, 2021; Accepted: May 06, 2022

texto en

texto en